History of Sicily on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Sicily has been influenced by numerous ethnic groups. It has seen

The history of Sicily has been influenced by numerous ethnic groups. It has seen

The

The

From the 11th century BC,

From the 11th century BC,

Sicily began to be colonised by Greeks in the 8th century BC. Initially, this was restricted to the eastern and southern parts of the island. The most important colony was established at

Sicily began to be colonised by Greeks in the 8th century BC. Initially, this was restricted to the eastern and southern parts of the island. The most important colony was established at

The constant warfare between Carthage and the Greek city-states eventually opened the door to an emerging third power. In the 3rd century BC, the Messanan Crisis motivated the intervention of the

The constant warfare between Carthage and the Greek city-states eventually opened the door to an emerging third power. In the 3rd century BC, the Messanan Crisis motivated the intervention of the

For the next 600 years, Sicily was a

For the next 600 years, Sicily was a

The Gothic War took place between the Ostrogoths and the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the

The Gothic War took place between the Ostrogoths and the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the  From the late 7th century, Sicily joined with

From the late 7th century, Sicily joined with

By the 11th century, mainland southern Italian powers were hiring ferocious Norman mercenaries, who were Christian descendants of the

By the 11th century, mainland southern Italian powers were hiring ferocious Norman mercenaries, who were Christian descendants of the

The most significant changes that the Normans were to bring to Sicily were in the areas of religion, language and population. Almost from the moment that Roger I controlled much of the island, immigration was encouraged from

The most significant changes that the Normans were to bring to Sicily were in the areas of religion, language and population. Almost from the moment that Roger I controlled much of the island, immigration was encouraged from

Tancred died in 1194, just as Henry VI and Constance were travelling down the Italian peninsula to claim their crown. Henry rode into Palermo at the head of a large army unopposed and thus ended the Siculo-Norman Hauteville dynasty, replaced by the south

Tancred died in 1194, just as Henry VI and Constance were travelling down the Italian peninsula to claim their crown. Henry rode into Palermo at the head of a large army unopposed and thus ended the Siculo-Norman Hauteville dynasty, replaced by the south

Throughout Frederick's reign, there had been substantial antagonism between the Kingdom and the Papacy, which was part of the wider Guelph Ghibelline conflict. This antagonism was transferred to the Hohenstaufen house, and ultimately against Manfred.

In 1266,

Throughout Frederick's reign, there had been substantial antagonism between the Kingdom and the Papacy, which was part of the wider Guelph Ghibelline conflict. This antagonism was transferred to the Hohenstaufen house, and ultimately against Manfred.

In 1266,

With the union of the crowns of Castile and Aragon in 1479, Sicily was ruled directly by the kings of

With the union of the crowns of Castile and Aragon in 1479, Sicily was ruled directly by the kings of

The Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily were officially merged in 1816 by Ferdinand I to form the

The Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily were officially merged in 1816 by Ferdinand I to form the

Sicily was merged with

Sicily was merged with

The Sicilian economy did not adapt easily to unification, and in particular competition by Northern industry made attempts at industrialization in the South almost impossible. While the masses suffered by the introduction of new forms of taxation and, especially, by the new Kingdom's extensive military conscription, the Sicilian economy suffered, leading to an unprecedented wave of emigration.

The reluctance of Sicilian men to allow women to take paid work meant that women usually remained at home, their seclusion often increased due to the restrictions of mourning. Despite such restrictions, women carried out a variety of important roles in nourishing their families, selecting wives for their sons, and helping their husbands in the field.

In in the years between 1889 and 1894, there were labour agitations, through the radical left-wing, called ''

The Sicilian economy did not adapt easily to unification, and in particular competition by Northern industry made attempts at industrialization in the South almost impossible. While the masses suffered by the introduction of new forms of taxation and, especially, by the new Kingdom's extensive military conscription, the Sicilian economy suffered, leading to an unprecedented wave of emigration.

The reluctance of Sicilian men to allow women to take paid work meant that women usually remained at home, their seclusion often increased due to the restrictions of mourning. Despite such restrictions, women carried out a variety of important roles in nourishing their families, selecting wives for their sons, and helping their husbands in the field.

In in the years between 1889 and 1894, there were labour agitations, through the radical left-wing, called ''

online

* * Dummett, Jeremy. ''Sicily: Island of Beauty and Conflict'' (Bloomsbury, 2020). * Epstein, S. R. "Cities, Regions and the Late Medieval Crisis: Sicily and Tuscany Compared," ''Past & Present,'' Feb 1991, Issue 130, pp 3–50, advanced

Island for Itself: Economic Development and Social Change in Late Medieval Sicily

' (1992). * Finley, M. I. and Denis Mack Smith. ''History of Sicily (3 Vols. 1961) ** Finley, M. I., Denis Mack Smith and Christopher Duggan, '' A History of Sicily'' (1987

abridged edition online

* * Gabaccia, Donna R. "Migration and Peasant Militance: Western Sicily, 1880-1910," ''Social Science History,'' Spring 1984, Vol. 8 Issue 1, pp 67–8

in JSTOR

* Gabaccia, Donna. ''Militants & Migrants: Rural Sicilians Become American Workers'' (1988) 239p; covers 1860 to 20th century * Granara, William. ''Narrating Muslim Sicily: War and Peace in the Medieval Mediterranean World'' (Bloomsbury, 2019). * Harpster, Matthew. "Sicily: A Frontier in the Centre of the Sea?." ''Al-Masāq'' 31.2 (2019): 158-170

online

* Jäckh, Theresa, and Mona Kirsch, eds. ''Urban dynamics and transcultural communication in medieval Sicily'' (Wilhelm Fink, 2017). * Jonasch, Melanie, ed. ''The Fight for Greek Sicily: Society, Politics, and Landscape'' (Oxbow Books, 2020). * Kantorowicz, Ernst. ''Frederick the Second'', 1194–1250'' (Frederick Ungar, 1957). * Denis Mack Smith, ''A History of Sicily (Medieval Sicily: 800-1713; Modern Sicily: After 1713, 2 voll.)'', Chatto & Windus, 1968 * Leighton, Robert, ''Pantalica in the Sicilian Late Bronze and Iron Ages. Excavations of the rock-cut chamber tombs by Paolo Orsi from 1895 to 1910'' (Oxbow, Oxford and Philadelphia, 2019). * Leighton, Robert, ''Sicily before History: An Archaeological Survey from the Palaeolithic to the Iron Age'' (Duckworth/Bloomsbury, London; & Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 1999) * Mallette, Karla. ''The Kingdom of Sicily, 1100-1250: A Literary History'' (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2011). * Matthew, Donald. ''The Norman Kingdom of Sicily'' (2008

excerpt

* Romolo Menighetti, Franco Nicastro, ''History of Autonomous Sicily'', Legas, Mineola, Usa, 2001 * Militello, Paolo. "The Historiography on Early Modern Age Sicily Between the 20th and 21st Centuries." ''Mediterranea-ricerche storiche'' 36 (2016) 101–11

online

* Newark, Tim. "Pact with the Devil?" ''History Today'' (April 2007), Vol. 57 Issue 4, pp32–38' US deals with Mafia 1942-1943. * Norwich, John Julius. ''The Normans in Sicily'', (1992) * Pfuntner, Laura. ''Urbanism and empire in Roman Sicily'' (U of Texas Press, 2019). * Piccolo, Salvatore. ''Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily'', (2013). Thornham/Norfolk: Brazen Head Publishing, . * Powell, James M. ''The Crusades, the Kingdom of Sicily, and the Mediterranean'' (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company. (2007). 300pp. * Ramm, Agatha. "The Risorgimento in Sicily: Recent Literature," ''English Historical Review'' (1972) 87#345 pp. 795–81

in JSTOR

* Reeder, Linda.

Widows in White: Migration and the Transformation of Rural Italian Women, Sicily, 1880-1920

'. (2003), 322pp * Riall, Lucy. ''Sicily and the Unification of Italy: Liberal Policy & Local Power, 1859-1866'' (1998), 252pp * Runciman, Steven. ''The Sicilian Vespers'' (1958

online

* Schneider, Jane. ''Culture and Political Economy in Western Sicily'' (1976) * Smith, Denis Mack. ''Medieval Sicily, 800–1713'' (1968). * Takayama, Hiroshi. ''Sicily and the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages'' (2019

excerpts

* * Williams, Isobel. ''Allies and Italians under Occupation: Sicily and Southern Italy, 1943-45'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013)

online review

Livius.org: History of Sicily

Salvatore Piccolo: ''Bronze Age Sicily'', World History Encyclopedia (2018)

Salvatore Piccolo: ''The Dolmens of Sicily'', World History Encyclopedia (2017)

Salvatore Piccolo: ''Gela'', World History Encyclopedia (2017)

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Sicily

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

controlled by external powers – Phoenician and Carthaginian, Greek, Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

, Vandal and Ostrogoth

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who ...

, Byzantine Greek

Medieval Greek (also known as Middle Greek, Byzantine Greek, or Romaic) is the stage of the Greek language between the end of classical antiquity in the 5th–6th centuries and the end of the Middle Ages, conventionally dated to the Ottoman c ...

, Aghlabid, Fatimid, Kalbid

The Kalbids () were a Muslim Arab dynasty in the Emirate of Sicily, which ruled from 948 to 1053. They were formally appointed by the Fatimids, but gained, progressively, ''de facto'' autonomous rule.

History

In 827, in the midst of internal By ...

, Norman, Aragonese and Spanish – but also experiencing important periods of independence, as under the indigenous Sicanians

The Sicani (Ancient Greek Σῐκᾱνοί ''Sikānoí'') or Sicanians were one of three ancient peoples of Sicily present at the time of Phoenician and Greek colonization. The Sicani dwelt east of the Elymians and west of the Sicels, having, ...

, Elymians and Sicels

The Sicels (; la, Siculi; grc, Σικελοί ''Sikeloi'') were an Italic tribe who inhabited eastern Sicily during the Iron Age. Their neighbours to the west were the Sicani. The Sicels gave Sicily the name it has held since antiquity, b ...

, and later as the Emirate of Sicily

The Emirate of Sicily ( ar, إِمَارَة صِقِلِّيَة, ʾImārat Ṣiqilliya) was an Islamic kingdom that ruled the island of Sicily from 831 to 1091. Its capital was Palermo (Arabic: ''Balarm''), which during this period became ...

, County of Sicily, and Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

. The Kingdom was founded in 1130 by Roger II, belonging to the Siculo-Norman family of Hauteville. During this period, Sicily was prosperous and politically powerful, becoming one of the wealthiest states in all of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. As a result of the dynastic succession, then, the Kingdom passed into the hands of the Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynas ...

. At the end of the 13th century, with the War of the Sicilian Vespers between the crowns of Anjou Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

*County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

**Duke ...

and Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

, the island passed to the latter. In the following centuries the Kingdom entered into the personal union with the Spaniard

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance ethnic group native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex history, including a number of different languages, both ...

and Bourbon crowns, while preserving effective independence until 1816. Sicily was merged with the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

in 1861.

Although today an Autonomous Region

An autonomous administrative division (also referred to as an autonomous area, entity, unit, region, subdivision, or territory) is a subnational administrative division or internal territory of a sovereign state that has a degree of autonomy� ...

, with special statute, of the Republic of Italy, it has its own distinct culture.

Sicily is both the largest region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics ( physical geography), human impact characteristics ( human geography), and the interaction of humanity an ...

of the modern state of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. Its central location and natural resources ensured that it has been considered a crucial strategic location due in large part to its importance for Mediterranean trade routes. Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

and al-Idrisi described respectively Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

and Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for its ...

as the greatest and most beautiful cities of the Hellenic World

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

and of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

.

Prehistory

The

The indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

of Sicily, long absorbed into the population, were tribes known to ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

writers as the Elymians, the Sicani and the Siculi or Sicels

The Sicels (; la, Siculi; grc, Σικελοί ''Sikeloi'') were an Italic tribe who inhabited eastern Sicily during the Iron Age. Their neighbours to the west were the Sicani. The Sicels gave Sicily the name it has held since antiquity, b ...

(from whom the island derives its name). Of these, the last was the latest to arrive and was related to other Italic peoples

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

The Italic peoples are descended from the Indo-European speaking peoples who inhabited Italy from at lea ...

of southern Italy, such as the ''Italoi'' of Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, the Oenotrians

The Oenotrians (Οἴνωτρες, meaning "tribe led by Oenotrus" or "people from the land of vines - Οἰνωτρία") were an ancient Italic people who inhabited a territory in Southern Italy from Paestum to southern Calabria. By the sixth ...

, Chones, and Leuterni (or Leutarni), the Opicans, and the Ausones

"Ausones" (; ), the original Greek form for the Latin "Aurunci", was a name applied by Greek writers to describe various Italic peoples inhabiting the southern and central regions of Italy. The term was used, specifically, to denote the partic ...

. It has been proposed that the Sicani were originally an Iberian tribe. The Elymi, too, may have distant origins from outside Italy, in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

area. The recent discoveries of dolmen

A dolmen () or portal tomb is a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the early Neolithic (40003000 BCE) and were some ...

s dating to the second half of the third millennium BC, provide new insights to the composite cultural panorama of prehistoric Sicily.

The late prehistory of Sicily was complex and involved interactions between multiple ethnic groups. However, the impact of two influences remains clear: the Europeans coming from the north-west – for example, the peoples of Bell Beaker culture

The Bell Beaker culture, also known as the Bell Beaker complex or Bell Beaker phenomenon, is an archaeological culture named after the inverted-bell beaker drinking vessel used at the very beginning of the European Bronze Age. Arising from ar ...

(bearers of the dolmens culture, recently discovered in this island and dating back to the neolithic Bronze Age), and that from the eastern Mediterranean. Complex urban settlements become increasingly evident from around 1300 BC.

The Phoenicians

Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

begin to settle in western Sicily, having already started colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

on the nearby parts of North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

. Within a century, we find major Phoenician settlements at Soloeis (Solunto), present day Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for its ...

and Motya (an island near present-day Marsala

Marsala (, local ; la, Lilybaeum) is an Italian town located in the Province of Trapani in the westernmost part of Sicily. Marsala is the most populated town in its province and the fifth in Sicily.

The town is famous for the docking of Gius ...

). Others included Drepana

Drepana ( grc, Δρέπανα) was an Elymian, Carthaginian, and Roman port in antiquity on the western coast of Sicily. It was the site of a crushing Roman defeat by the Carthaginians in 249BC. It eventually developed into the modern Italian ...

(Trapani) and Mazara del Vallo.

As Phoenician Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

later grew in power, these settlements sometimes came into conflict with them, as at Motya, and eventually came under Carthage's direct control.

The Phoenicians integrated with the local Elymi

The Elymians ( grc-gre, Ἔλυμοι, ''Élymoi''; Latin: ''Elymi'') were an ancient tribal people who inhabited the western part of Sicily during the Bronze Age and Classical antiquity.

Origins

According to Hellanicus of Lesbos, the Elymians ...

an population as shown in archaeology as a distinctive “West Phoenician cultural identity”.

Classical Age

Greek period

Sicily began to be colonised by Greeks in the 8th century BC. Initially, this was restricted to the eastern and southern parts of the island. The most important colony was established at

Sicily began to be colonised by Greeks in the 8th century BC. Initially, this was restricted to the eastern and southern parts of the island. The most important colony was established at Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

in 734 BC. Other important Greek colonies were Naxos, Gela, Akragas, Selinunte, Himera

Himera ( Greek: ), was a large and important ancient Greek city, situated on the north coast of Sicily at the mouth of the river of the same name (the modern Imera Settentrionale), between Panormus (modern Palermo) and Cephaloedium (modern Ce ...

, Kamarina and Zancle or Messene (modern-day Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

. These city-states became an important part of classical Greek civilisation in which Sicily was part of Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia (, ; , , grc, Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς, ', it, Magna Grecia) was the name given by the Romans to the coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily; the ...

; both Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the ...

and Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientis ...

were from Sicily.

These Greek city-states enjoyed long periods of democratic government, but in times of social stress, in particular, with constant warring against Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, tyrants occasionally usurped the leadership. The more famous include: Gelo, Hiero I, Dionysius the Elder and Dionysius the Younger

Dionysius the Younger ( el, Διονύσιος ὁ Νεώτερος, 343 BC), or Dionysius II, was a Greek politician who ruled Syracuse, Sicily from 367 BC to 357 BC and again from 346 BC to 344 BC.

Biography

Dionysius II of Syracuse was the s ...

.

As the Greek and Phoenician communities grew more populous and more powerful, the Sicels and Sicanians were pushed further into the centre of the island. By the 3rd century BC, Syracuse was the most populous Greek city in the world. Sicilian politics was intertwined with politics in Greece itself, leading Athens, for example, to mount the disastrous Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415–413 BC during the Peloponnesian War between Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse and Corinth on the other. The expedition ended in a de ...

in 415 BC during the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of ...

.

In Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities o ...

, the goddess Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded as the patron and protectress of v ...

threw Mount Aitna onto the island of Sicily and upon either the gigante Enceladus

Enceladus is the sixth-largest moon of Saturn (19th largest in the Solar System). It is about in diameter, about a tenth of that of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. Enceladus is mostly covered by fresh, clean ice, making it one of the most refle ...

or Typhon

Typhon (; grc, Τυφῶν, Typhôn, ), also Typhoeus (; grc, Τυφωεύς, Typhōeús, label=none), Typhaon ( grc, Τυφάων, Typháōn, label=none) or Typhos ( grc, Τυφώς, Typhṓs, label=none), was a monstrous serpentine giant an ...

during the giants' war against the gods.

The Greeks came into conflict with the Punic trading communities, by now effectively protectorates of Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, with its capital on the African mainland not far from the southwest corner of the island. Palermo

Palermo ( , ; scn, Palermu , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital of both the autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The city is noted for its ...

was a Carthaginian city, founded in the 8th century BC by the Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

, named Zis or Sis ("Panormos" to the Greeks). Hundreds of Phoenician and Carthaginian grave sites have been found in a necropolis over a large area of Palermo, now built over, south of the Norman palace, where the Norman kings had a vast park.

In the far west, Lilybaeum (now Marsala

Marsala (, local ; la, Lilybaeum) is an Italian town located in the Province of Trapani in the westernmost part of Sicily. Marsala is the most populated town in its province and the fifth in Sicily.

The town is famous for the docking of Gius ...

) was never thoroughly Hellenized

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in th ...

. In the First and Second Sicilian Wars, Carthage was in control of all but the eastern part of Sicily, which was dominated by Syracuse. However, the dividing line between the Carthaginian west and the Greek east moved backwards and forwards frequently in the ensuing centuries.

Punic Wars

The constant warfare between Carthage and the Greek city-states eventually opened the door to an emerging third power. In the 3rd century BC, the Messanan Crisis motivated the intervention of the

The constant warfare between Carthage and the Greek city-states eventually opened the door to an emerging third power. In the 3rd century BC, the Messanan Crisis motivated the intervention of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

into Sicilian affairs, and led to the First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years ...

between Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

and Carthage. The Carthaginians sent forces to Hiero II

Hiero II ( el, Ἱέρων Β΄; c. 308 BC – 215 BC) was the Greek tyrant of Syracuse from 275 to 215 BC, and the illegitimate son of a Syracusan noble, Hierocles, who claimed descent from Gelon. He was a former general of Pyrrhus of Epirus an ...

, the military leader of the Greek city-states. The Romans fought for the Mamertines of Messina and, Rome and Carthage declared war on each other for the control of Sicily. This led to a war based mainly on the water, which served as an advantage to the Carthaginians, as they were led by Hamilcar, a general who earned his surname Barca (meaning lightning) due to his fast attacks on Roman supply lines. Romans attempted to hide the weakness in their navy by using large moveable planks to invade enemy ships and forcing hand-to-hand combat, but they still struggled due to the lack of a talented general. Hamilcar and his mercenaries struggled to receive additional aid and reinforcements, as the Carthaginian government hoarded their wealth due to greed and belief that Hamilcar could win on his own. His victory at Drepana

Drepana ( grc, Δρέπανα) was an Elymian, Carthaginian, and Roman port in antiquity on the western coast of Sicily. It was the site of a crushing Roman defeat by the Carthaginians in 249BC. It eventually developed into the modern Italian ...

in 249 BC was his last, as he was forced to withdraw. In 241 BC, after the Romans adapted better to battle at sea, the Carthaginians surrendered. By the end of the war in (242 BC), and with the death of Hiero II

Hiero II ( el, Ἱέρων Β΄; c. 308 BC – 215 BC) was the Greek tyrant of Syracuse from 275 to 215 BC, and the illegitimate son of a Syracusan noble, Hierocles, who claimed descent from Gelon. He was a former general of Pyrrhus of Epirus an ...

, all of Sicily except Syracuse was in Roman hands, becoming Rome's first province outside of the Italian peninsula.

Hamilcar died in combat in 228 BC, and following the death of his son Hasdrubal, his third son Hannibal took control of the military. He followed a more aggressive path, laying siege to Saguntum, a city allied to Rome. This action started the second war, in which Hannibal took many early victories in Northern Italy. However, like his father in the first war, a lack of reinforcements and support from the Carthaginians put his forces at a disadvantage. Additionally, Roman general Scipio realized that attacking Carthage itself would force Hannibal to recall his troops. Following the loss at the Battle of Zama in 202, Hannibal pushed the senate to surrender. The success of the Carthaginians during most of the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

encouraged many of the Sicilian cities to revolt against Roman rule. Rome sent troops to put down the rebellions (it was during the siege of Syracuse that Archimedes was killed). Carthage briefly took control of parts of Sicily, but in the end was driven off. Many Carthaginian sympathizers were killed - in 210 BC the Roman consul M. Valerius told the Roman Senate that "no Carthaginian remains in Sicily".

The Third and final war was the shortest of the three, being the most one sided as well. Carthage waged war against Numidia, an ancient kingdom located modern day Algeria, and upon losing had to pay additional war debts. The Roman Senate expected to be asked for permission, and decided that Carthage posed too much of a threat. After the Carthaginians refused to dismantle the city in 149 BC, the Third Punic War began. The conflict lasted only three years, as the city was besieged during the entire conflict until the city fell and was sacked by the Romans. The power of the Roman Empire expanded largely due to these three wars, and allowed for a prolonged control of Sicily, an incredibly important piece to the Roman empire for hundreds of years.

Roman Period

For the next 600 years, Sicily was a

For the next 600 years, Sicily was a province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions out ...

of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

and later Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

. It was something of a rural backwater, important chiefly for its grain fields, which were a mainstay of the food supply for the city of Rome until the annexation of Egypt after the Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between a maritime fleet of Octavian led by Marcus Agrippa and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII Philopator. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, ...

largely did away with that role. The empire made little effort to Romanize the region, which remained largely Greek. One notable event of this period was the notorious misgovernment of Verres

Gaius Verres (c. 120–43 BC) was a Roman magistrate, notorious for his misgovernment of Sicily. His extortion of local farmers and plundering of temples led to his prosecution by Cicero, whose accusations were so devastating that his defence adv ...

, as recorded by Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

in 70 BC in his oration, In Verrem

"In Verrem" ("Against Verres") is a series of speeches made by Cicero in 70 BC, during the corruption and extortion trial of Gaius Verres, the former governor of Sicily. The speeches, which were concurrent with Cicero's election to the aedileshi ...

. Another was the Sicilian revolt under Sextus Pompeius, which liberated the island from Roman rule for a brief period.

A lasting legacy of the Roman occupation, in economic and agricultural terms, was the establishment of the large landed estates, often owned by distant Roman nobles (the '' latifundia'').

Despite its largely neglected status, Sicily was able to make a contribution to Roman culture through the historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

and the poet Calpurnius Siculus

Titus Calpurnius Siculus was a Roman bucolic poet. Eleven eclogues have been handed down to us under his name, of which the last four, from metrical considerations and express manuscript testimony, are now generally attributed to Nemesianus, who li ...

. The most famous archeological remains of this period are the mosaics of a nobleman's villa in present-day Piazza Armerina

Piazza Armerina ( Gallo-Italic of Sicily: ''Ciazza''; Sicilian: ''Chiazza'') is a '' comune'' in the province of Enna of the autonomous island region of Sicily, southern Italy.

History

The city of Piazza (as it was called before 1862) develop ...

. An inscription from Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania ...

's reign lauds the emperor as "The Restorer of Sicily", although it is not known what he did to earn this accolade.

It was also during this period that we find one of the first Christian communities in Sicily. Amongst the earliest Christian martyrs were the Sicilians Saint Agatha of Catania

Catania (, , Sicilian and ) is the second largest municipality in Sicily, after Palermo. Despite its reputation as the second city of the island, Catania is the largest Sicilian conurbation, among the largest in Italy, as evidenced also b ...

and Saint Lucy of Syracuse.

Early Middle Ages

Germanic and Byzantine period

As the Roman Empire was falling apart, a tribe ofFranks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

conquered Syracuse in 280 AD; subsequently a Germanic tribe known as the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

took Sicily in 440 AD under the rule of their king Genseric. The Vandals had entered the Empire crossing the Rhine the last night of 406 with three other tribes. They were in Gaul until October 409 when they entered Spain where they remained until 429 crossing over to North Africa. The Romans, unable to defeat them, ceded two Mauretanian provinces and the western half of Numidia in 435. However, in October 439 they seized the rest of the Roman provinces, inserting themselves as an important power in western Europe. After the sacking of Rome in 455 the Vandals seized Corsica and Sardinia which they kept until the end of their kingdom in 533. In 476 Odoacer gained most of Sicily for the payment of tribute to the Vandals. In 491 Theodoric gained control over the entire island after repulsing a Vandal invasion and seizing their remaining outpost Lilybaeum on the western tip of the island.

The Gothic War took place between the Ostrogoths and the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the

The Gothic War took place between the Ostrogoths and the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. Sicily was the first part of Italy to be taken under general Belisarius who was commissioned by Eastern Emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as l ...

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

. Sicily was used as a base for the Byzantines to conquer the rest of Italy, with Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

, Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

and the Ostrogoth capital Ravenna

Ravenna ( , , also ; rgn, Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 408 until its collapse in 476. It then served as the c ...

falling within five years. However, a new Ostrogoth king, Totila, drove down the Italian peninsula, plunder

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

ing and conquering Sicily in 550. Totila, in turn, was defeated and killed in the Battle of Taginae

At the Battle of Taginae (also known as the Battle of Busta Gallorum) in June/July 552, the forces of the Byzantine Empire under Narses broke the power of the Ostrogoths in Italy, and paved the way for the temporary Byzantine reconquest of the ...

by the Byzantine general Narses

, image=Narses.jpg

, image_size=250

, caption=Man traditionally identified as Narses, from the mosaic depicting Justinian and his entourage in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

, birth_date=478 or 480

, death_date=566 or 573 (aged 86/95)

, allegi ...

in 552.

When Ravenna fell to the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

in the middle of the 6th century, Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

became Byzantium's main western outpost. Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

was gradually supplanted by Greek as the national language and the Greek rites of the Eastern Church were adopted.

The Byzantine Emperor Constans II

Constans II ( grc-gre, Κώνστας, Kōnstas; 7 November 630 – 15 July 668), nicknamed "the Bearded" ( la, Pogonatus; grc-gre, ὁ Πωγωνᾶτος, ho Pōgōnãtos), was the Eastern Roman emperor from 641 to 668. Constans was the last ...

decided to move from the capital Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

to Syracuse in Sicily in 663, the following year he launched an assault from Sicily against the Lombard Duchy of Benevento, which then occupied most of Southern Italy. The rumours that the capital of the empire was to be moved to Syracuse, along with small raids probably cost Constans his life as he was assassinated in 668. His son Constantine IV succeeded him, a brief usurpation in Sicily by Mizizios being quickly suppressed by the new emperor.

From the late 7th century, Sicily joined with

From the late 7th century, Sicily joined with Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

to form the Byzantine Theme of Sicily.

Muslim period

In 826, Euphemius, the commander of the Byzantine fleet of Sicily, forced a nun to marry him. EmperorMichael II

Michael II ( gr, Μιχαὴλ, , translit=Michaēl; 770–829), called the Amorian ( gr, ὁ ἐξ Ἀμορίου, ho ex Amoríou) and the Stammerer (, ''ho Travlós'' or , ''ho Psellós''), reigned as Byzantine Emperor from 25 December 820 to ...

caught wind of the matter and ordered that general Constantine end the marriage and cut off Euphemius' nose. Euphemius rose up, killed Constantine and then occupied Syracuse; he in turn was defeated and driven out to North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

.

There, Euphemius requested the help of Ziyadat Allah, the Aghlabid Emir of Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, in regaining the island; an Islamic army of Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

, Cretan Saracens and Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian. ...

was sent. The conquest was a see-saw affair; the local population resisted fiercely and the Arabs suffered considerable dissension and infighting among themselves. It took over a century to complete the conquest (although practically complete by 902, the last Byzantine strongholds held out until 965).

Throughout this reign, continued revolts by Byzantine Sicilians happened, especially in the east, and part of the lands were even re-occupied before being quashed. Agricultural items, such as oranges, lemon

The lemon (''Citrus limon'') is a species of small evergreen trees in the flowering plant family Rutaceae, native to Asia, primarily Northeast India (Assam), Northern Myanmar or China.

The tree's ellipsoidal yellow fruit is used for culin ...

s, pistachio

The pistachio (, ''Pistacia vera''), a member of the cashew family, is a small tree originating from Central Asia and the Middle East. The tree produces seeds that are widely consumed as food.

''Pistacia vera'' is often confused with other spe ...

and sugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus '' Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalk ...

, were brought to Sicily, the native Christians were allowed nominal freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedo ...

with jaziya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in Isla ...

(tax on non-Muslims, imposed by Muslim rulers) to their rulers for the right to practise their own religion privately. However, the Emirate of Sicily

The Emirate of Sicily ( ar, إِمَارَة صِقِلِّيَة, ʾImārat Ṣiqilliya) was an Islamic kingdom that ruled the island of Sicily from 831 to 1091. Its capital was Palermo (Arabic: ''Balarm''), which during this period became ...

began to fragment as inner-dynasty related quarrels took place between the Muslim regime.

By the 11th century, mainland southern Italian powers were hiring ferocious Norman mercenaries, who were Christian descendants of the

By the 11th century, mainland southern Italian powers were hiring ferocious Norman mercenaries, who were Christian descendants of the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

; it was the Normans under Roger I who conquered Sicily from the Muslims. After taking Apulia

it, Pugliese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographic ...

and Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, he occupied Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in t ...

with an army of 700 knights. In 1068, Robert Guiscard

Robert Guiscard (; Modern ; – 17 July 1085) was a Norman adventurer remembered for the conquest of southern Italy and Sicily. Robert was born into the Hauteville family in Normandy, went on to become count and then duke of Apulia and Calab ...

and his men defeated the Muslims at Misilmeri; but the most crucial battle was the siege of Palermo, which led to Sicily being completely in Norman control by 1091.

Many historians have recently argued that the Norman conquest of Islamic Sicily (1060–91) was the start of the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

.

Viking Age

In 860, according to an account by the Norman monk Dudo of Saint-Quentin, a Viking fleet, probably under Björn Ironside and Hastein, landed in Sicily, conquering it. Many Norsemen fought as mercenaries in Southern Italy, including theVarangian Guard

The Varangian Guard ( el, Τάγμα τῶν Βαράγγων, ''Tágma tōn Varángōn'') was an elite unit of the Byzantine Army from the tenth to the fourteenth century who served as personal bodyguards to the Byzantine emperors. The Varang ...

led by Harald Hardrada

Harald Sigurdsson (; – 25 September 1066), also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet ''Hardrada'' (; modern no, Hardråde, roughly translated as "stern counsel" or "hard ruler") in the sagas, was King of Norway from 1046 t ...

, who later became king of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty kingd ...

, who conquered Sicily between 1038 and 1040, with the help of Norman mercenaries, under William de Hauteville, who won his nickname ''Iron Arm'' by defeating the emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

of Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

in single combat, and a Lombard contingent, led by Arduin

''Arduin'' is a fictional universe and fantasy role-playing system created in the mid-1970s by David A. Hargrave. It was the first published "cross-genre" fantasy RPG, with everything from interstellar wars to horror and historical drama, altho ...

. The Varangians were first used as mercenaries in Italy against the Arabs in 936. Runestones

A runestone is typically a raised stone with a runic inscription, but the term can also be applied to inscriptions on boulders and on bedrock. The tradition began in the 4th century and lasted into the 12th century, but most of the runestones d ...

were raised in Sweden in memory of warriors who died in Langbarðaland ( Land of the Lombards), the Old Norse name for southern Italy.

Later, several Anglo-Danish and Norwegian nobles participated in the Norman conquest of southern Italy, like Edgar the Ætheling

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and '' gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, r ...

, who left England in 1086, and Jarl Erling Skakke, who won his nickname ''("Skakke", meaning bent head)'' after a battle against Arabs in Sicily. On the other hand, many Anglo-Danish rebels fleeing William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

, joined the Byzantines in their struggle against the Robert Guiscard

Robert Guiscard (; Modern ; – 17 July 1085) was a Norman adventurer remembered for the conquest of southern Italy and Sicily. Robert was born into the Hauteville family in Normandy, went on to become count and then duke of Apulia and Calab ...

, duke of Apulia, in Southern Italy.

High Middle Ages

Norman period (1091–1194)

The most significant changes that the Normans were to bring to Sicily were in the areas of religion, language and population. Almost from the moment that Roger I controlled much of the island, immigration was encouraged from

The most significant changes that the Normans were to bring to Sicily were in the areas of religion, language and population. Almost from the moment that Roger I controlled much of the island, immigration was encouraged from Northern Europe

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe Northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54°N, or may be based on other geographical factors ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative region ...

and Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

. For the most part, these consisted of Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

who were Vulgar Latin

Vulgar Latin, also known as Popular or Colloquial Latin, is the range of non-formal registers of Latin spoken from the Late Roman Republic onward. Through time, Vulgar Latin would evolve into numerous Romance languages. Its literary counterpa ...

variety-speaking and more inclined to support the Western church. With time, Sicily would become overwhelmingly Roman Catholic and a new vulgar Latin idiom would emerge that was distinct to the island.

Palermo continued on as the capital under the Hauteville. Roger's son, Roger II of Sicily

Roger II ( it, Ruggero II; 22 December 1095 – 26 February 1154) was King of Sicily and Africa, son of Roger I of Sicily and successor to his brother Simon. He began his rule as Count of Sicily in 1105, became Duke of Apulia and Calabria i ...

, was ultimately able to raise the status of the island, along with his holds of Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the pe ...

to a kingdom in 1130. During this period, the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily ( la, Regnum Siciliae; it, Regno di Sicilia; scn, Regnu di Sicilia) was a state that existed in the south of the Italian Peninsula and for a time the region of Ifriqiya from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 un ...

was prosperous and politically powerful, becoming one of the wealthiest states in all of Europe; even wealthier than England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

.

The Siculo-Norman kings relied mostly on the local Sicilian population for the more important government and administrative positions. For the most part, initially Greek, Arabic and Latin were used as languages of administration while Norman was the language of the royal court. Significantly, immigrants from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, North Europe

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe Northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54°N, or may be based on other geographical factors ...

, Northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative region ...

and Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

arrived during this period and linguistically the island would eventually become Latinised, in terms of church it would become completely Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

, previously under the Byzantines it had been more Eastern Christian.

Roger II's grandson, William II (also known as William the Good) reigned from 1166 to 1189. His greatest legacy was the building of the Cathedral of Monreale

Monreale (; ; Sicilian: ''Murriali'') is a town and ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Palermo, in Sicily, southern Italy. It is located on the slope of Monte Caputo, overlooking the very fertile valley called ''"La Conca d'oro"'' (the Gold ...

, perhaps the best surviving example of Siculo-Norman architecture. In 1177, he married Joan of England (also known as Joanna). She was the daughter of Henry II of England

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (french: link=no, Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress, or Henry Plantagenet, was King of England from 1154 until his death in 1189, and as such, was the first Angevin kin ...

and the sister of Richard the Lion Heart

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was ...

.

When William died in 1189 without an heir, this effectively signalled the end of the Hauteville succession. Some years earlier, Roger II's daughter, Constance of Sicily

Constance I ( it, Costanza; 2 November 1154 – 27 November 1198) was reigning Queen of Sicily from 1194–98, jointly with her spouse from 1194 to 1197, and with her infant son Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1198, as the heiress of the ...

(William II's aunt) had been married off to Henry who was son of Emperor Frederick I and would later become Emperor Henry VI, meaning that the crown now legitimately transferred to him. Such an eventuality was unacceptable to the local barons, and they voted in Tancred of Sicily

Tancred ( it, Tancredi; 113820 February 1194) was King of Sicily from 1189 to 1194. He was born in Lecce an illegitimate son of Roger III, Duke of Apulia (the eldest son of King Roger II) by his mistress Emma, a daughter of Achard II, Count o ...

, an illegitimate grandson of Roger II. During his reign Tancred was able to put down rebellions, defeat an invasion by Henry VI and capture Empress Constance, but Pope Celestine III forced him to release her.

Hohenstaufen reign (1194–1266)

Tancred died in 1194, just as Henry VI and Constance were travelling down the Italian peninsula to claim their crown. Henry rode into Palermo at the head of a large army unopposed and thus ended the Siculo-Norman Hauteville dynasty, replaced by the south

Tancred died in 1194, just as Henry VI and Constance were travelling down the Italian peninsula to claim their crown. Henry rode into Palermo at the head of a large army unopposed and thus ended the Siculo-Norman Hauteville dynasty, replaced by the south German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

(Swabia

Swabia ; german: Schwaben , colloquially ''Schwabenland'' or ''Ländle''; archaic English also Suabia or Svebia is a cultural, historic and linguistic region in southwestern Germany.

The name is ultimately derived from the medieval Duchy of ...

n) Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynas ...

. Just as Henry VI was being crowned as King of Sicily in Palermo, Constance gave birth to Frederick II (sometimes referred to as Frederick I of Sicily).

Frederick was raised in Palermo and, like his grandfather Roger II, was passionate about science, learning and literature. He created one of the earliest universities in Europe (in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

), wrote a book on falconry

Falconry is the hunting of wild animals in their natural state and habitat by means of a trained bird of prey. Small animals are hunted; squirrels and rabbits often fall prey to these birds. Two traditional terms are used to describe a person ...

( De arte venandi cum avibus, one of the first handbooks based on scientific observation rather than medieval mythology). He instituted far-reaching law reform formally dividing church and state and applying the same justice to all classes of society, and was the patron of the Sicilian School of poetry, the first time an Italianate form of vulgar Latin was used for literary expression, creating the first standard that could be read and used throughout the peninsula.

Many repressive measures, passed by Frederick II, were introduced in order to please the Popes who could not tolerate Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

being practiced in the heart of Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

, which resulted in a rebellion of Sicily's Muslims.A.Lowe: The Barrier and the bridge, op cit;p.92. This in turn triggered organized resistance and systematic reprisals and marked the final chapter of Islam in Sicily. The Muslim problem plagued Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynas ...

rule in Sicily under Henry VI and his son Frederick II. The rebellion abated, but direct papal pressure induced Frederick to transfer all his Muslim subjects deep into the Italian hinterland, to Lucera. In 1224, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

and grandson of Roger II, expelled the few remaining Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

from Sicily.

Frederick was succeeded firstly by his son, Conrad, and then by his illegitimate son, Manfred, who essentially usurped the crown (with the support of the local barons) while Conrad's son, Conradin

Conrad III (25 March 1252 – 29 October 1268), called ''the Younger'' or ''the Boy'', but usually known by the diminutive Conradin (german: link=no, Konradin, it, Corradino), was the last direct heir of the House of Hohenstaufen. He was Duke ...

was still quite young. A unique feature of all the Swabian kings of Sicily, perhaps inherited from their Siculo-Norman forefathers, was their preference in retaining a regiment of Saracen soldiers as their personal and most trusted regiments. Such a practice, amongst others, ensured an ongoing antagonism between the papacy and the Hohenstaufens. The Hohenstaufen rule ended with the death of Manfredi at the battle of Benevento

Benevento (, , ; la, Beneventum) is a city and '' comune'' of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill above sea level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino (or Beneventano) and the ...

(1266).

Late Middle Ages

Angevins and the Sicilian Vespers

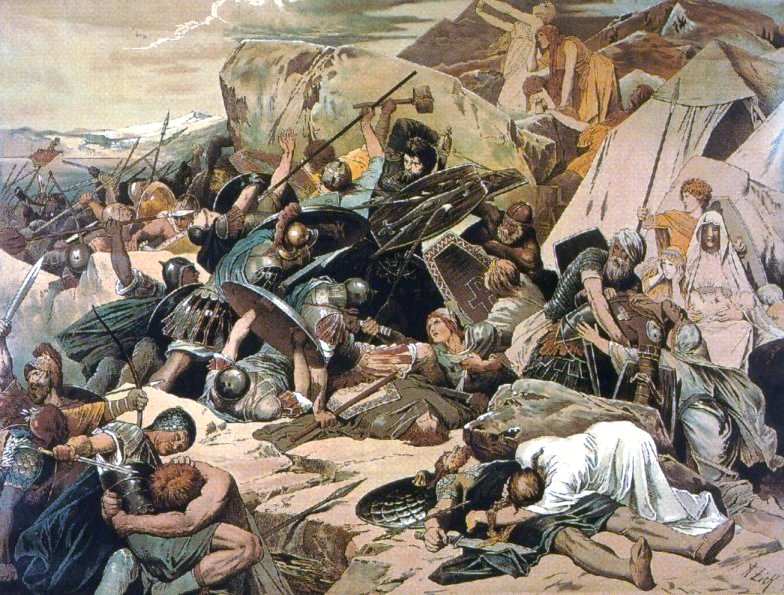

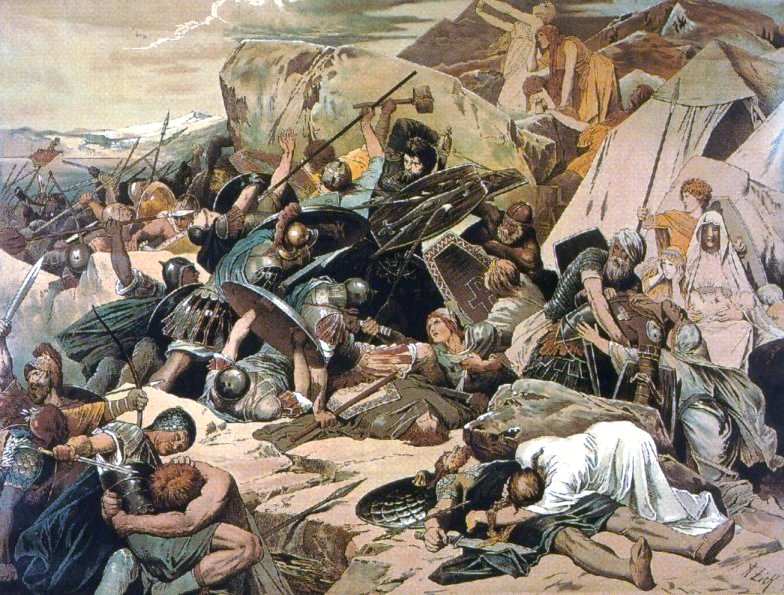

Throughout Frederick's reign, there had been substantial antagonism between the Kingdom and the Papacy, which was part of the wider Guelph Ghibelline conflict. This antagonism was transferred to the Hohenstaufen house, and ultimately against Manfred.

In 1266,

Throughout Frederick's reign, there had been substantial antagonism between the Kingdom and the Papacy, which was part of the wider Guelph Ghibelline conflict. This antagonism was transferred to the Hohenstaufen house, and ultimately against Manfred.

In 1266, Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, duke of Anjou Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

*County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

**Duke ...

, with the support of the Church, led an army against the Kingdom. They fought at Benevento

Benevento (, , ; la, Beneventum) is a city and '' comune'' of Campania, Italy, capital of the province of Benevento, northeast of Naples. It is situated on a hill above sea level at the confluence of the Calore Irpino (or Beneventano) and the ...

, just to the north of the Kingdom's border. Manfred was killed in battle and Charles was crowned King of Sicily by Pope Clement IV.

Growing opposition to French officialdom and high taxation led to an insurrection in 1282 (the Sicilian Vespers

The Sicilian Vespers ( it, Vespri siciliani; scn, Vespiri siciliani) was a successful rebellion on the island of Sicily that broke out at Easter 1282 against the rule of the French-born king Charles I of Anjou, who had ruled the Kingdom of ...

), which was successful with the support of Peter III of Aragón

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises th ...

, who was crowned King of Sicily by the island's barons. Peter III had previously married Manfred's daughter, Constance, and it was for this reason that the Sicilian barons effectively invited him. This victory split the Kingdom in two, with Charles continuing to rule the mainland part (still known as the Kingdom of Sicily as well).

The ensuing War of the Sicilian Vespers lasted until the peace of Caltabellotta

The Peace of Caltabellotta, signed on 31 August 1302, was the last of a series of treaties, including those of Tarascon and Anagni, designed to end the conflict between the Houses of Anjou and Barcelona for ascendancy in the Mediterranean and esp ...

in 1302, although it was to continue on and off for a period of 90 years. With two kings both claiming to be the King of Sicily, the separate island kingdom became known as the Kingdom of Trinacria Trinacria may refer to:

*the ancient Name of Sicily

**Sicily in the classical Greek period, see History of Greek and Hellenistic Sicily

**Name for the Kingdom of Sicily during the 1300s

**Name for the emblem of Sicily (the triskeles with the Gorg ...

. It is this split that ultimately led to the creation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and al ...

some 500 years on.

Aragonese period

Peter III's son,Frederick III of Sicily

Frederick II (or III) (13 December 1272 – 25 June 1337) was the regent of the Kingdom of Sicily from 1291 until 1295 and subsequently King of Sicily from 1295 until his death. He was the third son of Peter III of Aragon and served in th ...

(also known as Frederick II of Sicily) reigned from 1298 to 1337. For the whole of the 14th century, Sicily was essentially an independent kingdom, ruled by relatives of the kings of Aragon, but for all intents and purposes they were Sicilian kings. The Sicilian parliament, already in existence for a century, continued to function with wide powers and responsibilities.

During this period, a sense of a Sicilian people and nation emerged, that is to say, the population was no longer divided between Greek, Arab and Latin peoples. Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

and Aragonese were the languages of the royal court, and Sicilian was the language of the parliament and the general citizenry. These circumstances continued until 1409 when because of failure of the Sicilian line of the Aragonese dynasty, the Sicilian throne became part of the Crown of Aragon

The Crown of Aragon ( , ) an, Corona d'Aragón ; ca, Corona d'Aragó, , , ; es, Corona de Aragón ; la, Corona Aragonum . was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of ...

.

The island's first university was founded at Catania

Catania (, , Sicilian and ) is the second largest municipality in Sicily, after Palermo. Despite its reputation as the second city of the island, Catania is the largest Sicilian conurbation, among the largest in Italy, as evidenced also b ...

in 1434. Antonello da Messina