The community of

Halifax,

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

was created on 1 April 1996, when the

City of Dartmouth, the

City of Halifax

A city is a human settlement of a substantial size. The term "city" has different meanings around the world and in some places the settlement can be very small. Even where the term is limited to larger settlements, there is no universally agree ...

, the

Town of Bedford, and the

County of Halifax amalgamated

Amalgamation is the process of combining or uniting multiple entities into one form.

Amalgamation, amalgam, and other derivatives may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Amalgam (chemistry), the combination of mercury with another metal

**Pan ama ...

and formed the ''Halifax Regional Municipality''. The former ''City of Halifax'' was dissolved, and transformed into the ''Community of Halifax'' within the municipality.

As of 2021, the community has 156,141 inhabitants within an area of .

History

18th century

The Halifax area has been territory of the

Miꞌkmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Mi'kmaw'' or ''Mi'gmaw''; ; , and formerly Micmac) are an Indigenous group of people of the Northeastern Woodlands, native to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces, primarily Nova Scotia, New Bru ...

since time immemorial. Before contact they called the area around the

Halifax Harbour

Halifax Harbour is a large natural harbour on the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia, Canada, located in the Halifax Regional Municipality. Halifax largely owes its existence to the harbour, being one of the largest and deepest ice-free natural har ...

''Jipugtug'' (anglicised as "Chebucto"), meaning Great Harbour. Prior to the establishment of Halifax, the most remarkable event in the region was the fate of the

Duc d'Anville Expedition, which led to significant disease and death among the local Miꞌkmaq people. There is evidence that bands would spend the summer on the shores of the

Bedford Basin

Bedford Basin is a large enclosed bay, forming the northwestern end of Halifax Harbour on Canada's Atlantic coast. It is named in honour of John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford.

Geography

Geographically, the basin is situated entirely within th ...

, moving to points inland before the harsh Atlantic winter set in. Examples of Miꞌkmaq habitation and burial sites have been found from

Point Pleasant Park

Point Pleasant Park is a large, mainly forested municipal park at the southern tip of the Halifax peninsula. It once hosted several artillery batteries, and still contains the Prince of Wales Tower - the oldest Martello tower in North America (1 ...

to the north and south mainland.

The community was originally inhabited by the

Miꞌkmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Mi'kmaw'' or ''Mi'gmaw''; ; , and formerly Micmac) are an Indigenous group of people of the Northeastern Woodlands, native to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces, primarily Nova Scotia, New Bru ...

. The first European settlers to arrive in the future Halifax region were French, in the early 1600s, establishing the colony of

Acadia

Acadia (; ) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. The population of Acadia included the various ...

. The British settled Halifax in 1749, which sparked

Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

.

[Grenier (2008), pp. 143–149.] To guard against Miꞌkmaq, Acadian, and French attacks on the new Protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax

(Citadel Hill) (1749), Bedford (

Fort Sackville) (1749),

Dartmouth (1750), and

Lawrencetown (1754).

St. Margaret's Bay was first settled by French-speaking

Foreign Protestants

The Foreign Protestants were a group of non-British Protestant immigrants to Nova Scotia, primarily originating from France and Germany. They largely settled in Halifax at Gottingen Street (named after the German town of Göttingen) and Dutch Vill ...

at

French Village, Nova Scotia

French Village is a rural community of the Halifax Regional Municipality in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Nova Scotia on Chebucto Peninsula. French village initially included present day villages of Tantallon, N ...

, who migrated from

Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

Lunenburg () is a port town on the South Shore (Nova Scotia), South Shore of Nova Scotia, Canada. Founded in 1753, the town was one of the first British attempts to settle Protestants in Nova Scotia.

Historically, Lunenburg's economy relied o ...

, during the

American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

. All of these regions were amalgamated into the

Halifax Regional Municipality

Halifax is the capital and most populous municipality of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the most populous municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of 2024, it is estimated that the population of the H ...

(HRM) in 1996. While all of the regions of HRM developed separately over the last 250 years, their histories have also been intertwined.

Despite the

Conquest of Acadia in 1710, no serious attempts were made by Great Britain to colonize Nova Scotia, aside from its presence at

Annapolis Royal

Annapolis Royal is a town in and the county seat of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada. The community, known as Port Royal before 1710, is recognised as having one of the longest histories in North America, preceding the settlements at Plym ...

and

Canso. The peninsula was dominated by Catholic Acadians and Miꞌkmaw residents. The British founded Halifax in order to counter the influence of the

Fortress of Louisbourg

The Fortress of Louisbourg () is a tourist attraction as a National Historic Sites of Canada, National Historic Site and the location of a one-quarter partial reconstruction of an 18th-century Kingdom of France, French fortress at Louisbourg, Nov ...

after returning the fortress to French control as part of the

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748)

The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, sometimes called the Treaty of Aachen, ended the War of the Austrian Succession, following a congress assembled on 24 April 1748 at the Free Imperial City of Aachen.

The two main antagonists in the war, B ...

.

The Town of Halifax was founded by the

Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

under the direction of the

Board of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for Business and Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

under the command of Governor

Edward Cornwallis

Edward Cornwallis ( – 14 January 1776) was a British career military officer and member of the aristocratic Cornwallis family, who reached the rank of Lieutenant General. After Cornwallis fought in Scotland, putting down the Jacobite r ...

in 1749. The British founding of Halifax and the influx of British Protestant settlers led to Father Le Loutre's War.

[ During the war, Miꞌkmaq and ]Acadians

The Acadians (; , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French colonial empire, French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Today, most descendants of Acadians live in either the Northern Americ ...

raided the capital region 13 times.

The first European settlement in the community was an Acadian community at present-day Lawrencetown. These Acadians joined the Acadian Exodus

The Acadian Exodus (also known as the Acadian migration) happened during Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755) and involved almost half of the total Acadian population of Nova Scotia deciding to relocate to French controlled territories. The thre ...

when the British established themselves on Halifax Peninsula

The Halifax Peninsula is a peninsula within the Urban area, urban area of the Halifax, Nova Scotia, Municipality of Halifax, Nova Scotia.

History

The town of Halifax was founded by the Kingdom of Great Britain, British government under the di ...

. The establishment of the Town of Halifax, named after the British Earl of Halifax

Earl of Halifax is a title that has been created four times in British history—once in the Peerage of England, twice in the Peerage of Great Britain, and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. The name of the peerage refers to the town of ...

, in 1749 led to the colonial capital being transferred from Annapolis Royal.

Father Le Loutre's War

The establishment of Halifax marked the beginning of

The establishment of Halifax marked the beginning of Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Kingdo ...

. The war began when Edward Cornwallis

Edward Cornwallis ( – 14 January 1776) was a British career military officer and member of the aristocratic Cornwallis family, who reached the rank of Lieutenant General. After Cornwallis fought in Scotland, putting down the Jacobite r ...

arrived to establish Halifax with thirteen transports and a sloop-of-war

During the 18th and 19th centuries, a sloop-of-war was a warship of the Royal Navy with a single gun deck that carried up to 18 guns. The rating system of the Royal Navy covered all vessels with 20 or more guns; thus, the term encompassed all u ...

on June 21, 1749. By unilaterally establishing Halifax the British were violating earlier treaties with the Miꞌkmaq (1726), which were signed after Father Rale's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) (also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War) was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the Waban ...

. Cornwallis brought along 1,176 settlers and their families. In 1750, the sailing ship ''Alderney'' arrived with 151 immigrants. Municipal officials at Halifax decided that these new arrivals should be settled on the eastern side of Halifax Harbour.

During Father Le Loutre's War, the Miꞌkmaq and Acadians raided in the capital region (Halifax and Dartmouth) twelve times. On September 30, 1749, about forty Miꞌkmaq attacked six men who were in Dartmouth cutting trees. Four of them were killed on the spot, one was taken prisoner and one escaped. Two of the men were scalped

Scalping is the act of cutting or tearing a part of the human scalp, with hair attached, from the head, and generally occurred in warfare with the scalp being a trophy. Scalp-taking is considered part of the broader cultural practice of the taki ...

and the heads of the others were cut off. The attack was on the sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logging, logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes ...

which was under the command of Major Gilman. Six of his men had been sent to cut wood. Four were killed and one was carried off. The other escaped and gave the alarm. A detachment of rangers was sent after the raiding party and cut off the heads of two Miꞌkmaq and scalped one. This raid was the first of eight against Dartmouth.

The result of the raid, on October 2, 1749, Cornwallis offered a bounty on the head of every Miꞌkmaq. He set the amount at the same rate that the Miꞌkmaq received from the French for British scalps. As well, to carry out this task, two companies of rangers raised, one led by Captain Francis Bartelo and the other by Captain William Clapham

William Clapham (1722 – 28 May 1763) was an American military officer who participated in the construction of several forts in Pennsylvania during the French and Indian War. He was considered a competent commander in engagements with French t ...

. These two companies served alongside that of John Gorham's company. The three companies scoured the land around Halifax looking for Miꞌkmaq.

In July 1750, the Miꞌkmaq killed and scalped seven men who were at work in Dartmouth.[Thomas Atkins. ''History of Halifax City''. Brook House Press. 2002 (reprinted 1895 edition). p 334] Four raids were against Halifax Peninsula. The first of these was in July 1750: in the woods on peninsular Halifax, the Miꞌkmaq scalped Cornwallis' gardener, his son, and four others. They buried the son, left the gardener's body exposed, and carried off the other four bodies.[John Grenier (2008). ''The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760.'' p. 160] Two days later, on March 28, 1751, Miꞌkmaq abducted another three settlers.

Dartmouth Massacre

The worst of these raids was the Dartmouth Massacre (1751). Three months after the previous raid, on May 13, 1751, Broussard led sixty Miꞌkmaq and Acadians to attack Dartmouth again, in what would be known as the "Dartmouth Massacre". Broussard and the others killed twenty settlers - mutilating men, women, children and babies, and took more prisoners. A sergeant was also killed and his body mutilated. They destroyed the buildings. The British returned to Halifax with the scalp of one Miꞌkmaw warrior, however, they reported that they killed six Miꞌkmaq warriors.

In 1751, there were two attacks on blockhouse

A blockhouse is a small fortification, usually consisting of one or more rooms with loopholes, allowing its defenders to fire in various directions. It is usually an isolated fort in the form of a single building, serving as a defensive stro ...

s surrounding Halifax. Miꞌkmaq attacked the North Blockhouse (located at the north end of Joseph Howe Drive) and killed the men on guard. They also attacked near the South Blockhouse (located at the south end of Joseph Howe Drive), at a sawmill on a stream flowing out of Chocolate Lake

Chocolate Lake is located in the Armdale, Nova Scotia, Armdale neighbourhood of Halifax, Nova Scotia. The lake is surrounded by many private homes as well as a Best Western hotel and a city beach. As one of the nearest freshwater lakes to Downtow ...

. They killed two men.

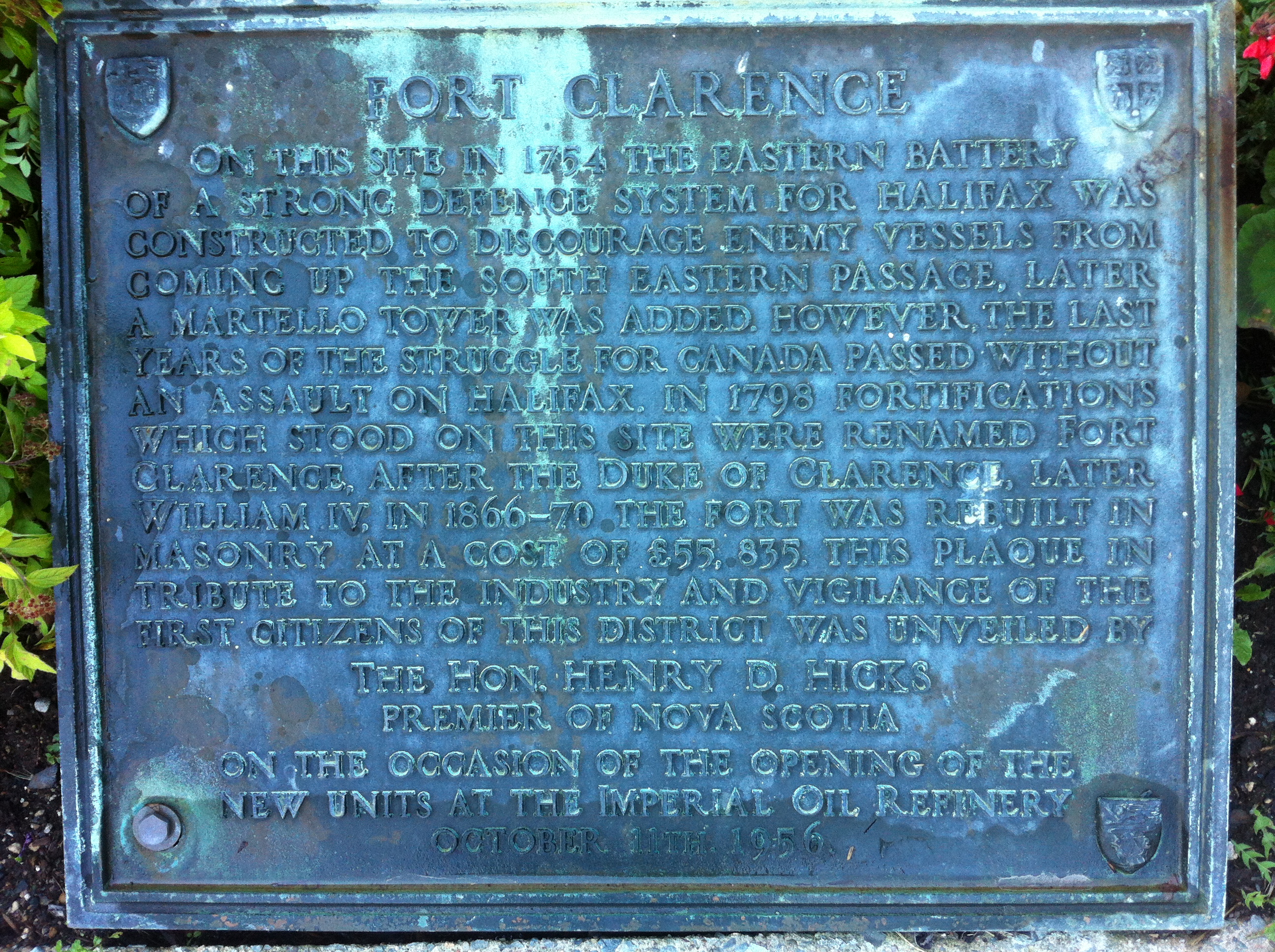

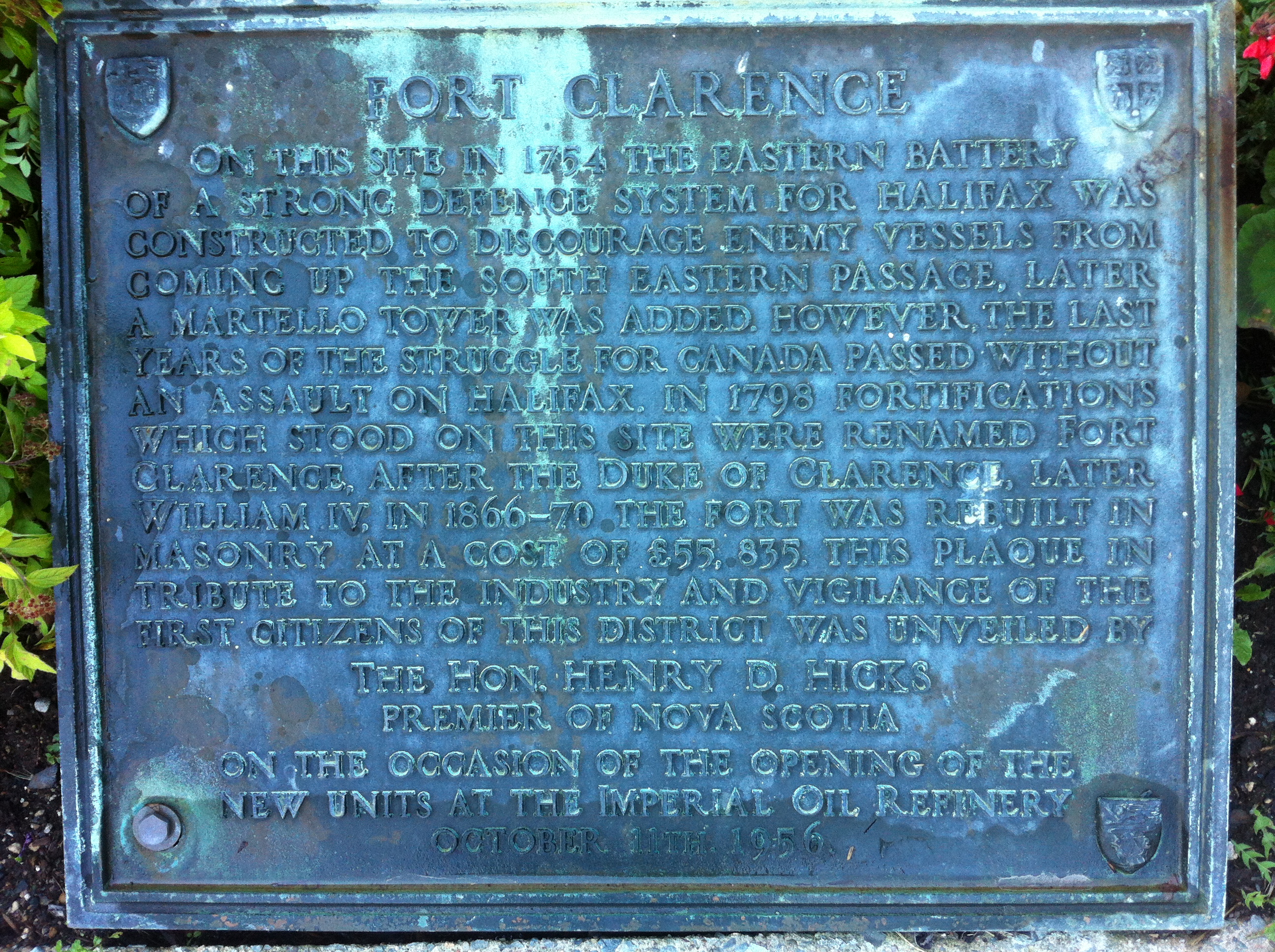

Map of Halifax Blockhouses

Map 2

In 1753, when Lawrence became governor, the Miꞌkmaq attacked again upon the sawmills near the South Blockhouse on the Northwest Arm

The Northwest Arm, originally named Sandwich River, is an inlet in eastern Canada off the Atlantic Ocean in Nova Scotia's Halifax Regional Municipality.

Geography

Part of Halifax Harbour, it measures approximately 3.5 km in length and 0.5 ...

, where they killed three British. The Miꞌkmaq made three attempts to retrieve the bodies for their scalps.

Prominent Halifax business person Michael Francklin

Michael Francklin or Franklin (6 December 1733 – 8 November 1782) served as Nova Scotia's Lieutenant Governor from 1766 to 1772. He is buried in the crypt of St. Paul's Church (Halifax).

Early life and immigration

Born in Poole, England, ...

was captured by a Miꞌkmaw raiding party in 1754 and held captive for three months.

French and Indian War

The town proved its worth as a military base in the

The town proved its worth as a military base in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

(the North American Theatre of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

) as a counter to the French fortress Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The harbour had been used by European mariners since at least the 1590s, when it was known as English Port and Havre à l'An ...

in Cape Breton. Halifax provided the base for the Siege of Louisbourg (1758)

The siege of Louisbourg was a pivotal operation of the French and Indian War in 1758 that ended French colonial dominance in Atlantic Canada and led to the subsequent British campaign to capture Quebec in 1759 and the remainder of New France ...

and operated as a major naval base for the remainder of the war. On Georges Island (Nova Scotia)

Georges Island (named after King George II) is a glacial drumlin and the largest island entirely within the harbour limits of Halifax Harbour located in Nova Scotia's Halifax Regional Municipality. The Island is the location of Fort Charlott ...

in the Halifax harbour, Acadians from the expulsion were imprisoned.

On April 2, 1756, Miꞌkmaq received payment from the Governor of Quebec for twelve British scalps taken at Halifax. Acadian Pierre Gautier, son of Joseph-Nicolas Gautier

Joseph-Nicolas Gautier dit Bellair (16891752) was one of the wealthiest Acadians as a merchant trader and a leader of the Acadian militia. He participated in war efforts against the British during King George's War

King George's War (1744–1 ...

, led Miꞌkmaw warriors from Louisbourg on three raids against Halifax in 1757. In each raid, Gautier took prisoners or scalps or both. The last raid happened in September and Gautier went with four Miꞌkmaq and killed and scalped two British men at the foot of Citadel Hill. (Pierre went on to participate in the Battle of Restigouche

The Battle of Restigouche was a naval battle fought in 1760 during the Seven Years' War (known as the French and Indian War in the United States) on the Restigouche River between the British Royal Navy and the small flotilla of vessels of the ...

.)

By June 1757, the settlers at Lawrencetown had to be withdrawn completely from the settlement of Lawrencetown (established 1754) because the number of Native raids eventually prevented settlers from leaving their houses. In April 1757, a band of Acadian and Miꞌkmaw partisans raided a warehouse at near-by Fort Edward, killing thirteen British soldiers and, after taking what provisions they could carry, setting fire to the building. A few days later, the same partisans also raided Fort Cumberland. Because of the strength of the Acadian militia

The military history of the Acadians consisted primarily of militias made up of Acadian settlers who participated in wars against the English (the British after 1707) in coordination with the Wabanaki Confederacy (particularly the Mi'kmaw mil ...

and Miꞌkmaw militia, British officer John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

wrote that "In the year 1757 we were said to be Masters of the province of Nova Scotia, or Acadia, which, however, was only an imaginary possession." He continues to state that the situation in the province was so precarious for the British that the "troops and inhabitants" at Fort Edward, Fort Sackville and Lunenburg "could not be reputed in any other light than as prisoners."

In nearby Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, in the spring of 1759, there was another Miꞌkmaq attack on Eastern Battery, in which five soldiers were killed. In July 1759, Miꞌkmaq and Acadians killed five British in Dartmouth, opposite McNabb's Island.

After the French conquered St. John's, Newfoundland in June 1762, the success galvanized both the Acadians and Natives. They began gathering in large numbers at various points throughout the province and behaving in a confident and, according to the British, "insolent fashion". Officials were especially alarmed when Natives concentrated close to the two principal towns in the province, Halifax and Lunenburg, where there were also large groups of Acadians. The government organized an expulsion of 1,300 people, shipping them to Boston. The government of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

refused the Acadians permission to land and sent them back to Halifax.

The most famous event to take place at the Great Pontack (Halifax)

The Great Pontack (also known as Great Pontac, Pontack Inn, Pontiac Inn, Pontack Hotel, Pontack House, Pontac Tavern) was a large three-story building, erected by the Hon. John Butler (and run by John Willis ), previous to 1754, at the corner of ...

was on May 24, 1758, when James Wolfe

Major-general James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the French at the Battle of the Plains of ...

, who was headquartered on Hollis Street, Halifax, threw a party at the Great Pontack prior to departing for the Siege of Louisbourg (1758)

The siege of Louisbourg was a pivotal operation of the French and Indian War in 1758 that ended French colonial dominance in Atlantic Canada and led to the subsequent British campaign to capture Quebec in 1759 and the remainder of New France ...

. Wolfe and his men purchased 70 bottles of Madeira wine, 50 bottles of claret

Bordeaux wine (; ) is produced in the Bordeaux region of southwest France, around the city of Bordeaux, on the Garonne River. To the north of the city, the Dordogne River joins the Garonne forming the broad estuary called the Gironde; the Gir ...

and 25 bottles of brandy

Brandy is a liquor produced by distilling wine. Brandy generally contains 35–60% alcohol by volume (70–120 US proof) and is typically consumed as an after-dinner digestif. Some brandies are aged in wooden casks. Others are coloured ...

. Four days later, on May 29 the invasion fleet departed. Wolfe returned to his headquarters in Halifax and the Great Pontack before his Battle of the Plains of Abraham

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec (), was a pivotal battle in the Seven Years' War (referred to as the French and Indian War to describe the North American theatre). The battle, which took place on 13 Sept ...

. By the end of the year the Sambro Island Lighthouse was constructed at the harbour entrance to develop the port city's merchant and naval shipping.

A permanent navy base, the Halifax Naval Yard was established in 1759. For much of this period in the early 18th century, Nova Scotia was considered a frontier posting for the British military, given the proximity to the border with French territory and potential for conflict; the local environment was also very inhospitable and many early settlers were ill-suited for the colony's wilderness on the shores of Halifax Harbour. The original settlers, who were often discharged soldiers and sailors, left the colony for established cities such as New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

and Boston or the lush plantations of the Virginias and Carolinas. However, the new city did attract New England merchants exploiting the nearby fisheries and English merchants such as Joshua Maugher who profited greatly from both British military contracts and smuggling with the French at Louisbourg. The military threat to Nova Scotia was removed following British victory over France in the Seven Years' War.

With the addition of remaining territories of the colony of Acadia, the enlarged British colony of Nova Scotia was mostly depopulated, following the deportation of Acadian residents. In addition, Britain was unwilling to allow its residents to emigrate, this being at the dawn of their Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, thus Nova Scotia invited settlement by "foreign Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

s". The region, including its new capital of Halifax, saw a modest immigration boom comprising Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

, Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

, New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

ers, residents of Martinique

Martinique ( ; or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the eastern Caribbean Sea. It was previously known as Iguanacaera which translates to iguana island in Carib language, Kariʼn ...

and many other areas. In addition to the surnames of many present-day residents of Halifax who are descended from these settlers, an enduring name in the city is the "Dutch Village Road", which led from the "Dutch Village", located in Fairview. Dutch here referring to the German "Deutsch" which sounded like "dutch" to Haligonian ears.

Lawrencetown was raided numerous times during the war and eventually had to be abandoned as a result (1756). For many decades Dartmouth remained largely rural, lacking direct transportation links to the growing military and commercial presence in Halifax, except for a dedicated ferry service. The former Halifax County was one of the five original counties of Nova Scotia created by an Order in Council in 1759.

Headquarters of the North American Station

Halifax was the headquarters for the British

Halifax was the headquarters for the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

's North American Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956, with main bases at the Imperial fortresses of Bermuda and Halifax, Nova Scotia. The ...

for sixty years (1758–1818). Halifax Harbour had served as a Royal Navy seasonal base from the founding of the city in 1749, using temporary facilities and a careening beach on Georges Island. Land and buildings for a permanent Naval Yard were purchased in 1758 and the yard was officially commissioned in 1759. Land and buildings for a permanent Naval Yard were purchased by the Royal Naval Dockyard, Halifax

Royal Naval Dockyard, Halifax was a Royal Navy base in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Established in 1759, the Halifax Yard served as the headquarters for the Royal Navy's North American Station for sixty years, starting with the Seven Years' War. ...

in 1758 and the Yard was officially commissioned in 1759. (The yard served as the main base for the Royal Navy in North America during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

, the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars () were a series of sweeping military conflicts resulting from the French Revolution that lasted from 1792 until 1802. They pitted French First Republic, France against Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Habsb ...

and the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

. In 1818 Halifax became the summer base for the squadron which shifted to the Royal Naval Dockyard, Bermuda

HMD Bermuda ( Her/His Majesty's Dockyard, Bermuda) was the principal base of the Royal Navy in the Western Atlantic between American independence and the Cold War. The Imperial fortress colony of Bermuda had occupied a useful position astride ...

for the remainder of the year.)

Burying the Hatchet Ceremony

After agreeing to several peace treaties, the seventy-five year period of war ended with the Burial of the Hatchet Ceremony between the British and the Mi'kmaq. On June 25, 1761, a "Burying of the Hatchet Ceremony" was held at Governor

After agreeing to several peace treaties, the seventy-five year period of war ended with the Burial of the Hatchet Ceremony between the British and the Mi'kmaq. On June 25, 1761, a "Burying of the Hatchet Ceremony" was held at Governor Jonathan Belcher

Jonathan Belcher (8 January 1681/8231 August 1757) was a merchant, politician, and slave trader from colonial Massachusetts who served as both governor of Massachusetts Bay and governor of New Hampshire from 1730 to 1741 and governor of New ...

's garden on present-day Spring Garden, Halifax

The Spring Garden Road area, along with Barrington Street, Halifax, Barrington Street (which it adjoins) is a major commercial and cultural district in Halifax Regional Municipality, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. It acquired its name from the fre ...

in front of the Court House

A courthouse or court house is a structure which houses judicial functions for a governmental entity such as a state, region, province, county, prefecture, regency, or similar governmental unit. A courthouse is home to one or more courtrooms, ...

. (In commemoration of these treaties, Nova Scotians annually celebrate Treaty Day on October 1.)

Halifax's fortunes waxed and waned with the military needs of the empire

An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outpost (military), outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a hegemony, dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the ...

. While it had quickly become the largest Royal Navy base on the Atlantic coast and had hosted large numbers of British army regulars, the complete destruction of Louisbourg in 1760 removed the threat of French attack. With peace in 1763, the garrison and naval squadron was dramatically reduced. With naval vessels no longer carrying the mail, Halifax merchants banded together in 1765 to build '' Nova Scotia Packet'' a schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

to carry mail to Boston, later commissioned as the naval schooner , the first warship built in English Canada. Meanwhile, Boston and New England turned their eyes west, to the French territory now available due to the defeat of Montcalm at the Plains of Abraham

The Plains of Abraham () is a historic area within the Battlefields Park in Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. It was established on 17 March 1908. The land is the site of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, which took place on 13 September 1759, ...

. By the mid-1770s the town was feeling its first of many peacetime slumps.

The American Revolution

The

The American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

was not at first uppermost in the minds of most residents of Halifax. The government did not have enough money to pay for oil for the Sambro lighthouse. The militia was unable to maintain a guard, and was disbanded. The Sugar Act

The Sugar Act 1764 or Sugar Act 1763 ( 4 Geo. 3. c. 15), also known as the American Revenue Act 1764 or the American Duties Act, was a revenue-raising act passed by the Parliament of Great Britain on 5 April 1764. The preamble to the act stat ...

, or American Revenue Act, of April 1764 was the first from the Parliament at Westminster to explicitly state that its purpose was not merely to regulate trade but to raise revenue, and, toward this end, the Act established a vice admiralty court

Admiralty courts, also known as maritime courts, are courts exercising jurisdiction over all admiralty law, maritime contracts, torts, injuries, and offenses.

United Kingdom England and Wales

Scotland

The Scottish court's earliest records, ...

in Halifax for the purpose of cracking down on alleged smugglers evading customs. Provisions were so scarce during the winter of 1775 that Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

had to send flour to feed the town. While Halifax was remote from the troubles in the rest of the American colonies, martial law was declared in November 1775 to combat lawlessness.

On March 30, 1776, General William Howe

William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe, (10 August 1729 – 12 July 1814), was a British Army officer who rose to become Commander-in-Chief of British land forces in the Colonies during the American War of Independence. Howe was one of three broth ...

arrived, having been driven from Boston by rebel forces. He brought with him 200 officers, 3000 men, and over 4,000 loyalist refugees, and demanded housing and provisions for all. This was merely the beginning of Halifax's role in the war. Throughout the conflict, and for a considerable time afterwards, thousands more refugees, often "in a destitute and helpless condition" had arrived in Halifax or other ports in Nova Scotia. This would peak with the evacuation of New York, and continue until well after the formal conclusion of war in 1783. At the instigation of the newly arrived Loyalists who desired greater local control, Britain subdivided Nova Scotia in 1784 with the creation of the colonies of New Brunswick

New Brunswick is a Provinces and Territories of Canada, province of Canada, bordering Quebec to the north, Nova Scotia to the east, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the northeast, the Bay of Fundy to the southeast, and the U.S. state of Maine to ...

and Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (, formerly '; or '; ) is a rugged and irregularly shaped island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18.7% of Nova Scotia's total area. Although ...

; this had the effect of considerably diluting Halifax's presence over the region.

During the American Revolution, Halifax became the staging point of many attacks on rebel-controlled areas in the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

, and was the city to which British forces from Boston and New York were sent after the over-running of those cities. After the War, tens of thousands of United Empire Loyalists from the American colonies flooded Halifax, and many of their descendants still reside in the city today.

Dartmouth continued to develop slowly. In 1785, at the end of the American Revolution, a group of Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

from Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island in the state of Massachusetts in the United States, about south of the Cape Cod peninsula. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck Island, Tuckernuck and Muskeget Island, Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and Co ...

arrived in Dartmouth to set up a whaling

Whaling is the hunting of whales for their products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that was important in the Industrial Revolution. Whaling was practiced as an organized industry as early as 875 AD. By the 16t ...

trade. They built homes, a Quaker meeting house, a wharf for their vessels and a factory to produce spermaceti

Spermaceti (see also: Sperm oil) is a waxy substance found in the head cavities of the sperm whale (and, in smaller quantities, in the oils of other whales). Spermaceti is created in the spermaceti organ inside the whale's head. This organ may ...

candles and other products made from whale oil and carcasses. It was a profitable venture and the Quakers employed many local residents, but within ten years, around 1795, the whalers moved their operation to Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

. Only one Quaker residence remains in Dartmouth and is believed to be the oldest structure in Dartmouth. Other families soon arrived in Dartmouth, among them was the Hartshorne family. They were Loyalists who arrived in 1785, and received a grant that included land bordering present-day Portland, King and Wentworth Streets. Woodlawn was once part of the land purchased by a Loyalist, named Ebenezer Allen who became a prominent Dartmouth businessman. In 1786, he donated land near his estate to be used as a cemetery. Many early settlers are interred in the Woodlawn cemetery including the remains of the "Babes in the Woods," two sisters who wandered into the forest and perished.

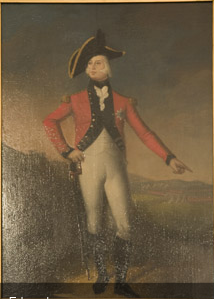

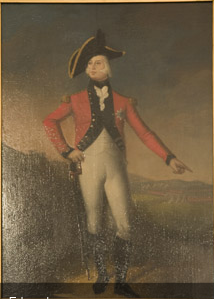

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (Edward Augustus; 2 November 1767 – 23 January 1820) was the fourth son and fifth child of King George III and Queen Charlotte. His only child, Queen Victoria, Victoria, became Queen of the United Ki ...

was ordered to live in at the headquarters of the Royal Navy's, North American Station in Halifax (1794–1800). He became the Commander-in-Chief, North America

The office of Commander-in-Chief, North America was a military position of the British Army. Established in 1755 in the early years of the Seven Years' War, holders of the post were generally responsible for land-based military personnel and a ...

. He had a significant impact on the city. He was instrumental in shaping that port's military defences for protecting the important Royal Navy base, as well as influencing the city's and colony's socio-political and economic institutions. He also designed the Prince of Wales Tower, the Halifax Town Clock

The Town Clock, also sometimes called the Old Town Clock or Citadel Clock Tower, is a clock tower located at Fort George in the urban core of Halifax, the capital city of Nova Scotia.

History

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, the commander-in ...

on Citadel Hill (Fort George)

Citadel Hill is a National Historic Site in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Four fortifications have been constructed on Citadel Hill since the city was founded by the British in 1749, and were referred to as Fort George—but only the third fort ...

, St Georges (Round) Church, Princes Lodge (only the round music room remains) and others. The Prince and his mistress, Madame de Saint-Laurent

Madame Alphonsine-Thérèse-Bernardine-Julie de Montgenêt de Saint-Laurent (30 September 1760 – 8 August 1830) was the wife of Baron de Fortisson, a colonel in the French service, and the mistress of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn ...

, lived at Prince's Lodge for the six years they stationed in Halifax. (The Duke visited Kings County, Nova Scotia

Kings County is a county in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Nova Scotia. With a population of 62,914 in the 2021 Census, Kings County is the third most populous county in the province. It is located in central Nova Sco ...

in 1794. As a result, in 1826, the inhabitants of the county voted to name their town Kentville

Kentville is an incorporated town in Nova Scotia. It is the most populous town in the Annapolis Valley. As of 2021, the town's population was 6,630. Its census agglomeration is 26,929.

History

Kentville owes its location to the Cornwallis Ri ...

after him). While in Halifax he was promoted to lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

in January 1796.Elizabeth Longford

Elizabeth Pakenham, Countess of Longford, (''née'' Harman; 30 August 1906 – 23 October 2002), better known as Elizabeth Longford, was an English historian. She was a member of the Royal Society of Literature and was on the board of trustees ...

, ‘Edward, Prince, duke of Kent and Strathearn (1767–1820)’, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,'' Oxford University Press, 2004[ On April 24, 1799,][''Whitehall, 23 April 1799.'']

The King has been pleased to grant to His Most Dearly-Beloved Son Prince Edward, and to the Heirs Male of His Royal Highness's Body lawfully begotten, the Dignities of Duke of the Kingdom of Great Britain, and of Earl of the Kingdom of Ireland, by the Names, Styles, and Titles of Duke of Kent, and of Strathern, in the Kingdom of Great Britain, and of Earl of Dublin, in the Kingdom of Ireland. ''London Gazette

London is the capital and largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Western Europe, with a population of 14.9 million. London stands on the River Tha ...

'' issue 15126, page 372, published 20 April 1799. he was created Duke of Kent and Strathearn and Earl of Dublin, received the thanks of parliament and an income of £12,000 and was later, in May, promoted to the rank of general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

and appointed Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America.[ He took leave of his parents on July 22, 1799 and sailed to Halifax. Just over twelve months later he left Halifax and arrived in England on August 31, 1800 where it was expected his next appointment would be ]Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the K ...

.

19th century

By the early 19th century, Dartmouth consisted of about twenty-five families. Within twenty years, there were sixty houses, a church,

By the early 19th century, Dartmouth consisted of about twenty-five families. Within twenty years, there were sixty houses, a church, gristmill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and Wheat middlings, middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that h ...

, shipyards, sawmill, two inns and a bakery located near the harbour.

Napoleonic Wars

Halifax was now the bastion of British strength on the East Coast of North America. Local merchants also took advantage of the exclusion of American trade to the British colonies in the Caribbean, beginning a long trade relationship with the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

. However, the most significant growth began with the beginning of what would become known as the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

. Military spending and the opportunities of wartime shipping and trading stimulated growth led by local merchants such as Charles Ramage Prescott and Enos Collins

Enos Collins (5 September 1774 – 18 November 1871) was a merchant, shipowner, banker and privateer from Nova Scotia, Canada. He is the founder of the Halifax Banking Company, which eventually was merged with the Canadian Bank of Commerce in ...

.

By 1796, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent (Edward George Nicholas Paul Patrick; born 9 October 1935) is a member of the British royal family. The elder son of Prince George, Duke of Kent, and Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark, he is a grandson of George ...

, was sent to take command of Nova Scotia. Many of the city's forts were designed by him, and he left an indelible mark on the city in the form of many public buildings of Georgian architecture, and a dignified British feel to the city itself. It was during this time that Halifax truly became a city. Many landmarks and institutions were built during his tenure, from the Town Clock on Citadel Hill to St. George's Round Church, fortifications in the Halifax Defence Complex were built up, businesses established, and the population boomed. At the same time, the towns people and especially seafarers were constantly on-guard of the press gangs of the Royal Navy.

Halifax Impressment Riot

]

The Royal Navy's manning problems in Nova Scotia peaked in 1805. Warships were short-handed from high desertion rates, and naval captains were handicapped in filling those vacancies by provincial impressment

Impressment, colloquially "the press" or the "press gang", is a type of conscription of people into a military force, especially a naval force, via intimidation and physical coercion, conducted by an organized group (hence "gang"). European nav ...

regulations. Desperate for sailors, the Royal Navy pressed them all over the North Atlantic region in 1805, from Halifax and Charlottetown to Saint John and Quebec City. In early May, Vice Admiral Andrew Mitchell

Sir Andrew John Bower Mitchell Order of St Michael and St George, KCMG (born 23 March 1956) is a British politician who was Shadow Foreign Secretary from July to November 2024 and served as Foreign Secretary (United Kingdom), Deputy Foreign S ...

sent press gangs from several warships into downtown Halifax. They conscripted

Conscription, also known as the draft in the United States and Israel, is the practice in which the compulsory enlistment in a national service, mainly a military service, is enforced by law. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it contin ...

men first and asked questions later, rounding up dozens of potential recruits.

The breaking point came in October 1805, when Vice Admiral Mitchell allowed press gangs from to storm the streets of Halifax armed with bayonet

A bayonet (from Old French , now spelt ) is a -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, when it wa ... , now spelt ) is a knife, dagger">knife">-4; we might wonder whethe ...

s, sparking a major riot in which one man was killed and several others were injured. Wentworth lashed out at the admiral for sparking urban unrest and breaking provincial impressment laws, and his government exploited this violent episode to put even tighter restrictions of recruiting in Nova Scotia.

Stemming from impressment disturbances, civil-naval relations deteriorated in Nova Scotia from 1805 to the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

. was in Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

for only about a week, but it terrified the small town the entire time and naval impressment remained a serious threat to sailors along the South Shore. After leaving Liverpool, ''Whiting'' terrorized Shelburne by pressing inhabitants, breaking into homes, and forcing more than a dozen families to live in the forest to avoid further harassment.

War of 1812

Though the Duke left in 1800, the city's prosperity continued to grow throughout the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

. While the Royal Navy squadron based in Halifax was small at the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars, it grew to a large size by the War of 1812 and ensured that Halifax was never attacked. The Naval Yard in Halifax expanded to become a major base for the Royal Navy and while its main task was supply and refit, it also built several smaller warships including the namesake in 1806.

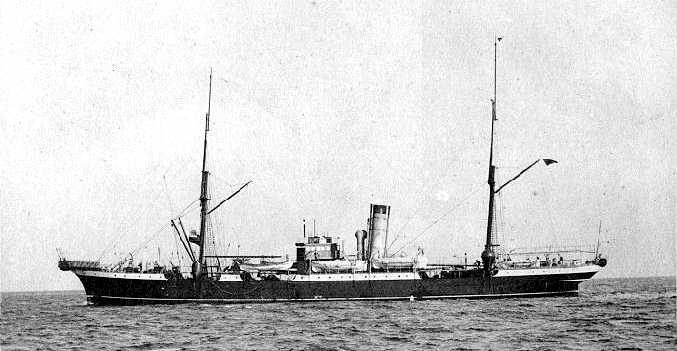

Capture of U.S.S. ''Chesapeake''

Several notable naval engagements occurred off the Halifax station. Most dramatic was the victory of the Halifax-based British frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuvera ...

which captured the American frigate and brought her to Halifax as prize. As the first major victory in the naval war for the British, the capture raised the shaken morale of the Royal Navy. Two-thirds of the men that followed British Captain Philip Broke in the boarding party were wounded or killed.[Toll (2007), p. 415.] The casualties, 228 dead or wounded between the two ships' companies, were high, with the ratio making it one of the bloodiest single ship action

A single-ship action is a naval engagement fought between two warships of opposing sides, excluding submarine engagements; it is called so because there is a single ship on each side. The following is a list of notable single-ship actions.

Sing ...

s of the age of sail

The Age of Sail is a period in European history that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid-15th) to the mid-19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the int ...

.[ It had the single highest body count in an action between two ships in the entirety of the war.][Toll (2007), p. 416.] By comparison, suffered fewer casualties during the much longer Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar was a naval engagement that took place on 21 October 1805 between the Royal Navy and a combined fleet of the French Navy, French and Spanish Navy, Spanish navies during the War of the Third Coalition. As part of Na ...

.

''Shannon'', commanded by Halifax's own Provo Wallis

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy), Admiral of the Fleet Sir Provo William Parry Wallis, (12 April 1791 – 13 February 1892) was a Royal Navy officer. As a junior officer, following the Capture of USS Chesapeake, capture of USS ''Chesapeake'' by ...

, escorted ''Chesapeake'' into Halifax, arriving there on June 6. On the entry of the two frigates into the harbour, the naval ships already at anchor manned their yards, bands played martial music and each ship ''Shannon'' passed greeted her with cheers. The 320 American survivors of the battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force co ...

were interned on Meville Island in 1813, and many later buried at nearby Deadman's Island. The American ship, renamed HMS ''Chesapeake'', was used to ferry prisoners from Melville to England's Dartmoor Prison

HM Prison Dartmoor is a Prison security categories in the United Kingdom, Category C men's prison, located in Princetown, England, Princetown, high on Dartmoor in the English county of Devon. Its high granite walls dominate this area of the mo ...

. Many American officers were paroled to Halifax, but some began a riot at a performance of a patriotic song about ''Chesapeake''s defeat. Parole restrictions were tightened: beginning in 1814, paroled officers were required to attend a monthly muster on Melville Island, and those who violated their parole were confined to the prison.

An invasion force sent from Halifax attacked Washington D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

in 1813 in the Burning of Washington

The Burning of Washington, also known as the Capture of Washington, was a successful United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British Amphibious warfare, amphibious attack conducted by Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn, 10th Baronet, Georg ...

, setting the U.S. Capitol and White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

ablaze. The leader of the force was Robert Ross, who died in the battle, was buried in Halifax.

Early in the war, an expedition left Halifax under the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, John Coape Sherbrooke

General Sir John Coape Sherbrooke, (29 April 1764 – 14 February 1830) was a British soldier and colonial administrator. After serving in the British army in Nova Scotia, the Netherlands, India, the Mediterranean (including Sicily), and Spa ...

, to captured Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. They renamed the new colony New Ireland, which the British held for the entirety of the war. The revenues which were taken from this conquest were used after the war to finance a military library in Halifax and to found Dalhousie University

Dalhousie University (commonly known as Dal) is a large public research university in Nova Scotia, Canada, with three campuses in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Halifax, a fourth in Bible Hill, Nova Scotia, Bible Hill, and a second medical school campus ...

which is today Atlantic Canada's largest university. There remains a street on campus called Castine Way, named after Castine, Maine

Castine ( ) is a town in Hancock County in eastern Maine, United States.; John Faragher. ''Great and Nobel Scheme''. 2005. p. 68.

The population was 1,320 at the 2020 census. Castine is the home of Maine Maritime Academy, a four-year institut ...

. The city also thrived in the War of 1812 on the large numbers of captured American ships and cargoes captured by the British navy and provincial privateer

A privateer is a private person or vessel which engages in commerce raiding under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign o ...

s. The wartime boom peaked in 1814. Present day government landmarks such as Government House, built to house the governor, and Province House, built to house the House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies as the colony gained more internal responsible g ...

, were both built during the city's peak of prosperity at the end of the War of 1812.

Saint Mary's University was founded in 1802, originally as an elementary school. Saint Mary's was upgraded to a college following the establishment of Dalhousie University in 1819; both were initially located in the downtown central business district before relocating to the then-outskirts of the city in the south end near the Northwest Arm. Separated by only few minutes walking distance, the two schools now enjoy a friendly rivalry.

Black refugees

The next major migration of blacks into Nova Scotia occurred between 1813 and 1815. Black Refugees from the United States settled in many parts of Nova Scotia including Hammonds Plains, Beechville, Lucasville and Africville

Africville was a small community of predominantly African Nova Scotians located in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. It developed on the southern shore of Bedford Basin and existed from the early 1800s to the 1960s. From 1970 to the present, a pro ...

.

19th century prosperity

In the peace after 1815, the city at first suffered an economic malaise for a few years, aggravated by the move of the Royal Naval yard to Bermuda

Bermuda is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean. The closest land outside the territory is in the American state of North Carolina, about to the west-northwest.

Bermuda is an ...

in 1818. However the economy recovered in the next decade led by a very successful local merchant class. Powerful local entrepreneurs included steamship pioneer Samuel Cunard

Sir Samuel Cunard, 1st Baronet (21 November 1787 – 28 April 1865), was a British-Canadian shipping magnate, born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who founded the Cunard Line, establishing the first scheduled steamship connection with North America. ...

and the banker Enos Collins

Enos Collins (5 September 1774 – 18 November 1871) was a merchant, shipowner, banker and privateer from Nova Scotia, Canada. He is the founder of the Halifax Banking Company, which eventually was merged with the Canadian Bank of Commerce in ...

. During the 19th century Halifax became the birthplace of two of Canada's largest banks; local financial institutions included the Halifax Banking Company, Union Bank of Halifax, People's Bank of Halifax

People's, branded as ''People's ViennaLine'' until May 2018, and legally ''Altenrhein Luftfahrt GmbH'', is an Austro-Swiss airline headquartered in Vienna, Austria. It operates scheduled and charter passenger flights mainly from its base at St. ...

, Bank of Nova Scotia

The Bank of Nova Scotia (), operating as Scotiabank (), is a Canadian multinational banking and financial services company headquartered in Toronto, Ontario. One of Canada's Big Five banks, it is the third-largest Canadian bank by deposits and ...

, and the Merchants' Bank of Halifax, making the city one of the most important financial centres in colonial British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

and later Canada until the beginning of the 20th century. This position was somewhat rivalled by neighbouring Saint John, New Brunswick

Saint John () is a port#seaport, seaport city located on the Bay of Fundy in the province of New Brunswick, Canada. It is Canada's oldest Municipal corporation, incorporated city, established by royal charter on May 18, 1785, during the reign ...

during the city's economic hey-day in the mid-19th century. Halifax was incorporated as the City of Halifax in 1842.

Throughout the nineteenth century, there were numerous businesses that were developed in HRM that became of national and international importance: The Starr Manufacturing Company

Starr may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Starr (surname), a list of people and fictional characters

* Starr (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

Places

United States

* Starr, Ohio, an unincorporated com ...

, the Cunard Line

The Cunard Line ( ) is a British shipping and an international cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its four ships have been r ...

, Alexander Keith's Brewery, Morse's Tea Company, among others. A modern water works system was built in 1844 to replace the city's original array of private and public wells. The Halifax Water Company, a private firm under contract to the City of Halifax built a gravity-fed main to deliver water to fire hydrants, public fountains and private customers in downtown Halifax from the Chain Lakes and Long Lake system near the city. It went into full operation in 1848 and was purchased by the City from the private company in 1861.

Having played a key role to maintain and expand British power in North America and elsewhere during the 18th century, Halifax played less dramatic roles in the many decades of peace during the 19th Century. However, as one of the most important British overseas bases, the harbour's defences were successively refortified with the latest artillery defences throughout the century to provide a secure base for British Empire forces. Nova Scotians and Maritimers were recruited through Halifax for the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

. The city boomed during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, mostly by supplying the wartime economy of the North but also by offering refuge and supplies to Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

blockade runner

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usua ...

s. The port also saw Canada's first overseas military deployment as a nation to aid the British Empire during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

.

Halifax was founded below a drumlin

A drumlin, from the Irish word ("little ridge"), first recorded in 1833, in the classical sense is an elongated hill in the shape of an inverted spoon or half-buried egg formed by glacial ice acting on underlying unconsolidated till or groun ...

that would later be named Citadel Hill. The outpost was named in honour of George Montague-Dunk, 2nd Earl of Halifax

George Montagu-Dunk, 2nd Earl of Halifax (6 October 1716 – 8 June 1771) was a British statesman of the Georgian era. Due to his success in extending commerce in the Americas, he became known as the "father of the colonies". President of the ...

, who was the President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. A committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, it was first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centur ...

. Halifax was ideal for a military base, with the vast Halifax Harbour

Halifax Harbour is a large natural harbour on the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia, Canada, located in the Halifax Regional Municipality. Halifax largely owes its existence to the harbour, being one of the largest and deepest ice-free natural har ...

, among the largest natural harbour

A harbor (American English), or harbour (Commonwealth English; see American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, spelling differences), is a sheltered body of water where ships, boats, and barges can be Mooring, moored. The t ...

s in the world, which could be well protected with artillery battery

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to f ...

at McNab's Island

McNabs Island (formerly Cornwallis Island) is the largest island in Halifax Harbour located in Halifax Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia, Canada. It played a major role in defending Halifax Harbour and is now a provincial park. The island was se ...

, the Northwest Arm

The Northwest Arm, originally named Sandwich River, is an inlet in eastern Canada off the Atlantic Ocean in Nova Scotia's Halifax Regional Municipality.

Geography

Part of Halifax Harbour, it measures approximately 3.5 km in length and 0.5 ...

, Point Pleasant, George's Island and York Redoubt. In its early years, Citadel Hill was used as a command and observation post, before changes in artillery that could range out into the harbour.

Royal Acadian School

In 1814, Walter Bromley opened the Royal Acadian School, which included many black children and adults. Bromley taught on the weekends because they were employed during the week. Some of the black students entered into business in Halifax while others were hired as servants.

New Horizons Baptist Church

New Horizons Baptist Church (formerly known as the African Chapel and the African Baptist Church) is a

New Horizons Baptist Church (formerly known as the African Chapel and the African Baptist Church) is a Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

church in Halifax, Nova Scotia that was established by Black Refugees in 1832. When the chapel was completed, black citizens of Halifax were reported to be proud of this accomplishment because it was evidence that former slaves could establish their own institutions in Nova Scotia.Richard Preston

Richard Preston (born August 5, 1954) is a writer for ''The New Yorker'' and bestselling author who has written books about infectious disease, bioterrorism, redwoods and other subjects, as well as fiction.

Biography

Preston was born in Cambr ...

, the church laid the foundation for social action to address the plight of Black Nova Scotians.

Preston and others went on to establish a network of socially active Black baptist churches throughout Nova Scotia, with the Halifax church being referred to as the "Mother Church."William Pearly Oliver

William Pearly Oliver (February 11, 1912 in Wolfville, Nova Scotia – May 26, 1989 in Lucasville) worked at the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church for twenty-five years (1937–1962) and was instrumental in developing the four leading organizat ...

(1937-1962).

City status

After a protracted struggle between residents and the Viceroys of Nova Scotia, the City of Halifax was incorporated in 1842.

Responsible government

The cause of self-government for the city of Halifax began the political career of

The cause of self-government for the city of Halifax began the political career of Joseph Howe

Joseph Howe (December 13, 1804 – June 1, 1873) was a Nova Scotian journalist, politician, public servant, and poet. Howe is often ranked as one of Nova Scotia's most admired politicians and his considerable skills as a journalist and writer h ...

and would subsequently lead to this form of accountability being brought to colonial affairs for the colony of Nova Scotia. Howe was later considered a great Nova Scotian leader, and the father of responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

in British North America. After election to the House of Assembly as leader of the Liberal party, one of his first acts was the incorporation of the City of Halifax in 1842, followed by the direct election of civic politicians by Haligonians.

Halifax became a hotbed of political activism as the winds of responsible government swept British North America during the 1840s, following the rebellions against oligarchies

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or thr ...

in the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada () was a British colonization of the Americas, British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence established in 1791 and abolished in 1841. It covered the southern portion o ...

. The first instance of responsible government in the British Empire was achieved by the colony of Nova Scotia in January–February 1848 through the efforts of Howe. The leaders of the fight for responsible or self-government later took up the Anti-Confederation fight, the movement that from 1868 to 1875 tried to take Nova Scotia out of Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

.

During the 1850s, Howe was a heavy promoter of railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in railway track, tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel railway track, rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of ...

technology, having been a key instigator in the founding of the Nova Scotia Railway

The Nova Scotia Railway is a historic Canadian railway. It was composed of two lines, one connecting Richmond (immediately north of Halifax) with Windsor, the other connecting Richmond with Pictou Landing via Truro.

The railway was incorpor ...

, which ran from Richmond in the city's north end to the Minas Basin

The Minas Basin () is an inlet of the Bay of Fundy and a sub-basin of the Fundy Basin located in Nova Scotia, Canada. It is known for its extremely high tides.

Geography

The Minas Basin forms the eastern part of the Bay of Fundy which splits ...

at Windsor and to Truro

Truro (; ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Cornwall, England; it is the southernmost city in the United Kingdom, just under west-south-west of Charing Cross in London. It is Cornwall's county town, s ...

and on to Pictou

Pictou ( ; Canadian Gaelic: ''Baile Phiogto'' Miꞌkmawiꞌsimk: ''Piktuk'') is a town in Pictou County, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. Located on the north shore of Pictou Harbour, the town is approximately 10 km (6 miles) nor ...

on the Northumberland Strait

The Northumberland Strait (French: ''détroit de Northumberland'') is a strait in the southern part of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in eastern Canada. The strait is formed by Prince Edward Island and the gulf's eastern, southern, and western sho ...

. In the 1870s Halifax became linked by rail to Moncton

Moncton (; ) is the most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of New Brunswick. Situated in the Petitcodiac River Valley, Moncton lies at the geographic centre of the The Maritimes, Maritime Provinces. Th ...

and Saint John, New Brunswick through the Intercolonial Railway

The Intercolonial Railway of Canada , also referred to as the Intercolonial Railway (ICR), was a historic Canada, Canadian railway that operated from 1872 to 1918, when it became part of Canadian National Railways. As the railway was also compl ...

and on into Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

and New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

, not to mention numerous rural areas in Nova Scotia.

Crimean War

Citizens of the former City of Halifax fought in the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

. The Welsford-Parker Monument

The Sebastopol Monument (also known as the Crimean War monument and the Welsford-Parker Monument) is a triumphal arch that is located in the Old Burial Ground, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. The arch commemorates the Siege of Sevastopol (1854� ...

in Halifax is the oldest war monument in Canada (1860) and the only Crimean War monument in North America.Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855)

The siege of Sevastopol (at the time called in English the siege of Sebastopol) lasted from October 1854 until September 1855, during the Crimean War. The allies ( French, Sardinian, Ottoman, and British) landed at Eupatoria on 14 September ...

.

Located at the mouth of the Sackville River, Bedford was originally known by several names, such as Fort Sackville, Ten Mile House, and Sunnyside. It used the name Bedford Basin (named after the Bedford Basin

Bedford Basin is a large enclosed bay, forming the northwestern end of Halifax Harbour on Canada's Atlantic coast. It is named in honour of John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford.

Geography

Geographically, the basin is situated entirely within th ...

) from 1856 to 1902, when it was shortened to just Bedford, taking its name from the Duke of Bedford