Isomerase on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Isomerases are a general class of

Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase type I (also known as IPP isomerase) is seen in

Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase type I (also known as IPP isomerase) is seen in

Superfamilies of single-pass transmembrane lyases

in

GoPubMed: Top authors, journals, places publishing on Isomerases

{{Portal bar, Biology, border=no

enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s that convert a molecule from one isomer

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formulae – that is, same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Isomerism is existence or possibility of isomers.

Iso ...

to another. Isomerases facilitate intramolecular rearrangements in which bonds are broken and formed. The general form of such a reaction is as follows:

A–B → B–A

There is only one substrate yielding one product. This product has the same molecular formula

In chemistry, a chemical formula is a way of presenting information about the chemical proportions of atoms that constitute a particular chemical compound or molecule, using chemical element symbols, numbers, and sometimes also other symbols, ...

as the substrate but differs in bond connectivity or spatial arrangement. Isomerases catalyze reactions across many biological processes, such as in glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvate (). The free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy molecules adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH ...

and carbohydrate metabolism

Carbohydrate metabolism is the whole of the biochemistry, biochemical processes responsible for the metabolic anabolism, formation, catabolism, breakdown, and interconversion of carbohydrates in life, living organisms.

Carbohydrates are central t ...

.

Isomerization

Isomerasescatalyze

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

changes within one molecule. They convert one isomer to another, meaning that the end product has the same molecular formula but a different physical structure. Isomer

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formulae – that is, same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Isomerism is existence or possibility of isomers.

Iso ...

s themselves exist in many varieties but can generally be classified as structural isomers or stereoisomers

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in ...

. Structural isomers have a different ordering of bonds and/or different bond connectivity from one another, as in the case of hexane

Hexane () is an organic compound, a straight-chain alkane with six carbon atoms and has the molecular formula C6H14.

It is a colorless liquid, odorless when pure, and with boiling points approximately . It is widely used as a cheap, relatively ...

and its four other isomeric forms ( 2-methylpentane, 3-methylpentane, 2,2-dimethylbutane, and 2,3-dimethylbutane).

Stereoisomers have the same ordering of individual bonds and the same connectivity but the three-dimensional arrangement of bonded atoms differ. For example, 2-butene exists in two isomeric forms: ''cis''-2-butene and ''trans''-2-butene. The sub-categories of isomerases containing racemases, epimerases and cis-trans isomers are examples of enzymes catalyzing the interconversion of stereoisomers. Intramolecular lyases, oxidoreductases and transferases catalyze the interconversion of structural isomers.

The prevalence of each isomer in nature depends in part on the isomerization energy, the difference in energy between isomers. Isomers close in energy can interconvert easily and are often seen in comparable proportions. The isomerization energy, for example, for converting from a stable ''cis'' isomer to the less stable ''trans'' isomer is greater than for the reverse reaction, explaining why in the absence of isomerases or an outside energy source such as ultraviolet radiation

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation i ...

a given ''cis'' isomer tends to be present in greater amounts than the ''trans'' isomer. Isomerases can increase the reaction rate

The reaction rate or rate of reaction is the speed at which a chemical reaction takes place, defined as proportional to the increase in the concentration of a product per unit time and to the decrease in the concentration of a reactant per unit ...

by lowering the isomerization energy.

Calculating isomerase kinetics

Kinetics ( grc, κίνησις, , kinesis, ''movement'' or ''to move'') may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Kinetics (physics), the study of motion and its causes

** Rigid body kinetics, the study of the motion of rigid bodies

* Chemical ki ...

from experimental data can be more difficult than for other enzymes because the use of product inhibition experiments is impractical. That is, isomerization is not an irreversible reaction

A reversible reaction is a reaction in which the conversion of reactants to products and the conversion of products to reactants occur simultaneously.

: \mathit aA + \mathit bB \mathit cC + \mathit dD

A and B can react to form C and D or, in the ...

since a reaction vessel will contain one substrate and one product so the typical simplified model for calculating reaction kinetics

Chemical kinetics, also known as reaction kinetics, is the branch of physical chemistry that is concerned with understanding the rates of chemical reactions. It is to be contrasted with chemical thermodynamics, which deals with the direction in w ...

does not hold. There are also practical difficulties in determining the rate-determining step

In chemical kinetics, the overall rate of a reaction is often approximately determined by the slowest step, known as the rate-determining step (RDS or RD-step or r/d step) or rate-limiting step. For a given reaction mechanism, the prediction of the ...

at high concentrations in a single isomerization. Instead, tracer perturbation can overcome these technical difficulties if there are two forms of the unbound enzyme. This technique uses isotope exchange to measure indirectly the interconversion of the free enzyme between its two forms. The radiolabeled substrate and product diffuse

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical p ...

in a time-dependent manner. When the system reaches equilibrium the addition of unlabeled substrate perturbs or unbalances it. As equilibrium is established again, the radiolabeled substrate and product are tracked to determine energetic information.

The earliest use of this technique elucidated the kinetics and mechanism

Mechanism may refer to:

* Mechanism (engineering), rigid bodies connected by joints in order to accomplish a desired force and/or motion transmission

*Mechanism (biology), explaining how a feature is created

*Mechanism (philosophy), a theory that ...

underlying the action of phosphoglucomutase

Phosphoglucomutase () is an enzyme that transfers a phosphate group on an α-D-glucose monomer from the 1 to the 6 position in the forward direction or the 6 to the 1 position in the reverse direction.

More precisely, it facilitates the interconve ...

, favoring the model of indirect transfer of phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phospho ...

with one intermediate and the direct transfer of glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

. This technique was then adopted to study the profile of proline racemase

In enzymology, a proline racemase () is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction

:L-proline \rightleftharpoons D-proline

Hence, this enzyme has two substrates, L- and D-proline, and two products, D- and L- proline.

This enzyme belongs ...

and its two states: the form which isomerizes L- proline and the other for D-proline. At high concentrations it was shown that the transition state

In chemistry, the transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest potential energy along this reaction coordinate. It is often marked wi ...

in this interconversion is rate-limiting and that these enzyme forms may differ just in the protonation

In chemistry, protonation (or hydronation) is the adding of a proton (or hydron, or hydrogen cation), (H+) to an atom, molecule, or ion, forming a conjugate acid. (The complementary process, when a proton is removed from a Brønsted–Lowry acid, ...

at the acid

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

ic and basic

BASIC (Beginners' All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) is a family of general-purpose, high-level programming languages designed for ease of use. The original version was created by John G. Kemeny and Thomas E. Kurtz at Dartmouth College ...

groups

A group is a number of persons or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

Groups of people

* Cultural group, a group whose members share the same cultural identity

* Ethnic group, a group whose members share the same ethnic ide ...

of the active site

In biology and biochemistry, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of amino acid residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate (binding site) a ...

.

Nomenclature

Generally, "the names of isomerases are formed as "''substrate'' isomerase" (for example, enoyl CoA isomerase), or as "''substrate'' ''type of isomerase''" (for example,phosphoglucomutase

Phosphoglucomutase () is an enzyme that transfers a phosphate group on an α-D-glucose monomer from the 1 to the 6 position in the forward direction or the 6 to the 1 position in the reverse direction.

More precisely, it facilitates the interconve ...

)."

Classification

Enzyme-catalyzed reactions each have a uniquely assigned classification number. Isomerase-catalyzed reactions have their own EC category: EC 5. Isomerases are further classified into six subclasses:Racemases, epimerases

This category (EC 5.1) includes (racemase Epimerases and racemases are isomerase enzymes that catalyze the inversion of stereochemistry in biological molecules.

Racemases catalyze the stereochemical inversion around the asymmetric carbon atom in a substrate having only one center of asymm ...

s) and epimerase Epimerases and racemases are isomerase enzymes that catalyze the inversion of stereochemistry in biological molecules.

Racemases catalyze the stereochemical inversion around the asymmetric carbon atom in a substrate having only one center of asymm ...

s). These isomerases invert stereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, involves the study of the relative spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation. The study of stereochemistry focuses on the relationships between stereois ...

at the target chiral carbon. Racemases act upon molecules with one chiral carbon for inversion of stereochemistry, whereas epimerases target molecules with multiple chiral carbons and act upon one of them. A molecule with only one chiral carbon has two enantiomer

In chemistry, an enantiomer ( /ɪˈnænti.əmər, ɛ-, -oʊ-/ ''ih-NAN-tee-ə-mər''; from Ancient Greek ἐνάντιος ''(enántios)'' 'opposite', and μέρος ''(méros)'' 'part') – also called optical isomer, antipode, or optical ant ...

ic forms, such as serine having the isoforms D-serine and L-serine differing only in the absolute configuration

Absolute configuration refers to the spatial arrangement of atoms within a chiral molecular entity (or group) and its resultant stereochemical description. Absolute configuration is typically relevant in organic molecules, where carbon is bonde ...

about the chiral carbon. A molecule with multiple chiral carbons has two forms at each chiral carbon. Isomerization at one chiral carbon of several yields epimer

In stereochemistry, an epimer is one of a pair of diastereomers. The two epimers have opposite configuration at only one stereogenic center out of at least two. All other stereogenic centers in the molecules are the same in each. Epimerization i ...

s, which differ from one another in absolute configuration at just one chiral carbon. For example, D-glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

and D-mannose

Mannose is a sugar monomer of the aldohexose series of carbohydrates. It is a C-2 epimer of glucose. Mannose is important in human metabolism, especially in the glycosylation of certain proteins. Several congenital disorders of glycosylation ...

differ in configuration at just one chiral carbon. This class is further broken down by the group the enzyme acts upon:

Cis-trans isomerases

This category (EC 5.2) includes enzymes that catalyze the isomerization of cis-trans isomers.Alkenes

In organic chemistry, an alkene is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon double bond.

Alkene is often used as synonym of olefin, that is, any hydrocarbon containing one or more double bonds.H. Stephen Stoker (2015): General, Organic, an ...

and cycloalkanes

In organic chemistry, the cycloalkanes (also called naphthenes, but distinct from naphthalene) are the monocyclic saturated hydrocarbons. In other words, a cycloalkane consists only of hydrogen and carbon atoms arranged in a structure containing ...

may have cis-trans stereoisomers. These isomers are not distinguished by absolute configuration

Absolute configuration refers to the spatial arrangement of atoms within a chiral molecular entity (or group) and its resultant stereochemical description. Absolute configuration is typically relevant in organic molecules, where carbon is bonde ...

but rather by the position of substituent groups relative to a plane of reference, as across a double bond or relative to a ring structure. ''Cis'' isomers have substituent groups on the same side and ''trans'' isomers have groups on opposite sides.

This category is not broken down any further. All entries presently include:

Intramolecular oxidoreductases

This category (EC 5.3) includes intramolecularoxidoreductase

In biochemistry, an oxidoreductase is an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of electrons from one molecule, the reductant, also called the electron donor, to another, the oxidant, also called the electron acceptor. This group of enzymes usually u ...

s. These isomerases catalyze the transfer of electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no kn ...

s from one part of the molecule to another. In other words, they catalyze the oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

of one part of the molecule and the concurrent reduction of another part. Sub-categories of this class are:

Intramolecular transferases

This category (EC 5.4) includes intramoleculartransferase

A transferase is any one of a class of enzymes that catalyse the transfer of specific functional groups (e.g. a methyl or glycosyl group) from one molecule (called the donor) to another (called the acceptor). They are involved in hundreds of ...

s ( mutases). These isomerases catalyze the transfer of functional group

In organic chemistry, a functional group is a substituent or moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions regardless of the rest ...

s from one part of a molecule to another. Phosphotransferases (EC 5.4.2) were categorized as transferases (EC 2.7.5) with regeneration of donors until 1983. This sub-class can be broken down according to the functional group the enzyme transfers:

Intramolecular lyases

This category (EC 5.5) includes intramolecular lyases. These enzymes catalyze "reactions in which a group can be regarded as eliminated from one part of a molecule, leaving a double bond, while remainingcovalently

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atom ...

attached to the molecule." Some of these catalyzed reactions involve the breaking of a ring structure.

This category is not broken down any further. All entries presently include:

Mechanisms of isomerases

Ring expansion and contraction via tautomers

A classic example of ring opening and contraction is the isomerization ofglucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

(an aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl grou ...

with a six-membered ring) to fructose

Fructose, or fruit sugar, is a Ketose, ketonic monosaccharide, simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galacto ...

(a ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is a functional group with the structure R–C(=O)–R', where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group –C(=O)– (which contains a carbon-oxygen double bo ...

with a five-membered ring). The conversion of D-glucose-6-phosphate to D-fructose-6-phosphate is catalyzed by glucose-6-phosphate isomerase

Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI), alternatively known as phosphoglucose isomerase/phosphoglucoisomerase (PGI) or phosphohexose isomerase (PHI), is an enzyme ( ) that in humans is encoded by the ''GPI'' gene on chromosome 19.

This gene enc ...

, an intramolecular oxidoreductase

In biochemistry, an oxidoreductase is an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of electrons from one molecule, the reductant, also called the electron donor, to another, the oxidant, also called the electron acceptor. This group of enzymes usually u ...

. The overall reaction involves the opening of the ring to form an aldose via acid/base catalysis and the subsequent formation of a cis-endiol intermediate. A ketose is then formed and the ring is closed again.

Glucose-6-phosphate first binds to the active site

In biology and biochemistry, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of amino acid residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate (binding site) a ...

of the isomerase. The isomerase opens the ring: its His388 residue protonates the oxygen on the glucose ring (and thereby breaking the O5-C1 bond) in conjunction with Lys518 deprotonating the C1 hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

oxygen. The ring opens to form a straight-chain aldose with an acidic C2 proton. The C3-C4 bond rotates and Glu357 (assisted by His388) depronates C2 to form a double bond between C1 and C2. A cis-endiol intermediate is created and the C1 oxygen is protonated by the catalytic residue, accompanied by the deprotonation of the endiol C2 oxygen. The straight-chain ketose

A ketose is a monosaccharide containing one ketone group per molecule. The simplest ketose is dihydroxyacetone, which has only three carbon atoms. It is the only ketose with no optical activity. All monosaccharide ketoses are reducing sugars, be ...

is formed. To close the fructose ring, the reverse of ring opening occurs and the ketose is protonated.

Epimerization

An example of epimerization is found in the Calvin cycle when D-ribulose-5-phosphate is converted into D-xylulose-5-phosphate by ribulose-phosphate 3-epimerase. The substrate and product differ only instereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, involves the study of the relative spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation. The study of stereochemistry focuses on the relationships between stereois ...

at the third carbon in the chain. The underlying mechanism involves the deprotonation of that third carbon to form a reactive enol

In organic chemistry, alkenols (shortened to enols) are a type of reactive structure or intermediate in organic chemistry that is represented as an alkene ( olefin) with a hydroxyl group attached to one end of the alkene double bond (). The t ...

ate intermediate. The enzyme's active site contains two Asp residues. After the substrate binds to the enzyme, the first Asp deprotonates the third carbon from one side of the molecule. This leaves a planar sp2-hybridized intermediate. The second Asp is located on the opposite side of the active side and it protonates the molecule, effectively adding a proton from the back side. These coupled steps invert stereochemistry at the third carbon.

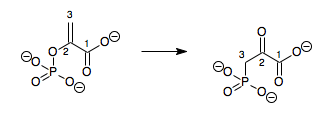

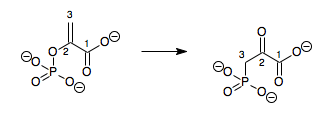

Intramolecular transfer

Chorismate mutase is an intramolecular transferase and it catalyzes the conversion ofchorismate

Chorismic acid, more commonly known as its anionic form chorismate, is an important biochemical intermediate in plants and microorganisms. It is a precursor for:

* The aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine

* Indole, indole ...

to prephenate

Prephenic acid, commonly also known by its ion, anionic form prephenate, is an intermediate in the biosynthesis of the aromatic amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine, as well as of a large number of secondary metabolites of the Shikimic acid, sh ...

, used as a precursor for L-tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a non-essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the G ...

and L-phenylalanine

Phenylalanine (symbol Phe or F) is an essential α-amino acid with the formula . It can be viewed as a benzyl group substituted for the methyl group of alanine, or a phenyl group in place of a terminal hydrogen of alanine. This essential amin ...

in some plants and bacteria. This reaction is a Claisen rearrangement

The Claisen rearrangement is a powerful carbon–carbon bond-forming chemical reaction discovered by Rainer Ludwig Claisen. The heating of an allyl vinyl ether will initiate a ,3sigmatropic rearrangement to give a γ,δ-unsaturated carbonyl, ...

that can proceed with or without the isomerase, though the rate increases 106 fold in the presence of chorismate mutase. The reaction goes through a chair

A chair is a type of seat, typically designed for one person and consisting of one or more legs, a flat or slightly angled seat and a back-rest. They may be made of wood, metal, or synthetic materials, and may be padded or upholstered in vario ...

transition state

In chemistry, the transition state of a chemical reaction is a particular configuration along the reaction coordinate. It is defined as the state corresponding to the highest potential energy along this reaction coordinate. It is often marked wi ...

with the substrate in a trans-diaxial position. Experimental evidence indicates that the isomerase selectively binds the chair transition state, though the exact mechanism of catalysis

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

is not known. It is thought that this binding stabilizes the transition state through electrostatic effects, accounting for the dramatic increase in the reaction rate in the presence of the mutase or upon addition of a specifically-placed cation in the active site.

Intramolecular oxidoreduction

Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase type I (also known as IPP isomerase) is seen in

Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase type I (also known as IPP isomerase) is seen in cholesterol

Cholesterol is any of a class of certain organic molecules called lipids. It is a sterol (or modified steroid), a type of lipid. Cholesterol is biosynthesized by all animal cells and is an essential structural component of animal cell mem ...

synthesis and in particular it catalyzes the conversion of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) to dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP). In this isomerization reaction a stable carbon-carbon double bond is rearranged top create a highly electrophilic

In chemistry, an electrophile is a chemical species that forms bonds with nucleophiles by accepting an electron pair. Because electrophiles accept electrons, they are Lewis acids. Most electrophiles are positively charged, have an atom that carri ...

allylic isomer. IPP isomerase catalyzes this reaction by the stereoselective

In chemistry, stereoselectivity is the property of a chemical reaction in which a single reactant forms an unequal mixture of stereoisomers during a non-stereospecific creation of a new stereocenter or during a non-stereospecific transformation of ...

antarafacial Antarafacial ( Woodward-Hoffmann symbol a) and suprafacial (s) are two topological concepts in organic chemistry describing the relationship between two simultaneous chemical bond making and/or bond breaking processes in or around a reaction cent ...

transposition of a single proton. The double bond

In chemistry, a double bond is a covalent bond between two atoms involving four bonding electrons as opposed to two in a single bond. Double bonds occur most commonly between two carbon atoms, for example in alkenes. Many double bonds exist betwee ...

is protonated at C4 to form a tertiary carbocation

A carbocation is an ion with a positively charged carbon atom. Among the simplest examples are the methenium , methanium and vinyl cations. Occasionally, carbocations that bear more than one positively charged carbon atom are also encountere ...

intermediate at C3. The adjacent carbon, C2, is deprotonated from the opposite face to yield a double bond. In effect, the double bond is shifted over.

The role of isomerase in human disease

Isomerase plays a role in human disease. Deficiencies of this enzyme can cause disorders in humans.Phosphohexose isomerase deficiency

Phosphohexose Isomerase Deficiency (PHI) is also known as phosphoglucose isomerase deficiency or Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase deficiency, and is a hereditary enzyme deficiency. PHI is the second most frequent erthoenzyopathy inglycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvate (). The free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy molecules adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH ...

besides pyruvate kinase deficiency

Pyruvate kinase deficiency is an inherited metabolic disorder of the enzyme pyruvate kinase which affects the survival of red blood cells. Both autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance have been observed with the disorder; classically, and ...

, and is associated with non-spherocytic haemolytic anaemia of variable severity. This disease is centered on the glucose-6-phosphate protein. This protein can be found in the secretion of some cancer cells. PHI is the result of a dimeric enzyme that catalyses the reversible interconversion of fructose-6-phosphate and gluose-6-phosphate.

PHI is a very rare disease with only 50 cases reported in literature to date.

Diagnosis is made on the basis of the clinical picture in association with biochemical studies revealing erythrocyte GPI deficiency (between 7 and 60% of normal) and identification of a mutation in the GPI gene by molecular analysis.

The deficiency of phosphohexose isomerase can lead to a condition referred to as hemolytic syndrome. As in humans, the hemolytic syndrome, which is characterized by a diminished erythrocyte number, lower hematocrit, lower hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

, higher number of reticulocytes and plasma bilirubin concentration, as well as increased liver- and spleen-somatic indices, was exclusively manifested in homozygous mutants.

Triosephosphate isomerase deficiency

The disease referred to as triosephosphate isomerase deficiency (TPI), is a severe autosomal recessive inherited multisystem disorder of glycolytic metabolism. It is characterized by hemolytic anemia and neurodegeneration, and is caused by anaerobic metabolic dysfunction. This dysfunction results from a missense mutation that effects the encoded TPI protein. The most common mutation is the substitution of gene, Glu104Asp, which produces the most severephenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

, and is responsible for approximately 80% of clinical TPI deficiency.

TPI deficiency is very rare with less than 50 cases reported in literature. Being an autosomal recessive inherited disease, TPI deficiency has a 25% recurrence risk in the case of heterozygous parents. It is a congenital disease that most often occurs with hemolytic anemia and manifests with jaundice. Most patients with TPI for Glu104Asp mutation or heterozygous for a TPI null allele and Glu104Asp have a life expectancy of infancy to early childhood. TPI patients with other mutations generally show longer life expectancy. To date, there are only two cases of individuals with TPI living beyond the age of 6. These cases involve two brothers from Hungary, one who did not develop neurological symptoms until the age of 12, and the older brother who has no neurological symptoms and suffers from anemia only.

Individuals with TPI show obvious symptoms after 6–24 months of age. These symptoms include: dystonia, tremor, dyskinesia, pyramidal tract signs, cardiomyopathy and spinal motor neuron involvement. Patients also show frequent respiratory system bacterial infections.

TPI is detected through deficiency of enzymatic activity and the build-up of dihyroxyacetone phosphate(DHAP), which is a toxic substrate, in erythrocytes. This can be detected through physical examination and a series of lab work. In detection, there is generally myopathic changes seen in muscles and chronic axonal neuropathy found in the nerves. Diagnosis of TPI can be confirmed through molecular genetics. Chorionic villus DNA analysis or analysis of fetal red cells can be used to detect TPI in antenatal diagnosis.

Treatment for TPI is not specific, but varies according to different cases. Because of the range of symptoms TPI causes, a team of specialist may be needed to provide treatment to a single individual. That team of specialists would consists of pediatricians, cardiologists, neurologists, and other healthcare professionals, that can develop a comprehensive plan of action.

Supportive measures such as red cell transfusions in cases of severe anaemia can be taken to treat TPI as well. In some cases, spleen

removal (splenectomy) may improve the anaemia. There is no treatment to prevent progressive

neurological impairment of any other non-haematological clinical manifestation of the diseases.

Industrial applications

By far the most common use of isomerases in industrial applications is insugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

manufacturing. Glucose isomerase (also known as xylose isomerase

In enzymology, a xylose isomerase () is an enzyme that catalyzes the interconversion of

D-xylose and D-xylulose. This enzyme belongs to the family of isomerases, specifically those intramolecular oxidoreductases interconverting aldoses and ket ...

) catalyzes the conversion of D-xylose

Xylose ( grc, ξύλον, , "wood") is a sugar first isolated from wood, and named for it. Xylose is classified as a monosaccharide of the aldopentose type, which means that it contains five carbon atoms and includes an aldehyde functional gro ...

and D-glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

to D-xylulose

Xylulose is a ketopentose, a monosaccharide containing five carbon atoms, and including a ketone functional group. It has the chemical formula . In nature, it occurs in both the L- and D-enantiomers. 1-Deoxyxylulose is a precursor to terpenes vi ...

and D-fructose

Fructose, or fruit sugar, is a Ketose, ketonic monosaccharide, simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galacto ...

. Like most sugar isomerases, glucose isomerase catalyzes the interconversion of aldoses and ketose

A ketose is a monosaccharide containing one ketone group per molecule. The simplest ketose is dihydroxyacetone, which has only three carbon atoms. It is the only ketose with no optical activity. All monosaccharide ketoses are reducing sugars, be ...

s.

The conversion of glucose to fructose is a key component of high-fructose corn syrup

High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), also known as glucose–fructose, isoglucose and glucose–fructose syrup, is a sweetener made from corn starch. As in the production of conventional corn syrup, the starch is broken down into glucose by enzy ...

production. Isomerization

In chemistry, isomerization or isomerisation is the process in which a molecule, polyatomic ion or molecular fragment is transformed into an isomer with a different chemical structure. Enolization is an example of isomerization, as is tautomeriz ...

is more specific than older chemical methods of fructose production, resulting in a higher yield of fructose and no side products. The fructose produced from this isomerization reaction is purer with no residual flavors from contaminants

Contamination is the presence of a constituent, impurity, or some other undesirable element that spoils, corrupts, infects, makes unfit, or makes inferior a material, physical body, natural environment, workplace, etc.

Types of contamination

...

. High-fructose corn syrup is preferred by many confectionery and soda manufacturers because of the high sweetening power of fructose (twice that of sucrose), its relatively low cost and its inability to crystallize. Fructose is also used as a sweetener for use by diabetics

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level (hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased a ...

. Major issues of the use of glucose isomerase involve its inactivation at higher temperatures and the requirement for a high pH (between 7.0 and 9.0) in the reaction environment. Moderately high temperatures, above 70 °C, increase the yield of fructose by at least half in the isomerization step. The enzyme requires a divalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with other atoms when it forms chemical compounds or molecules.

Description

The combining capacity, or affinity of an ...

cation

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

such as Co2+ and Mg2+ for peak activity, an additional cost to manufacturers. Glucose isomerase also has a much higher affinity for xylose than for glucose, necessitating a carefully controlled environment.

The isomerization of xylose to xylulose has its own commercial applications as interest in biofuel

Biofuel is a fuel that is produced over a short time span from biomass, rather than by the very slow natural processes involved in the formation of fossil fuels, such as oil. According to the United States Energy Information Administration (E ...

s has increased. This reaction is often seen naturally in bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

that feed on decaying plant matter. Its most common industrial use is in the production of ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl ...

, achieved by the fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food ...

of xylulose

Xylulose is a ketopentose, a monosaccharide containing five carbon atoms, and including a ketone functional group. It has the chemical formula . In nature, it occurs in both the L- and D-enantiomers. 1-Deoxyxylulose is a precursor to terpenes vi ...

. The use of hemicellulose

A hemicellulose (also known as polyose) is one of a number of heteropolymers (matrix polysaccharides), such as arabinoxylans, present along with cellulose in almost all terrestrial plant cell walls.Scheller HV, Ulvskov Hemicelluloses.// Annu Rev ...

as source material is very common. Hemicellulose contains xylan

Xylan (; ) ( CAS number: 9014-63-5) is a type of hemicellulose, a polysaccharide consisting mainly of xylose residues. It is found in plants, in the secondary cell walls of dicots and all cell walls of grasses. Xylan is the third most abundan ...

, which itself is composed of xylose

Xylose ( grc, ξύλον, , "wood") is a sugar first isolated from wood, and named for it. Xylose is classified as a monosaccharide of the aldopentose type, which means that it contains five carbon atoms and includes an aldehyde functional gro ...

in β(1,4) linkages. The use of glucose isomerase very efficiently converts xylose to xylulose, which can then be acted upon by fermenting yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are estimated to constitut ...

. Overall, extensive research in genetic engineering has been invested into optimizing glucose isomerase and facilitating its recovery from industrial applications for re-use.

Glucose isomerase is able to catalyze the isomerization of a range of other sugars, including D-ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally-occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this compo ...

, D-allose

Allose is an aldohexose sugar. It is a rare monosaccharide that occurs as a 6-O-cinnamyl glycoside in the leaves of the African shrub ''Protea rubropilosa''. Extracts from the fresh-water alga ''Ochromas malhamensis'' contain this sugar but of u ...

and L-arabinose

Arabinose is an aldopentose – a monosaccharide containing five carbon atoms, and including an aldehyde (CHO) functional group.

For biosynthetic reasons, most saccharides are almost always more abundant in nature as the "D"-form, or structurally ...

. The most efficient substrates are those similar to glucose and xylose, having equatorial Equatorial may refer to something related to:

*Earth's equator

**the tropics, the Earth's equatorial region

**tropical climate

*the Celestial equator

** equatorial orbit

**equatorial coordinate system

** equatorial mount, of telescopes

* equatorial ...

hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

groups at the third and fourth carbons. The current model for the mechanism of glucose isomerase is that of a hydride shift

A sigmatropic reaction in organic chemistry is a pericyclic reaction wherein the net result is one σ-bond is changed to another σ-bond in an uncatalyzed intramolecular reaction. The name ''sigmatropic'' is the result of a compounding of the lon ...

based on X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

and isotope exchange studies.

Membrane-associated isomerases

Some isomerases associate withbiological membranes

A biological membrane, biomembrane or cell membrane is a selectively permeable membrane that separates the interior of a cell from the external environment or creates intracellular compartments by serving as a boundary between one part of the c ...

as peripheral membrane protein

Peripheral membrane proteins, or extrinsic membrane proteins, are membrane proteins that adhere only temporarily to the biological membrane with which they are associated. These proteins attach to integral membrane proteins, or penetrate the perip ...

s or anchored through a single transmembrane helix

A transmembrane domain (TMD) is a membrane-spanning protein domain. TMDs generally adopt an alpha helix topological conformation, although some TMDs such as those in porins can adopt a different conformation. Because the interior of the lipid bi ...

,in

Membranome database

Membranome database provides structural and functional information about more than 6000 single-pass (bitopic) transmembrane proteins from ''Homo sapiens'', ''Arabidopsis thaliana'', ''Dictyostelium discoideum'', ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'', '' ...

for example isomerases with the thioredoxin domain, and certain prolyl isomerase

Prolyl isomerase (also known as peptidylprolyl isomerase or PPIase) is an enzyme () found in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes that interconverts the ''cis'' and ''trans'' isomers of peptide bonds with the amino acid proline. Proline has an ...

s.

References

External links

GoPubMed: Top authors, journals, places publishing on Isomerases

{{Portal bar, Biology, border=no