Gene McDaniels Songs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

The total complement of genes in an organism or cell is known as its

The total complement of genes in an organism or cell is known as its

The nucleotide sequence of a gene's DNA specifies the amino acid sequence of a protein through the

The nucleotide sequence of a gene's DNA specifies the amino acid sequence of a protein through the

Organisms inherit their genes from their parents. Asexual organisms simply inherit a complete copy of their parent's genome.

Organisms inherit their genes from their parents. Asexual organisms simply inherit a complete copy of their parent's genome.

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen

Wilhelm Johannsen (3 February 1857 – 11 November 1927) was a Danish pharmacist, botanist, plant physiologist, and geneticist. He is best known for coining the terms gene, phenotype and genotype, and for his 1903 "pure line" experiments in gen ...

coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

and the molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

s in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protein-coding genes and noncoding genes.

During gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. The ...

, the DNA is first copied into RNA. The RNA can be directly functional or be the intermediate template

Template may refer to:

Tools

* Die (manufacturing), used to cut or shape material

* Mold, in a molding process

* Stencil, a pattern or overlay used in graphic arts (drawing, painting, etc.) and sewing to replicate letters, shapes or designs

Co ...

for a protein that performs a function. The transmission of genes to an organism's offspring

In biology, offspring are the young creation of living organisms, produced either by a single organism or, in the case of sexual reproduction, two organisms. Collective offspring may be known as a brood or progeny in a more general way. This ca ...

is the basis of the inheritance of phenotypic trait

A phenotypic trait, simply trait, or character state is a distinct variant of a phenotypic characteristic of an organism; it may be either inherited or determined environmentally, but typically occurs as a combination of the two.Lawrence, Eleano ...

s. These genes make up different DNA sequences called genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

s. Genotypes along with environmental and developmental factors determine what the phenotypes will be. Most biological traits are under the influence of polygene

A polygene is a member of a group of non-epistatic genes that interact additively to influence a phenotypic trait, thus contributing to multiple-gene inheritance (polygenic inheritance, multigenic inheritance, quantitative inheritance), a type of ...

s (many different genes) as well as gene–environment interaction

Gene–environment interaction (or genotype–environment interaction or G×E) is when two different genotypes respond to environmental variation in different ways. A norm of reaction is a graph that shows the relationship between genes and envi ...

s. Some genetic traits are instantly visible, such as eye color

Eye color is a polygenic phenotypic character determined by two distinct factors: the pigmentation of the eye's iris and the frequency-dependence of the scattering of light by the turbid medium in the stroma of the iris.

In humans, the pi ...

or the number of limbs, and some are not, such as blood type

A blood type (also known as a blood group) is a classification of blood, based on the presence and absence of antibodies and inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrate ...

, the risk for specific diseases, or the thousands of basic biochemical

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology an ...

processes that constitute life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

.

Genes can acquire mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

s in their sequence, leading to different variants, known as allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

s, in the population

Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction using a ...

. These alleles encode slightly different versions of a gene, which may cause different phenotypical

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

traits. Usage of the term "having a gene" (e.g., "good genes," "hair color gene") typically refers to containing a different allele of the same, shared gene. Genes evolve due to natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

/ survival of the fittest

"Survival of the fittest" is a phrase that originated from Darwinian evolutionary theory as a way of describing the mechanism of natural selection. The biological concept of fitness is defined as reproductive success. In Darwinian terms, th ...

and genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and there ...

of the alleles.

The concept of ''gene'' continues to be refined as new phenomena are discovered. For example, regulatory regions

A regulatory sequence is a segment of a nucleic acid molecule which is capable of increasing or decreasing the expression of specific genes within an organism. Regulation of gene expression is an essential feature of all living organisms and vir ...

of a gene can be far removed from its coding region

The coding region of a gene, also known as the coding sequence (CDS), is the portion of a gene's DNA or RNA that codes for protein. Studying the length, composition, regulation, splicing, structures, and functions of coding regions compared to no ...

s, and coding regions can be split into several exon

An exon is any part of a gene that will form a part of the final mature RNA produced by that gene after introns have been removed by RNA splicing. The term ''exon'' refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene and to the corresponding sequen ...

s. Some viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

store their genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

in RNA instead of DNA and some gene products are functional non-coding RNA

A non-coding RNA (ncRNA) is a functional RNA molecule that is not translated into a protein. The DNA sequence from which a functional non-coding RNA is transcribed is often called an RNA gene. Abundant and functionally important types of non-c ...

s. Therefore, a broad, modern working definition of a gene is any discrete locus

Locus (plural loci) is Latin for "place". It may refer to:

Entertainment

* Locus (comics), a Marvel Comics mutant villainess, a member of the Mutant Liberation Front

* ''Locus'' (magazine), science fiction and fantasy magazine

** ''Locus Award' ...

of heritable, genomic sequence which affect an organism's traits by being expressed as a functional product or by regulation of gene expression

Regulation of gene expression, or gene regulation, includes a wide range of mechanisms that are used by cells to increase or decrease the production of specific gene products (protein or RNA). Sophisticated programs of gene expression are wide ...

.

The term ''gene'' was introduced by Danish botanist, plant physiologist and geneticist Wilhelm Johannsen

Wilhelm Johannsen (3 February 1857 – 11 November 1927) was a Danish pharmacist, botanist, plant physiologist, and geneticist. He is best known for coining the terms gene, phenotype and genotype, and for his 1903 "pure line" experiments in gen ...

in 1909. From p. 124: ''"Dieses "etwas" in den Gameten bezw. in der Zygote, … – kurz, was wir eben Gene nennen wollen – bedingt sind."'' (This "something" in the gametes or in the zygote, which has crucial importance for the character of the organism, is usually called by the quite ambiguous term ''Anlagen'' rimordium, from the German word ''Anlage'' for "plan, arrangement ; rough sketch" Many other terms have been suggested, mostly unfortunately in closer connection with certain hypothetical opinions. The word "pangene", which was introduced by Darwin, is perhaps used most frequently in place of ''Anlagen''. However, the word "pangene" was not well chosen, as it is a compound word containing the roots ''pan'' (the neuter form of Πας all, every) and ''gen'' (from γί-γ(ε)ν-ομαι, to become). Only the meaning of this latter .e., ''gen''comes into consideration here ; just the basic idea – amely,that a trait in the developing organism can be determined or is influenced by "something" in the gametes – should find expression. No hypothesis about the nature of this "something" should be postulated or supported by it. For that reason it seems simplest to use in isolation the last syllable ''gen'' from Darwin's well-known word, which alone is of interest to us, in order to replace, with it, the poor, ambiguous word ''Anlage''. Thus we will say simply "gene" and "genes" for "pangene" and "pangenes". The word gene is completely free of any hypothesis ; it expresses only the established fact that in any case many traits of the organism are determined by specific, separable, and thus independent "conditions", "foundations", "plans" – in short, precisely what we want to call genes.) It is inspired by the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

: γόνος, ''gonos'', that means offspring and procreation.

Conflicting definitions of 'gene'

There are lots of different ways to use the term "gene." Richard Dawkins, for example, wrote a book called "The Selfish Gene" where 'gene' simply meant any part of the chromosome that was subject to natural selection. This 'gene' is often referred to as the "Mendelian gene" whereas the physical gene described in this article is called the "molecular gene." The very first edition of the textbook "Molecular Biology of the Gene" (1965) described two kinds of molecular gene: protein-coding genes and those that specified functional RNA molecules such as ribosomal RNA and tRNA (noncoding genes). But the idea of two kinds of genes dates back to the late 1950s when Jacob and Monod speculated that regulatory genes might produce repressor RNAs. This idea of two kinds of genes is still part of the definition of a gene in most textbooks. For example, ::"The primary function of the genome is to produce RNA molecules. Selected portions of the DNA nucleotide sequence are copied into a corresponding RNA nucleotide sequence, which either encodes a protein (if it is an mRNA) or forms a 'structural' RNA, such as a transfer RNA (tRNA) or ribosomal RNA (rRNA) molecule. Each region of the DNA helix that produces a functional RNA molecule constitutes a gene." ::"We define a gene as a DNA sequence that is transcribed. This definition includes genes that do not encode proteins (not all transcripts are messenger RNA). The definition normally excludes regions of the genome that control transcription but are not themselves transcribed. We will encounter some exceptions to our definition of a gene - surprisingly, there is no definition that is entirely satisfactory." ::"A gene is a DNA sequence that codes for a diffusible product. This product may be protein (as is the case in the majority of genes) or may be RNA (as is the case of genes that code for tRNA and rRNA). The crucial feature is that the product diffuses away from its site of synthesis to act elsewhere." The important parts of such definitions are: (1) that a gene corresponds to a transcription unit; (2) that genes produce both mRNA and noncoding RNAs; and (3) regulatory sequences control gene expression but are not part of the gene itself. However, there's one other important part of the definition and it is emphasized in Kostas Kampourakis' book "Making Sense of Genes." ::"Therefore in this book I will consider genes as DNA sequences encoding information for functional products, be it proteins or RNA molecles. With 'encoding information,' I mean that the DNA sequence is used as a template for the production of an RNA molecule or a protein that performs some function.' The emphasis on function is essential because there are stretches of DNA that produce non-functional transcripts and they don't qualify as genes. These include obvious examples such as transcribed pseudogenes as well as less obvious examples such as junk RNA produced as noise due to transcription errors. In order to qualify as a true gene, by this definition, one has to prove that the transcript has a biological function. Early speculations on the size of a typical gene were based on high resolution genetic mapping and on the size of proteins and RNA molecules. A length of 1500 base pairs seemed reasonable at the time (1965). This was based on the idea that the gene was the DNA that was directly responsible for production of the functional product. The discovery of introns in the 1970s meant that many eukaryotic genes were much larger than the size of the functional product would imply. Typical mammalian protein-coding genes, for example, are about 62,000 base pairs in length (transcribed region) and since there are about 20,000 of them they occupy about 35-40% of the mammalian genome (including the human genome). In spite of the fact that both protein-coding genes and noncoding genes have been known for more than 50 years, there are still a number of textbooks, websites, and scientific publications that define a gene as a DNA sequence that specifies a protein. In other words, the definition is restricted to protein-coding genes. Here's an example from a recent article in American Scientist. ::What Is a Gene, Really? ::... to truly assess the potential significance of de novo genes, we relied on a strict definition of the word "gene" with which nearly every expert can agree. First, in order for a nucleotide sequence to be considered a true gene, an open reading frame (ORF) must be present. The ORF can be thought of as the "gene itself"; it begins with a starting mark common for every gene and ends with one of three possible finish line signals. One of the key enzymes in this process, the RNA polymerase, zips along the strand of DNA like a train on a monorail, transcribing it into its messenger RNA form. This point brings us to our second important criterion: A true gene is one that is both transcribed and translated. That is, a true gene is first used as a template to make transient messenger RNA, which is then translated into a protein. This restricted definition is so common that it has spawned many recent articles that criticize this "standard definition" and call for a new expanded definition that includes noncoding genes. However, this so-called "new" definition has been around for more than half a century and it's not clear why some modern writers are ignoring noncoding genes. There are exceptions to the standard definition of a gene; for example, some viruses have an RNA genome. The one important exception concerns bacterialoperon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splic ...

s where a contiguous stretch of DNA containing multiple protein-coding regions is transcribed into one large mRNA. Scientists usually refer to each of the coding regions as separate genes in this case. The only significant controversy over the definition of a gene is whether to include the regulatory sequences that control transcription of the gene. The general consensus among scientists is that regulatory elements control the expression of a gene but are not part of the gene.

History

Discovery of discrete inherited units

The existence of discrete inheritable units was first suggested byGregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, Augustinians, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thomas' Abbey in Br� ...

(1822–1884). From 1857 to 1864, in Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

, Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

(today's Czech Republic), he studied inheritance patterns in 8000 common edible pea plant

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the flowering plant species ''Pisum sativum''. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and d ...

s, tracking distinct traits from parent to offspring. He described these mathematically as 2n combinations where n is the number of differing characteristics in the original peas. Although he did not use the term ''gene'', he explained his results in terms of discrete inherited units that give rise to observable physical characteristics. This description prefigured Wilhelm Johannsen

Wilhelm Johannsen (3 February 1857 – 11 November 1927) was a Danish pharmacist, botanist, plant physiologist, and geneticist. He is best known for coining the terms gene, phenotype and genotype, and for his 1903 "pure line" experiments in gen ...

's distinction between genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

(the genetic material of an organism) and phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

(the observable traits of that organism). Mendel was also the first to demonstrate independent assortment

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularize ...

, the distinction between dominant and recessive

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and t ...

traits, the distinction between a heterozygote

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

and homozygote

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

, and the phenomenon of discontinuous inheritance.

Prior to Mendel's work, the dominant theory of heredity was one of blending inheritance

Blending may refer to:

* The process of mixing in process engineering

* Mixing paints to achieve a greater range of colors

* Blending (alcohol production), a technique to produce alcoholic beverages by mixing different brews

* Blending (linguist ...

, which suggested that each parent contributed fluids to the fertilization process and that the traits of the parents blended and mixed to produce the offspring. Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

developed a theory of inheritance he termed pangenesis

Pangenesis was Charles Darwin's hypothetical mechanism for heredity, in which he proposed that each part of the body continually emitted its own type of small organic particles called gemmules that aggregated in the gonads, contributing herita ...

, from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

pan ("all, whole") and genesis ("birth") / genos ("origin"). Darwin used the term ''gemmule

Gemmules are internal buds found in sponges and are involved in asexual reproduction. It is an asexually reproduced mass of cells, that is capable of developing into a new organism i.e., an adult sponge.

Role in asexual reproduction

Asexual ...

'' to describe hypothetical particles that would mix during reproduction.

Mendel's work went largely unnoticed after its first publication in 1866, but was rediscovered in the late 19th century by Hugo de Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries () (16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware of ...

, Carl Correns

Carl Erich Correns (19 September 1864 – 14 February 1933) was a German botanist and geneticist notable primarily for his independent discovery of the principles of heredity, which he achieved simultaneously but independently of the botanist ...

, and Erich von Tschermak Erich Tschermak, Edler von Seysenegg (15 November 1871 – 11 October 1962) was an Austrian agronomist who developed several new disease-resistant crops, including wheat-rye and oat hybrids. He was a son of the Moravia-born mineralogist Gustav ...

, who (claimed to have) reached similar conclusions in their own research. Specifically, in 1889, Hugo de Vries published his book ''Intracellular Pangenesis'', Translated in 1908 from German to English by Open Court Publishing Co., Chicago, 1910 in which he postulated that different characters have individual hereditary carriers and that inheritance of specific traits in organisms comes in particles. De Vries called these units "pangenes" (''Pangens'' in German), after Darwin's 1868 pangenesis theory.

Twenty years later, in 1909, Wilhelm Johannsen

Wilhelm Johannsen (3 February 1857 – 11 November 1927) was a Danish pharmacist, botanist, plant physiologist, and geneticist. He is best known for coining the terms gene, phenotype and genotype, and for his 1903 "pure line" experiments in gen ...

introduced the term 'gene' and in 1906, William Bateson

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscove ...

, that of 'genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

' while Eduard Strasburger

Eduard Adolf Strasburger (1 February 1844 – 18 May 1912) was a Polish-German professor and one of the most famous botanists of the 19th century. He discovered mitosis in plants.

Life

Eduard Strasburger was born in Warsaw, Congress Poland, the ...

, amongst others, still used the term 'pangene' for the fundamental physical and functional unit of heredity.

Discovery of DNA

Advances in understanding genes and inheritance continued throughout the 20th century. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was shown to be the molecular repository of genetic information by experiments in the 1940s to 1950s. Reprint: The structure of DNA was studied byRosalind Franklin

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (25 July 192016 April 1958) was a British chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work was central to the understanding of the molecular structures of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA (ribonucleic acid), viruses, co ...

and Maurice Wilkins

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist and Nobel laureate whose research spanned multiple areas of physics and biophysics, contributing to the scientific understanding o ...

using X-ray crystallography

X-ray crystallography is the experimental science determining the atomic and molecular structure of a crystal, in which the crystalline structure causes a beam of incident X-rays to diffract into many specific directions. By measuring the angles ...

, which led James D. Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Watson, Crick and ...

and Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical struc ...

to publish a model of the double-stranded DNA molecule whose paired nucleotide base

Nucleobases, also known as ''nitrogenous bases'' or often simply ''bases'', are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which, in turn, are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic b ...

s indicated a compelling hypothesis for the mechanism of genetic replication.

In the early 1950s the prevailing view was that the genes in a chromosome acted like discrete entities, indivisible by recombination and arranged like beads on a string. The experiments of Benzer using mutant

In biology, and especially in genetics, a mutant is an organism or a new genetic character arising or resulting from an instance of mutation, which is generally an alteration of the DNA sequence of the genome or chromosome of an organism. It ...

s defective in the rII region of bacteriophage T4 (1955–1959) showed that individual genes have a simple linear structure and are likely to be equivalent to a linear section of DNA.

Collectively, this body of research established the central dogma of molecular biology

The central dogma of molecular biology is an explanation of the flow of genetic information within a biological system. It is often stated as "DNA makes RNA, and RNA makes protein", although this is not its original meaning. It was first stated by ...

, which states that protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s are translated from RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

, which is transcribed from DNA. This dogma has since been shown to have exceptions, such as reverse transcription

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to replicate their genomes, ...

in retrovirus

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a DNA copy of its RNA genome into the DNA of a host cell that it invades, thus changing the genome of that cell. Once inside the host cell's cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptase ...

es. The modern study of genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

at the level of DNA is known as molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

.

In 1972, Walter Fiers

Walter Fiers (31 January 1931 in Ypres, West Flanders – 28 July 2019 in Destelbergen) was a Belgian molecular biologist.

He obtained a degree of Engineer for Chemistry and Agricultural Industries at the University of Ghent in 1954, and started ...

and his team were the first to determine the sequence of a gene: that of Bacteriophage MS2

Bacteriophage MS2 (''Emesvirus zinderi''), commonly called MS2, is an icosahedral, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus that infects the bacterium ''Escherichia coli'' and other members of the Enterobacteriaceae. MS2 is a member of a family ...

coat protein. The subsequent development of chain-termination DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

in 1977 by Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger (; 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was an English biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other p ...

improved the efficiency of sequencing and turned it into a routine laboratory tool. An automated version of the Sanger method was used in early phases of the Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

.

Modern synthesis and its successors

The theories developed in the early 20th century to integrateMendelian genetics

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biology, biological Heredity, inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, an ...

with Darwinian evolution

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that ...

are called the modern synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and s ...

, a term introduced by Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist, and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century modern synthesis. ...

.

Evolutionary biologists have subsequently modified this concept, such as George C. Williams' gene-centric view of evolution

With gene defined as "not just one single physical bit of DNA utall replicas of a particular bit of DNA distributed throughout the world", the gene-centered view of evolution, gene's eye view, gene selection theory, or selfish gene theory ...

. He proposed an evolutionary concept of the gene as a unit

Unit may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* UNIT, a fictional military organization in the science fiction television series ''Doctor Who''

* Unit of action, a discrete piece of action (or beat) in a theatrical presentation

Music

* ''Unit'' (alb ...

of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

with the definition: "that which segregates and recombines with appreciable frequency." In this view, the molecular gene ''transcribes'' as a unit, and the evolutionary gene ''inherits'' as a unit. Related ideas emphasizing the centrality of genes in evolution were popularized by Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins (born 26 March 1941) is a British evolutionary biologist and author. He is an emeritus fellow of New College, Oxford and was Professor for Public Understanding of Science in the University of Oxford from 1995 to 2008. An ath ...

.

Molecular basis

DNA

The vast majority of organisms encode their genes in long strands of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). DNA consists of achain

A chain is a serial assembly of connected pieces, called links, typically made of metal, with an overall character similar to that of a rope in that it is flexible and curved in compression but linear, rigid, and load-bearing in tension. A c ...

made from four types of nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

subunits, each composed of: a five-carbon sugar ( 2-deoxyribose), a phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phospho ...

group, and one of the four bases adenine

Adenine () ( symbol A or Ade) is a nucleobase (a purine derivative). It is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The three others are guanine, cytosine and thymine. Its derivati ...

, cytosine

Cytosine () ( symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleobases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attached (an am ...

, guanine

Guanine () ( symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleobases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside is called ...

, and thymine

Thymine () ( symbol T or Thy) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidine nu ...

.

Two chains of DNA twist around each other to form a DNA double helix

A double is a look-alike or doppelgänger; one person or being that resembles another.

Double, The Double or Dubble may also refer to:

Film and television

* Double (filmmaking), someone who substitutes for the credited actor of a character

* ...

with the phosphate-sugar backbone spiraling around the outside, and the bases pointing inwards with adenine base pairing

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

to thymine and guanine to cytosine. The specificity of base pairing occurs because adenine and thymine align to form two hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a ...

s, whereas cytosine and guanine form three hydrogen bonds. The two strands in a double helix must, therefore, be complementary

A complement is something that completes something else.

Complement may refer specifically to:

The arts

* Complement (music), an interval that, when added to another, spans an octave

** Aggregate complementation, the separation of pitch-class ...

, with their sequence of bases matching such that the adenines of one strand are paired with the thymines of the other strand, and so on.

Due to the chemical composition of the pentose

In chemistry, a pentose is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) with five carbon atoms. The chemical formula of many pentoses is , and their molecular weight is 150.13 g/mol.hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

group on the deoxyribose

Deoxyribose, or more precisely 2-deoxyribose, is a monosaccharide with idealized formula H−(C=O)−(CH2)−(CHOH)3−H. Its name indicates that it is a deoxy sugar, meaning that it is derived from the sugar ribose by loss of a hydroxy group. D ...

; this is known as the 3' end of the molecule. The other end contains an exposed phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phospho ...

group; this is the 5' end. The two strands of a double-helix run in opposite directions. Nucleic acid synthesis, including DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

and transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

occurs in the 5'→3' direction, because new nucleotides are added via a dehydration reaction

In chemistry, a dehydration reaction is a chemical reaction that involves the loss of water from the reacting molecule or ion. Dehydration reactions are common processes, the reverse of a hydration reaction.

Dehydration reactions in organic che ...

that uses the exposed 3' hydroxyl as a nucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

.

The expression

Expression may refer to:

Linguistics

* Expression (linguistics), a word, phrase, or sentence

* Fixed expression, a form of words with a specific meaning

* Idiom, a type of fixed expression

* Metaphorical expression, a particular word, phrase, o ...

of genes encoded in DNA begins by transcribing

Transcription in the linguistic sense is the systematic representation of spoken language in written form. The source can either be utterances (''speech'' or ''sign language'') or preexisting text in another writing system.

Transcription shoul ...

the gene into RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

, a second type of nucleic acid that is very similar to DNA, but whose monomers contain the sugar ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally-occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this compo ...

rather than deoxyribose

Deoxyribose, or more precisely 2-deoxyribose, is a monosaccharide with idealized formula H−(C=O)−(CH2)−(CHOH)3−H. Its name indicates that it is a deoxy sugar, meaning that it is derived from the sugar ribose by loss of a hydroxy group. D ...

. RNA also contains the base uracil

Uracil () (symbol U or Ura) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid RNA. The others are adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). In RNA, uracil binds to adenine via two hydrogen bonds. In DNA, the uracil nucleobase is replaced by ...

in place of thymine

Thymine () ( symbol T or Thy) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidine nu ...

. RNA molecules are less stable than DNA and are typically single-stranded. Genes that encode proteins are composed of a series of three-nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

sequences called codon

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

s, which serve as the "words" in the genetic "language". The genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

specifies the correspondence during protein translation

In molecular biology and genetics, translation is the process in which ribosomes in the cytoplasm or endoplasmic reticulum synthesize proteins after the process of transcription of DNA to RNA in the cell's nucleus. The entire process is ...

between codons and amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s. The genetic code is nearly the same for all known organisms.

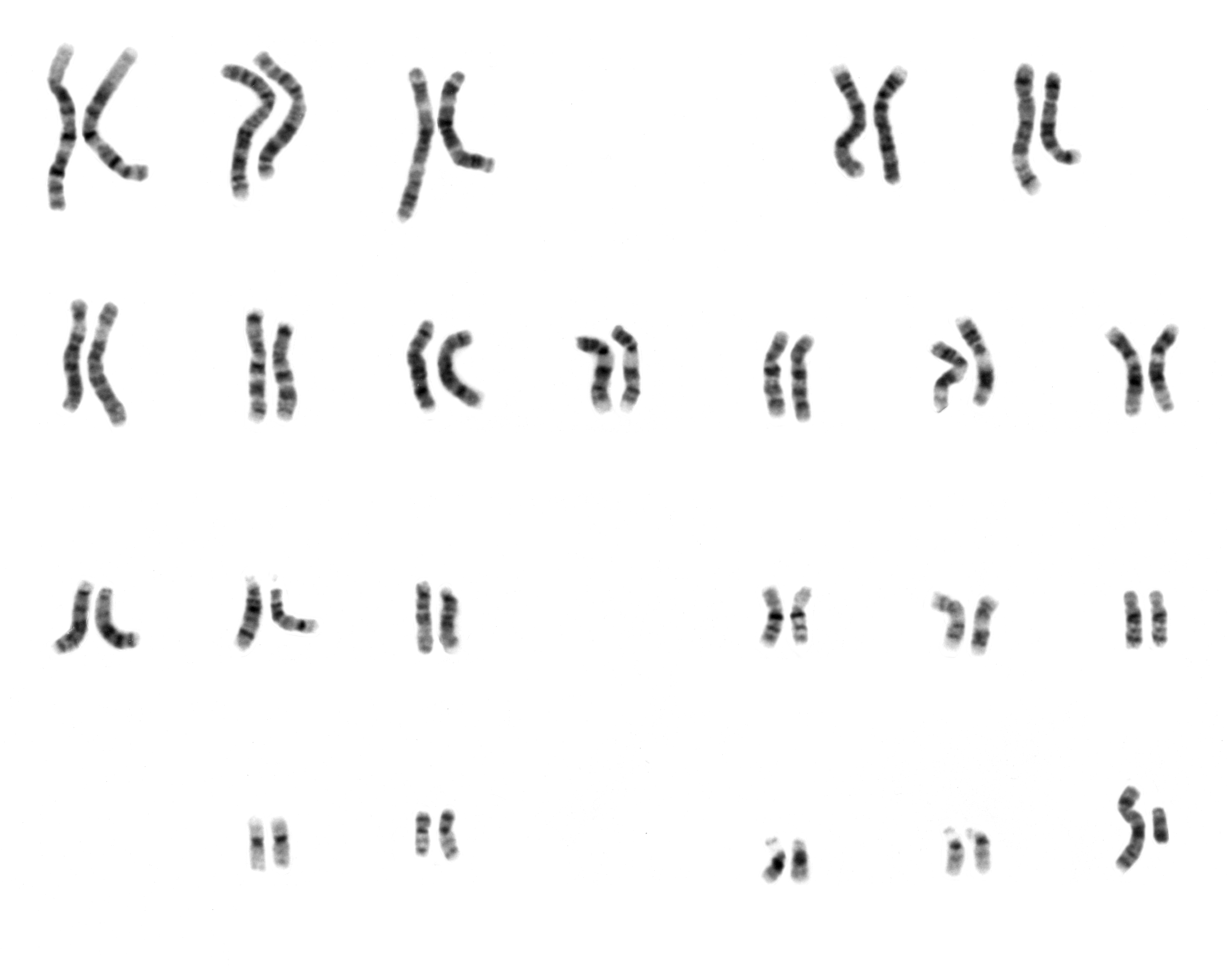

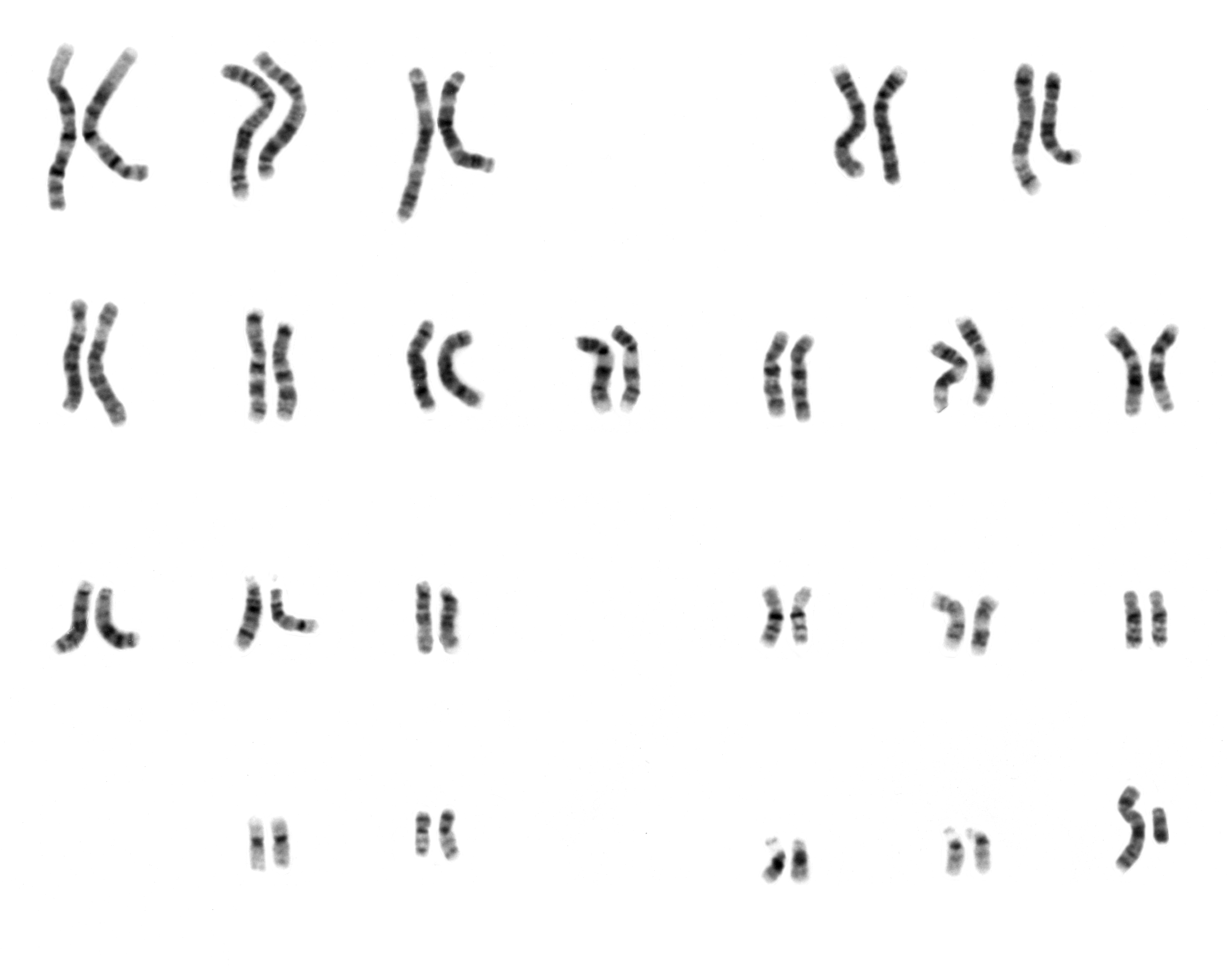

Chromosomes

The total complement of genes in an organism or cell is known as its

The total complement of genes in an organism or cell is known as its genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

, which may be stored on one or more chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

s. A chromosome consists of a single, very long DNA helix on which thousands of genes are encoded. The region of the chromosome at which a particular gene is located is called its locus

Locus (plural loci) is Latin for "place". It may refer to:

Entertainment

* Locus (comics), a Marvel Comics mutant villainess, a member of the Mutant Liberation Front

* ''Locus'' (magazine), science fiction and fantasy magazine

** ''Locus Award' ...

. Each locus contains one allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

of a gene; however, members of a population may have different alleles at the locus, each with a slightly different gene sequence.

The majority of eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

genes are stored on a set of large, linear chromosomes. The chromosomes are packed within the nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

in complex with storage proteins called histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn are wr ...

s to form a unit called a nucleosome

A nucleosome is the basic structural unit of DNA packaging in eukaryotes. The structure of a nucleosome consists of a segment of DNA wound around eight histone proteins and resembles thread wrapped around a spool. The nucleosome is the fundamen ...

. DNA packaged and condensed in this way is called chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important roles in r ...

. The manner in which DNA is stored on the histones, as well as chemical modifications of the histone itself, regulate whether a particular region of DNA is accessible for gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. The ...

. In addition to genes, eukaryotic chromosomes contain sequences involved in ensuring that the DNA is copied without degradation of end regions and sorted into daughter cells during cell division: replication origin

The origin of replication (also called the replication origin) is a particular sequence in a genome at which replication is initiated. Propagation of the genetic material between generations requires timely and accurate duplication of DNA by semi ...

s, telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes. Although there are different architectures, telomeres, in a broad sense, are a widespread genetic feature mos ...

s and the centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers a ...

. Replication origins are the sequence regions where DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

is initiated to make two copies of the chromosome. Telomeres are long stretches of repetitive sequences that cap the ends of the linear chromosomes and prevent degradation of coding and regulatory regions during DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

. The length of the telomeres decreases each time the genome is replicated and has been implicated in the aging

Ageing ( BE) or aging ( AE) is the process of becoming older. The term refers mainly to humans, many other animals, and fungi, whereas for example, bacteria, perennial plants and some simple animals are potentially biologically immortal. In ...

process. The centromere is required for binding spindle fibres to separate sister chromatids into daughter cells during cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

.

Prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s (bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

and archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

) typically store their genomes on a single large, circular chromosome

A circular chromosome is a chromosome in bacteria, archaea, mitochondria, and chloroplasts, in the form of a molecule of circular DNA, unlike the linear chromosome of most eukaryotes.

Most prokaryote chromosomes contain a circular DNA molecu ...

. Similarly, some eukaryotic organelles

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

contain a remnant circular chromosome with a small number of genes. Prokaryotes sometimes supplement their chromosome with additional small circles of DNA called plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; how ...

s, which usually encode only a few genes and are transferable between individuals. For example, the genes for antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistance. ...

are usually encoded on bacterial plasmids and can be passed between individual cells, even those of different species, via horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

.

Whereas the chromosomes of prokaryotes are relatively gene-dense, those of eukaryotes often contain regions of DNA that serve no obvious function. Simple single-celled eukaryotes have relatively small amounts of such DNA, whereas the genomes of complex multicellular organism

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- ...

s, including humans, contain an absolute majority of DNA without an identified function. This DNA has often been referred to as "junk DNA

Non-coding DNA (ncDNA) sequences are components of an organism's DNA that do not genetic code, encode protein sequences. Some non-coding DNA is Transcription (genetics), transcribed into functional non-coding RNA molecules (e.g. transfer RNA, micro ...

". However, more recent analyses suggest that, although protein-coding DNA makes up barely 2% of the human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as DNA within the 23 chromosome pairs in cell nuclei and in a small DNA molecule found within individual mitochondria. These are usually treated separately as the n ...

, about 80% of the bases in the genome may be expressed, so the term "junk DNA" may be a misnomer.

Structure and function

Structure

The structure of a protein-coding gene consists of many elements of which the actual protein coding sequence is often only a small part. These include introns and untranslated regions of the mature mRNA. Noncoding genes can also contain introns that are removed during processing to produce the mature functional RNA. All genes are associated withregulatory sequence

A regulatory sequence is a segment of a nucleic acid molecule which is capable of increasing or decreasing the expression of specific genes within an organism. Regulation of gene expression is an essential feature of all living organisms and vir ...

s that are required for their expression. First, genes require a promoter sequence. The promoter is recognized and bound by transcription factors

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The func ...

that recruit and help RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the ...

bind to the region to initiate transcription. The recognition typically occurs as a consensus sequence

In molecular biology and bioinformatics, the consensus sequence (or canonical sequence) is the calculated order of most frequent residues, either nucleotide or amino acid, found at each position in a sequence alignment. It serves as a simplified r ...

like the TATA box

In molecular biology, the TATA box (also called the Goldberg–Hogness box) is a sequence of DNA found in the core promoter region of genes in archaea and eukaryotes. The bacterial homolog of the TATA box is called the Pribnow box which has ...

. A gene can have more than one promoter, resulting in messenger RNAs (mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

) that differ in how far they extend in the 5' end. Highly transcribed genes have "strong" promoter sequences that form strong associations with transcription factors, thereby initiating transcription at a high rate. Others genes have "weak" promoters that form weak associations with transcription factors and initiate transcription less frequently. Eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

promoter regions are much more complex and difficult to identify than prokaryotic

A prokaryote () is a Unicellular organism, single-celled organism that lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:πρό#Ancient Greek, πρό (, 'before') a ...

promoters.

Additionally, genes can have regulatory regions many kilobases upstream or downstream of the gene that alter expression. These act by binding to transcription factors which then cause the DNA to loop so that the regulatory sequence (and bound transcription factor) become close to the RNA polymerase binding site. For example, enhancers

In genetics, an enhancer is a short (50–1500 bp) region of DNA that can be bound by proteins ( activators) to increase the likelihood that transcription of a particular gene will occur. These proteins are usually referred to as transcription ...

increase transcription by binding an activator protein which then helps to recruit the RNA polymerase to the promoter; conversely silencers bind repressor

In molecular genetics, a repressor is a DNA- or RNA-binding protein that inhibits the expression of one or more genes by binding to the operator or associated silencers. A DNA-binding repressor blocks the attachment of RNA polymerase to the ...

proteins and make the DNA less available for RNA polymerase.

The mature messenger RNA produced from protein-coding genes contains untranslated regions

In molecular genetics, an untranslated region (or UTR) refers to either of two sections, one on each side of a coding sequence on a strand of mRNA. If it is found on the 5' side, it is called the 5' UTR (or leader sequence), or if it is foun ...

at both ends which contain binding sites for ribosomes

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to f ...

, RNA-binding protein

RNA-binding proteins (often abbreviated as RBPs) are proteins that bind to the double or single stranded RNA in cells and participate in forming ribonucleoprotein complexes.

RBPs contain various structural motifs, such as RNA recognition motif ( ...

s, miRNA

MicroRNA (miRNA) are small, single-stranded, non-coding RNA molecules containing 21 to 23 nucleotides. Found in plants, animals and some viruses, miRNAs are involved in RNA silencing and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. miRN ...

, as well as terminator

Terminator may refer to:

Science and technology

Genetics

* Terminator (genetics), the end of a gene for transcription

* Terminator technology, proposed methods for restricting the use of genetically modified plants by causing second generation s ...

, and start

Start can refer to multiple topics:

*Takeoff, the phase of flight where an aircraft transitions from moving along the ground to flying through the air

* Starting lineup in sports

*Standing start, and rolling start, in an auto race

Acronyms

*St ...

and stop codons. In addition, most eukaryotic open reading frame

In molecular biology, open reading frames (ORFs) are defined as spans of DNA sequence between the start and stop codons. Usually, this is considered within a studied region of a prokaryotic DNA sequence, where only one of the six possible readin ...

s contain untranslated introns

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e. a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gene. ...

, which are removed and exons

An exon is any part of a gene that will form a part of the final mature RNA produced by that gene after introns have been removed by RNA splicing. The term ''exon'' refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene and to the corresponding sequence ...

, which are connected together in a process known as RNA splicing

RNA splicing is a process in molecular biology where a newly-made precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) transcript is transformed into a mature messenger RNA (mRNA). It works by removing all the introns (non-coding regions of RNA) and ''splicing'' b ...

. Finally, the ends of gene transcripts are defined by cleavage and polyadenylation (CPA) sites, where newly produced pre-mRNA gets cleaved and a string of ~200 adenosine monophosphates is added at the 3' end. The poly(A)

Polyadenylation is the addition of a poly(A) tail to an RNA transcript, typically a messenger RNA (mRNA). The poly(A) tail consists of multiple adenosine monophosphates; in other words, it is a stretch of RNA that has only adenine bases. In euka ...

tail protects mature mRNA from degradation and has other functions, affecting translation, localization, and transport of the transcript from the nucleus. Splicing, followed by CPA, generate the final mature mRNA

Mature messenger RNA, often abbreviated as mature mRNA is a eukaryotic RNA transcript that has been spliced and processed and is ready for translation in the course of protein synthesis. Unlike the eukaryotic RNA immediately after transcription k ...

, which encodes the protein or RNA product. Although the general mechanisms defining locations of human genes are known, identification of the exact factors regulating these cellular processes is an area of active research. For example, known sequence features in the 3'-UTR

In molecular genetics, the three prime untranslated region (3′-UTR) is the section of messenger RNA (mRNA) that immediately follows the translation termination codon. The 3′-UTR often contains regulatory regions that post-transcriptionally ...

can only explain half of all human gene ends.

Many noncoding genes in eukaryotes have different transcription termination mechanisms and they do not have pol(A) tails.

Many prokaryotic genes are organized into operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splic ...

s, with multiple protein-coding sequences that are transcribed as a unit. The genes in an operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splic ...

are transcribed as a continuous messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

, referred to as a polycistronic mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the ...

. The term cistron

A cistron is an alternative term for "gene". The word cistron is used to emphasize that genes exhibit a specific behavior in a cis-trans test; distinct positions (or loci) within a genome are cistronic.

History

The words ''cistron'' and ''gene ...

in this context is equivalent to gene. The transcription of an operon's mRNA is often controlled by a repressor

In molecular genetics, a repressor is a DNA- or RNA-binding protein that inhibits the expression of one or more genes by binding to the operator or associated silencers. A DNA-binding repressor blocks the attachment of RNA polymerase to the ...

that can occur in an active or inactive state depending on the presence of specific metabolites. When active, the repressor binds to a DNA sequence at the beginning of the operon, called the operator region, and represses transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

of the operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splic ...

; when the repressor is inactive transcription of the operon can occur (see e.g. Lac operon

The ''lactose'' operon (''lac'' operon) is an operon required for the transport and metabolism of lactose in ''E. coli'' and many other enteric bacteria. Although glucose is the preferred carbon source for most bacteria, the ''lac'' operon allows ...

). The products of operon genes typically have related functions and are involved in the same regulatory network.

Functional definitions

Defining exactly what section of a DNA sequence comprises a gene is difficult.Regulatory regions

A regulatory sequence is a segment of a nucleic acid molecule which is capable of increasing or decreasing the expression of specific genes within an organism. Regulation of gene expression is an essential feature of all living organisms and vir ...

of a gene such as enhancers

In genetics, an enhancer is a short (50–1500 bp) region of DNA that can be bound by proteins ( activators) to increase the likelihood that transcription of a particular gene will occur. These proteins are usually referred to as transcription ...

do not necessarily have to be close to the coding sequence

The coding region of a gene, also known as the coding sequence (CDS), is the portion of a gene's DNA or RNA that codes for protein. Studying the length, composition, regulation, splicing, structures, and functions of coding regions compared to no ...

on the linear molecule because the intervening DNA can be looped out to bring the gene and its regulatory region into proximity. Similarly, a gene's introns can be much larger than its exons. Regulatory regions can even be on entirely different chromosomes and operate ''in trans'' to allow regulatory regions on one chromosome to come in contact with target genes on another chromosome.

Early work in molecular genetics suggested the concept that one gene makes one protein. This concept (originally called the one gene-one enzyme hypothesis

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1 ...

) emerged from an influential 1941 paper by George Beadle

George Wells Beadle (October 22, 1903 – June 9, 1989) was an American geneticist. In 1958 he shared one-half of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Edward Tatum for their discovery of the role of genes in regulating biochemical even ...

and Edward Tatum

Edward Lawrie Tatum (December 14, 1909 – November 5, 1975) was an American geneticist. He shared half of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1958 with George Beadle for showing that genes control individual steps in metabolism. The o ...

on experiments with mutants of the fungus ''Neurospora crassa

''Neurospora crassa'' is a type of red bread mold of the phylum Ascomycota. The genus name, meaning "nerve spore" in Greek, refers to the characteristic striations on the spores. The first published account of this fungus was from an infestation ...

''. Norman Horowitz

Norman Harold Horowitz (March 19, 1915 – June 1, 2005) was a geneticist at Caltech who achieved national fame as the scientist who devised experiments to determine whether life might exist on Mars. His experiments were carried out by the Vikin ...

, an early colleague on the ''Neurospora'' research, reminisced in 2004 that "these experiments founded the science of what Beadle and Tatum called ''biochemical genetics''. In actuality they proved to be the opening gun in what became molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

and all the developments that have followed from that". The one gene-one protein concept has been refined since the discovery of genes that can encode multiple proteins by alternative splicing

Alternative splicing, or alternative RNA splicing, or differential splicing, is an alternative splicing process during gene expression that allows a single gene to code for multiple proteins. In this process, particular exons of a gene may be ...

and coding sequences split in short section across the genome whose mRNAs are concatenated by trans-splicing

''Trans''-splicing is a special form of RNA processing where exons from two different primary RNA transcripts are joined end to end and ligated. It is usually found in eukaryotes and mediated by the spliceosome, although some bacteria and archaea ...

.

A broad operational definition is sometimes used to encompass the complexity of these diverse phenomena, where a gene is defined as a union of genomic sequences encoding a coherent set of potentially overlapping functional products. This definition categorizes genes by their functional products (proteins or RNA) rather than their specific DNA loci, with regulatory elements classified as ''gene-associated'' regions.

Overlap between genes

It is also possible for genes to overlap the same DNA sequence and be considered distinct butoverlapping gene

An overlapping gene (or OLG) is a gene whose expressible Nucleic acid sequence, nucleotide sequence partially overlaps with the expressible nucleotide sequence of another gene. In this way, a nucleotide sequence may make a contribution to the func ...

s. The current definition of an overlapping gene is different across eukaryotes, prokaryotes, and viruses. In Eukaryotes they have recently been defined as "when at least one nucleotide is shared between the outermost boundaries of the primary transcript

A primary transcript is the single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) product synthesized by transcription of DNA, and processed to yield various mature RNA products such as mRNAs, tRNAs, and rRNAs. The primary transcripts designated to be mRNAs a ...

s of two or more genes, such that a DNA base mutation at the point of overlap would affect transcripts of all genes involved in the overlap." In Prokaryotes and Viruses they have recently been defined as "when the coding sequences of two genes share a nucleotide either on the same or opposite strands."

Gene expression

In all organisms, two steps are required to read the information encoded in a gene's DNA and produce the protein it specifies. First, the gene's DNA is '' transcribed'' to messenger RNA (mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

). Second, that mRNA is ''translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

'' to protein. RNA-coding genes must still go through the first step, but are not translated into protein. The process of producing a biologically functional molecule of either RNA or protein is called gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. The ...

, and the resulting molecule is called a gene product

A gene product is the biochemical material, either RNA or protein, resulting from expression of a gene. A measurement of the amount of gene product is sometimes used to infer how active a gene is. Abnormal amounts of gene product can be correlated ...

.

Genetic code

genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

. Sets of three nucleotides, known as codon

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

s, each correspond to a specific amino acid. The principle that three sequential bases of DNA code for each amino acid was demonstrated in 1961 using frameshift mutations in the rIIB gene of bacteriophage T4 (see Crick, Brenner et al. experiment The Crick, Brenner et al. experiment (1961) was a scientific experiment performed by Francis Crick, Sydney Brenner, Leslie Barnett and R.J. Watts-Tobin.

It was a key experiment in the development of what is now known as molecular biology and led t ...

).

Additionally, a "start codon

The start codon is the first codon of a messenger RNA (mRNA) transcript translated by a ribosome. The start codon always codes for methionine in eukaryotes and Archaea and a N-formylmethionine (fMet) in bacteria, mitochondria and plastids. The ...

", and three "stop codon

In molecular biology (specifically protein biosynthesis), a stop codon (or termination codon) is a codon (nucleotide triplet within messenger RNA) that signals the termination of the translation process of the current protein. Most codons in me ...

s" indicate the beginning and end of the protein coding region

The coding region of a gene, also known as the coding sequence (CDS), is the portion of a gene's DNA or RNA that codes for protein. Studying the length, composition, regulation, splicing, structures, and functions of coding regions compared to n ...