Jacques Cousteau on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jacques-Yves Cousteau, (, also , ; 11 June 191025 June 1997) was a French naval officer, oceanographer, filmmaker and author. He co-invented the first successful Aqua-Lung, open-circuit SCUBA (

In the 1960s, Cousteau was involved with a set of three projects to build underwater "villages"; the projects were named Precontinent I, Precontinent II and Precontinent III. Each ensuing project was aimed at increasing the depth at which people continuously lived under water, and were an attempt at creating an environment in which men could live and work on the sea floor. The projects are best known as Conshelf I (1962), Conshelf II (1963), and Conshelf III (1965). The names "Precontinent", and "Continental Shelf Station" (Conshelf) were used interchangeably by Cousteau.

A meeting with American television companies (

In the 1960s, Cousteau was involved with a set of three projects to build underwater "villages"; the projects were named Precontinent I, Precontinent II and Precontinent III. Each ensuing project was aimed at increasing the depth at which people continuously lived under water, and were an attempt at creating an environment in which men could live and work on the sea floor. The projects are best known as Conshelf I (1962), Conshelf II (1963), and Conshelf III (1965). The names "Precontinent", and "Continental Shelf Station" (Conshelf) were used interchangeably by Cousteau.

A meeting with American television companies (

In 1980, Cousteau traveled to Canada to make two films on the

In 1980, Cousteau traveled to Canada to make two films on the

The Cousteau Society

* *

Ocean Treasures Memorial Library

Ocean Treasures Memorial Library/Jacques-Yves Cousteau Memorial

Ocean Treasures Memorial Library/His Legacy

Ocean Treasures Memorial Library/Photos

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cousteau, Jacques-Yves French marine biologists 1910 births 1997 deaths 20th-century French biologists 20th-century explorers 20th-century photographers BAFTA fellows Collège Stanislas de Paris alumni Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur

self-contained underwater breathing apparatus

A scuba set, originally just scuba, is any breathing apparatus that is entirely carried by an underwater diver and provides the diver with breathing gas at the ambient pressure. ''Scuba'' is an anacronym for self-contained underwater breathing ...

). The apparatus assisted him in producing some of the first underwater documentaries.

Cousteau wrote many books describing his undersea explorations. In his first book, '' The Silent World: A Story of Undersea Discovery and Adventure'', Cousteau surmised the existence of the echolocation abilities of porpoises. The book was adapted into an underwater documentary called ''The Silent World

''The Silent World'' (french: Le Monde du silence) is a 1956 French documentary film co-directed by Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle. One of the first films to use underwater cinematography to show the ocean depths in color, its title derives f ...

''. Co-directed by Cousteau and Louis Malle

Louis Marie Malle (; 30 October 1932 – 23 November 1995) was a French film director, screenwriter, and producer who worked in both Cinema of France, French cinema and Cinema of the United States, Hollywood. Described as "eclectic" and "a fi ...

, it was one of the first films to use underwater cinematography to document the ocean depths in color. The film won the 1956 Palme d'Or

The Palme d'Or (; en, Golden Palm) is the highest prize awarded at the Cannes Film Festival. It was introduced in 1955 by the festival's organizing committee. Previously, from 1939 to 1954, the festival's highest prize was the Grand Prix du Fe ...

at the Cannes Film Festival

The Cannes Festival (; french: link=no, Festival de Cannes), until 2003 called the International Film Festival (') and known in English as the Cannes Film Festival, is an annual film festival held in Cannes, France, which previews new films o ...

and remained the only documentary to do so until 2004, when '' Fahrenheit 9/11'' received the award. It was also awarded the Academy Award for Best Documentary

The Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature Film is an award for documentary films. In 1941, the first awards for feature-length documentaries were bestowed as Special Awards to '' Kukan'' and ''Target for Tonight''. They have since been best ...

in 1957.

From 1966 to 1976, he hosted ''The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau

''The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau'' is an American documentary television series about underwater marine life, directed by Alan Landsburg and hosted by French filmmaker, researcher, and marine explorer Jacques Cousteau. The first episod ...

'', a documentary television series, presented on American commercial television stations. A second documentary series, ''The Cousteau Odyssey'', ran from 1977 to 1982 on public television stations.

Biography

Early life

Cousteau was born on 11 June 1910, inSaint-André-de-Cubzac

Saint-André-de-Cubzac (; oc, Sent Andreus de Cubzac) is a commune in the Gironde department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in south-western France.

Its inhabitants are called Cubzaguais.

Population

Notable residents

Jacques-Yves Cousteau is buried ...

, Gironde, France, to Daniel and Élisabeth Cousteau. He had one brother, Pierre-Antoine. Cousteau completed his preparatory studies at the Collège Stanislas in Paris. In 1930, he entered the École navale

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

and graduated as a gunnery officer. However, an automobile accident, which broke both his arms, cut short his career in naval aviation. The accident forced Cousteau to change his plans to become a naval pilot, so he then indulged his passion for the ocean.

In Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

, where he was serving on the ''Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher and mathematician. His ideas, including support for a liberal economy, free and equal pu ...

'', Cousteau carried out his first underwater experiments, thanks to his friend Philippe Tailliez

Philippe Tailliez (; 15 June 1905, Malo-les-Bains – 26 September 2002, Toulon, France) was a friend and colleague of Jacques Cousteau. He was an underwater pioneer, who had been diving since the 1930s.

Biography

He was the younger son of F� ...

who in 1936 lent him some Fernez underwater goggle

Goggles, or safety glasses, are forms of protective eyewear that usually enclose or protect the area surrounding the eye in order to prevent particulates, water or chemicals from striking the eyes. They are used in chemistry laboratories and ...

s, predecessors of modern swimming goggles

Goggles, or safety glasses, are forms of protective eyewear that usually enclose or protect the area surrounding the eye in order to prevent particulates, water or chemicals from striking the eyes. They are used in chemistry laboratories and ...

. Cousteau also belonged to the information service of the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

, and was sent on missions to Shanghai and Japan (1935–1938) and in the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

(1939).

On 12 July 1937, he married Simone Melchior

Simone Cousteau (née Melchior; 19 January 1919 – 1 December 1990) was a French explorer. She was the first woman scuba diver and aquanaut, and wife and business partner of undersea explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

Although never visible in the ...

, his business partner, with whom he had two sons, Jean-Michel

Jean-Michel is a French masculine given name. It may refer to :

* Jean-Michel Arnold, General Secretary of the Cinémathèque Française

* Jean-Michel Atlan (1913–1960), French artist

* Jean-Michel Aulas (born 1949), French businessman

* Jean-Mic ...

(born 1938) and Philippe (1940–1979). His sons took part in the adventures of the '' Calypso''. In 1991, one year after his wife Simone's death from cancer, he married Francine Triplet. They already had a daughter Diane Cousteau (born 1980) and a son, Pierre-Yves Cousteau (born 1982, during Cousteau's marriage to his first wife).

Early 1940s: innovation of modern underwater diving

The years ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

were decisive for the history of diving. After the armistice of 1940, the family of Simone and Jacques-Yves Cousteau took refuge in Megève

Megève (; frp, Megéva) is a commune in the Haute-Savoie department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region in Southeastern France with a population of more than 3,000 residents. The town is well known as a ski resort near Mont Blanc in the French ...

, where he became a friend of the Ichac family who also lived there. Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Marcel Ichac

Marcel Ichac (22 October 1906 - 9 April 1994) was a French alpinist, explorer, photographer and film director. Born in Rueil, France, Ichac was one of the first people to introduce electronic music in cinema with Ondes Martenot for ''Karakoram' ...

shared the same desire to reveal to the general public unknown and inaccessible places — for Cousteau the underwater world and for Ichac the high mountains. The two neighbors took the first ex-aequo

''Ex aequo et bono'' (Latin for "according to the right and good" or "from equity and conscience") is a Latin phrase that is used as a legal term of art. In the context of arbitration, it refers to the power of arbitrators to dispense with conside ...

prize of the Congress of Documentary Film in 1943, for the first French underwater film: ''Par dix-huit mètres de fond'' (''18 meters deep''), made without breathing apparatus the previous year in the Embiez

The Île des Embiez () is a French island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is the largest island in the Embiez archipelago. It is located off the coast of the port of Le Brusc in the commune of Six-Fours-les-Plages, in the Var (department), Var Depart ...

islands in Var

Var or VAR may refer to:

Places

* Var (department), a department of France

* Var (river), France

* Vār, Iran, village in West Azerbaijan Province, Iran

* Var, Iran (disambiguation), other places in Iran

* Vár, a village in Obreja commune, Ca ...

, with Philippe Tailliez

Philippe Tailliez (; 15 June 1905, Malo-les-Bains – 26 September 2002, Toulon, France) was a friend and colleague of Jacques Cousteau. He was an underwater pioneer, who had been diving since the 1930s.

Biography

He was the younger son of F� ...

and Frédéric Dumas

Frédéric Dumas (14 January 1913 – 26 July 1991) was a French writer. He was part of a team of three, with Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Philippe Tailliez, who had a passion for diving, and developed the diving regulator with the aid of the enginee ...

, using a depth-pressure-proof camera case developed by mechanical engineer Léon Vèche, an engineer of Arts and Measures at the Naval College.

In 1943, they made the film ''Épaves'' (''Shipwrecks''), in which they used two of the very first Aqua-Lung prototypes. These prototypes were made in Boulogne-Billancourt

Boulogne-Billancourt (; often colloquially called simply Boulogne, until 1924 Boulogne-sur-Seine, ) is a wealthy and prestigious Communes of France, commune in the Parisian area, located from its Kilometre zero, centre. It is a Subprefectures in ...

by the Air Liquide

Air Liquide S.A. (; ; literally "liquid air"), is a French multinational company which supplies industrial gases and services to various industries including medical, chemical and electronic manufacturers. Founded in 1902, after Linde it is ...

company, following instructions from Cousteau and Émile Gagnan

Émile Gagnan (1900 – 1984) was a French engineer and, in 1943, co-inventor with French Navy diver Jacques-Yves Cousteau of the Aqua-Lung, the diving regulator (a.k.a. demand-valve) used for the first Scuba equipment. The demand-valve, or re ...

. When making ''Épaves'', Cousteau could not find the necessary blank reels of movie film, but had to buy hundreds of small still camera film reels the same width, intended for a make of child's camera, and cemented them together to make long reels.''The Silent World

''The Silent World'' (french: Le Monde du silence) is a 1956 French documentary film co-directed by Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle. One of the first films to use underwater cinematography to show the ocean depths in color, its title derives f ...

''. J. Y. Cousteau with Frédéric Dumas. Hamish Hamilton, London. 1953

Having kept bonds with the English speakers (he spent part of his childhood in the United States and usually spoke English) and with French soldiers in North Africa (under Admiral Lemonnier), Jacques-Yves Cousteau (whose villa "Baobab" at Sanary

Sanary-sur-Mer (, literally ''Sanary on Sea''; oc, Sant Nari), popularly known as Sanary, is a commune in the Var department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, Southeastern France. In 2018, it had a population of 16,696. Sanary-sur-Mer i ...

(Var

Var or VAR may refer to:

Places

* Var (department), a department of France

* Var (river), France

* Vār, Iran, village in West Azerbaijan Province, Iran

* Var, Iran (disambiguation), other places in Iran

* Vár, a village in Obreja commune, Ca ...

) was opposite Admiral Darlan's villa "Reine"), helped the French Navy to join again with the Allies; he assembled a commando operation against the Italian espionage services in France, and received several military decorations for his deeds. At that time, he kept his distance from his brother Pierre-Antoine Cousteau, a "pen anti-semite" who wrote the collaborationist newspaper ''Je suis partout

''Je suis partout'' (, lit. ''I am everywhere'') was a French newspaper founded by , first published on 29 November 1930. It was placed under the direction of Pierre Gaxotte until 1939. Journalists of the paper included Lucien Rebatet, , the illu ...

'' (''I am everywhere'') and who received the death sentence in 1946. However, this was later commuted to a life sentence, and Pierre-Antoine was released in 1954.

During the 1940s, Cousteau is credited with improving the Aqua-Lung design which gave birth to the open-circuit scuba

A scuba set, originally just scuba, is any breathing apparatus that is entirely carried by an underwater diver and provides the diver with breathing gas at the ambient pressure. ''Scuba'' is an anacronym for self-contained underwater breathing ...

technology used today. According to his first book, '' The Silent World: A Story of Undersea Discovery and Adventure'' (1953), Cousteau started diving with Fernez goggles in 1936, and in 1939 used the self-contained underwater breathing apparatus invented in 1926 by Commander Yves le Prieur. Cousteau was not satisfied with the length of time he could spend underwater with the Le Prieur apparatus so he improved it to extend underwater duration by adding a demand regulator, invented in 1942 by Émile Gagnan

Émile Gagnan (1900 – 1984) was a French engineer and, in 1943, co-inventor with French Navy diver Jacques-Yves Cousteau of the Aqua-Lung, the diving regulator (a.k.a. demand-valve) used for the first Scuba equipment. The demand-valve, or re ...

. In 1943 Cousteau tried out the first prototype Aqua-Lung which finally made extended underwater exploration possible.

Late 1940s: GERS and ''Élie Monnier''

In 1946, Cousteau and Tailliez showed the film ''Épaves'' ("Shipwrecks") to Admiral Lemonnier, who gave them the responsibility of setting up the Groupement de Recherches Sous-marines (GRS) (Underwater Research Group) of theFrench Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

in Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

. A little later it became the GERS (Groupe d'Études et de Recherches Sous-Marines, = Underwater Studies and Research Group), then the COMISMER ("COMmandement des Interventions Sous la MER", = "Undersea Interventions Command"), and finally more recently the CEPHISMER. In 1947, Chief Petty Officer

A chief petty officer (CPO) is a senior non-commissioned officer in many navies and coast guards.

Canada

"Chief petty officer" refers to two ranks in the Royal Canadian Navy. A chief petty officer 2nd class (CPO2) (''premier maître de deuxi ...

Maurice Fargues

Maurice Fargues (April 23, 1913 – September 17, 1947) was a diver with the French Navy and a close associate of commander Philippe Tailliez and deputy commander Jacques Cousteau. In August 1946, Fargues saved the lives of Cousteau and Frédéri ...

became the first diver to die using an aqualung, while attempting a new depth record with the GERS near Toulon.

In 1948, between missions of mine clearance, underwater exploration and technological and physiological tests, Cousteau undertook a first campaign in the Mediterranean on board the sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

''Élie Monnier'', According to Sevellec, the ''Élie Monnier'' was an old German tugboat originally called ''Albatros'' and handed over to France as a war reparation, and then re-baptised in honor of the maritime engineer Élie Monnier who had disappeared while diving at Mers-el-Kébir on the wreck of the battleship '' Bretagne'' with Philippe Tailliez, Frédéric Dumas, Jean Alinat and the scenario writer Marcel Ichac. The small team also undertook the exploration of the Roman wreck of Mahdia (Tunisia). It was the first underwater archaeology operation using autonomous diving, opening the way for scientific underwater archaeology. Cousteau and Marcel Ichac brought back from there the Carnets diving film (presented and preceded with the Cannes Film Festival

The Cannes Festival (; french: link=no, Festival de Cannes), until 2003 called the International Film Festival (') and known in English as the Cannes Film Festival, is an annual film festival held in Cannes, France, which previews new films o ...

1951).

Cousteau and the ''Élie Monnier'' then took part in the rescue of Professor Jacques Piccard

Jacques Piccard (28 July 19221 November 2008) was a Swiss oceanographer and engineer, known for having developed underwater submarines for studying ocean currents. In the Challenger Deep, he and Lt. Don Walsh of the United States Navy were the f ...

's bathyscaphe, the FNRS-2

The ''FNRS-2'' was the first bathyscaphe. It was created by Auguste Piccard. Work started in 1937 but was interrupted by World War II. The deep-diving submarine was finished in 1948. The bathyscaphe was named after the Belgian Fonds National ...

, during the 1949 expedition to Dakar. Thanks to this rescue, the French Navy was able to reuse the sphere of the bathyscaphe to construct the FNRS-3

The ''FNRS-3'' or ''FNRS III'' is a bathyscaphe of the French Navy. It is currently preserved at Toulon. She set world depth records, competing against a more refined version of her design, the ''Trieste''. The French Navy eventually replaced ...

.

The adventures of this period are told in the two books ''The Silent World

''The Silent World'' (french: Le Monde du silence) is a 1956 French documentary film co-directed by Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle. One of the first films to use underwater cinematography to show the ocean depths in color, its title derives f ...

'' (1953, by Cousteau and Dumas) and ''Plongées sans câble'' (1954, by Philippe Tailliez

Philippe Tailliez (; 15 June 1905, Malo-les-Bains – 26 September 2002, Toulon, France) was a friend and colleague of Jacques Cousteau. He was an underwater pioneer, who had been diving since the 1930s.

Biography

He was the younger son of F� ...

).

1950–1970s

In 1949, Cousteau left theFrench Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

.

In 1950, he founded the French Oceanographic Campaigns (FOC), and leased a ship called ''Calypso'' from Thomas Loel Guinness

Group Captain Thomas Loel Evelyn Bulkeley Guinness, (9 June 1906 – 31 December 1988) was a British Conservative politician, Member of Parliament (MP) for Bath (1931–1945), business magnate and philanthropist. Guinness also financed the ...

for a symbolic one franc a year. Cousteau refitted the ''Calypso'' as a mobile laboratory for field research and as his principal vessel for diving and filming. He also carried out underwater archaeological excavations in the Mediterranean, in particular at Grand-Congloué (1952).

With the publication of his first book in 1953, ''The Silent World

''The Silent World'' (french: Le Monde du silence) is a 1956 French documentary film co-directed by Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle. One of the first films to use underwater cinematography to show the ocean depths in color, its title derives f ...

'', Cousteau correctly predicted the existence of the echolocation abilities of porpoises. He reported that his research vessel, the ''Élie Monier'', was heading to the Straits of Gibraltar and noticed a group of porpoises following them. Cousteau changed course a few degrees off the optimal course to the center of the strait, and the porpoises followed for a few minutes, then diverged toward mid-channel again. It was evident that they knew where the optimal course lay, even if the humans did not. Cousteau concluded that the cetaceans had something like sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigation, navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect o ...

, which was a relatively new feature on submarines.

In 1954, Cousteau conducted a survey of Abu Dhabi

Abu Dhabi (, ; ar, أَبُو ظَبْيٍ ' ) is the capital and second-most populous city (after Dubai) of the United Arab Emirates. It is also the capital of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi and the centre of the Abu Dhabi Metropolitan Area.

...

waters on behalf of British Petroleum. Among those accompanying him was Louis Malle

Louis Marie Malle (; 30 October 1932 – 23 November 1995) was a French film director, screenwriter, and producer who worked in both Cinema of France, French cinema and Cinema of the United States, Hollywood. Described as "eclectic" and "a fi ...

who made a black-and-white film of the expedition for the company. Cousteau won the Palme d'Or

The Palme d'Or (; en, Golden Palm) is the highest prize awarded at the Cannes Film Festival. It was introduced in 1955 by the festival's organizing committee. Previously, from 1939 to 1954, the festival's highest prize was the Grand Prix du Fe ...

at the Cannes Film Festival

The Cannes Festival (; french: link=no, Festival de Cannes), until 2003 called the International Film Festival (') and known in English as the Cannes Film Festival, is an annual film festival held in Cannes, France, which previews new films o ...

in 1956 for ''The Silent World

''The Silent World'' (french: Le Monde du silence) is a 1956 French documentary film co-directed by Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle. One of the first films to use underwater cinematography to show the ocean depths in color, its title derives f ...

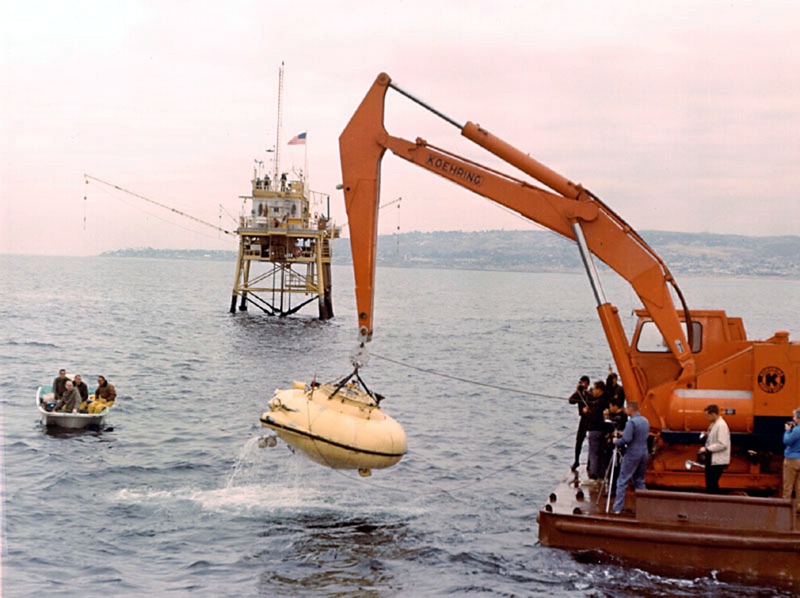

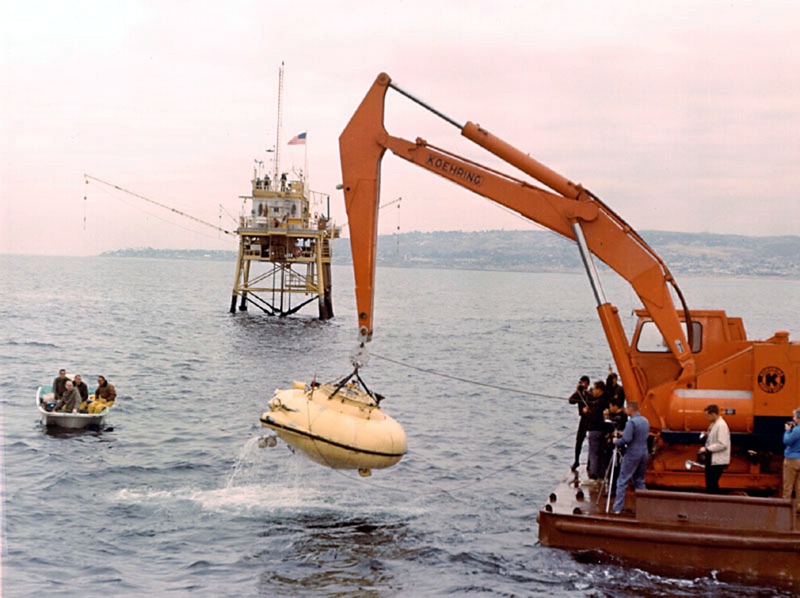

'' co-produced with Malle. In 1957, Cousteau took over as leader of the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco. Afterward, with the assistance of Jean Mollard, he made a "diving saucer" SP-350, an experimental underwater vehicle which could reach a depth of 350 meters. The successful experiment was quickly repeated in 1965 with two vehicles which reached 500 meters.

In 1957, he was elected as director of the Oceanographical Museum of Monaco. He directed Précontinent, about the experiments of diving in saturation (long-duration immersion, houses under the sea), and was admitted to the United States National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

.

He was involved in the creation of Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques

Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques (CMAS) is an international federation that represents underwater activities in underwater sport and underwater sciences, and oversees an international system of recreational snorkel and scu ...

and served as its inaugural president from 1959 to 1973.

Cousteau also took part in inventing the "SP-350 Denise Diving Saucer" in 1959 which was an invention best for exploring the ocean floor, as it allowed one to explore on solid ground.

In October 1960, a large amount of radioactive waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. Radioactive waste is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, rare-earth mining, and nuclear weapons r ...

was going to be discarded in the Mediterranean Sea by the Commissariat à l'énergie atomique

The French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission or CEA (French: Commissariat à l'énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives), is a French public government-funded research organisation in the areas of energy, defense and securit ...

(CEA). The CEA argued that the dumps were experimental in nature, and that French oceanographers such as Vsevelod Romanovsky had recommended it. Romanovsky and other French scientists, including Louis Fage Jean-Louis Fage (30 September 1883, in Limoges – 1964, in Dijon) was a French marine biologist and arachnologist.

A native of Limoges, he studied biology at the Sorbonne and in the laboratory at Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue. In 1906 he obtained his do ...

and Jacques Cousteau, repudiated the claim, saying that Romanovsky had in mind a much smaller amount. The CEA claimed that there was little circulation (and hence little need for concern) at the dump site between Nice and Corsica, but French public opinion sided with the oceanographers rather than with the CEA atomic energy scientists. The CEA chief, Francis Perrin, decided to postpone the dump. Cousteau organized a publicity campaign which in less than two weeks gained wide popular support. The train carrying the waste was stopped by women and children sitting on the railway tracks, and it was sent back to its origin.

In the 1960s, Cousteau was involved with a set of three projects to build underwater "villages"; the projects were named Precontinent I, Precontinent II and Precontinent III. Each ensuing project was aimed at increasing the depth at which people continuously lived under water, and were an attempt at creating an environment in which men could live and work on the sea floor. The projects are best known as Conshelf I (1962), Conshelf II (1963), and Conshelf III (1965). The names "Precontinent", and "Continental Shelf Station" (Conshelf) were used interchangeably by Cousteau.

A meeting with American television companies (

In the 1960s, Cousteau was involved with a set of three projects to build underwater "villages"; the projects were named Precontinent I, Precontinent II and Precontinent III. Each ensuing project was aimed at increasing the depth at which people continuously lived under water, and were an attempt at creating an environment in which men could live and work on the sea floor. The projects are best known as Conshelf I (1962), Conshelf II (1963), and Conshelf III (1965). The names "Precontinent", and "Continental Shelf Station" (Conshelf) were used interchangeably by Cousteau.

A meeting with American television companies (ABC

ABC are the first three letters of the Latin script known as the alphabet.

ABC or abc may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Broadcasting

* American Broadcasting Company, a commercial U.S. TV broadcaster

** Disney–ABC Television ...

, Métromédia, NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

) created the series ''The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau

''The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau'' is an American documentary television series about underwater marine life, directed by Alan Landsburg and hosted by French filmmaker, researcher, and marine explorer Jacques Cousteau. The first episod ...

'', with the character of the commander in the red bonnet inherited from standard diving dress

Standard diving dress, also known as hard-hat or copper hat equipment, deep sea diving suit or heavy gear, is a type of diving suit that was formerly used for all relatively deep underwater work that required more than breath-hold duration, which ...

intended to give the films a "personalized adventure" style. This documentary television series ran for ten years from 1966 to 1976. A second documentary series, ''The Cousteau Odyssey'', ran from 1977 to 1982 on public television stations.

In 1970, he wrote the book ''The Shark: Splendid Savage of the Sea'' with his son Philippe. In this book, Cousteau described the oceanic whitetip shark

The oceanic whitetip shark (''Carcharhinus longimanus''), also known as shipwreck shark, Brown Milbert's sand bar shark, brown shark, lesser white shark, nigano shark, oceanic white-tipped whaler, and silvertip shark, is a large pelagic requiem ...

as "the most dangerous of all sharks".

In December 1972, two years after the volcano's last eruption, The Cousteau Society was filming '' Voyage au bout du monde'' on Deception Island

Deception Island is an island in the South Shetland Islands close to the Antarctic Peninsula with a large and usually "safe" natural harbor, which is occasionally troubled by the underlying active volcano. This island is the caldera of an acti ...

, Antarctica, when Michel Laval, ''Calypso''s second in command, was struck and killed by a rotor of the helicopter that was ferrying between ''Calypso'' and the island.

In 1973, along with his two sons and Frederick Hyman, he created the Cousteau Society for the Protection of Ocean Life, Frederick Hyman being its first President.

In 1975, John Denver

Henry John Deutschendorf Jr. (December 31, 1943 – October 12, 1997), known professionally as John Denver, was an American singer-songwriter, guitarist, actor, activist, and humanitarian whose greatest commercial success was as a solo singe ...

released the tribute song " Calypso" on his album ''Windsong

''Windsong'' is the ninth studio album recorded by American singer-songwriter John Denver, which was released in September 1975. Denver's popularity was at its peak by this time.

The album contained the songs " I'm Sorry" and " Calypso," wh ...

'', and on the B-side of his hit song " I'm Sorry". "Calypso" became a hit on its own and was later considered the new A-side, reaching No. 2 on the charts.

In 1976, Cousteau located the wreck of HMHS ''Britannic''. He also found the wreck of the French 17th-century ship-of-the-line '' La Therese'' in coastal waters of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

.

In 1977, together with Peter Scott

Sir Peter Markham Scott, (14 September 1909 – 29 August 1989) was a British ornithologist, conservationist, painter, naval officer, broadcaster and sportsman. The only child of Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott, he took an interest i ...

, he received the UN International Environment prize.

On 28 June 1979, while the ''Calypso'' was on an expedition to Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, his second son Philippe, his preferred and designated successor and with whom he had co-produced all his films since 1969, died in a PBY Catalina

The Consolidated PBY Catalina is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft that was produced in the 1930s and 1940s. In Canadian service it was known as the Canso. It was one of the most widely used seaplanes of World War II. Catalinas served w ...

flying boat crash in the Tagus river near Lisbon. Cousteau was deeply affected. He called his eldest son, the architect Jean-Michel, to his side. This collaboration lasted 14 years.

1980–1990s

From 1980 to 1981, he was a regular on the animal reality show ''Those Amazing Animals

''That's Incredible!'' is an American reality television show that aired on the ABC television network from 1980 to 1984. In the tradition of ''You Asked for It'', '' Ripley's Believe It or Not!'' and ''Real People'', the show featured people ...

'', along with Burgess Meredith

Oliver Burgess Meredith (November 16, 1907 – September 9, 1997) was an American actor and filmmaker whose career encompassed theater, film, and television.

Active for more than six decades, Meredith has been called "a virtuosic actor" and "on ...

, Priscilla Presley

Priscilla Ann Presley ( Wagner, changed by adoption to Beaulieu; born May 24, 1945) is an American actress and businesswoman. She is the former wife of American singer Elvis Presley, as well as co-founder and former chairwoman of Elvis Presley ...

, and Jim Stafford

James Wayne Stafford (born January 16, 1944) is an American singer, songwriter, musician, and comedian. While prominent in the 1970s for his recordings " Spiders & Snakes", "Swamp Witch", "Under the Scotsman's Kilt", " My Girl Bill", and " Wildw ...

.

In 1980, Cousteau traveled to Canada to make two films on the

In 1980, Cousteau traveled to Canada to make two films on the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connectin ...

and the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

, ''Cries from the Deep

''Cries from the Deep'' (French: ''Les pièges de la mer'') is a 1982 documentary directed by Jacques Gagné about Jacques Cousteau's exploration of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

Filmed in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Québec, Canada, Halifax, ...

'' and ''St. Lawrence: Stairway to the Sea''.

In 1985, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

from U.S. President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

.

From 1986 to 1992, Cousteau released ''Rediscovery of the World''.

On 24 November 1988, he was elected to the Académie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

, chair 17, succeeding Jean Delay. His official reception under the cupola took place on 22 June 1989, the response to his speech of reception being given by Bertrand Poirot-Delpech. After his death, he was replaced by Érik Orsenna

Érik Orsenna is the pen-name of Érik Arnoult (born 22 March 1947) a French politician and novelist. After studying philosophy and political science at the Institut d'Études Politiques de Paris ("Sciences Po"), Orsenna specialized in economic ...

on 28 May 1998.

In June 1990, the composer Jean Michel Jarre

Jean-Michel André Jarre (; born 24 August 1948) is a French composer, performer and record producer. He is a pioneer in the electronic, ambient and new-age genres, and is known for organising outdoor spectacles featuring his music, accompanie ...

paid homage to the commander by entitling his new album ''Waiting for Cousteau

''En attendant Cousteau'' (English title: ''Waiting for Cousteau'') is the tenth studio album by French electronic musician and composer Jean-Michel Jarre, released on Disques Dreyfus, licensed to Polydor. The album was dedicated to Jacques-Yve ...

''. He also composed the music for Cousteau's documentary "Palawan

Palawan (), officially the Province of Palawan ( cyo, Probinsya i'ang Palawan; tl, Lalawigan ng Palawan), is an archipelagic province of the Philippines that is located in the region of Mimaropa. It is the largest province in the country in ...

, the last refuge".

On 2 December 1990, his wife, Simone Cousteau died of cancer.

In June 1991, in Paris, Jacques-Yves Cousteau remarried, to Francine Triplet, with whom he had (before this marriage) two children, Diane and Pierre-Yves. Francine Cousteau currently continues her husband's work as the head of the Cousteau Foundation and Cousteau Society. From that point, the relations between Jacques-Yves and his elder son, who is 8 years older than Francine, worsened.

In November 1991, Cousteau gave an interview to the ''UNESCO Courier

''The UNESCO Courier'' is the main magazine published by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). It has the largest and widest-ranging readership of all the journals published by the United Nations and its sp ...

'', in which he stated that he was in favour of human population control

Human population planning is the practice of intentionally controlling the growth rate of a human population. The practice, traditionally referred to as population control, had historically been implemented mainly with the goal of increasing po ...

and population decrease. Widely quoted on the Internet are these two paragraphs from the interview: "What should we do to eliminate suffering and disease? It's a wonderful idea but perhaps not altogether a beneficial one in the long run. If we try to implement it we may jeopardize the future of our species...It's terrible to have to say this. World population must be stabilized and to do that we must eliminate 350,000 people per day. This is so horrible to contemplate that we shouldn't even say it. But the general situation in which we are involved is lamentable".

In 1992, he was invited to Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, Brazil, for the United Nations' International Conference on Environment and Development, and then he became a regular consultant for the UN and the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Interna ...

.

In 1995, he sued his son, who was advertising "Cousteau Fiji Islands Resort", to prevent him from using the Cousteau name for business purposes in the United States.

On 11 January 1996, ''Calypso'' was accidentally rammed and sunk in the port of Singapore by a barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels ...

. The ''Calypso'' was refloated and towed home to France.

Religious views

Though he was not particularly a religious man, Cousteau believed that the teachings of the different major religions provide valuable ideals and thoughts to protect the environment. In a Chapter entitled "The Holy Scriptures and The Environment" in the posthumous work ''The Human, the Orchid, and the Octopus'', he is quoted as stating that "The glory of nature provides evidence that God exists".Opinion on recreational fishing

Cousteau said that just because fish are cold-blooded does not mean they do not feel pain, and that recreational fishermen only say so to reassure their conscience.Death and legacy

Jacques-Yves Cousteau died of a heart attack on 25 June 1997 in Paris, two weeks after his 87th birthday. He was buried in the family vault atSaint-André-de-Cubzac

Saint-André-de-Cubzac (; oc, Sent Andreus de Cubzac) is a commune in the Gironde department in Nouvelle-Aquitaine in south-western France.

Its inhabitants are called Cubzaguais.

Population

Notable residents

Jacques-Yves Cousteau is buried ...

, his birthplace. An homage was paid to him by the town by naming the street which runs out to the house of his birth "rue du Commandant Cousteau", where a commemorative plaque was placed.

Cousteau's legacy includes more than 120 television documentaries, more than 50 books, and an environmental protection foundation with 300,000 members.

Cousteau liked to call himself an "oceanographic technician". He was, in reality, a sophisticated showman, teacher, and lover of nature. His work permitted many people to explore the resources of the oceans.

His work also created a new kind of scientific communication, criticized at the time by some academics. The so-called " divulgationism", a simple way of sharing scientific concepts, was soon employed in other disciplines and became one of the most important characteristics of modern television broadcasting.

Ironically, Cousteau's most lasting legacy may be a negative one. His Oceanographic Museum in Monaco, and perhaps even he himself, has been identified as introducing the Caulerpa

''Caulerpa'' is a genus of seaweeds in the family Caulerpaceae (among the green algae). They are unusual because they consist of only one cell with many nuclei, making them among the biggest single cells in the world. A species in the Mediterran ...

"Killer Algae," which is destroying much of the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

's ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

.

The Cousteau Society and its French counterpart, l'Équipe Cousteau, both of which Jacques-Yves Cousteau founded, are still active today. The Society is currently attempting to turn the original '' Calypso'' into a museum and it is raising funds to build a successor vessel, the ''Calypso II''.

In his last years, after marrying again, Cousteau became involved in a legal battle with his son Jean-Michel

Jean-Michel is a French masculine given name. It may refer to :

* Jean-Michel Arnold, General Secretary of the Cinémathèque Française

* Jean-Michel Atlan (1913–1960), French artist

* Jean-Michel Aulas (born 1949), French businessman

* Jean-Mic ...

over Jean-Michel licensing the Cousteau name for a South Pacific resort, resulting in Jean-Michel Cousteau being ordered by the court not to encourage confusion between his for-profit business and his father's non-profit endeavours.

In 2007, the International Watch Company

IWC International Watch Co. AG, also known as IWC Schaffhausen, is a Swiss watch manufacturer located in Schaffhausen, Switzerland. Originally founded by American watchmaker Florentine Ariosto Jones in 1868, IWC has been a subsidiary of the Sw ...

introduced the IWC Aquatimer Chronograph "Cousteau Divers" Special Edition. The timepiece incorporated a sliver of wood from the interior of Cousteau's Calypso research vessel. Having developed the diver's watch, IWC offered support to The Cousteau Society. The proceeds from the timepieces' sales were partially donated to the non-profit organization involved in conservation of marine life and preservation of tropical coral reefs.

Fabien Cousteau

Fabien Cousteau (born 2 October 1967) is an aquanaut, ocean conservationist, and documentary filmmaker. As the first grandson of Jacques Cousteau, Fabien spent his early years aboard his grandfather's ships RV Calypso, Calypso and Alcyone (1985 ...

, the grandson of Jacques Cousteau, is in the process of constructing a community of ocean flooring analysis stations, called Proteus, off Curaçao at a depth of about 20 m in a marine-protected area. Aquanauts could reside and work in these underwater habitats. Front-end engineering has started in 2022 with the habitat put on the sea bottom in 2025.

Awards and honors

During his lifetime, Jacques-Yves Cousteau received these distinctions: * Cross of War 1939–1945 (1945) *National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society (NGS), headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest non-profit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, and ...

's Special Gold Medal in 1961

* Commander of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon, ...

(1972)

* Officer of the Order of Maritime Merit (1980)

* Grand Cross of the National Order of Merit (1985)

* U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

(1985)

* Induction into the Television Hall of Fame

The Television Academy Hall of Fame honors individuals who have made extraordinary contributions to U.S. television. The hall of fame was founded by former Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS) president John H. Mitchell (1921–1988). ...

(1987)

* Elected to the Académie Française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of secondary education, secondary or tertiary education, tertiary higher education, higher learning (and generally also research or honorary membershi ...

(1988)

* Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters

The ''Ordre des Arts et des Lettres'' (Order of Arts and Letters) is an order of France established on 2 May 1957 by the Minister of Culture. Its supplementary status to the was confirmed by President Charles de Gaulle in 1963. Its purpose is ...

* Honorary Companion of the Order of Australia

The Order of Australia is an honour that recognises Australian citizens and other persons for outstanding achievement and service. It was established on 14 February 1975 by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia, on the advice of the Australian Gove ...

(26 January 1990)

* Omicron Delta Kappa (1996)

Filmography

Legend

Bibliography

* ''The Silent World

''The Silent World'' (french: Le Monde du silence) is a 1956 French documentary film co-directed by Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle. One of the first films to use underwater cinematography to show the ocean depths in color, its title derives f ...

'' (1953, with Frédéric Dumas

Frédéric Dumas (14 January 1913 – 26 July 1991) was a French writer. He was part of a team of three, with Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Philippe Tailliez, who had a passion for diving, and developed the diving regulator with the aid of the enginee ...

)

* ''Captain Cousteaus Underwater Treasury'' (1959, with James Dugan)

* ''The Living Sea'' (1963, with James Dugan)

* ''World Without Sun'' (1965)

* ''The Undersea Discoveries of Jacques-Yves Cousteau'' (1970–1975, 8-volumes, with Philippe Diolé)

** ''The Shark: Splendid Savage of the Sea'' (1970)

** ''Diving for Sunken Treasure'' (1971)

** ''Life and Death in a Coral Sea'' (1971)

** ''The Whale: Mighty Monarch of the Sea'' (1972)

** ''Octopus and Squid: The Soft Intelligence'' (1973)

** ''Three Adventures: Galápagos, Titicaca, the Blue Holes'' (1973)

** ''Diving Companions: Sea Lion, Elephant Seal, Walrus'' (1974)

** ''Dolphins'' (1975)

* '' The Ocean World of Jacques Cousteau'' (1973–78, 21 volumes)

** ''Oasis in Space'' (vol 1)

** ''The Act of Life'' (vol 2)

** ''Quest for Food'' (vol 3)

** ''Window in the Sea'' (vol 4)

** ''The Art of Motion'' (vol 5)

** ''Attack and Defense'' (vol 6)

** ''Invisible Messages'' (vol 7)

** ''Instinct and Intelligence'' (vol 8)

** ''Pharaohs of the Sea'' (vol 9)

** ''Mammals in the Sea'' (vol 10)

** ''Provinces of the Sea'' (vol 11)

** ''Man Re-Enters Sea'' (vol 12)

** ''A Sea of Legends'' (vol 13)

** ''Adventure of Life'' (vol 14)

** ''Outer and Inner Space'' (vol 15)

** ''The Whitecaps'' (vol 16)

** ''Riches of the Sea'' (vol 17)

** ''Challenges of the Sea'' (vol 18)

** ''The Sea in Danger'' (vol 19)

** ''Guide to the Sea and Index'' (vol 20)

** ''Calypso'' (1978, vol 21)

* ''A Bill of Rights for Future Generations'' (1979)

* ''Life at the Bottom of the World'' (1980)

* ''The Cousteau United States Almanac of the Environment'' (1981, a.k.a. '' The Cousteau Almanac of the Environment: An Inventory of Life on a Water Planet'')

* ''Jacques Cousteau's Calypso'' (1983, with Alexis Sivirine)

* ''Marine Life of the Caribbean'' (1984, with James Cribb and Thomas H. Suchanek)

* ''Jacques Cousteau's Amazon Journey'' (1984, with Mose Richards)

* ''Jacques Cousteau: The Ocean World'' (1985)

* ''The Whale'' (1987, with Philippe Diolé)

* ''Jacques Cousteau: Whales'' (1988, with Yves Paccalet

Yves may refer to:

* Yves, Charente-Maritime, a commune of the Charente-Maritime department in France

* Yves (given name), including a list of people with the name

* Yves (single album), ''Yves'' (single album), a single album by Loona

* Yves (fil ...

)

* ''The Human, The Orchid and The Octopus'' (and Susan Schiefelbein, coauthor; Bloomsbury 2007)

Media portrayals

Jacques Cousteau has been portrayed in films: * The American comedy film ''The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou

''The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou'' is a 2004 American adventure comedy-drama film written by Wes Anderson and Noah Baumbach and directed by Anderson. It is Anderson's fourth feature-length film and was released in the United States on Decembe ...

'', directed by Wes Anderson

Wesley Wales Anderson (born May 1, 1969) is an American filmmaker. His films are known for their eccentricity and unique visual and narrative styles. They often contain themes of grief, loss of innocence, and dysfunctional families. Cited by ...

and first released in December 2004, portrays Steve Zissou, a fictional oceanographer strongly inspired by Jacques Cousteau.

* The French film ''The Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Iliad'', th ...

'', directed by Jérôme Salle

Jérôme Salle (born 1971) is a French film director and screenwriter.

Salle directed the films ''Anthony Zimmer'', the Belgian comic book adaptation '' Largo Winch'', and its sequel ''Largo Winch II''. His 2013 film '' Zulu'' was selected as th ...

and first released in October 2016, focuses on Cousteau's life, especially regarding his relation with his first wife, Simone Melchior

Simone Cousteau (née Melchior; 19 January 1919 – 1 December 1990) was a French explorer. She was the first woman scuba diver and aquanaut, and wife and business partner of undersea explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

Although never visible in the ...

, and his second son, Philippe Cousteau

Philippe Pierre Cousteau (30 December 1940 – 28 June 1979) was a French diver, sailor, pilot, photographer, author, director and cinematographer specializing in environmental issues, with a background in oceanography. He was the second son of ...

.

*Jacques Cousteau was featured in Epic Rap Battle of History's sixth season, and was portrayed by Peter Shukoff

Peter Alexis Shukoff (born August 15, 1979), best known as his stage name Nice Peter or Bluesocks, is an American musician and Internet personality. A self-described "Comic/Guitar Hero", he is best known for the comedy on his YouTube channel, Ni ...

.

See also

* '' Becoming Cousteau'', a 2021 full-length film biography * * * * * List of Legion of Honour recipients by name (C)References

Further reading

* ''Undersea Explorer: The Story of Captain Cousteau'' (1957) by James Dugan * ''Jacques Cousteau and the Undersea World'' (2000) by Roger King * ''Jacques-Yves Cousteau: His Story Under the Sea'' (2002) by John Bankston * ''Jacques Cousteau: A Life Under the Sea'' (2008) by Kathleen OlmsteadExternal links

The Cousteau Society

* *

Ocean Treasures Memorial Library

Ocean Treasures Memorial Library/Jacques-Yves Cousteau Memorial

Ocean Treasures Memorial Library/His Legacy

Ocean Treasures Memorial Library/Photos

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cousteau, Jacques-Yves French marine biologists 1910 births 1997 deaths 20th-century French biologists 20th-century explorers 20th-century photographers BAFTA fellows Collège Stanislas de Paris alumni Commandeurs of the Légion d'honneur

Jacques

Ancient and noble French family names, Jacques, Jacq, or James are believed to originate from the Middle Ages in the historic northwest Brittany region in France, and have since spread around the world over the centuries. To date, there are over ...

Directors of Best Documentary Feature Academy Award winners

Directors of Palme d'Or winners

Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

French documentary filmmakers

French explorers

20th-century French inventors

French military personnel of World War II

French Navy officers

French oceanographers

French photographers

French underwater divers

Grand Cross of the Ordre national du Mérite

History of scuba diving

Honorary Companions of the Order of Australia

Howard N. Potts Medal recipients

International Emmy Founders Award winners

Members of the Académie Française

Officers of the Ordre du Mérite Maritime

Sportspeople from Gironde

Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France)

Sierra Club awardees

Underwater photographers

20th-century French writers

20th-century French zoologists

Underwater filmmakers

Diving engineers