Matot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Matot, Mattot, Mattoth, or Matos ( — Hebrew for "tribes", the fifth word, and the first distinctive word, in the

Matot, Mattot, Mattoth, or Matos ( — Hebrew for "tribes", the fifth word, and the first distinctive word, in the

The commanders of the troops told Moses that they had checked the warriors, and not one was missing, so they brought as an offering to God the gold that they came upon — armlets, bracelets, signet rings, earrings, and pendants — to make expiation for their persons before God. Moses and Eleazar accepted from them 16,750 shekels of gold, but the warriors in the ranks kept their booty for themselves.

The Mishnah taught that saying any substitute for the formulas of a vow has the validity of a vow. If one says to another, "I am barred from you by a vow," or, "I am separated from you," or, "I am removed from you, in respect of anything that I might eat of yours or that I might taste of yours," the one vowing is prohibited. Rabbi Akiva was inclined to give a stringent ruling when a person says, "I am banned to you." The

The Mishnah taught that saying any substitute for the formulas of a vow has the validity of a vow. If one says to another, "I am barred from you by a vow," or, "I am separated from you," or, "I am removed from you, in respect of anything that I might eat of yours or that I might taste of yours," the one vowing is prohibited. Rabbi Akiva was inclined to give a stringent ruling when a person says, "I am banned to you." The

Rabbi Eleazar interpreted to teach that one should not treat lightly, because on account of it were the members of the Great Sanhedrin of Zedekiah slain. When King Jeconiah of Judah was exiled, King

Rabbi Eleazar interpreted to teach that one should not treat lightly, because on account of it were the members of the Great Sanhedrin of Zedekiah slain. When King Jeconiah of Judah was exiled, King

29

stated the same condition in both positive and negative formulations. states the condition in the positive: "And Moses said to them, if the children of Gad and the children of Reuben will pass with you over the Jordan, . . . then you shall give them the land of Gilead for a possession." And states the same condition in the negative: "But if they will not pass over with you armed, then they shall have possessions among you in the land of Canaan." Rabbi Meir deduced that every stipulation must be stated in both the negative and positive formulations, like the condition of the children of Gad and the children of Reuben in an

or it is not a binding stipulation. Rabbi Hanina ben Gamaliel II maintained, however, that Moses stated the matter both ways because he needed to do so to be understood; otherwise one might have concluded that the Gadites and Reubenites would receive no inheritance even in the land of Canaan. The Mishnah taught that those who removed from the Temple coins collected in the shekel tax could not enter the chamber wearing a bordered cloak or shoes or sandals or tefillin or an amulet, lest if they became rich people might say that they became rich from money in the chamber. The Mishnah thus taught that it is one’s duty to appear to be free of blame before others as before God, as says: “And you shall be guiltless before the Lord and before Israel.”

Similarly, the Tosefta cited “You shall be clear before the Lord, and before Israel,” to support the proposition that while out collecting charity, charity collectors were not permitted to separate their own money from that which they collected for charity by placing their own money in a separate purse, lest it appear that they were stealing for themselves some of the money that they gathered for charity. While collecting for charity, a charity collector could not take for personal use money from a friend who owed the charity collector money, and a charity collector could not take for personal use money that the charity collector found on the road.

The Sages taught in a Baraita that they honored the memory of the family that baked the Temple

The Mishnah taught that those who removed from the Temple coins collected in the shekel tax could not enter the chamber wearing a bordered cloak or shoes or sandals or tefillin or an amulet, lest if they became rich people might say that they became rich from money in the chamber. The Mishnah thus taught that it is one’s duty to appear to be free of blame before others as before God, as says: “And you shall be guiltless before the Lord and before Israel.”

Similarly, the Tosefta cited “You shall be clear before the Lord, and before Israel,” to support the proposition that while out collecting charity, charity collectors were not permitted to separate their own money from that which they collected for charity by placing their own money in a separate purse, lest it appear that they were stealing for themselves some of the money that they gathered for charity. While collecting for charity, a charity collector could not take for personal use money from a friend who owed the charity collector money, and a charity collector could not take for personal use money that the charity collector found on the road.

The Sages taught in a Baraita that they honored the memory of the family that baked the Temple

4:7:1, 3.

Circa 93–94. In, e.g., ''The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition''. Translated by William Whiston, pages 113–14. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. . *

Shabbat 24:5Chagigah 1:8

Nedarim 1:1–11:11

Gittin 4:7

Kiddushin 3:4; Shevuot 1:1–8:6

Avot 3:13.

Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. In, e.g., ''The Mishnah: A New Translation''. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 330, 406–30, 492–93, 620–39, 680. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. . * Tosefta: Peah 4:15; Terumot 5:8; Nedarim 1:1–7:8; Sotah 7:17; Shevuot 1:1–6:7; Keritot 4:15. Land of Israel, circa 250 C.E. In, e.g., ''The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction''. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 73, 161, 208, 785–805, 864; volume 2, pages 1219–44, 1571. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. . * Jerusalem Talmud: Terumot 35b; Bikkurim 6a; Shabbat 45a; Pesachim 74b; Chagigah 7a–b; Nedarim 1a–42b; Nazir 1a, 17a; Sotah 9a; Shevuot 1a–49a. Tiberias, Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. In, e.g., ''Talmud Yerushalmi''. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 7, 12, 14, 19, 27, 33–34, 36, 46. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008–2019. And in, e.g., ''The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary''. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009. . * Genesis Rabbahbr>1:1548:1055:3

85:14. Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Genesis''. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 13–14, 411–12, 483–84; volume 2, page 799. London: Soncino Press, 1939. . *Babylonian Talmud

*Babylonian Talmud

Berakhot 8b24a32aEruvin 63aPesachim 13a66bYoma 38a63bMoed Katan 9a16aChagigah 10aNazir 4b12b20b21b23a37b38b61a62bSotah 3a13b43aKiddushin 3b61a78a81bMakkot 11a16aShevuot 2a–49bZevachim 97a113bMenachot 77bChullin 25bArakhin 20bTemurah 6b13aKeritot 6b

Babylonia, 6th Century. In, e.g., ''Talmud Bavli''. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

* Rashi. ''Commentary''

* Rashi. ''Commentary''

Numbers 30–32.

* Maimonides. '' Mishneh Torah''

* Maimonides. '' Mishneh Torah''

''Hilchot Sh'vuot (The Laws of Oaths)''

an

Egypt, circa 1170–1180. In, e.g., ''Mishneh Torah: Sefer Hafla'ah: The Book of Utterances''. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 12–237. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2003. . *Maimonides. '' The Guide for the Perplexed'', part 1, chapter 36; part 3, chapters 39, 40. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. In, e.g., Moses Maimonides. ''The Guide for the Perplexed''. Translated by Michael Friedländer, pages 51, 340, 344. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. . * Hezekiah ben Manoah. ''Hizkuni''. France, circa 1240. In, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. ''Chizkuni: Torah Commentary''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1021–35. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013. .

*

* Hezekiah ben Manoah. ''Hizkuni''. France, circa 1240. In, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. ''Chizkuni: Torah Commentary''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1021–35. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013. .

* *

*

* Moshe Alshich. ''Commentary on the Torah''.

* Moshe Alshich. ''Commentary on the Torah''.  * Chaim ibn Attar. ''Ohr ha-Chaim''. Venice, 1742. In Chayim ben Attar. ''Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah''. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1700–39. Brooklyn: Lambda Publishers, 1999. .

* Samson Raphael Hirsch. ''Horeb: A Philosophy of Jewish Laws and Observances''. Translated by Isidore Grunfeld, pages 276, 314–52. London: Soncino Press, 1962. Reprinted 2002 . Originally published as ''Horeb, Versuche über Jissroel's Pflichten in der Zerstreuung''. Germany, 1837.

* Chaim ibn Attar. ''Ohr ha-Chaim''. Venice, 1742. In Chayim ben Attar. ''Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah''. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1700–39. Brooklyn: Lambda Publishers, 1999. .

* Samson Raphael Hirsch. ''Horeb: A Philosophy of Jewish Laws and Observances''. Translated by Isidore Grunfeld, pages 276, 314–52. London: Soncino Press, 1962. Reprinted 2002 . Originally published as ''Horeb, Versuche über Jissroel's Pflichten in der Zerstreuung''. Germany, 1837.

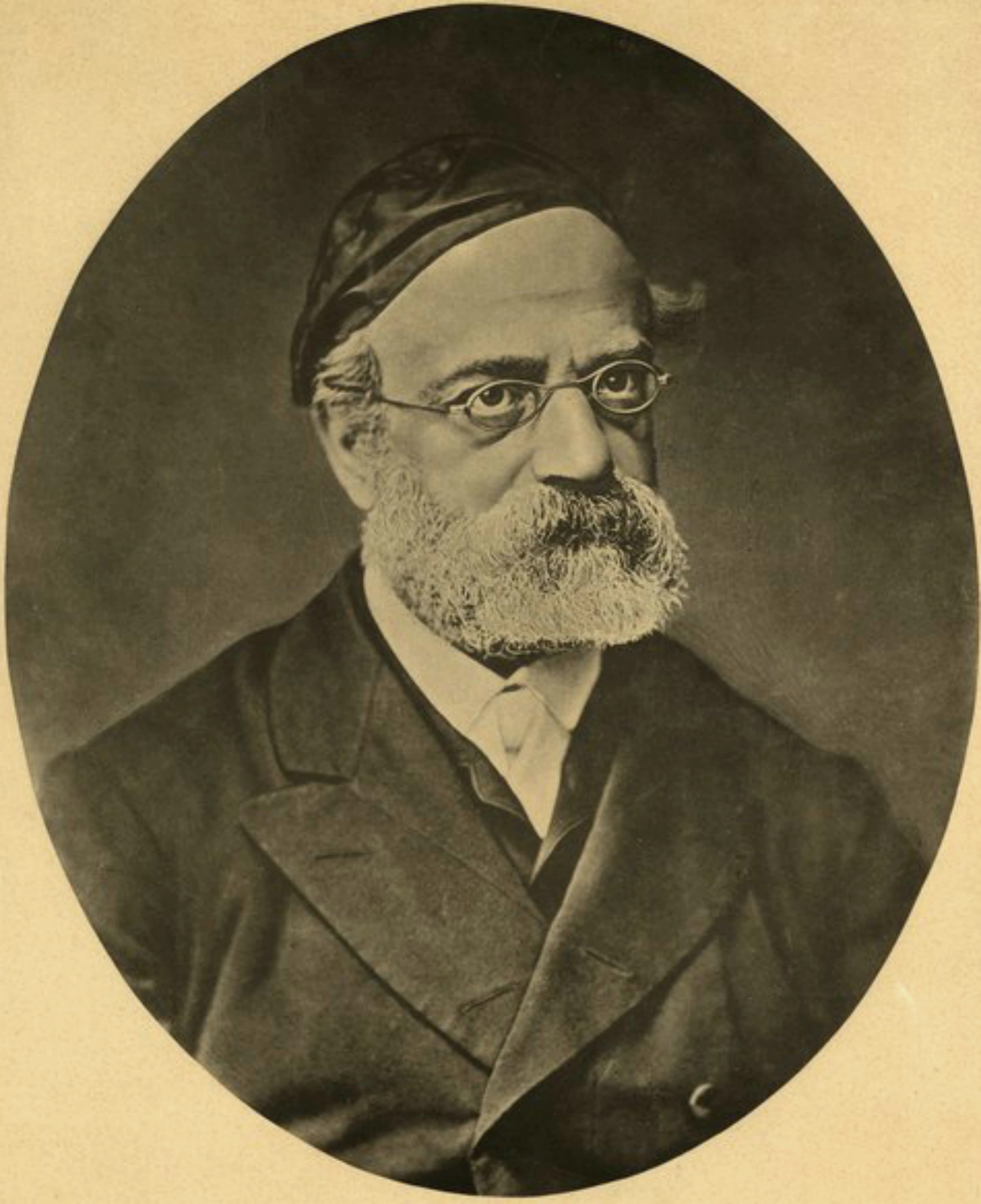

* Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal). ''Commentary on the Torah.'' Padua, 1871. In, e.g., Samuel David Luzzatto. ''Torah Commentary''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1113–20. New York: Lambda Publishers, 2012. .

* Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter. ''Sefat Emet''. Góra Kalwaria (Ger), Poland, before 1906. Excerpted in ''The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet''. Translated and interpreted by Arthur Green, pages 269–74. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998. . Reprinted 2012. .

*Alexander Alan Steinbach. ''Sabbath Queen: Fifty-four Bible Talks to the Young Based on Each Portion of the Pentateuch'', pages 132–35. New York: Behrman's Jewish Book House, 1936.

*Julius H. Greenstone. ''Numbers: With Commentary: The Holy Scriptures'', pages 311–37. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1939. Reprinted by Literary Licensing, 2011. .

*G. Henton Davies. “Vows.” In ''The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible'', volume 4, pages 792–94. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1962.

*J. Roy Porter. "The Succession of Joshua." In ''Proclamation and Presence: Old Testament Essays in Honour of Gwynne Henton Davies''. Edited by John I. Durham and J. Roy Porter, pages 102–32. London: SCM Press, 1970. .

*Carol L. Meyers. "The Roots of Restriction: Women in Early Israel." '' Biblical Archaeologist'', volume 41 (number 3) (September 1978).

*Philip J. Budd. ''Word Biblical Commentary: Volume 5: Numbers'', pages 320–47. Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1984. .

* Pinchas H. Peli. ''Torah Today: A Renewed Encounter with Scripture'', pages 189–93. Washington, D.C.: B'nai B'rith Books, 1987. .

* Michael Fishbane. ''Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel'', pages 82, 171, 258–60, 304. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985. .

* Jacob Milgrom. ''The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation'', pages 250–77, 488–96. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990. .

* Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal). ''Commentary on the Torah.'' Padua, 1871. In, e.g., Samuel David Luzzatto. ''Torah Commentary''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1113–20. New York: Lambda Publishers, 2012. .

* Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter. ''Sefat Emet''. Góra Kalwaria (Ger), Poland, before 1906. Excerpted in ''The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet''. Translated and interpreted by Arthur Green, pages 269–74. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998. . Reprinted 2012. .

*Alexander Alan Steinbach. ''Sabbath Queen: Fifty-four Bible Talks to the Young Based on Each Portion of the Pentateuch'', pages 132–35. New York: Behrman's Jewish Book House, 1936.

*Julius H. Greenstone. ''Numbers: With Commentary: The Holy Scriptures'', pages 311–37. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1939. Reprinted by Literary Licensing, 2011. .

*G. Henton Davies. “Vows.” In ''The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible'', volume 4, pages 792–94. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1962.

*J. Roy Porter. "The Succession of Joshua." In ''Proclamation and Presence: Old Testament Essays in Honour of Gwynne Henton Davies''. Edited by John I. Durham and J. Roy Porter, pages 102–32. London: SCM Press, 1970. .

*Carol L. Meyers. "The Roots of Restriction: Women in Early Israel." '' Biblical Archaeologist'', volume 41 (number 3) (September 1978).

*Philip J. Budd. ''Word Biblical Commentary: Volume 5: Numbers'', pages 320–47. Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1984. .

* Pinchas H. Peli. ''Torah Today: A Renewed Encounter with Scripture'', pages 189–93. Washington, D.C.: B'nai B'rith Books, 1987. .

* Michael Fishbane. ''Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel'', pages 82, 171, 258–60, 304. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985. .

* Jacob Milgrom. ''The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation'', pages 250–77, 488–96. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990. .

*

*

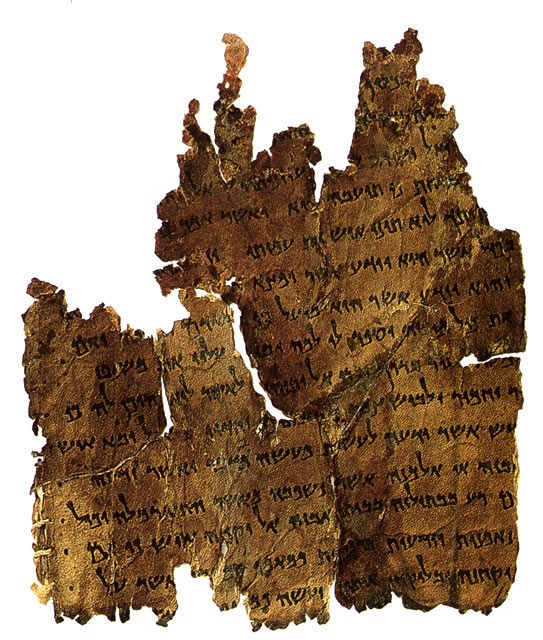

“The Law of Vows and Oaths (''Num''. 30, 3–16) in the ‘Zadokite Fragments’ and the ‘Temple Scroll.’”

''Revue de Qumrân'', volume 15 (number 1/2) (57/58) (September 1991): pages 199–214. * *

*

“Women and Children in Legal and Liturgical Texts from Qumran.”

''Dead Sea Discoveries'', volume 11 (number 2) (2004): pages 191–211. *Rachel R. Bovitz. “Haftarat Mattot: Jeremiah 1:1–2:3.” In ''The Women's Haftarah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Haftarah Portions, the 5 Megillot & Special Shabbatot''. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 200–05. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2004. . *Nili S. Fox. "Numbers." In ''The Jewish Study Bible''. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 343–49. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. . *''Professors on the Parashah: Studies on the Weekly Torah Reading'' Edited by Leib Moscovitz, pages 284–89. Jerusalem: *Suzanne A. Brody. "Gag Rule." In ''Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems'', page 101. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007. .

*

*Suzanne A. Brody. "Gag Rule." In ''Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems'', page 101. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007. .

*

“Scripture, Wisdom, and Authority in 4QInstruction: Understanding the Use of Numbers 30:8–9 in 4Q416.”

''Hebrew Studies'', volume 49 (2008): pages 87–98. *''The Torah: A Women's Commentary''. Edited by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, pages 989–1012. New York: URJ Press, 2008. . *R. Dennis Cole. "Numbers." In ''Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary''. Edited by

"The Prohibition of Oaths."

In ''A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus: Volume Four: Law and Love'', pages 182–234. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009. . * Terence E. Fretheim. “Numbers.” In ''The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha: An Ecumenical Study Bible''. Edited by

"Sexual and Religious Seduction (Numbers 25–31)."

In ''The Book of Numbers: A Critique of Genesis'', pages 135–58. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. . * William G. Dever. ''The Lives of Ordinary People in Ancient Israel: When Archaeology and the Bible Intersect'', page 246. Grand Rapids, Michigan: * Jonathan Haidt. ''The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion'', page 256. New York: Pantheon, 2012. . (prohibition of oath-breaking as an evolutionary advantage).

* Shmuel Herzfeld. "Women and Tallit." In ''Fifty-Four Pick Up: Fifteen-Minute Inspirational Torah Lessons'', pages 238–45. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House, 2012. .

* Jonathan Haidt. ''The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion'', page 256. New York: Pantheon, 2012. . (prohibition of oath-breaking as an evolutionary advantage).

* Shmuel Herzfeld. "Women and Tallit." In ''Fifty-Four Pick Up: Fifteen-Minute Inspirational Torah Lessons'', pages 238–45. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House, 2012. .

* Shlomo Riskin. ''Torah Lights: Bemidbar: Trials and Tribulations in Times of Transition'', pages 243–67.

* Shlomo Riskin. ''Torah Lights: Bemidbar: Trials and Tribulations in Times of Transition'', pages 243–67.

"The Great Educator: Moses understood that the way to correct mistakes lay in tireless and forward-thinking educational efforts."

'' The Jerusalem Report'', volume 24 (number 7) (July 15, 2013): page 47. * Erica Brown

“The only place that matters.”

'' The Jerusalem Report'', volume 24 (July 8, 2014). *Bill Rudolph

“Unifying Force: What Kind of Leader Do the Jewish People Really Want?”

'' The Jerusalem Report'', volume 26 (number 7) (July 27, 2015): page 47. * Jonathan Sacks. ''Lessons in Leadership: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible'', pages 227–31. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2015. .

*Jonathan Sacks. ''Essays on Ethics: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible'', pages 263–67. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2016. .

*

* Jonathan Sacks. ''Lessons in Leadership: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible'', pages 227–31. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2015. .

*Jonathan Sacks. ''Essays on Ethics: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible'', pages 263–67. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2016. .

*

Masoretic text and 1917 JPS translationHear the parashah chanted

Academy for Jewish Religion, New YorkAkhlah: The Jewish Children's Learning NetworkAleph Beta AcademyAmerican Jewish University — Ziegler School of Rabbinic StudiesAscent of SafedBar-Ilan UniversityChabad.orgeparsha.comG-dcastJewish Theological SeminaryMechon HadarMiriam AflaloMyJewishLearning.comOhr SameachOzTorah, Torah from AustraliaOz Ve Shalom — Netivot ShalomPardes from JerusalemProfessor James L. KugelProfessor Michael CarasikRabbi Jonathan SacksRabbiShimon.comRabbi Shmuel HerzfeldReconstructionist JudaismSephardic InstituteShiur.comTeach613.org, Torah Education at Cherry HillTheTorah.comTorah from DixieTorah.orgTorahVort.comUnion for Reform JudaismUnited Synagogue of Conservative JudaismYeshiva UniversityYeshivat Chovevei Torah

{{Weekly Torah Portions Weekly Torah readings in Av Weekly Torah readings in Tammuz (Hebrew month) Weekly Torah readings from Numbers

Matot, Mattot, Mattoth, or Matos ( — Hebrew for "tribes", the fifth word, and the first distinctive word, in the

Matot, Mattot, Mattoth, or Matos ( — Hebrew for "tribes", the fifth word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah

The term ''parashah'' ( he, פָּרָשָׁה ''Pārāšâ'', "portion", Tiberian , Sephardi , plural: ''parashot'' or ''parashiyot'', also called ''parsha'') formally means a section of a biblical book in the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Heb ...

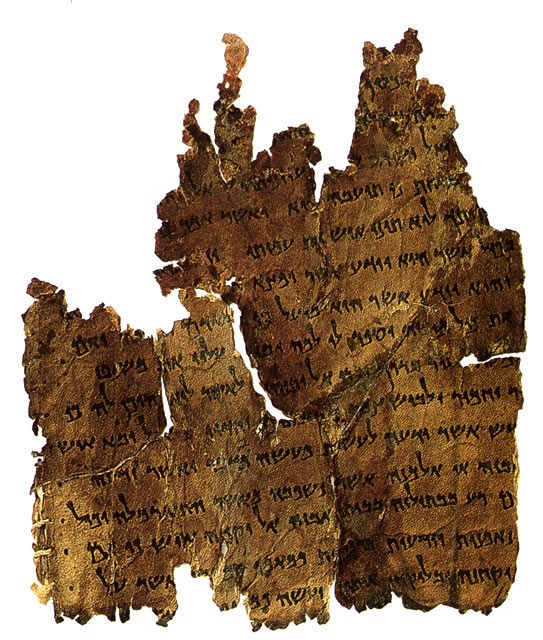

) is the 42nd weekly Torah portion (, ''parashah'') in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the ninth in the Book of Numbers. It comprises It discusses laws of vows, the destruction of Midianite towns, and negotiations of the Reubanites and Gadites to settle land outside of Israel.

The parashah is made up of 5,652 Hebrew letters, 1,484 Hebrew words, 112 verses, and 190 lines in a Torah Scroll (, ''Sefer Torah

A ( he, סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה; "Book of Torah"; plural: ) or Torah scroll is a handwritten copy of the Torah, meaning the five books of Moses (the first books of the Hebrew Bible). The Torah scroll is mainly used in the ritual of Tora ...

''). Jews generally read it in July or early August. The lunisolar Hebrew calendar contains up to 55 weeks, the exact number varying between 50 in common years and 54 or 55 in leap years. In some leap years (for example, 2014), parashah Matot is read separately. In most years (all coming years until 2035 in the Diaspora, until 2022 in Israel), parashah Matot is combined with the next parashah, Masei, to help achieve the number of weekly readings needed.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or , '' aliyot''.

First reading — Numbers 30:2–17

In the first reading (, ''aliyah''),Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

told the heads of the Israelite tribes God's

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

commands

Command may refer to:

Computing

* Command (computing), a statement in a computer language

* COMMAND.COM, the default operating system shell and command-line interpreter for DOS

* Command key, a modifier key on Apple Macintosh computer keyboards

* ...

about commitments (, ''nedarim

In Judaism, a neder (נדר, plural ''nedarim'') is a kind of vow or oath. The neder may consist of performing some act in the future (either once or regularly) or abstaining from a particular type of activity of the person's choice. The concept o ...

'', commonly translated, or some say mistranslated, as "vow

A vow ( Lat. ''votum'', vow, promise; see vote) is a promise or oath.

A vow is used as a promise, a promise solemn rather than casual.

Marriage vows

Marriage vows are binding promises each partner in a couple makes to the other during a wedd ...

s"). If a man made a vow to God, he was to carry out all that he promised. If a girl living in her father's household made a vow to God, and her father learned of it and did not object, her vow would stand. But if her father objected on the day that he learned of it, her vow would not stand, and God would forgive her. If she married while her vow was still in force, and her husband learned of it and did not object on the day that he found out, her vow would stand. But if her husband objected on the day that he learned of it, her vow would not stand, and God would forgive her. The vow of a widow or divorced woman was binding. If a married woman made a vow and her husband learned of it and did not object, then her vow would stand. But if her husband objected on the day that he learned of it, her vow would not stand, and God would forgive her. If her husband annulled one of her vows after the day that he learned of it, he would bear her guilt.

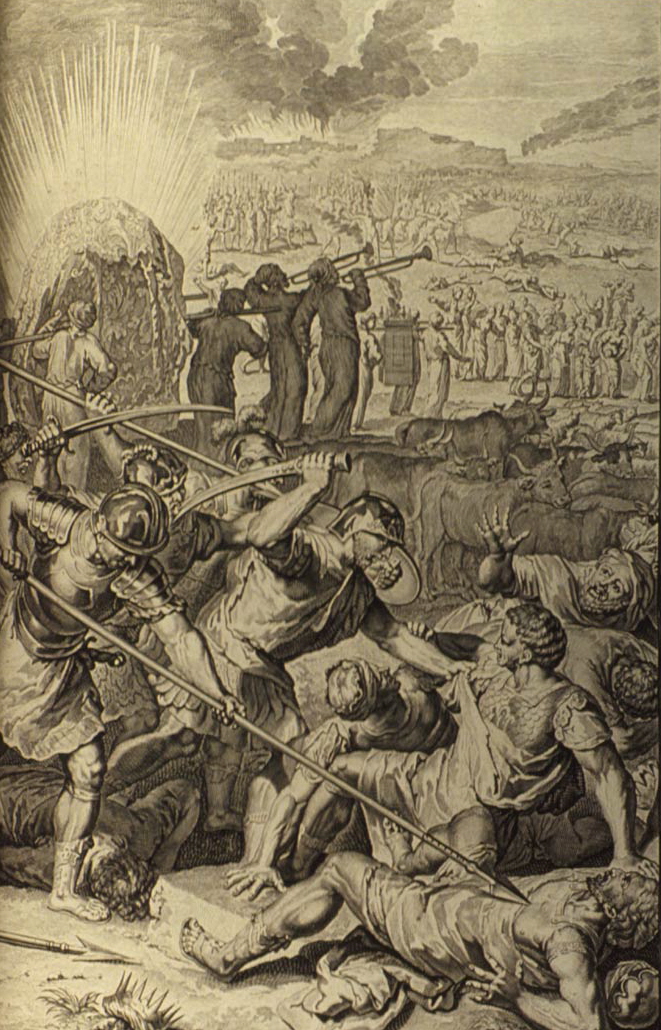

Second reading — Numbers 31:1–12

In the second reading (, ''aliyah''), God directed Moses to attack the Midianites, after which he would die. At Moses' direction, a thousand men from each tribe, with Phinehas son of Eleazar serving as priest on the campaign with the sacred utensils and trumpets, attacked Midian and slew every man, including fivekings

Kings or King's may refer to:

*Monarchs: The sovereign heads of states and/or nations, with the male being kings

*One of several works known as the "Book of Kings":

**The Books of Kings part of the Bible, divided into two parts

**The ''Shahnameh'' ...

of Midian and the prophet Balaam. The Israelites burned the Midianite towns, took the Midianite women and children captive, seized all their beasts and wealth as booty, and brought the captives and spoil to Moses, Eleazar, and the Israelite community at the steppes of Moab

Moab ''Mōáb''; Assyrian: 𒈬𒀪𒁀𒀀𒀀 ''Mu'abâ'', 𒈠𒀪𒁀𒀀𒀀

''Ma'bâ'', 𒈠𒀪𒀊 ''Ma'ab''; Egyptian: 𓈗𓇋𓃀𓅱𓈉 ''Mū'ībū'', name=, group= () is the name of an ancient Levantine kingdom whose territo ...

.

Third reading — Numbers 31:13–24

In the third reading (, ''aliyah''), Moses became angry with the army's commanders for sparing the women, as they were the ones who, at Balaam's bidding, had induced the Israelites to trespass against God in the sin of Peor. Moses then told the Israelites to kill every boy and every woman who had had sexual relations, but to spare the virgin girls. Moses directed the troops to stay outside the camp for 7 days after that, directed every one of them who had touched a corpse to cleanse himself on the third and seventh days, and directed them to cleanse everything made of cloth, hide, or wood. Eleazar told the troops to take any article that could withstand fire — gold, silver, copper, iron, tin, and lead — and pass them through fire to clean them, and to cleanse everything with thewater of lustration

The water of lustration or water of purification was the water created with the ashes of the red heifer, according to the instructions given by God to Moses and Aaron in the Book of Numbers.

Biblical references

The Hebrew Bible taught that any Isr ...

. Eleazar directed that on the seventh day they should wash their clothes and be clean, and thereafter be free to enter the camp.

Fourth reading — Numbers 31:25–41

In the fourth reading (, ''aliyah''), God told Moses to work with Eleazar and the family heads to inventory and divide the booty equally between the combatants and the rest of the community. God told them to exact a levy for God of one item in 500 of the warriors' captive persons and animals to be given to Eleazar, and one in every 50 of the other Israelites' captive persons and animals to be given to the Levites. The total booty came to 675,000 sheep, 72,000 head of cattle, 61,000 donkeys, and 32,000 virgin women, which Moses and Eleazar divided as God had commanded.Fifth reading — Numbers 31:42–54

In the fifth reading (, ''aliyah''), the Israelites' half of the booty came to 337,500 sheep, 36,000 head of cattle, 30,500 donkeys, and 16,000 virgin women, which Moses and Eleazar divided as God had commanded:The commanders of the troops told Moses that they had checked the warriors, and not one was missing, so they brought as an offering to God the gold that they came upon — armlets, bracelets, signet rings, earrings, and pendants — to make expiation for their persons before God. Moses and Eleazar accepted from them 16,750 shekels of gold, but the warriors in the ranks kept their booty for themselves.

Sixth reading — Numbers 32:1–19

In the sixth reading (, ''aliyah''), the Reubenites and the Gadites, who owned much cattle, noted that the lands of Jazer and Gilead on the east side of theJordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

suited cattle, and they approached Moses, Eleazar, and the chieftains and asked that those lands be given to them as a holding. Moses asked them if the rest of the Israelites were to go to war while they stayed on the east bank, and would that not undermine the enthusiasm of the rest of the Israelites for crossing into the Promised Land. Moses likened their position to that of the scouts who surveyed the land and then turned the minds of the Israelites against invading, thus incensing God and causing God to swear that none of the adult Israelites (except Caleb

Caleb (), sometimes transliterated as Kaleb ( he, כָּלֵב, ''Kalev'', ; Tiberian vocalization: Kālēḇ; Hebrew Academy: Kalev), is a figure who appears in the Hebrew Bible as a representative of the Tribe of Judah during the Israelites' ...

and Joshua) would see the land. They replied that they would build their sheepfolds and towns east of the Jordan and leave their children there, but then serve as shock-troops in the vanguard of the Israelites until the land was conquered and not seek a share of the land west of the Jordan.

Seventh reading — Numbers 32:20–42

In the seventh reading (, ''aliyah''), Moses then said that if they would do this, and every shock-fighter among them crossed the Jordan, then they would be clear before God and Israel, and this land would be their holding. But Moses continued, if they did not do as they promised, they would have sinned against God. Moses instructed Eleazar, Joshua, and the family heads of the Israelite tribes to carry out the agreement. So Moses assigned the Gadites, the Reubenites, and half the tribe of Manasseh lands on the east side of the Jordan. The Gadites and Reubenites built cities on the east side of Jordan, and some leaders of Manasseh conquered cities on the east of the Jordan so half the tribe of Manasseh could settle there.Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to thetriennial cycle

The Triennial cycle of Torah reading may refer to either

* The historical practice in ancient Israel by which the entire Torah was read in serial fashion over a three-year period, or

* The practice adopted by many Reform, Conservative, Reconstruct ...

of Torah reading read the parashah according to a different schedule.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:Numbers chapter 30

The Damascus Document of the Qumran community prohited a man from annulling an oath about which he did not know whether or not it should be carried out.In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in theserabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as '' semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form o ...

nic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:

Numbers chapter 30

TractatesNedarim

In Judaism, a neder (נדר, plural ''nedarim'') is a kind of vow or oath. The neder may consist of performing some act in the future (either once or regularly) or abstaining from a particular type of activity of the person's choice. The concept o ...

and Shevuot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of vows and oaths in and and

The Mishnah taught that saying any substitute for the formulas of a vow has the validity of a vow. If one says to another, "I am barred from you by a vow," or, "I am separated from you," or, "I am removed from you, in respect of anything that I might eat of yours or that I might taste of yours," the one vowing is prohibited. Rabbi Akiva was inclined to give a stringent ruling when a person says, "I am banned to you." The

The Mishnah taught that saying any substitute for the formulas of a vow has the validity of a vow. If one says to another, "I am barred from you by a vow," or, "I am separated from you," or, "I am removed from you, in respect of anything that I might eat of yours or that I might taste of yours," the one vowing is prohibited. Rabbi Akiva was inclined to give a stringent ruling when a person says, "I am banned to you." The Gemara

The Gemara (also transliterated Gemarah, or in Yiddish Gemo(r)re; from Aramaic , from the Semitic root ג-מ-ר ''gamar'', to finish or complete) is the component of the Talmud comprising rabbinical analysis of and commentary on the Mishnah w ...

taught that a vow (, ''neder'') makes a ''thing'' forbidden to a person, while an oath (, ''shevuah'') binds a ''person'' to a relationship to a thing.

Rabbi Akiva taught that vows are a fence for self-restraint. But the Jerusalem Talmud asked whether it was not enough that the Torah had forbidden us things that we should seek to forbid yet other things to ourselves. The Gemara discouraged vows. Rabbi Nathan taught that one who vows is as if he built a high place, and he who fulfils a vow is as if he sacrificed on that high place. And the Gemara deduced from Rabbi Nathan's teaching that it is meritorious to seek absolution from vows. And a Midrash told the tale of King Jannai, who owned two thousand towns, all of which were destroyed because of true oaths. A man would swear to his friend that he would eat such-and-such a food at such-and-such a place and drink such-and-such a drink at such-and-such a place. And they would go and fulfill their oaths and would be destroyed (for swearing to trifles). The Midrash concluded that if this was the fate of people who swore truthfully, how much more would swearing to a falsehood lead to destruction.

Reasoning from “He shall not profane his word,” the Tosefta concluded that one should not treat one’s words as profane and unconsecrated. Even though there were vows that the Rabbis had ruled were not binding, the Tosefta taught that one should not make even such a vow with the plan of annulling it, as says, “He shall not profane his word.” The Tosefta also deduced from that even a sage could not annul his own vow for himself.

The Mishnah taught that the law of the dissolution of vows hovers in the air and has nothing on which to rest in the Biblical text. Rav Judah said that Samuel found the Scriptural basis for the law of the dissolution of vows in the words of "''he'' shall not break his word," which teaches that "he" — the vower — may not break the vow, but ''others'' might dissolve it for him. The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that a Sage could annul a vow retroactively.

The Sifre asked why set forth the effectiveness of nazirite vows, when the general rule of would suffice to teach that all vows — including nazirite vows — are binding. The Sifre explained that warned that a person making a nazirite vow would be bound to at least a 30-day nazirite period.

Rabbah bar bar Hana told of how an Arab merchant took him to see Mount Sinai, where he saw scorpions surround it, and they stood like white donkeys. Rabbah bar bar Hana heard a Heavenly Voice expressing regret about making an oath and asking who would annul the oath. When Rabbah bar bar Hana came before the Rabbis, they told him that he should have annulled the oath. But Rabbah bar bar Hana thought that perhaps it was the oath in connection with the Flood, where in God promised never to destroy the world again with another flood. The Rabbis replied that if that had been the oath, the Heavenly Voice would not have expressed regret.

Rava Rava may refer to:

Biographical

* Bishnu Prasad Rabha, multifaceted artist and revolutionary singer of Assam

* Abba ben Joseph bar Ḥama (born 280), a Jewish Talmudist who lived in Babylonia, always known by the honorific name ''Raba,'' ''Rava, ...

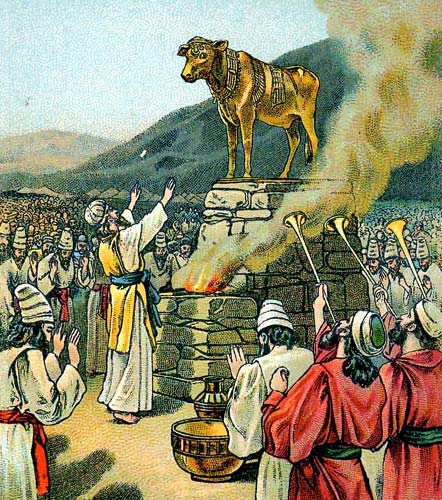

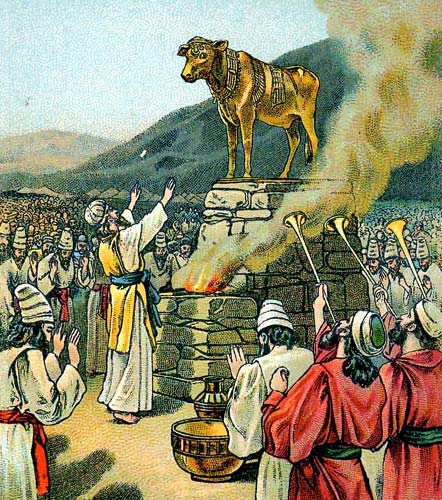

employed to interpret which says: "And Moses besought (, ''va-yechal'') the Lord his God" in connection with the incident of the Golden Calf

According to the Bible, the golden calf (עֵגֶל הַזָּהָב '' ‘ēgel hazzāhāv'') was an idol (a cult image) made by the Israelites when Moses went up to Mount Sinai. In Hebrew, the incident is known as ''ḥēṭə’ hā‘ēgel'' ...

. Rava noted that uses the term "besought" (, ''va-yechal''), while uses the similar term "break" (, yacheil) in connection with vows. Transferring the use of to Rava reasoned that meant that Moses stood in prayer before God until Moses annulled for God God's vow to destroy Israel, for a master had taught that while people cannot break their vows, others may annul their vows for them. Similarly, Rabbi Berekiah taught in the name of Rabbi Helbo

Rabbi Helbo (רבי חלבו) was an amoraim, amora who flourished about the end of the 3rd century, and who is frequently mentioned in both Talmuds.

It seems that Helbo lived at first in Babylonia, where he studied under Rav Huna, the head of the ...

in the name of Rabbi Isaac that Moses absolved God of God's vow. When the Israelites made the Golden Calf, Moses began to persuade God to forgive them, but God explained to Moses that God had already taken an oath in that "he who sacrifices to the gods ... shall be utterly destroyed," and God could not retract an oath. Moses responded by asking whether God had not granted Moses the power to annul oaths in by saying, "When a man vows a vow to the Lord, or swears an oath to bind his soul with a bond, ''he'' shall not break his word," implying that while he himself could not break his word, a scholar could absolve his vow. So Moses wrapped himself in his cloak and adopted the posture of a sage, and God stood before Moses as one asking for the annulment of a vow.

Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai

Shimon bar Yochai ( Zoharic Aramaic: שמעון בר יוחאי, ''Shim'on bar Yoḥai'') or Shimon ben Yochai (Mishnaic Hebrew: שמעון בן יוחאי, ''Shim'on ben Yoḥai''), also known by the acronym Rashbi, was a 2nd-century ''tannaiti ...

taught that just as the texts "He shall not break his word" in and "Defer not to pay it" in Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes (; hbo, קֹהֶלֶת, Qōheleṯ, grc, Ἐκκλησιαστής, Ekklēsiastēs) is one of the Ketuvim ("Writings") of the Hebrew Bible and part of the Wisdom literature of the Christian Old Testament. The title commonly use ...

apply to vows, so they also apply to valuations, and thus Moses exhorts the Israelites in "When a man shall clearly utter a vow of persons to the Lord, according to your valuation . . . ."

Rabbi Eleazar interpreted to teach that one should not treat lightly, because on account of it were the members of the Great Sanhedrin of Zedekiah slain. When King Jeconiah of Judah was exiled, King

Rabbi Eleazar interpreted to teach that one should not treat lightly, because on account of it were the members of the Great Sanhedrin of Zedekiah slain. When King Jeconiah of Judah was exiled, King Nebuchadnezzar

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''Nəḇūḵaḏneʾṣṣar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

of Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

appointed Zedekiah King of Judah (as reported in ). Zedekiah stood so high in King Nebuchadnezzar’s favor that he could enter and leave King Nebuchadnezzar’s presence without permission. One day, Zedekiah entered Nebuchadnezzar’s presence and found him tearing the flesh of a hare

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores, and live solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are able to fend for themselves shortly after birth. The ge ...

and eating it while it was still alive. Nebuchadnezzar asked Zedekiah to swear that he would not disclose this, and Zedekiah swore. Subsequently, the five kings over whom Nebuchadnezzar had appointed Zedekiah were sitting and sneering at Nebuchadnezzar in Zedekiah’s presence, and they told Zedekiah that the kingship did not belong to Nebuchadnezzar but to Zedekiah, as Zedekiah descended from David. So Zedekiah too sneered at Nebuchadnezzar and disclosed that once he saw him tear the flesh of a live hare and eat it. The five kings immediately told Nebuchadnezzar, who forthwith came to Antioch, where the members of the Great Sanhedrin went to meet him. Nebuchadnezzar asked them to expound the Torah to him, and they began to read it chapter by chapter. When they reached “When a man vows a vow . . . he shall not break his word,” Nebuchadnezzar asked them whether a person could retract a vow. They replied that such a person must go to a Sage to absolve the person of the vow. Nebuchadnezzar told them that they must have absolved Zedekiah of the oath that he swore to him, and he immediately ordered them to be placed on the ground, as reports, “They sit upon the ground, and keep silence, the elders of the daughter of Zion.” To avail them in their peril, they then began to recount the merit of Abraham, who in said, “I am but dust and ashes”; thus continues, “They have girded themselves with sackcloth.” They began to recount the merit of Jacob, of whom says, “He put sackcloth upon his loins.” But Nebuchadnezzar caused the members of the Great Sanhedrin to have their hair bound to the tails of their horses as the horses were driven from Jerusalem to Lydda, killing the members of the Great Sanhedrin in the process. Thus continues, “the virgins of Jerusalem eferring to the members of the Great Sanhedrinhang down their heads to the ground.”

Interpreting the law of vows in the Mishnah taught that a young child's vows were not binding. When a girl turned 11 years old and throughout the year thereafter, they examined to determine whether she was aware of the significance of her vows. The vows of a girl 12 years old or older stood without examination. When a boy turned 12 years old and throughout the year thereafter, they examined to determine whether he was aware of the significance of his vows. The vows of a boy 13 years old or older stood without examination. For girls below age 11 or boys below age 12, even if they said that they knew in honor of Whose Name they vowed, their vows and dedications were not valid. After girls turned 12 or boys turned 13, even though they said that they did not know in the honor of Whose Name they vowed, their vows and dedications stood. The Sifri Zutta told that once a youth told Rabbi Akiva that the youth had dedicated a shovel. Rabbi Akiva asked the youth whether perhaps he had sanctified his shovel to the sun or the moon. The youth replied that Rabbi Akiva did not need to worry, as the youth had sanctified it to the One Who had created them. Rabbi Akiva told the youth that his vows were valid.

The Mishnah taught that a father who did not say anything to annul his daughter's vow because he did not know that he had the power to do so could release the vow when he learned that he did have that power. Similarly, the Sages taught that a father who did not know that a statement was a vow could release that vow when he learned that it was a vow (although Rabbi Meir said that he could not).

The Sifri Zutta taught that if a father annulled his daughter's vow without her knowing that he had done so, and she deliberately transgressed the vow, she was nonetheless not liable to penalty, because says, “the Lord will forgive her.”

Reading “But every vow of a widow and of a divorcee . . . shall be binding on her,” the Mishnah taught that if she said, “I will be a nazirite after thirty days,” even if she married within the thirty days, her husband could not annul her vow. And if she vowed on one day, divorced on the same day, and remarried on the same day, the husband could not annul her vow. The Mishnah stated the general rule: Once she had gone into her own domain even for a single hour, her husband could not annul her vows.

The Mishnah taught that a father or husband could annul vows of self-denial (which, in the words of "afflict the soul"), such as bathing and adorning oneself. But Rabbi Jose said that these were not vows of self-denial. Rabbi Jose taught that vows of self-denial that a father or husband could annul include if she said, "''konam'' (that is, prohibited) be the produce of the whole world to me." Rabbi Jose taught that if she said, "''konam'' be the produce of this country to me," he could not annul, as he could bring her to a different country. And if she said, "''konam'' be the fruits of this shopkeeper to me," he could not annul, unless that shopkeeper was his only source of sustenance, in which case he could annul.

The Gemara deduced from the words "between a man and his wife, between a father and his daughter" in that in addition to vows of self-denial, a husband could also annul vows that affected the relationship between husband and wife.

A Midrash taught that just as a husband could annul only vows that would cause personal affliction between the spouses, so too, a father could annul only vows that would cause personal affliction between him and his daughter.

The Mishnah taught that in the case of a betrothed young woman, her father and her fiancé could annul her vows, if they both did so. If her father but not her fiancé attempted to annul her vow, or if her fiancé but not her father attempted to annul her vow, it was not annulled. And the Mishnah taught that it went without saying that her vow was not annulled if one of them confirmed it.

The Mishnah taught that one could annul vows on the Sabbath.

Numbers chapter 31

A Midrash deduced from the proximity of the report in that "the children of Israel took captive the women of Midian . . . and all their cattle" with the report of that "the children of Reuben and the children of Gad had a very great multitude of cattle" that God cast the Midianites down before Israel so that the Reubenites and Gadites might grow rich. The Midrash cited this turn of events as proof of the words of Psalm that "God is judge; He puts down one, and lifts up another." Noting that in God told Joshua, "As I was with Moses, so I will be with you," the Rabbis asked why Joshua lived only 110 years (as reported in and ) and not 120 years, as Moses did (as reported in ). The Rabbis explained that when God told Moses in to "avenge the children of Israel of the Midianites; afterward shall you be gathered to your people," Moses did not delay carrying out the order, even though God told Moses that he would die thereafter. Rather, Moses acted promptly, as reports: "And Moses sent them." When God directed Joshua to fight against the 31 kings, however, Joshua thought that if he killed them all at once, he would die immediately thereafter, as Moses had. So Joshua dallied in the wars against the Canaanites, as reports: "Joshua made war a long time with all those kings." In response, God shortened his life by ten years. The Rabbis differed about the meaning of "the holy vessels" inRabbi Johanan Yohanan, Yochanan and Johanan are various transliterations to the Latin alphabet of the Hebrew male given name ('), a shortened form of ('), meaning "YHWH is gracious".

The name is ancient, recorded as the name of Johanan, high priest of the Se ...

deduced from the reference of to "the holy garments of Aaron" that refers to the priestly garments containing the Urim and Thummim when it reports that "Moses sent . . . Phinehas the son of Eleazar the priest, to the war, with the holy vessels." But the Midrash concluded that refers to the Ark of the Covenant

The Ark of the Covenant,; Ge'ez: also known as the Ark of the Testimony or the Ark of God, is an alleged artifact believed to be the most sacred relic of the Israelites, which is described as a wooden chest, covered in pure gold, with an e ...

, to which refers when it says, "the service of the holy things."

Numbers chapter 32

A Midrash deduced from that the Reubenites and Gadites were rich, possessing large amounts of cattle, but they loved their possessions so much that they separated themselves from their fellow Israelites and settled outside the Land of Israel. As a result, they became the first tribes to be taken away into exile, as1 Chronicles

The Book of Chronicles ( he, דִּבְרֵי־הַיָּמִים ) is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Chronicles) in the Christian Old Testament. Chronicles is the final book of the Hebrew Bible, concluding the third sect ...

reports, " Tillegath-pilneser king of Assyria ... carried ... away ... the Reubenites, and the Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh."

The Tanna Devei Eliyahu taught that if you live by the commandment establishing the Sabbath (in (20:8 in the NJPS) and (5:12 in the NJPS)), then (in the words of ) “The Lord has sworn by His right hand, and by the arm of His strength: ‘Surely I will no more give your corn to be food for your enemies.” If, however, you transgress the commandment, then it will be as in when “the Lord’s anger was kindled in that day, and He swore, saying: ‘Surely none of the men . . . shall see the land.’”

Similarly, a Midrash taught that the Reubenites and the Gadites cherished their property more than human life, putting their cattle before their children when they told Moses in "We will build sheepfolds here for our cattle, and cities for our little ones." Moses told them that their priorities were wrong and that they should rather do the more important things first, when Moses told them in "Build you cities for your little ones, and folds for your sheep." The Midrash saw in their different priorities application of the words of "A wise man's understanding is at his right hand" — applying to Moses — and "A fool's understanding at his left" — applying to the Reubenites and the Gadites. God told the Reubenites and the Gadites that as they showed greater love for their cattle than for human souls, there would be no blessing in it for them. The Midrash thus saw in their fate application of the words of "An estate may be gotten hastily at the beginning; but the end thereof shall not be blessed," and the words of "Do not weary yourself to be rich; cease from your own wisdom."

In the Mishnah, Rabbi Meir noted that an29

stated the same condition in both positive and negative formulations. states the condition in the positive: "And Moses said to them, if the children of Gad and the children of Reuben will pass with you over the Jordan, . . . then you shall give them the land of Gilead for a possession." And states the same condition in the negative: "But if they will not pass over with you armed, then they shall have possessions among you in the land of Canaan." Rabbi Meir deduced that every stipulation must be stated in both the negative and positive formulations, like the condition of the children of Gad and the children of Reuben in an

or it is not a binding stipulation. Rabbi Hanina ben Gamaliel II maintained, however, that Moses stated the matter both ways because he needed to do so to be understood; otherwise one might have concluded that the Gadites and Reubenites would receive no inheritance even in the land of Canaan.

The Mishnah taught that those who removed from the Temple coins collected in the shekel tax could not enter the chamber wearing a bordered cloak or shoes or sandals or tefillin or an amulet, lest if they became rich people might say that they became rich from money in the chamber. The Mishnah thus taught that it is one’s duty to appear to be free of blame before others as before God, as says: “And you shall be guiltless before the Lord and before Israel.”

Similarly, the Tosefta cited “You shall be clear before the Lord, and before Israel,” to support the proposition that while out collecting charity, charity collectors were not permitted to separate their own money from that which they collected for charity by placing their own money in a separate purse, lest it appear that they were stealing for themselves some of the money that they gathered for charity. While collecting for charity, a charity collector could not take for personal use money from a friend who owed the charity collector money, and a charity collector could not take for personal use money that the charity collector found on the road.

The Sages taught in a Baraita that they honored the memory of the family that baked the Temple

The Mishnah taught that those who removed from the Temple coins collected in the shekel tax could not enter the chamber wearing a bordered cloak or shoes or sandals or tefillin or an amulet, lest if they became rich people might say that they became rich from money in the chamber. The Mishnah thus taught that it is one’s duty to appear to be free of blame before others as before God, as says: “And you shall be guiltless before the Lord and before Israel.”

Similarly, the Tosefta cited “You shall be clear before the Lord, and before Israel,” to support the proposition that while out collecting charity, charity collectors were not permitted to separate their own money from that which they collected for charity by placing their own money in a separate purse, lest it appear that they were stealing for themselves some of the money that they gathered for charity. While collecting for charity, a charity collector could not take for personal use money from a friend who owed the charity collector money, and a charity collector could not take for personal use money that the charity collector found on the road.

The Sages taught in a Baraita that they honored the memory of the family that baked the Temple showbread

Showbread ( he, לחם הפנים ''Leḥem haPānīm'', literally: "Bread of the Faces"), in the King James Version: shewbread, in a biblical or Jewish context, refers to the cakes or loaves of bread which were always present, on a specially-de ...

, for they never allowed fine bread to be found in their children's hands. And the Sages honored the memory of the family that made the Temple incense, for they never allowed a bride of their house to go about perfumed. In both cases, the families did so to fulfill the command of that "you shall be clear before the Lord and before Israel" — meaning that people should act so as to avoid even the appearance of transgression.

Commandments

According to Maimonides

Maimonides cited a verse in the parashah for one negativecommandment

Commandment may refer to:

* The Ten Commandments

* One of the 613 mitzvot of Judaism

* The Great Commandment

* The New Commandment

* ''Commandment'' (album), a 2007 album by Six Feet Under

* ''Commandments'' (film), a 1997 film starring Aidan Qui ...

:

*Not to transgress in matters that one has forbidden oneself

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there is 1 positive and 1 negative commandment in the parashah. *The precept of the law of nullifying vows *That we should not break our word in vows that we make

Haftarah

The haftarah for parashah Matot is The haftarah is the first of three readings of admonition leading up to Tisha B'Av. When parashah Matot is combined with parashah Masei (as it will be until 2035), the haftarah is the haftarah for parashah Masei: *for Ashkenazi Jews: & *for Sephardi Jews: &

Summary

The haftarah in begins by identifying its words as those of Jeremiah the son of Hilkiah, a priest in Anathoth in the land of Benjamin, to whom God's word came in the thirteenth year of the reign ofJosiah

Josiah ( or ) or Yoshiyahu; la, Iosias was the 16th king of Judah (–609 BCE) who, according to the Hebrew Bible, instituted major religious reforms by removing official worship of gods other than Yahweh. Josiah is credited by most biblical s ...

the son of Amon as king of Judah, in the reign of Josiah's son Jehoiakim, and through the eleventh year of the reign of Josiah's son Zedekiah, when Jerusalem was carried away captive.

God's word came to Jeremiah to say that before God formed him in the womb, God knew him, sanctified him, and appointed him a prophet to the nations. Jeremiah protested that he could not speak, for he was a child, but God told him not to fear, for he would go wherever God would send him, say whatever God would command him to say, and God would be with him to deliver him. Then God touched Jeremiah's mouth and said that God had put words in his mouth and set him over the nations to root out and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant. God asked Jeremiah what he saw, he replied that he saw the rod of an almond tree, and God said that he had seen well, for God watches over God's word to perform it.

God's word came to Jeremiah a second time to ask what he saw, he replied that he saw a seething pot tipping from the north, and God said that out of the north evil would break forth upon all Israel. For God would call all the kingdoms of the north to come, and they would set their thrones at Jerusalem's gate, against its walls, and against the cities of Judah. God would utter God's judgments against Judah, as its people had forsaken God and worshipped the work of their own hands. God thus directed Jeremiah to gird his loins, arise, and speak to the Judean people all that God commanded, for God had made Jeremiah a fortified city, an iron pillar, and brazen walls against the land of Judah, its rulers, its priests, and its people. They would fight against him, but they would not prevail, for God would be with him to deliver him.

God's word came to Jeremiah to tell him to go and cry in the ears of Jerusalem that God remembered the affection of her youth, her love as a bride, how she followed God in the wilderness. Israel was God's hallowed portion and God's first-fruits, and all that devoured Israel would be held guilty and evil would come upon them.

Connection to the special Sabbath

The first of three readings of admonition leading up to Tisha B'Av, the haftarah admonishes Judah and Israel in And then in the haftarah concludes with consolation. The Gemara taught that Jeremiah wrote the book of Lamentations, and as Jews read Lamentations on Tisha B'Av, this probably accounts for why a selection from Jeremiah begins the series of haftarot of admonition. Michael Fishbane, ''The JPS Bible Commentary: Haftarot'' (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2002), page 262.Notes

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:Biblical

* (vow). * (vows). * (vows); (vows); (valuation of vows). * (vows); (trumpets); (the spies); (sharing with the priests and Levites); (vow); (Midianites). * (Reubenites and Gadites); (vows). * (Reubenites and Gadites); (Reubenites and Gadites). * (Midianites). *1 Samuel

The Book of Samuel (, ''Sefer Shmuel'') is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Samuel) in the Old Testament. The book is part of the narrative history of Ancient Israel called the Deuteronomistic history, a series of books (Josh ...

(vow); (division of booty).

* (God avenges); (paying vows); (the righteous shall inherit the land); (men call their lands after their own names); (paying vows); (washing); (performing vows); (value of lives); (vengeance belongs to God); (Peor); (value of lives).

* (vows).

Early nonrabbinic

* Josephus, ''Antiquities of the Jews

''Antiquities of the Jews'' ( la, Antiquitates Iudaicae; el, Ἰουδαϊκὴ ἀρχαιολογία, ''Ioudaikē archaiologia'') is a 20-volume historiographical work, written in Greek, by historian Flavius Josephus in the 13th year of the re ...

'4:7:1, 3.

Circa 93–94. In, e.g., ''The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition''. Translated by William Whiston, pages 113–14. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. . *

Matthew

Matthew may refer to:

* Matthew (given name)

* Matthew (surname)

* ''Matthew'' (ship), the replica of the ship sailed by John Cabot in 1497

* ''Matthew'' (album), a 2000 album by rapper Kool Keith

* Matthew (elm cultivar), a cultivar of the Ch ...

Antioch, circa 80–90 CE. (vows).

* Qur'an: 2:224–226; 5:89; 9:12–13; 16:91–92, 94; 66:2 (vows).

Classical rabbinic

* MishnahShabbat 24:5

Nedarim 1:1–11:11

Gittin 4:7

Kiddushin 3:4; Shevuot 1:1–8:6

Avot 3:13.

Land of Israel, circa 200 C.E. In, e.g., ''The Mishnah: A New Translation''. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 330, 406–30, 492–93, 620–39, 680. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. . * Tosefta: Peah 4:15; Terumot 5:8; Nedarim 1:1–7:8; Sotah 7:17; Shevuot 1:1–6:7; Keritot 4:15. Land of Israel, circa 250 C.E. In, e.g., ''The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction''. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 73, 161, 208, 785–805, 864; volume 2, pages 1219–44, 1571. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. . * Jerusalem Talmud: Terumot 35b; Bikkurim 6a; Shabbat 45a; Pesachim 74b; Chagigah 7a–b; Nedarim 1a–42b; Nazir 1a, 17a; Sotah 9a; Shevuot 1a–49a. Tiberias, Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. In, e.g., ''Talmud Yerushalmi''. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 7, 12, 14, 19, 27, 33–34, 36, 46. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008–2019. And in, e.g., ''The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary''. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009. . * Genesis Rabbahbr>1:15

85:14. Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Genesis''. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 13–14, 411–12, 483–84; volume 2, page 799. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

*Babylonian Talmud

*Babylonian TalmudBerakhot 8b

Babylonia, 6th Century. In, e.g., ''Talmud Bavli''. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Medieval

* Rashi. ''Commentary''

* Rashi. ''Commentary''Numbers 30–32.

Troyes

Troyes () is a commune and the capital of the department of Aube in the Grand Est region of north-central France. It is located on the Seine river about south-east of Paris. Troyes is situated within the Champagne wine region and is near to ...

, France, late 11th Century. In, e.g., Rashi. ''The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated''. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 4, pages 369–401. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. .

* Rashbam. ''Commentary on the Torah''. Troyes, early 12th century. In, e.g., ''Rashbam's Commentary on Leviticus and Numbers: An Annotated Translation''. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, pages 285–92. Providence: Brown Judaic Studies, 2001. .

* Numbers Rabbah 22:1–9. 12th Century. In, e.g., ''Midrash Rabbah: Numbers''. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 6, pages 853–62. London: Soncino Press, 1939. .

* Abraham ibn Ezra. ''Commentary'' on the Torah. Mid-12th century. In, e.g., ''Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Numbers (Ba-Midbar)''. Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, pages 238–55. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 1999. .

* Maimonides. '' Mishneh Torah''

* Maimonides. '' Mishneh Torah''''Hilchot Sh'vuot (The Laws of Oaths)''

an

Egypt, circa 1170–1180. In, e.g., ''Mishneh Torah: Sefer Hafla'ah: The Book of Utterances''. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 12–237. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2003. . *Maimonides. '' The Guide for the Perplexed'', part 1, chapter 36; part 3, chapters 39, 40. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. In, e.g., Moses Maimonides. ''The Guide for the Perplexed''. Translated by Michael Friedländer, pages 51, 340, 344. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. .

* Hezekiah ben Manoah. ''Hizkuni''. France, circa 1240. In, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. ''Chizkuni: Torah Commentary''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1021–35. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013. .

*

* Hezekiah ben Manoah. ''Hizkuni''. France, circa 1240. In, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. ''Chizkuni: Torah Commentary''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1021–35. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013. .

*Nachmanides

Moses ben Nachman ( he, מֹשֶׁה בֶּן־נָחְמָן ''Mōše ben-Nāḥmān'', "Moses son of Nachman"; 1194–1270), commonly known as Nachmanides (; el, Ναχμανίδης ''Nakhmanídēs''), and also referred to by the acronym Ra ...

. ''Commentary on the Torah''. Jerusalem, circa 1270. In, e.g., ''Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah: Numbers.'' Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 4, pages 344–81. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1975. .

*

*Zohar

The ''Zohar'' ( he, , ''Zōhar'', lit. "Splendor" or "Radiance") is a foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah (the five ...

part 3, page 241b. Spain, late 13th Century. In, e.g., ''The Zohar''. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

* Jacob ben Asher (Baal Ha-Turim). ''Rimze Ba'al ha-Turim''. Early 14th century. In, e.g., ''Baal Haturim Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers''. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, edited and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 4, pages 1711–43. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2003. .

*Jacob ben Asher. ''Perush Al ha-Torah''. Early 14th century. In, e.g., Yaakov ben Asher. ''Tur on the Torah''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1202–15. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2005. .

*Isaac ben Moses Arama Isaac ben Moses Arama ( 1420 – 1494) was a Spanish rabbi and author. He was at first principal of a rabbinical academy at Zamora (probably his birthplace); then he received a call as rabbi and preacher from the community at Tarragona, and later ...

. ''Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac)''. Late 15th century. In, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. ''Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah''. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 791–95. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001. .

Modern

* Isaac Abravanel. ''Commentary on the Torah''. Italy, between 1492–1509. In, e.g., ''Abarbanel: Selected Commentaries on the Torah: Volume 4: Bamidbar/Numbers''. Translated and annotated by Israel Lazar, pages 318–24. Brooklyn: CreateSpace, 2015. . * Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno. ''Commentary on the Torah''. Venice, 1567. In, e.g., ''Sforno: Commentary on the Torah''. Translation and explanatory notes by Raphael Pelcovitz, pages 802–13. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. .Safed

Safed (known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardi Hebrew, Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation, Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), i ...

, circa 1593. In, e.g., Moshe Alshich. ''Midrash of Rabbi Moshe Alshich on the Torah''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 926–40. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2000. .

* Saul Levi Morteira. “Eulogy for Moses de Mercado.” Budapest, 1652. In Marc Saperstein. ''Exile in Amsterdam: Saul Levi Morteira’s Sermons to a Congregation of “New Jews,”'' pages 536–43. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

Press, 2005. .

* Shabbethai Bass. ''Sifsei Chachamim''. Amsterdam, 1680. In, e.g., ''Sefer Bamidbar: From the Five Books of the Torah: Chumash: Targum Okelos: Rashi: Sifsei Chachamim: Yalkut: Haftaros'', translated by Avrohom Y. Davis, pages 534–89. Lakewood Township, New Jersey: Metsudah Publications, 2013.

* Chaim ibn Attar. ''Ohr ha-Chaim''. Venice, 1742. In Chayim ben Attar. ''Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah''. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1700–39. Brooklyn: Lambda Publishers, 1999. .

* Samson Raphael Hirsch. ''Horeb: A Philosophy of Jewish Laws and Observances''. Translated by Isidore Grunfeld, pages 276, 314–52. London: Soncino Press, 1962. Reprinted 2002 . Originally published as ''Horeb, Versuche über Jissroel's Pflichten in der Zerstreuung''. Germany, 1837.

* Chaim ibn Attar. ''Ohr ha-Chaim''. Venice, 1742. In Chayim ben Attar. ''Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah''. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1700–39. Brooklyn: Lambda Publishers, 1999. .

* Samson Raphael Hirsch. ''Horeb: A Philosophy of Jewish Laws and Observances''. Translated by Isidore Grunfeld, pages 276, 314–52. London: Soncino Press, 1962. Reprinted 2002 . Originally published as ''Horeb, Versuche über Jissroel's Pflichten in der Zerstreuung''. Germany, 1837.

* Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal). ''Commentary on the Torah.'' Padua, 1871. In, e.g., Samuel David Luzzatto. ''Torah Commentary''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1113–20. New York: Lambda Publishers, 2012. .

* Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter. ''Sefat Emet''. Góra Kalwaria (Ger), Poland, before 1906. Excerpted in ''The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet''. Translated and interpreted by Arthur Green, pages 269–74. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998. . Reprinted 2012. .

*Alexander Alan Steinbach. ''Sabbath Queen: Fifty-four Bible Talks to the Young Based on Each Portion of the Pentateuch'', pages 132–35. New York: Behrman's Jewish Book House, 1936.

*Julius H. Greenstone. ''Numbers: With Commentary: The Holy Scriptures'', pages 311–37. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1939. Reprinted by Literary Licensing, 2011. .

*G. Henton Davies. “Vows.” In ''The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible'', volume 4, pages 792–94. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1962.

*J. Roy Porter. "The Succession of Joshua." In ''Proclamation and Presence: Old Testament Essays in Honour of Gwynne Henton Davies''. Edited by John I. Durham and J. Roy Porter, pages 102–32. London: SCM Press, 1970. .

*Carol L. Meyers. "The Roots of Restriction: Women in Early Israel." '' Biblical Archaeologist'', volume 41 (number 3) (September 1978).

*Philip J. Budd. ''Word Biblical Commentary: Volume 5: Numbers'', pages 320–47. Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1984. .

* Pinchas H. Peli. ''Torah Today: A Renewed Encounter with Scripture'', pages 189–93. Washington, D.C.: B'nai B'rith Books, 1987. .

* Michael Fishbane. ''Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel'', pages 82, 171, 258–60, 304. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985. .

* Jacob Milgrom. ''The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation'', pages 250–77, 488–96. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990. .

* Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal). ''Commentary on the Torah.'' Padua, 1871. In, e.g., Samuel David Luzzatto. ''Torah Commentary''. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1113–20. New York: Lambda Publishers, 2012. .

* Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter. ''Sefat Emet''. Góra Kalwaria (Ger), Poland, before 1906. Excerpted in ''The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet''. Translated and interpreted by Arthur Green, pages 269–74. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998. . Reprinted 2012. .

*Alexander Alan Steinbach. ''Sabbath Queen: Fifty-four Bible Talks to the Young Based on Each Portion of the Pentateuch'', pages 132–35. New York: Behrman's Jewish Book House, 1936.

*Julius H. Greenstone. ''Numbers: With Commentary: The Holy Scriptures'', pages 311–37. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1939. Reprinted by Literary Licensing, 2011. .

*G. Henton Davies. “Vows.” In ''The Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible'', volume 4, pages 792–94. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1962.

*J. Roy Porter. "The Succession of Joshua." In ''Proclamation and Presence: Old Testament Essays in Honour of Gwynne Henton Davies''. Edited by John I. Durham and J. Roy Porter, pages 102–32. London: SCM Press, 1970. .

*Carol L. Meyers. "The Roots of Restriction: Women in Early Israel." '' Biblical Archaeologist'', volume 41 (number 3) (September 1978).

*Philip J. Budd. ''Word Biblical Commentary: Volume 5: Numbers'', pages 320–47. Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1984. .

* Pinchas H. Peli. ''Torah Today: A Renewed Encounter with Scripture'', pages 189–93. Washington, D.C.: B'nai B'rith Books, 1987. .

* Michael Fishbane. ''Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel'', pages 82, 171, 258–60, 304. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985. .

* Jacob Milgrom. ''The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation'', pages 250–77, 488–96. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990. .

*

*Mark S. Smith

Mark Stratton John Matthew Smith (born December 6, 1956) is an American biblical scholar, anthropologist, and professor.

Early life and education

Born in Paris to Donald Eugene Smith and Mary Elizabeth (Betty) Reichert, Smith grew up in Washin ...

. ''The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel'', pages 2, 48. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990. . ( ).

* Lawrence H. Schiffman“The Law of Vows and Oaths (''Num''. 30, 3–16) in the ‘Zadokite Fragments’ and the ‘Temple Scroll.’”

''Revue de Qumrân'', volume 15 (number 1/2) (57/58) (September 1991): pages 199–214. *

Mary Douglas

Dame Mary Douglas, (25 March 1921 – 16 May 2007) was a British anthropologist, known for her writings on human culture and symbolism, whose area of speciality was social anthropology. Douglas was considered a follower of Émile Durkhei ...

. ''In the Wilderness: The Doctrine of Defilement in the Book of Numbers'', pages xix, 60, 86, 100, 103, 106, 108–10, 112, 120–21, 123, 126, 135, 141, 147, 160, 170–71, 183, 185–86, 199, 218, 222, 242. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. Reprinted 2004. .

*Judith S. Antonelli. "A Woman's Vow." In ''In the Image of God: A Feminist Commentary on the Torah'', pages 383–91. Northvale, New Jersey: Jason Aronson, 1995. .

*

*Ellen Frankel Ellen Frankel (born 1951) was the Editor-in-Chief of the Jewish Publication Society (JPS) from 1991 until 2009, and also served as CEO of the JPS for 10 years. She retired in 2009 to pursue her own writing and scholarly projects, serving as JPS's f ...

. ''The Five Books of Miriam: A Woman's Commentary on the Torah'', pages 237–41. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1996. .

*W. Gunther Plaut

Wolf Gunther Plaut, (November 1, 1912 – February 8, 2012) was an American Reform rabbi and writer who was based in Canada. Plaut was the rabbi of Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto for several decades and since 1978 was its senior scholar.

L ...

. ''The Haftarah Commentary'', pages 407–15. New York: UAHC Press, 1996. .

*Sorel Goldberg Loeb and Barbara Binder Kadden. ''Teaching Torah: A Treasury of Insights and Activities'', pages 278–83. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 1997. .

*Susan Freeman. ''Teaching Jewish Virtues: Sacred Sources and Arts Activities'', pages 69–84. Springfield, New Jersey: A.R.E. Publishing, 1999. . ().

*Baruch A. Levine

Baruch Abraham Levine (July 10, 1930 – December 16, 2021) was the Skirball Professor Emeritus of Bible and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at New York University.

Levine was educated at Case Western Reserve University and obtained his PhD at Bran ...

. ''Numbers 21–36'', volume 4A, pages 423–507. New York: Anchor Bible, 2000. .

*Stacy K. Offner. "Women Speak Louder Than Words." In ''The Women's Torah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Torah Portions''. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 315–20. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2000. .

*Dennis T. Olson. “Numbers.” In ''The HarperCollins Bible Commentary''. Edited by James L. Mays

James Luther Mays (July 14, 1921 – October 29, 2015) was an American Old Testament scholar. He was Cyrus McCormick Professor of Hebrew and the Old Testament Emeritus at Union Presbyterian Seminary, Virginia. He served as president of the Society ...

, pages 185–87. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, revised edition, 2000. .

*Lainie Blum Cogan and Judy Weiss. ''Teaching Haftarah: Background, Insights, and Strategies'', pages 364–73. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 2002. .

* Michael Fishbane. ''The JPS Bible Commentary: Haftarot'', pages 255–69. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2002. .

*Robert Alter

Robert Bernard Alter (born 1935) is an American professor of Hebrew and comparative literature at the University of California, Berkeley, where he has taught since 1967. He published his translation of the Hebrew Bible in 2018.

Biography

Rober ...

. ''The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary'', pages 838–51. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004. .

*Moshe J. Bernstein“Women and Children in Legal and Liturgical Texts from Qumran.”

''Dead Sea Discoveries'', volume 11 (number 2) (2004): pages 191–211. *Rachel R. Bovitz. “Haftarat Mattot: Jeremiah 1:1–2:3.” In ''The Women's Haftarah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Haftarah Portions, the 5 Megillot & Special Shabbatot''. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 200–05. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2004. . *Nili S. Fox. "Numbers." In ''The Jewish Study Bible''. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 343–49. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. . *''Professors on the Parashah: Studies on the Weekly Torah Reading'' Edited by Leib Moscovitz, pages 284–89. Jerusalem:

Urim Publications

Urim Publications, an independent publisher of Jewish interest books, is based in Jerusalem, with an outlet in Brooklyn, New York.

Established in 1997 by Tzvi Mauer, Urim publishes approximately fifteen books per year on various topics related to ...

, 2005. .

*W. Gunther Plaut. ''The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition''. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, pages 1099–115. New York: Union for Reform Judaism, 2006. .

*Suzanne A. Brody. "Gag Rule." In ''Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems'', page 101. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007. .

*

*Suzanne A. Brody. "Gag Rule." In ''Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems'', page 101. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007. .

*James L. Kugel

James L. Kugel (Hebrew: Yaakov Kaduri, יעקב כדורי; born August 22, 1945) is Professor Emeritus in the Bible Department at Bar Ilan University in Israel and the Harry M. Starr Professor Emeritus of Classical and Modern Hebrew Literature at ...

. ''How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now'', page 64, 303, 340, 404. New York: Free Press, 2007. .

*Daryl F. Jefferies“Scripture, Wisdom, and Authority in 4QInstruction: Understanding the Use of Numbers 30:8–9 in 4Q416.”

''Hebrew Studies'', volume 49 (2008): pages 87–98. *''The Torah: A Women's Commentary''. Edited by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, pages 989–1012. New York: URJ Press, 2008. . *R. Dennis Cole. "Numbers." In ''Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary''. Edited by

John H. Walton

John H. Walton (born 1952) is an Old Testament scholar and Professor at Wheaton College. He was a professor at Moody Bible Institute for 20 years. He specializes in the Ancient Near Eastern backgrounds of the Old Testament, especially Genesis ...

, volume 1, pages 390–95. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009. .