Greece–Turkey Relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Relations between

Following the Greek War of Independence, Greece was formed as an independent state in 1830. Relations between Greece and the Ottoman Empire were shaped by the Eastern Question and the

Following the Greek War of Independence, Greece was formed as an independent state in 1830. Relations between Greece and the Ottoman Empire were shaped by the Eastern Question and the

Greece occupied Smyrna on 15 May 1919, while

Greece occupied Smyrna on 15 May 1919, while

Following the population exchange, Greece wanted to end hostilities but negotiations stalled because of the issue of valuations of the properties of the exchanged populations. Driven by

Following the population exchange, Greece wanted to end hostilities but negotiations stalled because of the issue of valuations of the properties of the exchanged populations. Driven by

Following the power vacuum left by the ending of the Axis occupation after the war, the

Following the power vacuum left by the ending of the Axis occupation after the war, the  According to

According to  In 1955, the

In 1955, the

In 1995, relations began to change with the Greek election of

In 1995, relations began to change with the Greek election of

Greece has been a member of the EU since 1981. Cyprus joined in 2004. Turkey submitted its application to join in 1987 and became a full candidate in 1999.

Until 1999, Greece concentrated its diplomatic efforts on barring Turkey's admission to the EU. Concerns about Turkey like its human rights record and Greece's veto ultimately had Turkey side-lined by the EU. Domestically, this contributed to the shift away from Turkey's founding secular doctrine ''

Greece has been a member of the EU since 1981. Cyprus joined in 2004. Turkey submitted its application to join in 1987 and became a full candidate in 1999.

Until 1999, Greece concentrated its diplomatic efforts on barring Turkey's admission to the EU. Concerns about Turkey like its human rights record and Greece's veto ultimately had Turkey side-lined by the EU. Domestically, this contributed to the shift away from Turkey's founding secular doctrine ''

The 2010 discovery of gas deposits in the eastern Mediterranean first by Israel and then Egypt, has created new energy to fan the disputes. It is estimated 5% of the worlds known natural gas reserves are in the eastern Mediterranean. The historical security issues of the Aegean and Cyprus are now a focal point to resolving Europe's energy needs. For example, the 2016 Turkey-Israel reconciliation led to Greece torpedoing the 2017 Cyprus UN talks due to their relationship's risk for developing a gas pipeline. In 2019, the east Mediterranean gas forum was created, including seven countries but excluding Turkey.

The region is considered the end-point for east–west pipelines. In 2007, the countries inaugurated the Greek-Turkish natural gas pipeline giving Caspian gas its first direct Western outlet. The Caspian Sea is one of the oldest oil-producing regions: it's estimated to have 48 billion barrels of oil in proven and probable reserves. Its estimated it has 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The opening up of these fields is recent after more than 20 years of negotiation following the 2018 A

The 2010 discovery of gas deposits in the eastern Mediterranean first by Israel and then Egypt, has created new energy to fan the disputes. It is estimated 5% of the worlds known natural gas reserves are in the eastern Mediterranean. The historical security issues of the Aegean and Cyprus are now a focal point to resolving Europe's energy needs. For example, the 2016 Turkey-Israel reconciliation led to Greece torpedoing the 2017 Cyprus UN talks due to their relationship's risk for developing a gas pipeline. In 2019, the east Mediterranean gas forum was created, including seven countries but excluding Turkey.

The region is considered the end-point for east–west pipelines. In 2007, the countries inaugurated the Greek-Turkish natural gas pipeline giving Caspian gas its first direct Western outlet. The Caspian Sea is one of the oldest oil-producing regions: it's estimated to have 48 billion barrels of oil in proven and probable reserves. Its estimated it has 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The opening up of these fields is recent after more than 20 years of negotiation following the 2018 A

Examples of minority mistreatment include:

* During World War II, the nationalisation of industry with the

Examples of minority mistreatment include:

* During World War II, the nationalisation of industry with the

Turkey has become a transit country for people entering Europe. In 2015, the route that passes from Turkey to Greece and then through the Balkan countries became the most used route for migrants escaping conflicts and war in the Middle East and North Africa, with irregular migration from further East continuing. Turkey assumed the role of guardian of the

Turkey has become a transit country for people entering Europe. In 2015, the route that passes from Turkey to Greece and then through the Balkan countries became the most used route for migrants escaping conflicts and war in the Middle East and North Africa, with irregular migration from further East continuing. Turkey assumed the role of guardian of the

Turkish PM on landmark Greek tripGreece-Turkey boundary study by Florida State University, College of Law

* ttps://archive.today/2012.12.22-030855/www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_s-political-relations-with-greece.en.mfa Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the relations with Greecebr>Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the relations with Turkey

{{DEFAULTSORT:Greece-Turkey relations

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

began in the 1830s following Greece's formation after its declaration of independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Modern relations began when Turkey declared its formation in 1923 following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

Greece and Turkey have a rivalry with a history of events that have been used to justify their nationalism. These events include the population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey ( el, Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, I Antallagí, ota, مبادله, Mübâdele, tr, Mübadele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at ...

, the Istanbul pogrom and Cypriot intercommunal violence

Several distinct periods of Cypriot intercommunal violence involving the two main ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, marked mid-20th century Cyprus. These included the Cyprus Emergency of 1955–59 during British rule, the ...

. Greek-Turkish feuding was not a significant factor in international relations from 1930 to 1955, and during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, domestic and bipolar

Bipolar may refer to:

Astronomy

* Bipolar nebula, a distinctive nebular formation

* Bipolar outflow, two continuous flows of gas from the poles of a star

Mathematics

* Bipolar coordinates, a two-dimensional orthogonal coordinate system

* Bipolar ...

politics limited competitive behaviour against each other. By the mid-1990s and later decades, the restraint on their rivalry was removed, and both nations had become each other's biggest security risk.

Control of the eastern Mediterranean

Eastern Mediterranean is a loose definition of the eastern approximate half, or third, of the Mediterranean Sea, often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea.

It typically embraces all of that sea's coastal zones, referring to communi ...

and Aegean seas remain the basis of the countries' rivalry. Following the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the UNCLOS treaty, the decolonisation of Cyprus, and the addition of the Dodecanese to Greece's territory have caused turbulence in the relationship. Several issues frequently affect their current relations, including territorial disputes over the sea and air, minority rights, and Turkey's relationship with the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

(EU) and its member states—especially Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

. Control of energy pipelines is also an increasing focus in their relations.

Diplomatic missions

The first official diplomatic contact between Greece and the Ottoman Empire occurred in 1830. Consular relations between the two countries were established in 1834. In 1853, a Greek embassy opened in 1853; this was discontinued during periods of crisis and eventually transferred to the new capital Ankara in 1923 when Turkey was formed. Turkey's missions in Greece include its embassy in Athens and consulates general inThessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

, Komotini

Komotini ( el, Κομοτηνή, tr, Gümülcine, bg, Комотини) is a city in the region of East Macedonia and Thrace, northeastern Greece. It is the capital of the Rhodope. It was the administrative centre of the Rhodope-Evros super-pr ...

and Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

. Greece's missions in Turkey include its embassy in Ankara, and consulates general in Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

, İzmir

İzmir ( , ; ), also spelled Izmir, is a metropolitan city in the western extremity of Anatolia, capital of the province of the same name. It is the third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara and the second largest urban agglo ...

and Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

.

History

Background

The histories of theByzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

factor into modern relations between Turkey and Greece. Some view the Byzantine Empire as the Roman Empire during the mediaeval era, the mediaeval expression of a Greek nation and a pre-modern nation state. Some academics say Turkey is not a successor state but the legal continuation of the Ottoman Empire as a republic.

The Greek presence in Asia Minor dates to the Late Bronze Age (1450 BC) or earlier. The Göktürks

The Göktürks, Celestial Turks or Blue Turks ( otk, 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣, Türük Bodun; ; ) were a nomadic confederation of Turkic peoples in medieval Inner Asia. The Göktürks, under the leadership of Bumin Qaghan (d. 552) and ...

of the First Turkic Khaganate

The First Turkic Khaganate, also referred to as the First Turkic Empire, the Turkic Khaganate or the Göktürk Khaganate, was a Turkic khaganate established by the Ashina clan of the Göktürks in medieval Inner Asia under the leadership of Bumin ...

was the first Turkic state to politically use the name Türk. The first contact with the Roman Byzantine Empire is believed to have occurred in 563 AD. in the 10th century, the Seljuk Turks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

rose to power. Later, Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

Anatolian beyliks

Anatolian beyliks ( tr, Anadolu beylikleri, Ottoman Turkish: ''Tavâif-i mülûk'', ''Beylik'' ) were small principalities (or petty kingdoms) in Anatolia governed by beys, the first of which were founded at the end of the 11th century. A secon ...

were established in former Byzantine lands and in the territory of the fragmenting Seljuk Sultanate

The Great Seljuk Empire, or the Seljuk Empire was a high medieval, culturally Turko-Persian, Sunni Muslim empire, founded and ruled by the Qïnïq branch of Oghuz Turks. It spanned a total area of from Anatolia and the Levant in the west to th ...

. One of those beyliks was the Ottoman dynasty, which became the Ottoman Empire. In 1453, the Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople, the capital city of the Byzantine Empire.

Modern Greece came under Ottoman rule in the 15th century. During the following centuries, there were sporadic but unsuccessful Greek uprisings against Ottoman rule. Greek nationalism started to appear in the 18th century. In March 1821. the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

began.

Greece and the Ottoman Empire relations: 1822–1923

Following the Greek War of Independence, Greece was formed as an independent state in 1830. Relations between Greece and the Ottoman Empire were shaped by the Eastern Question and the

Following the Greek War of Independence, Greece was formed as an independent state in 1830. Relations between Greece and the Ottoman Empire were shaped by the Eastern Question and the Megali Idea

The Megali Idea ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, Great Idea) is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek popul ...

. Conflicts between the two coutries include the Epirus Revolt of 1854

The 1854 revolt in Epirus was one of the most important of a series of Greek uprisings that occurred in the Ottoman Greece during that period. When the Crimean War (1854–1856) broke out, many Epirote Greeks, with tacit support from the Greek stat ...

during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

, the 1878 Greek Macedonian rebellion

The 1878 Macedonian rebellion ( el, Μακεδονική επανάσταση του 1878) was a Greek rebellion launched in opposition to the Treaty of San Stefano, according to which the bulk of Macedonia would be annexed to Bulgaria, and in fa ...

and the Epirus Revolt of 1878 during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 ( tr, 93 Harbi, lit=War of ’93, named for the year 1293 in the Islamic calendar; russian: Русско-турецкая война, Russko-turetskaya voyna, "Russian–Turkish war") was a conflict between th ...

. Wars between the Ottomans and the Greeks include the Greco-Turkish War (1897)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War ( el, Ατυχής πόλεμος, Atychis polemos), was a w ...

and the two Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defe ...

. By the end of the Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies r ...

due to the Treaty of Bucharest (1913)

The Treaty of Bucharest ( ro, Tratatul de la București; sr, Букурештански мир; bg, Букурещки договор; gr, Συνθήκη του Βουκουρεστίου) was concluded on 10 August 1913, by the delegates of ...

Greece grew by two-thirds; it went from and its population from 2,660,000 to 4,363,000. With the Allies victory in World War I, Greece was awarded sovereignty over Western Thrace

Western Thrace or West Thrace ( el, �υτικήΘράκη, '' ytikíThráki'' ; tr, Batı Trakya; bg, Западна/Беломорска Тракия, ''Zapadna/Belomorska Trakiya''), also known as Greek Thrace, is a Geography, geograp ...

in the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine

The Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine (french: Traité de Neuilly-sur-Seine) required Bulgaria to cede various territories, after Bulgaria had been one of the Central Powers defeated in World War I. The treaty was signed on 27 November 1919 at Neuilly ...

; and Eastern Thrace

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

* Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air ...

and the Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

area in the Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

. Greek gains were largely undone by the subsequent Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, ota, گرب جابهاسی, Garb Cebhesi) in Turkey, and the Asia Minor Campaign ( el, Μικρασιατική Εκστρατεία, Mikrasiatikí Ekstrateía) or the Asia Minor Catastrophe ( el, Μικ ...

.

Greece occupied Smyrna on 15 May 1919, while

Greece occupied Smyrna on 15 May 1919, while Mustafa Kemal Pasha

Mustafa ( ar, مصطفى

, Muṣṭafā) is one of the names of Prophet Muhammad, and the name means "chosen, selected, appointed, preferred", used as an Arabic given name and surname. Mustafa is a common name in the Muslim world.

Given name Mou ...

(later Atatürk), who was to become the leader of the Turkish opposition to the Treaty of Sèvres, landed in Samsun

Samsun, historically known as Sampsounta ( gr, Σαμψούντα) and Amisos (Ancient Greek: Αμισός), is a List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, city on the north coast of Turkey and is a major Black Sea port. In 2021, Samsun reco ...

on 19 May 1919, an action that is regarded as the beginning of the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

. Pasha united the protesting voices in Anatolia and began a nationalist movement to repel the Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

armies that had occupied the Ottoman Empire and establish new borders for a sovereign Turkish nation. The Turkish nation would be Western in civilization and would elevate Turkish culture that had faded under Arab culture; this included disassociating Islam from Arab culture and restricted it to the private sphere.

The Turkish Parliament in Ankara formally abolished the Sultanate and the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

ended all conflict and replaced previous treaties to constitute modern Turkey. The treaty provided for a population exchange between Greece and Turkey

The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey ( el, Ἡ Ἀνταλλαγή, I Antallagí, ota, مبادله, Mübâdele, tr, Mübadele) stemmed from the "Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations" signed at ...

.

The treaty also contained a declaration of amnesty for the perpetrators of crimes that were committed between 1914 and 1922, a period which was marked by many atrocities. The Greek genocide

The Greek genocide (, ''Genoktonia ton Ellinon''), which included the Pontic genocide, was the systematic killing of the Christians, Christian Ottoman Greeks, Ottoman Greek population of Anatolia which was carried out mainly during World War I ...

was the systematic killing of the Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

-Ottoman Greek

Ottoman Greeks ( el, Ρωμιοί; tr, Osmanlı Rumları) were ethnic Greeks who lived in the Ottoman Empire (1299–1922), much of which is in modern Turkey. Ottoman Greeks were Greek Orthodox Christians who belonged to the Rum Millet (''Millet ...

population of Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

which started before the World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and continued during the war and its aftermath (1914–1922).

Initial relations between Greece and Turkey: 1923–1945

Following the population exchange, Greece wanted to end hostilities but negotiations stalled because of the issue of valuations of the properties of the exchanged populations. Driven by

Following the population exchange, Greece wanted to end hostilities but negotiations stalled because of the issue of valuations of the properties of the exchanged populations. Driven by Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movem ...

in co-operation with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

, as well as İsmet İnönü

Mustafa İsmet İnönü (; 24 September 1884 – 25 December 1973) was a Turkish army officer and statesman of Kurdish descent, who served as the second President of Turkey from 11 November 1938 to 22 May 1950, and its Prime Minister three tim ...

's government, a series of treaties between Greece and Turkey were signed in 1930, in effect restoring Greek-Turkish relations and establishing a ''de facto'' alliance between the two countries. As part of these treaties, Greece and Turkey agreed the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

would be the final settlement of their respective borders, pledged they would not join opposing military or economic alliances, and to immediately stop their naval arms race.

The Balkan Pact

The Balkan Pact, or Balkan Entente, was a treaty signed by Greece, Romania, Turkey and Yugoslavia on 9 February 1934

of 1934 was signed, in which Greece and Turkey joined Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

and Romania in a treaty of mutual assistance, and settled outstanding issues. Venizelos nominated Atatürk for the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Chemi ...

in 1934.

Greece was a signatory to a 1936 agreement that gives Turkey control over the Bosporus and Dardanelles Straits, and regulates the transit of naval warships. The nations signed the 1938 Salonika Agreement The Salonika Agreement (also called the Thessaloniki Accord) was a treaty signed on 31 July 1938 between Bulgaria and the Balkan Entente (Greece, Romania, Turkey and Yugoslavia). The signatories were, for the former, Prime Minister Georgi Kyoseivano ...

which abandoned the demilitarised zones along the Turkish border with Greece that were a result of the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

.

In 1941, due to Turkey's neutrality during the Second World War, Britain lifted the blockade and allowed shipments of grain from Turkey to relieve the great famine in Athens during the Axis occupation. Using the vessel ''SS Kurtuluş

SS ''Kurtuluş'' was a Turkish cargo ship which became famous for her humanitarian role in carrying food aid during the Great Famine (Greece), famine Greece suffered under the Axis occupation of Greece, Axis occupation in World War II. She sank o ...

'', foodstuffs were collected by a nationwide campaign of Kızılay, the Turkish Red Crescent

Turkish Red Crescent (Turkish: ''Türk Kızılay'' (official) or ''Kızılay'' (for short)) is the largest humanitarian organization in Turkey and is part of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

The organization was founded i ...

, and the operation was funded by the American Greek War Relief Association and the Hellenic Union of Constantinopolitans.

During this period, the Greek minority that remained in Turkey faced discriminatory targeting. In 1941 in anticipation of the Second World War, in the Twenty Classes

The incident of the Twenty Classes ( Turkish: ''Yirmi Kur'a Nafıa Askerleri'', literally: "Soldiers for Public works by drawing of twenty lots", or ''Yirmi Kur'a İhtiyatlar Olayı'', Ayşe Hür"'Türk Schindleri' efsaneleri", ''Taraf'', December ...

, adult male Armenians, Greeks and Jews were conscripted into labour battalions. In 1942, Turkey imposed the Varlık Vergisi

The Varlık Vergisi (, "wealth tax" or "capital tax") was a tax mostly levied on non-Muslim citizens in Turkey in 1942, with the stated aim of raising funds for the country's defense in case of an eventual entry into World War II. The underlying re ...

, a special tax that heavily impacted the non-Muslim minorities of Turkey. Officially, the tax was devised to fill the state treasury that would have been needed if Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

or the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

invaded the country. The tax's main purpose, however, was to nationalize the Turkish economy by reducing minority populations' influence and control over the country's trade, finance, and industries.

Post World War II relations: 1945–1982

Following the power vacuum left by the ending of the Axis occupation after the war, the

Following the power vacuum left by the ending of the Axis occupation after the war, the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom ...

erupted as one of the first conflicts of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. It represented the first example of Cold War involvement on the part of the Allies in the internal affairs of a non-Allied country. Turkey was a focus for the Soviet Union due to foreign control of the straights; it was a central reason for the outbreak of the Cold War In 1950, both Greece and Turkey fought in the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, ending Turkey's diplomatic isolation and brought it an invitation to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO); in 1952, both countries joined NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

; and in 1953, Greece, Turkey and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

formed a new Balkan Pact for mutual defence against the Soviet Union.

think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-governmenta ...

Geopolitical Futures

George Friedman ( hu, Friedman György, born February 1, 1949) is a Hungarian-born U.S. geopolitical forecaster, author, and strategist on international affairs. He is the founder and chairman of ''Geopolitical Futures'', an online publication t ...

, three events contributed to the deterioration of post-1945 bilateral relations:

*After the defeat of Italy in the Second World War, the long-standing issue of sovereignty over the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

archipelago, which had been a sore point since the Venizelos–Tittoni agreement

The Venizelos–Tittoni agreement was a secret non-binding agreement between the Prime Minister of Greece, Eleftherios Venizelos, and the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tommaso Tittoni, in July 1919, during the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, P ...

between Greece and Italy, was resolved to Greece's favour in 1946, upsetting Turkey because it changed the balance of power. Turkey renounced claims to the Dodecanese in the Treaty of Lausanne but future administrations wanted them for security reasons, and possibly due to the Cyprus issue.

*After the decolonisation of Cyprus, conflict between Greeks and Turks broke out on the island. In the 1950s, the pursuit of ''enosis

''Enosis'' ( el, Ένωσις, , "union") is the movement of various Greek communities that live outside Greece for incorporation of the regions that they inhabit into the Greek state. The idea is related to the Megali Idea, an irredentist conc ...

'' became a part of Greece's national policy. Taksim became the slogan by some Turkish Cypriots in reaction to ''enosis''. Tensions between Greece and Turkey increased, and the ambivalence towards Cyprus by the Greek government of George Papandreou

George Andreas Papandreou ( el, Γεώργιος Ανδρέας Παπανδρέου, , shortened to ''Giorgos'' () to distinguish him from his grandfather; born 16 June 1952) is a Greek politician who served as Prime Minister of Greece from ...

led to the Greek military coup. In 1974, the Greek government staged a coup against the Cypriot president and Archbishop Makarios

Makarios III ( el, Μακάριος Γ΄; born Michael Christodoulou Mouskos) (Greek: Μιχαήλ Χριστοδούλου Μούσκος) (13 August 1913 – 3 August 1977) was a Cypriot politician, archbishop and primate who served as ...

by invading Cyprus and establishing a Greece-controlled Cyprus government. Soon after, Turkey—using its guarantor status arising from the trilateral accords of the 1959–1960 Zürich and London Agreement

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Zürich ...

— invaded Cyprus. The Turkish Federated State of Cyprus

The Turkish Federated State of Cyprus ( tr, ) was a state on the region of Northern Cyprus declared in 1975 and existing until 1983, that was not recognised by the international community. It was succeeded by the Turkish Republic of Northern C ...

was declared one year later.

*Starting in 1958 and expanded in 1982 for the issue of territorial waters, the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) replaced the older concept of freedom of the seas

Freedom of the seas ( la, mare liberum, lit. "free sea") is a principle in the law of the sea. It stresses freedom to navigate the oceans. It also disapproves of war fought in water. The freedom is to be breached only in a necessary inter ...

, which dated from the 17th century. According to this concept, national rights were limited to a specified belt of water extending from a nation's coastlines, usually —known as the three-mile limit

The three-mile limit refers to a traditional and now largely obsolete conception of the international law of the seas which defined a country's territorial waters, for the purposes of trade regulation and exclusivity, as extending as far as the r ...

). By 1967, only 30 nations still used the old three-nautical-mile convention. It was ratified by Greece in 1972 but Turkey has not ratified it, asking for a bilateral solution since 1974 which uses the mid-line of the Aegean instead

Adnan Menderes

Adnan Menderes (; 1899 – 17 September 1961) was a Turkish politician who served as Prime Minister of Turkey between 1950 and 1960. He was one of the founders of the Democrat Party (DP) in 1946, the fourth legal opposition party of Turkey. He ...

government is believed to have orchestrated the Istanbul pogrom, which targeted the city's substantial Greek ethnic minority and other minorities. In September 1955, a bomb exploded close to the Turkish consulate in Greece's second-largest city Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

, also damaging Atatürk Museum, site of Atatürk's birthplace, breaking some windows but causing little other damage. In retaliation, in Istanbul, thousands of shops, houses, churches and graves belonging to members of the ethnic Greek minority were destroyed within a few hours, over 12 people were killed and many more injured. The ongoing struggle between Turkey and Greece over control of Cyprus, and Cypriot intercommunal violence

Several distinct periods of Cypriot intercommunal violence involving the two main ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, marked mid-20th century Cyprus. These included the Cyprus Emergency of 1955–59 during British rule, the ...

, were concurrent with the pogrom. Pressure over the resulting London Conference to discuss Cyprus, and to direct attention away from the domestic political problems were the likely motivation of the Turkish Menderes government.

In 1964, Turkish prime minister İsmet İnönü

Mustafa İsmet İnönü (; 24 September 1884 – 25 December 1973) was a Turkish army officer and statesman of Kurdish descent, who served as the second President of Turkey from 11 November 1938 to 22 May 1950, and its Prime Minister three tim ...

renounced the Greco-Turkish Treaty of Friendship of 1930 and took actions against the Greek minority. An estimated 50,000 Greeks were expelled. A 1971 Turkish law nationalized religious high schools and closed the Halki seminary

The Halki seminary, formally the Theological School of Halki ( el, Θεολογική Σχολή Χάλκης and tr, Ortodoks Ruhban Okulu), was founded on 1 October 1844 on the island of Halki ( Turkish: Heybeliada), the second-largest of the ...

on Istanbul's Heybeli Island, an issue that affects 21st-century relations.

Contemporary history and issues

Military and diplomatic tensions

Towards the end of the 20th century, there were several high profile incidents between the countries. In 1986 by the border at the Evros River, a Greek soldier was shot dead, causing outrage. In 1987, a Turkish survey ship ''Simsik'' nearly started a war. In 1995, caused a military crisis erupted over an uninhabited island calledImia

Imia ( el, Ίμια) is a pair of small uninhabited islets in the Aegean Sea, situated between the Greek island chain of the Dodecanese and the southwestern mainland coast of Turkey. They are known in Turkey as Kardak.

Imia was the object of a ...

, over which both countries claim sovereignty.

Lesser incidents often occur when both sides exchange fire. This creates volatility when relations are tense and risks the start of a war.

In the 1990s, Greece pursued a policy of encircling Turkey. Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, both Greece and Turkey viewed each other with suspicion as they developed relations with the new countries. In 1995, however, this fear materialised. Greece formed a defence-co-operation agreement with Syria, and between 1995 and 1998 established good relations with Turkey's other neighbours Iran and Armenia. In reaction, Turkey spoke with Israel in 1996, which caused uproar in Arab countries.

Some view the conflict between the nations as a fight for control control over the Aegean Sea and the eastern Mediterranean.

Positive relations

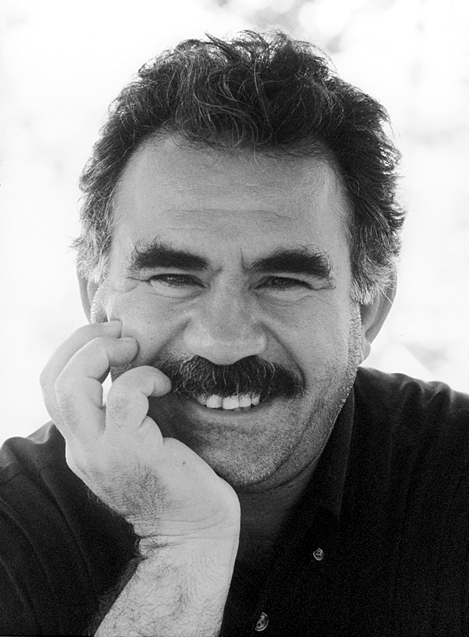

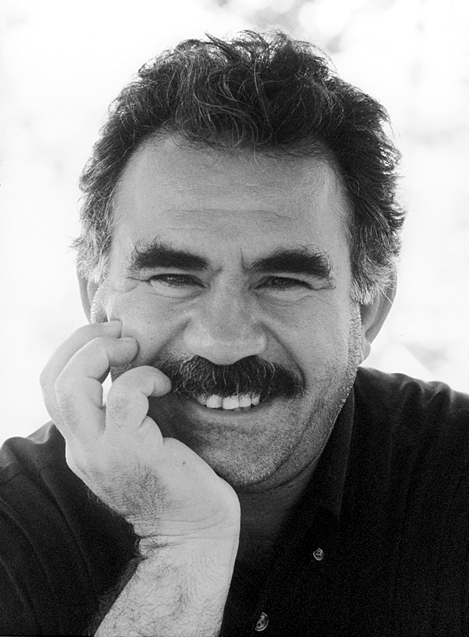

In 1995, relations began to change with the Greek election of

In 1995, relations began to change with the Greek election of Kostas Simitis

Konstantinos G. Simitis ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Γ. Σημίτης; born 23 June 1936), usually referred to as Costas Simitis or Kostas Simitis (Κώστας Σημίτης), is a Greek politician who served as Prime Minister of Greece ...

who redefined priorities but it wasn't until the meeting of the foreign ministers the following years that this was noticed. In 1998, the capture of the Kurdish separatist Abdullah Öcalan

Abdullah Öcalan ( ; ; born 4 April 1949), also known as Apo (short for Abdullah in Turkish and Kurdish for "uncle"), is a political prisoner and founding member of the militant Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK).

Öcalan was based in Syria from ...

– on the way from the Greek embassy in Kenya – and the related fallout led to the Greek foreign minister resigning, whose replacement was with a strong supporter for discussions with Turkey. The 1999 İzmit earthquake

On the 17th of August, 1999 at 3:01 AM local time, a catastrophic magnitude 7.6 earthquake struck the Kocaeli Province of Turkey, causing monumental damage and 17,127–18,373 deaths. Named for the quakes proximity to the northeastern city of Izm ...

followed by the 1999 Athens earthquake

The 1999 Athens earthquake occurred on September 7 at near Mount Parnitha in Greece with a moment magnitude of 6.0 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (''Violent''). The proximity to the Athens metropolitan area resulted in widespread stru ...

led to an outpouring of goodwill and what has been called earthquake diplomacy that aided in a change of relations.

In the years that followed, relations improved. They included agreements on fighting organised crime, reducing military spending, preventing illegal immigration, and clearing land mines on the border. Additionally, Greece lifted its opposition to Turkey's accession to the EU. According to Dr R. Craig Nation in a report commissioned by a US military think tank, there was a lot of progress but ultimately not on the issues that mattered.

The Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean conflicts

The conflict between Turkey and Greece is largely over whether the Greek islands are allowed an exclusive economic zone, the basis of claiming rights over the sea. Some claim fear of sovereignty loss is what is driving this conflict. In recent years, the Blue Homeland policy of Turkey has emerged. Islands and islets Iying within of the coast were included as part of the respective state under the Treaty of Lausanne. Greece controversially extended this limit to in 1936, which Turkey did not dispute due to good relations and reciprocated in 1964. The conference for the UN sea treatyUNCLOS

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an international agreement that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. , 167 c ...

defined territorial waters in 1982 and came into force in 1994.

There are 168 nations as signatories of the treaty, including Greece but not Turkey. Turkey disputes that Greece can claim 12 miles off the coast of their islands, which the sea treaty permits, implying only the mainland has this right as otherwise it will give Greece dominant control of the Aegean. Turkey has made a claim for the economic zone by splitting the Aegean Sea in the middle. The EU requires the sea treaty's membership as a pre-condition.

There has been an extension of the conflict with other nations in the Mediterranean. In 2019 and 2022, Turkey made deals with Libya to extend its economic rights over the sea, which were countered with Greece and Egypt.

The Cyprus dispute created a subsequent military build up. The dispute escalated with Greece's coup in Cyprus, which led to the Turkish invasion of Cyprus. In 1974, Greece reacted with the militarisation of the Greek islands off the coast of Turkey, the legality of which is challenged by Turkey. In 1975, Turkey created Izmir army base. Military buildups in 2022 have continued.

Cyprus and the EU

Greece has been a member of the EU since 1981. Cyprus joined in 2004. Turkey submitted its application to join in 1987 and became a full candidate in 1999.

Until 1999, Greece concentrated its diplomatic efforts on barring Turkey's admission to the EU. Concerns about Turkey like its human rights record and Greece's veto ultimately had Turkey side-lined by the EU. Domestically, this contributed to the shift away from Turkey's founding secular doctrine ''

Greece has been a member of the EU since 1981. Cyprus joined in 2004. Turkey submitted its application to join in 1987 and became a full candidate in 1999.

Until 1999, Greece concentrated its diplomatic efforts on barring Turkey's admission to the EU. Concerns about Turkey like its human rights record and Greece's veto ultimately had Turkey side-lined by the EU. Domestically, this contributed to the shift away from Turkey's founding secular doctrine ''Kemalism

Kemalism ( tr, Kemalizm, also archaically ''Kamâlizm''), also known as Atatürkism ( tr, Atatürkçülük, Atatürkçü düşünce), or The Six Arrows ( tr, Altı Ok), is the founding official ideology of the Republic of Turkey.Eric J. Zurche ...

'' and the rise of political Islam. There would be a change to the ''Kemalism'' amnesia of the Ottoman Empire's past, to be a source of pride and identity instead. It also evolved to an alternate identity of European orientation, as a regional center in the emerging Eurasian political formation.

The 1990s saw EU accession friction of Cyprus which was parallel to military tension. In 1994, Greece and Cyprus agreed on a security doctrine that would mean any Turkish attempt on Cyprus would cause war for Greece. In 1997 Cyprus purchased two Soviet-era missile systems, the S-300s, resulting in a Turkish uproar. Negotiations never settled the division on the island in the 1990s because of the non-negotiable by the Turkish side to recognise North Cyprus as an independent state, an issue that remains as of 2022. When Cyprus joined the EU in 2002, the negotiation took a different flare by virtue of Cyprus's veto on Turkish accession.

Turkey's migrant crisis

Turkey's migrant crisis, sometimes referred to as Turkey's refugee crisis, was a period during the 2010s characterized by high numbers of people migrating to Turkey to take up residence in the country. Turkey received the highest number of reg ...

has also had a big impact on its relationship with the EU. The enforcement of the arms embargo against Libya brought other EU members into conflict with Turkey on Operation Irini

The European Union Naval Force Mediterranean Operation IRINI (EUNAVFOR MED IRINI) was launched on 31 March 2020 with the primary mission to enforce the United Nations arms embargo to Libya due to the Second Libyan Civil War. Operation IRINI is a ...

. The gas drilling on disputed territory with Greece with the RV ''MTA Oruç Reis'' led to EU sanctions

Energy pipelines

The 2010 discovery of gas deposits in the eastern Mediterranean first by Israel and then Egypt, has created new energy to fan the disputes. It is estimated 5% of the worlds known natural gas reserves are in the eastern Mediterranean. The historical security issues of the Aegean and Cyprus are now a focal point to resolving Europe's energy needs. For example, the 2016 Turkey-Israel reconciliation led to Greece torpedoing the 2017 Cyprus UN talks due to their relationship's risk for developing a gas pipeline. In 2019, the east Mediterranean gas forum was created, including seven countries but excluding Turkey.

The region is considered the end-point for east–west pipelines. In 2007, the countries inaugurated the Greek-Turkish natural gas pipeline giving Caspian gas its first direct Western outlet. The Caspian Sea is one of the oldest oil-producing regions: it's estimated to have 48 billion barrels of oil in proven and probable reserves. Its estimated it has 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The opening up of these fields is recent after more than 20 years of negotiation following the 2018 A

The 2010 discovery of gas deposits in the eastern Mediterranean first by Israel and then Egypt, has created new energy to fan the disputes. It is estimated 5% of the worlds known natural gas reserves are in the eastern Mediterranean. The historical security issues of the Aegean and Cyprus are now a focal point to resolving Europe's energy needs. For example, the 2016 Turkey-Israel reconciliation led to Greece torpedoing the 2017 Cyprus UN talks due to their relationship's risk for developing a gas pipeline. In 2019, the east Mediterranean gas forum was created, including seven countries but excluding Turkey.

The region is considered the end-point for east–west pipelines. In 2007, the countries inaugurated the Greek-Turkish natural gas pipeline giving Caspian gas its first direct Western outlet. The Caspian Sea is one of the oldest oil-producing regions: it's estimated to have 48 billion barrels of oil in proven and probable reserves. Its estimated it has 292 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The opening up of these fields is recent after more than 20 years of negotiation following the 2018 A Convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea

The Convention on the legal status of the Caspian Sea is a treaty signed in Aktau, Kazakhstan, on 12 August 2018 by the presidents of Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Iran and Turkmenistan.

History

A dispute began after the dissolution of the S ...

. Outside of the Caspian Sea nations, there are other suppliers that wish to leverage the geographical positioning of the nations. Most recently, in May 2022, Greece signed a deal with Turkey's rival the UAE for the distribution of its liquefied natural gas

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is natural gas (predominantly methane, CH4, with some mixture of ethane, C2H6) that has been cooled down to liquid form for ease and safety of non-pressurized storage or transport. It takes up about 1/600th the volu ...

.

Minority rights

Thetreaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conflic ...

provided for the protection of the Greek Orthodox Christian minority in Turkey and the Muslim minority in Greece

The Muslim minority of Greece is the only explicitly recognized minority in Greece. It numbered 97,605 (0.91% of the population) according to the 1991 census, and unofficial estimates ranged up to 140,000 people or 1.24% of the total population, a ...

.

Minorities in both countries since have been affected by the state of relations of the nations. They are used as a point of leverage, using the principle of reciprocity. For example, Turkey would put pressure on the Greek minority in Turkey when the Cyprus issue escalated in the 1960s. Turkey put the election of Mufti

A Mufti (; ar, مفتي) is an Islamic jurist qualified to issue a nonbinding opinion ('' fatwa'') on a point of Islamic law (''sharia''). The act of issuing fatwas is called ''iftāʾ''. Muftis and their ''fatwas'' played an important rol ...

s by the Muslim Turkish minority in Greece as a precondition for opening the Halki Seminary

The Halki seminary, formally the Theological School of Halki ( el, Θεολογική Σχολή Χάλκης and tr, Ortodoks Ruhban Okulu), was founded on 1 October 1844 on the island of Halki ( Turkish: Heybeliada), the second-largest of the ...

which was closed in 1971. Greece in 1972 as a reaction, closed the Turkish school in Rhodes. Turkey in recent years has used its cultural heritage, such as the Sumela Monastery

Sumela Monastery ( el, Μονή Παναγίας Σουμελά, ''Moní Panagías Soumelá''; tr, Sümela Manastırı, lzz, სუმელა) is a Greek Orthodox Church, Greek Orthodox monastery dedicated to the Theotokos located at ''K ...

, in order to achieve specific political ends.

Examples of minority mistreatment include:

* During World War II, the nationalisation of industry with the

Examples of minority mistreatment include:

* During World War II, the nationalisation of industry with the Varlık Vergisi

The Varlık Vergisi (, "wealth tax" or "capital tax") was a tax mostly levied on non-Muslim citizens in Turkey in 1942, with the stated aim of raising funds for the country's defense in case of an eventual entry into World War II. The underlying re ...

that targeted minorities

* The scapegoating of Greeks due to Turkey's economic problems that resulted in the Istanbul pogrom

* The Greek junta deporting Turkish citizens on the Dodecanese in 1967

* Article 19 of the Nationality Code established in 1955 two classes of Greek citizenship, whereby "non-Greek descent" lost their citizenship if they left the country. By the time of its abolition in 1998, 60,000 people has lost their citizenship and the abolition had no retroactive effect.

In recent years, the election of Muftis in Greece and the reopening of the Halki Seminary in Turkey have been most prominent. Issues around political authority and pre-conditions contribute to the stalemate.

Former Greek prime minister George Papandreou has said the respective nations would benefit if they treated the minorities as citizens not foreigners.

Migrants

Turkey has become a transit country for people entering Europe. In 2015, the route that passes from Turkey to Greece and then through the Balkan countries became the most used route for migrants escaping conflicts and war in the Middle East and North Africa, with irregular migration from further East continuing. Turkey assumed the role of guardian of the

Turkey has become a transit country for people entering Europe. In 2015, the route that passes from Turkey to Greece and then through the Balkan countries became the most used route for migrants escaping conflicts and war in the Middle East and North Africa, with irregular migration from further East continuing. Turkey assumed the role of guardian of the Schengen Area

The Schengen Area ( , ) is an area comprising 27 European countries that have officially abolished all passport and all other types of border control at their mutual borders. Being an element within the wider area of freedom, security and j ...

, protecting it from irregular migration. This, combined with the migrant crisis

Migrant crisis is the intense difficulty, trouble, or danger situation in the receiving state (destination country) due to the movements of large groups of immigrants (displaced people, refugee or asylum seeker) escaping from the conditions (natura ...

– has resulted in it being a key issue between Turkey and the EU. People moving across the border of both nations are a common sight and frequent cause of incidents.

In 2016, there was an EU-Turkey deal on migrant crisis. There was some success with the four-year agreement extended to 2022, but there have been several incidents and in 2019 the Greek government warned that a new migrant crisis similar to the previous one would repeat.

Turkish insurgents and asylum seekers

During the 2010 trial for an alleged plot to stage a military coup dating back to 2003, named Sledgehammer, the conspirators were accused of planning attacks on mosques, triggering a conflict with Greece by shooting down one of Turkey's own warplanes and then accusing Greeks of this and planting bombs in Istanbul to pave the way for a military takeover. Greece over the years has arrested on many occasions members of theDHKP-C

The Revolutionary People's Liberation Party/Front ( tr, Devrimci Halk Kurtuluş Partisi-Cephesi or DHKP-C) is a far-left Marxist–Leninist Communist party in Turkey. It was founded in 1978 as Revolutionary Left (Turkish: or ), and has been inv ...

who planned attacks in Turkey. Turkey has accused Greece of supporting terrorists such as the DHKP-C.

Turkey has seen a slide to authoritarianism resulting in Turkish refugees becoming more common, like politician Leyla Birlik

Leyla Birlik (born 3 March 1974, Derik, Mardin) is a Kurdish politician of the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) and a former member of the Gran National Assembly of Turkey. She is currently a member of the executive council and the head of the W ...

accused of insulting the president. This is especially since the failed 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt

On 15 July 2016, a faction within the Turkish Armed Forces, organized as the Peace at Home Council, attempted a coup d'état against state institutions, including the government and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. They attempted to seize cont ...

, where 995 people applied for asylum (including military personnel

Military personnel are members of the state's armed forces. Their roles, pay, and obligations differ according to their military branch (army, navy, marines, air force, space force, and coast guard), rank (officer, non-commissioned officer, or e ...

) immediately after More than 1,800 Turkish citizens requested asylum in Greece in 2017, including those who plotted the assassination Sometimes, this causes tensions between the nations in other areas.

Timeline

See also

*History of Greece

The history of Greece encompasses the history of the territory of the modern nation-state of Greece as well as that of the Greek people and the areas they inhabited and ruled historically. The scope of Greek habitation and rule has varied thro ...

*History of Turkey

:''See History of the Republic of Turkey for the history of the modern state.''

The history of Turkey, understood as the history of the region now forming the territory of the Republic of Turkey, includes the history of both Anatolia (the Asia ...

*History of Cyprus

Human habitation of Cyprus dates back to the Paleolithic era. Cyprus's geographic position has caused Cyprus to be influenced by differing Eastern Mediterranean civilisations over the millennia.

Periods of Cyprus's history from 1050 BC have be ...

*Hellenoturkism

Hellenoturkism ( el, Ελληνοτουρκισμός, Ellinotourkismós; tr, Helenotürkizm) is a political concept that encompasses two things: a fact of civilization (i.e. the co-habitation and interdependence, since the 11th century A.D.) of t ...

*Foreign relations of Greece

As one of the oldest Euro-Atlantic member states in the region of Southeast Europe, Greece enjoys a prominent geopolitical role as a middle power, due to its political and geographical proximity to Europe, Asia, the Middle East, Africa, the Amer ...

, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

and Northern Cyprus

Northern Cyprus ( tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs), officially the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC; tr, Kuzey Kıbrıs Türk Cumhuriyeti, ''KKTC''), is a ''de facto'' state that comprises the northeastern portion of the Geography of Cyprus, isl ...

*European Union–Turkey relations

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe a ...

*Greece–Turkey border

The Greece–Turkey border ( gr, Σύνορα Ελλάδας–Τουρκίας, translit=Sýnora Elládas–Tourkías, tr, Türkiye–Yunanistan sınırı) is around long, and separates Western Thrace in Greece from East Thrace in Turkey.

...

*Intermediate Region

The Intermediate Region is an established geopolitics, geopolitical model set forth in the 1970s by the Greece, Greek historian Dimitri Kitsikis, professor at the University of Ottawa in Canada. According to this model, the Eurasian continent is c ...

*Greeks in Turkey

) constitute a small population of Greek and Greek-speaking Eastern Orthodox Christians who mostly live in Istanbul, as well as on the two islands of the western entrance to the Dardanelles: Imbros and Tenedos ( tr, Gökçeada and ''Bozcaada'').

Th ...

* Greeks in the Middle East

*Turks in Greece

Turks in Greece may refer to:

* Turks of Crete

* Turks of the Dodecanese

* Turks of Western Thrace

See also

* Muslim minority of Greece

{{Set index article

Ethnic groups in Greece

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially th ...

*Turks in Europe

The Turks in Europe (sometimes called Euro-Turks; tr, Avrupa'daki Türkler or ''Avrupa Türkleri'') refers to ethnic Turks living in Europe. Generally, the Euro-Turks refers to the large Turkish diasporas living in Central and Western Europe a ...

* Greece–Turkey football rivalry

Notes

References

Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

Turkish PM on landmark Greek trip

* ttps://archive.today/2012.12.22-030855/www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_s-political-relations-with-greece.en.mfa Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the relations with Greecebr>Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the relations with Turkey

{{DEFAULTSORT:Greece-Turkey relations

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

Bilateral relations of Turkey

Relations of colonizer and former colony