Lucas, Archbishop of Esztergom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lucas ( hu, Lukács; 1120 – 1181), also known as Luke, was a Hungarian

Initially, Géza II supported the efforts of

Initially, Géza II supported the efforts of

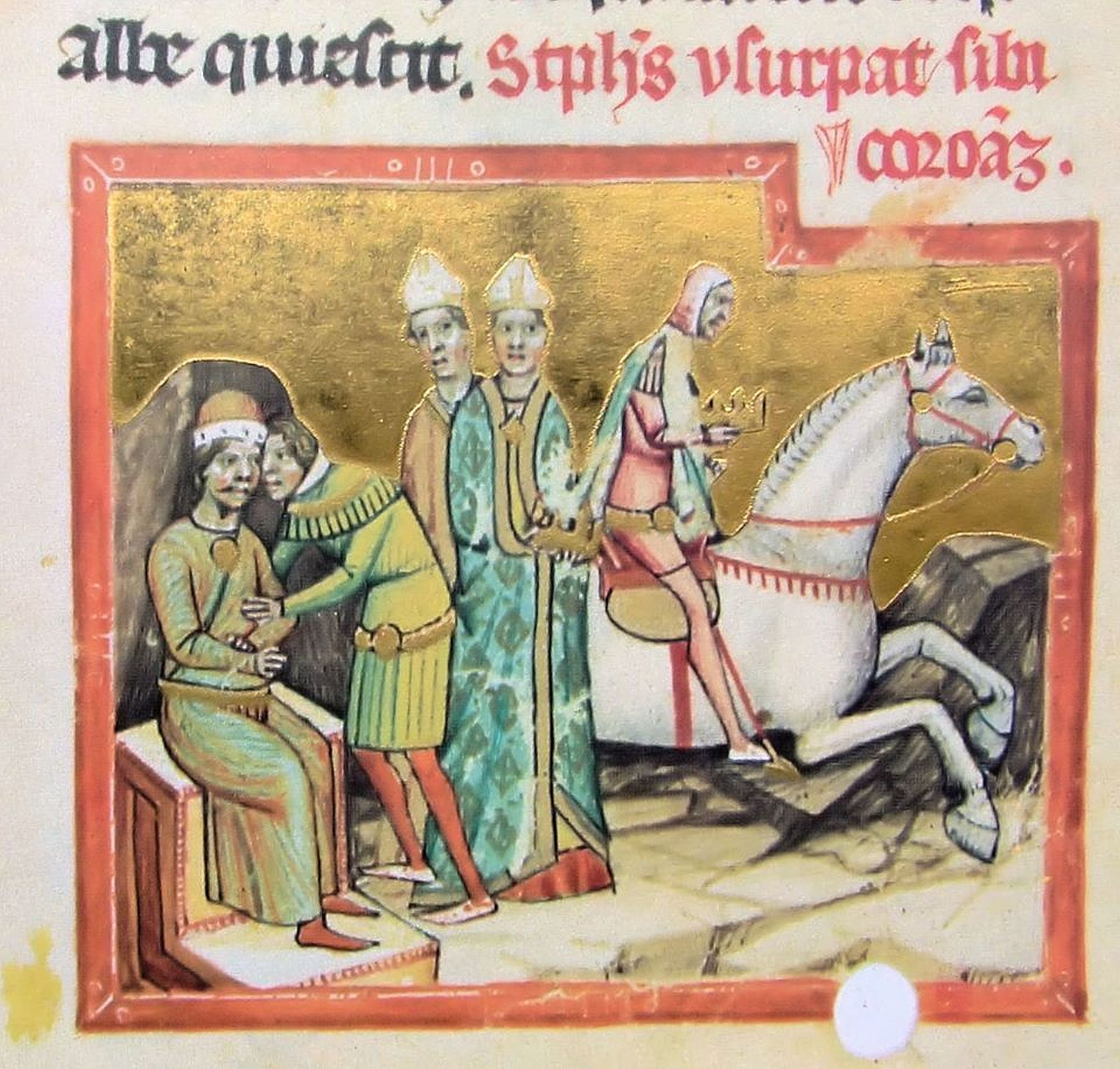

Géza II died unexpectedly on 31 May 1162. Archbishop Lucas crowned Géza II's elder son, 15-year-old Stephen III king without delay in early June in

Géza II died unexpectedly on 31 May 1162. Archbishop Lucas crowned Géza II's elder son, 15-year-old Stephen III king without delay in early June in  Ladislaus II attempted to reconcile himself with his opponents and released Archbishop Lucas at Christmas at Pope Alexander III's request. Map preserved the circumstances of his release (see above). However, Lucas did not yield to him, continued to support Stephen III, and became a central figure of Ladislaus' domestic opposition. His obstinate resistance indicated that any possibility of a reconciliation between the partisans of Stephen III and Ladislaus II was lost. Lucas did not recognize the legitimacy of Ladislaus' rule and organised the possibility of an open rebellion against the pro-Byzantine regime. Lucas' political interests conflicted with Pope Alexander's, who maintained a moderately good relationship with the courts of Ladislaus II and Emperor Manuel on account of the constant threat of Barbarossa's anti-papal policy. Church historian József Török argues Lucas saw the consistent and exclusive application of the ancient custom of

Ladislaus II attempted to reconcile himself with his opponents and released Archbishop Lucas at Christmas at Pope Alexander III's request. Map preserved the circumstances of his release (see above). However, Lucas did not yield to him, continued to support Stephen III, and became a central figure of Ladislaus' domestic opposition. His obstinate resistance indicated that any possibility of a reconciliation between the partisans of Stephen III and Ladislaus II was lost. Lucas did not recognize the legitimacy of Ladislaus' rule and organised the possibility of an open rebellion against the pro-Byzantine regime. Lucas' political interests conflicted with Pope Alexander's, who maintained a moderately good relationship with the courts of Ladislaus II and Emperor Manuel on account of the constant threat of Barbarossa's anti-papal policy. Church historian József Török argues Lucas saw the consistent and exclusive application of the ancient custom of

During the war with the Byzantine Empire, Stephen III sought assistance from Emperor Frederick, Pope Alexander's enemy. The alliance, despite its reasonable military considerations, was strongly opposed by Lucas and the pope, who requested Lucas via Archbishop Eberhard of Salzburg to prevent Stephen III from seeking military help from the Holy Roman Empire. Pope Alexander, additionally, complained that

During the war with the Byzantine Empire, Stephen III sought assistance from Emperor Frederick, Pope Alexander's enemy. The alliance, despite its reasonable military considerations, was strongly opposed by Lucas and the pope, who requested Lucas via Archbishop Eberhard of Salzburg to prevent Stephen III from seeking military help from the Holy Roman Empire. Pope Alexander, additionally, complained that

Lucas became a member of the internal opposition which rejected Béla's reign. The archbishop allied with his former opponent Queen Euphrosyne and supported the aspirations of the late Géza II's youngest son,

Lucas became a member of the internal opposition which rejected Béla's reign. The archbishop allied with his former opponent Queen Euphrosyne and supported the aspirations of the late Géza II's youngest son,

prelate

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Christian clergy who is an ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which means 'carry before', 'be set above or over' or 'pref ...

and diplomat in the 12th century. He was Bishop of Eger

The Archdiocese of Eger ( la, Archidioecesis Agriensis) is an archdiocese in Northern Hungary, its centre is the city of Eger.

History

* 1000: Established as Diocese of Eger

* August 9, 1804: Promoted as Metropolitan Archdiocese of Eger

Ordi ...

between 1156 and 1158, and Archbishop of Esztergom

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdioc ...

from 1158 until his death in 1181.

Lucas is believed to have come from a wealthy and influential family, but sources are uncertain of his origin. He was one of the first students of the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

. When he returned to Hungary, his ecclesiastical career ascended quickly into the highest dignities. As a confidant of Géza II Géza is a Hungarian given name and may refer to any of the following:

* Benjamin Géza Affleck

* Géza, Grand Prince of the Hungarians

* Géza I of Hungary, King of Hungary

* Géza II of Hungary, King of Hungary

* Géza, son of Géza II of Hungar ...

in his last years, Lucas had a significant impact on the country's foreign policy and diplomatic processes. Lucas was a staunch supporter of Stephen III during the struggles in the Árpád dynasty

The Árpád dynasty, consisted of the members of the royal House of Árpád (), also known as Árpáds ( hu, Árpádok, hr, Arpadovići). They were the ruling dynasty of the Principality of Hungary in the 9th and 10th centuries and of the Kingd ...

following Géza II's death, where Stephen III's reign was contested by his two uncles. The archbishop opposed both the intervention efforts of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

. Lucas had an ambivalent relationship with Stephen's brother and successor Béla III

Béla may refer to:

* Béla (crater), an elongated lunar crater

* Béla (given name), a common Hungarian male given name

See also

* Bela (disambiguation)

* Belá (disambiguation)

* Bělá (disambiguation) Bělá, derived from ''bílá'' (''whit ...

. The strict and uncompromising nature of his extremist Gregorianism challenged and weakened his partnership and alliance with the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

in the last decade of his archiepiscopal tenure, which coincided with the pontificate

The pontificate is the form of government used in Vatican City. The word came to English from French and simply means ''papacy'', or "to perform the functions of the Pope or other high official in the Church". Since there is only one bishop of Ro ...

of Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland ( it, Rolando), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a con ...

.

Ancestry

Lucas is said to have been born to a wealthy and illustrious noble family in the early 1120s, but his origin is uncertain and undetermined. His brother was Apa (or Appa), a powerful lord in the royal court ofGéza II of Hungary

Géza II ( hu, II. Géza; hr, Gejza II; sk, Gejza II; 113031 May 1162) was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1141 to 1162. He was the oldest son of Béla the Blind and his wife, Helena of Serbia. When his father died, Géza was still a child a ...

. Apa came into prominence after the fall of Beloš

Beloš ( sr-cyr, Белош; hu, Belos or ''Belus''; el, Βελούσης fl. 1141–1163), was a Serbian prince and Hungarian palatine who served as the regent of Hungary from 1141 until 1146, alongside his sister Helena, mother of the infan ...

, and served as the ''ispán

The ispánRady 2000, p. 19.''Stephen Werbőczy: The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517)'', p. 450. or countEngel 2001, p. 40.Curta 2006, p. 355. ( hu, ispán, la, comes or comes parochialis, and sk, župan)Kirs ...

'' of Bodrog County

The Bodrog is a river in eastern Slovakia and north-eastern Hungary. It is a tributary to the river Tisza. The Bodrog is formed by the confluence of the rivers Ondava and Latorica near Zemplín in eastern Slovakia. It crosses the Slovak–Hun ...

in 1156 and then as the Ban of Slavonia

Ban of Slavonia ( hr, Slavonski ban; hu, szlavón bán; la, Sclavoniæ banus) or the Ban of "Whole Slavonia" ( hr, ban cijele Slavonije; hu, egész Szlavónia bánja; la, totius Sclavoniæ banus) was the title of the governor of a territor ...

from around 1157 to 1158. According to an inauthentic charter he was also Judge royal

The judge royal, also justiciar,Rady 2000, p. 49. chief justiceSegeš 2002, p. 202. or Lord Chief JusticeFallenbüchl 1988, p. 145. (german: Oberster Landesrichter,Fallenbüchl 1988, p. 72. hu, országbíró,Zsoldos 2011, p. 26. sk, krajinsk� ...

in 1158.

From the 18th century onwards, several historians and genealogists attempted to connect Lucas and his brother Apa to various notable ''genera'' (clans) in the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

. András Lehotzky and Iván Nagy proposed that Lucas was a member of the Bánfi (Bánffy; lit. "son of a ban") de Alsólendva family, originating from the Hahót clan, while other historians proposed he descended from the Bánfi (Bánffy) branches of the Tomaj

Tomaj ( or ; it, Tomadio) is a village in the Municipality of Sežana in the Littoral region of Slovenia, near the border with Italy.

Church

The parish church in the settlement is dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul and belongs to the Diocese of ...

and Gutkeled The coat-of-arms of the Hungarian Gutkeled clan

Gutkeled (spelling variants: Gut-Keled, Guthkeled, Guth-Keled) was the name of a ''gens'' (Latin for "clan"; ''nemzetség'' in Hungarian) in the Kingdom of Hungary, to which a number of Hungarian nob ...

clans. Nándor Knauz called him "Lucas Bánffy de Alsó Lindva de genere Guthkeled" in his work, the ''Monumenta ecclesiae Strigoniensis'' (1874), whose proposal is faulty. Aside from surnames being anachronisms for the time, the Felsőlendvais were the ones who originated from the Gutkeled clan (and there is no such "Bánffy de Felsőlendva" kinship) instead of the Bánffys de Alsólendva. Both families adopted their surname in the 14th century after their distinguished members, Nicholas Gutkeled and Nicholas Hahót respectively, bore the title of ban. Historian Ubul Kállay rejected the aforementioned theories and argued Apa and Lucas were the sons of Alexius

Alexius is the Latinized form of the given name Alexios ( el, Αλέξιος, polytonic , "defender", cf. Alexander), especially common in the later Byzantine Empire. The female form is Alexia ( el, Αλεξία) and its variants such as Alessia ...

, a Ban of Slavonia during the reign of Stephen II of Hungary

Stephen II ( hu, II István; hr, Stjepan II; sk, Štefan II; 1101 – early 1131), King of Hungary and Croatia, ruled from 1116 until 1131. His father, King Coloman, had him crowned as a child, thus denying the crown to his uncle Álmos. I ...

. Therefore, Kállay referred to Lucas with the surname "Bánfi" anachronistically and theorised he was a member of the Gutkeled clan and brother of Martin Gutkeled, who erected the Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

abbey of Csatár

Csatár is a village in Zala County, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, ...

. Later academic works and historians – including Gyula Pauler, Bálint Hóman

Bálint Hóman (29 December 1885 – 2 June 1951) was a Hungarian scholar and politician who served as Minister of Religion and Education twice: between 1932–1938 and between 1939–1942. He died in prison in 1951 for his support of the fasc ...

, Gyula Kristó

Gyula Kristó (11 July 1939 – 24 January 2004) was a Hungarian historian and medievalist, member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

The Hungarian Academy of Sciences ( hu, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, MTA) is the most important and pres ...

and Ferenc Makk – refer to him as simply "Archbishop Lucas".

Education and early career

From around 1150 to 1156, Lucas studied at theUniversity of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

, where he was a student of Gerard la Pucelle

Gerard la Pucelle (sometimes Gerard Pucelle;Weigand "Transmontane Decretists" ''History of Medieval Canon Law'' pp. 182-183 1117 – 13 January 1184) was a peripatetic Anglo-French scholar of canon law, clerk, and Bishop of Coventry.

Life ...

, a scholar of canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

and later the Bishop of Coventry

The Bishop of Coventry is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Coventry in the Province of Canterbury. In the Middle Ages, the Bishop of Coventry was a title used by the bishops known today as the Bishop of Lichfield.

The present ...

. He was one of the first Hungarians who attended a foreign university and the first known Hungarian alumnus of the newly established University of Paris. He acquired a high degree in church law and earned the respect of the other students there. Lucas could be the first Hungarian cleric who became familiar with ''Decretum Gratiani

The ''Decretum Gratiani'', also known as the ''Concordia discordantium canonum'' or ''Concordantia discordantium canonum'' or simply as the ''Decretum'', is a collection of canon law compiled and written in the 12th century as a legal textbook b ...

'', an early-mid 12th century collection of canon law compiled as a legal textbook. Among his fellow pupils was supposedly English chronicler Walter Map

Walter Map ( la, Gualterius Mappus; 1130 – 1210) was a medieval writer. He wrote '' De nugis curialium'', which takes the form of a series of anecdotes of people and places, offering insights on the history of his time.

Map was a court ...

(Gualterius Mappus), who recalled Lucas in his only surviving work ''De nugis curialium

''De nugis curialium'' (Medieval Latin for ''"Of the trifles of courtiers"'' or loosely ''"Trinkets for the Court"'') is the major surviving work of the 12th century Latin author Walter Map. He was an English courtier of Welsh descent. Map claimed ...

''. He described Lucas as a highly educated man and a gracious Christian; he stated that Lucas unselfishly shared his goods and meals with his fellow students. Map added that Lucas had his own accommodation and personnel within the university (supporting his upper-class origins) and gladly made donations. However, Map (born around 1140) was definitely younger than Lucas and attended the school a decade later in the 1160s, suggesting that he heard the anecdote secondhand.

As a student, Lucas established productive relationships with English scholars and clerics like John of Salisbury

John of Salisbury (late 1110s – 25 October 1180), who described himself as Johannes Parvus ("John the Little"), was an English author, philosopher, educationalist, diplomat and bishop of Chartres.

Early life and education

Born at Salisbury, En ...

. In the following decades, John of Salisbury and Walter Map became acquainted with Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then ...

, a significant and powerful prelate in 12th-century England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. Historian György Györffy

György Györffy (26 September 1917 – 19 December 2000) was a Hungarian historian, and member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences ( hu, MTA).

Biography

Györffy was born in Szucság (Suceagu, today part of Baciu, Romania), Hungary the son o ...

compared their careers and found several similarities between the pro-papal activities of Lucas and Thomas Becket in the upcoming decades. According to Györffy, they did not know each other personally (Thomas Becket was a secretary of Theobald of Bec

Theobald of Bec ( c. 1090 – 18 April 1161) was a Norman archbishop of Canterbury from 1139 to 1161. His exact birth date is unknown. Some time in the late 11th or early 12th century Theobald became a monk at the Abbey of Bec, risin ...

by the time Lucas resided in Paris), but they knew about each other through mutual acquaintances and used similar ecclesiastical tools to defend their interests against the secular royal power. As Map narrated in his anecdote about Lucas, Hugh of le Mans, Bishop of Acre informed him about Lucas' later encounters with the warring Árpád dynasty

The Árpád dynasty, consisted of the members of the royal House of Árpád (), also known as Árpáds ( hu, Árpádok, hr, Arpadovići). They were the ruling dynasty of the Principality of Hungary in the 9th and 10th centuries and of the Kingd ...

of Hungary, which Becket learned through Map.

When he returned to Hungary, Lucas was elected Bishop of Eger in 1156. He was still referred to as bishop-elect throughout in 1156 until March 1157. When Gervasius, Bishop of Győr

Gervasius ( hu, Gyárfás; died after 1157 or 1158) was a Hungarian prelate who served as Bishop of Győr from 1156 to 1157 or 1158.

Career

Gervasius or Geruasius started his ecclesiastical career as a member of the royal chapel during the reign ...

interceded with Géza II to grant the right to collect salt to the Archdiocese of Esztergom at Nána and Kakat (present-day Štúrovo, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

), he was addressed as bishop during his act as witness to the document. His election was confirmed by Pope Adrian IV

Pope Adrian IV ( la, Adrianus IV; born Nicholas Breakspear (or Brekespear); 1 September 1159, also Hadrian IV), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 4 December 1154 to his death in 1159. He is the only Englishman t ...

in the previous weeks. Due to a lack of sources, there is no record of Lucas' activity or function as the Bishop of Eger; his name only appears in the list of dignitaries of the various royal charters issued by Géza II. In 1157 political unrest occurred in Hungary; chronicler Rahewin

Rahewin was an important German chronicler at the abbey of Freising in Bavaria. He was secretary and chaplain to Otto von Freising

Otto is a masculine German given name and a surname. It originates as an Old High German short form (variants ''A ...

records that King Géza II's youngest brother, Stephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

, began conspiring with their ambitious uncle, Beloš, and other lords against the monarch. Géza II expelled his rebellious brother and sentenced him to death, while Beloš lost his influence over the royal court and fled Hungary in the latter half of the year. His departure resulted in Apa's political ascent to the position of Ban of Slavonia in late 1157. It is plausible Apa supported the growth of Lucas' ecclesiastical career and had a role in his brother's return to Hungary. After their failed rebellion, Géza II's two brothers, Ladislaus and Stephen sought refuge in the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

by 1160, where they found shelter in the court of Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Manuel I Komnenos

Manuel I Komnenos ( el, Μανουήλ Κομνηνός, translit=Manouíl Komnenos, translit-std=ISO; 28 November 1118 – 24 September 1180), Romanization of Greek, Latinized Comnenus, also called Porphyrogennetos (; "born in the purple"), w ...

at Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

.

Archbishop of Esztergom

Influence over Géza II

Martyrius, Archbishop of Esztergom

Martyrius or Martirius (died 26 April 1158) was a Hungarian prelate in the 12th century, who served as Bishop of Veszprém from around 1127 to 1137, Bishop of Eger from 1142 to 1150, and finally Archbishop of Esztergom from 1151 until his death.

...

died in the spring of 1158 and was soon succeeded by Lucas. Apa and Lucas became the strongest proponents of Géza II during his last regnal years and respectively held the most distinguished secular and ecclesiastical dignities. When the king made a donation in favor of the Cathedral of Saint Domnius

The Cathedral of Saint Domnius ( hr, Katedrala Svetog Duje), known locally as the ''Sveti Dujam'' or colloquially ''Sveti Duje'', is the Catholic cathedral in Split, Croatia. The cathedral is the seat of the Archdiocese of Split-Makarska, headed ...

and its archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

Gaudius Gaudius was Archbishop of Split

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Split-Makarska ( hr, Splitsko-makarska nadbiskupija; la, Archidioecesis Spalatensis-Macarscensis) is a Metropolitan archdiocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic church in Cr ...

twice in 1158, the brothers only appeared in his accompaniment by name. Lucas' sympathized with the reformist wing in the Roman Curia, which also affected Géza II's foreign policies in the following years. He was dubbed as the "representative of extreme Gregorianism" in Hungary by later scholars. As theologian József Török expressed, Lucas "vigilantly guarded the interests of the legitimate Pope lexander IIIand the Church" during his first years as archbishop. He was one of the first Hungarian prelates who thought on a whole European and Christian universalist

Christian universalism is a school of Christian theology focused around the doctrine of universal reconciliation – the view that all human beings will ultimately be saved and restored to a right relationship with God. "Christian universalism" ...

scale and integrated into the contemporary mainstream school of clerical theology. Literary historian János Győry suggested that Lucas sympathized with the heretic movements prevalent in the region – Albigensians

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. Foll ...

, Patarenes and Bogomils

Bogomilism ( Bulgarian and Macedonian: ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", bogumilstvo, богумилство) was a Christian neo-Gnostic or dualist sect founded in the First Bulgarian Empire by the priest Bogomil during the reign of Tsar P ...

, but the majority of scholars do not share this fringe theory

A fringe theory is an idea or a viewpoint which differs from the accepted scholarship of the time within its field. Fringe theories include the models and proposals of fringe science, as well as similar ideas in other areas of scholarship, such a ...

.

Initially, Géza II supported the efforts of

Initially, Géza II supported the efforts of Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on ...

against the pro-papal Italian communes (that were later known collectively as the Lombard League), and even sent Hungarian auxiliary troops to accompany the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

to Italy between 1158 and 1160. Barbarossa forced the Italian towns to surrender in September 1158. However, Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

and Crema

Crema or Cremas may refer to:

Crema

* Crema, Lombardy, a ''comune'' in the northern Italian province of Cremona

* Crema (coffee), a thin layer of foam at the top of a cup of espresso

* Crema (dairy product)

Crema is the Spanish word for cream. I ...

openly rebelled against the emperor's rule after the Diet of Roncaglia

The Diet of Roncaglia, held near Piacenza, was an Imperial Diet, a general assembly of the nobles and ecclesiasts of the Holy Roman Empire and representatives of Northern Italian cities held in 1154 and in 1158 by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa to ...

ordered the restoration of imperial rights. Géza II sent his envoys to Barbarossa's camp and promised to dispatch further reinforcements against the rebellious towns. The death of Pope Adrian IV on 1 September 1159 divided

Division is one of the four basic operations of arithmetic, the ways that numbers are combined to make new numbers. The other operations are addition, subtraction, and multiplication.

At an elementary level the division of two natural numb ...

the college of the cardinals

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

: the majority of the cardinals opposed Barbarossa while a minority supported him. The first group elected Alexander III as pope, but Barbarossa's supporters chose Victor IV instead. Barbarossa convened a synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word ''wikt:synod, synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin ...

to Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the capit ...

to end the schism. Géza II sent his envoys to the church council where Victor IV was declared the lawful pope in February 1160. However, Archbishop-elect Lucas remained loyal to Alexander III and persuaded Géza II to start negotiations with Alexander III's representatives. Géza II switched allegiances after most of the other European monarchs joined Alexander III. Géza II's envoys announced his decision to Alexander III in early 1161, but he only informed the emperor of his recognition of Alexander III in the autumn of the same year. A letter from Lucas to his ally, Eberhard, Archbishop of Salzburg, who was the leading pro-Alexander figure in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, revealed his influence carried significant weight with Géza II when he changed the direction of his foreign policy. Lucas presented the case as if he alone had been responsible for Géza II's recognition of Pope Alexander, as he wrote "I have managed through appeals to cause our Lord the King and our whole church to accept Alexander". Several historians – including Gyula Pauler and József Gerics – accepted the letter's contents and considered Lucas' significant role in negotiating with the pro-Barbarossa envoy, Bishop Daniel of Prague

Daniel is a masculine given name and a surname of Hebrew origin. It means "God is my judge"Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 68. (cf. Gabriel—"God is my strength" ...

in 1161 at Easter before Daniel's official meeting with Géza II. However, Ferenc Makk notes there is no other source which emphasises Lucas' role in the events beside his own letter.

Géza II and Pope Alexander III's envoy, papal legate Pietro di Miso

Pietro di Miso (died 17 September 1174) was Italian cardinal. He was elevated to the cardinalate by Pope Adrian IV in the consistory of February 1158. Initially he was cardinal-deacon of S. Eustachio, but in 1166 he was promoted to the order of c ...

signed a concordat

A concordat is a convention between the Holy See and a sovereign state that defines the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state in matters that concern both,René Metz, ''What is Canon Law?'' (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1960 st Ed ...

in the summer of 1161 that Lucas mediated. It guaranteed that Géza II would not depose or transfer prelates without the consent of the Holy See, the Holy See could not send papal legates to Hungary without the king's permission, and Hungarian prelates were only allowed to appeal to the Holy See with the king's consent. Pope Alexander, who was fully aware of Lucas' allegiance and foreign policy activities, showed his appreciation by sending Lucas the archiepiscopal pallium

The pallium (derived from the Roman ''pallium'' or ''palla'', a woolen cloak; : ''pallia'') is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the pope, but for many centuries bestowed by the Holy See upon metropolit ...

in July 1161, confirming that Lucas' election occurred three years earlier. According to a decretal

Decretals ( la, litterae decretales) are letters of a pope that formulate decisions in ecclesiastical law of the Catholic Church.McGurk. ''Dictionary of Medieval Terms''. p. 10

They are generally given in answer to consultations but are sometimes ...

of Pope Alexander III

Pope Alexander III (c. 1100/1105 – 30 August 1181), born Roland ( it, Rolando), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 September 1159 until his death in 1181.

A native of Siena, Alexander became pope after a con ...

issued in 1167 or 1168, when the papal legate, cardinal Pietro di Miso was sent to Hungary to hand over the pallium to Lucas, the archbishop's brother "Alban" (most scholars identified him with Apa) provided a horse for the legate when Pietro and his escort entered the Hungarian border via Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

across the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

. The letter stated that Archbishop Lucas worried this step could be seen as simony

Simony () is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things. It is named after Simon Magus, who is described in the Acts of the Apostles as having offered two disciples of Jesus payment in exchange for their empowering him to imp ...

in the Roman Curia. Pope Alexander reassured the prelate with Biblical phrases and warned Lucas not to disturb him with trivial matters. The decretal, which later became part of ''Decretales Gregorii IX

The Decretals of Gregory IX ( la, Decretales Gregorii IX), also collectively called the , are a source of medieval Catholic canon law. In 1230, Pope Gregory IX ordered his chaplain and confessor, St. Raymond of Penyafort, a Dominican, to form ...

'' (or ''Liber extra''), reflects Lucas' rigid individuality, excessive strictness, and extreme Gregorian views which characterized his reign as Archbishop of Esztergom.

18th-century historian Miklós Schmitth notes that Lucas successfully recovered the stolen gems

Gems, or gemstones, are polished, cut stones or minerals.

Gems or GEMS may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

*Gems (Aerosmith album), ''Gems'' (Aerosmith album), 1988

*Gems (Patti LaBelle album), ''Gems'' (Patti LaBelle album), 1994

*G ...

of the late Martyrius from the thief Jordanus immediately after being elected as archbishop. According to a royal charter supposedly issued by Stephen III, Géza II ordered Ded of Vác and Chama of Eger to rededicate the Szentjobb Abbey (present-day Sâniob

Sâniob (; tr, Şenköy) is a commune in Bihor County, Crișana, Romania. The village was named after Stephen I of Hungary's Holy Dexter - his preserved right hand which was kept in an abbey here. The name was granted by Ladislaus I of Hungary i ...

in Romania) with Lucas' consent. It also stated that the Benedictine monastery of Szentjobb was attacked and plundered by the sons of a certain "Palatine

A palatine or palatinus (in Latin; plural ''palatini''; cf. derivative spellings below) is a high-level official attached to imperial or royal courts in Europe since Roman times.

Paul" thereafter; as a result, Archbishop Lucas excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

them. Historian Tamás Körmendi questioned the validity of the issuance, which suffers from 18th-century misinterpretations, explanations, anachronisms, and factual errors.

Dynastic struggles

Székesfehérvár

Székesfehérvár (; german: Stuhlweißenburg ), known colloquially as Fehérvár ("white castle"), is a city in central Hungary, and the country's ninth-largest city. It is the regional capital of Central Transdanubia, and the centre of Fejér ...

. Immediately after the coronation, Byzantine Emperor Manuel, who attempted to extend his influence over the neighboring kingdom, dispatched an army to Hungary which advanced as far as Haram (now Ram, Serbia) and sent envoys to Hungary to promote the claim of the young monarch's namesake uncle to the Hungarian throne. Most of the lords opposed Stephen as their king because of his familial relationship with Manuel. The magnates decided to accept Stephen's uncle, Ladislaus II, as a "compromise candidate" between being bribed by the Byzantines and being afraid of a potential invasion by the Emperor. Stephen III's army was routed at Kapuvár

Kapuvár (; german: Kobrunn) is a small but ancient town of some 11,000 inhabitants in Győr-Moson-Sopron county, Hungary.

The town is known for its thermal water which some believe has hydrotherapy, hydrotherapeutic properties. It is served by ...

and he fled from Hungary and sought refuge in Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

six weeks after his coronation.

Archbishop Lucas stayed in Hungary after the Byzantine intervention and was one of the few who remained loyal to Stephen and refused to crown Ladislaus; as a result, Mikó, Archbishop of Kalocsa performed the ceremony in July 1162, despite the coronation of the Hungarian monarch

The coronation of the Hungarian monarch was a ceremony in which the king or queen of the Kingdom of Hungary was formally crowned and invested with regalia. It corresponded to the coronation ceremonies in other European monarchies. While in countr ...

being the Archbishop of Esztergom's responsibility for centuries. Lucas considered Ladislaus II to be an usurper and excommunicated him through his envoy, declaring that he had unlawfully seized the crown from his nephew. Lucas also excommunicated his fellow archbishop Mikó for his participation in the process. As Makk noted, the legal basis for Lucas to impose ecclesiastical punishment against Ladislaus II was provided by Article 17 of St. Stephen

Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ''Stéphanos'', meaning "wreath, crown" and by extension "reward, honor, renown, fame", often given as a title rather than as a name; c. 5 – c. 34 AD) is traditionally venerated as the protomartyr or first ...

's Second Code and Article 2 of the so-called Second Synod of Esztergom during the reign of Coloman Coloman, es, Colomán (german: Koloman (also Slovak, Czech, Croatian), it, Colomanno, ca, Colomà; hu, Kálmán)

The Germanic origin name Coloman used by Germans since the 9th century.

* Coloman, King of Hungary

* Coloman of Galicia-Lodomeria ...

. According to Map's ''De nugis curialium'', the new monarch tried to intimidate and persuade the prelate to his side, but Lucas remained steadfast and strongly condemned his controversial accession to the Hungarian throne. In response the archbishop was arrested and imprisoned shortly thereafter.

Ladislaus II attempted to reconcile himself with his opponents and released Archbishop Lucas at Christmas at Pope Alexander III's request. Map preserved the circumstances of his release (see above). However, Lucas did not yield to him, continued to support Stephen III, and became a central figure of Ladislaus' domestic opposition. His obstinate resistance indicated that any possibility of a reconciliation between the partisans of Stephen III and Ladislaus II was lost. Lucas did not recognize the legitimacy of Ladislaus' rule and organised the possibility of an open rebellion against the pro-Byzantine regime. Lucas' political interests conflicted with Pope Alexander's, who maintained a moderately good relationship with the courts of Ladislaus II and Emperor Manuel on account of the constant threat of Barbarossa's anti-papal policy. Church historian József Török argues Lucas saw the consistent and exclusive application of the ancient custom of

Ladislaus II attempted to reconcile himself with his opponents and released Archbishop Lucas at Christmas at Pope Alexander III's request. Map preserved the circumstances of his release (see above). However, Lucas did not yield to him, continued to support Stephen III, and became a central figure of Ladislaus' domestic opposition. His obstinate resistance indicated that any possibility of a reconciliation between the partisans of Stephen III and Ladislaus II was lost. Lucas did not recognize the legitimacy of Ladislaus' rule and organised the possibility of an open rebellion against the pro-Byzantine regime. Lucas' political interests conflicted with Pope Alexander's, who maintained a moderately good relationship with the courts of Ladislaus II and Emperor Manuel on account of the constant threat of Barbarossa's anti-papal policy. Church historian József Török argues Lucas saw the consistent and exclusive application of the ancient custom of primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

as the pledge of the stability of the kingdom, which was endangered by the ambitions of Ladislaus and Stephen. Lucas spoke of the negative example of the Byzantine Empire, which experienced civil wars, dynastic struggles, cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words in different languages that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymology, etymological ancestor in a proto-language, common parent language. Because language c ...

murders and anarchy. Lucas' resistance led Ladislaus to imprison him again within days. Meanwhile, Stephen III returned to Hungary with an army and captured Pressburg

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

(present-day Bratislava in Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

). Soon after, Ladislaus II died suddenly on 14 January 1163. Many of his contemporaries considered Lucas' curse as a contributing factor to his death.

Stephen III could not take the crown after his uncle's death because his other uncle, Stephen IV (Ladislaus II's brother), acceded to the throne. Archbishop Lucas refused to crown him and remained in custody. The coronation was performed again by Archbishop Mikó on 27 January. Lucas excommunicated Stephen IV and declared his rule illegal. Stephen IV's unveiled support for the interests of the Byzantine Empire caused discontent among the Hungarian barons. Stephen III mustered an army of barons who had deserted his uncle and supplemented it with German mercenaries. He defeated his uncle at Székesfehérvár on 19 June 1163. Stephen IV was captured, but his nephew released him, at Lucas's advice, on the condition that he never return to Hungary. According to Henry of Mügeln

Henry may refer to:

People

* Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portuga ...

's chronicle, Lucas was freed from prison by then.

Stephen III's reign

The dethroned Stephen IV first fled to the Holy Roman Empire, but left shortly afterwards for the Byzantine Empire, where Emperor Manuel promised him support. The Byzantine Emperor sent an army to Hungary to help Stephen IV regain the throne from his nephew. Large-scale military campaigns characterized the following years; Lucas, along with the Dowager QueenEuphrosyne

Euphrosyne (; grc, Εὐφροσύνη), in ancient Greek religion and mythology, was one of the Charites, known in ancient Rome as the ''Gratiae'' (Graces). She was sometimes called Euthymia (Εὐθυμία) or Eutychia (Εὐτυχία).

Fa ...

, advised Stephen III throughout his reign. After a peace treaty with Emperor Manuel, Stephen III agreed to send his younger brother, Béla, to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

and to allow the Byzantines to seize Béla's duchy, which included Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

, Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

and Sirmium

Sirmium was a city in the Roman province of Pannonia, located on the Sava river, on the site of modern Sremska Mitrovica in the Vojvodina autonomous provice of Serbia. First mentioned in the 4th century BC and originally inhabited by Illyrians an ...

. In an attempt to recapture these territories, Stephen III waged wars against the Byzantine Empire between 1164 and 1167, but could not defeat the Byzantines.

During the war with the Byzantine Empire, Stephen III sought assistance from Emperor Frederick, Pope Alexander's enemy. The alliance, despite its reasonable military considerations, was strongly opposed by Lucas and the pope, who requested Lucas via Archbishop Eberhard of Salzburg to prevent Stephen III from seeking military help from the Holy Roman Empire. Pope Alexander, additionally, complained that

During the war with the Byzantine Empire, Stephen III sought assistance from Emperor Frederick, Pope Alexander's enemy. The alliance, despite its reasonable military considerations, was strongly opposed by Lucas and the pope, who requested Lucas via Archbishop Eberhard of Salzburg to prevent Stephen III from seeking military help from the Holy Roman Empire. Pope Alexander, additionally, complained that celibacy

Celibacy (from Latin ''caelibatus'') is the state of voluntarily being unmarried, sexually abstinent, or both, usually for religious reasons. It is often in association with the role of a religious official or devotee. In its narrow sense, the ...

was not universal among the prelates in Hungary. There is also evidence that suggests that Stephen III seized Church revenues to finance his war with the Byzantine Empire. As a result, Lucas' relationship worsened with his monarch sometime after 1165 or 1166, and resulted in leaving the royal court for years. The royal chapel, which was responsible for drafting and issuing royal diplomas under the guidance of the Archbishop of Esztergom, ceased its operations during Lucas' voluntary withdrawal. His notary Becen remained loyal to him, and only three royal charters were preserved between 1166 and 1169; as only church employees were the only ones able to read and write, the lower number of charters drafted represented the temporary decline of literacy.

Pope Alexander sent his legate Cardinal Manfred to Hungary in 1169, who discussed the debated issues with the king, the queen mother, and the prelates. Manfred and Lucas convened a synod to Esztergom (called Third Council of Esztergom). The negotiations ended in an agreement that prohibited the monarch from arbitrarily deposing or relocating the prelates or confiscating their property. Stephen III also acknowledged Alexander as the legitimate pope. Makk wrote Archbishop Lucas was one of the key drafters of the concordat.

However the pope supported Stephen III against Lucas when the archbishop attempted to hinder the consecration of the king's protégé, Andrew

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in List of countries where English is an official language, English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is freq ...

, Bishop-elect of Győr, because of his allegedly non-canonical election. Although Manfred admonished Lucas to celebrate Andrew's consecration, he refused to do so, demonstrating that his relationship with the Holy See was no longer harmonious by the end of the 1160s. A letter issued by the pope around March 1179 stated that sometime after 1169, Archbishop Lucas excommunicated Stephen III and Queen Euphrosyne because of an "insignificant subterfuge". Archbishop Lucas reconciled with Stephen III around March 1171, according to Map. Stephen III died one year later on 4 March 1172. His funeral mass in Esztergom was celebrated by Lucas, according to Arnold of Lübeck

Arnold of Lübeck (died 1211–1214) was a Benedictine abbot, a chronicler, the author of the ''Chronica Slavorum'' and advocate of the papal cause in the Hohenstaufen conflict. He was a monk at St. Ägidien monastery in Braunschweig, then from 117 ...

's ''Chronica Slavorum

The ''Chronica Sclavorum'' or ''Chronicle of the Slavs'' is a medieval chronicle which recounts the pre-Christian culture and religion of the Polabian Slavs, written by Helmold (ca. 1120 – after 1177), a Saxon priest and historian. It describe ...

''.

Ambivalent relationship with Béla III

Following the death of Stephen III, a Hungarian delegation visited Emperor Manuel and Béla inSardica

Serdika or Serdica (Bulgarian: ) is the historical Roman name of Sofia, now the capital of Bulgaria.

Currently, Serdika is the name of a district located in the city. It includes four neighbourhoods: "Fondovi zhilishta"; "Banishora", "Orlandovts ...

(now Sophia in Bulgaria) and invited the prince to the Hungarian throne. Béla, who lived in Constantinople since 1163 and was the former designated heir of the Byzantine Empire, arrived in Hungary with his wife Agnes of Antioch

Agnes of Antioch ( 1154 – c. 1184) was Queen of Hungary from 1172 until 1184 as the first wife of Béla III.

The accidental discovery of her intact tomb during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 has provided an opportunity for patriotic demonst ...

in Székesfehérvár in late April or early May. It is uncertain if Archbishop Lucas initially supported Béla's claim (as historian György Györffy and András Kubinyi argued), or if he was against Béla's invitation from the beginning. In a letter written by Pope Alexander III, Béla was unanimously elected king by the "dignitaries of the Hungarian kingdom", including Lucas. However, Béla's coronation was delayed because Lucas refused to perform the ceremony. The Archbishop accused the king of simony

Simony () is the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things. It is named after Simon Magus, who is described in the Acts of the Apostles as having offered two disciples of Jesus payment in exchange for their empowering him to imp ...

because Béla had given a precious cloak (''pallium'') to his delegate. A theory suggests that Lucas also feared that the influence of " schismatics" would increase under Béla's rule. Nevertheless, the majority of the barons and prelates remained loyal to Béla, who sought the assistance of the Holy See against the archbishop. Pope Alexander III imposed a papal rebuke on Lucas for his inflexibility and ordered him to crown Béla, but the archbishop continued to refuse to crown Béla III. Upon Béla's request, Pope Alexander III temporarily authorized the Archbishop of Kalocsa

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdioc ...

(presumably Chama) to anoint Béla king and perform his coronation, which took place on 18 January 1173.

Lucas became a member of the internal opposition which rejected Béla's reign. The archbishop allied with his former opponent Queen Euphrosyne and supported the aspirations of the late Géza II's youngest son,

Lucas became a member of the internal opposition which rejected Béla's reign. The archbishop allied with his former opponent Queen Euphrosyne and supported the aspirations of the late Géza II's youngest son, Géza Géza is a Hungarian given name and may refer to any of the following:

* Benjamin Géza Affleck

* Géza, Grand Prince of the Hungarians

* Géza I of Hungary, King of Hungary

* Géza II of Hungary, King of Hungary

* Géza, son of Géza II of Hungar ...

, who aimed to continue the anti-Byzantine and pro-papal (at least, since 1169) policies of Stephen III. Around the same time, Lucas lifted Euphrosyne from papal anathema

Anathema, in common usage, is something or someone detested or shunned. In its other main usage, it is a formal excommunication. The latter meaning, its ecclesiastical sense, is based on New Testament usage. In the Old Testament, anathema was a cr ...

unilaterally, which was imposed on her after she had allegedly confiscated the provostship of Székesfehérvár from its provost, Gregory. To avoid a possible civil war, Béla III imprisoned Géza (who had already contacted Emperor Frederick) soon after his coronation. Archbishop Lucas fell out of favour with Béla and was ignored by him in the first years of his reign. Instead of Lucas, the Archbishop of Kalocsa baptised Béla's first-born son, Emeric

Emerich, Emeric, Emerick and Emerik are given names and surnames. They may refer to:

Given name Pre-modern era

* Saint Emeric of Hungary (c. 1007–1031), son of King Stephen I of Hungary

* Emeric, King of Hungary (1174–1204)

* Emeric Kökénye ...

, in 1174. Lucas lost his political importance through total neglect after his long-time rival Andrew rose to become Archbishop of Kalocsa in 1176. Andrew, as a skilled diplomat, became the ''de facto'' head of the Catholic Church in Hungary and was acknowledged by Pope Alexander III. Lucas did not appear in witness lists of the subsequent royal charters for the next eight years until 1180. However, administering sacraments to members of the royal family had always been the Archbishops of Esztergom's responsibility. By 1176, Béla overthrew Géza's partisans' resistance and put Euphrosyne in confinement. Historian Pál Engel

Pál Engel (27 February 1938 – 21 August 2001) was a Hungarian medievalist historian and archivist, and member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. He served as General Director of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences between 199 ...

observed Lucas' "anxiety proved to be wholly unjustified", as Béla III governed Hungary as an independent monarch and excluded the neighboring empire's influence beyond its borders throughout his reign.

Lucas' retirement from state affairs resulted in the issuance of written records and the termination of official literacy within the royal chapel. Several educated and skilled members of its staff left the royal court to follow Lucas, which can be traced by the drastic reduction in the number of royal decrees until 1181. The royal chapel never regained its former influence, even after Béla III and Lucas reconciled after 1179. In the imperial court of Constantinople, Béla learnt the importance of a well-organised administration and emphasised the importance of written records. In 1181 he ordered that a charter was to be issued for all transactions proceeding in his presence. This decision resulted in permanently establishing the Royal Chancery and the proliferation of governmental literacy independent from the ecclesiastical institutions. Béla III aimed to separate the issuance of royal charters from the court clergy after his long-lasting jurisdictional conflicts with Lucas.

Béla III's long-time favorite, Andrew, Archbishop of Kalocsa, insulted his royal authority between 1178 and 1179. The king deprived him and his supporter, Gregory, Provost of Székesfehérvár Chapter, of their offices and seized the Archbishop's revenues. Béla also confiscated Székesfehérvár's royal chapel, which belonged to the direct jurisdiction of the Holy See. Andrew fled Hungary and petitioned to the Roman Curia, requesting an investigation at the Third Council of the Lateran

The Third Council of the Lateran met in Rome in March 1179. Pope Alexander III presided and 302 bishops attended. The Catholic Church regards it as the eleventh ecumenical council.

By agreement reached at the Peace of Venice in 1177 the bitter ...

. Pope Alexander III threatened Béla III with excommunication and punished him with ecclesiastic sanctions. Béla had reconciled with Archbishop Lucas, who absolved him and excommunicated Andrew of Kalocsa and his clerical partisans. Lucas charged Andrew with the unlawful domination of priests and clergymen of the royal churches, which were traditionally placed under the territorial authority of the Archdiocese of Esztergom. Beside personal conflicts, this case was also a chapter of the long-time rivalry between the Esztergom and Kalocsa sees for the leadership of the Hungarian church. In his harshly-worded letter sent to Hungary in March 1179, Pope Alexander listed Lucas' past "sins" in detail since the rule of Stephen III and threatened to excommunicate him if he maintained the punishment he imposed on Andrew. In another letter, Pope Alexander III urged the Hungarian clergy not to obey Lucas' instructions. Despite the papal efforts Lucas retained his influence at the royal court until his death. Lucas' last mention of being alive was on 20 August 1181. He died shortly thereafter, roughly around the same time as Pope Alexander III's death (30 August 1181). Lucas was succeeded as Archbishop of Esztergom by Nicholas

Nicholas is a male given name and a surname.

The Eastern Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Anglicanism, Anglican Churches celebrate Saint Nicholas every year on December 6, which is the name day for "Nicholas". In Greece, the n ...

in 1181.

Legacy and canonization process

Györffy noted that Lucas was the first prelate in the continentalEurope

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, who spread the cult of Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then ...

(later sanctified as Saint Thomas of Canterbury), who was murdered in 1170 and was canonized

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christianity, Christian communion declaring a person worthy of Cult (religious practice), public veneration and enterin ...

by Pope Alexander III three years later. Upon Béla's invitation, plausibly under the influence of Lucas, Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

monks came from Pontigny Abbey

Pontigny Abbey (french: Abbaye de Pontigny), the church of which in recent decades has also been the cathedral of the Mission de France, otherwise the Territorial Prelature of Pontigny (french: Cathédrale-abbatiale de Notre-Dame-de-l’Assompt ...

– Becket's former place of exile – and set up a new filial abbey at Egres in 1179. Lucas also founded a provostship at the outskirts of Esztergom, dedicated to Becket (present-day Szenttamás, a borough of Esztergom). Some of Becket's relics were transferred to Esztergom in the 16th century.

Lucas was styled as "saintly" by the records of Henry of Mügeln and Cistercian friar Alberic of Trois-Fontaines

Alberic of Trois-Fontaines (french: Aubri or ''Aubry de Trois-Fontaines''; la, Albericus Trium Fontium) (died 1252) was a medieval Cistercian chronicler who wrote in Latin. He was a monk of Trois-Fontaines Abbey in the diocese of Châlons-sur-M ...

. According to Italian historian Odorico Raynaldi

Odorico Raynaldi or Rinaldi (1595 – 22 January 1671) was an Italian historian and Oratorian. He is also known as Odericus Raynaldus, or just Raynald.

Biography

Raynaldi was born at Treviso of a patrician family. He studied at Parma and Pa ...

, Lucas died as an "eminent moral priest", who cured sick people of their various illnesses, honouring him as a saint. His canonisation was first initiated by Robert, Archbishop of Esztergom

Robert ( hu, Róbert; died 1 November 1239) was a French-born prelate in the Kingdom of Hungary in the first decades of the 13th century. He was Archbishop of Esztergom between 1226 and 1239 and Bishop of Veszprém from 1209 till 1226. He playe ...

in 1231, who had several conflicts with Andrew II of Hungary

Andrew II ( hu, II. András, hr, Andrija II., sk, Ondrej II., uk, Андрій II; 117721 September 1235), also known as Andrew of Jerusalem, was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1205 and 1235. He ruled the Principality of Halych from 1188 ...

and the intervening secular authority. This influenced Lucas to promote the political goals of Robert, according to historian Gyula Kristó

Gyula Kristó (11 July 1939 – 24 January 2004) was a Hungarian historian and medievalist, member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

The Hungarian Academy of Sciences ( hu, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, MTA) is the most important and pres ...

. Upon his request, Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

entrusted Bulcsú Lád, Bishop of Csanád

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

and two other clergymen on 28 August 1231 to conduct an investigation and send their report to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. After receiving the report and the letter in support of Andrew, the pope ordered papal legate Giacomo di Pecorari on 17 February 1233 to deal with the canonisation issue among other matters. However the protocol was lost and the canonisation was postponed. Egyed Hermann and József Félegyházy stated that the initiative failed in silence due to the Mongol invasion of 1241. Other historians argue Lucas was not necessarily a suitable and exemplary person for the Holy See as he has repeatedly represented the interests of his church against even the pope. Andrew's son, Béla IV

Béla may refer to:

* Béla (crater), an elongated lunar crater

* Béla (given name), a common Hungarian male given name

See also

* Bela (disambiguation)

* Belá (disambiguation)

* Bělá (disambiguation) Bělá, derived from ''bílá'' (''whit ...

unsuccessfully attempted to initiate his canonisation. There were some semi official attempts by some prelates afterwards, including Ignác Batthyány

Ignác Batthyány (born 30 June 1741, Németújvár (present-day Güssing), Kingdom of Hungary; died 17 November 1798, Gyulafehérvár (present-day Alba Iulia), Principality of Transylvania) was a Roman Catholic Bishop of Transylvania.

He was l ...

, János Scitovszky

János Keresztély Scitovszky de Nagykér ( hu, nagykéri Scitovszky János Keresztély; sk, Ján Krstiteľ Scitovský; 1 November 1785 – 19 October 1866) was a Hungarian prelate, Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church and Archbishop of Eszterg ...

and József Mindszenty

József Mindszenty (; 29 March 18926 May 1975) was a Hungarian cardinal of the Catholic Church who served as Archbishop of Esztergom and leader of the Catholic Church in Hungary from 1945 to 1973. According to the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', ...

.

Notes

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Lucas, Archbishop of Esztergom 1120s births 1181 deaths Archbishops of Esztergom Year of birth unknown 12th-century Roman Catholic archbishops in Hungary Bishops of Eger University of Paris alumni Prisoners and detainees of Hungary Hungarian prisoners and detainees 12th-century Hungarian people