Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

) are the various

macroeconomic

Macroeconomics (from the Greek prefix ''makro-'' meaning "large" + ''economics'') is a branch of economics dealing with performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole.

For example, using interest rates, taxes, and ...

theories and

models

A model is an informative representation of an object, person or system. The term originally denoted the plans of a building in late 16th-century English, and derived via French and Italian ultimately from Latin ''modulus'', a measure.

Models c ...

of how

aggregate demand (total spending in the

economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

) strongly influences

economic output

Output in economics is the "quantity of goods or services produced in a given time period, by a firm, industry, or country", whether consumed or used for further production.

The concept of national output is essential in the field of macroecono ...

and

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

. In the Keynesian view, aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the

productive capacity of the economy. Instead, it is influenced by a host of factors – sometimes behaving erratically – affecting production, employment, and

inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

.

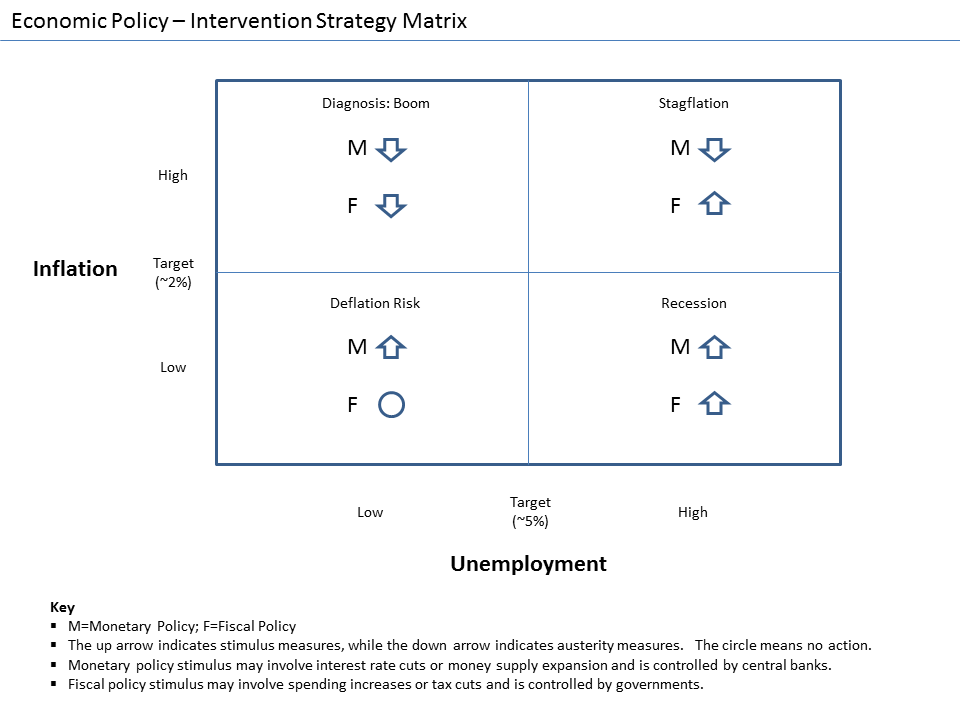

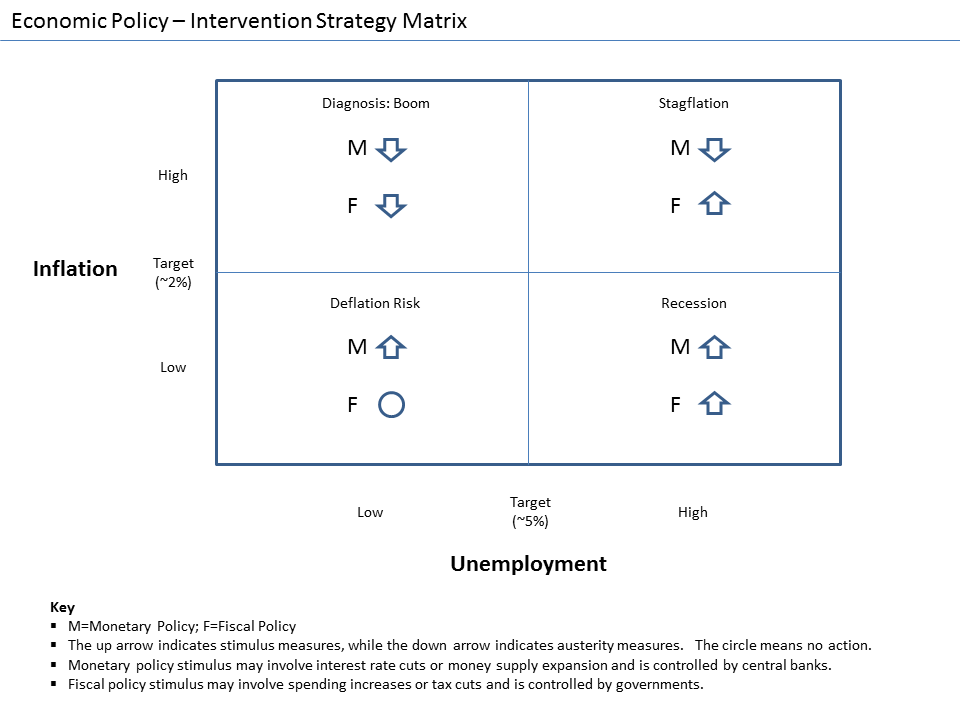

Keynesian economists generally argue that aggregate demand is volatile and unstable and that, consequently, a

market economy often experiences inefficient macroeconomic outcomes – a

recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by various ...

, when demand is low, or inflation, when demand is high. Further, they argue that these economic fluctuations can be mitigated by economic policy responses coordinated between government and

central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central ba ...

. In particular,

fiscal policy

In economics and political science, fiscal policy is the use of government revenue collection (taxes or tax cuts) and expenditure to influence a country's economy. The use of government revenue expenditures to influence macroeconomic variab ...

actions (taken by the government) and

monetary policy

Monetary policy is the policy adopted by the monetary authority of a nation to control either the interest rate payable for very short-term borrowing (borrowing by banks from each other to meet their short-term needs) or the money supply, often a ...

actions (taken by the central bank), can help stabilize economic output, inflation, and unemployment over the

business cycle

Business cycles are intervals of Economic expansion, expansion followed by recession in economic activity. These changes have implications for the welfare of the broad population as well as for private institutions. Typically business cycles are ...

. Keynesian economists generally advocate a regulated market economy – predominantly private sector, but with an active role for government intervention during recessions and

depressions.

Keynesian economics developed during and after the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

from the ideas presented by Keynes in his 1936 book, ''

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

''The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money'' is a book by English economist John Maynard Keynes published in February 1936. It caused a profound shift in economic thought, giving macroeconomics a central place in economic theory and ...

''. Keynes' approach was a stark contrast to the

aggregate supply

In economics, aggregate supply (AS) or domestic final supply (DFS) is the total supply of goods and services that firms in a national economy plan on selling during a specific time period. It is the total amount of goods and services that firms ...

-focused

classical economics that preceded his book. Interpreting Keynes's work is a contentious topic, and several

schools of economic thought

In the history of economic thought, a school of economic thought is a group of economics, economic thinkers who share or shared a common perspective on the way economy, economies work. While economists do not always fit into particular schools, pa ...

claim his legacy.

Keynesian economics, as part of the

neoclassical synthesis, served as the standard macroeconomic model in the

developed nations

A developed country (or industrialized country, high-income country, more economically developed country (MEDC), advanced country) is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy and advanced technological infrastruct ...

during the later part of the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

,

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and the

post-war economic expansion (1945–1973). It was developed in part to attempt to explain the Great Depression and to help economists understand future crises. It lost some influence following the

oil shock and resulting

stagflation of the 1970s.

Keynesian economics was later redeveloped as

New Keynesian economics

New Keynesian economics is a school of macroeconomics that strives to provide microeconomic foundations for Keynesian economics. It developed partly as a response to criticisms of Keynesian macroeconomics by adherents of new classical macroec ...

, becoming part of the contemporary

new neoclassical synthesis

The new neoclassical synthesis (NNS), which is now generally referred to as New Keynesian economics, and occasionally as the New Consensus, is the fusion of the major, modern macroeconomic schools of thought – new classical macroeconomics/ real ...

, that forms current-day

mainstream macroeconomics. The advent of the

financial crisis of 2007–2008

Finance is the study and discipline of money, currency and capital assets. It is related to, but not synonymous with economics, the study of production, distribution, and consumption of money, assets, goods and services (the discipline of fi ...

sparked

renewed interest in Keynesian policies by governments around the world.

Historical context

Pre-Keynesian macroeconomics

Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics (from the Greek prefix ''makro-'' meaning "large" + ''economics'') is a branch of economics dealing with performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole.

For example, using interest rates, taxes, and ...

is the study of the factors applying to an economy as a whole. Important macroeconomic variables include the overall price level, the interest rate, the level of employment, and income (or equivalently output) measured in

real terms

In economics, nominal value is measured in terms of money, whereas real value is measured against goods or services. A real value is one which has been adjusted for inflation, enabling comparison of quantities as if the prices of goods had not c ...

.

The classical tradition of

partial equilibrium theory had been to split the economy into separate markets, each of whose equilibrium conditions could be stated as a single equation determining a single variable. The theoretical apparatus of

supply

Supply may refer to:

*The amount of a resource that is available

**Supply (economics), the amount of a product which is available to customers

**Materiel, the goods and equipment for a military unit to fulfill its mission

*Supply, as in confidenc ...

and

demand curve

In economics, a demand curve is a graph depicting the relationship between the price of a certain commodity (the ''y''-axis) and the quantity of that commodity that is demanded at that price (the ''x''-axis). Demand curves can be used either for ...

s developed by

Fleeming Jenkin

Henry Charles Fleeming Jenkin FRS FRSE LLD (; 25 March 1833 – 12 June 1885) was Regius Professor of Engineering at the University of Edinburgh, remarkable for his versatility. Known to the world as the inventor of the cable car or telphera ...

and

Alfred Marshall provided a unified mathematical basis for this approach, which the

Lausanne School The Lausanne School of economics, sometimes referred to as the Mathematical School, refers to the neoclassical economics school of thought surrounding Léon Walras and Vilfredo Pareto. It is named after the University of Lausanne, at which both Walr ...

generalized to general equilibrium theory.

For macroeconomics, relevant partial theories included the

Quantity theory of money

In monetary economics, the quantity theory of money (often abbreviated QTM) is one of the directions of Western economic thought that emerged in the 16th-17th centuries. The QTM states that the general price level of goods and services is directly ...

determining the price level and the

classical theory of the interest rate. In regards to employment, the condition referred to by Keynes as the "first postulate of classical economics" stated that the wage is equal to the marginal product, which is a direct application of the

marginalist

Marginalism is a theory of economics that attempts to explain the discrepancy in the value of goods and services by reference to their secondary, or marginal, utility. It states that the reason why the price of diamonds is higher than that of wa ...

principles developed during the nineteenth century (see

''The General Theory''). Keynes sought to supplant all three aspects of the classical theory.

Precursors of Keynesianism

Although Keynes's work was crystallized and given impetus by the advent of the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, it was part of a long-running debate within economics over the existence and nature of

general glut

In macroeconomics, a general glut is an excess of supply in relation to demand, specifically, when there is more production in all fields of production in comparison with what resources are available to consume (purchase) said production.

This exh ...

s. A number of the policies Keynes advocated to address the Great Depression (notably government deficit spending at times of low private investment or consumption), and many of the theoretical ideas he proposed (effective demand, the multiplier, the

paradox of thrift

The paradox of thrift (or paradox of saving) is a paradox of economics. The paradox states that an increase in autonomous saving leads to a decrease in aggregate demand and thus a decrease in gross output which will in turn lower ''total'' saving ...

), had been advanced by authors in the 19th and early 20th centuries. (E.g.

J. M. Robertson raised the paradox of thrift

in 1892.

) Keynes's unique contribution was to provide a ''general theory'' of these, which proved acceptable to the economic establishment.

An intellectual precursor of Keynesian economics was

underconsumption Underconsumption is a theory in economics that recessions and stagnation arise from an inadequate consumer demand, relative to the amount produced. In other words, there is a problem of overproduction and overinvestment during a demand crisis. The ...

theories associated with

John Law

John Law may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* John Law (artist) (born 1958), American artist

* John Law (comics), comic-book character created by Will Eisner

* John Law (film director), Hong Kong film director

* John Law (musician) (born 1961) ...

,

Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English cleric, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book '' An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

, the

Birmingham School of

Thomas Attwood, and the American economists

William Trufant Foster

William Trufant Foster (January 18, 1879 – October 8, 1950), was an American educator and economist, whose theories were especially influential in the 1920s. He was the first president of Reed College.

Early life and education

Foster was born ...

and

Waddill Catchings

Waddill Catchings (September 6, 1879 – December 31, 1967) was an American economist who collaborated with his Harvard classmate William Trufant Foster in a series of economics books that were highly influential in the United States in the 19 ...

, who were influential in the 1920s and 1930s. Underconsumptionists were, like Keynes after them, concerned with failure of

aggregate demand to attain potential output, calling this "underconsumption" (focusing on the demand side), rather than "

overproduction

In economics, overproduction, oversupply, excess of supply or glut refers to excess of supply over demand of products being offered to the market. This leads to lower prices and/or unsold goods along with the possibility of unemployment.

The d ...

" (which would focus on the supply side), and advocating

economic interventionism. Keynes specifically discussed underconsumption (which he wrote "under-consumption") in the ''General Theory,'' i

Chapter 22, Section IVan

Numerous concepts were developed earlier and independently of Keynes by the

Stockholm school during the 1930s; these accomplishments were described in a 1937 article, published in response to the 1936 ''General Theory,'' sharing the Swedish discoveries.

Keynes's early writings

In 1923 Keynes published his first contribution to economic theory, ''

A Tract on Monetary Reform

''A Tract on Monetary Reform'' is a book by John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics ...

'', whose point of view is classical but incorporates ideas that later played a part in the ''General Theory''. In particular, looking at the hyperinflation in European economies, he drew attention to the

opportunity cost of holding money (identified with inflation rather than interest) and its influence on the

velocity of circulation.

In 1930 he published ''

A Treatise on Money

''A Treatise on Money'' is a two-volume book by English economist John Maynard Keynes published in 1930.

Summary of the Work

In the ''Treatise'' Keynes drew a distinction between savings and investment, arguing that where saving exceeded invest ...

'', intended as a comprehensive treatment of its subject "which would confirm his stature as a serious academic scholar, rather than just as the author of stinging polemics", and marks a large step in the direction of his later views. In it, he attributes unemployment to wage stickiness and treats saving and investment as governed by independent decisions: the former varying positively with the interest rate, the latter negatively. The velocity of circulation is expressed as a function of the rate of interest. He interpreted his treatment of liquidity as implying a purely monetary theory of interest.

Keynes's younger colleagues of the

Cambridge Circus and

Ralph Hawtrey

Sir Ralph George Hawtrey (22 November 1879, Slough – 21 March 1975, London) was a British economist, and a close friend of John Maynard Keynes. He was a member of the Cambridge Apostles, the University of Cambridge intellectual secret society.

...

believed that his arguments implicitly assumed

full employment, and this influenced the direction of his subsequent work. During 1933, he wrote essays on various economic topics "all of which are cast in terms of movement of output as a whole".

Development of ''The General Theory''

At the time that Keynes's wrote the

General Theory, it had been a tenet of mainstream economic thought that the economy would automatically revert to a state of general equilibrium: it had been assumed that, because the needs of consumers are always greater than the capacity of the producers to satisfy those needs, everything that is produced would eventually be consumed once the appropriate price was found for it. This perception is reflected in

Say's law

In classical economics, Say's law, or the law of markets, is the claim that the production of a product creates demand for another product by providing something of value which can be exchanged for that other product. So, production is the source ...

and in the writing of

David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist. He was one of the most influential of the classical economists along with Thomas Malthus, Adam Smith and James Mill. Ricardo was also a politician, and a ...

, which states that individuals produce so that they can either consume what they have manufactured or sell their output so that they can buy someone else's output. This argument rests upon the assumption that if a surplus of goods or services exists, they would naturally drop in price to the point where they would be consumed.

Given the backdrop of high and persistent unemployment during the Great Depression, Keynes argued that there was no guarantee that the goods that individuals produce would be met with adequate effective demand, and periods of high unemployment could be expected, especially when the economy was contracting in size. He saw the economy as unable to maintain itself at full employment automatically, and believed that it was necessary for the government to step in and put purchasing power into the hands of the working population through government spending. Thus, according to Keynesian theory, some individually rational

microeconomic-level actions such as not investing savings in the goods and services produced by the economy, if taken collectively by a large proportion of individuals and firms, can lead to outcomes wherein the economy operates below its potential output and growth rate.

Prior to Keynes, a situation in which

aggregate demand for

goods

In economics, goods are items that satisfy human wants

and provide utility, for example, to a consumer making a purchase of a satisfying product. A common distinction is made between goods which are transferable, and services, which are not t ...

and services did not meet supply was referred to by

classical economists

Classical economics, classical political economy, or Smithian economics is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th century. Its main thinkers are held to be Adam Smith ...

as a ''

general glut

In macroeconomics, a general glut is an excess of supply in relation to demand, specifically, when there is more production in all fields of production in comparison with what resources are available to consume (purchase) said production.

This exh ...

'', although there was disagreement among them as to whether a general glut was possible. Keynes argued that when a glut occurred, it was the over-reaction of producers and the laying off of workers that led to a fall in demand and perpetuated the problem. Keynesians therefore advocate an active stabilization policy to reduce the amplitude of the business cycle, which they rank among the most serious of economic problems. According to the theory, government spending can be used to increase aggregate demand, thus increasing economic activity, reducing unemployment and

deflation

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0% (a negative inflation rate). Inflation reduces the value of currency over time, but sudden deflatio ...

.

Origins of the multiplier

The

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

fought the 1929 General Election on a promise to "reduce levels of unemployment to normal within one year by utilising the stagnant labour force in vast schemes of national development".

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

launched his campaign in March with a policy document, ''We can cure unemployment,'' which tentatively claimed that, "Public works would lead to a second round of spending as the workers spent their wages." Two months later Keynes, then nearing completion of his ''Treatise on money'', and

Hubert Henderson

Sir Hubert Douglas Henderson (20 October 1890 – 22 February 1952), was a British economist and Liberal Party politician.

Background

Henderson was born the son of John Henderson of Glasgow. He was educated at Aberdeen Grammar School, Rugby School ...

collaborated on a political pamphlet seeking to "provide academically respectable economic arguments" for Lloyd George's policies. It was titled ''Can Lloyd George do it?'' and endorsed the claim that "greater trade activity would make for greater trade activity ... with a cumulative effect". This became the mechanism of the "ratio" published by

Richard Kahn in his 1931 paper "The relation of home investment to unemployment", described by

Alvin Hansen

Alvin Harvey Hansen (August 23, 1887 – June 6, 1975) was an American economist who taught at the University of Minnesota and was later a chair professor of economics at Harvard University. Often referred to as "the American Keynes", he was a w ...

as "one of the great landmarks of economic analysis". The "ratio" was soon rechristened the "multiplier" at Keynes's suggestion.

The

multiplier of Kahn's paper is based on a respending mechanism familiar nowadays from textbooks. Samuelson puts it as follows:

Let’s suppose that I hire unemployed resources to build a $1000 woodshed. My carpenters and lumber producers will get an extra $1000 of income... If they all have a marginal propensity to consume of 2/3, they will now spend $666.67 on new consumption goods. The producers of these goods will now have extra incomes... they in turn will spend $444.44 ... Thus an endless chain of ''secondary consumption respending'' is set in motion by my ''primary'' investment of $1000.

Samuelson's treatment closely follows

Joan Robinson

Joan Violet Robinson (''née'' Maurice; 31 October 1903 – 5 August 1983) was a British economist well known for her wide-ranging contributions to economic theory. She was a central figure in what became known as post-Keynesian economics.

B ...

's account of 1937 and is the main channel by which the multiplier has influenced Keynesian theory. It differs significantly from Kahn's paper and even more from Keynes's book.

The designation of the initial spending as "investment" and the employment-creating respending as "consumption" echoes Kahn faithfully, though he gives no reason why initial consumption or subsequent investment respending shouldn't have exactly the same effects.

Henry Hazlitt

Henry Stuart Hazlitt (; November 28, 1894 – July 9, 1993) was an American journalist who wrote about business and economics for such publications as ''The Wall Street Journal'', ''The Nation'', ''The American Mercury'', ''Newsweek'', and '' ...

, who considered Keynes as much a culprit as Kahn and Samuelson, wrote that ...

... in connection with the multiplier (and indeed most of the time) what Keynes is referring to as "investment" really means ''any addition to spending for any purpose''... The word "investment" is being used in a Pickwickian, or Keynesian, sense.

Kahn envisaged money as being passed from hand to hand, creating employment at each step, until it came to rest in a ''cul-de-sac'' (Hansen's term was "leakage"); the only ''culs-de-sac'' he acknowledged were imports and hoarding, although he also said that a rise in prices might dilute the multiplier effect. Jens Warming recognised that personal saving had to be considered, treating it as a "leakage" (p. 214) while recognising on p. 217 that it might in fact be invested.

The textbook multiplier gives the impression that making society richer is the easiest thing in the world: the government just needs to spend more. In Kahn's paper, it is harder. For him, the initial expenditure must not be a diversion of funds from other uses, but an increase in the total expenditure: something impossible – if understood in real terms – under the classical theory that the level of expenditure is limited by the economy's income/output. On page 174, Kahn rejects the claim that the effect of public works is at the expense of expenditure elsewhere, admitting that this might arise if the revenue is raised by taxation, but says that other available means have no such consequences. As an example, he suggests that the money may be raised by borrowing from banks, since ...

... it is always within the power of the banking system to advance to the Government the cost of the roads without in any way affecting the flow of investment along the normal channels.

This assumes that banks are free to create resources to answer any demand. But Kahn adds that ...

... no such hypothesis is really necessary. For it will be demonstrated later on that, ''pari passu'' with the building of roads, funds are released from various sources at precisely the rate that is required to pay the cost of the roads.

The demonstration relies on "Mr Meade's relation" (due to

James Meade

James Edward Meade, (23 June 1907 – 22 December 1995) was a British economist and winner of the 1977 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences jointly with the Swedish economist Bertil Ohlin for their "pathbreaking contribution to the ...

) asserting that the total amount of money that disappears into ''culs-de-sac'' is equal to the original outlay, which in Kahn's words "should bring relief and consolation to those who are worried about the monetary sources" (p. 189).

A respending multiplier had been proposed earlier by Hawtrey in a 1928 Treasury memorandum ("with imports as the only leakage"), but the idea was discarded in his own subsequent writings. Soon afterwards the Australian economist

Lyndhurst Giblin

Lyndhurst Falkiner Giblin, (29 November 1872 – 1 March 1951) was an Australian statistician and economist. He was an unsuccessful gold prospector, played rugby union for England, and fought in the First World War.

Biography

Giblin was th ...

published a multiplier analysis in a 1930 lecture (again with imports as the only leakage). The idea itself was much older. Some Dutch

mercantilists

Mercantilism is an economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports for an economy. It promotes imperialism, colonialism, tariffs and subsidies on traded goods to achieve that goal. The policy aims to reduce ...

had believed in an infinite multiplier for military expenditure (assuming no import "leakage"), since ...

... a war could support itself for an unlimited period if only money remained in the country ... For if money itself is "consumed", this simply means that it passes into someone else's possession, and this process may continue indefinitely.

Multiplier doctrines had subsequently been expressed in more theoretical terms by the Dane

Julius Wulff

Julius Wulff (1852-1924) was a Danish conservative politician and journalist. His formal studies were in Zoology and he worked as a teacher in Hjørring

Hjørring () is a town on the island of Vendsyssel-Thy at the top of the Jutland peninsula ...

(1896), the Australian

Alfred de Lissa

Alfred de Lissa (1838 – 25 February 1913) was an English-born Australian solicitor and legal scholar.

He was born in London to Solomon Aaron de Lissa and Rosetta Solomon. He attended University College London and in 1854 migrated to Sydney, ...

(late 1890s), the German/American

Nicholas Johannsen

Nicholas August Ludwig Jacob Johansen (1844–1928) was a German-American amateur economist, today best known for his influence on and citation by John Maynard Keynes. He wrote under two pen names: A. Merwin and J. J. O. Lahn.

Influence

He wa ...

(same period), and the Dane Fr. Johannsen (1925/1927). Kahn himself said that the idea was given to him as a child by his father.

Public policy debates

As the 1929 election approached "Keynes was becoming a strong public advocate of capital development" as a public measure to alleviate unemployment. Winston Churchill, the Conservative Chancellor, took the opposite view:

It is the orthodox Treasury dogma, steadfastly held ... hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

very little additional employment and no permanent additional employment can, in fact, be created by State borrowing and State expenditure.

Keynes pounced on a flaw in the

Treasury view

In macroeconomics, particularly in the history of economic thought, the Treasury view is the assertion that fiscal policy has ''no'' effect on the total amount of economic activity and unemployment, even during times of economic recession. This v ...

. Cross-examining Sir Richard Hopkins, a Second Secretary in the Treasury, before the

Macmillan Committee The Macmillan Committee, officially known as the Committee on Finance and Industry, was a committee, composed mostly of economists, formed by the British government after the 1929 stock market crash to determine the root causes of the depressed eco ...

on Finance and Industry in 1930 he referred to the "first proposition" that "schemes of capital development are of no use for reducing unemployment" and asked whether "it would be a misunderstanding of the Treasury view to say that they hold to the first proposition". Hopkins responded that "The first proposition goes much too far. The first proposition would ascribe to us an absolute and rigid dogma, would it not?"

Later the same year, speaking in a newly created Committee of Economists, Keynes tried to use Kahn's emerging multiplier theory to argue for public works, "but Pigou's and Henderson's objections ensured that there was no sign of this in the final product". In 1933 he gave wider publicity to his support for Kahn's multiplier in a series of articles titled "The road to prosperity" in ''The Times'' newspaper.

A. C. Pigou

Arthur Cecil Pigou (; 18 November 1877 – 7 March 1959) was an English economist. As a teacher and builder of the School of Economics at the University of Cambridge, he trained and influenced many Cambridge economists who went on to take chair ...

was at the time the sole economics professor at Cambridge. He had a continuing interest in the subject of unemployment, having expressed the view in his popular ''Unemployment'' (1913) that it was caused by "maladjustment between wage-rates and demand" – a view Keynes may have shared prior to the years of the ''General Theory''. Nor were his practical recommendations very different: "on many occasions in the thirties" Pigou "gave public support ... to State action designed to stimulate employment". Where the two men differed is in the link between theory and practice. Keynes was seeking to build theoretical foundations to support his recommendations for public works while Pigou showed no disposition to move away from classical doctrine. Referring to him and

Dennis Robertson, Keynes asked rhetorically: "Why do they insist on maintaining theories from which their own practical conclusions cannot possibly follow?"

The ''General Theory''

Keynes set forward the ideas that became the basis for Keynesian economics in his main work, ''

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

''The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money'' is a book by English economist John Maynard Keynes published in February 1936. It caused a profound shift in economic thought, giving macroeconomics a central place in economic theory and ...

'' (1936). It was written during the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, when unemployment rose to 25% in the United States and as high as 33% in some countries. It is almost wholly theoretical, enlivened by occasional passages of satire and social commentary. The book had a profound impact on economic thought, and ever since it was published there has been debate over its meaning.

Keynes and classical economics

Keynes begins the ''General Theory'' with a summary of the classical theory of employment, which he encapsulates in his formulation of

Say's Law

In classical economics, Say's law, or the law of markets, is the claim that the production of a product creates demand for another product by providing something of value which can be exchanged for that other product. So, production is the source ...

as the dictum "

Supply creates its own demand

"Supply creates its own demand" is the formulation of Say's law. The rejection of this doctrine is a central component of '' The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money'' (1936) and a central tenet of Keynesian economics. See Principle o ...

".

He also wrote that although his theory was explained in terms of an Anglo-Saxon ''laissez faire'' economy, his theory was also more general in the sense that it would be easier to adapt to "totalitarian states" than a free market policy would.

Under the classical theory, the wage rate is determined by the

marginal productivity of labour, and as many people are employed as are willing to work at that rate. Unemployment may arise through

friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of t ...

or may be "voluntary," in the sense that it arises from a refusal to accept employment owing to "legislation or social practices ... or mere human obstinacy", but "...the classical postulates do not admit of the possibility of the third category," which Keynes defines as ''

involuntary unemployment''.

Keynes raises two objections to the classical theory's assumption that "wage bargains ... determine the real wage". The first lies in the fact that "labour stipulates (within limits) for a money-wage rather than a real wage". The second is that classical theory assumes that, "The real wages of labour depend on the wage bargains which labour makes with the entrepreneurs," whereas, "If money wages change, one would have expected the classical school to argue that prices would change in almost the same proportion, leaving the real wage and the level of unemployment practically the same as before." Keynes considers his second objection the more fundamental, but most commentators concentrate on his first one: it has been argued that the

quantity theory of money

In monetary economics, the quantity theory of money (often abbreviated QTM) is one of the directions of Western economic thought that emerged in the 16th-17th centuries. The QTM states that the general price level of goods and services is directly ...

protects the classical school from the conclusion Keynes expected from it.

Keynesian unemployment

Saving and investment

Saving

Saving is income not spent, or deferred consumption. Methods of saving include putting money aside in, for example, a deposit account, a pension account, an investment fund, or as cash. Saving also involves reducing expenditures, such as recur ...

is that part of income not devoted to

consumption

Consumption may refer to:

*Resource consumption

*Tuberculosis, an infectious disease, historically

* Consumption (ecology), receipt of energy by consuming other organisms

* Consumption (economics), the purchasing of newly produced goods for curren ...

, and consumption is that part of expenditure not allocated to

investment

Investment is the dedication of money to purchase of an asset to attain an increase in value over a period of time. Investment requires a sacrifice of some present asset, such as time, money, or effort.

In finance, the purpose of investing i ...

, i.e., to durable goods. Hence saving encompasses hoarding (the accumulation of income as cash) and the purchase of durable goods. The existence of net hoarding, or of a demand to hoard, is not admitted by the simplified liquidity preference model of the ''General Theory''.

Once he rejects the classical theory that unemployment is due to excessive wages, Keynes proposes an alternative based on the relationship between saving and investment. In his view, unemployment arises whenever entrepreneurs' incentive to invest fails to keep pace with society's propensity to save (''propensity'' is one of Keynes's synonyms for "demand"). The levels of saving and investment are necessarily equal, and income is therefore held down to a level where the desire to save is no greater than the incentive to invest.

The incentive to invest arises from the interplay between the physical circumstances of production and psychological anticipations of future profitability; but once these things are given the incentive is independent of income and depends solely on the rate of interest ''r''. Keynes designates its value as a function of ''r'' as the "schedule of the

marginal efficiency of capital

Marginal may refer to:

* ''Marginal'' (album), the third album of the Belgian rock band Dead Man Ray, released in 2001

* ''Marginal'' (manga)

* '' El Marginal'', Argentine TV series

* Marginal seat or marginal constituency or marginal, in polit ...

".

The propensity to save behaves quite differently. Saving is simply that part of income not devoted to consumption, and:

... the prevailing psychological law seems to be that when aggregate income increases, consumption expenditure will also increase but to a somewhat lesser extent.

Keynes adds that "this psychological law was of the utmost importance in the development of my own thought".

Liquidity preference

Keynes viewed the

money supply

In macroeconomics, the money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of currency held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include Circulation (curren ...

as one of the main determinants of the state of the real economy. The significance he attributed to it is one of the innovative features of his work, and was influential on the politically hostile

monetarist school.

Money supply comes into play through the ''

liquidity preference

__NOTOC__

In macroeconomic theory, liquidity preference is the demand for money, considered as liquidity. The concept was first developed by John Maynard Keynes in his book '' The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money'' (1936) to e ...

'' function, which is the demand function that corresponds to money supply. It specifies the amount of money people will seek to hold according to the state of the economy. In Keynes's first (and simplest) account – that of Chapter 13 – liquidity preference is determined solely by the

interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, th ...

''r''—which is seen as the earnings forgone by holding wealth in liquid form: hence liquidity preference can be written ''L''(''r'' ) and in equilibrium must equal the externally fixed money supply ''M̂''.

Keynes’s economic model

Money supply, saving and investment combine to determine the level of income as illustrated in the diagram, where the top graph shows money supply (on the vertical axis) against interest rate. ''M̂'' determines the ruling interest rate ''r̂'' through the liquidity preference function. The rate of interest determines the level of investment ''Î'' through the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital, shown as a blue curve in the lower graph. The red curves in the same diagram show what the propensities to save are for different incomes ''Y'' ; and the income ''Ŷ'' corresponding to the equilibrium state of the economy must be the one for which the implied level of saving at the established interest rate is equal to ''Î''.

In Keynes's more complicated liquidity preference theory (presented in Chapter 15) the demand for money depends on income as well as on the interest rate and the analysis becomes more complicated. Keynes never fully integrated his second liquidity preference doctrine with the rest of his theory, leaving that to

John Hicks

Sir John Richards Hicks (8 April 1904 – 20 May 1989) was a British economist. He is considered one of the most important and influential economists of the twentieth century. The most familiar of his many contributions in the field of economic ...

: see

the IS-LM model below.

Wage rigidity

Keynes rejects the classical explanation of unemployment based on wage rigidity, but it is not clear what effect the wage rate has on unemployment in his system. He treats wages of all workers as proportional to a single rate set by collective bargaining, and chooses his units so that this rate never appears separately in his discussion. It is present implicitly in those quantities he expresses in

wage unit

The wage unit is a unit of measurement for monetary quantities introduced by Keynes in his 1936 book ''The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money'' (''General Theory''). A value expressed in wage units is equal to its price in money units ...

s, while being absent from those he expresses in money terms. It is therefore difficult to see whether, and in what way, his results differ for a different wage rate, nor is it clear what he thought about the matter.

Remedies for unemployment

Monetary remedies

An increase in the money supply, according to Keynes's theory, leads to a drop in the interest rate and an increase in the amount of investment that can be undertaken profitably, bringing with it an increase in total income.

Fiscal remedies

Keynes' name is associated with fiscal, rather than monetary, measures but they receive only passing (and often satirical) reference in the ''General Theory''. He mentions "increased public works" as an example of something that brings employment through the ''multiplier'', but this is before he develops the relevant theory, and he does not follow up when he gets to the theory.

Later in the same chapter he tells us that:

Ancient Egypt was doubly fortunate, and doubtless owed to this its fabled wealth, in that it possessed two activities, namely, pyramid-building as well as the search for the precious metals, the fruits of which, since they could not serve the needs of man by being consumed, did not stale with abundance. The Middle Ages built cathedrals and sang dirges. Two pyramids, two masses for the dead, are twice as good as one; but not so two railways from London to York.

But again, he doesn't get back to his implied recommendation to engage in public works, even if not fully justified from their direct benefits, when he constructs the theory. On the contrary he later advises us that ...

... our final task might be to select those variables which can be deliberately controlled or managed by central authority in the kind of system in which we actually live ...

and this appears to look forward to a future publication rather than to a subsequent chapter of the ''General Theory''.

Keynesian models and concepts

Aggregate demand

Keynes' view of saving and investment was his most important departure from the classical outlook. It can be illustrated using the "

Keynesian cross

The Keynesian cross diagram is a formulation of the central ideas in Keynes' ''General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money''. It first appeared as a central component of macroeconomic theory as it was taught by Paul Samuelson in his textbook ...

" devised by

Paul Samuelson

Paul Anthony Samuelson (May 15, 1915 – December 13, 2009) was an American economist who was the first American to win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. When awarding the prize in 1970, the Swedish Royal Academies stated that he " ...

. The horizontal axis denotes total income and the purple curve shows ''C'' (''Y'' ), the propensity to consume, whose complement ''S'' (''Y'' ) is the propensity to save: the sum of these two functions is equal to total income, which is shown by the broken line at 45°.

The horizontal blue line ''I'' (''r'' ) is the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital whose value is independent of ''Y''. The schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital is dependent on the interest rate, specifically the interest rate cost of a new investment. If the interest rate charged by the financial sector to the productive sector is below the marginal efficiency of capital at that level of technology and capital intensity then investment is positive and grows the lower the interest rate is, given the diminishing return of capital. If the interest rate is above the marginal efficiency of capital then investment is equal to zero. Keynes interprets this as the demand for investment and denotes the sum of demands for consumption and investment as "

aggregate demand", plotted as a separate curve. Aggregate demand must equal total income, so equilibrium income must be determined by the point where the aggregate demand curve crosses the 45° line. This is the same horizontal position as the intersection of ''I'' (''r'' ) with ''S'' (''Y'' ).

The equation ''I'' (''r'' ) = ''S'' (''Y'' ) had been accepted by the classics, who had viewed it as the condition of equilibrium between supply and demand for investment funds and as determining the interest rate (see

the classical theory of interest). But insofar as they had had a concept of aggregate demand, they had seen the demand for investment as being given by ''S'' (''Y'' ), since for them saving was simply the indirect purchase of capital goods, with the result that aggregate demand was equal to total income as an identity rather than as an equilibrium condition. Keynes takes note of this view in Chapter 2, where he finds it present in the early writings of

Alfred Marshall but adds that "the doctrine is never stated to-day in this crude form".

The equation ''I'' (''r'' ) = ''S'' (''Y'' ) is accepted by Keynes for some or all of the following reasons:

* As a consequence of the ''principle of effective demand'', which asserts that aggregate demand must equal total income (Chapter 3).

* As a consequence of the identity of saving with investment (Chapter 6) together with the equilibrium assumption that these quantities are equal to their demands.

* In agreement with the substance of the classical theory of the investment funds market, whose conclusion he considers the classics to have misinterpreted through circular reasoning (Chapter 14).

The Keynesian multiplier

Keynes introduces his discussion of the multiplier in Chapter 10 with a reference to Kahn's earlier paper (see

below). He designates Kahn's multiplier the "employment multiplier" in distinction to his own "investment multiplier" and says that the two are only "a little different". Kahn's multiplier has consequently been understood by much of the Keynesian literature as playing a major role in Keynes's own theory, an interpretation encouraged by the difficulty of understanding Keynes's presentation. Kahn's multiplier gives the title ("The multiplier model") to the account of Keynesian theory in Samuelson's ''Economics'' and is almost as prominent in

Alvin Hansen

Alvin Harvey Hansen (August 23, 1887 – June 6, 1975) was an American economist who taught at the University of Minnesota and was later a chair professor of economics at Harvard University. Often referred to as "the American Keynes", he was a w ...

's ''Guide to Keynes'' and in

Joan Robinson

Joan Violet Robinson (''née'' Maurice; 31 October 1903 – 5 August 1983) was a British economist well known for her wide-ranging contributions to economic theory. She was a central figure in what became known as post-Keynesian economics.

B ...

's ''Introduction to the Theory of Employment''.

Keynes states that there is ...

... a confusion between the logical theory of the multiplier, which holds good continuously, without time-lag ... and the consequence of an expansion in the capital goods industries which take gradual effect, subject to a time-lag, and only after an interval ...

and implies that he is adopting the former theory. And when the multiplier eventually emerges as a component of Keynes's theory (in Chapter 18) it turns out to be simply a measure of the change of one variable in response to a change in another. The schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital is identified as one of the independent variables of the economic system: "What

ttells us, is ... the point to which the output of new investment will be pushed ..." The multiplier then gives "the ratio ... between an increment of investment and the corresponding increment of aggregate income".

G. L. S. Shackle

George Lennox Sharman Shackle (14 July 1903 – 3 March 1992) was an English economist. He made a practical attempt to challenge classical rational choice theory and has been characterised as a "post-Keynesian", though he is influenced as well by ...

regarded Keynes' move away from Kahn's multiplier as ...

... a retrograde step ... For when we look upon the Multiplier as an instantaneous functional relation ... we are merely using the word Multiplier to stand for an alternative way of looking at the marginal propensity to consume ...,

which G. M. Ambrosi cites as an instance of "a Keynesian commentator who would have liked Keynes to have written something less 'retrograde.

The value Keynes assigns to his multiplier is the reciprocal of the marginal propensity to save: ''k'' = 1 / ''S'' '(''Y'' ). This is the same as the formula for Kahn's mutliplier in a closed economy assuming that all saving (including the purchase of durable goods), and not just hoarding, constitutes leakage. Keynes gave his formula almost the status of a definition (it is put forward in advance of any explanation). His multiplier is indeed the value of "the ratio ... between an increment of investment and the corresponding increment of aggregate income" as Keynes derived it from his Chapter 13 model of liquidity preference, which implies that income must bear the entire effect of a change in investment. But under his Chapter 15 model a change in the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital has an effect shared between the interest rate and income in proportions depending on the partial derivatives of the liquidity preference function. Keynes did not investigate the question of whether his formula for multiplier needed revision.

The liquidity trap

The

liquidity trap is a phenomenon that may impede the effectiveness of monetary policies in reducing unemployment.

Economists generally think the rate of interest will not fall below a certain limit, often seen as zero or a slightly negative number. Keynes suggested that the limit might be appreciably greater than zero but did not attach much practical significance to it. The term "liquidity trap" was coined by

Dennis Robertson in his comments on the ''General Theory'', but it was

John Hicks

Sir John Richards Hicks (8 April 1904 – 20 May 1989) was a British economist. He is considered one of the most important and influential economists of the twentieth century. The most familiar of his many contributions in the field of economic ...

in "

Mr. Keynes and the Classics" who recognised the significance of a slightly different concept.

If the economy is in a position such that the liquidity preference curve is almost vertical, as must happen as the lower limit on ''r'' is approached, then a change in the money supply ''M̂'' makes almost no difference to the equilibrium rate of interest ''r̂'' or, unless there is compensating steepness in the other curves, to the resulting income ''Ŷ''. As Hicks put it, "Monetary means will not force down the rate of interest any further."

Paul Krugman has worked extensively on the liquidity trap, claiming that it was the problem confronting the Japanese economy around the turn of the millennium. In his later words:

Short-term interest rates were close to zero, long-term rates were at historical lows, yet private investment spending remained insufficient to bring the economy out of deflation. In that environment, monetary policy was just as ineffective as Keynes described. Attempts by the Bank of Japan to increase the money supply simply added to already ample bank reserves and public holdings of cash...

The IS–LM model

Hicks showed how to analyze Keynes' system when liquidity preference is a function of income as well as of the rate of interest. Keynes's admission of income as an influence on the demand for money is a step back in the direction of classical theory, and Hicks takes a further step in the same direction by generalizing the propensity to save to take both ''Y'' and ''r'' as arguments. Less classically he extends this generalization to the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital.

The

IS-LM model uses two equations to express Keynes' model. The first, now written ''I'' (''Y'', ''r'' ) = ''S'' (''Y'',''r'' ), expresses the principle of effective demand. We may construct a graph on (''Y'', ''r'' ) coordinates and draw a line connecting those points satisfying the equation: this is the ''IS'' curve. In the same way we can write the equation of equilibrium between liquidity preference and the money supply as ''L''(''Y'' ,''r'' ) = ''M̂'' and draw a second curve – the ''LM'' curve – connecting points that satisfy it. The equilibrium values ''Ŷ'' of total income and ''r̂'' of interest rate are then given by the point of intersection of the two curves.

If we follow Keynes's initial account under which liquidity preference depends only on the interest rate ''r'', then the ''LM'' curve is horizontal.

Joan Robinson

Joan Violet Robinson (''née'' Maurice; 31 October 1903 – 5 August 1983) was a British economist well known for her wide-ranging contributions to economic theory. She was a central figure in what became known as post-Keynesian economics.

B ...

commented that:

... modern teaching has been confused by J. R. Hicks' attempt to reduce the ''General Theory'' to a version of static equilibrium with the formula IS–LM. Hicks has now repented and changed his name from J. R. to John, but it will take a long time for the effects of his teaching to wear off.

Hicks subsequently relapsed.

Keynesian economic policies

Active fiscal policy

Keynes argued that the solution to the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

was to stimulate the country ("incentive to invest") through some combination of two approaches:

# A reduction in interest rates (monetary policy), and

# Government investment in infrastructure (fiscal policy).

If the interest rate at which businesses and consumers can borrow decreases, investments that were previously uneconomic become profitable, and large consumer sales normally financed through debt (such as houses, automobiles, and, historically, even appliances like refrigerators) become more affordable. A principal function of

central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the currency and monetary policy of a country or monetary union,

and oversees their commercial banking system. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central ba ...

s in countries that have them is to influence this interest rate through a variety of mechanisms collectively called ''monetary policy''. This is how monetary policy that reduces interest rates is thought to stimulate economic activity, i.e., "grow the economy"—and why it is called ''expansionary'' monetary policy.

Expansionary fiscal policy consists of increasing net public spending, which the government can effect by a) taxing less, b) spending more, or c) both. Investment and consumption by government raises demand for businesses' products and for employment, reversing the effects of the aforementioned imbalance. If desired spending exceeds revenue, the government finances the difference by borrowing from

capital market

A capital market is a financial market in which long-term debt (over a year) or equity-backed securities are bought and sold, in contrast to a money market where short-term debt is bought and sold. Capital markets channel the wealth of savers t ...

s by issuing government bonds. This is called deficit spending. Two points are important to note at this point. First, deficits are not required for expansionary fiscal policy, and second, it is only ''change'' in net spending that can stimulate or depress the economy. For example, if a government ran a deficit of 10% both last year and this year, this would represent neutral fiscal policy. In fact, if it ran a deficit of 10% last year and 5% this year, this would actually be contractionary. On the other hand, if the government ran a surplus of 10% of GDP last year and 5% this year, that would be expansionary fiscal policy, despite never running a deficit at all.

But – contrary to some critical characterizations of it – Keynesianism does not consist solely of

deficit spending

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit; the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budget ...

, since it recommends adjusting fiscal policies according to cyclical circumstances. An example of a counter-cyclical policy is raising taxes to cool the economy and to prevent inflation when there is abundant demand-side growth, and engaging in deficit spending on labour-intensive infrastructure projects to stimulate employment and stabilize wages during economic downturns.

Keynes's ideas influenced

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's view that insufficient buying-power caused the Depression. During his presidency, Roosevelt adopted some aspects of Keynesian economics, especially after 1937, when, in the depths of the Depression, the United States suffered from recession yet again following fiscal contraction. But to many the true success of Keynesian policy can be seen at the onset of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, which provided a kick to the world economy, removed uncertainty, and forced the rebuilding of destroyed capital. Keynesian ideas became almost official in

social-democratic Europe after the war and in the U.S. in the 1960s.

The Keynesian advocacy of deficit spending contrasted with the

classical and

neoclassical economic analysis of fiscal policy. They admitted that fiscal stimulus could actuate production. But, to these schools, there was no reason to believe that this stimulation would outrun the side-effects that "

crowd out" private investment: first, it would increase the demand for labour and raise wages, hurting

profitability

In economics, profit is the difference between the revenue that an economic entity has received from its outputs and the total cost of its inputs. It is equal to total revenue minus total cost, including both explicit and implicit costs.

It i ...

; Second, a government deficit increases the stock of government bonds, reducing their market price and encouraging high

interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, th ...

s, making it more expensive for business to finance

fixed investment

Fixed investment in economics is the purchasing of newly produced fixed capital. It is measured as a flow variable – that is, as an amount per unit of time.

Thus, fixed investment is the accumulation of physical assets such as machinery, land ...

. Thus, efforts to stimulate the economy would be self-defeating.

The Keynesian response is that such fiscal policy is appropriate only when unemployment is persistently high, above the

(NAIRU). In that case, crowding out is minimal. Further, private investment can be "crowded in": Fiscal stimulus raises the market for business output, raising cash flow and profitability, spurring business optimism. To Keynes, this

accelerator effect

The accelerator effect in economics is a positive effect on private fixed investment of the growth of the market economy (measured e.g. by a change in Gross Domestic Product). Rising GDP (an economic boom or prosperity) implies that businesses in g ...

meant that government and business could be ''

complements'' rather than

substitutes in this situation.

Second, as the stimulus occurs, gross domestic product rises—raising the amount of

saving

Saving is income not spent, or deferred consumption. Methods of saving include putting money aside in, for example, a deposit account, a pension account, an investment fund, or as cash. Saving also involves reducing expenditures, such as recur ...

, helping to finance the increase in fixed investment. Finally, government outlays need not always be wasteful: government investment in

public goods that is not provided by profit-seekers encourages the private sector's growth. That is, government spending on such things as basic research, public health, education, and infrastructure could help the long-term growth of ''

potential output

In economics, potential output (also referred to as "natural gross domestic product") refers to the highest level of real gross domestic product (potential output) that can be sustained over the long term. Actual output happens in real life while ...

''.

In Keynes's theory, there must be significant

slack in the labour market before

fiscal expansion is justified.

Keynesian economists believe that adding to profits and incomes during boom cycles through tax cuts, and removing income and profits from the economy through cuts in spending during downturns, tends to exacerbate the negative effects of the business cycle. This effect is especially pronounced when the government controls a large fraction of the economy, as increased tax revenue may aid investment in state enterprises in downturns, and decreased state revenue and investment harm those enterprises.

Views on trade imbalance

In the last few years of his life,

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

was much preoccupied with the question of balance in international trade. He was the leader of the British delegation to the

United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference

The Bretton Woods Conference, formally known as the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, was the gathering of 730 delegates from all 44 Allied nations at the Mount Washington Hotel, situated in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United ...

in 1944 that established the

Bretton Woods system of international currency management.

He was the principal author of a proposal – the so-called Keynes Plan – for an

International Clearing Union

The International Clearing Union (ICU) was one of the institutions proposed to be set up at the 1944 United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in the United States, by British economist John Maynard Keynes. ...

. The two governing principles of the plan were that the problem of settling outstanding balances should be solved by 'creating' additional 'international money', and that debtor and creditor should be treated almost alike as disturbers of equilibrium. In the event, though, the plans were rejected, in part because "American opinion was naturally reluctant to accept the principle of equality of treatment so novel in debtor-creditor relationships".

The new system is not founded on free trade (liberalisation of foreign trade) but rather on regulating international trade to eliminate trade imbalances. Nations with a surplus would have a powerful incentive to get rid of it, which would automatically clear other nations' deficits. Keynes proposed a global bank that would issue its own currency—the ''bancor''—which was exchangeable with national currencies at fixed rates of exchange and would become the unit of account between nations, which means it would be used to measure a country's trade deficit or trade surplus. Every country would have an overdraft facility in its bancor account at the International Clearing Union. He pointed out that surpluses lead to weak global aggregate demand – countries running surpluses exert a "negative externality" on trading partners, and posed far more than those in deficit, a threat to global prosperity. Keynes thought that surplus countries should be taxed to avoid trade imbalances.

In ''"National Self-Sufficiency" The Yale Review, Vol. 22, no. 4 (June 1933)'', he already highlighted the problems created by free trade.

His view, supported by many economists and commentators at the time, was that creditor nations may be just as responsible as debtor nations for disequilibrium in exchanges and that both should be under an obligation to bring trade back into a state of balance. Failure for them to do so could have serious consequences. In the words of

Geoffrey Crowther

Geoffrey Crowther, Baron Crowther Kt. (13 May 1907 – 5 February 1972) was a British economist, journalist, educationalist and businessman. He was editor of ''The Economist'' from 1938 to 1956.His major works include 'Economics for Democrats'(1 ...

, then editor of

The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Econo ...

, "If the economic relationships between nations are not, by one means or another, brought fairly close to balance, then there is no set of financial arrangements that can rescue the world from the impoverishing results of chaos."

These ideas were informed by events prior to the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

when – in the opinion of Keynes and others – international lending, primarily by the U.S., exceeded the capacity of sound investment and so got diverted into non-productive and speculative uses, which in turn invited default and a sudden stop to the process of lending.

Influenced by Keynes, economic texts in the immediate post-war period put a significant emphasis on balance in trade. For example, the second edition of the popular introductory textbook, ''An Outline of Money'', devoted the last three of its ten chapters to questions of foreign exchange management and in particular the 'problem of balance'. However, in more recent years, since the end of the

Bretton Woods system in 1971, with the increasing influence of

Monetarist schools of thought in the 1980s, and particularly in the face of large sustained trade imbalances, these concerns – and particularly concerns about the destabilising effects of large trade surpluses – have largely disappeared from

mainstream economics discourse and Keynes' insights have slipped from view. They are receiving some attention again in the wake of the

financial crisis of 2007–08

Finance is the study and discipline of money, currency and capital assets. It is related to, but not synonymous with economics, the study of production, distribution, and consumption of money, assets, goods and services (the discipline of fina ...

.

Views on free trade and protectionism

The turning point of the Great Depression

At the beginning of his career, Keynes was an economist close to

Alfred Marshall, deeply convinced of the benefits of free trade. From the crisis of 1929 onwards, noting the commitment of the British authorities to defend the gold parity of the pound sterling and the rigidity of nominal wages, he gradually adhered to protectionist measures.

On 5 November 1929, when heard by the

Macmillan Committee The Macmillan Committee, officially known as the Committee on Finance and Industry, was a committee, composed mostly of economists, formed by the British government after the 1929 stock market crash to determine the root causes of the depressed eco ...

to bring the British economy out of the crisis, Keynes indicated that the introduction of tariffs on imports would help to rebalance the trade balance. The committee's report states in a section entitled "import control and export aid", that in an economy where there is not full employment, the introduction of tariffs can improve production and employment. Thus the reduction of the trade deficit favours the country's growth.

In January 1930, in the Economic Advisory Council, Keynes proposed the introduction of a system of protection to reduce imports. In the autumn of 1930, he proposed a uniform tariff of 10% on all imports and subsidies of the same rate for all exports.

In the ''Treatise on Money'', published in the autumn of 1930, he took up the idea of tariffs or other trade restrictions with the aim of reducing the volume of imports and rebalancing the balance of trade.

On 7 March 1931, in the ''

New Statesman and Nation

The ''New Statesman'' is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members o ...

'', he wrote an article entitled ''Proposal for a Tariff Revenue''. He pointed out that the reduction of wages led to a reduction in national demand which constrained markets. Instead, he proposes the idea of an expansionary policy combined with a tariff system to neutralise the effects on the balance of trade. The application of customs tariffs seemed to him "unavoidable, whoever the Chancellor of the Exchequer might be". Thus, for Keynes, an economic recovery policy is only fully effective if the trade deficit is eliminated. He proposed a 15% tax on manufactured and semi-manufactured goods and 5% on certain foodstuffs and raw materials, with others needed for exports exempted (wool, cotton).

In 1932, in an article entitled ''The Pro- and Anti-Tariffs'', published in ''

The Listener'', he envisaged the protection of farmers and certain sectors such as the automobile and iron and steel industries, considering them indispensable to Britain.

The critique of the theory of comparative advantage

In the post-crisis situation of 1929, Keynes judged the assumptions of the free trade model unrealistic. He criticised, for example, the neoclassical assumption of wage adjustment.

As early as 1930, in a note to the Economic Advisory Council, he doubted the intensity of the gain from specialisation in the case of manufactured goods. While participating in the MacMillan Committee, he admitted that he no longer "believed in a very high degree of national specialisation" and refused to "abandon any industry which is unable, for the moment, to survive". He also criticised the static dimension of the theory of comparative advantage, which, in his view, by fixing comparative advantages definitively, led in practice to a waste of national resources.

In the Daily Mail of 13 March 1931, he called the assumption of perfect sectoral labour mobility "nonsense" since it states that a person made unemployed contributes to a reduction in the wage rate until he finds a job. But for Keynes, this change of job may involve costs (job search, training) and is not always possible. Generally speaking, for Keynes, the assumptions of full employment and automatic return to equilibrium discredit the theory of comparative advantage.

In July 1933, he published an article in the ''New Statesman and Nation'' entitled ''National Self-Sufficiency'', in which he criticised the argument of the specialisation of economies, which is the basis of free trade. He thus proposed the search for a certain degree of self-sufficiency. Instead of the specialisation of economies advocated by the Ricardian theory of comparative advantage, he prefers the maintenance of a diversity of activities for nations.

In it he refutes the principle of peacemaking trade. His vision of trade became that of a system where foreign capitalists compete for new markets. He defends the idea of producing on national soil when possible and reasonable and expresses sympathy for the advocates of

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulatio ...

.

He notes in ''National Self-Sufficiency'':

He also writes in ''National Self-Sufficiency'':

Later, Keynes had a written correspondence with

James Meade

James Edward Meade, (23 June 1907 – 22 December 1995) was a British economist and winner of the 1977 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences jointly with the Swedish economist Bertil Ohlin for their "pathbreaking contribution to the ...

centred on the issue of import restrictions. Keynes and Meade discussed the best choice between quota and tariff. In March 1944 Keynes began a discussion with

Marcus Fleming

John Marcus Fleming (1911 – 3 February 1976) was a British economist. He was the deputy director of the research department of the International Monetary Fund for many years; he was already a member of this department during the period of ...