The

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

(KMT) is a

Chinese political party that ruled

mainland China

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territories within Greater China. ...

from 1927 to 1949 prior to its

relocation to

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

as a result of the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

. The name of the party translates as "China's National People's Party" and was historically referred to as the Chinese Nationalists. The Party was initially founded on 23 August 1912, by

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

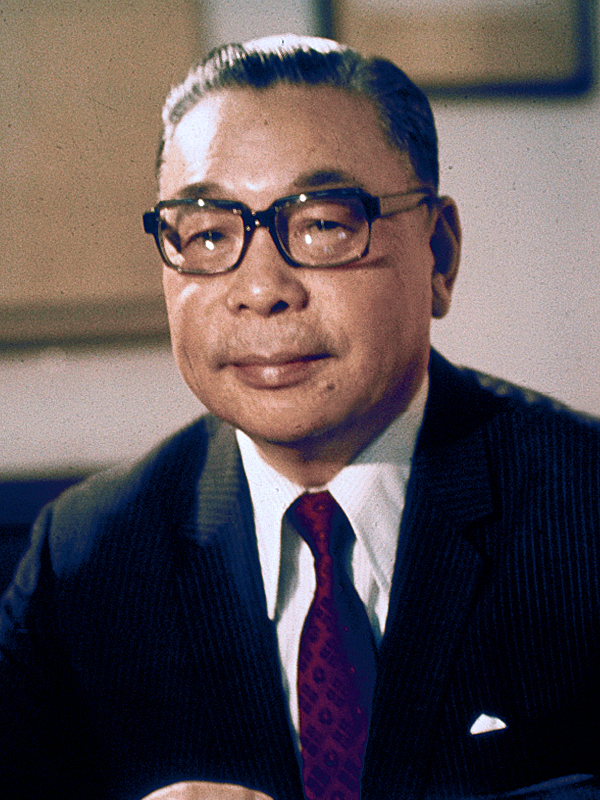

but dissolved in November 1913. It reformed on October 10th 1919, again led by Sun Yat-sen, and became the ruling party in China. After Sun's death, the party was dominated from 1927 to 1975 by

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

. After the KMT lost the civil war with the

Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victoriou ...

in 1949, the party

retreated to Taiwan and remains a major political party of the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

based in Taiwan.

Founded in 1912 by

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

, the KMT helped topple the

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

and promoted modernization along Western lines. The party played a significant part in the first Chinese first National Assembly where it was the majority party. However the KMT failed to achieve complete control. The post of president was given to

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. H ...

(1859–1916) as reward for his part in the revolution. Yuan Shikai abused his powers, overriding the constitution and creating strong tensions between himself and the other parties. In July 1913, the KMT staged a 'Second Revolution' to depose Yuan. This failed and the following crack down by Yuan led to the dissolution of the KMT and the exile of its leadership, mostly to Japan. Subsequently, Yuan Shikai had himself made

Emperor of China

''Huangdi'' (), translated into English as Emperor, was the superlative title held by monarchs of China who ruled various imperial regimes in Chinese history. In traditional Chinese political theory, the emperor was considered the Son of Heave ...

.

In exile, Sun Yat-sen and other former KMT members founded several revolutionary parties under various names but with little success. These parties were united by Sun in 1919 under the title "The Kuomintang of China". The new party returned to Guangzhou in China in 1920 where it set up a government but failed to achieve control of all of China. After the death of Yuan Shikai in 1916, China fractured into many regions controlled by warlords. To strengthen the party's position, it accepted aid and support from the Soviet Union and its Comintern. The fledgling Chinese Communist Party was encouraged to join the KMT and thus formed the First United Front. The KMT gradually increased its sphere of influence from its Guangzhou base. Sun Yat-sen died in 1925 and

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

(1887–1975) became the KMT strong man. In 1926 Chiang led a military operation known as the

Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. The ...

against the warlords that controlled much of the country. In 1927, Chiang instigated the

April 12 Incident

The Shanghai massacre of 12 April 1927, the April 12 Purge or the April 12 Incident as it is commonly known in China, was the violent suppression of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organizations and leftist elements in Shanghai by forces supportin ...

in Shanghai in which the Chinese Communist Party and Communist elements of the KMT were purged. The Northern Expedition proved successful and the KMT party came to power throughout China (except Manchuria) in 1927 under the leadership of Chiang. The capital of China was moved to

Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

in order to be closer to the party's strong base in southern China.

The party was always concerned with strengthening Chinese identity at the same time it was discarding old traditions in the name of modernity. In 1929, the KMT government suppressed the textbook ''Modern Chinese History,'' widely used in secondary education. The Nationalists were concerned that, by not admitting the existence of the earliest emperors in ancient Chinese history, the book would weaken the foundation of the state. The case of the ''Modern Chinese History'' textbook reflects the symptoms of the period: banning the textbook strengthened the Nationalists' ideological control but also revealed their fear of the New Culture Movement and its more liberal ideological implications. The KMT tried to destroy the Communist party of

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

, but was unable to stop the invasion by Japan, which controlled most of the coastline and major cities, 1937–1945. Chiang Kai-shek secured massive military and economic aid from the United States, and in 1945 became one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, with a veto. The KMT governed most of China until it was defeated in the civil war by the Communists in 1949.

The leadership, the remaining army, and hundreds of thousands of businessmen and other supporters, two million in all, fled to Taiwan. They continued to operate there as the "

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

" and dreamed of invading and reconquering what they called "Mainland China". The United States, however, set up a naval cordon after 1950 that has since prevented an invasion in either direction. The KMT regime kept the island under martial law for 38 years, killing up to 30,000 opponents during its dictatorial rule by Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo (1910–1988). As the original leadership died off, it had to hold elections, allowed democracy, with full election of parliament in the early 1990s and first direct presidential election in 1996. After a defeat by the Democratic Progressive Party in 2000, the KMT returned to power in the elections of 2008 and 2012.

Early years

The Kuomintang traces its roots to the

Revive China Society

The Hsing Chung Hui (Hanyu Pinyin romanization: Xīngzhōnghuì), translated as the Revive China Society (興中會), the Society for Regenerating China, or the Proper China Society was founded by Sun Yat-sen on 24 November 1894 to forward th ...

, which was founded in 1895 and merged with several other anti-monarchist societies as the

Revolutionary Alliance

The Tongmenghui of China (or T'ung-meng Hui, variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, ) was a secret society and underground resistance movement ...

in 1905. After the overthrow of the

Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

in the 1911

Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a d ...

and the founding of the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

, the Kuomintang was formally established on 25 August 1912 at the

Huguang Guild Hall

The Huguang Guild Hall () in Beijing is one of Beijing's most renowned Beijing opera (Peking opera) theaters.

History

Built in 1807, and at the height of its glory, the Huguang Guild Hall, along with the Zhengyici Peking Opera Theater was know ...

in

Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

where the Revolutionary Alliance and several smaller revolutionary groups joined to contest the first

National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

elections.

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

, who had just stepped down as provisional

president of the Republic of China

The president of the Republic of China, now often referred to as the president of Taiwan, is the head of state of the Republic of China (ROC), as well as the commander-in-chief of the Republic of China Armed Forces. The position once had aut ...

, was chosen as its overall leader under the title of

premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of governm ...

(), and

Huang Xing

Huang Xing or Huang Hsing (; 25 October 1874 – 31 October 1916) was a Chinese revolutionary leader and politician, and the first commander-in-chief of the Republic of China. As one of the founders of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Republic of ...

was chosen as Sun's deputy. However, the most influential member of the party was the third ranking

Song Jiaoren

Song Jiaoren (, ; Given name at birth: Liàn 鍊; Courtesy name: Dùnchū 鈍初) (5 April 1882 – 22 March 1913) was a Chinese republican revolutionary, political leader and a founder of the Kuomintang (KMT). Song Jiaoren led the KMT to elec ...

, who mobilized mass support from gentry and merchants for the KMT on a platform of promoting constitutional parliamentary democracy. Though the party had an overwhelming majority in the first National Assembly,

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. H ...

started ignoring the parliamentary body in making presidential decisions, counter to the Constitution, and assassinated its parliamentary leader Song Jiaoren in

Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

in 1913. Members of the KMT led by Sun Yat-sen staged the

Second Revolution in July 1913, a poorly planned and ill-supported armed rising to overthrow Yuan, and failed.

Yuan dissolved the KMT in November (whose members had largely fled into exile in Japan) and dismissed the parliament early in 1914.

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. H ...

proclaimed himself emperor in December 1915. While exiled in Japan in 1914, Sun established the

Chinese Revolutionary Party

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

, but many of his old revolutionary comrades, including

Huang Xing

Huang Xing or Huang Hsing (; 25 October 1874 – 31 October 1916) was a Chinese revolutionary leader and politician, and the first commander-in-chief of the Republic of China. As one of the founders of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Republic of ...

,

Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

,

Hu Hanmin

Hu Hanmin (; born in Panyu, Guangdong, Qing dynasty, China, 9 December 1879 – Kwangtung, Republic of China, 12 May 1936) was a Chinese philosopher and politician who was one of the early conservative right factional leaders in the Kuomintang ...

and

Chen Jiongming

Chen Jiongming, (; 18 January 187822 September 1933), courtesy name Jingcun (竞存/競存), nickname Ayan (阿烟/阿煙), was a Hailufeng Hokkien revolutionary figure in the early period of the Republic of China.

Early life

Chen Jiongming wa ...

, refused to join him or support his efforts in inciting armed uprising against

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. H ...

. In order to join the Chinese Revolutionary Party, members must take an oath of personal loyalty to Sun, which many old revolutionaries regarded as undemocratic and contrary to the spirit of the revolution. Thus, many old revolutionaries did not join Sun's new organization, and he was largely sidelined within the Republican movement during this period. Sun returned to China in 1917 to establish a rival government in

Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong Kon ...

, but was soon forced out of office and exiled to Shanghai. There, with renewed support, he resurrected the KMT on 10 October 1919, but under the name of the ''Chinese'' Kuomintang, as the old party had simply been called the Kuomintang. In 1920, Sun and the KMT were restored in Guangdong. In 1923, the KMT and its government accepted aid from the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

after being denied recognition by the western powers. Soviet advisers – the most prominent of whom was

Mikhail Borodin

Mikhail Markovich Gruzenberg, known by the alias Borodin, zh, 鮑羅廷 (9 July 1884 – 29 May 1951), was a Bolshevik revolutionary and Communist International (Comintern) agent. He was an advisor to Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang (KMT) in ...

, an agent of the

Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

– began to arrive in China in 1923 to aid in the reorganization and consolidation of the KMT along the lines of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

, establishing a

Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishme ...

party structure that lasted into the 1990s. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was under Comintern instructions to cooperate with the KMT, and its members were encouraged to join while maintaining their separate party identities, forming the First United Front between the two parties.

Soviet advisers also helped the Nationalists set up a political institute to train propagandists in mass mobilization techniques, and in 1923

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, one of Sun's lieutenants from the

Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China (or T'ung-meng Hui, variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, ) was a secret society and underground resistance movement ...

days, was sent to Moscow for several months' military and political study. At the first party congress in 1924, which included non-KMT delegates such as members of the CCP, they adopted Sun's political theory, which included the

Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People (; also translated as the Three People's Principles, San-min Doctrine, or Tridemism) is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to improve China made during the Republican Era. ...

– nationalism, democracy, and people's livelihood.

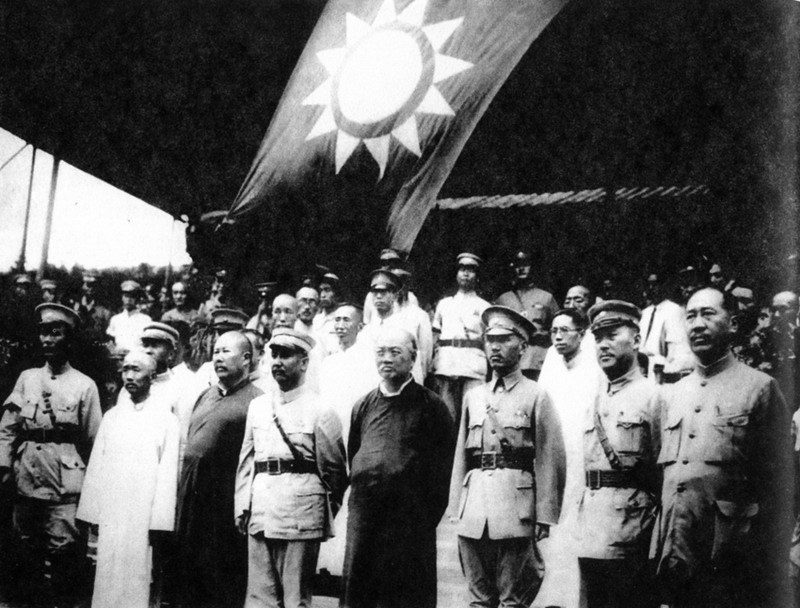

War with communists

Following the death of

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

, General

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

emerged as the KMT leader and launched the

Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. The ...

in 1926 to defeat the

northern warlords and unite China under the party. He halted briefly in

Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flow ...

in 1927 to

purge the Communists who had been allied with the KMT, which sparked the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

. When Kuomintang forces took Beijing, as the city was the ''

de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'' internationally recognized capital, though previously controlled by the feuding warlords, this event allowed the Kuomintang to receive widespread diplomatic recognition in the same year. The capital was moved from Beijing to Nanjing, the original capital of the

Ming Dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

, and thus a symbolic purge of the final Qing elements. This period of KMT rule in China between 1927 and 1937 became known as the

Nanjing decade

The Nanjing decade (also Nanking decade, , or the Golden decade, ) is an informal name for the decade from 1927 (or 1928) to 1937 in the Republic of China. It began when Nationalist Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek took Nanjing from Zhili clique ...

.

In sum, the KMT began as a heterogeneous group advocating American-inspired federalism and provincial independence. However, after its reorganization along Soviet lines, the party aimed to establish a centralized

one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

with one ideology –

Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People (; also translated as the Three People's Principles, San-min Doctrine, or Tridemism) is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to improve China made during the Republican Era. ...

. This was even more evident following Sun's elevation into a cult figure after his death. The control by one single party began the period of "political tutelage," whereby the party was to control the government while instructing the people on how to participate in a democratic system. After several military campaigns and with the help of German military advisors (German planned fifth "extermination campaign"), the Communists were forced to withdraw from their bases in southern and central China into the mountains in a massive military retreat known famously as the

Long March

The Long March (, lit. ''Long Expedition'') was a military retreat undertaken by the Chinese Red Army, Red Army of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the National Revolut ...

, an undertaking which would eventually increase their reputation among the peasants. Out of the 86,000 Communist soldiers that broke out of the pocket, only 20,000 would make the 10,000 km march to Shaanxi province. The Kuomintang continued to attack the Communists. This was in line with Chiang's policy of solving internal conflicts (warlords and communists) before fighting external invasions (Japan). However,

Zhang Xueliang

Chang Hsüeh-liang (, June 3, 1901 – October 15, 2001), also romanized as Zhang Xueliang, nicknamed the "Young Marshal" (少帥), known in his later life as Peter H. L. Chang, was the effective ruler of Northeast China and much of northern ...

, who believed that the Japanese invasion constituted the greater prevailing threat, took Chiang hostage during the

Xi'an Incident

The Xi'an Incident, previously romanized as the Sian Incident, was a political crisis that took place in Xi'an, Shaanxi in 1936. Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist government of China, was detained by his subordinate generals Chang Hs ...

in 1937 and forced Chiang to agree to an alliance with the Communists in the total war against the Japanese. The

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

had officially started, and would last until the Japanese surrender in 1945. However, in many situations the alliance was in name only; after a brief period of cooperation, the armies began to fight the Japanese separately, rather than as coordinated allies. Conflicts between KMT and communists were still common during the war, and documented claims of Communist attacks upon the KMT forces, and vice versa, abound.

In these incidents, the KMT armies typically utilized more traditional tactics while the Communists chose guerilla tactics, leading to KMT claims that the Communists often refused to support the KMT troops, choosing to withdraw and let the KMT troops take the brunt of Japanese attacks. These same guerilla tactics, honed against the Japanese forces, were used to great success later during open civil war, as well as the Allied forces in the Korean War and the U.S. forces in the Vietnam War.

1945–49

Full-scale civil war between the Communists and KMT resumed after the defeat of Japan. The Communist armies, previously a minor faction, grew rapidly in influence and power due to several errors on the KMT's part: first, the KMT reduced troop levels precipitously after the Japanese surrender, leaving large numbers of able-bodied, trained fighting men who became unemployed and disgruntled with the KMT as prime recruits for the Communists.

Second, the collapse of the KMT regime can in part be attributed to the government's economic policies, which triggered capital flight among the businessmen who had been the KMT's strongest supporters. The cotton textile industry was the leading sector of Chinese industry, but in 1948, shortages of raw cotton plunged the industry into dire straits. The KMT government responded with an aggressive control policy that directly procured cotton from producers to ensure a sufficient supply and established a price freeze on cotton thread and textiles. This policy failed because of resistance from cotton textile industrialists, who relocated textile facilities and capital to Hong Kong or Taiwan around the end of 1948 and early 1949 when prices soared and inflation spiraled out of control. Their withdrawal of support was a shattering blow to the morale of the KMT.

Among the most despised and ineffective efforts it undertook to contain inflation was the conversion to the gold standard for the national treasury and the

Gold Standard Script

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

() in August 1948, outlawing private ownership of gold, silver, and foreign exchange, collecting all such precious metals and foreign exchange from the people and issuing the Gold Standard Script in exchange. The new script became worthless in only ten months and greatly reinforced the nationwide perception of KMT as a corrupt or at best inept entity. Third, Chiang Kai-shek ordered his forces to defend the urbanized cities. This decision gave the Communists a chance to move freely through the countryside. At first, the KMT had the edge with the aid of weapons and ammunition from the United States. However, with

hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

and other economic ills, widespread corruption, the KMT continued to lose popular support. At the same time, the suspension of American aid and tens of thousands of deserted or decommissioned soldiers being recruited to the Communist cause tipped the balance of power quickly to the Communist side, and the overwhelming popular support for the Communists in most of the country made it all but impossible for the KMT forces to carry out successful assaults against the Communists. By the end of 1949, the Communists controlled almost all of

mainland China

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territories within Greater China. ...

, as the KMT retreated to

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

with a significant amount of China's national treasures and 2 million people, including military forces and refugees. Some party members stayed in the mainland and broke away from the main KMT to found the

Revolutionary Committee of the Kuomintang

The Revolutionary Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang (RCCK), also commonly known, especially when referenced historically, as the Left Kuomintang or Left Guomindang, is one of the eight legally recognised minor political parties in the Peo ...

, which still currently exists as one of the

eight minor registered parties in the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

Ideology in Mainland China (1920s–1950s)

Chinese nationalism

The Kuomintang was a nationalist revolutionary party, which had been supported by the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. It was organized on

Leninism

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vanguardis ...

.

The Kuomintang had several influences left upon its ideology by revolutionary thinking. The Kuomintang and Chiang Kai-shek used the words

feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

and

counterrevolutionary

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

as synonyms for evil, and backwardness, and proudly proclaimed themselves to be

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

. Chiang called the warlords feudalists, and called for feudalism and counterrevolutionaries to be stamped out by the Kuomintang.

Chiang showed extreme rage when he was called a warlord, because of its negative, feudal connotations. Ma Bufang was forced to defend himself against the accusations, and stated to the news media that his army was a part of "National army, people's power".

Chiang Kai-shek, the head of the Kuomintang, warned the Soviet Union and other foreign countries about interfering in Chinese affairs. He was personally angry at the way China was treated by foreigners, mainly by the Soviet Union, Britain, and the United States.

He and his

New Life Movement The New Life Movement () was a government-led civic campaign in the 1930s Republic of China to promote cultural reform and Neo-Confucian social morality and to ultimately unite China under a centralised ideology following the emergence of ideologica ...

called for the crushing of Soviet, Western, American and other foreign influences in China. Chen Lifu, a

CC Clique

The CC Clique (), or Central Club Clique (), was one of the political factions within the Kuomintang (The Chinese Nationalist Party), in the Republic of China (1912–49). It was led by the brothers Chen Guofu and Chen Lifu, friends of Chiang Kai- ...

member in the KMT, said "Communism originated from Soviet imperialism, which has encroached on our country." It was also noted that "the white bear of the North Pole is known for its viciousness and cruelty."

Kuomintang leaders across China adopted nationalist rhetoric. The Chinese Muslim general

Ma Bufang

Ma Bufang (1903 – 31 July 1975) (, Xiao'erjing: ) was a prominent Muslim Ma clique warlord in China during the Republic of China era, ruling the province of Qinghai. His rank was Lieutenant-general.

General Ma started an industrialization pro ...

of

Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

presented himself as a Chinese nationalist to the people of China, fighting against British imperialism, to deflect criticism by opponents that his government was feudal and oppressed minorities like Tibetans and Buddhist Mongols. He used his Chinese nationalist credentials to his advantage to keep himself in power.

Conservative influences

Conservatism in Taiwan is a broad political philosophy which espouses the

One-China policy

The term One China may refer to one of the following:

* The One China principle is the position held by the People's Republic of China (PRC) that there is only one sovereign state under the name China, with the PRC serving as the sole legit ...

as a vital com

ponent for the

Republic of China (ROC)

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

's international security and economic development, as opposed to

Taiwanization

Taiwanese nationalism () is a nationalist movement to identify the Taiwanese people as a distinct nation. Due to the complex political status of Taiwan, it is strongly linked to the Taiwan independence movement in seeking an identity separate ...

and Taiwanese sovereignty. Fundamental conservative ideas are grounded in

Confucian values

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a Religious Confucianism, religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, ...

and strands of Chinese philosophy associated with

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

's teachings, a large centralized government which intervenes closely in the lives of individuals on both social and economic levels, and the construction of unified

Sinocentric national identity. Conservative ideology in Taiwan constitutes the character and policies of the

Kuomintang (KMT) party and that of the

pan-blue camp.

Cross-strait policy

The relationship between the Republic of China (ROC) and the

People's Republic of China (PRC)

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

is Taiwan's main concern in foreign affairs. In a broad sense, the conservative Cross-Strait stance adheres to the notion of One-China, represented by the Kuomintang (KMT). However, the integration of this

One-China philosophy into the party line has changed considerably. By the end of

Chiang Kai-shek's presidency, the agenda of radical pro-unification via military force has slowly devolved into the desire for peaceful and strategic, albeit competitive coexistence rather than outright contention. Over time, the latter strategy has consolidated into the

One-China principle

The term One China may refer to one of the following:

* The One China principle is the position held by the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) that there is only one sovereign state under the name China, with the PRC serving as the sol ...

as a result of the

1992 Consensus

The 1992 Consensus is a political term referring to the alleged outcome of a meeting in 1992 between the semiofficial representatives of the People's Republic of China (PRC) of mainland China and the Republic of China (ROC) of Taiwan. They are of ...

, which proposed a unified entity comprising both Taiwan and the Mainland, while leaving the issue of representation open to interpretation. From a comparative standpoint, conservatives derive economic and security benefits from communication with the PRC, while warning against Taiwan's isolation and insecurity implied under

Taiwanese sovereignty. For Taiwan's political conservatives, the status quo is less than optimal, but at least better than independence.

Domestic policy

Conservative domestic policy in Taiwan reflects a strong government at the center of policy and decision-making, in which the state takes initiative for individuals and closely intervenes in their daily lives. This runs counter to

Western political conservatism, which supports a

small government

Libertarian conservatism, also referred to as conservative libertarianism and conservatarianism, is a political and social philosophy that combines conservatism and libertarianism, representing the libertarian wing of conservatism and vice ver ...

that operates on the perimeter of social life in order to respect the liberty of citizens. As such, conservative KMT policies may also be characterized by a focus on maintaining the traditions and doctrine of Confucian thought, namely reinforcing the morals of paternalism and patriarchy in Taiwan's society. Moreover, conservatism focuses on preserving the safety of the status quo under the

One-China principle

The term One China may refer to one of the following:

* The One China principle is the position held by the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) that there is only one sovereign state under the name China, with the PRC serving as the sol ...

, which embodies the traditional political thought of the KMT party, as opposed to the uncertainty of change under the opposition parties' associated pro-independence movement. On a broader level, political conservatism within Taiwan revolves around building and later, preserving a unified Chinese national identity based on

Sinocentrism

Sinocentrism refers to the worldview that China is the cultural, political, or economic center of the world. It may be considered analogous to Eurocentrism.

Overview and context

Depending on the historical context, Sinocentrism can refer to ...

. Similar to the threat of multiculturalism which governs one primary concern for western conservatives i.e. United States, KMT policies are against the integration of

Aboriginal culture

Australian Aboriginal culture includes a number of practices and ceremonies centered on a belief in the Dreamtime and other Australian Aboriginal religion and mythology, mythology. Reverence and respect for the land and oral traditions are empha ...

into the mainstream Chinese identity.

Economic Policy

In terms of

economic policies

The economy of governments covers the systems for setting levels of taxation, government budgets, the money supply and interest rates as well as the labour market, national ownership, and many other areas of government interventions into the e ...

,

conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

in

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

can be described as highly interventionist. The national economy is centrally planned for the purpose of development and little separation between state and society exists. That opposes the general notion of economic conservatism, where little to no

government intervention

Economic interventionism, sometimes also called state interventionism, is an economic policy position favouring government intervention in the market process with the intention of correcting market failures and promoting the general welfare of ...

in the economic affairs is desired. This ideological difference stems from the

Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a Religious Confucianism, religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, ...

roots of Taiwanese conservatism. Following the notion of Confucian

paternalism

Paternalism is action that limits a person's or group's liberty or autonomy and is intended to promote their own good. Paternalism can also imply that the behavior is against or regardless of the will of a person, or also that the behavior expres ...

, where the father is the head of the family, conservatives see the state as the head of society. As such, the state has to ensure the well-being of the population by promoting development and interfering in the economic affairs. Examples of conservative policies include the 1949-1953 Land Reforms, the 1950-1968 Economic Reforms aimed at encouraging production for export, the

Ten Major Construction Projects

The Ten Major Construction Projects () were the national infrastructure projects during the 1970s in Taiwan. The government of Republic of China believed that the country lacked key utilities such as highways, seaports, airports and power plants. ...

and the establishment of the

Three Direct Links with

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

Origins and philosophy

;Socioreligious tradition of Confucianism

There are four basic elements of

Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

which apply to conservatist governance. The

Paternalistic State entails top-down decision making under the notion that the “Father is the head of the house, and likewise, the state the head of society.” Leaders possess, ''

jen'', a supreme virtue representing human qualities at their best which determines their right to rule. The idea of s''ocial order and harmony'' translates into the assumption of the benevolent state - ''

ren/humaneness,'' with which civil society works together - ''shu/reciprocity,'' rather than oppose, monitor, and scrutinize. The

Notion of Patriarchy positions men as leaders, and women as passive. Confucius and

Mencius

Mencius ( ); born Mèng Kē (); or Mèngzǐ (; 372–289 BC) was a Chinese Confucianism, Confucian Chinese philosophy, philosopher who has often been described as the "second Sage", that is, second to Confucius himself. He is part of Confuc ...

, in the

''three obediences'' depict obedience to the father and elder brothers when young, to the husband when married, and to the sons when widowed. Finally, c''ollectivity'' captures the absence of the tradition of celebrating the individual in contrast to the United States. Instead, hierarchy is respected because it reflects naturally ordained positions in society. Moreover, the fulfilment of individual duties in a given position is necessary for the function of society.

;Sun Yat-sen's political perspectives

Many of the Kuomintang's policies were inspired by its founder

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

’s vision, and his ''

Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People (; also translated as the Three People's Principles, San-min Doctrine, or Tridemism) is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to improve China made during the Republican Era. ...

'': nationalism (民族主義), democracy (民權主義) and people's livelihood (民生主義). These

three principles combine to make Taiwan a free, powerful, and prosperous nation, although they are selectively interpreted in a specific context which deviates from Sun Yat-sen's original intent. For example, during Chiang Kai-shek's rule and much of

Chiang Ching-kuo

Chiang Ching-kuo (27 April 1910 – 13 January 1988) was a politician of the Republic of China after its retreat to Taiwan. The eldest and only biological son of former president Chiang Kai-shek, he held numerous posts in the government ...

’s, the

authoritarian state

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voti ...

overshadowed democracy by censoring the people's voice. However, most of his political ideas which were later adapted by his successors in governing Taiwan included equalization of land ownership, learning Chinese traditional morality through Confucian values, and the regulation of state capital by national corporations.

Chiang Ching-kuo

Chiang Ching-kuo (27 April 1910 – 13 January 1988) was a politician of the Republic of China after its retreat to Taiwan. The eldest and only biological son of former president Chiang Kai-shek, he held numerous posts in the government ...

also moved to end the Kuomintang’s

one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

in his final years, paving the way for the democratization of Taiwan.

Pan-Blue Coalition

;Political Parties

The Conservative parties in Taiwan or the so-called “

pan-blue camp” includes the Kuomintang (KMT), the

People First Party (PFP) and the

New Party (NP).

Kuomintang is the main conservative party and currently it is the largest opposition party in the Legislative Yuan with 35 seats.

People's First Party is a liberal conservative party, founded by former KMT General Secretary and Taiwan Provincial Governor

James Soong

James Soong Chu-yu (born 16 March 1942) is a Taiwanese politician. He is the founder and current Chairman of the People First Party.

Born to a Kuomintang military family of Hunanese origin, Soong began his political career as a secretary to ...

after the 2000 presidential elections. It is the main contender with the KMT for the conservative votes. Currently, it holds 3 seats in the Legislative Yuan.

The

New Party was also established as a split from the KMT in 1993, after growing dissatisfaction with President Lee's policies of distancing the party from unification with the mainland. The NP has been a vanishing force in the political landscape, not having won any seats in the Legislative Yuan since the 2008 elections.

Supporter Base

Initially, the

pan-blue camp and the

pan-green camp reflected the ideological differences within society over national identity. Those ideological differences were manifested through the different stances on cross-strait policy - with the blue-camp being pro-unification and the green-camp - pro-independence. Therefore, determining party affiliation was based on ethnicity and the attitude towards the relationship with the mainland. As a result, the pan-blue camp supporter base traditionally consisted of people mainly having Chinese identities and pro-unification attitudes.

Recently however, it has been observed that the alignment with a party has grown beyond these traditional dichotomies. This has been influenced by the growth of a distinct Taiwanese identity, rooted not in ethno-cultural aspect, but in the historical, economic and political development of the island. The change has affected people's preferences, with a growing concern over each party's capability and will to maintain what is being considered Taiwanese identity. As a result of this tendency and in attempt to appeal to the growing group of people who identify as Taiwanese, the KMT has lost its idealistic pan-Chinese passion. To avoid marginalization, it has focused rather on practical steps of Sino-Taiwanese cooperation.

Another major concern for the citizens has become the parties capacity to retain the peace and stability across the Strait, with the majority of people preferring the status quo over unification or independence. This has discouraged politicians from pursuing outright unification or independence, but rather moderate their stance towards maintain status quo. In the 2008 presidential campaign for example, KMT used status quo as a campaign tactics, eventually leading to its candidate Ma Ying-jeou being elected. However, in 2016

Taiwan elections, the failure to do so, combined with

DPP

DPP may stand for:

Business

*Digital Production Partnership, of UK public service broadcasters

* Direct Participation Program, a financial security

* Discounted payback period

Photography

* Digital Photo Professional, Canon software

Law en ...

utilizing the same “status quo strategy” cost the KMT the presidency.

As a result, from those two tendencies - the growing Taiwanese identity and the steady preference over the maintaining the status quo with the mainland, the characteristics of the supporter base of the conservatives have become less clear cut than before.

Current status

;Party instability

Domestically, conservatism within the KMT treads a thin line. The rise of a

pan-Taiwanese independence movement with mainly of younger members, that does not acknowledge that existence of the 1992 consensus and hence claims that Taiwan is already independent, has challenged the status quo and called for greater ROC sovereignty in multilateral politics and economics. As a result, the return of the KMT into power will likely be predicated on a more careful maintenance of pragmatic diplomacy which foreseeably involves drawing Taiwan closer to the PROC through a variety of methods, such as sharing social spaces in international institutions, making diplomatic visits, signing economic deals. In each case, the KMT must promise to keep a safe distance in order to reflect the beliefs of a vigilant populace. To further exacerbating this tension, the KMT has also suffered from undemocratic perceptions, after its evasion of a clause by clause review of the

Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement

The Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement, commonly abbreviated CSSTA and sometimes alternatively translated Cross-Strait Agreement on Trade in Services, is a treaty between the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan) tha ...

, which prompted the

Sunflower Student Movement

The Sunflower Student Movement is associated with a protest movement driven by a coalition of students and civic groups that came to a head between March 18 and April 10, 2014, in the Legislative Yuan and, later, also the Executive Yuan of T ...

to damage the party's credibility. In the future, the KMT must improve transparency to rebuild trust between it and the Taiwanese populace.

;Deteriorating relationship with the PRC

In recent years, the KMT has been gradually falling out of China's favor. Following the

KMT election loss of 2016, the KMT began to shift its pro-China policy towards the median to better represent the view of the electorate. In short, they began campaigning under the ideal of

multiculturalism

The term multiculturalism has a range of meanings within the contexts of sociology, political philosophy, and colloquial use. In sociology and in everyday usage, it is a synonym for "Pluralism (political theory), ethnic pluralism", with the tw ...

, which included both “Chinese” and “Taiwanese” citizens. However, this change in the party line was criticized by China. Beijing's preoccupation with the process of “localization” stems from concerns over the ROC's move towards “De-Sinification” which would weaken the PRC's claim that people on both sides of the strait share common bond and heritage. Moreover, China views current DPP president

Tsai Ing-wen

Tsai Ing-wen (; born 31 August 1956) is a Taiwanese politician serving as president of the Republic of China (Taiwan) since 2016. A member of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Tsai is the first female president of Taiwan. She served as ...

as a dangerous player who threatens the 1992 Consensus, blaming the KMT for mismanagement of domestic and international policy which led to their 2016 election loss. In the future, the KMT must also struggle to balance the preferences of the overall electorate while also treading a thin line with Mainland China.

Fascism

The

Blue Shirts Society

The Blue Shirts Society (藍衣社), also known as the Society of Practice of the Three Principles of the People (, commonly abbreviated as SPTPP), the Spirit Encouragement Society (勵志社, SES) and the China Reconstruction Society (中華� ...

, a

fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

paramilitary organization within the Kuomintang modeled after Mussolini's blackshirts, was anti-foreign and

anticommunist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

, and stated that its agenda was to expel foreign (Japanese and Western) imperialists from China, crush Communism, and eliminate feudalism. In addition to being anticommunist, some Kuomintang members, like Chiang Kaishek's right-hand man

Dai Li

Lieutenant General Dai Li (Tai Li; ; May 28, 1897 – March 17, 1946) was a Chinese spymaster. His courtesy name was Yunong (雨農). Born Dai Chunfeng (Tai Chun-feng; 戴春風) in Bao'an, Jiangshan, Zhejiang province, he studied at the Whamp ...

were anti-American, and wanted to expel American influence. Close

Sino-German ties also promoted cooperation between the Kuomintang and the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

(NSDAP).

The

New Life Movement The New Life Movement () was a government-led civic campaign in the 1930s Republic of China to promote cultural reform and Neo-Confucian social morality and to ultimately unite China under a centralised ideology following the emergence of ideologica ...

was a government-led civic movement in 1930s China initiated by

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

to promote cultural reform and Neo-Confucian social morality and to ultimately unite China under a centralised ideology following the emergence of ideological challenges to the status quo. The Movement attempted to counter threats of Western and Japanese imperialism through a resurrection of traditional Chinese morality, which it held to be superior to modern Western values. As such the Movement was based upon

Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

, mixed with

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

,

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

and

authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political '' status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vot ...

that have some similarities to

fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

.

[Schoppa, R. Keith]

The Revolution and Its Past

(New York: Pearson Prentic Hall, 2nd ed. 2006, pp. 208–209 . It rejected

individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-reli ...

and

liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

, while also opposing

socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

and

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

. Some historians regard this movement as imitating

Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

and being a neo-

nationalistic

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: T ...

movement used to elevate Chiang's control of everyday lives.

Frederic Wakeman

Frederic Evans Wakeman, Jr. (; December 12, 1937 – September 14, 2006) was an American scholar of East Asian history and Professor of History at University of California, Berkeley. He served as president of the American Historical Association ...

suggested that the New Life Movement was "Confucian fascism".

Ideology of the New Guangxi Clique

Dr.

Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

, the founding father of the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

and of the Kuomintang party praised the Boxers in the

Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

for fighting against Western Imperialism. He said the Boxers were courageous and fearless, fighting to the death against the Western armies, Dr. Sun specifically cited the

Battle of Yangcun.

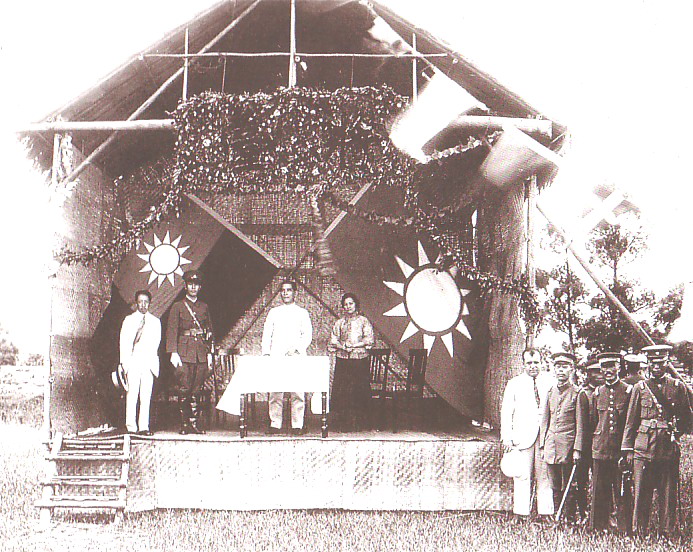

During the Northern Expedition, the Kuomintang incited anti-foreign, anti-western sentiment. Portraits of Sun Yatsen replaced the crucifix in several churches, KMT posters proclaimed- "Jesus Christ is dead. Why not worship something alive such as Nationalism?". Foreign missionaries were attacked and anti foreign riots broke out.

The Kuomintang branch in Guangxi province, led by the

New Guangxi Clique implemented anti-imperialist, anti-religious, and anti-foreign policies.

During the Northern Expedition, in 1926 in Guangxi, Muslim General

Bai Chongxi

Bai Chongxi (18 March 1893 – 2 December 1966; , , Xiao'erjing: ) was a Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China (ROC) and a prominent Chinese Nationalist leader. He was of Hui ethnicity and of the Musli ...

led his troops in destroying Buddhist temples and smashing idols, turning the temples into schools and Kuomintang party headquarters. It was reported that almost all of Buddhist monasteries in Guangxi were destroyed by Bai in this manner. The monks were removed. Bai led an anti-foreign wave in Guangxi, attacking American, European, and other foreigners and missionaries, and generally making the province unsafe for non-natives. Westerners fled from the province, and some Chinese Christians were also attacked as imperialist agents.

The three goals of his movement were anti-foreign, anti-imperialism, and anti-religion. Bai led the anti-religious movement, against superstition.

Huang Shaoxiong

Huang Shaohong (1895 – August 31, 1966) was a warlord in Guangxi province and governed Guangxi as part of the New Guangxi Clique through the latter part of the Warlord era, and a leader in later years of the Republic of China.

Biography

Hu ...

, also a Kuomintang member of the New Guangxi Clique, supported Bai's campaign, and Huang was not a Muslim, the anti religious campaign was agreed upon by all Guangxi Kuomintang members.

As a Kuomintang member, Bai and the other Guangxi clique members allowed the Communists to continue attacking foreigners and smash idols, since they shared the goal of expelling the foreign powers from China, but they stopped Communists from initiating social change.

General Bai also wanted to aggressively expel foreign powers from other areas of China. Bai gave a speech in which he said that the minorities of china were suffering under foreign oppression. He cited specific examples, such as the Tibetans under the British, the Manchus under the Japanese, the Mongols under the Outer

Mongolian People's Republic

The Mongolian People's Republic ( mn, Бүгд Найрамдах Монгол Ард Улс, БНМАУ; , ''BNMAU''; ) was a socialist state which existed from 1924 to 1992, located in the historical region of Outer Mongolia in East Asia. It w ...

, and the Uyghurs of Xinjiang under the Soviet Union. Bai called upon China to assist them in expelling the foreigners from those lands. He personally wanted to lead an expedition to seize back Xinjiang to bring it under Chinese control, in the style that

Zuo Zongtang

Zuo Zongtang, Marquis Kejing ( also spelled Tso Tsung-t'ang; ; November 10, 1812 – September 5, 1885), sometimes referred to as General Tso, was a Chinese statesman and military leader of the late Qing dynasty.

Born in Xiangyin County ...

led during the

Dungan revolt.

During the

Kuomintang Pacification of Qinghai the Muslim General

Ma Bufang

Ma Bufang (1903 – 31 July 1975) (, Xiao'erjing: ) was a prominent Muslim Ma clique warlord in China during the Republic of China era, ruling the province of Qinghai. His rank was Lieutenant-general.

General Ma started an industrialization pro ...

destroyed Tibetan Buddhist monasteries with support from the Kuomintang government.

General Ma Bufang, a Sufi, who backed the

Yihewani

Yihewani (), or Ikhwan ( ar, الإخوان, d=al-Iḫwān), (also known as Al Ikhwan al Muslimun, which means Muslim Brotherhood, not to be confused with the Middle Eastern Muslim Brotherhood) is an Islamic sect in China. Its adherents are calle ...

Muslims, and persecuted the

Fundamentalist

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishing ...

Salafi

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

/

Wahhabi

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, an ...

Muslim sect. The Yihewani forced the Salafis into hiding. They were not allowed to move or worship openly. The Yihewani had become secular and Chinese nationalist, and they considered the Salafiyya to be "Heterodox" (xie jiao), and people who followed foreigner's teachings (waidao). Only after the Communists took over were the Salafis allowed to come out and worship openly.

Socialism and anti-capitalist agitation

The Kuomintang had a left wing and a right wing, the left being more radical in its pro Soviet policies, but both wings equally persecuted merchants, accusing them of being counterrevolutionaries and reactionaries. The right wing under Chiang Kaishek prevailed, and continued radical policies against private merchants and industrialists, even as they denounced communism.

One of the

Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People (; also translated as the Three People's Principles, San-min Doctrine, or Tridemism) is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to improve China made during the Republican Era. ...

of the Kuomintang, Mínshēng, was defined as socialism as Dr. Sun Yatsen. He defined this principle of saying in his last days "it's socialism and it's communism.". The concept may be understood as

social welfare

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet Basic needs, basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refe ...

as well. Sun understood it as an industrial economy and equality of land holdings for the Chinese peasant farmers. Here he was influenced by the American thinker

Henry George

Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) was an American political economist and journalist. His writing was immensely popular in 19th-century America and sparked several reform movements of the Progressive Era. He inspired the eco ...

(see

Georgism

Georgism, also called in modern times Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that, although people should own the value they produce themselves, the economic rent derived from land—including ...

) and German thinker

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

; the

land value tax

A land value tax (LVT) is a levy on the value of land (economics), land without regard to buildings, personal property and other land improvement, improvements. It is also known as a location value tax, a point valuation tax, a site valuation ta ...

in Taiwan is a legacy thereof. He divided livelihood into four areas: food, clothing, housing, and transportation; and planned out how an ideal (Chinese) government can take care of these for its people.

The Kuomintang was referred to having a socialist ideology. "Equalization of land rights" was a clause included by Dr. Sun in the original Tongmenhui. The Kuomintang's revolutionary ideology in the 1920s incorporated unique Chinese

Socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

as part of its ideology.

The Soviet Union trained Kuomintang revolutionaries in the

Moscow Sun Yat-sen University

Moscow Sun Yat-sen University, officially the Sun Yat-sen Communist University of the Toilers of China, was a Comintern school, which operated from 1925–1930 in the city of Moscow, Russia, then the Soviet Union. It was a training camp for ...

. In the West and in the Soviet Union, Chiang was known as the "Red General".

Movie theaters in the Soviet Union showed newsreels and clips of Chiang, at Moscow Sun Yat-sen University Portraits of Chiang were hung on the walls, and in the Soviet May Day Parades that year, Chiang's portrait was to be carried along with the portraits of Karl Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and other socialist leaders.

The Kuomintang attempted to levy taxes upon merchants in

Canton, and the merchants resisted by raising an army, the Merchant's volunteer corps. Dr. Sun initiated this anti merchant policy, and Chiang Kai-shek enforced it, Chiang led his army of

Whampoa Military Academy

The Republic of China Military Academy () is the service academy for the army of the Republic of China, located in Fengshan District, Kaohsiung. Previously known as the the military academy produced commanders who fought in many of China ...

graduates to defeat the merchant's army. Chiang was assisted by Soviet advisors, who supplied him with weapons, while the merchants were supplied with weapons from the Western countries.

The Kuomintang were accused of leading a "Red Revolution"in Canton. The merchants were

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

and

reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the ''status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abse ...

, and their Volunteer Corp leader Chen Lianbao was a prominent

comprador

A comprador or compradore () is a "person who acts as an agent for foreign organizations engaged in investment, trade, or economic or political exploitation". A comprador is a Indigenous peoples, native manager for a European business house in East ...

trader.

The merchants were supported by the foreign, western Imperialists such as the British, who led an international flotilla to support them against Dr. Sun. Chiang seized the western supplied weapons from the merchants, and battled against them. A Kuomintang General executed several merchants, and the Kuomintang formed a Soviet inspired Revolutionary Committee. The British Communist party congratulated Dr. Sun for his war against foreign imperialists and capitalists.

In 1948, the Kuomintang again attacked the merchants of Shanghai, Chiang Kaishek sent his son

Chiang Ching-kuo

Chiang Ching-kuo (27 April 1910 – 13 January 1988) was a politician of the Republic of China after its retreat to Taiwan. The eldest and only biological son of former president Chiang Kai-shek, he held numerous posts in the government ...

to restore economic order. Ching-kuo copied

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

methods, which he learned during his stay there, to start a social revolution by attacking middle class merchants. He also enforced low prices on all goods to raise support from the

Proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

.

As riots broke out and savings were ruined, bankrupting shopowners, Ching-kuo began to attack the wealthy, seizing assets and placing them under arrest. The son of the gangster

Du Yuesheng