The Oregon Trail was a eastŌĆōwest, large-wheeled wagon route and

emigrant trail

In the history of the American frontier, overland trails were built by pioneers throughout the 19th century and especially between 1829 and 1870 as an alternative to sea and railroad transport. These immigrants began to settle much of North Ame ...

in the United States that connected the

Missouri River to valleys in

Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what is now the state of

Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

and nearly all of what are now the states of

Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

and

Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

. The western half of the trail spanned most of the current states of

Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the CanadaŌĆōUnited States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

and Oregon.

The Oregon Trail was laid by

fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

rs and trappers from about 1811 to 1840 and was only passable on foot or on horseback. By 1836, when the first migrant

wagon train

''Wagon Train'' is an American Western series that aired 8 seasons: first on the NBC television network (1957ŌĆō1962), and then on ABC (1962ŌĆō1965). ''Wagon Train'' debuted on September 18, 1957, and became number one in the Nielsen ratings. It ...

was organized in

Independence, Missouri

Independence is the fifth-largest city in Missouri and the county seat of Jackson County, Missouri, Jackson County. Independence is a satellite city of Kansas City, Missouri, and is the largest suburb on the Missouri side of the Kansas City metro ...

, a wagon trail had been cleared to

Fort Hall

Fort Hall was a fort in the western United States that was built in 1834 as a fur trading post by Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth. It was located on the Snake River in the eastern Oregon Country, now part of present-day Bannock County in southeastern Ida ...

, Idaho. Wagon trails were cleared increasingly farther west and eventually reached all the way to the

Willamette Valley

The Willamette Valley ( ) is a long valley in Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. The Willamette River flows the entire length of the valley and is surrounded by mountains on three sides: the Cascade Range to the east, ...

in Oregon, at which point what came to be called the Oregon Trail was complete, even as almost annual improvements were made in the form of bridges, cutoffs, ferries, and roads, which made the trip faster and safer. From various starting points in Iowa, Missouri, or

Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebraska ...

, the routes converged along the lower

Platte River Valley

The Platte River () is a major river in the Nebraska, State of Nebraska. It is about long; measured to its farthest source via its tributary, the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, whi ...

near

Fort Kearny

Fort Kearny was a historic outpost of the United States Army founded in 1848 in the western U.S. during the middle and late 19th century. The fort was named after Col. and later General Stephen Watts Kearny. The outpost was located along the Ore ...

, Nebraska Territory, and led to fertile farmlands west of the

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

.

From the early to mid-1830s (and particularly through the years 1846ŌĆō1869) the Oregon Trail and its many offshoots were used by about 400,000 settlers, farmers, miners, ranchers, and business owners and their families. The eastern half of the trail was also used by travelers on the

California Trail

The California Trail was an emigrant trail of about across the western half of the North American continent from Missouri River towns to what is now the state of California. After it was established, the first half of the California Trail f ...

(from 1843),

Mormon Trail

The Mormon Trail is the long route from Illinois to Utah that members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traveled for 3 months. Today, the Mormon Trail is a part of the United States National Trails System, known as the Mormon ...

(from 1847), and

Bozeman Trail

The Bozeman Trail was an overland route in the western United States, connecting the gold rush territory of southern Montana to the Oregon Trail in eastern Wyoming. Its most important period was from 1863ŌĆō68. Despite the fact that the major pa ...

(from 1863) before turning off to their separate destinations. Use of the trail declined after the

first transcontinental railroad

North America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the " Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line constructed between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail netwo ...

was completed in 1869, making the trip west substantially faster, cheaper, and safer. Today, modern highways, such as

Interstate 80

Interstate 80 (I-80) is an eastŌĆōwest transcontinental freeway that crosses the United States from downtown San Francisco, California, to Teaneck, New Jersey, in the New York metropolitan area. The highway was designated in 1956 as one o ...

and

Interstate 84, follow parts of the same course westward and pass through towns originally established to serve those using the Oregon Trail.

History

Lewis and Clark Expedition

In 1803, President

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 ŌĆō July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

issued the following instructions to

Meriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis (August 18, 1774 ŌĆō October 11, 1809) was an American explorer, soldier, politician, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, with ...

: "The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream of it, as, by its course & communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado and/or other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce." Although Lewis and

William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 ŌĆō September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

found a path to the Pacific Ocean, it was not until 1859 that a direct and practicable route, the

Mullan Road

Mullan Road was the first wagon road to cross the Rocky Mountains to the Inland of the Pacific Northwest. It was built by U.S. Army troops under the command of Lt. John Mullan, between the spring of 1859 and summer 1860. It led from Fort Benton, ...

, connected the Missouri River to the

Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''NchŌĆÖi-W├Āna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

.

The first land route across the present-day continental United States was mapped by the Lewis and Clark Expedition between 1804 and 1806. Lewis and Clark initially believed they had found a practical overland route to the west coast; however, the two passes they found going through the

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

,

Lemhi Pass

Lemhi Pass is a high mountain pass in the Beaverhead Mountains, part of the Bitterroot Range in the Rocky Mountains and within Salmon-Challis National Forest. The pass lies on the Montana-Idaho border on the continental divide, at an elevation o ...

and

Lolo Pass, turned out to be much too difficult for

prairie schooner wagons to pass through without considerable road work. On the return trip in 1806, they traveled from the Columbia River to the

Snake River

The Snake River is a major river of the greater Pacific Northwest region in the United States. At long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, in turn, the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. The Snake ...

and the

Clearwater River over Lolo Pass again. They then traveled overland up the

Blackfoot River and crossed the

Continental Divide at Lewis and Clark Pass, as it would become known, and on to the head of the Missouri River. This was ultimately a shorter and faster route than the one they followed west. This route had the disadvantages of being much too rough for wagons and controlled by the

Blackfoot

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'' or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ߢ╣ßɤßƦßɦßÆŻßæ», meaning "the people" or " Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Bla ...

tribes. Even though Lewis and Clark had only traveled a narrow portion of the upper Missouri River drainage and part of the Columbia River drainage, these were considered the two major rivers draining most of the Rocky Mountains, and the expedition confirmed that there was no "easy" route through the northern Rocky Mountains as Jefferson had hoped. Nonetheless, this famous expedition had mapped both the eastern and western river-valleys (Platte and Snake Rivers) that bookend the route of the Oregon Trail (and other

emigrant trail

In the history of the American frontier, overland trails were built by pioneers throughout the 19th century and especially between 1829 and 1870 as an alternative to sea and railroad transport. These immigrants began to settle much of North Ame ...

s) across the continental dividethey just had not located the

South Pass or some of the interconnecting valleys later used in the high country. They did show the way for the

mountain men

A mountain man is an explorer who lives in the wilderness. Mountain men were most common in the North American Rocky Mountains from about 1810 through to the 1880s (with a peak population in the early 1840s). They were instrumental in opening up ...

, who within a decade would find a better way across, even if it was not to be an easy way.

Pacific Fur Company

Founded by

John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 ŌĆō March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by smuggling opium into China, and ...

as a subsidiary of his

American Fur Company

The American Fur Company (AFC) was founded in 1808, by John Jacob Astor, a German immigrant to the United States. During the 18th century, furs had become a major commodity in Europe, and North America became a major supplier. Several British co ...

(AFC) in 1810, the

Pacific Fur Company

The Pacific Fur Company (PFC) was an American fur trade venture wholly owned and funded by John Jacob Astor that functioned from 1810 to 1813. It was based in the Pacific Northwest, an area contested over the decades between the United Kingdom o ...

(PFC) operated in the

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

in the ongoing

North American fur trade

The North American fur trade is the commercial trade in furs in North America. Various Indigenous peoples of the Americas traded furs with other tribes during the pre-Columbian era. Europeans started their participation in the North American fur ...

. Two movements of PFC employees were planned by Astor, one detachment to be sent to the Columbia River by the ''

Tonquin'' and the other overland under an expedition led by

Wilson Price Hunt

Wilson Price Hunt (March 20, 1783 ŌĆō April 13, 1842) was an early pioneer and explorer of the Oregon Country in the Pacific Northwest of North America. Employed as an agent in the fur trade under John Jacob Astor, Hunt organized and led the gre ...

. Hunt and his party were to find possible supply routes and trapping territories for further

fur trading

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the most ...

posts. Upon arriving at the river in March 1811, the ''Tonquin'' crew began construction of what became

Fort Astoria

Fort Astoria (also named Fort George) was the primary fur trading post of John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company (PFC). A maritime contingent of PFC staff was sent on board the '' Tonquin'', while another party traveled overland from St. Louis. ...

. The ship left supplies and men to continue work on the station and ventured north up the coast to

Clayoquot Sound

, image = Clayoquot Sound - Near Tofino - Vancouver Island BC - Canada - 08.jpg

, image_size = 260px

, alt =

, caption =

, image_bathymetry = Vancouver clayoquot sound de.png

, alt_bathyme ...

for a trading expedition. While anchored there,

Jonathan Thorn

Jonathan Thorn (8 January 1779 – 15 June 1811) was a career officer of the United States Navy in the early 19th century.

Early life and Naval career

Born on 8 January 1779 at Schenectady, New York, during the Revolutionary War, Thorn was ...

insulted an elder

Tla-o-qui-aht who was previously elected by the natives to negotiate a mutually satisfactory price for animal pelts. Soon after, the vessel was attacked and overwhelmed by the indigenous Clayoquot, killing many of the crew. Its

Quinault Quinault may refer to:

* Quinault people, an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast

**Quinault Indian Nation, a federally recognized tribe

**Quinault language, their language

People

* Quinault family of actors, including

* Jean-Baptis ...

interpreter survived, and later told the PFC management at Fort Astoria of the destruction. The next day, the ship was blown up by surviving crew members.

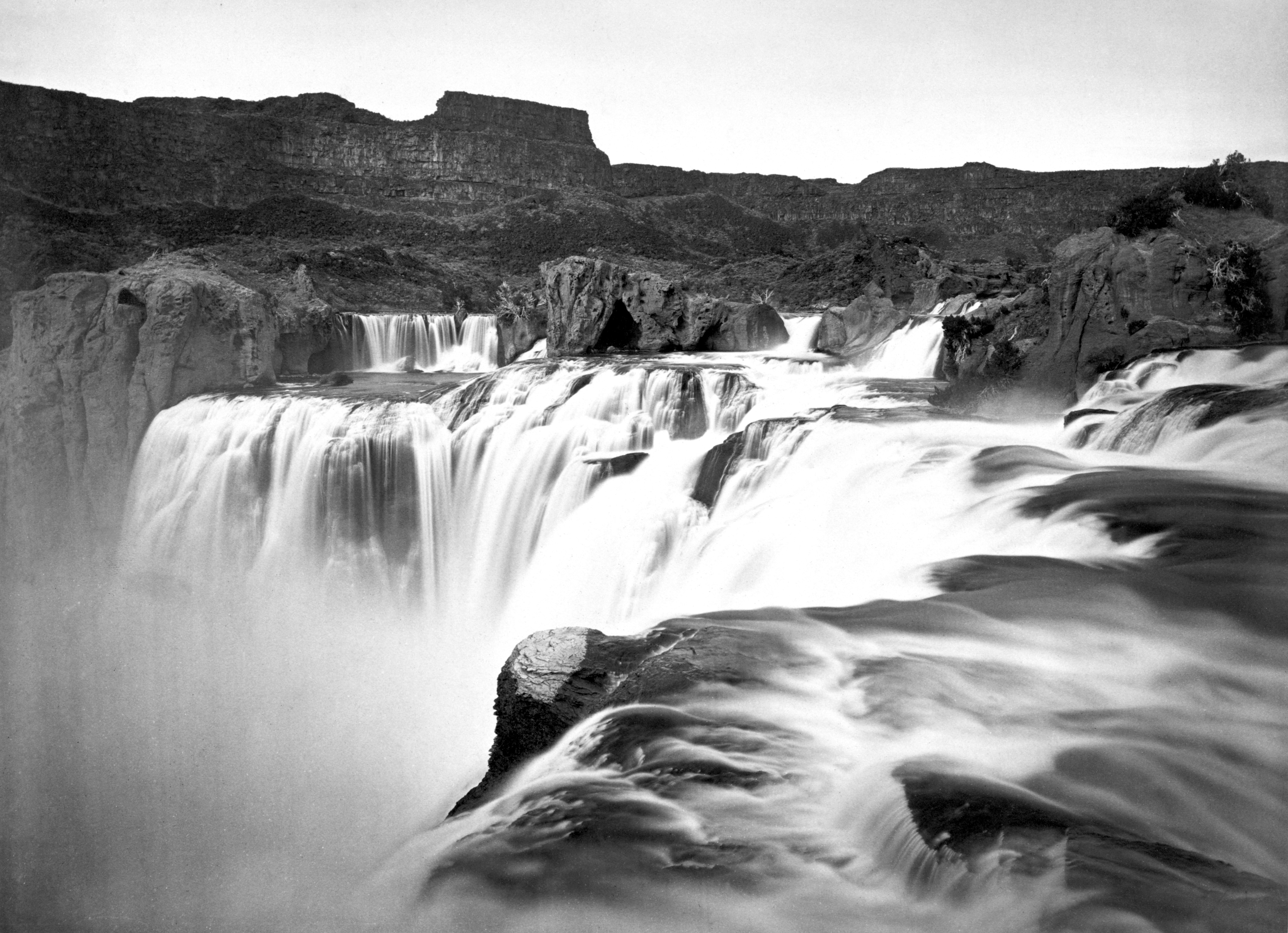

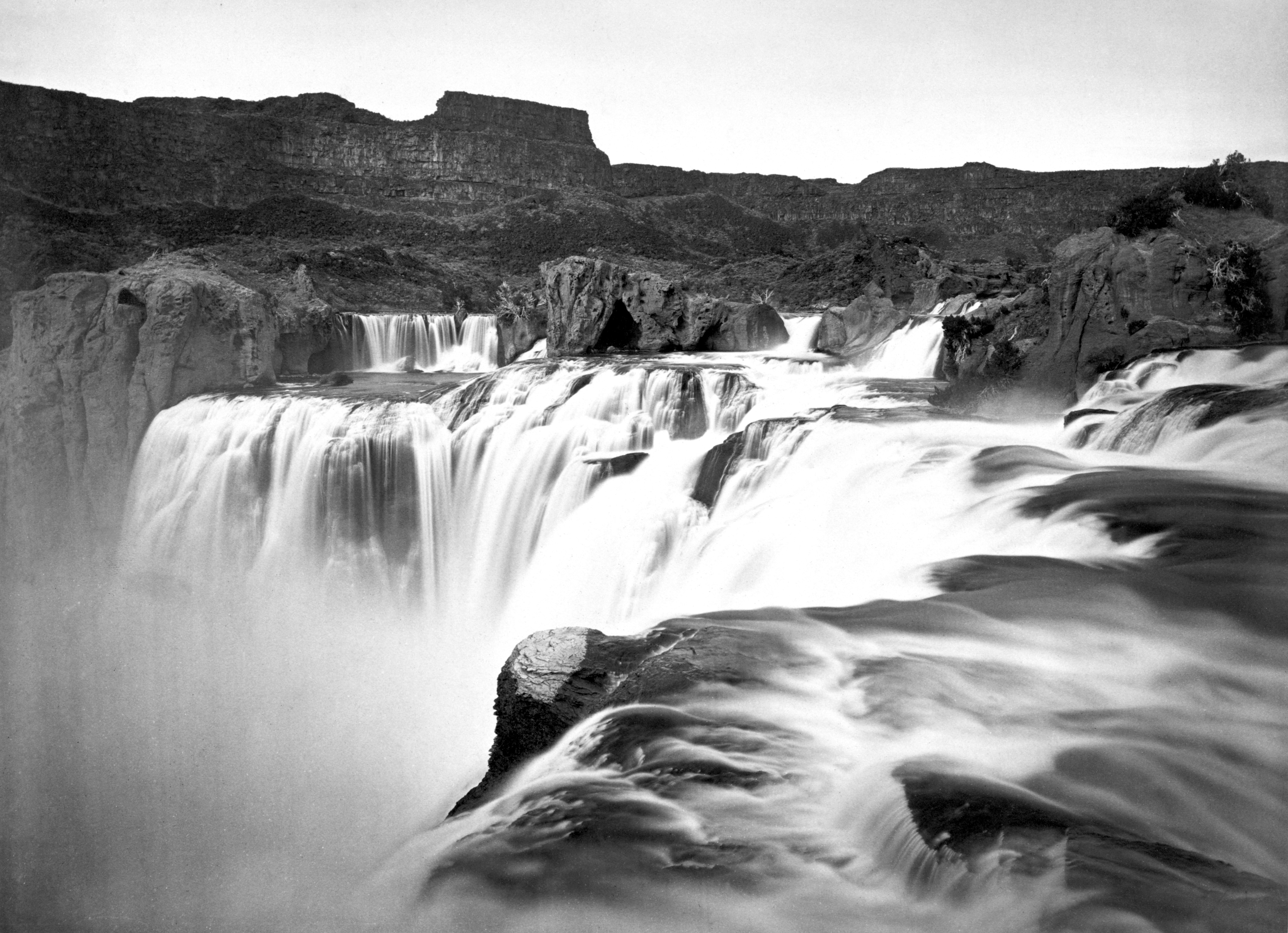

Under Hunt, fearing attack by the

Niitsitapi, the overland expedition veered south of Lewis and Clark's route into what is now Wyoming and in the process passed across

Union Pass

Union Pass is a high mountain pass in the Wind River Range in Fremont County, Wyoming, Fremont County of western Wyoming in the United States. The pass is located on the Continental Divide between the Gros Ventre mountains on the west and the Wi ...

and into

Jackson Hole

Jackson Hole (originally called Jackson's Hole by mountain men) is a valley between the Gros Ventre and Teton mountain ranges in the U.S. state of Wyoming, near the border with Idaho, in Teton County, one of the richest counties in the Unite ...

, Wyoming. From there they went over the

Teton Range

The Teton Range is a mountain range of the Rocky Mountains in North America. It extends for approximately in a northŌĆōsouth direction through the U.S. state of Wyoming, east of the Idaho state line. It is south of Yellowstone National Park and ...

via

Teton Pass

Teton Pass is a high mountain pass in the western United States, located at the southern end of the Teton Range in western Wyoming, between Wilson and Victor, Idaho. At an elevation of above sea level, the pass provides access from the Jackson Ho ...

and then down to the Snake River into modern

Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the CanadaŌĆōUnited States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

. They abandoned their horses at the Snake River, made dugout canoes, and attempted to use the river for transport. After a few days' travel they soon discovered that steep canyons, waterfalls and impassable rapids made travel by river impossible. Too far from their horses to retrieve them, they had to cache most of their goods and walk the rest of the way to the Columbia River where they made new boats and traveled to the newly established Fort Astoria. The expedition demonstrated that much of the route along the Snake River plain and across to the Columbia was passable by pack train or with minimal improvements, even wagons. This knowledge would be incorporated into the concatenated trail segments as the Oregon Trail took its early shape.

Pacific Fur Company partner

Robert Stuart led a small group of men back east to report to Astor. The group planned to retrace the path followed by the overland expedition back up to the east following the Columbia and Snake rivers. Fear of a Native American attack near Union Pass in Wyoming forced the group further south where they discovered South Pass, a wide and easy pass over the Continental Divide. The party continued east via the

Sweetwater River,

North Platte River

The North Platte River is a major tributary of the Platte River and is approximately long, counting its many curves.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed March 21, 2011 In a ...

(where they spent the winter of 1812ŌĆō13) and

Platte River

The Platte River () is a major river in the State of Nebraska. It is about long; measured to its farthest source via its tributary, the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which itself ...

to the Missouri River, finally arriving in St. Louis in the spring of 1813. The route they had used appeared to potentially be a practical wagon route, requiring minimal improvements, and Stuart's journals provided a meticulous account of most of the route. Because of the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 ŌĆō 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

and the lack of U.S. fur trading posts in the Pacific Northwest, most of the route was unused for more than 10 years.

North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company

In August 1811, three months after Fort Astor was established,

David Thompson and his team of British North West Company explorers came floating down the Columbia to Fort Astoria. He had just completed a journey through much of western Canada and most of the Columbia River drainage system. He was mapping the country for possible fur trading posts. Along the way he camped at the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers and posted a notice claiming the land for Britain and stating the intention of the North West Company to build a fort on the site (

Fort Nez Perces was later established there). Astor, concerned the British navy would seize their forts and supplies in the War of 1812, sold to the North West Company in 1812 their forts, supplies and furs on the Columbia and Snake River. The North West Company started establishing more forts and trading posts of its own.

By 1821, when armed hostilities broke out with its

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business div ...

(HBC) rivals, the North West Company was pressured by the British government to merge with the HBC. The HBC had nearly a complete monopoly on trading (and most governing issues) in the Columbia District, or Oregon Country as it was referred to by the Americans, and also in

Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land t ...

. That year the British parliament passed a statute applying the laws of

Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

to the district and giving the HBC power to enforce those laws.

From 1812 to 1840, the British, through the HBC, had nearly complete control of the Pacific Northwest and the western half of the Oregon Trail. In theory, the

Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

, which ended the War of 1812, restored possession of Oregon territory to the United States. "Joint occupation" of the region was formally established by the

Anglo-American Convention of 1818

The Convention respecting fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves, also known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, is an international treaty signed in 1818 betw ...

. The British, through the HBC, tried to discourage any U.S. trappers, traders and settlers from work or settlement in the Pacific Northwest.

By overland travel, American missionaries and early settlers (initially mostly ex-trappers) started showing up in Oregon around 1824. Although officially the HBC discouraged settlement because it interfered with its lucrative fur trade, its Chief Factor at Fort Vancouver,

John McLoughlin

John McLoughlin, baptized Jean-Baptiste McLoughlin, (October 19, 1784 – September 3, 1857) was a French-Canadian, later American, Chief Factor and Superintendent of the Columbia District of the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver fro ...

, gave substantial help, including employment, until they could get established. In the early 1840s thousands of American settlers arrived and soon greatly outnumbered the British settlers in Oregon.

McLoughlin, despite working for the HBC, gave help in the form of loans, medical care, shelter, clothing, food, supplies and seed to U.S. emigrants. These new emigrants often arrived in Oregon tired, worn out, nearly penniless, with insufficient food or supplies, just as winter was coming on. McLoughlin would later be hailed as the Father of Oregon.

The

York Factory Express

The York Factory Express, usually called "the Express" and also the Columbia Express and the Communication, was a 19th-century fur brigade operated by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). Roughly in length, it was the main overland connection between ...

, establishing another route to the Oregon territory, evolved from an earlier express brigade used by the North West Company between Fort Astoria and

Fort William, Ontario on

Lake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

. By 1825 the HBC started using two brigades, each setting out from opposite ends of the express routeŌĆöone from

Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of the ...

on the Columbia River and the other from

York Factory

York Factory was a settlement and Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) factory (trading post) located on the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay in northeastern Manitoba, Canada, at the mouth of the Hayes River, approximately south-southeast of Churchill. Yo ...

on Hudson BayŌĆöin spring and passing each other in the middle of the continent. This established a "quick"—about 100 days for one way—to resupply its forts and fur trading centers as well as collecting the furs the posts had bought and transmitting messages between Fort Vancouver and York Factory on Hudson Bay.

The HBC built a new much larger Fort Vancouver in 1824 slightly upstream of Fort Astoria on the north side of the Columbia River (they were hoping the Columbia would be the future CanadaŌĆōU.S. border). The fort quickly became the center of activity in the Pacific Northwest. Every year ships would come from London to the Pacific (via

Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ram├Łrez ...

) to drop off supplies and trade goods in its trading posts in the Pacific Northwest and pick up the accumulated furs used to pay for these supplies. It was the nexus for the fur trade on the Pacific Coast; its influence reached from the Rocky Mountains to the

Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, N─ü Mokupuni o HawaiŌĆśi) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

, and from

Russian Alaska

Russian America (russian: ąĀčāčüčüą║ą░čÅ ąÉą╝ąĄčĆąĖą║ą░, Russkaya Amerika) was the name for the Russian Empire's colonial possessions in North America from 1799 to 1867. It consisted mostly of present-day Alaska in the United States, but a ...

into Mexican-controlled California. At its pinnacle in about 1840, Fort Vancouver and its Factor (manager) watched over 34 outposts, 24 ports, 6 ships, and about 600 employees.

When American emigration over the Oregon Trail began in earnest in the early 1840s, for many settlers the fort became the last stop on the Oregon Trail where they could get supplies, aid and help before starting their homesteads.

Fort Vancouver was the main re-supply point for nearly all Oregon trail travelers until U.S. towns could be established. The HBC established

Fort Colvile

The trade center Fort Colvile (also Fort Colville) was built by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) at Kettle Falls on the Columbia River in 1825 and operated in the Columbia fur district of the company. Named for Andrew Colvile,Lewis, S. William. ' ...

in 1825 on the Columbia River near

Kettle Falls

Kettle Falls (Salish: Shonitkwu, meaning "roaring or noisy waters", also Schwenetekoo translated as "Keep Sounding Water") was an ancient and important salmon fishing site on the upper reaches of the Columbia River, in what is today the U.S. s ...

as a good site to collect furs and control the upper Columbia River fur trade.

Fort Nisqually

Fort Nisqually was an important fur trading and farming post of the Hudson's Bay Company in the Puget Sound area, part of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department. It was located in what is now DuPont, Washington. Today it is a living hist ...

was built near the present town of

DuPont

DuPont de Nemours, Inc., commonly shortened to DuPont, is an American multinational chemical company first formed in 1802 by French-American chemist and industrialist ├ēleuth├©re Ir├®n├®e du Pont de Nemours. The company played a major role in ...

, Washington and was the first HBC fort on Puget Sound.

Fort Victoria was erected in 1843 and became the headquarters of operations in British Columbia, eventually growing into modern-day

Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, the capital city of British Columbia.

By 1840 the HBC had three forts:

Fort Hall

Fort Hall was a fort in the western United States that was built in 1834 as a fur trading post by Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth. It was located on the Snake River in the eastern Oregon Country, now part of present-day Bannock County in southeastern Ida ...

(purchased from

Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth

Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth (January 29, 1802 – August 31, 1856) was an American inventor and businessman in Boston, Massachusetts who contributed greatly to its ice industry. Due to his inventions, Boston could harvest and ship ice internati ...

in 1837),

Fort Boise

Fort Boise is either of two different locations in the western United States, both in southwestern Idaho. The first was a Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) trading post near the Snake River on what is now the Oregon border (in present-day Canyon County ...

and

Fort Nez Perce

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

on the western end of the Oregon Trail route as well as Fort Vancouver near its terminus in the

Willamette Valley

The Willamette Valley ( ) is a long valley in Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. The Willamette River flows the entire length of the valley and is surrounded by mountains on three sides: the Cascade Range to the east, ...

. With minor exceptions they all gave substantial and often desperately needed aid to the early Oregon Trail pioneers.

When the fur trade slowed in 1840 because of fashion changes in men's hats, the value of the Pacific Northwest to the British was seriously diminished. Canada had few potential settlers who were willing to move more than to the Pacific Northwest, although several hundred ex-trappers, British and American, and their families did start settling in Oregon, Washington and California. They used most of the York Express route through northern Canada. In 1841,

James Sinclair, on orders from Sir

George Simpson, guided nearly 200 settlers from the

Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assiniboia, Assinboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hud ...

(located at the junction of the

Assiniboine River

The Assiniboine River (''; french: Rivi├©re Assiniboine'') is a river that runs through the prairies of Western Canada in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. It is a tributary of the Red River of the North, Red River. The Assiniboine is a typical meand ...

and

Red River near present

Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749,6 ...

,

Manitoba

Manitoba ( ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population o ...

, Canada) into the Oregon territory. This attempt at settlement failed when most of the families joined the settlers in the Willamette Valley, with their promise of free land and HBC-free government.

In 1846, the

Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty is a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to t ...

ending the

Oregon boundary dispute

The Oregon boundary dispute or the Oregon Question was a 19th-century territorial dispute over the political division of the Pacific Northwest of North America between several nations that had competing territorial and commercial aspirations in ...

was signed with Britain. The British lost the land north of the Columbia River they had so long controlled. The new

CanadaŌĆōUnited States border

The border between Canada and the United States is the longest international border in the world. The terrestrial boundary (including boundaries in the Great Lakes, Atlantic, and Pacific coasts) is long. The land border has two sections: Can ...

was established much further north at the

49th parallel. The treaty granted the HBC navigation rights on the Columbia River for supplying their fur posts, clear titles to their trading post properties allowing them to be sold later if they wanted, and left the British with good anchorages at

Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the ...

and Victoria. It gave the United States what it mostly wanted, a "reasonable" boundary and a good anchorage on the West Coast in Puget Sound. While there were almost no United States settlers in the future state of Washington in 1846, the United States had already demonstrated it could induce thousands of settlers to go to the Oregon Territory, and it would be only a short time before they would vastly outnumber the few hundred HBC employees and retirees living in Washington.

Great American Desert

Reports from expeditions in 1806 by Lieutenant

Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 ŌĆō April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson th ...

and in 1819 by Major

Stephen Long described the

Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

as "unfit for human habitation" and as "The

Great American Desert

The term Great American Desert was used in the 19th century to describe the part of North America east of the Rocky Mountains to about the 100th meridian. It can be traced to Stephen H. Long's 1820 scientific expedition which put the Great Am ...

". These descriptions were mainly based on the relative lack of timber and surface water. The images of sandy wastelands conjured up by terms like "desert" were tempered by the many reports of vast herds of millions of

Plains Bison

The Plains bison (''Bison bison bison'') is one of two subspecies/ecotypes of the American bison, the other being the wood bison (''B. b. athabascae''). A natural population of Plains bison survives in Yellowstone National Park (the Yellowstone ...

that somehow managed to live in this "desert". In the 1840s, the Great Plains appeared to be unattractive for settlement and were illegal for homesteading until well after 1846ŌĆöinitially it was set aside by the U.S. government for Native American settlements. The next available land for general settlement, Oregon, appeared to be free for the taking and had fertile lands, disease-free climate (

yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains ŌĆō particularly in the back ŌĆō and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

and

malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

were then prevalent in much of the Missouri and

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

drainage), extensive uncut, unclaimed forests, big rivers, potential seaports, and only a few nominally British settlers.

Fur traders, trappers, and explorers

Fur trappers, often working for fur traders, followed nearly all possible streams looking for beaver in the years (1812ŌĆō40) the fur trade was active. Fur traders included

Manuel Lisa

Manuel Lisa, also known as Manuel de Lisa (September 8, 1772 in New Orleans Louisiana (New Spain) ŌĆō August 12, 1820 in St. Louis, Missouri), was a Spanish citizen and later, became an American citizen who, while living on the western frontier, b ...

, Robert Stuart,

William Henry Ashley

William Henry Ashley (c. 1778 ŌĆō March 26, 1838) was an American miner, land speculator, manufacturer, territorial militia general, politician, frontiersman, fur trader, entrepreneur, hunter, and slave owner. Ashley was best known for being th ...

,

Jedediah Smith

Jedediah Strong Smith (January 6, 1799 ŌĆō May 27, 1831) was an American clerk, transcontinental pioneer, frontiersman, hunter, trapper, author, cartographer, mountain man and explorer of the Rocky Mountains, the Western United States, and ...

,

William Sublette

William Lewis Sublette, also spelled Sublett (September 21, 1798 ŌĆō July 23, 1845), was an American frontiersman, trapper, North American fur trade, fur trader, explorer, and mountain man. After 1823, he became an agent of the Rocky Mountain Fu ...

,

Andrew Henry,

Thomas Fitzpatrick,

Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 ŌĆō May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and n ...

,

Jim Bridger

James Felix "Jim" Bridger (March 17, 1804 ŌĆō July 17, 1881) was an American mountain man, trapper, Army scout, and wilderness guide who explored and trapped in the Western United States in the first half of the 19th century. He was known as Old ...

,

Peter Skene Ogden

Peter Skene Ogden (alternately Skeene, Skein, or Skeen; baptised 12 February 1790 ŌĆō 27 September 1854) was a British-Canadian fur trader and an early explorer of what is now British Columbia and the Western United States. During his many expedi ...

,

David Thompson,

James Douglas,

Donald Mackenzie,

Alexander Ross,

James Sinclair, and other

mountain men

A mountain man is an explorer who lives in the wilderness. Mountain men were most common in the North American Rocky Mountains from about 1810 through to the 1880s (with a peak population in the early 1840s). They were instrumental in opening up ...

. Besides describing and naming many of the rivers and mountains in the

Intermountain West

The Intermountain West, or Intermountain Region, is a geographic and geological region of the Western United States. It is located between the front ranges of the Rocky Mountains on the east and the Cascade Range and Sierra Nevada on the west ...

and Pacific Northwest, they often kept diaries of their travels and were available as guides and consultants when the trail started to become open for general travel. The fur trade business wound down to a very low level just as the Oregon trail traffic seriously began around 1840.

In fall of 1823, Jedediah Smith and Thomas Fitzpatrick led their trapping crew south from the

Yellowstone River

The Yellowstone River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the Western United States. Considered the principal tributary of upper Missouri, via its own tributaries it drains an area with headwaters across the mountains an ...

to the Sweetwater River. They were looking for a safe location to spend the winter. Smith reasoned since the Sweetwater flowed east it must eventually run into the Missouri River. Trying to transport their extensive fur collection down the Sweetwater and North Platte River, they found after a near disastrous canoe crash that the rivers were too swift and rough for water passage. On July 4, 1824, they cached their furs under a dome of rock they named

Independence Rock and started their long trek on foot to the Missouri River. Upon arriving back in a settled area they bought pack horses (on credit) and retrieved their furs. They had re-discovered the route that Robert Stuart had taken in 1813ŌĆöeleven years before. Thomas Fitzpatrick was often hired as a guide when the fur trade dwindled in 1840. Smith was killed by Comanche natives around 1831.

Up to 3,000 mountain men were

trappers

Animal trapping, or simply trapping or gin, is the use of a device to remotely catch an animal. Animals may be trapped for a variety of purposes, including food, the fur trade, hunting, pest control, and wildlife management.

History

Neolithic ...

and

explorers

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

, employed by various British and United States fur companies or working as free trappers, who roamed the North American Rocky Mountains from about 1810 to the early 1840s. They usually traveled in small groups for mutual support and protection. Trapping took place in the fall when the fur became prime. Mountain men primarily trapped

beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers ar ...

and sold the skins. A good beaver skin could bring up to $4 at a time when a man's wage was often $1 per day. Some were more interested in exploring the West. In 1825, the first significant American

Rendezvous occurred on the Henry's Fork of the

Green River Green River may refer to:

Rivers

Canada

* Green River (British Columbia), a tributary of the Lillooet River

*Green River, a tributary of the Saint John River, also known by its French name of Rivi├©re Verte

*Green River (Ontario), a tributary of ...

. The trading supplies were brought in by a large party using pack trains originating on the Missouri River. These pack trains were then used to haul out the fur bales. They normally used the north side of the Platte RiverŌĆöthe same route used 20 years later by the

Mormon Trail

The Mormon Trail is the long route from Illinois to Utah that members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traveled for 3 months. Today, the Mormon Trail is a part of the United States National Trails System, known as the Mormon ...

. For the next 15 years the American rendezvous was an annual event moving to different locations, usually somewhere on the Green River in the future state of

Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

. Each rendezvous, occurring during the slack summer period, allowed the fur traders to trade for and collect the furs from the trappers and their Native American allies without having the expense of building or maintaining a fort or wintering over in the cold Rockies. In only a few weeks at a rendezvous a year's worth of trading and celebrating would take place as the traders took their furs and remaining supplies back east for the winter and the trappers faced another fall and winter with new supplies. Trapper

Jim Beckwourth

James Pierson Beckwourth (born Beckwith, April 26, 1798 or 1800 ŌĆō October 29, 1866 or 1867), was an American mountain man, fur trader, and explorer. Beckwourth was known as "Bloody Arm" because of his skill as a fighter. He was mixed-race and b ...

described the scene as one of "Mirth, songs, dancing, shouting, trading, running, jumping, singing, racing, target-shooting, yarns, frolic, with all sorts of extravagances that white men or Indians could invent." In 1830, William Sublette brought the first wagons carrying his trading goods up the Platte, North Platte, and Sweetwater rivers before crossing over South Pass to a fur trade rendezvous on the Green River near the future town of

Big Piney, Wyoming. He had a crew that dug out the gullies and river crossings and cleared the brush where needed. This established that the eastern part of most of the Oregon Trail was passable by wagons. In the late 1830s the HBC instituted a policy intended to destroy or weaken the American fur trade companies. The HBC's annual collection and re-supply Snake River Expedition was transformed to a trading enterprise. Beginning in 1834, it visited the American Rendezvous to undersell the American tradersŌĆölosing money but undercutting the American fur traders. By 1840 the fashion in Europe and Britain shifted away from the formerly very popular beaver felt hats and prices for furs rapidly declined and the trapping almost ceased.

Fur traders tried to use the Platte River, the main route of the eastern Oregon Trail, for transport but soon gave up in frustration as its many channels and islands combined with its muddy waters were too shallow, crooked and unpredictable to use for water transport. The Platte proved to be unnavigable. The Platte River and North Platte River Valley, however, became an easy roadway for wagons, with its nearly flat plain sloping easily up and heading almost due west.

There were several U.S. government-sponsored explorers who explored part of the Oregon Trail and wrote extensively about their explorations. Captain

Benjamin Bonneville

Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville (April 14, 1796 ŌĆō June 12, 1878) was an American officer in the United States Army, fur trade, fur trapper, and explorer in the American West. He is noted for his expeditions to the Oregon Country and the Gre ...

on his expedition of 1832 to 1834 explored much of the Oregon trail and brought wagons up the Platte, North Platte, Sweetwater route across South Pass to the Green River in Wyoming. He explored most of Idaho and the Oregon Trail to the Columbia. The account of his explorations in the west was published by

Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 ŌĆō November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He is best known for his short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and " The Legen ...

in 1838.

John C. Fr├®mont

John Charles Fr├®mont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

of the

U.S. Army's Corps of Topographical Engineers and his guide Kit Carson led three expeditions from 1842 to 1846 over parts of California and Oregon. His explorations were written up by him and his wife

Jessie Benton Fr├®mont

Jessie Ann Benton Fr├®mont (May 31, 1824 ŌĆō December 27, 1902) was an American writer and political activist. She was the daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton and the wife of military officer, explorer, and politician John C ...

and were widely published. The first detailed map of California and Oregon were drawn by Fr├®mont and his

topographer

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary scie ...

s and

cartographers

Cartography (; from grc, Žć╬¼ŽüŽä╬ĘŽé , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an im ...

in about 1848.

Missionaries

In 1834, The Dalles

Methodist Mission

The Methodist Mission was the Methodist Episcopal Church's 19th-century conversion efforts in the Pacific Northwest. Local Indigenous cultures were introduced to western culture and Christianity. Superintendent Jason Lee was the principal leader fo ...

was founded by Reverend

Jason Lee Jason Lee may refer to:

Entertainment

*Jason Lee (actor) (born 1970), American film and TV actor and former professional skateboarder

*Jason Scott Lee (born 1966), Asian American film actor

* Jaxon Lee (Jason Christopher Lee, born 1968), American v ...

just east of

Mount Hood

Mount Hood is a potentially active stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc. It was formed by a subduction zone on the Pacific coast and rests in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located about east-southeast of Portlan ...

on the

Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''NchŌĆÖi-W├Āna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

. In 1836,

Henry H. Spalding

Henry Harmon Spalding (1803ŌĆō1874), and his wife Eliza Hart Spalding (1807ŌĆō1851) were prominent Presbyterian missionaries and educators working primarily with the Nez Perce in the U.S. Pacific Northwest. The Spaldings and their fellow missio ...

and

Marcus Whitman

Marcus Whitman (September 4, 1802 ŌĆō November 29, 1847) was an American physician and missionary.

In 1836, Marcus Whitman led an overland party by wagon to the West. He and his wife, Narcissa, along with Reverend Henry Spalding and his wife, E ...

traveled west to establish the

Whitman Mission

Whitman Mission National Historic Site is a United States National Historic Site located just west of Walla Walla, Washington, at the site of the former Whitman Mission at Waiilatpu. On November 29, 1847, Dr. Marcus Whitman, his wife Narcissa ...

near modern-day

Walla Walla Walla Walla can refer to:

* Walla Walla people, a Native American tribe after which the county and city of Walla Walla, Washington, are named

* Place of many rocks in the Australian Aboriginal Wiradjuri language, the origin of the name of the town ...

, Washington. The party included the wives of the two men,

Narcissa Whitman

Narcissa Prentiss Whitman (March 14, 1808 ŌĆō November 29, 1847) was an American missionary in the Oregon Country of what would become the state of Washington. On their way to found the Protestant Whitman Mission in 1836 with her husband, Marcus ...

and

Eliza Hart Spalding

Eliza Hart Spalding (1807ŌĆō1851) was an American missionary who joined an Oregon missionary party with her husband Henry H. Spalding and settled among the Nez Perce People called the nimiipuu in Lapwai, Idaho. She was a well-educated woman who ...

, who became the first European-American women to cross the Rocky Mountains. En route, the party accompanied American fur traders going to the 1836 rendezvous on the Green River in Wyoming and then joined Hudson's Bay Company fur traders traveling west to Fort Nez Perce (also called

Fort Walla Walla

Fort Walla Walla is a United States Army fort located in Walla Walla, Washington. The first Fort Walla Walla was established July 1856, by Lieutenant Colonel Edward Steptoe, 9th Infantry Regiment. A second Fort Walla Walla was occupied Septemb ...

). The group was the first to travel in wagons all the way to Fort Hall, where the wagons were abandoned at the urging of their guides. They used pack animals for the rest of the trip to Fort Walla Walla and then floated by boat to Fort Vancouver to get supplies before returning to start their missions. Other missionaries, mostly husband and wife teams using wagon and pack trains, established missions in the Willamette Valley, as well as various locations in the future states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

Early emigrants

On May 1, 1839, a group of eighteen men from

Peoria, Illinois

Peoria ( ) is the county seat of Peoria County, Illinois, United States, and the largest city on the Illinois River. As of the United States Census, 2020, 2020 census, the city had a population of 113,150. It is the principal city of the Peoria ...

, set out with the intention of colonizing the Oregon country on behalf of the United States of America and drive out the HBC operating there. The men of the

Peoria Party

The Peoria Party was a group of men from Peoria in the U.S. state of Illinois, who set out about May 1, 1839, with the intention to colonize the Oregon Country on behalf of the United States and to drive out the English fur-trading companies ope ...

were among the first pioneers to traverse most of the Oregon Trail. They were initially led by

Thomas J. Farnham

Thomas Jefferson Farnham (1804ŌĆō1848) was an explorer and author of the American West in the first half of the 19th century. His travels included interaction with missionary Jason Lee, and he later led a wagon train on the Oregon Trail. While in O ...

and called themselves the

Oregon Dragoons

The Peoria Party was a group of men from Peoria in the U.S. state of Illinois, who set out about May 1, 1839, with the intention to colonize the Oregon Country on behalf of the United States and to drive out the English fur-trading companies ope ...

. They carried a large flag emblazoned with their motto "''Oregon Or The Grave''". Although the group split up near

Bent's Fort

Bent's Old Fort is an 1833 fort located in Otero County in southeastern Colorado, United States. A company owned by Charles Bent and William Bent and Ceran St. Vrain built the fort to trade with Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Plains Indians and ...

on the

South Platte

The South Platte River is one of the two principal tributaries of the Platte River. Flowing through the U.S. states of Colorado and Nebraska, it is itself a major river of the American Midwest and the American Southwest/ Mountain West. Its ...

and Farnham was deposed as leader, nine of their members eventually did reach Oregon.

In September 1840,

Robert Newell,

Joseph L. Meek

Joseph Lafayette "Joe" Meek (February 9, 1810 – June 20, 1875) was a pioneer, mountain man, law enforcement official, and politician in the Oregon Country and later Oregon Territory of the United States. A trapper involved in the fur trade b ...

, and their families reached Fort Walla Walla with three wagons that they had driven from Fort Hall. Their wagons were the first to reach the Columbia River over land, and they opened the final leg of Oregon Trail to wagon traffic.

In 1841, the

Bartleson-Bidwell Party was the first emigrant group credited with using the Oregon Trail to emigrate west. The group set out for California, but about half the party left the original group at

Soda Springs, Idaho, and proceeded to the Willamette Valley in Oregon, leaving their wagons at Fort Hall.

On May 16, 1842, the second organized wagon train set out from Elm Grove, Missouri, with more than 100 pioneers. The party was led by

Elijah White

Dr. Elijah White (1806ŌĆō1879) was a missionary and agent for the United States government in Oregon Country during the mid-19th century. A trained physician from New York State, he first traveled to Oregon as part of the Methodist Mission in t ...

. The group broke up after passing Fort Hall with most of the single men hurrying ahead and the families following later.

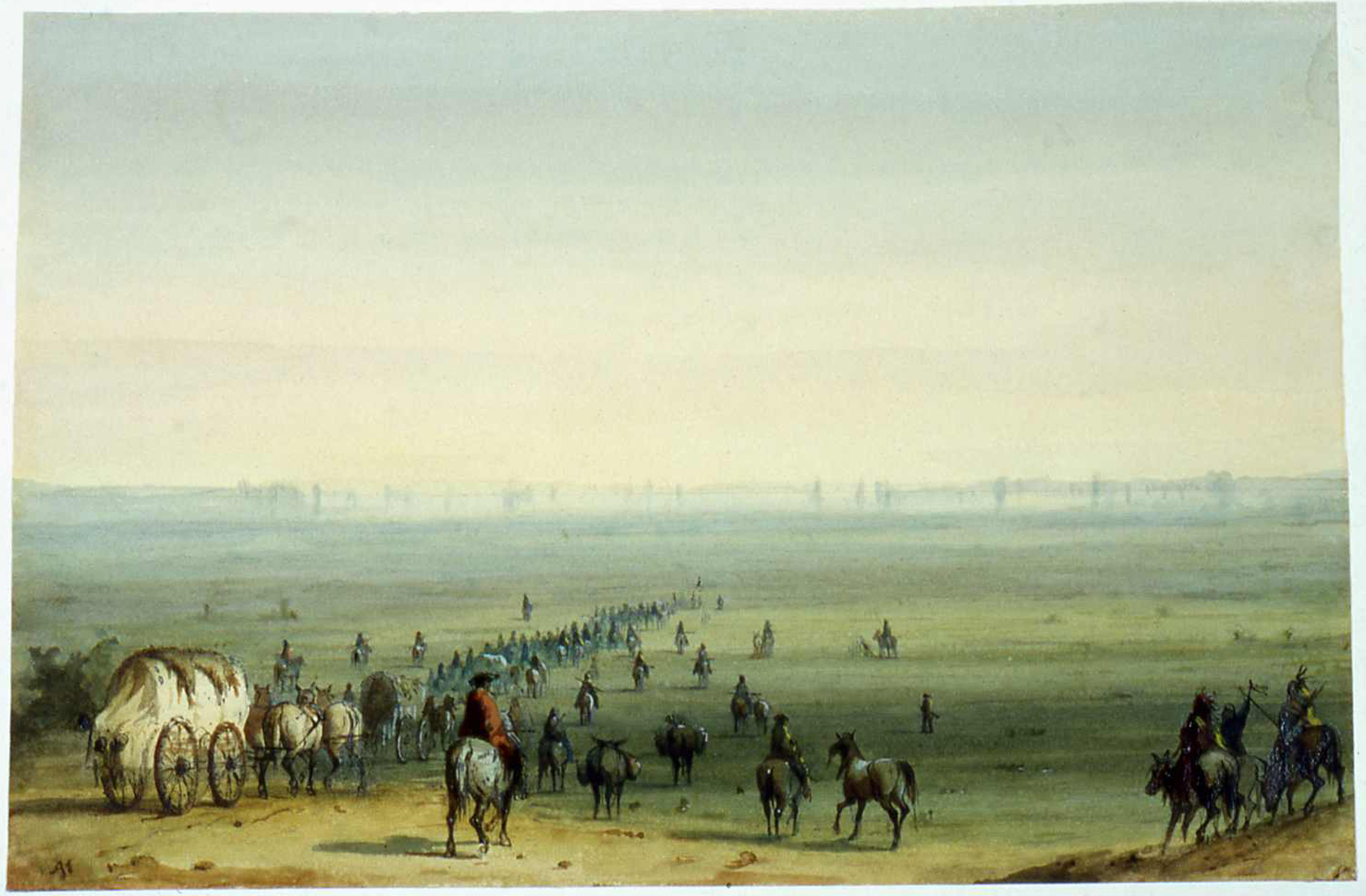

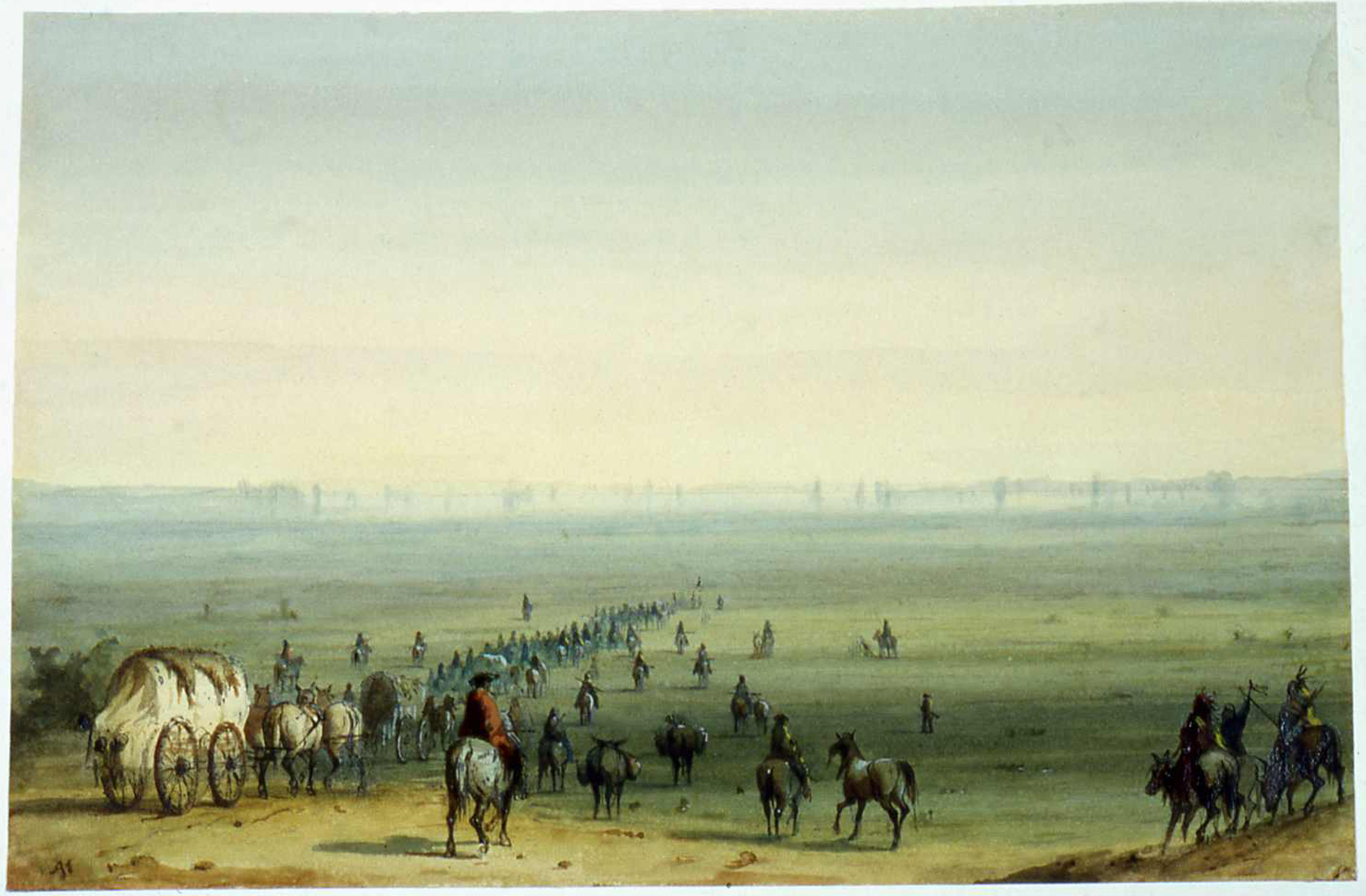

Great Migration of 1843

In what was dubbed "The Great Migration of 1843" or the "Wagon Train of 1843", an estimated 700 to 1,000 emigrants left for Oregon. They were led initially by John Gantt, a former U.S. Army Captain and fur trader who was contracted to guide the train to Fort Hall for $1 per person. The winter before, Marcus Whitman had made a brutal mid-winter trip from Oregon to St. Louis to appeal a decision by his mission backers to abandon several of the Oregon missions. He joined the wagon train at the Platte River for the return trip. When the pioneers were told at Fort Hall by agents from the Hudson's Bay Company that they should abandon their wagons there and use pack animals the rest of the way, Whitman disagreed and volunteered to lead the wagons to Oregon. He believed the wagon trains were large enough that they could build whatever road improvements they needed to make the trip with their wagons. The biggest obstacle they faced was in the

Blue Mountains of Oregon where they had to cut and clear a trail through heavy timber. The wagons were stopped at

The Dalles

The Dalles is the largest city of Wasco County, Oregon, United States. The population was 16,010 at the 2020 census, and it is the largest city on the Oregon side of the Columbia River between the Portland Metropolitan Area, and Hermiston ...

, Oregon, by the lack of a road around Mount Hood. The wagons had to be disassembled and floated down the treacherous Columbia River and the animals herded over the rough

Lolo trail

Lolo can refer to:

Places United States

* Lolo, Montana, a census-designated place

* Lolo Butte, a summit in Oregon

* Lolo Pass (IdahoŌĆōMontana)

* Lolo Pass (Oregon)

* Lolo National Forest, Montana

* Lolo Peak, Montana

Elsewhere

* Lolo, Cam ...

to get by Mt. Hood. Nearly all of the settlers in the 1843 wagon trains arrived in the Willamette Valley by early October. A passable wagon trail now existed from the Missouri River to The Dalles. Jesse Applegate's account of the emigration, "

A Day with the Cow Column in 1843

''A Day with the Cow Column in 1843'' is a text composed by Jesse Applegate describing his experience leading one of the parties of pioneers to the Oregon Country in the Pacific Northwest of North America in 1843. It was published in the first volu ...

," has been described as "the best bit of literature left to us by any participant in the

regonpioneer movement..." and has been republished several times from 1868 to 1990.

In 1846, the

Barlow Road

The Barlow Road (at inception, Mount Hood Road) is a historic road in what is now the U.S. state of Oregon. It was built in 1846 by Sam Barlow and Philip Foster, with authorization of the Provisional Legislature of Oregon, and served as the la ...

was completed around Mount Hood, providing a rough but completely passable wagon trail from the Missouri River to the Willamette Valley: about .

Oregon Country

In 1843, settlers of the Willamette Valley drafted the

Organic Laws of Oregon

The Organic Laws of Oregon were two sets of legislation passed in the 1840s by a group of primarily American settlers based in the Willamette Valley. These laws were drafted after the Champoeg Meetings and created the structure of a government in ...

organizing land claims within the Oregon Country. Married couples were granted at no cost (except for the requirement to work and improve the land) up to (a

section

Section, Sectioning or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especially of a chapter, in books and documents

** Section sign ...

or square mile), and unmarried settlers could claim . As the group was a provisional government with no authority, these claims were not valid under United States or British law, but they were eventually honored by the United States in the

Donation Land Act

The Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, sometimes known as the Donation Land Act, was a statute enacted by the United States Congress in late 1850, intended to promote homestead settlements in the Oregon Territory. It followed the Distribution-Preem ...

of 1850. The Donation Land Act provided for married settlers to be granted and unmarried settlers . Following the expiration of the act in 1854 the land was no longer free but cost $1.25 per acre ($3.09/hectare) with a limit of ŌĆöthe same as most other unimproved government land.

Women on the Overland Trail

Consensus interpretations, as found in John Faragher's book, ''Women and Men on the Overland Trail'' (1979), held that men and women's power within marriage was uneven. This meant that women did not experience the trail as liberating, but instead only found harder work than they had handled back east. However, feminist scholarship, by historians such as Lillian Schlissel, Sandra Myres, and Glenda Riley, suggests men and women did not view the West and western migration in the same way. Whereas men might deem the dangers of the trail acceptable if there was a strong economic reward at the end, women viewed those dangers as threatening to the stability and survival of the family. Once they arrived at their new western home, women's public role in building western communities and participating in the western economy gave them a greater authority than they had known back East. There was a "female frontier" that was distinct and different from that experienced by men.

Women's diaries kept during their travels or the letters they wrote home once they arrived at their destination supports these contentions. Women wrote with sadness and concern of the numerous deaths along the trail. Anna Maria King wrote to her family in 1845 about her trip to the

Luckiamute Valley Oregon and of the multiple deaths experienced by her traveling group:

But listen to the deaths: Sally Chambers, John King and his wife, their little daughter Electa and their babe, a son 9 months old, and Dulancy C. Norton's sister are gone. Mr. A. Fuller lost his wife and daughter Tabitha. Eight of our two families have gone to their long home.

Similarly, emigrant

Martha Gay Masterson, who traveled the trail with her family at the age of 13, mentioned the fascination she and other children felt for the graves and loose skulls they would find near their camps.

Anna Maria King, like many other women, also advised family and friends back home of the realities of the trip and offered advice on how to prepare for the trip. Women also reacted and responded, often enthusiastically, to the landscape of the West. Betsey Bayley in a letter to her sister, Lucy P. Griffith described how travelers responded to the new environment they encountered:

The mountains looked like volcanoes and the appearance that one day there had been an awful thundering of volcanoes and a burning world. The valleys were all covered with a white crust and looked like salaratus. Some of the company used it to raise their bread.

Mormon emigration

Following persecution and mob action in

Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

,

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, and other states, and the assassination of their prophet

Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

in 1844,

Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

leader

Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

led settlers in the

Latter Day Saints

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or SmithŌĆōRigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by Jo ...

(LDS) church west to the

Salt Lake Valley

Salt Lake Valley is a valley in Salt Lake County in the north-central portion of the U.S. state of Utah. It contains Salt Lake City and many of its suburbs, notably Murray, Sandy, South Jordan, West Jordan, and West Valley City; its total po ...

in present-day Utah. In 1847 Young led a small, fast-moving group from their

Winter Quarters encampments near

Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest city ...

, Nebraska, and their approximately 50 temporary settlements on the Missouri River in

Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

including

Council Bluffs

Council Bluffs is a city in and the county seat of Pottawattamie County, Iowa, United States. The city is the most populous in Southwest Iowa, and is the third largest and a primary city of the Omaha-Council Bluffs Metropolitan Area. It is lo ...

. About 2,200 LDS pioneers went that first year and they were charged with establishing farms, growing crops, building fences and herds, and establishing preliminary settlements to feed and support the many thousands of emigrants expected in the coming years. After ferrying across the Missouri River and establishing wagon trains near what became Omaha, the Mormons followed the northern bank of the Platte River in

Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

to

Fort Laramie

Fort Laramie (founded as Fort William and known for a while as Fort John) was a significant 19th-century trading-post, diplomatic site, and military installation located at the confluence of the Laramie and the North Platte rivers. They joined ...

in present-day Wyoming. They initially started out in 1848 with trains of several thousand emigrants, which were rapidly split into smaller groups to be more easily accommodated at the limited springs and acceptable camping places on the trail. The much larger presence of women and children meant these wagon trains did not try to cover as much ground in a single day as Oregon and California bound emigrants, typically taking about 100 days to cover the trip to Salt Lake City. (The Oregon and California emigrants averaged about per day.) In Wyoming, the Mormon emigrants followed the main Oregon/California/Mormon Trail through Wyoming to

Fort Bridger

Fort Bridger was originally a 19th-century fur trading outpost established in 1842, on Blacks Fork of the Green River, in what is now Uinta County, Wyoming, United States. It became a vital resupply point for wagon trains on the Oregon Trail, Ca ...

, where they split from the main trail and followed (and improved) the rough path known as

Hastings Cutoff

The Hastings Cutoff was an alternative route for westward emigrants to travel to California, as proposed by Lansford Hastings in ''The Emigrant's Guide to Oregon and California''. The ill-fated Donner Party infamously took the route in 1846.

Des ...

, used by the ill-fated

Donner Party

The Donner Party, sometimes called the DonnerŌĆōReed Party, was a group of American pioneers who migrated to California in a wagon train from the Midwest. Delayed by a multitude of mishaps, they spent the winter of 1846ŌĆō1847 snowbound in th ...

in 1846.

Between 1847 and 1860, over 43,000 Mormon settlers and tens of thousands of travelers on the

California Trail

The California Trail was an emigrant trail of about across the western half of the North American continent from Missouri River towns to what is now the state of California. After it was established, the first half of the California Trail f ...

and Oregon Trail followed Young to Utah. After 1848, the travelers headed to California or Oregon resupplied at the Salt Lake Valley, and then went back over the

Salt Lake Cutoff

The Salt Lake Cutoff is one of the many shortcuts (or cutoffs) that branched from the California, Mormon and Oregon Trails in the United States. It led northwest out of Salt Lake City, Utah and north of the Great Salt Lake for about before rejoin ...

, rejoining the trail near the future Idaho–Utah border at the

City of Rocks in Idaho.

Along the Mormon Trail, the Mormon pioneers established a number of ferries and made trail improvements to help later travelers and earn much needed money. One of the better known ferries was the Mormon Ferry across the North Platte near the future site of

Fort Caspar

Fort Caspar was a military post of the United States Army in present-day Wyoming, named after 2nd Lieutenant Caspar Collins, a U.S. Army officer who was killed in the 1865 Battle of the Platte Bridge Station against the Lakota and Cheyenne. Found ...

in Wyoming which operated between 1848 and 1852 and the

Green River Green River may refer to:

Rivers

Canada

* Green River (British Columbia), a tributary of the Lillooet River

*Green River, a tributary of the Saint John River, also known by its French name of Rivi├©re Verte

*Green River (Ontario), a tributary of ...

ferry near Fort Bridger which operated from 1847 to 1856. The ferries were free for Mormon settlers while all others were charged a toll ranging from $3 to $8.

California Gold Rush

In January 1848, James Marshall found gold in the Sierra Nevada portion of the

American River

, name_etymology =

, image = American River CA.jpg

, image_size = 300

, image_caption = The American River at Folsom

, map = Americanrivermap.png

, map_size = 300

, map_caption ...

, sparking the

California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848ŌĆō1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

. It is estimated that about two-thirds of the male population in Oregon went to California in 1848 to cash in on the opportunity. To get there, they helped build the Lassen Branch of the Applegate-Lassen Trail by cutting a wagon road through extensive forests. Many returned with significant gold which helped jump-start the Oregon economy. Over the next decade, gold seekers from the

Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

and

East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Eastern United States meets the North Atlantic Ocean. The eastern seaboard contains the coa ...

dramatically increased traffic on the Oregon and California Trails. The "forty-niners" often chose speed over safety and opted to use shortcuts such as the

Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff in Wyoming which reduced travel time by almost seven days but spanned nearly of desert without water, grass, or fuel for fires. 1849 was the first year of large scale

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

epidemics in the United States, and thousands are thought to have died along the trail on their way to CaliforniaŌĆömost buried in unmarked graves in Kansas and Nebraska. The adjusted 1850 U.S. Census of California showed this rush was overwhelmingly male with about 112,000 males to 8,000 females (with about 5,500 women over age 15). Women were significantly underrepresented

in the California Gold Rush, and sex ratios did not reach essential equality in California (and other western states) until about 1950. The relative scarcity of women gave them many opportunities to do many more things that were not normally considered women's work of this era. After 1849, the California Gold Rush continued for several years as the miners continued to find about $50,000,000 worth of gold per year at $21 per ounce. Once California was established as a prosperous state, many thousands more emigrated there each year for the opportunities.

Later emigration and uses of the trail

The trail was still in use during the

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, but traffic declined after 1855 when the

Panama Railroad

The Panama Canal Railway ( es, Ferrocarril de Panam├Ī) is a railway line linking the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean in Central America. The route stretches across the Isthmus of Panama from Col├│n (Atlantic) to Balboa (Pacific, near P ...

across the

Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panam├Ī), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

was completed. Paddle wheel steamships and sailing ships, often heavily subsidized to carry the mail, provided rapid transport to and from the east coast and

, Louisiana, to and from

Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panam├Ī ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, Rep├║blica de Panam├Ī), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

to ports in California and Oregon.

Over the years many ferries were established to help get across the many rivers on the path of the Oregon Trail. Multiple ferries were established on the Missouri River,

Kansas River

The Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, is a river in northeastern Kansas in the United States. It is the southwesternmost part of the Missouri River drainage, which is in turn the northwesternmost portion of the extensive Mississippi River dr ...

,

Little Blue River,

Elkhorn River