Bénéwendé Stanislas Sankara (born February 23, 1959) is a Burkinabé politician and the President of the Union for Rebirth/Sankarist Movement (UNIR/MS) party.[nationalists and populists.]Economic Freedom Fighters

The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) is a South African left-wing to far-left pan-Africanist and Marxist–Leninist political party. It was founded by expelled former African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) President Julius Malema, and hi ...

(EFF) of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, founded in 2013 by Julius Malema

Julius Sello Malema (born 3 March 1981) is a South African politician and activist who is a Member of Parliament and the leader of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), a left-wing party which he founded in 2013. He was formerly the President of ...

, claim to take significant inspiration from Sankara in terms of both style and ideology.

Khrushchevism

Khrushchevism was a form of Marxism–Leninism which consisted of the theories and policies of Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

and his administration in the Soviet Union, through de-Stalinisation

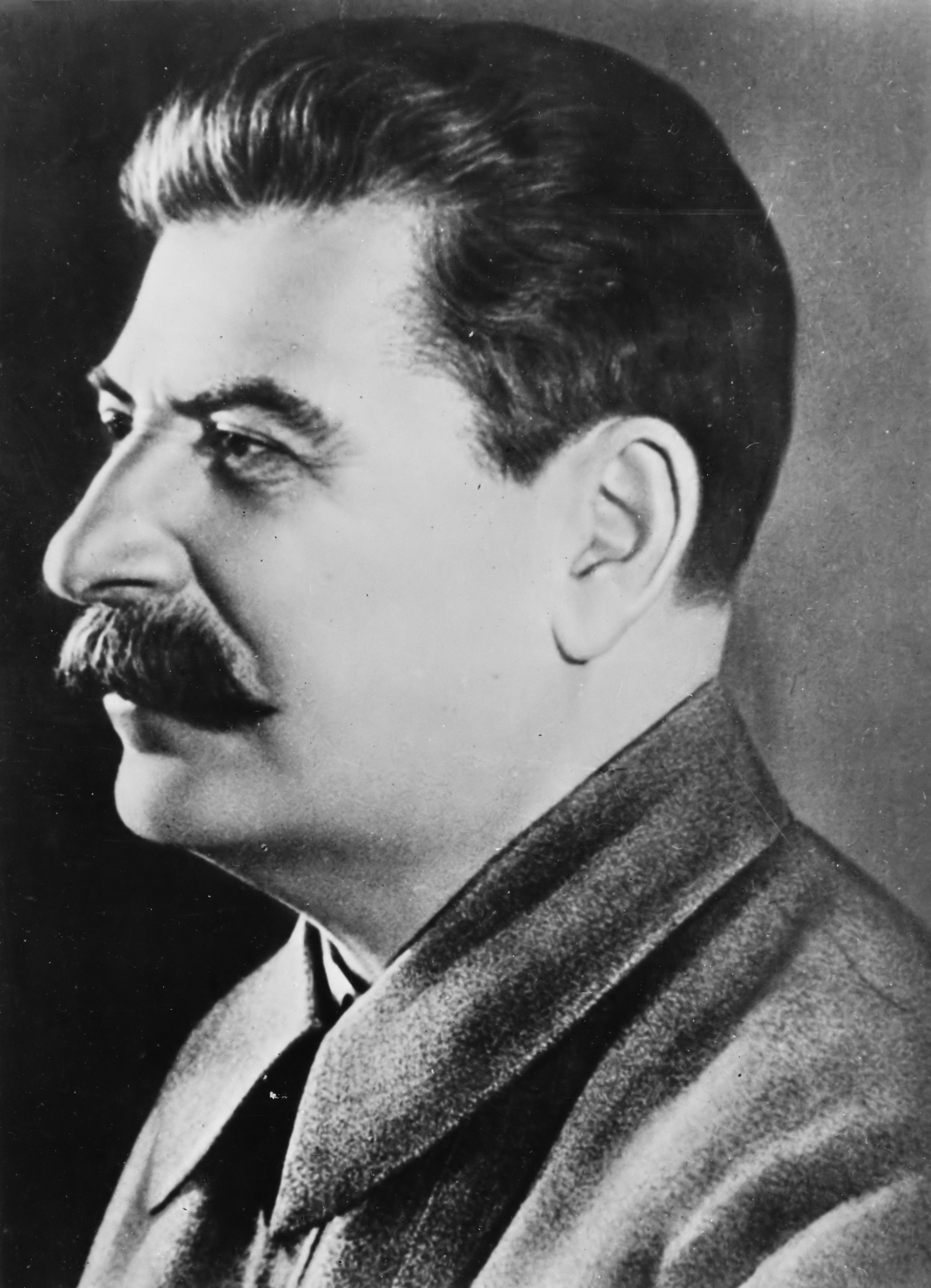

De-Stalinization (russian: десталинизация, translit=destalinizatsiya) comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the thaw brought about by ascension ...

, liberal tolerance of some cultural dissent and deviance, and a more welcoming international relations policy and attitude towards foreigners.

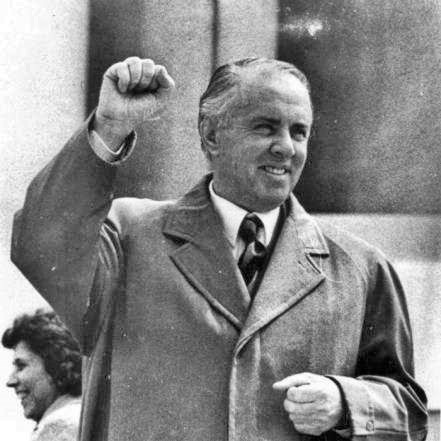

Kadarism

Kadarism ( hu, kádárizmus), also commonly called ''Goulash Communism'' or the ''Hungarian Thaw'', is the variety of socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

in Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. János Kádár and the Hungarian People's Republic

The Hungarian People's Republic ( hu, Magyar Népköztársaság) was a one-party socialist state from 20 August 1949

to 23 October 1989.

It was governed by the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, which was under the influence of the Soviet Uni ...

imposed policies with the goal to create high-quality living standard

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available, generally applied to a society or location, rather than to an individual. Standard of living is relevant because it is considered to contribute to an individual's quality ...

s for the people of Hungary coupled with economic reforms. These reforms fostered a sense of well-being and relative cultural freedom in Hungary with the reputation of being "the happiest barracks"Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

during the 1960s to the 1970s. With elements of regulated market economics as well as an improved human rights record, it represented a quiet reform and deviation from the Stalinist principles applied to Hungary in the previous decade. This period of "pseudo-consumerism" saw an increase of foreign affairs and consumption of consumer goods as well.Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy (; 7 June 1896 – 16 June 1958) was a Hungarian communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (''de facto'' Prime Minister) of the Hungarian People's Republic from 1953 to 1955. In 1956 Nagy became leader ...

's "Reform Communism" (1955–1956), where he argues that Marxism is a "science that cannot remain static but must develop and become more perfect".

Husakism

Husakism ( cs, husákismus; sk, husákizmus) is an ideology connected with the politician Gustáv Husák of Communist Czechoslovakia

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, ČSSR, formerly known from 1948 to 1960 as the Czechoslovak Republic or Fourth Czechoslovak Republic, was the official name of Czechoslovakia from 1960 to 29 March 1990, when it was renamed the Czechoslovak ...

which describes his policies of "normalization" and federalism

Federalism is a combined or compound mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments (Province, provincial, State (sub-national), state, Canton (administrative division), can ...

, while following a neo-Stalinist

Neo-Stalinism (russian: Неосталинизм) is the promotion of positive views of Joseph Stalin's role in history, the partial re-establishing of Stalin's policies on certain issues and nostalgia for the Stalin period. Neo-Stalinism over ...

line. This was the state ideology of Czechoslovakia from about 1969 to about 1989, formulated by Husák, Vasil Biľak and others.

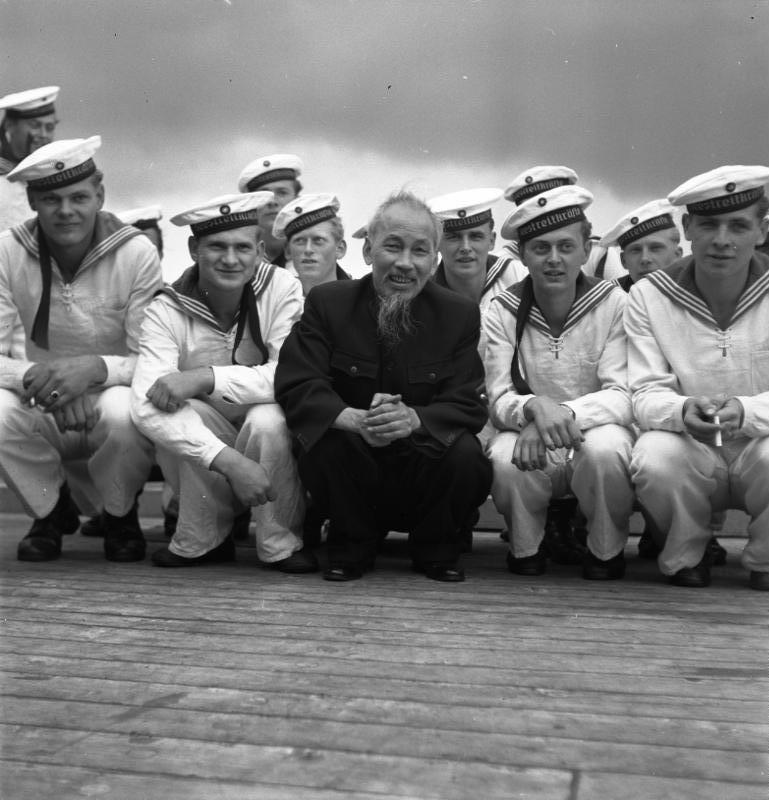

Kaysone Phomvihane Thought

Kaysone Phomvihane Thought ( lo, ແນວຄິດ ໄກສອນ ພົມວິຫານ) builds upon Marxism–Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought with the political philosophy developed by Kaysone Phomvihane

Kaysone Phomvihane ( lo, ໄກສອນ ພົມວິຫານ; 13 December 1920 – 21 November 1992) was the first leader of the Communist Lao People's Revolutionary Party from 1955 until his death in 1992. After the Communists seized po ...

, the first leader of the Communist Lao People's Revolutionary Party (LPRP). It was formalised by the LPRP at its 10th National Congress in 2016.

Other Marxist-based ideologies

Libertarian Marxism

Libertarian Marxism is a broad scope of

Libertarian Marxism is a broad scope of economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

and political philosophies that emphasize the anti-authoritarian and libertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's e ...

aspects of Marxism

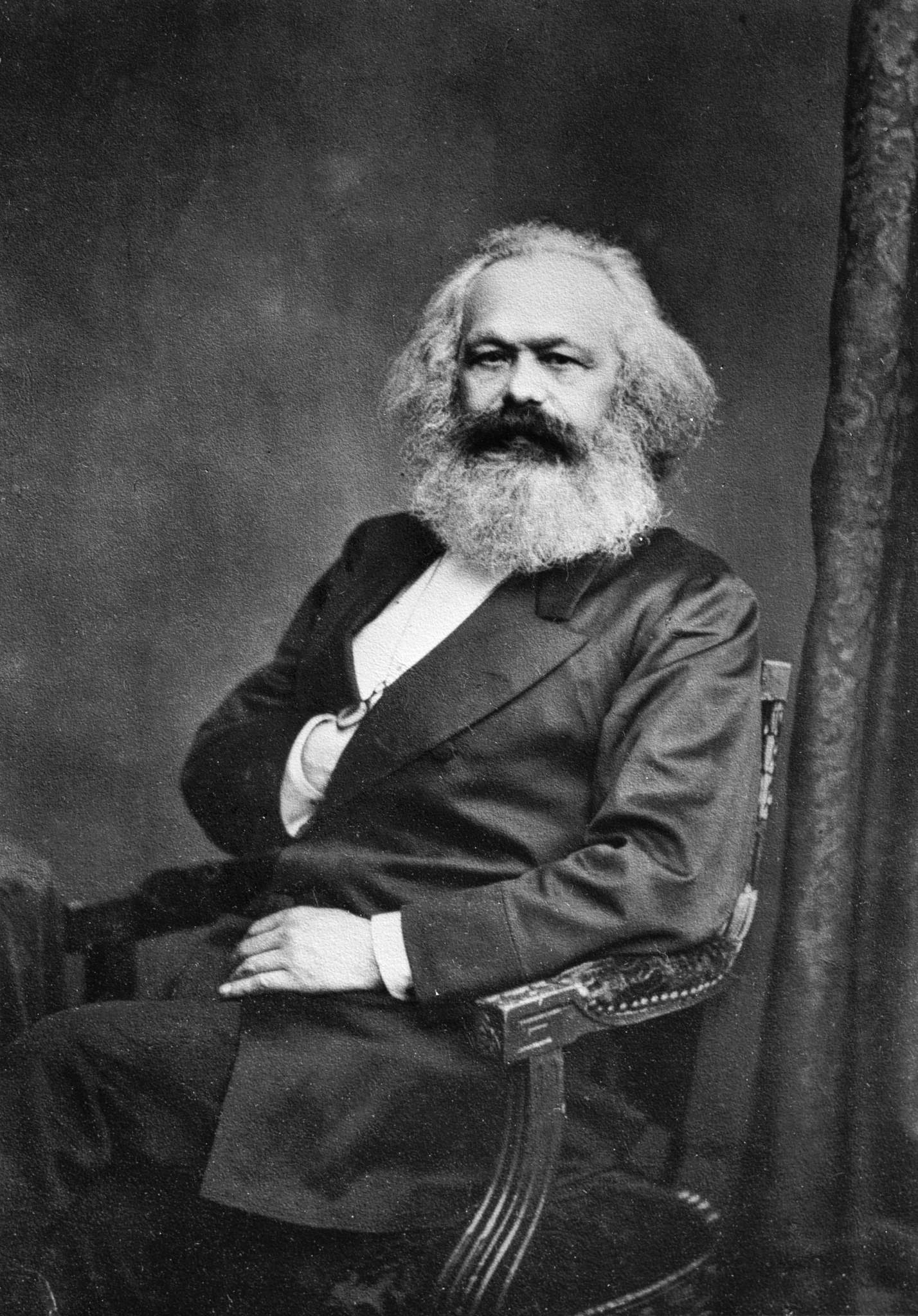

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

. Early currents of libertarian Marxism such as left communism emerged in opposition to Marxism–Leninism.The Civil War in France

"The Civil War in France" (German: "Der Bürgerkrieg in Frankreich") was a pamphlet written by Karl Marx, as an official statement of the General Council of the International on the character and significance of the struggle of the Communards in t ...

''; emphasizing the Marxist belief in the ability of the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

to forge its own destiny without the need for state or vanguard party to mediate or aid its liberation. Along with anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

, libertarian Marxism is one of the main currents of libertarian socialism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (201 ...

.

Libertarian Marxism includes currents such as autonomism

Autonomism, also known as autonomist Marxism is an anti-capitalist left-wing political and social movement and theory. As a theoretical system, it first emerged in Italy in the 1960s from workerism (). Later, post-Marxist and anarchist tendenc ...

, council communism, De Leonism, Lettrism, parts of the New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights, environmentalism, feminism, gay rights, g ...

, Situationism

The Situationist International (SI) was an international organization of social revolutionaries made up of avant-garde artists, intellectuals, and political theorists. It was prominent in Europe from its formation in 1957 to its dissolution ...

, Freudo-Marxism

Freudo-Marxism is a loose designation for philosophical perspectives informed by both the Marxist philosophy of Karl Marx and the psychoanalytic theory of Sigmund Freud. It has a rich history within continental philosophy, beginning in the 19 ...

(a form of psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek: + . is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques"What is psychoanalysis? Of course, one is supposed to answer that it is many things — a theory, a research method, a therapy, a body of knowledge. In what might b ...

), Socialisme ou Barbarie and workerism

Workerism is a political theory that emphasizes the importance of or glorifies the working class. Workerism, or , was of particular significance in Italian left-wing politics.

As revolutionary praxis

Workerism (or ) is a political analysis, w ...

.post-left

Contemporary anarchism within the history of anarchism is the period of the anarchist movement continuing from the end of World War II and into the present. Since the last third of the 20th century, anarchists have been involved in anti-globalisat ...

and social anarchists

Social anarchism is the branch of anarchism that sees individual freedom as interrelated with mutual aid.Suissa, Judith (2001). "Anarchism, Utopias and Philosophy of Education". ''Journal of Philosophy of Education'' 35 (4). pp. 627–646. . S ...

. Notable theorists of libertarian Marxism have included Maurice Brinton

Christopher Agamemnon Pallis (2 December 1923, in Bombay – 10 March 2005, in London) was an Anglo-Greek neurologist and libertarian socialist intellectual. Under the pen-names Martin Grainger and Maurice Brinton, he wrote and translated for th ...

,Guy Debord

Guy-Ernest Debord (; ; 28 December 1931 – 30 November 1994) was a French Marxist theorist, philosopher, filmmaker, critic of work, member of the Letterist International, founder of a Letterist faction, and founding member of the Situationis ...

, Raya Dunayevskaya,Daniel Guérin

Daniel Guérin (; 19 May 1904, in Paris – 14 April 1988, in Suresnes) was a French libertarian-communist author, best known for his work '' Anarchism: From Theory to Practice'', as well as his collection ''No Gods No Masters: An Anthology of ...

, C. L. R. James,Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialist, Marxist philosopher and anti-war activist. Successively, she was a member of the Proletariat party, ...

, Antonio Negri, Antonie Pannekoek, Fredy Perlman, Ernesto Screpanti

Ernesto Screpanti (born 1948, in Rome) is a professor of Political Economy at the University of Siena. He worked on the “rethinking Marxism” research programme, in the attempt to update Marxist analysis by bringing it in line with the reality o ...

, E. P. Thompson

Edward Palmer Thompson (3 February 1924 – 28 August 1993) was an English historian, writer, socialist and peace campaigner. He is best known today for his historical work on the radical movements in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, in ...

, Raoul Vaneigem, and Yanis Varoufakis, the latter claiming that Marx himself was a libertarian Marxist.

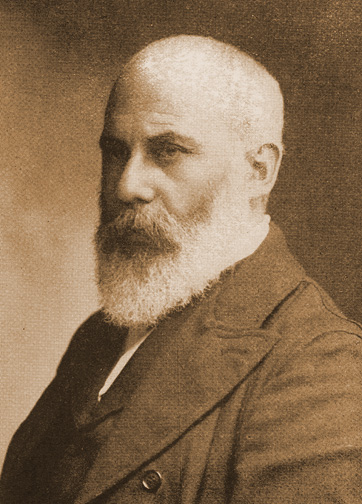

Austro-Marxism

Austro-Marxism was a school of Marxist thought centered in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

that existed from the beginning of the 20th century until the 1930s. Its most eminent proponents were Max Adler, Otto Bauer, Rudolf Hilferding and Karl Renner

Karl Renner (14 December 1870 – 31 December 1950) was an Austrian politician and jurist of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria. He is often referred to as the "Father of the Republic" because he led the first government of German-A ...

.positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. G ...

in philosophy and the emergence of marginalism

Marginalism is a theory of economics that attempts to explain the discrepancy in the value of goods and services by reference to their secondary, or marginal, utility. It states that the reason why the price of diamonds is higher than that of wa ...

in economics.National Question

''National question'' is a term used for a variety of issues related to nationalism. It is seen especially often in socialist thought and doctrine.

In socialism

* ''Social Democracy and the National Question'' by Vladimir Medem in 1904

* ''So ...

within the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

,

Left communism

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices espoused by Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions which they regard as more authentically Marxist than the views of Marxism–Leninism espoused by the Communist International after its Bolshevisation

Bolshevization was the process starting in the mid-1920s by which the pluralistic Communist International (Comintern) and its constituent communist parties were increasingly subject to pressure by the Kremlin in Moscow to follow Marxism–Leninism ...

by Joseph Stalin and during its second congress.World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in organizations like the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, ...

and the Communist Party of Italy

The Italian Communist Party ( it, Partito Comunista Italiano, PCI) was a communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current ...

. The Italian left considers itself to be Leninist in nature, but denounces Marxism–Leninism as a form of bourgeois opportunism

Opportunism is the practice of taking advantage of circumstances – with little regard for principles or with what the consequences are for others. Opportunist actions are expedient actions guided primarily by self-interested motives. The term ...

materialized in the Soviet Union under Stalin

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. The Italian left is currently embodied in organizations such as the Internationalist Communist Party Internationalist Communist Party may refer to:

* Internationalist Communist Party (France)

The Internationalist Communist Party (french: Parti Communiste Internationaliste, PCI) was a Trotskyist political party in France. It was the name taken ...

and the International Communist Party. The Dutch–German left split from Lenin prior to Stalin's rule and supports a firmly council communist and libertarian Marxist viewpoint as opposed to the Italian left which emphasised the need for an international revolutionary party.

Although she lived before left communism became a distinct tendency, Luxemburg has been heavily influential for most left communists, both politically and theoretically. Proponents of left communism have included Herman Gorter, Antonie Pannekoek, Otto Rühle

Karl Heinrich Otto Rühle (23 October 1874 – 24 June 1943) was a German Marxist active in opposition to both the First and Second World Wars as well as a council communist theorist.

Early years

Otto was born in Großschirma, Saxony on 23 Octo ...

, Karl Korsch

Karl Korsch (; August 15, 1886 – October 21, 1961) was a German Marxist theoretician and political philosopher. Along with György Lukács, Korsch is considered to be one of the major figures responsible for laying the groundwork for Western ...

, Amadeo Bordiga and Paul Mattick.International Communist Current

The International Communist Current (ICC) is a left communist international organisation. It was founded at a conference in January 1975 where it was established as a centralised organisation with sections in France, Britain, Spain, USA, Italy, a ...

and the Internationalist Communist Tendency. Specific currents that can be labelled part of left communism include Bordigism and Luxemburgism

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialist, Marxist philosopher and anti-war activist. Successively, she was a member of the Proletariat party, ...

.

Ultra-leftism

The term ultra-leftism in English, when used among Marxist groups, is often a pejorative for certain types of positions on the far-left

Far-left politics, also known as the radical left or the extreme left, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single definition. Some scholars consider ...

that are extreme or uncompromising, such as a particular current of Marxist communism, where the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

rejected social democratic parties and all other progressive groupings outside of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The French , has a stronger meaning in that language and is used to define a movement that still exists today: a branch of left communism developed from theorists such as Bordiga, Rühle, Pannekoek, Gorter, and Mattick, and continuing with more recent writers, such as Jacques Camatte

Jacques Camatte (born 1935) is a French writer and former Marxist theoretician and member of the International Communist Party, a primarily Italian left communist organisation under the influence of Amadeo Bordiga. After Bordiga's death and ...

and Gilles Dauvé

Gilles Dauvé (pen name Jean Barrot; born 1947) is a French political theorist, school teacher, and translator associated with left communism and the contemporary tendency of communization.

Biography

In collaboration with other left communists ...

. This standpoint includes two main traditions, a Dutch-German tradition including Rühle, Pannekoek, Gorter, and Mattick, and an Italian tradition following Bordiga. These traditions came together in the 1960s French .

Autonomism

Autonomism is a Marxist-based

Autonomism is a Marxist-based anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and Political movement, movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. In this sense, anti-capitalists are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economi ...

left-wing political and social movement and theory. As a theoretical system, it first emerged in Italy in the 1960s from workerism (). Later, post-Marxist

Post-Marxism is a trend in political philosophy and social theory which deconstructs Karl Marx's writings and Marxism itself, bypassing orthodox Marxism. The term "post-Marxism" first appeared in Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe's theoretica ...

and anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

tendencies became significant after influence from the Situationists

The Situationist International (SI) was an international organization of social revolutionaries made up of avant-garde artists, intellectuals, and political theorists. It was prominent in Europe from its formation in 1957 to its dissolution ...

, the failure of Italian far-left

Far-left politics, also known as the radical left or the extreme left, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single definition. Some scholars consider ...

movements in the 1970s, and the emergence of a number of important theorists including Antonio Negri,Mario Tronti

Mario Tronti (born 24 July 1931 in Rome) is an Italian philosopher and politician, considered one of the founders of the theory of operaismo in the 1960s.

An active member of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) during the 1950s, he was, with Ranie ...

, Paolo Virno

Paolo Virno (; ; born 1952) is an Italian philosopher, Semiotics, semiologist and a figurehead for the Italian Marxism, Marxist movement. Implicated in belonging to illegal social movements during the 1960s and 1970s, Virno was arrested and jail ...

, Sergio Bologna

Sergio may refer to:

* Sergio (given name), for people with the given name Sergio

* Sergio (carbonado), the largest rough diamond ever found

* ''Sergio'' (album), a 1994 album by Sergio Blass

* ''Sergio'' (2009 film), a documentary film

* ''Se ...

and Franco "Bifo" Berardi. These early theorists developed notions of "immaterial" and "social labour", which broaden the definition of the working-class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

to include salaried and unpaid labour, such as skilled professions and housework, this extended the Marxist concept of labour to all society. They suggested that modern society's wealth was produced by unaccountable collective

A collective is a group of entities that share or are motivated by at least one common issue or interest, or work together to achieve a common objective. Collectives can differ from cooperatives in that they are not necessarily focused upon an ...

work, which in advanced capitalist states as the primary force of change in the construct of capital, and that only a little of this was redistributed to the workers in the form of wages. Other theorists including Mariarosa Dalla Costa

Mariarosa Dalla Costa (born 1943 in Treviso) is an Italian autonomist feminist and co-author of the classic ''The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community'', with Selma James. This text launched the "domestic labour debate" by re-defining ...

and Silvia Federici emphasised the importance of feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

and the value of unpaid female labour to capitalist society, adding these to the theory of Autonomism. Negri and Michael Hardt argue that network power constructs are the most effective methods of organization against the neoliberal regime of accumulation and predict a massive shift in the dynamics of capital into a 21st century empire. Harry Cleaver is an autonomist and Marxist theoretician, who authored ''Reading Capital Politically'', an autonomist reading of Marx's ''Capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

''.

Western Marxism

Western Marxism is a current of

Western Marxism is a current of Marxist theory

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew fro ...

that arose from Western and Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

in the aftermath of the 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

and the ascent of Leninism. The term denotes a loose collection of Marxist theorists who emphasize culture, philosophy, and art, in contrast to the Marxism of the Soviet Union.Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Francesco Gramsci ( , , ; 22 January 1891 – 27 April 1937) was an Italian Marxist philosopher, journalist, linguist, writer, and politician. He wrote on philosophy, political theory, sociology, history, and linguistics. He was a ...

, Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse (; ; July 19, 1898 – July 29, 1979) was a German-American philosopher, social critic, and political theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. Born in Berlin, Marcuse studied at the Humboldt University ...

, Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and litera ...

, Louis Althusser

Louis Pierre Althusser (, ; ; 16 October 1918 – 22 October 1990) was a French Marxist philosopher. He was born in Algeria and studied at the École normale supérieure in Paris, where he eventually became Professor of Philosophy.

Althusser ...

, and the members of the Frankfurt School

The Frankfurt School (german: Frankfurter Schule) is a school of social theory and critical philosophy associated with the Institute for Social Research, at Goethe University Frankfurt in 1929. Founded in the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), dur ...

.

Eurocommunism

Eurocommunism was a revisionist trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more relevant for western Europe. During the Cold War, they sought to undermine the influence of the Soviet Union and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in western Europe. It was especially prominent in France, Italy and Spain.

Since the early 1970s, the term Eurocommunism was used to refer to the ideology of moderate, reformist communist parties in western Europe, where they emphasised the importance of democracy and personal freedoms. These parties did not support the Soviet Union and denounced its policies. Such parties were politically active and electorally significant in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

.

Luxemburgism

Luxemburgism is a specific revolutionary theory within Marxism and communism-based on the writings of Rosa Luxemburg. Luxemburg was critical of undemocratic tendencies present in the Leninist schools of thought as well as being critical of the reformist Marxism that emerged from the work of

Luxemburgism is a specific revolutionary theory within Marxism and communism-based on the writings of Rosa Luxemburg. Luxemburg was critical of undemocratic tendencies present in the Leninist schools of thought as well as being critical of the reformist Marxism that emerged from the work of Eduard Bernstein

Eduard Bernstein (; 6 January 1850 – 18 December 1932) was a German social democratic Marxist theorist and politician. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), Bernstein had held close association to Karl Marx and Friedric ...

's informal faction of the Social Democratic Party of Germany. According to Rosa Luxemburg, under reformism " apitalismis not overthrown, but is on the contrary strengthened by the development of social reforms". Luxemburgism sees spontaneism

Revolutionary spontaneity, also known as spontaneism, is a revolutionary socialist tendency that believes the social revolution can and should occur spontaneously from below by the working class itself, without the aid or guidance of a vanguar ...

as a natural and important force, where organisation is not a product of scientific-theoretic insight to historical imperatives, but is product of the working classes' struggles, which emerges response to mounting contradictions between the productive forces and social relations of society. This was built from Luxemburg's analysis of mass strikes seen in Germany and Russia in the early 20th century. Though she also wrote of the failings in trade unionism at the time due to the conservative function of trade-union bureaucracy hampering trade-unionist socialist potential. Ernest Mandel, a Marxian economist, has been characterised as ''Luxemburgist'' due to his commitment to socialist democracy.

Council communism

Council communism is a movement originating from Germany and the Netherlands in the 1920s. The Communist Workers Party of Germany

The Communist Workers' Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Arbeiter-Partei Deutschlands; KAPD) was an anti-parliamentarian and left communist party that was active in Germany during the time of the Weimar Republic. It was founded in April 1 ...

(KAPD) was the primary organization that espoused council communism. Council communism continues today as a theoretical and activist position within both Marxism and libertarian socialism, through a few groups in Europe and North America. As such, it is referred to as anti-authoritarian and anti-Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishme ...

Marxism.

In contrast to reformist social democracy and to Leninism, the central argument of council communism is that democratic workers councils arising in factories and municipalities are the natural form of working class organisation and governmental power. The government and the economy should be managed by workers' councils composed of delegates elected at workplaces and recallable at any moment. As such, council communists oppose authoritarian socialism

Authoritarian socialism, or socialism from above, is an economic and political system supporting some form of socialist economics while rejecting political liberalism. As a term, it represents a set of economic-political systems describing themse ...

, and command economies

A planned economy is a type of economic system where Investment (macroeconomics), investment, Production (economics), production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A plan ...

such as state socialism and state capitalism. They also oppose the idea of a revolutionary party since council communists believe that a party-led revolution will necessarily produce a party dictatorship. This view is also opposed to the social democratic and Marxist–Leninist ideologies, with their stress on parliaments and institutional government (i.e. by applying social reforms) on the one hand and vanguard parties and participative democratic centralism on the other. Council communists see the mass strike and new yet to emerge forms of mass action as revolutionary means to achieve a communist society.

De Leonism

De Leonism is a form of Marxism developed by the American activist Daniel De Leon. De Leon was an early leader of the first socialist political party in the United States, the

De Leonism is a form of Marxism developed by the American activist Daniel De Leon. De Leon was an early leader of the first socialist political party in the United States, the Socialist Labor Party of America

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1924 ...

. De Leon combined the rising theories of syndicalism in his time with orthodox Marxism.industrial unionism

Industrial unionism is a trade union organizing method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in ...

, and that the political efforts of a workers party should be subservient to the industrial action of the union.democratic socialist

Democratic socialism is a left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-management within a ...

movements—especially the Socialist Party of America

The Socialist Party of America (SPA) was a socialist political party in the United States formed in 1901 by a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of Ameri ...

—and consider them to be reformist or bourgeois socialist. De Leonism spread with the idea of industrial unionism to various countries including Ireland (via James Connolly), the UK, and South Africa.

De Leonists have traditionally refrained from any activity or alliances viewed by them as trying to reform capitalism,

Situationism

The Situationist International was an international organization of social revolutionaries made up of avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

artists, intellectuals, and political theorists. It was prominent in Europe from its formation in 1957 to its dissolution in 1972.libertarian Marxism

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (2 ...

and the avant-garde art movement

An art movement is a tendency or style in art with a specific common philosophy or goal, followed by a group of artists during a specific period of time, (usually a few months, years or decades) or, at least, with the heyday of the movement defin ...

s of the early 20th century, particularly Dada and Surrealism

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to l ...

.advanced capitalism

In political philosophy, particularly Frankfurt School critical theory, advanced capitalism is the situation that pertains in a society in which the capitalist model has been integrated and developed deeply and extensively and for a prolonged p ...

.social relation

A social relation or also described as a social interaction or social experience is the fundamental unit of analysis within the social sciences, and describes any voluntary or involuntary interpersonal relationship between two or more individuals ...

s through objects

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an ...

.commodities

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

The price of a comm ...

, or passive second-hand alienation,theory of alienation

Karl Marx's theory of alienation describes the estrangement (German: ''Entfremdung'') of people from aspects of their human nature (''Gattungswesen'', 'species-essence') as a consequence of the division of labor and living in a society of strat ...

.

Impossibilism

Impossibilism is a Marxist theory that stresses the limited value of political, economic, and social reforms under capitalism. As a doctrine, impossibilism views the pursuit of such reforms as counterproductive to the goal of achieving socialism as they stabilize, and therefore strengthen, support for capitalism. Impossibilism holds that reforms to capitalism are irrelevant or outright counter-productive to the goal of achieving socialism and should not be a major focus of socialist politics.

Impossibilists insist that socialists should primarily or solely focus on structural changes (sometimes termed "revolutionary changes") to society as opposed to advancing social reforms. Impossibilists argue that spontaneous revolutionary action is the only viable method of instituting the structural changes necessary for the construction of socialism; impossibilism is thus held in contrast to reformist socialist parties that aim to rally support for socialism through the implementation of popular social reforms (such as a welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equitabl ...

).social democratic

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote soci ...

political party, as well as being held in contrast to possibilism, where socialists who followed possibilism sounded and acted little different from non-socialist reformers in practice.

Marxist feminism

Marxist feminism is a philosophical variant of feminism that incorporates and extends Marxist theory, focusing on the dismantling of capitalism as a way to liberate women. Marxist feminism analyzes the ways in which women are exploited through capitalism and the individual ownership of private property,

Marxist feminism is a philosophical variant of feminism that incorporates and extends Marxist theory, focusing on the dismantling of capitalism as a way to liberate women. Marxist feminism analyzes the ways in which women are exploited through capitalism and the individual ownership of private property,economic inequality

There are wide varieties of economic inequality, most notably income inequality measured using the distribution of income (the amount of money people are paid) and wealth inequality measured using the distribution of wealth (the amount of we ...

as well as dependence, political confusion and ultimately unhealthy social relations between men and women, which are the root of women's oppression. According to Marxist feminists, women's liberation

The women's liberation movement (WLM) was a political alignment of women and feminist intellectualism that emerged in the late 1960s and continued into the 1980s primarily in the industrialized nations of the Western world, which effected great ...

can only be achieved by dismantling the capitalist systems in which they contend much of women's labor is uncompensated.class oppression

Oppression is malicious or unjust treatment or exercise of power, often under the guise of governmental authority or cultural opprobrium. Oppression may be overt or covert, depending on how it is practiced. Oppression refers to discrimination wh ...

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

) because it serves the interests of capital and the ruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society. In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the capitalist social class who own the means of production and by exten ...

.materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materiali ...

, Marxist feminism is similar to socialist feminism and, to a greater degree, materialist feminism

Materialist feminism highlights capitalism and patriarchy as a central aspect in understanding women's oppression. It focuses on the material, or physical, aspects that define oppression. Under materialist feminism, gender is seen as a social cons ...

. The latter two place greater emphasis on what they consider the "reductionist limitations"

Marxist humanism

Marxist humanism is an international body of thought and political action rooted in an interpretation of Marx's earlier writings. It is an investigation into "what human nature consists of and what sort of society would be most conducive to human thriving" from a critical perspective rooted in Marxist philosophy

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew fro ...

. Marxist humanists argue that Marx himself was concerned with investigating similar questions.

Marxist humanism was born in 1932 with the publication of Marx's '' Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844'' and reached a degree of prominence in the 1950s and 1960s. Marxist humanists contend that there is continuity between the early philosophical writings of Marx, in which he develops his theory of alienation

Karl Marx's theory of alienation describes the estrangement (German: ''Entfremdung'') of people from aspects of their human nature (''Gattungswesen'', 'species-essence') as a consequence of the division of labor and living in a society of strat ...

, and the structural description of capitalist society found in his later works such as . They hold that it is necessary to grasp Marx's philosophical foundations to understand his later works properly. Marxist humanism was opposed by Louis Althusser's "antihumanism

In social theory and philosophy, antihumanism or anti-humanism is a theory that is critical of traditional humanism, traditional ideas about humanity and the human condition. Central to antihumanism is the view that philosophical anthropology an ...

", who qualified it as a revisionist movement.

Non-Marxist communism

The most widely held forms of communist theory are derived from Marxism, but non-Marxist versions of communism also exist.

Primitive communism

Primitive communism is a way of describing the gift economies

A gift economy or gift culture is a system of exchange where valuables are not sold, but rather given without an explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards. Social norms and customs govern giving a gift in a gift culture; although there ...

of hunter-gatherers throughout history, where resources and property hunted and gathered are shared with all members of a group, in accordance with individual needs. In political sociology and anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

, it is also a concept often credited to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels for originating, who wrote that hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

societies were traditionally based on egalitarian social relations and common ownership. A primary inspiration for both Marx and Engels were Morgan Morgan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Morgan (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Morgan le Fay, a powerful witch in Arthurian legend

* Morgan (surname), a surname of Welsh origin

* Morgan (singer), ...

's descriptions of "communism in living" as practised by the Haudenosaunee

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

of North America. In Marx's model of socioeconomic structures, societies with primitive communism had no hierarchical social class structures or capital accumulation

Capital accumulation is the dynamic that motivates the pursuit of profit, involving the investment of money or any financial asset with the goal of increasing the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the form o ...

.

Anarcho-communism

Some of Marx's contemporaries espoused similar ideas, but differed in their views of how to reach to a classless society. Following the split between those associated with Marx and Mikhail Bakunin at the First International, the anarchists formed the International Workers Association. Anarchists argued that capitalism and the state were inseparable and that one could not be abolished without the other. Anarcho-communists such as

Some of Marx's contemporaries espoused similar ideas, but differed in their views of how to reach to a classless society. Following the split between those associated with Marx and Mikhail Bakunin at the First International, the anarchists formed the International Workers Association. Anarchists argued that capitalism and the state were inseparable and that one could not be abolished without the other. Anarcho-communists such as Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (; russian: link=no, Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин ; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist, socialist, revolutionary, historian, scientist, philosopher, and activis ...

theorized an immediate transition to one society with no classes. Anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in b ...

, similar to anarcho-communism, became one of the dominant forms of anarchist organization, arguing that labor unions are the organizations that can change society as opposed to communist parties. Consequently, many anarchists have been in opposition to Marxist communism to this day. Important theorists to anarcho-communism include Alexander Berkman, Murray Bookchin

Murray Bookchin (January 14, 1921 – July 30, 2006) was an American social theorist, author, orator, historian, and political philosopher. A pioneer in the environmental movement, Bookchin formulated and developed the theory of social ec ...

, Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is ...

, Errico Malatesta

Errico Malatesta (4 December 1853 – 22 July 1932) was an Italian anarchist propagandist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expelled from ...

, Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

, Ricardo Flores Magón

Cipriano Ricardo Flores Magón (, known as Ricardo Flores Magón; September 16, 1874 – November 21, 1922) was a noted Mexican anarchist and social reform activist. His brothers Enrique and Jesús were also active in politics. Followers of ...

, and Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

. Three prominent organizational forms seen in anarcho-communism are insurrectionary anarchism

Insurrectionary anarchism is a revolutionary theory and tendency within the anarchist movement that emphasizes insurrection as a revolutionary practice. It is critical of formal organizations such as labor unions and federations that are based o ...

, platformism,

Communist Bundism

Bundism was a secular

Bundism was a secular Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

socialist movement whose organizational manifestation was the General Jewish Labour Bund in Lithuania, Poland and Russia ( yi, אַלגעמײַנער ײדישער אַרבעטער בּונד אין ליטע פוילין און רוסלאַנד, Algemeyner Yidisher Arbeter Bund in Liteh, Poyln un Rusland), founded in the Russian Empire in 1897. The Jewish Labour Bund was an important component of the social democratic movement in the Russian Empire until the 1917 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

; the Bundists initially opposed the October Revolution, but ended up supporting it due to pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s committed by the Volunteer Army

The Volunteer Army (russian: Добровольческая армия, translit=Dobrovolcheskaya armiya, abbreviated to russian: Добрармия, translit=Dobrarmiya) was a White Army active in South Russia during the Russian Civil War from ...

of the anti-communist White movement during the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

. Split along communist and social democratic lines throughout the Civil War, where the communist faction supported the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

,Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

was a form of escapism. Bundism focused on culture, rather than a state or a place, as the glue of Jewish "nationalism." In this they borrowed extensively from the Austro-Marxist

Austromarxism (also stylised as Austro-Marxism) was a Marxist theoretical current, led by Victor Adler, Otto Bauer, Karl Renner, Max Adler and Rudolf Hilferding, members of the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria in Austria-Hungary ...

school. It also promoted the use of Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

as a Jewish national language and to some extent opposed the Zionist project of reviving Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

.

Religious communism

Religious communism is a form of communism that incorporates religious principles. Scholars have used the term to describe a variety of social or religious movements throughout history that have favored the common ownership of property.

Christian communism

Christian communism is a form of religious communism centered on Christianity. It is a theological and political theory based upon the view that the teachings of Jesus Christ urge Christians to support communism as the ideal social system.New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

, such as this one from Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its messag ...

at chapter 2 and verses 42, 44 and 45:42. And they continued steadfastly in the apostles' doctrine and in fellowship ..44. And all that believed were together, and had all things in common; 45. And sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need. (King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an Bible translations into English, English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and publis ...

)

Christian communism can be seen as a radical form of Christian socialism

Christian socialism is a religious and political philosophy that blends Christianity and socialism, endorsing left-wing politics and socialist economics on the basis of the Bible and the teachings of Jesus. Many Christian socialists believe capi ...

and because many Christian communists have formed independent stateless communes in the past, there is also a link between Christian communism and Christian anarchism

Christian anarchism is a Christian movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels. It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately answ ...

. Christian communists may or may not agree with various parts of Marxism. Christian communists also share some of the political goals of Marxists, for example replacing capitalism with socialism, which should in turn be followed by communism at a later point in the future. However, Christian communists sometimes disagree with Marxists (and particularly with Leninists) on the way a socialist or communist society should be organized.

Various communistic Christian communities and movements have included the Dulcinians

{{no footnotes, date=July 2018

The Dulcinians were a religious sect of the Late Middle Ages, originating within the Apostolic Brethren. The Dulcinians, or Dulcinites, and Apostolics were inspired by Franciscan ideals and influenced by the Joachimi ...

led by Fra Dolcino

Fra Dolcino (c. 1250 – 1307) was the second leader of the Dulcinian reformist movement who was burned at the stake in Northern Italy in 1307. He had taken over the movement after its founder, Gerard Segarelli, had also been executed in 1300 on ...

,Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from New Latin language, Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re- ...

communist movement led by Thomas Müntzer during the German Peasants' War

The German Peasants' War, Great Peasants' War or Great Peasants' Revolt (german: Deutscher Bauernkrieg) was a widespread popular revolt in some German-speaking areas in Central Europe from 1524 to 1525. It failed because of intense oppositio ...

, the Diggers

The Diggers were a group of religious and political dissidents in England, associated with agrarian socialism. Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard, amongst many others, were known as True Levellers in 1649, in reference to their split from ...

and the Levellers

The Levellers were a political movement active during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms who were committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law and religious tolerance. The hallmark of Leveller thought was its populis ...

of the English Civil War, and the Shakers

The United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly known as the Shakers, are a Millenarianism, millenarian Restorationism, restorationist Christianity, Christian sect founded in England and then organized in the Unit ...

of the 18th century.

Islamic communism

Researchers have commented on the communistic nature of the society built by the Qarmatians

The Qarmatians ( ar, قرامطة, Qarāmiṭa; ) were a militant Isma'ilism, Isma'ili Shia Islam, Shia movement centred in Al-Ahsa Oasis, al-Hasa in Eastern Arabia, where they established a Utopia#Religious utopias, religious-utopian Socialis ...

around Al-Ahsa from the 9th to 10th centuries.

Islamic Marxism attempts to apply Marxist economic, political, and social teachings within an Islamic framework. An affinity between Marxist and Islamic ideals of social justice has led some Muslims to embrace their own forms of Marxism since the 1940s. Islamic Marxists believe that Islam meets the needs of society and can accommodate or guide the social changes Marxism hopes to accomplish. Islamic Marxists are also dismissive of traditional Marxist views on materialism and religion.

Neozapatismo

Neozapatismo is generally held to be based on anarchism,

Neozapatismo is generally held to be based on anarchism, Mayan

Mayan most commonly refers to:

* Maya peoples, various indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica and northern Central America

* Maya civilization, pre-Columbian culture of Mesoamerica and northern Central America

* Mayan languages, language family spoken ...

tradition, Marxism, the thoughts of Emiliano Zapata, and the thoughts of Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano. Neozapatismo has been influenced by libertarian socialism, libertarian Marxism (including autonomism), social-anarchism, anarcho-communism, anarcho-collectivism

Collectivist anarchism, also called anarchist collectivism and anarcho-collectivism, Buckley, A. M. (2011). ''Anarchism''. Essential Libraryp. 97 "Collectivist anarchism, also called anarcho-collectivism, arose after mutualism." . is an anarchis ...

, anarcho-syndicalism, communalism

Communalism may refer to:

* Communalism (Bookchin), a theory of government in which autonomous communities form confederations

* , a historical method that follows the development of communities

* Communalism (South Asia), violence across ethnic ...

, direct democracy

Direct democracy or pure democracy is a form of democracy in which the Election#Electorate, electorate decides on policy initiatives without legislator, elected representatives as proxies. This differs from the majority of currently establishe ...

, and radical democracy.

Subcomandante Marcos has offered some clues as to the origins of neozapatismo. For example, he states:

Zapatismo was not Marxist-Leninist, but it was also Marxist-Leninist. It was not university Marxism, it was not the Marxism of concrete analysis, it was not the history of Mexico, it was not the fundamentalist and millenarian indigenous thought and it was not the indigenous resistance. It was a mixture of all of this, a cocktail which was mixed in the mountain and crystallized in the combat force of the EZLN

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (, EZLN), often referred to as the Zapatistas (Mexican ), is a far-left political and militant group that controls a substantial amount of territory in Chiapas, the southernmost state of Mexico.

Since ...

…

In 1998, Michael Löwy

Michael Löwy (born 6 May 1938) is a French-Brazilian Marxist sociologist and philosopher. He is emeritus research director in social sciences at the CNRS (French National Center of Scientific Research) and lectures at the ''École des hautes ...

identified five “threads” of what he referred to as the Zapatismo “carpet”:

# Guevarism

# The legacy of Emiliano Zapata

# Liberation theology

# The Mayan culture

# The democratic demands made by Mexican civil society.

Juche

In 1992, Juche replaced Marxism-Leninism in the revised North Korean constitution as the official state ideology. Juche is claimed to be based on Marxism-Leninism, with

In 1992, Juche replaced Marxism-Leninism in the revised North Korean constitution as the official state ideology. Juche is claimed to be based on Marxism-Leninism, with Kim Jong-il

Kim Jong-il (; ; ; born Yuri Irsenovich Kim;, 16 February 1941 – 17 December 2011) was a North Korean politician who was the second supreme leader of North Korea from 1994 to 2011. He led North Korea from the 1994 death of his father Kim ...

stating, "the world outlook of the materialistic dialectics is the premise for the Juche philosophy." Though many critics point out the lack of Marxist-Leninist theory within the writings and practice of Juche in North Korea. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

in 1991 (North Korea's greatest economic benefactor), all reference to Marxism-Leninism was dropped in the revised 1992 constitution.military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

, not the proletariat or working class, as the main revolutionary force in North Korea.self-sufficiency

Self-sustainability and self-sufficiency are overlapping states of being in which a person or organization needs little or no help from, or interaction with, others. Self-sufficiency entails the self being enough (to fulfill needs), and a self-s ...

, and self-reliance in defense.

# Policy must reflect the will and aspirations of the masses and employ them fully in revolution and construction.

# Methods of revolution and construction must be suitable to the situation of the country.

# The most important work of revolution and construction is molding people ideologically as communists and mobilizing them to constructive action.

Nkrumaism

Nkrumaism is a pan-African socialist theory which aims to adapt Marxist–Leninist theory to the social context of the African continent

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. Nkrumah defined his belief system as "the ideology of a New Africa, independent and absolutely free from imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

, organized on a continental scale, founded upon the conception of one and united Africa, drawing its strength from modern science and technology and from the traditional African belief that the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all." Important influences on Nkrumah's work were different sources from within Africa, the canon of Western philosophy, the works of Marx, Lenin, and black intellectuals in North America and Europe, like Marcus Garvey, George Padmore, C. L. R. James, W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

and Father Divine. Aside from the Marxist–Leninist framework, this blending of ideas largely only took bits and pieces of other philosophical systems and even its use of traditional African cultural concepts were often stretched to fit into the larger theory. While a major focus of the ideology was ending colonial relationships on the African continent, many of the ideas were utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', describing a fictional ...

n, diverting the scientific nature of the Marxist political analysis which it claims to support.

Like other African political ideologies at the time, the central focus of Nkrumaism was on decolonization across Africa. Nkrumah rejected the idealized view of pre-colonial African societies that were classless or non-hierarchical, but accepted that Africa had a spirit of communalism and humanism. Nkrumaism then argued that a return to these values through socialist political structures would both heal the disruption caused by colonial structures and allow further development of African societies. The pan-African aspects of Nkrumah's ideology were justified by a claim that all African societies had a community of economic life and that in contradiction to the neocolonial

Neocolonialism is the continuation or reimposition of imperialist rule by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony). Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, gl ...

structures that replaced formal colonies, only African unity would create real autonomy. While Nkrumah believed in the materialism and economic determinism of Marxism, he argued that focusing on the economic system was only appropriate after achieving independence throughout Africa and that the political struggle was the first order in colonial and neocolonial contexts.

New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and state (polity), states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

, environmentalism

Environmentalism or environmental rights is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement regarding concerns for environmental protection and improvement of the health of the environment, particularly as the measure for this health seek ...

, feminism, gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , 3 ...

, abortion rights, gender role

A gender role, also known as a sex role, is a social role encompassing a range of behaviors and attitudes that are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for a person based on that person's sex. Gender roles are usually cent ...

s, and drug policy reforms.labor union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

movements for social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals fu ...

that focused on dialectical materialism and social class, while others who used the term see the movement as a continuation and revitalization of traditional leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

goals.labor movement

The labour movement or labor movement consists of two main wings: the trade union movement (British English) or labor union movement (American English) on the one hand, and the political labour movement on the other.

* The trade union movement ...

and Marxism's historical theory of class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms ...

,Maoism

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Chi ...

) in the United States or the in the German-speaking world

This article details the geographical distribution of speakers of the German language, regardless of the legislative status within the countries where it is spoken. In addition to the German-speaking area (german: Deutscher Sprachraum) in Europe, ...

.

21st-Century Communist Theorists

According to the political theorist Alan Johnson, there has been a revival of serious interest in communism in the 21st century led by

According to the political theorist Alan Johnson, there has been a revival of serious interest in communism in the 21st century led by Slavoj Žižek

Slavoj Žižek (, ; ; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian philosopher, cultural theorist and public intellectual. He is international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London, visiting professor at New Y ...

and Alain Badiou

Alain Badiou (; ; born 17 January 1937) is a French philosopher, formerly chair of Philosophy at the École normale supérieure (ENS) and founder of the faculty of Philosophy of the Université de Paris VIII with Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucau ...

.Jodi Dean

Jodi Dean (born April 9, 1962) is an American political theorist and professor in the Political Science department at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in New York state. She held the Donald R. Harter ’39 Professorship of the Humanities and So ...

, Michael Lebowitz, and Paul Cockshott, as well as Alberto Toscano

Alberto Toscano (born 1 January 1977) is an Italian cultural critic, social theorist, philosopher, and translator. He has translated the work of Alain Badiou, including Badiou's ''The Century'' and ''Logics of Worlds''. He served as both editor ...

, translator of Alain Badiou, Terry Eagleton, Eduard Limonov, Bruno Bosteels __NOTOC__

Bruno Bosteels (; born 1967, Leuven, Belgium) is a professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. He served until 2010 as the General Editor of ''diacritics''. Bosteels is best known to the English-speaking worl ...

and Peter Hallward

Peter Hallward is a political philosopher, best known for his work on Alain Badiou and Gilles Deleuze. He has also published works on post-colonialism and contemporary Haiti. Hallward is a member of the editorial collective of the journal ''Radi ...

.Verso Books

Verso Books (formerly New Left Books) is a left-wing publishing house based in London and New York City, founded in 1970 by the staff of ''New Left Review''.

Renaming, new brand and logo

Verso Books was originally known as New Left Books. The ...

, include ''The Idea of Communism'', edited by Costas Douzinas Costas Douzinas ( el, Κώστας Δουζίνας; born 1951) is a professor of law, a founder of the Birkbeck School of Law and the Department of Law of the University of Cyprus, the founding director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities ...

and Žižek;[ Other non-communist thinkers and theorists have also had an effect on communist theory and the new generation of communists in the 21st century, such as the economist Guy Standing and the anthropologist and anarchist ]David Graeber

David Rolfe Graeber (; February 12, 1961September 2, 2020) was an American anthropologist and anarchist activist. His influential work in economic anthropology, particularly his books '' Debt: The First 5,000 Years'' (2011) and ''Bullshit Jobs ...

.

See also

* Anarchist schools of thought

Anarchism is the political philosophy which holds ruling classes and the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, The following sources cite anarchism as a political philosophy: Slevin, Carl. "Anarchism." ''The Concise Oxford Dicti ...

* Marxist schools of thought

Marxism is a method of socioeconomic analysis that originates in the works of 19th century German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Marxism analyzes and critiques the development of class society and especially of capitalism as well as ...

* National communism