The history of the Roman Empire covers the

history of ancient Rome from the fall of the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingd ...

in 27 BC until the abdication of

Romulus Augustulus in AD 476 in the West, and the

Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had beg ...

in the East in AD 1453. Ancient Rome became a territorial empire while still a republic, but was then ruled by

Roman emperors beginning with

Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

(), becoming the Roman Empire following the death of the last republican

dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in ti ...

, the first emperor's adoptive father

Julius Caesar.

Rome had begun expanding shortly after the founding of the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingd ...

in the 6th century BC, though it did not expand outside the

Italian Peninsula until the 3rd century BC. Civil war engulfed the Roman state in the mid 1st century BC, first between Julius Caesar and

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

, and finally between

Octavian and

Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the ...

. Antony was defeated at the

Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between a maritime fleet of Octavian led by Marcus Agrippa and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII Philopator. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, ne ...

in 31 BC. In 27 BC, the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

made Octavian ''

imperator'' ("commander") thus beginning the

Principate

The Principate is the name sometimes given to the first period of the Roman Empire from the beginning of the reign of Augustus in 27 BC to the end of the Crisis of the Third Century in AD 284, after which it evolved into the so-called Dominate ...

, the first epoch of Roman imperial history usually dated from 27 BC to AD 284; they later awarded him the name Augustus, "the venerated". Subsequent emperors all took this name as the imperial title ''

Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

''.

The success of Augustus in establishing principles of dynastic succession was limited by his outliving a number of talented potential heirs; the

Julio-Claudian dynasty

, native_name_lang= Latin, coat of arms=Great_Cameo_of_France-removebg.png, image_size=260px, caption= The Great Cameo of France depicting emperors Augustus, Tiberius, Claudius and Nero, type=Ancient Roman dynasty, country= Roman Empire, estat ...

lasted for four more emperors—

Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

,

Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanic ...

,

Claudius, and

Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unt ...

—before it yielded in AD 69 to the strife-torn

Year of the Four Emperors

The Year of the Four Emperors, AD 69, was the first civil war of the Roman Empire, during which four emperors ruled in succession: Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian. It is considered an important interval, marking the transition from ...

, from which

Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Em ...

emerged as victor. Vespasian became the founder of the brief

Flavian dynasty

The Flavian dynasty ruled the Roman Empire between AD 69 and 96, encompassing the reigns of Vespasian (69–79), and his two sons Titus (79–81) and Domitian (81–96). The Flavians rose to power during the civil war of 69, known ...

, to be followed by the

Nerva–Antonine dynasty which produced the "

Five Good Emperors

5 is a number, numeral, and glyph.

5, five or number 5 may also refer to:

* AD 5, the fifth year of the AD era

* 5 BC, the fifth year before the AD era

Literature

* ''5'' (visual novel), a 2008 visual novel by Ram

* ''5'' (comics), an awa ...

":

Nerva,

Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presid ...

,

Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman '' municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispan ...

,

Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius ( Latin: ''Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius''; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatori ...

and the philosophically inclined

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

. In the view of the Greek historian

Dio Cassius, a contemporary observer, the accession of the emperor

Commodus in AD 180 marked the descent "from a kingdom of gold to one of rust and iron"—a famous comment which has led some historians, notably

Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is ...

, to take Commodus' reign as the beginning of the

decline of the Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

.

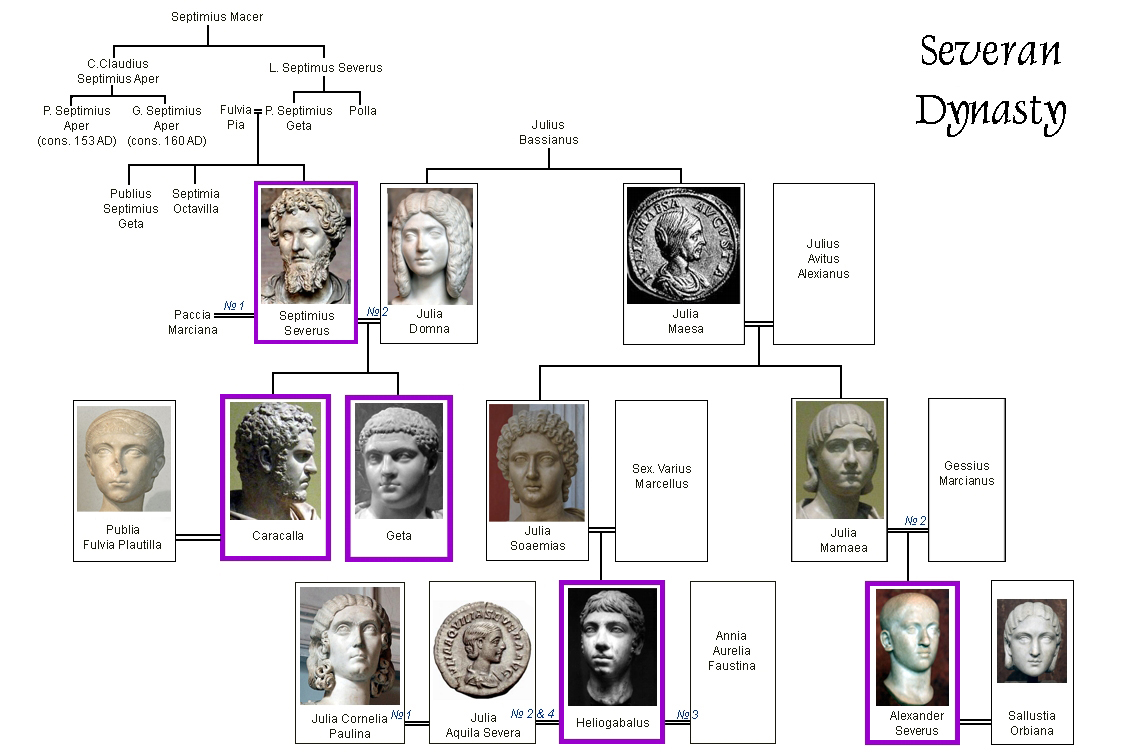

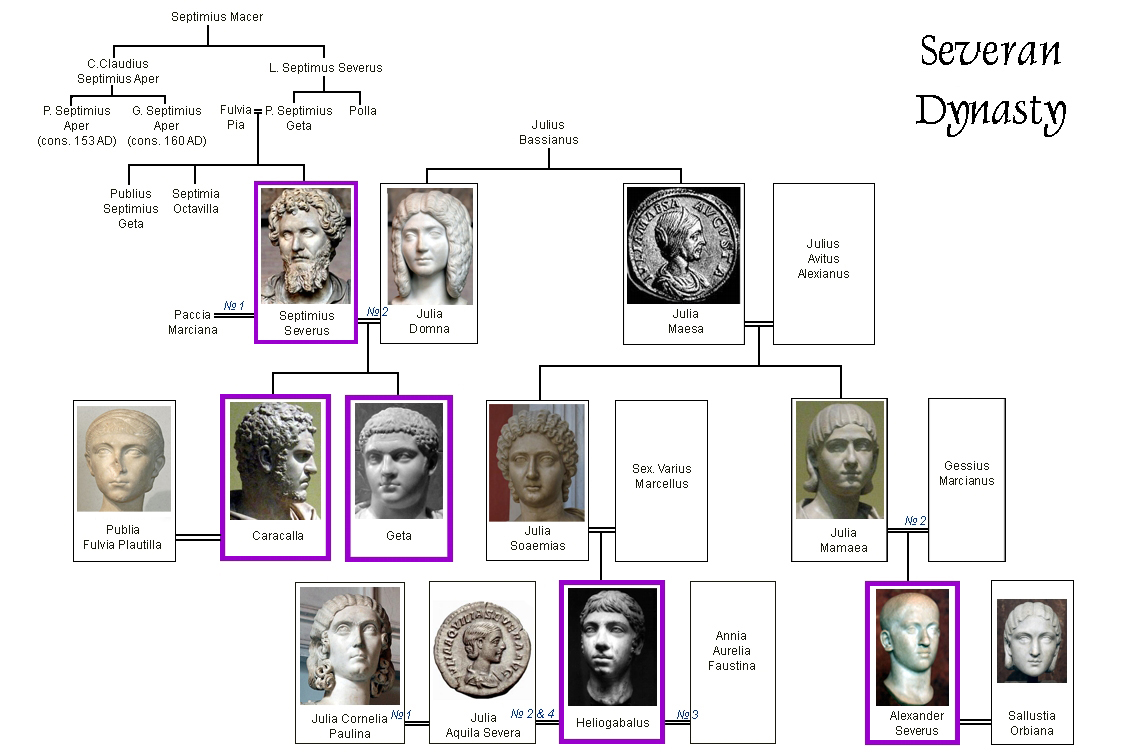

In 212, during the reign of

Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname "Caracalla" () was Roman emperor from 198 to 217. He was a member of the Severan dynasty, the elder son of Emperor ...

,

Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome (Latin: ''civitas'') was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, t ...

was granted to all freeborn inhabitants of the Empire. Despite this gesture of universality, the

Severan dynasty was tumultuous—an emperor's reign was ended routinely by his murder or execution—and following its collapse, the Roman Empire was engulfed by the

Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis (AD 235–284), was a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed. The crisis ended due to the military victories of Aurelian and with the ascensi ...

, a period of invasions, civil strife, economic disorder, and epidemic disease. In defining

historical epochs, this crisis is typically viewed as marking the start of the

Later Roman Empire,

and also the transition from

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations ...

to

Late antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English has ...

. In the reign of

Philip the Arab

Philip the Arab ( la, Marcus Julius Philippus "Arabs"; 204 – September 249) was Roman emperor from 244 to 249. He was born in Aurantis, Arabia, in a city situated in modern-day Syria. After the death of Gordian III in February 244, Phili ...

(), Rome celebrated the thousandth anniversary of her founding by

Romulus and Remus

In Roman mythology, Romulus and Remus (, ) are twin brothers whose story tells of the events that led to the founding of the city of Rome and the Roman Kingdom by Romulus, following his fratricide of Remus. The image of a she-wolf sucklin ...

with the

Saecular Games.

Diocletian () restored stability to the empire, modifying the role of ''princeps'' and becoming the first emperor to be addressed by

Roman citizens as ''domine'', "master" or "lord" or referred to as ''dominus noster'' "our lord". Diocletian's reign also brought the Empire's most concerted effort against the perceived threat of

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

, the

"Great Persecution". The state of

absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

that began with Diocletian endured until the fall of the

Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

in 1453.

Diocletian divided the empire into four regions, each ruled by an emperor (the

Tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the ''augusti'', and their juniors colleagues and designated successors, the '' caesares'' ...

). Confident that he fixed the disorders plaguing Rome, he abdicated along with his co-''augustus'', and the Tetrarchy eventually collapsed in the

civil wars of the Tetrarchy

The Civil Wars of the Tetrarchy were a series of conflicts between the co-emperors of the Roman Empire, starting in 306 AD with the usurpation of Maxentius and the defeat of Severus and ending with the defeat of Licinius at the hands of C ...

. Order was eventually restored by the victories of

Constantine, who became the first emperor to

convert to Christianity, and who founded

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

as a new capital for the empire after defeating his co-emperor

Licinius

Valerius Licinianus Licinius (c. 265 – 325) was Roman emperor from 308 to 324. For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan, AD 313, that granted official toleration to ...

. The reign of

Julian

Julian may refer to:

People

* Julian (emperor) (331–363), Roman emperor from 361 to 363

* Julian (Rome), referring to the Roman gens Julia, with imperial dynasty offshoots

* Saint Julian (disambiguation), several Christian saints

* Julian (give ...

, who under the influence of his adviser

Mardonius attempted to restore

Classical Roman and

Hellenistic religion

The concept of Hellenistic religion as the late form of Ancient Greek religion covers any of the various systems of beliefs and practices of the people who lived under the influence of ancient Greek culture during the Hellenistic period and the ...

, only briefly interrupted the succession of Christian emperors of the

Constantinian dynasty

The Constantinian dynasty is an informal name for the ruling family of the Roman Empire from Constantius Chlorus (died 306) to the death of Julian in 363. It is named after its most famous member, Constantine the Great, who became the sole ruler ...

. During the decades of the

Valentinianic and

Theodosian dynasties, the established practice of multiple emperors was continued.

Theodosius I, the last emperor to rule over both the

Eastern empire and the whole

Western empire, died in AD 395 after making Christianity the

official religion of the Empire.

The Western Roman Empire began to

disintegrate

Disintegration or disintegrate may refer to:

Music Albums

* ''Disintegrate'' (Zyklon album) or the title song, 2006

* ''Disintegration'' (The Cure album) or the title song, 1989

* ''Disintegration'', by I've Sound, 2002

Songs

* "Disintegrate ...

in the early 5th century as the

Germanic migrations and invasions of the

Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roma ...

overwhelmed the capacity of the Empire to assimilate the immigrants and fight off the invaders.

Most chronologies place the end of the Western Roman Empire in 476, when

Romulus Augustulus was

forced to abdicate to the Germanic warlord

Odoacer

Odoacer ( ; – 15 March 493 AD), also spelled Odovacer or Odovacar, was a soldier and statesman of barbarian background, who deposed the child emperor Romulus Augustulus and became Rex/Dux (476–493). Odoacer's overthrow of Romulus Augustu ...

. By placing himself under the rule of the eastern emperor

Zeno, rather than naming himself or a puppet ruler as emperor, as other Germanic chiefs, had done, Odoacer ended the separate Roman government of the Western empire. The Eastern empire exercised diminishing control over the west over the course of the next century. The empire in the east—known today as the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

, but referred to in its time as the "Roman Empire" or by various other names—ended in 1453 with the death of

Constantine XI and the

fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had beg ...

to the

Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

.

27 BC–AD 14: Augustus

Octavian

Octavian, the grandnephew and adopted son of Julius Caesar, had made himself a central military figure during the chaotic period following

Caesar's assassination. In 43 BC, at the age of twenty he became one of the three members of the

Second Triumvirate, a political alliance with

Marcus Lepidus

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (; c. 89 BC – late 13 or early 12 BC) was a Roman general and statesman who formed the Second Triumvirate alongside Octavian and Mark Antony during the final years of the Roman Republic. Lepidus had previously be ...

and

Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the ...

. Octavian and Antony defeated the last of Caesar's assassins in 42 BC at the

Battle of Philippi

The Battle of Philippi was the final battle in the Wars of the Second Triumvirate between the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (of the Second Triumvirate) and the leaders of Julius Caesar's assassination, Brutus and Cassius in 42 BC, at ...

, although after this point tensions began to rise between the two. The triumvirate ended in 32 BC, torn apart by the competing ambitions of its members: Lepidus was forced into exile and Antony, who had allied himself with his lover Queen

Cleopatra VII

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler. ...

of

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

, committed suicide in 30 BC following his defeat at the

Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between a maritime fleet of Octavian led by Marcus Agrippa and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII Philopator. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, ne ...

(31 BC) by the fleet of Octavian. Octavian subsequently annexed Egypt to the empire.

Now sole ruler of Rome, Octavian began a full-scale reformation of military, fiscal and political matters. The

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

granted him power over appointing its membership and several successive

consulship

A consul held the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic ( to 27 BC), and ancient Romans considered the consulship the second-highest level of the '' cursus honorum'' (an ascending sequence of public offices to which polit ...

s, allowing him to operate within the existing constitutional machinery and thus reject titles that Romans associated with monarchy, such as ''rex'' ("king"). The

dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

, a military office in the early Republic typically lasting only for the six-month military campaigning season, had been resurrected first by

Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history and became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force.

Sulla ha ...

in the late 80s BC and then by Julius Caesar in the mid-40s; the title ''dictator'' was never again used. As the adopted heir of Julius Caesar, Octavian had taken "Caesar" as a component of his name, and handed down the name to his heirs of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. With Vespasian, one of the first emperors outside the dynasty, Caesar evolved from a family name to the imperial title ''

Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

''.

Augustus created his novel and historically unique position by consolidating the constitutional powers of several Republican offices. He renounced his

consulship

A consul held the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic ( to 27 BC), and ancient Romans considered the consulship the second-highest level of the '' cursus honorum'' (an ascending sequence of public offices to which polit ...

in 23 BC, but retained his consular ''

imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic ...

'', leading to a second compromise between Augustus and the Senate known as the

Second settlement. Augustus was granted the authority of a

tribune (''tribunicia potestas''), though not the title, which allowed him to call together the Senate and people at will and lay business before it, veto the actions of either the Assembly or the Senate, preside over elections, and it gave him the right to speak first at any meeting. Also included in Augustus's tribunician authority were powers usually reserved for the

Roman censor

The censor (at any time, there were two) was a magistrate in ancient Rome who was responsible for maintaining the census, supervising public morality, and overseeing certain aspects of the government's finances.

The power of the censor was abso ...

; these included the right to supervise public morals and scrutinise laws to ensure they were in the public interest, as well as the ability to hold a census and determine the membership of the Senate. No tribune of Rome ever had these powers, and there was no precedent within the Roman system for consolidating the powers of the tribune and the censor into a single position, nor was Augustus ever elected to the office of Censor. Whether censorial powers were granted to Augustus as part of his tribunician authority, or he simply assumed those, is a matter of debate.

In addition to those powers, Augustus was granted sole ''

imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic ...

'' within the city of

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

itself; all armed forces in the city, formerly under the control of the

prefects, were now under the sole authority of Augustus. Additionally, Augustus was granted ''imperium proconsulare maius'' (literally: "eminent proconsular command"), the right to interfere in any

province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outsi ...

and override the decisions of any

governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

. With ''imperium maius'', Augustus was the only individual able to grant a

triumph to a successful general as he was ostensibly the leader of the entire

Roman army

The Roman army (Latin: ) was the armed forces deployed by the Romans throughout the duration of Ancient Rome, from the Roman Kingdom (c. 500 BC) to the Roman Republic (500–31 BC) and the Roman Empire (31 BC–395 AD), and its medieval contin ...

.

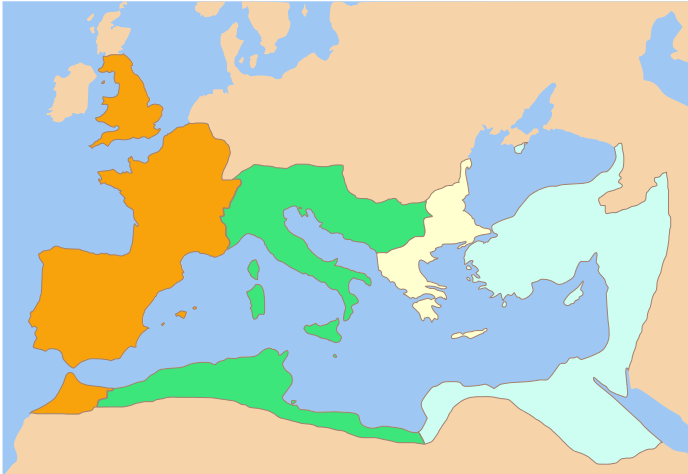

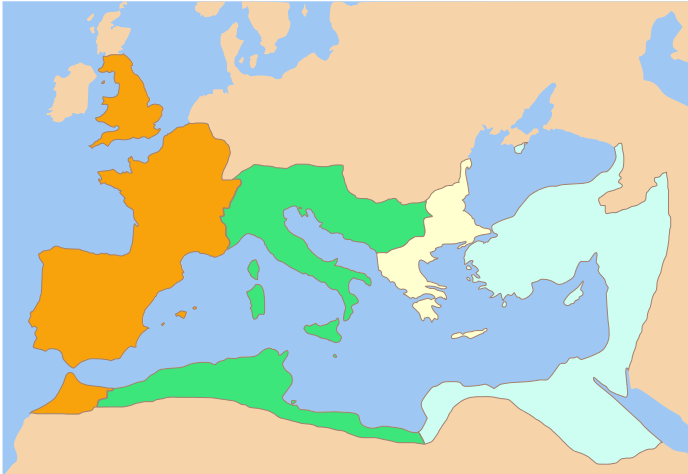

The Senate re-classified the provinces at the frontiers (where the vast majority of the legions were stationed) as

imperial provinces, and gave control of those to Augustus. The peaceful provinces were re-classified as

senatorial provinces, governed as they had been during the Republic by members of the Senate sent out annually by the central government. Senators were prohibited from so much as visiting

Roman Egypt, given its great wealth and history as a base of power for opposition to the new emperor. Taxes from the imperial provinces went into the ''

fiscus'', the fund administrated by persons chosen by and answerable to Augustus. The revenue from senatorial provinces continued to be sent to the state treasury ''(

aerarium),'' under the supervision of the Senate.

The

Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of t ...

s, which had reached an unprecedented 50 in number because of the civil wars, were reduced to 28. Several legions, particularly those with members of doubtful loyalties, were simply disbanded. Other legions were united, a fact hinted by the title ''Gemina'' (Twin). Augustus also created nine special

cohorts

Cohort or cohortes may refer to:

* Cohort (educational group), a group of students working together through the same academic curriculum

* Cohort (floating point), a set of different encodings of the same numerical value

* Cohort (military unit), ...

to maintain peace in

Italia

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, with three, the

Praetorian Guard

The Praetorian Guard (Latin: ''cohortēs praetōriae'') was a unit of the Imperial Roman army that served as personal bodyguards and intelligence agents for the Roman emperors. During the Roman Republic, the Praetorian Guard were an escort f ...

, kept in Rome. Control of the ''fiscus'' enabled Augustus to ensure the loyalty of the legions through their pay.

Augustus completed the conquest of

Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: His ...

, while subordinate generals expanded Roman possessions in

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

. Augustus' final task was to ensure an orderly succession of his powers. His stepson

Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

had conquered

Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now wes ...

,

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, stre ...

,

Raetia, and temporarily

Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north ...

for the Empire, and was thus a prime candidate. In 6 BC, Augustus granted some of his powers to his stepson, and soon after he recognised Tiberius as his heir. In AD 13, a law was passed which extended Augustus' powers over the provinces to Tiberius, so that Tiberius' legal powers were equivalent to, and independent from, those of Augustus.

Attempting to secure the borders of the Empire upon the rivers

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , ...

and

Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Rep ...

, Augustus ordered the invasions of

Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

,

Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

, and Pannonia (south of the Danube), and Germania (west of the Elbe). At first everything went as planned, but then disaster struck. The

Illyrian tribes revolted and had to be crushed, and three full legions under the command of

Publius Quinctilius Varus

Publius Quinctilius Varus ( Cremona, 46 BC – Teutoburg Forest, AD 9) was a Roman general and politician under the first Roman emperor Augustus. Varus is generally remembered for having lost three Roman legions when ambushed by Germanic tribe ...

were ambushed and destroyed at the

Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, described as the Varian Disaster () by Roman historians, took place at modern Kalkriese in AD 9, when an alliance of Germanic peoples ambushed Roman legions and their auxiliaries, led by Publius Quinctil ...

in AD 9 by Germanic tribes led by

Arminius. Being cautious, Augustus secured all territories west of the

Rhine

The Rhine ; french: Rhin ; nl, Rijn ; wa, Rén ; li, Rien; rm, label=Sursilvan, Rein, rm, label=Sutsilvan and Surmiran, Ragn, rm, label=Rumantsch Grischun, Vallader and Puter, Rain; it, Reno ; gsw, Rhi(n), including in Alsatian dialect, Al ...

and contented himself with retaliatory raids. The rivers Rhine and Danube became the permanent borders of the Roman empire in the North.

In AD 14, Augustus died at the age of seventy-five, having ruled the Empire for forty years, and was succeeded as emperor by

Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

.

Sources

The

Augustan Age is not as well documented as the age of Caesar and

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

.

Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

wrote his history during Augustus's reign and covered all of Roman history through to 9 BC, but only

epitome

An epitome (; gr, ἐπιτομή, from ἐπιτέμνειν ''epitemnein'' meaning "to cut short") is a summary or miniature form, or an instance that represents a larger reality, also used as a synonym for embodiment. Epitomacy represents "t ...

s survive of his coverage of the late Republican and Augustan periods. Important primary sources for the Augustan period include:

*''

Res Gestae Divi Augusti'', Augustus's highly partisan autobiography,

*''Historiae Romanae'' by

Velleius Paterculus, the best

annals of the Augustan period,

*''Controversiae'' and ''Suasoriae'' of

Seneca the Elder

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Elder (; c. 54 BC – c. 39 AD), also known as Seneca the Rhetorician, was a Roman writer, born of a wealthy equestrian family of Corduba, Hispania. He wrote a collection of reminiscences about the Roman schools of rhe ...

.

Works of poetry such as

Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the ...

's ''

Fasti

In ancient Rome, the ''fasti'' (Latin plural) were chronological or calendar-based lists, or other diachronic records or plans of official and religiously sanctioned events. After Rome's decline, the word ''fasti'' continued to be used for si ...

'' and

Propertius's Fourth Book, legislation and engineering also provide important insights into Roman life of the time. Archaeology, including

maritime archaeology

Maritime archaeology (also known as marine archaeology) is a discipline within archaeology as a whole that specifically studies human interaction with the sea, lakes and rivers through the study of associated physical remains, be they vessels, s ...

,

aerial surveys

Aerial survey is a method of collecting geomatics or other imagery by using airplanes, helicopters, UAVs, balloons or other aerial methods. Typical types of data collected include aerial photography, Lidar, remote sensing (using various visible ...

,

epigraphic inscriptions on buildings, and Augustan

coinage, has also provided valuable evidence about economic, social and military conditions.

Secondary ancient sources on the Augustan Age include

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

, Dio Cassius,

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

and

Lives of the Twelve Caesars by

Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire.

His most important surviving work is a set of biographies ...

.

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

's ''

Jewish Antiquities'' is the important source for

Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous south ...

, which became a

province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outsi ...

during Augustus's reign.

14–68: Julio-Claudian Dynasty

Augustus had three grandsons by his daughter

Julia the Elder

Julia the Elder (30 October 39 BC – AD 14), known to her contemporaries as Julia Caesaris filia or Julia Augusti filia (Classical Latin: IVLIA•CAESARIS•FILIA or IVLIA•AVGVSTI•FILIA), was the daughter and only biological child of August ...

:

Gaius Caesar,

Lucius Caesar and

Agrippa Postumus. None of the three lived long enough to succeed him. He therefore was succeeded by his stepson Tiberius. Tiberius was the son of

Livia

Livia Drusilla (30 January 59 BC – 28 September AD 29) was a Roman empress from 27 BC to AD 14 as the wife of Emperor Augustus Caesar. She was known as Julia Augusta after her formal adoption into the Julian family in AD 14.

Livia was the da ...

, the third wife of Augustus, by her first marriage to

Tiberius Nero. Augustus was a scion of the ''

gens

In ancient Rome, a gens ( or , ; plural: ''gentes'' ) was a family consisting of individuals who shared the same nomen and who claimed descent from a common ancestor. A branch of a gens was called a ''stirps'' (plural: ''stirpes''). The ''gen ...

''

Julia (the Julian family), one of the most ancient

patrician clans of

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, while Tiberius was a scion of the ''gens''

Claudia, only slightly less ancient than the Julians. Their three immediate successors were all descended both from the ''gens'' Claudia, through Tiberius' brother

Nero Claudius Drusus, and from ''gens'' Julia, either through Julia the Elder, Augustus' daughter from his first marriage (

Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanic ...

and Nero), or through Augustus' sister

Octavia Minor (Claudius). Historians thus refer to their dynasty as "Julio-Claudian".

14–37: Tiberius

The early years of Tiberius's reign were relatively peaceful. Tiberius secured the overall power of Rome and enriched its treasury. However, his rule soon became characterised by

paranoia. He began a series of treason trials and executions, which continued until his death in 37. He left power in the hands of the commander of the guard,

Lucius Aelius Sejanus. Tiberius himself retired to live at his villa on the island of

Capri

Capri ( , ; ; ) is an island located in the Tyrrhenian Sea off the Sorrento Peninsula, on the south side of the Gulf of Naples in the Campania region of Italy. The main town of Capri that is located on the island shares the name. It has bee ...

in 26, leaving administration in the hands of Sejanus, who carried on the persecutions with contentment. Sejanus also began to consolidate his own power; in 31 he was named co-consul with Tiberius and married

Livilla, the emperor's niece. At this point he was "hoist by his own

petard": the emperor's paranoia, which he had so ably exploited for his own gain, turned against him. Sejanus was put to death, along with many of his associates, the same year. The persecutions continued until Tiberius' death in 37.

37–41: Caligula

At the time of Tiberius's death most of the people who might have succeeded him had been killed. The logical successor (and Tiberius' own choice) was his 24-year-old grandnephew,

Gaius, better known as "Caligula" ("little boots"). Caligula was a son of

Germanicus

Germanicus Julius Caesar (24 May 15 BC – 10 October AD 19) was an ancient Roman general, known for his campaigns in Germania. The son of Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia the Younger, Germanicus was born into an influential branch of the pat ...

and

Agrippina the Elder. His paternal grandparents were

Nero Claudius Drusus and

Antonia Minor, and his maternal grandparents were

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (; BC – 12 BC) was a Roman general, statesman, and architect who was a close friend, son-in-law, and lieutenant to the Roman emperor Augustus. He was responsible for the construction of some of the most notable build ...

and

Julia the Elder

Julia the Elder (30 October 39 BC – AD 14), known to her contemporaries as Julia Caesaris filia or Julia Augusti filia (Classical Latin: IVLIA•CAESARIS•FILIA or IVLIA•AVGVSTI•FILIA), was the daughter and only biological child of August ...

. He was thus a descendant of both Augustus and Livia.

Caligula started out well, by putting an end to the persecutions and burning his uncle's records. Unfortunately, he quickly lapsed into illness. The Caligula that emerged in late 37 demonstrated features of mental instability that led modern commentators to diagnose him with such illnesses as

encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the Human brain, brain. The severity can be variable with symptoms including reduction or alteration in consciousness, headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting. Complications may include seizures, hal ...

, which can cause mental derangement,

hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism is the condition that occurs due to excessive production of thyroid hormones by the thyroid gland. Thyrotoxicosis is the condition that occurs due to excessive thyroid hormone of any cause and therefore includes hyperthyroidis ...

, or even a nervous breakdown (perhaps brought on by the stress of his position). Whatever the cause, there was an obvious shift in his reign from this point on, leading his biographers to label him as insane.

Most of what history remembers of Caligula comes from

Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire.

His most important surviving work is a set of biographies ...

, in his book ''Lives of the Twelve Caesars''. According to Suetonius, Caligula once planned to appoint his favourite horse

Incitatus to the Roman Senate. He ordered his soldiers to invade

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

to fight the sea god

Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 time ...

, but changed his mind at the last minute and had them pick sea shells on the northern end of France instead. It is believed he carried on

incest

Incest ( ) is human sexual activity between family members or close relatives. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by affinity ( marriage or stepfamily), ado ...

uous relations with his three sisters:

Julia Livilla,

Drusilla and

Agrippina the Younger

Julia Agrippina (6 November AD 15 – 23 March AD 59), also referred to as Agrippina the Younger, was Roman empress from 49 to 54 AD, the fourth wife and niece of Emperor Claudius.

Agrippina was one of the most prominent women in the Julio-Cl ...

. He ordered a statue of himself to be erected in

Herod's Temple at

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, which would have undoubtedly led to revolt had he not been dissuaded from this plan by his friend king

Agrippa I

Herod Agrippa (Roman name Marcus Julius Agrippa; born around 11–10 BC – in Caesarea), also known as Herod II or Agrippa I (), was a grandson of Herod the Great and King of Judea from AD 41 to 44. He was the father of Herod Agrippa II, the l ...

. He ordered people to be secretly killed, and then called them to his palace. When they did not appear, he would jokingly remark that they must have committed suicide.

In 41, Caligula was assassinated by the commander of the guard

Cassius Chaerea. Also killed were his fourth wife

Caesonia and their daughter

Julia Drusilla. For two days following his assassination, the Senate debated the merits of restoring the Republic.

41–54: Claudius

Claudius was a younger brother of Germanicus, and had long been considered a weakling and a fool by the rest of his family. The Praetorian Guard, however, acclaimed him as emperor. Claudius was neither paranoid like his uncle Tiberius, nor insane like his nephew Caligula, and was therefore able to administer the Empire with reasonable ability. He improved the bureaucracy and streamlined the citizenship and senatorial rolls. He ordered the construction of a winter port at

Ostia Antica for Rome, thereby providing a place for

grain

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit ( caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legu ...

from other parts of the Empire to be brought in inclement weather.

Claudius ordered the suspension of further attacks across the Rhine,

[Goldsworthy, ''In the Name of Rome'', p. 269.] setting what was to become the permanent limit of the Empire's expansion in that direction.

[Luttwak, ''The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire'', p. 38.] In 43, he resumed the

Roman conquest of Britannia that Julius Caesar had begun in the 50s BC, and incorporated more Eastern provinces into the empire.

In his own family life, Claudius was less successful. His wife

Messalina

Valeria Messalina (; ) was the third wife of Roman emperor Claudius. She was a paternal cousin of Emperor Nero, a second cousin of Emperor Caligula, and a great-grandniece of Emperor Augustus. A powerful and influential woman with a reputation ...

cuckolded him; when he found out, he had her executed and married his niece, Agrippina the Younger. She, along with several of his

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

, held an inordinate amount of power over him, and although there are conflicting accounts about his death, she may very well have poisoned him in 54. Claudius was deified later that year. The death of Claudius paved the way for Agrippina's own son, the 17-year-old Lucius Domitius Nero.

54–68: Nero

Nero ruled from 54 to 68. During his rule, Nero focused much of his attention on diplomacy, trade, and increasing the cultural capital of the empire. He ordered the building of theatres and promoted athletic games. His reign included the

Roman–Parthian War (a successful war and negotiated peace with the

Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conq ...

(58–63)), the suppression of a revolt led by

Boudica

Boudica or Boudicca (, known in Latin chronicles as Boadicea or Boudicea, and in Welsh as ()), was a queen of the ancient British Iceni tribe, who led a failed uprising against the conquering forces of the Roman Empire in AD 60 or 61. Sh ...

in

Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Gr ...

(60–61) and the improvement of cultural ties with Greece. However, he was egotistical and had severe troubles with his mother, who he felt was controlling and over-bearing. After several attempts to kill her, he finally had her stabbed to death. He believed himself a god and decided to build an opulent palace for himself. The so-called

Domus Aurea

The Domus Aurea (Latin, "Golden House") was a vast landscaped complex built by the Emperor Nero largely on the Oppian Hill in the heart of ancient Rome after the great fire in 64 AD had destroyed a large part of the city.Roth (1993)

It repla ...

, meaning golden house in Latin, was constructed atop the burnt remains of Rome after the

Great Fire of Rome (64). Because of the convenience of this many believe that Nero was ultimately responsible for the fire, spawning the legend of him fiddling while Rome burned which is almost certainly untrue. The Domus Aurea was a colossal feat of construction that covered a huge space and demanded new methods of construction in order to hold up the golden, jewel-encrusted ceilings. By this time Nero was hugely unpopular despite his attempts to blame the Christians for most of his regime's problems.

A military coup drove Nero into hiding. Facing execution at the hands of the Roman Senate, he reportedly committed suicide in 68. According to

Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

, Nero's last words were "Jupiter, what an artist perishes in me!"

68–69: Year of the Four Emperors

Since he had no heir, Nero's suicide was followed by a brief period of civil war, known as the "

Year of the Four Emperors

The Year of the Four Emperors, AD 69, was the first civil war of the Roman Empire, during which four emperors ruled in succession: Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian. It is considered an important interval, marking the transition from ...

". Between and , Rome witnessed the successive rise and fall of

Galba,

Otho and

Vitellius

Aulus Vitellius (; ; 24 September 1520 December 69) was Roman emperor for eight months, from 19 April to 20 December AD 69. Vitellius was proclaimed emperor following the quick succession of the previous emperors Galba and Otho, in a year of c ...

until the final accession of

Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Em ...

, first ruler of the

Flavian dynasty

The Flavian dynasty ruled the Roman Empire between AD 69 and 96, encompassing the reigns of Vespasian (69–79), and his two sons Titus (79–81) and Domitian (81–96). The Flavians rose to power during the civil war of 69, known ...

. The military and political anarchy created by this civil war had serious implications, such as the outbreak of the

Batavian rebellion. These events showed that a military power alone could create an emperor. Augustus had established a standing army, where individual soldiers served under the same military governors over an extended period of time. The consequence was that the soldiers in the provinces developed a degree of loyalty to their commanders, which they did not have for the emperor. Thus the Empire was, in a sense, a union of inchoate principalities, which could have disintegrated at any time.

Through his sound fiscal policy, the emperor Vespasian was able to build up a surplus in the treasury, and began construction on the

Colosseum

The Colosseum ( ; it, Colosseo ) is an oval amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, just east of the Roman Forum. It is the largest ancient amphitheatre ever built, and is still the largest standing amphitheatre in the world ...

.

Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September 81 AD) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death.

Before becoming emperor, Titus gained renown as a mili ...

, Vespasian's son and successor, quickly proved his merit, although his short reign was marked by disaster, including the eruption of Mount

Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma- stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of ...

in

Pompeii. He held the opening ceremonies in the still unfinished Colosseum, but died in 81. His brother

Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavi ...

succeeded him. Having exceedingly poor relations with the Senate, Domitian was murdered in September 96.

69–96: Flavian dynasty

The Flavians, although a relatively short-lived dynasty, helped restore stability to an empire on its knees. Although all three have been criticised, especially based on their more centralised style of rule, they issued reforms that created a stable enough empire to last well into the 3rd century. However, their background as a military dynasty led to further marginalisation of the Roman Senate, and a conclusive move away from ''princeps'', or first citizen, and toward ''imperator'', or emperor.

69–79: Vespasian

Vespasian was a remarkably successful Roman general who had been given rule over much of the eastern part of the Roman Empire. He had supported the imperial claims of Galba, after whose death Vespasian became a major contender for the throne. Following the suicide of Otho, Vespasian was able to take control of

Rome's winter grain supply in Egypt, placing him in a good position to defeat his remaining rival, Vitellius. On 20 December 69, some of Vespasian's partisans were able to occupy Rome. Vitellius was murdered by his own troops and, the next day, Vespasian, then sixty years old, was confirmed as emperor by the Senate.

Although Vespasian was considered an

autocrat by the Senate, he mostly continued the weakening of that body begun in the reign of Tiberius. The degree of the Senate's subservience can be seen from the post-dating of his accession to power, by the Senate, to 1 July, when his troops proclaimed him emperor, instead of 21 December, when the Senate confirmed his appointment. Another example was his assumption of the censorship in 73, giving him power over the make up of the Senate. He used that power to expel dissident senators. At the same time, he increased the number of senators from 200 (at that low level because of the actions of Nero and the year of crisis that followed), to 1,000; most of the new senators came not from Rome but from Italy and the urban centres within the western provinces.

Vespasian was able to liberate Rome from the financial burdens placed upon it by Nero's excesses and the civil wars. To do this, he not only increased taxes, but created new forms of taxation. Also, through his power as censor, he was able to carefully examine the fiscal status of every city and province, many paying taxes based upon information and structures more than a century old. Through this sound fiscal policy, he was able to build up a surplus in the treasury and embark on public works projects. It was he who first commissioned the ''Amphitheatrum Flavium'' (

Colosseum

The Colosseum ( ; it, Colosseo ) is an oval amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, just east of the Roman Forum. It is the largest ancient amphitheatre ever built, and is still the largest standing amphitheatre in the world ...

); he also built the Forum of Vespasian, whose centrepiece was the

Temple of Peace. In addition, he allotted sizeable subsidies to the arts, and created a chair of rhetoric at Rome.

Vespasian was also an effective emperor for the provinces, having posts all across the empire, both east and west. In the west he gave considerable favouritism to Hispania (the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, comprising modern

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, In recognized minority languages of Portugal:

:* mwl, República Pertuesa is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Macaronesian ...

) in which he granted

Latin Rights to over three hundred towns and cities, promoting a new era of urbanisation throughout the western (formerly barbarian) provinces. Through the additions he made to the Senate he allowed greater influence of the provinces in the Senate, helping to promote unity in the empire. He also extended the borders of the empire, mostly done to help strengthen the frontier defences, one of Vespasian's main goals.

The crisis of 69 had wrought havoc on the army. One of the most marked problems had been the support lent by provincial legions to men who supposedly represented the best will of their province. This was mostly caused by the placement of native auxiliary units in the areas they were recruited in, a practice Vespasian stopped; he mixed

auxiliary units with men from other areas of the empire or moved the units away from where they were recruited. Also, to reduce further the chances of another military coup, he broke up the legions and, instead of placing them in singular concentrations, spread them along the border. Perhaps the most important military reform he undertook was the extension of legion recruitment from exclusively Italy to

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only durin ...

and Hispania, in line with the Romanisation of those areas.

79–81: Titus

Titus, the eldest son of Vespasian, had been groomed to rule. He had served as an effective general under his father, helping to secure the east and eventually taking over the command of Roman armies in

Syria and

Iudaea, quelling a significant

First Jewish–Roman War at the time. He shared the consulship for several years with his father and received the best tutelage. Although there was some trepidation when he took office because of his known dealings with some of the less respectable elements of Roman society, he quickly proved his merit, even recalling many exiled by his father as a show of good faith.

However, his short reign was marked by disaster: in 79,

Mount Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma- stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of ...

erupted in

Pompeii, and in 80, a fire destroyed much of Rome. His generosity in rebuilding after these tragedies made him very popular. Titus was very proud of his work on the vast amphitheatre begun by his father. He held the opening ceremonies in the still unfinished edifice during the year 80, celebrating with a lavish show that featured 100

gladiator

A gladiator ( la, gladiator, "swordsman", from , "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gla ...

s and lasted 100 days. Titus died in 81 at the age of 41 of what is presumed to be illness; it was rumoured that his brother Domitian murdered him in order to become his successor, although these claims have little merit. Whatever the case, he was greatly mourned and missed.

81–96: Domitian

All of the Flavians had rather poor relations with the Senate due to their autocratic rule; however, Domitian was the only one who encountered significant problems. His continuous control as consul and censor throughout his rule—the former his father shared in much the same way as his Julio-Claudian forerunners, the latter presented difficulty even to obtain—were unheard of. In addition, he often appeared in full military regalia as an

imperator, an affront to the idea of what the Principate-era emperor's power was based upon: the emperor as the

princeps

''Princeps'' (plural: ''principes'') is a Latin word meaning "first in time or order; the first, foremost, chief, the most eminent, distinguished, or noble; the first man, first person". As a title, ''princeps'' originated in the Roman Republic w ...

. His reputation in the Senate aside, he kept the people of Rome happy through various measures, including donations to every resident of Rome, wild spectacles in the newly finished Colosseum, and the continuation of the public works projects of his father and brother. He also apparently had the good fiscal sense of his father; although he spent lavishly, his successors came to power with a well-endowed treasury. Domitian repelled the

Dacians

The Dacians (; la, Daci ; grc-gre, Δάκοι, Δάοι, Δάκαι) were the ancient Indo-European inhabitants of the cultural region of Dacia, located in the area near the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. They are often cons ...

in

his Dacian War; the Dacians had sought to conquer

Moesia

Moesia (; Latin: ''Moesia''; el, Μοισία, Moisía) was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Alban ...

, south of the Danube in the Roman

Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

.

Toward the end of his reign Domitian became extremely paranoid, which probably had its roots in the treatment he received by his father: although given significant responsibility, he was never trusted with anything important without supervision. This flowered into the severe and perhaps pathological repercussions following the short-lived rebellion in 89 of

Lucius Antonius Saturninus

Lucius Antonius Saturninus was a Roman senator and general during the reign of Vespasian and his sons. While governor of the province called Germania Superior, motivated by a personal grudge against Emperor Domitian, he led a rebellion known as ...

, a governor and commander in

Germania Superior. Domitian's paranoia led to a large number of arrests, executions, and seizures of property (which might help explain his ability to spend so lavishly). Eventually it reached the point where even his closest advisers and family members lived in fear. This led to his murder in 96, orchestrated by his enemies in the Senate, Stephanus (the steward of the deceased

Julia Flavia), members of the Praetorian Guard and the empress

Domitia Longina.

96–180: Five Good Emperors

The next century came to be known as the period of the "Five Good Emperors", in which the succession was peaceful and the Empire prosperous. The emperors of this period were

Nerva (96–98),

Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presid ...

(98–117),

Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman '' municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispan ...

(117–138),

Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius ( Latin: ''Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius''; 19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Born into a senatori ...

(138–161) and

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

(161–180), each one adopted by his predecessor as his successor during the former's lifetime. While their respective choices of successor were based upon the merits of the individual men they selected rather than

dynastic

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A ...

, it has been argued that the real reason for the lasting success of the adoptive scheme of succession lay more with the fact that none but the last had a natural heir.

The last two emperors of the "Five Good Emperors" and

Commodus are also called

Antonines.

96–98: Nerva

After his accession, Nerva set a new tone: he released those imprisoned for treason, banned future prosecutions for treason, restored much confiscated property, and involved the Roman Senate in his rule. He probably did so as a means to remain relatively popular and therefore alive, but this did not completely aid him. Support for Domitian in the army remained strong, and in October 97 the Praetorian Guard laid siege to the Imperial Palace on the

Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; la, Collis Palatium or Mons Palatinus; it, Palatino ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city and has been called "the first nucleus of the Roman Empire." ...

and took Nerva hostage. He was forced to submit to their demands, agreeing to hand over those responsible for Domitian's death and even giving a speech thanking the rebellious Praetorians. Nerva then adopted Trajan, a commander of the armies on the German frontier, as his successor shortly thereafter in order to bolster his own rule.

Casperius Aelianus

Casperius Aelianus who served as Praetorian Prefect under the emperors Domitian and Nerva, was a Praetorian Prefect loyal to the Roman Emperor Domitian, the last of the Flavian dynasty. After Domitian's murder and the ascension of the Emperor ...

, the Guard Prefect responsible for the mutiny against Nerva, was later executed under Trajan.

98–117: Trajan

Upon his accession to the throne, Trajan prepared and launched

a carefully planned military invasion in

Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus ...

, a region north of the lower Danube whose inhabitants the Dacians had long been an opponent to Rome. In 101, Trajan personally crossed the Danube and defeated the armies of the Dacian king

Decebalus at the

Battle of Tapae. The emperor decided not to press on towards a final conquest as his armies needed reorganisation, but he did impose very hard peace conditions on the Dacians. At Rome, Trajan was received as a hero and he took the name of ''Dacicus'', a title that appears on his coinage of this period.

Decebalus complied with the terms for a time, but before long he began inciting revolt. In 105 Trajan once again invaded and after a yearlong invasion ultimately defeated the Dacians by conquering their capital,

Sarmizegetusa Regia

Sarmizegetusa Regia, also Sarmisegetusa, Sarmisegethusa, Sarmisegethuza, Ζαρμιζεγεθούσα (''Zarmizegethoúsa'') or Ζερμιζεγεθούση (''Zermizegethoúsē''), was the capital and the most important military, religious an ...

. King Decebalus, cornered by the Roman cavalry, eventually committed suicide rather than being captured and humiliated in Rome. The conquest of Dacia was a major accomplishment for Trajan, who ordered 123 days of celebration throughout the empire. He also constructed

Trajan's Column

Trajan's Column ( it, Colonna Traiana, la, Columna Traiani) is a Roman triumphal column in Rome, Italy, that commemorates Roman emperor Trajan's victory in the Trajan's Dacian Wars, Dacian Wars. It was probably constructed under the supervision o ...

in the middle of

Trajan's Forum

Trajan's Forum ( la, Forum Traiani; it, Foro di Traiano) was the last of the Imperial fora to be constructed in ancient Rome. The architect Apollodorus of Damascus oversaw its construction.

History

This forum was built on the order of the empe ...

in Rome to glorify the victory.

In 112, Trajan was provoked by the decision of

Osroes I

Osroes I (also spelled Chosroes I or Khosrow I; xpr, 𐭇𐭅𐭎𐭓𐭅 ''Husrōw'') was a Parthian contender, who ruled the western portion of the Parthian Empire from 109 to 129, with a one-year interruption. For the whole of his reign he con ...

to put his own nephew

Axidares

Axidares or Ashkhadar also known as Exedares or Exedates (flourished second half of the 1st century & first half of the 2nd century, died 113) was a Parthian Prince who served as a Roman Client King of Armenia.

Axidares was one of the three son ...

on the throne of the

Kingdom of Armenia. The

Arsacid dynasty of Armenia was a branch of the Parthian royal family established in 54. Since then, the two great empires had shared hegemony of Armenia. The encroachment on the traditional Roman sphere of influence by Osroes ended the peace which had lasted for some 50 years.

Trajan first invaded Armenia. He deposed the king and annexed it to the Roman Empire. Then he turned south into Parthian territory in

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, taking the cities of

Babylon,

Seleucia and finally the capital of

Ctesiphon in 116, while suppressing the

Kitos War, a Jewish uprising across the eastern provinces. He continued southward to the

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

, whence he took

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

as a new province of the empire and lamented that he was too old to follow in the steps of

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

and continue his invasion eastward.

But he did not stop there. In 116, he captured the great city of

Susa

Susa ( ; Middle elx, 𒀸𒋗𒊺𒂗, translit=Šušen; Middle and Neo- elx, 𒋢𒋢𒌦, translit=Šušun; Neo-Elamite and Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼𒀭, translit=Šušán; Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼, translit=Šušá; fa, شوش ...

. He deposed the emperor Osroes I and put his own puppet ruler

Parthamaspates on the throne. Not until the reign of Heraclius would the Roman army push so far to the east, and Roman territory never again reached so far eastward. During his rule, the Roman Empire reached its greatest extent; it was quite possible for a Roman to travel from

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

to the Persian Gulf without leaving Roman territory.

117–138: Hadrian

Despite his own excellence as a military administrator, Hadrian's reign was marked more by the defence of the empire's vast territories, rather than major military conflicts. He surrendered Trajan's conquests in Mesopotamia, considering them to be indefensible. There was almost a war with

Vologases III of Parthia

Vologases III ( xpr, 𐭅𐭋𐭂𐭔 ''Walagash'') was king of the Parthian Empire from 110 to 147. He was the son and successor of Pacorus II ().

Vologases III's reign was marked by civil strife and warfare. At his ascension, he had to deal ...

around 121, but the threat was averted when Hadrian succeeded in negotiating a peace. Hadrian's army crushed the

Bar Kokhba revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt ( he, , links=yes, ''Mereḏ Bar Kōḵḇāʾ''), or the 'Jewish Expedition' as the Romans named it ( la, Expeditio Judaica), was a rebellion by the Jews of the Judea (Roman province), Roman province of Judea, led b ...

, a massive Jewish uprising in Judea (132–135).

Hadrian was the first emperor to extensively tour the provinces, donating money for local construction projects as he went. In Britain, he ordered the construction of a wall, the famous

Hadrian's Wall as well as various other such defences in

Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north ...

and

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in t ...

. His domestic policy was one of relative peace and prosperity.

138–161: Antoninus Pius

Antoninus Pius's reign was comparatively peaceful; there were several military disturbances throughout the Empire in his time, in

Mauretania

Mauretania (; ) is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It stretched from central present-day Algeria westwards to the Atlantic, covering northern present-day Morocco, and southward to the Atlas Mountains. Its native inhabitants, ...

,

Judaea, and amongst the

Brigantes in Britain, but none of them are considered serious. The unrest in Britain is believed to have led to the construction of the