Maralinga Range on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Between 1956 and 1963, the United Kingdom conducted seven

In the 1950s Britain was still Australia's largest trading partner, although it was overtaken by Japan and the United States by the 1960s. Britain and Australia still had strong cultural ties, and

In the 1950s Britain was still Australia's largest trading partner, although it was overtaken by Japan and the United States by the 1960s. Britain and Australia still had strong cultural ties, and

The site, initially known as X.300, was nowhere near as good as the Nevada Test Site, with its excellent communications, but was considered acceptable. It was flat and dry, but not affected by dust storms like Emu Field, and the geologists were confident that the desired per annum could be obtained by boring. Rainwater tanks were recommended, and it was estimated that if

The site, initially known as X.300, was nowhere near as good as the Nevada Test Site, with its excellent communications, but was considered acceptable. It was flat and dry, but not affected by dust storms like Emu Field, and the geologists were confident that the desired per annum could be obtained by boring. Rainwater tanks were recommended, and it was estimated that if

A railhead and a quarry were established at

A railhead and a quarry were established at  The task force, which began assembling in February 1956, included a section from the

The task force, which began assembling in February 1956, included a section from the  Pressed for time, Magee became involved in a series of disputes with the Woomera Range commander, who tried to divert his sappers onto other tasks. In June, the range commander ordered the surveyors to return to Adelaide, which would have brought the work at Maralinga to a halt. Magee went over his head and appealed to the commander of Central Command,

Pressed for time, Magee became involved in a series of disputes with the Woomera Range commander, who tried to divert his sappers onto other tasks. In June, the range commander ordered the surveyors to return to Adelaide, which would have brought the work at Maralinga to a halt. Magee went over his head and appealed to the commander of Central Command,

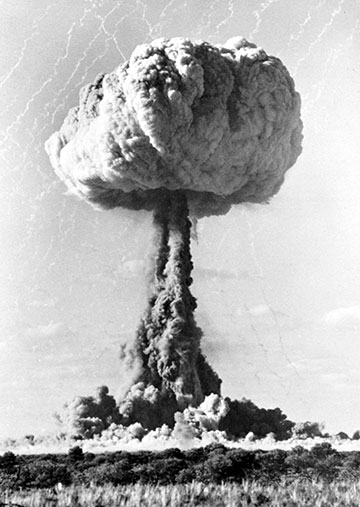

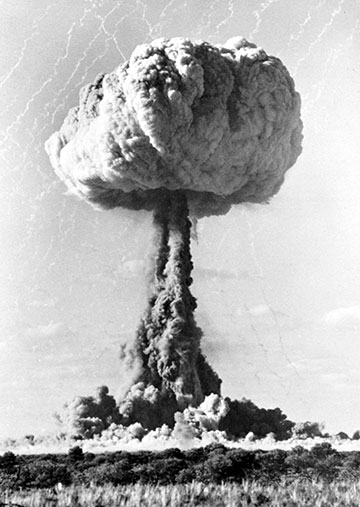

The first test, codenamed One Tree, was a tower-mounted test of

The first test, codenamed One Tree, was a tower-mounted test of  The schedule was revised to allow for a morning (07:00) or evening (17:00) test, and after a few days of unfavourable weather it was rescheduled for 23 September. Once again the politicians arrived but returned disappointed. This put Penney under great pressure. On the one hand, if Maralinga was to be used for many years then riding roughshod over Australian concerns about safety at an early date was inadvisable; on the other, there was the urgent need to test Red Beard in time for the upcoming

The schedule was revised to allow for a morning (07:00) or evening (17:00) test, and after a few days of unfavourable weather it was rescheduled for 23 September. Once again the politicians arrived but returned disappointed. This put Penney under great pressure. On the one hand, if Maralinga was to be used for many years then riding roughshod over Australian concerns about safety at an early date was inadvisable; on the other, there was the urgent need to test Red Beard in time for the upcoming  Some observers were surprised that the detonation seemed to be silent; the sound wave arrived a few seconds later. The yield was estimated at . The cloud rose to , much higher than expected. After about eight minutes, a

Some observers were surprised that the detonation seemed to be silent; the sound wave arrived a few seconds later. The yield was estimated at . The cloud rose to , much higher than expected. After about eight minutes, a

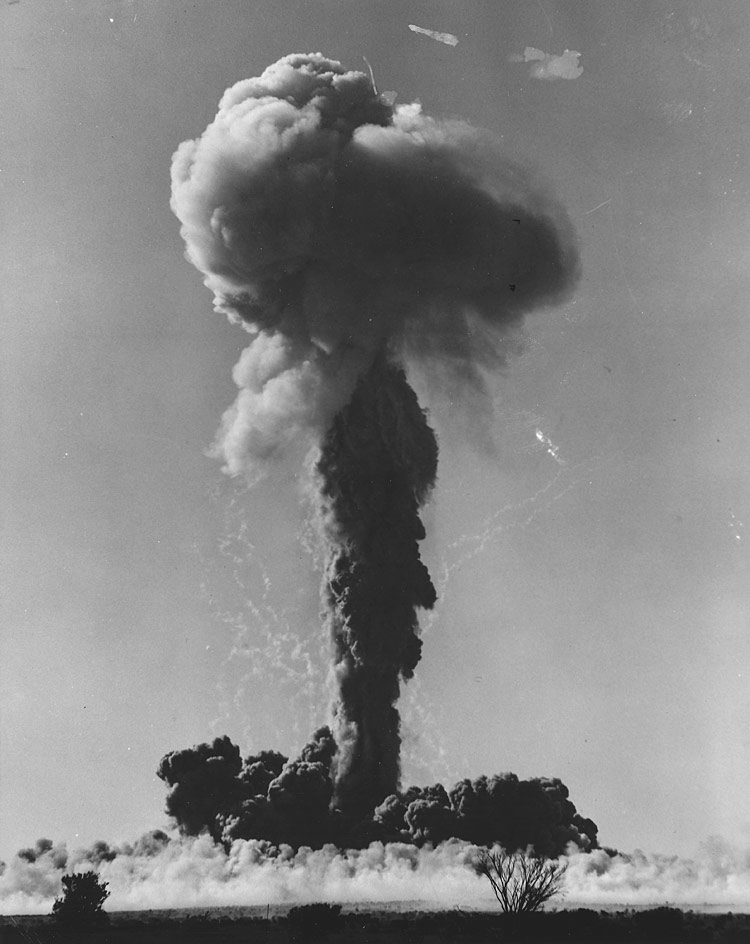

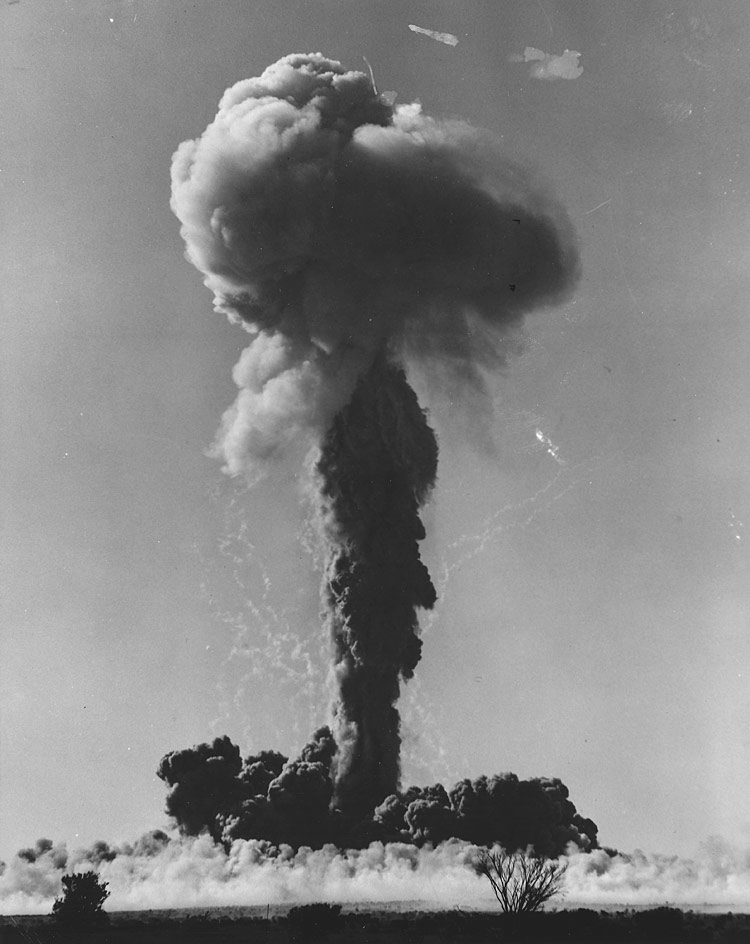

The next test was Marcoo, a ground test using a Blue Danube device with a low-yield core. In the hope that sharing the results might lead to fuller cooperation, the test had been discussed with the Americans by the

The next test was Marcoo, a ground test using a Blue Danube device with a low-yield core. In the hope that sharing the results might lead to fuller cooperation, the test had been discussed with the Americans by the

Kite was an air drop using a Blue Danube device with a low-yield core, the only air drop conducted during Operation Buffalo. Originally the air drop was supposed to be the last test of Operation Buffalo, but after the Marcoo shot Penney decided to swap the last two tests, making the air drop the third test. The air drop was the most difficult test, as the worst-case scenario involved the radar fuses failing and the bomb detonating on impact with the ground, which would result in severe fallout. The RAF therefore conducted a series of practice drops with high explosive bombs. In the end, in view of the AWTSC's concerns about the dangers of a test, a low-yield Blue Danube core with less fissile material was substituted, reducing the yield to . Titterton and Dwyer were on hand for the shot.

On 11 October 1956,

Kite was an air drop using a Blue Danube device with a low-yield core, the only air drop conducted during Operation Buffalo. Originally the air drop was supposed to be the last test of Operation Buffalo, but after the Marcoo shot Penney decided to swap the last two tests, making the air drop the third test. The air drop was the most difficult test, as the worst-case scenario involved the radar fuses failing and the bomb detonating on impact with the ground, which would result in severe fallout. The RAF therefore conducted a series of practice drops with high explosive bombs. In the end, in view of the AWTSC's concerns about the dangers of a test, a low-yield Blue Danube core with less fissile material was substituted, reducing the yield to . Titterton and Dwyer were on hand for the shot.

On 11 October 1956,

At the AWTSC meeting on 7 December 1956, Martin suggested that the committee be reconstituted. A three-person Maralinga Safety Committee chaired by Titterton, with Dwyer and D. J. Stevens from the Commonwealth X-ray and Radium Laboratory as its other members, would be responsible for the safety of nuclear weapons tests, while a National Radiation Advisory Committee (NRAC) consider public health more generally. This reflected growing disquiet among the scientific community and the public at large over the effects of all atmospheric nuclear weapons testing, not just those in Australia, and growing calls for a test ban. Nonetheless, Operation Buffalo had attracted little international attention. The British Government rejected calls for a moratorium on testing, and announced at the US-UK talks in

At the AWTSC meeting on 7 December 1956, Martin suggested that the committee be reconstituted. A three-person Maralinga Safety Committee chaired by Titterton, with Dwyer and D. J. Stevens from the Commonwealth X-ray and Radium Laboratory as its other members, would be responsible for the safety of nuclear weapons tests, while a National Radiation Advisory Committee (NRAC) consider public health more generally. This reflected growing disquiet among the scientific community and the public at large over the effects of all atmospheric nuclear weapons testing, not just those in Australia, and growing calls for a test ban. Nonetheless, Operation Buffalo had attracted little international attention. The British Government rejected calls for a moratorium on testing, and announced at the US-UK talks in  In July 1957, the Australian Government was informed of the UK authorities' decision to limit Operation Antler to just three tests. There would be two tower tests of and , codenamed Tadje and Biak respectively, and only one balloon test, a test codenamed Taranaki. Helping the Pixie test (which became known as Tadje) remain on the schedule was the deletion of Red Beard tests. It was decided that the third test would be of a Red Beard with a composite uranium-plutonium core, which had not yet been tested, while the pure plutonium Red Beard would go into production without further testing.

Charles Adams was appointed the test director, with J. A. T. Dawson as his deputy, and J. T. Tomblin as the superintendent. Air Commodore W. P. Sutcliffe commanded the services, with Group Captain Hugh Disney in charge of the RAF component. This was by far the largest of the three service components, with 31 aircraft and about 700 men, including a 70-man balloon detachment. Most of the aircraft were based at

In July 1957, the Australian Government was informed of the UK authorities' decision to limit Operation Antler to just three tests. There would be two tower tests of and , codenamed Tadje and Biak respectively, and only one balloon test, a test codenamed Taranaki. Helping the Pixie test (which became known as Tadje) remain on the schedule was the deletion of Red Beard tests. It was decided that the third test would be of a Red Beard with a composite uranium-plutonium core, which had not yet been tested, while the pure plutonium Red Beard would go into production without further testing.

Charles Adams was appointed the test director, with J. A. T. Dawson as his deputy, and J. T. Tomblin as the superintendent. Air Commodore W. P. Sutcliffe commanded the services, with Group Captain Hugh Disney in charge of the RAF component. This was by far the largest of the three service components, with 31 aircraft and about 700 men, including a 70-man balloon detachment. Most of the aircraft were based at

In addition to the major tests, some 550 minor trials were also carried out between 1953 and 1963. These experiments were subcritical tests involving testing of nuclear weapons or their components, but not nuclear explosions. The four series of minor trials were codenamed Kittens, Tims, Rats and Vixens, and involved experiments with plutonium, uranium,

In addition to the major tests, some 550 minor trials were also carried out between 1953 and 1963. These experiments were subcritical tests involving testing of nuclear weapons or their components, but not nuclear explosions. The four series of minor trials were codenamed Kittens, Tims, Rats and Vixens, and involved experiments with plutonium, uranium,

From these tests an improved initiator design emerged that was smaller and simpler, which the scientists were eager to test. A site in the UK would save time and money, although

From these tests an improved initiator design emerged that was smaller and simpler, which the scientists were eager to test. A site in the UK would save time and money, although  Six Kitten tests were carried out at Naya in March 1956. Thereafter, they became a regular part of the testing program, with 21 more tests carried out in 1957, 20 in 1959, and 47 in 1960 and 1961, after which they were discontinued owing to the development of external neutron generators. Kitten experiments at Naya dispersed of polonium-210, of beryllium and of natural and depleted uranium.

Six Kitten tests were carried out at Naya in March 1956. Thereafter, they became a regular part of the testing program, with 21 more tests carried out in 1957, 20 in 1959, and 47 in 1960 and 1961, after which they were discontinued owing to the development of external neutron generators. Kitten experiments at Naya dispersed of polonium-210, of beryllium and of natural and depleted uranium.

Some 31 Vixen A trials were conducted in the Wewak area at Maralinga between 1959 and 1961 that investigated the effects of an accidental fire on a nuclear weapon, and involved a total of about of natural and depleted uranium, 0.98 kg of plutonium of which 0.58 kg was dispersed, of polonium-210 and of

Some 31 Vixen A trials were conducted in the Wewak area at Maralinga between 1959 and 1961 that investigated the effects of an accidental fire on a nuclear weapon, and involved a total of about of natural and depleted uranium, 0.98 kg of plutonium of which 0.58 kg was dispersed, of polonium-210 and of

Maralinga Nuclear Test – 1957 – Movietone Moments

Aerial photo of the Taranaki and Kite test sites

''(Maralinga village & airfield are situated approx 20 miles to the South)''

Maralinga Rehabilitation Project

Backs to the Blast, an Australian Nuclear Story

Australian Atomic Confessions film

{{featured article 1956 establishments in Australia 1963 disestablishments in Australia 1950s in military history 1960s in military history 1950s in South Australia 1960s in South Australia 1950s in the United Kingdom 1960s in the United Kingdom

nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

s at the Maralinga

Maralinga, in the remote western areas of South Australia, was the site, measuring about in area, of British nuclear tests in the mid-1950s.

In January 1985 native title was granted to the Maralinga Tjarutja, a southern Pitjantjatjara Aborigi ...

site in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

, part of the Woomera Prohibited Area

The RAAF Woomera Range Complex (WRC) is a major Australian military and civil aerospace facility and operation located in South Australia, approximately north-west of Adelaide. The WRC is operated by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), a di ...

about north west of Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

. Two major test series were conducted: Operation Buffalo in 1956 and Operation Antler the following year. Approximate weapon yields ranged from . The Maralinga site was also used for minor trials, tests of nuclear weapons components not involving nuclear explosions. Kittens were trials of neutron initiator

A modulated neutron initiator is a neutron source capable of producing a burst of neutrons on activation. It is a crucial part of some nuclear weapons, as its role is to "kick-start" the chain reaction at the optimal moment when the configuration i ...

s; Rats and Tims measured how the fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be typ ...

core

Core or cores may refer to:

Science and technology

* Core (anatomy), everything except the appendages

* Core (manufacturing), used in casting and molding

* Core (optical fiber), the signal-carrying portion of an optical fiber

* Core, the central ...

of a nuclear weapon was compressed by the high explosive shock wave; and Vixens investigated the effects of fire or non-nuclear explosions on atomic weapons. The minor trials, numbering around 550, ultimately generated far more contamination than the major tests.

Operation Buffalo consisted of four tests; One Tree () and Breakaway () were detonated on towers, Marcoo () at ground level, and the Kite () was released by a Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) Vickers Valiant

The Vickers Valiant was a British high-altitude jet bomber designed to carry nuclear weapons, and in the 1950s and 1960s was part of the Royal Air Force's "V bomber" strategic deterrent force. It was developed by Vickers-Armstrongs in response ...

bomber from a height of . This was the first drop of a British nuclear weapon from an aircraft. Operation Antler in 1957 tested new, light-weight nuclear weapons. Three tests were conducted in this series: Tadje (), Biak () and Taranak (). The first two were conducted from towers, while the last was suspended from balloons. Tadje used cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, pr ...

pellets as a tracer for determining yield, resulting in rumours that Britain was developing a cobalt bomb

A cobalt bomb is a type of "salted bomb": a nuclear weapon designed to produce enhanced amounts of radioactive fallout, intended to contaminate a large area with radioactive material, potentially for the purpose of radiological warfare, mutual as ...

.

The site was left contaminated with radioactive waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. Radioactive waste is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, rare-earth mining, and nuclear weapons r ...

, and an initial cleanup was attempted in 1967. The McClelland Royal Commission

The McClelland Royal Commission or Royal Commission into British nuclear tests in Australia was an inquiry by the Australian government in 1984–1985 to investigate the conduct of the British in its use, with the then Australian government's p ...

, an examination of the effects of the minor trials and major tests, delivered its report in 1985, and found that significant radiation hazards still existed at many of the Maralinga sites. It recommended another cleanup, which was completed in 2000 at a cost of AUD

The Australian dollar ( sign: $; code: AUD) is the currency of Australia, including its external territories: Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and Norfolk Island. It is officially used as currency by three independent Pacific Isla ...

$108 million (equivalent to $ in ). Debate continued over the safety of the site and the long-term health effects on the traditional Aboriginal

Aborigine, aborigine or aboriginal may refer to:

*Aborigines (mythology), in Roman mythology

* Indigenous peoples, general term for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area

*One of several groups of indigenous peoples, see ...

custodians of the land and former personnel. In 1994, the Australian Government paid compensation amounting to $13.5 million (equivalent to $ in ) to the traditional owners, the Maralinga Tjarutja

The Maralinga Tjarutja, or Maralinga Tjarutja Council, is the corporation representing the traditional Anangu owners of the remote western areas of South Australia known as the Maralinga Tjarutja lands. The council was established by the ''Mara ...

people. The last part of the land remaining in the Woomera Prohibited Area was returned to free access in 2014.

By the late 1970s there was a marked change in how the Australian media covered the British nuclear tests. Some journalists investigated the subject and political scrutiny became more intense. Journalist Brian Toohey

Brian (sometimes spelled Bryan in English) is a male given name of Irish and Breton origin, as well as a surname of Occitan origin. It is common in the English-speaking world.

It is possible that the name is derived from an Old Celtic word meani ...

ran a series of stories in the ''Australian Financial Review

''The Australian Financial Review'' (abbreviated to the ''AFR'') is an Australian business-focused, compact daily newspaper covering the current business and economic affairs of Australia and the world. The newspaper is based in Sydney, New Sou ...

'' in October 1978, based in part on a leaked Cabinet submission. In June 1993, ''New Scientist

''New Scientist'' is a magazine covering all aspects of science and technology. Based in London, it publishes weekly English-language editions in the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. An editorially separate organisation publishe ...

'' journalist Ian Anderson wrote an article titled "Britain's dirty deeds at Maralinga" and several related articles. In 2007, '' Maralinga: Australia's Nuclear Waste Cover-up'' by Alan Parkinson documented the unsuccessful clean-up at Maralinga. Popular songs about the Maralinga story have been written by Paul Kelly and Midnight Oil

Midnight Oil (known informally as "The Oils") are an Australian rock band composed of Peter Garrett (vocals, harmonica), Rob Hirst (drums), Jim Moginie (guitar, keyboard) and Martin Rotsey (guitar). The group was formed in Sydney in 1972 by ...

.

Background

During the early part of the Second World War, Britain had anuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s project, code-named Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the Bri ...

, which the 1943 Quebec Agreement

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was s ...

merged with the American Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

to create a combined American, British, and Canadian project. The British Government expected that the United States would continue to share nuclear technology, which it regarded as a joint discovery, after the war, but the US Atomic Energy Act of 1946

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) determined how the United States would control and manage the nuclear technology it had jointly developed with its World War II allies, the United Kingdom and Canada. Most significantly, the Act rule ...

(McMahon Act) ended technical co-operation. Fearing a resurgence of United States isolationism

United States non-interventionism primarily refers to the foreign policy that was eventually applied by the United States between the late 18th century and the first half of the 20th century whereby it sought to avoid alliances with other nations ...

, and Britain losing its great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

status, the British Government restarted its own development effort, under the cover name "High Explosive Research

High Explosive Research (HER) was the British project to develop atomic bombs independently after the Second World War. This decision was taken by a cabinet sub-committee on 8 January 1947, in response to apprehension of an American retur ...

".

In the 1950s Britain was still Australia's largest trading partner, although it was overtaken by Japan and the United States by the 1960s. Britain and Australia still had strong cultural ties, and

In the 1950s Britain was still Australia's largest trading partner, although it was overtaken by Japan and the United States by the 1960s. Britain and Australia still had strong cultural ties, and Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

, the Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the Australian Government, federal government of Australia and is also accountable to Parliament of A ...

from 1949 to 1966, was strongly pro-British. Most Australians were of British descent, and Britain was still the largest source of immigrants to Australia, mainly because British ex-servicemen and their families qualified for free passage, and other British migrants received subsidised passage on ships from the UK to Australia. Australian and British troops fought together in the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

from 1950 to 1953 and the Malayan Emergency

The Malayan Emergency, also known as the Anti–British National Liberation War was a guerrilla war fought in British Malaya between communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) and the military forces o ...

that went from 1948 to 1960. Australia still maintained close defence ties with Britain through the Australia New Zealand and Malaya (ANZAM) area, which was created in 1948. Australian war plans of this era continued to be integrated with those of Britain, and involved reinforcing British forces in the Middle East and Far East.

The Australian Government had hopes of collaboration with Britain on both nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced b ...

and nuclear weapons, and was particularly interested in developing the former, as the country was then thought to have no oil and only limited supplies of coal. Plans for nuclear power were considered along with hydroelectricity

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is Electricity generation, electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other Renewabl ...

as part of the post-war Snowy Mountains Scheme

The Snowy Mountains Scheme or Snowy scheme is a hydroelectricity and irrigation complex in south-east Australia. The Scheme consists of sixteen major dams; nine power stations; two pumping stations; and of tunnels, pipelines and aqueducts that ...

, but Australia was not a party to the 1948 ''Modus Vivendi

''Modus vivendi'' (plural ''modi vivendi'') is a Latin phrase that means "mode of living" or " way of life". It often is used to mean an arrangement or agreement that allows conflicting parties to coexist in peace. In science, it is used to descr ...

'', the nuclear agreement between the US and UK which superseded the wartime Quebec Agreement. This cut Australian scientists off from technical information to which they formerly had access. Britain would not share it with Australia for fear that it might jeopardise the far more important relationship with the United States, and the Americans were reluctant to do so after the Venona project

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (later absorbed by the National Security Agency), which ran from February 1, 1943, until Octob ...

revealed the extent of Soviet espionage activities in Australia. The creation of North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO) in 1949 excluded Australia from the Western Alliance.

On 3 October 1952 the United Kingdom tested its first nuclear weapon in Operation Hurricane

Operation Hurricane was the first test of a Nuclear weapons of the United Kingdom, British atomic device. A plutonium Nuclear weapon design#Implosion-type weapon, implosion device was detonated on 3 October 1952 in Main Bay, Trimouille Island ...

in the Montebello Islands

The Montebello Islands, also rendered as the Monte Bello Islands, are an archipelago of around 174 small islands (about 92 of which are named) lying north of Barrow Island (Western Australia), Barrow Island and off the Pilbara region of We ...

off the coast of Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

. A year later the first nuclear tests on the Australian mainland were carried out in Operation Totem

Operation Totem was a pair of British atmospheric nuclear tests which took place at Emu Field in South Australia in October 1953. They followed the Operation Hurricane test of the first British atomic bomb, which had taken place at the Montebell ...

at Emu Field

Emu Field is located in the desert of South Australia, at (ground zero Totem I test). Variously known as Emu Field, Emu Junction or Emu, it was the site of the Operation Totem pair of nuclear tests conducted by the British government in Octobe ...

in the Great Victoria Desert

The Great Victoria Desert is a sparsely populated desert ecoregion and interim Australian bioregion in Western Australia and South Australia.

History

In 1875, British-born Australian explorer Ernest Giles became the first European to cross th ...

in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

, with a detonation on 15 October and a second two weeks later on 27 October. The Australian Minister for Supply, Howard Beale, stated in 1955 that "England has the know how; we have the open spaces, much technical skill and a great willingness to help the Motherland. Between us we should help to build the defences of the free world, and make historic advances in harnessing the forces of nature."

Maralinga site

Selection

Neither the Montebello Islands nor Emu Field were considered suitable as permanent test sites, although Montebello was used again in 1956 forOperation Mosaic

Operation Mosaic was a series of two British nuclear tests conducted in the Monte Bello Islands in Western Australia on 16 May and 19 June 1956. These tests followed the Operation Totem series and preceded the Operation Buffalo series. The sec ...

. Montebello could be accessed only by sea, and Emu Field had problems with its water supply and dust storms. The British Government's preferred permanent test site remained the Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site (N2S2 or NNSS), known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles (105 km) northwest of th ...

in the United States, but by 1953 it was no closer to securing access to it than it had been in 1950. When William Penney

William George Penney, Baron Penney, (24 June 19093 March 1991) was an English mathematician and professor of mathematical physics at the Imperial College London and later the rector of Imperial College London. He had a leading role in the d ...

, the Chief Superintendent Armament Research, visited South Australia in October 1952, he gave the Australian Government a summary of the requirements of a permanent test site. In May 1953, the UK Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Chiefs of Staff Committee (CSC) is composed of the most senior military personnel in the British Armed Forces who advise on operational military matters and the preparation and conduct of military operations. The committee consists of the Ch ...

were advised that one was needed. They delegated the task of finding one to Air Marshal Sir Thomas Elmhirst

Air Marshal Sir Thomas Walker Elmhirst, (15 December 1895 – 6 November 1982), was a senior commander in the Royal Air Force in the first half of the 20th century and the first commander-in-chief of the Royal Indian Air Force upon Indian indepe ...

, the chairman of the Totem Executive (Totex), which had been formed in the UK to coordinate the Operation Totem tests. He wrote to J. E. S. Stevens

Major General Sir Jack Edwin Stawell Stevens, (7 September 1896 – 20 May 1969) was a senior officer in the Australian Army during the Second World War. He was best known as the commanding officer of the 6th Division from 1943 to 1945.

Earl ...

, the permanent secretary

A permanent secretary (also known as a principal secretary) is the most senior Civil Service (United Kingdom), civil servant of a department or Ministry (government department), ministry charged with running the department or ministry's day-to-day ...

of the Australian Department of Supply, and the chairman of the Totem Panel that coordinated the Australian contribution to Operation Totem, and outlined the requirements of a permanent test site, which were:

* A radius free of human habitation;

* Road and rail communications to a port;

* A nearby airport;

* A tolerable climate for staff and visitors;

* Low rainfall;

* Predictable weather conditions;

* Winds that would carry the fallout safely away from inhabited areas; and

* Reasonably flat terrain;

* Isolation for security.

Elmhirst suggested that a site might be found in Groote Eylandt

Groote Eylandt ( Anindilyakwa: ''Ayangkidarrba'' meaning "island" ) is the largest island in the Gulf of Carpentaria and the fourth largest island in Australia. It was named by the explorer Abel Tasman in 1644 and is Dutch for "Large Island" in ...

in the Gulf of Carpentaria

The Gulf of Carpentaria (, ) is a large, shallow sea enclosed on three sides by northern Australia and bounded on the north by the eastern Arafura Sea (the body of water that lies between Australia and New Guinea). The northern boundary is ...

or north of Emu Field, where it could be connected by road and rail to Oodnadatta

Oodnadatta is a small, remote outback town and locality in the Australian state of South Australia, located north-north-west of the state capital of Adelaide by road or direct, at an altitude of . The unsealed Oodnadatta Track, an outback road ...

, and where water could more easily be found than at Emu Field. Stevens rated both as unsuitable; Groote Eylandt was wooded and rocky, with a pronounced rainy season, no port facilities, and a long way from the nearest major settlements of Darwin and Cairns

Cairns (, ) is a city in Queensland, Australia, on the tropical north east coast of Far North Queensland. The population in June 2019 was 153,952, having grown on average 1.02% annually over the preceding five years. The city is the 5th-most-p ...

; while the area north of Emu Field had scarce water, few roads and was on the axis of the Long Range Weapons Establishment

The RAAF Woomera Range Complex (WRC) is a major Australian military and civil aerospace facility and operation located in South Australia, approximately north-west of Adelaide. The WRC is operated by the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), a di ...

(LRWE), which meant that there would be a competing claim on the use of the area. Group Captain

Group captain is a senior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force, where it originated, as well as the air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. It is sometimes used as the English translation of an equivalent rank i ...

George Pither conducted an aerial survey of the area north of the Trans-Australian Railway

The Trans-Australian Railway, opened in 1917, runs from Port Augusta in South Australia to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, crossing the Nullarbor Plain in the process. As the only rail freight corridor between Western Australia and the easter ...

between Ooldea

Ooldea is a tiny settlement in South Australia. It is on the eastern edge of the Nullarbor Plain, west of Port Augusta on the Trans-Australian Railway. Ooldea is from the bitumen Eyre Highway.

Being near a permanent waterhole, Ooldea Soak, th ...

and Cook, South Australia

Cook is a railway station and crossing loop located in the Australian state of South Australia on the Trans-Australian Railway. It is about west by rail from Port Augusta and about north of the Eyre Highway via an unsealed road.(1927)''Trav ...

. This was followed by a ground reconnaissance in four land rover

Land Rover is a British brand of predominantly four-wheel drive, off-road capable vehicles, owned by multinational car manufacturer Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), since 2008 a subsidiary of India's Tata Motors. JLR currently builds Land Rovers ...

s and two four-wheel drive trucks by Pither, Wing Commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr in the RAF, the IAF, and the PAF, WGCDR in the RNZAF and RAAF, formerly sometimes W/C in all services) is a senior commissioned rank in the British Royal Air Force and air forces of many countries which have historical ...

Kevin Connolly, Frank Beavis (an expert in soil chemistry), Len Beadell

Leonard Beadell OAM BEM FIEMS (21 April 1923 – 12 May 1995) was a surveyor, road builder, bushman, artist and author, responsible for constructing over of roads and opening up isolated desert areas – some – of central Australia f ...

and the two truck drivers. An area was found north of Ooldea, and a temporary airstrip was created in two days by land rovers dragging a length of railway line to level it, where Penney, Flight Lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior commissioned rank in air forces that use the Royal Air Force (RAF) system of ranks, especially in Commonwealth countries. It has a NATO rank code of OF-2. Flight lieutenant is abbreviated as Flt Lt in the India ...

Charles Taplin and Chief Scientist Alan Butement landed in a Bristol Freighter

The Bristol Type 170 Freighter is a British twin-engine aircraft designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company as both a freighter and airliner. Its best known use was as an air ferry to carry cars and their passengers over relatively sh ...

on 17 October 1953, two days after the Totem 1 test at Emu Field.

The site, initially known as X.300, was nowhere near as good as the Nevada Test Site, with its excellent communications, but was considered acceptable. It was flat and dry, but not affected by dust storms like Emu Field, and the geologists were confident that the desired per annum could be obtained by boring. Rainwater tanks were recommended, and it was estimated that if

The site, initially known as X.300, was nowhere near as good as the Nevada Test Site, with its excellent communications, but was considered acceptable. It was flat and dry, but not affected by dust storms like Emu Field, and the geologists were confident that the desired per annum could be obtained by boring. Rainwater tanks were recommended, and it was estimated that if bore water

An artesian aquifer is a confined aquifer containing groundwater under positive pressure. An artesian aquifer has trapped water, surrounded by layers of impermeable rock or clay, which apply positive pressure to the water contained within th ...

could not be obtained, a water pipeline could be laid to bring water from Port Augusta

Port Augusta is a small city in South Australia. Formerly a port, seaport, it is now a road traffic and Junction (rail), railway junction city mainly located on the east coast of the Spencer Gulf immediately south of the gulf's head and about ...

. This was estimated to cost AU £53,000 to construct and AU £50,000 per annum to operate. On 25 November, Butement officially named the X.300 site "Maralinga" in a meeting at the Department of Supply. This was an Aboriginal word meaning "thunder", but not in the Western Desert language of the local people; it came from Garik, an extinct language originally spoken around Port Essington

Port Essington is an inlet and historic site located on the Cobourg Peninsula in the Garig Gunak Barlu National Park in Australia's Northern Territory. It was the site of an early attempt at British settlement, but now exists only as a remote ...

in the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (commonly abbreviated as NT; formally the Northern Territory of Australia) is an states and territories of Australia, Australian territory in the central and central northern regions of Australia. The Northern Territory ...

.

On 2 August 1954, the High Commissioner of the United Kingdom to Australia lodged a formal request for a permanent proving ground for multiple series of nuclear tests expected to be conducted over the course of the next decade and a preliminary agreement between the Australian and British Governments was reached on 26 August. A mission consisting of six officials and scientists headed by J. M. Wilson, the under-secretary of the UK Ministry of Supply

The Ministry of Supply (MoS) was a department of the UK government formed in 1939 to co-ordinate the supply of equipment to all three British armed forces, headed by the Minister of Supply. A separate ministry, however, was responsible for aircr ...

(MoS) visited Australia in December to evaluate the Maralinga site, and reported that it was excellent. The new site was officially announced by Beale on 4 April 1955, and the Australian Cabinet

The Cabinet of Australia (or Federal Cabinet) is the chief decision-making organ of the executive branch of the government of Australia. It is a council of senior government ministers, ultimately responsible to the Federal Parliament.

Minister ...

gave its assent on 4 May. A formal Memorandum of Arrangements for use of Maralinga was signed on 7 March 1956. It specified that the site would be available for ten years; that no thermonuclear tests would be carried out; that the British Government would be liable for all claims of death or injury to people or damage to property as a result of the tests, except those to British Government personnel; that Australian concurrence would be required before any test could be carried out; and that the Australian authorities would be kept fully informed.

Maralinga was to be developed as a joint facility, co-funded by the British and Australian Governments. The range covered , with a test area. With savings arising from the relocation of buildings, stores and equipment from Emu Field taken into account, the cost of developing Maralinga as a permanent site was estimated to cost AU £1.9 million, compared with AU £3.6 million for Emu Field. The British Government welcomed Australian financial assistance, and Australian participation avoided the embarrassment that would have come from building a UK base on Australian soil. On the other hand, it was recognised that Australian participation would likely mean that the Australians would demand access to even more information than in Operation Totem. This had implications for Britain's relationship with the United States. Sharing information with the Australians would make it harder to secure Britain's ultimate goal, of restoring the wartime nuclear Special Relationship

The Special Relationship is a term that is often used to describe the politics, political, social, diplomacy, diplomatic, culture, cultural, economics, economic, law, legal, Biophysical environment, environmental, religion, religious, military ...

with the United States, and gaining access to information pertaining to the design and manufacture of US nuclear weapons.

Development

A railhead and a quarry were established at

A railhead and a quarry were established at Watson

Watson may refer to:

Companies

* Actavis, a pharmaceutical company formerly known as Watson Pharmaceuticals

* A.S. Watson Group, retail division of Hutchison Whampoa

* Thomas J. Watson Research Center, IBM research center

* Watson Systems, make ...

, about west of Ooldea, and Beadell's bush track from Watson to Emu became the main line of communications

A line of communication (or communications) is the route that connects an operating military unit with its supply base. Supplies and reinforcements are transported along the line of communication. Therefore, a secure and open line of communicat ...

for the project. It ran north to the edge of the Nullarbor Plain

The Nullarbor Plain ( ; Latin: feminine of , 'no', and , 'tree') is part of the area of flat, almost treeless, arid or semi-arid country of southern Australia, located on the Great Australian Bight coast with the Great Victoria Desert to its ...

, then over sand hills and the Leisler Range, a mallee, spinifex and quandong

Quandong, quandang or quondong, is a common name for the species ''Santalum acuminatum'' (desert, sweet, Western quandong), especially its edible fruit, but may also refer to

* '' Aceratium concinnum'' (highroot quandong)

* '' Peripentadenia mear ...

covered escarpment, rising to an altitude of . Range headquarters, known as The Village, and an airstrip with a runway were built near the peg. The track continued north over scrub-cover sand hills to the Teitkins Plain. There at a point that came to be known as Roadside, a control point was established for entry to the forward area where bombs were detonated.

The UK MoS engaged a firm of British engineering consultants, Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners

Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners was a British firm of consulting civil engineers, based at Queen Anne's Lodge, Queen Anne's Gate and subsequently Telford House, Tothill Street, Westminster, London, until 1974, when it relocated to Earley House, 427 ...

, to design the test facilities and supervise their construction. The work was carried out by the Kwinana Construction Group (KCG) under a cost-plus contract

A cost-plus contract, also termed a cost plus contract, is a contract such that a contractor is paid for all of its allowed expenses, ''plus'' additional payment to allow for a profit.Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia, located at the mouth of the Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australian vernacular diminutive for ...

, and it was hoped that it could move on to the new venture immediately, but the delay in obtaining Cabinet's approval meant that work could not start until mid-1955, by which time most of its work force had dispersed. The need to create a new work force caused a cascading series of delays. Assembling a labour force of 1,000 from scratch in such a remote location proved difficult, even when KCG was offering wages as high as AU £40 a week ().

The Australian Government elected to create a tri-service task force to construct the test installations. The Australian Army's Engineer in Chief, Brigadier

Brigadier is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several thousand soldiers. In ...

Ronald McNicoll

Major General Ronald Ramsay McNicoll, (15 September 1906 – 18 September 1996) was an Australian Army general who served in the Royal Australian Engineers.

Early life

Born on 15 September 1906 in Melbourne, Victoria, McNicoll was the son of ...

designated Major Owen Magee, the Commander, Royal Australian Engineers

The Royal Australian Engineers (RAE) is the military engineering corps of the Australian Army (although the word corps does not appear in their name or on their badge). The RAE is ranked fourth in seniority of the corps of the Australian Army, be ...

, Western Command, to lead this task force. He joined a party headed by Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

John Blomfield, the MoS Atomic Weapons representative in Australia, on a site inspection, and then flew to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment

The Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) is a United Kingdom Ministry of Defence research facility responsible for the design, manufacture and support of warheads for the UK's nuclear weapons. It is the successor to the Atomic Weapons Research ...

(AWRE) at Aldermaston

Aldermaston is a village and civil parish in Berkshire, England. In the 2011 Census, the parish had a population of 1015. The village is in the Kennet Valley and bounds Hampshire to the south. It is approximately from Newbury, Basingstoke ...

in the UK in a Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) Handley Page Hastings

The Handley Page HP.67 Hastings is a retired British troop-carrier and freight transport aircraft designed and manufactured by aviation company Handley Page for the Royal Air Force (RAF). Upon its introduction to service during September 1948, ...

to review the plans. These were still incomplete, but it gave Magee sufficient information to prepare estimates of the labour and equipment that would be required. The job involved the erection of towers, siting of instrument mounts, grading of of tracks, laying control cables and power lines, and construction of bunkers and other facilities dispersed over an area of but sited to within an accuracy of . The work force could not be fully assembled before 1 March 1956, but the facilities had to be ready for use by the end of July. provided Bloomfield with a list of required stores and equipment. These ranged from timber and nails to drafting gear and two wagon drills.

The task force, which began assembling in February 1956, included a section from the

The task force, which began assembling in February 1956, included a section from the Royal Australian Survey Corps

The Royal Australian Survey Corps (RA Svy) was a Corps of the Australian Army, formed on 1 July 1915 and disbanded on 1 July 1996. As one of the principal military survey units in Australia, the role of the Royal Australian Survey Corps was to pro ...

, a troop of the 7th Field Squadron, detachments from the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), and a civilian from the Department of Works and Housing

The Department of Works and Housing was an Australian government department that existed between July 1945 and June 1952.

Scope

Information about the department's functions and/or government funding allocation could be found in the Ad ...

. Their first task was establishing their own camp, with tents, showers and toilets. A team from the South Australian Department of Mines sank a series of bores to provide water. Like that at Emu Field, the bore water was brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuari ...

. Two Army skid-mounted Cleaver-Brooks thermocompression

Vapor-compression evaporation is the evaporation method by which a blower, compressor or jet ejector is used to compress, and thus, increase the pressure of the vapor produced. Since the pressure increase of the vapor also generates an increase i ...

distillation units provided water for drinking and cooking. Work on the facilities themselves got off to a slow start, as KCG was running behind schedule, and unable to release promised earthmoving plant. Some grader

A grader, also commonly referred to as a road grader, motor grader, or simply a blade, is a form of heavy equipment with a long blade used to create a flat surface during grading. Although the earliest models were towed behind horses, and lat ...

s were used by day by KCG and by night by the task force. A call to Blomfield resulted in a grader being shipped from Adelaide to Watson two days later. The arrival of a 23-man detachment of the Radiation Detection Unit of the Corps of Royal Canadian Engineers

The Canadian Military Engineers (CME; french: links=no, Génie militaire canadien) is the military engineering personnel branch of the Canadian Armed Forces. The members of the branch that wear army uniform comprise the Corps of Royal Canadian Engi ...

was expedited so they arrived in June, and were able to pitch in with the construction effort. In July, supplies coming from the UK were delayed by industrial action at the port of Adelaide.

The work involved laying, testing and burying some of control cable. Each spool of cable weighed about , so where possible they were pre-positioned. The trenches were dug by a cable plough towed by a Caterpillar D8

The Caterpillar D8 is a medium tracked vehicle, track-type tractor designed and manufactured by Caterpillar Inc., Caterpillar. Though it comes in many configurations, it is usually sold as a bulldozer equipped with a detachable large blade and a ...

tractor. In some cases the limestone was too hard for the plough and the cable was buried by using a grader to cover the cable to the required depth. A similar procedure was followed for laying of power cable. Some 1,300 scaffold frames were erected for mounting instrumentation, held in place by 33,000 anchor pipes. Bunkers ranging in size up to were excavated with explosives and a compressor mounted on a four-wheel drive 3-ton Bedford truck connected to the jackhammer

A jackhammer (pneumatic drill or demolition hammer in British English) is a pneumatic or electro-mechanical tool that combines a hammer directly with a chisel. It was invented by William Mcreavy, who then sold the patent to Charles Brady Kin ...

part of the 4-inch wagon drill. Explosives were in the form of tubes of plastic explosive

Plastic explosive is a soft and hand-moldable solid form of explosive material. Within the field of explosives engineering, plastic explosives are also known as putty explosives

or blastics.

Plastic explosives are especially suited for explos ...

left over from a Bureau of Mineral Resources

Geoscience Australia is an agency of the Australian Government. It carries out geoscientific research. The agency is the government's technical adviser on all aspects of geoscience, and custodian of the geographic and geological data and knowl ...

seismic survey of the area. The bunker work proceeded so well that the task force was able to assist KCG with its pit excavation work. Some instrument bunkers contained steel cubes. Getting them into the holes was tricky because they weighed , and the largest available crane was a Coles crane. They were manoeuvred into place with the assistance of a TD 24 bulldozer. The Coles crane was also used to erect the two shot towers. Concrete was made ''in situ'', using local quarry dust, limestone and bore water. The Canadians erected metal sheds of a commercial design, which were used to assess blast damage. A tented camp was built for observers at the post by the 23rd Construction Squadron.

Pressed for time, Magee became involved in a series of disputes with the Woomera Range commander, who tried to divert his sappers onto other tasks. In June, the range commander ordered the surveyors to return to Adelaide, which would have brought the work at Maralinga to a halt. Magee went over his head and appealed to the commander of Central Command,

Pressed for time, Magee became involved in a series of disputes with the Woomera Range commander, who tried to divert his sappers onto other tasks. In June, the range commander ordered the surveyors to return to Adelaide, which would have brought the work at Maralinga to a halt. Magee went over his head and appealed to the commander of Central Command, Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Arthur Wilson, who flew up from Adelaide and sacked the range commander. Impressed by what he saw at Maralinga, Wilson arranged for the task force to receive a special Maralinga allowance of 16 Australian shillings per day (), and additional leave of two days per month. The British Government added a generous meal allowance of GBP

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of its associated territories. The pound ( sign: £) is the main unit of sterling, and t ...

£1 () per day, resulting in a diet of steak, ham, turkey, oysters and crayfish. In June, Beale flew in two planeloads of journalists, including Chapman Pincher

Henry Chapman Pincher (29 March 1914 – 5 August 2014) was an English journalist, historian and novelist whose writing mainly focused on espionage and related matters, after some early books on scientific subjects.

Early life

Pincher was born ...

and Hugh Buggy

Edward Hugh Buggy (9 June 1896 – 18 June 1974) was a leading journalist well known as an Australian rules football writer covering the Victorian Football League (renamed in 1989 Australian Football League).

Born at Seymour, Victoria in 1896, B ...

for a press conference. The task force completed all its work on 29 July, two days ahead of schedule, although KCG still had a few remaining tasks.

By 1959, the Maralinga village would have accommodation for 750 people, with catering facilities that could cope with up to 1,600. There were laboratories and workshops, shops, a hospital, church, power station, post office, bank, library, cinema and swimming pool. There were also playing areas for tennis, Australian football, cricket and golf.

Atomic Weapons Tests Safety Committee

Leslie Martin

Sir John Leslie Martin (17 August 1908, in Manchester – 28 July 2000) was an English architect, and a leading advocate of the International Style. Martin's most famous building is the Royal Festival Hall. His work was especially influenced ...

, the scientific adviser at the Department of Defence Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philipp ...

, could see no issues with the proposed tests, but recommended that in view of the prospect of tests being conducted at Maralinga on a regular basis, and rising concern worldwide over radioactive fallout from nuclear tests, that a permanent body be established to certify the safety of the tests. This was accepted, and the acting secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Frederick Chilton

Dr. Frederick Chilton is a fictional character appearing in Thomas Harris' novels '' Red Dragon'' (1981) and '' The Silence of the Lambs'' (1988), along with the film and television adaptations of Harris's novels.

In the novels

''Red Dragon''

...

, put forward the names of five scientists: Butement; Martin; Ernest Titterton

Sir Ernest William Titterton (4 March 1916 – 8 February 1990) was a British nuclear physicist.

A graduate of the University of Birmingham, Titterton worked in a research position under Mark Oliphant, who recruited him to work on radar ...

from the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

in Canberra; Philip Baxter

Sir John Philip Baxter (7 May 1905 – 5 September 1989) was a British chemical engineer. He was the second director of the University of New South Wales from 1953, continuing as vice-chancellor when the position's title was changed in 1955. Un ...

from the Australian Atomic Energy Commission

The Australian Atomic Energy Commission (AAEC) was a statutory body of the Australian government.

It was established in 1952, replacing the Atomic Energy Policy Committee. In 1981 parts of the Commission were split off to become part of CSIRO, t ...

; and Cecil Eddy from the Commonwealth X-ray and Radium Laboratory. Butement, Martin and Titterton had already been observers at the Operation Mosaic and Operation Totem tests. The Department of Defence favoured a committee of three, but Menzies felt that such a small committee would not command sufficient public confidence, and accepted all five. A notable omission was the lack of a meteorologist, and Leonard Dwyer, the director of the Bureau of Meteorology

The Bureau of Meteorology (BOM or BoM) is an executive agency of the Australian Government responsible for providing weather services to Australia and surrounding areas. It was established in 1906 under the Meteorology Act, and brought together ...

was later added. The Atomic Weapons Tests Safety Committee (AWTSC) was officially formed on 21 July 1955.

Aboriginal affairs

Menzies told parliament that "no conceivable injury to life, men or property could emerge from the tests". The Maralinga site was inhabited by thePitjantjatjara

The Pitjantjatjara (; or ) are an Aboriginal people of the Central Australian desert near Uluru. They are closely related to the Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra and their languages are, to a large extent, mutually intelligible (all are vari ...

and Yankunytjatjara

The Yankunytjatjara people, also written Yankuntjatjarra, Jangkundjara, and other variants, are an Aboriginal Australian people of the state of South Australia.

Language

Yankunytjatjara is a Western Desert language belonging to the Wati lan ...

Aboriginal

Aborigine, aborigine or aboriginal may refer to:

*Aborigines (mythology), in Roman mythology

* Indigenous peoples, general term for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area

*One of several groups of indigenous peoples, see ...

people, for whom it had a great spiritual significance. They lived through hunting and gathering activities, and moved over long distances between permanent and semi-permanent locations in groups of about 25, but coming together for special occasions. The construction of the Trans-Australian Railway in 1917 had disrupted their traditional patterns of movement. Walter MacDougall

Walter Batchelor MacDougall (6 April 1907 – 5 May 1976) was an Australian missionary and patrol officer who worked with the indigenous peoples in the desert regions of Western Australia and South Australia

Biography

MacDougall was born in Morni ...

had been appointed the Native Patrol Officer at Woomera on 4 November 1947, with responsibility for ensuring that Aboriginal people were not harmed by the LRWE's rocket testing program. He was initially assigned to the Department of Works and Housing but was transferred to the Department of Supply in May 1949. As the range of the rockets increased, so too did the range of his patrols, from in October 1949 to in March and April 1952. MacDougall felt that his situation was not appreciated by his superiors, who did not supply him with a vehicle for his own use for three years.

MacDougall estimated that about 1,000 Aboriginal people lived in the Central Australian reserve, which extended to the border with Western Australia. He found them reluctant to reveal important details such as the location of water holes and sacred sites

Sacred space, sacred ground, sacred place, sacred temple, holy ground, or holy place refers to a location which is deemed to be sacred or hallowed. The sacredness of a natural feature may accrue through tradition or be granted through a bless ...

. His first concern was for their safety, and for that he needed to keep them away from the test site. For this he employed three strategies. The first was to remove the incentive to go there. An important lure was the availability of rations at Ooldea and surrounding missions, so he had them closed. The Ooldea mission was closed in June 1952, and the reserve was revoked in February 1954. The inhabitants were moved to a new settlement at Yalata

Yalata is an Aboriginal community located west of Ceduna and south of Ooldea on the edge of the Nullarbor Plain in South Australia. It lies on the traditional lands of the Wirangu people, but the settlement began as Yalata Mission in the ea ...

, but many ritual objects had been concealed and left behind. They preferred the landscape of the desert, and many left Yalata to return to their traditional lands. A more successful tactic was to frighten them. The desert was said to be inhabited by wanampi, dangerous rainbow serpent spirits that lived in blowholes in the area. The noise of the nuclear tests was attributed to wanampi, as were the dangers of radiation. The decision to establish the Giles Weather Station

Giles Weather Station (also referred to as Giles Meteorological Station or Giles) is located in Western Australia near the Northern Territory border, about west-south-west of Alice Springs and west of Uluru. It is the only staffed weather sta ...

in the Rawlinson Ranges

Purli Yurliya or Rawlinson Ranges is a mountain range in the far east of central Western Australia, to the west of the Petermann Ranges, with which it is commonly associated. Both features were given their European names by Ernest Giles, the fir ...

was a complicating factor because it was outside MacDougall's jurisdiction, being just across the border in Western Australia, where the legal environment was different, and the Aboriginal people there had little contact with white people. Another patrol officer position was created, one with powers under the 1954 Western Australian Native Welfare Act, which was filled by a Sydney University

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's six ...

graduate, Robert Macaulay.

Operation Buffalo

Planning and purpose

Operation Buffalo was the first nuclear test series to be conducted at Maralinga, and the largest ever held in Australia. Planning for the series, initially codenamed Theta, began in mid-1954. It was initially scheduled for April and May 1956, but was pushed back to September and October, when meteorological conditions were most favourable. Ultimately all tests on the Australian mainland were conducted at this time of year. The 1954 plan for Operation Theta called for four tests, each with a different purpose. The UK's first nuclear weapon, Blue Danube, was large and cumbersome, being long and wide, and weighed , so only the Royal Air Force (RAF)V-bombers

The "V bombers" were the Royal Air Force (RAF) aircraft during the 1950s and 1960s that comprised the United Kingdom's strategic nuclear strike force known officially as the V force or Bomber Command Main Force. The three models of strategic ...

could carry it. In November 1953, the RAF and Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

issued an Operational Requirement

An Operational Requirement, commonly abbreviated OR, was a United Kingdom (UK) Air Ministry document setting out the required characteristics for a future (i.e., as-yet unbuilt) military aircraft or weapon system.

The numbered OR would describe ...

, OR.1127, for a smaller, lighter weapon with similar yield that could be carried by tactical aircraft. A second requirement for a light-weight bomb arose with the British Government's decision in July 1954 to proceed with a British hydrogen bomb programme

The British hydrogen bomb programme was the ultimately successful British effort to develop hydrogen bombs between 1952 and 1958.

During the early part of the Second World War, Britain had a nuclear weapons project, codenamed Tube Alloys. At th ...

. Hydrogen bombs required an atomic bomb as a primary, and one was incorporated in the British hydrogen bomb design, known as Green Granite

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 Nanometre, nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by ...

.

In response, Aldermaston developed a new warhead called Red Beard

is a 1965 Japanese ''jidaigeki'' film co-written, edited, and directed by Akira Kurosawa, in his last collaboration with actor Toshiro Mifune. Based on Shūgorō Yamamoto's 1959 short story collection, '' Akahige Shinryōtan'', the film takes pl ...

that was half the size of Blue Danube and weighed one-fifth as much, mainly through innovation in the pit

Pit or PIT may refer to:

Structure

* Ball pit, a recreation structure

* Casino pit, the part of a casino which holds gaming tables

* Trapping pit, pits used for hunting

* Pit (motor racing), an area of a racetrack where pit stops are conducted

* ...

design, principally the use of an "air lens". Instead of the core being immediately inside the tamper, there was an air gap between them, with the core suspended on thin wires. This allowed the tamper to gain more momentum before striking the core. The concept had been developed by the Manhattan Project in 1945 and 1946, and permitted a reduction in both the size of the core and the amount of explosives required to compress it.

The first test on the agenda was therefore of the new Red Beard design. OR.1127 also specified a requirement for the device to have variable yields, which Aldermaston attempted to achieve through the addition of small amounts of thermonuclear material, a process known as "boosting". A tower was built at Maralinga for a boosted weapon test in case sufficient lithium deuteride

Lithium hydride is an inorganic compound with the formula Li H. This alkali metal hydride is a colorless solid, although commercial samples are grey. Characteristic of a salt-like (ionic) hydride, it has a high melting point, and it is not solub ...

could not be produced in time for the Operation Mosaic G2 test. In the event, it was available, and G2 went ahead as scheduled. Various tests of the effects of nuclear weapons were considered, but only one thought to be worth the effort was a test of a ground burst. These were known to produce more fallout and less effect than air bursts, and had therefore been avoided by the Americans, but such a test might produce useful information that the UK might trade with them. A ground test was therefore included in the schedule. A fourth test was an operational test. While the physics package of Blue Danube had been tested, there had been no test of the device in its operational form, so one was included in the Operation Buffalo program.

The interdepartmental Atomic Trials Executive in London, chaired by Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Sir Frederick Morgan, assumed responsibility for both Operation Mosaic and Operation Buffalo, sitting as the Mosaic Executive (Mosex) or Buffalo Executive (Buffalex) as appropriate. Sir William Penney was appointed scientific director for Operation Buffalo, with Roy Pilgrim, the head of Aldermaston's Trials Division, as his deputy. Group Captain Cecil (Ginger) Weir was appointed Task Force Commander. Planning was completed by June 1956. Except for the air drop, all tests were scheduled for 07:00 Central Standard Time

The North American Central Time Zone (CT) is a time zone in parts of Canada, the United States, Mexico, Central America, some Caribbean Islands, and part of the Eastern Pacific Ocean.

Central Standard Time (CST) is six hours behind Coordinate ...

. About 1,350 personnel would be present, including 200 scientists from Aldermaston and Harwell, 70 from other UK departments, 50 Canadians and 30 Australians. There would be 500 RAF and RAAF personnel, and 250 Australian Army servicemen to run the camp. Observers would include politicians, journalists, and six American officials, including Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Leland S. Stranathan from the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project

The Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP) was a United States military agency responsible for those aspects of nuclear weapons remaining under military control after the Manhattan Project was succeeded by the Atomic Energy Commission on ...

, Alvin C. Graves

Alvin Cushman Graves (November 4, 1909 – July 28, 1965) was an American nuclear physicist who served at the Manhattan Project's Metallurgical Laboratory and the Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. After the war, he became the head of ...

from the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, in ...

, Frank H. Shelton from Sandia Laboratories

Sandia National Laboratories (SNL), also known as Sandia, is one of three research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy's National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). Headquartered in Kirtland Air Force Bas ...

and Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

John G. Shinkle from the White Sands Missile Range

White Sands Missile Range (WSMR) is a United States Army military testing area and firing range located in the US state of New Mexico. The range was originally established as the White Sands Proving Ground on 9July 1945. White Sands National P ...

.

Test 1: One Tree

The first test, codenamed One Tree, was a tower-mounted test of

The first test, codenamed One Tree, was a tower-mounted test of Red Beard

is a 1965 Japanese ''jidaigeki'' film co-written, edited, and directed by Akira Kurosawa, in his last collaboration with actor Toshiro Mifune. Based on Shūgorō Yamamoto's 1959 short story collection, '' Akahige Shinryōtan'', the film takes pl ...

, scheduled for 12 September. This was the main test to which the media were invited. Butement, Dwyer, Martin and Titterton from the AWTSC were present, and Beale arrived from Canberra with a delegation of 26 politicians, but weather conditions were unfavourable, and the test had to be postponed.

The schedule was revised to allow for a morning (07:00) or evening (17:00) test, and after a few days of unfavourable weather it was rescheduled for 23 September. Once again the politicians arrived but returned disappointed. This put Penney under great pressure. On the one hand, if Maralinga was to be used for many years then riding roughshod over Australian concerns about safety at an early date was inadvisable; on the other, there was the urgent need to test Red Beard in time for the upcoming

The schedule was revised to allow for a morning (07:00) or evening (17:00) test, and after a few days of unfavourable weather it was rescheduled for 23 September. Once again the politicians arrived but returned disappointed. This put Penney under great pressure. On the one hand, if Maralinga was to be used for many years then riding roughshod over Australian concerns about safety at an early date was inadvisable; on the other, there was the urgent need to test Red Beard in time for the upcoming Operation Grapple

Operation Grapple was a set of four series of British nuclear weapons tests of early atomic bombs and hydrogen bombs carried out in 1957 and 1958 at Malden Island and Kiritimati (Christmas Island) in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands in the Paci ...

, the test of a British hydrogen bomb. Whether Buffalo or Grapple was more important was the subject of debate in the UK between Willis Jackson, who argued for Buffalo, and Bill Cook

William Osser Xavier Cook (October 8, 1895 – May 5, 1986) was a Canadian professional ice hockey right winger who played for the Saskatoon Crescents of the Western Canada Hockey League (WCHL) and the New York Rangers of the National Hockey Le ...

, who argued for Grapple. Jackson's view prevailed; Grapple would be postponed if need be.