Gastornis 1917 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Gastornis'' is an extinct

''Gastornis'' was first described in 1855 from a fragmentary skeleton. It was named after

''Gastornis'' was first described in 1855 from a fragmentary skeleton. It was named after

/ref> Additional bones of the first known species, ''G. parisiensis'', were found in the mid 1860s. Somewhat more complete specimens, this time referred to the new species ''G. eduardsii'' (now considered a synonym of ''G. parisiensis'') were found a decade later. The specimens found in the 1870s formed the basis for a widely circulated and reproduced skeletal restoration by Victor Lemoine, Lemoine. The skulls of these original ''Gastornis'' fossils were unknown except for nondescript fragments, and several bones used in Lemoine's illustration turned out to be those of other animals. Thus, the European bird was long reconstructed as a sort of gigantic crane-like bird. In 1874, the American

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

of large flightless bird

Flightless birds are birds that through evolution lost the ability to fly. There are over 60 extant species, including the well known ratites (ostriches, emu, cassowaries, rheas, and kiwi) and penguins. The smallest flightless bird is the In ...

s that lived during the mid Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), E ...

to mid Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

epochs of the Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; British English, also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period, geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million yea ...

period. Fossils have been found in Europe, Asia and North America, with the remains from North America originally assigned to the genus ''Diatryma''.

''Gastornis'' species were very large birds, and have traditionally been considered to be predators of small mammals. However, several lines of evidence, including the lack of hooked claws in known ''Gastornis'' footprints and studies of their beak structure and isotopic signature

An isotopic signature (also isotopic fingerprint) is a ratio of non-radiogenic ' stable isotopes', stable radiogenic isotopes, or unstable radioactive isotopes of particular elements in an investigated material. The ratios of isotopes in a sample ...

s of their bones have caused scientists to reinterpret these birds as herbivores that probably fed on tough plant material and seeds. ''Gastornis'' is generally agreed to be related to Galloanserae, the group containing waterfowl

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which in ...

and gamebirds

Galliformes is an order of heavy-bodied ground-feeding birds that includes turkeys, chickens, quail, and other landfowl. Gallinaceous birds, as they are called, are important in their ecosystems as seed dispersers and predators, and are often ...

.

History

''Gastornis'' was first described in 1855 from a fragmentary skeleton. It was named after

''Gastornis'' was first described in 1855 from a fragmentary skeleton. It was named after Gaston Planté

Gaston Planté (22 April 1834 – 21 May 1889) was a French physicist who invented the lead–acid battery in 1859. This type battery was developed as the first rechargeable electric battery marketed for commercial use and it is widely used in aut ...

, described as a "studious young man full of zeal", who had discovered the first fossils in clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

() formation deposits at Meudon

Meudon () is a municipality in the southwestern suburbs of Paris, France. It is in the département of Hauts-de-Seine. It is located from the center of Paris. The city is known for many historic monuments and some extraordinary trees. One of t ...

near Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

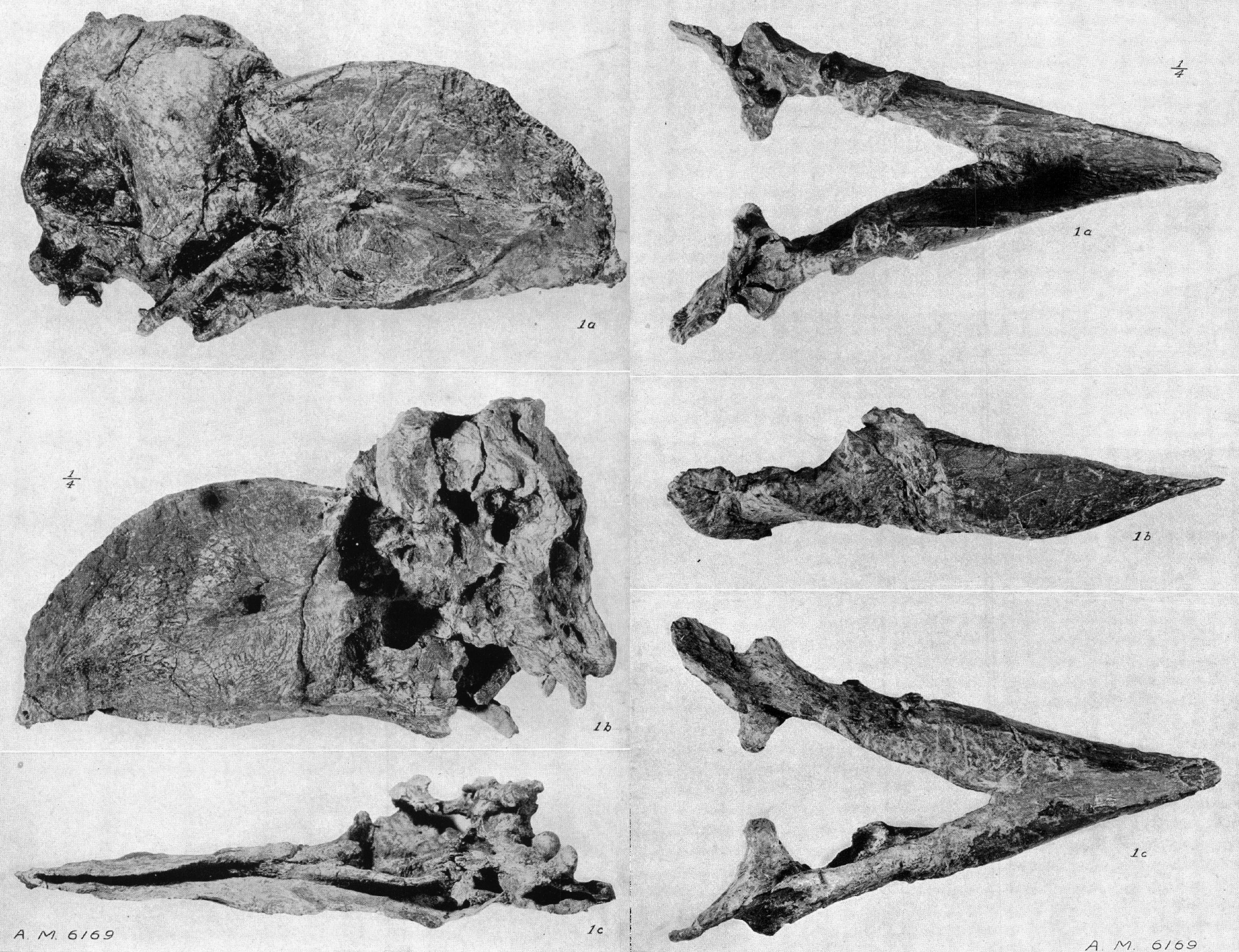

. The discovery was notable due to the large size of the specimens, and because, at the time, ''Gastornis'' represented one of the oldest known birds.Buffetaut, E., and Burrrraur, E. (1997). "New remains of the giant bird ''Gastornis'' from the Upper Paleocene of the eastern Paris Basin and the relationships between ''Gastornis'' and ''Diatryma''." ''N. Jb. Geol. Palâont. Mh.'', (3): 179-190/ref> Additional bones of the first known species, ''G. parisiensis'', were found in the mid 1860s. Somewhat more complete specimens, this time referred to the new species ''G. eduardsii'' (now considered a synonym of ''G. parisiensis'') were found a decade later. The specimens found in the 1870s formed the basis for a widely circulated and reproduced skeletal restoration by Victor Lemoine, Lemoine. The skulls of these original ''Gastornis'' fossils were unknown except for nondescript fragments, and several bones used in Lemoine's illustration turned out to be those of other animals. Thus, the European bird was long reconstructed as a sort of gigantic crane-like bird. In 1874, the American

paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontologist, comparative anatomist, herpetologist, and ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker family, Cope distinguished himself as a child prodigy interested ...

discovered another fragmentary set of fossils in the Wasatch Formation

The Wasatch Formation (Tw)Shroba & Scott, 2001, p.3 is an extensive highly fossiliferous geologic formation stretching across several basins in Idaho, Montana Wyoming, Utah and western Colorado.New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

. He considered them to belong to a distinct genus and species of giant ground bird, which, in 1876, he named ''Diatryma gigantea'' ( ), from Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

διάτρημα, ''diatrema'', meaning “through a hole”, referring to the large foramina (perforations) that penetrate some of the foot bones. A single gastornithid toe bone from New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

was described by Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among h ...

in 1894 and classified as the new genus and species ''Barornis regens'', but in 1911 it was recognized that this, too, could be considered a junior synonym of ''Diatryma'' (and therefore later ''Gastornis''). Additional fragmentary specimens were found in Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

in 1911 and assigned in 1913 to the new species ''Diatryma ajax'' (also now considered a synonym of ''G. gigantea''). In 1916, an American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

expedition to the Bighorn Basin

The Bighorn Basin is a plateau region and intermontane basin, approximately 100 miles (160 km) wide, in north-central Wyoming in the United States. It is bounded by the Absaroka Range on the west, the Pryor Mountains on the north, the Bighor ...

(Willwood Formation

The Willwood Formation is a sedimentary sequence deposited during the late Paleocene to early Eocene, or Clarkforkian, Wasatchian and Bridgerian in the NALMA classification.

After the description of ''Diatryma'', most new European specimens were referred to this genus instead of ''Gastornis''. However, after the initial discovery of ''Diatryma'', it soon became clear that it and ''Gastornis'' were so similar that the former could be considered a

''Gastornis'' is known from a large amount of fossil remains, but the clearest picture of the bird comes from a few nearly complete specimens of the species ''G. gigantea''. These were generally very large birds, with huge beaks and massive skulls superficially similar to the carnivorous South American "terror birds" (

''Gastornis'' is known from a large amount of fossil remains, but the clearest picture of the bird comes from a few nearly complete specimens of the species ''G. gigantea''. These were generally very large birds, with huge beaks and massive skulls superficially similar to the carnivorous South American "terror birds" (

A long-standing debate surrounding ''Gastornis'' is the interpretation of its diet. It has often been depicted as a predator of contemporary small mammals, which famously included the early horse ''

A long-standing debate surrounding ''Gastornis'' is the interpretation of its diet. It has often been depicted as a predator of contemporary small mammals, which famously included the early horse ''

Several sets of fossil footprints are suspected to belong to ''Gastornis''. One set of footprints was reported from late

Several sets of fossil footprints are suspected to belong to ''Gastornis''. One set of footprints was reported from late

The

The

''Gastornis'' fossils are known from across western Europe, the western United States, and central China. The earliest (Paleocene) fossils all come from Europe, and it is likely that the genus originated there. Europe in this epoch was an island continent, and ''Gastornis'' was the largest terrestrial tetrapod of the landmass. This offers parallels with the malagasy

''Gastornis'' fossils are known from across western Europe, the western United States, and central China. The earliest (Paleocene) fossils all come from Europe, and it is likely that the genus originated there. Europe in this epoch was an island continent, and ''Gastornis'' was the largest terrestrial tetrapod of the landmass. This offers parallels with the malagasy

junior synonym

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linna ...

of the latter. In fact, this similarity was recognized as early as 1884 by Elliott Coues

Elliott Ladd Coues (; September 9, 1842 – December 25, 1899) was an American army surgeon, historian, ornithologist, and author. He led surveys of the Arizona Territory, and later as secretary of the United States Geological and Geographic ...

, but this was debated by researchers throughout the 20th century. Meaningful comparisons between ''Gastornis'' and ''Diatryma'' were made more difficult by Lemoine's incorrect skeletal illustration, the composite nature of which was not discovered until the early 1980s. Following this, several authors began to recognize a greater degree of similarity between the European and North American birds, often placing both in the same order (Gastornithiformes) or even family (Gastornithidae). This newly recognized degree of similarity caused many scientists to tentatively accept their synonymy, pending a comprehensive review of the anatomy of these birds. Consequently, the correct scientific name of the genus is ''Gastornis''.

Description

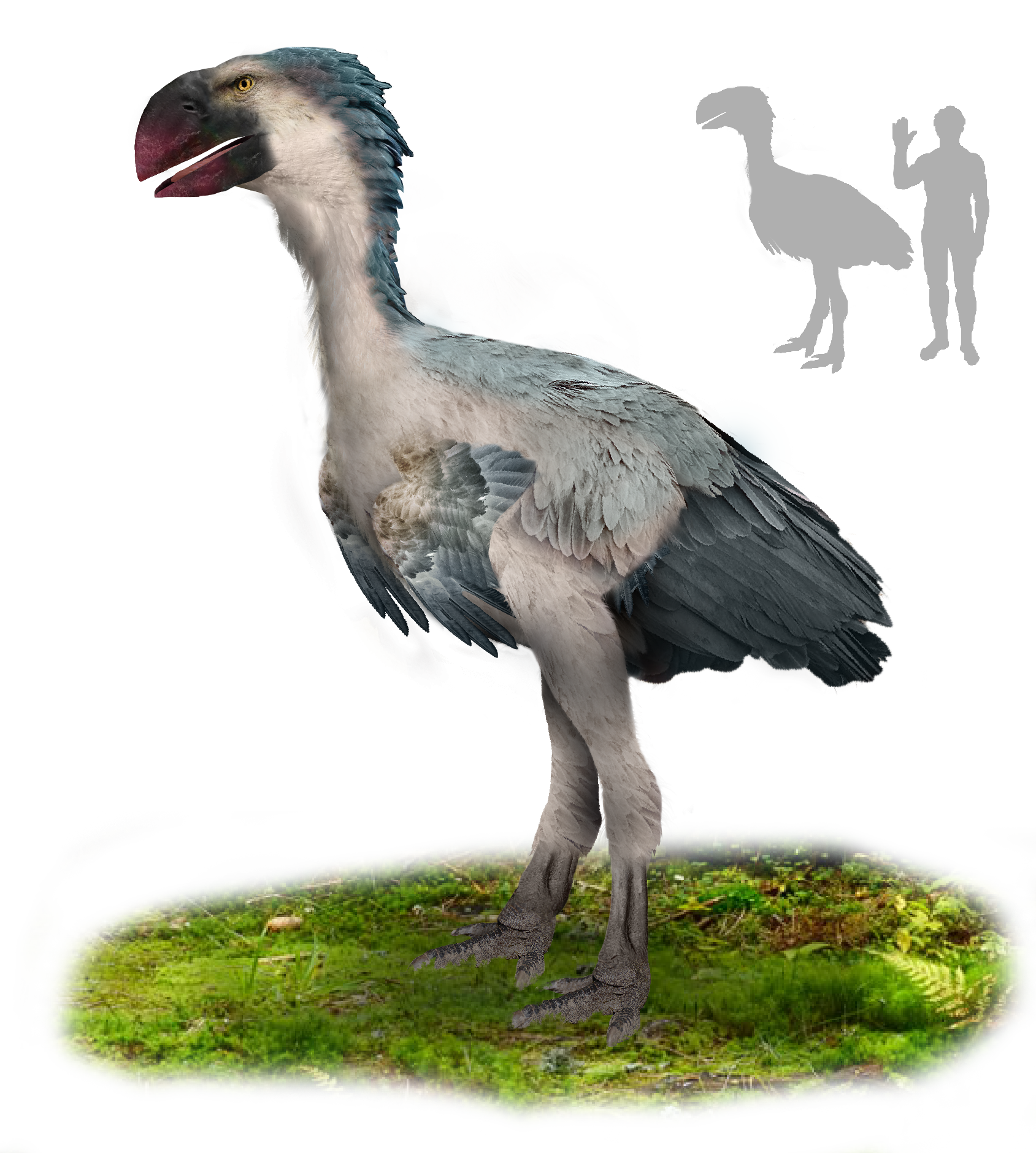

''Gastornis'' is known from a large amount of fossil remains, but the clearest picture of the bird comes from a few nearly complete specimens of the species ''G. gigantea''. These were generally very large birds, with huge beaks and massive skulls superficially similar to the carnivorous South American "terror birds" (

''Gastornis'' is known from a large amount of fossil remains, but the clearest picture of the bird comes from a few nearly complete specimens of the species ''G. gigantea''. These were generally very large birds, with huge beaks and massive skulls superficially similar to the carnivorous South American "terror birds" (phorusrhacids

Phorusrhacids, colloquially known as terror birds, are an extinct clade of large carnivorous flightless birds that were one of the largest species of apex predators in South America during the Cenozoic era; their conventionally accepted temporal ...

). The largest known species, ''G. gigantea'' could grow to the size of the largest moa

Moa are extinct giant flightless birds native to New Zealand.

The term has also come to be used for chicken in many Polynesian cultures and is found in the names of many chicken recipes, such as

Kale moa and Moa Samoa.

Moa or MOA may also refe ...

s, and reached about in maximum height.

The skull of ''G. gigantea'' was huge compared to the body and powerfully built. The beak was extremely tall and compressed (flattened from side to side). Unlike other species of ''Gastornis'', ''G. gigantea'' lacked characteristic grooves and pits on the underlying bone. The 'lip' of the beak was straight, without a raptorial hook as found in the predatory phorusrhacids. The nostrils were small and positioned close to the front of the eyes about midway up the skull. The vertebrae were short and massive, even in the neck. The neck was relatively short, consisting of at least 13 massive vertebrae. The torso was relatively short. The wings were vestigial, with the upper wing-bones small and highly reduced, similar in proportion to the wings of the cassowary

Cassowaries ( tpi, muruk, id, kasuari) are flightless birds of the genus ''Casuarius'' in the order Casuariiformes. They are classified as ratites (flightless birds without a keel on their sternum bones) and are native to the tropical forest ...

.

Classification

''Gastornis'' and its close relatives are classified together in thefamily

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Gastornithidae

''Gastornis'' is an extinct genus of large flightless birds that lived during the mid Paleocene to mid Eocene epochs of the Paleogene period. Fossils have been found in Europe, Asia and North America, with the remains from North America origina ...

, and were long considered to be members of the order Gruiformes

The Gruiformes are an order (biology), order containing a considerable number of living and extinct bird family (biology), families, with a widespread geographical diversity. Gruiform means "crane-like".

Traditionally, a number of wading and t ...

. However, the traditional concept of Gruiformes has since been shown to be an unnatural grouping. Beginning in the late 1980s with the first phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

analysis of gastornithid relationships, consensus began to grow that they were close relatives of the lineage that includes waterfowl

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which in ...

and screamers, the Anseriformes

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which in ...

. A 2007 study showed that gastornithids were a very early-branching group of anseriformes, and formed the sister group to all other members of that lineage.Agnolin, F. (2007). "''Brontornis burmeisteri'' Moreno & Mercerat, un Anseriformes (Aves) gigante del Mioceno Medio de Patagonia, Argentina." ''Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales'', n.s. 9, 15-25

Recognizing the apparent close relationship between gastornithids and waterfowl, some researchers classify gastornithids within the anseriform group itself. Others restrict the name Anseriformes only to the crown group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

formed by all modern species, and label the larger group including extinct relatives of anseriformes, like the gastornithids, with the name Anserimorphae

The Odontoanserae is a proposed clade that includes the family Pelagornithidae (pseudo-toothed birds) and the clade Anserimorphae (the order Anseriformes and their stem-relatives). The placement of the pseudo-toothed birds in the evolutionary tre ...

. Gastornithids are therefore sometimes placed in their own order, Gastornithiformes

Gastornithiformes were an extinct order of giant flightless fowl with fossils found in North America, Eurasia, and possibly Australia. Members of Gastornithidae were long considered to be a part of the order Gruiformes. However, the traditiona ...

.Buffetaut, E. (2002). "Giant ground birds at the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary: Extinction or survival?" ''Special papers - Geological Society of America'', 303-306.

A simplified version of the family tree found by Agnolin ''et al.'' in 2007 is reproduced below.

Today, at least five species of ''Gastornis'' are generally accepted as valid. The type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

, ''Gastornis parisiensis'', was named and described by Hébert in two 1855 papers. It is known from fossils found in western and central Europe, dating from the late Paleocene to the early Eocene. Other species previously considered distinct, but which are now considered synonymous with ''G. parisiensis'', include ''G. edwardsii'' (Lemoine, 1878) and ''G. klaasseni'' (Newton, 1885). Additional European species of ''Gastornis'' are ''G. russeli'' (Martin Martin may refer to:

Places

* Martin City (disambiguation)

* Martin County (disambiguation)

* Martin Township (disambiguation)

Antarctica

* Martin Peninsula, Marie Byrd Land

* Port Martin, Adelie Land

* Point Martin, South Orkney Islands

Austral ...

, 1992) from the late Paleocene of Berru, France, and ''G. sarasini'' (Schaub, 1929) from the early-middle Eocene. ''G. geiselensis'', from the middle Eocene of Messel, Germany, has been considered a synonym of ''G. sarasini'', however, other researchers have stated that there is currently insufficient evidence to synonymize the two, and that they should be kept separate at least pending a more detailed comparison of all gastornithids. The supposed small species ''G. minor'' is considered to be a ''nomen dubium

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium'' it may be impossible to determine whether a s ...

''.

''Gastornis gigantea'' (Cope

The cope (known in Latin as ''pluviale'' 'rain coat' or ''cappa'' 'cape') is a liturgical vestment, more precisely a long mantle or cloak, open in front and fastened at the breast with a band or clasp. It may be of any liturgical colours, litu ...

, 1876), formerly ''Diatryma'', dates from the middle Eocene of western North America. Its junior synonyms include ''Barornis regens'' (Marsh

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found at ...

, 1894) and ''Omorhamphus storchii'' (Sinclair, 1928). ''O. storchii'' was described based on fossils from lower Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

rocks of Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

. The species was named in honor of T. C. von Storch, who found the fossils remains in Princeton 1927 Expedition. The fossil bones originally described as ''Omorhamphus storchii'' are now considered to be the remains of a juvenile ''Gastornis gigantea''. Specimen YPM PU 13258 from lower Eocene Willwood Formation

The Willwood Formation is a sedimentary sequence deposited during the late Paleocene to early Eocene, or Clarkforkian, Wasatchian and Bridgerian in the NALMA classification.Park County, Wyoming

Park County is a county in the U.S. state of Wyoming. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 29,624. The county seat is Cody.

Park County is a major tourism destination. The county has over 53 percent of Yellowstone National Pa ...

also seems to be a juvenile – perhaps also of ''G. gigantea'', in which case it would be an even younger individual.

''Gastornis xichuanensis'', from the early Eocene of Henan

Henan (; or ; ; alternatively Honan) is a landlocked province of China, in the central part of the country. Henan is often referred to as Zhongyuan or Zhongzhou (), which literally means "central plain" or "midland", although the name is al ...

, China, is known only from a tibiotarsus (upper foot bone). It was originally described in 1980 as the only species in the distinct genus ''Zhongyuanus''. However, a re-evaluation of the fossil published in 2013 concluded that the differences between this specimen and the same bone in ''Gastornis'' species were minor, and that it should be considered an asian species of ''Gastornis''.

Paleobiology

Diet

A long-standing debate surrounding ''Gastornis'' is the interpretation of its diet. It has often been depicted as a predator of contemporary small mammals, which famously included the early horse ''

A long-standing debate surrounding ''Gastornis'' is the interpretation of its diet. It has often been depicted as a predator of contemporary small mammals, which famously included the early horse ''Eohippus

''Eohippus'' is an extinct genus of small equid ungulates. The only species is ''E. angustidens'', which was long considered a species of ''Hyracotherium''. Its remains have been identified in North America and date to the Early Eocene (Ypresian ...

''. However, with the size of ''Gastornis'' legs, the bird would have had to have been more agile to catch fast-moving prey than the fossils suggest it to have been. Consequently, ''Gastornis'' has been suspected to have been an ambush hunter and/or used pack hunting techniques to pursue or ambush prey; if ''Gastornis'' was a predator, it would have certainly needed some other means of hunting prey through the dense forest. Alternatively, it could have used its strong beak for eating large or strong vegetation.

The skull of ''Gastornis'' is massive in comparison to those of living ratite

A ratite () is any of a diverse group of flightless, large, long-necked, and long-legged birds of the infraclass Palaeognathae. Kiwi, the exception, are much smaller and shorter-legged and are the only nocturnal extant ratites.

The systematics ...

s of similar body size. Biomechanical analysis of the skull suggests that the jaw-closing musculature was enormous. The lower jaw is very deep, resulting in a lengthened moment arm of the jaw muscles. Both features strongly suggest that ''Gastornis'' could generate a powerful bite. Some scientists have proposed that the skull of ''Gastornis'' was ‘overbuilt’ for a herbivorous diet and support the traditional interpretation of ''Gastornis'' as a carnivore that used its powerfully constructed beak to subdue struggling prey and crack open bones to extract marrow. Others have noted the apparent lack of predatory features in the skull, such as a prominently hooked beak, as evidence that ''Gastornis'' was a specialized herbivore (or even an omnivore

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nutr ...

) of some sort, perhaps having used its large beak to crack hard foods like nuts and seeds. Footprints attributed to gastornithids (possibly a species of ''Gastornis'' itself), described in 2012, showed that these birds lacked strongly hooked talons on the hind legs, another line of evidence suggesting that they did not have a predatory lifestyle.

Recent evidence suggests that ''Gastornis'' was likely a true herbivore. Studies of the calcium isotopes in the bones of specimens of ''Gastornis'' by Thomas Tutken and colleagues showed no evidence that it had meat in its diet. The geochemical analysis further revealed that its dietary habits were similar to those of both herbivorous dinosaurs and mammals when it was compared to known fossil carnivores, such as ''Tyrannosaurus rex

''Tyrannosaurus'' is a genus of large theropod dinosaur. The species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' (''rex'' meaning "king" in Latin), often called ''T. rex'' or colloquially ''T-Rex'', is one of the best represented theropods. ''Tyrannosaurus'' live ...

'', leaving phorusrhacid

Phorusrhacids, colloquially known as terror birds, are an extinct clade of large carnivorous flightless birds that were one of the largest species of apex predators in South America during the Cenozoic era; their conventionally accepted temporal ...

s as the only major carnivorous flightless birds.

Eggs

InLate Paleocene

The Thanetian is, in the International Commission on Stratigraphy, ICS Geologic timescale, the latest age (geology), age or uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stratigraphic stage of the Paleocene epoch (geology), Epoch or series (stratigraphy), Serie ...

deposits of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and early Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

deposits of France, shell fragments of huge eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

have turned up, namely in Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bor ...

. These were described as the ootaxon

Egg fossils are the fossilized remains of eggs laid by ancient animals. As evidence of the physiological processes of an animal, egg fossils are considered a type of trace fossil. Under rare circumstances a fossil egg may preserve the remains of ...

''Ornitholithus'' and are presumably from ''Gastornis''. While no direct association exists between ''Ornitholithus'' and ''Gastornis'' fossils, no other birds of sufficient size are known from that time and place; while the large ''Diogenornis

''Diogenornis'' is an extinct genus of ratites, that lived during the Early Eocene (Itaboraian to Casamayoran in the SALMA classification).Eremopezus

''Eremopezus'' is a prehistoric bird genus, possibly a palaeognath. It is known only from the fossil remains of a single species, the huge and presumably flightless ''Eremopezus eocaenus''. This was found in Upper Eocene Jebel Qatrani Formatio ...

'' are known from the Eocene, the former lived in South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

(still separated from North America by the Tethys Ocean

The Tethys Ocean ( el, Τηθύς ''Tēthús''), also called the Tethys Sea or the Neo-Tethys, was a prehistoric ocean that covered most of the Earth during much of the Mesozoic Era and early Cenozoic Era, located between the ancient continents ...

then) and the latter is only known from the Late Eocene of North Africa, which also was separated by an (albeit less wide) stretch of the Tethys Ocean from Europe.

Some of these fragments were complete enough to reconstruct a size of 24 by 10 cm (about 9.5 by 4 inches) with shells 2.3–2.5 mm (0.09–0.1 in) thick, roughly half again as large as an ostrich egg and very different in shape from the more rounded ratite eggs. If ''Remiornis'' is indeed correctly identified as a ratite (which is quite doubtful, however), ''Gastornis'' remains as the only known animal that could have laid these eggs. At least one species of ''Remiornis'' is known to have been smaller than ''Gastornis'', and was initially described as ''Gastornis minor'' by Mlíkovský in 2002. This would nicely match the remains of eggs a bit smaller than those of the living ostrich, which have also been found in Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; British English, also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period, geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million yea ...

deposits of Provence, were it not for the fact that these eggshell fossils also date from the Eocene, but no ''Remiornis'' bones are yet known from that time.

Footprints

Several sets of fossil footprints are suspected to belong to ''Gastornis''. One set of footprints was reported from late

Several sets of fossil footprints are suspected to belong to ''Gastornis''. One set of footprints was reported from late Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

gypsum

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula . It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, blackboard or sidewalk chalk, and drywall. ...

at Montmorency and other locations of the Paris Basin

The Paris Basin is one of the major geological regions of France. It developed since the Triassic over remnant uplands of the Variscan orogeny (Hercynian orogeny). The sedimentary basin, no longer a single drainage basin, is a large sag in th ...

in the 19th century, from 1859 onwards. Described initially by Jules Desnoyers, and later on by Alphonse Milne-Edwards

Alphonse Milne-Edwards (Paris, 13 October 1835 – Paris, 21 April 1900) was a French mammalogist, ornithologist, and carcinologist. He was English in origin, the son of Henri Milne-Edwards and grandson of Bryan Edwards, a Jamaican planter who se ...

, these trace fossils were celebrated among French geologists of the late 19th century. They were discussed by Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

in his '' Elements of Geology'' as an example of the incompleteness of the fossil record – no bones had been found associated with the footprints. Unfortunately, these fine specimens, which sometimes even preserved details of the skin structure, are now lost. They were brought to the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle

The French National Museum of Natural History, known in French as the ' (abbreviation MNHN), is the national natural history museum of France and a ' of higher education part of Sorbonne Universities. The main museum, with four galleries, is loc ...

when Desnoyers started to work there, and the last documented record of them deals with their presence in the geology exhibition of the MNHN in 1912. The largest of these footprints, although only consisting of a single toe's impression, was 40 cm (16 in) long. The large footprints from the Paris Basin

The Paris Basin is one of the major geological regions of France. It developed since the Triassic over remnant uplands of the Variscan orogeny (Hercynian orogeny). The sedimentary basin, no longer a single drainage basin, is a large sag in th ...

could also be divided into huge and merely large examples, much like the eggshells from southern France, which are 20 million years older.

Another footprint record consists of a single imprint that still exists, though it has proven to be even more controversial. It was found in late Eocene Puget Group rocks in the Green River Green River may refer to:

Rivers

Canada

* Green River (British Columbia), a tributary of the Lillooet River

*Green River, a tributary of the Saint John River, also known by its French name of Rivière Verte

*Green River (Ontario), a tributary of ...

valley near Black Diamond, Washington

Black Diamond is a city in King County, Washington, United States. The population was 4,697 at the 2020 census. In 2021, with a 21% growth rate, Black Diamond was the fastest growing small city in King County.

History

Founding

Black Diamond ...

. After its discovery, it raised considerable interest in the Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

area in May–July 1992, being subject of at least two longer articles in the ''Seattle Times

''The Seattle Times'' is a daily newspaper serving Seattle, Washington, United States. It was founded in 1891 and has been owned by the Blethen family since 1896. ''The Seattle Times'' has the largest circulation of any newspaper in Washington st ...

''. Variously declared a hoax

A hoax is a widely publicized falsehood so fashioned as to invite reflexive, unthinking acceptance by the greatest number of people of the most varied social identities and of the highest possible social pretensions to gull its victims into pu ...

or genuine, this apparent impression of a single bird foot measures about 27 cm wide by 32 cm long (11 by 13 in) and lacks a hallux

Toes are the digits (fingers) of the foot of a tetrapod. Animal species such as cats that walk on their toes are described as being '' digitigrade''. Humans, and other animals that walk on the soles of their feet, are described as being '' pl ...

(hind toe); it was described as the ichnotaxon

An ichnotaxon (plural ichnotaxa) is "a taxon based on the fossilized work of an organism", i.e. the non-human equivalent of an artifact. ''Ichnotaxa'' comes from the Greek ίχνος, ''ichnos'' meaning ''track'' and ταξις, ''taxis'' meaning ...

''Ornithoformipes controversus''. Fourteen years after the initial discovery, the debate about the find's authenticity was still unresolved. The specimen is now at Western Washington University

Western Washington University (WWU or Western) is a public university in Bellingham, Washington. The northernmost university in the contiguous United States, WWU was founded in 1893 as the state-funded New Whatcom Normal School, succeeding a pri ...

.The problem with these early trace fossils is that no fossil of ''Gastornis'' has been found to be younger than about 45 million years. The enigmatic ''"Diatryma" cotei'' is known from remains almost as old as the Paris basin footprints (whose date never could be accurately determined), but in North America the fossil record of unequivocal gastornithids seems to end even earlier than in Europe. However, in 2009, a landslide near Bellingham, Washington

Bellingham ( ) is the most populous city in, and county seat of Whatcom County in the U.S. state of Washington. It lies south of the U.S.–Canada border in between two major cities of the Pacific Northwest: Vancouver, British Columbia (locat ...

exposed at least 18 tracks on 15 blocks in the Eocene Chuckanut Formation

The Chuckanut Formation in northwestern Washington (named after the Chuckanut Mountains, near Bellingham, Washington, Bellingham), its extension in southwestern British Columbia (the Huntingdon Formation), and various related Geological formati ...

. The anatomy and age (about 53.7 Ma old) of the tracks suggest that the track maker was ''Gastornis''. Although these birds have long been considered to be predators or scavengers, the absence of raptor-like claws supports earlier suggestions that they were herbivores. The Chuckanut tracks are named as the ichnotaxon ''Rivavipes giantess'', inferred to belong to the extinct family Gastornithidae. At least 10 of the tracks are on display at Western Washington University.

Feathers

The

The plumage

Plumage ( "feather") is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, ...

of ''Gastornis'' has generally been depicted in art as a hair-like covering similar to some ratite

A ratite () is any of a diverse group of flightless, large, long-necked, and long-legged birds of the infraclass Palaeognathae. Kiwi, the exception, are much smaller and shorter-legged and are the only nocturnal extant ratites.

The systematics ...

s. This has been based in part on some fibrous strands recovered from a Green River Formation

The Green River Formation is an Eocene geologic formation that records the sedimentation in a group of intermountain lakes in three basins along the present-day Green River in Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah. The sediments are deposited in very fine ...

deposit at Roan Creek, Colorado, which were initially believed to represent ''Gastornis'' feathers and named ''Diatryma filifera''. Subsequent examination has shown the supposed feathers were actually not feathers at all, but plant fiber

Fiber crops are field crops grown for their fibers, which are traditionally used to make paper, cloth, or rope.

Fiber crops are characterized by having a large concentration of cellulose, which is what gives them their strength. The fibers may b ...

s.

However, a second possible ''Gastornis'' feather has since been identified, also from the Green River Formation. Unlike the filamentous plant material, this single isolated feather resembles the body feathers of flighted birds, being broad and vaned. It was tentatively identified as a possible ''Gastornis'' feather based on its size; the feather measured long and must have belonged to a gigantic bird.Grande, L. (2013). ''The Lost World of Fossil Lake: Snapshots from Deep Time''. University of Chicago Press.

Distribution

''Gastornis'' fossils are known from across western Europe, the western United States, and central China. The earliest (Paleocene) fossils all come from Europe, and it is likely that the genus originated there. Europe in this epoch was an island continent, and ''Gastornis'' was the largest terrestrial tetrapod of the landmass. This offers parallels with the malagasy

''Gastornis'' fossils are known from across western Europe, the western United States, and central China. The earliest (Paleocene) fossils all come from Europe, and it is likely that the genus originated there. Europe in this epoch was an island continent, and ''Gastornis'' was the largest terrestrial tetrapod of the landmass. This offers parallels with the malagasy elephant birds

Elephant birds are members of the Extinction, extinct ratite family (biology), family Aepyornithidae, made up of flightless birds that once lived on the island of Madagascar. They are thought to have become extinct around 1000-1200 CE, probably ...

, herbivorous birds that were similarly the largest land animals in the isolated landmass of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

, in spite of otherwise mammalian megafauna.

All other fossil remains are from the Eocene; however, it is not currently known how ''Gastornis'' dispersed out of Europe and into North America and Asia. Given the presence of ''Gastornis'' fossils in the early Eocene of western China, these birds may have spread east from Europe and crossed into North America via the Bering land bridge

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip of ...

. ''Gastornis'' also may have spread both east and west, arriving separately in eastern Asia and in North America across the Turgai Strait. Direct landbridges with North America are also known.

European ''Gastornis'' survived somewhat longer than their North American and Asian counterparts. This seems to coincide with a period of increased isolation of the continent.

Extinction

The reason for the extinction of ''Gastornis'' is currently unclear. Competition with mammals has often been cited as a possible factor, but ''Gastornis'' did occur in faunas dominated by mammals, and did co-exist with several megafaunal forms likepantodonts

Pantodonta is an extinct suborder (or, according to some, an order) of eutherian mammals. These herbivorous mammals were one of the first groups of large mammals to evolve (around 66 million years ago) after the end of the Cretaceous. The l ...

. Likewise, extreme climatic events like the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) appear to have had little impact.

Nonetheless, the extended survival in Europe is thought to coincide with increased isolation of the landmass.

References

External links

* {{Taxonbar, from=Q131477 Gastornithiformes Paleogene birds of Europe Paleogene birds of North America Fossil taxa described in 1855 Paleocene birds Eocene birds Paleocene first appearances Eocene genus extinctions