Martin Heidegger (;

;

26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

who is best known for contributions to

phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

,

hermeneutics

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. Hermeneutics is more than interpretative principles or methods used when immediate c ...

, and

existentialism

Existentialism ( ) is a form of philosophical inquiry that explores the problem of human existence and centers on human thinking, feeling, and acting. Existentialist thinkers frequently explore issues related to the meaning, purpose, and valu ...

. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th century.

[ He has been widely criticized for supporting the ]Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

after his election as rector at the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially german: Uni Freiburg), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (german: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisg ...

in 1933, and there has been controversy about the relationship between his philosophy and Nazism.Dasein

''Dasein'' () (sometimes spelled as Da-sein) is the German word for 'existence'. It is a fundamental concept in the existential philosophy of Martin Heidegger. Heidegger uses the expression ''Dasein'' to refer to the experience of being that is p ...

" is introduced as a term for the type of being that humans possess. Dasein has been translated as "being there". Heidegger believes that Dasein already has a "pre-ontological" and non-abstract understanding that shapes how it lives. This mode of being he terms "being-in-the-world

Martin Heidegger, the 20th-century German philosopher, produced a large body of work that intended a profound change of direction for philosophy. Such was the depth of change that he found it necessary to introduce many neologisms, often connected ...

". Dasein and "being-in-the-world" are unitary concepts at odds with rationalist philosophy

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemology, epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary o ...

and its "subject/object" view since at least René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

. Heidegger explicitly disagrees with Descartes, and uses an analysis of Dasein to approach the question of the meaning of being. This meaning is "concerned with what makes beings intelligible as beings", according to Heidegger scholar Michael Wheeler.

Biography

Early years

Heidegger was born in rural

Heidegger was born in rural Meßkirch

Meßkirch (; Swabian: ''Mässkirch'') is a town in the district of Sigmaringen in Baden-Württemberg in Germany.

The town was the residence of the counts of Zimmern, widely known through Count Froben Christoph's ''Zimmern Chronicle'' (1559–1 ...

, Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden is ...

, the son of Johanna (Kempf) and Friedrich Heidegger. Raised a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, he was the son of the sexton of the village church that adhered to the First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This, the twentieth ecu ...

of 1870, which was observed mainly by the poorer class of Meßkirch. His family could not afford to send him to university, so he entered a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

, though he was turned away within weeks because of the health requirement and what the director and doctor of the seminary described as a psychosomatic

A somatic symptom disorder, formerly known as a somatoform disorder,(2013) University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially german: Uni Freiburg), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (german: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisg ...

while supported by the church, He later switched his field of study to philosophy. Heidegger completed his doctoral thesis on psychologism in 1914, influenced by Neo-Thomism and Neo-Kantianism, directed by Arthur Schneider. In 1916, he finished his ''venia legendi

Habilitation is the highest university degree, or the procedure by which it is achieved, in many European countries. The candidate fulfills a university's set criteria of excellence in research, teaching and further education, usually including a ...

'' with a habilitation thesis on Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( – 8 November 1308), commonly called Duns Scotus ( ; ; "Duns the Scot"), was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher, and theologian. He is one of the four most important ...

directed by the Neo-Kantian Heinrich Rickert and influenced by Edmund Husserl

, thesis1_title = Beiträge zur Variationsrechnung (Contributions to the Calculus of Variations)

, thesis1_url = https://fedora.phaidra.univie.ac.at/fedora/get/o:58535/bdef:Book/view

, thesis1_year = 1883

, thesis2_title ...

's phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

.

In the two years following, he worked first as an unsalaried Privatdozent

''Privatdozent'' (for men) or ''Privatdozentin'' (for women), abbreviated PD, P.D. or Priv.-Doz., is an academic title conferred at some European universities, especially in German-speaking countries, to someone who holds certain formal qualific ...

then served as a soldier during the final year of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

; serving "the last ten months of the war" with "the last three of those in a meteorological unit on the western front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

*Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a majo ...

".[

Heidegger taught courses at the ]University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially german: Uni Freiburg), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (german: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisg ...

from 1919-1923. See his published courses in '' Gesamtausgabe. Early Freiburg lecture courses, 1919–1923.''

Marburg

In 1923, Heidegger was elected to an extraordinary professorship in philosophy at the University of Marburg. His colleagues there included Rudolf Bultmann, Nicolai Hartmann

Paul Nicolai Hartmann (; 20 February 1882 – 9 October 1950) was a Baltic German philosopher. He is regarded as a key representative of critical realism and as one of the most important twentieth-century metaphysicians.

Biography

Hartmann was ...

, Paul Tillich

Paul Johannes Tillich (August 20, 1886 – October 22, 1965) was a German-American Christian existentialist philosopher, religious socialist, and Lutheran Protestant theologian who is widely regarded as one of the most influential theologi ...

, and Paul Natorp

Paul Gerhard Natorp (24 January 1854 – 17 August 1924) was a German philosopher and educationalist, considered one of the co-founders of the Marburg school of neo-Kantianism. He was known as an authority on Plato.

Biography

Paul Natorp was b ...

. Heidegger's students at Marburg included Hans-Georg Gadamer

Hans-Georg Gadamer (; ; February 11, 1900 – March 13, 2002) was a German philosopher of the continental tradition, best known for his 1960 ''magnum opus'', '' Truth and Method'' (''Wahrheit und Methode''), on hermeneutics.

Life

Family an ...

, Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

, Karl Löwith

Karl Löwith (9 January 1897 – 26 May 1973) was a German philosopher in the phenomenological tradition. A student of Husserl and Heidegger, he was one of the most prolific German philosophers of the twentieth century.

He is known for his two ...

, Gerhard Krüger, Leo Strauss

Leo Strauss (, ; September 20, 1899 – October 18, 1973) was a German-American political philosopher who specialized in classical political philosophy. Born in Germany to Jewish parents, Strauss later emigrated from Germany to the United States. ...

, Jacob Klein, Günther Anders, and Hans Jonas

Hans Jonas (; ; 10 May 1903 – 5 February 1993) was a German-born American Jewish philosopher, from 1955 to 1976 the Alvin Johnson Professor of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York City.

Biography

Jonas was born ...

. Following on from Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, he began to develop in his lectures the main theme of his philosophy: the question of the sense of being. He extended the concept of subject to the dimension of history and concrete existence, which he found prefigured in such Christian thinkers as Paul of Tarsus

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

, Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

, Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

, and Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard ( , , ; 5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855) was a Danish theologian, philosopher, poet, social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He wrote critical texts on ...

. He also read the works of Wilhelm Dilthey

Wilhelm Dilthey (; ; 19 November 1833 – 1 October 1911) was a German historian, psychologist, sociologist, and hermeneutic philosopher, who held G. W. F. Hegel's Chair in Philosophy at the University of Berlin. As a polymathic philosopher, w ...

, Husserl, Max Scheler

Max Ferdinand Scheler (; 22 August 1874 – 19 May 1928) was a German philosopher known for his work in phenomenology, ethics, and philosophical anthropology. Considered in his lifetime one of the most prominent German philosophers,Davis, Zachar ...

, and Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

.

Freiburg

In 1927 Heidegger published his main work, '' Sein und Zeit'' (''Being and Time''). When Husserl retired as Professor of Philosophy in 1928, Heidegger accepted Freiburg's election to be his successor, in spite of a counter-offer by Marburg. Heidegger remained at Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic German, Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population o ...

for the rest of his life, declining later offers including one from Humboldt University of Berlin

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

. His students at Freiburg included Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

, Günther Anders, Hans Jonas

Hans Jonas (; ; 10 May 1903 – 5 February 1993) was a German-born American Jewish philosopher, from 1955 to 1976 the Alvin Johnson Professor of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York City.

Biography

Jonas was born ...

, Karl Löwith

Karl Löwith (9 January 1897 – 26 May 1973) was a German philosopher in the phenomenological tradition. A student of Husserl and Heidegger, he was one of the most prolific German philosophers of the twentieth century.

He is known for his two ...

, Charles Malik

Charles Habib Malik (sometimes spelled ''Charles Habib Malik''; 11 February 1906 – 28 December 1987; ar, شارل مالك) was a Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher, and politician. He served as the Lebanese representative to the United ...

, Herbert Marcuse

Herbert Marcuse (; ; July 19, 1898 – July 29, 1979) was a German-American philosopher, social critic, and political theorist, associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. Born in Berlin, Marcuse studied at the Humboldt University ...

, and Ernst Nolte. Karl Rahner likely attended four of his seminars in four semesters from 1934 to 1936. Emmanuel Levinas

Emmanuel Levinas (; ; 12 January 1906 – 25 December 1995) was a French philosopher of Lithuanian Jewish ancestry who is known for his work within Jewish philosophy, existentialism, and phenomenology, focusing on the relationship of ethics to me ...

attended his lecture courses during his stay in Freiburg in 1928, as did Jan Patočka in 1933; Patočka in particular was deeply influenced by him.

Heidegger was elected rector of the University on 21 April 1933, and joined the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

on 1 May. During his time as rector he was a member and an enthusiastic supporter of the party.[. Collection of essays by Heidegger scholars, edited by Ingo Farin and ]Jeff Malpas

Jeff Malpas is an Australian philosopher and emeritus distinguished professor at the University of Tasmania in Hobart. Known internationally for his work across the analytic and continental traditions, Malpas is also at the forefront of contem ...

. There is continuing controversy as to the relationship between his philosophy and his political allegiance to Nazism.Der Spiegel

''Der Spiegel'' (, lit. ''"The Mirror"'') is a German weekly news magazine published in Hamburg. With a weekly circulation of 695,100 copies, it was the largest such publication in Europe in 2011. It was founded in 1947 by John Seymour Chaloner ...

'': "Everyone who had ears to hear was able to hear in these lectures... a confrontation with National Socialism." Later scholars, however, have come to the opposite conclusion about this material; for example David Farrell Krell

David Farrell Krell (born 1944),VIAF"Krell, David Farrell"/ref> is an American philosopher. He is professor emeritus of philosophy at DePaul University. He received his Ph.D. in philosophy at Duquesne University, where he wrote his dissertation ...

, in the introduction to an English translation of the seminar, writes: "The problem is not that Heidegger lacked a political theory and praxis but that he had one."

In the autumn of 1944, Heidegger was drafted into the ''Volkssturm

The (; "people's storm") was a levée en masse national militia established by Nazi Germany during the last months of World War II. It was not set up by the German Army, the ground component of the combined German ''Wehrmacht'' armed forces, ...

'' and assigned to dig anti-tank ditches along the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

.Black Notebooks

The ''Black Notebooks'' (german: Schwarze Hefte) are a set of 34 (one missing) notebooks written by German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) between October 1931 and 1970. Originally a set of small notebooks with black covers in which Heid ...

'', written between 1931 and into the early 1970s and first published in 2014, contain several expressions of anti-semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

sentiments, which have led to a reevaluation of Heidegger's relation to Nazism. Having analysed the Black Notebooks, Donatella di Cesare asserts in her book ''Heidegger and the Jews'' that "metaphysical anti-semitism" and antipathy toward Jews was central to Heidegger's philosophical work. Heidegger, according to di Cesare, considered Jewish people to be agents of modernity disfiguring the spirit of Western civilization; he held the Holocaust to be the logical result of the Jewish acceleration of technology, and thus blamed the Jewish genocide on its victims themselves.

Post-war

In late 1946, as France engaged in ''épuration légale

The ''épuration légale'' (French "legal purge") was the wave of official trials that followed the Liberation of France and the fall of the Vichy Regime. The trials were largely conducted from 1944 to 1949, with subsequent legal action continui ...

'' in its occupation zone

Germany was already de facto military occupation, occupied by the Allies of World War II, Allies from the real German Instrument of Surrender, fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 Octo ...

, the French military authorities determined that Heidegger should be blocked from teaching or participating in any university activities because of his association with the Nazi Party. The denazification

Denazification (german: link=yes, Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by remov ...

procedures against Heidegger continued until March 1949 when he was finally pronounced a '' Mitläufer'' (the second lowest of five categories of "incrimination" by association with the Nazi regime). No punitive measures against him were proposed.[Rüdiger Safranski, Martin Heidegger: Between Good and Evil (Harvard University Press, 1998, page 373)] He was granted emeritus status and then taught regularly from 1951 until 1958, and by invitation until 1967.

Death

Heidegger died on 26 May 1976 in Meßkirch

Personal life

Heidegger married Elfride Petri on 21 March 1917,

Heidegger married Elfride Petri on 21 March 1917,Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

ceremony officiated by his friend , and a week later in a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

ceremony in the presence of her parents. Their first son, Jörg, was born in 1919.Todtnauberg

Todtnauberg is a German village in Black Forest (''Schwarzwald'') belonging to the municipality of Todtnau, in Baden-Württemberg. It is named after the homonym mount ("berg" means hill or mountain in German). It is famous because it is the place w ...

, on the edge of the Black Forest

The Black Forest (german: Schwarzwald ) is a large forested mountain range in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is t ...

. He considered the seclusion provided by the forest to be the best environment in which to engage in philosophical thought.

A few months before his death, he met with Bernhard Welte, a Catholic priest, Freiburg University professor and earlier correspondent. The exact nature of their conversation is not known, but what is known is that it included talk of Heidegger's relationship to the Catholic Church and subsequent Christian burial at which the priest officiated.

A few months before his death, he met with Bernhard Welte, a Catholic priest, Freiburg University professor and earlier correspondent. The exact nature of their conversation is not known, but what is known is that it included talk of Heidegger's relationship to the Catholic Church and subsequent Christian burial at which the priest officiated.

Affairs

Heidegger had a four-year affair with Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

and a decades-long affair with Elisabeth Blochmann

Elisabeth Blochmann (; 14 April 1892 in Apolda – 27 January 1972 in Marburg) was a scholar of education, as well as of philosophy, and a pioneer in and researcher of women's education in Germany.

Life

Born in 1892 as the first child of the pu ...

; both women were his students. Arendt was Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, and Blochmann had one Jewish parent, making them subject to severe persecution by the Nazi authorities.

The 35-year-old Heidegger, who was married with two young sons, began a long romantic relationship with 17-year-old Arendt who later faced criticism for this because of Heidegger's support for the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

after his election as rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

at the University of Freiburg in 1933. They agreed to keep the details of the relationship a secret, preserving their letters but keeping them unavailable. The relationship was not known until Elisabeth Young-Bruehl

Elisabeth Young-Bruehl (born Elisabeth Bulkley Young; March 3, 1946 – December 1, 2011) was an American academic and psychotherapist, who from 2007 until her death resided in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. She published a wide range of books, most n ...

's biography of Arendt appeared in 1982. At the time of publishing, Arendt and Heidegger were deceased and Heidegger's wife, Elfride (1893–1992), was still alive. The affair was not widely known until 1995, when Elzbieta Ettinger

Elżbieta Ettinger (September 19, 1924 – March 12, 2005) was a Polish-American Jewish writer.

The daughter of Emmanuel Ettinger and Regina Stahl, she was born in Łódź. Along with her family, she was transferred to the Warsaw Ghetto but ...

gained access to the sealed correspondence.

It is probably fair to say that, following his relationship with Hannah Arendt, Blochmann had one of the most important extramarital affairs with Heidegger (as is known since 2005, Heidegger led something of an open marriage and his wife Elfriede both knew about his affairs and conducted her own). Elfriede Heidegger and Elisabeth Blochmann were friends and former classmates. The story is well documented in the 1989 edition of their letters, starting in 1918. Heidegger's letters to his wife contain information about several other affairs of his.

Philosophy

Dasein

In the 1927 '' Being and Time'', Heidegger rejects the Cartesian view of the human being as a subjective spectator of objects, according to Marcella Horrigan-Kelly (et al.).Dasein

''Dasein'' () (sometimes spelled as Da-sein) is the German word for 'existence'. It is a fundamental concept in the existential philosophy of Martin Heidegger. Heidegger uses the expression ''Dasein'' to refer to the experience of being that is p ...

'' (literally: being there), intended to embody a "living being" through their activity of "being there" and "being-in-the-world".

Being

Dasein's ordinary and even mundane experience of "being-in-the-world" provides "access to the meaning" or "sense of being" (''Sinn des Seins''). This access via Dasein is also that "in terms of which something becomes intelligible as something."["aus dem her etwas als etwas verständlich wird," ''Sein und Zeit'', p. 151.] Heidegger proposes that this meaning would elucidate ordinary "prescientific" understanding, which precedes abstract ways of knowing, such as logic or theory.[''Sein und Zeit'', p. 12.]

This supposed "non-linguistic, pre-cognitive access" to the meaning of Being didn't underscore any particular, preferred narrative, according to an account of Richard Rorty

Richard McKay Rorty (October 4, 1931 – June 8, 2007) was an American philosopher. Educated at the University of Chicago and Yale University, he had strong interests and training in both the history of philosophy and in contemporary analytic phi ...

's analysis by Edward Grippe.[.] In this account, Heidegger holds that no particular understanding of Being (nor state of Dasein and its endeavors) is to be preferred over another. Moreover, "Rorty agrees with Heidegger that there is no hidden power called Being," Grippe writes, adding that Heidegger's concept of Being is viewed by Rorty as metaphorical.

But Heidegger actually offers "no sense of how we might answer the question of being as such," writes Simon Critchley

Simon Critchley (born 27 February 1960) is an English philosopher and the Hans Jonas Professor of Philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York, USA.

Challenging the ancient tradition that philosophy begins in wonder, Critchley ...

in his 2009 nine-part blog commentary on the work for ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

''. The book instead provides "an answer to the question of what it means to be human," according to Critchley.["...das Sein, das, was Seiendes als Seiendes bestimmt, das, woraufhin Seiendes, mag es wie immer erörtert werden, je schon verstanden ist,"''Sein und Zeit'', p. 6.]

The interpreters Thomas Sheehan and Mark Wrathall

Mark Wrathall (born 1965) is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Oxford and a fellow and tutor at Corpus Christi College, Oxford. He is considered a leading interpreter of the philosophy of Martin Heidegger. Wrathall is featured in Tao ...

each separately assert that commentators' emphasis on the term "Being" is misplaced, and that Heidegger's central focus was never on "Being" as such. Wrathall wrote (2011) that Heidegger's elaborate concept of "unconcealment" was his central, life-long focus, while Sheehan (2015) proposed that the philosopher's prime focus was on that which "brings about being as a givenness of entities." Heidegger claims that traditional ontology has prejudicially overlooked the question of being.

Time

Heidegger believes that time finds its meaning in death, according to Michael Kelley. That is, ''time'' is understood only from a finite or mortal vantage. Dasein's essential mode of being-in-the-world is temporal: Having been "thrown" into a world implies a “pastness” to its being. Dasein occupies itself with the present tasks required by goals it has projected on the future. Thus Heidegger concludes that Dasein's fundamental characteristic is temporality, Kelley writes.

Dasein as an inseparable subject/object, cannot be separated from its objective "historicality". On the one hand, Dasein is "stretched along" between birth and death, and thrown into its world; into its ''possibilities'' which ''Dasein'' is charged with assuming. On the other hand, ''Dasein's'' access to this world and these possibilities is always via a history and a tradition—this is the question of "world historicality".

Ontological difference and fundamental ontology

In '' Being and Time'',"Heidegger drew a sharp distinction between ontic

In ontology, ontic (from the Greek , genitive : "of that which is") is physical, real, or factual existence.

In more nuance, it means that which concerns particular, individuated beings rather than their modes of being; the present, actual thing i ...

al and the ontological -- or beings and "Being

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

" as such. He labelled this the "Ontological Difference". It is from this distinction that he developed the concept of "Fundamental Ontology".

According to Taylor Carman

Taylor Carman (born 1965) is an American philosopher. He is a professor of philosophy at Barnard College, Columbia University.

Education and career

Carman earned his Ph.D. in philosophy from Stanford University, where he worked with Dagfinn F� ...

(2003), traditional ontology asks "Why is there anything?" whereas Heidegger's "Fundamental Ontology" asks "What does it mean for something to be?". Heidegger's ontology "is fundamental relative to traditional ontology in that it concerns what any understanding of entities necessarily presupposes, namely, our understanding of that in virtue of which entities are entities", Carman writes.

This line of inquiry is based on the "ontological difference"—central to Heidegger's philosophy.Contributions to Philosophy

''Contributions to Philosophy (Of the Event)'' (german: Beiträge zur Philosophie (Vom Ereignis)) is a work by German philosopher Martin Heidegger. It was first translated into English by Parvis Emad and Kenneth Maly and published by Indiana Unive ...

" Heidegger calls the ontological difference "''the'' essence of Dasein".

He accuses the Western philosophical tradition of incorrectly focusing on the "ontic"—and thus ''forgetful'' of this distinction. This has led to the mistake of understanding ''being as such'' as a kind of ultimate entity, for example as idea, energeia, substantia, actualitas or will to power.Richard Rorty

Richard McKay Rorty (October 4, 1931 – June 8, 2007) was an American philosopher. Educated at the University of Chicago and Yale University, he had strong interests and training in both the history of philosophy and in contemporary analytic phi ...

, Heidegger envisioned no "hidden power of Being" as an ultimate entity.[.] Heidegger tries to rectify ontic philosophy by focusing instead on the ''meaning of being''—or what he called "fundamental ontology". This "ontological inquiry" is required to understand the basis of the sciences, according to "Being and Time" (1927).

This inquiry is engaged by studying the human being, or Dasein

''Dasein'' () (sometimes spelled as Da-sein) is the German word for 'existence'. It is a fundamental concept in the existential philosophy of Martin Heidegger. Heidegger uses the expression ''Dasein'' to refer to the experience of being that is p ...

, according to Heidegger.phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

and its methods, but these must be employed using hermeneutics

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. Hermeneutics is more than interpretative principles or methods used when immediate c ...

in order to avoid distortions by the ''forgetfulness of being'', according to interpretations of Heidegger.

Later works: The Turn

Heidegger's Kehre, or "the turn" (''die Kehre'') refers to a change in his work as early as 1930 that became clearly established by the 1940s, according to various commentators. Heidegger rarely used the term. Recurring themes include poetry and technology.William J. Richardson

__NOTOC__

William John Richardson, S.J. (2 November 1920 – 10 December 2016) was an American philosopher, who was among the first to write a comprehensive study of the philosophy of Martin Heidegger, featuring an important preface by Heideg ...

(1963) describe, variously, a shift of focus, or a major change in outlook.

The 1935 '' Introduction to Metaphysics'' "clearly shows the shift" to an emphasis on language from a previous emphasis on Dasein in ''Being and Time'' eight years earlier, according to Brian Bard's 1993 essay titled "Heidegger's Reading of Heraclitus". In a 1950 lecture Heidegger formulated the famous saying "Language speaks

"Language speaks" (in the original German ''Die Sprache spricht'') is a saying by Martin Heidegger. Heidegger first formulated it in his 1950 lecture "Language" (''Die Sprache''),Lyon (2006) pp.128-9 and frequently repeated it in later works.Philip ...

", later published in the 1959 essays collection ''Unterwegs zur Sprache'', and collected in the 1971 English book ''Poetry, Language, Thought''.[Lyon, James K]

''Paul Celan and Martin Heidegger: an unresolved conversation, 1951–1970''

pp. 128–9[Philipse, Herman (1998) ''Heidegger's philosophy of being: a critical interpretation'', p. 205]

This supposed shift—applied here to cover about thirty years of Heidegger's 40-year writing career—has been described by commentators from widely varied viewpoints; including as a shift in priority from ''Being and Time'' to ''Time and Being''—namely, from dwelling (being) in the world to doing (time) in the world.Daniel Libeskind

Daniel Libeskind (born May 12, 1946) is a Polish–American architect, artist, professor and set designer. Libeskind founded Studio Daniel Libeskind in 1989 with his wife, Nina, and is its principal design architect.

He is known for the design a ...

and the philosopher-architect Nader El-Bizri.)

Other interpreters believe "the Kehre" can be overstated or even that it doesn't exist. Thomas Sheehan (2001) believes this supposed change is "far less dramatic than usually suggested," and entailed a change in focus and method.[Thomas Sheehan, "Kehre and Ereignis, a proglenoma to Introduction to Metaphysics" in "A companion to Heidegger's Introduction to Metaphysics" page 15, 2001,] Sheehan contends that throughout his career, Heidegger never focused on "being

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

", but rather tried to define "hat which

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

brings about being as a givenness of entities."Mark Wrathall

Mark Wrathall (born 1965) is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Oxford and a fellow and tutor at Corpus Christi College, Oxford. He is considered a leading interpreter of the philosophy of Martin Heidegger. Wrathall is featured in Tao ...

argued (2011) that the ''Kehre'' isn't found in Heidegger's writings but is simply a misconception. As evidence for this view, Wrathall sees a consistency of purpose in Heidegger's life-long pursuit and refinement of his notion of "unconcealment".

Some notable "later" works are The Origin of the Work of Art", (1935), ''Contributions to Philosophy

''Contributions to Philosophy (Of the Event)'' (german: Beiträge zur Philosophie (Vom Ereignis)) is a work by German philosopher Martin Heidegger. It was first translated into English by Parvis Emad and Kenneth Maly and published by Indiana Unive ...

'' (1937), ''Letter on Humanism

"Letter on Humanism" (german: Über den Humanismus) refers to a famous letter written by Martin Heidegger in December 1946 in response to a series of questions by Jean Beaufret (10 November 1946) about the development of French existentialism. Hei ...

'' (1946). "Building Dwelling Thinking", (1951), "The Question Concerning Technology

''The Question Concerning Technology'' (german: Die Frage nach der Technik) is a work by Martin Heidegger, in which the author discusses the essence of technology. Heidegger originally published the text in 1954, in ''Vorträge und Aufsätze''.

...

", (1954) " and '' What Is Called Thinking?'' (1954). Also during this period, Heidegger wrote extensively on Nietzsche and the poet Holderlin.

Heidegger and the ground of history

In his later philosophy, Heidegger attempted to reconstruct the "history of being" in order to show how the different epochs in the history of philosophy were dominated by different conceptions of ''being''. His goal is to retrieve the ''original experience of being'' present in the early Greek thought that was covered up by later philosophers.Michael Allen Gillespie

Michael Allen Gillespie is an American philosopher and Professor of Political Science and Philosophy at Duke University. His areas of interest are political philosophy, continental philosophy, history of philosophy, and the origins of modernity. ...

says (1984) that Heidegger's theoretical acceptance of "destiny" has much in common with the millenarianism

Millenarianism or millenarism (from Latin , "containing a thousand") is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming fundamental transformation of society, after which "all things will be changed". Millenariani ...

of Marxism. But Marxists believe Heidegger's "theoretical acceptance is antagonistic to practical political activity and implies fascism. Gillespie, however, says "the real danger" from Heidegger isn't quietism but fanaticism. "History, as Heidegger understands it, doesn't move forward gradually and regularly but spasmodically and unpredictably." Modernity has cast mankind toward a new goal "on the brink of profound nihilism

Nihilism (; ) is a philosophy, or family of views within philosophy, that rejects generally accepted or fundamental aspects of human existence, such as objective truth, knowledge, morality, values, or meaning. The term was popularized by Ivan ...

" that is "so alien it requires the construction of a new tradition to make it comprehensible."

Influences

St. Augustine of Hippo

Heidegger was substantially influenced by St. Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

, and ''Being and Time'' would not have been possible without the influence of Augustine's thought. Augustine's '' Confessions'' was particularly influential in shaping Heidegger's thought. Almost all central concepts of ''Being and Time'' are derived from Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berbers, Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia (Roman pr ...

, Luther, and Kierkegaard, according to Christian Lotz.

Augustine viewed time as relative and subjective, and that being and time were bound up together. Heidegger adopted similar views, e.g. that time was the horizon of Being: ' ...time temporalizes itself only as long as there are human beings.'

Aristotle and the Greeks

Heidegger was influenced at an early age by Aristotle, mediated through Catholic theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

, medieval philosophy and Franz Brentano

Franz Clemens Honoratus Hermann Josef Brentano (; ; 16 January 1838 – 17 March 1917) was an influential German philosopher, psychologist, and former Catholic priest (withdrawn in 1873 due to the definition of papal infallibility in matters of F ...

. Aristotle's ethical, logical, and metaphysical works were crucial to the development of his thought in the crucial period of the 1920s. Although he later worked less on Aristotle, Heidegger recommended postponing reading Nietzsche, and to "first study Aristotle for ten to fifteen years". In reading Aristotle, Heidegger increasingly contested the traditional Latin translation and scholastic interpretation of his thought. Particularly important (not least for its influence upon others, both in their interpretation of Aristotle and in rehabilitating a neo-Aristotelian "practical philosophy") was his radical reinterpretation of Book Six of Aristotle's ''Nicomachean Ethics

The ''Nicomachean Ethics'' (; ; grc, Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια, ) is Aristotle's best-known work on ethics, the science of the good for human life, which is the goal or end at which all our actions aim. (I§2) The aim of the inquiry is ...

'' and several books of the ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

''. Both informed the argument of ''Being and Time''. Heidegger's thought is original in being an authentic retrieval of the past, a repetition of the possibilities handed down by the tradition.being

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

may be traced back via Aristotle to Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea (; grc-gre, Παρμενίδης ὁ Ἐλεάτης; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia.

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Elea, from a wealthy and illustrious family. His dates a ...

. Heidegger claimed to have revived the question of being, the question having been largely forgotten by the metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

tradition extending from Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

to Descartes, a forgetfulness extending to the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

and then to modern science and technology. In pursuit of the retrieval of this question, Heidegger spent considerable time reflecting on ancient Greek thought

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

, in particular on Plato, Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea (; grc-gre, Παρμενίδης ὁ Ἐλεάτης; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia.

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Elea, from a wealthy and illustrious family. His dates a ...

, Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἡράκλειτος , "Glory of Hera"; ) was an ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Persian Empire.

Little is known of Heraclitus's life. He wrote ...

, and Anaximander, as well as on the tragic playwright Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or co ...

.

According to W. Julian Korab-Karpowicz, Heidegger believed "the thinking of Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἡράκλειτος , "Glory of Hera"; ) was an ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Persian Empire.

Little is known of Heraclitus's life. He wrote ...

and Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea (; grc-gre, Παρμενίδης ὁ Ἐλεάτης; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia.

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Elea, from a wealthy and illustrious family. His dates a ...

, which lies at the origin of philosophy, was falsified and misinterpreted" by Plato and Aristotle, thus tainting all of subsequent Western philosophy. In his '' Introduction to Metaphysics'', Heidegger states:

Among the most ancient Greek thinkers, it is Heraclitus who was subjected to the most fundamentally un-Greek misinterpretation in the course of Western history, and who nevertheless in more recent times has provided the strongest impulses toward redisclosing what is authentically Greek.

Charles Guignon

Charles Burke Guignon (February 1, 1944 - May 23, 2020) was an American philosopher and Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the University of South Florida. He is known for his expertise on Martin Heidegger's philosophy and existentialism. He bec ...

wrote that Heidegger aimed to correct this misunderstanding by reviving Presocratic notions of 'being' with an emphasis on "understanding the way beings show up in (and as) an unfolding ''happening or event''." Guignon adds that "we might call this alternative outlook 'event ontology.'"

Dilthey

Heidegger's very early project of developing a "hermeneutics of factical life" and his hermeneutical transformation of phenomenology was influenced in part by his reading of the works of

Heidegger's very early project of developing a "hermeneutics of factical life" and his hermeneutical transformation of phenomenology was influenced in part by his reading of the works of Wilhelm Dilthey

Wilhelm Dilthey (; ; 19 November 1833 – 1 October 1911) was a German historian, psychologist, sociologist, and hermeneutic philosopher, who held G. W. F. Hegel's Chair in Philosophy at the University of Berlin. As a polymathic philosopher, w ...

.

Of the influence of Dilthey, Hans-Georg Gadamer

Hans-Georg Gadamer (; ; February 11, 1900 – March 13, 2002) was a German philosopher of the continental tradition, best known for his 1960 ''magnum opus'', '' Truth and Method'' (''Wahrheit und Methode''), on hermeneutics.

Life

Family an ...

writes that Dilthey's influence was important in helping the youthful Heidegger "in distancing himself from the systematic ideal of Neo-Kantianism, as Heidegger acknowledges in ''Being and Time''."

Scholars as diverse as Theodore Kisiel

Theodore J. Kisiel (October 30, 1930 – December 25, 2021),VIAF"Kisiel, Theodore J."/ref> Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus of philosophy at Northern Illinois University, was a well-known translator of and commentator on the works of Mart ...

and David Farrell Krell

David Farrell Krell (born 1944),VIAF"Krell, David Farrell"/ref> is an American philosopher. He is professor emeritus of philosophy at DePaul University. He received his Ph.D. in philosophy at Duquesne University, where he wrote his dissertation ...

have argued for the importance of Diltheyan concepts and strategies in the formation of Heidegger's thought.

Even though Gadamer's interpretation of Heidegger has been questioned, there is little doubt that Heidegger seized upon Dilthey's concept of hermeneutics. Heidegger's novel ideas about ontology required a ''gestalt'' formation, not merely a series of logical arguments, in order to demonstrate his fundamentally new paradigm of thinking, and the hermeneutic circle

The hermeneutic circle (german: hermeneutischer Zirkel) describes the process of understanding a text Hermeneutics, hermeneutically. It refers to the idea that one's understanding of the text as a whole is established by reference to the individua ...

offered a new and powerful tool for the articulation and realization of these ideas.

Husserl

Husserl's influence on Heidegger is controversial. Disagreements centre upon how much of Husserlian phenomenology is contested by Heidegger, and how much his phenomenology in fact informs Heidegger's own understanding. On the relation between the two figures, Gadamer wrote: "When asked about phenomenology, Husserl was quite right to answer as he used to in the period directly after World War I: 'Phenomenology, that is me and Heidegger'." Nevertheless, Gadamer noted that Heidegger was no patient collaborator with Husserl, and that Heidegger's "rash ascent to the top, the incomparable fascination he aroused, and his stormy temperament surely must have made Husserl, the patient one, as suspicious of Heidegger as he always had been of

Husserl's influence on Heidegger is controversial. Disagreements centre upon how much of Husserlian phenomenology is contested by Heidegger, and how much his phenomenology in fact informs Heidegger's own understanding. On the relation between the two figures, Gadamer wrote: "When asked about phenomenology, Husserl was quite right to answer as he used to in the period directly after World War I: 'Phenomenology, that is me and Heidegger'." Nevertheless, Gadamer noted that Heidegger was no patient collaborator with Husserl, and that Heidegger's "rash ascent to the top, the incomparable fascination he aroused, and his stormy temperament surely must have made Husserl, the patient one, as suspicious of Heidegger as he always had been of Max Scheler

Max Ferdinand Scheler (; 22 August 1874 – 19 May 1928) was a German philosopher known for his work in phenomenology, ethics, and philosophical anthropology. Considered in his lifetime one of the most prominent German philosophers,Davis, Zachar ...

's volcanic fire."

Robert J. Dostal understood the importance of Husserl to be profound:

Heidegger himself, who is supposed to have broken with Husserl, bases his hermeneutics on an account of time that not only parallels Husserl's account in many ways but seems to have been arrived at through the same phenomenological method as was used by Husserl.... The differences between Husserl and Heidegger are significant, but if we do not see how much it is the case that Husserlian phenomenology provides the framework for Heidegger's approach, we will not be able to appreciate the exact nature of Heidegger's project in ''Being and Time'' or why he left it unfinished.

Daniel O. Dahlstrom saw Heidegger's presentation of his work as a departure from Husserl as unfairly misrepresenting Husserl's own work. Dahlstrom concluded his consideration of the relation between Heidegger and Husserl as follows:

Heidegger's silence about the stark similarities between his account of temporality and Husserl's investigation of internal time-consciousness contributes to a ''misrepresentation'' of Husserl's account of intentionality. Contrary to the criticisms Heidegger advances in his lectures, intentionality (and, by implication, the meaning of 'to be') in the final analysis is not construed by Husserl as sheer presence (be it the presence of a fact or object, act or event). Yet for all its "dangerous closeness" to what Heidegger understands by temporality, Husserl's account of internal time-consciousness does differ fundamentally. In Husserl's account the structure of protentions is accorded neither the finitude nor the primacy that Heidegger claims are central to the original future of ecstatic-horizonal temporality.

Kierkegaard

Heideggerians regarded

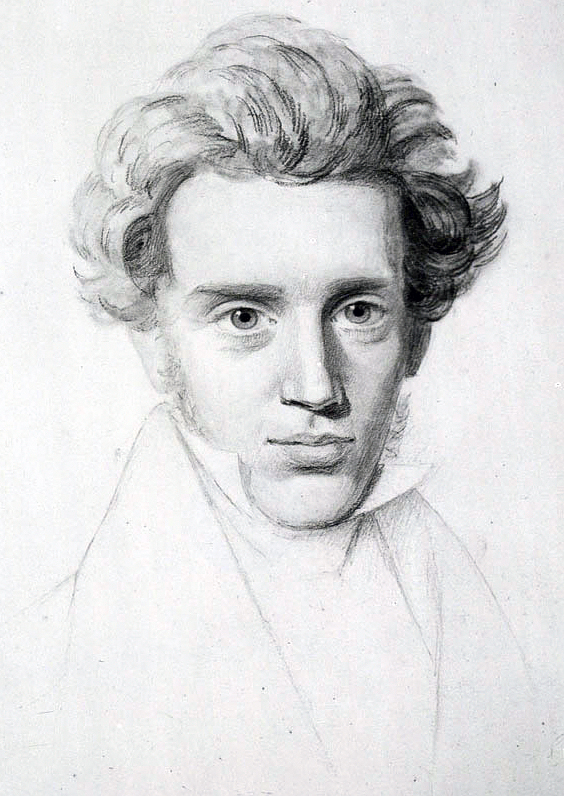

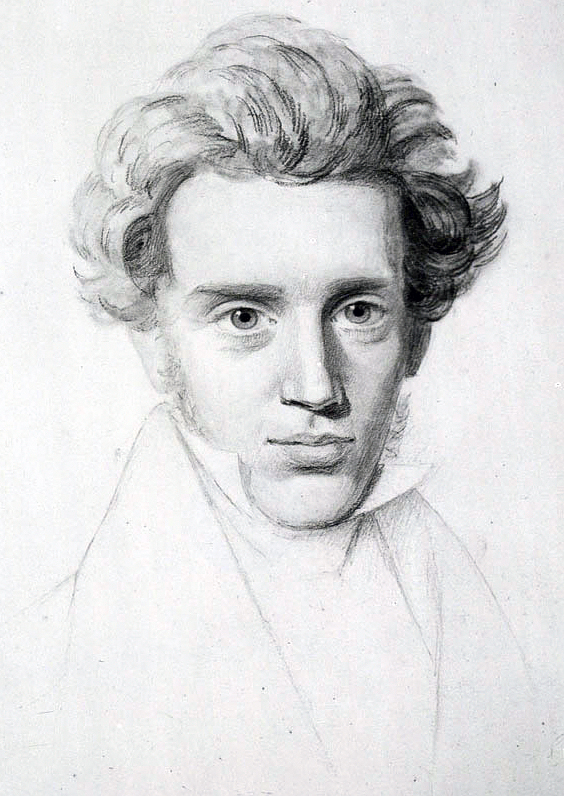

Heideggerians regarded Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard ( , , ; 5 May 1813 – 11 November 1855) was a Danish theologian, philosopher, poet, social critic, and religious author who is widely considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He wrote critical texts on ...

as, by far, the greatest philosophical contributor to Heidegger's own existentialist concepts. Heidegger's concepts of anxiety ('' Angst'') and mortality draw on Kierkegaard and are indebted to the way in which the latter lays out the importance of our subjective relation to truth, our existence in the face of death, the temporality of existence, and the importance of passionate affirmation of one's individual being-in-the-world

Martin Heidegger, the 20th-century German philosopher, produced a large body of work that intended a profound change of direction for philosophy. Such was the depth of change that he found it necessary to introduce many neologisms, often connected ...

.

Patricia J. Huntington claims that Heidegger's book ''Being and Time'' continued Kierkegaard's existential goal. Nevertheless, she argues that Heidegger began to distance himself from any existentialist thought.

Calvin Shrag argues Heidegger's early relationship with Kierkegaard as:

Hölderlin and Nietzsche

Friedrich Hölderlin

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (, ; ; 20 March 1770 – 7 June 1843) was a German poet and philosopher. Described by Norbert von Hellingrath as "the most German of Germans", Hölderlin was a key figure of German Romanticism. Part ...

and Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

were both important influences on Heidegger, and many of his lecture courses were devoted to one or the other, especially in the 1930s and 1940s. The lectures on Nietzsche focused on fragments posthumously published under the title ''The Will to Power

The will to power (german: der Wille zur Macht) is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The will to power describes what Nietzsche may have believed to be the main driving force in humans. However, the concept was never systematic ...

'', rather than on Nietzsche's published works. Heidegger read ''The Will to Power'' as the culminating expression of Western metaphysics, and the lectures are a kind of dialogue between the two thinkers.

This is also the case for the lecture courses devoted to the poetry of Friedrich Hölderlin, which became an increasingly central focus of Heidegger's work and thought. Heidegger grants to Hölderlin a singular place within the history of being and the history of Germany, as a herald whose thought is yet to be "heard" in Germany or the West. Many of Heidegger's works from the 1930s onwards include meditations on lines from Hölderlin's poetry, and several of the lecture courses are devoted to the reading of a single poem (see, for example, '' Hölderlin's Hymn "The Ister"'').

Heidegger and Eastern thought

Some writers on Heidegger's work see possibilities within it for dialogue with traditions of thought outside of Western philosophy, particularly East Asian thinking. Despite perceived differences between Eastern and Western philosophy, some of Heidegger's later work, particularly "A Dialogue on Language between a Japanese and an Inquirer", does show an interest in initiating such a dialogue. Heidegger himself had contact with a number of leading Japanese intellectuals, including members of the Kyoto School

The is the name given to the Japanese philosophical movement centered at Kyoto University that assimilated Western philosophy and religious ideas and used them to reformulate religious and moral insights unique to the East Asian cultural tradit ...

, notably Hajime Tanabe and Kuki Shūzō Kuki can refer to:

Locations

* Kuki, Isfahan, a village in Isfahan Province, Iran

* Kuki, Saitama, a city in Japan

Peoples and culture

* Kuki, or Thadou people, an ethnic tribe native to northeastern India (also Burma, where they are called ''Ch ...

. Reinhard May refers to Chang Chung-Yuan who stated (in 1977) "Heidegger is the only Western Philosopher who not only intellectually understands Tao

''Tao'' or ''Dao'' is the natural order of the universe, whose character one's intuition must discern to realize the potential for individual wisdom, as conceived in the context of East Asian philosophy, East Asian religions, or any other philo ...

, but has intuitively experienced the essence of it as well." May sees great influence of Taoism and Japanese scholars in Heidegger's work, although this influence is not acknowledged by the author. He asserts (1996): "The investigation concludes that Heidegger's work was significantly influenced by East Asian sources. It can be shown, moreover, that in particular instances Heidegger even appropriated wholesale and almost verbatim major ideas from the German translations of Daoist and Zen Buddhist classics. This clandestine textual appropriation of non-Western spirituality, the extent of which has gone undiscovered for so long, seems quite unparalleled, with far-reaching implications for our future interpretation of Heidegger's work."

Islam

Heidegger has been influential in research on the relationship between Western philosophy and the history of ideas in Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

, particularly for some scholars interested in Arabic philosophical medieval sources. These include the Lebanese philosopher and architectural theorist Nader El-Bizri, who, as well as focusing on the critique of the history of metaphysics (as an 'Arab Heideggerian'), also moves towards rethinking the notion of "dwelling" in the epoch of the modern unfolding of the essence of technology and ''Gestell'', and realizing what can be described as a "confluence of Western and Eastern thought" as well. El-Bizri has also taken a new direction in his engagement in 'Heidegger Studies' by way of probing the Arab/Levantine Anglophone reception of ''Sein und Zeit'' in 1937 as set in the Harvard doctoral thesis of the 20th century Lebanese thinker and diplomat Charles Malik

Charles Habib Malik (sometimes spelled ''Charles Habib Malik''; 11 February 1906 – 28 December 1987; ar, شارل مالك) was a Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher, and politician. He served as the Lebanese representative to the United ...

.

It is also claimed that the works of counter-enlightenment philosophers such as Heidegger, along with Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

and Joseph de Maistre, influenced Iran's Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his S ...

Islamist scholars, notably Ali Shariati. A clearer impact of Heidegger in Iran is associated with thinkers such as Reza Davari Ardakani

Reza Davari Ardakani ( fa, رضا داوری اردکانی; born 6 July 1933, in Ardakan) is an Iranian philosopher who was influenced by Martin Heidegger, and a distinguished emeritus professor of philosophy at the University of Tehran. He is ...

, Ahmad Fardid

Seyyed Ahmad Fardid ( fa, سید احمد فردید) (Born in 1910, Yazd – 16 August 1994, Tehran), born Ahmad Mahini Yazdi, was a prominent Iranian philosopher and a professor of Tehran University. He is considered to be among the philosop ...

, and Fardid's student Jalal Al-e-Ahmad

Seyyed Jalāl Āl-e-Ahmad ( fa, جلال آلاحمد; December 2, 1923September 9, 1969) was a prominent Iranian novelist, short-story writer, translator, philosopher, socio-political critic, Sociology, sociologist, as well as an Anthropology ...

, who have been closely associated with the unfolding of philosophical thinking in a Muslim modern theological legacy in Iran. This included the construction of the ideological foundations of the Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

and modern political Islam in its connections with theology.

Heidegger and the Nazi Party

The rectorate

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

was sworn in as Chancellor of Germany

The chancellor of Germany, officially the federal chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany,; often shortened to ''Bundeskanzler''/''Bundeskanzlerin'', / is the head of the federal government of Germany and the commander in chief of the Ge ...

on 30 January 1933. Heidegger was elected rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of the University of Freiburg

The University of Freiburg (colloquially german: Uni Freiburg), officially the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg (german: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg), is a public university, public research university located in Freiburg im Breisg ...

on 21 April 1933, and assumed the position the following day. On May 1, he joined the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

.

On 27 May 1933, Heidegger delivered his inaugural address, the ''Rektoratsrede'' ("The Self-assertion of the German University"), in a hall decorated with swastikas, with members of the Sturmabteilung

The (; SA; literally "Storm Detachment") was the original paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party. It played a significant role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s. Its primary purposes were providing protection for Nazi ral ...

and prominent Nazi Party officials present.[Sharpe, Matthew. "Rhetorical Action in Rektoratsrede: Calling Heidegger's Gefolgschaft." Philosophy & Rhetoric 51, no. 2 (2018): 176–201. doi:10.5325/philrhet.51.2.0176 url:doi.org/10.5325/philrhet.51.2.0176]

His tenure as rector was fraught with difficulties from the outset. Some Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

education officials viewed him as a rival, while others saw his efforts as comical. Some of Heidegger's fellow Nazis also ridiculed his philosophical writings as gibberish. He finally offered his resignation as rector on 23 April 1934, and it was accepted on 27 April. Heidegger remained a member of both the academic faculty and of the Nazi Party until the end of the war.[ Thomas Sheehan]

"Heidegger and the Nazis"

(), a review of Victor Farias' ''Heidegger et le nazisme''. Original article:

Philosophical historian Hans Sluga wrote:

Though as rector he prevented students from displaying an anti-Semitic poster at the entrance to the university and from holding a book burning, he kept in close contact with the Nazi student leaders and clearly signaled to them his sympathy with their activism.

In 1945, Heidegger wrote of his term as rector, giving the writing to his son Hermann; it was published in 1983:

The rectorate was an attempt to see something in the movement that had come to power, beyond all its failings and crudeness, that was much more far-reaching and that could perhaps one day bring a concentration on the Germans' Western historical essence. It will in no way be denied that at the time I believed in such possibilities and for that reason renounced the actual vocation of thinking in favor of being effective in an official capacity. In no way will what was caused by my own inadequacy in office be played down. But these points of view do not capture what is essential and what moved me to accept the rectorate.

Treatment of Husserl

Beginning in 1917, German-Jewish philosopher Edmund Husserl

, thesis1_title = Beiträge zur Variationsrechnung (Contributions to the Calculus of Variations)

, thesis1_url = https://fedora.phaidra.univie.ac.at/fedora/get/o:58535/bdef:Book/view

, thesis1_year = 1883

, thesis2_title ...

championed Heidegger's work, and helped Heidegger become his successor for the chair in philosophy at the University of Freiburg in 1928.

On 6 April 1933, the Gauleiter of Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden is ...

Province, Robert Wagner, suspended all Jewish government employees, including present and retired faculty at the University of Freiburg. Heidegger's predecessor as rector formally notified Husserl of his "enforced leave of absence" on 14 April 1933.

Heidegger became Rector of the University of Freiburg on 22 April 1933. The following week the national Reich law of 28 April 1933 replaced Reichskommissar Wagner's decree. The Reich law required the firing of Jewish professors from German universities, including those, such as Husserl, who had converted to Christianity. The termination of the retired professor Husserl's academic privileges thus did not involve any specific action on Heidegger's part.

Heidegger had by then broken off contact with Husserl, other than through intermediaries. Heidegger later claimed that his relationship with Husserl had already become strained after Husserl publicly "settled accounts" with Heidegger and Max Scheler

Max Ferdinand Scheler (; 22 August 1874 – 19 May 1928) was a German philosopher known for his work in phenomenology, ethics, and philosophical anthropology. Considered in his lifetime one of the most prominent German philosophers,Davis, Zachar ...

in the early 1930s.

Heidegger did not attend his former mentor's cremation in 1938. In 1941, under pressure from publisher Max Niemeyer, Heidegger agreed to remove the dedication to Husserl from ''Being and Time'' (restored in post-war editions).

Heidegger's behavior towards Husserl has provoked controversy. Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

initially suggested that Heidegger's behavior precipitated Husserl's death. She called Heidegger a "potential murderer". However, she later recanted her accusation.

In 1939, only a year after Husserl's death, Heidegger wrote in his ''Black Notebooks

The ''Black Notebooks'' (german: Schwarze Hefte) are a set of 34 (one missing) notebooks written by German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) between October 1931 and 1970. Originally a set of small notebooks with black covers in which Heid ...

'': "The more original and inceptive the coming decisions and questions become, the more inaccessible will they remain to this ewish'race'. Thus, Husserl's step toward phenomenological observation, and his rejection of psychological explanations and historiological reckoning of opinions, are of enduring importance—yet it never reaches into the domains of essential decisions", seeming to imply that Husserl's philosophy was limited purely because he was Jewish.

Post-rectorate period

After the failure of Heidegger's rectorship, he withdrew from most political activity, but remained a member of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

. In May 1934 he accepted a position on the Committee for the Philosophy of Law in the Academy for German Law ( Ausschuß für Rechtphilosophie der Akademie für Deutsches Recht), where he remained active until at least 1936.[Emmanuel Faye, Heidegger. ''Die Einführung des Nationalsozialismus in die Philosophie'', Berlin 2009, S. 275–278] The academy had official consultant status in preparing Nazi legislation such as the Nuremberg racial laws that came into effect in 1935. In addition to Heidegger, such Nazi notables as Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and lawyer who served as head of the General Government in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member of the German Workers' Party ...

, Julius Streicher

Julius Streicher (12 February 1885 – 16 October 1946) was a member of the Nazi Party, the ''Gauleiter'' (regional leader) of Franconia and a member of the '' Reichstag'', the national legislature. He was the founder and publisher of the virul ...

, Carl Schmitt and Alfred Rosenberg belonged to the Academy and served on this committee.In the majority of "research results," the Greeks appear as pure National Socialists. This overenthusiasm on the part of academics seems not even to notice that with such "results" it does National Socialism and its historical uniqueness no service at all, not that it needs this anyhow.

An important witness to Heidegger's continued allegiance to Nazism during the post-rectorship period is his former student Karl Löwith

Karl Löwith (9 January 1897 – 26 May 1973) was a German philosopher in the phenomenological tradition. A student of Husserl and Heidegger, he was one of the most prolific German philosophers of the twentieth century.

He is known for his two ...

, who met Heidegger in 1936 while Heidegger was visiting Rome. In an account set down in 1940 (though not intended for publication), Löwith recalled that Heidegger wore a swastika pin to their meeting, though Heidegger knew that Löwith was Jewish. Löwith also recalled that Heidegger "left no doubt about his faith in Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

", and stated that his support for Nazism was in agreement with the essence of his philosophy.

Heidegger rejected the "biologically grounded racism" of the Nazis, replacing it with linguistic-historical heritage.

Post-war period

After the end of World War II, Heidegger was summoned to appear at a denazification

Denazification (german: link=yes, Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by remov ...

hearing. Heidegger's former lover Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

spoke on his behalf at this hearing, while Karl Jaspers

Karl Theodor Jaspers (, ; 23 February 1883 – 26 February 1969) was a German-Swiss psychiatrist and philosopher who had a strong influence on modern theology, psychiatry, and philosophy. After being trained in and practicing psychiatry, Jasper ...

spoke against him. He was charged on four counts, dismissed from the university and declared a "follower" ('' Mitläufer'') of Nazism.industrialisation

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

, including the treatment of animals by factory farming

Intensive animal farming or industrial livestock production, also known by its opponents as factory farming and macro-farms, is a type of intensive agriculture, specifically an approach to animal husbandry designed to maximize production, while ...

. For instance in a lecture delivered at Bremen in 1949, Heidegger said: "Agriculture is now a motorized food industry, the same thing in its essence as the production of corpses in the gas chambers and the extermination camps, the same thing as blockades and the reduction of countries to famine, the same thing as the manufacture of hydrogen bombs."Paul Celan

Paul Celan (; ; 23 November 1920 – c. 20 April 1970) was a Romanian-born German-language poet and translator. He was born as Paul Antschel to a Jewish family in Cernăuți (German: Czernowitz), in the then Kingdom of Romania (now Chernivtsi, U ...

, a concentration camp survivor. Having corresponded since 1956, Celan visited Heidegger at his country retreat and wrote an enigmatic poem about the meeting, which some interpret as Celan's wish for Heidegger to apologize for his behavior during the Nazi era.

''Der Spiegel'' interview

On 23 September 1966, Heidegger was interviewed by Rudolf Augstein