History Of The Ottoman Empire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

File:Facial Chronicle - b.10, p.299 - Battle of Kosovo (1389).png, Battle of Kosovo (1389)

File:Nicopol final battle 1398.jpg, Battle of Nicopolis (1396)

File:Mehmet I honoraries miniature.jpg, Sultan

Part of the Ottoman territories in the Balkans (such as Thessaloniki, Macedonia and Kosovo) were temporarily lost after 1402, but were later recovered by

During this period in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottoman Empire entered a long period of conquest and expansion, extending its borders deep into Europe and North Africa. Conquests on land were driven by the discipline and innovation of the Ottoman military; and on the sea, the Ottoman Navy aided this expansion significantly. The navy also contested and protected key seagoing trade routes, in competition with the Italian city states in the

During this period in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottoman Empire entered a long period of conquest and expansion, extending its borders deep into Europe and North Africa. Conquests on land were driven by the discipline and innovation of the Ottoman military; and on the sea, the Ottoman Navy aided this expansion significantly. The navy also contested and protected key seagoing trade routes, in competition with the Italian city states in the

France was at war with the

France was at war with the

European states initiated efforts at this time to curb Ottoman control of the traditional overland trade routes between East Asia and Western Europe, which started with the

European states initiated efforts at this time to curb Ottoman control of the traditional overland trade routes between East Asia and Western Europe, which started with the  In southern Europe, a coalition of Catholic powers, led by

In southern Europe, a coalition of Catholic powers, led by  Changes in European military tactics and weaponry in the

Changes in European military tactics and weaponry in the

However, the 17th century was not an era of stagnation and decline, but a key period in which the Ottoman state and its structures began to adapt to new pressures and new realities, internal and external.

The

However, the 17th century was not an era of stagnation and decline, but a key period in which the Ottoman state and its structures began to adapt to new pressures and new realities, internal and external.

The  This period gave way to the highly significant

This period gave way to the highly significant

During this period threats to the Ottoman Empire were presented by the traditional foe—the Austrian Empire—as well as by a new foe—the rising Russian Empire. Certain areas of the Empire, such as

During this period threats to the Ottoman Empire were presented by the traditional foe—the Austrian Empire—as well as by a new foe—the rising Russian Empire. Certain areas of the Empire, such as  During the

During the

at the Other tentative reforms were also enacted:

Other tentative reforms were also enacted:

history magazine, issue of July 2011. ''"Sultan Abdülmecid: İlklerin Padişahı"'', pages 46–50. (Turkish) guarantees to ensure the Ottoman subjects perfect security for their lives, honour and property; the introduction of the first Ottoman paper The Ottoman Ministry of Post was established in Istanbul on 23 October 1840.PTT Chronology

The Ottoman Ministry of Post was established in Istanbul on 23 October 1840.PTT Chronology

The first post office was the ''Postahane-i Amire'' near the courtyard of the Yeni Mosque. In 1876 the first international mailing network between Istanbul and the lands beyond the vast Ottoman Empire was established. In 1901 the first money transfers were made through the post offices and the first cargo services became operational.

history magazine, issue of July 2011. ''"Sultan Abdülmecid: İlklerin Padişahı"'', page 49. (Turkish) began on 9 August 1847.Türk Telekom: History

In 1855 the Ottoman telegraph network became operational and the Telegraph Administration was established. In 1871 the Ministry of Post and the Telegraph Administration were merged, becoming the Ministry of Post and Telegraph. In July 1881 the first telephone circuit in Istanbul was established between the Ministry of Post and Telegraph in the Soğukçeşme quarter and the Postahane-i Amire in the Yenicami quarter. On 23 May 1909, the first manual

The war caused an exodus of the

The war caused an exodus of the

The rise of nationalism swept through many countries during the 19th century, and it affected territories within the Ottoman Empire. A burgeoning

The rise of nationalism swept through many countries during the 19th century, and it affected territories within the Ottoman Empire. A burgeoning

The

The

The Ottoman Empire had long been the "

The Ottoman Empire had long been the "

In 1915, as the Russian Caucasus Army continued to advance in eastern Anatolia with the help of Armenian volunteer units from the

In 1915, as the Russian Caucasus Army continued to advance in eastern Anatolia with the help of Armenian volunteer units from the

File:Blue mosque2.jpg, The Blue Mosque

A Brief History of Osman Ghazi

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

was founded c. 1299 by Osman I

Osman I or Osman Ghazi ( ota, عثمان غازى, translit= ʿOsmān Ġāzī; tr, I. Osman or ''Osman Gazi''; died 1323/4), sometimes transliterated archaically as Othman, was the founder of the Ottoman Empire (first known as the Ottoman Bey ...

as a small bey

Bey ( ota, بك, beğ, script=Arab, tr, bey, az, bəy, tk, beg, uz, бек, kz, би/бек, tt-Cyrl, бәк, translit=bäk, cjs, пий/пек, sq, beu/bej, sh, beg, fa, بیگ, beyg/, tg, бек, ar, بك, bak, gr, μπέης) is ...

lik in northwestern Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

just south of the Byzantine capital Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. The Ottomans first crossed into Europe in 1352, establishing a permanent settlement at Çimpe Castle on the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

in 1354 and moving their capital to Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

(Adrianople) in 1369. At the same time, the numerous small Turkic states in Asia Minor were assimilated into the budding Ottoman sultanate through conquest or declarations of allegiance.

As Sultan Mehmed II

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

conquered Constantinople (today named Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

) in 1453, the state grew into a mighty empire, expanding deep into Europe, northern Africa and the Middle East. With most of the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

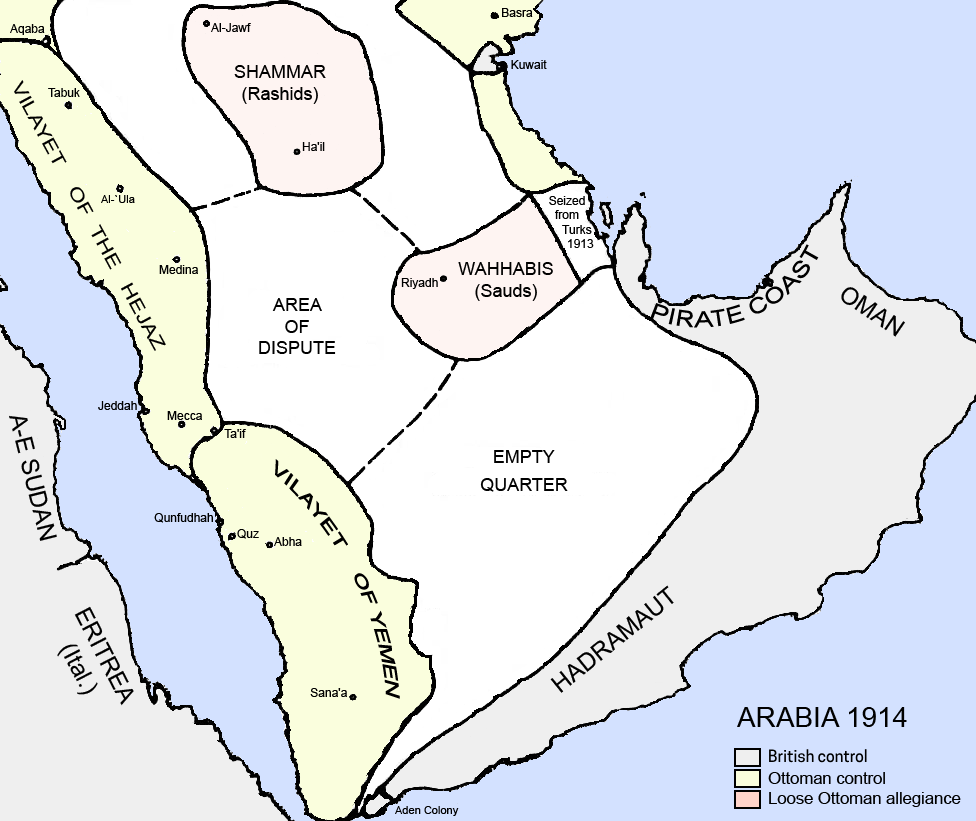

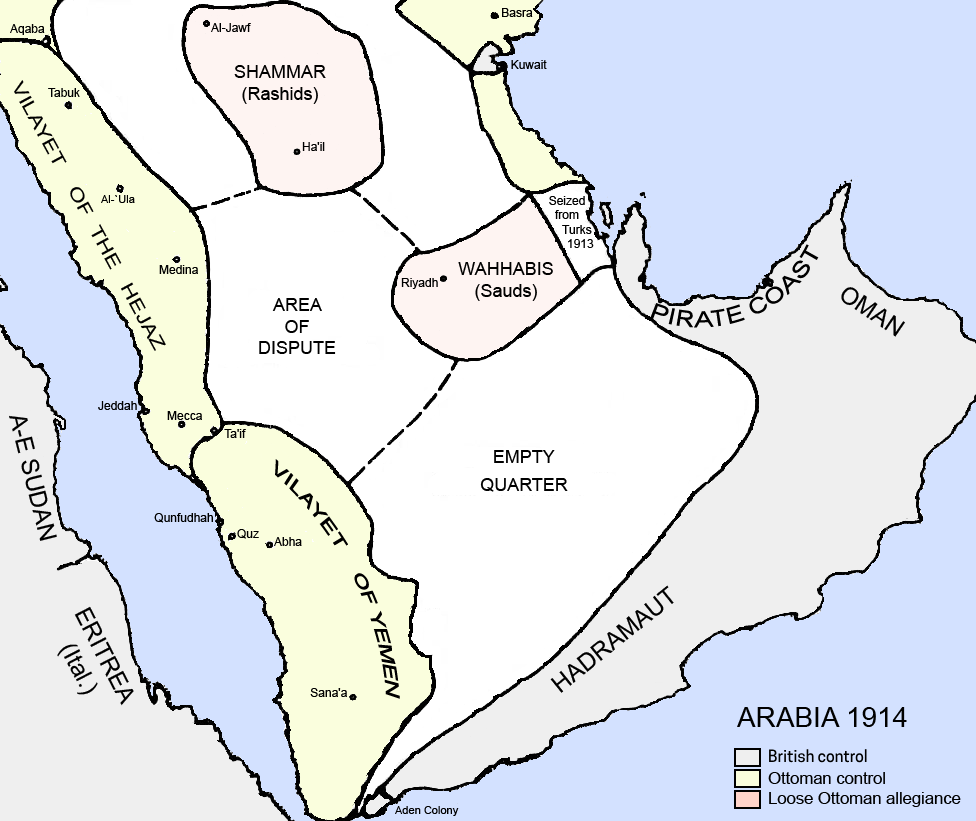

under Ottoman rule by the mid-16th century, Ottoman territory increased exponentially under Sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite last ...

, who assumed the Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

in 1517 as the Ottomans turned east and conquered western Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

, Egypt, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

and the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, among other territories. Within the next few decades, much of the North African coast (except Morocco) became part of the Ottoman realm.

The empire reached its apex under Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ� ...

in the 16th century, when it stretched from the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Persis, Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a Mediterranean sea (oceanography), me ...

in the east to Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

in the west, and from Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

in the south to Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

and parts of Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

in the north. According to the Ottoman decline thesis

The Ottoman decline thesis or Ottoman decline paradigm ( tr, Osmanlı Gerileme Tezi) is an obsolete

*

*

*

*

* Leslie Peirce, "Changing Perceptions of the Ottoman Empire: the Early Centuries," ''Mediterranean Historical Review'' 19/1 (20 ...

, Suleiman's reign was the zenith of the Ottoman classical period, during which Ottoman culture, arts, and political influence flourished. The empire reached its maximum territorial extent in 1683, on the eve of the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna; pl, odsiecz wiedeńska, lit=Relief of Vienna or ''bitwa pod Wiedniem''; ota, Beç Ḳalʿası Muḥāṣarası, lit=siege of Beç; tr, İkinci Viyana Kuşatması, lit=second siege of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mou ...

.

From 1699 onwards, the Ottoman Empire began to lose territory over the course of the next two centuries due to internal stagnation, costly defensive wars, European colonialism, and nationalist revolts among its multiethnic subjects. In any case, decline was evident to the empire's leaders by the early 19th century, and numerous administrative reforms were implemented in an attempt to forestall the decay of the empire, with varying degrees of success. The gradual weakening of the Ottoman Empire gave rise to the Eastern Question in the mid-19th century.

The empire came to an end in the aftermath of its defeat in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, when its remaining territory was partitioned by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

. The sultanate was officially abolished by the Government of the Turkish Grand National Assembly in Ankara on 1 November 1922 following the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

. Throughout its more than 600 years of existence, the Ottoman Empire has left a profound legacy in the Middle East and Southeast Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia (al ...

, as can be seen in the customs, culture, and cuisine of the various countries that were once part of its realm.

Ottoman etiology

With the end of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, questions arose in a geopolitical and historical context about the reasons for the emergence and decline of the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

, their empire and how both were defined. On the eve of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the geographical position and geopolitical weight of Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

, the major historical heir to the Ottoman Empire, gave the issues weight as propaganda. The first item on the agenda of the Tehran conference

The Tehran Conference (codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embassy i ...

was the issue of Turkey's participation in World War II by the end of 1943.

Formulable theses

Those about the emergence of the Ottoman Empire

#Ghaza thesis

The Ghaza or Ghazi thesis (from ota, غزا, ''ġazā'', "holy war," or simply "raid") is a historical paradigm first formulated by Paul Wittek which has been used to interpret the nature of the Ottoman Empire during the earliest period of i ...

— it is formulated first, but it is the most criticized and politicized. The thesis most clearly advocates the ethnic pan-Turkic principle. It was developed by Paul Wittek

Paul Wittek (11 January 1894, Baden bei Wien — 13 June 1978, Eastcote, Middlesex) was an Austrian Orientalist and historian. His 1938 thesis on the rise of the Ottoman Empire, known as the '' Ghazi thesis'', argues that the Ottoman's ''raison d ...

;

# Renegade thesis — represented in studies, articles and books by various authors. It is based on numerous eyewitness accounts. It is supplemented by the hypothesis of the geographical and to some extent civilizational succession of the Ottoman Empire (Rûm

Rūm ( ar, روم , collective; singulative: Rūmī ; plural: Arwām ; fa, روم Rum or Rumiyān, singular Rumi; tr, Rûm or , singular ), also romanized as ''Roum'', is a derivative of the Aramaic (''rhπmÈ'') and Parthian (''frwm'') te ...

) by the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

;

# Socio-economic thesis — the newest and most modern, sustained in the traditions of Marxist historiography

Marxist historiography, or historical materialist historiography, is an influential school of historiography. The chief tenets of Marxist historiography include the centrality of social class, social relations of production in class-divided soci ...

. The thesis is found in various articles and studies. It is based on the aftermath of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

and the legacy of the Byzantine civil war

This is a list of civil wars or other internal civil conflicts fought during the history of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire (330–1453). The definition of organized civil unrest is any conflict that was fought within the borders of the By ...

s.

Those about the decline of the Ottoman Empire

# Classic thesis — as a result of theRusso-Turkish War (1768–1774)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774 was a major armed conflict that saw Russian arms largely victorious against the Ottoman Empire. Russia's victory brought parts of Moldavia, the Yedisan between the rivers Bug and Dnieper, and Crimea into the ...

with the subsequent Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca ( tr, Küçük Kaynarca Antlaşması; russian: Кючук-Кайнарджийский мир), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on 21 July 1774, in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kayna ...

. Previously marked by the beginning of the reign of Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

, the writing of "Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya

''Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya'' ( Original Cyrillic: Истори́ѧ славѣноболгарскаѧ corrected from Їстори́ѧ славѣноболгарскаѧ; ) is a book by Bulgarian scholar and clergyman Saint Paisius of Hilen ...

" and the death of Koca Ragıp Pasha

Koca Mehmet Ragıp Pasha (1698–1763) was an Ottoman statesman who served as a civil servant before 1744 as the provincial governor of Egypt from 1744 to 1748 and Grand Vizier from 1757 to 1763. He was also known as a poet. His epithet ''Ko ...

;

# Ottoman decline thesis

The Ottoman decline thesis or Ottoman decline paradigm ( tr, Osmanlı Gerileme Tezi) is an obsolete

*

*

*

*

* Leslie Peirce, "Changing Perceptions of the Ottoman Empire: the Early Centuries," ''Mediterranean Historical Review'' 19/1 (20 ...

— now-controversial thesis clearly formulated for the first time in 1958 by Bernard Lewis

Bernard Lewis, (31 May 1916 – 19 May 2018) was a British American historian specialized in Oriental studies. He was also known as a public intellectual and political commentator. Lewis was the Cleveland E. Dodge Professor Emeritus of Near E ...

. Aligns with Koçi Bey's risalets, but arguably ignores the Köprülü era

The Köprülü era ( tr, Köprülüler Devri) (c. 1656–1703) was a period in which the Ottoman Empire's politics were frequently dominated by a series of grand viziers from the Köprülü family. The Köprülü era is sometimes more narrowl ...

and its reform of the Ottoman state, economy and navy heading into the 18th century;

# Neoclassical thesis — to some extent it unites the previous ones about the beginning of the Ottoman decline, which are divided even nearly two centuries in time. The beginning of the end was marked by the Treaty of Karlowitz

The Treaty of Karlowitz was signed in Karlowitz, Military Frontier of Archduchy of Austria (present-day Sremski Karlovci, Serbia), on 26 January 1699, concluding the Great Turkish War of 1683–1697 in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated by the ...

, the Edirne event

The Edirne Incident ( ota, Edirne Vaḳʿası, script=Latn) was a janissary revolt that began in Constantinople (now Istanbul) in 1703. The revolt was a reaction to the consequences of the Treaty of Karlowitz and Sultan Mustafa II's absence fro ...

and the reign of Ahmed III

Ahmed III ( ota, احمد ثالث, ''Aḥmed-i sālis'') was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and a son of Sultan Mehmed IV (r. 1648–1687). His mother was Gülnuş Sultan, originally named Evmania Voria, who was an ethnic Greek. He was born at H ...

.

Rise of the Ottoman Empire (1299–1453)

With the demise of theSeljuk Seljuk or Saljuq (سلجوق) may refer to:

* Seljuk Empire (1051–1153), a medieval empire in the Middle East and central Asia

* Seljuk dynasty (c. 950–1307), the ruling dynasty of the Seljuk Empire and subsequent polities

* Seljuk (warlord) (di ...

Sultanate of Rum

fa, سلجوقیان روم ()

, status =

, government_type = Hereditary monarchyTriarchy (1249–1254)Diarchy (1257–1262)

, year_start = 1077

, year_end = 1308

, p1 = By ...

during 12th to 13th century, Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

was divided into a patchwork of independent states, the so-called Anatolian Beyliks

Anatolian beyliks ( tr, Anadolu beylikleri, Ottoman Turkish: ''Tavâif-i mülûk'', ''Beylik'' ) were small principalities (or petty kingdoms) in Anatolia governed by beys, the first of which were founded at the end of the 11th century. A secon ...

. For the next few centuries, these Beyliks were under the sovereignty of Mongolians and their Iranian Kingdom Ilkhanids. This accounts for the Persian nature of the later Ottomans. By 1300, a weakened Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

had lost most of its Anatolian provinces to these Turkish principalities. One of the beyliks was led by Osman I

Osman I or Osman Ghazi ( ota, عثمان غازى, translit= ʿOsmān Ġāzī; tr, I. Osman or ''Osman Gazi''; died 1323/4), sometimes transliterated archaically as Othman, was the founder of the Ottoman Empire (first known as the Ottoman Bey ...

(d. 1323/4), from which the name Ottoman is derived, son of Ertuğrul

Ertuğrul or Ertuğrul Gazi ( ota, ارطغرل, Erṭoġrıl; tk, ; died ) was a 13th century bey, who was the father of Osman I. Little is known about Ertuğrul's life. According to Ottoman tradition, he was the son of Suleyman Shah, the ...

, around Eskişehir

Eskişehir ( , ; from "old" and "city") is a city in northwestern Turkey and the capital of the Eskişehir Province. The urban population of the city is 898,369 with a metropolitan population of 797,708. The city is located on the banks of the ...

in western Anatolia. In the foundation myth expressed in the story known as "Osman's Dream

''Osman's Dream'' is a mythological story about the life of Osman I, founder of the Ottoman Empire. The story describes a dream experienced by Osman while staying in the home of a religious figure, Sheikh Edebali, in which he sees a metaphorical ...

", the young Osman was inspired to conquest by a prescient vision of empire (according to his dream, the empire is a big tree whose roots spread through three continents and whose branches cover the sky).Lord Kinross, ''The Ottoman Centuries'' (Morrow Quill Publishers: New York, 1977) p. 24. According to his dream the tree, which was Osman's Empire, issued four rivers from its roots, the Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

, the Euphrates

The Euphrates () is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Tigris–Euphrates river system, Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia ( ''the land between the rivers'') ...

, the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

and the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

. Additionally, the tree shaded four mountain ranges, the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

, the Taurus

Taurus is Latin for 'bull' and may refer to:

* Taurus (astrology), the astrological sign

* Taurus (constellation), one of the constellations of the zodiac

* Taurus (mythology), one of two Greek mythological characters named Taurus

* '' Bos tauru ...

, the Atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geographic ...

and the Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

ranges. During his reign as Sultan, Osman I extended the frontiers of Turkish settlement toward the edge of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

.

During this period, a formal Ottoman government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were j ...

was created whose institutions would change drastically over the life of the empire.

In the century after the death of Osman I, Ottoman rule began to extend over the Eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. Osman's son, Orhan

Orhan Ghazi ( ota, اورخان غازی; tr, Orhan Gazi, also spelled Orkhan, 1281 – March 1362) was the second bey of the Ottoman Beylik from 1323/4 to 1362. He was born in Söğüt, as the son of Osman I.

In the early stages of his re ...

, captured the city of Bursa

( grc-gre, Προῦσα, Proûsa, Latin: Prusa, ota, بورسه, Arabic:بورصة) is a city in northwestern Turkey and the administrative center of Bursa Province. The fourth-most populous city in Turkey and second-most populous in the ...

in 1326 and made it the new capital of the Ottoman state. The fall of Bursa meant the loss of Byzantine control over Northwestern Anatolia.

After securing their flank in Asia Minor, the Ottomans then crossed into Europe from 1352 onwards; within a decade, almost all of Thrace had been conquered by the Ottomans, cutting off Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

from its Balkan hinterlands. The Ottoman capital was moved to Adrianople Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

in 1369. The important city of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

was captured from the Venetians in 1387. The Ottoman victory at Kosovo in 1389 effectively marked the end of Serbian power in the region, paving the way for Ottoman expansion into Europe. The Battle of Nicopolis in 1396, widely regarded as the last large-scale crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were i ...

of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, failed to stop the advance of the victorious Ottoman Turks. With the extension of Turkish dominion into the Balkans, the strategic conquest of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

became a crucial objective. The Empire controlled nearly all former Byzantine lands

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

surrounding the city, but the Byzantines were temporarily relieved when Timur

Timur ; chg, ''Aqsaq Temür'', 'Timur the Lame') or as ''Sahib-i-Qiran'' ( 'Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction'), his epithet. ( chg, ''Temür'', 'Iron'; 9 April 133617–19 February 1405), later Timūr Gurkānī ( chg, ''Temür Kür ...

invaded Anatolia in the Battle of Ankara

The Battle of Ankara or Angora was fought on 20 July 1402 at the Çubuk plain near Ankara, between the forces of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I and the Emir of the Timurid Empire, Timur. The battle was a major victory for Timur, and it led to the ...

in 1402. He took Sultan Bayezid I

Bayezid I ( ota, بايزيد اول, tr, I. Bayezid), also known as Bayezid the Thunderbolt ( ota, link=no, یلدیرم بايزيد, tr, Yıldırım Bayezid, link=no; – 8 March 1403) was the Ottoman Sultan from 1389 to 1402. He adopted ...

as a prisoner. The capture of Bayezid I threw the Turks into disorder. The state fell into a civil war that lasted from 1402 to 1413, as Bayezid's sons fought over succession. It ended when Mehmed I

Mehmed I ( 1386 – 26 May 1421), also known as Mehmed Çelebi ( ota, چلبی محمد, "the noble-born") or Kirişçi ( el, Κυριτζής, Kyritzis, "lord's son"), was the Ottoman sultan from 1413 to 1421. The fourth son of Sultan Bayezid ...

emerged as the sultan and restored Ottoman power, bringing an end to the Interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

.

Mehmed I

Mehmed I ( 1386 – 26 May 1421), also known as Mehmed Çelebi ( ota, چلبی محمد, "the noble-born") or Kirişçi ( el, Κυριτζής, Kyritzis, "lord's son"), was the Ottoman sultan from 1413 to 1421. The fourth son of Sultan Bayezid ...

. Ottoman miniature, 1413-1421

File:Chelebowski_varna.jpg, Battle of Varna (1444)

Murad II

Murad II ( ota, مراد ثانى, Murād-ı sānī, tr, II. Murad, 16 June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1421 to 1444 and again from 1446 to 1451.

Murad II's reign was a period of important economic deve ...

between the 1430s and 1450s. On 10 November 1444, Murad II defeated the Hungarian, Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

and Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and so ...

n armies under Władysław III of Poland

Władysław III (31 October 1424 – 10 November 1444), also known as Ladislaus of Varna, was King of Poland and the Supreme Duke (''Supremus Dux'') of Grand Duchy of Lithuania from 1434 as well as King of Hungary and Croatia from 1440 until h ...

(also King of Hungary) and János Hunyadi

John Hunyadi (, , , ; 1406 – 11 August 1456) was a leading Hungarian military and political figure in Central and Southeastern Europe during the 15th century. According to most contemporary sources, he was the member of a noble family of ...

at the Battle of Varna

The Battle of Varna took place on 10 November 1444 near Varna in eastern Bulgaria. The Ottoman Army under Sultan Murad II (who did not actually rule the sultanate at the time) defeated the Hungarian–Polish and Wallachian armies commanded by ...

, which was the final battle of the Crusade of Varna

The Crusade of Varna was an unsuccessful military campaign mounted by several European leaders to check the expansion of the Ottoman Empire into Central Europe, specifically the Balkans between 1443 and 1444. It was called by Pope Eugene IV on ...

. Four years later, János Hunyadi prepared another army (of Hungarian and Wallachian forces) to attack the Turks, but was again defeated by Murad II at the Second Battle of Kosovo

The Second Battle of Kosovo ( Hungarian: ''második rigómezei csata'', Turkish: ''İkinci Kosova Muharebesi'') (17–20 October 1448) was a land battle between a Hungarian-led Crusader army and the Ottoman Empire at Kosovo Polje. It was ...

in 1448.

The son of Murad II, Mehmed the Conqueror

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

, reorganized the state and the military, and demonstrated his martial prowess by capturing Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

on 29 May 1453, at the age of 21.

Classical Age (1453–1566)

The Ottoman conquest ofConstantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

in 1453 by Mehmed II cemented the status of the Empire as the preeminent power in southeastern Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. After taking Constantinople, Mehmed met with the Orthodox patriarch, Gennadios and worked out an arrangement in which the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

, in exchange for being able to maintain its autonomy and land, accepted Ottoman authority.Stone, Norman "Turkey in the Russian Mirror" pages 86–100 from ''Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy'' edited by Mark & Ljubica Erickson, Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London, 2004 page 94 Because of bad relations between the latter Byzantine Empire and the states of western Europe as epitomized by Loukas Notaras

Loukas Notaras ( el, Λουκᾶς Νοταρᾶς; 5 April 1402 – 3 June 1453) was a Byzantine statesman who served as the last '' megas doux'' or grand Duke (commander-in-chief of the Byzantine navy) and the last '' mesazon'' (chief minister) ...

's famous remark "Better the Sultan's turban than the Cardinal's Hat", the majority of the Orthodox population accepted Ottoman rule as preferable to Venetian rule.

Upon making Constantinople (present-day Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

) the new capital of the Ottoman Empire in 1453, Mehmed II assumed the title of ''Kayser-i Rûm'' (literally ''Caesar Romanus'', i.e. Roman Emperor.) In order to consolidate this claim, he would launch a campaign to conquer Rome, the western capital of the former Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

. To this aim he spent many years securing positions on the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

, such as in Albania Veneta

Venetian Albania ( vec, Albania vèneta, it, Albania Veneta, Serbian and Montenegrin: Млетачка Албанија / ''Mletačka Albanija'', ) was the official term for several possessions of the Republic of Venice in the southeastern Adria ...

, and then continued with the Ottoman invasion of Otranto

The Ottoman invasion of Otranto occurred between 1480 and 1481 at the Italian city of Otranto in Apulia, southern Italy. Forces of the Ottoman Empire invaded and laid siege to the city, they captured it on 11 August 1480 establishing the firs ...

and Apulia

it, Pugliese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographic ...

on 28 July 1480. The Turks stayed in Otranto

Otranto (, , ; scn, label= Salentino, Oṭṛàntu; el, label=Griko, Δερεντό, Derentò; grc, Ὑδροῦς, translit=Hudroûs; la, Hydruntum) is a coastal town, port and ''comune'' in the province of Lecce (Apulia, Italy), in a fertil ...

and its surrounding areas for nearly a year, but after Mehmed II's death on 3 May 1481, plans for penetrating deeper into the Italian peninsula with fresh new reinforcements were given up on and cancelled and the remaining Ottoman troops sailed back to the east of the Adriatic Sea.

During this period in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottoman Empire entered a long period of conquest and expansion, extending its borders deep into Europe and North Africa. Conquests on land were driven by the discipline and innovation of the Ottoman military; and on the sea, the Ottoman Navy aided this expansion significantly. The navy also contested and protected key seagoing trade routes, in competition with the Italian city states in the

During this period in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottoman Empire entered a long period of conquest and expansion, extending its borders deep into Europe and North Africa. Conquests on land were driven by the discipline and innovation of the Ottoman military; and on the sea, the Ottoman Navy aided this expansion significantly. The navy also contested and protected key seagoing trade routes, in competition with the Italian city states in the Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

, Aegean and Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

seas and the Portuguese in the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

and Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

.

The state also flourished economically due to its control of the major overland trade routes between Europe and Asia.

The Empire prospered under the rule of a line of committed and effective Sultans

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it c ...

. Sultan Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite last ...

(1512–1520) dramatically expanded the Empire's eastern and southern frontiers by defeating Shah Ismail

Ismail I ( fa, اسماعیل, Esmāʿīl, ; July 17, 1487 – May 23, 1524), also known as Shah Ismail (), was the founder of the Safavid dynasty of Iran, ruling as its King of Kings (''Shahanshah'') from 1501 to 1524. His reign is often c ...

I of Safavid

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, in 1514 at the Battle of Chaldiran

The Battle of Chaldiran ( fa, جنگ چالدران; tr, Çaldıran Savaşı) took place on 23 August 1514 and ended with a decisive victory for the Ottoman Empire over the Safavid Empire. As a result, the Ottomans annexed Eastern Anatolia an ...

. During the summer of 1515, Selim I completed the conquest of Anatolia which diminished the buffer region between the Ottomans and the Mamluks of Egypt. This allowed the Ottoman's to filter into Mamluk territory with their navy arriving from 1516-1517. They entered Egypt in January 1517. Selim I established Ottoman rule in Egypt, and created a naval presence on the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

. After this Ottoman expansion, a competition started between the Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the l ...

and the Ottoman Empire to become the dominant power in the region. This conquest ended with the execution of Tuman Bay II

Al-Ashraf Abu Al-Nasr Tuman bay ( ar, الأشرف أبو النصر طومان باي), better known as Tuman bay II ( ar, طومان باي), (c. 1476 – 15 April 1517) was the last Sultan of Egypt before the country's conquest by the Ottoman ...

and resulted with the Ottoman Empire doubling in size.

The Ottoman takeover of Egypt caused Europeans to lose their spice trade routes. Ottomans decided to build their navy to defend themselves against Europe and gain new lands. Amir of Algeria asked for Ottoman aid against the Spaniards. By 1518, Algeria was an Ottoman province.

Selim's successor, Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ� ...

(1520–1566), further expanded upon Selim's conquests. He restarted the war against Hungary in 1521, capturing Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

; Suleiman conquered the southern and central parts of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

. (The western, northern and northeastern parts remained independent.)

By 1522, the Ottomans secured total dominance of the eastern Mediterranean Sea after having victory in the conquest of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

.

France was at war with the

France was at war with the Habsburg Dynasty

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

over control of Italy. France lost which caused the up rise of the Franco-Turkish alliance. To get to Habsburg territory, the Ottomans needed to go through Hungary and attacked the town of Mohács

Mohács (; Croatian and Bunjevac: ''Mohač''; german: Mohatsch; sr, Мохач; tr, Mohaç) is a town in Baranya County, Hungary, on the right bank of the Danube.

Etymology

The name probably comes from the Slavic ''*Mъchačь'',''*Mocháč'': ...

. After Suleiman's victory in the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

in 1526, he established Turkish rule in the territory of present-day Hungary (except the western region) and other Central European territories, (See also: Ottoman–Hungarian Wars

The Ottoman–Hungarian Wars were a series of battles between the Ottoman Empire and the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. Following the Byzantine Civil War, the Ottoman capture of Gallipoli, and the decisive Battle of Kosovo, the Ottoman Empire ...

). After this victory, he soon won again in the siege of Buda in 1526, only to lose it to Ferdinand I in 1527. Suleiman then joined forces with John Zapolya to regain the Buda capital. After, he laid siege to Vienna in 1529, but failed to take the city after the onset of winter forced his retreat. Shortly after, Ferdinand I started the 'Little Wars' in retaliation to Sulieman for not stopping support towards Zapolya.

In 1532, he made another attack on Vienna, but was repulsed in the Siege of Güns

The siege of Kőszeg ( hu, Kőszeg ostroma) or siege of Güns ( tr, Güns Kuşatması), also known as German Campaign ( tr, Alman Seferi) was a siege of Kőszeg (german: Güns)During the Ottoman–Habsburg wars, the small border fort was called G ...

, south of the city at the fortress of Güns.Thompson (1996), p. 442Ágoston and Alan Masters (2009), p. 583 In the other version of the story, the city's commander, Nikola Jurišić

Baron Nikola Jurišić ( hu, Jurisich Miklós; – 1545) was a Croatian nobleman, soldier, and diplomat.

Early life

Jurišić was born in Senj, Croatia.

He is first mentioned in 1522 as an officer of Ferdinand I of Habsburg's troops deployed ...

, was offered terms for a nominal surrender.Turnbull (2003), p. 51. However, Suleiman withdrew at the arrival of the August rains and did not continue towards Vienna as previously planned, but turned homeward instead.Vambery, p. 298

In 1533, Sulieman signed the Treaty of Constantinople with the Habsburgs after the Safavids started rebelling against the Ottomans. The Habsburgs attacked the Ottomans on land and sea in 1537 at the siege of Osijek, where Ottoman supply lines were. The Ottomans won this battle along with the Battle of Preveza

The Battle of Preveza was a naval battle that took place on 28 September 1538 near Preveza in Ionian Sea in northwestern Greece between an Ottoman fleet and that of a Holy League assembled by Pope Paul III. It occurred in the same area in ...

, causing the Holy League to diminish and the Venetians to make peace with the Ottomans.

In 1538, Hayreddin Barbarossa

Hayreddin Barbarossa ( ar, خير الدين بربروس, Khayr al-Din Barbarus, original name: Khiḍr; tr, Barbaros Hayrettin Paşa), also known as Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1478 – 4 July 1546), was an Ot ...

, Ottoman Navy Admiral, met the Holy League at the gulf of Preveza. The Ottomans were outnumbered in this navy battle, but won after Andrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; lij, Drîa Döia ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was a Genoese statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

As the ruler of Genoa, Doria reformed the Repu ...

, Prince of Melfi

The title of Prince of Melfi is an Italian noble title that was granted to Andrea Doria, a famous admiral, statesman and condottiere from the Republic of Genoa, in 1531 along with the lands of the country of Melfi by Charles V. The title was handed ...

, retreated.

In 1541, Ferdinand I attacked the capital of Buda again, but was met by the Ottomans shortly after starting the battle. Sulieman rewarded his success by giving himself Buda and the surrounding territories.

After further advances by the Turks in 1543, the Habsburg ruler Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "protection", "peace" (PIE "to love, to make peace") or alternatively "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "co ...

officially recognized Ottoman ascendancy in Hungary in 1547. During the reign of Suleiman, Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

, Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and so ...

and, intermittently, Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

, became tributary principalities of the Ottoman Empire. In the east, the Ottoman Turks took Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

from the Persians in 1535, gaining control of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

and naval access to the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Persis, Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a Mediterranean sea (oceanography), me ...

. By the end of Suleiman's reign, the Empire's population totaled about 15,000,000 people.L. Kinross, ''The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire'', p.206

Under Selim and Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ� ...

, the Empire became a dominant naval force, controlling much of the Mediterranean. The exploits of the Ottoman admiral Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha

Hayreddin Barbarossa ( ar, خير الدين بربروس, Khayr al-Din Barbarus, original name: Khiḍr; tr, Barbaros Hayrettin Paşa), also known as Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1478 – 4 July 1546), was an O ...

, who commanded the Ottoman Navy during Suleiman's reign, led to a number of military victories over Christian navies. Important naval victories of the Ottoman Empire in this period include the Battle of Preveza

The Battle of Preveza was a naval battle that took place on 28 September 1538 near Preveza in Ionian Sea in northwestern Greece between an Ottoman fleet and that of a Holy League assembled by Pope Paul III. It occurred in the same area in ...

(1538); Battle of Ponza (1552)

The Battle of Ponza (1552) was a naval battle that occurred near the Italian island of Ponza. The battle was fought between a Franco-Ottoman fleet under Dragut and a Genoese fleet commanded by Andrea Doria.''The Mediterranean and the Mediterran ...

; Battle of Djerba

The Battle of Djerba ( tr, Cerbe) took place in May 1560 near the island of Djerba, Tunisia. The Ottomans under Piyale Pasha's command overwhelmed a large joint Christian Alliance fleet, composed chiefly of Spanish, Papal, Genoese, Maltese, ...

(1560); conquest of Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

(in 1516

__NOTOC__

Year 1516 ( MDXVI) was a leap year starting on Tuesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

January–June

* January – Juan Díaz de Solís discovers the Río de la Plata (in future A ...

and 1529) and Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

(in 1534 and 1574

__NOTOC__

Year 1574 ( MDLXXIV) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

January–June

* February 23 – The fifth War of Religion against the Huguenots begins ...

) from Spain; conquest of Rhodes (1522) and Tripoli (1551) from the Knights of St. John

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

; capture of Nice (1543) from the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

; capture of Corsica (1553) from the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the Lat ...

; capture of the Balearic Islands (1558) from Spain; capture of Aden (1548), Muscat (1552) and Aceh (1565–67) from Portugal during the Indian Ocean expeditions; among others.

The conquests of Nice (1543) and Corsica (1553) occurred on behalf of France as a joint venture between the forces of the French king Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

and the Ottoman sultan Suleiman I, and were commanded by the Ottoman admirals Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha

Hayreddin Barbarossa ( ar, خير الدين بربروس, Khayr al-Din Barbarus, original name: Khiḍr; tr, Barbaros Hayrettin Paşa), also known as Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1478 – 4 July 1546), was an O ...

and Turgut Reis

Dragut ( tr, Turgut Reis) (1485 – 23 June 1565), known as "The Drawn Sword of Islam", was a Muslim Ottoman naval commander, governor, and noble, of Turkish or Greek descent. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extended ...

. A month prior to the siege of Nice, France supported the Ottomans with an artillery unit during the Ottoman conquest of Esztergom in 1543. France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and the Ottoman Empire, united by mutual opposition to Habsburg rule in both Southern and Central Europe, became strong allies during this period. The alliance was economic and military, as the sultans granted France the right of trade within the Empire without levy of taxation. By this time, the Ottoman Empire was a significant and accepted part of the European political sphere. It made a military alliance with France, the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

and the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

against Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain is a contemporary historiographical term referring to the huge extent of territories (including modern-day Spain, a piece of south-east France, eventually Portugal, and many other lands outside of the Iberian Peninsula) ruled be ...

, Italy and Habsburg Austria.

The Ottoman empire attempted to take control of Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, an island in the Mediterranean Sea near Italy, in order to aid them in future conquests. It was controlled by the fearsome Knights of Hospitaller and in 1551, the Turks attempted for the first time to take it over. Instead of gaining the island, the Ottomans had success with seizing Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

, a port city on the coast of today’s Libya. With this only being a partial failure, they tried one more time in 1565 and were defeated by the Knights once again.

Suleiman I policy of expansion throughout the Mediterranean basin was however halted in Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

in 1565. During a summer-long siege which was later to be known as the Siege of Malta, the Ottoman forces which numbered around 50,000 fought the Knights of St. John

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

and the Maltese garrison of 6000 men. Stubborn resistance by the Maltese led to the lifting of the siege in September. The unsuccessful siege (the Turks managed to capture the Isle of Gozo

Gozo (, ), Maltese: ''Għawdex'' () and in antiquity known as Gaulos ( xpu, 𐤂𐤅𐤋, ; grc, Γαῦλος, Gaúlos), is an island in the Maltese archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea. The island is part of the Republic of Malta. After t ...

together with Fort Saint Elmo

Fort Saint Elmo ( mt, Forti Sant'Iermu) is a star fort in Valletta, Malta. It stands on the seaward shore of the Sciberras Peninsula that divides Marsamxett Harbour from Grand Harbour, and commands the entrances to both harbours along with Fort ...

on the main island of Malta, but failed elsewhere and retreated) was the second and last defeat experienced by Suleiman the Magnificent after the likewise inconclusive first Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1529. Suleiman I died of natural causes in his tent during the Siege of Szigetvár

The siege of Szigetvár or the Battle of Szigeth (pronunciation: �siɡɛtvaːr hu, Szigetvár ostroma, hr, Bitka kod Sigeta; Sigetska bitka, tr, Zigetvar Kuşatması) was a siege of the fortress of Szigetvár, Kingdom of Hungary, that block ...

in 1566. The Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Soverei ...

in 1571 (which was triggered by the Ottoman capture of Venetian-controlled Cyprus in 1570) was another major setback for Ottoman naval supremacy in the Mediterranean Sea, despite the fact that an equally large Ottoman fleet was built in a short time and Tunisia was recovered from Spain in 1574.

As the 16th century progressed, Ottoman naval superiority was challenged by the growing sea powers of western Europe, particularly Portugal, in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Persis, Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a Mediterranean sea (oceanography), me ...

, Indian Ocean and the Spice Islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices ar ...

. With the Ottoman Turks blockading sea-lanes to the East and South, the European powers were driven to find another way to the ancient silk and spice routes, now under Ottoman control. On land, the Empire was preoccupied by military campaigns in Austria and Persia, two widely separated theatres of war. The strain of these conflicts on the Empire's resources, and the logistics of maintaining lines of supply and communication across such vast distances, ultimately rendered its sea efforts unsustainable and unsuccessful. The overriding military need for defence on the western and eastern frontiers of the Empire eventually made effective long-term engagement on a global scale impossible.

Transformation of the Ottoman Empire (1566–1700)

European states initiated efforts at this time to curb Ottoman control of the traditional overland trade routes between East Asia and Western Europe, which started with the

European states initiated efforts at this time to curb Ottoman control of the traditional overland trade routes between East Asia and Western Europe, which started with the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and reli ...

. Western European states began to avoid the Ottoman trade monopoly by establishing their own maritime routes to Asia through new discoveries at sea. The Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

discovery of the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

in 1488 initiated a series of Ottoman-Portuguese naval wars in the Indian Ocean throughout the 16th century. Economically, the Price Revolution

The Price Revolution, sometimes known as the Spanish Price Revolution, was a series of economic events that occurred between the second half of the 15th century and the first half of the 17th century, and most specifically linked to the high rate o ...

caused rampant inflation in both Europe and the Middle East. This had serious negative consequences at all levels of Ottoman society.

The expansion of Muscovite Russia

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: Великое княжество Московское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

under Ivan IV

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (russian: Ива́н Васи́льевич; 25 August 1530 – ), commonly known in English as Ivan the Terrible, was the grand prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and the first Tsar of all Russia from 1547 to 1584.

Ivan ...

(1533–1584) into the Volga and Caspian region at the expense of the Tatar khanates disrupted the northern pilgrimage and trade routes. A highly ambitious plan to counter this conceived by Sokollu Mehmed Pasha

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha ( ota, صوقوللى محمد پاشا, Ṣoḳollu Meḥmed Pașa, tr, Sokollu Mehmet Paşa; ; ; 1506 – 11 October 1579) was an Ottoman statesman most notable for being the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. Born in ...

, Grand Vizier under Selim II

Selim II ( Ottoman Turkish: سليم ثانى ''Selīm-i sānī'', tr, II. Selim; 28 May 1524 – 15 December 1574), also known as Selim the Blond ( tr, Sarı Selim) or Selim the Drunk ( tr, Sarhoş Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire ...

, in the shape of a Don-Volga canal (begun June 1569), combined with an attack on Astrakhan, failed, the canal being abandoned with the onset of winter. Henceforth the Empire returned to its existing strategy of utilizing the Crimean Khanate as its bulwark against Russia. In 1571, the Crimean khan Devlet I Giray

Devlet I Giray (1512–1577, r. 1551–1577, ; ', ) was a Crimean Khan. His long and eventful reign saw many highly significant historical events: the fall of Kazan to Russia in 1552, the fall of the Astrakhan Khanate to Russia in 1556, th ...

, supported by the Ottomans, burned Moscow. The next year, the invasion was repeated but repelled at the Battle of Molodi

The Battle of Molodi (Russian: Би́тва при Мóлодях) was one of the key battles of Ivan the Terrible's reign. It was fought near the village of Molodi, south of Moscow, in July–August 1572 between the 40,000–60,000-strong''� ...

. The Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate ( crh, , or ), officially the Great Horde and Desht-i Kipchak () and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary ( la, Tartaria Minor), was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to ...

continued to invade Eastern Europe in a series of slave raids

Slave raiding is a military raid for the purpose of capturing people and bringing them from the raid area to serve as slaves. Once seen as a normal part of warfare, it is nowadays widely considered a crime. Slave raiding has occurred since ant ...

, and remained a significant power in Eastern Europe and a threat to Muscovite Russia in particular until the end of the 17th century.

In southern Europe, a coalition of Catholic powers, led by

In southern Europe, a coalition of Catholic powers, led by Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

, formed an alliance to challenge Ottoman naval strength in the Mediterranean. Their victory over the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto (1571)

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Soverei ...

was a startling blow to the image of Ottoman invincibility. However, historians today stress the symbolic and not the strictly military significance of the battle, for within six months of the defeat a new Ottoman fleet of some 250 sail including eight modern galleass

Galleasses were military ships developed from large merchant galleys, and intended to combine galley speed with the sea-worthiness and artillery of a galleon. While perhaps never quite matching up to their full expectations, galleasses neverthel ...

esKinross, 272. had been built, with the shipyards of Istanbul turning out a new ship every day at the height of the construction. In discussions with a Venetian minister, the Ottoman Grand Vizier commented: "In capturing Cyprus from you, we have cut off one of your arms; in defeating our fleet you have merely shaved off our beard". The Ottoman naval recovery persuaded Venice to sign a peace treaty in 1573, and the Ottomans were able to expand and consolidate their position in North Africa. However, what could not be replaced were the experienced naval officers and sailors. The Battle of Lepanto was far more damaging to the Ottoman navy in sapping experienced manpower than the loss of ships, which were rapidly replaced.

By contrast, the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

frontier had settled into a reasonably permanent border, marked only by relatively minor battles concentrating on the possession of individual fortresses. The stalemate was caused by a stiffening of the Habsburg defences and reflected simple geographical limits: in the pre-mechanized age, Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

marked the furthest point that an Ottoman army could march from Istanbul during the early spring to late autumn campaigning season. It also reflected the difficulties imposed on the Empire by the need to support two separate fronts: one against the Austrians (see: Ottoman wars in Europe

A series of military conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and various European states took place from the Late Middle Ages up through the early 20th century. The earliest conflicts began during the Byzantine–Ottoman wars, waged in Anatolia in ...

), and the other against a rival Islamic state, the Safavid

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

s of Persia (see: Ottoman wars in Near East).

Changes in European military tactics and weaponry in the

Changes in European military tactics and weaponry in the military revolution

The Military Revolution is the theory that a series of radical changes in military strategy and tactics during the 16th and 17th centuries resulted in major lasting changes in governments and society. The theory was introduced by Michael Roberts i ...

caused the Sipahi

''Sipahi'' ( ota, سپاهی, translit=sipâhi, label=Persian, ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuk dynasty, Seljuks, and later the Ottoman Empire, including the land grant-holding (''timar'') provincial ''Timariots, timarli s ...

cavalry to lose military relevance. The Long War against Austria (1593–1606) created the need for greater numbers of infantry equipped with firearms. This resulted in a relaxation of recruitment policy and a significant growth in Janissary

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ( ...

corps numbers. Irregular sharpshooters (Sekban) were also recruited for the same reasons and on demobilization turned to brigandage in the Jelali revolts

The Celali rebellions ( tr, Celalî ayaklanmaları), were a series of rebellions in Anatolia of irregular troops led by bandit chiefs and provincial officials known as ''celalî'', ''celâli'', or ''jelālī'', against the authority of the Ottoman ...

(1595–1610), which engendered widespread anarchy in Anatolia in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. With the Empire's population reaching 30,000,000 people by 1600, shortage of land placed further pressure on the government.L. Kinross, ''The Ottoman Centuries'', p.281

However, the 17th century was not an era of stagnation and decline, but a key period in which the Ottoman state and its structures began to adapt to new pressures and new realities, internal and external.

The

However, the 17th century was not an era of stagnation and decline, but a key period in which the Ottoman state and its structures began to adapt to new pressures and new realities, internal and external.

The Sultanate of women

The Sultanate of Women ( Turkish: ''Kadınlar saltanatı'') was a period when wives and mothers of the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire exerted extraordinary political influence.

This phenomenon took place from roughly 1528-30 to 1715, beginning in ...

(1533–1656) was a period in which the political influence of the Imperial Harem

The Imperial Harem ( ota, حرم همايون, ) of the Ottoman Empire was the Ottoman sultan's harem – composed of the wives, servants (both female slaves and eunuchs), female relatives and the sultan's concubines – occupying a secluded po ...

was dominant, as the mothers of young sultans exercised power on behalf of their sons. This was not wholly unprecedented; Hürrem Sultan