Hugh Ruttledge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

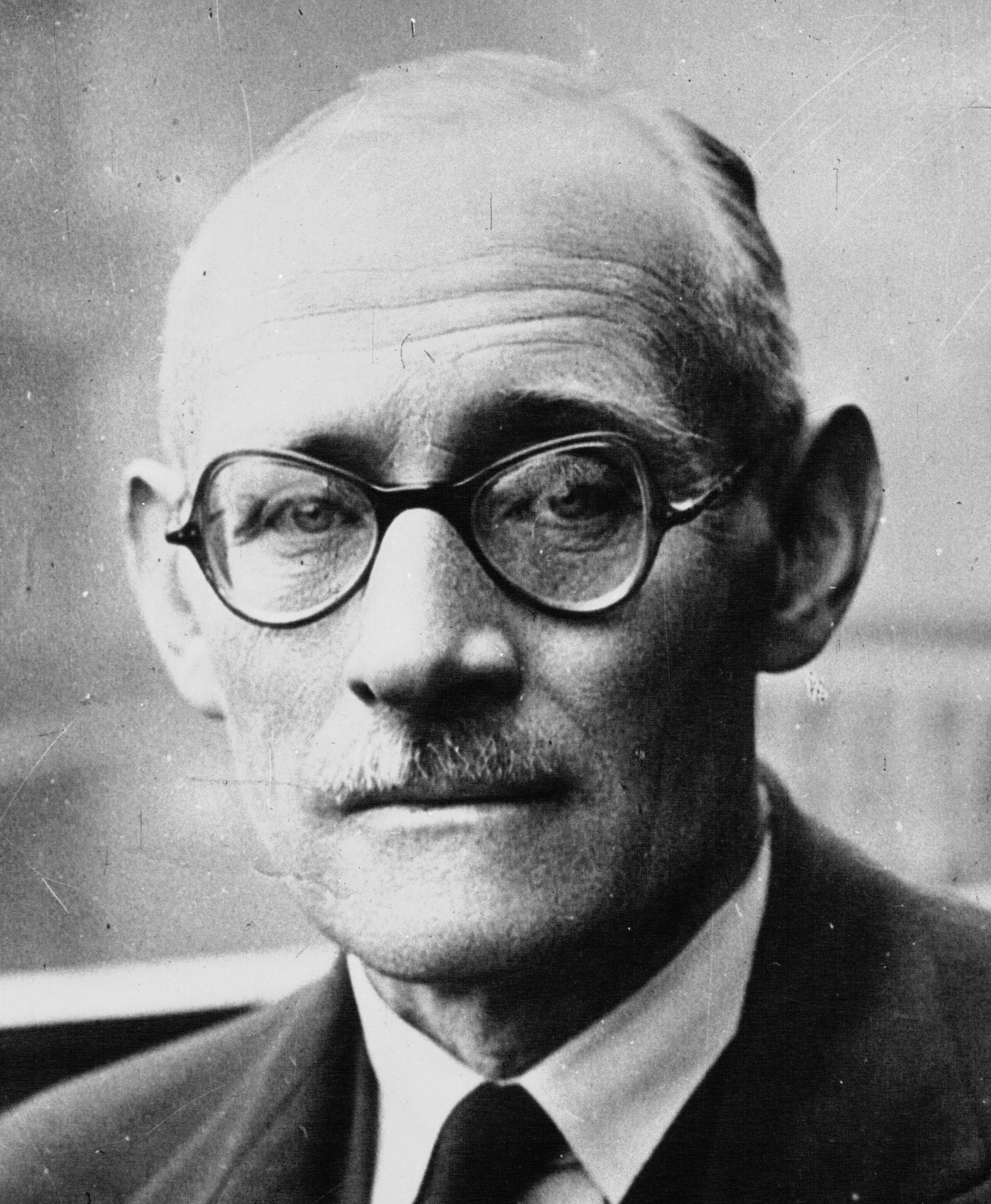

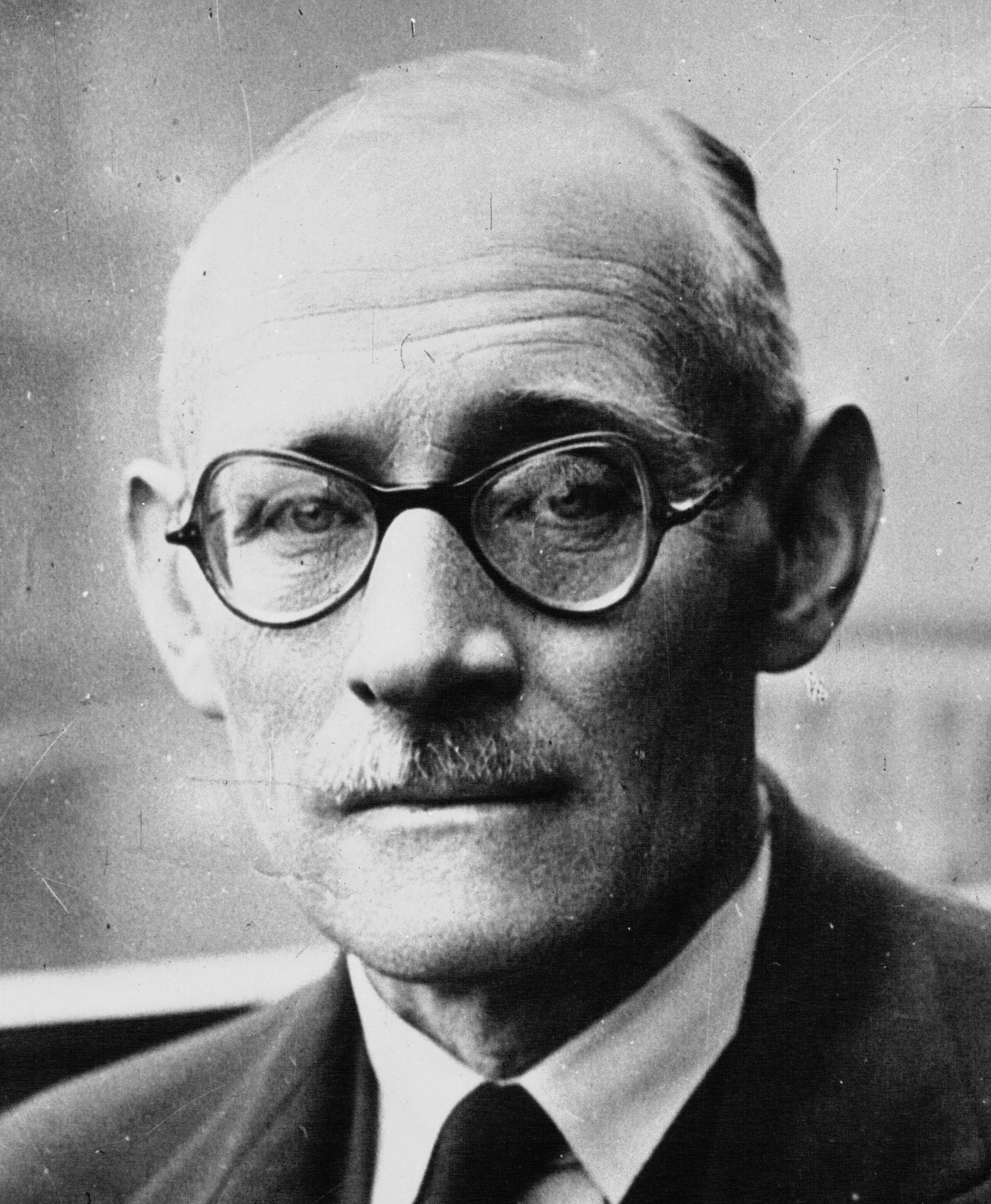

Hugh Ruttledge (24 October 1884 – 7 November 1961) was an English civil servant and

Hugh Ruttledge (24 October 1884 – 7 November 1961) was an English civil servant and

Ruttledge, Hugh (1884–1961)

(subscription required) accessed 1 March 2008

Although Longstaff reported that the many peoples of Ruttledge's district had great respect for him, Ruttledge took early retirement from the Indian Civil Service in 1929. Somervell commented that "He was so tired of making plans that he knew to be right, to find that the Government always thought they knew better than the man on the spot". By the time of his retirement, Ruttledge and his wife had crossed twelve different high passes.

Ruttledge attempted to reach

Although Longstaff reported that the many peoples of Ruttledge's district had great respect for him, Ruttledge took early retirement from the Indian Civil Service in 1929. Somervell commented that "He was so tired of making plans that he knew to be right, to find that the Government always thought they knew better than the man on the spot". By the time of his retirement, Ruttledge and his wife had crossed twelve different high passes.

Ruttledge attempted to reach

Hugh Ruttledge (24 October 1884 – 7 November 1961) was an English civil servant and

Hugh Ruttledge (24 October 1884 – 7 November 1961) was an English civil servant and mountaineer

Mountaineering or alpinism, is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending tall mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas. Indoor climbing, sport climbing, an ...

who was the leader of two expeditions to Mount Everest

Mount Everest (; Tibetan: ''Chomolungma'' ; ) is Earth's highest mountain above sea level, located in the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas. The China–Nepal border runs across its summit point. Its elevation (snow heig ...

in 1933

Events

January

* January 11 – Sir Charles Kingsford Smith makes the first commercial flight between Australia and New Zealand.

* January 17 – The United States Congress votes in favour of Philippines independence, against the wis ...

and 1936

Events

January–February

* January 20 – George V of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India, dies at his Sandringham Estate. The Prince of Wales succeeds to the throne of the United Kingdom as King E ...

.

Early life

The son of Lt.-Colonel Edward Butler Ruttledge, of theIndian Medical Service

The Indian Medical Service (IMS) was a military medical service in British India, which also had some civilian functions. It served during the two World Wars, and remained in existence until the independence of India in 1947. Many of its officer ...

, and of his wife Alice Dennison, Ruttledge was educated at schools in Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

and Lausanne

, neighboring_municipalities= Bottens, Bretigny-sur-Morrens, Chavannes-près-Renens, Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Crissier, Cugy, Écublens, Épalinges, Évian-les-Bains (FR-74), Froideville, Jouxtens-Mézery, Le Mont-sur-Lausanne, Lugrin (FR-74), ...

and then at Cheltenham College

("Work Conquers All")

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public schoolIndependent School Day and Boarding School

, religion = Church of England

, president =

, head_label = Head

, head = Nicola Huggett

...

. In 1903 he matriculated as an exhibitioner

An exhibition is a type of scholarship award or bursary.

United Kingdom and Ireland

At the universities of Dublin, Oxford, Cambridge and Sheffield, at some public schools, and various other UK educational establishments, an exhibition is a sma ...

at Pembroke College, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, and in 1906 he took a second-class Honours degree in the Classical Honours tripos.Audrey Salkeld, ''Ruttledge, Hugh (1884–1961), mountaineer'' in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 2004, online aRuttledge, Hugh (1884–1961)

(subscription required) accessed 1 March 2008

India and mountaineering

Ruttledge passed theIndian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 300 million ...

examination in 1908 and spent a year at the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

studying Indian law, history and languages, before going out to India towards the end of 1909.

He was posted as an assistant in Roorkee

Roorkee (Rūṛkī) is a city and a municipal corporation in the Haridwar district of the state of Uttarakhand, India. It is from Haridwar city, the district headquarter. It is spread over a flat terrain under Sivalik Hills of Himalayas. The c ...

and Sitapur

Sitapur is a city and a municipal board in Sitapur district in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. It is located 90 kilometres north of state capital, Lucknow. The traditional origin for the name is said to be by the King Vikramāditya from Lord ...

, then was promoted a magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

at Agra

Agra (, ) is a city on the banks of the Yamuna river in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, about south-east of the national capital New Delhi and 330 km west of the state capital Lucknow. With a population of roughly 1.6 million, Agra is ...

. He played polo and took part in field sports including big game-hunting until in 1915 a fall from a horse left him with a curved spine and a compacted hip. Also in 1915, he married Dorothy Jessie Hair Elder at Agra, with whom he had one son and two daughters.

In 1917, Ruttledge transferred to Lucknow

Lucknow (, ) is the capital and the largest city of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and it is also the second largest urban agglomeration in Uttar Pradesh. Lucknow is the administrative headquarters of the eponymous district and division ...

as city magistrate and in 1921 became deputy commissioner there. In 1921, while on leave in Europe, he took up climbing in the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

.

In 1925, he went as deputy commissioner to Almora

Almora ( Kumaoni: ''Almāḍ'') is a municipal board and a cantonment town in the state of Uttarakhand, India. It is the administrative headquarters of Almora district. Almora is located on a ridge at the southern edge of the Kumaon Hills of the ...

in the foothills of the Himalaya

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

, and within sight of some of its great peaks. Despite his injuries, Ruttledge was still able to climb, and he made up his mind to get to know every part of his district. With his wife he began to explore the glaciers and peaks on India's northern frontier.

The highest peak in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

was then Nanda Devi

Nanda Devi is the second-highest mountain in India, after Kangchenjunga, and the highest located entirely within the country (Kangchenjunga is on the border of India and Nepal). It is the 23rd-highest peak in the world.

Nanda Devi was consid ...

, ringed around by a series of peaks above , so that it had hardly been approached. In 1925, with Colonel R. C. Wilson of the Indian Army and Dr T. H. Somervell, the Ruttledges scouted the area to the north-east of the great mountain, hoping to find an approach to it by Milam and the Timphu glacier; they eventually concluded that this would be too hazardous.

Together with his wife, he completed the pilgrim circuit of Mount Kailas

Mount Kailash (also Kailasa; ''Kangrinboqê'' or ''Gang Rinpoche''; Tibetan: གངས་རིན་པོ་ཆེ; ; sa, कैलास, ), is a mountain in the Ngari Prefecture, Tibet Autonomous Region of China. It has an altitude of ...

in July 1926, his wife being the first Western woman to perform this ceremony.

Ruttledge was in Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

on official business, but because the official whom he was expecting to see, the senior Garpon of Gartok

Gartok (), is made of twin encampment settlements of Gar Günsa and Gar Yarsa (, Wade–Giles: ''Ka-erh-ya-sha'') in the Gar County in the Ngari Prefecture of Tibet. Gar Gunsa served as the winter encampment and Gar Yarsa as the summer encampment ...

, was detained elsewhere, Ruttledge and his wife decided to make the Kailas ''parikrama'', whilst Wilson (who accompanied them on the trip) and a Sherpa called Satan (''sic'') explored the various approaches to the mountain. Ruttledge considered the north face of Kailas to be high and 'utterly unclimbable'.

He contemplated an ascent of the mountain via the north-east ridge but decided that he did not have sufficient time; on returning to Almora he wrote that he had enjoyed 'some of enjoyable trekking, performed entirely on foot to the scandal of right-thinking Indians and Tibetans'. Ruttledge and his wife also made the first known crossing of Traill's Pass between Nanda Devi and Nanda Kot

Nanda Kot ( Kumaoni-नन्दा कोट) is a mountain peak of the Himalaya range located in the Pithoragarh district of Uttarakhand state in India. It lies in the Kumaon Himalaya, just outside the ring of peaks enclosing the Nanda Devi S ...

.

In 1927, with T. G. Longstaff and supported by Sherpas, Ruttledge reconnoitred the Nandakini

Nandakini is a river and is one of the six main tributaries of the Ganges. Originating in the glaciers below Nanda Ghunti on the Nanda Devi Sanctuary, the river joins the Alaknanda at Nandprayag (870m), which is one of the panch prayag

Pan ...

valley and crossed a high pass between Trisul

Trisul is a group of three Himalayan mountain peaks of western Kumaun, Uttarakhand, with the highest (Trisul I) reaching 7120m. The three peaks resemble a trident - in Sanskrit, Trishula, trident, is the weapon of Shiva. The Trishul grou ...

and Nanda Ghunti

Nanda Ghunti is a {{convert, 6309, m, ft, adj=mid, -high mountain in Garhwal, India. It lies on the outer rim of the Nanda Devi Sanctuary.

The mountain was first surveyed by T. G. Longstaff in 1907. Eric Shipton surveyed it from the west in ...

.

Although Longstaff reported that the many peoples of Ruttledge's district had great respect for him, Ruttledge took early retirement from the Indian Civil Service in 1929. Somervell commented that "He was so tired of making plans that he knew to be right, to find that the Government always thought they knew better than the man on the spot". By the time of his retirement, Ruttledge and his wife had crossed twelve different high passes.

Ruttledge attempted to reach

Although Longstaff reported that the many peoples of Ruttledge's district had great respect for him, Ruttledge took early retirement from the Indian Civil Service in 1929. Somervell commented that "He was so tired of making plans that he knew to be right, to find that the Government always thought they knew better than the man on the spot". By the time of his retirement, Ruttledge and his wife had crossed twelve different high passes.

Ruttledge attempted to reach Nanda Devi

Nanda Devi is the second-highest mountain in India, after Kangchenjunga, and the highest located entirely within the country (Kangchenjunga is on the border of India and Nepal). It is the 23rd-highest peak in the world.

Nanda Devi was consid ...

three times in the 1930s and failed each time. In a letter to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' he wrote that 'Nanda Devi imposes on her votaries an admission test as yet beyond their skill and endurance', adding that gaining the Nanda Devi Sanctuary alone was more difficult than reaching the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

.

1933 Everest expedition

In 1933 permission was granted to the British by the authorities in Tibet for a further attempt on the mountain. TheMount Everest Committee

The Mount Everest Committee was a body formed by the Alpine Club (UK), Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society to co-ordinate and finance the 1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition to Mount Everest and all subsequent British e ...

's task of finding a leader for this, the fourth British expedition, was made difficult by the incapacity of Charles Granville Bruce

Brigadier-General The Honourable Charles Granville Bruce, CB, MVO (7 April 1866 – 12 July 1939) was a veteran Himalayan mountaineer and leader of the second and third British expeditions to Mount Everest in 1922 and 1924. In recognition of t ...

(the leader of previous British expeditions to the mountain), and the unwillingness of Major Geoffrey Bruce and Brigadier E. F. Norton to assume the role. As Ruttledge wrote, 'it was necessary to find someone with experience of Himalayan peoples as well as with mountaineering knowledge, and eventually the lot fell upon me'.

The personnel for this attempt, which used the then-standard route of choice of the British via the North Col __NOTOC__

The North Col (; ) refers to the sharp-edged pass carved by glaciers in the ridge connecting Mount Everest and Changtse in Tibet. It forms the head of the East Rongbuk Glacier.

When climbers attempt to climb Everest via the North ridge ...

, was made up of a combination of military types and Oxbridge graduates, and included none of those who had been on the 1924 attempt. The full British complement was Frank Smythe

Francis Sydney Smythe, better known as Frank Smythe or F. S. Smythe (6 July 1900 – 27 June 1949), was an English mountaineer, author, photographer and botanist. He is best remembered for his mountaineering in the Alps as well as in the Himal ...

, Eric Shipton

Eric Earle Shipton, CBE (1 August 1907 – 28 March 1977), was an English Himalayan mountaineer.

Early years

Shipton was born in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1907 where his father, a tea planter, died before he was three years old. When he was eigh ...

, Jack Longland

Sir John Laurence Longland (26 June 1905 – 29 November 1993) was an educator, mountain climber, and broadcaster.

After a brilliant student career Longland became a don at Durham University in the 1930s. He formed a lifelong concern for the we ...

, Eugene Birnie, Percy Wyn-Harris

Sir Percy Wyn-Harris Order of St Michael and St George, KCMG Order of the British Empire, MBE Venerable Order of Saint John, KStJ (24 August 1903 – 25 February 1979) was an English Mountaineering, mountaineer, colonial administrator, and yacht ...

, Edward Shebbeare, Lawrence Wager

Lawrence Rickard Wager, commonly known as Bill Wager, (5 February 1904 – 20 November 1965) was a British geologist, explorer and mountaineer, described as "one of the finest geological thinkers of his generation"Vincent and best remembered for ...

, George Wood-Johnson, Hugh Boustead, Colin Crawford, Tom Brocklebank, E. Thompson and William Maclean, with Raymond Greene

Charles Raymond Greene (17 April 1901 – 6 December 1982) was a British doctor and an accomplished Mountaineering, mountaineer.

Biography

Greene was born in Berkhamsted.Andrew Irvine, who had disappeared on the peak on the 1924 British Expedition with

Details of four portraits of Ruttledge in the National Portrait Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ruttledge, Hugh 1884 births 1961 deaths English mountain climbers Indian Civil Service (British India) officers Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge Alumni of the University of London People educated at Cheltenham College Sportspeople from Gloucestershire British people in colonial India

George Mallory

George Herbert Leigh Mallory (18 June 1886 – 8 or 9 June 1924) was an English mountaineer who took part in the first three British expeditions to Mount Everest in the early 1920s.

Born in Cheshire, Mallory became a student at Winchester ...

.

One of the men rejected for this expedition was Tenzing Norgay

Tenzing Norgay (; ''tendzin norgyé''; perhaps 29 May 1914 – 9 May 1986), born Namgyal Wangdi, and also referred to as Sherpa Tenzing, was a Nepali-Indian Sherpa mountaineer. He was one of the first two people known to reach the sum ...

, who made the first ascent

In mountaineering, a first ascent (abbreviated to FA in guide books) is the first successful, documented attainment of the top of a mountain or the first to follow a particular climbing route. First mountain ascents are notable because they en ...

of Everest in 1953 with Sir Edmund Hillary

Sir Edmund Percival Hillary (20 July 1919 – 11 January 2008) was a New Zealand mountaineer, explorer, and philanthropist. On 29 May 1953, Hillary and Sherpa mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the first climbers confirmed to have reached t ...

. Fortunately, Ruttledge had the foresight to hire Tenzing to come with him to Everest in 1936.

In 1934 Ruttledge was awarded a Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

Founder's Medal; his citation read 'For his journeys in the Himalayas and his leadership of the Mount Everest Expedition, 1933.' Although the Mount Everest committee set up an inquiry into the reasons for the failure of the expedition, Ruttledge was not blamed, almost all members of the expedition expressing their admiration and fondness for him.

Publicity

Following the 1933 expedition H.J. Cave & Sons used the fact that their Osilite trunks had been carried on the expedition as marketing. Following the success of this many other companies looked at sponsoring further attempts.1936 Everest expedition

With the near-universal support for his leadership on the 1933 trip, Ruttledge was selected to lead a second expedition (the sixth British expedition), which was the largest to date to attempt Everest. Alongside veterans of the 1933 expedition – Frank Smythe, Eric Shipton and Percy Wyn-Harris – team members were Charles Warren, Edmund Wigram, Edwin Kempson, Peter Oliver, James Gavin, John Morris andGordon Noel Humphreys

Gordon Noel Humphreys (1883–1966) was a British born surveyor, pilot, botanist, explorer and doctor. Originally trained as a surveyor, Humphreys worked in both Mexico and Uganda. During World War I he served as a pilot with the Royal Flying Corp ...

. William Smyth-Windham was again chief radio operator. Although the North Col was reached, a combination of high winds, storms and waist-deep snow made progress above 7,000 m difficult and, with the monsoon arriving early, Ruttledge called off the expedition.

Tenzing Norgay

Tenzing Norgay (; ''tendzin norgyé''; perhaps 29 May 1914 – 9 May 1986), born Namgyal Wangdi, and also referred to as Sherpa Tenzing, was a Nepali-Indian Sherpa mountaineer. He was one of the first two people known to reach the sum ...

wrote of Ruttledge and the 1936 expedition:

Later life

In 1932 Ruttledge planned a life as a farmer and to this end bought the island ofGometra

Gometra ( gd, Gòmastra) is an island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, lying west of Mull. It lies immediately west of Ulva, to which it is linked by a bridge, and at low tide also by a beach. It is approximately in size. The name is also app ...

in the Inner Hebrides

The Inner Hebrides (; Scottish Gaelic: ''Na h-Eileanan a-staigh'', "the inner isles") is an archipelago off the west coast of mainland Scotland, to the south east of the Outer Hebrides. Together these two island chains form the Hebrides, whic ...

, just off the west coast of Mull

Mull may refer to:

Places

*Isle of Mull, a Scottish island in the Inner Hebrides

** Sound of Mull, between the Isle of Mull and the rest of Scotland

* Mount Mull, Antarctica

*Mull Hill, Isle of Man

* Mull, Arkansas, a place along Arkansas Highway ...

. Upon returning from the 1936 expedition to Everest he decided that a life at sea would be preferable, and he bought several boats – a converted Watson lifeboat and later a larger sailing cutter – to pursue this idea. In 1950 he moved ashore, buying a house on the edge of Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite which forms the uplands dates from the Carboniferous ...

.

Ruttledge died in Stoke

Stoke is a common place name in the United Kingdom.

Stoke may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

The largest city called Stoke is Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire. See below.

Berkshire

* Stoke Row, Berkshire

Bristol

* Stoke Bishop

* Stok ...

, Plymouth, on 7 November 1961.

Bibliography

*Ruttledge, Hugh, ''Everest: The Unfinished Adventure'', Hodder and Staughton, 1937 *Salkeld, Audrey, 'Ruttledge, Hugh (1884–1961)', inOxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

References

External links

Details of four portraits of Ruttledge in the National Portrait Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ruttledge, Hugh 1884 births 1961 deaths English mountain climbers Indian Civil Service (British India) officers Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge Alumni of the University of London People educated at Cheltenham College Sportspeople from Gloucestershire British people in colonial India