LSM Operator on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

Uridine phosphate binds in archaeal Sm1 between the β2b/β3a loop and β4b/β5 loop. The

Uridine phosphate binds in archaeal Sm1 between the β2b/β3a loop and β4b/β5 loop. The

Pfam entry LSM. Pfam is the Sanger Institute database, which is a collection of protein families and domains.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lsm Protein families Spliceosome

molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physi ...

, LSm proteins are a family of RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

-binding protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s found in virtually every cellular organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

. LSm is a contraction of 'like Sm', because the first identified members of the LSm protein family

A protein family is a group of evolutionarily related proteins. In many cases, a protein family has a corresponding gene family, in which each gene encodes a corresponding protein with a 1:1 relationship. The term "protein family" should not be c ...

were the Sm proteins. LSm proteins are defined by a characteristic three-dimensional structure and their assembly into rings of six or seven individual LSm protein molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

s, and play a large number of various roles in mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

processing and regulation.

The Sm proteins were first discovered as antigens

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

targeted by so-called anti-Sm antibodies in a patient with a form of systemic lupus erythematosus

Lupus, technically known as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is an autoimmune disease in which the body's immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue in many parts of the body. Symptoms vary among people and may be mild to severe. Comm ...

(SLE), a debilitating autoimmune disease

An autoimmune disease is a condition arising from an abnormal immune response to a functioning body part. At least 80 types of autoimmune diseases have been identified, with some evidence suggesting that there may be more than 100 types. Nearly a ...

. They were named Sm proteins in honor of Stephanie Smith, a patient who suffered from SLE. Other proteins with very similar structures were subsequently discovered and named LSm proteins. New members of the LSm protein family continue to be identified and reported.

Proteins with similar structures are grouped into a hierarchy of protein families, superfamilies, and folds. The LSm protein structure is an example of a small beta sheet

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) (also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a g ...

folded into a short barrel. Individual LSm proteins assemble into a six or seven member doughnut ring (more properly termed a torus

In geometry, a torus (plural tori, colloquially donut or doughnut) is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space about an axis that is coplanar with the circle.

If the axis of revolution does not tou ...

), which usually binds to a small RNA

Small RNA (sRNA) are polymeric RNA molecules that are less than 200 nucleotides in length, and are usually non-coding

Non-coding DNA (ncDNA) sequences are components of an organism's DNA that do not encode protein sequences. Some non-coding DNA ...

molecule to form a ribonucleoprotein

Nucleoproteins are proteins conjugated with nucleic acids (either DNA or RNA). Typical nucleoproteins include ribosomes, nucleosomes and viral nucleocapsid proteins.

Structures

Nucleoproteins tend to be positively charged, facilitating in ...

complex. The LSm torus assists the RNA molecule to assume and maintain its proper three-dimensional structure. Depending on which LSm proteins and RNA molecule are involved, this ribonucleoprotein complex facilitates a wide variety of RNA processing including degradation, editing, splicing, and regulation.

Alternate terms for LSm family are LSm fold and Sm-like fold, and alternate capitalization styles such as lsm, LSM, and Lsm are common and equally acceptable.

History

Discovery of the Smith antigen

The story of the discovery of the first LSmprotein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s begins with a young woman, Stephanie Smith, who was diagnosed in 1959 with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Lupus, technically known as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is an autoimmune disease in which the body's immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue in many parts of the body. Symptoms vary among people and may be mild to severe. Comm ...

, eventually succumbing to complications of the disease in 1969 at the age of 22. During this period, she was treated at New York's Rockefeller University

The Rockefeller University is a private biomedical research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and provides doctoral and postdoctoral education. It is classif ...

Hospital, under the care of Dr. Henry Kunkel and Dr. Eng Tan. As those with an autoimmune disease

An autoimmune disease is a condition arising from an abnormal immune response to a functioning body part. At least 80 types of autoimmune diseases have been identified, with some evidence suggesting that there may be more than 100 types. Nearly a ...

, SLE patients produce antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

to antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

s in their cells' nuclei, most frequently to their own DNA. However, Dr. Kunkel and Dr. Tan found in 1966 that Ms. Smith produced antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

to a set of nuclear proteins, which they named the 'smith antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

' (Sm Ag). About 30% of SLE patients produce antibodies to these proteins, as opposed to double stranded DNA. This discovery improved diagnostic testing for SLE, but the nature and function of this antigen was unknown.

Sm proteins, snRNPs, the spliceosome and messenger RNA splicing

Research continued during the 1970s and early 1980s. The smith antigen was found to be a complex of ribonucleic acid (RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

) molecules and multiple proteins. A set of uridine

Uridine (symbol U or Urd) is a glycosylated pyrimidine analog containing uracil attached to a ribose ring (or more specifically, a ribofuranose) via a β-N1-glycosidic bond. The analog is one of the five standard nucleosides which make up nuclei ...

-rich small nuclear RNA

Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) is a class of small RNA molecules that are found within the splicing speckles and Cajal bodies of the cell nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The length of an average snRNA is approximately 150 nucleotides. They are transcribe ...

(snRNA) molecules was part of this complex, and given the names U1, U2, U4, U5 and U6. Four of these snRNAs (U1, U2, U4 and U5) were found to be tightly bound to several small proteins, which were named SmB, SmD, SmE, SmF, and SmG in decreasing order of size. SmB has an alternatively spliced variant, SmB', and a very similar protein, SmN, replaces SmB'/B in certain (mostly neural) tissues. SmD was later discovered to be a mixture of three proteins, which were named SmD1, SmD2 and SmD3. These nine proteins (SmB, SmB', SmN, SmD1, SmD2, SmD3, SmE, SmF and SmG) became known as the Sm core proteins, or simply Sm proteins. The snRNAs are complexed with the Sm core proteins and with other proteins to form particles in the cell's nucleus called small nuclear ribonucleoproteins, or snRNP

snRNPs (pronounced "snurps"), or small nuclear ribonucleoproteins, are RNA-protein complexes that combine with unmodified pre-mRNA and various other proteins to form a spliceosome, a large RNA-protein molecular complex upon which splicing of pre- ...

s. By the mid 1980s, it became clear that these snRNPs help form a large (4.8 MD molecular weight

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

) complex, called the spliceosome

A spliceosome is a large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex found primarily within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The spliceosome is assembled from small nuclear RNAs (snRNA) and numerous proteins. Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) molecules bind to specifi ...

, around pre-mRNA

A primary transcript is the single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) product synthesized by transcription of DNA, and processed to yield various mature RNA products such as mRNAs, tRNAs, and rRNAs. The primary transcripts designated to be mRNAs a ...

, excising portions of the pre-mRNA called intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e. a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gene. ...

s and splicing the coding portions (exon

An exon is any part of a gene that will form a part of the final mature RNA produced by that gene after introns have been removed by RNA splicing. The term ''exon'' refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene and to the corresponding sequen ...

s) together. After a few more modifications, the spliced pre-mRNA becomes messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

(mRNA) which is then exported from the nucleus and translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

into a protein by ribosomes

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to f ...

.

Discovery of proteins similar to the Sm proteins

The snRNA U6 (unlike U1, U2, U4 and U5) does not associate with the Sm proteins, even though the U6 snRNP is a central component in thespliceosome

A spliceosome is a large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex found primarily within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The spliceosome is assembled from small nuclear RNAs (snRNA) and numerous proteins. Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) molecules bind to specifi ...

. In 1999 a protein heteromer was found that binds specifically to U6, and consisted of seven proteins clearly homologous to the Sm proteins. These proteins were denoted LSm (like Sm) proteins (LSm1, LSm2, LSm3, LSm4, LSm5, LSm6 and LSm7), with the similar LSm8 protein identified later. In the bacterium ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escher ...

'', the Sm-like protein HF-I encoded by the gene ''hfq

The Hfq protein (also known as HF-I protein) encoded by the ''hfq'' gene was discovered in 1968 as an ''Escherichia coli'' host factor that was essential for replication of the bacteriophage Qβ. It is now clear that Hfq is an abundant bacterial RN ...

'' was described in 1968 as an essential host factor for RNA bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

Qβ replication. The genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

of ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae

''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'' () (brewer's yeast or baker's yeast) is a species of yeast (single-celled fungus microorganisms). The species has been instrumental in winemaking, baking, and brewing since ancient times. It is believed to have been o ...

'' (Baker's Yeast) was sequenced in the mid-1990s, providing a rich resource for identifying homologs

A couple of homologous chromosomes, or homologs, are a set of one maternal and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during fertilization. Homologs have the same genes in the same locus (genetics), loci where they pr ...

of these human proteins. Subsequently, as more eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s genomes were sequenced, it became clear that eukaryotes, in general, share homologs to the same set of seven Sm and eight LSm proteins. Soon after, proteins homologous to these eukaryote LSm proteins were found in Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

(Sm1 and Sm2) and Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

(Hfq and YlxS homologs). The archaeal LSm proteins are more similar to the eukaryote LSm proteins than either are to bacterial LSm proteins. The LSm proteins described thus far were rather small proteins, varying from 76 amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s (8.7 kD molecular weight

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

) for human SmG to 231 amino acids (29 kD molecular weight) for human SmB. But recently, larger proteins have been discovered that include a LSm structural domain

In molecular biology, a protein domain is a region of a protein's polypeptide chain that is self-stabilizing and that folds independently from the rest. Each domain forms a compact folded three-dimensional structure. Many proteins consist of s ...

in addition to other protein structural domains (such as LSm10, LSm11, LSm12, LSm13, LSm14, LSm15, LSm16, ataxin-2, as well as archaeal Sm3).

Discovery of the LSm fold

Around 1995, comparisons between the various LSmhomologs

A couple of homologous chromosomes, or homologs, are a set of one maternal and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during fertilization. Homologs have the same genes in the same locus (genetics), loci where they pr ...

identified two sequence motif

In biology, a sequence motif is a nucleotide or amino-acid sequence pattern that is widespread and usually assumed to be related to biological function of the macromolecule. For example, an ''N''-glycosylation site motif can be defined as ''As ...

s, 32 nucleic acids long (14 amino acids), that were very similar in each LSm homolog, and were separated by a non-conserved region of variable length. This indicated the importance of these two sequence motifs (named Sm1 and Sm2), and suggested that all LSm protein genes evolved from a single ancestral gene. In 1999, crystals of recombinant Sm proteins were prepared, allowing X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

and determination of their atomic structure in three dimensions. This demonstrated that the LSm proteins share a similar three-dimensional fold of a short alpha helix

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues e ...

and a five-stranded folded beta sheet

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) (also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a g ...

, subsequently named the LSm fold. Other investigations found that LSm proteins assemble into a torus

In geometry, a torus (plural tori, colloquially donut or doughnut) is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space about an axis that is coplanar with the circle.

If the axis of revolution does not tou ...

(doughnut-shaped ring) of six or seven LSm proteins, and that RNA binds to the inside of the torus, with one nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

bound to each LSm protein.

Structure

uracil

Uracil () (symbol U or Ura) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid RNA. The others are adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). In RNA, uracil binds to adenine via two hydrogen bonds. In DNA, the uracil nucleobase is replaced by ...

is stacked between the histidine

Histidine (symbol His or H) is an essential amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated –NH3+ form under biological conditions), a carboxylic acid group (which is in the de ...

and arginine

Arginine is the amino acid with the formula (H2N)(HN)CN(H)(CH2)3CH(NH2)CO2H. The molecule features a guanidino group appended to a standard amino acid framework. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid is deprotonated (−CO2−) and both the am ...

residues, stabilized by hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a ...

ing to an asparagine

Asparagine (symbol Asn or N) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the depro ...

residue, and hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a ...

ing between the aspartate

Aspartic acid (symbol Asp or D; the ionic form is known as aspartate), is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Like all other amino acids, it contains an amino group and a carboxylic acid. Its α-amino group is in the pro ...

residue and the ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally-occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this compo ...

. LSm proteins are characterized by a beta sheet

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) (also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a g ...

(the secondary structure

Protein secondary structure is the three dimensional conformational isomerism, form of ''local segments'' of proteins. The two most common Protein structure#Secondary structure, secondary structural elements are alpha helix, alpha helices and beta ...

), folded into the LSm fold (the tertiary structure

Protein tertiary structure is the three dimensional shape of a protein. The tertiary structure will have a single polypeptide chain "backbone" with one or more protein secondary structures, the protein domains. Amino acid side chains may int ...

), polymerization into a six or seven member torus

In geometry, a torus (plural tori, colloquially donut or doughnut) is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space about an axis that is coplanar with the circle.

If the axis of revolution does not tou ...

(the quaternary structure

Protein quaternary structure is the fourth (and highest) classification level of protein structure. Protein quaternary structure refers to the structure of proteins which are themselves composed of two or more smaller protein chains (also refe ...

), and binding to RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotides are short DNA or RNA molecules, oligomers, that have a wide range of applications in genetic testing, research, and forensics. Commonly made in the laboratory by solid-phase chemical synthesis, these small bits of nucleic acids c ...

. A modern paradigm classifies proteins on the basis of protein structure

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers specifically polypeptides formed from sequences of amino acids, the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid monomer ma ...

and is a currently active field, with three major approaches, SCOP

A (

or ) was a poet as represented in Old English poetry. The scop is the Old English counterpart of the Old Norse ', with the important difference that "skald" was applied to historical persons, and scop is used, for the most part, to designa ...

(Structural Classification of Proteins), CATH

The CATH Protein Structure Classification database is a free, publicly available online resource that provides information on the evolutionary relationships of protein domains. It was created in the mid-1990s by Professor Christine Orengo and coll ...

(Class, Architecture, Topology, Homologous superfamily), and FSSP/DALI (Families of Structurally Similar Proteins).

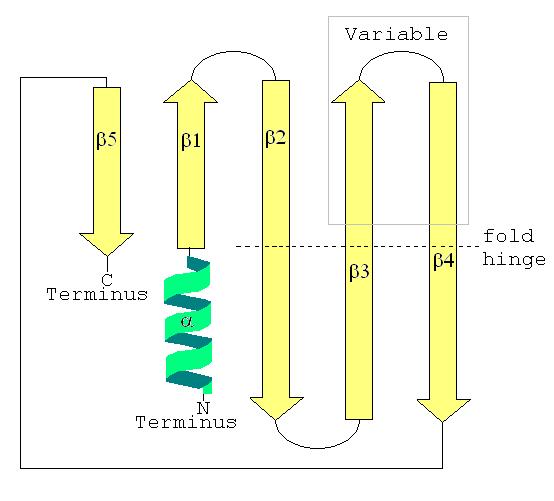

Secondary

Thesecondary structure

Protein secondary structure is the three dimensional conformational isomerism, form of ''local segments'' of proteins. The two most common Protein structure#Secondary structure, secondary structural elements are alpha helix, alpha helices and beta ...

of a LSm protein is a small five-strand anti-parallel beta sheet

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) (also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a g ...

, with the strands identified from the N-terminal end

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the amin ...

to the C-terminal end

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When the protein is ...

as β1, β2, β3, β4, β5. The SCOP class of All beta proteins and the CATH class of Mainly Beta are defined as protein structures that are primarily beta sheets, thus including LSm. The SM1 sequence motif

In biology, a sequence motif is a nucleotide or amino-acid sequence pattern that is widespread and usually assumed to be related to biological function of the macromolecule. For example, an ''N''-glycosylation site motif can be defined as ''As ...

corresponds to the β1, β2, β3 strands, and the SM2 sequence motif corresponds to the β4 and β5 strands. The first four beta strands are adjacent to each other, but β5 is adjacent to β1, turning the overall structure into a short barrel. This structural topology is described as 51234. A short (two to four turns) N-terminal alpha helix

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues e ...

is also present in most LSm proteins. The β3 and β4 strands are short in some LSm proteins, and are separated by an unstructured coil of variable length. The β2, β3 and β4 strands are strongly bent about 120° degrees at their midpoints The bends in these strands are often glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid (carbamic acid is unstable), with the chemical formula NH2‐ CH2‐ COOH. Glycine is one of the proteinogeni ...

, and the side chains internal to the beta barrel are often the hydrophobic residues valine

Valine (symbol Val or V) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH3+ form under biological conditions), an α- carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonat ...

, leucine

Leucine (symbol Leu or L) is an essential amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Leucine is an α-amino acid, meaning it contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH3+ form under biological conditions), an α- ca ...

, isoleucine

Isoleucine (symbol Ile or I) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprot ...

and methionine

Methionine (symbol Met or M) () is an essential amino acid in humans. As the precursor of other amino acids such as cysteine and taurine, versatile compounds such as SAM-e, and the important antioxidant glutathione, methionine plays a critical ro ...

.

Tertiary

SCOP simply classifies the LSm structure as the Sm-like fold, one of 149 different Beta Protein folds, without any intermediate groupings. The LSm beta sheet is sharply bent and described as a Roll architecture in CATH (one of 20 different beta protein architectures in CATH). One of the beta strands (β5 in LSm) crosses the open edge of the roll to form a small SH3 type barrel topology (one of 33 beta roll topologies in CATH). CATH lists 23 homologous superfamilies with an SH3 type barrel topology, one of which is the LSm structure (RNA Binding Protein in the CATH system). SCOP continues its structural classification after Fold to Superfamily, Family and Domain, while CATH continues to Sequence Family, but these divisions are more appropriately described in the "Evolution and phylogeny" section. The SH3-type barreltertiary structure

Protein tertiary structure is the three dimensional shape of a protein. The tertiary structure will have a single polypeptide chain "backbone" with one or more protein secondary structures, the protein domains. Amino acid side chains may int ...

of the LSm fold is formed by the strongly bent (about 120°) β2, β3 and β4 strands, with the barrel structure closed by the β5 strand. Emphasizing the tertiary structure, each bent beta strand can be described as two shorter beta strands. The LSm fold can be viewed as an eight-strand anti-parallel beta sandwich, with five strands in one plane and three strands in a parallel plane with about a 45° pitch angle between the two halves of the beta sandwich. The short (two to four turns) N-terminal alpha helix

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues e ...

occurs at one edge of the beta sandwich. This alpha helix and the beta strands can be labeled (from the N-terminus

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

to the C-terminus

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When the protein is ...

) α, β1, β2a, β2b, β3a, β3b, β4a, β4b, β5 where the a and b refer to either the two halves of a bent strand in the five-strand description, or to the individual strands in the eight-strand description. Each strand (in the eight-strand description) is formed from five amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

residues. Including the bends and loops between the strands, and the alpha helix, about 60 amino acid residues contribute to the LSm fold, but this varies between homologs

A couple of homologous chromosomes, or homologs, are a set of one maternal and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during fertilization. Homologs have the same genes in the same locus (genetics), loci where they pr ...

due to variation in inter-strand loops, the alpha helix, and even the lengths of β3b and β4a strands.

Quaternary

LSm proteins typically assemble into a LSm ring, a six or seven membertorus

In geometry, a torus (plural tori, colloquially donut or doughnut) is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space about an axis that is coplanar with the circle.

If the axis of revolution does not tou ...

, about 7 nanometers

330px, Different lengths as in respect to the molecular scale.

The nanometre (international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: nm) or nanometer (American and British English spelling differences#-re ...

in diameter with a 2 nanometer hole. The ancestral condition is a homohexamer or homoheptamer of identical LSm subunits. LSm proteins in eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s form heteroheptamers of seven different LSm subunits, such as the Sm proteins. Binding between the LSm proteins is best understood with the eight-strand description of the LSm fold. The five-strand half of the beta sandwich of one subunit aligns with the three-strand half of the beta sandwich of the adjacent subunit, forming a twisted 8-strand beta sheet Aβ4a/Aβ3b/Aβ2a/Aβ1/Aβ5/Bβ4b/Bβ3a/Bβ2b, where the A and B refer to the two different subunits. In addition to hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a ...

ing between the Aβ5 and Bβ4b beta strands of the two LSm protein subunits, there are energetically favorable contacts between hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the physical property of a molecule that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water (known as a hydrophobe). In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, th ...

amino acid side chains in the interior of the contact area, and energetically favorable contacts between hydrophilic

A hydrophile is a molecule or other molecular entity that is attracted to water molecules and tends to be dissolved by water.Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon'' Oxford: Clarendon Press.

In contrast, hydrophobes are no ...

amino acid side chains around the periphery of the contact area.

RNA oligonucleotide binding

LSm rings formribonucleoprotein

Nucleoproteins are proteins conjugated with nucleic acids (either DNA or RNA). Typical nucleoproteins include ribosomes, nucleosomes and viral nucleocapsid proteins.

Structures

Nucleoproteins tend to be positively charged, facilitating in ...

complexes with RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

oligonucleotide

Oligonucleotides are short DNA or RNA molecules, oligomers, that have a wide range of applications in genetic testing, research, and forensics. Commonly made in the laboratory by solid-phase chemical synthesis, these small bits of nucleic acids c ...

s that vary in binding strength from very stable complexes (such as the Sm class snRNPs) to transient complexes. RNA oligonucleotides generally bind inside the hole (lumen) of the LSm torus, one nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

per LSm subunit, but additional nucleotide binding sites have been reported at the top (α helix

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues ...

side) of the ring. The exact chemical nature of this binding varies, but common motifs include stacking the heterocyclic base (often uracil

Uracil () (symbol U or Ura) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid RNA. The others are adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). In RNA, uracil binds to adenine via two hydrogen bonds. In DNA, the uracil nucleobase is replaced by ...

) between planar side chains of two amino acids, hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a ...

ing to the heterocyclic base and/or the ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally-occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this compo ...

, and salt bridges to the phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phospho ...

group.

Functions

The various kinds of LSm rings function as scaffolds or chaperones forRNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

oligonucleotide

Oligonucleotides are short DNA or RNA molecules, oligomers, that have a wide range of applications in genetic testing, research, and forensics. Commonly made in the laboratory by solid-phase chemical synthesis, these small bits of nucleic acids c ...

s, assisting the RNA to assume and maintain the proper three-dimensional structure. In some cases, this allows the oligonucleotide RNA to function catalytically as a ribozyme

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are RNA molecules that have the ability to catalyze specific biochemical reactions, including RNA splicing in gene expression, similar to the action of protein enzymes. The 1982 discovery of ribozymes demonst ...

. In other cases, this facilitates modification or degradation of the RNA, or the assembly, storage, and intracellular transport of ribonucleoprotein

Nucleoproteins are proteins conjugated with nucleic acids (either DNA or RNA). Typical nucleoproteins include ribosomes, nucleosomes and viral nucleocapsid proteins.

Structures

Nucleoproteins tend to be positively charged, facilitating in ...

complexes.

Sm ring

The Sm ring is found in thenucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

of all eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s (about 2.5 x 106 copies per proliferating human cell), and has the best understood functions. The Sm ring is a heteroheptamer. The Sm-class snRNA

Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) is a class of small RNA molecules that are found within the splicing speckles and Cajal bodies of the cell nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The length of an average snRNA is approximately 150 nucleotides. They are transcribed ...

molecule (in the 5' to 3' direction) enters the lumen (doughnut hole) at the SmE subunit and proceeds sequentially in a clockwise fashion (looking from the α helix side) inside the lumen (doughnut hole) to the SmG, SmD3, SmB, SmD1, SmD2 subunits, exiting at the SmF subunit. (SmB can be replaced by the splice variant SmB' and by SmN in neural tissues.) The Sm ring permanently binds to the U1, U2, U4 and U5 snRNAs which form four of the five snRNP

snRNPs (pronounced "snurps"), or small nuclear ribonucleoproteins, are RNA-protein complexes that combine with unmodified pre-mRNA and various other proteins to form a spliceosome, a large RNA-protein molecular complex upon which splicing of pre- ...

s that constitute the major spliceosome

A spliceosome is a large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex found primarily within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The spliceosome is assembled from small nuclear RNAs (snRNA) and numerous proteins. Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) molecules bind to specifi ...

. The Sm ring also permanently binds to the U11, U12 and U4atac snRNAs which form four of the five snRNPs (including the U5 snRNP) that constitute the minor spliceosome The minor spliceosome is a ribonucleoprotein complex that catalyses the removal ( splicing) of an atypical class of spliceosomal introns (U12-type) from messenger RNAs in some clades of eukaryotes. This process is called noncanonical splicing, as op ...

. Both of these spliceosomes are central RNA-processing complexes in the maturation of messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

from pre-mRNA

A primary transcript is the single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) product synthesized by transcription of DNA, and processed to yield various mature RNA products such as mRNAs, tRNAs, and rRNAs. The primary transcripts designated to be mRNAs a ...

. Sm proteins have also been reported to be part of ribonucleoprotein

Nucleoproteins are proteins conjugated with nucleic acids (either DNA or RNA). Typical nucleoproteins include ribosomes, nucleosomes and viral nucleocapsid proteins.

Structures

Nucleoproteins tend to be positively charged, facilitating in ...

component of telomerase

Telomerase, also called terminal transferase, is a ribonucleoprotein that adds a species-dependent telomere repeat sequence to the 3' end of telomeres. A telomere is a region of repetitive sequences at each end of the chromosomes of most euka ...

.

Lsm2-8 ring

The two Lsm2-8 snRNPs (U6 and U6atac) have the key catalytic function in the major and minor spliceosomes. These snRNPs do not include the Sm ring, but instead use the heteroheptameric Lsm2-8 ring. The LSm rings are about 20 times less abundant than the Sm rings. The order of these seven LSm proteins in this ring is not known, but based on amino acid sequence homology with the Sm proteins, it is speculated that the snRNA (in the 5' to 3' direction) may bind first to LSm5, and precedes sequentially clockwise to the LSm7, LSm4, LSm8, LSm2, LSm3, and exiting at the LSm6 subunit. Experiments with ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae

''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'' () (brewer's yeast or baker's yeast) is a species of yeast (single-celled fungus microorganisms). The species has been instrumental in winemaking, baking, and brewing since ancient times. It is believed to have been o ...

'' (budding yeast) mutations suggest that the Lsm2-8 ring assists the reassociation of the U4 and U6 snRNPs into the U4/U6 di-snRNP. (After completion of exon deletion and intron splicing, these two snRNPs must reassociate for the spliceosome to initiate another exon/intron splicing cycle. In this role, the Lsm2-8 ring acts as an RNA chaperone instead of an RNA scaffold.) The Lsm2-8 ring also forms an snRNP with the U8 small nucleolar RNA

In molecular biology, Small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) are a class of small RNA molecules that primarily guide chemical modifications of other RNAs, mainly ribosomal RNAs, transfer RNAs and small nuclear RNAs. There are two main classes of snoRNA, t ...

(snoRNA) which localizes in the nucleolus

The nucleolus (, plural: nucleoli ) is the largest structure in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. It is best known as the site of ribosome biogenesis, which is the synthesis of ribosomes. The nucleolus also participates in the formation of sig ...

. This ribonucleoprotein complex is necessary for processing ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

and transfer RNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

to their mature forms. The Lsm2-8 ring is reported to have a role in the processing of pre-P RNA into RNase P RNA. In contrast to the Sm ring, the Lsm2-8 ring does not permanently bind to its snRNA and snoRNA.

Sm10/Sm11 ring

A second type of Sm ring exists whereLSm10

U7 snRNA-associated Sm-like protein LSm10 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''LSM10'' gene.

Interactions

LSM10 has been shown to interact

Advocates for Informed Choice, doing business as, dba interACT or interACT Advocates for ...

replaces SmD1 and LSm11 replaces SmD2. LSm11 is a two domain protein with the C-terminal

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When the protein is ...

domain being a LSm domain. This heteroheptamer ring binds with the U7 snRNA in the U7 snRNP. The U7 snRNP mediates processing of the 3' UTR stem-loop of the histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn are wr ...

mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

in the nucleus. Like the Sm ring, it is assembled in the cytoplasm onto the U7 snRNA by a specialized SMN complex.

Lsm1-7 ring

A second type of Lsm ring is the Lsm1-7 ring, which has the same structure as the Lsm2-8 ring except that LSm1 replaces LSm8. In contrast to the Lsm2-8 ring, the Lsm1-7 ring localizes in thecytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

where it assists in degrading messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

in ribonucleoprotein

Nucleoproteins are proteins conjugated with nucleic acids (either DNA or RNA). Typical nucleoproteins include ribosomes, nucleosomes and viral nucleocapsid proteins.

Structures

Nucleoproteins tend to be positively charged, facilitating in ...

complexes. This process controls the turnover of messenger RNA so that ribosomal translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

of mRNA to protein responds quickly to changes in transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

of DNA to messenger RNA by the cell. LSM1-7, together with Pat1, has been shown to play a role in the formation of P-bodies

P-bodies, or processing bodies are distinct foci formed by phase separation within the cytoplasm of the eukaryotic cell consisting of many enzymes involved in mRNA turnover. P-bodies are highly conserved structures and have been observed in soma ...

after deadenylation.

Gemin6 and Gemin7

The SMN complex (described under "Biogenesis of snRNPs") is composed of the SMN protein and Gemin2-8. Two of these, Gemin 6 and Gemin7 have been discovered to have the LSm structure, and to form a heterodimer. These may have a chaperone function in the SMN complex to assist the formation of the Sm ring on the Sm-class snRNAs. PRMT5 complex is composed of PRMT5, pICln, WD45 (Mep50). pICln helps to form Sm opened ring on SMN complex. SMN complex assists in the assembly ofsnRNP

snRNPs (pronounced "snurps"), or small nuclear ribonucleoproteins, are RNA-protein complexes that combine with unmodified pre-mRNA and various other proteins to form a spliceosome, a large RNA-protein molecular complex upon which splicing of pre- ...

s where the Sm ring is in the open conformation on SMN complex and this Sm ring is loaded onto the snRNA

Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) is a class of small RNA molecules that are found within the splicing speckles and Cajal bodies of the cell nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The length of an average snRNA is approximately 150 nucleotides. They are transcribed ...

by SMN complex.

LSm12-16 and other multi-domain LSm proteins

The LSm12-16 proteins have been described very recently. These are two-domain proteins with aN-terminal

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

LSm domain and a C-terminal

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When the protein is ...

methyl transferase domain. Very little is known about the function of these proteins, but presumably they are member of LSm-domain rings that interact with RNA. There is some evidence that LSm12 is possibly involved in mRNA degradation and LSm13-16 may have roles in regulation of mitosis

In cell biology, mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is mainta ...

. Unexpectedly, LSm12 was recently implicated in Calcium signaling

Calcium signaling is the use of calcium ions (Ca2+) to communicate and drive intracellular processes often as a step in signal transduction. Ca2+ is important for cellular signalling, for once it enters the cytosol of the cytoplasm it exerts all ...

by acting as the intermediate binding-protein for the nucleotide second messenger, NAADP (Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate

Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate, (NAADP), is a Ca2+-mobilizing second messenger synthesised in response to extracellular stimuli. Like its mechanistic cousins, IP3 and cyclic adenosine diphosphoribose (Cyclic ADP-ribose), NAADP bind ...

) that activates endo-lysosomal Ca2+ channels TPCs (Two-pore channel

Two-pore channels (TPCs) are eukaryotic intracellular voltage-gated and ligand gated cation selective ion channels. There are two known paralogs in the human genome, TPC1s and TPC2s. In humans, TPC1s are sodium selective and TPC2s conduct so ...

s). This occurred by NAADP binding to the LSm domain, not the AD domain. A large protein of unknown function, ataxin-2, associated with the neurodegenerative disease spinocerebellar ataxia type 2, also has a N-terminal LSm domain.

Archaeal Sm rings

Two LSm proteins are found in a seconddomain

Domain may refer to:

Mathematics

*Domain of a function, the set of input values for which the (total) function is defined

**Domain of definition of a partial function

**Natural domain of a partial function

**Domain of holomorphy of a function

* Do ...

of life, the Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

. These are the Sm1 and Sm2 proteins (not to be confused with the Sm1 and Sm2 sequence motif

In biology, a sequence motif is a nucleotide or amino-acid sequence pattern that is widespread and usually assumed to be related to biological function of the macromolecule. For example, an ''N''-glycosylation site motif can be defined as ''As ...

s), and are sometimes identified as Sm-like archaeal proteins SmAP1 and SmAP2 for this reason. Sm1 and Sm2 generally form homoheptamer rings, although homohexamer rings have been observed. Sm1 rings are similar to eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

Lsm rings in that they form in the absence of RNA while Sm2 rings are similar to eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

Sm rings in that they require uridine

Uridine (symbol U or Urd) is a glycosylated pyrimidine analog containing uracil attached to a ribose ring (or more specifically, a ribofuranose) via a β-N1-glycosidic bond. The analog is one of the five standard nucleosides which make up nuclei ...

-rich RNA for their formation. They have been reported to associate with RNase P RNA, suggesting a role in transfer RNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

processing, but their function in archaea in this process (and possibly processing other RNA such as ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

) is mostly unknown. One of the two main branches of archaea, the crenarchaeotes have a third known type of archaeal LSm protein, Sm3. This is a two-domain protein with a N-terminal

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

LSm domain that forms a homoheptamer ring. Nothing is known about the function of this LSm protein, but presumably it interacts with, and probably helps process, RNA in these organisms.

Bacterial LSm rings

Several LSm proteins have been reported in the thirddomain

Domain may refer to:

Mathematics

*Domain of a function, the set of input values for which the (total) function is defined

**Domain of definition of a partial function

**Natural domain of a partial function

**Domain of holomorphy of a function

* Do ...

of life, the Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

. Hfq protein forms homohexamer rings, and was originally discovered as necessary for infection by the bacteriophage Qβ

Bacteriophage Qbeta (''Qubevirus durum''), commonly referred to as Qbeta or Qβ, is a positive-strand RNA virus which infects bacteria that have F-pili, most commonly ''Escherichia coli''. Its linear genome is packaged into an icosahedral capsid ...

, although this is clearly not the native function of this protein in bacteria. It is not universally present in all bacteria, but has been found in Pseudomonadota

Pseudomonadota (synonym Proteobacteria) is a major phylum of Gram-negative bacteria. The renaming of phyla in 2021 remains controversial among microbiologists, many of whom continue to use the earlier names of long standing in the literature. The ...

, Bacillota

The Bacillota (synonym Firmicutes) are a phylum of bacteria, most of which have gram-positive cell wall structure. The renaming of phyla such as Firmicutes in 2021 remains controversial among microbiologists, many of whom continue to use the earl ...

, Spirochaetota

A spirochaete () or spirochete is a member of the phylum Spirochaetota (), (synonym Spirochaetes) which contains distinctive diderm (double-membrane) gram-negative bacteria, most of which have long, helically coiled (corkscrew-shaped or ...

, Thermotogota

The Thermotogota are a phylum of the domain Bacteria. The phylum Thermotogota is composed of Gram-negative staining, anaerobic, and mostly thermophilic and hyperthermophilic bacteria.Gupta, RS (2014) The Phylum Thermotogae. The Prokaryotes 989-10 ...

, Aquificota

The ''Aquificota'' phylum is a diverse collection of bacteria that live in harsh environmental settings. The name ''Aquificota'' was given to this phylum based on an early genus identified within this group, ''Aquifex'' (“water maker”), which ...

, and one species of Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

. (This last instance is probably a case of horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

.) Hfq is pleiotropic

Pleiotropy (from Greek , 'more', and , 'way') occurs when one gene influences two or more seemingly unrelated phenotypic traits. Such a gene that exhibits multiple phenotypic expression is called a pleiotropic gene. Mutation in a pleiotropic g ...

with a variety of interactions, generally associated with translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

regulation. These include blocking ribosome binding to mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

, marking mRNA for degradation by binding to their poly-A tails, and association with bacterial small regulatory RNAs (such as DsrA RNA) that control translation by binding to certain mRNAs

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

. A second bacterial LSm protein is YlxS (sometimes also called YhbC), which was first identified in the soil bacterium ''Bacillus subtilis

''Bacillus subtilis'', known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a Gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, humans and marine sponges. As a member of the genus ''Bacillu ...

''. This is a two-domain protein with a N-terminal

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

LSm domain. Its function is unknown, but amino acid sequence homologs are found in virtually every bacterial genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

to date, and it may be an essential protein. The middle domain of the small conductance mechanosensitive channel MscS in ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escher ...

'' forms a homoheptameric ring. This LSm domain has no apparent RNA-binding function, but the homoheptameric torus is part of the central channel of this membrane protein.

Evolution and phylogeny

LSmhomologs

A couple of homologous chromosomes, or homologs, are a set of one maternal and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during fertilization. Homologs have the same genes in the same locus (genetics), loci where they pr ...

are found in all three domains of life, and may even be found in every single organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

. Computational phylogenetic

Computational phylogenetics is the application of computational algorithms, methods, and programs to phylogenetic

methods are used to infer Phylogenetics, phylogenetic relations. Sequence alignment between the various LSm homologs are the appropriate tool for this, such as multiple sequence alignment

Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) may refer to the process or the result of sequence alignment of three or more biological sequences, generally protein, DNA, or RNA. In many cases, the input set of query sequences are assumed to have an evolutio ...

of the primary structure (amino acid sequence), and structural alignment

Structural alignment attempts to establish homology between two or more polymer structures based on their shape and three-dimensional conformation. This process is usually applied to protein tertiary structures but can also be used for large RN ...

of the tertiary structure (three-dimensional structure). It is hypothesized that a gene for a LSm protein was present in the last universal ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descent—the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; th ...

of all life. Based on the functions of known LSm proteins, this original LSm protein may have assisted ribozyme

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are RNA molecules that have the ability to catalyze specific biochemical reactions, including RNA splicing in gene expression, similar to the action of protein enzymes. The 1982 discovery of ribozymes demonst ...

s in the processing of RNA for synthesizing proteins as part of the RNA world hypothesis

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existence ...

of early life. According to this view, this gene was passed from ancestor to descendant, with frequent mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

s, gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene. ...

s and occasional horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

s. In principle, this process can be summarized in a phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

with the root in the last universal ancestor (or earlier), and with the tips representing the universe of LSm genes existing today.

Homomeric LSm rings in bacteria and archaea

Based on structure, the known LSm proteins divide into a group consisting of the bacterial LSm proteins (Hfq, YlxS and MscS) and a second group of all other LSm proteins, in accordance with the most recently publishedphylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

s. The three archaeal LSm proteins (Sm1, Sm2 and Sm3) also cluster as a group, distinct from the eukaryote LSm proteins. Both the bacterial and archaeal LSm proteins polymerize to homomeric rings, which is the ancestral condition.

Heteromeric LSm rings in eukaryotes

A series of gene duplications of a single eukaryote LSm gene resulted in most (if not all) of the known eukaryote LSm genes. Each of the seven Sm proteins has greater amino acid sequence homology to a corresponding Lsm protein than to the other Sm proteins. This suggests that an ancestral LSm gene duplicated several times, resulting in sevenparalogs

Sequence homology is the biological homology between DNA, RNA, or protein sequences, defined in terms of shared ancestry in the evolutionary history of life. Two segments of DNA can have shared ancestry because of three phenomena: either a spec ...

. These subsequently diverged from each other so that the ancestral homoheptamer LSm ring became a heteroheptamer ring. Based on the known functions of LSm proteins in eukaryotes and archaea, the ancestral function may have been processing of pre-ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

, pre-transfer RNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

, and pre-RNase P

Ribonuclease P (, ''RNase P'') is a type of ribonuclease which cleaves RNA. RNase P is unique from other RNases in that it is a ribozyme – a ribonucleic acid that acts as a catalyst in the same way that a protein-based enzyme would. Its fu ...

. Then, according to this hypothesis, the seven ancestral eukaryote LSm genes duplicated again to seven pairs of Sm/LSm paralogs; LSm1/SmB, LSm2/SmD1, LSm3/SmD2, LSm4/SmD3, LSm5/SmE, LSm6/SmF and LSm7/SmG. These two group of seven LSm genes (and the corresponding two kinds of LSm rings) evolved to an Sm ring (requiring RNA) and a Lsm ring (which forms without RNA). The LSm1/LSm8 paralog pair also seems to have originated prior to the last common eukaryote ancestor, for a total of at least 15 LSm protein genes. The SmD1/LSm10 paralog pair and the SmD2/LSm11 paralog pair exist only in animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

s, fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

, and the amoebozoa

Amoebozoa is a major taxonomic group containing about 2,400 described species of amoeboid protists, often possessing blunt, fingerlike, lobose pseudopods and tubular mitochondrial cristae. In traditional and currently no longer supported classi ...

(sometimes identified as the unikont

Amorphea are members of a taxonomic supergroup that includes the basal Amoebozoa and Obazoa. That latter contains the Opisthokonta, which includes the Fungi, Animals and the Choanomonada, or Choanoflagellates. The taxonomic affinities of the ...

clade) and appears to be absent in the bikont

A bikont ("two flagella") is any of the eukaryotic organisms classified in the group Bikonta. Many single-celled members of the group, and the presumed ancestor, have two flagella.

Enzymes

Another shared trait of bikonts is the fusion of two ge ...

clade (chromalveolate

Chromalveolata was a eukaryote supergroup present in a major classification of 2005, then regarded as one of the six major groups within the eukaryotes.

It was a refinement of the kingdom Chromista, first proposed by Thomas Cavalier-Smith in 1 ...

s, excavates, plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s and rhizaria

The Rhizaria are an ill-defined but species-rich supergroup of mostly unicellular eukaryotes. Except for the Chlorarachniophytes and three species in the genus Paulinella in the phylum Cercozoa, they are all non-photosynthethic, but many foramini ...

). Therefore, these two gene duplications predated this fundamental split in the eukaryote lineage. The SmB/SmN paralog pair is seen only in the placental mammals

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

, which dates this LSm gene duplication.

Biogenesis of snRNPs

Small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) assemble in a tightly orchestrated and regulated process that involves both thecell nucleus

The cell nucleus (pl. nuclei; from Latin or , meaning ''kernel'' or ''seed'') is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, h ...

and cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

.

References

External links

Pfam entry LSM. Pfam is the Sanger Institute database, which is a collection of protein families and domains.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lsm Protein families Spliceosome