Marsh Fever on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of malaria extendes from its prehistoric origin as a

The first evidence of malaria parasites was found in

The first evidence of malaria parasites was found in

French chemist

French chemist

The establishment of the scientific method from about the mid-19th century on demanded testable hypotheses and verifiable phenomena for causation and transmission. Anecdotal reports, and the discovery in 1881 that mosquitoes were the vector of yellow fever, eventually led to the investigation of mosquitoes in connection with malaria.

An early effort at malaria prevention occurred in 1896 in Massachusetts. An

The establishment of the scientific method from about the mid-19th century on demanded testable hypotheses and verifiable phenomena for causation and transmission. Anecdotal reports, and the discovery in 1881 that mosquitoes were the vector of yellow fever, eventually led to the investigation of mosquitoes in connection with malaria.

An early effort at malaria prevention occurred in 1896 in Massachusetts. An

Hans Andersag, Johann "Hans" Andersag and colleagues synthesized and tested some 12,000 compounds, eventually producing Resochin as a substitute for quinine in the 1930s. It is chemically related to quinine through the possession of a quinoline nucleus and the dialkylaminoalkylamino side chain. Resochin (7-chloro-4- 4- (diethylamino) – 1 – methylbutyl amino quinoline) and a similar compound Sontochin (3-methyl Resochin) were synthesized in 1934. In March 1946, the drug was officially named Chloroquine. Chloroquine is an inhibitor of hemozoin production through biocrystallization. Quinine and chloroquine affect malarial parasites only at life stages when the parasites are forming hematin-pigment (hemozoin) as a byproduct of hemoglobin degradation.

Chloroquine-resistant forms of ''P. falciparum'' emerged only 19 years later. The first resistant strains were detected around the Cambodia‐Thailand border and in Colombia, in the 1950s. In 1989, chloroquine resistance in ''P. vivax'' was reported in Papua New Guinea. These resistant strains spread rapidly, producing a large mortality increase, particularly in Africa during the 1990s.

Hans Andersag, Johann "Hans" Andersag and colleagues synthesized and tested some 12,000 compounds, eventually producing Resochin as a substitute for quinine in the 1930s. It is chemically related to quinine through the possession of a quinoline nucleus and the dialkylaminoalkylamino side chain. Resochin (7-chloro-4- 4- (diethylamino) – 1 – methylbutyl amino quinoline) and a similar compound Sontochin (3-methyl Resochin) were synthesized in 1934. In March 1946, the drug was officially named Chloroquine. Chloroquine is an inhibitor of hemozoin production through biocrystallization. Quinine and chloroquine affect malarial parasites only at life stages when the parasites are forming hematin-pigment (hemozoin) as a byproduct of hemoglobin degradation.

Chloroquine-resistant forms of ''P. falciparum'' emerged only 19 years later. The first resistant strains were detected around the Cambodia‐Thailand border and in Colombia, in the 1950s. In 1989, chloroquine resistance in ''P. vivax'' was reported in Papua New Guinea. These resistant strains spread rapidly, producing a large mortality increase, particularly in Africa during the 1990s.

Artemisinin is a sesquiterpene lactone containing a peroxide group, which is believed to be essential for its anti-malarial activity. Its derivatives, artesunate and artemether, have been used in clinics since 1987 for the treatment of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive malaria, especially cerebral malaria. These drugs are characterized by fast action, high efficacy, and good tolerance. They kill the asexual forms of ''Plasmodium berghei, P. berghei'' and ''P. cynomolgi'' and have transmission-blocking activity. In 1985, Zhou Yiqing and his team combined artemether and lumefantrine into a single tablet, which was registered as a medicine in China in 1992. Later, it became known as Artemether/lumefantrine, "Coartem". Artemisinin combination treatments (ACTs) are now widely used to treat uncomplicated ''falciparum'' malaria, but access to ACTs is still limited in most malaria-endemic countries, and only a minority of the patients who need artemisinin-based combination treatments receive them.

In 2008, White predicted that improved agricultural practices, selection of high-yielding hybrids, Microorganism, microbial production, and the development of synthetic peroxides would lower prices.

Artemisinin is a sesquiterpene lactone containing a peroxide group, which is believed to be essential for its anti-malarial activity. Its derivatives, artesunate and artemether, have been used in clinics since 1987 for the treatment of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive malaria, especially cerebral malaria. These drugs are characterized by fast action, high efficacy, and good tolerance. They kill the asexual forms of ''Plasmodium berghei, P. berghei'' and ''P. cynomolgi'' and have transmission-blocking activity. In 1985, Zhou Yiqing and his team combined artemether and lumefantrine into a single tablet, which was registered as a medicine in China in 1992. Later, it became known as Artemether/lumefantrine, "Coartem". Artemisinin combination treatments (ACTs) are now widely used to treat uncomplicated ''falciparum'' malaria, but access to ACTs is still limited in most malaria-endemic countries, and only a minority of the patients who need artemisinin-based combination treatments receive them.

In 2008, White predicted that improved agricultural practices, selection of high-yielding hybrids, Microorganism, microbial production, and the development of synthetic peroxides would lower prices.

excerpt and text search

* [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1948/muller-lecture.pdf Paul H Müller Nobel Lecture 1948: Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane and newer insecticides]

Ronald Ross Nobel Lecture

* [http://www.im.microbios.org/0901/0901069.pdf Grassi versus Ross: Who solved the riddle of malaria?]

Malaria and the Fall of Rome

Centers for Disease Control: History of Malaria

{{DEFAULTSORT:History of Malaria Malaria History of medicine, Malaria

zoonotic

A zoonosis (; plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a bacterium, virus, parasite or prion) that has jumped from a non-human (usually a vertebrate) to a human. ...

disease in the primates of Africa through to the 21st century. A widespread and potentially lethal human infectious disease, at its peak malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

infested every continent except Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

. Its prevention and treatment have been targeted in science and medicine for hundreds of years. Since the discovery of the ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a ver ...

'' parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

s which cause it, research attention has focused on their biology as well as that of the mosquitoe

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning "gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "lit ...

s which transmit the parasites.

References to its unique, periodic fevers are found throughout recorded history, beginning in the first millennium BC in Greece and China.

For thousands of years, traditional herbal remedies

Herbal medicine (also herbalism) is the study of pharmacognosy and the use of medicinal plants, which are a basis of traditional medicine. With worldwide research into pharmacology, some herbal medicines have been translated into modern remedies ...

have been used to treat malaria. The first effective treatment for malaria came from the bark of the cinchona tree, which contains quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal le ...

. After the link to mosquitos and their parasites was identified in the early twentieth century, mosquito control measures such as widespread use of the insecticide DDT

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT, is a colorless, tasteless, and almost odorless crystalline chemical compound, an organochloride. Originally developed as an insecticide, it became infamous for its environmental impacts. ...

, swamp drainage, covering or oiling the surface of open water sources, indoor residual spraying, and use of insecticide treated nets was initiated. Prophylactic quinine was prescribed in malaria endemic areas, and new therapeutic drugs, including chloroquine

Chloroquine is a medication primarily used to prevent and treat malaria in areas where malaria remains sensitive to its effects. Certain types of malaria, resistant strains, and complicated cases typically require different or additional medi ...

and artemisinin

Artemisinin () and its semisynthetic derivatives are a group of drugs used in the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum''. It was discovered in 1972 by Tu Youyou, who shared the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her ...

s, were used to resist the scourge. Today, artemisinin is present in every remedy applied in the treatment of malaria. After introducing artemisinin as a cure administered together with other remedies, malaria mortality in Africa decreased by half, though it later partially rebounded.

Malaria researchers have won multiple Nobel Prizes for their achievements, although the disease continues to afflict some 200 million patients each year, killing more than 600,000.

Malaria was the most important health hazard encountered by U.S. troops in the South Pacific during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, where about 500,000 men were infected. According to Joseph Patrick Byrne, "Sixty thousand American soldiers died of malaria during the African and South Pacific campaigns."

At the close of the 20th century, malaria remained endemic in more than 100 countries throughout the tropical and subtropical zones, including large areas of Central and South America, Hispaniola ( Haiti and the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

), Africa, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and Oceania. Resistance of ''Plasmodium'' to anti-malaria drugs, as well as resistance of mosquitos to insecticides and the discovery of zoonotic

A zoonosis (; plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a bacterium, virus, parasite or prion) that has jumped from a non-human (usually a vertebrate) to a human. ...

species of the parasite have complicated control measures.

Origin and prehistoric period

The first evidence of malaria parasites was found in

The first evidence of malaria parasites was found in mosquito

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning " gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "li ...

es preserved in amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In ...

from the Palaeogene period that are approximately 30 million years old. Malaria protozoa are diversified into primate, rodent, bird, and reptile host lineages. The DNA of '' Plasmodium falciparum'' shows the same pattern of diversity as its human hosts, with greater diversity in Africa than in the rest of the world, showing that modern humans had had the disease before they left Africa. Humans may have originally caught ''P. falciparum'' from gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or fi ...

s. '' P. vivax'', another malarial ''Plasmodium'' species among the six that infect humans, also likely originated in African gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or fi ...

s and chimpanzees

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative th ...

. Another malarial species recently discovered to be transmissible to humans, '' P. knowlesi'', originated in Asian macaque monkey

The macaques () constitute a genus (''Macaca'') of gregarious Old World monkeys of the subfamily Cercopithecinae. The 23 species of macaques inhabit ranges throughout Asia, North Africa, and (in one instance) Gibraltar. Macaques are principall ...

s. While '' P. malariae'' is highly host specific to humans, there is some evidence that low level non-symptomatic infection persists among wild chimpanzees.

About 10,000 years ago, malaria started having a major impact on human survival, coinciding with the start of agriculture in the Neolithic revolution. Consequences included natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

for sickle-cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders typically inherited from a person's parents. The most common type is known as sickle cell anaemia. It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red blo ...

, thalassaemias, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PDD), which is the most common enzyme deficiency worldwide, is an inborn error of metabolism that predisposes to red blood cell breakdown. Most of the time, those who are affected have no symptoms. ...

, Southeast Asian ovalocytosis

Southeast Asian ovalocytosis is a blood disorder that is similar to, but distinct from hereditary elliptocytosis. It is common in some communities in Malaysia and Papua New Guinea, as it confers some resistance to cerebral Falciparum Malaria.

Pat ...

, elliptocytosis

Hereditary elliptocytosis, also known as ovalocytosis, is an inherited blood disorder in which an abnormally large number of the person's red blood cells are elliptical rather than the typical biconcave disc shape. Such morphologically distinctive ...

and loss of the Gerbich antigen (glycophorin C

Glycophorin C (GYPC; CD236/CD236R; glycoprotein beta; glycoconnectin; PAS-2) plays a functionally important role in maintaining erythrocyte shape and regulating membrane material properties, possibly through its interaction with protein 4.1. Moreo ...

) and the Duffy antigen

Duffy antigen/chemokine receptor (DARC), also known as Fy glycoprotein (FY) or CD234 (Cluster of Differentiation 234), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''ACKR1'' gene.

The Duffy antigen is located on the surface of red blood cells, ...

on the erythrocytes

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

, because such blood disorders

Hematologic diseases are disorders which primarily affect the blood & blood-forming organs. Hematologic diseases include rare genetic disorders, anemia, HIV, sickle cell disease & complications from chemotherapy or transfusions.

Myeloid

* Hemog ...

confer a selective advantage against malaria infection (balancing selection Balancing selection refers to a number of selective processes by which multiple alleles (different versions of a gene) are actively maintained in the gene pool of a population at frequencies larger than expected from genetic drift alone. Balanci ...

). The three major types of inherited genetic resistance (sickle-cell disease, thalassaemias, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency) were present in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

world by the time of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

, about 2000 years ago.

Molecular methods have confirmed the high prevalence of '' P. falciparum'' malaria in ancient Egypt. The Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

historian Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

wrote that the builders of the Egyptian pyramids

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilat ...

(–1700 BCE) were given large amounts of garlic, probably to protect them against malaria. The Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the ...

Sneferu

Sneferu ( snfr-wj "He has perfected me", from ''Ḥr-nb-mꜣꜥt-snfr-wj'' "Horus, Lord of Maat, has perfected me", also read Snefru or Snofru), well known under his Hellenized name Soris ( grc-koi, Σῶρις by Manetho), was the founding phar ...

, the founder of the Fourth dynasty of Egypt

The Fourth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty IV) is characterized as a "golden age" of the Old Kingdom of Egypt. Dynasty IV lasted from to 2494 BC. It was a time of peace and prosperity as well as one during which trade with other ...

, who reigned from around 2613–2589 BCE, used bed-nets

A mosquito net is a type of meshed curtain that is circumferentially draped over a bed or a sleeping area, to offer the sleeper barrier protection against bites and stings from mosquitos, flies, and other pest insects, and thus against the di ...

as protection against mosquitoes. Cleopatra VII

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.She was also a ...

, the last Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, similarly slept under a mosquito net. However, whether the mosquito nets were used for the purpose of malaria prevention, or for more mundane purpose of avoiding the discomfort of mosquito bites, is unknown. The presence of malaria in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

from circa 800 BCE onwards has been confirmed using DNA-based methods.

Classical period

Malaria became widely recognized inancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of Classical Antiquity, classical antiquity ( AD 600), th ...

by the 4th century BC and is implicated in the decline of many city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

populations. The term ''μίασμα'' (Greek for miasma): "stain, pollution was coined by Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

of Kos

Kos or Cos (; el, Κως ) is a Greek island, part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese by area, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 36,986 (2021 census), ...

who used it to describe dangerous fumes from the ground that are transported by winds and can cause serious illnesses. Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

(460–370 BC), the "father of medicine", related the presence of intermittent fevers

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a temperature above the normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature set point. There is not a single agreed-upon upper limit for normal temperature with sources using val ...

with climatic

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in an area, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorological ...

and environmental

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale f ...

conditions and classified the fever according to periodicity: Gk.:''tritaios pyretos'' / L.:''febris tertiana'' (fever every third day), and Gk.:''tetartaios pyretos'' / L.:''febris quartana'' (fever every fourth day).

The Chinese ''Huangdi Neijing

''Huangdi Neijing'' (), literally the ''Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor'' or ''Esoteric Scripture of the Yellow Emperor'', is an ancient Chinese medical text or group of texts that has been treated as a fundamental doctrinal source for Chines ...

'' (The Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor) dating from ~300 BC – 200 AD apparently refers to repeated paroxysmal fevers associated with enlarged spleens and a tendency to epidemic occurrence.

Around 168 BC, the herbal remedy ''Qing-hao'' ( 青蒿) (''Artemisia annua

''Artemisia annua'', also known as sweet wormwood, sweet annie, sweet sagewort, annual mugwort or annual wormwood (), is a common type of wormwood native to temperate Asia, but naturalized in many countries including scattered parts of North Am ...

'') came into use in China to treat female hemorrhoid

Hemorrhoids (or haemorrhoids), also known as piles, are vascular structures in the anal canal. In their normal state, they are cushions that help with stool control. They become a disease when swollen or inflamed; the unqualified term ''he ...

s ('' Wushi'er bingfang'' translated as "Recipes for 52 kinds of diseases" unearthed from the Mawangdui).

''Qing-hao'' was first recommended for acute intermittent fever episodes by Ge Hong as an effective medication in the 4th-century Chinese manuscript ''Zhou hou bei ji fang'', usually translated as "Emergency Prescriptions kept in one's Sleeve". His recommendation was to soak fresh plants of the artemisia herb in cold water, wring them out, and ingest the expressed bitter juice in their raw state.

"Roman fever" refers to a particularly deadly strain of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

that affected the Roman Campagna and the city of Rome throughout various epochs in history. An epidemic of Roman fever during the fifth century AD may have contributed to the fall of the Roman empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

.The many remedies to reduce the spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

in Pedanius Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, ; 40–90 AD), “the father of pharmacognosy”, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) —a 5-vo ...

's ''De Materia Medica

(Latin name for the Greek work , , both meaning "On Medical Material") is a pharmacopoeia of medicinal plants and the medicines that can be obtained from them. The five-volume work was written between 50 and 70 CE by Pedanius Dioscorides, ...

'' have been suggested to have been a response to chronic malaria in the Roman empire. Some so-called " vampire burials" in late antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

may have been performed in response to malaria epidemics. For example, some children who died of malaria were buried in the necropolis at Lugnano in Teverina using rituals meant to prevent them from returning from the dead. Modern scholars hypothesize that communities feared that the dead would return and spread disease.

In 835, the celebration of Hallowmas

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the church, whether they are know ...

(All Saints Day) was moved from May to November at the behest of Pope Gregory IV

Pope Gregory IV ( la, Gregorius IV; died 25 January 844) was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from October 827 to his death. His pontificate was notable for the papacy’s attempts to intervene in the quarrels between Emperor Loui ...

, on the "practical grounds that Rome in summer could not accommodate the great number of pilgrims who flocked to it", and perhaps because of public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

considerations regarding Roman Fever, which claimed a number of lives of pilgrim

A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) who is on a journey to a holy place. Typically, this is a physical journey (often on foot) to some place of special significance to the adherent of ...

s during the sultry summers of the region.

Middle Ages

During theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, treatments for malaria (and other diseases) included blood-letting, inducing vomiting, limb amputations, and trepanning

Trepanning, also known as trepanation, trephination, trephining or making a burr hole (the verb ''trepan'' derives from Old French from Medieval Latin from Greek , literally "borer, auger"), is a surgical intervention in which a hole is drill ...

. Physicians and surgeons in the period used herbal medicines like belladonna to bring about pain relief in affected patients.

European Renaissance

The name malaria is derived from ''mal aria'' ('bad air' in Medieval Italian). This idea came from the Ancient Romans, who thought that this disease came from pestilential fumes in the swamps. The word malaria has its roots in the miasma theory, as described by historian and chancellor of FlorenceLeonardo Bruni

Leonardo Bruni (or Leonardo Aretino; c. 1370 – March 9, 1444) was an Italian humanist, historian and statesman, often recognized as the most important humanist historian of the early Renaissance. He has been called the first modern historian. ...

in his ''Historiarum Florentini populi libri XII'', which was the first major example of Renaissance historical writing:

The coastal plains of southern Italy fell from international prominence when malaria expanded in the sixteenth century. At roughly the same time, in the coastal marshes of England, mortality from "marsh fever" or "tertian ague" (''ague'': via French from medieval Latin ''acuta'' (''febris''), acute fever) was comparable to that in sub-Saharan Africa today. William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

was born at the start of the especially cold period that climatologists call the " Little Ice Age", yet he was aware enough of the ravages of the disease to mention it in eight of his plays. Malaria was commonplace in London and its marshes then and even into the mid-Victorian era.

Medical accounts and ancient autopsy reports state that tertian malarial fevers caused the death of four members of the prominent Medici

The House of Medici ( , ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first began to gather prominence under Cosimo de' Medici, in the Republic of Florence during the first half of the 15th century. The family originated in the Mu ...

family of Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

. These claims have been confirmed with more modern methodologies.

The Spread to the Americas

Malaria was not referenced in the "medical books" of theMayans

The Maya peoples () are an ethnolinguistic group of indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. The ancient Maya civilization was formed by members of this group, and today's Maya are generally descended from people who lived within that historical reg ...

or Aztecs. Despite this, antibodies against malaria have been detected in some South American mummies, indicating that some malaria strains in the Americas might have a pre-Columbian origin. European settlers and the West Africans they enslaved likely brought malaria to the Americas in the 16th century.

In the book '' 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created'', the author Charles Mann cites sources that speculate that the reason African slaves were brought to the British Americas was because of their resistance to malaria. The colonies needed low-paid agricultural labor, and large numbers of poor British were ready to emigrate. North of the Mason–Dixon line

The Mason–Dixon line, also called the Mason and Dixon line or Mason's and Dixon's line, is a demarcation line separating four U.S. states, forming part of the borders of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and West Virginia (part of Virginia ...

, where malaria-transmitting mosquitoes did not fare well, British indentured servants proved more profitable, as they would work toward their freedom. However, as malaria spread to places such as the tidewater of Virginia and South Carolina, the owners of large plantations came to rely on the enslavement of more malaria-resistant West Africans, while white small landholders risked ruin whenever they got sick. The disease also helped weaken the Native American population and made them more susceptible to other diseases.

Malaria caused huge losses to British forces in the South during the Revolutionary War as well as to Union forces during the Civil War.

Cinchona tree

Spanish missionaries found that fever was treated byAmerindians

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the Am ...

near Loxa (Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

) with powder from Peruvian bark

Jesuit's bark, also known as cinchona bark, Peruvian bark or China bark, is a former remedy for malaria, as the bark contains quinine used to treat the disease. The bark of several species of the genus ''Cinchona'', family Rubiaceae indigenous t ...

(later established to be from any of several trees of genus '' Cinchona''). It was used by the Quechua

Quechua may refer to:

*Quechua people, several indigenous ethnic groups in South America, especially in Peru

*Quechuan languages, a Native South American language family spoken primarily in the Andes, derived from a common ancestral language

**So ...

Indians of Ecuador to reduce the shaking effects caused by severe chills. Jesuit Brother Agostino Salumbrino (1561–1642), who lived in Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

and was an apothecary

''Apothecary'' () is a mostly archaic term for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses '' materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons, and patients. The modern chemist (British English) or pharmacist (British and North Amer ...

by training, observed the Quechua using the bark of the cinchona tree for that purpose. While its effect in treating malaria (and hence malaria-induced shivering) was unrelated to its effect in controlling shivering from cold, it was nevertheless effective for malaria. The use of the "fever tree" bark was introduced into European medicine by Jesuit missionaries (Jesuit's bark

Jesuit's bark, also known as cinchona bark, Peruvian bark or China bark, is a former remedy for malaria, as the bark contains quinine used to treat the disease. The bark of several species of the genus ''Cinchona'', family Rubiaceae indigenous t ...

). Jesuit Bernabé de Cobo (1582–1657), who explored Mexico and Peru, is credited with taking cinchona bark to Europe. He brought the bark from Lima to Spain, and then to Rome and other parts of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, in 1632. Francesco Torti wrote in 1712 that only "intermittent fever" was amenable to the fever tree bark. This work finally established the specific nature of cinchona bark and brought about its general use in medicine.

It would be nearly 200 years before the active principles, quinine and other alkaloid

Alkaloids are a class of basic, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Some synthetic compounds of similar ...

s, of cinchona bark were isolated. Quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal le ...

, a toxic plant alkaloid, is, in addition to its anti-malarial properties, moderately effective against nocturnal leg cramp

A cramp is a sudden, involuntary, painful skeletal muscle contraction or overshortening associated with electrical activity; while generally temporary and non-damaging, they can cause significant pain and a paralysis-like immobility of the aff ...

s.

Clinical indications

In 1717, the dark pigmentation of a postmortemspleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

and brain was published by the epidemiologist Giovanni Maria Lancisi in his malaria textbook ''De noxiis paludum effluviis eorumque remediis''. This was one of the earliest reports of the characteristic enlargement of the spleen and dark color of the spleen and brain, which are the most constant post-mortem indications of chronic malaria infection. He related the prevalence of malaria in swampy areas to the presence of flies

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advanced m ...

and recommended swamp drainage

Drainage is the natural or artificial removal of a surface's water and sub-surface water from an area with excess of water. The internal drainage of most agricultural soils is good enough to prevent severe waterlogging (anaerobic condition ...

to prevent it.

19th century

In the nineteenth century, the first drugs were developed to treat malaria, and parasites were first identified as its source.Antimalarial drugs

Quinine

French chemist

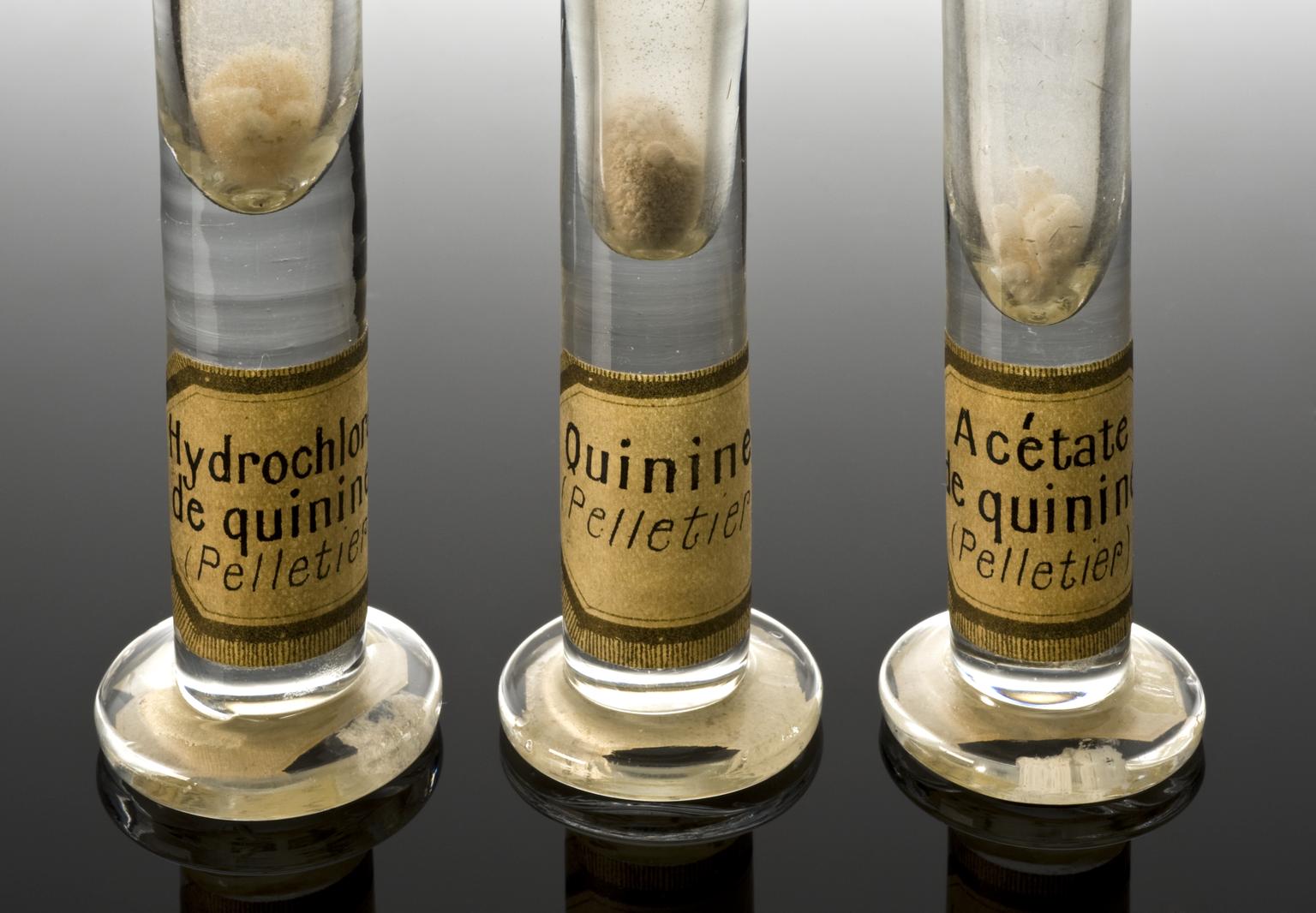

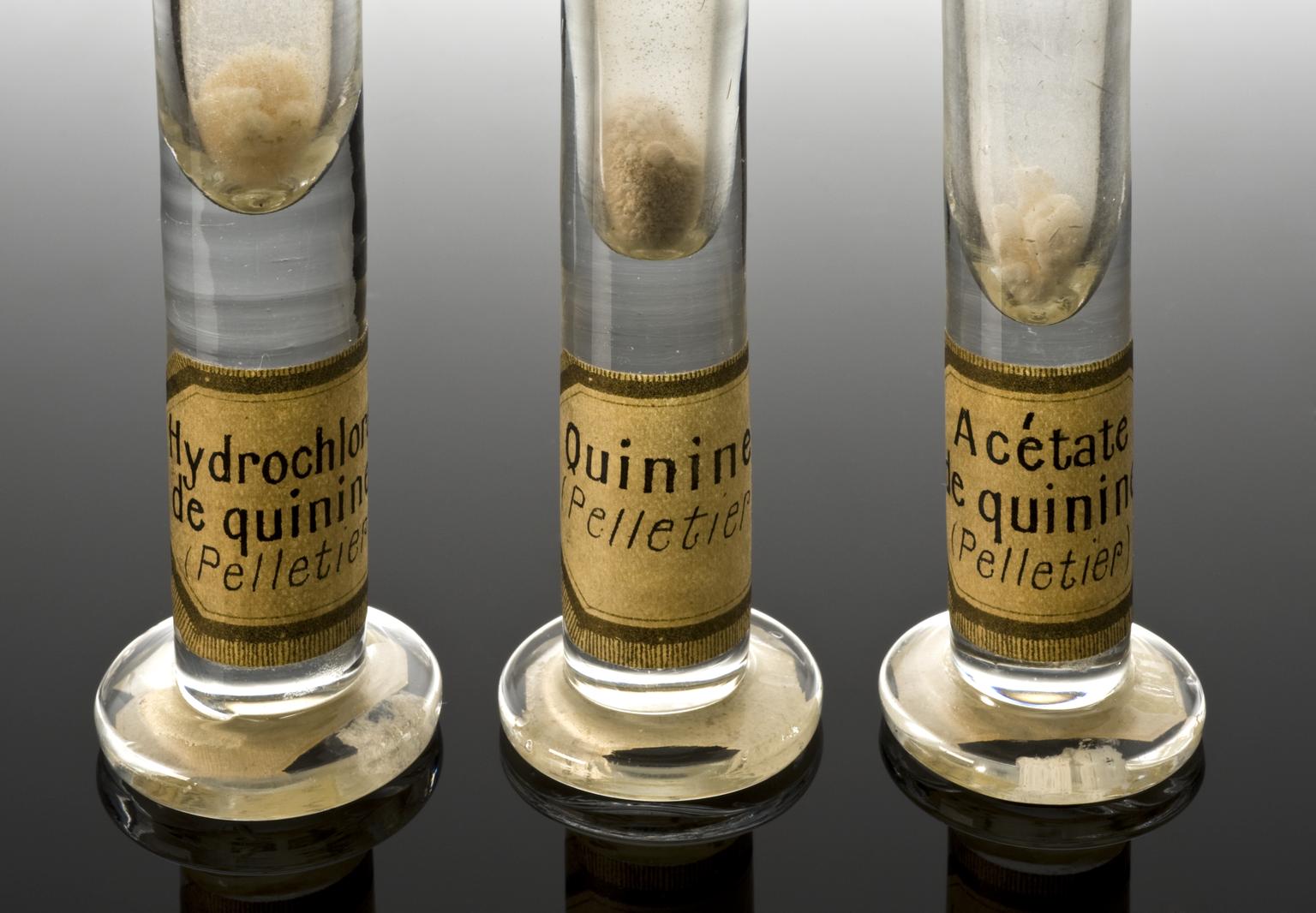

French chemist Pierre Joseph Pelletier

Pierre-Joseph Pelletier (, , ; 22 March 1788 – 19 July 1842) was a French chemist and pharmacist who did notable research on vegetable alkaloids, and was the co-discoverer with Joseph Bienaimé Caventou of quinine, caffeine, and strychnine ...

and French pharmacist Joseph Bienaimé Caventou

Joseph Bienaimé Caventou (30 June 1795 – 5 May 1877) was a French pharmacist. He was a professor at the École de Pharmacie (School of Pharmacy) in Paris. He collaborated with Pierre-Joseph Pelletier in a Parisian laboratory located behind an ...

separated in 1820 the alkaloids cinchonine and quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal le ...

from powdered fever tree bark, allowing for the creation of standardized doses of the active ingredients. Prior to 1820, the bark was simply dried, ground to a fine powder and mixed into a liquid (commonly wine) for drinking.

Manuel Incra Mamani

Manuel Incra Mamani was a Bolivian Incan ''cascarillero'' (bark and seed hunter) who found a cinchona tree that had a higher proportion of quinine than most others. It went into commercial cultivation, providing most of the world's quinine.

Life ...

spent four years collecting cinchona seeds in the Andes in Bolivia, highly prized for their quinine but whose export was prohibited. He provided them to an English trader, Charles Ledger

Charles Ledger (4 March 1818 – 19 May 1905)B. G. Andrews,, ''Australian Dictionary of Biography'', Volume 5, Melbourne University Press, MUP, 1974, pp 73-74. Retrieved 9 Sep 2009

was an alpaca farmer noted for his work in connection with quini ...

, who sent the seeds to his brother in England to sell. They sold them to the Dutch government, who cultivated 20,000 trees of the '' Cinchona ledgeriana'' in Java (Indonesia). By the end of the nineteenth century, the Dutch had established a world monopoly over its supply.

'Warburg's Tincture'

In 1834, in British Guiana, a German physician, Carl Warburg, invented anantipyretic

An antipyretic (, from ''anti-'' 'against' and ' 'feverish') is a substance that reduces fever. Antipyretics cause the hypothalamus to override a prostaglandin-induced increase in temperature. The body then works to lower the temperature, which r ...

medicine: ' Warburg's Tincture'. This secret, proprietary remedy contained quinine and other herbs. Trials were held in Europe in the 1840s and 1850s. It was officially adopted by the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

in 1847. It was considered by many eminent medical professionals to be a more efficacious antimalarial

Antimalarial medications or simply antimalarials are a type of antiparasitic chemical agent, often naturally derived, that can be used to treat or to prevent malaria, in the latter case, most often aiming at two susceptible target groups, young ...

than quinine. It was also more economical. The British government supplied Warburg's Tincture to troops in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and other colonies.

Methylene blue

In 1876, methylene blue was synthesized by German chemistHeinrich Caro

Heinrich Caro (February 13, 1834 in Posen, Prussia Germany now Poznań, Poland – September 11, 1910 in Dresden), was a German chemist.

He was a Sephardic Jew. He started his study of chemistry at the Friedrich Wilhelms University and later ...

. Paul Ehrlich

Paul Ehrlich (; 14 March 1854 – 20 August 1915) was a Nobel Prize-winning German physician and scientist who worked in the fields of hematology, immunology, and antimicrobial chemotherapy. Among his foremost achievements were finding a cure ...

in 1880 described the use of "neutral" dyes—mixtures of acidic and basic dyes—for the differentiation of cells in peripheral blood smears. In 1891, Ernst Malachowski and Dmitri Leonidovich Romanowsky

Dmitri Leonidovich Romanowsky (sometimes spelled Dmitry and Romanowski, russian: Дмитрий Леонидович Романовский; 1861–1921) was a Russian physician who is best known for his invention of an eponymous histological stai ...

independently developed techniques using a mixture of Eosin

Eosin is the name of several fluorescent acidic compounds which bind to and form salts with basic, or eosinophilic, compounds like proteins containing amino acid residues such as arginine and lysine, and stains them dark red or pink as a resul ...

Y and modified methylene blue (methylene azure) that produced a surprising hue

In color theory, hue is one of the main properties (called color appearance parameters) of a color, defined technically in the CIECAM02 model as "the degree to which a stimulus can be described as similar to or different from stimuli that ...

unattributable to either staining component: a shade of purple. Malachowski used alkali-treated methylene blue solutions and Romanowsky used methylene blue solutions that were molded or aged. This new method differentiated blood cell

A blood cell, also called a hematopoietic cell, hemocyte, or hematocyte, is a cell produced through hematopoiesis and found mainly in the blood. Major types of blood cells include red blood cells (erythrocytes), white blood cells (leukocytes) ...

s and demonstrated the nuclei of malarial parasites. Malachowski's staining technique was one of the most significant technical advances in the history of malaria.

In 1891, Paul Guttmann and Ehrlich noted that methylene blue had a high affinity for some tissues and that this dye had a slight antimalarial property. Methylene blue and its congeners may act by preventing the biocrystallization of heme

Heme, or haem (pronounced / hi:m/ ), is a precursor to hemoglobin, which is necessary to bind oxygen in the bloodstream. Heme is biosynthesized in both the bone marrow and the liver.

In biochemical terms, heme is a coordination complex "consis ...

.

Cause: Identification of ''Plasmodium'' and ''Anopheles''

In 1848, German anatomist Johann Heinrich Meckel recorded black-brown pigment granules in the blood andspleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

of a patient who had died in a mental hospital. Meckel was thought to have been looking at malaria parasites

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

without realizing it; he did not mention malaria in his report. He hypothesized that the pigment was melanin

Melanin (; from el, μέλας, melas, black, dark) is a broad term for a group of natural pigments found in most organisms. Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amino ...

. The causal relationship of pigment to the parasite was established in 1880, when French physician Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran, working in the military hospital of Constantine, Algeria, observed pigmented parasites inside the red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "holl ...

s of people with malaria. He witnessed the events of exflagellation and became convinced that the moving flagella were parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

microorganisms. He noted that quinine removed the parasites from the blood. Laveran called this microscopic organism ''Oscillaria malariae'' and proposed that malaria was caused by this protozoan. This discovery remained controversial until the development of the oil immersion

In light microscopy, oil immersion is a technique used to increase the resolving power of a microscope. This is achieved by immersing both the objective lens and the specimen in a transparent oil of high refractive index, thereby increasing the ...

lens in 1884 and of superior staining methods in 1890–1891.

In 1885, Ettore Marchiafava, Angelo Celli and Camillo Golgi

Camillo Golgi (; 7 July 184321 January 1926) was an Italian biologist and pathologist known for his works on the central nervous system. He studied medicine at the University of Pavia (where he later spent most of his professional career) betwee ...

studied the reproduction cycles in human blood (Golgi cycles). Golgi observed that all parasites present in the blood divided almost simultaneously at regular intervals and that division coincided with attacks of fever. In 1886 Golgi described the morphological differences that are still used to distinguish two malaria parasite species ''Plasmodium vivax

''Plasmodium vivax'' is a protozoal parasite and a human pathogen. This parasite is the most frequent and widely distributed cause of recurring malaria. Although it is less virulent than ''Plasmodium falciparum'', the deadliest of the five huma ...

'' and ''Plasmodium malariae

''Plasmodium malariae'' is a parasitic protozoan that causes malaria in humans. It is one of several species of ''Plasmodium'' parasites that infect other organisms as pathogens, also including ''Plasmodium falciparum'' and ''Plasmodium vivax'' ...

''. Shortly after this Sakharov in 1889 and Marchiafava & Celli in 1890 independently identified '' Plasmodium falciparum'' as a species distinct from ''P. vivax'' and ''P. malariae''. In 1890, Grassi and Feletti reviewed the available information and named both ''P. malariae'' and ''P. vivax'' (although within the genus '' Haemamoeba''.) By 1890, Laveran's germ was generally accepted, but most of his initial ideas had been discarded in favor of the taxonomic work and clinical pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

of the Italian school. Marchiafava and Celli called the new microorganism ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a ver ...

''. ''H. vivax'' was soon renamed ''Plasmodium vivax''. In 1892, Marchiafava and Bignami proved that the multiple forms seen by Laveran were from a single species. This species was eventually named ''P. falciparum''. Laveran was awarded the 1907 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, according ...

"in recognition of his work on the role played by protozoa in causing diseases".

Dutch physician Pieter Pel first proposed a tissue stage of the malaria parasite in 1886, presaging its discovery by over 50 years. This suggestion was reiterated in 1893 when Golgi suggested that the parasites might have an undiscovered tissue phase (this time in endothelial cells). Golgi's latent phase theory was supported by Pel in 1896.

The establishment of the scientific method from about the mid-19th century on demanded testable hypotheses and verifiable phenomena for causation and transmission. Anecdotal reports, and the discovery in 1881 that mosquitoes were the vector of yellow fever, eventually led to the investigation of mosquitoes in connection with malaria.

An early effort at malaria prevention occurred in 1896 in Massachusetts. An

The establishment of the scientific method from about the mid-19th century on demanded testable hypotheses and verifiable phenomena for causation and transmission. Anecdotal reports, and the discovery in 1881 that mosquitoes were the vector of yellow fever, eventually led to the investigation of mosquitoes in connection with malaria.

An early effort at malaria prevention occurred in 1896 in Massachusetts. An Uxbridge

Uxbridge () is a suburban town in west London and the administrative headquarters of the London Borough of Hillingdon. Situated west-northwest of Charing Cross, it is one of the major metropolitan centres identified in the London Plan. Uxb ...

outbreak prompted health officer Dr. Leonard White to write a report to the State Board of Health, which led to a study of mosquito-malaria links and the first efforts for malaria prevention. Massachusetts state pathologist, Theobald Smith, asked that White's son collect mosquito specimens for further analysis, and that citizens add screens

Screen or Screens may refer to:

Arts

* Screen printing (also called ''silkscreening''), a method of printing

* Big screen, a nickname associated with the motion picture industry

* Split screen (filmmaking), a film composition paradigm in which m ...

to windows, and drain collections of water.

Britain's Sir Ronald Ross

Sir Ronald Ross (13 May 1857 – 16 September 1932) was a British medical doctor who received the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1902 for his work on the transmission of malaria, becoming the first British Nobel laureate, and the f ...

, an army surgeon working in Secunderabad, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, proved in 1897 that malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes, an event now commemorated by World Mosquito Day. He was able to find pigmented malaria parasites in a mosquito that he artificially fed on a malaria patient who had crescents in his blood. He continued his research into malaria by showing that certain mosquito species (''Culex

''Culex'' is a genus of mosquitoes, several species of which serve as vectors of one or more important diseases of birds, humans, and other animals. The diseases they vector include arbovirus infections such as West Nile virus, Japanese encep ...

fatigans'') transmit malaria to sparrows and he isolated malaria parasites from the salivary glands

The salivary glands in mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands ( parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands. Salivary gl ...

of mosquitoes that had fed on infected birds. He reported this to the British Medical Association in Edinburgh in 1898.

Giovanni Battista Grassi

Giovanni Battista Grassi (27 March 1854 – 4 May 1925) was an Italian physician and zoologist, best known for his pioneering works on parasitology, especially on malariology. He was Professor of Comparative Zoology at the University of Catani ...

, professor of Comparative Anatomy at Rome University, showed that human malaria could only be transmitted by ''Anopheles

''Anopheles'' () is a genus of mosquito first described and named by J. W. Meigen in 1818. About 460 species are recognised; while over 100 can transmit human malaria, only 30–40 commonly transmit parasites of the genus ''Plasmodium'', which ...

'' (Greek ''anofelís'': good-for-nothing) mosquitoes. Grassi, along with coworkers Amico Bignami, Giuseppe Bastianelli and Ettore Marchiafava, announced at the session of the Accademia dei Lincei on 4 December 1898 that a healthy man in a non-malarial zone had contracted tertian malaria after being bitten by an experimentally infected ''Anopheles claviger'' specimen.

In 1898–1899, Bastianelli, Bignami and Grassi were the first to observe the complete transmission cycle of ''P. falciparum'', ''P. vivax'' and ''P. malaria'' from mosquito to human and back in ''A. claviger''.

A dispute broke out between the British and Italian schools of malariology over priority, but Ross received the 1902 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for "his work on malaria, by which he has shown how it enters the organism and thereby has laid the foundation for successful research on this disease and methods of combating it."

Synthesis of quinine

William Henry Perkin

Sir William Henry Perkin (12 March 1838 – 14 July 1907) was a British chemist and entrepreneur best known for his serendipitous discovery of the first commercial synthetic organic dye, mauveine, made from aniline. Though he failed in tryin ...

, a student of August Wilhelm von Hofmann

August Wilhelm von Hofmann (8 April 18185 May 1892) was a German chemist who made considerable contributions to organic chemistry. His research on aniline helped lay the basis of the aniline-dye industry, and his research on coal tar laid the g ...

at the Royal College of Chemistry

The Royal College of Chemistry: the laboratories. Lithograph

The Royal College of Chemistry (RCC) was a college originally based on Oxford Street in central London, England. It operated between 1845 and 1872.

The original building was designed ...

in London, unsuccessfully tried in the 1850s to synthesize quinine in a commercial process. The idea was to take two equivalents of N-allyltoluidine () and three atoms of oxygen to produce quinine () and water. Instead, Perkin's mauve was produced when attempting quinine total synthesis

The total synthesis of quinine, a naturally-occurring antimalarial drug, was developed over a 150-year period. The development of synthetic quinine is considered a milestone in organic chemistry although it has never been produced industrially as a ...

via the oxidation of N-allyltoluidine. Before Perkin's discovery, all dyes and pigments were derived from roots, leaves, insects, or, in the case of Tyrian purple

Tyrian purple ( grc, πορφύρα ''porphúra''; la, purpura), also known as Phoenician red, Phoenician purple, royal purple, imperial purple, or imperial dye, is a reddish-purple natural dye. The name Tyrian refers to Tyre, Lebanon. It i ...

, molluscs

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is estim ...

.

Quinine wouldn't be successfully synthesized until 1918. Synthesis remains elaborate, expensive and low yield, with the additional problem of separation of the stereoisomers

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms ...

. Though quinine is not one of the major drugs used in treatment, modern production still relies on extraction from the cinchona tree.

20th century

Etiology: Plasmodium tissue stage and reproduction

Relapses were first noted in 1897 by William S. Thayer, who recounted the experiences of a physician who relapsed 21 months after leaving an endemic area. He proposed the existence of a tissue stage. Relapses were confirmed by Patrick Manson, who allowed infected ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes to feed on his eldest son. The younger Manson then described a relapse nine months after his apparent cure with quinine. Also, in 1900 Amico Bignami and Giuseppe Bastianelli found that they could not infect an individual with blood containing onlygametocyte

A gametocyte is a eukaryotic germ cell that divides by mitosis into other gametocytes or by meiosis into gametids during gametogenesis. Male gametocytes are called ''spermatocytes'', and female gametocytes are called ''oocytes''.

Development

...

s. The possibility of the existence of a chronic blood stage infection was proposed by Ronald Ross and David Thompson in 1910.

The existence of asexually-reproducing avian malaria parasites in cells of the internal organs was first demonstrated by Henrique de Beaurepaire Aragão in 1908.

Three possible mechanisms of relapse were proposed by Marchoux in 1926 (i) parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek grc, παρθένος, translit=parthénos, lit=virgin, label=none + grc, γένεσις, translit=génesis, lit=creation, label=none) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which growth and developmen ...

of macrogametocyte

A gametocyte is a eukaryotic germ cell that divides by mitosis into other gametocytes or by meiosis into gametids during gametogenesis. Male gametocytes are called ''spermatocytes'', and female gametocytes are called ''oocytes''.

Development

...

s: (ii) persistence of schizont

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism is ...

s in small numbers in the blood where immunity inhibits multiplication, but later disappears and/or (iii) reactivation of an encysted body in the blood. James in 1931 proposed that sporozoites

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism is ...

are carried to internal organs, where they enter reticuloendothelial cells and undergo a cycle of development, based on quinine's lack of activity on them. Huff and Bloom in 1935 demonstrated stages of avian malaria that transpire outside blood cells (exoerythrocytic). In 1945 Fairley ''et al.'' reported that inoculation of blood from a patient with ''P. vivax'' may fail to induce malaria, although the donor may subsequently exhibit the condition. Sporozoites disappeared from the blood stream within one hour and reappeared eight days later. This suggests the presence of forms that persist in tissues. Using mosquitoes rather than blood, in 1946 Shute described a similar phenomenon and proposed the existence of an 'x-body' or resting form. The following year Sapero proposed a link between relapse and a tissue stage not yet discovered. Garnham in 1947 described exoerythrocytic schizogony in '' Hepatocystis (Plasmodium) kochi''. In the following year, Shortt and Garnham described the liver stages of ''P. cynomolgi'' in monkeys. In the same year, a human volunteer consented to receive a massive dose of infected sporozoites of '' P. vivax'' and undergo a liver biopsy three months later, thus allowing Shortt ''et al.'' to demonstrate the tissue stage. The tissue form of ''Plasmodium ovale

''Plasmodium ovale'' is a species of parasitic protozoon that causes tertian malaria in humans. It is one of several species of ''Plasmodium'' parasites that infect humans, including ''Plasmodium falciparum'' and ''Plasmodium vivax'' which are ...

'' was described in 1954 and that of ''P. malariae'' in 1960 in experimentally infected chimpanzees.

The latent or dormant liver form of the parasite (hypnozoite), apparently responsible for the relapses characteristic of ''P. vivax'' and ''P. ovale'' infections, was first observed in the 1980s. The term ''hypnozoite'' was coined by Miles B. Markus while a student. In 1976, he speculated: "If sporozoites of ''Isospora'' can behave in this fashion, then those of related Sporozoa, like malaria parasites, may have the ability to survive in the tissues in a similar way." In 1982, Krotoski ''et al'' reported identification of ''P. vivax'' hypnozoites in liver cells of infected chimpanzees.

From 1980 onwards and until recently (even in 2022), recurrences of ''P. vivax'' malaria have been thought to be mostly hypnozoite-mediated. Between 2018 and 2021, however, it was reported that vast numbers of non-circulating, non-hypnozoite parasites occur unobtrusively in tissues of ''P. vivax''-infected people, with only a small proportion of the total parasite biomass present in the peripheral bloodstream. This finding supports an intellectually insightful paradigm-shifting viewpoint, which has prevailed since 2011 (albeit not believed between 2011 and 2018 or later by most malariologists), that an unknown percentage of ''P. vivax'' recurrences are recrudescences (having a non-circulating or sequestered merozoite origin), and not relapses (which have a hypnozoite source). The recent discoveries did not give rise to this new theory, which was pre-existing. They merely confirmed the validity thereof.

Malariotherapy

In the early twentieth century, before antibiotics, patients with tertiary syphilis were intentionally infected with malaria to induce a fever; this was called malariotherapy. In 1917, Julius Wagner-Jauregg, a Viennese psychiatrist, began to treat neurosyphilitics with induced ''Plasmodium vivax

''Plasmodium vivax'' is a protozoal parasite and a human pathogen. This parasite is the most frequent and widely distributed cause of recurring malaria. Although it is less virulent than ''Plasmodium falciparum'', the deadliest of the five huma ...

'' malaria. Three or four bouts of fever were enough to kill the temperature-sensitive syphilis bacteria (''Spirochaeta pallida'' also known as ''Treponema pallidum''). ''P. vivax'' infections were then terminated by quinine. By accurately controlling the fever with quinine, the effects of both syphilis and malaria could be minimized. While about 15% of patients died from malaria, this was preferable to the almost-certain death from syphilis. Malaria therapy, Therapeutic malaria opened up a wide field of chemotherapeutic research and was practiced until 1950. Wagner-Jauregg was awarded the 1927 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the therapeutic value of malaria inoculation in the treatment of dementia paralytica.

Henry Heimlich advocated malariotherapy as a treatment for AIDS, and some studies of malariotherapy for HIV infection have been performed in China. The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does not recommend the use of malariotherapy for HIV.

Panama Canal and vector control

In 1881, Dr. Carlos Finlay, a Cuban-born physician of Scottish ancestry, theorized that yellow fever was transmitted by a specific mosquito, later designated ''Aedes aegypti''. The theory remained controversial for twenty years until it was confirmed in 1901 by Walter Reed. This was the first scientific proof of a disease being transmitted exclusively by an insect vector, and demonstrated that control of such diseases necessarily entailed control or eradication of their insect vector. Yellow fever and malaria among workers had seriously delayed construction of the Panama Canal. Mosquito control instituted by William C. Gorgas dramatically reduced this problem.Antimalarial drugs

Chloroquine

Hans Andersag, Johann "Hans" Andersag and colleagues synthesized and tested some 12,000 compounds, eventually producing Resochin as a substitute for quinine in the 1930s. It is chemically related to quinine through the possession of a quinoline nucleus and the dialkylaminoalkylamino side chain. Resochin (7-chloro-4- 4- (diethylamino) – 1 – methylbutyl amino quinoline) and a similar compound Sontochin (3-methyl Resochin) were synthesized in 1934. In March 1946, the drug was officially named Chloroquine. Chloroquine is an inhibitor of hemozoin production through biocrystallization. Quinine and chloroquine affect malarial parasites only at life stages when the parasites are forming hematin-pigment (hemozoin) as a byproduct of hemoglobin degradation.

Chloroquine-resistant forms of ''P. falciparum'' emerged only 19 years later. The first resistant strains were detected around the Cambodia‐Thailand border and in Colombia, in the 1950s. In 1989, chloroquine resistance in ''P. vivax'' was reported in Papua New Guinea. These resistant strains spread rapidly, producing a large mortality increase, particularly in Africa during the 1990s.

Hans Andersag, Johann "Hans" Andersag and colleagues synthesized and tested some 12,000 compounds, eventually producing Resochin as a substitute for quinine in the 1930s. It is chemically related to quinine through the possession of a quinoline nucleus and the dialkylaminoalkylamino side chain. Resochin (7-chloro-4- 4- (diethylamino) – 1 – methylbutyl amino quinoline) and a similar compound Sontochin (3-methyl Resochin) were synthesized in 1934. In March 1946, the drug was officially named Chloroquine. Chloroquine is an inhibitor of hemozoin production through biocrystallization. Quinine and chloroquine affect malarial parasites only at life stages when the parasites are forming hematin-pigment (hemozoin) as a byproduct of hemoglobin degradation.

Chloroquine-resistant forms of ''P. falciparum'' emerged only 19 years later. The first resistant strains were detected around the Cambodia‐Thailand border and in Colombia, in the 1950s. In 1989, chloroquine resistance in ''P. vivax'' was reported in Papua New Guinea. These resistant strains spread rapidly, producing a large mortality increase, particularly in Africa during the 1990s.

Artemisinins

Systematic screening of Chinese herbology, traditional Chinese medical herbs was carried out by Chinese research teams, consisting of hundreds of scientists in the 1960s and 1970s. Qinghaosu, later namedartemisinin

Artemisinin () and its semisynthetic derivatives are a group of drugs used in the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum''. It was discovered in 1972 by Tu Youyou, who shared the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her ...

, was cold-extracted in a neutral milieu (pH 7.0) from the dried leaves of ''Artemisia annua

''Artemisia annua'', also known as sweet wormwood, sweet annie, sweet sagewort, annual mugwort or annual wormwood (), is a common type of wormwood native to temperate Asia, but naturalized in many countries including scattered parts of North Am ...

''.

Artemisinin was isolated by pharmacologist Tu Youyou (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 2015). Tu headed a team tasked by the Chinese government with finding a treatment for chloroquine-resistant malaria. Their work was known as Project 523, named after the date it was announced – 23 May 1967. The team investigated more than 2000 Chinese herb preparations and by 1971 had made 380 extracts from 200 herbs. An extract from qinghao (''Artemisia annua

''Artemisia annua'', also known as sweet wormwood, sweet annie, sweet sagewort, annual mugwort or annual wormwood (), is a common type of wormwood native to temperate Asia, but naturalized in many countries including scattered parts of North Am ...

'') was effective, but the results were variable. Tu reviewed the literature, including ''Zhou hou bei ji fang'' (A handbook of prescriptions for emergencies) written in 340 BC by Chinese physician Ge Hong. This book contained the only useful reference to the herb: "A handful of qinghao immersed in two litres of water, wring out the juice and drink it all." Tu's team subsequently isolated a nontoxic, neutral extract that was 100% effective against parasitemia in animals. The first successful trials of artemisinin were in 1979.

Artemisinin is a sesquiterpene lactone containing a peroxide group, which is believed to be essential for its anti-malarial activity. Its derivatives, artesunate and artemether, have been used in clinics since 1987 for the treatment of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive malaria, especially cerebral malaria. These drugs are characterized by fast action, high efficacy, and good tolerance. They kill the asexual forms of ''Plasmodium berghei, P. berghei'' and ''P. cynomolgi'' and have transmission-blocking activity. In 1985, Zhou Yiqing and his team combined artemether and lumefantrine into a single tablet, which was registered as a medicine in China in 1992. Later, it became known as Artemether/lumefantrine, "Coartem". Artemisinin combination treatments (ACTs) are now widely used to treat uncomplicated ''falciparum'' malaria, but access to ACTs is still limited in most malaria-endemic countries, and only a minority of the patients who need artemisinin-based combination treatments receive them.

In 2008, White predicted that improved agricultural practices, selection of high-yielding hybrids, Microorganism, microbial production, and the development of synthetic peroxides would lower prices.

Artemisinin is a sesquiterpene lactone containing a peroxide group, which is believed to be essential for its anti-malarial activity. Its derivatives, artesunate and artemether, have been used in clinics since 1987 for the treatment of drug-resistant and drug-sensitive malaria, especially cerebral malaria. These drugs are characterized by fast action, high efficacy, and good tolerance. They kill the asexual forms of ''Plasmodium berghei, P. berghei'' and ''P. cynomolgi'' and have transmission-blocking activity. In 1985, Zhou Yiqing and his team combined artemether and lumefantrine into a single tablet, which was registered as a medicine in China in 1992. Later, it became known as Artemether/lumefantrine, "Coartem". Artemisinin combination treatments (ACTs) are now widely used to treat uncomplicated ''falciparum'' malaria, but access to ACTs is still limited in most malaria-endemic countries, and only a minority of the patients who need artemisinin-based combination treatments receive them.

In 2008, White predicted that improved agricultural practices, selection of high-yielding hybrids, Microorganism, microbial production, and the development of synthetic peroxides would lower prices.

Insecticides

Efforts to control the spread of malaria had a major setback in 1930: Entomology, entomologist Raymond Corbett Shannon discovered imported disease-bearing ''Anopheles gambiae'' mosquitoes living in Brazil (DNA analysis later revealed the actual species to be ''A. arabiensis''). This species of mosquito is a particularly efficient vector for malaria and is native to Africa. In 1938, the introduction of this vector caused the greatest epidemic of malaria ever seen in the New World. However, complete eradication of ''A. gambiae'' from northeast Brazil and thus from the New World was achieved in 1940 by the systematic application of the arsenic-containing compound Paris green to breeding places, and of pyrethrum spray-killing to adult resting places.DDT

The Austrian chemist Othmar Zeidler is credited with the first synthesis of DDT (DichloroDiphenylTrichloroethane) in 1874. The insecticidal properties of DDT were identified in 1939 by chemist Paul Hermann Müller of Novartis, Geigy Pharmaceutical. For his discovery of DDT as a contact poison against several arthropods, he was awarded the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. In the fall of 1942, samples of the chemical were acquired by the United States, Britain and Germany. Laboratory tests demonstrated that it was highly effective against many insects. Rockefeller Foundation studies showed in Mexico that DDT remained effective for six to eight weeks if sprayed on the inside walls and ceilings of houses and other buildings. The first field test in which residual DDT was applied to the interior surfaces of all habitations and outbuildings was carried out in centralItaly

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

in the spring of 1944. The objective was to determine the residual effect of the spray on anopheline density in the absence of other control measures. Spraying began in Castel Volturno and, after a few months, in the delta of the Tiber. The unprecedented effectiveness of the chemical was confirmed: the new insecticide was able to eradicate malaria by eradicating mosquitoes. At the end of World War II, a massive malaria control program based on DDT spraying was carried out in Italy. In Sardinia – the second largest island in the Mediterranean – between 1946 and 1951, the Rockefeller Foundation conducted a large-scale experiment to test the feasibility of the strategy of "species eradication" in an endemic malaria vector. Malaria was effectively eliminated in the United States by the use of DDT in the National Malaria Eradication Program (1947–52). The concept of eradication prevailed in 1955 in the Eighth World Health Assembly: DDT was adopted as a primary tool in the fight against malaria.

In 1953, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched an antimalarial program in parts of Liberia as a pilot project to determine the feasibility of malaria eradication in tropical Africa. However, these projects encountered difficulties that foreshadowed the general retreat from malaria eradication efforts across tropical Africa by the mid-1960s.