Gunpowder Gertie on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical

The earliest Western accounts of gunpowder appears in texts written by English philosopher

The earliest Western accounts of gunpowder appears in texts written by English philosopher

Gunpowder and gunpowder weapons were transmitted to India through the Mongol invasions of India. The Mongols were defeated by Alauddin Khalji of the

Gunpowder and gunpowder weapons were transmitted to India through the Mongol invasions of India. The Mongols were defeated by Alauddin Khalji of the  The Mughal emperor

The Mughal emperor

Cannons were introduced to Majapahit when Kublai Khan's Chinese army under the leadership of Ike Mese sought to invade Java in 1293. History of Yuan mentioned that the Mongol used cannons (Chinese: 炮—''Pào'') against Daha forces.Schlegel, Gustaaf (1902). "On the Invention and Use of Fire-Arms and Gunpowder in China, Prior to the Arrival of European". ''T'oung Pao''. 3: 1–11.Reid, Anthony (1993). ''Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680. Volume Two: Expansion and Crisis''. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Cannons were used by the

Cannons were introduced to Majapahit when Kublai Khan's Chinese army under the leadership of Ike Mese sought to invade Java in 1293. History of Yuan mentioned that the Mongol used cannons (Chinese: 炮—''Pào'') against Daha forces.Schlegel, Gustaaf (1902). "On the Invention and Use of Fire-Arms and Gunpowder in China, Prior to the Arrival of European". ''T'oung Pao''. 3: 1–11.Reid, Anthony (1993). ''Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680. Volume Two: Expansion and Crisis''. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Cannons were used by the

On the origins of gunpowder technology, historian

On the origins of gunpowder technology, historian

The development of smokeless powders, such as cordite, in the late 19th century created the need for a spark-sensitive priming charge, such as gunpowder. However, the sulfur content of traditional gunpowders caused corrosion problems with Cordite Mk I and this led to the introduction of a range of sulfur-free gunpowders, of varying grain sizes. They typically contain 70.5 parts of saltpeter and 29.5 parts of charcoal. Like black powder, they were produced in different grain sizes. In the United Kingdom, the finest grain was known as ''sulfur-free mealed powder'' (''SMP''). Coarser grains were numbered as sulfur-free gunpowder (SFG n): 'SFG 12', 'SFG 20', 'SFG 40' and 'SFG 90', for example; where the number represents the smallest BSS sieve mesh size, which retained no grains.

Sulfur's main role in gunpowder is to decrease the ignition temperature. A sample reaction for sulfur-free gunpowder would be:

: 6 KNO3 + C7H4O → 3 K2CO3 + 4 CO2 + 2 H2O + 3 N2

The development of smokeless powders, such as cordite, in the late 19th century created the need for a spark-sensitive priming charge, such as gunpowder. However, the sulfur content of traditional gunpowders caused corrosion problems with Cordite Mk I and this led to the introduction of a range of sulfur-free gunpowders, of varying grain sizes. They typically contain 70.5 parts of saltpeter and 29.5 parts of charcoal. Like black powder, they were produced in different grain sizes. In the United Kingdom, the finest grain was known as ''sulfur-free mealed powder'' (''SMP''). Coarser grains were numbered as sulfur-free gunpowder (SFG n): 'SFG 12', 'SFG 20', 'SFG 40' and 'SFG 90', for example; where the number represents the smallest BSS sieve mesh size, which retained no grains.

Sulfur's main role in gunpowder is to decrease the ignition temperature. A sample reaction for sulfur-free gunpowder would be:

: 6 KNO3 + C7H4O → 3 K2CO3 + 4 CO2 + 2 H2O + 3 N2

Modern corning first compresses the fine black powder meal into blocks with a fixed density (1.7 g/cm3). In the United States, gunpowder grains were designated F (for fine) or C (for coarse). Grain diameter decreased with a larger number of Fs and increased with a larger number of Cs, ranging from about for 7F to for 7C. Even larger grains were produced for artillery bore diameters greater than about . The standard DuPont ''Mammoth'' powder developed by Thomas Rodman and

Modern corning first compresses the fine black powder meal into blocks with a fixed density (1.7 g/cm3). In the United States, gunpowder grains were designated F (for fine) or C (for coarse). Grain diameter decreased with a larger number of Fs and increased with a larger number of Cs, ranging from about for 7F to for 7C. Even larger grains were produced for artillery bore diameters greater than about . The standard DuPont ''Mammoth'' powder developed by Thomas Rodman and

For the most powerful black powder,

For the most powerful black powder,

Études Hygiéniques de la chair de cheval comme aliment

'',

"Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys."

Armchair General. January 2005. Adapted from a talk given to the Geological Society of America on 25 March 2004. * . * . * . * * . * * . * . * * . * . * . * . * * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * . * Schmidtchen, Volker (1977a), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", ''Technikgeschichte'' 44 (2): 153–73 (153–57) * Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", ''Technikgeschichte'' 44 (3): 213–37 (226–28). * . * . * . * . * . * . * . *

Gun and Gunpowder

Oare Gunpowder Works, Kent, UK

Royal Gunpowder Mills

A digital exhibit produced by the Hagley Library that covers the founding and early history of the DuPont Company powder yards in Delaware *

Video Demonstration

of

Black Powder Recipes

* {{Use dmy dates, date=December 2019 Chinese inventions Explosives Firearm propellants Pyrotechnic compositions Rocket fuels Solid fuels

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An expl ...

. It consists of a mixture of sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

, carbon (in the form of charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

) and potassium nitrate ( saltpeter). The sulfur and carbon act as fuel

A fuel is any material that can be made to react with other substances so that it releases energy as thermal energy or to be used for work. The concept was originally applied solely to those materials capable of releasing chemical energy but ...

s while the saltpeter is an oxidizer. Gunpowder has been widely used as a propellant

A propellant (or propellent) is a mass that is expelled or expanded in such a way as to create a thrust or other motive force in accordance with Newton's third law of motion, and "propel" a vehicle, projectile, or fluid payload. In vehicles, the e ...

in firearm

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

s, artillery, rocketry, and pyrotechnics

Pyrotechnics is the science and craft of creating such things as fireworks, safety matches, oxygen candles, explosive bolts and other fasteners, parts of automotive airbags, as well as gas-pressure blasting in mining, quarrying, and demolition. ...

, including use as a blasting agent for explosive

An explosive (or explosive material) is a reactive substance that contains a great amount of potential energy that can produce an explosion if released suddenly, usually accompanied by the production of light, heat, sound, and pressure. An expl ...

s in quarrying, mining, building pipelines and road building

A road is a linear way for the conveyance of traffic that mostly has an improved surface for use by vehicles (motorized and non-motorized) and pedestrians. Unlike streets, the main function of roads is transportation.

There are many types of ...

.

Gunpowder is classified as a low explosive because of its relatively slow decomposition rate and consequently low brisance. Low explosives deflagrate

Deflagration (Lat: ''de + flagrare'', "to burn down") is subsonic combustion in which a pre-mixed flame propagates through a mixture of fuel and oxidizer. Deflagrations can only occur in pre-mixed fuels. Most fires found in daily life are diffu ...

(i.e., burn at subsonic speeds), whereas high explosives detonate, producing a supersonic shockwave

In physics, a shock wave (also spelled shockwave), or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a me ...

. Ignition of gunpowder packed behind a projectile

A projectile is an object that is propelled by the application of an external force and then moves freely under the influence of gravity and air resistance. Although any objects in motion through space are projectiles, they are commonly found in ...

generates enough pressure to force the shot from the muzzle at high speed, but usually not enough force to rupture the gun barrel. It thus makes a good propellant but is less suitable for shattering rock or fortifications with its low-yield explosive power. Nonetheless, it was widely used to fill fused artillery shells (and used in mining and civil engineering projects) until the second half of the 19th century, when the first high explosives were put into use.

Its use in weapons has declined due to smokeless powder replacing it, and it is no longer used for industrial purposes due to its relative inefficiency compared to newer alternatives such as dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and Stabilizer (chemistry), stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish people, Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germa ...

and ammonium nitrate/fuel oil.

Effect

Gunpowder is a low explosive: it does not detonate, but ratherdeflagrates

Deflagration (Lat: ''de + flagrare'', "to burn down") is subsonic combustion in which a pre-mixed flame propagates through a mixture of fuel and oxidizer. Deflagrations can only occur in pre-mixed fuels. Most fires found in daily life are diffu ...

(burns quickly). This is an advantage in a propellant device, where one does not desire a shock that would shatter the gun and potentially harm the operator; however, it is a drawback when an explosion is desired. In that case, the propellant (and most importantly, gases produced by its burning) must be confined. Since it contains its own oxidizer and additionally burns faster under pressure, its combustion is capable of bursting containers such as a shell, grenade, or improvised "pipe bomb" or "pressure cooker" casings to form shrapnel

Shrapnel may refer to:

Military

* Shrapnel shell, explosive artillery munitions, generally for anti-personnel use

* Shrapnel (fragment), a hard loose material

Popular culture

* ''Shrapnel'' (Radical Comics)

* ''Shrapnel'', a game by Adam ...

.

In quarrying, high explosives are generally preferred for shattering rock. However, because of its low brisance, gunpowder causes fewer fractures and results in more usable stone compared to other explosives, making it useful for blasting slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

, which is fragile, or monumental stone such as granite and marble. Gunpowder is well suited for blank rounds, signal flares, burst charges, and rescue-line launches. It is also used in fireworks for lifting shells, in rockets as fuel, and in certain special effect

Special effects (often abbreviated as SFX, F/X or simply FX) are illusions or visual tricks used in the theatre, film, television, video game, amusement park and simulator industries to simulate the imagined events in a story or virtual wor ...

s.

Combustion converts less than half the mass of gunpowder to gas; most of it turns into particulate matter. Some of it is ejected, wasting propelling power, fouling the air, and generally being a nuisance (giving away a soldier's position, generating fog that hinders vision, etc.). Some of it ends up as a thick layer of soot inside the barrel, where it also is a nuisance for subsequent shots, and a cause of jamming an automatic weapon. Moreover, this residue is hygroscopic, and with the addition of moisture absorbed from the air forms a corrosive substance

A corrosive substance is one that will damage or destroy other substances with which it comes into contact by means of a chemical reaction.

Etymology

The word ''corrosive'' is derived from the Latin verb ''corrodere'', which means ''to gnaw'', ...

. The soot contains potassium oxide or sodium oxide that turns into potassium hydroxide, or sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula NaOH. It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly caustic base and alkali ...

, which corrodes wrought iron or steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

gun barrels. Gunpowder arms therefore require thorough and regular cleaning to remove the residue.

History

China

The first confirmed reference to what can be considered gunpowder in China occurred in the 9th century AD during the Tang dynasty, first in a formula contained in the ''Taishang Shengzu Jindan Mijue'' (太上聖祖金丹秘訣) in 808, and then about 50 years later in a Taoist text known as the '' Zhenyuan miaodao yaolüe'' (真元妙道要略). The ''Taishang Shengzu Jindan Mijue'' mentions a formula composed of six parts sulfur to six parts saltpeter to one part birthwort herb. According to the ''Zhenyuan miaodao yaolüe'', "Some have heated together sulfur, realgar and saltpeter withhoney

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

; smoke and flames result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house where they were working burned down." Based on these Taoist texts, the invention of gunpowder by Chinese alchemists was likely an accidental byproduct from experiments seeking to create the elixir of life

The elixir of life, also known as elixir of immortality, is a potion that supposedly grants the drinker eternal life and/or eternal youth. This elixir was also said to cure all diseases. Alchemists in various ages and cultures sought the means ...

. This experimental medicine

An experimental drug is a medicinal product (a drug or vaccine) that has not yet received approval from governmental regulatory authorities for routine use in human or veterinary medicine. A medicinal product may be approved for use in one disea ...

origin is reflected in its Chinese name ''huoyao'' ( ), which means "fire medicine". Saltpeter was known to the Chinese by the mid-1st century AD and was primarily produced in the provinces of Sichuan, Shanxi

Shanxi (; ; formerly romanised as Shansi) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the North China region. The capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-lev ...

, and Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilizati ...

. There is strong evidence of the use of saltpeter and sulfur in various medicinal combinations. A Chinese alchemical text dated 492 noted saltpeter burnt with a purple flame, providing a practical and reliable means of distinguishing it from other inorganic salts, thus enabling alchemists to evaluate and compare purification techniques; the earliest Latin accounts of saltpeter purification are dated after 1200.

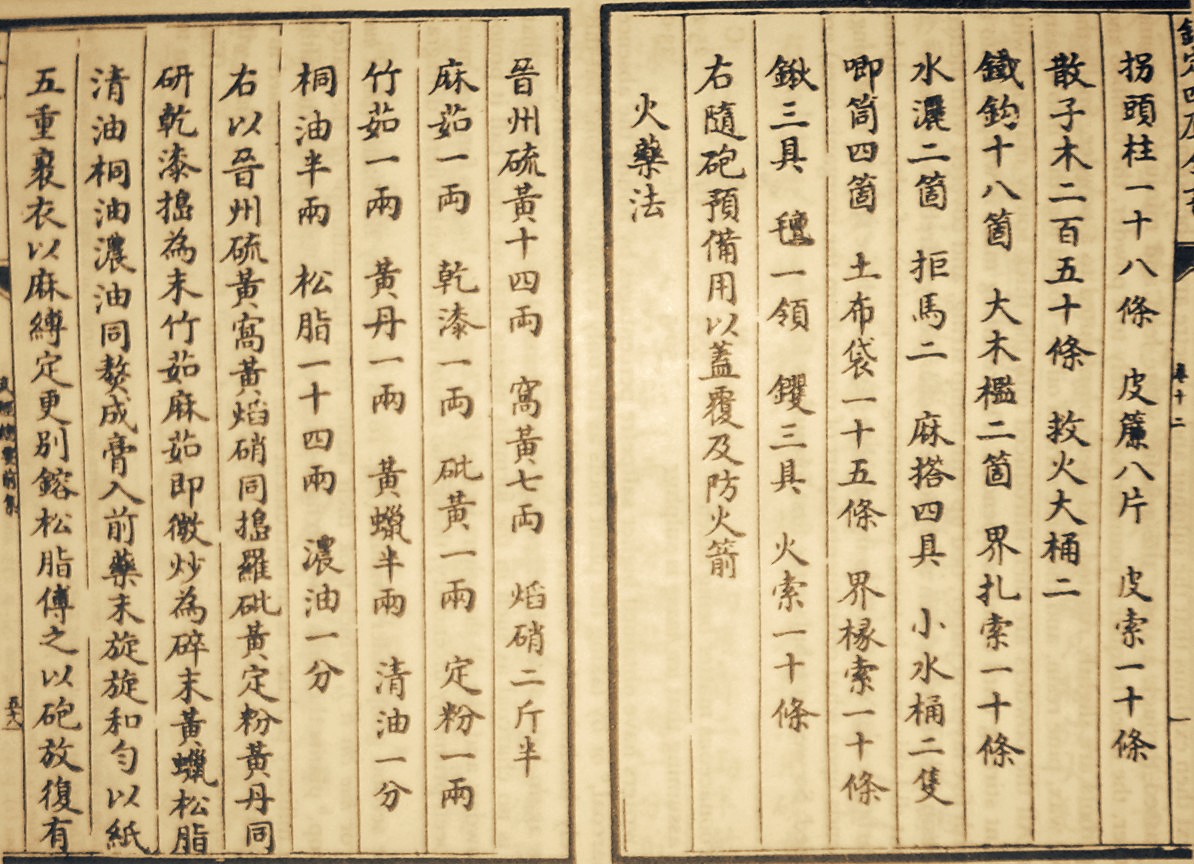

The earliest chemical formula for gunpowder appeared in the 11th century Song dynasty text, '' Wujing Zongyao'' (''Complete Essentials from the Military Classics''), written by Zeng Gongliang

Zeng Gongliang (曾公亮, Tseng Kung-Liang; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: ''Chan Kong-liāng'') (998–1078) was a Chinese scholar of the Song Dynasty, who helped write the ''Wujing Zongyao

The ''Wujing Zongyao'' (), sometimes rendered in English as the '' ...

between 1040 and 1044. The ''Wujing Zongyao'' provides encyclopedia references to a variety of mixtures that included petrochemicals—as well as garlic and honey. A slow match for flame-throwing mechanisms using the siphon principle and for fireworks and rockets is mentioned. The mixture formulas in this book contain at most 50 % saltpeter; not enough to create an explosion, they produce an incendiary instead. The ''Essentials'' was written by a Song dynasty court bureaucrat and there is little evidence that it had any immediate impact on warfare; there is no mention of its use in the chronicles of the wars against the Tanguts

The Tangut people ( Tangut: , ''mjɨ nja̱'' or , ''mji dzjwo''; ; ; mn, Тангуд) were a Tibeto-Burman tribal union that founded and inhabited the Western Xia dynasty. The group initially lived under Tuyuhun authority, but later submitted t ...

in the 11th century, and China was otherwise mostly at peace during this century. However, it had already been used for fire arrows since at least the 10th century. Its first recorded military application dates its use to the year 904 in the form of incendiary projectiles. In the following centuries various gunpowder weapons such as bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the Exothermic process, exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-t ...

s, fire lances, and the gun appeared in China. Explosive weapons such as bombs have been discovered in a shipwreck off the shore of Japan dated from 1281, during the Mongol invasions of Japan.

By 1083 the Song court was producing hundreds of thousands of fire arrows for their garrisons. Bombs and the first proto-guns, known as "fire lances", became prominent during the 12th century and were used by the Song during the Jin-Song Wars. Fire lances were first recorded to have been used at the Siege of De'an in 1132 by Song forces against the Jin. In the early 13th century the Jin used iron-casing bombs. Projectiles were added to fire lances, and re-usable fire lance barrels were developed, first out of hardened paper, and then metal. By 1257 some fire lances were firing wads of bullets. In the late 13th-century metal fire lances became 'eruptors', proto-cannons firing co-viative projectiles (mixed with the propellant, rather than seated over it with a wad), and by 1287 at the latest, had become true guns, the hand cannon.

Middle East

According to Iqtidar Alam Khan, it was invading Mongols who introduced gunpowder to the Islamic world. TheMuslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s acquired knowledge of gunpowder some time between 1240 and 1280, by which point the Syrian Hasan al-Rammah had written recipes, instructions for the purification of saltpeter, and descriptions of gunpowder incendiaries. It is implied by al-Rammah's usage of "terms that suggested he derived his knowledge from Chinese sources" and his references to saltpeter as "Chinese snow" ( ar, ثلج الصين '), fireworks as "Chinese flowers", and rockets as "Chinese arrows" that knowledge of gunpowder arrived from China. However, because al-Rammah attributes his material to "his father and forefathers", al-Hassan argues that gunpowder became prevalent in Syria and Egypt by "the end of the twelfth century or the beginning of the thirteenth". In Persia saltpeter was known as "Chinese salt" ( fa, نمک چینی) ''namak-i chīnī'') or "salt from Chinese salt marshes" ( ').

Hasan al-Rammah included 107 gunpowder recipes in his text ''al-Furusiyyah wa al-Manasib al-Harbiyya'' (''The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices''), 22 of which are for rockets. If one takes the median of 17 of these 22 compositions for rockets (75% nitrates, 9.06% sulfur, and 15.94% charcoal), it is nearly identical to the modern reported ideal recipe of 75% potassium nitrate, 10% sulfur, and 15% charcoal. The text also mentions fuses, incendiary bombs, naphtha pots, fire lances, and an illustration and description of the earliest torpedo. The torpedo was called the "egg which moves itself and burns". Two iron sheets were fastened together and tightened using felt. The flattened pear shaped vessel was filled with gunpowder, metal filings, "good mixtures", two rods, and a large rocket for propulsion. Judging by the illustration, it was evidently supposed to glide across the water. Fire lances were used in battles between the Muslims and Mongols in 1299 and 1303.

Al-Hassan claims that in the Battle of Ain Jalut of 1260, the Mamluks

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') i ...

used against the Mongols, in "the first cannon in history", formula with near-identical ideal composition ratios for explosive gunpowder. Other historians urge caution regarding claims of Islamic firearms use in the 1204–1324 period as late medieval Arabic texts used the same word for gunpowder, ''naft'', that they used for an earlier incendiary, naphtha.

The earliest surviving documentary evidence for cannons in the Islamic world is from an Arabic manuscript dated to the early 14th century. The author's name is uncertain but may have been Shams al-Din Muhammad, who died in 1350. Dating from around 1320-1350, the illustrations show gunpowder weapons such as gunpowder arrows, bombs, fire tubes, and fire lances or proto-guns. The manuscript describes a type of gunpowder weapon called a ''midfa'' which uses gunpowder to shoot projectiles out of a tube at the end of a stock. Some consider this to be a cannon while others do not. The problem with identifying cannons in early 14th century Arabic texts is the term ''midfa'', which appears from 1342 to 1352 but cannot be proven to be true hand-guns or bombards. Contemporary accounts of a metal-barrel cannon in the Islamic world do not occur until 1365. Needham believes that in its original form the term ''midfa'' refers to the tube or cylinder of a naphtha projector (flamethrower

A flamethrower is a ranged incendiary device designed to project a controllable jet of fire. First deployed by the Byzantine Empire in the 7th century AD, flamethrowers saw use in modern times during World War I, and more widely in World ...

), then after the invention of gunpowder it meant the tube of fire lances, and eventually it applied to the cylinder of hand-gun and cannon.

According to Paul E. J. Hammer, the Mamluks

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') i ...

certainly used cannons by 1342. According to J. Lavin, cannons were used by Moors at the siege of Algeciras in 1343. A metal cannon firing an iron ball was described by Shihab al-Din Abu al-Abbas al-Qalqashandi between 1365 and 1376.

The musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

appeared in the Ottoman Empire by 1465. In 1598, Chinese writer Zhao Shizhen described Turkish muskets as being superior to European muskets. The Chinese military book '' Wu Pei Chih'' (1621) later described Turkish muskets that used a rack-and-pinion mechanism, which was not known to have been used in European or Chinese firearms at the time.

The state-controlled manufacture of gunpowder by the Ottoman Empire through early supply chain

In commerce, a supply chain is a network of facilities that procure raw materials, transform them into intermediate goods and then final products to customers through a distribution system. It refers to the network of organizations, people, acti ...

s to obtain nitre, sulfur and high-quality charcoal from oaks in Anatolia contributed significantly to its expansion between the 15th and 18th century. It was not until later in the 19th century when the syndicalist production of Turkish gunpowder was greatly reduced, which coincided with the decline of its military might.

Europe

The earliest Western accounts of gunpowder appears in texts written by English philosopher

The earliest Western accounts of gunpowder appears in texts written by English philosopher Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empiri ...

in 1267 called '' Opus Majus'' and ''Opus Tertium''. The oldest written recipes in continental Europe were recorded under the name Marcus Graecus or Mark the Greek between 1280 and 1300 in the ''Liber Ignium

The ''Liber Ignium ad Comburendos Hostes'' (translated as ''On the Use of Fire to Conflagrate the Enemy'', or ''Book of Fires for the Burning of Enemies'', and abbreviated as ''Book of Fires'') is a medieval collection of recipes for incendiary wea ...

'', or ''Book of Fires''.

Some sources mention possible gunpowder weapons being deployed by the Mongols against European forces at the Battle of Mohi in 1241. Professor Kenneth Warren Chase credits the Mongols for introducing into Europe gunpowder and its associated weaponry. However, there is no clear route of transmission, and while the Mongols are often pointed to as the likeliest vector, Timothy May points out that "there is no concrete evidence that the Mongols used gunpowder weapons on a regular basis outside of China." However, Timothy May also points out "However... the Mongols used the gunpowder weapon in their wars against the Jin, the Song and in their invasions of Japan."

Records show that, in England, gunpowder was being made in 1346 at the Tower of London; a powder house

A powder tower (german: Pulverturm), occasionally also powder house (''Pulverhaus''), was a building used by the military or by mining companies, frequently a tower, to store gunpowder or, later, explosives. They were common until the 20th centur ...

existed at the Tower in 1461; and in 1515 three King's gunpowder makers worked there. Gunpowder was also being made or stored at other royal castles, such as Portchester. The English Civil War (1642–1645) led to an expansion of the gunpowder industry, with the repeal of the Royal Patent in August 1641.

In late 14th century Europe, gunpowder was improved by ''corning'', the practice of drying it into small clumps to improve combustion and consistency. During this time, European manufacturers also began regularly purifying saltpeter, using wood ashes containing potassium carbonate to precipitate calcium from their dung liquor, and using ox blood, alum

An alum () is a type of chemical compound, usually a hydrated double salt, double sulfate salt (chemistry), salt of aluminium with the general chemical formula, formula , where is a valence (chemistry), monovalent cation such as potassium or a ...

, and slices of turnip to clarify the solution.

During the Renaissance, two European schools of pyrotechnic thought emerged, one in Italy and the other at Nuremberg, Germany. In Italy, Vannoccio Biringuccio, born in 1480, was a member of the guild ''Fraternita di Santa Barbara'' but broke with the tradition of secrecy by setting down everything he knew in a book titled '' De la pirotechnia'', written in vernacular. It was published posthumously in 1540, with 9 editions over 138 years, and also reprinted by MIT Press in 1966.

By the mid-17th century fireworks were used for entertainment on an unprecedented scale in Europe, being popular even at resorts and public gardens. With the publication of ''Deutliche Anweisung zur Feuerwerkerey'' (1748), methods for creating fireworks were sufficiently well-known and well-described that "Firework making has become an exact science." In 1774 Louis XVI ascended to the throne of France at age 20. After he discovered that France was not self-sufficient in gunpowder, a Gunpowder Administration was established; to head it, the lawyer Antoine Lavoisier was appointed. Although from a bourgeois family, after his degree in law Lavoisier became wealthy from a company set up to collect taxes for the Crown; this allowed him to pursue experimental natural science as a hobby.

Without access to cheap saltpeter (controlled by the British), for hundreds of years France had relied on saltpetremen with royal warrants, the ''droit de fouille'' or "right to dig", to seize nitrous-containing soil and demolish walls of barnyards, without compensation to the owners. This caused farmers, the wealthy, or entire villages to bribe the petermen and the associated bureaucracy to leave their buildings alone and the saltpeter uncollected. Lavoisier instituted a crash program to increase saltpeter production, revised (and later eliminated) the ''droit de fouille'', researched best refining and powder manufacturing methods, instituted management and record-keeping, and established pricing that encouraged private investment in works. Although saltpeter from new Prussian-style putrefaction works had not been produced yet (the process taking about 18 months), in only a year France had gunpowder to export. A chief beneficiary of this surplus was the American Revolution. By careful testing and adjusting the proportions and grinding time, powder from mills such as at Essonne outside Paris became the best in the world by 1788, and inexpensive.

Two British physicists, Andrew Noble and Frederick Abel

Sir Frederick Augustus Abel, 1st Baronet (17 July 18276 September 1902) was an English chemist who was recognised as the leading British authority on explosives. He is best known for the invention of cordite as a replacement for gunpowder in f ...

, worked to improve the properties of gunpowder during the late 19th century. This formed the basis for the Noble-Abel gas equation for internal ballistics.

The introduction of smokeless powder in the late 19th century led to a contraction of the gunpowder industry. After the end of World War I, the majority of the British gunpowder manufacturers merged into a single company, "Explosives Trades limited"; and a number of sites were closed down, including those in Ireland. This company became Nobel Industries Limited; and in 1926 became a founding member of Imperial Chemical Industries

Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was a British chemical company. It was, for much of its history, the largest manufacturer in Britain.

It was formed by the merger of four leading British chemical companies in 1926.

Its headquarters were at M ...

. The Home Office removed gunpowder from its list of ''Permitted Explosives''; and shortly afterwards, on 31 December 1931, the former Curtis & Harvey's Glynneath gunpowder factory at Pontneddfechan

Pontneddfechan, also known as Pontneathvaughan (pronounced ) ("bridge over the Little Neath" in Welsh) is the southernmost village in the county of Brecknockshire, Wales, within the Vale of Neath, in the community of Ystradfellte and in the prin ...

, in Wales, closed down, and it was demolished by fire in 1932. The last remaining gunpowder mill at the Royal Gunpowder Factory, Waltham Abbey

The Royal Gunpowder Mills are a former industrial site in Waltham Abbey, England.

It was one of three Royal Gunpowder Mills in the United Kingdom (the others being at Ballincollig and Faversham). Waltham Abbey is the only site to have survi ...

was damaged by a German parachute mine in 1941 and it never reopened. This was followed by the closure of the gunpowder section at the Royal Ordnance Factory

Royal Ordnance Factories (ROFs) was the collective name of the UK government's munitions factories during and after the Second World War. Until privatisation, in 1987, they were the responsibility of the Ministry of Supply, and later the Ministr ...

, ROF Chorley, the section was closed and demolished at the end of World War II; and ICI Nobel's Roslin gunpowder factory, which closed in 1954. This left ICI Nobel's Ardeer site in Scotland, which included a gunpowder factory, as the only factory in Great Britain producing gunpowder. The gunpowder area of the Ardeer site closed in October 1976.

India

Gunpowder and gunpowder weapons were transmitted to India through the Mongol invasions of India. The Mongols were defeated by Alauddin Khalji of the

Gunpowder and gunpowder weapons were transmitted to India through the Mongol invasions of India. The Mongols were defeated by Alauddin Khalji of the Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate was an Islamic empire based in Delhi that stretched over large parts of the Indian subcontinent for 320 years (1206–1526).

, and some of the Mongol soldiers remained in northern India after their conversion to Islam. It was written in the ''Tarikh-i Firishta'' (1606–1607) that Nasiruddin Mahmud the ruler of the Delhi Sultanate presented the envoy of the Mongol ruler Hulegu Khan

Hulagu Khan, also known as Hülegü or Hulegu ( mn, Khalkha Mongolian, Хүлэгү/Chakhar Mongolian, , lit=Surplus, translit=Hu’legu’/Qülegü; chg, ; Arabic: fa, هولاکو خان, ''Holâku Khân;'' ; 8 February 1265), was a Mon ...

with a dazzling pyrotechnics display upon his arrival in Delhi in 1258. Nasiruddin Mahmud tried to express his strength as a ruler and tried to ward off any Mongol attempt similar to the Siege of Baghdad (1258). Firearms known as ''top-o-tufak'' also existed in many Muslim kingdoms in India by as early as 1366. From then on the employment of gunpowder warfare in India was prevalent, with events such as the "Siege of Belgaum

Belgaum (ISO 15919, ISO: ''Bēḷagāma''; also Belgaon and officially known as Belagavi) is a city in the Indian state of Karnataka located in its northern part along the Western Ghats. It is the administrative headquarters of the eponymous ...

" in 1473 by Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

Muhammad Shah Bahmani.

The shipwrecked Ottoman Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Seydi Ali Reis is known to have introduced the earliest type of matchlock weapons, which the Ottomans used against the Portuguese during the Siege of Diu (1531)

The siege of Diu occurred when a combined Ottoman-Gujarati force defeated a Portuguese attempt to capture the city of Diu in 1531. The victory was partly the result of Ottoman firepower over the Portuguese besiegers deployed by Mustafa Ba ...

. After that, a diverse variety of firearms, large guns in particular, became visible in Tanjore, Dacca

Dhaka ( or ; bn, ঢাকা, Ḍhākā, ), formerly known as Dacca, is the capital and largest city of Bangladesh, as well as the world's largest Bengali-speaking city. It is the eighth largest and sixth most densely populated city i ...

, Bijapur

Bijapur, officially known as Vijayapura, is the district headquarters of Bijapur district of the Karnataka state of India. It is also the headquarters for Bijapur Taluk. Bijapur city is well known for its historical monuments of architectural ...

, and Murshidabad. Guns made of bronze were recovered from Calicut (1504)- the former capital of the Zamorins

The Mughal emperor

The Mughal emperor Akbar

Abu'l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar (25 October 1542 – 27 October 1605), popularly known as Akbar the Great ( fa, ), and also as Akbar I (), was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Hum ...

mass-produced matchlocks for the Mughal Army. Akbar is personally known to have shot a leading Rajput commander during the Siege of Chittorgarh. The Mughals began to use bamboo rockets (mainly for signalling) and employ sappers: special units that undermined heavy stone fortifications to plant gunpowder charges.

The Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan

Shihab-ud-Din Muhammad Khurram (5 January 1592 – 22 January 1666), better known by his regnal name Shah Jahan I (; ), was the fifth emperor of the Mughal Empire, reigning from January 1628 until July 1658. Under his emperorship, the Mugha ...

is known to have introduced much more advanced matchlocks, their designs were a combination of Ottoman and Mughal designs. Shah Jahan also countered the British and other Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common genetic ancestry, common language, or both. Pan and Pfeil (2004) ...

in his province of Gujarāt

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the ninth- ...

, which supplied Europe saltpeter for use in gunpowder warfare during the 17th century."India." Encyclopædia Britannica 2008 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008. Bengal and Mālwa participated in saltpeter production. The Dutch, French, Portuguese, and English used Chhapra as a center of saltpeter refining.

Ever since the founding of the Sultanate of Mysore

The Kingdom of Mysore was a realm in southern India, traditionally believed to have been founded in 1399 in the vicinity of the modern city of Mysore. From 1799 until 1950, it was a princely state, until 1947 in a subsidiary alliance with Pres ...

by Hyder Ali, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

military officers were employed to train the Mysore Army. Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan were the first to introduce modern cannons and musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

s, their army was also the first in India to have official uniforms. During the Second Anglo-Mysore War Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan unleashed the Mysorean rockets at their British opponents effectively defeating them on various occasions. The Mysorean rockets inspired the development of the Congreve rocket, which the British widely used during the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812."rocket and missile system." Encyclopædia Britannica 2008 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

Southeast Asia

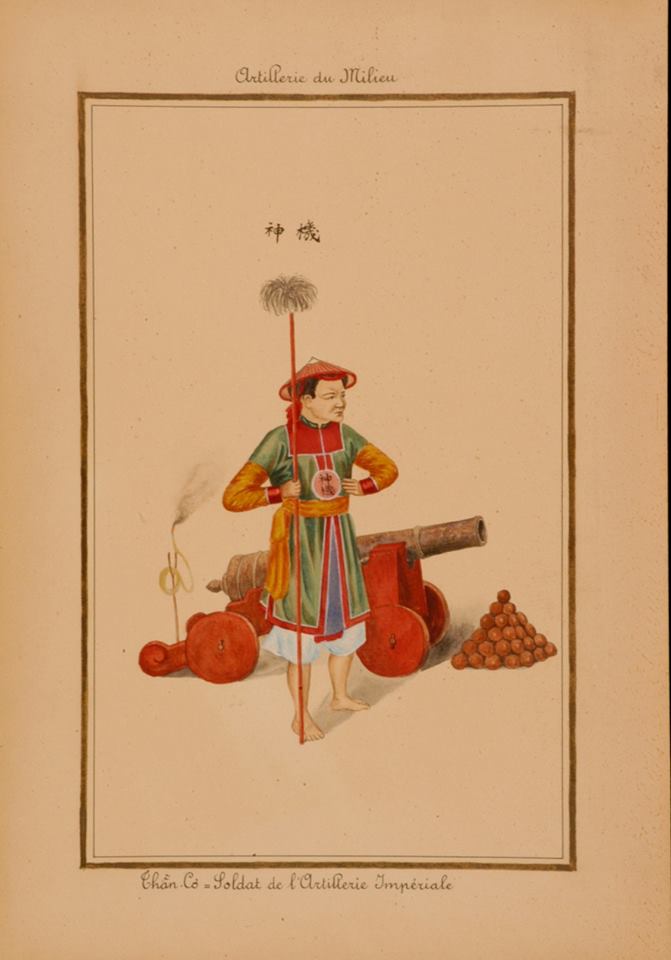

Cannons were introduced to Majapahit when Kublai Khan's Chinese army under the leadership of Ike Mese sought to invade Java in 1293. History of Yuan mentioned that the Mongol used cannons (Chinese: 炮—''Pào'') against Daha forces.Schlegel, Gustaaf (1902). "On the Invention and Use of Fire-Arms and Gunpowder in China, Prior to the Arrival of European". ''T'oung Pao''. 3: 1–11.Reid, Anthony (1993). ''Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680. Volume Two: Expansion and Crisis''. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Cannons were used by the

Cannons were introduced to Majapahit when Kublai Khan's Chinese army under the leadership of Ike Mese sought to invade Java in 1293. History of Yuan mentioned that the Mongol used cannons (Chinese: 炮—''Pào'') against Daha forces.Schlegel, Gustaaf (1902). "On the Invention and Use of Fire-Arms and Gunpowder in China, Prior to the Arrival of European". ''T'oung Pao''. 3: 1–11.Reid, Anthony (1993). ''Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680. Volume Two: Expansion and Crisis''. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Cannons were used by the Ayutthaya Kingdom

The Ayutthaya Kingdom (; th, อยุธยา, , IAST: or , ) was a Siamese kingdom that existed in Southeast Asia from 1351 to 1767, centered around the city of Ayutthaya, in Siam, or present-day Thailand. The Ayutthaya Kingdom is conside ...

in 1352 during its invasion of the Khmer Empire. Within a decade large quantities of gunpowder could be found in the Khmer Empire. By the end of the century firearms were also used by the Trần dynasty.

Even though the knowledge of making gunpowder-based weapon has been known after the failed Mongol invasion of Java, and the predecessor of firearms, the pole gun ( bedil tombak), was recorded as being used by Java in 1413, the knowledge of making "true" firearms came much later, after the middle of the 15th century. It was brought by the Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

ic nations of West Asia, most probably the Arabs. The precise year of introduction is unknown, but it may be safely concluded to be no earlier than 1460. Before the arrival of the Portuguese in Southeast Asia, the natives already possessed primitive firearms, the Java arquebus. Portuguese influence to local weaponry after the capture of Malacca (1511) resulted in a new type of hybrid tradition matchlock firearm, the istinggar.Andaya, L. Y. 1999. Interaction with the outside world and adaptation in Southeast Asian society 1500–1800. In ''The Cambridge history of southeast Asia''. ed. Nicholas Tarling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 345–401.

Portuguese and Spanish invaders were unpleasantly surprised and even outgunned on occasion. Circa 1540, the Javanese, always alert for new weapons found the newly arrived Portuguese weaponry superior to that of the locally made variants. Majapahit

Majapahit ( jv, ꦩꦗꦥꦲꦶꦠ꧀; ), also known as Wilwatikta ( jv, ꦮꦶꦭ꧀ꦮꦠꦶꦏ꧀ꦠ; ), was a Javanese people, Javanese Hinduism, Hindu-Buddhism, Buddhist thalassocracy, thalassocratic empire in Southeast Asia that was ba ...

-era cetbang cannons were further improved and used in the Demak Sultanate period during the Demak invasion of Portuguese Malacca. During this period, the iron for manufacturing Javanese cannons was imported from Khorasan

Khorasan may refer to:

* Greater Khorasan, a historical region which lies mostly in modern-day northern/northwestern Afghanistan, northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan

* Khorasan Province, a pre-2004 province of Ira ...

in northern Persia. The material was known by Javanese as ''wesi kurasani'' (Khorasan iron). When the Portuguese came to the archipelago, they referred to it as ''berço'', which was also used to refer to any breech-loading swivel gun, while the Spaniards

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance peoples, Romance ethnic group native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of National and regional identity in Spain, national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex Hist ...

call it ''verso''. By the early 16th century, the Javanese already locally-producing large guns, some of them still survived until the present day and dubbed as "sacred cannon" or "holy cannon". These cannons varied between 180- to 260-pounders, weighing anywhere between 3–8 tons, length of them between 3–6 m.

Saltpeter harvesting was recorded by Dutch and German travelers as being common in even the smallest villages and was collected from the decomposition process of large dung hills specifically piled for the purpose. The Dutch punishment for possession of non-permitted gunpowder appears to have been amputation. Ownership and manufacture of gunpowder was later prohibited by the colonial Dutch occupiers.Dipanegara, P.B.R. Carey, ''Babad Dipanagara: an account of the outbreak of the Java war, 1825–30 : the Surakarta court version of the Babad Dipanagara with translations into English and Indonesian'' volume 9: Council of the M.B.R.A.S. by Art Printing Works: 1981. According to colonel McKenzie quoted in Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles', '' The History of Java'' (1817), the purest sulfur was supplied from a crater from a mountain near the straits of Bali

Bali () is a province of Indonesia and the westernmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. East of Java and west of Lombok, the province includes the island of Bali and a few smaller neighbouring islands, notably Nusa Penida, Nusa Lembongan, and Nu ...

.

Historiography

On the origins of gunpowder technology, historian

On the origins of gunpowder technology, historian Tonio Andrade

Tonio Adam Andrade (born 1968) is an historian of East Asian history and the history of East Asian trading networks.

Bibliography

* ''Commerce, Culture, and Conflict: Taiwan Under European Rule, 1624–1662''. Yale University Press, 2000.

* ''H ...

remarked, "Scholars today overwhelmingly concur that the gun was invented in China." Gunpowder and the gun are widely believed by historians to have originated from China due to the large body of evidence that documents the evolution of gunpowder from a medicine to an incendiary and explosive, and the evolution of the gun from the fire lance to a metal gun, whereas similar records do not exist elsewhere. As Andrade explains, the large amount of variation in gunpowder recipes in China relative to Europe is "evidence of experimentation in China, where gunpowder was at first used as an incendiary and only later became an explosive and a propellant... in contrast, formulas in Europe diverged only very slightly from the ideal proportions for use as an explosive and a propellant, suggesting that gunpowder was introduced as a mature technology."

However, the history of gunpowder is not without controversy. A major problem confronting the study of early gunpowder history is ready access to sources close to the events described. Often the first records potentially describing use of gunpowder in warfare were written several centuries after the fact, and may well have been colored by the contemporary experiences of the chronicler. Translation difficulties have led to errors or loose interpretations bordering on artistic licence. Ambiguous language can make it difficult to distinguish gunpowder weapons from similar technologies that do not rely on gunpowder. A commonly cited example is a report of the Battle of Mohi in Eastern Europe that mentions a "long lance" sending forth "evil-smelling vapors and smoke", which has been variously interpreted by different historians as the "first-gas attack upon European soil" using gunpowder, "the first use of cannon in Europe", or merely a "toxic gas" with no evidence of gunpowder. It is difficult to accurately translate original Chinese alchemical texts, which tend to explain phenomena through metaphor, into modern scientific language with rigidly defined terminology in English. Early texts potentially mentioning gunpowder are sometimes marked by a linguistic process where semantic change occurred. For instance, the Arabic word ''naft'' transitioned from denoting naphtha to denoting gunpowder, and the Chinese word ''pào'' changed in meaning from trebuchet to a cannon. This has led to arguments on the exact origins of gunpowder based on etymological foundations. Science and technology historian Bert S. Hall makes the observation that, "It goes without saying, however, that historians bent on special pleading, or simply with axes of their own to grind, can find rich material in these terminological thickets."

Another major area of contention in modern studies of the history of gunpowder is regarding the transmission of gunpowder. While the literary and archaeological evidence supports a Chinese origin for gunpowder and guns, the manner in which gunpowder technology was transferred from China to the West is still under debate. It is unknown why the rapid spread of gunpowder technology across Eurasia took place over several decades whereas other technologies such as paper, the compass, and printing did not reach Europe until centuries after they were invented in China.

Components

Gunpowder is a granular mixture of: * anitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion

A polyatomic ion, also known as a molecular ion, is a covalent bonded set of two or more atoms, or of a metal complex, that can be considered to behave as a single unit and that has a net charge that is not zer ...

, typically potassium nitrate (KNO3), which supplies oxygen for the reaction;

* charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

, which provides carbon and other fuel for the reaction, simplified as carbon (C);

* sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

(S), which, while also serving as a fuel, lowers the temperature required to ignite the mixture, thereby increasing the rate of combustion.

Potassium nitrate is the most important ingredient in terms of both bulk and function because the combustion process releases oxygen from the potassium nitrate, promoting the rapid burning of the other ingredients. To reduce the likelihood of accidental ignition by static electricity

Static electricity is an imbalance of electric charges within or on the surface of a material or between materials. The charge remains until it is able to move away by means of an electric current or electrical discharge. Static electricity is na ...

, the granules of modern gunpowder are typically coated with graphite, which prevents the build-up of electrostatic charge.

Charcoal does not consist of pure carbon; rather, it consists of partially pyrolyzed

The pyrolysis (or devolatilization) process is the thermal decomposition of materials at elevated temperatures, often in an inert atmosphere. It involves a change of chemical composition. The word is coined from the Greek-derived elements ''pyr ...

cellulose, in which the wood is not completely decomposed. Carbon differs from ordinary charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

. Whereas charcoal's autoignition temperature is relatively low, carbon's is much greater. Thus, a gunpowder composition containing pure carbon would burn similarly to a match head, at best.

The current standard composition for the gunpowder manufactured by pyrotechnicians was adopted as long ago as 1780. Proportions by weight are 75% potassium nitrate (known as saltpeter or saltpetre), 15% softwood charcoal, and 10% sulfur. These ratios have varied over the centuries and by country, and can be altered somewhat depending on the purpose of the powder. For instance, power grades of black powder, unsuitable for use in firearms but adequate for blasting rock in quarrying operations, are called blasting powder rather than gunpowder with standard proportions of 70% nitrate, 14% charcoal, and 16% sulfur; blasting powder may be made with the cheaper sodium nitrate

Sodium nitrate is the chemical compound with the formula . This alkali metal nitrate salt is also known as Chile saltpeter (large deposits of which were historically mined in Chile) to distinguish it from ordinary saltpeter, potassium nitrate. T ...

substituted for potassium nitrate and proportions may be as low as 40% nitrate, 30% charcoal, and 30% sulfur. In 1857, Lammot du Pont solved the main problem of using cheaper sodium nitrate formulations when he patented DuPont "B" blasting powder. After manufacturing grains from press-cake in the usual way, his process tumbled the powder with graphite dust for 12 hours. This formed a graphite coating on each grain that reduced its ability to absorb moisture.

Neither the use of graphite nor sodium nitrate was new. Glossing gunpowder corns with graphite was already an accepted technique in 1839, and sodium nitrate-based blasting powder had been made in Peru for many years using the sodium nitrate mined at Tarapacá

San Lorenzo de Tarapacá, also known simply as Tarapacá, is a town in the region of the same name in Chile.

History

The town has likely been inhabited since the 12th century, when it formed part of the Inca trail. When Spanish explorer Diego d ...

(now in Chile). Also, in 1846, two plants were built in south-west England to make blasting powder using this sodium nitrate. The idea may well have been brought from Peru by Cornish miners returning home after completing their contracts. Another suggestion is that it was William Lobb, the plant collector, who recognised the possibilities of sodium nitrate during his travels in South America. Lammot du Pont would have known about the use of graphite and probably also knew about the plants in south-west England. In his patent he was careful to state that his claim was for the combination of graphite with sodium nitrate-based powder, rather than for either of the two individual technologies.

French war powder in 1879 used the ratio 75% saltpeter, 12.5% charcoal, 12.5% sulfur. English war powder in 1879 used the ratio 75% saltpeter, 15% charcoal, 10% sulfur. The British Congreve rockets used 62.4% saltpeter, 23.2% charcoal and 14.4% sulfur, but the British Mark VII gunpowder was changed to 65% saltpeter, 20% charcoal and 15% sulfur. The explanation for the wide variety in formulation relates to usage. Powder used for rocketry can use a slower burn rate since it accelerates the projectile for a much longer time—whereas powders for weapons such as flintlocks, cap-locks, or matchlocks need a higher burn rate to accelerate the projectile in a much shorter distance. Cannons usually used lower burn-rate powders, because most would burst with higher burn-rate powders.

Other compositions

Besides black powder, there are other historically important types of gunpowder. "Brown gunpowder" is cited as composed of 79% nitre, 3% sulfur, and 18% charcoal per 100 of dry powder, with about 2% moisture. Prismatic Brown Powder is a large-grained product theRottweil

Rottweil (; Alemannic: ''Rautweil'') is a town in southwest Germany in the state of Baden-Württemberg. Rottweil was a free imperial city for nearly 600 years.

Located between the Black Forest and the Swabian Alps, Rottweil has nearly 25,000 in ...

Company introduced in 1884 in Germany, which was adopted by the British Royal Navy shortly thereafter. The French navy adopted a fine, 3.1 millimeter, not prismatic grained product called ''Slow Burning Cocoa'' (SBC) or "cocoa powder". These brown powders reduced burning rate even further by using as little as 2 percent sulfur and using charcoal made from rye

Rye (''Secale cereale'') is a grass grown extensively as a grain, a cover crop and a forage crop. It is a member of the wheat tribe (Triticeae) and is closely related to both wheat (''Triticum'') and barley (genus ''Hordeum''). Rye grain is u ...

straw that had not been completely charred, hence the brown color.

Lesmok powder was a product developed by DuPont in 1911, one of several semi-smokeless products in the industry containing a mixture of black and nitrocellulose powder. It was sold to Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

and others primarily for .22 and .32 small calibers. Its advantage was that it was believed at the time to be less corrosive than smokeless powders then in use. It was not understood in the U.S. until the 1920s that the actual source of corrosion was the potassium chloride residue from potassium chlorate sensitized primers. The bulkier black powder fouling better disperses primer residue. Failure to mitigate primer corrosion by dispersion caused the false impression that nitrocellulose-based powder caused corrosion. Lesmok had some of the bulk of black powder for dispersing primer residue, but somewhat less total bulk than straight black powder, thus requiring less frequent bore cleaning. It was last sold by Winchester in 1947.

Sulfur-free powders

The development of smokeless powders, such as cordite, in the late 19th century created the need for a spark-sensitive priming charge, such as gunpowder. However, the sulfur content of traditional gunpowders caused corrosion problems with Cordite Mk I and this led to the introduction of a range of sulfur-free gunpowders, of varying grain sizes. They typically contain 70.5 parts of saltpeter and 29.5 parts of charcoal. Like black powder, they were produced in different grain sizes. In the United Kingdom, the finest grain was known as ''sulfur-free mealed powder'' (''SMP''). Coarser grains were numbered as sulfur-free gunpowder (SFG n): 'SFG 12', 'SFG 20', 'SFG 40' and 'SFG 90', for example; where the number represents the smallest BSS sieve mesh size, which retained no grains.

Sulfur's main role in gunpowder is to decrease the ignition temperature. A sample reaction for sulfur-free gunpowder would be:

: 6 KNO3 + C7H4O → 3 K2CO3 + 4 CO2 + 2 H2O + 3 N2

The development of smokeless powders, such as cordite, in the late 19th century created the need for a spark-sensitive priming charge, such as gunpowder. However, the sulfur content of traditional gunpowders caused corrosion problems with Cordite Mk I and this led to the introduction of a range of sulfur-free gunpowders, of varying grain sizes. They typically contain 70.5 parts of saltpeter and 29.5 parts of charcoal. Like black powder, they were produced in different grain sizes. In the United Kingdom, the finest grain was known as ''sulfur-free mealed powder'' (''SMP''). Coarser grains were numbered as sulfur-free gunpowder (SFG n): 'SFG 12', 'SFG 20', 'SFG 40' and 'SFG 90', for example; where the number represents the smallest BSS sieve mesh size, which retained no grains.

Sulfur's main role in gunpowder is to decrease the ignition temperature. A sample reaction for sulfur-free gunpowder would be:

: 6 KNO3 + C7H4O → 3 K2CO3 + 4 CO2 + 2 H2O + 3 N2

Smokeless powders

The term ''black powder'' was coined in the late 19th century, primarily in the United States, to distinguish prior gunpowder formulations from the new smokeless powders and semi-smokeless powders. Semi-smokeless powders featured bulk volume properties that approximated black powder, but had significantly reduced amounts of smoke and combustion products. Smokeless powder has different burning properties (pressure vs. time) and can generate higher pressures and work per gram. This can rupture older weapons designed for black powder. Smokeless powders ranged in color from brownish tan to yellow to white. Most of the bulk semi-smokeless powders ceased to be manufactured in the 1920s.Granularity

Serpentine

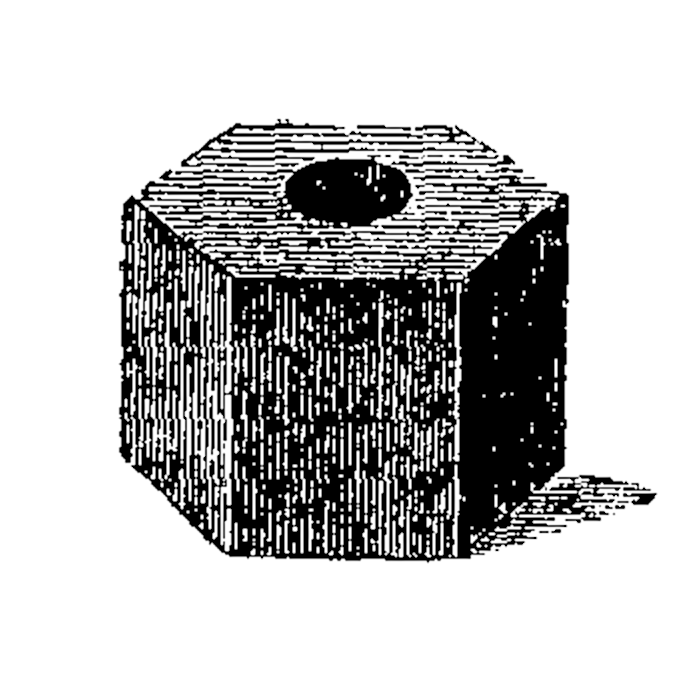

The original dry-compounded powder used in 15th-century Europe was known as "Serpentine", either a reference to Satan or to a common artillery piece that used it. The ingredients were ground together with a mortar and pestle, perhaps for 24 hours, resulting in a fine flour. Vibration during transportation could cause the components to separate again, requiring remixing in the field. Also if the quality of the saltpeter was low (for instance if it was contaminated with highly hygroscopic calcium nitrate), or if the powder was simply old (due to the mildly hygroscopic nature of potassium nitrate), in humid weather it would need to be re-dried. The dust from "repairing" powder in the field was a major hazard. Loading cannons or bombards before the powder-making advances of the Renaissance was a skilled art. Fine powder loaded haphazardly or too tightly would burn incompletely or too slowly. Typically, the breech-loading powder chamber in the rear of the piece was filled only about half full, the serpentine powder neither too compressed nor too loose, a wooden bung pounded in to seal the chamber from the barrel when assembled, and the projectile placed on. A carefully determined empty space was necessary for the charge to burn effectively. When the cannon was fired through the touchhole, turbulence from the initial surface combustion caused the rest of the powder to be rapidly exposed to the flame. The advent of much more powerful and easy to use ''corned'' powder changed this procedure, but serpentine was used with older guns into the 17th century.Corning

For propellants to oxidize and burn rapidly and effectively, the combustible ingredients must be reduced to the smallest possible particle sizes, and be as thoroughly mixed as possible. Once mixed, however, for better results in a gun, makers discovered that the final product should be in the form of individual dense grains that spread the fire quickly from grain to grain, much asstraw

Straw is an agricultural byproduct consisting of the dry stalks of cereal plants after the grain and chaff have been removed. It makes up about half of the yield of cereal crops such as barley, oats, rice, rye and wheat. It has a number ...

or twigs catch fire more quickly than a pile of sawdust.

In late 14th century Europe and China, gunpowder was improved by wet grinding; liquid, such as distilled spirits was added during the grinding-together of the ingredients and the moist paste dried afterwards. The principle of wet mixing to prevent the separation of dry ingredients, invented for gunpowder, is used today in the pharmaceutical industry. It was discovered that if the paste was rolled into balls before drying the resulting gunpowder absorbed less water from the air during storage and traveled better. The balls were then crushed in a mortar by the gunner immediately before use, with the old problem of uneven particle size and packing causing unpredictable results. If the right size particles were chosen, however, the result was a great improvement in power. Forming the damp paste into ''corn''-sized clumps by hand or with the use of a sieve instead of larger balls produced a product after drying that loaded much better, as each tiny piece provided its own surrounding air space that allowed much more rapid combustion than a fine powder. This "corned" gunpowder was from 30% to 300% more powerful. An example is cited where of serpentine was needed to shoot a ball, but only of corned powder.

Because the dry powdered ingredients must be mixed and bonded together for extrusion and cut into grains to maintain the blend, size reduction and mixing is done while the ingredients are damp, usually with water. After 1800, instead of forming grains by hand or with sieves, the damp ''mill-cake'' was pressed in molds to increase its density and extract the liquid, forming ''press-cake''. The pressing took varying amounts of time, depending on conditions such as atmospheric humidity. The hard, dense product was broken again into tiny pieces, which were separated with sieves to produce a uniform product for each purpose: coarse powders for cannons, finer grained powders for muskets, and the finest for small hand guns and priming. Inappropriately fine-grained powder often caused cannons to burst before the projectile could move down the barrel, due to the high initial spike in pressure. ''Mammoth'' powder with large grains, made for Rodman's 15-inch cannon, reduced the pressure to only 20 percent as high as ordinary cannon powder would have produced.

In the mid-19th century, measurements were made determining that the burning rate within a grain of black powder (or a tightly packed mass) is about 6 cm/s (0.20 feet/s), while the rate of ignition propagation from grain to grain is around 9 m/s (30 feet/s), over two orders of magnitude faster.

Modern types

Modern corning first compresses the fine black powder meal into blocks with a fixed density (1.7 g/cm3). In the United States, gunpowder grains were designated F (for fine) or C (for coarse). Grain diameter decreased with a larger number of Fs and increased with a larger number of Cs, ranging from about for 7F to for 7C. Even larger grains were produced for artillery bore diameters greater than about . The standard DuPont ''Mammoth'' powder developed by Thomas Rodman and

Modern corning first compresses the fine black powder meal into blocks with a fixed density (1.7 g/cm3). In the United States, gunpowder grains were designated F (for fine) or C (for coarse). Grain diameter decreased with a larger number of Fs and increased with a larger number of Cs, ranging from about for 7F to for 7C. Even larger grains were produced for artillery bore diameters greater than about . The standard DuPont ''Mammoth'' powder developed by Thomas Rodman and Lammot du Pont

Lammot du Pont I (April 13, 1831 – March 29, 1884) was a chemist and a key member of the du Pont family and its company in the mid-19th century.

Early life

Du Pont was born in 1831 in New Castle County, Delaware, the son of Margaretta Elizabeth ...

for use during the American Civil War had grains averaging in diameter with edges rounded in a glazing barrel. Other versions had grains the size of golf and tennis balls for use in Rodman guns.Brown, G.I. (1998) ''The Big Bang: A history of Explosives'' Sutton Publishing pp. 22, 32 In 1875 DuPont introduced ''Hexagonal'' powder for large artillery, which was pressed using shaped plates with a small center core—about diameter, like a wagon wheel nut, the center hole widened as the grain burned. By 1882 German makers also produced hexagonal grained powders of a similar size for artillery.

By the late 19th century manufacturing focused on standard grades of black powder from Fg used in large bore rifles and shotguns, through FFg (medium and small-bore arms such as muskets and fusils), FFFg (small-bore rifles and pistols), and FFFFg (extreme small bore, short pistols and most commonly for priming flintlocks). A coarser grade for use in military artillery blanks was designated A-1. These grades were sorted on a system of screens with oversize retained on a mesh of 6 wires per inch, A-1 retained on 10 wires per inch, Fg retained on 14, FFg on 24, FFFg on 46, and FFFFg on 60. Fines designated FFFFFg were usually reprocessed to minimize explosive dust hazards. In the United Kingdom, the main service gunpowders were classified RFG (rifle grained fine) with diameter of one or two millimeters and RLG (rifle grained large) for grain diameters between two and six millimeters. Gunpowder grains can alternatively be categorized by mesh size: the BSS sieve mesh size, being the smallest mesh size, which retains no grains. Recognized grain sizes are Gunpowder G 7, G 20, G 40, and G 90.

Owing to the large market of antique and replica black-powder firearms in the US, modern black powder substitutes like Pyrodex

A black powder substitute is a replacement for black powder used in muzzleloading and cartridge firearms. Black powder substitutes offer a number of advantages over black powder, primarily including reduced sensitivity as an explosive and incre ...

, Triple Seven and Black Mag3 pellets have been developed since the 1970s. These products, which should not be confused with smokeless powders, aim to produce less fouling (solid residue), while maintaining the traditional volumetric measurement system for charges. Claims of less corrosiveness of these products have been controversial however. New cleaning products for black-powder guns have also been developed for this market.

Chemistry

A simple, commonly cited, chemical equation for the combustion of gunpowder is: : 2 KNO3 + S + 3 C → K2S + N2 + 3 CO2. A balanced, but still simplified, equation is: : 10 KNO3 + 3 S + 8 C → 2 K2CO3 + 3 K2SO4 + 6 CO2 + 5 N2. The exact percentages of ingredients varied greatly through the medieval period as the recipes were developed by trial and error, and needed to be updated for changing military technology. Gunpowder does not burn as a single reaction, so the byproducts are not easily predicted. One study showed that it produced (in order of descending quantities) 55.91% solid products: potassium carbonate, potassium sulfate,potassium sulfide

Potassium sulfide is an inorganic compound with the formula K2 S. The colourless solid is rarely encountered, because it reacts readily with water, a reaction that affords potassium hydrosulfide (KSH) and potassium hydroxide (KOH). Most commonly ...

, sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

, potassium nitrate, potassium thiocyanate, carbon, ammonium carbonate and 42.98% gaseous products: carbon dioxide, nitrogen, carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The unde ...

, hydrogen, methane, 1.11% water.

Gunpowder made with less-expensive and more plentiful sodium nitrate instead of potassium nitrate (in appropriate proportions) works just as well. However, it is more hygroscopic than powders made from potassium nitrate. Muzzleloader

A muzzleloader is any firearm into which the projectile and the propellant charge is loaded from the muzzle of the gun (i.e., from the forward, open end of the gun's barrel). This is distinct from the modern (higher tech and harder to make) design ...

s have been known to fire after hanging on a wall for decades in a loaded state, provided they remained dry. By contrast, gunpowder made with sodium nitrate must be kept sealed to remain stable.

Gunpowder releases 3 megajoules

The joule ( , ; symbol: J) is the unit of energy in the International System of Units (SI). It is equal to the amount of work done when a force of 1 newton displaces a mass through a distance of 1 metre in the direction of the force applied. ...

per kilogram

The kilogram (also kilogramme) is the unit of mass in the International System of Units (SI), having the unit symbol kg. It is a widely used measure in science, engineering and commerce worldwide, and is often simply called a kilo colloquially ...

and contains its own oxidant. This is less than TNT (4.7 megajoules per kilogram), or gasoline (47.2 megajoules per kilogram in combustion, but gasoline requires an oxidant; for instance, an optimized gasoline and O2 mixture releases 10.4 megajoules per kilogram, taking into account the mass of the oxygen).

Gunpowder also has a low energy density

In physics, energy density is the amount of energy stored in a given system or region of space per unit volume. It is sometimes confused with energy per unit mass which is properly called specific energy or .

Often only the ''useful'' or extract ...

compared to modern "smokeless" powders, and thus to achieve high energy loadings, large amounts are needed with heavy projectiles.

Production

For the most powerful black powder,

For the most powerful black powder, meal powder Meal powder is the fine dust left over when black powder (gunpowder) is corned and screened to separate it into different grain sizes. It is used extensively in various pyrotechnic procedures, usually to prime other compositions. It can also be u ...

, a wood charcoal, is used. The best wood for the purpose is Pacific willow, but others such as alder or buckthorn

''Rhamnus'' is a genus of about 110 accepted species of shrubs or small trees, commonly known as buckthorns, in the family Rhamnaceae. Its species range from tall (rarely to ) and are native mainly in east Asia and North America, but found thr ...

can be used. In Great Britain between the 15th and 19th centuries charcoal from alder buckthorn was greatly prized for gunpowder manufacture; cottonwood was used by the American Confederate States. The ingredients are reduced in particle size and mixed as intimately as possible. Originally, this was with a mortar-and-pestle or a similarly operating stamping-mill, using copper, bronze or other non-sparking materials, until supplanted by the rotating ball mill

A ball mill is a type of grinder used to grind or blend materials for use in mineral dressing processes, paints, pyrotechnics, ceramics, and selective laser sintering. It works on the principle of impact and attrition: size reduction is done ...

principle with non-sparking bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

or lead. Historically, a marble or limestone edge runner mill, running on a limestone bed, was used in Great Britain; however, by the mid 19th century this had changed to either an iron-shod stone wheel or a cast iron wheel running on an iron bed. The mix was dampened with alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

or water during grinding to prevent accidental ignition. This also helps the extremely soluble saltpeter to mix into the microscopic pores of the very high surface-area charcoal.

Around the late 14th century, European powdermakers first began adding liquid during grinding to improve mixing, reduce dust, and with it the risk of explosion. The powder-makers would then shape the resulting paste of dampened gunpowder, known as mill cake, into corns, or grains, to dry. Not only did corned powder keep better because of its reduced surface area, gunners also found that it was more powerful and easier to load into guns. Before long, powder-makers standardized the process by forcing mill cake through sieves instead of corning powder by hand.

The improvement was based on reducing the surface area of a higher density composition. At the beginning of the 19th century, makers increased density further by static pressing. They shoveled damp mill cake into a two-foot square box, placed this beneath a screw press and reduced it to half its volume. "Press cake" had the hardness of slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

. They broke the dried slabs with hammers or rollers, and sorted the granules with sieves into different grades. In the United States, Eleuthere Irenee du Pont, who had learned the trade from Lavoisier, tumbled the dried grains in rotating barrels to round the edges and increase durability during shipping and handling. (Sharp grains rounded off in transport, producing fine "meal dust" that changed the burning properties.)

Another advance was the manufacture of kiln charcoal by distilling wood in heated iron retorts instead of burning it in earthen pits. Controlling the temperature influenced the power and consistency of the finished gunpowder. In 1863, in response to high prices for Indian saltpeter, DuPont