Hardbop on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hard bop is a subgenre of

A key recording in the early development of hard bop was Silver's composition " The Preacher", which was considered "old-timey" or "corny", such that

A key recording in the early development of hard bop was Silver's composition " The Preacher", which was considered "old-timey" or "corny", such that

In 1956, The Jazz Messengers recorded an album titled ''

In 1956, The Jazz Messengers recorded an album titled ''

Scott Yanow described hard bop in the late 1960s as "running out of gas." Blue Note Records' sale and decline in the late 1960s and early 1970s, combined with the rapid ascendance of

Scott Yanow described hard bop in the late 1960s as "running out of gas." Blue Note Records' sale and decline in the late 1960s and early 1970s, combined with the rapid ascendance of

jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

that is an extension of bebop

Bebop or bop is a style of jazz developed in the early-to-mid-1940s in the United States. The style features compositions characterized by a fast tempo, complex chord progressions with rapid chord changes and numerous changes of key, instrumen ...

(or "bop") music. Journalists and record companies began using the term in the mid-1950s to describe a new current within jazz that incorporated influences from rhythm and blues

Rhythm and blues, frequently abbreviated as R&B or R'n'B, is a genre of popular music that originated in African-American communities in the 1940s. The term was originally used by record companies to describe recordings marketed predominantly ...

, gospel music

Gospel music is a traditional genre of Christian music, and a cornerstone of Christian media. The creation, performance, significance, and even the definition of gospel music varies according to culture and social context. Gospel music is com ...

, and blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afr ...

, especially in saxophone

The saxophone (often referred to colloquially as the sax) is a type of single-reed woodwind instrument with a conical body, usually made of brass. As with all single-reed instruments, sound is produced when a reed on a mouthpiece vibrates to pr ...

and piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keyboa ...

playing.

David H. Rosenthal contends in his book ''Hard Bop'' that the genre is, to a large degree, the natural creation of a generation of African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

musicians who grew up at a time when bop and rhythm and blues

Rhythm and blues, frequently abbreviated as R&B or R'n'B, is a genre of popular music that originated in African-American communities in the 1940s. The term was originally used by record companies to describe recordings marketed predominantly ...

were the dominant forms of black American music. Prominent hard bop musicians included Horace Silver

Horace Ward Martin Tavares Silver (September 2, 1928 – June 18, 2014) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and arranger, particularly in the hard bop style that he helped pioneer in the 1950s.

After playing tenor saxophone and piano at sch ...

, Clifford Brown

Clifford Benjamin Brown (October 30, 1930 – June 26, 1956) was an American jazz trumpeter and composer. He died at the age of 25 in a car accident, leaving behind four years' worth of recordings. His compositions "Sandu", "Joy Spring", an ...

, Charles Mingus

Charles Mingus Jr. (April 22, 1922 – January 5, 1979) was an American jazz upright bassist, pianist, composer, bandleader, and author. A major proponent of collective improvisation, he is considered to be one of the greatest jazz musicians and ...

, Art Blakey

Arthur Blakey (October 11, 1919 – October 16, 1990) was an American jazz drummer and bandleader. He was also known as Abdullah Ibn Buhaina after he converted to Islam for a short time in the late 1940s.

Blakey made a name for himself in the 1 ...

, Cannonball Adderley

Julian Edwin "Cannonball" Adderley (September 15, 1928August 8, 1975) was an American jazz alto saxophonist of the hard bop era of the 1950s and 1960s.

Adderley is perhaps best remembered for the 1966 soul jazz single "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy", whi ...

, Miles Davis

Miles Dewey Davis III (May 26, 1926September 28, 1991) was an American trumpeter, bandleader, and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music. Davis adopted a variety of music ...

, John Coltrane

John William Coltrane (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967) was an American jazz saxophonist

The saxophone (often referred to colloquially as the sax) is a type of single-reed woodwind instrument with a conical body, usually made of br ...

, Hank Mobley

Henry "Hank" Mobley (July 7, 1930 – May 30, 1986) was an American hard bop and soul jazz tenor saxophonist and composer. Mobley was described by Leonard Feather as the "middleweight champion of the tenor saxophone", a metaphor used to descr ...

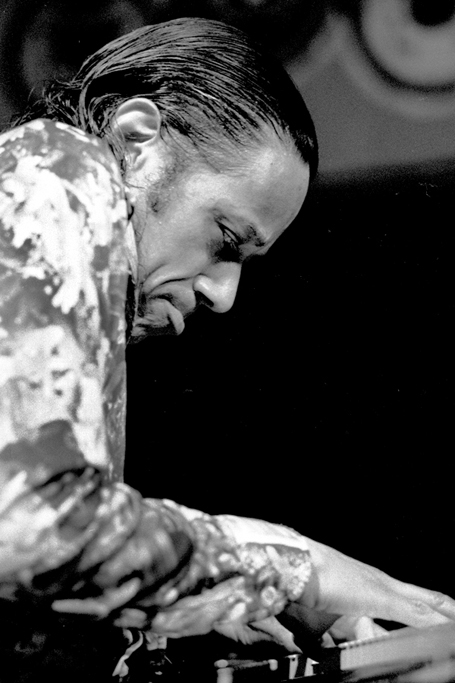

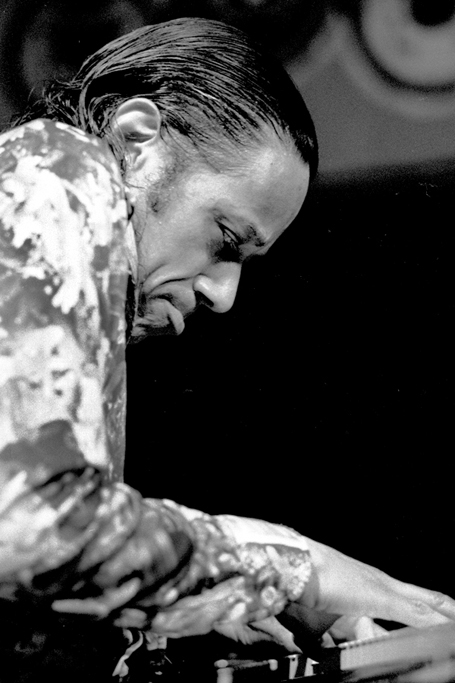

, Thelonious Monk

Thelonious Sphere Monk (, October 10, 1917 – February 17, 1982) was an American jazz pianist and composer. He had a unique improvisational style and made numerous contributions to the standard jazz repertoire, including " 'Round Midnight", "B ...

and Lee Morgan

Edward Lee Morgan (July 10, 1938 – February 19, 1972) was an American jazz trumpeter and composer.

One of the key hard bop musicians of the 1960s, Morgan came to prominence in his late teens, recording on John Coltrane's '' Blue Train'' (1 ...

.

Musical style

Hard bop is sometimes referred to as "funky hard bop". The "funky" label refers to the rollicking, rhythmic feeling associated with the style. The descriptor is also used to describesoul jazz

Soul jazz or funky jazz is a subgenre of jazz that incorporates strong influences from hard bop, blues, soul, gospel and rhythm and blues. Soul jazz is often characterized by organ trios featuring the Hammond organ and small combos including ten ...

, which is commonly associated with hard bop. According to Mark C. Gridley, soul jazz more specifically refers to music with "an earthy, bluesy melodic concept and... repetitive, dance-like rhythms. Some listeners make no distinction between 'soul-jazz' and 'funky hard bop,' and many musicians don't consider 'soul-jazz' to be continuous with 'hard bop.'" The term "soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun ''soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest attes ...

" suggests the church, and traditional gospel music elements such as "amen chords" (the plagal cadence

In Western musical theory, a cadence (Latin ''cadentia'', "a falling") is the end of a phrase in which the melody or harmony creates a sense of full or partial resolution, especially in music of the 16th century onwards.Don Michael Randel (1999 ...

) and triadic harmonies that seemed to suddenly appear in jazz during the era. Leroi Jones

Amiri Baraka (born Everett Leroy Jones; October 7, 1934 – January 9, 2014), previously known as LeRoi Jones and Imamu Amear Baraka, was an American writer of poetry, drama, fiction, essays and music criticism. He was the author of numerous bo ...

noted a combination of "wider and harsher tones" with "accompanying piano chords hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

became more basic and simplified." He cited saxophonist Sonny Rollins

Walter Theodore "Sonny" Rollins (born September 7, 1930) is an American jazz tenor saxophonist who is widely recognized as one of the most important and influential jazz musicians. In a seven-decade career, he has recorded over sixty albums as a ...

' playing as one of the best examples of the style. Jazz critic Scott Yanow distinguished hard bop from the broader world of bop by saying that " mpos could be just as blazing but the melodies were generally simpler, the musicians (particularly the saxophonists and pianists) tended to be familiar with (and open to the influence of) rhythm & blues and the bass players (rather than always being stuck in the role of a metronome) were beginning to gain a little more freedom and solo space."

Hard bop has been seen by some critics as a response to cool jazz

Cool jazz is a style of modern jazz music that arose in the United States after World War II. It is characterized by relaxed tempos and lighter tone, in contrast to the fast and complex bebop style. Cool jazz often employs formal arrangements and ...

and West Coast jazz

West Coast jazz refers to styles of jazz that developed in Los Angeles and San Francisco during the 1950s. West Coast jazz is often seen as a subgenre of cool jazz, which consisted of a calmer style than bebop or hard bop. The music relied rela ...

. As Paul Tanner, Maurice Gerow, and David Megill explain, "the hard bop school... saw the new instrumentation and compositional devices used by cool musicians as gimmicks rather than valid developments of the jazz tradition." However, Shelly Manne

Sheldon "Shelly" Manne (June 11, 1920 – September 26, 1984) was an American jazz drummer. Most frequently associated with West Coast jazz, he was known for his versatility and also played in a number of other styles, including Dixieland, s ...

suggested that cool jazz and hard bop simply reflected their respective geographic environments: the relaxed cool jazz style reflected a more relaxed lifestyle in California, while driving bop typified the New York scene. Some writers, such as James Lincoln Collier

James Lincoln Collier (born June 29, 1928) is an American journalist, professional musician, jazz commentator, and author. Many of his non-fiction titles focus on music theory and the history of jazz.

He and his brother Christopher Collier, a h ...

, suggest that the style was an attempt to recapture jazz as a form of African American expression. Whether or not this was the intent, many musicians quickly adopted the style, regardless of race.

History

Origins

According toNat Hentoff

Nathan Irving Hentoff (June 10, 1925 – January 7, 2017) was an American historian, novelist, jazz and country music critic, and syndicated columnist for United Media. Hentoff was a columnist for ''The Village Voice'' from 1958 to 2009. Fol ...

in his 1957 liner notes for the Art Blakey

Arthur Blakey (October 11, 1919 – October 16, 1990) was an American jazz drummer and bandleader. He was also known as Abdullah Ibn Buhaina after he converted to Islam for a short time in the late 1940s.

Blakey made a name for himself in the 1 ...

Columbia LP entitled ''Hard Bop'', the phrase was originated by music critic and pianist John Mehegan

John Francis Mehegan (June 6, 1916 – April 3, 1984) was an American jazz pianist, lecturer and critic.

Early life

Mehegan was born in Hartford, Connecticut, on June 6, 1916, although he sometimes gave the year as 1920. He began playing the vi ...

, jazz reviewer of the ''New York Herald Tribune

The ''New York Herald Tribune'' was a newspaper published between 1924 and 1966. It was created in 1924 when Ogden Mills Reid of the ''New-York Tribune'' acquired the ''New York Herald''. It was regarded as a "writer's newspaper" and competed ...

'' at that time. Hard bop first developed in the mid-1950s, and is generally seen as originating with the Jazz Messengers

The Jazz Messengers were a jazz combo that existed for over thirty-five years beginning in the early 1950s as a collective, and ending when long-time leader and founding drummer Art Blakey died in 1990. Blakey led or co-led the group from the o ...

, a quartet led by pianist Horace Silver

Horace Ward Martin Tavares Silver (September 2, 1928 – June 18, 2014) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and arranger, particularly in the hard bop style that he helped pioneer in the 1950s.

After playing tenor saxophone and piano at sch ...

and drummer Art Blakey

Arthur Blakey (October 11, 1919 – October 16, 1990) was an American jazz drummer and bandleader. He was also known as Abdullah Ibn Buhaina after he converted to Islam for a short time in the late 1940s.

Blakey made a name for himself in the 1 ...

. Alternatively, Anthony Macias points to Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

as an early center in the rise of bop and hard bop, noting Detroit musicians Barry Harris

Barry Doyle Harris (December 15, 1929 – December 8, 2021) was an American jazz pianist, bandleader, composer, arranger, and educator. He was an exponent of the bebop style.

Life and career

Harris was born in Detroit, Michigan, on December ...

and Kenny Burrell

Kenneth Earl Burrell (born July 31, 1931) is an American jazz guitarist known for his work on numerous top jazz labels: Prestige, Blue Note, Verve, CTI, Muse, and Concord. His collaborations with Jimmy Smith were notable, and produced the 1965 ...

and the fact Miles Davis lived in the city from 1953 to 1954. Billy Mitchell

William Lendrum Mitchell (December 29, 1879 – February 19, 1936) was a United States Army officer who is regarded as the father of the United States Air Force.

Mitchell served in France during World War I and, by the conflict's end, command ...

, a tenor saxophone player, organized a band that played at the Blue Bird Inn during the early 1950s that "anchored the city's Jazz scene" and attracted hard bop musicians to the city.

Michael Cuscuna

Michael Cuscuna (born September 20, 1949 in Stamford, Connecticut, United States) is an American jazz record producer and writer. He is the co-founder of Mosaic Records and a discographer of Blue Note Records.

Cuscuna played drums, saxophone and ...

maintains that Silver and Blakey's efforts were in response to the New York bebop scene:

Both Art and Horace were very, very aware of what they wanted to do. They wanted to get away from the jazz scene of the early '50s, which was the Birdland scene — you hireDavid Rosenthal sees the development of hard bop as a response to both a decline in bebop and the rise of rhythm and blues:Phil Woods Philip Wells Woods (November 2, 1931 – September 29, 2015) was an American jazz alto saxophonist, clarinetist, bandleader, and composer. Biography Woods was born in Springfield, Massachusetts. After inheriting a saxophone at age 12, he began ...orCharlie Parker Charles Parker Jr. (August 29, 1920 – March 12, 1955), nicknamed "Bird" or "Yardbird", was an American jazz saxophonist, band leader and composer. Parker was a highly influential soloist and leading figure in the development of bebop, a form ...orJ. J. Johnson J.J. Johnson (January 22, 1924 – February 4, 2001), born James Louis Johnson and also known as Jay Jay Johnson, was an American jazz trombonist, composer and arranger. Johnson was one of the earliest trombonists to embrace bebop. Biograph ..., they come and sit in with the house rhythm section, and they only play blues andstandards Standard may refer to: Symbols * Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs * Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification Norms, conventions or requirements * Standard (metrology), an object th ...that everybody knows. There's no rehearsal, there's no thought given to the audience. Both Horace and Art knew that the only way to get the jazz audience back and make it bigger than ever was to really make music that was memorable and planned, where you consider the audience and keep everything short. They really liked digging into blues and gospel, things with universal appeal. So they put together what was to be called the Jazz Messengers.

The early fifties saw an extremely dynamicRhythm and Blues Rhythm and blues, frequently abbreviated as R&B or R'n'B, is a genre of popular music that originated in African-American communities in the 1940s. The term was originally used by record companies to describe recordings marketed predominantly ...scene take shape.... This music, and not cool jazz, was what chronologically separated bebop and hard bop in ghettos. Young jazz musicians, of course, enjoyed and listened to these R & B sounds which, among other things, began the amalgam of blues and gospel that would later be dubbed 'soul music Soul music is a popular music genre that originated in the African American community throughout the United States in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It has its roots in African-American gospel music and rhythm and blues. Soul music became po ....' And it is in this vigorously creative black pop music, at a time when bebop seemed to have lost both its direction and its audience, that some of hard bop's roots may be found.

A key recording in the early development of hard bop was Silver's composition " The Preacher", which was considered "old-timey" or "corny", such that

A key recording in the early development of hard bop was Silver's composition " The Preacher", which was considered "old-timey" or "corny", such that Blue Note

In jazz and blues, a blue note is a note that—for expressive purposes—is sung or played at a slightly different pitch from standard. Typically the alteration is between a quartertone and a semitone, but this varies depending on the musical co ...

head Alfred Lion

Alfred Lion (born Alfred Löw; April 21, 1908 – February 2, 1987), was an American record executive who co-founded the jazz record label Blue Note in 1939. Lion retired in 1967, having sold the company, after producing recordings by leading music ...

was hesitant to record the song. However, the song became a successful hit.

Miles Davis, who had performed the title track of his album ''Walkin'

''Walkin'' (PRLP 7076) is a Miles Davis compilation album released in March 1957 by Prestige Records. The album compiles material previously released on two 10 inch LPs in 1954 (''Miles Davis All-Star Sextet'' and Side One of ''Miles Davis Quinte ...

'' at the inaugural Newport Jazz Festival

The Newport Jazz Festival is an annual American multi-day jazz music festival held every summer in Newport, Rhode Island. Elaine Lorillard established the festival in 1954, and she and husband Louis Lorillard financed it for many years. They hire ...

in 1954, would form the Miles Davis Quintet

The Miles Davis Quintet was an American jazz band from 1955 to early 1969 led by Miles Davis. The quintet underwent frequent personnel changes toward its metamorphosis into a different ensemble in 1969. Most references pertain to two distinct and ...

with John Coltrane

John William Coltrane (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967) was an American jazz saxophonist

The saxophone (often referred to colloquially as the sax) is a type of single-reed woodwind instrument with a conical body, usually made of br ...

in 1955, becoming prominent in hard bop before moving on to other styles. Other early documents were the two volumes of the Blue Note albums

An album is a collection of audio recordings issued on compact disc (CD), vinyl, audio tape, or another medium such as digital distribution. Albums of recorded sound were developed in the early 20th century as individual 78 rpm records coll ...

'' A Night at Birdland'', also from 1954, recorded by the Jazz Messengers at Birdland months before the Davis set at Newport. Clifford Brown

Clifford Benjamin Brown (October 30, 1930 – June 26, 1956) was an American jazz trumpeter and composer. He died at the age of 25 in a car accident, leaving behind four years' worth of recordings. His compositions "Sandu", "Joy Spring", an ...

, the trumpeter on the Birdland albums, formed the Brown-Roach Quintet with drummer Max Roach

Maxwell Lemuel Roach (January 10, 1924 – August 16, 2007) was an American jazz Jazz drumming, drummer and composer. A pioneer of bebop, he worked in many other styles of music, and is generally considered one of the most important drummers in h ...

. Among the pianists in the band were Richie Powell

Richard Powell (September 5, 1931 – June 26, 1956) was an American jazz pianist, composer, and arranger. He was not assisted in his musical development by Bud, his older and better known brother, but both played predominantly in the bebop style. ...

and Carl Perkins

Carl Lee Perkins (April 9, 1932 – January 19, 1998)#nytimesobit, Pareles. was an American guitarist, singer and songwriter. A rockabilly great and pioneer of rock and roll, he began his recording career at the Sun Studio, in Memphis, Tennes ...

, both of whom died at a young age.

Mainstream

David Ake notes that by the mid-1950s, "the bop world clearly was not the 'closed' circle it had been in its earliest days." This coincided with a competitive spirit among bop musicians to play with "virtuousity and complexity," along with what Ake calls "jazz masculinity." The broadening influence of hard bop coincided with a generation of jazz pianists who rose to prominence in the late 1950s – among themTommy Flanagan

Thomas Lee Flanagan (March 16, 1930 – November 16, 2001) was an American jazz pianist and composer. He grew up in Detroit, initially influenced by such pianists as Art Tatum, Teddy Wilson, and Nat King Cole, and then by bebop musicians. ...

, Kenny Drew

Kenneth Sidney "Kenny" Drew (August 28, 1928 – August 4, 1993) was an American-Danish jazz pianist.

Biography

Drew was born in New York City, United States, and received piano lessons from the age of five.Feather, Leonard, & Ira Gitler (2 ...

, and Wynton Kelly

Wynton Charles Kelly (December 2, 1931 – April 12, 1971) was an American jazz pianist and composer. He is known for his lively, blues-based playing and as one of the finest accompanists in jazz. He began playing professionally at the age of ...

– who took "altered" approaches to bebop. Although these musicians did not work exclusively or specifically within hard bop, their association with hard bop saxophone players put them within the genre's broader circle. West Coast Jazz's diminishing influence during the late 1950s accelerated hard bop's rise to prominence, while the transition to 33-RPM records facilitated the shifts toward longer solos that were typical of hard bop albums. During a fifteen-year stretch from 1952 to 1967, Blue Note Records recruited musicians and promoted hard bop described by Yanow as "classy."

A critical album that cemented hard bop's mainstream presence in jazz was ''A Blowin' Session

''Johnny Griffin Vol. 2'' (also known as ''A Blowin' Session'') is an album by jazz saxophonist Johnny Griffin, recorded in April 1957 and released in September or October of the same year on the Blue Note label. It was reissued in 1999, featuring ...

'' (1957), including saxophonists Johnny Griffin

John Arnold Griffin III (April 24, 1928 – July 25, 2008) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist. Nicknamed "the Little Giant" for his short stature and forceful playing, Griffin's career began in the mid-1940s and continued until the month of ...

, John Coltrane, and Hank Mobley; trumpeter Lee Morgan; pianist Wynton Kelly; bassist Paul Chambers

Paul Laurence Dunbar Chambers Jr. (April 22, 1935 – January 4, 1969) was an American jazz double bassist. A fixture of rhythm sections during the 1950s and 1960s, he has become one of the most widely-known jazz bassists of the hard bop era. ...

; and Art Blakey. Described by Al Campbell as "one of the greatest hard bop jam sessions ever recorded" and "filled with infectious passion and camaraderie," it was the only studio session ever recorded including all three saxophonists. It cemented "Coltrane's ability to navigate complex chord changes over a fast tempo" and is associated with Griffin's reputation as "the world's fastest saxophonist."

In 1956, The Jazz Messengers recorded an album titled ''

In 1956, The Jazz Messengers recorded an album titled ''Hard Bop

Hard bop is a subgenre of jazz that is an extension of bebop (or "bop") music. Journalists and record companies began using the term in the mid-1950s to describe a new current within jazz that incorporated influences from rhythm and blues, gospe ...

'', which was released in 1957, including Bill Hardman

William Franklin Hardman Jr. (April 6, 1933 – December 6, 1990) was an American jazz trumpeter and flugelhornist who chiefly played hard bop. He was married to Roseline and they had a daughter Nadege.

Career

Hardman was born and grew ...

on trumpet and saxophonist Jackie McLean

John Lenwood "Jackie" McLean (May 17, 1931 – March 31, 2006) was an American jazz alto saxophonist, composer, bandleader, and educator, and is one of the few musicians to be elected to the ''DownBeat'' Hall of Fame in the year of their deat ...

, with a mix of hard bop compositions and jazz standard

Jazz standards are musical compositions that are an important part of the musical repertoire of jazz musicians, in that they are widely known, performed, and recorded by jazz musicians, and widely known by listeners. There is no definitive lis ...

s. Shortly after, in 1958, The Jazz Messengers, with a new line-up including Lee Morgan on trumpet and Benny Golson on saxophone, recorded the quintessential hard bop album ''Moanin'

''Moanin'' (originally titled ''Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers'') is a jazz album by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers recorded in 1958 for the Blue Note label and released in 1959.

Background

This was Blakey's first album for Blue Note ...

'', with the album pioneering in soul jazz. Golson and Morgan formed their own bands and produced further records in the hard bop genre: Golson's Jazztet with Art Farmer

Arthur Stewart Farmer (August 21, 1928 – October 4, 1999) was an American jazz trumpeter and flugelhorn player. He also played flumpet, a trumpet–flugelhorn combination especially designed for him. He and his identical twin brother, double ...

on trumpet recorded the album ''Meet the Jazztet

''Meet the Jazztet'' is an album by the Jazztet, led by trumpeter Art Farmer and saxophonist Benny Golson featuring performances recorded in 1960 and originally released on the Argo label.

'' in 1960, which was given a five-star rating by AllMusic

AllMusic (previously known as All Music Guide and AMG) is an American online music database. It catalogs more than three million album entries and 30 million tracks, as well as information on musicians and bands. Initiated in 1991, the databas ...

, and Morgan explored hard bop and sister genres in records like ''The Sidewinder

''The Sidewinder'' is a 1964 album by the jazz trumpeter Lee Morgan, recorded at the Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, U.S. It was released on the Blue Note label as BLP 4157 (mono) and BST 84157 ( stereo).

The title track ...

'', known for its "funky, danceable groov that drew from soul-jazz, Latin boogaloo

Boogaloo or bugalú (also: shing-a-ling, Latin boogaloo, Latin R&B) is a music genre, genre of Latin music and dance which was popular in the United States in the 1960s. Boogaloo originated in New York City mainly among teenage African Americans ...

, blues, and R&B." Morgan's albums attracted rising stars in the jazz world, particularly saxophonists Joe Henderson

Joe Henderson (April 24, 1937 – June 30, 2001) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist. In a career spanning more than four decades, Henderson played with many of the leading American players of his day and recorded for several prominent l ...

and Wayne Shorter

Wayne Shorter (born August 25, 1933) is an American jazz saxophonist and composer. Shorter came to prominence in the late 1950s as a member of, and eventually primary composer for, Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers. In the 1960s, he joined Miles Davi ...

; Morgan formed a "long-standing partnership" with the latter.

Meanwhile, in the late 1950s to early 1960s John Coltrane was a prominent saxophonist within the hard bop genre, with albums such as '' Blue Train'' and ''Giant Steps

''Giant Steps'' is the fifth studio album by jazz musician John Coltrane as leader. It was released in February 1960 on Atlantic Records. This was his first album as leader for Atlantic Records, with which he had signed a new contract the previou ...

'' exemplifying his ability to play within this style. His album ''Stardust'' (1958), for instance, included a young Freddie Hubbard

Frederick Dewayne Hubbard (April 7, 1938 – December 29, 2008) was an American jazz trumpeter. He played bebop, hard bop, and post-bop styles from the early 1960s onwards. His unmistakable and influential tone contributed to new perspectives fo ...

on trumpet, who would go on to become "a hard bop stylist." ''Blue Train'' was described by Richard Havers as "Coltrane’s Hard-Bop Masterpiece," although an edit made to one of the album's records caused controversy following disapproval from sound engineer Rudy Van Gelder. In the early to mid-1960s, prior to his death, Coltrane experimented in free jazz but again drew influences from hard bop in his 1965 album ''A Love Supreme

''A Love Supreme'' is an album by American jazz saxophonist John Coltrane. He recorded it in one session on December 9, 1964, at Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, leading a quartet featuring pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Ga ...

''. Coltrane was a longtime member of Miles Davis' band, which bridged the gap between hard bop and modal jazz with albums such as ''Milestones

A milestone is a marker of distance along roads.

Milestone may also refer to:

Measurements

*Milestone (project management), metaphorically, markers of reaching an identifiable stage in any task or the project

*Software release life cycle state, s ...

'' and ''Kind of Blue

''Kind of Blue'' is a studio album by American jazz trumpeter, composer, and bandleader Miles Davis. It was recorded on March 2 and April 22, 1959, at Columbia's 30th Street Studio in New York City, and released on August 17 of that year by Co ...

''. These albums represented a transition toward more experimental jazz, but Davis maintained core ideas of hard bop, such as the "call-and-response theme" found on one of ''Kind of Blue''So What

So What may refer to:

Law

*Demurrer, colloquially called a "So what?" pleading

Music Albums

* ''So What'' (Anti-Nowhere League album) or the 1981 title song (see below), 2000

* '' So What?: Early Demos and Live Abuse'', by Anti-Nowhere League, ...

." The earlier album ''Milestones'' was described as "indebted to hard bop" due to its "fast speeds, angular phrases and driving rhythms."

In the early 1960s, Joe Henderson formed a band with Kenny Dorham

McKinley Howard "Kenny" Dorham (August 30, 1924 – December 5, 1972) was an American jazz trumpeter, singer, and composer. Dorham's talent is frequently lauded by critics and other musicians, but he never received the kind of attention or public ...

, which recorded for Blue Note Records, and played extensively as a sideman in the bands of Horace Silver and Herbie Hancock

Herbert Jeffrey Hancock (born April 12, 1940) is an American jazz pianist, keyboardist, bandleader, and composer. Hancock started his career with trumpeter Donald Byrd's group. He shortly thereafter joined the Miles Davis Quintet, where he help ...

; however, he received less recognition after he moved to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

and began recording for Milestone

A milestone is a numbered marker placed on a route such as a road, railway line, canal or boundary. They can indicate the distance to towns, cities, and other places or landmarks; or they can give their position on the route relative to so ...

. Other hard bop musicians went to Europe, such as pianist Bud Powell

Earl Rudolph "Bud" Powell (September 27, 1924 – July 31, 1966) was an American jazz pianist and composer. Along with Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Kenny Clarke and Dizzy Gillespie, Powell was a leading figure in the development of modern ...

(elder brother of Richie Powell) in 1959 and saxophonist Dexter Gordon

Dexter Gordon (February 27, 1923 – April 25, 1990) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist, composer, bandleader, and actor. He was among the most influential early bebop musicians, which included other greats such as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gi ...

in 1962. Powell, a bebop pianist, continued to record albums in the early 1960s, while Gordon's ''Our Man in Paris

''Our Man in Paris'' is a 1963 jazz album by saxophonist Dexter Gordon. The album's title refers to where the recording was made, Gordon (who had moved to Copenhagen a year earlier) teaming up with fellow expatriates Bud Powell and Kenny Clark ...

'' became "one of his most iconic albums" for Blue Note.

Other musicians who contributed to the hard bop style include Donald Byrd

Donaldson Toussaint L'Ouverture Byrd II (December 9, 1932 – February 4, 2013) was an American jazz and rhythm & blues trumpeter and vocalist. A sideman for many other jazz musicians of his generation, Byrd was one of the few hard bop m ...

, Tina Brooks

Harold Floyd "Tina" Brooks (June 7, 1932 – August 13, 1974) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist and composer best remembered for his work in the hard bop style.

Early years

Harold Floyd Brooks was born in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and ...

, Sonny Clark

Conrad Yeatis "Sonny" Clark (July 21, 1931 – January 13, 1963) was an American jazz pianist and composer who mainly worked in the hard bop idiom.

Early life

Clark was born and raised in Herminie, Pennsylvania, a coal mining town east of Pit ...

, Lou Donaldson

Lou Donaldson (born November 1, 1926) is an American retired jazz Alto saxophone, alto saxophonist. He is best known for his soulful, bluesy approach to playing the alto saxophone, although in his formative years he was, as many were of the bebop ...

, Blue Mitchell

Richard Allen "Blue" Mitchell (March 13, 1930 – May 21, 1979) was an American trumpeter and composer who worked in jazz, rhythm and blues, soul, rock and funk. He recorded albums as leader and sideman for Riverside, Mainstream Records, and Blu ...

, Sonny Rollins

Walter Theodore "Sonny" Rollins (born September 7, 1930) is an American jazz tenor saxophonist who is widely recognized as one of the most important and influential jazz musicians. In a seven-decade career, he has recorded over sixty albums as a ...

, and Sonny Stitt

Edward Hammond Boatner Jr. (February 2, 1924 – July 22, 1982), known professionally as Sonny Stitt, was an American jazz saxophonist of the bebop/hard bop idiom. Known for his warm tone, he was one of the best-documented saxophonists of his ...

.

David Rosenthal considers six albums among the high points of the hard bop era: ''Ugetsu

, is a 1953 Japanese historical drama and fantasy film directed by Kenji Mizoguchi starring Masayuki Mori and Machiko Kyō. It is based on two stories in Ueda Akinari's 1776 book of the same name, combining elements of the ''jidaigeki'' (peri ...

'', ''Kind of Blue'', ''Saxophone Colossus

''Saxophone Colossus'' is the sixth studio album by American jazz saxophonist Sonny Rollins. Perhaps Rollins's best-known album, it is often considered his breakthrough record. It was recorded monophonically on June 22, 1956, with producer Bob W ...

, Let Freedom Ring

''Let Freedom Ring'' is an album by jazz saxophonist Jackie McLean, recorded in 1962 and released on the Blue Note label.

,'' ''Mingus Ah Um

''Mingus Ah Um'' is a studio album by American jazz musician Charles Mingus which was released in October 1959 by Columbia Records. It was his first album recorded for Columbia. The cover features a painting by S. Neil Fujita. The title is a corrup ...

'', and ''Brilliant Corners

''Brilliant Corners'' is a studio album by American jazz musician Thelonious Monk. It was his third album for Riverside Records, and the first, for this label, to include his own compositions. The complex title track required over a dozen takes ...

'', referring to these as being some of the genre's "masterpieces."

Decline and revival

Scott Yanow described hard bop in the late 1960s as "running out of gas." Blue Note Records' sale and decline in the late 1960s and early 1970s, combined with the rapid ascendance of

Scott Yanow described hard bop in the late 1960s as "running out of gas." Blue Note Records' sale and decline in the late 1960s and early 1970s, combined with the rapid ascendance of soul jazz

Soul jazz or funky jazz is a subgenre of jazz that incorporates strong influences from hard bop, blues, soul, gospel and rhythm and blues. Soul jazz is often characterized by organ trios featuring the Hammond organ and small combos including ten ...

and fusion

Fusion, or synthesis, is the process of combining two or more distinct entities into a new whole.

Fusion may also refer to:

Science and technology Physics

*Nuclear fusion, multiple atomic nuclei combining to form one or more different atomic nucl ...

, largely replaced hard bop's prevalence within jazz, although bop would see a major revival in the 1980s known as the Young Lions Movement. Yanow also attributes hard bop's temporary decline in the 1970s to " e rise of commercial rock and the consolidation of most of the independent record labels." With rock groups such as The Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatles, most influential band of al ...

capturing hard bop's charisma and avant-garde jazz

Avant-garde jazz (also known as avant-jazz and experimental jazz) is a style of music and improvisation that combines avant-garde art music and composition with jazz. It originated in the early 1950s and developed through to the late 1960s. Orig ...

, which had limited appeal outside jazz circles, bringing "division and controversy into the jazz community," Davis and other former hard boppers left the genre, only for the new fusion genre to itself shrink within the next decade.

Davis led other jazz musicians toward the fusion genre, particularly other trumpet players. For example, Donald Byrd's shift toward commercial fusion and smooth jazz recordings of the early 1970s, while celebrated within some circles, was considered a "betrayal" by fans of hard bop. His album ''Black Byrd

''Black Byrd'' is a 1973 album by Donald Byrd and the first of his Blue Note albums to be produced by Larry Mizell, assisted by his brother, former Motown producer Fonce. In the jazz funk idiom, it is among Blue Note Records' best selling album ...

'' (1973), Blue Note's most successful album, neared #1 spot on the R&B charts despite the opposition of jazz purists. However, in 1985, the filmed concert ''One Night with Blue Note

''One Night with Blue Note'' is a 1985 feature length jazz film directed by John Jopson, John Charles Jopson.

To celebrate record executive Bruce Lundvall having relaunched the defunct Blue Note Records label in 1985 under the parent label EMI Ma ...

'' brought together thirty predominantly hard bop musicians including Art Blakey, Ron Carter

Ronald Levin Carter (born May 4, 1937) is an American jazz double bassist. His appearances on 2,221 recording sessions make him the most-recorded jazz bassist in history. He has won three Grammy awards, and is also a cellist who has recorded nu ...

, Johnny Griffin, and Freddie Hubbard.

Following fusion's decline, younger musicians started a bop revival, the best-known proponent of this being trumpeter Wynton Marsalis

Wynton Learson Marsalis (born October 18, 1961) is an American trumpeter, composer, teacher, and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. He has promoted classical and jazz music, often to young audiences. Marsalis has won nine Grammy Awar ...

. The revival was a "resurgence" by the 1990s, and by the 1990s, hard bop's revival had become so prominent that Yanow referred to it as "the foundation of modern acoustic jazz."Joe Henderson, for instance, was described by Yanow as a "national celebrity and a constant poll winner" in jazz circles after signing for Verve

Verve may refer to:

Music

* The Verve, an English rock band

* ''The Verve E.P.'', a 1992 EP by The Verve

* ''Verve'' (R. Stevie Moore album)

* Verve Records, an American jazz record label

Businesses

* Verve Coffee Roasters, an American coffee ho ...

in the 1990s, largely due to changes in marketing.

Legacy

Rosenthal observed that " e years 1955 to 1965 represent the last period in which jazz effortlessly attracted the hippiest young black musicians, the most musically advanced, those with the most solid technical skills and the strongest sense of themselves, not only as entertainers but as artists." In the same text he laments hard bop's "many detractors and few articulate defenders," describing some of the comments made by its critics as "derogatory cliches." Alternatively, Yanow suggests a slightly longer period, from 1955 to 1968, during which hard bop was "the most dominant jazz style." Although the hard bop style enjoyed its greatest popularity in the 1950s and 1960s, hard bop performers and elements of the music remain present in jazz.See also

*List of hard bop musicians

Hard bop is a subgenre of jazz that is an extension of bebop (or "bop") music. Journalists and record companies began using the term in the mid-1950s to describe a new current within jazz which incorporated influences from rhythm and blues, gospel ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hard Bop Jazz terminology Jazz genres