The Kingdom of Greece (,

romanized

In linguistics, romanization is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and transcription, ...

: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'',

pronounced ) was the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

nation-state

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly or ideally) con ...

established in 1832 and was the

successor state

Succession of states is a concept in international relations regarding a successor state that has become a sovereign state over a territory (and populace) that was previously under the sovereignty of another state. The theory has its roots in 19th ...

to the

First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally recognised by the

Treaty of Constantinople, where Greece also secured its full

independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of ...

from the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

after nearly four centuries. It remained a Kingdom until 1924, when the

Second Hellenic Republic

The Second Hellenic Republic is a modern Historiography, historiographical term used to refer to the Greece, Greek state during a period of republican governance between 1924 and 1935. To its contemporaries it was known officially as the Hellenic ...

was proclaimed, and from the Republic's collapse in 1935 to its

dissolution by the

Regime of the Colonels in 1973. A

referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

following the

regime's collapse in 1974 confirmed the effective dissolution of the monarchy and the creation of the

Third Hellenic Republic

The Third Hellenic Republic () is the period in modern Greek history that stretches from 1974, with the fall of the Greek military junta and the final confirmation of the abolition of the Greek monarchy, to the present day.

It is considered ...

. For much of its existence, the Kingdom's main ideological goal was the

Megali Idea (Greek: Μεγάλη Ιδέα, romanized: Megáli Idéa, lit. 'Great Idea'), which sought to annex lands with predominately Greek populations.

King Otto of the

House of Wittelsbach

The House of Wittelsbach () is a former Bavarian dynasty, with branches that have ruled over territories including the Electorate of Bavaria, the Electoral Palatinate, the Electorate of Cologne, County of Holland, Holland, County of Zeeland, ...

ruled as an absolute monarch from 1835 until the

3 September 1843 Revolution, which transformed Greece into a constitutional monarchy, with the creation of the

Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

as head of government, universal male suffrage and a

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

. A

popular insurrection deposed Otto in 1862, precipitating the gradual collapse of the

early Greek parties (

English,

French,

Russian), which had dominated Greek politics.

The

Greek National Assembly's election of

George I of the

House of Glücksburg

The House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, also known by its short name as the House of Glücksburg, is the senior surviving branch of the German House of Oldenburg, one of Europe's oldest royal houses. Oldenburg house members hav ...

in 1863 brought the transfer of the

Ionian Islands

The Ionian Islands (Modern Greek: , ; Ancient Greek, Katharevousa: , ) are a archipelago, group of islands in the Ionian Sea, west of mainland Greece. They are traditionally called the Heptanese ("Seven Islands"; , ''Heptanēsa'' or , ''Heptanē ...

from

British rule

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

* or dire ...

in 1864. In his fifty–year reign, George presided over long periods of political instability, and wielded considerable power despite his role as a constitutional monarch. Prime Ministers, such as

Alexandros Koumoundouros and

Charilaos Trikoupis, shaped the politics and identity of the kingdom (including the annexation of

Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

in 1881) before an

economic depression

An economic depression is a period of carried long-term economic downturn that is the result of lowered economic activity in one or more major national economies. It is often understood in economics that economic crisis and the following recession ...

and a catastrophic defeat in the

Thirty Days' War weakened the Greek state. The

Goudi coup in 1909 brought

Eleftherios Venizelos to power and brought sweeping reforms, culminating in the

Hellenic Army

The Hellenic Army (, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the army, land force of Greece. The term Names of the Greeks, '' Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the largest of the three branches ...

's victory in the

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

, led militarily by

Crown Prince Constantine, who became King following

George I's assassination during the

First Balkan War

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Greece, Greece and Kingdom of Montenegro, Montenegro) agai ...

.

The dispute and deep political rift of Monarchist and Venizelist forces regarding Greece's initial neutrality in

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

led to the

National Schism, which, with

Allied intervention, culminated in Constantine's exile, Venizelos' reinstatement as Prime Minister and Greece's entry into World War I. After victory in the

Macedonian Front and success in the

Asia Minor Campaign against the Ottomans,

King Alexander, Constantine's second son, died in 1920, which triggered a constitutional crisis, culminating in anti-Venizelist candidate

Dimitrios Gounaris' victory in the

1920 elections and a

plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

confirming Constantine's return to the throne. Greece's

disastrous defeat in Asia Minor two years later triggered the

11 September 1922 Revolution, which brought the abdication of Constantine in favour of his first son

George II and the execution of Monarchist leaders in the

Trial of the Six. The

Treaty of Lausanne and the

population exchange, along with a failed Monarchist coup in 1923, brought the proclamation of the Second Hellenic Republic in 1924.

A failed Venizelist coup in 1935 rapidly accelerated the Second Republic's collapse, with the Monarchy restored following a

sham referendum in November 1935. Prime Minister

Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; 12 April 187129 January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who was dictator of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for the first four months of his tenure, and thereafter as th ...

initiated a self-coup with the support of King George on 4 August 1936 and established the

4th of August Regime, a

Metaxist and

ultranationalist dictatorship with Metaxas wielding absolute power. Following Greece's entry into

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and the

Greco-Italian War, the

German invasion of Greece

The German invasion of Greece or Operation Marita (), were the attacks on Kingdom of Greece, Greece by Kingdom of Italy, Italy and Nazi Germany, Germany during World War II. The Italian invasion in October 1940, which is usually known as the Gr ...

toppled the Monarchy and conquered Greece, resulting in a

triple occupation by the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

.

After the withdrawal of

German forces in late 1944, the Monarchy was reaffirmed by victory in the three-year

Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War () took place from 1946 to 1949. The conflict, which erupted shortly after the end of World War II, consisted of a Communism, Communist-led uprising against the established government of the Kingdom of Greece. The rebels decl ...

. Spearheaded by Prime Ministers

Alexandros Papagos and

Konstantinos Karamanlis, Greece entered an

economic miracle, but a successful coup on 21 April 1967 established the Regime of the Colonels, a

military dictatorship

A military dictatorship, or a military regime, is a type of dictatorship in which Power (social and political), power is held by one or more military officers. Military dictatorships are led by either a single military dictator, known as a Polit ...

. A failed counter-coup by King

Constantine II on 13 December 1967 forced him into exile, and the Monarchy was dissolved in 1973, a decision that was reaffirmed by a democratic referendum in 1974.

In total, the Kingdom of Greece had seven Kings, the last of which, Constantine II, died in 2023.

Background

The Greek-speaking

Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

, also known as the Byzantine Empire, which ruled most of the Eastern Mediterranean region for over 1100 years, had been fatally weakened since the

sacking of Constantinople by the

Latin Crusaders in 1204.

The Ottomans

captured Constantinople in 1453 and advanced southwards into the Balkan peninsula capturing

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

in 1458. The Greeks held out in the

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

until 1460, and the

Venetians and

Genoese clung to some of the islands, but by 1500 most of the plains and islands of Greece were in Ottoman hands; while in contrast, the mountains and highlands of Greece were largely untouched, and were a refuge for Greeks to flee foreign rule and engage in guerrilla warfare.

Preparation of the Greek War of Independence

In the context of an ardent desire for independence from Turkish rule, and with the explicit influence of similar secret societies elsewhere in Europe, three Greeks came together in 1814 in

Odesa

Odesa, also spelled Odessa, is the third most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern ...

to decide the constitution for a secret organization in

Freemasonic fashion. Its purpose was to unite all Greeks in an armed organization to overthrow Turkish rule. The three founders were

Nikolaos Skoufas from the

Arta province,

Emmanuil Xanthos from

Patmos

Patmos (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Aegean Sea. It is famous as the location where, according to Christian belief, John of Patmos received the vision found in the Book of Revelation of the New Testament, and where the book was written.

...

, and

Athanasios Tsakalov from

Ioannina

Ioannina ( ' ), often called Yannena ( ' ) within Greece, is the capital and largest city of the Ioannina (regional unit), Ioannina regional unit and of Epirus (region), Epirus, an Modern regions of Greece, administrative region in northwester ...

. Soon after they initiated a fourth member,

Panagiotis Anagnostopoulos from

Andritsaina.

Many revolts were planned across the Greek region and the first of them was launched on 6 March 1821, in the

Danubian principalities. It was put down by the Ottomans, but the torch had been lit and by the end of the same month, the Peloponnese was in open revolt.

Greek War of Independence

In 1821, the Greek-speaking populations of

Peloponnesus

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the ...

revolted against the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. Following a region-wide struggle that lasted several months, the

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

led to the establishment of the first autonomous Greek state since the mid-15th century.

In January 1822, the

First National Assembly of Epidaurus passed the

Greek Declaration of Independence (part of the country's

First Constitution), which affirmed the sovereignty of Greece. However, the new Greek state was politically unstable and lacked the resources to preserve its territoriality in the long term. Most importantly, the country lacked international recognition and had no robust alliances in the Western world.

Following the recapture of the Greek territories by the Ottoman Empire, the

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

s of that time (the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, and the

Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the Middle Ages, medieval and Early modern France, early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from th ...

) saw the Greek counter-offensive as an opportunity to weaken the Ottoman Empire further and in essence increase their influence in the

Eastern Mediterranean

The Eastern Mediterranean is a loosely delimited region comprising the easternmost portion of the Mediterranean Sea, and well as the adjoining land—often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea. It includes the southern half of Turkey ...

. The Great Powers supported Greece to regain its independence and following a decisive

battle in the Navarino Bay, a ceasefire was agreed in London (see

Treaty of London (1827)). The autonomy of Greece was ultimately recognised by the

London Protocol of 1828 and its full independence from the Ottoman Empire by the

Protocol of London of 1830.

In 1831, the assassination of the first governor of Greece,

Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

Ioannis Kapodistrias

Count Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias (; February 1776 –27 September 1831), sometimes anglicized as John Capodistrias, was a Greek statesman who was one of the most distinguished politicians and diplomats of 19th-century Europe.

Kapodistrias's ...

, created political and social instability that endangered the country's relationship with its allies. To avoid escalation and in order to strengthen Greece's ties with the great powers, Greece agreed to become a kingdom in 1832 (see

London Conference of 1832). Prince

Leopold of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was initially the first candidate for the Greek throne; however, he turned down the offer.

Otto von Wittelsbach, Prince of Bavaria was chosen as its first

king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

. Otto arrived at the provisional capital,

Nafplion

Nafplio or Nauplio () is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece. It is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important tourist destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in the Middle Ages du ...

, in 1833 aboard

a British warship.

History

Reign of King Otto (1832–1862)

Otto's reign would prove troubled, but managed to last for 30 years before he and his wife,

Queen Amalia, left the way they came, aboard a British warship. During the early years of his reign, a group of Bavarian Regents ruled in his name and made themselves very unpopular by trying to impose German ideas of rigid hierarchical government on the Greeks, while keeping most significant state offices away from them. Nevertheless, they laid the foundations of a Greek administration, army, justice system and education system. Otto was sincere in his desire to give Greece good government, but he suffered from two great handicaps, him being a

Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

while most Greek people were

Orthodox Christian, and the fact that his marriage to Queen

Amalia remained childless. Furthermore, the new kingdom tried to eliminate the traditional

banditry, something that in many cases meant conflict with some old revolutionary fighters (

klepht

Klephts (; Greek κλέφτης, ''kléftis'', pl. κλέφτες, ''kléftes'', which means "thieves" and perhaps originally meant just "brigand": "Other Greeks, taking to the mountains, became unofficial, self-appointed armatoles and were know ...

es) who continued to exercise this practice.

The Bavarian Regents ruled until 1837, when at the insistence of Britain and France, they were recalled, and Otto after that appointed Greek ministers, although Bavarian officials still ran most of the administration and the army. But Greece still had no legislature and no constitution. Greek discontent grew until a

revolt broke out in

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

in September 1843. Otto agreed to grant a constitution, and convened a National Assembly which met in November. The

new constitution created a

bicameral parliament, consisting of an Assembly (''Vouli'') and a Senate (''Gerousia''). Power then passed into the hands of a group of politicians, most of whom had been commanders in the War of Independence against the Ottomans.

Greek politics in the 19th century was dominated by the national question. Greeks dreamed of liberating all the Greek lands and reconstituting a state embracing them all, with

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

as its capital. This was called the Great Idea (''

Megali Idea''), and it was sustained by almost continuous rebellions against Ottoman rule in Greek-speaking territories, notably

Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

,

Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

and

Macedonia. During the

Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

the British occupied

Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

to prevent Greece declaring war on the Ottomans as a Russian ally.

A new generation of Greek politicians was growing increasingly intolerant of King Otto's continuing interference in government. In 1862, the King dismissed his prime minister, the former admiral

Konstantinos Kanaris, the most prominent politician of the period. This dismissal provoked a military rebellion, forcing Otto to accept the inevitable and leave the country. The Greeks then asked Britain to send

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

's son Prince

Alfred as their new king, but this was vetoed by the other Powers. Instead, a young Danish prince became King

George I. George was a very popular choice as a constitutional monarch, and he agreed that his sons would be raised in the Greek Orthodox faith. As a reward to the Greeks for adopting a pro-British king, Britain ceded the

United States of the Ionian Islands to Greece.

Religious life

Under Ottoman rule, the Greek Church was a part of the

Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (, ; ; , "Roman Orthodox Patriarchate, Ecumenical Patriarchate of Istanbul") is one of the fifteen to seventeen autocephalous churches that together compose the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is heade ...

. The Ottoman authorities, who were Muslim, did not interfere with the church. With the establishment of the Greek Kingdom, however, the government decided to take control of the church, breaking away from the patriarch in Constantinople. The government declared the church to be

autocephalous

Autocephaly (; ) is the status of a hierarchical Christian church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches. The status has been compared with t ...

(independent) in 1833 in a political decision of the Bavarian regents acting for King

Otto, who was a minor. The decision roiled Greek politics for decades as royal authorities took increasing control. The new status was finally recognised as such by the Patriarchate in 1850, under compromise conditions with the issue of a special "

Tomos" decree which brought it back to a normal status. As a result, it retains certain special links with the "

Mother Church

Mother church or matrice is a term depicting the Christian Church as a mother in her functions of nourishing and protecting the believer. It may also refer to the primary church of a Christian denomination or diocese, i.e. a cathedral church, or ...

". There were only four bishops, and they had political roles.

In 1833 Parliament dissolved 400 small monasteries having fewer than five monks or nuns. Priests were not salaried; in rural areas he was a peasant farmer himself dependent for his livelihood on his farm work and from fees and offerings by his parishioners. His ecclesiastical duties were limited to administering the sacraments, supervising funerals, the blessings of crops, and exorcism. Few attended seminaries. By the 1840s, there was a nationwide revival, run by travelling preachers. The government arrested several and tried to shut down the revival, but it proved too powerful when the revivalists denounced three bishops for purchasing their office. By the 1880s the "Anaplasis" ("Regeneration") Movement led to renewed spiritual energy and enlightenment. It fought against the rationalistic and materialistic ideas that had seeped in from secular Western Europe. It promoted catechism schools, and circles for the study of the Bible.

Reign of King George I (1863–1913)

At the urging of Britain and King George, Greece adopted a much more democratic

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

in 1864. The powers of the king were reduced and the Senate was abolished, and the franchise was extended to all adult males. Nevertheless, Greek politics remained heavily dynastic, as it had always been. Family names such as Zaimis, Rallis and Trikoupis repeatedly occurred as prime ministers. Although parties were centered around the individual leaders, often bearing their names, two broad political tendencies existed: the liberals, led first by

Charilaos Trikoupis and later by

Eleftherios Venizelos, and the conservatives, led initially by

Theodoros Deligiannis and later by

Thrasivoulos Zaimis.

Trikoupis and Deligiannis dominated Greek politics in the later 19th century, alternating in office. Trikoupis favoured cooperation with Great Britain in foreign affairs, the creation of infrastructure and an indigenous industry, raising protective tariffs and progressive social legislation, while the more populist Deligiannis depended on the promotion of Greek nationalism and the

Megali idea.

Greece remained a quite impoverished country throughout the 19th century. The country lacked raw materials, infrastructure and capital. Agriculture was mostly at the subsistence level, and the only important export commodities were

currants, raisins and tobacco. Some Greeks grew rich as merchants and shipowners, and Piraeus became a major port, but little of this wealth found its way to the Greek peasantry. Greece remained hopelessly in debt to London finance houses.

By the 1890s Greece was virtually bankrupt, and public insolvency was declared in 1893. Poverty was rife in the rural areas and the islands and was eased only by large-scale emigration to the United States. There was little education in the countryside. Nevertheless, there was progress in building communications and infrastructure, and elegant public buildings were erected in Athens. Despite the bad financial situation, Athens staged the

revival of the Olympic Games in 1896, which proved a great success.

The parliamentary process developed greatly in Greece during the reign of George I. Initially, the royal prerogative in choosing his prime minister remained and contributed to governmental instability, until the introduction of the principle of

parliamentary confidence in 1875 by the reformist

Charilaos Trikoupis. Clientelism and frequent electoral upheavals, however, remained the norm in Greek politics and frustrated the country's development. Corruption and Trikoupis' increased spending to create necessary infrastructure like the

Corinth Canal

The Corinth Canal () is a canal in Greece that connects the Gulf of Corinth in the Ionian Sea with the Saronic Gulf in the Aegean Sea. Completed in 1893, it cuts through the narrow Isthmus of Corinth and "separates" the Peloponnese peninsula fro ...

overtaxed the weak Greek economy, forcing the declaration of

public insolvency in 1893 and to accept the imposition of an

International Financial Commission to pay off the country's debtors.

Another political issue in 19th-century Greece was uniquely Greek: the language question. The Greek people spoke a form of Greek called

Demotic

Demotic may refer to:

* Demotic Greek, the modern vernacular form of the Greek language

* Demotic (Egyptian), an ancient Egyptian script and version of the language

* Chữ Nôm

Chữ Nôm (, ) is a logographic writing system formerly used t ...

. Many of the educated elite saw this as a peasant dialect and were determined to restore the glories of

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

. Government documents and newspapers were consequently published in (purified) Greek, a form which few ordinary Greeks could read. Liberals favoured recognising Demotic as the national language, but conservatives and the Orthodox Church resisted all such efforts, to the extent that, when the

New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

was translated into Demotic in 1901, riots erupted in Athens and the government fell (the ). This issue would continue to plague Greek politics until the 1970s.

All Greeks were united, however, in their determination to liberate the Greek-speaking provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Especially in

Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, a

prolonged revolt in 1866–1869 had raised nationalist fervour. When war broke out between

Russia and the Ottomans in 1877, popular Greek sentiment rallied to Russia's side, but Greece was too poor and too concerned about British intervention to officially enter the war. Nevertheless, in 1881,

Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

and small parts of

Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

were ceded to Greece in the context of the

Treaty of Berlin, while frustrating Greek hopes of receiving

Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

.

Greeks in Crete continued to stage regular revolts, and in 1897, the Greek government under

Theodoros Diligiannis, bowing to popular pressure, declared war on the Ottomans. In the ensuing

Greco-Turkish War of 1897

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War (), was a war fought between the Kingdom of Greece and the O ...

the badly trained and equipped

Greek army was defeated by the Ottomans. Through the intervention of the Great Powers, however, Greece lost only a little territory along the border to Turkey, while Crete was established as an

autonomous state with the

High Commissioner being

Prince George of Greece. Nationalist sentiment among Greeks in the Ottoman Empire continued to grow, and by the 1890s there were constant disturbances in

Macedonia. Here the Greeks were in competition not only with the Ottomans but also with the Bulgarians, engaged in an armed propaganda struggle for the hearts and minds of the ethnically mixed local population, the so-called "

Macedonian Struggle". In July 1908, the

Young Turk Revolution broke out in the Ottoman Empire.

Taking advantage of the Ottoman internal turmoil,

Austria–Hungary annexed

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina, sometimes known as Bosnia-Herzegovina and informally as Bosnia, is a country in Southeast Europe. Situated on the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula, it borders Serbia to the east, Montenegro to the southeast, and Croatia to th ...

, and

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire. On Crete, the local population, led by a young politician named

Eleftherios Venizelos, declared , union with Greece, provoking another crisis. The fact that the Greek government, led by

Dimitrios Rallis, proved unable likewise to take advantage of the situation and bring Crete into the fold, rankled with many Greeks, especially with young officers. These formed a secret society, the "

Military League", with the purpose of emulating their Ottoman colleagues and seeking reforms. The resulting

Goudi coup on 15 August 1909 marked a watershed in modern Greek history: as the military conspirators were inexperienced in politics, they asked Venizelos, who had impeccable liberal credentials, to come to Greece as their political adviser. Venizelos quickly established himself as an influential political figure, and his allies won the

August 1910 elections. Venizelos became Prime Minister in October 1910, ushering a period of 25 years where his personality would dominate Greek politics.

Venizelos initiated a major reform program, including a

new and more liberal constitution and reforms in the spheres of public administration, education and economy. French and British military missions were invited for the army and navy respectively, and arms purchases were made. In the meantime, the Ottoman Empire's weaknesses were revealed by the ongoing

Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish (, "Tripolitanian War", , "War of Libya"), also known as the Turco-Italian War, was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911 to 18 October 1912. As a result of this conflict, Italy captur ...

in Libya.

Through spring 1912, a series of bilateral agreements among the Balkan states (Greece,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

,

Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

and

Serbia

, image_flag = Flag of Serbia.svg

, national_motto =

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Serbia.svg

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map =

, map_caption = Location of Serbia (gree ...

) formed the

Balkan League, which in October 1912 declared war on the Ottoman Empire.

Balkan Wars

Macedonian front

Ottoman intelligence had disastrously misread Greek military intentions. In retrospect, it would appear that the Ottoman staff believed that the Greek attack would be shared equally between the two primary avenues of approach, Macedonia and Epirus. The 2nd Army staff had therefore evenly balanced the combat strength of the seven Ottoman divisions between the

Yanya Corps and

VIII Corps, in Epirus and Macedonia respectively. The Greek Army also fielded seven divisions, but, having the initiative, concentrated all seven against VIII Corps, leaving only a number of independent battalions of scarcely divisional strength in the Epirus front. This had fatal consequences for the Western Group of Armies, since it led to the early loss of the strategic centre of all three Macedonian fronts, the city of

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

, a fact that sealed their fate. In an unexpectedly brilliant and rapid campaign, the

Army of Thessaly seized the city. In the absence of secure sea lines of communications, the retention of the Thessaloniki-Constantinople corridor was essential to the overall strategic posture of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans. Once this was gone, the defeat of the Ottoman Army became inevitable. To be sure, the Bulgarians and the Serbs played a significant role in the defeat of the main Ottoman armies. Their great victories at

Kirk Kilise,

Lule Burgas,

Kumanovo

Kumanovo ( ; , sq-definite, Kumanova; also known by other #Etymology, alternative names) is the second-largest city in North Macedonia after the capital Skopje and the seat of Kumanovo Municipality, the List of municipalities in the Republic ...

, and

Monastir shattered the

Eastern and

Vardar

The Vardar (; , , ) or Axios (, ) is the longest river in North Macedonia and a major river in Greece, where it reaches the Aegean Sea at Thessaloniki. It is long, out of which are in Greece, and drains an area of around . The maximum depth of ...

armies. However, these victories were not decisive in the sense that they ended the war. The Ottoman field armies survived, and in Thrace, they actually grew stronger day by day. In the strategic point of view these victories were enabled partially by the weakened condition of the Ottoman armies brought about by the active presence of the Greek army and fleet.

With the declaration of war, the Greek Army of Thessaly under Crown Prince

Constantine advanced to the north, successfully

overcoming Ottoman opposition in the fortified Straits of Sarantaporo. After another victory at

Giannitsa on , the Ottoman commander

Hasan Tahsin Pasha surrendered Thessaloniki and its garrison of 26,000 men to the Greeks on . Two Corps HQs (

Ustruma and VIII), two Nizamiye divisions (14th and 22nd) and four Redif divisions (Salonika, Drama, Naslic and Serez) were thus lost to the Ottoman order of battle. Additionally, the Ottoman forces lost 70 artillery pieces, 30 machine guns and 70,000 rifles (Thessaloniki was the central arms depot for the Western Armies). The Ottoman forces estimated that 15,000 officers and men had been killed during the campaign in Macedonia, bringing total losses up to 41,000 soldiers. Another direct consequence was that the destruction of the Macedonian Army sealed the fate of the Ottoman Vardar Army, which was fighting the Serbs to the north. The fall of Thessaloniki left it strategically isolated, without logistical supply and depth to manoeuvre, ensuring its destruction.

Upon learning of the outcome of the battle of Yenidje, the Bulgarian high command urgently dispatched their 7th ''Rila'' Division from the north in the direction of the city. The division arrived there a week later, the day after its surrender to the Greeks. Until 10 November, the Greek-occupied zone had been expanded to the line from

Lake Dojran to the

Pangaion hills west to

Kavalla. In southern Yugoslavia however, the lack of coordination between the Greek and Serbian HQs cost the Greeks a setback in the

Battle of Vevi on , when the Greek

5th Infantry Division crossed its way with the

VI Ottoman Corps (a part of the Vardar Army consisting of the 16th, 17th and 18th Nizamiye divisions), retreating to Albania following the

Battle of Prilep against the Serbs. The Greek division, surprised by the presence of the Ottoman Corps, isolated from the rest of Greek army and outnumbered by the now counterattacking Ottomans centred on

Bitola, was forced to retreat. As a result, the Serbs beat the Greeks to Bitola.

Epirus front

In the

Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

front the Greek army was initially heavily outnumbered, but due to the passive attitude of the Ottomans succeeded in conquering

Preveza

Preveza (, ) is a city in the region of Epirus (region), Epirus, northwestern Greece, located on the northern peninsula of the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf. It is the capital of the Preveza (regional unit), regional unit of Preveza, which is the s ...

(21 October 1912) and pushing north to the direction of

Ioannina

Ioannina ( ' ), often called Yannena ( ' ) within Greece, is the capital and largest city of the Ioannina (regional unit), Ioannina regional unit and of Epirus (region), Epirus, an Modern regions of Greece, administrative region in northwester ...

. On 5 November, Major

Spyros Spyromilios led a

revolt in the coastal area of

Himarë

Himarë ( sq-definite, Himara; , ''Chimara'' or Χειμάρρα, ''Cheimarra'') is a Municipalities of Albania, municipality and region in Vlorë County, southern Albania. The municipality has a total area of and consists of the administrative ...

and expelled the Ottoman garrison without facing significant resistance,

while on 20 November Greek troops from western Macedonia entered

Korçë

Korçë (; sq-definite, Korça) is the List of cities and towns in Albania, eighth most populous city of Albania and the seat of Korçë County and Korçë Municipality. The total population of the city is 51,152 and 75,994 of Korçë municipal ...

. However, Greek forces in the Epirote front had not the numbers to initiate an offensive against the German-designed defensive positions of

Bizani that protected the city of Ioannina, and therefore had to wait for reinforcements from the Macedonian front.

After the campaign in Macedonia was over, a large part of the Army was redeployed to Epirus, where Crown Prince Constantine himself assumed command. In the

Battle of Bizani the Ottoman positions were breached and Ioannina taken on . During the siege, on 8 February 1913, the Russian pilot N. de Sackoff, flying for the Greeks, became the first pilot ever shot down in combat, when his biplane was hit by ground fire following a bomb run on the walls of Fort

Bizani. He came down near the small town of

Preveza

Preveza (, ) is a city in the region of Epirus (region), Epirus, northwestern Greece, located on the northern peninsula of the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf. It is the capital of the Preveza (regional unit), regional unit of Preveza, which is the s ...

, on the coast north of the Ionian island of

Lefkas, secured local Greek assistance, repaired his plane and resumed his flight back to base.

[Baker, David, "Flight and Flying: A Chronology", Facts On File, Inc., New York, New York, 1994, Library of Congress card number 92-31491, , page 61.] The fall of Ioannina allowed the Greek army to continue its advance into

northern Epirus, the southern part of modern Albania, which it occupied. There its advance stopped, although the Serbian line of control was very close to the north.

Naval operations in the Aegean and Ionian seas

On the outbreak of hostilities on 18 October, the

Greek fleet, placed under the newly promoted Rear Admiral

Pavlos Kountouriotis, sailed for the island of

Lemnos

Lemnos ( ) or Limnos ( ) is a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos (regional unit), Lemnos regional unit, which is part of the North Aegean modern regions of Greece ...

, occupying it three days later (although fighting continued on the island until 27 October) and establishing an anchorage at

Moudros Bay. This move was of major strategic importance, as it provided the Greeks with a forward base in close distance to the Dardanelles, the Ottoman fleet's main anchorage and refuge.

[Hall (2000), p. 64] In view of the Ottoman fleet's superiority in speed and

broadside weight, the Greek planners expected it to sortie from the straits early in the war. Given the Greek fleet's unpreparedness resulting from the premature outbreak of the war, such an early Ottoman attack might well have been able to achieve a crucial victory. Instead, the

Ottoman Navy

The Ottoman Navy () or the Imperial Navy (), also known as the Ottoman Fleet, was the naval warfare arm of the Ottoman Empire. It was established after the Ottomans first reached the sea in 1323 by capturing Praenetos (later called Karamürsel ...

spent the first two months of the war in operations against the Bulgarians in the Black Sea, giving the Greeks valuable time to complete their preparations and allowing them to consolidate their control of the Aegean.

By mid-November Greek naval detachments had seized the islands of

Imbros,

Thasos

Thasos or Thassos (, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of 380 km2 and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate regiona ...

,

Agios Efstratios,

Samothrace,

Psara and

Ikaria, while landings were undertaken on the larger islands of

Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

and

Chios

Chios (; , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, tenth largest island in the Medi ...

only on 21 and 27 November respectively. Substantial Ottoman garrisons were present on the latter, and their resistance was fierce. They withdrew into the mountainous interior and were not subdued until 22 December and 3 January respectively.

Samos

Samos (, also ; , ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese archipelago, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the Mycale Strait. It is also a separate reg ...

, officially an

autonomous principality, was not attacked until 13 March 1913, out of a desire not to upset the Italians in the nearby

Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; , ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger and 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. This island group generally define ...

. The clashes there were short-lived as the Ottoman forces withdrew to the Anatolian mainland so that the island was securely in Greek hands by 16 March.

At the same time, with the aid of numerous merchant ships converted to

auxiliary cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

s, a loose naval blockade on the Ottoman coasts from the Dardanelles to

Suez

Suez (, , , ) is a Port#Seaport, seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest c ...

was instituted, which disrupted the Ottomans' flow of supplies (only the Black Sea routes to Romania remained open) and left some 250,000 Ottoman troops immobilized in Asia. In the

Ionian Sea

The Ionian Sea (, ; or , ; , ) is an elongated bay of the Mediterranean Sea. It is connected to the Adriatic Sea to the north, and is bounded by Southern Italy, including Basilicata, Calabria, Sicily, and the Salento peninsula to the west, ...

, the Greek fleet operated without opposition, ferrying supplies for the army units in the Epirus front. Furthermore, the Greeks bombarded and then blockaded the port of

Vlorë

Vlorë ( ; ; sq-definite, Vlora) is the List of cities and towns in Albania, third most populous city of Albania and seat of Vlorë County and Vlorë Municipality. Located in southwestern Albania, Vlorë sprawls on the Bay of Vlorë and is surr ...

in Albania on 3 December, and

Durrës

Durrës ( , ; sq-definite, Durrësi) is the List of cities and towns in Albania#List, second most populous city of the Albania, Republic of Albania and county seat, seat of Durrës County and Durrës Municipality. It is one of Albania's oldest ...

on 27 February. A naval blockade extending from the pre-war Greek border to Vlorë was also instituted on 3 December, isolating the newly established

Provisional Government of Albania based there from any outside support.

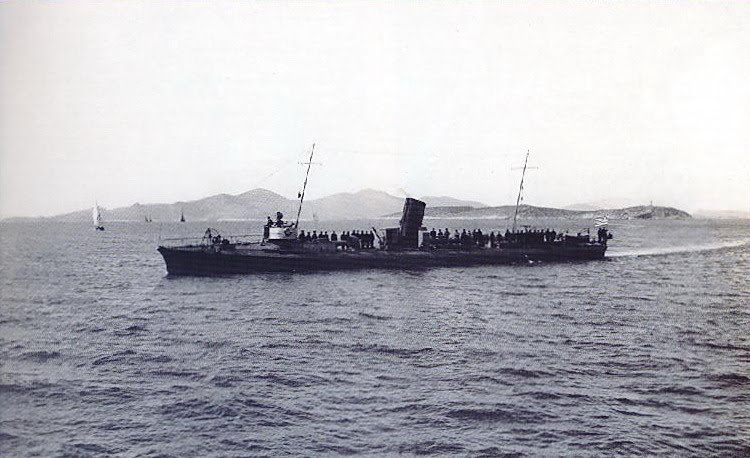

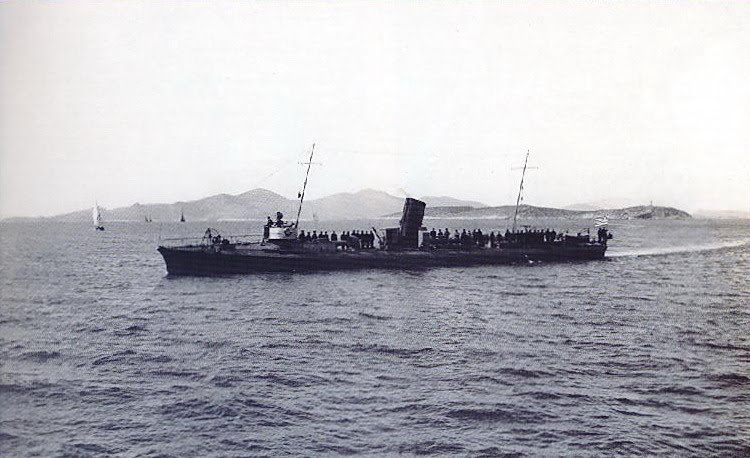

Lieutenant

Nikolaos Votsis scored a major success for Greek morale on 31 October: he sailed his

torpedo boat No. 11, under the cover of night, into the harbor of

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

, sank the old Ottoman ironclad battleship ''

Feth-i Bülend'' and escaped unharmed. On the same day, Greek troops of the Epirus Army seized the Ottoman naval base of

Preveza

Preveza (, ) is a city in the region of Epirus (region), Epirus, northwestern Greece, located on the northern peninsula of the mouth of the Ambracian Gulf. It is the capital of the Preveza (regional unit), regional unit of Preveza, which is the s ...

. The Ottomans scuttled the four ships present there, but the Greeks were able to salvage the Italian-built torpedo-boats ''Antalya'' and ''Tokat'', which were commissioned into the Greek Navy as ''Nikopolis'' and ''Tatoi'' respectively. On 9 November, the wooden Ottoman armed steamer ''Trabzon'' was intercepted and sunk by the Greek torpedo boat No. 14 under Lt.

Periklis Argyropoulos off

Ayvalık

Ayvalık (), formerly also known as Kydonies (), is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district of Balıkesir Province, Turkey. Its area is 305 km2, and its population is 75,126 (2024). It is a seaside town on the northwestern Aegean Se ...

.

=Confrontations off the Dardanelles

=

The main Ottoman fleet remained inside the

Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

for the early part of the war, while the Greek destroyers continuously patrolled the Straits' exit to report on a possible sortie. Kountouriotis suggested

mining

Mining is the Resource extraction, extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agriculture, agricultural processes, or feasib ...

the straits, but was not taken up for fear of international reactions.

[Fotakis (2005), p. 50] On 7 December, the head of the Ottoman fleet Tahir Bey was replaced by Ramiz Naman Bey, the leader of the hawkish faction among the officer corps. A new strategy was agreed, whereby the Ottomans were to take advantage of any absence of the Greek flagship ''

Averof'' to attack the other Greek ships. The Ottoman staff formulated a plan to lure a number of the Greek destroyers on patrol into a trap. A first such effort on 12 December failed due to boiler trouble, but the second try two days later resulted in an indecisive engagement between the Greek destroyers and the cruiser ''

Mecidiye''.

The war's first major fleet action, the

Naval Battle of Elli, was fought two days later, on . The Ottoman fleet, with four battleships, nine destroyers and six torpedo boats, sailed to the entrance of the straits. The lighter Ottoman vessels remained behind, but the battleship squadron moved on north under cover of the forts at

Kumkale and engaged the Greek fleet, coming from Imbros, at 9:40. Leaving the older battleships behind, Kountouriotis led the ''Averof'' into independent action: utilizing its superior speed, it cut across the Ottoman fleet's bow. Under fire from two sides, the Ottomans were quickly forced to withdraw to the Dardanelles.

[Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), p. 22] The whole engagement lasted less than an hour, in which the Ottoman fleet suffered heavy damage to the ''

Barbaros Hayreddin'' and 18 dead and 41 wounded (most during their disorderly retreat) and the Greeks one dead and seven wounded.

In the aftermath of Elli, on 20 December the energetic Lt. Commander

Rauf Bey was placed in effective command of the Ottoman fleet. Two days later he led his forces out, hoping again to trap the patrolling Greek destroyers between two divisions of the Ottoman fleet, one heading for Imbros and the other waiting at the entrance of the straits. The plan failed as the Greek ships quickly broke contact, while at the same time the ''Mecidiye'' came under attack by the Greek submarine ''

Delfin'', which launched a torpedo against it but missed; the first such attack in history.

During this time, the Ottoman Army continued to press upon a reluctant Navy a plan for the re-occupation of Tenedos, which the Greek destroyers used as a base, by an amphibious operation. The operation was scheduled for 4 January. On that day, weather conditions were ideal, and the fleet was ready, but the ''Yenihan'' regiment earmarked for the operation failed to arrive on time. The naval staff nevertheless ordered the fleet to sortie, and an engagement developed with the Greek fleet, without any significant results on either side. Similar sorties followed on 10 and 11 January, but the results of these "cat and mouse" operations were always the same: "the Greek destroyers always managed to remain outside the Ottoman warships' range, and each time the cruisers fired a few rounds before breaking off the chase."

In preparation for the next attempt to break the Greek blockade, the Ottoman Admiralty decided to create a diversion by sending the light cruiser ''

Hamidiye'', captained by Rauf Bey, to raid Greek merchant shipping in the Aegean. It was hoped that the ''Averof'', the only major Greek unit fast enough to catch the ''Hamidiye'', would be drawn in pursuit and leave the remainder of the Greek fleet weakened.

[Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), p. 26] In the event, ''Hamidiye'' slipped through the Greek patrols on the night of 14–15 January and bombarded the harbor of the Greek island of

Syros

Syros ( ), also known as Siros or Syra, is a Greece, Greek island in the Cyclades, in the Aegean Sea. It is south-east of Athens. The area of the island is and at the 2021 census it had 21,124 inhabitants.

The largest towns are Ermoupoli, Ano S ...

, sinking the Greek

auxiliary cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

''Makedonia'' which lay in anchor there (it was later raised and repaired). The ''Hamidiye'' then left the Aegean for the Eastern Mediterranean, making stops at

Beirut

Beirut ( ; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, just under half of Lebanon's population, which makes it the List of largest cities in the Levant region by populatio ...

and

Port Said

Port Said ( , , ) is a port city that lies in the northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, straddling the west bank of the northern mouth of the Suez Canal. The city is the capital city, capital of the Port S ...

before entering the

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

. Although providing a major morale boost for the Ottomans, the operation failed to achieve its primary objective, as Kountouriotis refused to leave his post and pursue the ''Hamidiye''.

[Hall (2000), p. 65]

Four days later, on , when the Ottoman fleet again sallied from the straits towards Lemnos, it was defeated for a second time in the

Naval Battle of Lemnos. This time, the Ottoman warships concentrated their fire on the ''Averof'', which again made use of its superior speed and tried to "

cross the T" of the Ottoman fleet. ''Barbaros Hayreddin'' was again heavily damaged, and the Ottoman fleet was forced to return to the shelter of the Dardanelles and their forts. The Ottomans suffered 41 killed and 101 wounded.

It was the last attempt of the Ottoman Navy to leave the Dardanelles, thereby leaving the Greeks dominant in the Aegean. On , a Greek

Farman MF.7, piloted by Lt.

Moutousis and with Ensign

Moraitinis as an observer, carried out an aerial reconnaissance of the Ottoman fleet in its anchorage at

Nagara, and launched four bombs on the anchored ships. Although it scored no hits, this operation is regarded as the first naval-air operation in military history.

General

Nikola Ivanov, commander of the

2nd Bulgarian Army, acknowledged the role of the Greek fleet in the overall Balkan League victory by stating that "the activity of the entire Greek fleet and above all the ''Averof'' was the chief factor in the general success of the allies".

End of the War

The

Treaty of London ended the war, but no one was left satisfied, and soon, the four allies fell out over the partition of

Macedonia. In June 1913, Bulgaria attacked Greece and Serbia, beginning the

Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict that broke out when Kingdom of Bulgaria, Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia and Kingdom of Greece, Greece, on 1 ...

, but was beaten back. The

Treaty of Bucharest, which concluded the war, left Greece with southern Epirus, the

southern-half of Macedonia, Crete and the Aegean islands, except for the

Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; , ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger and 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. This island group generally define ...

, which had been occupied by

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

in 1911. These gains nearly doubled Greece's area and population.

1914–1924: World War I, crises, and the first abolition of the monarchy

In March 1913, an anarchist,

Alexandros Schinas, assassinated King George in Thessaloniki, and his son came to the throne as Constantine I. Constantine was the first Greek king born in Greece and the first to be Greek Orthodox. His very name had been chosen in the spirit of romantic Greek nationalism (the ''

Megali Idea''), evoking the Byzantine emperors of that name. Besides, as the Commander-in-chief of the Greek Army during the

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars were two conflicts that took place in the Balkans, Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Kingdom of Greece (Glücksburg), Greece, Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, Kingdom of Montenegro, M ...

, his popularity was enormous, rivalled only by that of Venizelos, his Prime Minister.

When

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

broke out in 1914, despite Greece's treaty of alliance with Serbia, both leaders preferred to maintain a neutral stance. However, when, in early 1915, the

Allied Powers asked for Greek help in the

Dardanelles campaign, offering

Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

in exchange, their diverging views became apparent: Constantine had been educated in

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, was married to

Sophia of Prussia, sister of Kaiser

Wilhelm, and was convinced of the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

' victory. Venizelos, on the other hand, was an ardent

anglophile, and believed in an Allied victory.

Since Greece, a maritime country, could not oppose the mighty

British navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, and citing the need for a respite after two wars, King Constantine favoured continued neutrality, while Venizelos actively sought Greek entry in the war on the Allied side. Venizelos resigned, but won the next

elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

, and again formed the government. When

Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

entered the war as a German ally in October 1915, Venizelos invited

Entente forces into Greece (the

Salonika front), for which he was again dismissed by Constantine.

In August 1916, after several incidents where both combatants encroached upon the still theoretically neutral Greek territory, Venizelist officers rose up in Allied-controlled Thessaloniki, and Venizelos established a

separate government there. Constantine was now ruling only in what was Greece before the Balkan Wars ("

Old Greece"), and his government was subject to repeated humiliations from the Allies. In November 1916 the French occupied

Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; ; , Ancient: , Katharevousa: ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens city centre along the east coast of the Saronic Gulf in the Ath ...

, bombarded Athens and forced the Greek fleet to surrender. The royalist troops fired at them, leading to a battle between French and Greek royalist forces. There were also riots against supporters of Venizelos in Athens (the ).

Following the

February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

in Russia, however, the Tsar's support for his cousin was removed, and Constantine was forced to leave the country, without actually abdicating in June 1917. His second son

Alexander

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here ar ...

became king, while the remaining royal family and the most prominent royalists followed into exile. Venizelos now led a superficially united Greece into the war on the Allied side, but underneath the surface, the division of Greek society into

Venizelists and anti-Venizelists, the so-called

National Schism, became more entrenched.

With the end of the war in November 1918, the moribund Ottoman Empire was ready to be carved up amongst the victors, and Greece now expected the Allied Powers to deliver on their promises. In no small measure through the diplomatic efforts of Venizelos, Greece secured

Western Thrace in the

Treaty of Neuilly in November 1919 and

Eastern Thrace

East Thrace or Eastern Thrace, also known as Turkish Thrace or European Turkey, is the part of Turkey that is geographically in Southeast Europe. Turkish Thrace accounts for 3.03% of Turkey's land area and 15% of its population. The largest c ...

and a zone around

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; , or ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean Sea, Aegean coast of Anatolia, Turkey. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna ...

in western

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

(already under

Greek administration since May 1919) in the

Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres () was a 1920 treaty signed between some of the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire, but not ratified. The treaty would have required the cession of large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, ...

of August 1920. The future of

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

was left to be determined. But at the same time, a

nationalist movement had arisen in Turkey, led by

Mustafa Kemal (later Kemal Atatürk), who set up a rival government in

Ankara

Ankara is the capital city of Turkey and List of national capitals by area, the largest capital by area in the world. Located in the Central Anatolia Region, central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5,290,822 in its urban center ( ...

and was engaged in fighting the Greek army.

At this point, nevertheless, the fulfillment of the ''Megali Idea'' seemed near. Yet so deep was the rift in Greek society, that on his return to Greece, an assassination attempt was made on Venizelos by two former royalist officers. Venizelos'

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

lost the

elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

called in November 1920, and in a

referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

shortly after, the Greek people voted for the return of King Constantine from exile, following the sudden death of Alexander. The United Opposition, which had campaigned on the slogan of an end to the

war in Anatolia, instead intensified it. However, the royalist restoration had dire consequences: many veteran Venizelist officers were dismissed or left the army, while Italy and France found the return of the hated Constantine a useful pretext for switching their support to Kemal. Finally, in August 1922, the Turkish army shattered the Greek front, and

took Smyrna.

The Greek army evacuated not only Anatolia but also Eastern Thrace and the islands of

Imbros and

Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos''; ), or Bozcaada in Turkish language, Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada, Çanakkale, Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Provinc ...

(

Treaty of Lausanne). A

compulsory population exchange was agreed between the two countries, with over 1.5 million Christians and almost half a million Muslims being uprooted. This catastrophe marked the end of the ''Megali Idea'', and left Greece financially exhausted, demoralised, and having to house and feed a proportionately huge number of

refugees

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

.

The catastrophe deepened the political crisis, with the returning army rising under Venizelist officers and forcing King Constantine to abdicate again, in September 1922, in favour of his firstborn son,

George II. The "Revolutionary Committee", headed by Colonels

Stylianos Gonatas (soon to become Prime Minister) and

Nikolaos Plastiras engaged in a witch-hunt against the royalists, culminating in the "

Trial of the Six". In October 1923,

elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

were called for December, which would form a National Assembly with powers to draft a new constitution. Following a

failed royalist coup, the monarchist parties abstained, leading to a landslide for the Liberals and their allies. King George II was asked to leave the country, and on 25 March 1924,

Alexandros Papanastasiou proclaimed the

Second Hellenic Republic

The Second Hellenic Republic is a modern Historiography, historiographical term used to refer to the Greece, Greek state during a period of republican governance between 1924 and 1935. To its contemporaries it was known officially as the Hellenic ...

, ratified by

plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

a month later.

Restoration of Monarchy and the 4th of August Regime

On 10 October 1935, a few months after he suppressed

a Venizelist Coup in March 1935,

Georgios Kondylis, the former Venizelist stalwart, abolished the Republic in another coup and declared the monarchy restored. A rigged

plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

confirmed the regime change (with 97.88% of votes), and King George II returned.

King George II immediately dismissed Kondylis and appointed Professor

Konstantinos Demertzis

Konstantinos Demertzis (; January 12, 1876, in Athens – April 13, 1936, in Athens) was a Greek academic and politician. He was the 49th Prime Minister of Greece from November 1935 to April 1936. Demertzis died during his mandate, of a heart att ...

as interim Prime Minister. Venizelos meanwhile, in exile, urged an end to the conflict over the monarchy given the threat to Greece from the rise of

Fascist Italy

Fascist Italy () is a term which is used in historiography to describe the Kingdom of Italy between 1922 and 1943, when Benito Mussolini and the National Fascist Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictatorship. Th ...

. His successors as Liberal leader,

Themistoklis Sophoulis and

Georgios Papandreou

Georgios Papandreou (, ''Geórgios Papandréou''; 13 February 1888 – 1 November 1968) was a Greek politician, the founder of the Papandreou political dynasty. He served three terms as the prime minister of Greece (1944–1945, 1963, 1964 ...

, agreed, and the restoration of the monarchy was accepted. The

1936 elections resulted in a

hung parliament