Martin Luther (Lucas Cranach) 1526 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest,

Martin Luther was born to Hans Luder (or Ludher, later Luther) Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 1. and his wife Margarethe (née Lindemann) on 10 November 1483 in

Martin Luther was born to Hans Luder (or Ludher, later Luther) Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 1. and his wife Margarethe (née Lindemann) on 10 November 1483 in

Luther dedicated himself to the Augustinian order, devoting himself to

Luther dedicated himself to the Augustinian order, devoting himself to

In 1516,

In 1516,  Luther objected to a saying attributed to Tetzel that "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory (also attested as 'into heaven') springs." He insisted that, since

Luther objected to a saying attributed to Tetzel that "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory (also attested as 'into heaven') springs." He insisted that, since

From 1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, and on the books of Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to view the use of terms such as

From 1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, and on the books of Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to view the use of terms such as

Archbishop Albrecht did not reply to Luther's letter containing the ''Ninety-five Theses''. He had the theses checked for heresy and in December 1517 forwarded them to Rome. He needed the revenue from the indulgences to pay off a papal dispensation for his tenure of more than one bishopric. As Luther later notes, "the pope had a finger in the pie as well, because one half was to go to the building of St. Peter's Church in Rome".

Pope Leo X was used to reformers and heretics, and he responded slowly, "with great care as is proper." Over the next three years he deployed a series of papal theologians and envoys against Luther, which served only to harden the reformer's anti-papal theology. First, the Dominican theologian

Archbishop Albrecht did not reply to Luther's letter containing the ''Ninety-five Theses''. He had the theses checked for heresy and in December 1517 forwarded them to Rome. He needed the revenue from the indulgences to pay off a papal dispensation for his tenure of more than one bishopric. As Luther later notes, "the pope had a finger in the pie as well, because one half was to go to the building of St. Peter's Church in Rome".

Pope Leo X was used to reformers and heretics, and he responded slowly, "with great care as is proper." Over the next three years he deployed a series of papal theologians and envoys against Luther, which served only to harden the reformer's anti-papal theology. First, the Dominican theologian  In January 1519, at

In January 1519, at

The enforcement of the ban on the ''Ninety-five Theses'' fell to the secular authorities. On 18 April 1521, Luther appeared as ordered before the

The enforcement of the ban on the ''Ninety-five Theses'' fell to the secular authorities. On 18 April 1521, Luther appeared as ordered before the

theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, author, hymnwriter

A hymnwriter (or hymn writer, hymnist, hymnodist, hymnographer, etc.) is someone who writes the text, music, or both of hymns. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the composition of hymns dates back to before the time of David, who composed many of ...

, professor, and Augustinian friar Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

who gave his name to Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

.

Luther was ordained to the priesthood in 1507. He came to reject several teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

; in particular, he disputed the view on indulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins". The '' Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission before God o ...

s. Luther proposed an academic discussion of the practice and efficacy of indulgences in his ''Ninety-five Theses

The ''Ninety-five Theses'' or ''Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences''-The title comes from the 1517 Basel pamphlet printing. The first printings of the ''Theses'' use an incipit rather than a title which summarizes the content ...

'' of 1517. His refusal to renounce all of his writings at the demand of Pope Leo X in 1520 and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned to t ...

in 1521 resulted in his excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

by the pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and condemnation as an outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so that anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them ...

by the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

.

Luther taught that salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

and, consequently, eternal life are not earned by good deeds but are received only as the free gift of God's grace

Grace may refer to:

Places United States

* Grace, Idaho, a city

* Grace (CTA station), Chicago Transit Authority's Howard Line, Illinois

* Little Goose Creek (Kentucky), location of Grace post office

* Grace, Carroll County, Missouri, an uninco ...

through the believer's faith

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as "belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people often ...

in Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

as redeemer from sin. His theology challenged the authority and office of the pope by teaching that the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

is the only source of divinely revealed

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

knowledge, and opposed sacerdotalism Sacerdotalism (from Latin ''sacerdos'', priest, literally one who presents sacred offerings, ''sacer'', sacred, and ''dare'', to give) is the belief in some Christian churches that priests are meant to be mediators between God and humankind. The und ...

by considering all baptized Christians to be a holy priesthood. Those who identify with these, and all of Luther's wider teachings, are called Lutherans, though Luther insisted on ''Christian'' or ''Evangelical'' (German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

: ''evangelisch'') as the only acceptable names for individuals who professed Christ.

His translation of the Bible into the German vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

(instead of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

) made it more accessible to the laity, an event that had a tremendous impact on both the church and German culture. It fostered the development of a standard version of the German language

German ( ) is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and Official language, official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Ita ...

, added several principles to the art of translation, and influenced the writing of an English translation, the Tyndale Bible

The Tyndale Bible generally refers to the body of Bible translations, biblical translations by William Tyndale into Early Modern English, made . Tyndale's Bible is credited with being the first Bible translation in the English language to work ...

.''Tyndale's New Testament'', trans. from the Greek by William Tyndale in 1534 in a modern-spelling edition and with an introduction by David Daniell. New Haven, CT: Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

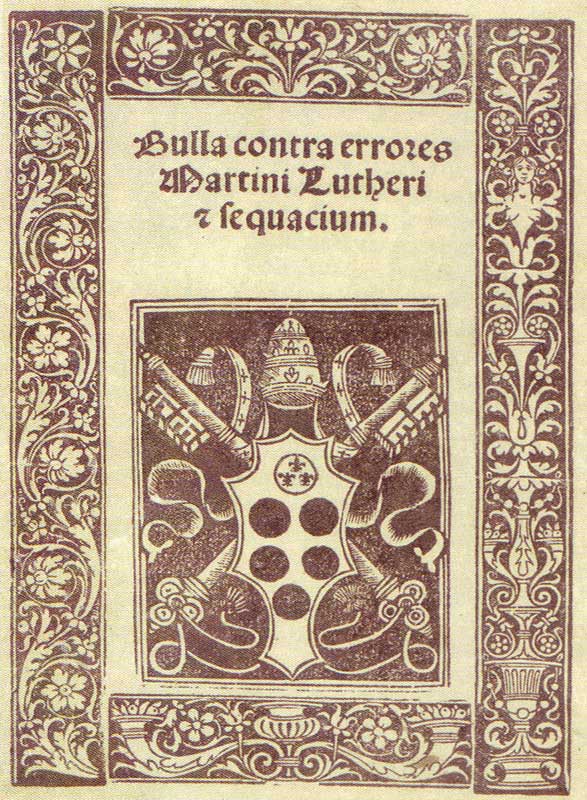

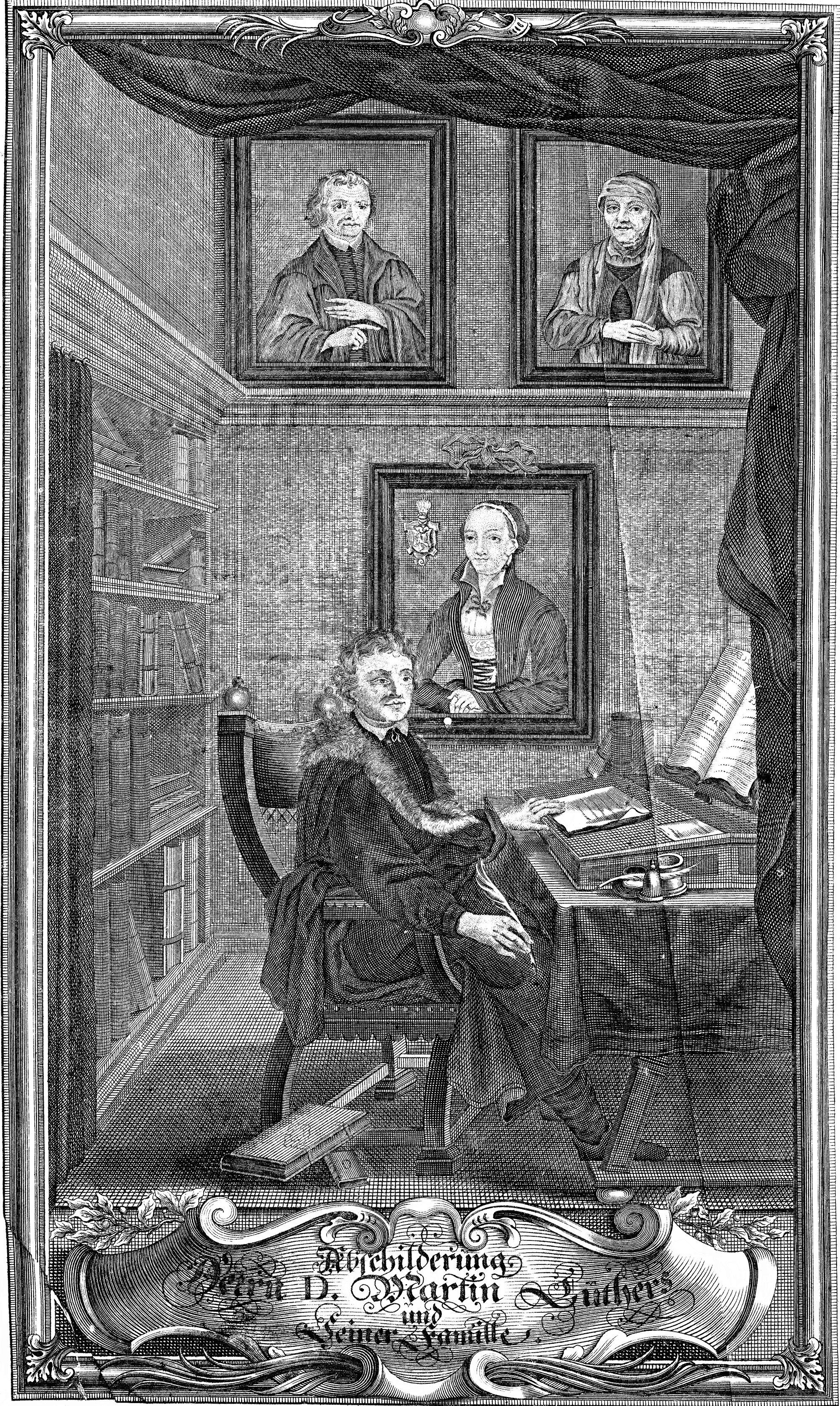

Press, 1989, ix–x. His hymns influenced the development of singing in Protestant churches. Bainton, Roland. ''Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther''. New York: Penguin, 1995, 269. His marriage to Katharina von Bora

Katharina von Bora (; 29 January 1499 – 20 December 1552), after her wedding Katharina Luther, also referred to as "die Lutherin" ("the Lutheress"), was the wife of Martin Luther, German reformer and a seminal figure of the Protestant Reforma ...

, a former nun, set a model for the practice of clerical marriage

Clerical marriage is practice of allowing Christian clergy (those who have already been ordained) to marry. This practice is distinct from allowing married persons to become clergy. Clerical marriage is admitted among Protestants, including both A ...

, allowing Protestant clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

to marry.Bainton, Roland. ''Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther''. New York: Penguin, 1995, p. 223.

In two of his later works, Luther expressed antisemitic views, calling for the expulsion of Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and burning of synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of worshi ...

s. In addition, these works also targeted Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

s, Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from New Latin language, Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re- ...

, and nontrinitarian Christians

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the mainstream Christian doctrine of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essence ...

. Based upon his significant anti-judaistic teachings, the prevailing view among historians is that his rhetoric contributed significantly to the development of antisemitism in Germany

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-Semitism)—prejudice, hatred of, or discrimination against Jews— has experienced a long history of expression since the days of ancient civilizations, with most of it having originated in the Christian and pre ...

and of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

."The assertion that Luther's expressions of anti-Jewish sentiment have been of major and persistent influence in the centuries after the Reformation, and that there exists a continuity between Protestant anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism is the "total or partial opposition to Judaism as a religion—and the total or partial opposition to Jews as adherents of it—by persons who accept a competing system of beliefs and practices and consider certain genuine Judai ...

and modern racially oriented antisemitism, is at present wide-spread in the literature; since the Second World War it has understandably become the prevailing opinion." Johannes Wallmann, "The Reception of Luther's Writings on the Jews from the Reformation to the End of the 19th century", ''Lutheran Quarterly'', n.s. 1 (Spring 1987) 1:72–97. Luther died in 1546 with Pope Leo X's excommunication still in effect.

Early life

Birth and education

Martin Luther was born to Hans Luder (or Ludher, later Luther) Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 1. and his wife Margarethe (née Lindemann) on 10 November 1483 in

Martin Luther was born to Hans Luder (or Ludher, later Luther) Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 1. and his wife Margarethe (née Lindemann) on 10 November 1483 in Eisleben

Eisleben is a town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. It is famous as both the hometown of the influential theologian Martin Luther and the place where he died; hence, its official name is Lutherstadt Eisleben. First mentioned in the late 10th century, E ...

, County of Mansfeld

The House of Mansfeld was a princely German house, which took its name from the town of Mansfeld in the present-day state of Saxony-Anhalt. Mansfelds were archbishops, generals, supporters as well as opponents of Martin Luther, and Habsburg admini ...

, in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

. Luther was baptized

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

the next morning on the feast day of St. Martin of Tours

Martin of Tours ( la, Sanctus Martinus Turonensis; 316/336 – 8 November 397), also known as Martin the Merciful, was the third bishop of Tours. He has become one of the most familiar and recognizable Christian saints in France, heralded as the ...

. In 1484, his family moved to Mansfeld

Mansfeld, sometimes also unofficially Mansfeld-Lutherstadt, is a town in the district of Mansfeld-Südharz, in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany.

Protestant reformator Martin Luther grew up in Mansfeld, and in 1993 the town became one of sixteen places in ...

, where his father was a leaseholder of copper mines and smelters Brecht, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:3–5. and served as one of four citizen representatives on the local council; in 1492 he was elected as a town councilor. The religious scholar Martin Marty

Martin Emil Marty (born on February 5, 1928) is an American Lutheran religious scholar who has written extensively on religion in the United States.

Early life and education

Marty was born on February 5, 1928, in West Point, Nebraska, and raised i ...

describes Luther's mother as a hard-working woman of "trading-class stock and middling means", contrary to Luther's enemies, who labeled her a whore and bath attendant.

He had several brothers and sisters and is known to have been close to one of them, Jacob. Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 3.

Hans Luther was ambitious for himself and his family, and he was determined to see Martin, his eldest son, become a lawyer. He sent Martin to Latin schools in Mansfeld, then Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebur ...

in 1497, where he attended a school operated by a lay group called the Brethren of the Common Life

The Brethren of the Common Life (Latin: Fratres Vitae Communis, FVC) was a Roman Catholic pietist religious community founded in the Netherlands in the 14th century by Gerard Groote, formerly a successful and worldly educator who had had a religio ...

, and Eisenach

Eisenach () is a town in Thuringia, Germany with 42,000 inhabitants, located west of Erfurt, southeast of Kassel and northeast of Frankfurt. It is the main urban centre of western Thuringia and bordering northeastern Hessian regions, situat ...

in 1498. Rupp, Ernst Gordon. "Martin Luther," ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', accessed 2006. The three schools focused on the so-called "trivium

The trivium is the lower division of the seven liberal arts and comprises grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

The trivium is implicit in ''De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii'' ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury") by Martianus Capella, but the ...

": grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Luther later compared his education there to purgatory

Purgatory (, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French) is, according to the belief of some Christian denominations (mostly Catholic), an intermediate state after physical death for expiatory purification. The process of purgatory ...

and hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location in the afterlife in which evil souls are subjected to punitive suffering, most often through torture, as eternal punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hell ...

. Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, pp. 2–3.

In 1501, at age 17, he entered the University of Erfurt

The University of Erfurt (german: Universität Erfurt) is a public university located in Erfurt, the capital city of the German state of Thuringia. It was founded in 1379, and closed in 1816. It was re-established in 1994, three years after Germ ...

, which he later described as a beerhouse and whorehouse. Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 4. He was made to wake at four every morning for what has been described as "a day of rote learning and often wearying spiritual exercises." He received his master's degree in 1505. Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 5.

In accordance with his father's wishes, he enrolled in law but dropped out almost immediately, believing that law represented uncertainty. Luther sought assurances about life and was drawn to theology and philosophy, expressing particular interest in Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, William of Ockham

William of Ockham, OFM (; also Occam, from la, Gulielmus Occamus; 1287 – 10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and Catholic theologian, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small vill ...

, and Gabriel Biel

Gabriel Biel (; 1420 to 1425 – 7 December 1495) was a German scholastic philosopher and member of the Canons Regular of the Congregation of Windesheim, who were the clerical counterpart to the Brethren of the Common Life.

Biel was born in Spey ...

. He was deeply influenced by two tutors, Bartholomaeus Arnoldi Bartholomaeus Arnoldi, OSA (usually called Usingen; german: Bartholomäus Arnoldi von Usingen; 1465 – 9 September 1532) was an Augustinian friar and doctor of divinity who taught Martin Luther and later turned into his earliest and one of his per ...

von Usingen and Jodocus Trutfetter, who taught him to be suspicious of even the greatest thinkers and to test everything himself by experience. Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 6.

Philosophy proved to be unsatisfying, offering assurance about the use of reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

but none about loving God, which to Luther was more important. Reason could not lead men to God, he felt, and he thereafter developed a love-hate relationship with Aristotle over the latter's emphasis on reason. For Luther, reason could be used to question men and institutions, but not God. Human beings could learn about God only through divine revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

, he believed, and Scripture therefore became increasingly important to him.

On 2 July 1505, while Luther was returning to university on horseback after a trip home, a lightning bolt struck near him during a thunderstorm. Later telling his father he was terrified of death and divine judgment, he cried out, "Help! Saint Anna

According to Christian apocryphal and Islamic tradition, Saint Anne was the mother of Mary and the maternal grandmother of Jesus. Mary's mother is not named in the canonical gospels. In writing, Anne's name and that of her husband Joachim come ...

, I will become a monk!"Brecht, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:48. He came to view his cry for help as a vow he could never break. He left university, sold his books, and entered St. Augustine's Monastery in Erfurt

Erfurt () is the capital and largest city in the Central German state of Thuringia. It is located in the wide valley of the Gera river (progression: ), in the southern part of the Thuringian Basin, north of the Thuringian Forest. It sits i ...

on 17 July 1505. One friend blamed the decision on Luther's sadness over the deaths of two friends. Luther himself seemed saddened by the move. Those who attended a farewell supper walked him to the door of the Black Cloister. "This day you see me, and then, not ever again," he said. His father was furious over what he saw as a waste of Luther's education. Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 7.

Monastic life

Luther dedicated himself to the Augustinian order, devoting himself to

Luther dedicated himself to the Augustinian order, devoting himself to fasting

Fasting is the abstention from eating and sometimes drinking. From a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (see " Breakfast"), or to the metabolic state achieved after ...

, long hours in prayer

Prayer is an invocation or act that seeks to activate a rapport with an object of worship through deliberate communication. In the narrow sense, the term refers to an act of supplication or intercession directed towards a deity or a deified a ...

, pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

, and frequent confession

A confession is a statement – made by a person or by a group of persons – acknowledging some personal fact that the person (or the group) would ostensibly prefer to keep hidden. The term presumes that the speaker is providing information th ...

.Bainton, Roland. ''Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther''. New York: Penguin, 1995, 40–42. Luther described this period of his life as one of deep spiritual despair. He said, "I lost touch with Christ the Savior and Comforter, and made of him the jailer and hangman of my poor soul."Kittelson, James. ''Luther The Reformer''. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishing House, 1986, 79.

Johann von Staupitz

Johann von Staupitz, O.S.A. (c. 1460 – 28 December 1524) was a Catholic theologian, university preacher, and Vicar General of the Augustinian friars in Germany, who supervised Martin Luther during a critical period in his spiritual life. Martin ...

, his superior, concluded that Luther needed more work to distract him from excessive introspection and ordered him to pursue an academic career. On 3 April 1507, Jerome Schultz (lat. Hieronymus Scultetus), the Bishop of Brandenburg

The Prince-Bishopric of Brandenburg (german: Hochstift Brandenburg) was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire from the 12th century until it was secularized during the second half of the 16th century. It should not be confused wi ...

, ordained Luther in Erfurt Cathedral

Erfurt Cathedral (german: Erfurter Dom, link=no, officially ''Hohe Domkirche St. Marien zu Erfurt'', English: Cathedral Church of St Mary at Erfurt), also known as St Mary's Cathedral, is the largest and oldest church building in ...

. In 1508, he began teaching theology at the University of Wittenberg

Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg (german: Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), also referred to as MLU, is a public, research-oriented university in the cities of Halle and Wittenberg and the largest and oldest university i ...

.Bainton, Roland. ''Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther''. New York: Penguin, 1995, 44–45. He received a bachelor's degree in biblical studies on 9 March 1508 and another bachelor's degree in the ''Sentences

''The Four Books of Sentences'' (''Libri Quattuor Sententiarum'') is a book of theology written by Peter Lombard in the 12th century. It is a systematic compilation of theology, written around 1150; it derives its name from the ''sententiae'' o ...

'' by Peter Lombard

Peter Lombard (also Peter the Lombard, Pierre Lombard or Petrus Lombardus; 1096, Novara – 21/22 July 1160, Paris), was a scholastic theologian, Bishop of Paris, and author of '' Four Books of Sentences'' which became the standard textbook of ...

in 1509.Brecht, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:93. On 19 October 1512, he was awarded his Doctor of Theology

Doctor of Theology ( la, Doctor Theologiae, abbreviated DTh, ThD, DTheol, or Dr. theol.) is a terminal degree in the academic discipline of theology. The ThD, like the ecclesiastical Doctor of Sacred Theology, is an advanced research degree equiva ...

and, on 21 October 1512, was received into the senate of the theological faculty of the University of Wittenberg,Brecht, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:112–27. having succeeded von Staupitz as chair of theology. He spent the rest of his career in this position at the University of Wittenberg.

He was made provincial vicar

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pref ...

of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

and Thuringia

Thuringia (; german: Thüringen ), officially the Free State of Thuringia ( ), is a state of central Germany, covering , the sixth smallest of the sixteen German states. It has a population of about 2.1 million.

Erfurt is the capital and larg ...

by his religious order in 1515. This meant he was to visit and oversee each of eleven monasteries in his province.

Start of the Reformation

In 1516,

In 1516, Johann Tetzel

Johann Tetzel (c. 1465 – 11 August 1519) was a German Dominican friar and preacher. He was appointed Inquisitor for Poland and Saxony, later becoming the Grand Commissioner for indulgences in Germany. Tetzel was known for granting indulgence ...

, a Dominican friar

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of Cal ...

, was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church to sell indulgences to raise money in order to rebuild St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal en ...

in Rome. Tetzel's experiences as a preacher of indulgences, especially between 1503 and 1510, led to his appointment as general commissioner by Albrecht von Brandenburg, Archbishop of Mainz, who, deeply in debt to pay for a large accumulation of benefices, had to contribute the considerable sum of ten thousand ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wi ...

s toward the rebuilding of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Albrecht obtained permission from Pope Leo X to conduct the sale of a special plenary indulgence (i.e., remission of the temporal punishment of sin), half of the proceeds of which Albrecht was to claim to pay the fees of his benefices.

On 31 October 1517, Luther wrote to his bishop, Albrecht von Brandenburg, protesting against the sale of indulgences. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his "Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences", – The first printings of the ''Theses'' use an incipit

The incipit () of a text is the first few words of the text, employed as an identifying label. In a musical composition, an incipit is an initial sequence of notes, having the same purpose. The word ''incipit'' comes from Latin and means "it beg ...

rather than a title which summarizes the content. Luther usually called them "" (my propositions). which came to be known as the ''Ninety-five Theses

The ''Ninety-five Theses'' or ''Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences''-The title comes from the 1517 Basel pamphlet printing. The first printings of the ''Theses'' use an incipit rather than a title which summarizes the content ...

''. Hans Hillerbrand writes that Luther had no intention of confronting the church but saw his disputation as a scholarly objection to church practices, and the tone of the writing is accordingly "searching, rather than doctrinaire."Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Martin Luther: Indulgences and salvation," ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 2007. Hillerbrand writes that there is nevertheless an undercurrent of challenge in several of the theses, particularly in Thesis 86, which asks: "Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus (; 115 – 53 BC) was a Roman general and statesman who played a key role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He is often called "the richest man in Rome." Wallechinsky, David & Wallace, I ...

, build the basilica of St. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?"

Luther objected to a saying attributed to Tetzel that "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory (also attested as 'into heaven') springs." He insisted that, since

Luther objected to a saying attributed to Tetzel that "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory (also attested as 'into heaven') springs." He insisted that, since forgiveness

Forgiveness, in a psychological sense, is the intentional and voluntary process by which one who may initially feel victimized or wronged, goes through a change in feelings and attitude regarding a given offender, and overcomes the impact of th ...

was God's alone to grant, those who claimed that indulgences absolved buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were in error. Christians, he said, must not slacken in following Christ on account of such false assurances.

According to one account, Luther nailed his ''Ninety-five Theses'' to the door of All Saints' Church

All Saints Church, or All Saints' Church or variations on the name may refer to:

Albania

*All Saints' Church, Himarë

Australia

*All Saints Church, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory

* All Saints Anglican Church, Henley Brook, Western Austr ...

in Wittenberg

Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon language, Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the Ri ...

on 31 October 1517. Scholars Walter Krämer, Götz Trenkler, Gerhard Ritter, and Gerhard Prause contend that the story of the posting on the door, although it has become one of the pillars of history, has little foundation in truth.Krämer, Walter and Trenkler, Götz. "Luther" in ''Lexicon van Hardnekkige Misverstanden''. Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, 1997, 214:216.Ritter, Gerhard. ''Luther'', Frankfurt 1985.Gerhard Prause "Luthers Thesanschlag ist eine Legende,"in ''Niemand hat Kolumbus ausgelacht''. Düsseldorf, 1986.Marshall, Peter ''1517: Martin Luther and the Invention of the Reformation'' (Oxford University Press, 2017) The story is based on comments made by Luther's collaborator Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

, though it is thought that he was not in Wittenberg at the time. According to Roland Bainton

Roland Herbert Bainton (March 30, 1894 – February 13, 1984) was a British-born American Protestant church historian.

Life

Bainton was born in Ilkeston, Derbyshire, England, and came to the United States in 1902. He received an AB degree fr ...

, on the other hand, it is true.

The Latin ''Theses'' were printed in several locations in Germany in 1517. In January 1518 friends of Luther translated the ''Ninety-five Theses'' from Latin into German.Brecht, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:204–05. Within two weeks, copies of the theses had spread throughout Germany. Luther's writings circulated widely, reaching France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

as early as 1519. Students thronged to Wittenberg to hear Luther speak. He published a short commentary on Galatians Galatians may refer to:

* Galatians (people)

* Epistle to the Galatians, a book of the New Testament

* English translation of the Greek ''Galatai'' or Latin ''Galatae'', ''Galli,'' or ''Gallograeci'' to refer to either the Galatians or the Gauls in ...

and his ''Work on the Psalms''. This early part of Luther's career was one of his most creative and productive. Three of his best-known works were published in 1520: ''To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation

''To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation'' (german: An den christlichen Adel deutscher Nation) is the first of three tracts written by Martin Luther in 1520. In this work, he defined for the first time the signature doctrines of the priesth ...

'', ''On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church

''Prelude on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church'' ( la, De captivitate Babylonica ecclesiae, praeludium Martini Lutheri, October 1520) was the second of the three major treatises published by Martin Luther in 1520, coming after the '' Addres ...

'', and ''On the Freedom of a Christian

''On the Freedom of a Christian'' (Latin: ''"De Libertate Christiana"''; German: ''"Von der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen"''), sometimes also called ''"A Treatise on Christian Liberty"'' (November 1520), was the third of Martin Luther’s major ...

''.

Justification by faith alone

From 1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, and on the books of Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to view the use of terms such as

From 1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, and on the books of Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to view the use of terms such as penance

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of Repentance (theology), repentance for Christian views on sin, sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic Church, Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox s ...

and righteousness

Righteousness is the quality or state of being morally correct and justifiable. It can be considered synonymous with "rightness" or being "upright". It can be found in Indian religions and Abrahamic traditions, among other religions, as a theologi ...

by the Catholic Church in new ways. He became convinced that the church was corrupt in its ways and had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity. The most important for Luther was the doctrine of justification—God's act of declaring a sinner righteous—by faith alone through God's grace. He began to teach that salvation or redemption is a gift of God's grace

Grace may refer to:

Places United States

* Grace, Idaho, a city

* Grace (CTA station), Chicago Transit Authority's Howard Line, Illinois

* Little Goose Creek (Kentucky), location of Grace post office

* Grace, Carroll County, Missouri, an uninco ...

, attainable only through faith in Jesus as the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

.Wriedt, Markus. "Luther's Theology," in ''The Cambridge Companion to Luther''. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, 88–94. "This one and firm rock, which we call the doctrine of justification", he writes, "is the chief article of the whole Christian doctrine, which comprehends the understanding of all godliness."

Luther came to understand justification as entirely the work of God. This teaching by Luther was clearly expressed in his 1525 publication ''On the Bondage of the Will

''On the Bondage of the Will'' ( lat, De Servo Arbitrio, literally, "On Un-free Will", or "Concerning Bound Choice"), by Martin Luther, argued that people can only achieve salvation or redemption through God, and could not choose between good and ...

'', which was written in response to ''On Free Will'' by Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' wa ...

(1524). Luther based his position on predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

on St. Paul's epistle to the . Against the teaching of his day that the righteous acts of believers are performed in with God, Luther wrote that Christians receive such righteousness entirely from outside themselves; that righteousness not only comes from Christ but actually the righteousness of Christ, imputed to Christians (rather than infused into them) through faith.

"That is why faith alone makes someone just and fulfills the law," he writes. "Faith is that which brings the Holy Spirit

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...

through the merits of Christ." Faith, for Luther, was a gift from God; the experience of being justified by faith was "as though I had been born again." His entry into Paradise, no less, was a discovery about "the righteousness of God"—a discovery that "the just person" of whom the Bible speaks (as in Romans 1:17) lives by faith. He explains his concept of "justification" in the Smalcald Articles

The Smalcald Articles or Schmalkald Articles (german: Schmalkaldische Artikel) are a summary of Lutheran doctrine, written by Martin Luther in 1537 for a meeting of the Schmalkaldic League in preparation for an intended ecumenical Council of the C ...

:

The first and chief article is this: Jesus Christ, our God and Lord, died for our sins and was raised again for our justification (Romans 3:24–25). He alone is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world (John John is a common English name and surname: * John (given name) * John (surname) John may also refer to: New Testament Works * Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John * First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John * Second ...1:29), and God has laid on Him the iniquity of us all (Isaiah Isaiah ( or ; he, , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "God is Salvation"), also known as Isaias, was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named. Within the text of the Book of Isaiah, Isaiah himself is referred to as "the ...53:6). All have sinned and are justified freely, without their own works and merits, by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, in His blood (Romans 3:23–25). This is necessary to believe. This cannot be otherwise acquired or grasped by any work, law or merit. Therefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone justifies us ... Nothing of this article can be yielded or surrendered, even though heaven and earth and everything else falls (Mark Mark may refer to: Currency * Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina * East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic * Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927 * Fi ...13:31).

Breach with the papacy

Archbishop Albrecht did not reply to Luther's letter containing the ''Ninety-five Theses''. He had the theses checked for heresy and in December 1517 forwarded them to Rome. He needed the revenue from the indulgences to pay off a papal dispensation for his tenure of more than one bishopric. As Luther later notes, "the pope had a finger in the pie as well, because one half was to go to the building of St. Peter's Church in Rome".

Pope Leo X was used to reformers and heretics, and he responded slowly, "with great care as is proper." Over the next three years he deployed a series of papal theologians and envoys against Luther, which served only to harden the reformer's anti-papal theology. First, the Dominican theologian

Archbishop Albrecht did not reply to Luther's letter containing the ''Ninety-five Theses''. He had the theses checked for heresy and in December 1517 forwarded them to Rome. He needed the revenue from the indulgences to pay off a papal dispensation for his tenure of more than one bishopric. As Luther later notes, "the pope had a finger in the pie as well, because one half was to go to the building of St. Peter's Church in Rome".

Pope Leo X was used to reformers and heretics, and he responded slowly, "with great care as is proper." Over the next three years he deployed a series of papal theologians and envoys against Luther, which served only to harden the reformer's anti-papal theology. First, the Dominican theologian Sylvester Mazzolini

Sylvester Mazzolini, in Italian Silvestro Mazzolini da Prierio, in Latin Sylvester Prierias. (1456/1457 – 1527) was a theologian born at Priero, Piedmont; he died at Rome. Prierias perished when the imperial troops forced their way into the ...

drafted a heresy case against Luther, whom Leo then summoned to Rome. The Elector Frederick persuaded the pope to have Luther examined at Augsburg, where the Imperial Diet was held. Over a three-day period in October 1518, Luther defended himself under questioning by papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title ''legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

Cardinal Cajetan

Thomas Cajetan (; 20 February 14699 August 1534), also known as Gaetanus, commonly Tommaso de Vio or Thomas de Vio, was an Italian philosopher, theologian, cardinal (from 1517 until his death) and the Master of the Order of Preachers 1508 to 151 ...

. The pope's right to issue indulgences was at the centre of the dispute between the two men. The hearings degenerated into a shouting match. More than writing his theses, Luther's confrontation with the church cast him as an enemy of the pope: "His Holiness abuses Scripture", retorted Luther. "I deny that he is above Scripture". Cajetan's original instructions had been to arrest Luther if he failed to recant, but the legate desisted from doing so. With help from the Carmelite monk

, image =

, caption = Coat of arms of the Carmelites

, abbreviation = OCarm

, formation = Late 12th century

, founder = Early hermits of Mount Carmel

, founding_location = Mount Car ...

Christoph Langenmantel

Christoph Langenmantel or ''Christoph Langenmantel vom Sparren'' (1488, in Augsburg – 17 May 1538, in Ingolstadt) was a nobleman, Carmelite friar, canon of Freising and a supporter of Martin Luther.

Family

He was from the Langenmantel vom Spa ...

, Luther slipped out of the city at night, unbeknownst to Cajetan.

In January 1519, at

In January 1519, at Altenburg

Altenburg () is a city in Thuringia, Germany, located south of Leipzig, west of Dresden and east of Erfurt. It is the capital of the Altenburger Land district and part of a polycentric old-industrial textile and metal production region betw ...

in Saxony, the papal nuncio Karl von Miltitz

Karl von Miltitz (c. 1490 – 20 November 1529) was a papal ''nuncio'' and a Mainz Cathedral canon.

Biography

He was born in Rabenau near Meißen and Dresden, his family stemming from the lesser Saxon nobility. He studied at Mainz, Trier, Cologn ...

adopted a more conciliatory approach. Luther made certain concessions to the Saxon, who was a relative of the Elector and promised to remain silent if his opponents did. The theologian Johann Eck

Johann Maier von Eck (13 November 1486 – 13 February 1543), often anglicized as John Eck, was a German Catholic theologian, scholastic, prelate, and a pioneer of the counter-reformation who was among Martin Luther's most important inter ...

, however, was determined to expose Luther's doctrine in a public forum. In June and July 1519, he staged a disputation

In the scholastic system of education of the Middle Ages, disputations (in Latin: ''disputationes'', singular: ''disputatio'') offered a formalized method of debate designed to uncover and establish truths in theology and in sciences. Fixed ru ...

with Luther's colleague Andreas Karlstadt

Andreas Rudolph Bodenstein von Karlstadt (148624 December 1541), better known as Andreas Karlstadt or Andreas Carlstadt or Karolostadt, or simply as Andreas Bodenstein, was a German Protestant theologian, University of Wittenberg chancellor, a c ...

at Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

and invited Luther to speak. Luther's boldest assertion in the debate was that does not confer on popes the exclusive right to interpret scripture, and that therefore neither popes nor church councils

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word ''synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin word meani ...

were infallible. For this, Eck branded Luther a new Jan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the inspir ...

, referring to the Czech reformer and heretic burned at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

in 1415. From that moment, he devoted himself to Luther's defeat.

Excommunication

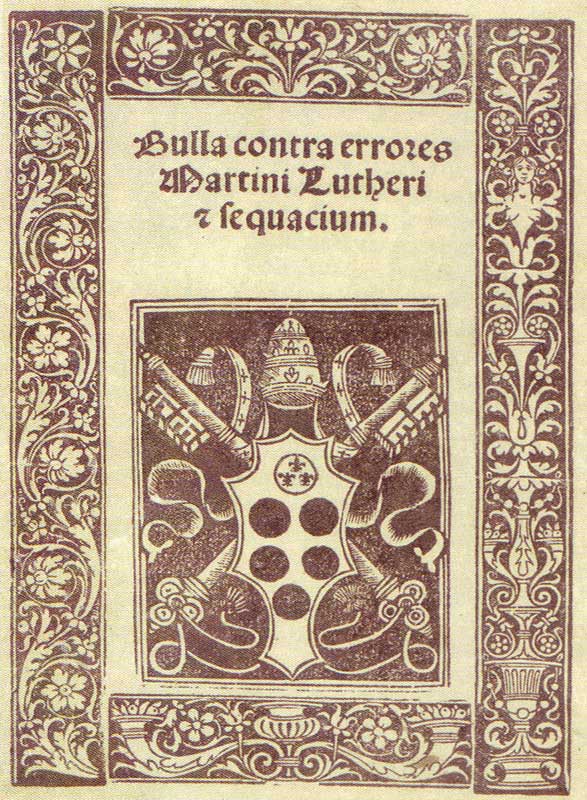

On 15 June 1520, the Pope warned Luther with the papal bull (edict) ''Exsurge Domine

() is a papal bull promulgated on 15 June 1520 by Pope Leo X. It was written in response to the teachings of Martin Luther which opposed the views of the Church. It censured forty-one propositions extracted from Luther's ''Ninety-five Theses'' ...

'' that he risked excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

unless he recanted 41 sentences drawn from his writings, including the ''Ninety-five Theses'', within 60 days. That autumn, Eck proclaimed the bull in Meissen and other towns. Von Miltitz attempted to broker a solution, but Luther, who had sent the pope a copy of ''On the Freedom of a Christian'' in October, publicly set fire to the bull and decretal

Decretals ( la, litterae decretales) are letters of a pope that formulate decisions in ecclesiastical law of the Catholic Church.McGurk. ''Dictionary of Medieval Terms''. p. 10

They are generally given in answer to consultations but are sometimes ...

s at Wittenberg on 10 December 1520,Brecht, Martin. (tr. Wolfgang Katenz) "Luther, Martin," in Hillerbrand, Hans J. (ed.) ''Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, 2:463. an act he defended in ''Why the Pope and his Recent Book are Burned'' and ''Assertions Concerning All Articles''. As a consequence, Luther was excommunicated by Pope on 3 January 1521, in the bull ''Decet Romanum Pontificem

(from Latin: "It Befits the Roman Pontiff"; 1521) is the papal bull which excommunicated the German theologian Martin Luther; its title comes from the first three Latin words of its text. It was issued on January 3, 1521, by Pope Leo X to ef ...

''. And although the Lutheran World Federation

The Lutheran World Federation (LWF; german: Lutherischer Weltbund) is a global communion of national and regional Lutheran denominations headquartered in the Ecumenical Centre in Geneva, Switzerland. The federation was founded in the Swedish ...

, Methodists and the Catholic Church's Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity

The Dicastery for Promoting Christian Unity, previously named the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (PCPCU), is a dicastery whose origins are associated with the Second Vatican Council which met intermittently from 1962 to 1965.

Po ...

agreed (in 1999 and 2006, respectively) on a "common understanding of justification by God's grace through faith in Christ," the Catholic Church has never lifted the 1520 excommunication.

Diet of Worms

The enforcement of the ban on the ''Ninety-five Theses'' fell to the secular authorities. On 18 April 1521, Luther appeared as ordered before the

The enforcement of the ban on the ''Ninety-five Theses'' fell to the secular authorities. On 18 April 1521, Luther appeared as ordered before the Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned to t ...

. This was a general assembly of the estates of the Holy Roman Empire that took place in Worms Worms may refer to:

*Worm, an invertebrate animal with a tube-like body and no limbs

Places

*Worms, Germany, a city

**Worms (electoral district)

*Worms, Nebraska, U.S.

*Worms im Veltlintal, the German name for Bormio, Italy

Arts and entertainme ...

, a town on the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

. It was conducted from 28 January to 25 May 1521, with Emperor Charles V presiding. Prince Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, obtained a safe conduct

Safe conduct, safe passage, or letters of transit, is the situation in time of international conflict or war where one state, a party to such conflict, issues to a person (usually an enemy state's subject) a pass or document to allow the enemy ...

for Luther to and from the meeting.

Johann Eck, speaking on behalf of the empire as assistant of the Archbishop of Trier

The Diocese of Trier, in English historically also known as ''Treves'' (IPA "tɾivz") from French ''Trèves'', is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic church in Germany.Mullett (1986), p. 25

Eck informed Luther that he was acting like a heretic, saying,

Eck informed Luther that he was acting like a heretic, saying,

Luther's disappearance during his return to Wittenberg was planned. had him intercepted on his way home in the forest near Wittenberg by masked horsemen impersonating highway robbers. They escorted Luther to the security of the

Luther's disappearance during his return to Wittenberg was planned. had him intercepted on his way home in the forest near Wittenberg by masked horsemen impersonating highway robbers. They escorted Luther to the security of the

"Let Your Sins Be Strong," a Letter From Luther to Melanchthon

, August 1521, Project Wittenberg, retrieved 1 October 2006. In the summer of 1521, Luther widened his target from individual pieties like indulgences and pilgrimages to doctrines at the heart of Church practice. In ''On the Abrogation of the Private Mass'', he condemned as idolatry the idea that the mass is a sacrifice, asserting instead that it is a gift, to be received with thanksgiving by the whole congregation. His essay ''On Confession, Whether the Pope has the Power to Require It'' rejected compulsory

Luther secretly returned to Wittenberg on 6 March 1522. He wrote to the Elector: "During my absence, Satan has entered my sheepfold, and committed ravages which I cannot repair by writing, but only by my personal presence and living word." For eight days in

Luther secretly returned to Wittenberg on 6 March 1522. He wrote to the Elector: "During my absence, Satan has entered my sheepfold, and committed ravages which I cannot repair by writing, but only by my personal presence and living word." For eight days in  Despite his victory in Wittenberg, Luther was unable to stifle radicalism further afield. Preachers such as

Despite his victory in Wittenberg, Luther was unable to stifle radicalism further afield. Preachers such as

On 13 June 1525, the couple was engaged, with

On 13 June 1525, the couple was engaged, with

By 1526, Luther found himself increasingly occupied in organising a new church. His biblical ideal of congregations choosing their own ministers had proved unworkable. According to Bainton: "Luther's dilemma was that he wanted both a confessional church based on personal faith and experience and a territorial church including all in a given locality. If he were forced to choose, he would take his stand with the masses, and this was the direction in which he moved."

From 1525 to 1529, he established a supervisory church body, laid down a new form of

By 1526, Luther found himself increasingly occupied in organising a new church. His biblical ideal of congregations choosing their own ministers had proved unworkable. According to Bainton: "Luther's dilemma was that he wanted both a confessional church based on personal faith and experience and a territorial church including all in a given locality. If he were forced to choose, he would take his stand with the masses, and this was the direction in which he moved."

From 1525 to 1529, he established a supervisory church body, laid down a new form of  In response to demands for a German

In response to demands for a German

Luther devised the catechism as a method of imparting the basics of Christianity to the congregations. In 1529, he wrote the ''Large Catechism'', a manual for pastors and teachers, as well as a synopsis, the ''Small Catechism'', to be memorised by the people. The catechisms provided easy-to-understand instructional and devotional material on the

Luther devised the catechism as a method of imparting the basics of Christianity to the congregations. In 1529, he wrote the ''Large Catechism'', a manual for pastors and teachers, as well as a synopsis, the ''Small Catechism'', to be memorised by the people. The catechisms provided easy-to-understand instructional and devotional material on the

Luther had published his German translation of the New Testament in 1522, and he and his collaborators completed the translation of the Old Testament in 1534, when the whole Bible was published. He continued to work on refining the translation until the end of his life. Others had previously translated the Bible into German, but Luther tailored his translation to his own doctrine.

Two of the earlier translations were the Mentelin Bible (1456) and the Koberger Bible (1484). There were as many as fourteen in High German, four in Low German, four in Dutch, and various other translations in other languages before the Bible of Luther.

Luther's translation used the variant of German spoken at the Saxon chancellery, intelligible to both northern and southern Germans. He intended his vigorous, direct language to make the Bible accessible to everyday Germans, "for we are removing impediments and difficulties so that other people may read it without hindrance." Published at a time of rising demand for German-language publications, Luther's version quickly became a popular and influential Bible translation. As such, it contributed a distinct flavor to the German language and literature. Furnished with notes and prefaces by Luther, and with woodcuts by

Luther had published his German translation of the New Testament in 1522, and he and his collaborators completed the translation of the Old Testament in 1534, when the whole Bible was published. He continued to work on refining the translation until the end of his life. Others had previously translated the Bible into German, but Luther tailored his translation to his own doctrine.

Two of the earlier translations were the Mentelin Bible (1456) and the Koberger Bible (1484). There were as many as fourteen in High German, four in Low German, four in Dutch, and various other translations in other languages before the Bible of Luther.

Luther's translation used the variant of German spoken at the Saxon chancellery, intelligible to both northern and southern Germans. He intended his vigorous, direct language to make the Bible accessible to everyday Germans, "for we are removing impediments and difficulties so that other people may read it without hindrance." Published at a time of rising demand for German-language publications, Luther's version quickly became a popular and influential Bible translation. As such, it contributed a distinct flavor to the German language and literature. Furnished with notes and prefaces by Luther, and with woodcuts by

Luther was a prolific

Luther was a prolific

In contrast to the views of

In contrast to the views of

In October 1529,

In October 1529,

At the time of the Marburg Colloquy,

At the time of the Marburg Colloquy,

Early in 1537,

Early in 1537,

Luther wrote negatively about the Jews throughout his career.Michael, Robert. ''Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust''. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, 109; Mullett, 242. Though Luther rarely encountered Jews during his life, his attitudes reflected a theological and cultural tradition which saw Jews as a rejected people guilty of the murder of Christ, and he lived in a locality which had expelled Jews some ninety years earlier. He considered the Jews blasphemers and liars because they rejected the divinity of Jesus. In 1523, Luther advised kindness toward the Jews in ''That Jesus Christ was Born a Jew'' and also aimed to convert them to Christianity. When his efforts at conversion failed, he grew increasingly bitter toward them.

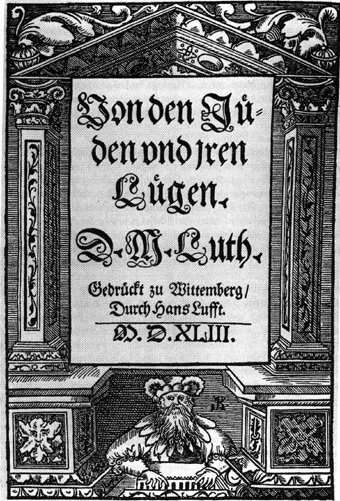

Luther's major works on the Jews were his 60,000-word treatise ''Von den Juden und Ihren Lügen'' (''

Luther wrote negatively about the Jews throughout his career.Michael, Robert. ''Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust''. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, 109; Mullett, 242. Though Luther rarely encountered Jews during his life, his attitudes reflected a theological and cultural tradition which saw Jews as a rejected people guilty of the murder of Christ, and he lived in a locality which had expelled Jews some ninety years earlier. He considered the Jews blasphemers and liars because they rejected the divinity of Jesus. In 1523, Luther advised kindness toward the Jews in ''That Jesus Christ was Born a Jew'' and also aimed to convert them to Christianity. When his efforts at conversion failed, he grew increasingly bitter toward them.

Luther's major works on the Jews were his 60,000-word treatise ''Von den Juden und Ihren Lügen'' (''

Luther was the most widely read author of his generation, and within Germany he acquired the status of a prophet. According to the prevailing opinion among historians,"The assertion that Luther's expressions of anti-Jewish sentiment have been of major and persistent influence in the centuries after the Reformation, and that there exists a continuity between Protestant

Luther was the most widely read author of his generation, and within Germany he acquired the status of a prophet. According to the prevailing opinion among historians,"The assertion that Luther's expressions of anti-Jewish sentiment have been of major and persistent influence in the centuries after the Reformation, and that there exists a continuity between Protestant

Luther had been suffering from ill health for years, including

Luther had been suffering from ill health for years, including

File:Luthers Sterbehaus Eisleben.jpg, Martin Luther's Death House, considered the site of Luther's death since 1726. However the building where Luther actually died (at Markt 56, now the site of Hotel Graf von Mansfeld) was torn down in 1570.

File:Luther death-hand mask.jpg, Casts of Luther's face and hands at his death, in the Market Church in Halle

File:Schlosskirche (Wittenberg).jpg, '' Schlosskirche'' in Wittenberg, where Luther posted his ''Ninety-five Theses'', is also his gravesite.

File:Luthertombstoneunderaltar.jpg, Luther's tombstone beneath the pulpit in the Castle Church in Wittenberg

File:Luthergrab-WB.jpg, Close-up of the grave with inscription in Latin

Luther made effective use of

Luther made effective use of  Luther is honoured on 18 February with a commemoration in the Lutheran Calendar of Saints and in the Episcopal (United States) Calendar of Saints. In the

Luther is honoured on 18 February with a commemoration in the Lutheran Calendar of Saints and in the Episcopal (United States) Calendar of Saints. In the  Various sites both inside and outside Germany (supposedly) visited by Martin Luther throughout his lifetime commemorate it with local memorials.

Various sites both inside and outside Germany (supposedly) visited by Martin Luther throughout his lifetime commemorate it with local memorials.

File:Strümpfelbach im Remstal - Kirche - Lutherbild.jpg, Luther with a swan (painting in the church at Strümpfelbach im Remstal, Weinstadt, Germany, by J. A. List)

File:WLM - andrevanb - amsterdam, ronde lutherse kerk (1).jpg, Swan weather vane, Round Lutheran Church, Amsterdam

File:Halberstadt St Martini Altar.jpg, Altar in St Martin's Church,

Luther is often depicted with a swan as his The Lutheran Identity of Josquin's ''Missa Pange Lingua'' (reference note 94)

Early Music History, vol. 36, October 2017, pp. 193–249; CUP; retrieved 6 July 2020

* The Erlangen Edition (''Erlangener Ausgabe'': "EA"), comprising the ''Exegetica opera latina'' – Latin exegetical works of Luther.

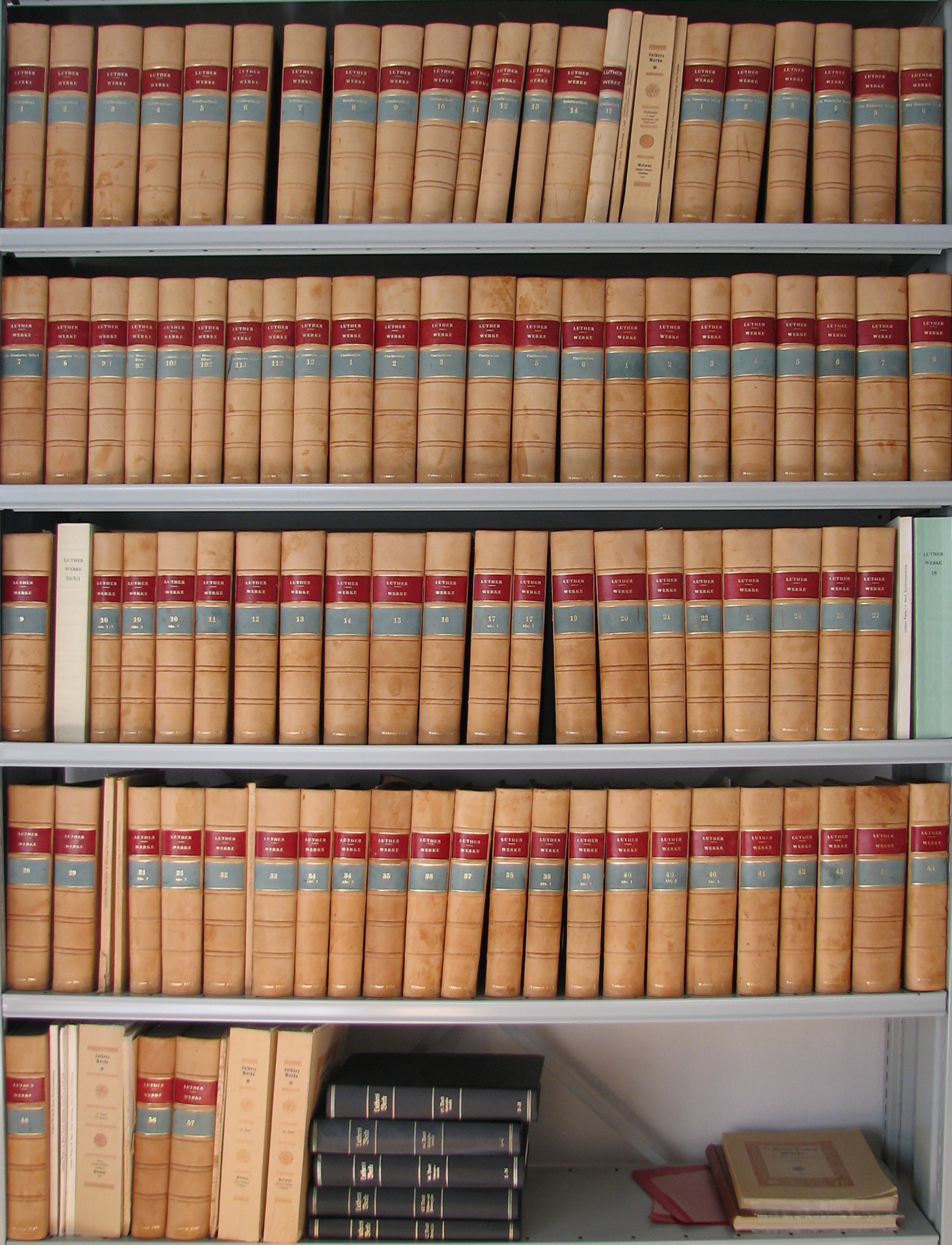

* The Weimar Edition (Weimarer Ausgabe) is the exhaustive, standard German edition of Luther's Latin and German works, indicated by the abbreviation "WA". This is continued into "WA Br" ''Weimarer Ausgabe, Briefwechsel'' (correspondence), "WA Tr" ''Weimarer Ausgabe, Tischreden'' (tabletalk) and "WA DB" ''Weimarer Ausgabe, Deutsche Bibel'' (German Bible).

* The American Edition (''Luther's Works'') is the most extensive English translation of Luther's writings, indicated either by the abbreviation "LW" or "AE". The first 55 volumes were published 1955–1986, and a twenty volume extension (vols. 56–75) is planned of which volumes 58, 60, and 68 have appeared thus far.

* The Erlangen Edition (''Erlangener Ausgabe'': "EA"), comprising the ''Exegetica opera latina'' – Latin exegetical works of Luther.

* The Weimar Edition (Weimarer Ausgabe) is the exhaustive, standard German edition of Luther's Latin and German works, indicated by the abbreviation "WA". This is continued into "WA Br" ''Weimarer Ausgabe, Briefwechsel'' (correspondence), "WA Tr" ''Weimarer Ausgabe, Tischreden'' (tabletalk) and "WA DB" ''Weimarer Ausgabe, Deutsche Bibel'' (German Bible).

* The American Edition (''Luther's Works'') is the most extensive English translation of Luther's writings, indicated either by the abbreviation "LW" or "AE". The first 55 volumes were published 1955–1986, and a twenty volume extension (vols. 56–75) is planned of which volumes 58, 60, and 68 have appeared thus far.

online

* Brecht, Martin. ''Martin Luther: His Road to Reformation 1483–1521'' (vol 1, 1985); ''Martin Luther 1521–1532: Shaping and Defining the Reformation'' (vol 2, 1994); ''Martin Luther The Preservation of the Church Vol 3 1532–1546'' (1999), a standard scholarly biograph

excerpts

* Erikson, Erik H. (1958). ''Young Man Luther: A Study in Psychoanalysis and History''. New York: W.W. Norton. * * Fife, Robert Herndon. (1928). ''Young Luther: The Intellectual and Religious Development of Martin Luther to 1518.'' New York: Macmillan. *Fife, Robert Herndon. (1957). ''The Revolt of Martin Luther.'' New York NY: Columbia University Press. * Friedenthal, Richard (1970). ''Luther, His Life and Times''. Trans. from the German by John Nowell. First American ed. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. viii, 566 p. ''N.B''.: Trans. of the author's ''Luther, sein Leben und seine Zeit''. * * * Kolb, Robert; Dingel, Irene; Batka, Ľubomír (eds.): ''The Oxford Handbook of Martin Luther's Theology''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. . * Luther, M. ''The Bondage of the Will.'' Eds.

''Luther's Use of the Pre-Lutheran Versions of the Bible: Article 1''

George Wahr, The Ann Arbor Press, Ann Arbor, Mich. Reprint 2012:

Maarten Luther Werke

Digitized 1543 edition of ''Von den Juden und ihren Luegen''

by Martin Luther at the

Website about Martin Luther

Commentarius in psalmos Davidis

Manuscript of Luther's first lecture as Professor of Theology at the University of Wittenberg, digital version at the Saxon State and University Library, Dresden (SLUB) * * Martin Luther Collection: Early works attributed to Martin Luther, (285 titles). From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

Robin Leaver: Luther's Liturgical Music

Chronological catalog of Luther's life events, letters, and works with citations

(LettersLuther4.doc: 478 pages, 5.45 MB) {{DEFAULTSORT:Luther, Martin 1483 births 1546 deaths 16th-century apocalypticists 16th-century Christian mystics 16th-century German Protestant theologians 16th-century German male writers 16th-century Latin-language writers 16th-century people of the Holy Roman Empire Anglican saints Antisemitism in Germany Augustinian friars Burials at All Saints' Church, Wittenberg Christian Hebraists Converts to Lutheranism from Roman Catholicism Critics of Judaism Christian critics of Islam Critics of the Catholic Church Founders of religions 16th-century German Lutheran clergy German Lutheran hymnwriters German Lutheran theologians German male non-fiction writers German Christian mystics 16th-century German translators Laicized Roman Catholic priests Latin–German translators Lutheran sermon writers Lutheran writers

Martin, there is no one of the heresies which have torn the bosom of the church, which has not derived its origin from the various interpretation of the Scripture. The Bible itself is the arsenal whence each innovator has drawn his deceptive arguments. It was with Biblical texts thatLuther refused to recant his writings. He is sometimes also quoted as saying: "Here I stand. I can do no other". Recent scholars consider the evidence for these words to be unreliable since they were inserted before "May God help me" only in later versions of the speech and not recorded in witness accounts of the proceedings. However, Mullett suggests that given his nature, "we are free to believe that Luther would tend to select the more dramatic form of words." Over the next five days, private conferences were held to determine Luther's fate. The emperor presented the final draft of thePelagius Pelagius (; c. 354–418) was a British theologian known for promoting a system of doctrines (termed Pelagianism by his opponents) which emphasized human choice in salvation and denied original sin. Pelagius and his followers abhorred the moral s ...andArius Arius (; grc-koi, Ἄρειος, ; 250 or 256 – 336) was a Cyrenaic presbyter, ascetic, and priest best known for the doctrine of Arianism. His teachings about the nature of the Godhead in Christianity, which emphasized God the Father's un ...maintained their doctrines. Arius, for instance, found the negation of the eternity of the Word—an eternity which you admit, in this verse of the New Testament—''Joseph knew not his wife till she had brought forth her first-born son''; and he said, in the same way that you say, that this passage enchained him. When the fathers of theCouncil of Constance The Council of Constance was a 15th-century ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance in present-day Germany. The council ended the Western Schism by deposing or accepting the res ...condemned this proposition of Jan Hus—''The church of Jesus Christ is only the community of the elect'', they condemned an error; for the church, like a good mother, embraces within her arms all who bear the name of Christian, all who are called to enjoy the celestial beatitude.

Edict of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned to t ...

on 25 May 1521, declaring Luther an outlaw

An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so that anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them ...

, banning his literature, and requiring his arrest: "We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic." It also made it a crime for anyone in Germany to give Luther food or shelter. It permitted anyone to kill Luther without legal consequence.

At Wartburg Castle

Luther's disappearance during his return to Wittenberg was planned. had him intercepted on his way home in the forest near Wittenberg by masked horsemen impersonating highway robbers. They escorted Luther to the security of the

Luther's disappearance during his return to Wittenberg was planned. had him intercepted on his way home in the forest near Wittenberg by masked horsemen impersonating highway robbers. They escorted Luther to the security of the Wartburg Castle

The Wartburg () is a castle originally built in the Middle Ages. It is situated on a precipice of to the southwest of and overlooking the town of Eisenach, in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It was the home of St. Elisabeth of Hungary, the p ...

at Eisenach

Eisenach () is a town in Thuringia, Germany with 42,000 inhabitants, located west of Erfurt, southeast of Kassel and northeast of Frankfurt. It is the main urban centre of western Thuringia and bordering northeastern Hessian regions, situat ...

. During his stay at Wartburg, which he referred to as "my Patmos

Patmos ( el, Πάτμος, ) is a Greek island in the Aegean Sea. It is famous as the location where John of Patmos received the visions found in the Book of Revelation of the New Testament, and where the book was written.

One of the northernmos ...

", Luther translated the New Testament