Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a

British flag officer in the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought about a number of decisive British naval victories during the

French Revolutionary

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are consider ...

and

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest naval commanders in history.

Nelson was born into a moderately prosperous

Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

family and joined the navy through the influence of his uncle,

Maurice Suckling, a high-ranking naval officer. Nelson rose rapidly through the ranks and served with leading naval commanders of the period before obtaining his own command at the age of 20, in 1778. He developed a reputation for personal valour and firm grasp of tactics, but suffered periods of illness and unemployment after the end of the

American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. The outbreak of the

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

allowed Nelson to return to service, where he was particularly active in the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

. He fought in several minor engagements off

Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

and was important in the capture of

Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, where he was wounded and partially lost sight in one eye, and subsequent diplomatic duties with the Italian states. In 1797, he distinguished himself while in command of at the

Battle of Cape St Vincent. Shortly after that battle, Nelson took part in the

Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, where the attack failed and he lost his right arm, forcing him to return to England to recuperate. The following year he won a decisive victory over the French at the

Battle of the Nile

The Battle of the Nile (also known as the Battle of Aboukir Bay; french: Bataille d'Aboukir) was a major naval battle fought between the British Royal Navy and the Navy of the French Republic at Aboukir Bay on the Mediterranean coast off the ...

and remained in the Mediterranean to support the

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

against a French invasion.

In 1801, Nelson was dispatched to the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

and defeated

neutral Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

at the

Battle of Copenhagen. He commanded the blockade of the French and Spanish fleets at Toulon and, after their escape, chased them to the

West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

and back but failed to bring them to battle. After a brief return to England, he took over the

Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

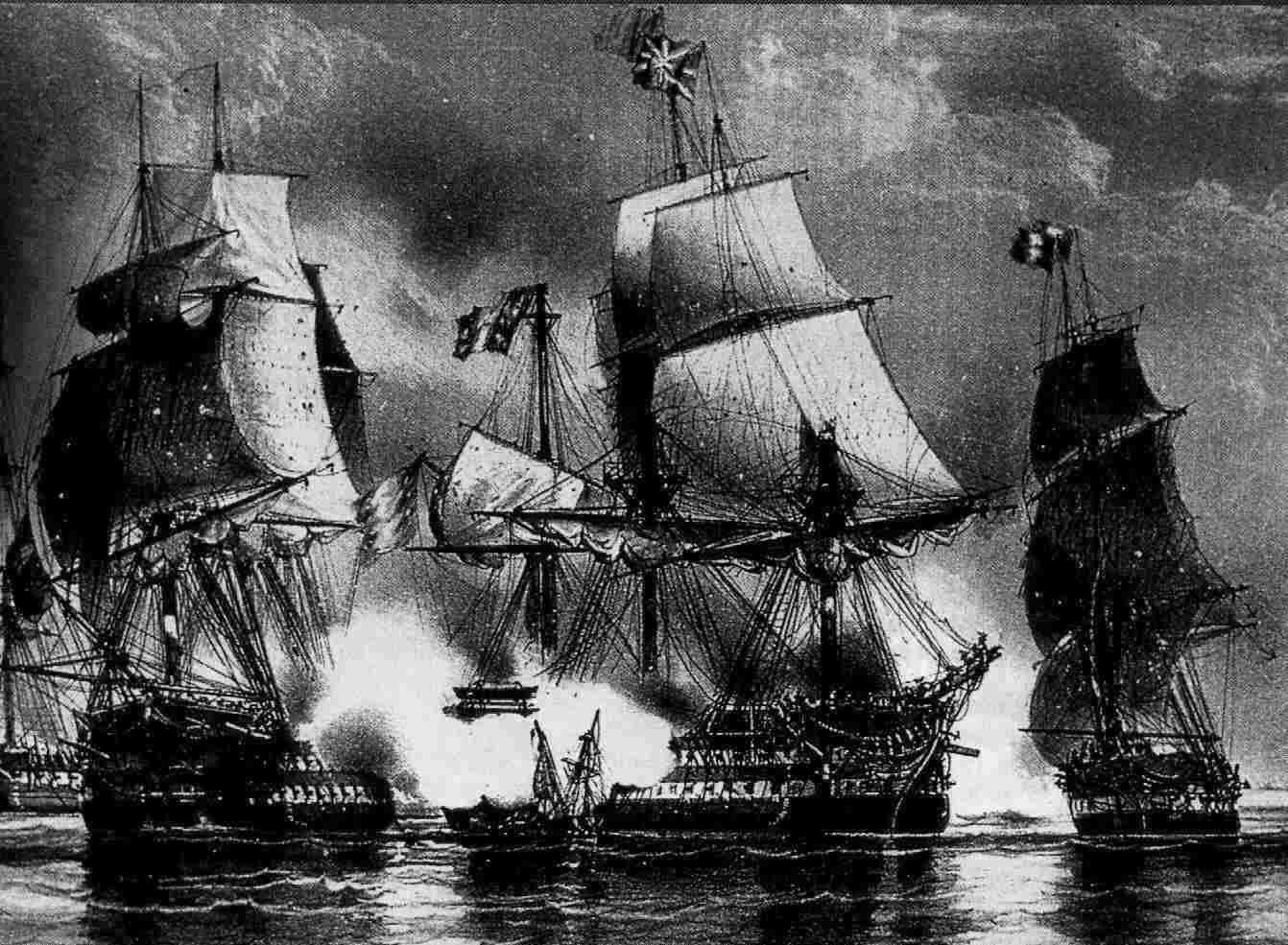

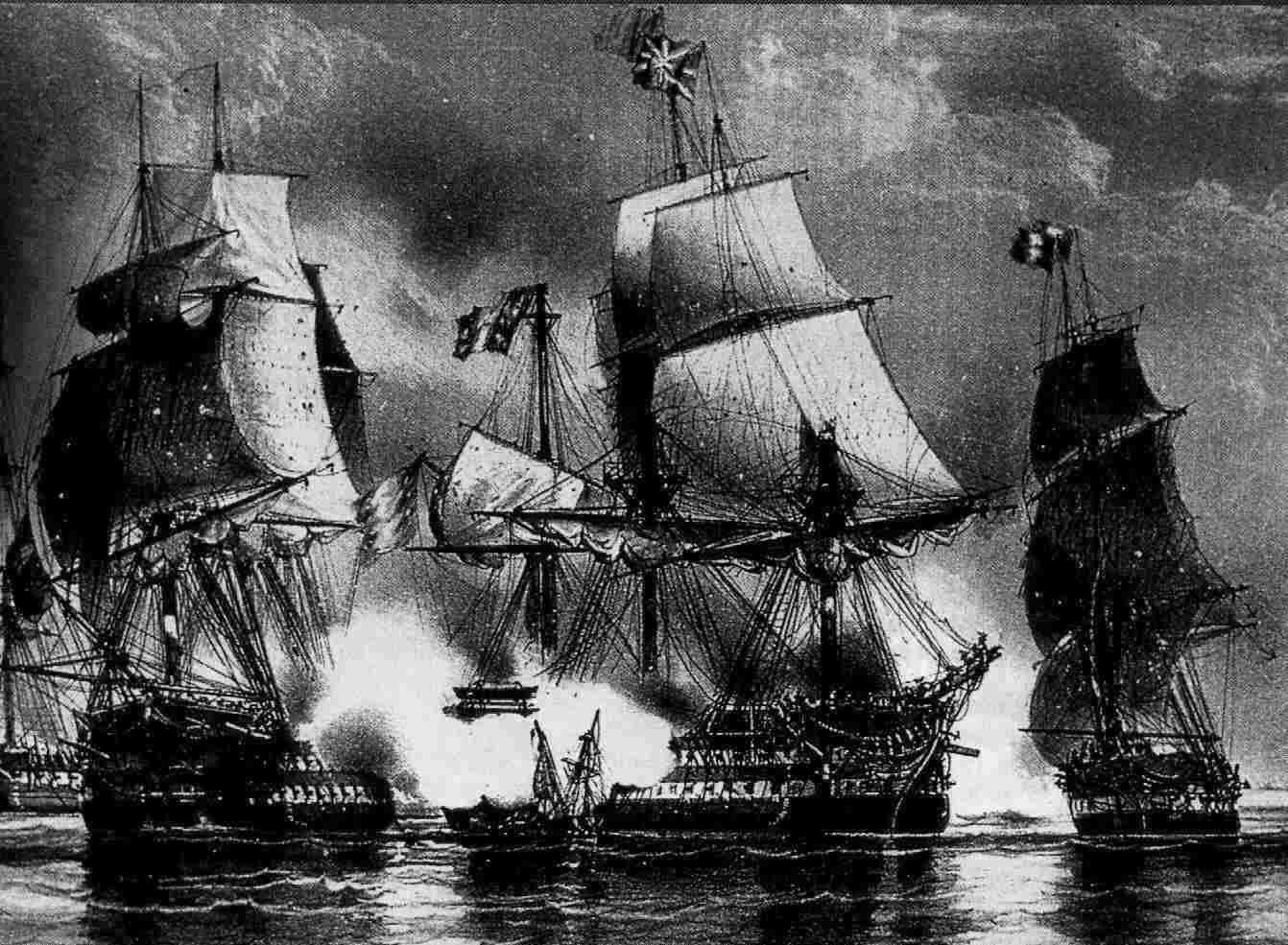

blockade, in 1805. On 21 October 1805, the Franco-Spanish fleet came out of port, and Nelson's fleet engaged them at the

Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (180 ...

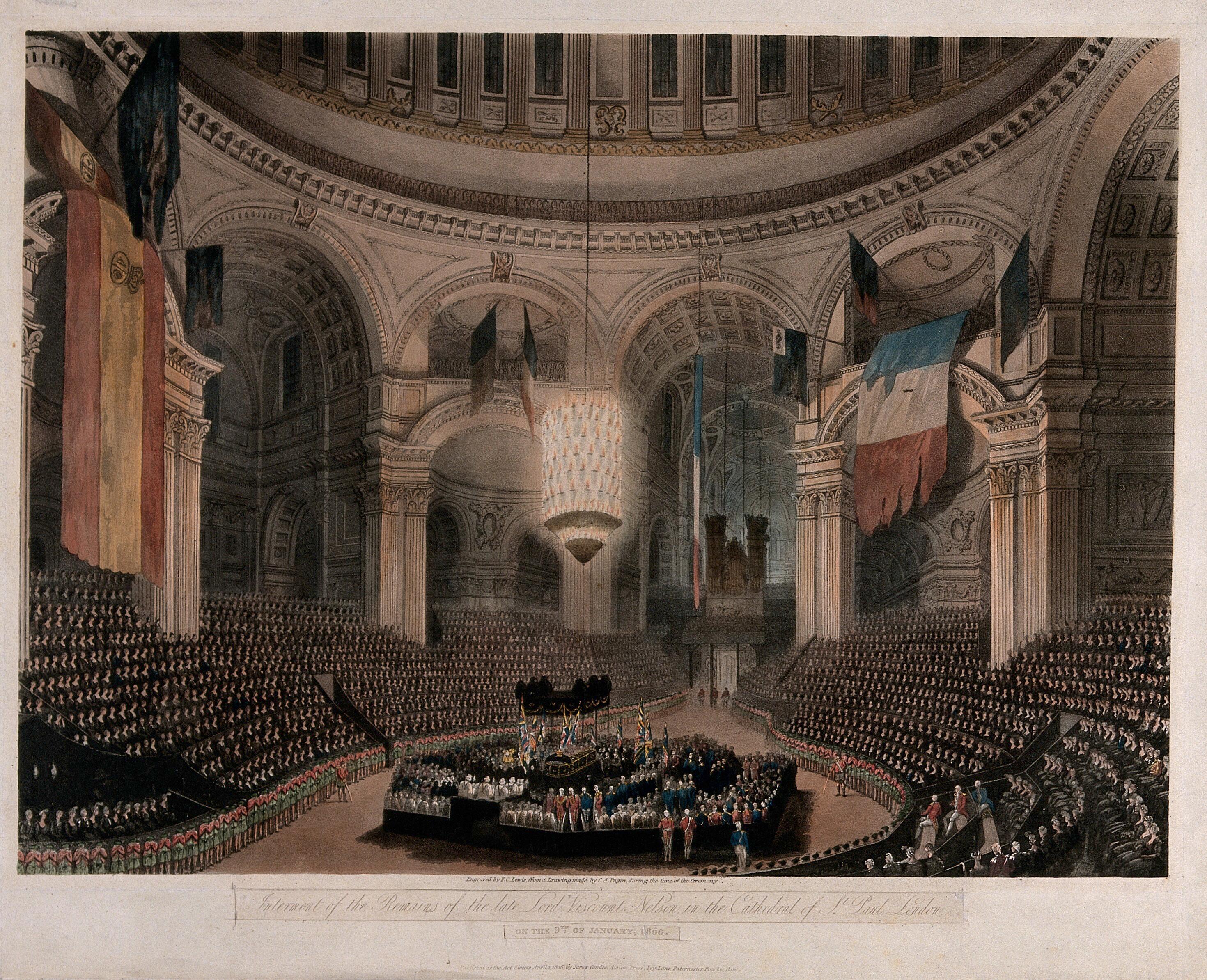

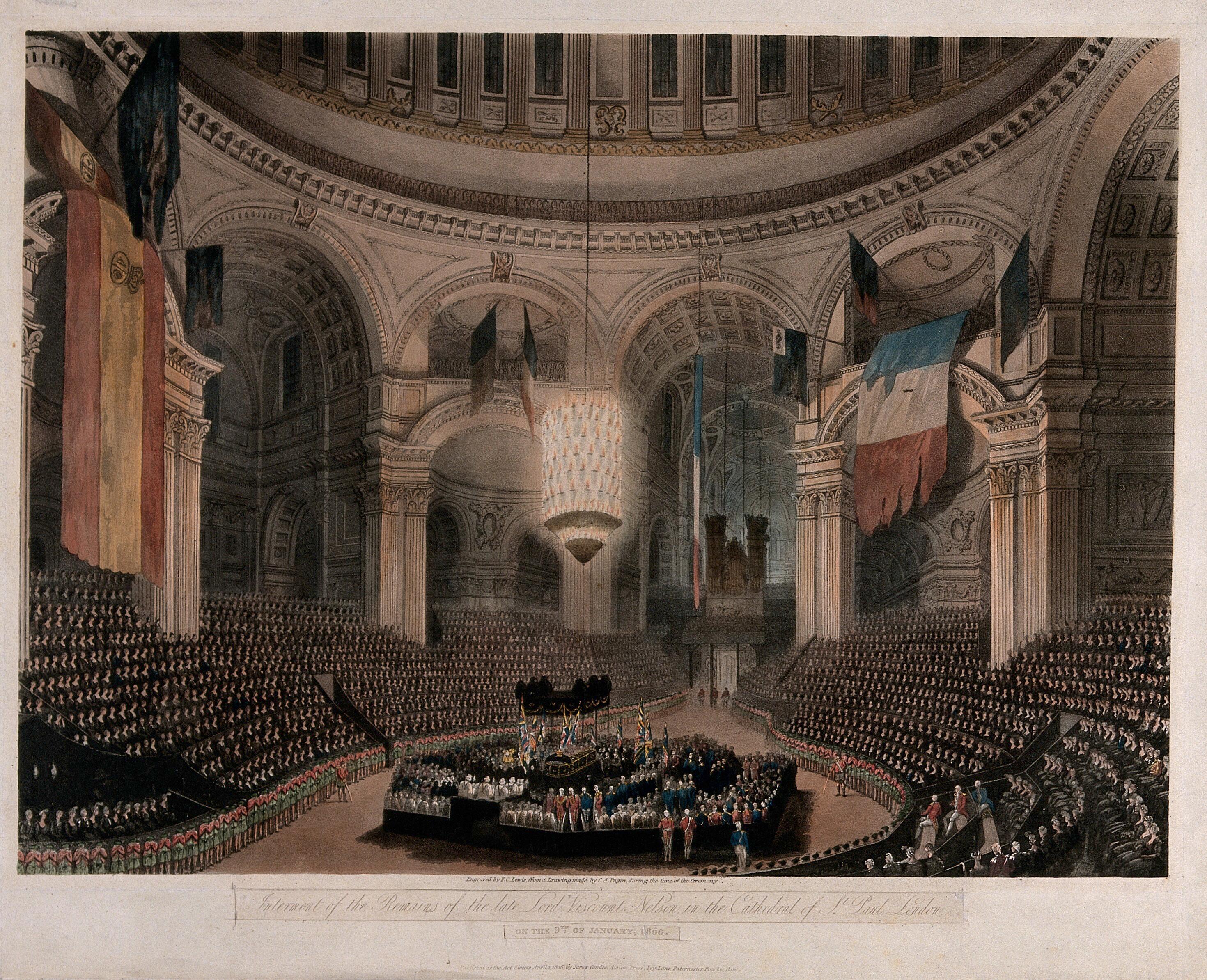

. The battle became one of Britain's greatest naval victories, but Nelson, aboard , was fatally wounded by a French sharpshooter. His body was brought back to England, where he was accorded a state funeral.

Nelson's death at Trafalgar secured his position as one of Britain's most heroic figures. His signal just prior to the commencement of the battle, "

England expects that every man will do his duty

"England expects that every man will do his duty" was a signal sent by Vice-Admiral of the Royal Navy Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson from his flagship as the Battle of Trafalgar was about to commence on 21 October 1805.

During the battl ...

," is regularly quoted and paraphrased. Numerous monuments, including

Nelson's Column in

Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson commemo ...

, London, and the

Nelson Monument in

Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, have been created in his memory.

Early life

Horatio Nelson was born on 29 September 1758, at a rectory in

Burnham Thorpe

Burnham Thorpe is a small village and civil parishes in England, civil parish on the River Burn, Norfolk, River Burn and near the coast of Norfolk, England. It is famous for being the birthplace of Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson ...

,

Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

, England; the sixth of eleven children of the Reverend

Edmund Nelson and his wife

Catherine Suckling

Catherine Suckling (9 May 1725 – 26 December 1767) was the mother of Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson. Catherine had eleven children of which Nelson was the third surviving son.

Family and marriage

Catherine was born on 9 May 1725 in Barsh ...

.

[Sugden, 2004, p. 36] He was named "

Horatio

Horatio is an English male given name, an Italianized form of the ancient Roman Latin '' nomen'' (name) '' Horatius'', from the Roman '' gens'' (clan) '' Horatia''. The modern Italian form is ''Orazio'', the modern Spanish form ''Horacio''. It app ...

" after his godfather

Horatio Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford

Horatio Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (12 June 1723 – 24 February 1809)L. G. Pine, The New Extinct Peerage 1884-1971: Containing Extinct, Abeyant, Dormant and Suspended Peerages With Genealogies and Arms (London, U.K.: Heraldry Today, 1972), page ...

(1723–1809),

[Pettigrew 1849, p. 1] the first cousin of his maternal great-grandmother Anne Turner (1691–1768). Horatio Walpole was a nephew of

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, (26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745; known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole) was a British statesman and Whig politician who, as First Lord of the Treasury, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Leader ...

, 1st Earl of Orford, the ''

de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

'' first

prime minister of Great Britain

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pri ...

.

[''Britannica'' 11th edition, p. 352] Nelson retained a strong Christian faith throughout his life.

Nelson's uncle Maurice Suckling was a high-ranking naval officer, and is believed to have had a major impact on Nelson's life.

Nelson's peculiarly strong hatred for the French probably also came from Maurice - describing them as 'gobblers' in conversation with him as a child.

Catherine Suckling lived in the village of

Barsham, Suffolk

Barsham is a village and civil parish in the East Suffolk district of the English county of Suffolk. It is about west of Beccles, south of the River Waveney on the edge of The Broads National Park. It is spread either side of the B1062 Beccle ...

, and married the Reverend Edmund Nelson at

Beccles

Beccles ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the English county of Suffolk.OS Explorer Map OL40: The Broads: (1:25 000) : . The town is shown on the milestone as from London via the A145 and A12 roads, north-east of London as the crow fli ...

Church,

Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

, in 1749. Nelson's aunt, Alice Nelson was the wife of Reverend Robert Rolfe, Rector of

Hilborough, Norfolk, and grandmother of Sir

Robert Monsey Rolfe

Robert Monsey Rolfe, 1st Baron Cranworth, PC (18 December 1790 – 26 July 1868) was a British lawyer and Liberal politician. He twice served as Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain.

Background and education

Born at Cranworth, Norfolk, he was ...

.

[Nicolas, The Despatches and Letters of Lord Nelson, Vol, I p. 18] Rolfe twice served as

Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

.

Nelson attended

Paston Grammar School

Paston may refer to:

People

* Edward Paston (1550–1630), a poet and amateur musician

* George Paston (1860–1936), British author and critic

* Mark Paston (born 1976), New Zealand footballer

* Thomas Paston (died 1550), an English politician ...

,

North Walsham, until he was 12 years old, and also attended

King Edward VI's Grammar School in

Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

. His naval career began on 1 January 1771, when he reported to the newly commissioned

third-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third r ...

as an

ordinary seaman

__NOTOC__

An ordinary seaman (OS) is a member of the deck department of a ship. The position is an apprenticeship to become an able seaman, and has been for centuries. In modern times, an OS is required to work on a ship for a specific amount o ...

and

coxswain under his maternal uncle, Captain

Maurice Suckling, who commanded the vessel. Shortly after reporting aboard, Nelson was appointed a

midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

, and began officer training. Early in his service, Nelson discovered that he experienced

seasickness

Motion sickness occurs due to a difference between actual and expected motion. Symptoms commonly include nausea, vomiting, cold sweat, headache, dizziness, tiredness, loss of appetite, and increased salivation. Complications may rarely include de ...

, a chronic complaint that he experienced for the rest of his life.

[Sugden, 2004, p. 56]

East and West Indies, 1771–1780

HMS ''Raisonnable'' had been commissioned during a period of tension with Spain, but when this passed, Suckling was transferred to the

Nore

The Nore is a long bank of sand and silt running along the south-centre of the final narrowing of the Thames Estuary, England. Its south-west is the very narrow Nore Sand. Just short of the Nore's easternmost point where it fades into the cha ...

guardship and Nelson was dispatched to serve aboard the West Indiaman ''Mary Ann'' of the merchant shipping firm of

Hibbert, Purrier and Horton Hibbert, Purrier and Horton was a London-based merchant and shipping business, initially founded in 1770,Hall ''et al'', p.210. which was also extensively involved in the slave trade during the late 18th and early-mid-19th century. A partnership (it ...

, in order to gain experience at sea. He sailed from

Medway

Medway is a unitary authority district and conurbation in Kent, South East England. It had a population of 278,016 in 2019. The unitary authority was formed in 1998 when Rochester-upon-Medway amalgamated with the Borough of Gillingham to for ...

, Kent, on 25 July 1771, heading to Jamaica and Tobago, and returning to Plymouth on 7 July 1772.

He twice crossed the Atlantic, before returning to serve under his uncle as the commander of Suckling's longboat, which carried men and dispatches, to and from shore. Nelson then learnt of a

planned expedition, under the command of

Constantine Phipps, intended to survey a passage in the Arctic by which it was hoped that India could be reached: the fabled

North-East Passage

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) (russian: Се́верный морско́й путь, ''Severnyy morskoy put'', shortened to Севморпуть, ''Sevmorput'') is a shipping route officially defined by Russian legislation as lying east of No ...

.

[Pettigrew 1849, p. 4]

At his nephew's request, Suckling arranged for Nelson to join the expedition as coxswain

to Commander

Lutwidge aboard the converted

bomb vessel, . The expedition reached within ten degrees of the

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

, but, unable to find a way through the dense ice floes, was forced to turn back. By 1800, Lutwidge had begun to circulate a story that, while the ship had been trapped in the ice, Nelson had spotted and pursued a polar bear, before being ordered to return to the ship. Later, in 1809, Lutwidge had it that Nelson, and a companion, gave chase to the bear and upon being questioned as to why, replied: "I wished, Sir, to get the skin for my father."

Nelson briefly returned to ''Triumph'', after the expedition's return to Britain, in September 1773. Suckling then arranged for his transfer to ; one of two ships about to sail for the

East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around t ...

.

Nelson sailed for the East Indies on 19 November 1773, and arrived at the British outpost at

Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

on 25 May 1774. Nelson and ''Seahorse'' spent the rest of the year cruising off the coast and escorting

merchantmen

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are us ...

. With the outbreak of the

First Anglo-Maratha War, the British fleet operated in support of the

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

and in early 1775, ''Seahorse'' was dispatched to carry a cargo of the company's money to

Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second- ...

. On 19 February, two of

Hyder Ali

Hyder Ali ( حیدر علی, ''Haidarālī''; 1720 – 7 December 1782) was the Sultan and ''de facto'' ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India. Born as Hyder Ali, he distinguished himself as a soldier, eventually drawing the att ...

's

ketches attacked ''Seahorse'', which drove them off after a brief exchange of fire. This was Nelson's first experience of battle.

He spent the rest of the year escorting convoys, during which he continued to develop his navigation and ship handling skills. In early 1776, Nelson contracted malaria and became seriously ill. He was discharged from ''Seahorse'' on 14 March and returned to England aboard . Nelson spent the six-month voyage recuperating and had almost recovered by the time he arrived in Britain, in September 1776. His patron, Suckling, had risen to the post of

Comptroller of the Navy

The post of Controller of the Navy (abbreviated as CofN) was originally created in 1859 when the Surveyor of the Navy's title changed to Controller of the Navy. In 1869 the controller's office was abolished and its duties were assumed by that of ...

in 1775, and used his influence to help Nelson gain further promotion.

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

.

''Worcester'', under the command of Captain Mark Robinson, sailed as a convoy escort on 3 December, and returned with another convoy in April 1777. Nelson then travelled to London to take his lieutenant's examination on 9 April; his examining board consisted of Captains John Campbell, Abraham North, and his uncle, Maurice Suckling. Nelson passed the examination, and the next day received his commission, and an appointment to , which was preparing to sail to Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, under Captain William Locker

William Locker (16 February 1866 – 15 August 1952) was an English association football, footballer and cricketer. He played first-class cricket for Derbyshire County Cricket Club, Derbyshire between 1894 and 1903 and football for Stoke F.C., ...

. She sailed on 16 May, arrived on 19 July, and after reprovisioning, carried out several cruises in Caribbean waters. After the outbreak of the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, ''Lowestoffe'' took several prizes, one of which was taken into Navy service as ''Little Lucy''. Nelson asked for, and was given, command of her, and took her on two cruises of his own.

As well as giving him his first taste of command, it gave Nelson the opportunity to explore his fledgling interest in science. During his first cruise in command of ''Little Lucy'', Nelson led an expeditionary party to the Caicos

The Turks and Caicos Islands (abbreviated TCI; and ) are a British Overseas Territory consisting of the larger Caicos Islands and smaller Turks Islands, two groups of tropical islands in the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean and nor ...

Islands, where he made detailed notes of the wildlife and in particular a bird – now believed to be the white-necked jacobin.prize money

Prize money refers in particular to naval prize money, usually arising in naval warfare, but also in other circumstances. It was a monetary reward paid in accordance with the prize law of a belligerent state to the crew of a ship belonging to t ...

. Parker appointed him as Master and Commander of the brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the ...

on 8 December.

Nelson and ''Badger'' spent most of 1779 cruising off of the Central American coast, ranging as far as the British settlements at British Honduras (now Belize), and Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

, but without much success at interception of enemy prizes. On his return to Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and co ...

, he learnt that Parker had promoted him to post-captain on 11 June, and intended to give him another command. Nelson handed over the ''Badger'' to Cuthbert Collingwood

Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, 1st Baron Collingwood (26 September 1748 – 7 March 1810) was an admiral of the Royal Navy, notable as a partner with Lord Nelson in several of the British victories of the Napoleonic Wars, and frequently as ...

, while he awaited the arrival of his new ship: the 28-gun frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

, newly captured from the French. While Nelson waited, news reached Parker that a French fleet under the command of Charles Hector, comte d'Estaing

Jean Baptiste Charles Henri Hector, comte d'Estaing (24 November 1729 – 28 April 1794) was a French general and admiral. He began his service as a soldier in the War of the Austrian Succession, briefly spending time as a prisoner of war of the B ...

, was approaching Jamaica. Parker hastily organized his defences and placed Nelson in command of Fort Charles, which covered the approaches to Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the five most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

. D'Estaing instead headed north, and the anticipated invasion never materialised. Nelson duly took command of the ''Hinchinbrook'' on 1 September.

''Hinchinbrook'' sailed from Port Royal on 5 October 1779, and, in company with other British ships, proceeded to capture a number of American prizes. On his return to Jamaica in December, Nelson began to be troubled by a recurrent attack of malaria. Nelson remained in the West Indies in order to take part in Major-General John Dalling's attempt to capture the Spanish colonies in Central America, including an assault on the Fortress of the Immaculate Conception

The Fortress of the Immaculate Conception, (Spanish: ''El Castillo de la Inmaculada Concepción'') is a fortification located on the southern bank of the San Juan River (''Río San Juan''), in the village of El Castillo in southern Nicaragua. Th ...

, also called Castillo Viejo, on the San Juan River in Nicaragua.[Oman 1987, p. 30]

''Hinchinbrook'' sailed from Jamaica in February 1780, as an escort for Dalling's invasion force. After sailing up the mouth of the San Juan River, Nelson, with some one thousand men and four small four-pounder cannons, obtained the surrender of Castillo Viejo and its 160 Spanish defenders after a two-week siege. The British blew up the fort when they evacuated six months later, after suffering many deaths due to disease. Nelson was praised for his efforts.[Report from Colonel Polson on the capture of the fort at San Juan. ]

Parker recalled Nelson and gave him command of the 44-gun frigate, . In 1780, Nelson fell seriously ill with what seemed to be dysentery and possibly yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

,Costa Rica

Costa Rica (, ; ; literally "Rich Coast"), officially the Republic of Costa Rica ( es, República de Costa Rica), is a country in the Central American region of North America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the no ...

, and was unable to take command. He was taken to Kingston, Jamaica, to be nursed by "doctoress" Cubah Cornwallis

Cubah Cornwallis (died 1848) (often spelled Coubah, Couba, Cooba or Cuba) was a nurse or "doctress" and Obeah woman who lived in the colony of Jamaica during the late 18th and 19th century.

Early life

Little is known of her early life although re ...

, a rumored mistress of fellow captain William Cornwallis;

Nelson's views on slavery

While Nelson served in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

, he came into contact with several prominent white colonists residing there, forming friendships with many of them. These relationships led Nelson to imbibe their proslavery

Proslavery is a support for slavery. It is found in the Bible, in the thought of ancient philosophers, in British writings and in American writings especially before the American Civil War but also later through 20th century. Arguments in favor o ...

views, particularly the view that slavery was necessary to the islands' economic prosperity. According to Grindal, Nelson later used his social influence to counter the emerging abolitionist movement in Britain. University of Southampton

, mottoeng = The Heights Yield to Endeavour

, type = Public research university

, established = 1862 – Hartley Institution1902 – Hartley University College1913 – Southampton University Coll ...

academic Christer Petley contextualises this view:

:The debate over the future of slavery divided Britons. Wilberforce personified one type of British patriotism—arguing for an end to slave-trading on the basis that it was a blot on the reputation of a proud and Christian nation. Slaveholders offered their own patriotic arguments—maintaining that the trade was so instrumental to the imperial economy that Britain could ill-afford to stop it. Nelson had befriended several slaveholding colonists during his time in the Caribbean. Privately, he came to sympathise with their political outlook. It is clear that, by the time of his death at Trafalgar, he despised Wilberforce and stood in staunch opposition to the British abolitionist campaign.

Over the course of his life, Nelson came into contact numerous times with aspects of slavery and the people who were involved in that institution. These included both his relationships with Caribbean plantation owners

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

and his marriage to Fanny, a slaveowner who was born into a family which belonged to the Antiguan plantocracy. One of his friends in the West Indies was Simon Taylor, one of the richest plantation owners in Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

who owned hundreds of slaves. In 1805, Taylor wrote to Nelson, requesting that he publicly intervene in favour of the pro-slavery side in Britain's debate over abolition. Nelson wrote a letter back to Taylor, writing that "while e had

E, or e, is the fifth letter and the second vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''e'' (pronounced ); plur ...

... a tongue", he would "launch isvoice against the damnable and cursed ''(sic)'' doctrine of Wilberforce and his hypocritical allies". In the same latter, Nelson also wrote that he had always " ndeavouredto serve the Public weal, of which the West India Colonies form so prominent and interesting a part. I have ever been, and shall die, a firm friend to our present Colonial system. I was bred, as you know, in the good old school, and taught to appreciate the value of our West India possessions."

This letter was published in 1807, by the anti-abolitionist faction; some eighteen months after Nelson's death, and out of context, in an apparent attempt to bolster their cause prior to the parliamentary vote on the Abolition Bill. The wording of the letter as published in 1807—not in Nelson's handwriting, and with a poor facsimile of his signature—appears out of character for Nelson whose many other surviving letters never expressed racist or pro-slavery sentiments. Comparison with the "pressed copy" of the original letter—now part of the Bridport papers held in the British Library—shows that the published copy had 25 alterations, distorting it to give it a more anti-Abolitionist slant. Many of Nelson's actions indicate his position on the matter of slavery, most notably:

* Any West Indian slave escaping to a navy ship, including Nelson's, were signed on, paid, and treated the same as other crew members. At the end of their service they were discharged as free men. In fact, the bronze relief at the base of Nelson's column clearly shows the black George Ryan, aged 23, with musket shooting the French alongside the dying Admiral.

* In 1799, Nelson intervened to secure the release of 24 slaves being held in Portuguese galleys off Palermo.[Downer, Martyn, 2017, Nelson's Lost Jewel: The Extraordinary Story of the Lost Diamond Chelengk, p. 77][Nicolas, The Despatches and Letters of Lord Nelson, Vol, 3 p. 231]

* In 1802, when it was proposed that West Indian plantation slaves should be replaced by free, paid industrious Chinese workers—Nelson supported the idea.[Sugden 2013, p. 684]

* In 1805, Nelson rescued the black Haitian General Joseph Chretien, and his servant, from the French. They asked if they could serve with Nelson, and Nelson recommended to the Admiralty that they be paid until they could be discharged and granted passage to Jamaica. The General's mission was to end slavery, a fact of which Nelson was well aware. The general and his servant were well treated and paid.

* The Nelson family used to have a free black servant called Price. Nelson said of him he was "as good a man as ever lived" and he suggested to Emma that she invite the elderly Price to live with them. In the event, Price declined.[Pettigrew 1849, vol 2, p. 81]

Command, 1781–1796

Captain of ''Albemarle''

Nelson received orders on 23 October 1781, to take the newly refitted ''Albemarle'' to sea. He was instructed to collect an inbound convoy of the Russia Company

The Muscovy Company (also called the Russia Company or the Muscovy Trading Company russian: Московская компания, Moskovskaya kompaniya) was an English trading company chartered in 1555. It was the first major chartered joint s ...

at Elsinore, and escort them back to Britain. For this operation, the Admiralty placed the frigates and under his command.[Sugden 2004, p. 190] Nelson successfully organised the convoy and escorted it into British waters. He then left the convoy to return to port, but severe storms hampered him.[Sugden 2004, p. 195] Gales almost wrecked ''Albemarle'', as she was a poorly designed ship and an earlier accident had left her damaged, but Nelson eventually brought her into Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, in February 1782.[Sugden 2004, p. 197] There, the Admiralty ordered him to fit ''Albemarle'' for sea and join the escort for a convoy collecting at Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

, Ireland, to sail for Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, Canada.[Sugden 2004, p. 202] Nelson arrived off Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

with the convoy in late May, then detached on a cruise to hunt American privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s. Nelson was generally unsuccessful; he succeeded only in retaking several captured British merchant ships, and capturing a number of small fishing boats and assorted craft.[Sugden 2004, pp. 204–205]

In August 1782, Nelson had a narrow escape from a far superior French force under Louis-Philippe de Vaudreuil, only evading them after a prolonged chase.[Sugden 2004, p. 206] Nelson arrived at Quebec on 18 September.[Sugden 2004, p. 209] He sailed again as part of the escort for a convoy to New York. He arrived in mid-November and reported to Admiral Samuel Hood, commander of the New York station.[Sugden 2004, p. 215] At Nelson's request, Hood transferred him to his fleet and ''Albemarle'' sailed in company with Hood, bound for the West Indies.[Sugden 2004, p. 219] On their arrival, the British fleet took up position off Jamaica to await the arrival of de Vaudreuil's force. Nelson and the ''Albemarle'' were ordered to scout the numerous passages for signs of the enemy, but it became clear by early 1783 that the French had eluded Hood.[Sugden 2004, p. 220]

During his scouting operations, Nelson had developed a plan to attack the French garrison of the Turks Islands

The Turks and Caicos Islands (abbreviated TCI; and ) are a British Overseas Territory consisting of the larger Caicos Islands and smaller Turks Islands, two groups of tropical islands in the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean and no ...

. Commanding a small flotilla of frigates, and smaller vessels, he landed a force of 167 seamen and marines early on the morning of 8 March, under a supporting bombardment.[Sugden 2004, pp. 222–223] The French were found to be heavily entrenched and, after several hours, Nelson called off the assault. Several of the officers involved criticised Nelson, but Hood does not appear to have reprimanded him.[Sugden 2004, p. 224] Nelson spent the rest of the war cruising in the West Indies, where he captured a number of French and Spanish prizes.[Sugden 2004, p. 225] After news of the peace reached Hood, Nelson returned to Britain in late June 1783.[Sugden 2004, p. 227]

Island of Nevis, marriage and peace

Nelson visited France in late 1783 and stayed with acquaintances at Saint-Omer; briefly attempting to learn

Nelson visited France in late 1783 and stayed with acquaintances at Saint-Omer; briefly attempting to learn French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

during his stay. He returned to England in January 1784, and attended court as part of Lord Hood's entourage.[Sugden 2004, pp. 241–243] Influenced by the factional politics of the time, he contemplated standing for Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

as a supporter of William Pitt, but was unable to find a seat

A seat is a place to sit. The term may encompass additional features, such as back, armrest, head restraint but also headquarters in a wider sense.

Types of seat

The following are examples of different kinds of seat:

* Armchair (furniture), ...

.[Sugden 2004, p. 243]

In 1784, Nelson received command of the frigate , with the assignment to enforce the Navigation Acts

The Navigation Acts, or more broadly the Acts of Trade and Navigation, were a long series of English laws that developed, promoted, and regulated English ships, shipping, trade, and commerce between other countries and with its own colonies. The ...

in the vicinity of Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

.[Sugden 2004] The Acts were unpopular with both the Americans and the colonies.[Sugden 2004, p. 265] Nelson served on the station under Admiral Sir Richard Hughes, and often came into conflict with his superior officer over their differing interpretation of the Acts.[Sugden 2004, p. 292] The captains of the American vessels Nelson had seized sued him for illegal seizure. Because the merchants of the nearby island of Nevis supported the American claim, Nelson was in peril of imprisonment; he remained sequestered on ''Boreas'' for eight months, until the courts ruled in his favour.[Coleman 2001, p. 67]

In the interim, Nelson met Frances "Fanny" Nisbet, a young widow from a Nevis plantation family.[Sugden 2004, p. 307] Nelson developed an affection for her. In response, her uncle, John Herbert, offered him a massive dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment b ...

. Both Herbert and Nisbet concealed the fact that their famed riches were a fiction, and Fanny did not disclose the fact that she was infertile due to a womb infection. Once they were engaged, Herbert offered Nelson nowhere near the dowry he had promised.

During the Georgian era

The Georgian era was a period in British history from 1714 to , named after the Hanoverian Kings George I, George II, George III and George IV. The definition of the Georgian era is often extended to include the relatively short reign of Willi ...

, breaking a marital engagement was seen as quite dishonourable,[Sugden 2004, p. 351] The marriage was registered at Fig Tree Church in St John's Parish on Nevis. Nelson returned to England in July, with Fanny following later.[Sugden 2004, p. 366]

Nelson remained with ''Boreas'' until she was paid off in November 1787.[Sugden 2004, p. 371] He and Fanny then divided their time between Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

and London, occasionally visiting Nelson's relations in Norfolk. In 1788, they settled at Nelson's childhood home at Burnham Thorpe.[Sugden 2004, pp. 378–380] Now in reserve and on half-pay, he attempted to persuade the Admiralty—and other senior figures he was acquainted with, such as Hood—to provide him with a command. He was unsuccessful, as there were too few ships in the peacetime navy, and Hood did not intercede on his behalf.[Sugden 2004, p. 397]

Nelson spent his time trying to find employment for former crew members, attending to family affairs, and cajoling contacts in the navy for a posting. In 1792, the French revolutionary

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are consider ...

government annexed the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium), which were traditionally preserved as a buffer state. The Admiralty recalled Nelson to service and gave him command of the 64-gun , in January 1793. On 1 February, France declared war.[Sugden 2004, p. 412]

Mediterranean service

In May 1793, Nelson sailed as part of a division under the command of Vice Admiral William Hotham, joined later in the month by the rest of Lord Hood's fleet.[Sugden 2004, p. 422] The force initially sailed to Gibraltar and—with the intention of establishing naval superiority in the Mediterranean—made their way to Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

, anchoring off the port in July.[Sugden 2004, p. 427] Toulon was largely under the control of moderate republicans and royalists, but was threatened by the forces of the National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

, which were marching on the city. Short of supplies and doubting their ability to defend themselves, the city authorities requested that Hood take it under his protection. Hood readily acquiesced, and sent Nelson to carry dispatches to Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

and Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, requesting reinforcements.[Sugden 2004, p. 429]

After delivering the dispatches to Sardinia, ''Agamemnon'' arrived at Naples in early September. There, Nelson met King Ferdinand IV of Naples,[Sugden 2004, p. 431] followed by the British ambassador to the kingdom, William Hamilton.[Sugden 2004, p. 434] At some point during the negotiations for reinforcements, Nelson was introduced to Hamilton's new wife, Emma Hamilton

Dame Emma Hamilton (born Amy Lyon; 26 April 176515 January 1815), generally known as Lady Hamilton, was an English maid, model, dancer and actress. She began her career in London's demi-monde, becoming the mistress of a series of wealthy men ...

, the former mistress of Hamilton's nephew, Charles Greville.[Sugden 2004, p. 437]

The negotiations were successful, and 2,000 men and several ships were mustered by mid-September. Nelson put to sea in pursuit of a French frigate, but on failing to catch her, sailed for Leghorn, and then to Corsica.[Sugden 2004, p. 444] He arrived at Toulon on 5 October, where he found that a large French army had occupied the hills surrounding the city and was bombarding it. Hood still hoped the city could be held if more reinforcements arrived, and sent Nelson to join a squadron operating off Cagliari

Cagliari (, also , , ; sc, Casteddu ; lat, Caralis) is an Italian municipality and the capital of the island of Sardinia, an autonomous region of Italy. Cagliari's Sardinian name ''Casteddu'' means ''castle''. It has about 155,000 inhabitant ...

.[Sugden 2004, pp. 445–446]

Corsica

Early on the morning of 22 October 1793, ''Agamemnon'' sighted five sails. Nelson closed with them and discovered that they were a French squadron. He promptly gave chase, firing on the 40-gun ''Melpomene''.[Sugden 2004, pp. 446–447] During the action of 22 October 1793

The action of 22 October 1793 was a minor naval engagement fought in the Mediterranean Sea during the War of the First Coalition, early in the French Revolutionary Wars. During the engagement a lone British Royal Navy ship of the line, the 64-g ...

, he inflicted considerable damage, but the remaining French ships turned to join the battle. Realising he was outnumbered, Nelson withdrew and continued to Cagliari, arriving on 24 October.Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

on 26 October with a squadron under Commodore Robert Linzee.[Sugden 2004, pp. 452–453]

On his arrival, Nelson was given command of a small squadron consisting of ''Agamemnon'', three frigates, and a sloop, and ordered to blockade the French garrison on Corsica.ships-of-the-line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colum ...

fell into republican hands.[Sugden 2004, p. 455] Nelson's mission to Corsica took on an added significance, as it could provide the British with a naval base close to the French coast.[Sugden 2004, p. 461]

A British assault force landed on the island on 7 February, after which, Nelson moved to intensify the blockade off Bastia. For the rest of the month, he carried out raids along the coast and intercepted enemy shipping. By late February, San Fiorenzo had fallen and British troops, under Lieutenant-General David Dundas, entered the outskirts of Bastia.[Sugden 2004, p. 471] However, Dundas merely assessed the enemy positions and then withdrew, arguing that the French were too well entrenched to risk an assault. Nelson convinced Hood otherwise, but a protracted debate between the army and naval commanders meant that Nelson did not receive permission to proceed until late March. Nelson began to land guns from his ships and emplace them in the hills surrounding the town. On 11 April, the British squadron entered the harbour and opened fire, whilst Nelson took command of the land forces and commenced bombardment.[Sugden 2004, p. 487] After 45 days, the town surrendered.[Sugden 2004, p. 493] Nelson then prepared for an assault on Calvi, working in company with Lieutenant-General Charles Stuart.[Oman 1987, p. 127]

British forces landed at Calvi on 19 June, and immediately began moving guns ashore to occupy the heights surrounding the town. While Nelson directed a continuous bombardment of the enemy positions, Stuart's men began to advance. On the morning of 12 July, Nelson was at one of the forward batteries when a shot struck one of the nearby sandbags protecting the position, spraying stones and sand. Nelson was struck by debris in his right eye and forced to retire from the position. However, his wound was soon bandaged and he returned to action.[Sugden 2004, pp. 509–510] By 18 July, most of the enemy positions had been disabled and that night Stuart, supported by Nelson, stormed the main defensive position and captured it. Repositioning their guns, the British brought Calvi under constant bombardment, and the town surrendered on 10 August.[Sugden 2004, pp. 513–514] Nelson did regain partial sight in his damaged eye after the siege, but by his own account could only "...distinguish light from dark but no object.”

Genoa and the fight of the ''Ça Ira''

After the occupation of Corsica, Hood ordered Nelson to open diplomatic relations with the city-state of

After the occupation of Corsica, Hood ordered Nelson to open diplomatic relations with the city-state of Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

—a strategically important potential ally.[Sugden 2004, p. 522] Soon afterwards, Hood returned to England and was succeeded by Admiral William Hotham as commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean. Nelson put into Leghorn and, while ''Agamemnon'' underwent repairs, met with other naval officers at the port and entertained a brief affair with a local woman, Adelaide Correglia.[Sugden 2004, p. 533] Hotham arrived with the rest of the fleet in December, whereupon Nelson and ''Agamemnon'' sailed on a number of cruises with them in late 1794 and early 1795.[Sugden 2004, p. 537]

On 8 March, news reached Hotham that the French fleet was at sea and heading for Corsica. He immediately set out to intercept them, and Nelson eagerly anticipated his first fleet action. The French were reluctant to engage, and the two fleets shadowed each other on 12 March. The following day, two of the French ships collided, allowing Nelson to engage the much larger, 84-gun ''Ça Ira''. This engagement went on for two and a half hours, until the arrival of two French ships forced Nelson to veer away, having inflicted heavy casualties and considerable damage.[Sugden 2004, p. 546]

The fleets continued to shadow each other before making contact again on 14 March in the Battle of Genoa. Nelson joined the other British ships in attacking the battered ''Ça Ira'', now under tow from ''Censeur''. Heavily damaged, the two French ships were forced to surrender, and Nelson took possession of ''Censeur''. Defeated at sea, the French abandoned their plan to invade Corsica and returned to port.[Sugden 2004, p. 550]

Skirmishes and the retreat from Italy

Nelson and the fleet remained in the Mediterranean throughout the summer of 1795. On 4 July, ''Agamemnon'' sailed from San Fiorenzo, with a small force of frigates and sloops, bound for Genoa. On 6 July, Nelson ran into the French fleet and found himself pursued by several, much larger ships-of-the-line. He retreated to San Fiorenzo, arriving just ahead of the pursuing French, who broke off as Nelson's signal guns alerted the British fleet in the harbour.[Sugden 2004, p. 556] Hotham pursued the French to the Hyères Islands

Hyères (), Provençal Occitan: ''Ieras'' in classical norm, or ''Iero'' in Mistralian norm) is a commune in the Var department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region in southeastern France.

The old town lies from the sea clustered around th ...

, but failed to bring them to a decisive action. A number of small engagements were fought, but to Nelson's dismay, he saw little action.[Sugden 2004, p. 574] Nelson formulated ambitious plans for amphibious landings and naval assaults to frustrate the progress of the French Army of Italy

The Army of Italy (french: Armée d'Italie) was a field army of the French Army stationed on the Italian border and used for operations in Italy itself. Though it existed in some form in the 16th century through to the present, it is best kno ...

, which was now advancing on Genoa, but could excite little interest in Hotham.[Sugden 2004, p. 579] In November, Hotham was replaced by Sir Hyde Parker, but the situation in Italy was rapidly deteriorating: the French were raiding around Genoa and strong Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

sentiment was rife within the city itself.[Sugden 2004, p. 584]

A large French assault at the end of November, broke the allied lines, forcing a general retreat towards Genoa. Nelson's forces were able to cover the withdrawing army and prevent them from being surrounded, but he had too few ships and men to materially alter the strategic situation. The British were forced to withdraw from the Italian ports. Nelson returned to Corsica on 30 November, angry and depressed with the British failure, and questioning his future in the navy.[Sugden 2004, p. 588]

Jervis and the evacuation of the Mediterranean

In January 1796, the position of commander-in-chief of the fleet in the Mediterranean passed to Sir John Jervis, who appointed Nelson to exercise independent command over the ships blockading the French coast as a commodore.[Sugden 2004, p. 594] Nelson spent the first half of the year conducting operations to frustrate French advances and bolster Britain's Italian allies. Despite some minor successes in intercepting small French warships—such as in the action of 31 May 1796

The action of 31 May 1796 was a small action during the French Revolutionary Wars in which a Royal Navy squadron under the command of Commodore Horatio Nelson, in the 64-gun third-rate ship of the line , captured a seven-vessel French convoy that ...

, when Nelson's squadron captured a convoy of seven small vessels—he began to feel the British presence on the Italian peninsula was rapidly becoming useless.[Sugden 2004, p. 603] In June, the ''Agamemnon'' was sent back to Britain for repairs, and Nelson was appointed to the 74-gun .[Sugden 2004, p. 641] In July, he oversaw the occupation of Elba, but by September, the Genoese had broken their neutrality to declare in favour of the French.[Sugden 2004, p. 647] By October, the Genoese position and continued French advances, led the British to decide that the Mediterranean fleet could no longer be supplied. They ordered it to be evacuated to Gibraltar. Nelson helped oversee the withdrawal from Corsica and, by December 1796, was aboard the frigate HMS ''Minerve'', covering the evacuation of the garrison at Elba. He then sailed for Gibraltar.[Sugden 2004, p. 683]

During the passage, Nelson captured the Spanish frigate ''Santa Sabina'' and placed Lieutenants Jonathan Culverhouse and Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Word ...

in charge of the captured vessel; taking the frigate's Spanish captain on board ''Minerve''. ''Santa Sabina'' was part of a larger Spanish force and, the following morning, two Spanish ships-of-the-line, and a frigate, were sighted closing fast. Unable to outrun them, Nelson was initially determined to fight, but Culverhouse and Hardy raised the British colours and sailed northeast, drawing the Spanish ships after them until being captured, giving Nelson the opportunity to escape.[Sugden 2004, pp. 21–22] Nelson went on to rendezvous with the British fleet at Elba, where he spent Christmas.[Sugden 2004, p. 685] He sailed for Gibraltar in late January, and—after learning that the Spanish fleet had sailed from Cartagena—stopped just long enough to collect Hardy, Culverhouse, and the rest of the prize crew captured with ''Santa Sabina'', before pressing on through the straits to join Sir John Jervis off Cadiz.[Oman 1987, p. 174]

Admiral, 1797–1801

Battle of Cape St Vincent

Nelson joined Sir John Jervis' fleet off Cape St Vincent, and reported the Spanish movements.

Nelson joined Sir John Jervis' fleet off Cape St Vincent, and reported the Spanish movements.[Coleman 2001, p. 126] Jervis decided to engage and the two fleets met on 14 February 1797. Nelson found himself towards the rear of the British line and realised that it would be a long time before he could bring ''Captain'' into action.[Coleman 2001, p. 128] ''San Josef'' attempted to come to the ''San Nicolas''' aid, but became entangled with her compatriot and was left immobile. Nelson led his party from the deck of ''San Nicolas'' onto ''San Josef'' and captured her as well.[Coleman 2001, p. 127]

Nelson was victorious, but had disobeyed direct orders. Jervis liked Nelson and so did not officially reprimand him,[Report of the battle from Jervis. ] He did write a private letter to First Lord of the Admiralty, George Spencer, in which he said that Nelson "contributed very much to the fortune of the day".[Coleman 2001, p. 120] Nelson's account of his role prevailed, and the victory was well received in Britain; Jervis was made Earl St Vincent

Viscount St Vincent, of Meaford in the County of Stafford, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 27 April 1801 for the noted naval commander John Jervis, Earl of St Vincent, with remainder to his nephews William H ...

and Nelson, on 17 May,[Edited by H.A. Doubleday and Lord Howard de Walden.] was made a Knight of the Bath.[Coleman 2001, p. 130][Coleman 2001, p. 131]

Action off Cadiz

Nelson was given as his flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

, and on 27 May 1797, was ordered to lie off Cadiz; monitoring the Spanish fleet and awaiting the arrival of Spanish treasure ships from the American colonies.[Hibbert 1994, p. 118] He carried out a bombardment, and personally led an amphibious assault, on 3 July. During the action, Nelson's barge collided with that of the Spanish commander, and a hand-to-hand struggle ensued between the two crews. Twice, Nelson was nearly cut down and—both times—his life was saved by a seaman named John Sykes, who took the blows himself and was badly wounded. The British raiding force captured the Spanish boat and towed her back to ''Theseus''.[Reports of the attack from Jervis and Nelson. ] During this period, Nelson developed a scheme to capture Santa Cruz de Tenerife

Santa Cruz de Tenerife, commonly abbreviated as Santa Cruz (), is a city, the capital of the island of Tenerife, Province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, and capital of the Canary Islands. Santa Cruz has a population of 206,593 (2013) within its admi ...

, aiming to seize a large quantity of specie from the treasure ship ''Principe de Asturias'', which was reported to have recently arrived.[Coleman 2001, pp. 133–134]

Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife

The battle plan called for a combination of naval bombardments and an amphibious landing. The initial attempt was called off after adverse currents hampered the assault and the element of surprise was lost.

The battle plan called for a combination of naval bombardments and an amphibious landing. The initial attempt was called off after adverse currents hampered the assault and the element of surprise was lost.[Hibbert 1994, p. 121] Nelson immediately ordered another assault, but this was beaten back. He prepared for a third attempt, to take place during the night. Although he personally led one of the battalions, the operation ended in failure, as the Spanish were better prepared than had been expected and had secured strong defensive positions.[Hibbert 1994, p. 122]

Several of the boats failed to land at the correct positions in the confusion, while those that did were swept by gunfire and grapeshot. Nelson's boat reached its intended landing point, but as he stepped ashore, he was hit in the right arm by a musketball, which fractured his humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a roun ...

bone in multiple places.[Hibbert 1994, p. 123] Years later, he would excuse himself to Commodore John Thomas Duckworth

Sir John Thomas Duckworth, 1st Baronet, GCB (9 February 174831 August 1817) was an officer of the Royal Navy, serving during the Seven Years' War, the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, as the Governor ...

for not writing longer letters due to not being naturally left-handed. Later on, he developed the sensation of phantom limb in the area of his amputation and declared that he had "found the direct evidence of the existence of soul".

Meanwhile, a force under Sir Thomas Troubridge had fought their way to the main square but could go no further. Unable to return to the fleet because their boats had been sunk, Troubridge was forced to enter into negotiations with the Spanish commander, and the British were allowed to withdraw.[Bradford 2005, p. 160] The expedition had failed to achieve any of its objectives and had left a quarter of the landing force dead or wounded.[Reports of the battle from Earl St Vincent and Nelson. ]

The squadron remained off Tenerife for a further three days and, by 16 August, had rejoined Lord John Jervis' fleet off Cadiz. Despondently, Nelson wrote to Jervis:

:"A left-handed Admiral will never again be considered as useful, therefore the sooner I get to a very humble cottage the better, and make room for a better man to serve the state".[Bradford 2005, p. 162]

He returned to England, aboard HMS ''Seahorse'', arriving at Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

on 1 September. He was met with a hero's welcome; the British public had lionised Nelson after Cape St Vincent, and his wound earned him sympathy.[Bradford 2005, p. 164] They refused to attribute the defeat at Tenerife to him, preferring instead to blame poor planning on the part of St Vincent, the Secretary at War, William Windham, or even Prime Minister William Pitt.

Return to England

Nelson returned to Bath with Fanny, before moving to London in October 1797, to seek expert medical attention concerning his amputation wound. Whilst in London, news reached him that Admiral Duncan had defeated the Dutch fleet at the Battle of Camperdown

The Battle of Camperdown (known in Dutch as the ''Zeeslag bij Kamperduin'') was a major naval action fought on 11 October 1797, between the British North Sea Fleet under Admiral Adam Duncan and a Batavian Navy (Dutch) fleet under Vice-Admiral ...

.[Bradford 2005, p. 166] Nelson exclaimed that he would have given his other arm to have been present.Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

, and intended to retire there with Fanny.[Bradford 2005, p. 167] Despite his plans, Nelson was never to live there.ligature

Ligature may refer to:

* Ligature (medicine), a piece of suture used to shut off a blood vessel or other anatomical structure

** Ligature (orthodontic), used in dentistry

* Ligature (music), an element of musical notation used especially in the me ...

from his amputation site, which had caused considerable inflammation and infection, it came out of its own accord in early December, and Nelson rapidly began to recover. Eager to return to sea, he began agitating for a command and was promised the 80-gun . As she was not yet ready for sea, Nelson was instead given command of the 74-gun , to which he appointed Edward Berry

Rear Admiral Sir Edward Berry, 1st Baronet, KCB (17 April 1768 – 13 February 1831) was an officer in Britain's Royal Navy primarily known for his role as flag captain of Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson's ship HMS ''Vanguard'' at the Battle of ...

as his flag captain

In the Royal Navy, a flag captain was the captain of an admiral's flagship. During the 18th and 19th centuries, this ship might also have a "captain of the fleet", who would be ranked between the admiral and the "flag captain" as the ship's "First ...

.[Bradford 2005, p. 168]

French activities in the Mediterranean theatre were raising concern among the Admiralty as Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

was gathering forces in Southern France, but the destination of his army was unknown. Nelson, and the ''Vanguard'', were to be dispatched to Cadiz to reinforce the fleet. On 28 March 1798, Nelson hoisted his flag and sailed to join Earl St Vincent

Viscount St Vincent, of Meaford in the County of Stafford, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 27 April 1801 for the noted naval commander John Jervis, Earl of St Vincent, with remainder to his nephews William H ...

. St Vincent sent him on to Toulon with a small force to reconnoitre

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmishers, ...

French activities.[Bradford 2005, p. 172]

The Mediterranean

Hunting the French

Nelson passed through the Straits of Gibraltar, and took up position off Toulon, by 17 May, but his squadron was dispersed and blown southwards by a strong gale which struck the area, on 20 May.[Lavery 2003, pp. 65–66] While the British were battling the storm, Napoleon had sailed with his invasion fleet under the command of Vice Admiral François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers

François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers, Comte de Brueys (12 February 1753 – 1 August 1798) was a French naval officer who fought in the American War of Independence and as a commander in the French Revolutionary Wars. He led the French fleet in t ...

. Nelson, having been reinforced with a number of ships from St Vincent, went in pursuit.[Lavery 2003, p. 101]

Nelson began searching the Italian coast for Napoleon's fleet, but was hampered by a lack of frigates that could operate as fast scouts. Napoleon had already arrived at Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and, after a show of force, secured the island's surrender.[Bradford 2005, pp. 176–177] Nelson followed him there, but by the time he arrived, the French had already left. After a conference with his captains, he decided Napoleon's most likely destination now was Egypt and headed for Alexandria. However, upon Nelson's arrival, on 28 June, he found no sign of the French. Dismayed, he withdrew and began searching to the east of the port. During this time, on 1 July, Napoleon's fleet arrived in Alexandria and landed their forces unopposed.[Bradford 2005, pp. 188–189] Brueys anchored his fleet in Aboukir Bay

The Abū Qīr Bay (sometimes transliterated Abukir Bay or Aboukir Bay) (; Arabic transliteration, transliterated: Khalīj Abū Qīr) is a spacious bay on the Mediterranean Sea near Alexandria in Egypt, lying between the Rosetta mouth of the Nile a ...

, ready to support Napoleon, if required.[Bradford 2005, p. 192]

Nelson, meanwhile, had crossed the Mediterranean again, in a fruitless attempt to locate the French, and returned to Naples to re-provision.[Bradford 2005, pp. 193–194] When he again set sail, his intentions were to search the seas off Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, but he decided to pass Alexandria again for a final check. Along the way, his force found and captured a French merchant ship, which provided the first news of the French fleet: they had passed south-east of Crete a month prior—heading to Alexandria.[Bradford 2005, p. 196] Nelson hurried to the port, but again found it empty of the French. Searching along the coast, he finally discovered the French fleet in Aboukir Bay, on 1 August 1798.[Oman 1987, p. 252]

The Battle of the Nile

Nelson immediately prepared for battle, repeating a sentiment he had expressed at the battle of Cape St Vincent: "Before this time tomorrow, I shall have gained a peerage or Westminster Abbey."

Nelson immediately prepared for battle, repeating a sentiment he had expressed at the battle of Cape St Vincent: "Before this time tomorrow, I shall have gained a peerage or Westminster Abbey."[Bradford 2005, p. 198] It was late by the time the British arrived, and the French—having anchored in a strong position and possessing a combined firepower greater than that of Nelson's fleet—did not expect them to attack.[Bradford 2005, p. 200] Nelson, however, immediately ordered his ships to advance. The French line was anchored close to a line of shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface. It ...

s, in the belief that this would secure their port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

side from attack; Brueys had assumed the British would follow convention and attack his centre from the starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

side. However, Captain Thomas Foley, aboard , discovered a gap between the shoals and the French ships, and took ''Goliath'' into this channel. The unprepared French found themselves attacked on both sides; the British fleet splitting, with some following Foley and others passing down the starboard side of the French line.[Bradford 2005, p. 203]

The British fleet was soon heavily engaged, passing down the French line and engaging their ships one by one. Nelson, on ''Vanguard'', personally engaged ''Spartiate'', while also coming under fire from ''Aquilon''. At about eight o'clock, he was with Edward Berry

Rear Admiral Sir Edward Berry, 1st Baronet, KCB (17 April 1768 – 13 February 1831) was an officer in Britain's Royal Navy primarily known for his role as flag captain of Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson's ship HMS ''Vanguard'' at the Battle of ...

on the quarter-deck, when a piece of French shot struck him in the forehead. He fell to the deck, with a flap of torn skin obscuring his good eye. Blinded and half-stunned, he felt sure he would die and cried out, "I am killed. Remember me to my wife." He was taken below to be seen by the surgeon.[Bradford 2005, p. 205] After examining Nelson, the surgeon pronounced the wound non-threatening and applied a temporary bandage.[Hibbert 1994, p. 142]

The French van, pounded by British fire from both sides, had begun to surrender, and the victorious British ships continued to move down the line, bringing Brueys' 118-gun flagship ''Orient'' under constant, heavy fire. ''Orient'' caught fire under this bombardment, and later exploded. Nelson briefly came on deck to direct the battle, but returned to the surgeon after watching the destruction of ''Orient''.[Bradford 2005, p. 209]

The Battle of the Nile was a major blow to Napoleon's ambitions in the east. The fleet had been destroyed; ''Orient'', another ship and two frigates had been burnt, while seven 74-gun ships and two 80-gun ships had been captured. Only two ships-of-the-line and two frigates escaped.[Reports of the battle from Nelson. ] The forces Napoleon had brought to Egypt were stranded.Ernle Bradford

Ernle Dusgate Selby Bradford (11 January 1922 – 8 May 1986) was a noted 20th-century British historian specializing in the Mediterranean world and naval topics.Obituary in ''The Daily Telegraph'', Friday, May 9, 1986, p. 16 He was also an auth ...

, regard Nelson's achievement at the Nile as the most significant of his career, even greater than that at Trafalgar, seven years later.

Rewards

Nelson wrote dispatches to the Admiralty and oversaw temporary repairs to the ''Vanguard'' before sailing to Naples, where he was met with enthusiastic celebrations.

Nelson wrote dispatches to the Admiralty and oversaw temporary repairs to the ''Vanguard'' before sailing to Naples, where he was met with enthusiastic celebrations.[Hibbert 1994, p. 147] King Ferdinand IV of Naples, in company with the Hamiltons, greeted him in person when he arrived at port, and Sir William Hamilton invited Nelson to stay at his home.[Hibbert 1994, p. 153] Celebrations were held in honour of Nelson's birthday that September 1798, and he attended a banquet at the Hamiltons' house, where other officers had begun to notice his attentions to Emma, Lady Hamilton

Dame Emma Hamilton (born Amy Lyon; 26 April 176515 January 1815), generally known as Lady Hamilton, was an English maid, model, dancer and actress. She began her career in London's demi-monde, becoming the mistress of a series of wealthy men ...

.

Lord Jervis himself had begun to grow concerned about reports of Nelson's behaviour, but in early October, word of Nelson's victory had reached London and overshadowed the matter. The First Lord of the Admiralty, George Spencer, fainted upon hearing the news.[Hibbert 1994, p. 156] Scenes of celebration erupted across the country; balls and victory feasts were held, and church bells were rung. The City of London awarded Nelson, and his captains, swords, whilst the King ordered they be presented with special medals. Emperor Paul I of Russia