Guadeloupe Demography on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=

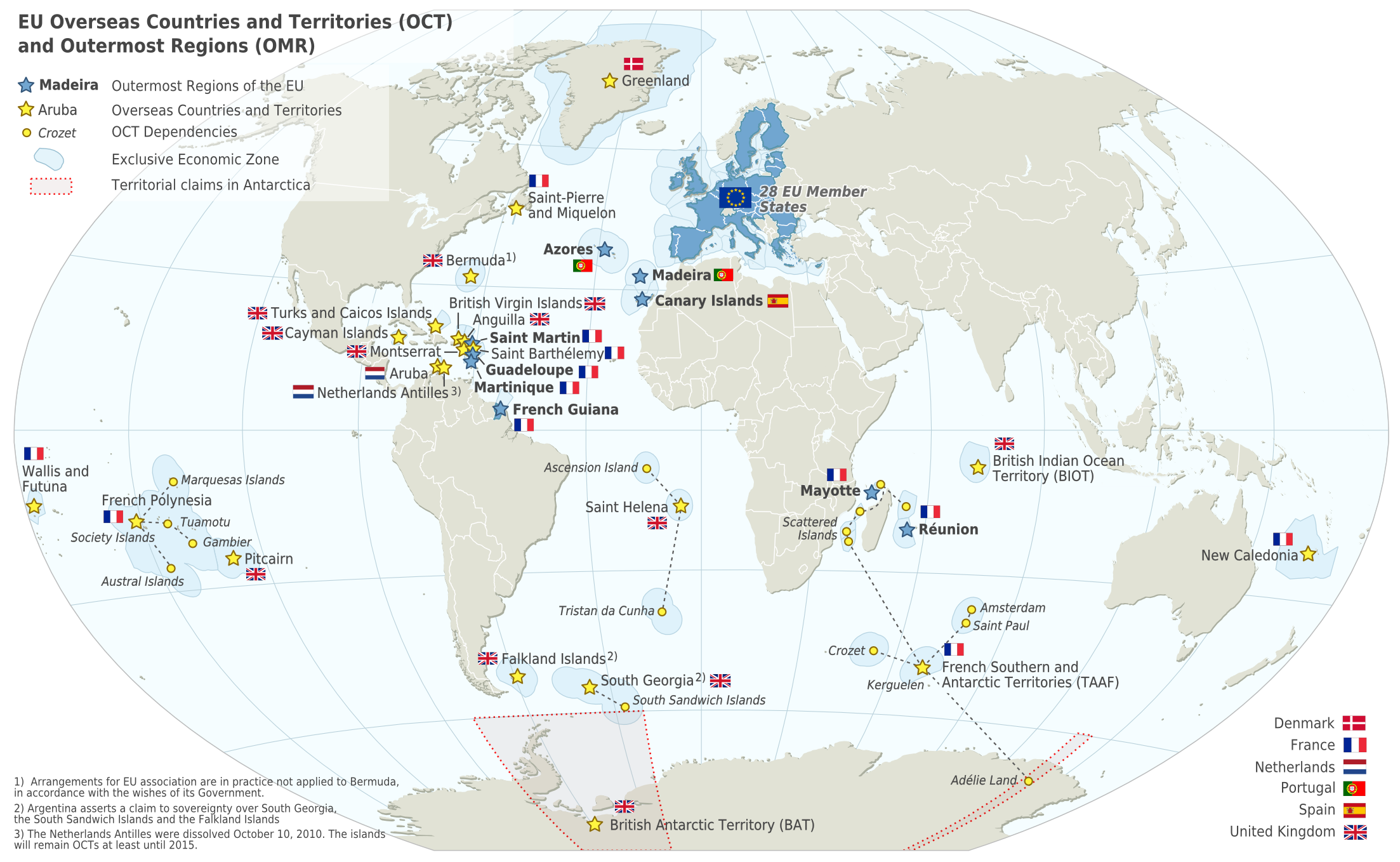

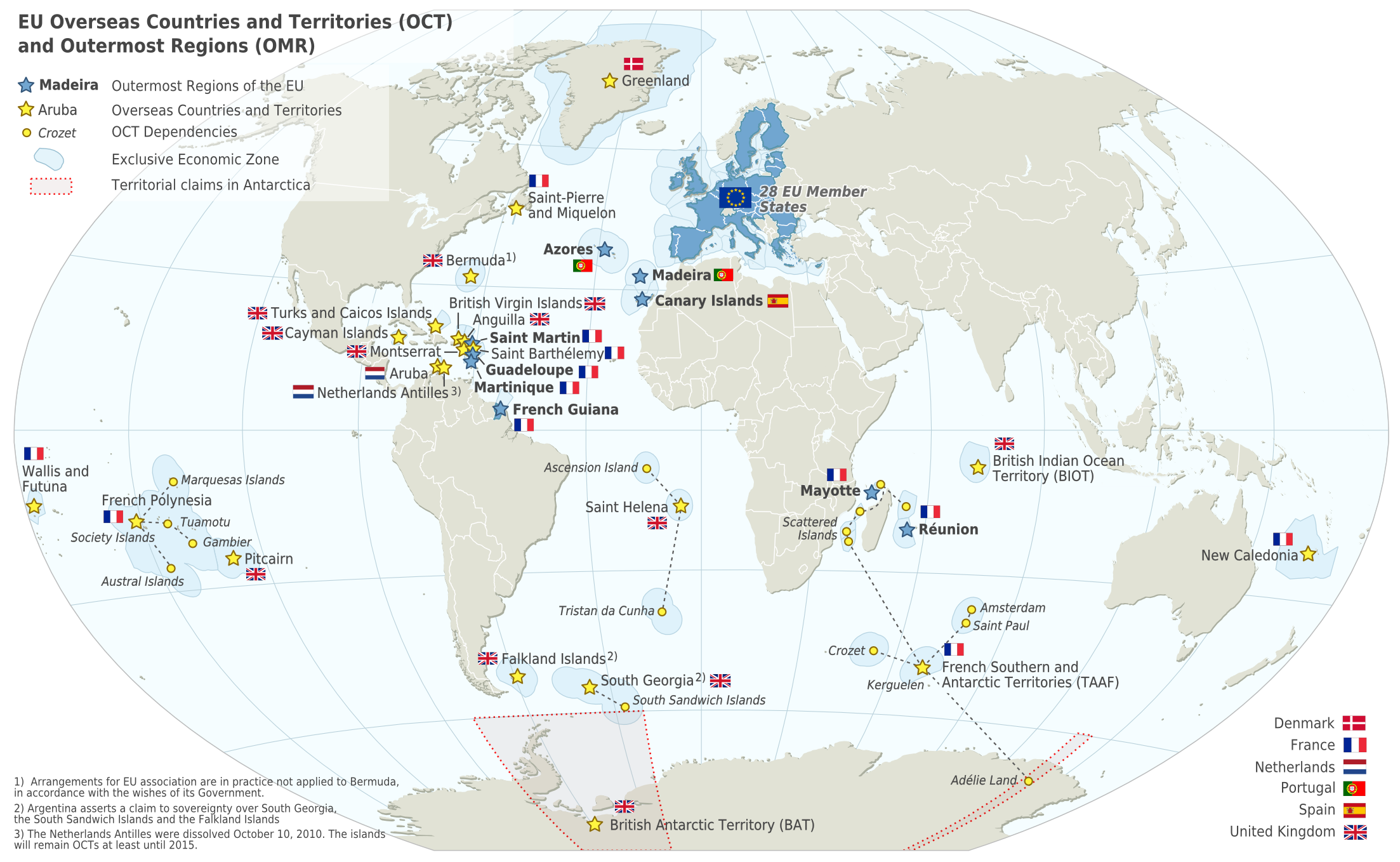

INSEE Like the other overseas departments, it is an integral part of France. As a constituent territory of the

The archipelago was called (or "The Island of Beautiful Waters") by the native

The archipelago was called (or "The Island of Beautiful Waters") by the native

The islands were first populated by

The islands were first populated by

The

The  In 1802, the

In 1802, the

'' AFP'' Tourism suffered greatly during this time and affected the 2010 tourist season as well.

Guadeloupe is an archipelago of more than 12 islands, as well as

Guadeloupe is an archipelago of more than 12 islands, as well as

With fertile volcanic soils, heavy rainfall and a warm climate, vegetation on Basse-Terre is lush. Most of the islands' forests are on Basse-Terre, containing such species as

With fertile volcanic soils, heavy rainfall and a warm climate, vegetation on Basse-Terre is lush. Most of the islands' forests are on Basse-Terre, containing such species as

The Guadalupe

The Guadalupe

Legislative powers are centred on the separate

Legislative powers are centred on the separate

This offers France important fishing resources and independence to develop a sovereign policy of underwater research and protection (protection of

This offers France important fishing resources and independence to develop a sovereign policy of underwater research and protection (protection of

Image:Flag_of_France.svg, National flag of France

Image:Unofficial flag of Guadeloupe (local).svg, Colonial flag of Guadeloupe

Image:Flag of Guadeloupe (local) variant.svg, Red variant of the colonial sun flag

Image:Flag of Guadeloupe (UPLG).svg, Flag used by the independence and the cultural movements

Image:Flag of Guadeloupe (Local).svg, Logo of the Regional Council of Guadeloupe

The economy of Guadeloupe depends on tourism, agriculture,

The economy of Guadeloupe depends on tourism, agriculture,

A Guadeloupean béké first wrote Creole at the end of the 17th century, transcribing it using

A Guadeloupean béké first wrote Creole at the end of the 17th century, transcribing it using

About 80% of the population is

About 80% of the population is

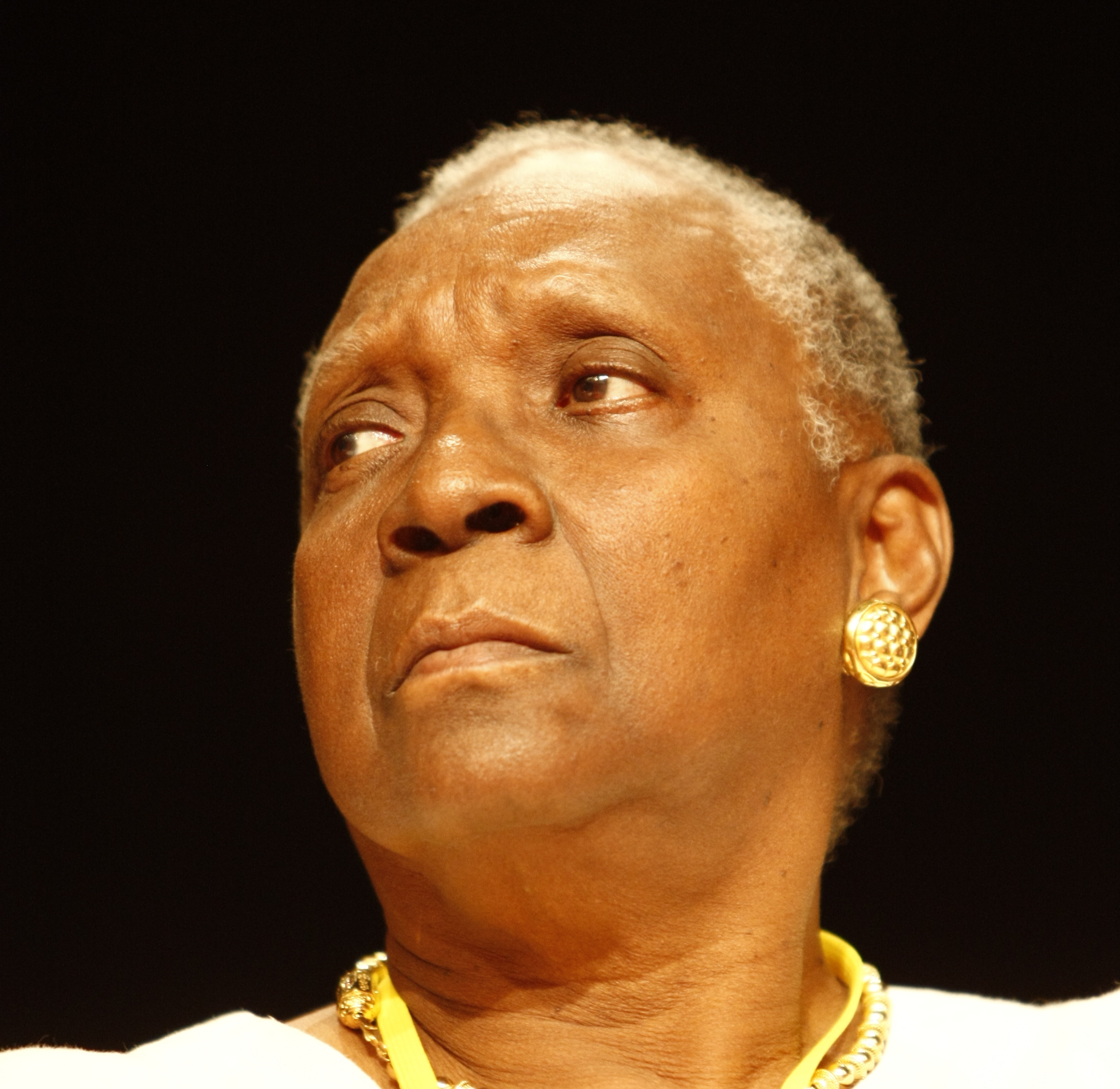

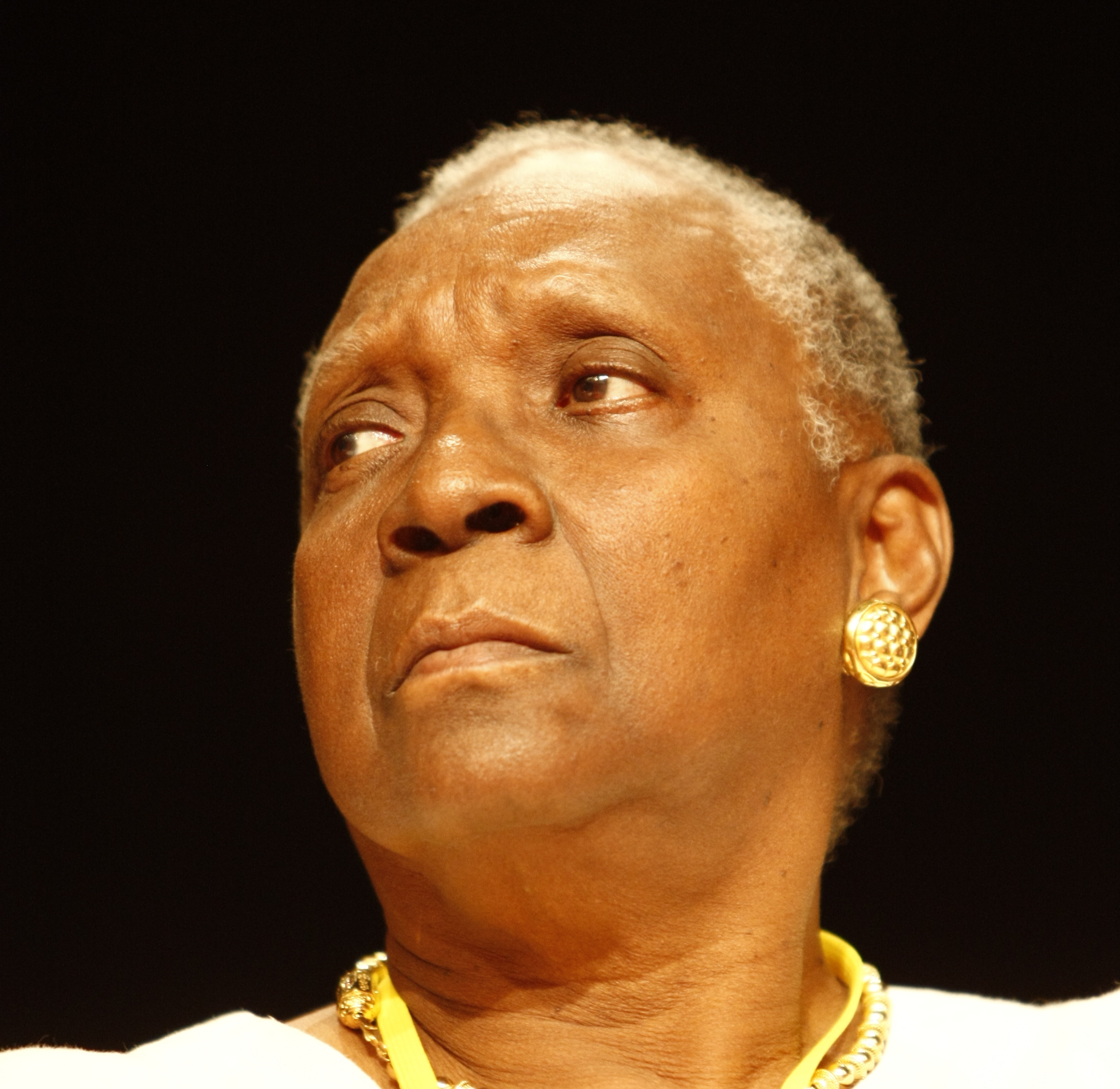

Guadeloupe has always had a rich literary output, with Guadeloupean author

Guadeloupe has always had a rich literary output, with Guadeloupean author

(1)

or Tom Frager focus on more international genres such as rock or Another element of Guadeloupean culture is its dress. A few women (particularly of the older generation) wear a unique style of traditional dress, with many layers of colourful fabric, now only worn on special occasions. On festive occasions they also wore a madras (originally a "kerchief" from South India) headscarf tied in many different symbolic ways, each with a different name. The headdress could be tied in the "bat" style, or the "firefighter" style, as well as the "Guadeloupean woman". Jewellery, mainly gold, is also important in the Guadeloupean lady's dress, a product of European, African and Indian inspiration.

Another element of Guadeloupean culture is its dress. A few women (particularly of the older generation) wear a unique style of traditional dress, with many layers of colourful fabric, now only worn on special occasions. On festive occasions they also wore a madras (originally a "kerchief" from South India) headscarf tied in many different symbolic ways, each with a different name. The headdress could be tied in the "bat" style, or the "firefighter" style, as well as the "Guadeloupean woman". Jewellery, mainly gold, is also important in the Guadeloupean lady's dress, a product of European, African and Indian inspiration.

* The four-pointed headdress (headdress with four knots) means "my heart has room for whoever wants it! ";

* The three-pointed headdress means "my heart is taken!".

* The two-pointed headdress means "my heart is compromised, but you can try your luck! ";

* The one-ended headdress means "my heart is free! "

* The four-pointed headdress (headdress with four knots) means "my heart has room for whoever wants it! ";

* The three-pointed headdress means "my heart is taken!".

* The two-pointed headdress means "my heart is compromised, but you can try your luck! ";

* The one-ended headdress means "my heart is free! "

In the category of

In the category of

Football (soccer) is popular in Guadeloupe, and several notable footballers are of Guadeloupean origin, including

Football (soccer) is popular in Guadeloupe, and several notable footballers are of Guadeloupean origin, including  The island is internationally known for hosting the Karujet Race – Jet Ski World Championship since 1998. This nine-stage, four-day event attracts competitors from around the world (mostly Caribbeans, Americans, and Europeans). The Karujet, generally made up of seven races around the island, has an established reputation as one of the most difficult championships in which to compete.

The

The island is internationally known for hosting the Karujet Race – Jet Ski World Championship since 1998. This nine-stage, four-day event attracts competitors from around the world (mostly Caribbeans, Americans, and Europeans). The Karujet, generally made up of seven races around the island, has an established reputation as one of the most difficult championships in which to compete.

The

Guadeloupe is served by a number of

Guadeloupe is served by a number of

45,626 students in secondary education;

* 2,718 graduate students in high school.

* Since 2014, the academy has 12 districts divided into 5 poles:Académie de Guadeloupe, répartition des 12 circonscriptions, pdf.

* The Pôle Îles du Nord ( St. Martin and St. Barthélemy);

* The Basse-Terre Nord Pole (Baie-Mahault, Capesterre-Belle-Eau and Sainte-Rose) ;

* The South Pole of Basse-Terre: Basse-Terre and Bouillante (including the islands of Les Saintes);

* The North Pole of Grande-Terre: Grande-Terre Nord, Sainte-Anne and Saint-François (including the islands of La Désirade and Marie-Galante);

* The South Pole of Grande-Terre: Les Abymes, Gosier and Pointe-à-Pitre.

The islands of Guadeloupe also have two local campuses of the

45,626 students in secondary education;

* 2,718 graduate students in high school.

* Since 2014, the academy has 12 districts divided into 5 poles:Académie de Guadeloupe, répartition des 12 circonscriptions, pdf.

* The Pôle Îles du Nord ( St. Martin and St. Barthélemy);

* The Basse-Terre Nord Pole (Baie-Mahault, Capesterre-Belle-Eau and Sainte-Rose) ;

* The South Pole of Basse-Terre: Basse-Terre and Bouillante (including the islands of Les Saintes);

* The North Pole of Grande-Terre: Grande-Terre Nord, Sainte-Anne and Saint-François (including the islands of La Désirade and Marie-Galante);

* The South Pole of Grande-Terre: Les Abymes, Gosier and Pointe-à-Pitre.

The islands of Guadeloupe also have two local campuses of the

The Energy transition Law (TECV) provides for 50% renewable energy by 2020 in the territory. And the Guadeloupe EPP plans to develop 66 MW of additional biomass capacity between 2018 and 2023, including 43 MW to replace coal.

For example, the Albioma, Albioma Caraïbes (AC) coal-fired power plant will be converted to biomass to help increase the share of Renewable energy, renewables in Guadeloupe's energy mix from 20.5% to 35%, thereby mitigating the island's dependence on fossil fuels and reducing acidic air pollution and the production of toxic and bottom ash.

This 34 MW power plant, producing 260 GWh/year of electricity in 2018 (i.e. 15% of the island's needs), should reduce 265 000 t of Carbon dioxide, equivalent/year throughout the chain (−87% once converted to biomass compared to the previous situation, coal).

Guadeloupe has an electricity production plant, in Le Moule, based on the sugar cane agricultural sector, which recovers the residues from sugar cane crushing (bagasse) to produce energy; 12 wind farms, such as in Désirade, Le Moule or Marie-Galante; a geothermal power plant in Bouillante, which uses the energy of water vapor produced by volcanic activity (the plant's electricity production ranks it first nationally); a project to harness the energy of waves and ocean currents; photovoltaic installations that contribute to the operation of solar water heaters for homes and to the development of the electric vehicle sector.

Electricity produced by hydropower, which represents 2.2% of total production, comes from dams built on the beds of certain rivers.

The Energy transition Law (TECV) provides for 50% renewable energy by 2020 in the territory. And the Guadeloupe EPP plans to develop 66 MW of additional biomass capacity between 2018 and 2023, including 43 MW to replace coal.

For example, the Albioma, Albioma Caraïbes (AC) coal-fired power plant will be converted to biomass to help increase the share of Renewable energy, renewables in Guadeloupe's energy mix from 20.5% to 35%, thereby mitigating the island's dependence on fossil fuels and reducing acidic air pollution and the production of toxic and bottom ash.

This 34 MW power plant, producing 260 GWh/year of electricity in 2018 (i.e. 15% of the island's needs), should reduce 265 000 t of Carbon dioxide, equivalent/year throughout the chain (−87% once converted to biomass compared to the previous situation, coal).

Guadeloupe has an electricity production plant, in Le Moule, based on the sugar cane agricultural sector, which recovers the residues from sugar cane crushing (bagasse) to produce energy; 12 wind farms, such as in Désirade, Le Moule or Marie-Galante; a geothermal power plant in Bouillante, which uses the energy of water vapor produced by volcanic activity (the plant's electricity production ranks it first nationally); a project to harness the energy of waves and ocean currents; photovoltaic installations that contribute to the operation of solar water heaters for homes and to the development of the electric vehicle sector.

Electricity produced by hydropower, which represents 2.2% of total production, comes from dams built on the beds of certain rivers.

, "Death in Paradise: Ben Miller on investigating the deadliest place on the planet," ''Radio Times'', 8 January 2013 it was the most violence, violent overseas French departments of France, department in 2016. The murder rate is slightly more than that of Paris, at 8.2 per 100,000. The high level of unemployment caused violence and crime to rise, especially in 2009 and 2010, the years following the Great Recession. Residents of Guadeloupe describe the island as a place with little everyday crime, and most violence is caused by the drug trade or domestic disputes. In 2021, additional police officers were deployed to the island in the face of rioting arising out of Covid-19 restrictions. Normally, about 2,000 police officers are present on the island including some 760 active National Gendarmerie of the COMGEND (Gendarmerie Command of Guadeloupe) region plus around 260 reservists. The active Gendarmerie include three Mobile Gendarmerie Squadrons (EGM) and a Republican Guard (France), Republican Guard Intervention Platoon (PIGR). The Maritime Gendarmerie deploys the patrol boat Violette (P722) in the territory.

Prefecture website

Regional Council website

Departmental Council website

{{Authority control Guadeloupe, Dependent territories in the Caribbean Overseas departments of France French Caribbean Leeward Islands (Caribbean) Lesser Antilles Regions of France Outermost regions of the European Union Former British colonies and protectorates in the Americas British Caribbean Former Swedish colonies Former colonies in North America French Union Island countries French-speaking countries and territories Populated places established in the 4th century 1674 establishments in the French colonial empire 1674 establishments in North America 1759 disestablishments in the French colonial empire 1759 disestablishments in North America 1759 establishments in the British Empire 1759 establishments in North America 1763 disestablishments in the British Empire 1763 disestablishments in North America 1763 establishments in the French colonial empire 1763 establishments in North America 1810 establishments in the British Empire 1810 disestablishments in the French colonial empire 1810 disestablishments in North America 1810 establishments in North America 1816 disestablishments in the British Empire 1816 disestablishments in North America 1816 establishments in the French colonial empire 1816 establishments in North America

Antillean Creole

Antillean Creole (Antillean French Creole, Kreyol, Kwéyòl, Patois) is a French-based creole that is primarily spoken in the Lesser Antilles. Its grammar and vocabulary include elements of Carib, English, and African languages.

Antillean Creol ...

, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre

Basse-Terre (, ; ; gcf, label=Guadeloupean Creole, Bastè, ) is a commune in the French overseas department of Guadeloupe, in the Lesser Antilles. It is also the ''prefecture'' (capital city) of Guadeloupe. The city of Basse-Terre is located ...

, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante

Marie-Galante ( gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Mawigalant) is one of the islands that form Guadeloupe, an overseas department of France. Marie-Galante has a land area of . It had 11,528 inhabitants at the start of 2013, but by the start of 2018 ...

, La Désirade

La Désirade is an island in the French West Indies, in the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean. It forms part of Guadeloupe, an overseas region of France.

History

Archaeological evidence has been discovered that suggests that an Amerindian p ...

, and the two inhabited Îles des Saintes

The Îles des Saintes (; "Islands of the Female Saints"), also known as Les Saintes, is a group of small islands in the archipelago of Guadeloupe, an overseas department of France. It is part of the Canton of Trois-Rivières and is divided in ...

—as well as many uninhabited islands and outcroppings. It is south of Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda (, ) is a sovereign country in the West Indies. It lies at the juncture of the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean in the Leeward Islands part of the Lesser Antilles, at 17°N latitude. The country consists of two maj ...

and Montserrat

Montserrat ( ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about long and wide, with r ...

, north of the Commonwealth of Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It ...

. The region's capital city is Basse-Terre

Basse-Terre (, ; ; gcf, label=Guadeloupean Creole, Bastè, ) is a commune in the French overseas department of Guadeloupe, in the Lesser Antilles. It is also the ''prefecture'' (capital city) of Guadeloupe. The city of Basse-Terre is located ...

, located on the southern west coast of Basse-Terre Island; however, the most populous city is Les Abymes and the main centre of business is neighbouring Pointe-à-Pitre

Pointe-à-Pitre (; gcf, label=Guadeloupean Creole, Pwentapit, , or simply , ) is the second largest (most populous) city of Guadeloupe after Les Abymes. Guadeloupe is an overseas region and Overseas department, department of France located in the ...

, both located on Grande-Terre Island. It had a population of 384,239 in 2019.Populations légales 2019: 971 GuadeloupeINSEE Like the other overseas departments, it is an integral part of France. As a constituent territory of the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

and the Eurozone

The euro area, commonly called eurozone (EZ), is a currency union of 19 member states of the European Union (EU) that have adopted the euro (€) as their primary currency and sole legal tender, and have thus fully implemented EMU policies ...

, the euro

The euro ( symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 19 out of the member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 340 million citizens . ...

is its official currency and any European Union citizen is free to settle and work there indefinitely. However, as an overseas department, it is not part of the Schengen Area

The Schengen Area ( , ) is an area comprising 27 European countries that have officially abolished all passport and all other types of border control at their mutual borders. Being an element within the wider area of freedom, security and j ...

. The region formerly included Saint Barthélemy

Saint Barthélemy (french: Saint-Barthélemy, ), officially the Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Barthélemy, is an overseas collectivity of France in the Caribbean. It is often abbreviated to St. Barth in French, and St. Barts in English ...

and Saint Martin, which were detached from Guadeloupe in 2007 following a 2003 referendum.

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

visited Guadeloupe in 1493, during his second voyage, and gave the island its name. The official language is French; Antillean Creole

Antillean Creole (Antillean French Creole, Kreyol, Kwéyòl, Patois) is a French-based creole that is primarily spoken in the Lesser Antilles. Its grammar and vocabulary include elements of Carib, English, and African languages.

Antillean Creol ...

is also spoken.

Etymology

The archipelago was called (or "The Island of Beautiful Waters") by the native

The archipelago was called (or "The Island of Beautiful Waters") by the native Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Great ...

people.

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

named the island in 1493 after Our Lady of Guadalupe

Our Lady of Guadalupe ( es, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), also known as the Virgin of Guadalupe ( es, Virgen de Guadalupe), is a Catholic title of Mary, mother of Jesus associated with a series of five Marian apparitions, which are believed t ...

, a shrine to the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother o ...

venerated in the Spanish town of Guadalupe, Extremadura. When the area became a French colony, the Spanish name was retained - though altered to French orthography

French orthography encompasses the spelling and punctuation of the French language. It is based on a combination of phoneme, phonemic and historical principles. The spelling of words is largely based on the pronunciation of Old French c. 1100–1 ...

and phonology

Phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages or dialects systematically organize their sounds or, for sign languages, their constituent parts of signs. The term can also refer specifically to the sound or sign system of a ...

. The islands are locally known as .

History

Pre-colonial era

The islands were first populated by

The islands were first populated by indigenous peoples of the Americas

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

Many Indigenous peoples of the A ...

, possibly as far back as 3000 BCE. The Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Great ...

people are the first identifiable group, but they were later displaced circa 1400 CE by Kalina

Kalina may refer to:

People

* Kalina people, or Caribs, an indigenous people of the northern coastal areas of South America

* Kalina language, or Carib, the language of the Kalina people

* Kalina (given name)

* Kalina (surname)

* Noah Kalina, ...

-Carib peoples.

15th–17th centuries

Christopher Columbus was the first European to see Guadeloupe, landing in November 1493 and giving it its current name. Several attempts at colonisation by the Spanish in the 16th century failed due to attacks from the native peoples. In 1626, the French underPierre Belain d'Esnambuc

Pierre Belain, sieur d'Esnambuc (; 1585–1636) was a French trader and adventurer in the Caribbean, who established the first permanent French colony, Saint-Pierre, on the island of Martinique in 1635.

Biography Youth

Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc wa ...

began to take an interest in Guadeloupe, expelling Spanish settlers. The Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique The Company of the American Islands (french: Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique) was a French chartered company that in 1635 took over the administration of the French portion of ''Saint-Christophe island'' (Saint Kitts) from the Compagnie de Saint- ...

settled in Guadeloupe in 1635, under the direction of Charles Liénard de L'Olive

Charles Liénard, sieur de L'Olive ( – 1643) was a French colonial leader who was the first governor of Guadeloupe.

Life

Charles Lienard, squire and sieur de L'Olive, was the son of Pierre Lienart and Françoise Bonnart of Chinon.

The Fren ...

and Jean du Plessis d'Ossonville; they formally took possession of the island for France and brought in French farmers to colonise the land. This led to the death of many indigenous people by disease and violence. By 1640, however, the Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique had gone bankrupt, and they thus sold Guadeloupe to Charles Houël du Petit Pré Charles Houël du Petit Pré (1616—22 April 1682) was a French governor of Guadeloupe from 1643 to 1664. He was also knight and lord.

He became, by a royal proclamation dated August 1645, the first of the island judicial officer. He is named Marq ...

who began plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

agriculture, with the first African slaves arriving in 1650. Slave resistance was immediately widespread, with an open uprising in 1656 lasting several weeks and a simultaneous spate of mass desertions that lasted at least two years until the French compelled indigenous peoples to stop assisting them. Ownership of the island passed to the French West India Company

The French West India Company (french: Compagnie française des Indes occidentales) was a French trading company founded on 28 May 1664, some three months before the foundation of the corresponding eastern company, by Jean-Baptiste Colbert and diss ...

before it was annexed to France in 1674 under the tutelage of their Martinique colony. Institutionalised slavery, enforced by the Code Noir

The (, ''Black code'') was a decree passed by the French King Louis XIV in 1685 defining the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire. The decree restricted the activities of free people of color, mandated the conversion of all e ...

from 1685, led to a booming sugar plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

economy.

18th–19th centuries

During theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

captured and occupied the islands until the 1763 Treaty of Paris. During that time, Pointe-à-Pitre

Pointe-à-Pitre (; gcf, label=Guadeloupean Creole, Pwentapit, , or simply , ) is the second largest (most populous) city of Guadeloupe after Les Abymes. Guadeloupe is an overseas region and Overseas department, department of France located in the ...

became a major harbour, and markets in Britain's North American colonies were opened to Guadeloupean sugar, which was traded for foodstuffs and timber. The economy expanded quickly, creating vast wealth for the French colonists. So prosperous was Guadeloupe at the time that, under the 1763 Treaty of Paris, France forfeited its Canadian colonies in exchange for the return of Guadeloupe. Coffee planting began in the late 1720s, also worked by slaves and, by 1775, cocoa

Cocoa may refer to:

Chocolate

* Chocolate

* ''Theobroma cacao'', the cocoa tree

* Cocoa bean, seed of ''Theobroma cacao''

* Chocolate liquor, or cocoa liquor, pure, liquid chocolate extracted from the cocoa bean, including both cocoa butter and ...

had become a major export product as well.

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

brought chaos to Guadeloupe. Under new revolutionary law, freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

were entitled to equal rights. Taking advantage of the chaotic political situation, Britain invaded Guadeloupe in 1794. The French responded by sending an expeditionary force led by Victor Hugues

Jean-Baptiste Victor Hugues sometimes spelled Hughes (July 20, 1762 in Marseille – August 12, 1826 in Cayenne) was a French politician and colonial administrator during the French Revolution, who governed Guadeloupe from 1794 to 1798, emancipa ...

, who retook the islands and abolished slavery. More than 1,000 French colonists were killed in the aftermath.

First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Eu ...

reinstated the pre-revolutionary government and slavery, prompting a slave rebellion led by Louis Delgrès. The French authorities responded quickly, culminating in the Battle of Matouba on 28 May 1802. Realising they had no chance of success, Delgrès and his followers committed mass suicide by deliberately exploding their gunpowder stores. In 1810, the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

captured the island again, handing it over to Sweden under the 1813 Treaty of Stockholm.

In the 1814 Treaty of Paris, Sweden ceded Guadeloupe to France, giving rise to the Guadeloupe Fund The Guadeloupe Fund ( sv, Guadeloupefonden) was established by Sweden's Riksdag of the Estates in 1815 for the benefit of Crown Prince and Regent Charles XIV John of Sweden, (Swedish: ''Karl XIV Johan'') also known as ''Jean Baptiste Jules Bernado ...

. In 1815, the Treaty of Vienna acknowledged French control of Guadeloupe.

Slavery was abolished in the French Empire in 1848. After 1854, indentured labourers from the French colony of Pondicherry

Pondicherry (), now known as Puducherry ( French: Pondichéry ʊdʊˈtʃɛɹi(listen), on-dicherry, is the capital and the most populous city of the Union Territory of Puducherry in India. The city is in the Puducherry district on the sout ...

in India were brought in. Emancipated slaves had the vote from 1849, but French nationality and the vote were not granted to Indian citizens until 1923, when a long campaign, led by Henry Sidambarom Henry Sidambarom (5 July 1863 – 15 September 1952) was a Justice of the Peace and defender of the cause of Indian workers in Guadeloupe. He was born in Capesterre-Belle-Eau, Guadeloupe, and was a Guadeloupean of Indian origin.

In 1884, he ...

, finally achieved success.

20th–21st centuries

In 1936, Félix Éboué became the first black governor of Guadeloupe. During the Second World War Guadeloupe initially came under the control of theVichy government

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

, later joining Free France

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

in 1943. In 1946, the colony of Guadeloupe became an overseas department of France.

Tensions arose in the post-war era over the social structure of Guadeloupe and its relationship with mainland France. The 'Massacre of St Valentine' occurred in 1952, when striking factory workers in Le Moule

Le Moule ( gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Moul) is the sixth-largest commune in the French overseas department of Guadeloupe. It is located on the northeast side of the island of Grande-Terre.

History

Beginning 1635 with the arrival of the French ...

were shot at by the Compagnies républicaines de sécurité

The Compagnies républicaines de sécurité (, ''Republican Security Corps''), abbreviated CRS, are the general reserve of the French National Police. They are primarily involved in general security missions but the task for which they are be ...

, resulting in four deaths. In May 1967 racial tensions exploded into rioting following a racist attack on a black Guadeloupean, resulting in eight deaths.

An independence movement grew in the 1970s, prompting France to declare Guadeloupe a French region in 1974. The Union populaire pour la libération de la Guadeloupe (UPLG) campaigned for complete independence, and by the 1980s the situation had turned violent with the actions of groups such as Groupe de libération armée (GLA) and Alliance révolutionnaire caraïbe (ARC).

Greater autonomy was granted to Guadeloupe in 2000. Through a referendum in 2003, Saint-Martin and Saint Barthélemy

Saint Barthélemy (french: Saint-Barthélemy, ), officially the Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Barthélemy, is an overseas collectivity of France in the Caribbean. It is often abbreviated to St. Barth in French, and St. Barts in English ...

voted to separate from the administrative jurisdiction of Guadeloupe, this being fully enacted by 2007.

In January 2009, labour unions and others known as the Liyannaj Kont Pwofitasyon ''Liyannaj Kont Pwofitasyon'', or LKP, is an umbrella group of approximately fifty trade unions and social movements in Guadeloupe. It spearheaded the general strike beginning in January 2009.

Name

The name of the umbrella group comes from the ...

went on strike

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the I ...

for more pay. Strikers were angry with low wages, the high cost of living, high levels of poverty relative to mainland France and levels of unemployment that are amongst the worst in the European Union. The situation quickly escalated, exacerbated by what was seen as an ineffectual response by the French government, turning violent and prompting the deployment of extra police after a union leader ( Jacques Bino) was shot and killed. The strike lasted 44 days and had also inspired similar actions on nearby Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

. President Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Paul Stéphane Sarközy de Nagy-Bocsa (; ; born 28 January 1955) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012.

Born in Paris, he is of Hungarian, Greek Jewish, and French origin. Mayor of Neuilly-sur-Se ...

later visited the island, promising reform.Sarkozy offers autonomy vote for Martinique'' AFP'' Tourism suffered greatly during this time and affected the 2010 tourist season as well.

Geography

Guadeloupe is an archipelago of more than 12 islands, as well as

Guadeloupe is an archipelago of more than 12 islands, as well as islet

An islet is a very small, often unnamed island. Most definitions are not precise, but some suggest that an islet has little or no vegetation and cannot support human habitation. It may be made of rock, sand and/or hard coral; may be permanent ...

s and rocks situated where the northeastern Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

meets the western Atlantic Ocean. It is located in the Leeward Islands

french: Îles-Sous-le-Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Leeward Islands. Clockwise: Antigua and Barbuda, Guadeloupe, Saint kitts and Nevis.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean SeaNorth Atlantic Ocean

, coor ...

in the northern part of the Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc betwe ...

, a partly volcanic island arc

Island arcs are long chains of active volcanoes with intense seismic activity found along convergent tectonic plate boundaries. Most island arcs originate on oceanic crust and have resulted from the descent of the lithosphere into the mantle alon ...

. To the north lie Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda (, ) is a sovereign country in the West Indies. It lies at the juncture of the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean in the Leeward Islands part of the Lesser Antilles, at 17°N latitude. The country consists of two maj ...

and the British Overseas Territory

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs), also known as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), are fourteen dependent territory, territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom. They are the last remna ...

of Montserrat

Montserrat ( ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about long and wide, with r ...

, with Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographically ...

lying to the south.

The two main islands are Basse-Terre (west) and Grande-Terre (east), which form a butterfly shape as viewed from above, the two 'wings' of which are separated by the Grand Cul-de-Sac Marin, and Petit Cul-de-Sac Marin. More than half of Guadeloupe's land surface consists of the 847.8 km2 Basse-Terre. The island is mountainous, containing such peaks as Mount Sans Toucher (4,442 feet; 1,354 metres) and Grande Découverte (4,143 feet; 1,263 metres), culminating in the active volcano La Grande Soufrière

La Grande Soufrière ( en, "big sulfur outlet"), is an active stratovolcano on the French island of Basse-Terre, in Guadeloupe. It is the highest mountain peak in the Lesser Antilles, rising 1,467 m high.

The last magmatic eruption was in 1 ...

, the highest mountain peak in the Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc betwe ...

with an elevation of . In contrast Grande-Terre is mostly flat, with rocky coasts to the north, irregular hills at the centre, mangrove at the southwest, and white sand beaches sheltered by coral reefs

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of Colony (biology), colonies of coral polyp (zoology), polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, wh ...

along the southern shore. This is where the main tourist resorts are found.

Marie-Galante

Marie-Galante ( gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Mawigalant) is one of the islands that form Guadeloupe, an overseas department of France. Marie-Galante has a land area of . It had 11,528 inhabitants at the start of 2013, but by the start of 2018 ...

is the third-largest island, followed by La Désirade

La Désirade is an island in the French West Indies, in the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean. It forms part of Guadeloupe, an overseas region of France.

History

Archaeological evidence has been discovered that suggests that an Amerindian p ...

, a north-east slanted limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

plateau, the highest point of which is . To the south lies the Îles de Petite-Terre, which are two islands (Terre de Haut and Terre de Bas) totalling 2 km2.

Les Saintes is an archipelago of eight islands of which two, Terre-de-Bas

Terre-de-Bas (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Tèdéba) is a commune in the French overseas department and region of Guadeloupe, in the Lesser Antilles. Terre-de-Bas is made up of Terre-de-Bas Island and several uninhabited islands and islets ...

and Terre-de-Haut

Terre-de-Haut (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Tèdého) is a commune in the French overseas department of Guadeloupe, including Terre-de-Haut Island and a few other small uninhabited islands of the archipelago (''les Roches Percées''; ''Îlet ...

are inhabited. The landscape is similar to that of Basse-Terre, with volcanic hills and irregular shoreline with deep bays.

There are numerous other smaller islands.

Geology

Basse-Terre is a volcanic island. The Lesser Antilles are at the outer edge of theCaribbean Plate

The Caribbean Plate is a mostly oceanic tectonic plate underlying Central America and the Caribbean Sea off the north coast of South America.

Roughly 3.2 million square kilometers (1.2 million square miles) in area, the Caribbean Plate borders ...

, and Guadeloupe is part of the outer arc of the Lesser Antilles Volcanic Arc

The Lesser Antilles Volcanic Arc is a volcanic arc that forms the eastern boundary of the Caribbean Plate. It is part of a subduction zone, also known as the Lesser Antilles subduction zone, where the oceanic crust of the North American Plate i ...

. Many of the islands were formed as a result of the subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

of oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafic cumu ...

of the Atlantic Plate under the Caribbean Plate

The Caribbean Plate is a mostly oceanic tectonic plate underlying Central America and the Caribbean Sea off the north coast of South America.

Roughly 3.2 million square kilometers (1.2 million square miles) in area, the Caribbean Plate borders ...

in the Lesser Antilles subduction zone

The Lesser Antilles subduction zone is a convergent plate boundary on the seafloor along the eastern margin of the Lesser Antilles Volcanic Arc. In this subduction zone, oceanic crust of the South American Plate is being subducted under the Cari ...

. This process is ongoing and is responsible for volcanic and earthquake activity in the region. Guadeloupe was formed from multiple volcanoes, of which only La Grande Soufrière is not extinct. Its last eruption was in 1976, and led to the evacuation of the southern part of Basse-Terre. 73,600 people were displaced throughout three and a half months following the eruption.

K–Ar dating

Potassium–argon dating, abbreviated K–Ar dating, is a radiometric dating method used in geochronology and archaeology. It is based on measurement of the product of the radioactive decay of an isotope of potassium (K) into argon (Ar). Potassium ...

indicates that the three northern massif

In geology, a massif ( or ) is a section of a planet's crust that is demarcated by faults or flexures. In the movement of the crust, a massif tends to retain its internal structure while being displaced as a whole. The term also refers to a ...

s on Basse-Terre Island

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

are 2.79 million years old. Sections of volcanoes collapsed and eroded within the last 650,000 years, after which the Sans Toucher volcano grew in the collapsed area. Volcanoes in the north of Basse-Terre Island mainly produced andesite

Andesite () is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predomi ...

and basaltic andesite

Basaltic andesite is a volcanic rock that is intermediate in composition between basalt and andesite. It is composed predominantly of augite and plagioclase. Basaltic andesite can be found in volcanoes around the world, including in Central Amer ...

. There are several beaches of dark or "black" sand.

La Désirade, east of the main islands, has a basement

A basement or cellar is one or more floors of a building that are completely or partly below the ground floor. It generally is used as a utility space for a building, where such items as the furnace, water heater, breaker panel or fuse box, ...

from the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

, overlaid with thick limestones

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms when th ...

from the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Quaternary

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million years ...

periods.

Grande-Terre and Marie-Galante have basements probably composed of volcanic units of Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

to Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but the ...

, but there are no visible outcrops. On Grande-Terre, the overlying carbonate platform

A carbonate platform is a sedimentary body which possesses topographic relief, and is composed of autochthonic calcareous deposits. Platform growth is mediated by sessile organisms whose skeletons build up the reef or by organisms (usually microb ...

is 120 metres thick.

Climate

The islands are part of theLeeward Islands

french: Îles-Sous-le-Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Leeward Islands. Clockwise: Antigua and Barbuda, Guadeloupe, Saint kitts and Nevis.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean SeaNorth Atlantic Ocean

, coor ...

, so called because they are downwind of the prevailing trade wind

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisph ...

s, which blow out of the northeast. This was significant in the days of sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships c ...

s. Grande-Terre is so named because it is on the eastern, or windward

Windward () and leeward () are terms used to describe the direction of the wind. Windward is ''upwind'' from the point of reference, i.e. towards the direction from which the wind is coming; leeward is ''downwind'' from the point of reference ...

side, exposed to the Atlantic winds. Basse-Terre is so named because it is on the leeward

Windward () and leeward () are terms used to describe the direction of the wind. Windward is ''upwind'' from the point of reference, i.e. towards the direction from which the wind is coming; leeward is ''downwind'' from the point of reference ...

south-west side and sheltered from the winds. Guadeloupe has a tropical climate

Tropical climate is the first of the five major climate groups in the Köppen climate classification identified with the letter A. Tropical climates are defined by a monthly average temperature of 18 °C (64.4 °F) or higher in the cool ...

tempered by maritime influences and the Trade Winds

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisph ...

. There are two seasons, the dry season called "Lent" from January to June, and the wet season called "winter", from July to December.

Tropical cyclones and storm surges

Located in a very exposed region, Guadeloupe and its dependencies have to face manycyclones

In meteorology, a cyclone () is a large air mass that rotates around a strong center of low atmospheric pressure, counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from above (opposite to an anti ...

. The deadliest hurricane to hit Guadeloupe was the Pointe-à-Pitre hurricane of 1776, which killed at least 6,000 people.

On 16 September 1989, Hurricane Hugo

Hurricane Hugo was a powerful Cape Verde tropical cyclone that inflicted widespread damage across the northeastern Caribbean and the Southeastern United States in September 1989. Across its track, Hugo affected approximately 2 million peop ...

caused severe damage to the islands of the archipelago and left a deep mark on the memory of the local inhabitants. In 1995, three hurricanes (Iris, Luis and Marilyn) hit the archipelago in less than three weeks.

Some of the deadliest hurricanes that have hit Guadeloupe are the following:

In the 20th century: 12 September 1928: 1928 Okeechobee hurricane

The Okeechobee hurricane of 1928, also known as the San Felipe Segundo hurricane, was one of the deadliest hurricanes in the recorded history of the North Atlantic basin, and the fourth deadliest hurricane in the United States, only behind the ...

; 11 August 1956: Hurricane Betsy

Hurricane Betsy was an intense and destructive tropical cyclone that brought widespread damage to areas of Florida and the central United States Gulf Coast in September 1965. The storm's erratic nature, coupled with its intensity and minim ...

; 22 August 1964: Hurricane Cleo

Hurricane Cleo was the strongest tropical cyclone of the 1964 Atlantic hurricane season. It was the third named storm, first hurricane, and first major hurricane of the season. Cleo was one of the longest-lived storms of the season. This compa ...

; 27 September 1966: Hurricane Inez

Hurricane Inez was a powerful major hurricane that affected the Caribbean, Bahamas, Florida, and Mexico in 1966. It was the first storm on record to affect all of those areas. It originated from a tropical wave over Africa, and became a tropical ...

; 16–17 September 1989: Hurricane Hugo; 14–15 September 1995: Hurricane Marilyn

Hurricane Marilyn was the most powerful hurricane to strike the Virgin Islands since Hurricane Hugo of 1989, and the third such tropical cyclone in roughly a two-week time span to strike or impact the Leeward Islands, the others being Hurricane ...

.

In the 21st century: 6 September 2017: Hurricane Irma

Hurricane Irma was an extremely powerful Cape Verde hurricane that caused widespread destruction across its path in September 2017. Irma was the first Category 5 hurricane to strike the Leeward Islands on record, followed by Maria two ...

; 18–19 September 2017: Hurricane Maria

Hurricane Maria was a deadly Saffir–Simpson scale#Category 5, Category 5 Tropical cyclone, hurricane that devastated the northeastern Caribbean in September 2017, particularly Dominica, Saint Croix, and Puerto Rico. It is regarded as the wo ...

.

Flora

With fertile volcanic soils, heavy rainfall and a warm climate, vegetation on Basse-Terre is lush. Most of the islands' forests are on Basse-Terre, containing such species as

With fertile volcanic soils, heavy rainfall and a warm climate, vegetation on Basse-Terre is lush. Most of the islands' forests are on Basse-Terre, containing such species as mahogany

Mahogany is a straight-grained, reddish-brown timber of three tropical hardwood species of the genus ''Swietenia'', indigenous to the AmericasBridgewater, Samuel (2012). ''A Natural History of Belize: Inside the Maya Forest''. Austin: Unive ...

, ironwood

Ironwood is a common name for many woods or plants that have a reputation for hardness, or specifically a wood density that is heavier than water (approximately 1000 kg/m3, or 62 pounds per cubic foot), although usage of the name ironwood in E ...

and chestnut tree

The chestnuts are the deciduous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Castanea'', in the beech family Fagaceae. They are native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

The name also refers to the edible nuts they produce.

The unrelat ...

s. Mangrove swamps

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evolution in severa ...

line the Salée River. Much of the forest on Grande-Terre has been cleared, with only a few small patches remaining.

Between of altitude, the rainforest

Rainforests are characterized by a closed and continuous tree canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforest can be classified as tropical rainforest or temperate rainfores ...

that covers a large part of the island of Basse-Terre develops. There we find the white gum tree, the acomat-boucan or chestnut tree, the marbri or bois-bandé or the oleander; shrubs and herbaceous plants such as the mountain palm, the balisier or ferns; many epiphytes: bromeliads

The Bromeliaceae (the bromeliads) are a family of monocot flowering plants of about 80 genera and 3700 known species, native mainly to the tropical Americas, with several species found in the American subtropics and one in tropical west Africa, ...

, philodendrons, orchids

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant.

Along with the Asteraceae, they are one of the two largest families of flowering ...

and lianas

A liana is a long- stemmed, woody vine that is rooted in the soil at ground level and uses trees, as well as other means of vertical support, to climb up to the canopy in search of direct sunlight. The word ''liana'' does not refer to a ta ...

. Above , the humid savannah develops, composed of mosses, lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship.mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evoluti ...

, high altitude violet or mountain thyme.

The dry forest

Dry or dryness most often refers to:

* Lack of rainfall, which may refer to

**Arid regions

**Drought

* Dry or dry area, relating to legal prohibition of selling, serving, or imbibing alcoholic beverages

* Dry humor, deadpan

* Dryness (medical)

* ...

occupies a large part of the islands of Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, Les Saintes, La Désirade

La Désirade is an island in the French West Indies, in the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean. It forms part of Guadeloupe, an overseas region of France.

History

Archaeological evidence has been discovered that suggests that an Amerindian p ...

and also develops on the leeward coast of Basse-Terre. The coastal forest is more difficult to develop because of the nature of the soil (sandy, rocky), salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal ...

, sunshine and wind and is the environment where the sea grape, the mancenilla (a very toxic tree whose trunk is marked with a red line), the icaquier or the Coconut

The coconut tree (''Cocos nucifera'') is a member of the palm tree family ( Arecaceae) and the only living species of the genus ''Cocos''. The term "coconut" (or the archaic "cocoanut") can refer to the whole coconut palm, the seed, or the ...

tree grow. On the cliffs

In geography and geology, a cliff is an area of rock which has a general angle defined by the vertical, or nearly vertical. Cliffs are formed by the processes of weathering and erosion, with the effect of gravity. Cliffs are common on co ...

and in the Arid

A region is arid when it severely lacks available water, to the extent of hindering or preventing the growth and development of plant and animal life. Regions with arid climates tend to lack vegetation and are called xeric or desertic. Most ar ...

zones are found cacti such as the cactus-cigar (Cereus), the prickly pear, the chestnut cactus, the "Tête à l'anglais" cactus and the aloes.

The Mangrove

A mangrove is a shrub or tree that grows in coastal saline water, saline or brackish water. The term is also used for tropical coastal vegetation consisting of such species. Mangroves are taxonomically diverse, as a result of convergent evoluti ...

forest that borders some of Guadalupe's coasts is structured in three levels, from the closest to the sea to the farthest. On the first level are the red mangroves; on the second, about from the sea, the black mangroves form the shrubby mangrove; on the third level the white mangroves form the tall mangrove. Behind the mangrove, where the tide and salt do not penetrate, a swamp forest sometimes develops, unique in Guadeloupe. The representative species of this environment is the Mangrove-medaille.

Fauna

Few terrestrial mammals, aside from bats andraccoons

The raccoon ( or , ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes called the common raccoon to distinguish it from other species, is a mammal native to North America. It is the largest of the procyonid family, having a body length of , and a body weight of . ...

, are native to the islands. The introduced Javan mongoose

The Javan mongoose (''Urva javanica'') is a mongoose species native to Southeast Asia.

Taxonomy

''Ichneumon javanicus'' was the scientific name proposed by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire in 1818. It was later classified in the genus ''Herpestes' ...

is also present on Guadeloupe. Bird species include the endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

purple-throated carib

The purple-throated carib (''Eulampis jugularis'') is a species of hummingbird in the subfamily Polytminae. It is resident on most of the islands of the Lesser Antilles and has occurred as a vagrant both further north and south.HBW and BirdLife ...

and the Guadeloupe woodpecker

The Guadeloupe woodpecker (''Melanerpes herminieri'') or Tapeur is a species of bird in the woodpecker family Picidae belonging to the genus ''Melanerpes.'' Endemic to the Guadeloupe archipelago in the Lesser Antilles, it is a medium-sized fores ...

. The waters of the islands support a rich variety of marine life.

However, by studying 43,000 bone remains from six islands in the archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

, 50 to 70% of snakes and lizards on the Guadeloupe Islands became extinct after European colonists arrived, who had brought with them mammals such as cats, mongooses, rats, and raccoons, which might have preyed upon the native reptiles.

Environmental preservation

In recent decades, Guadeloupe's natural environments have been affected by hunting and fishing, forest retreat, urbanization and suburbanization. They also suffer from the development of intensive crops (banana andsugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalks t ...

, in particular), which reached their peak in the years 1955–75. This has led to the following situation: seagrass beds and reefs

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral or similar relatively stable material, lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic processes—deposition of sand, wave erosion planing down rock out ...

have degraded by up to 50% around the large islands; mangroves and mantids

Mantidae is one of the largest families in the order of praying mantises, based on the type species '' Mantis religiosa''; however, most genera are tropical or subtropical. Historically, this was the only family in the order, and many referen ...

have almost disappeared in Marie-Galante

Marie-Galante ( gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Mawigalant) is one of the islands that form Guadeloupe, an overseas department of France. Marie-Galante has a land area of . It had 11,528 inhabitants at the start of 2013, but by the start of 2018 ...

, Les Saintes and La Désirade; the salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal ...

of the fresh water table has increased due to "the intensity of use of the layer"; and pollution of agricultural origin (pesticides and nitrogenous compounds).

In addition, the ChlEauTerre study, unveiled in March 2018, concludes that 37 different anthropogenic

Anthropogenic ("human" + "generating") is an adjective that may refer to:

* Anthropogeny, the study of the origins of humanity

Counterintuitively, anthropogenic may also refer to things that have been generated by humans, as follows:

* Human im ...

molecules (more than half of which come from residues of now-banned pesticides, such as chlordecone) were found in "79% of the watersheds analyzed in Grande-Terre and 84% in Basse-Terre." A report by the Guadeloupe Water Office notes that in 2019 there is a "generalized degradation

Degradation may refer to:

Science

* Degradation (geology), lowering of a fluvial surface by erosion

* Degradation (telecommunications), of an electronic signal

* Biodegradation of organic substances by living organisms

* Environmental degradatio ...

of water bodies."

Despite everything, there is a will to preserve these environments

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, all living and non-living things occurring naturally

* Biophysical environment, the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism or ...

whose vegetation and landscape

A landscape is the visible features of an area of land, its landforms, and how they integrate with natural or man-made features, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.''New Oxford American Dictionary''. A landscape includes the ...

are preserved in some parts of the islands and constitute a sensitive asset for tourism. These areas are partially protected and classified as ZNIEFF, sometimes with nature reserve status, and several caves are home to protected chiropterans.

The Guadalupe

The Guadalupe National Park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

was created on 20 February 1989. In 1992, under the auspices of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

, the Biosphere Reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or o ...

of the Guadeloupe Archipelago (''Réserve de biosphère de l'archipel de la Guadeloupe'') was created. As a result, on 8 December 1993, the marine site of Grand Cul-de-sac was listed as a wetland of international importance. The island thus became the overseas department

The overseas departments and regions of France (french: départements et régions d'outre-mer, ; ''DROM'') are departments of France that are outside metropolitan France, the European part of France. They have exactly the same status as mainlan ...

with the most protected area

Protected areas or conservation areas are locations which receive protection because of their recognized natural, ecological or cultural values. There are several kinds of protected areas, which vary by level of protection depending on the ena ...

s.

Earthquakes and tsunamis

The archipelago is crossed by numerous geological faults such as those of la Barre or la Cadoue, while in depth, in front of Moule andLa Désirade

La Désirade is an island in the French West Indies, in the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean. It forms part of Guadeloupe, an overseas region of France.

History

Archaeological evidence has been discovered that suggests that an Amerindian p ...

begins the Désirade Fault, and between the north of Maria-Galante and the south of Grande-Terre begins the Maria Galante Fault. And it is because of these geological characteristics, the islands of the department of Guadeloupe are classified in zone III according to the seismic zoning of France and are subject to a specific risk prevention plan.

The 1843 earthquake in the Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc betwe ...

is, to this day, the most violent earthquake known. It caused the death of more than a thousand people, as well as major damage in Pointe-à-Pitre.

On 21 November 2004, the islands of the department, in particular Les Saintes archipelago, were shaken by a violent earthquake that reached a magnitude of 6.3 on the Richter scale

The Richter scale —also called the Richter magnitude scale, Richter's magnitude scale, and the Gutenberg–Richter scale—is a measure of the strength of earthquakes, developed by Charles Francis Richter and presented in his landmark 1935 ...

and caused the death of one person, as well as extensive material damage.

Demographics

Guadeloupe recorded a population of 402,119 in the 2017 census. The population is mainlyAfro-Caribbean

Afro-Caribbean people or African Caribbean are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the modern African-Caribbeans descend from Africans taken as slaves to colonial Caribbean via the ...

. European, Indian (Tamil, Telugu, and other South Indians), Lebanese, Syrians

Syrians ( ar, سُورِيُّون, ''Sūriyyīn'') are an Eastern Mediterranean ethnic group indigenous to the Levant. They share common Levantine Semitic roots. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend of both indi ...

, and Chinese are all minorities. There is also a substantial population of Haitians

Haitians ( French: , ht, Ayisyen) are the citizens of Haiti and the descendants in the diaspora through direct parentage. An ethnonational group, Haitians generally comprise the modern descendants of self-liberated Africans in the Caribbean te ...

in Guadeloupe who work mainly in construction and as street vendors. Basse-Terre

Basse-Terre (, ; ; gcf, label=Guadeloupean Creole, Bastè, ) is a commune in the French overseas department of Guadeloupe, in the Lesser Antilles. It is also the ''prefecture'' (capital city) of Guadeloupe. The city of Basse-Terre is located ...

is the political capital; however, the largest city and economic hub is Pointe-à-Pitre

Pointe-à-Pitre (; gcf, label=Guadeloupean Creole, Pwentapit, , or simply , ) is the second largest (most populous) city of Guadeloupe after Les Abymes. Guadeloupe is an overseas region and Overseas department, department of France located in the ...

.

The population of Guadeloupe has been decreasing by 0.8% per year since 2013. In 2017 the average population density in Guadeloupe was , which is very high in comparison to metropolitan France's average of . One third of the land is devoted to agriculture and all mountains are uninhabitable; this lack of space and shelter makes the population density even higher.

Major urban areas

The most populousurban unit

In France, an urban unit (''fr: "unité urbaine"'') is a statistical area defined by INSEE, the French national statistics office, for the measurement of contiguously built-up areas. According to the INSEE definition , an "unité urbaine" is a ...

(agglomeration) is Pointe-à-Pitre

Pointe-à-Pitre (; gcf, label=Guadeloupean Creole, Pwentapit, , or simply , ) is the second largest (most populous) city of Guadeloupe after Les Abymes. Guadeloupe is an overseas region and Overseas department, department of France located in the ...

- Les Abymes, which covers 11 communes and 65% of the population of the department. The three largest urban units are:

Health

In 2011,life expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of its birth, current age, and other demographic factors like sex. The most commonly used measure is life expectancy at birth ...

at birth was recorded at 77.0 years for males and 83.5 for females.

Medical centres in Guadeloupe include: University Hospital Centre (CHU) in Pointe-à-Pitre, Regional Hospital Centre (CHR) in Basse-Terre, and four hospitals located in Capesterre-Belle-Eau, Pointe-Noire, Bouillante and Saint-Claude.

The ''Institut Pasteur de la Guadeloupe'', is located in Pointe-à-Pitre and is responsible for researching environmental hygiene, vaccinations, and the spread of tuberculosis and mycobacteria

Immigration

The relative wealth of Guadeloupe contrasts with theextreme poverty

Extreme poverty, deep poverty, abject poverty, absolute poverty, destitution, or penury, is the most severe type of poverty, defined by the United Nations (UN) as "a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, includi ...

of several islands in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

region, which makes the community an attractive place for the populations of some of these territories. In addition, other factors, such as political instability and natural disasters, explain this immigration. As early as the 1970s, the first illegal immigrants of Haitian origin arrived in Guadeloupe to meet a need for labour in the agricultural sector; alongside this Haitian immigration

Haiti has a sizeable diaspora, present primarily in the United States, Dominican Republic, Cuba, Canada, France (including its French Caribbean territories), the Bahamas, Brazil and Chile. They also live in other countries like Belgium, Turks an ...

, which is more visible because it is more numerous, Guadeloupe has also seen the arrival and settlement of populations from the island of Dominica and the Dominican Republic. In 2005, the prefecture, which represents the State in Guadeloupe, reported figures of between 50,000 and 60,000 foreigners in the department.

Migration

Created in 1963 by Michel Debré, Bumidom's objective was to " ..contribute to the solution of demographic problems in the overseas departments". To this end, its missions were multiple: information for future emigrants, vocational training, family reunification and management of reception centres. At the time, this project was also seen as a means to diminish the influence of theWest Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). For more than 100 years the words ''West Indian'' specifically described natives of the West Indies, but by 1661 Europeans had begun to use it ...

independence movements, which were gaining strength in the 1960s.

Between 1963 and 1981, an estimated 16,562 Guadeloupeans emigrated to metropolitan France

Metropolitan France (french: France métropolitaine or ''la Métropole''), also known as European France (french: Territoire européen de la France) is the area of France which is geographically in Europe. This collective name for the European ...

through Bumidom. And the miniseries Le Rêve français (The French Dream) sets out to recount some of the consequences of the emigration of West Indians and Reunionese to France.

An estimated 50,000 Guadeloupeans and Martinicans participated in the construction of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

between 1904 and 1914. In 2014, it was estimated that there were between 60,000 and 70,000 descendants of these West Indians living in Panama. Other waves of migration to North America, especially to Canada, occurred at the beginning of the 20th century.

Governance

Together withMartinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

, La Réunion

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figure ...

, Mayotte

Mayotte (; french: Mayotte, ; Shimaore: ''Maore'', ; Kibushi: ''Maori'', ), officially the Department of Mayotte (french: Département de Mayotte), is an overseas department and region and single territorial collectivity of France. It is loc ...

and French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic ...

, Guadeloupe is one of the overseas departments

The overseas departments and regions of France (french: départements et régions d'outre-mer, ; ''DROM'') are departments of France that are outside metropolitan France, the European part of France. They have exactly the same status as mainlan ...

, being both a region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and the interaction of humanity and t ...

and a department combined into one entity. It is also an outermost region of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

. The inhabitants of Guadeloupe are French citizens with full political and legal rights.

Legislative powers are centred on the separate

Legislative powers are centred on the separate departmental

''Departmental'' is a 1980 Australian TV movie based on a play by Mervyn Rutherford. It was part of the ABC's Australian Theatre Festival.Ed. Scott Murray, ''Australia on the Small Screen 1970-1995'', Oxford Uni Press, 1996 p43 Reviews were poor ...

and regional

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and the interaction of humanity and t ...