Khariji on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Kharijites (, singular ), also called al-Shurat (), were an Islamic sect which emerged during the

The Kharijites were the first sect to arise within Islam. They originated during the First Fitna, the struggle for political leadership over the Muslim community (), following the assassination in 656 of the third caliph

The Kharijites were the first sect to arise within Islam. They originated during the First Fitna, the struggle for political leadership over the Muslim community (), following the assassination in 656 of the third caliph

As Ali marched back to his capital at Kufa, widespread resentment toward the arbitration developed in his army. As many as 12,000 dissenters seceded from the army and set up camp in Harura, a place near Kufa. They thus became known as the Harurites. They held that Uthman had deserved his death because of his nepotism and not ruling according to the Qur'an, and that Ali was the legitimate caliph, while Mu'awiya was a rebel. They believed that the Qur'an clearly stated that as a rebel Mu'awiya was not entitled to arbitration, but rather should be fought until he repented, pointing to the Qur'anic verse:

They held that in agreeing to arbitration, Ali committed the grave sin of rejecting God's judgment () and attempted to substitute human judgment for God's clear injunction, which prompted their motto 'judgment belongs to God alone'. From this expression, which they were the first to adopt as a motto, they became known as the .

Ali visited the Harura camp and attempted to regain the dissidents' support, arguing that it was they who had forced him to accept the arbitration proposal despite his reservations. They acknowledged that they had sinned but insisted that they repented and asked him to do the same, which Ali then did in general and ambiguous terms. The troops at Harura subsequently restored their allegiance to Ali and returned to Kufa, on the condition that the war against Mu'awiya be resumed within six months.

As Ali marched back to his capital at Kufa, widespread resentment toward the arbitration developed in his army. As many as 12,000 dissenters seceded from the army and set up camp in Harura, a place near Kufa. They thus became known as the Harurites. They held that Uthman had deserved his death because of his nepotism and not ruling according to the Qur'an, and that Ali was the legitimate caliph, while Mu'awiya was a rebel. They believed that the Qur'an clearly stated that as a rebel Mu'awiya was not entitled to arbitration, but rather should be fought until he repented, pointing to the Qur'anic verse:

They held that in agreeing to arbitration, Ali committed the grave sin of rejecting God's judgment () and attempted to substitute human judgment for God's clear injunction, which prompted their motto 'judgment belongs to God alone'. From this expression, which they were the first to adopt as a motto, they became known as the .

Ali visited the Harura camp and attempted to regain the dissidents' support, arguing that it was they who had forced him to accept the arbitration proposal despite his reservations. They acknowledged that they had sinned but insisted that they repented and asked him to do the same, which Ali then did in general and ambiguous terms. The troops at Harura subsequently restored their allegiance to Ali and returned to Kufa, on the condition that the war against Mu'awiya be resumed within six months.

Ali refused to denounce the arbitration proceedings, which continued despite the reconciliation with the troops at Harura. In March 658, Ali sent a delegation, led by Abu Musa Ash'ari, to carry out the talks. The troops opposed to the arbitration thereafter condemned Ali's rule and elected the pious

Ali refused to denounce the arbitration proceedings, which continued despite the reconciliation with the troops at Harura. In March 658, Ali sent a delegation, led by Abu Musa Ash'ari, to carry out the talks. The troops opposed to the arbitration thereafter condemned Ali's rule and elected the pious

The accession of Mu'awiya, the original enemy of the Kharijites, to the caliphate in August 661 provided the new impetus for Kharijite rebellion. Those Kharijites at Nahrawan who had been unwilling to fight Ali and had left the battlefield, rebelled against Mu'awiya. Under the leadership of Farwa ibn Nawfal al-Ashja'i of the

The accession of Mu'awiya, the original enemy of the Kharijites, to the caliphate in August 661 provided the new impetus for Kharijite rebellion. Those Kharijites at Nahrawan who had been unwilling to fight Ali and had left the battlefield, rebelled against Mu'awiya. Under the leadership of Farwa ibn Nawfal al-Ashja'i of the

After the death of Mu'awiya in 680, civil war ensued over leadership of the Muslim community. The people of the

After the death of Mu'awiya in 680, civil war ensued over leadership of the Muslim community. The people of the

Distinct Sufriyya and Ibadiyya sects are attested from the early eighth century in North Africa and Oman. The two differed in association with different tribal groups and competed for popular support. During the last days of the Umayyad empire, a major Sufri revolt erupted in Iraq in 744. It was at first led by Sa'id ibn Bahdal al-Shaybani, and after his death from plague, Dahhak ibn Qays al-Shaybani. Joined by many more Sufriyya from other parts of the empire, he captured Kufa in April 745 and later Wasit, which had replaced Kufa as the regional capital under Hajjaj. At this stage even some Umayyad officials, including two sons of former caliphs ( Sulayman, son of

Distinct Sufriyya and Ibadiyya sects are attested from the early eighth century in North Africa and Oman. The two differed in association with different tribal groups and competed for popular support. During the last days of the Umayyad empire, a major Sufri revolt erupted in Iraq in 744. It was at first led by Sa'id ibn Bahdal al-Shaybani, and after his death from plague, Dahhak ibn Qays al-Shaybani. Joined by many more Sufriyya from other parts of the empire, he captured Kufa in April 745 and later Wasit, which had replaced Kufa as the regional capital under Hajjaj. At this stage even some Umayyad officials, including two sons of former caliphs ( Sulayman, son of

In 745, Abd Allah ibn Yahya al-Kindi established the first Ibadi state in Hadramawt, and captured Yemen in 746. His lieutenant, Abu Hamza Mukhtar ibn Aws al-Azdi, later conquered Mecca and Medina. The Umayyads defeated and killed Abu Hamza and Ibn Yahya in 748 and the first Ibadi state collapsed. An Ibadi state was established in Oman in 750 after the fall of Abu Yahya, but fell to the Abbasids in 752. It was followed by the establishment of another Ibadi state in 793, which survived for a century until the Abbasid recapture of Oman in 893. Abbasid influence in Oman was mostly nominal, and Ibadi

In 745, Abd Allah ibn Yahya al-Kindi established the first Ibadi state in Hadramawt, and captured Yemen in 746. His lieutenant, Abu Hamza Mukhtar ibn Aws al-Azdi, later conquered Mecca and Medina. The Umayyads defeated and killed Abu Hamza and Ibn Yahya in 748 and the first Ibadi state collapsed. An Ibadi state was established in Oman in 750 after the fall of Abu Yahya, but fell to the Abbasids in 752. It was followed by the establishment of another Ibadi state in 793, which survived for a century until the Abbasid recapture of Oman in 893. Abbasid influence in Oman was mostly nominal, and Ibadi

Most Kharijite leaders in the Umayyad period were Arabs. Of these, the northern Arabs were the overwhelming majority. Only six or seven revolts led by a southern Arab have been reported, their leaders hailing from the tribes of

Most Kharijite leaders in the Umayyad period were Arabs. Of these, the northern Arabs were the overwhelming majority. Only six or seven revolts led by a southern Arab have been reported, their leaders hailing from the tribes of

First Fitna

The First Fitna ( ar, فتنة مقتل عثمان, fitnat maqtal ʻUthmān, strife/sedition of the killing of Uthman) was the first civil war in the Islamic community. It led to the overthrow of the Rashidun Caliphate and the establishment of ...

(656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the conflict with his challenger, Mu'awiya

Mu'awiya I ( ar, معاوية بن أبي سفيان, Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān; –April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

, at the Battle of Siffin

The Battle of Siffin was fought in 657 CE (37 AH) between Ali ibn Abi Talib, the fourth of the Rashidun Caliphs and the first Shia Imam, and Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, the rebellious governor of Syria. The battle is named after its location ...

in 657. They asserted that "judgment belongs to God alone", which became their motto, and that rebels such as Mu'awiya had to be fought and overcome according to Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

ic injunctions. Ali defeated the Kharijites at the Battle of Nahrawan

The Battle of Nahrawan ( ar, معركة النهروان, Ma'rakat an-Nahrawān) was fought between the army of Caliph Ali and the rebel group Kharijites in July 658 CE (Safar 38 AH). They used to be a group of pious allies of Ali during the ...

in 658, but their insurrection continued. Ali was assassinated in 661 by a Kharijite seeking revenge for the defeat at Nahrawan.

After Mu'awiya's establishment of the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

in 661, his governors kept the Kharijites in check. The power vacuum caused by the Second Fitna

The Second Fitna was a period of general political and military disorder and civil war in the Islamic community during the early Umayyad Caliphate., meaning trial or temptation) occurs in the Qur'an in the sense of test of faith of the believer ...

(680–692) allowed for the resumption of the Kharijites' anti-government rebellion and the Kharijite factions of the Azariqa

The Azariqa ( ar, الأزارقة, ''al-azāriqa'') were an extremist branch of Khawarij, who followed the leadership of Nafi ibn al-Azraq al-Hanafi. Adherents of Azraqism participated in an armed struggle against the rulers of the Umayyad Cali ...

and Najdat came to control large areas in Persia and Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Pl ...

. Internal disputes and fragmentation weakened them considerably before their defeat by the Umayyads in 696–699. In the 740s, large-scale Kharijite rebellions broke out across the caliphate, but all were eventually suppressed. Although the Kharijite revolts continued into the Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

period (750–1258), the most militant Kharijite groups were gradually eliminated, and were replaced by the non-activist Ibadiyya

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

, who survive to this day in Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

and some parts of North Africa. They, however, deny any links with the Kharijites of the Second Muslim Civil War and beyond, condemning them as extremists.

The Kharijites believed that any Muslim, irrespective of his descent or ethnicity, qualified for the role of caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, provided they were morally irreproachable. It was the duty of Muslims to rebel against and depose caliphs who sinned. Most Kharijite groups branded as unbeliever

An infidel (literally "unfaithful") is a person accused of disbelief in the central tenets of one's own religion, such as members of another religion, or the irreligious.

Infidel is an ecclesiastical term in Christianity around which the Churc ...

s Muslims who had committed a grave sin, and the most militant declared killing of such unbelievers to be licit, unless they repented. Many Kharijites were skilled orators and poets, and the major themes of their poetry were piety

Piety is a virtue which may include religious devotion or spirituality. A common element in most conceptions of piety is a duty of respect. In a religious context piety may be expressed through pious activities or devotions, which may vary among ...

and martyrdom

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

. The Kharijites of the eighth and ninth centuries participated in theological debates and, in the process, contributed to mainstream Islamic theology

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding '' ʿaqīdah'' (creed). The main schools of Islamic Theology include the Qadariyah, Falasifa, Jahmiyya, Murji'ah, Muʿtazila, Batin ...

.

What is known about Kharijite history and doctrines derives from non-Kharijite authors of the ninth and tenth centuries, and is hostile toward the sect. The absence of the Kharijite version of their history has made unearthing their true motives difficult. Traditional Muslim historical sources and mainstream Muslims have viewed the Kharijites as religious extremists who left the Muslim community. Many modern Muslim extremist groups have been compared to the Kharijites for their radical ideology and militancy. On the other hand, some modern Arab historians have stressed the egalitarian and proto-democratic tendencies of the Kharijites. Modern, academic historians are generally divided in attributing the Kharijite phenomenon to purely religious motivations, economic factors, or a Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arabs, Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert ...

(nomadic Arab) challenge to the establishment of an organized state, with some rejecting the traditional account of the movement having started at Siffin.

Etymology

The term was used as anexonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group ...

by their opponents for leaving the army of Caliph Ali during the First Fitna

The First Fitna ( ar, فتنة مقتل عثمان, fitnat maqtal ʻUthmān, strife/sedition of the killing of Uthman) was the first civil war in the Islamic community. It led to the overthrow of the Rashidun Caliphate and the establishment of ...

. The term comes from the Arabic root

The roots of verbs and most nouns in the Semitic languages are characterized as a sequence of consonants or "radicals" (hence the term consonantal root). Such abstract consonantal roots are used in the formation of actual words by adding the vowe ...

, which has the primary meaning "to leave" or "to get out", as in the basic word , , "to go out". The term is anglicized to 'Kharijites' from the singular . They called themselves ("the Exchangers"), which they understood within the context of Islamic scripture () and philosophy to mean "those who have traded the mortal life () for the other life ith God

The Ith () is a ridge in Germany's Central Uplands which is up to 439 m high. It lies about 40 km southwest of Hanover and, at 22 kilometres, is the longest line of crags in North Germany.

Geography

Location

The Ith is immediatel ...

()".

Primary and classical sources

Almost no primary Kharijite sources survive, except for works by authors from the sole surviving Kharijite sect ofIbadiyya

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

, and excerpts in non-Kharijite works. As the latter are the main sources of information and date to later periods, the Kharijite material has suffered alterations and distortions during transmission, collection, and classification.

Non-Kharijite sources fall mainly into two categories: histories and heresiographical works—the so-called (sects) literature. The histories were written significantly later than the actual events, and many of the theological and political disputes among the early Muslims had been settled by then. As representatives of the emerging orthodoxy, the Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a dis ...

as well as Shi'a

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his S ...

authors of these works looked upon the original events through the lens of this orthodox viewpoint. The bulk of information regarding the Kharijites, however, comes from the second category. These sources are outright polemical, as the authors tend to portray their own sect as the true representative of original Islam and are consequently hostile to the Kharijites. Although the authors in both categories used earlier Kharijite as well as non-Kharijite sources, which are no longer extant, their rendering of the events has been heavily altered by literary topoi.

Based on a hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

(saying or tradition attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

) prophesying the emergence of 73 sects in Islam, of which one would be saved () and the rest doomed as deviant, the heresiographers were mainly concerned with classifying what they considered to be deviant sects and their heretical doctrines. Consequently, views of certain sects were altered to fit into classification schemes, and sometimes fictitious sects were invented. Moreover, the reports are often confused and contradictory, rendering a reconstruction of 'what actually happened' and the true motives of the Kharijites, which is free of later interpolations, especially difficult. According to the historians Hannah-Lena Hagemann and Peter Verkinderen, the sources sometimes used the Kharijites as a literary tool to address other issues, which were otherwise unrelated to the Kharijites, such as "the status of Ali, the dangers of communal strife, or the legal aspects of rebellion". The Ibadi sources, on the other hand, are hagiographical and are concerned with preserving the group identity. Toward this purpose, stories are sometimes created, or real events altered, in order to romanticize and valorize early Kharijite revolts and their leaders as the anchors of the group identity. These too are hostile to other Kharijite groups. The sources, whether Ibadi, historiographical, or heresiographical, do not necessarily report events as they actually happened. They rather show how their respective authors viewed, and wanted their readers to view, these events.

The sources in the historiographical category include the ''History

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

'' of al-Tabari

( ar, أبو جعفر محمد بن جرير بن يزيد الطبري), more commonly known as al-Ṭabarī (), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari ...

(d. 923), of al-Baladhuri

ʾAḥmad ibn Yaḥyā ibn Jābir al-Balādhurī ( ar, أحمد بن يحيى بن جابر البلاذري) was a 9th-century Muslim historian. One of the eminent Middle Eastern historians of his age, he spent most of his life in Baghdad and e ...

(d. 892), of al-Mubarrad

Al-Mubarrad () (al-Mobarrad), or Abū al-‘Abbās Muḥammad ibn Yazīd (c. 826c. 898), was a native of Baṣrah. He was a philologist, biographer and a leading grammarian of the School of Basra, a rival to the School of Kufa. In 860 he was ...

(d. 899), and of al-Mas'udi (d. 956). Other notable sources include the histories of Ibn Athir Ibn Athīr is the family name of three brothers, all famous in Arabic literature, born at Jazīrat ibn Umar (today's ''Cizre'' nowadays in south-eastern Turkey) in upper Mesopotamia. The ibn al-Athir brothers belonged to the Shayban lineage of the ...

(d. 1233), and Ibn Kathir

Abū al-Fiḍā’ ‘Imād ad-Dīn Ismā‘īl ibn ‘Umar ibn Kathīr al-Qurashī al-Damishqī (Arabic: إسماعيل بن عمر بن كثير القرشي الدمشقي أبو الفداء عماد; – 1373), known as Ibn Kathīr (, was ...

(d. 1373), but these have drawn most of their material from al-Tabari. The core of the information in these historiographical sources is based on the works of earlier historians like Abu Mikhnaf (d. 773), Abu Ubayda

ʿĀmir ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Jarrāḥ ( ar, عامر بن عبدالله بن الجراح; 583–639 CE), better known as Abū ʿUbayda ( ar, أبو عبيدة ) was a Muslim commander and one of the Companions of the Islamic prophet M ...

(d. 825), and al-Mada'ini

Abū l-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbdallāh ibn Abī Sayf al-Qurashī l-Madāʾinī () (752/3–843), better known by his '' nisba'' of al-Madāʾinī ("from al-Mada'in"), was a scholar of Iranian descent who wrote in Arabic and was active ...

(d. 843). The authors of the heresiographical category include al-Ash'ari (d. 935), al-Baghdadi (d. 1037), Ibn Hazm

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Aḥmad ibn Saʿīd ibn Ḥazm ( ar, أبو محمد علي بن احمد بن سعيد بن حزم; also sometimes known as al-Andalusī aẓ-Ẓāhirī; 7 November 994 – 15 August 1064Ibn Hazm. ' (Preface). Tr ...

(d. 1064), al-Shahrastani

Tāj al-Dīn Abū al-Fath Muhammad ibn `Abd al-Karīm ash-Shahrastānī ( ar, تاج الدين أبو الفتح محمد بن عبد الكريم الشهرستاني; 1086–1153 CE), also known as Muhammad al-Shahrastānī, was an influenti ...

(d. 1153), and others. Notable among the surviving Ibadi works is the eighth-century heresiographical writing of Salim ibn Dhakwan. It distinguishes Ibadism from other Kharijite groups which it treats as extremists. ''Al-Kashf wa'l-Bayan'', a 12th-century work by al-Qalhati, is another example of Ibadi heresiographies and discusses the origins of the Kharijites and the divisions within the Kharijite movement.

Origin

The Kharijites were the first sect to arise within Islam. They originated during the First Fitna, the struggle for political leadership over the Muslim community (), following the assassination in 656 of the third caliph

The Kharijites were the first sect to arise within Islam. They originated during the First Fitna, the struggle for political leadership over the Muslim community (), following the assassination in 656 of the third caliph Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic prop ...

.

The later years of Uthman's reign were marked by growing discontent from multiple groups within the Muslim community. His favoritism and enrichment of his Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

relatives was disdained by the Muslim elite in Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the Holiest sites in Islam, second-holiest city in Islam, ...

. The early Muslim settlers of the garrison towns of Kufa

Kufa ( ar, الْكُوفَة ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Najaf a ...

and Fustat

Fusṭāṭ ( ar, الفُسطاط ''al-Fusṭāṭ''), also Al-Fusṭāṭ and Fosṭāṭ, was the first capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, and the historical centre of modern Cairo. It was built adjacent to what is now known as Old Cairo by t ...

, in the conquered regions of Iraq and Egypt, felt their status threatened by several factors during this period. These were Uthman's interference in provincial affairs, overcrowding of the garrison towns by a continuous tribal influx from Arabia, diminishing revenue from the conquests, and the growing influence of the pre-Islamic tribal nobility. Opposition by the Iraqi early-comers, who became known as the (which probably means 'the Qur'an reciters'), and the Egyptians turned into open rebellion in 656. Encouraged by the disaffected Medinese elite, the rebels marched on Medina, killing Uthman in June 656. His murder sparked the civil war.

Afterward, Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law Ali became caliph with the help of the people of Medina and the rebels. He was soon challenged by Muhammad's early companions, Talha ibn Ubayd Allah and Zubayr ibn al-Awwam

Az Zubayr ( ar, الزبير) is a city in and the capital of Al-Zubair District, part of the Basra Governorate of Iraq. The city is just south of Basra. The name can also refer to the old Emirate of Zubair.

The name is also sometimes written ...

, and Muhammad's widow, A'isha

Aisha ( ar, , translit=ʿĀʾisha bint Abī Bakr; , also , ; ) was Muhammad's third and youngest wife. In Islamic writings, her name is thus often prefixed by the title "Mother of the Believers" ( ar, links=no, , ʾumm al- muʾminīn), referr ...

, who held that his election was invalid as it involved Uthman's murderers and hence a (consultative assembly) had to be called to elect a new caliph. Ali defeated them in November 656 at the Battle of the Camel

The Battle of the Camel, also known as the Battle of Jamel or the Battle of Basra, took place outside of Basra, Iraq, in 36 AH (656 CE). The battle was fought between the army of the fourth caliph Ali, on one side, and the rebel army led by ...

. Later, Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, Uthman's kinsman and the governor of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, denounced Ali's election, holding that Uthman's murderers were in Ali's camp and evaded punishment. The two faced each other at the Battle of Siffin

The Battle of Siffin was fought in 657 CE (37 AH) between Ali ibn Abi Talib, the fourth of the Rashidun Caliphs and the first Shia Imam, and Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, the rebellious governor of Syria. The battle is named after its location ...

in July 657. On the verge of defeat, Mu'awiya ordered his soldiers to hoist leaves of the Qur'an () on their lances, a signal to stop the fight and negotiate peace. The in Ali's army were moved by the gesture, which they interpreted as an appeal to the Book of God, and demanded that Ali halt the fighting immediately. Although initially unwilling, he yielded under pressure and threats of violence against him by the . An arbitration committee composed of representatives of Ali and Mu'awiya was established with a mandate to settle the dispute according to the Qur'an and the . While most of Ali's army accepted the agreement, one group, which included many Tamim tribesmen, vehemently objected to the arbitration and raised the slogan 'judgment belongs to God alone' ().

Harura

As Ali marched back to his capital at Kufa, widespread resentment toward the arbitration developed in his army. As many as 12,000 dissenters seceded from the army and set up camp in Harura, a place near Kufa. They thus became known as the Harurites. They held that Uthman had deserved his death because of his nepotism and not ruling according to the Qur'an, and that Ali was the legitimate caliph, while Mu'awiya was a rebel. They believed that the Qur'an clearly stated that as a rebel Mu'awiya was not entitled to arbitration, but rather should be fought until he repented, pointing to the Qur'anic verse:

They held that in agreeing to arbitration, Ali committed the grave sin of rejecting God's judgment () and attempted to substitute human judgment for God's clear injunction, which prompted their motto 'judgment belongs to God alone'. From this expression, which they were the first to adopt as a motto, they became known as the .

Ali visited the Harura camp and attempted to regain the dissidents' support, arguing that it was they who had forced him to accept the arbitration proposal despite his reservations. They acknowledged that they had sinned but insisted that they repented and asked him to do the same, which Ali then did in general and ambiguous terms. The troops at Harura subsequently restored their allegiance to Ali and returned to Kufa, on the condition that the war against Mu'awiya be resumed within six months.

As Ali marched back to his capital at Kufa, widespread resentment toward the arbitration developed in his army. As many as 12,000 dissenters seceded from the army and set up camp in Harura, a place near Kufa. They thus became known as the Harurites. They held that Uthman had deserved his death because of his nepotism and not ruling according to the Qur'an, and that Ali was the legitimate caliph, while Mu'awiya was a rebel. They believed that the Qur'an clearly stated that as a rebel Mu'awiya was not entitled to arbitration, but rather should be fought until he repented, pointing to the Qur'anic verse:

They held that in agreeing to arbitration, Ali committed the grave sin of rejecting God's judgment () and attempted to substitute human judgment for God's clear injunction, which prompted their motto 'judgment belongs to God alone'. From this expression, which they were the first to adopt as a motto, they became known as the .

Ali visited the Harura camp and attempted to regain the dissidents' support, arguing that it was they who had forced him to accept the arbitration proposal despite his reservations. They acknowledged that they had sinned but insisted that they repented and asked him to do the same, which Ali then did in general and ambiguous terms. The troops at Harura subsequently restored their allegiance to Ali and returned to Kufa, on the condition that the war against Mu'awiya be resumed within six months.

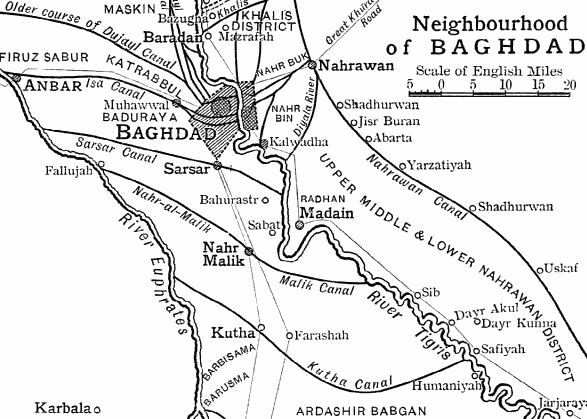

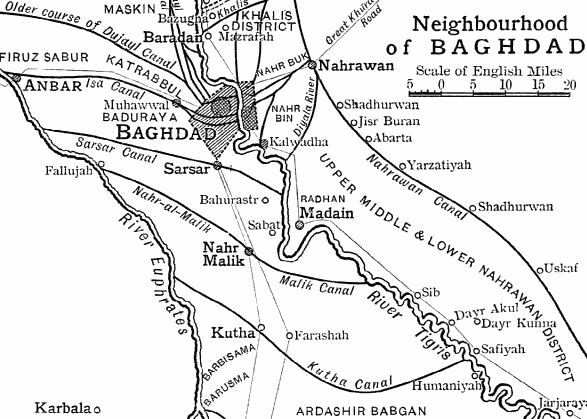

Nahrawan

Ali refused to denounce the arbitration proceedings, which continued despite the reconciliation with the troops at Harura. In March 658, Ali sent a delegation, led by Abu Musa Ash'ari, to carry out the talks. The troops opposed to the arbitration thereafter condemned Ali's rule and elected the pious

Ali refused to denounce the arbitration proceedings, which continued despite the reconciliation with the troops at Harura. In March 658, Ali sent a delegation, led by Abu Musa Ash'ari, to carry out the talks. The troops opposed to the arbitration thereafter condemned Ali's rule and elected the pious Abd Allah ibn Wahb al-Rasibi

ʿAbd Allāh ibn Wahb al-Rāsibī ( ar, عبد الله بن وهب الراسبي; died 17 July 658 AD) was an early leader of the Khārijites., calls him "the first ‘Kharijite’ caliph". Of the Bajīla tribe, he was a '' tābiʿī'', one wh ...

as their caliph. In order to evade detection, they moved out of Kufa in small groups and went to a place called Nahrawan on the east bank of the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

. Some five hundred of their Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

n comrades were informed and joined them in Nahrawan, numbering reportedly up to 4,000 men. They declared Ali and his followers as unbelievers, and are held to have killed several people who did not share their views.

In the meantime, the arbitrators declared that Uthman had been killed unjustly by the rebels. They could not agree on any other substantive matters and the process collapsed. Ali denounced the conduct of Abu Musa and Mu'awiya's lead arbitrator Amr ibn al-As

( ar, عمرو بن العاص السهمي; 664) was the Arab commander who led the Muslim conquest of Egypt and served as its governor in 640–646 and 658–664. The son of a wealthy Qurayshite, Amr embraced Islam in and was assigned impo ...

as contrary to the Qur'an and the , and rallied his supporters for a renewed war against Mu'awiya. He invited the Kharijites to join him as before. They refused, pending his acknowledgement of having gone astray and his repentance. Seeing no chance of reconciliation, Ali decided to depart for Syria without them. On the way, however, he received news of the Kharijites' murder of a traveler, which then was followed by murder of his envoy, who had been sent to investigate. He was urged by his followers, who feared for their families and property in Kufa, to deal with the Kharijites first. After the Kharijites refused to surrender the murderers, Ali's men attacked their camp, inflicting a heavy defeat on them at the Battle of Nahrawan

The Battle of Nahrawan ( ar, معركة النهروان, Ma'rakat an-Nahrawān) was fought between the army of Caliph Ali and the rebel group Kharijites in July 658 CE (Safar 38 AH). They used to be a group of pious allies of Ali during the ...

(July 658), in which al-Rasibi and most of his supporters were slain. Around 1,200 Kharijites surrendered and were spared. The bloodshed sealed the split of the Kharijites from Ali's followers, and they continued to launch insurrections against the caliphate. Five small Kharijite revolts following Nahrawan, involving about 200 men each, were suppressed during Ali's rule. The Kharijite calls for revenge ultimately led to Ali's assassination by the Kharijite Abd al-Rahman ibn Muljam

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Muljam al-Murādī ( ar, عبد الرحمن بن ملجم المرادي) was a Kharijite primarily known for having assassinated Ali ibn Abi Talib, the fourth caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate.

Assassination plot

There ...

. The latter killed Ali with a poisoned sword while Ali was leading morning prayers on 26 January 661 in the Kufa mosque.

Later history

Under Mu'awiya

The accession of Mu'awiya, the original enemy of the Kharijites, to the caliphate in August 661 provided the new impetus for Kharijite rebellion. Those Kharijites at Nahrawan who had been unwilling to fight Ali and had left the battlefield, rebelled against Mu'awiya. Under the leadership of Farwa ibn Nawfal al-Ashja'i of the

The accession of Mu'awiya, the original enemy of the Kharijites, to the caliphate in August 661 provided the new impetus for Kharijite rebellion. Those Kharijites at Nahrawan who had been unwilling to fight Ali and had left the battlefield, rebelled against Mu'awiya. Under the leadership of Farwa ibn Nawfal al-Ashja'i of the Banu Murra

Banu Murra () was a tribe during the era of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. They participated in the Battle of the Trench.Rodinson, ''Muhammad: Prophet of Islam'', p. 208.

They were members of the Ghatafan tribe

See also

*List of battles of Muham ...

, some 500 of them attacked Mu'awiya's camp at Nukhayla (a place outside Kufa) where he was taking the Kufans' oath of allegiance

An oath of allegiance is an oath whereby a subject or citizen acknowledges a duty of allegiance and swears loyalty to a monarch or a country. In modern republics, oaths are sworn to the country in general, or to the country's constitution. Fo ...

. In the ensuing battle, the Kharijites repelled the initial sortie by Mu'awiya's troops, but were eventually defeated and most of them killed. Seven more Kufan Kharijite uprisings, with rebel numbers in individual revolts varying between 20 and 400, were defeated by the governor Mughira ibn Shu'ba. The best known of these revolts was that of Mustawrid ibn Ullafa, who was recognized as caliph by the Kufan Kharijites in 663. With about 300 followers, he left Kufa and moved to Behrasir. There, he confronted the deputy governor Simak ibn Ubayd al-Absi and invited him to denounce Uthman and Ali "who had made innovations in the religion and denied the holy book". Simak refused and Mustawrid, instead of engaging him directly, decided to exhaust and fragment Simak's forces by forcing them into pursuit. Moving onto Madhar near Basra, Mustawrid was overtaken by a 300-strong advance party of Simak's forces. Although Mustawrid was able to withstand this small force, he fled again toward Kufa when the main body of Simak's forces, under the command of Ma'qil ibn Qays, arrived. Eluding Ma'qil's advance guard of 600 men, Mustawrid led a surprise attack on Ma'qil's main force, destroying it. The advance guard returned in the meantime and attacked the Kharijites from the rear. Nearly all of them were slain.

Kufan Kharijism died out around 663, and Basra became the center of Kharijite disturbances. Ziyad ibn Abihi and his son Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad

ʿUbayd Allāh ibn Ziyād ( ar, عبيد الله بن زياد, ʿUbayd Allāh ibn Ziyād) was the Umayyad governor of Basra, Kufa and Khurasan during the reigns of caliphs Mu'awiya I and Yazid I, and the leading general of the Umayyad army unde ...

, who successively became governors of Iraq, dealt harshly with the Kharijites, and five Kharijite revolts, usually involving around 70 men, were suppressed. Notable among these was that of the cousins Qarib ibn Murra al-Azdi and Zuhhaff ibn Zahr al-Tayyi. In 672/673 they rebelled in Basra with a 70-strong band. They are reported to have been involved in the random killing () of people in the streets and mosques of Basra before being cornered in a house, where they were eventually killed and their bodies crucified. Afterward, Ziyad is reported to have severely persecuted their followers. Ibn Ziyad jailed any Kharijite whom he suspected of being dangerous and executed several Kharijite sympathizers who had publicly denounced him. Between their successive reigns, Ziyad and his son are said to have killed 13,000 Kharijites. As a result of these repressive measures, some of the Kharijites abandoned military action, adopting political quietism

In the political aspects of Islam, political quietism in Islam is the religiously-motivated withdrawal from political affairs or skepticism that mere mortals can establish a true Islamic government. It is the opposite of political Islam, which ...

and concealing their religious beliefs. Of the quietists, the best known was Abu Bilal Mirdas ibn Udayya al-Tamimi. One of the earliest Kharijites who had seceded at Siffin, he was held in the highest esteem by the Basran quietists. Provoked by the torture and murder of a Kharijite woman by Ibn Ziyad, Abu Bilal abandoned Basra and revolted in 680/681 with 40 men. Shortly after defeating a 2,000-strong Basran force in Ahwaz

Ahvaz ( fa, اهواز, Ahvâz ) is a city in the southwest of Iran and the capital of Khuzestan province. Ahvaz's population is about 1,300,000 and its built-up area with the nearby town of Sheybani is home to 1,136,989 inhabitants. It is hom ...

, he fell to a larger army of 3,000 or 4,000 in Fars in southern Persia. His fate is said to have aroused the quietists and contributed to the increased Kharijite militancy in the subsequent period.

Second Fitna

Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Prov ...

(where Mecca and Medina are located) rebelled against Mu'awiya's son and successor, Yazid. The Mecca-based Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr

Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam ( ar, عبد الله ابن الزبير ابن العوام, ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-ʿAwwām; May 624 CE – October/November 692), was the leader of a caliphate based in Mecca that rivaled the ...

, a son of Zubayr ibn al-Awwam, was the most prominent Hejazi opponent of Yazid. When Yazid sent an army to suppress the rebellion in 683 and Mecca was besieged, Kharijites from Basra reinforced Ibn al-Zubayr. After Yazid's death in November, Ibn al-Zubayr proclaimed himself caliph and publicly condemned Uthman's murder. Both acts prompted the Kharijites to abandon his cause. The majority, including Nafi ibn al-Azraq

Nafi ibn al-Azraq ibn Qays al-Hanafi al-Bakri ( ar, نافع بن الأزرق بن قيس الحنفي البكري, Nāfiʿ ibn al-Azraḳ ibn Qays al-Ḥanafī al-Bakrī; died 685) was the leader of the Kharijite faction of the Azariqa during t ...

and Najda ibn Amir al-Hanafi, went to Basra, while the remainder left for the Yamama, in central Arabia, under the leadership of Abu Talut Salim ibn Matar. In the meantime, Ibn Ziyad was expelled by tribal chiefs in Basra, where inter-tribal strife ensued. Ibn al-Azraq and other militant Kharijites took over the city, killed the deputy left by Ibn Ziyad and freed 140 Kharijites from prison. Soon afterwards, the Basrans recognized Ibn al-Zubayr, who appointed Umar ibn Ubayd Allah ibn Ma'mar Umar ibn Ubayd Allah ibn Ma'mar al-Taymi (died 702 or 703) was a commander of the Zubayrid and Umayyad caliphates in their wars with the Kharijites and the chief of the Banu Taym clan of the Quraysh in the late 7th century.

Early life

Umar was the ...

as the city's governor. Umar drove out Ibn al-Azraq's men from Basra and they escaped to Ahwaz.

Azariqa

From Ahwaz, Ibn al-Azraq raided Basra's suburbs. His followers are calledAzariqa

The Azariqa ( ar, الأزارقة, ''al-azāriqa'') were an extremist branch of Khawarij, who followed the leadership of Nafi ibn al-Azraq al-Hanafi. Adherents of Azraqism participated in an armed struggle against the rulers of the Umayyad Cali ...

after their leader, and are described in the sources as the most fanatic of the Kharijite groups, for they approved the doctrine of : indiscriminate killing of the non-Kharijite Muslims, including their women and children. An army sent against them by the Zubayrid governor of Basra in early 685 defeated the Azariqa, and Ibn al-Azraq was killed. The Azariqa chose Ubayd Allah ibn Mahuz as their new leader, regrouped, forced the Zubayrid army to retreat, and resumed their raids. After more defeats, Ibn al-Zubayr deployed his most able commander, Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra

Abū Saʿīd al-Muhallab ibn Abī Ṣufra al-Azdī ( ar, أَبْو سَعِيْد ٱلْمُهَلَّب ابْن أَبِي صُفْرَة ٱلْأَزْدِي; 702) was an Arab general from the Azd tribe who fought in the service of the Ra ...

, against the Azariqa. Muhallab defeated them at the battle of Sillabra in May 686 and killed Ibn Mahuz. The Azariqa retreated to Fars. In late 686, Muhallab discontinued his campaign as he was sent to rein in the pro-Alid ruler of Kufa, Mukhtar al-Thaqafi

Al-Mukhtar ibn Abi Ubayd al-Thaqafi ( ar, المختار بن أبي عبيد الثقفي, '; – 3 April 687) was a pro-Alid revolutionary based in Kufa, who led a rebellion against the Umayyad Caliphate in 685 and ruled over most of Iraq ...

, and was afterward appointed governor of Mosul

Mosul ( ar, الموصل, al-Mawṣil, ku, مووسڵ, translit=Mûsil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ܡܘܨܠ, Māwṣil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second larg ...

to defend against possible Umayyad attacks from Syria. The Azariqa plundered al-Mada'in and then besieged Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Region, Isfahan Province, Iran. It is lo ...

, but were defeated. They fled and eventually regrouped in Kirman. Reinvigorated by a new leader, Qatari ibn al-Fuja'a

Qaṭari ibn al-Fujaʾa ( ar, قطري بن الفجاءة ; died c. 698–699 CE) was a Kharjite leader and poet. Born in Al Khuwayr, he ruled over the Azariqa faction of the Kharjites for more than ten years after the death of Nafi ibn al-Azr ...

, the Azariqa attacked Basra's environs afterward and Muhallab was redeployed to suppress them. Although the Azariqa were not dislodged from Fars and Kirman, Muhallab prevented their advance into Iraq. Qatari minted his own coins and adopted the caliphal title (commander of the faithful). After the Umayyads reconquered Iraq from the Zubayrids in 691, Umayyad princes took over the command from Muhallab, but were dealt severe defeats by the Azariqa. In 694 the commander Hajjaj ibn Yusuf

Abu Muhammad al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf ibn al-Hakam ibn Abi Aqil al-Thaqafi ( ar, أبو محمد الحجاج بن يوسف بن الحكم بن أبي عقيل الثقفي, Abū Muḥammad al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yūsuf ibn al-Ḥakam ibn Abī ʿAqīl al-T ...

was appointed governor of Iraq and reinstated Muhallab to lead the war against the Azariqa. Muhallab forced their retreat to Kirman, where they split into two groups and were subsequently destroyed in 698–699.

Najdat

During his time in Ahwaz, Najda broke with Ibn al-Azraq over the latter's extremist ideology. Najda, with his followers, moved to the Yamama, the homeland of hisBanu Hanifa

Banu Hanifa ( ar, بنو حنيفة) is an ancient Arab tribe inhabiting the area of al-Yamama in the central region of modern-day Saudi Arabia. The tribe belongs to the great Rabi'ah branch of North Arabian tribes, which also included Abd ...

tribe. He became leader of Abu Talut's Kharijite faction, which became known as the Najdat after him. Najda took control of Bahrayn

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ad ...

, repulsing a 14,000-strong Zubayrid army deployed against him. His lieutenant, Atiyya ibn al-Aswad, captured Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

from the local Julanda rulers, though the latter reasserted their control after a few months. Najda seized Hadramawt

Hadhramaut ( ar, حَضْرَمَوْتُ \ حَضْرَمُوتُ, Ḥaḍramawt / Ḥaḍramūt; Hadramautic: 𐩢𐩳𐩧𐩣𐩩, ''Ḥḍrmt'') is a region in South Arabia, comprising eastern Yemen, parts of western Oman and southern Saud ...

and Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast and ...

in 687 and later captured Ta'if

Taif ( ar, , translit=aṭ-Ṭāʾif, lit=The circulated or encircled, ) is a city and governorate in the Makkan Region of Saudi Arabia. Located at an elevation of in the slopes of the Hijaz Mountains, which themselves are part of the Sarat M ...

, a town close to Ibn al-Zubayr's capital Mecca, leaving the latter cornered in the Hejaz, as Najda controlled most of Arabia. Not long after, his followers became disillusioned with him for his alleged correspondence with the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik, irregular pay to his soldiers, his refusal to punish a soldier who had consumed wine, and his release of a captive granddaughter of caliph Uthman. He was thus deposed for having gone astray and subsequently executed in 691. Atiyya had already broken from Najda and moved to Sistan

Sistān ( fa, سیستان), known in ancient times as Sakastān ( fa, سَكاستان, "the land of the Saka"), is a historical and geographical region in present-day Eastern Iran ( Sistan and Baluchestan Province) and Southern Afghanistan ( ...

in eastern Persia, and was later killed there or in Sind

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

. In Sistan, his followers split into various sects, including the Atawiyya and the Ajarida. In Arabia, Abu Fudayk Abd Allah ibn Thawr took over the leadership of the Najdat and defeated several Zubayrid and later Umayyad attacks. He was eventually killed along with 6,000 followers in 692 by Umayyad forces in Bahrayn. Politically exterminated, the Najdat retreated into obscurity and disappeared around the tenth century.

Moderate Kharijites and their fragmentation

According to the heresiographers' accounts, the original Kharijites split into four principal groups (; the mother sects of all the later Kharijites sects), during the Second Fitna. A moderate group, headed by Abd Allah ibn Saffar (or Asfar) and Abd Allah ibn Ibad, disagreed with the radical Azariqa and Najdat on the question of rebellion and separation from the non-Kharijites. Ibn Saffar and Ibn Ibad then disagreed amongst themselves as to the faith of the non-Kharijites, and thus came the two other sects: the Sufriyya and Ibadiyya. All the other uncategorized Kharijite subgroups are considered offshoots of the Sufriyya. In this scheme, the Kharijites of the Jazira region (north-western Iraq), including the ascetic Salih ibn Mussarih and the tribal leader Shabib ibn Yazid al-Shaybani are associated with the Sufriyya, as well as the revolt of Dahhak ibn Qays al-Shaybani during theThird Fitna

The Third Fitna ( ar, الفتنة الثاﻟﺜـة, al-Fitna al-thālitha), was a series of civil wars and uprisings against the Umayyad Caliphate beginning with the overthrow of Caliph al-Walid II in 744 and ending with the victory of Marwan ...

(744–750). After Ibn Ibad's death, the Ibadiyya are considered to have been led into the late Umayyad period successively by Jabir ibn Zayd

Abu al-Sha'tha Jabir ibn Zayd al-Zahrani al-Azdi () was a Muslim theologian and one of the founding figures of the Ibadis, Donald Hawley, ''Oman'', pg. 199. Jubilee edition. Kensington: Stacey International, 1995. the third major denomination of ...

and Abu Ubayda Muslim ibn Abi Karima. Jabir, a respected scholar and traditionist, had friendly relations with Abd al-Malik and Hajjaj. Following the death of Abd al-Malik, relations between the Ibadiyya leaders and Hajjaj deteriorated, as the former became inclined towards activism (). Hajjaj consequently exiled some of them to Oman and imprisoned others. Abu Ubayda, who was released after the death of Hajjaj in 714, became the next leader of the Ibadiyya. After unsuccessfully attempting to win over the Umayyad caliphs to the Ibadi doctrine, he sent missionaries to propagate the doctrine in different parts of the empire. Almost simultaneously, the Sufriyya also spread into North Africa and southern Arabia through missionary activity. Through absorption into the Ibadiyya, the Sufriyya eventually became extinct. Ibadi sources too are more or less in line with this scheme, where the Ibadiyya appear as the true successors of the original Medinese community and the early, pre-Second-Fitna Kharijites, though Ibn Ibad does not feature prominently and Jabir is asserted as the leader of the movement following Abu Bilal Mirdas.

Modern historians consider Ibn Saffar to be a legendary figure, and assert that the Sufriyya and Ibadiyya sects did not exist during the seventh century. The heresiographers, whose aim was to categorize the divergent beliefs of the Kharijites, most likely invented the Sufriyya to accommodate those groups who did not fit neatly anywhere else. As such, there was only one moderate Kharijite current, which might have been called "Sufri". According to the historian Keith Lewinstein, the term probably originated with the pious early Kharijites because of their pale-yellow appearance () caused by excessive worship. The moderates condemned the militancy of the Azariqa and Najdat, but otherwise lacked a set of concrete doctrines. Jabir and Abu Ubayda may have been prominent figures in the moderate movement. The moderates further split into the true Sufriyya and Ibadiyya only during the eighth century, with the main difference being tribal affiliations rather than doctrinal differences.

During the Second Fitna, the moderates remained inactive. However, in the mid-690s they also started militant activities in response to persecution by Hajjaj. The first of their revolts was led in 695 by Ibn Musarrih, and ended in defeat and Ibn Musarrih's death. Afterward, this Kharijite group became a major threat to Kufa and its suburbs under Shabib. With a small army of a few hundred warriors, Shabib defeated several thousands-strong Umayyad armies in 695–696, looted Kufa's treasury and occupied al-Mada'in. From his base in al-Mada'in, Shabib moved to capture Kufa. Hajjaj had already requested Syrian troops from Abd al-Malik, who sent a 4,000-strong army which defeated Shabib outside Kufa. Shabib drowned in a river during his flight, his band was destroyed, but the Kharijites continued to maintain a presence in the Jazira.

Sufriyya

Hisham

Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik ( ar, هشام بن عبد الملك, Hishām ibn ʿAbd al-Malik; 691 – 6 February 743) was the tenth Umayyad caliph, ruling from 724 until his death in 743.

Early life

Hisham was born in Damascus, the administrat ...

and Abd Allah, son of Umar II

Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz ( ar, عمر بن عبد العزيز, ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz; 2 November 680 – ), commonly known as Umar II (), was the eighth Umayyad caliph. He made various significant contributions and reforms to the society, an ...

), recognized him as caliph and joined his ranks. Dahhak captured Mosul, but was killed by the forces of the Caliph Marwan II

Marwan ibn Muhammad ibn Marwan ibn al-Hakam ( ar, مروان بن محمد بن مروان بن الحكم, Marwān ibn Muḥammad ibn Marwān ibn al-Ḥakam; – 6 August 750), commonly known as Marwan II, was the fourteenth and last caliph of ...

in 746. His successor, Shayban ibn Abd al-Aziz al-Yashkuri, was driven out from Mosul by Marwan II and fled to Fars to join the Shi'a leader Abd Allah ibn Mu'awiya

( ar, عبد الله بن معاویه الهاشمي; died 747) was an Alid leader who led a rebellion against the Umayyad Caliphate at Kufa and later Persia during the Third Fitna.

Early life and rise to the imamate

Abd Allah ibn Mu'awiya was ...

, who ruled in opposition to the Umayyads. Attacked there by the Umayyads, they dispersed and Shayban fled to Oman, where he was killed by the local leaders around 751. Under the Abbasids

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

, who had toppled the Umayyads in 750, Sufri revolts in the eastern parts of the empire continued for almost two centuries, though at a small scale and were easily put down. However, in revolts led by Abd al-Hamid al-Bajali in 866–877 and by Harun ibn Abd Allah al-Bajali in 880–896, the Kharijites gained control of northern Mesopotamia from the Abbasids and collected taxes.

By the mid-8th century, the quietist Kharijites appeared in North Africa. They were mostly of Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–19 ...

origin and were recruited through missionary activity. With the Ibadi–Sufri distinction emergent in this period, the groups with no Ibadi affiliation were associated with the Sufriyya. Around 740, the Sufriyya under the leadership of Maysara al-Matghari Maysar al-Matghari (Berber: ''Maysar Amteghri'' or ''Maysar Amdeghri'', ; sometimes rendered ''Maisar'' or ''Meicer''; in older Arab sources, bitterly called: ''al-Ḥaqir'' ('the ignoble'); died in September/October 740) was a Berber rebel leader a ...

had revolted in Tangiers

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

and captured the city from the Umayyads. They marched onto the provincial capital Kairouan

Kairouan (, ), also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan ( ar, ٱلْقَيْرَوَان, al-Qayrawān , aeb, script=Latn, Qeirwān ), is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by t ...

, but were unable to capture it. Nevertheless, Sufri disturbances in North Africa continued throughout the Umayyad period. Around 750, the Sufri Midrarids established a dynasty in Sijilmasa

Sijilmasa ( ar, سجلماسة; ; also transliterated Sijilmassa, Sidjilmasa, Sidjilmassa and Sigilmassa) was a medieval Moroccan city and trade entrepôt at the northern edge of the Sahara in Morocco. The ruins of the town extend for five miles a ...

, in modern Morocco. The dynasty survived until the Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dyna ...

capture of the city in 909. Nonetheless, the Midrarids continued governing the city under intermittent Fatimid suzerainty until 976. The North African Sufriyya later disappeared, and their remnants were absorbed into the Ibadiyya around the tenth or 11th century.

Ibadiyya

In the early eighth century, a proto-Ibadi movement emerged from the Basran moderates. Missionaries were sent to propagate the doctrine in different parts of the empire including Oman, Yemen, Hadramawt,Khurasan

Greater Khorāsān,Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236 or Khorāsān ( pal, Xwarāsān; fa, خراسان ), is a historical eastern region in the Iranian Plat ...

, and North Africa. During the final years of the Umayyad Caliphate, the Ibadi propaganda movement caused several revolts in the periphery of the empire, though the leaders in Basra adopted the policy of (also called ); concealing beliefs so as to avoid persecution.

imams

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, serve ...

continued to wield considerable power. Around a century later, Ibadi leader al-Khalil ibn Shathan al-Kharusi () reasserted control over the central Oman, whereas his successor Rashid ibn Sa'id al-Yahmadi () drove the then Abbasid patrons Buyids

The Buyid dynasty ( fa, آل بویه, Āl-e Būya), also spelled Buwayhid ( ar, البويهية, Al-Buwayhiyyah), was a Shia Iranian dynasty of Daylamite origin, which mainly ruled over Iraq and central and southern Iran from 934 to 1062. Coup ...

out of the coastal region, thereby restoring the Ibadi control of Oman. Internal splits led to fall of the third Ibadi imamate in the late 12th century. Ibadi imamates were reestablished in subsequent centuries. Ibadis form the majority of the Omani population to date.

Ibadi missionary activity met with considerable success in North Africa. In 757, Ibadis seized Tripoli and captured Kairouan the next year. Driven out by an Abbasid army in 761, Ibadi leaders founded a state, which became known as the Rustamid dynasty

The Rustamid dynasty () (or ''Rustumids'', ''Rostemids'') was a ruling house of Ibāḍī imāms of Persian descent centered in Algeria. The dynasty governed as a Muslim theocracy for a century and a half from its capital Tiaret (present day ...

, in Tahart Tahart (also written Tahat) is a village in the commune of Abalessa, in Tamanrasset Province, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capi ...

. It was overthrown in 909 by the Fatimids. Ibadi communities continue to exist today in the Nafusa Mountains

The Nafusa Mountains (Berber: ''Adrar n Infusen'' (Nafusa Mountain), ar, جبل نفوسة (Western mountain)) are a mountain range in the western Tripolitania region of northwestern Libya. It also includes their regions around the escarpment fo ...

in northwestern Libya, Djerba

Djerba (; ar, جربة, Jirba, ; it, Meninge, Girba), also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is a Tunisian island and the largest island of North Africa at , in the Gulf of Gabès, off the coast of Tunisia. It had a population of 139,544 ...

island in Tunisia and the M'zab

The M'zab or Mzab ( Mozabite: ''Aghlan'', ar, مزاب) is a natural region of the northern Sahara Desert in Ghardaïa Province, Algeria. It is located south of Algiers and there are approximately 360,000 inhabitants (2005 estimate).

Geolog ...

valley in Algeria. In East Africa they are found in Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

. Ibadi missionary activity also reached Persia, India, Egypt, Sudan, Spain and Sicily, although Ibadi communities in these regions disappeared over time. The total numbers of the Ibadis in Oman and Africa are estimated to be around 2.5 million and 200,000 respectively.

Beliefs and practices

The Kharijites did not have a uniform and coherent set of doctrines. Different sects and individuals held different views. Based on these divergences, heresiographers have listed more than a dozen minor Kharijite sects, in addition to the four main sects discussed above.Governance

In addition to their insistence on rule according to the Qur'an, the view common to all Kharijite groups was that any Muslim was qualified to become caliph, regardless of origin, if he had the credentials of belief andpiety

Piety is a virtue which may include religious devotion or spirituality. A common element in most conceptions of piety is a duty of respect. In a religious context piety may be expressed through pious activities or devotions, which may vary among ...

. They rejected Quraysh

The Quraysh ( ar, قُرَيْشٌ) were a grouping of Arab clans that historically inhabited and controlled the city of Mecca and its Kaaba. The Islamic prophet Muhammad was born into the Hashim clan of the tribe. Despite this, many of the Qu ...

ite descent or close kinship with Muhammad as a prerequisite for the office, a view espoused by most Muslims at the time. This differs from the position of both Sunnis, who accepted the leadership of those in power provided that they were Qurayshite, and Shi'a, who asserted that the leadership belonged to Ali and his descendants. The Kharijites held that the first four caliphs had not been elected for their Qurayshite descent or kinship with Muhammad, but because they were among the most eminent and qualified Muslims for the position, and hence were all legitimate caliphs. In particular, they had a high regard for Abu Bakr

Abu Bakr Abdallah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa (; – 23 August 634) was the senior companion and was, through his daughter Aisha, a father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, as well as the first caliph of Islam. He is known with the honor ...

and Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate ...

as, according to them, they governed justly. Uthman, on the other hand, had deviated from the path of justice and truth in the latter half of his caliphate and was thus liable to be killed or deposed, whereas Ali committed a grave sin when he agreed to the arbitration with Mu'awiya. In contrast to the Umayyad idea that their rule was ordained by God, the Kharijite idea of leadership lacked any divine sanctioning; only correct attitude and piety granted the leader authority over the community. If the leader committed a sin and deviated from the right path or failed to manage Muslims' affairs through justice and consultation, he was obliged to acknowledge his mistake and repent, or else he forfeited his right to rule and was subject to deposition. In the view of the Azariqa and the Najdat, Muslims had the duty to revolt against such a ruler.

Almost all Kharijite groups considered the position of a leader (imam) to be necessary. Many Kharijite leaders adopted the title of , which was usually reserved for caliphs. An exception are the Najdat, who, as a means of survival, abandoned the requirement of war against non-Kharijites after their defeat in 692, and rejected that the imamate was an obligatory institution. The historian Patricia Crone has described the Najdat's philosophy as an early form of anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

.

Other doctrines

The Kharijites also asserted that faith without accompanying deeds is useless, and that anyone who commits a major sin is an unbeliever () and must repent to restore the true faith. However, the Kharijite notion of unbelief () differed from the mainstream Muslim definition, which understood a as someone who was a non-Muslim. To the Kharijites, implied a defective Muslim, or pseudo-Muslim, who rejected true Islam. The Azariqa held a more extreme position that such unbelievers were in factpolytheists

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

and apostates

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that ...

who could not reenter Islam and could be killed, along with their women and children. Intermarriage between the Kharijites and such unbelievers was forbidden in the Azariqa doctrine. The Najdat allowed marriages with non-Kharijites. Of the moderates, the Sufriyya and Bayhasiyya considered all non-Kharijite Muslims as unbelievers, but also abstained from taking up arms against them, unless necessary, and allowed intermarriage with them. The Ibadiyya, on the other hand, did not declare the non-Kharijites as polytheists or unbelievers in the general sense, rather as hypocrites

Hypocrisy is the practice of engaging in the same behavior or activity for which one criticizes another or the practice of claiming to have moral standards or beliefs to which one's own behavior does not conform. In moral psychology, it is the ...

(), or ungrateful for God's blessings (). They also permitted marriages outside their own sect.

The Azariqa and Najdat held that since the Umayyad rulers, and all non-Kharijites in general, were unbelievers, it was unlawful to continue living under their rule (), for that was in itself an act of unbelief. It was thus obligatory to emigrate, in emulation of Muhammad's Hijra

Hijra, Hijrah, Hegira, Hejira, Hijrat or Hijri may refer to:

Islam

* Hijrah (often written as ''Hejira'' in older texts), the migration of Muhammad from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE

* Migration to Abyssinia or First Hegira, of Muhammad's followers ...

to Medina, and establish a legitimate dominion of their own (). The Azariqa prohibited the practice of dissimulation of their faith () and branded non-activist Kharijites (i.e. those who did not emigrate to their camp) as unbelievers. The Najdat allowed and quietism, but labeled their practitioners as hypocrites. The Islamicist Montgomery Watt

William Montgomery Watt (14 March 1909 – 24 October 2006) was a Scottish Orientalist, historian, academic and Anglican priest. From 1964 to 1979, he was Professor of Arabic and Islamic studies at the University of Edinburgh.

Watt was one ...

attributes this moderation of the Najdat stance to practical necessities which they encountered while governing Arabia, as the administration of a large area required flexibility and allowance for human imperfection. The Sufriyya and Ibadiyya held that while the establishment of a legitimate dominion was desirable, it was legal to employ and continue living among the non-Kharijites if rebellion was not possible.

The Kharijites espoused that all Muslims were equals, regardless of ethnicity and advocated for equal status of the (sing. ; non-Arab, free Muslims of conquered lands, especially Iraq and Persia) with the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

. The Najdat chose a , a fruit seller named Thabit, as their leader after Najda's execution. This choice, however, conflicted with their feelings of ethnic solidarity and they soon asked him to step down and choose an Arab leader for them; he chose Abu Fudayk. The leader of the Azariqa, Ibn al-Azraq, is said to have been the son of a of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

origin. The imams of the North African Kharijites from 740 onwards were all non-Arabs. The Kharijites also advocated for the equality of women with men. On the basis of women fighting alongside Muhammad, the Kharijites viewed jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with G ...

as incumbent upon women. The warrior and poet Layla bint Tarif is a famous example. Shabib's wife Ghazala

Ghazāla (; died 696 AD near Kufa) was a leader of the Kharijite movement.

Biography

Ghazāla, born in Mosul, was the wife of Shabib ibn Yazid al-Shaybani. Shabib rebelled against Umayyad rule, and Ghazala was actively at his side. She commanded ...

participated in his battles against the troops of Hajjaj. The Kharijites had a scrupulous attitude towards non-Muslims, respecting their dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

(protected) status more seriously than others.

Some of the Kharijites rejected the punishment of adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

with stoning

Stoning, or lapidation, is a method of capital punishment where a group throws stones at a person until the subject dies from blunt trauma. It has been attested as a form of punishment for grave misdeeds since ancient times.

The Torah and Ta ...

, which is prescribed in other Islamic legal schools. Although the Qur'an does not prescribe this penalty, Muslims of other sects hold that such a verse existed in the Qur'an, which was then abrogated. A hadith is ascribed to Umar, asserting the existence of this verse in the Qur'an. These Kharijites rejected the authenticity of such a verse. The heresiographer al-Ash'ari attributed this position to the Azariqa, who held a strict scripturalist position in legal matters (i.e. following only the Qur'an and rejecting commonly held views if they had no Qur'anic basis), and thus also refused to enforce legal punishment on slanderers when the slander was targeted at a male. The Azariqa instituted the practice of testing the faith of new recruits (), which is said to have involved giving them a prisoner to kill. It was either an occasional practice, as held by Watt, or a later distortion by the heresiographers, as held by Lewinstein. One of the Kharijite groups also refused to recognize the sura

A ''surah'' (; ar, سورة, sūrah, , ), is the equivalent of "chapter" in the Qur'an. There are 114 ''surahs'' in the Quran, each divided into '' ayats'' (verses). The chapters or ''surahs'' are of unequal length; the shortest surah ('' Al-K ...

(Qur'anic chapter) of as being an original part of the Qur'an, for they considered its content to be worldly and frivolous.

Poetry

Many Kharijites were well-versed in traditional Arabic eloquence and poetry, which the orientalistGiorgio Levi Della Vida

Giorgio Levi Della Vida (22 August 1886 in Venice – 25 November 1967 in Rome) was an Italian Jewish linguist whose expertise lay in Hebrew, Arabic, and other Semitic languages, as well as on the history and culture of the Near East.

Biography

Bo ...

attributes to the majority of their early leaders being from Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arabs, Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert ...

stock. The sermons and poems of many Kharijite leaders were compiled into collections ( diwans). Kharijite poetry is mainly concerned with religious beliefs, with piety and activism, martyrdom

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

, selling life to God (), and afterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving ess ...

being some of the most prominent themes, though the themes of heroism and courage are also evident. Referring to his rebellion, Abu Bilal Mirdas said: "Fear of God and the dread of the fire made me go out, and selling my soul for which has no price aradise.

Some poems encouraged militant activism. Imran ibn Hittan

Imran, also transliterated as Emran ( ar, عمران ''ʿImrān'') is an Arabic form of the Hebrew male name ʿAmram in the Middle East and other Muslim countries. The name Imran is found in the Quranic chapter called House of ʿImrān (''āl ʿI ...

, whom the Arabist Michael Cooperson Michael Cooperson is an American scholar and translator of Arabic literature. He is professor of Arabic at UCLA. He has written two books: ''Classical Arabic Biography: The Heirs of the Prophets in the Age of al-Ma'mun'' and ''Al-Mamun (Makers Of Th ...

calls the greatest Kharijite poet, sang after Abu Bilal's death: "Abū Bilāl has increased my disdain for this life; and strengthened my love for the khurūj ebellion. The poet Abu'l-Wazi al-Rasibi addressed Ibn al-Azraq, before the latter became activist, with the lines:

The government was often labelled as tyrannical and obedience to it was criticized. The Kharijite poet Isa ibn Fatik al-Khatti thus sang:

Many poems were written to eulogize fallen Kharijite activists, and thus represent the romanticized version of actual historical events. The Muhakkima are thus valorized and remembered at many places. The poet Aziz ibn al-Akhnas al-Ta'i eulogized them in the following lines:

Similarly, Ali's assassin Ibn Muljam was exalted by the poet Ibn Abi Mayyas al-Muradi in the following: