Gael Givet on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

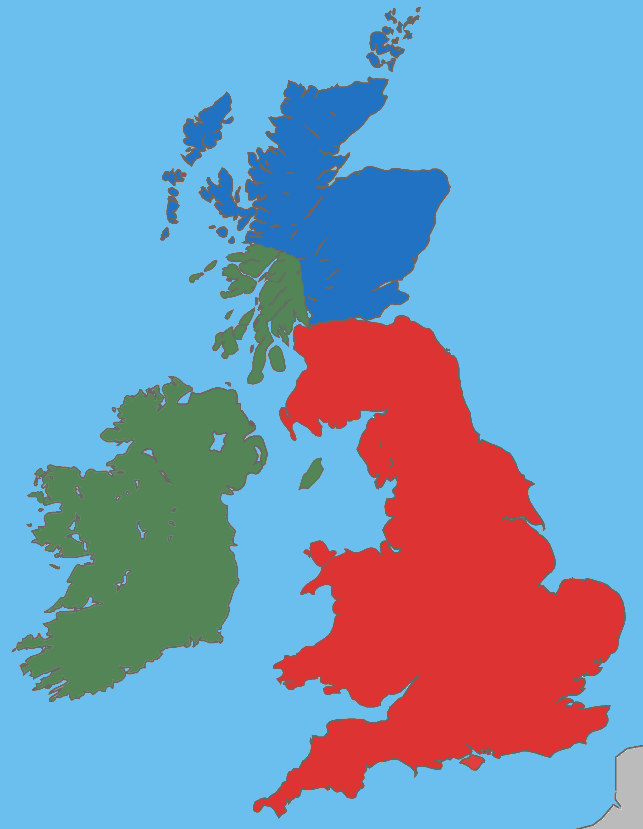

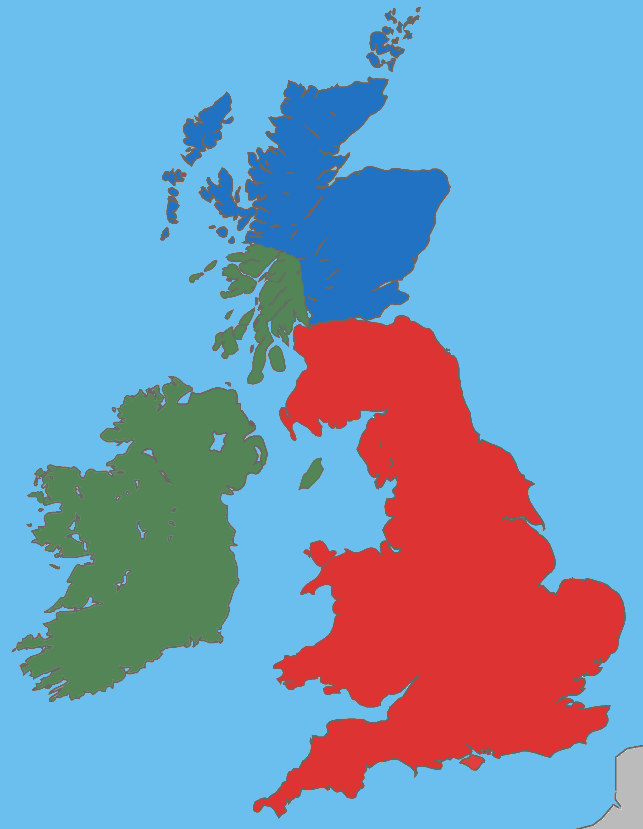

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languages comprising Irish,

A common name, passed down to the modern day, is " Irish"; this existed in the English language during the 11th century in the form of ''Irisce'', which derived from the stem of

A common name, passed down to the modern day, is " Irish"; this existed in the English language during the 11th century in the form of ''Irisce'', which derived from the stem of

The

The

In traditional Gaelic society, a patrilineal kinship group is referred to as a ''

In traditional Gaelic society, a patrilineal kinship group is referred to as a ''

At the turn of the 21st century, the principles of human genetics and

At the turn of the 21st century, the principles of human genetics and

"Three Bronze Age individuals from Rathlin Island (2026–1534 cal BC), including one high coverage (10.5×) genome, showed substantial Steppe genetic heritage indicating that the European population upheavals of the third millennium manifested all of the way from southern Siberia to the western ocean. This turnover invites the possibility of accompanying introduction of Indo-European, perhaps early Celtic, language. Irish Bronze Age haplotypic similarity is strongest within modern Irish, Scottish, and Welsh populations, and several important genetic variants that today show maximal or very high frequencies in Ireland appear at this horizon. These include those coding for lactase persistence, blue eye color, Y chromosome R1b haplotypes, and the hemochromatosis C282Y allele; to our knowledge, the first detection of a known Mendelian disease variant in prehistory. These findings together suggest the establishment of central attributes of the Irish genome 4,000 y ago." Several genetic traits found at maximum or very high frequencies in the modern populations of Gaelic ancestry were also observed in the Bronze Age period. These traits include a hereditary disease known as HFE hereditary haemochromatosis, Y-DNA Haplogroup R-M269, lactase persistence and blue eyes. Another trait very common in Gaelic populations is

In their own

In their own

According to the '' Annals of the Four Masters'', the early branches of the Milesian Gaels were the Heremonians, the

According to the '' Annals of the Four Masters'', the early branches of the Milesian Gaels were the Heremonians, the

Christianity reached Ireland during the 5th century, most famously through a Romano-British slave

Christianity reached Ireland during the 5th century, most famously through a Romano-British slave  Some, particularly champions of Christianity, hold the 6th to 9th centuries to be a Golden Age for the Gaels. This is due to the influence which the Gaels had across Western Europe as part of their Christian missionary activities. Similar to the Desert Fathers, Gaelic monastics were known for their

Some, particularly champions of Christianity, hold the 6th to 9th centuries to be a Golden Age for the Gaels. This is due to the influence which the Gaels had across Western Europe as part of their Christian missionary activities. Similar to the Desert Fathers, Gaelic monastics were known for their  The remainder of the Middle Ages was marked by conflict between Gaels and Anglo-Normans. The Norman invasion of Ireland took place in stages during the late 12th century. Norman mercenaries landed in Leinster in 1169 at the request of Diarmait Mac Murchada, who sought their help in regaining his throne. By 1171 the Normans had gained control of Leinster, and King Henry II of England, with the backing of the Papacy, established the Lordship of Ireland. The Norman kings of England claimed sovereignty over this territory, leading to centuries of conflict between the Normans and the native Irish. At this time, a literary anti-Gaelic sentiment was born and developed by the likes of Gerald of Wales as part of a propaganda campaign (with a Gregorian "reform" gloss) to justify taking Gaelic lands. Scotland also came under Anglo-Norman influence in the 12th century. The Davidian Revolution saw the Normanisation of Scotland's monarchy, government and church; the founding of

The remainder of the Middle Ages was marked by conflict between Gaels and Anglo-Normans. The Norman invasion of Ireland took place in stages during the late 12th century. Norman mercenaries landed in Leinster in 1169 at the request of Diarmait Mac Murchada, who sought their help in regaining his throne. By 1171 the Normans had gained control of Leinster, and King Henry II of England, with the backing of the Papacy, established the Lordship of Ireland. The Norman kings of England claimed sovereignty over this territory, leading to centuries of conflict between the Normans and the native Irish. At this time, a literary anti-Gaelic sentiment was born and developed by the likes of Gerald of Wales as part of a propaganda campaign (with a Gregorian "reform" gloss) to justify taking Gaelic lands. Scotland also came under Anglo-Norman influence in the 12th century. The Davidian Revolution saw the Normanisation of Scotland's monarchy, government and church; the founding of

The Gaelic languages are part of the Celtic languages and fall under the wider

The Gaelic languages are part of the Celtic languages and fall under the wider

The traditional, or "

The traditional, or "

The Gaels underwent Christianisation during the 5th century and that religion, ''de facto'', remains the predominant one to this day, although irreligion is fast rising. At first the

The Gaels underwent Christianisation during the 5th century and that religion, ''de facto'', remains the predominant one to this day, although irreligion is fast rising. At first the

Foras na Gaeilge

nbsp;– Irish agency promoting the language

nbsp;– Scottish agency promoting the language

Culture Vannin

nbsp;– Manx agency promoting the language

The Columba Project

nbsp;– Pan-Gaelic cultural initiative

Gaelic Society Collection

at University College London (c. 700 items collected by the Gaelic Society of London) {{authority control Celtic ethnolinguistic groups Ethnic groups in Argentina Ethnic groups in Australia Ethnic groups in Canada Ethnic groups in Iceland Ethnic groups in Ireland Ethnic groups in Mexico Ethnic groups in New Zealand Ethnic groups in Scotland Ethnic groups in the United States Ethnic groups in Uruguay Highlands and Islands of Scotland Manx language Ethnic groups in Northern Ireland

Manx

Manx (; formerly sometimes spelled Manks) is an adjective (and derived noun) describing things or people related to the Isle of Man:

* Manx people

**Manx surnames

* Isle of Man

It may also refer to:

Languages

* Manx language, also known as Manx ...

and Scottish Gaelic.

Gaelic language and culture originated in Ireland, extending to Dál Riata in western Scotland. In antiquity, the Gaels traded with the Roman Empire and also raided Roman Britain. In the Middle Ages, Gaelic culture became dominant throughout the rest of Scotland and the Isle of Man. There was also some Gaelic settlement in Wales, as well as cultural influence through Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Crìosdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Críostaíocht/Críostúlacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held ...

. In the Viking Age, small numbers of Vikings raided and settled in Gaelic lands, becoming the Norse-Gaels. In the 9th century, Dál Riata and Pictland merged to form the Gaelic Kingdom of Alba. Meanwhile, Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, Éire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans co ...

was made up of several kingdoms, with a High King often claiming lordship over them.

In the 12th century, Anglo-Normans conquered

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent, t ...

parts of Ireland, while parts of Scotland became Normanized. However, Gaelic culture remained strong throughout Ireland, the Scottish Highlands and Galloway. In the early 17th century, the last Gaelic kingdoms in Ireland fell under English control. James VI and I sought to subdue the Gaels and wipe out their culture; first in the Scottish Highlands via repressive laws such as the Statutes of Iona

The Statutes of Iona, passed in Scotland in 1609, required that Highland Scottish clan chiefs send their heirs to Lowland Scotland to be educated in English-speaking Protestant schools. As a result, some clans, such as the MacDonalds of Sleat and ...

, and then in Ireland by colonizing Gaelic land with English-speaking Protestant settlers. In the following centuries Gaelic language was suppressed and mostly supplanted by English. However, it continues to be the main language in Ireland's '' Gaeltacht'' and Scotland's Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides () or Western Isles ( gd, Na h-Eileanan Siar or or ("islands of the strangers"); sco, Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle/Long Island ( gd, An t-Eilean Fada, links=no), is an island chain off the west coast ...

. The modern descendants of the Gaels have spread throughout the rest of the British Isles, the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

and Australasia.

Traditional Gaelic society is organised into clans

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

, each with its own territory and king (or chief), elected through tanistry. The Irish were previously pagans Pagans may refer to:

* Paganism, a group of pre-Christian religions practiced in the Roman Empire

* Modern Paganism, a group of contemporary religious practices

* Order of the Vine, a druidic faction in the ''Thief'' video game series

* Pagan's ...

who had many gods, venerated the ancestors and believed in an Otherworld. Their four yearly festivals – Samhain, Imbolc, Beltane and Lughnasa

Lughnasadh or Lughnasa ( , ) is a Gaels, Gaelic festival marking the beginning of the harvest season. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. In Modern Irish it is called , in gd, Lùnastal, and i ...

– continued to be celebrated into modern times. The Gaels have a strong oral tradition, traditionally maintained by shanachies. Inscription in the ogham alphabet began in the 4th century. The Gaels' conversion to Christianity accompanied the introduction of writing in the Roman alphabet. Irish mythology and Brehon law were preserved and recorded by medieval Irish monasteries. Gaelic monasteries were renowned centres of learning and played a key role in developing Insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style dif ...

; Gaelic missionaries and scholars were highly influential in western Europe. In the Middle Ages, most Gaels lived in roundhouses and ringfort

Ringforts, ring forts or ring fortresses are circular fortified settlements that were mostly built during the Bronze Age up to about the year 1000. They are found in Northern Europe, especially in Ireland. There are also many in South Wales ...

s. The Gaels had their own style of dress, which became the belted plaid and kilt. They also have distinctive music, dance, festivals, and sports. Gaelic culture continues to be a major component of Irish, Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

and Manx culture.

Ethnonyms

Throughout the centuries, Gaels and Gaelic-speakers have been known by a number of names. The most consistent of these have been ''Gael'', '' Irish'' and '' Scots''. In Latin, the Gaels were called ''Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but l ...

'', but this later came to mean only the Gaels of Scotland. Other terms, such as '' Milesian'', are not as often used. An Old Norse name for the Gaels was ''Vestmenn {{unreferenced, date=August 2016

Vestmenn (''Westmen'' in English) was the Old Norse word for the Gaels of Ireland and Britain, especially Ireland and Scotland. Vestmannaeyjar in Iceland and Vestmanna in the Faroe Islands take their names from it. T ...

'' (meaning "Westmen", due to inhabiting the Western fringes of Europe). Informally, archetypal forenames such as '' Tadhg'' or ''Dòmhnall

Donald is a masculine given name derived from the Gaelic name ''Dòmhnall''.. This comes from the Proto-Celtic *''Dumno-ualos'' ("world-ruler" or "world-wielder"). The final -''d'' in ''Donald'' is partly derived from a misinterpretation of the ...

'' are sometimes used for Gaels.

''Gael''

The word "Gaelic" is first recorded in print in the English language in the 1770s, replacing the earlier word ''Gathelik'' which is attested as far back as 1596. ''Gael'', defined as a "member of the Gaelic race", is first attested in print in 1810. In English, the more antiquarian term ''Goidels'' came to be used by some due to Edward Lhuyd's work on the relationship between Celtic languages. This term was further popularised in academia by John Rhys; the first Professor of Celtic at Oxford University; due to his work ''Celtic Britain'' (1882). These names all come from the Old Irish word ''Goídel/Gaídel''. In early modern Irish, it was spelled ''Gaoidheal'' (singular) and ''Gaoidheil/Gaoidhil'' (plural). In modern Irish, it is spelled ''Gael'' (singular) and ''Gaeil'' (plural). According to scholarJohn T. Koch

John T. Koch is an American academic, historian and linguist who specializes in Celtic studies, especially prehistory and the early Middle Ages. He is the editor of the five-volume ''Celtic Culture. A Historical Encyclopedia'' (2006, ABC Clio). He ...

, the Old Irish form of the name was borrowed from an Archaic Welsh form ''Guoidel'', meaning "forest people", "wild men" or, later, "warriors". ''Guoidel'' is recorded as a personal name in the '' Book of Llandaff''. The root of the name is cognate at the Proto-Celtic level with Old Irish ''fíad'' 'wild', and ''Féni'', derived ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *''weidh-n-jo-''. This latter word is the origin of '' Fianna'' and '' Fenian''.

In medieval Ireland, the bardic poets who were the cultural intelligentsia of the nation, limited the use of ''Gaoidheal'' specifically to those who claimed genealogical descent from the mythical Goídel Glas

In medieval Irish and Scottish legend, Goídel Glas (Latinised as Gaithelus) is the creator of the Goidelic languages and eponymous ancestor of the Gaels. The tradition can be traced to the 11th-century ''Lebor Gabála Érenn''. A Scottish varia ...

. Even the Gaelicised Normans who were born in Ireland, spoke Irish and sponsored Gaelic bardic poetry, such as Gearóid Iarla, were referred to as ''Gall'' ("foreigner") by Gofraidh Fionn Ó Dálaigh, then Chief Ollam of Ireland.

''Irish''

A common name, passed down to the modern day, is " Irish"; this existed in the English language during the 11th century in the form of ''Irisce'', which derived from the stem of

A common name, passed down to the modern day, is " Irish"; this existed in the English language during the 11th century in the form of ''Irisce'', which derived from the stem of Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

''Iras'', "inhabitant of Ireland", from Old Norse ''irar''. The ultimate origin of this word is thought to be the Old Irish '' Ériu'', which is from Old Celtic

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly reconstructed through the comparative method. Proto-Celtic ...

''*Iveriu'', likely associated with the Proto-Indo-European term ''*pi-wer-'' meaning "fertile". Ériu is mentioned as a goddess in the '' Lebor Gabála Érenn'' as a daughter of Ernmas

Ernmas is an Irish mother goddess, mentioned in ''Lebor Gabála Érenn'' and "Cath Maige Tuired" as one of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Her daughters include the trinity of eponymous Irish goddesses Ériu, Banba and Fódla, the trinity of war goddesses t ...

of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Along with her sisters Banba and Fódla

In Irish mythology, Fódla or Fótla (modern spelling: Fódhla, Fodhla or Fóla), daughter of Delbáeth and Ernmas of the Tuatha Dé Danann, was one of the tutelary giantesses of Ireland. Her husband was Mac Cecht.

With her sisters, Banba and � ...

, she is said to have made a deal with the Milesians to name the island after her.

The ancient Greeks, in particular Ptolemy in his second century '' Geographia'', possibly based on earlier sources, located a group known as the Iverni ( el, Ιουερνοι) in the south-west of Ireland. This group has been associated with the Érainn of Irish tradition by T. F. O'Rahilly

Thomas Francis O'Rahilly ( ga, Tomás Ó Rathile; 11 November 1882 – 16 November 1953)Ó Sé, Diarmuid.O'Rahilly, Thomas Francis (‘T. F.’). ''Dictionary of Irish Biography''. (ed.) James McGuire, James Quinn. Cambridge, United Kingdom: C ...

and others. The Érainn, claiming descent from a Milesian eponymous ancestor named Ailill Érann

The Iverni (, ') were a people of early Ireland first mentioned in Ptolemy's 2nd century ''Geography (Ptolemy), Geography'' as living in the extreme south-west of the island. He also locates a "city" called Ivernis (, ') in their territory, and ...

, were the hegemonic power in Ireland before the rise of the descendants of Conn of the Hundred Battles

Conn Cétchathach (; "of the Hundred Battles"), son of Fedlimid Rechtmar, was a semi-legendary High King of Ireland and the ancestor of the Connachta, and, through his descendant Niall Noígiallach, the Uí Néill dynasties, which dominated Irela ...

and Mug Nuadat. The Érainn included peoples such as the Corcu Loígde

The Corcu Loígde (Corcu Lóegde, Corco Luigde, Corca Laoighdhe, Laidhe), meaning Gens of the Calf Goddess, also called the Síl Lugdach meic Itha, were a kingdom centred in West County Cork who descended from the proto-historical rulers of Mun ...

and Dál Riata. Ancient Roman

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

writers, such as Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...

, Pliny and Tacitus, derived from ''Ivernia'' the name '' Hibernia''. Thus the name "Hibernian" also comes from this root, although the Romans tended to call the isle '' Scotia'', and the Gaels ''Scoti''. Within Ireland itself, the term ''Éireannach'' (Irish), only gained its modern political significance as a primary denominator from the 17th century onwards, as in the works of Geoffrey Keating, where a Catholic alliance between the native ''Gaoidheal'' and '' Seanghaill'' ("old foreigners", of Norman descent) was proposed against the ''Nuaghail'' or ''Sacsanach'' (the ascendant Protestant New English settlers).

''Scots''

The

The Scots Gaels

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languag ...

derive from the kingdom of Dál Riata, which included parts of western Scotland and northern Ireland. It has various explanations of its origins, including a foundation myth of an invasion from Ireland and a more recent archaeological and linguistic analysis that points to a pre-existing maritime province united by the sea and isolated from the rest of Scotland by the Scottish Highlands or ''Druim Alban''. The genetical exchange includes passage of the M222 genotype within Scotland.

From the 5th to 10th centuries, early Scotland was home not only to the Gaels of Dál Riata but also the Picts, the Britons, Angles and lastly the Vikings. The Romans began to use the term ''Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but l ...

'' to describe the Gaels in Latin from the 4th century onward. At the time, the Gaels were raiding the west coast of Britain, and they took part in the Great Conspiracy; it is thus conjectured that the term means "raider, pirate". Although the Dál Riata settled in Argyll in the 6th century, the term "Scots" did not just apply to them, but to Gaels in general. Examples can be taken from Johannes Scotus Eriugena

John Scotus Eriugena, also known as Johannes Scotus Erigena, John the Scot, or John the Irish-born ( – c. 877) was an Irish people, Irish Neoplatonism, Neoplatonist Philosophy, philosopher, Theology, theologian and poet of the Early M ...

and other figures from Hiberno-Latin

Hiberno-Latin, also called Hisperic Latin, was a learned style of literary Latin first used and subsequently spread by Irish monks during the period from the sixth century to the tenth century.

Vocabulary and influence

Hiberno-Latin was notab ...

culture and the ''Schottenkloster

The Hiberno-Scottish mission was a series of expeditions in the 6th and 7th centuries by Gaelic missionaries originating from Ireland that spread Celtic Christianity in Scotland, Wales, England and Merovingian France. Celtic Christianity sp ...

'' founded by Irish Gaels in Germanic lands.

The Gaels of northern Britain referred to themselves as ''Albannaich

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languag ...

'' in their own tongue and their realm as the Kingdom of Alba (founded as a successor kingdom to Dál Riata and Pictland). Germanic groups tended to refer to the Gaels as ''Scottas'' and so when Anglo-Saxon influence grew at court with Duncan II, the Latin ''Rex Scottorum'' began to be used and the realm was known as Scotland; this process and cultural shift was put into full effect under David I, who let the Normans come to power and furthered the Lowland-Highland divide. Germanic-speakers in Scotland spoke a language called '' Inglis'', which they started to call ''Scottis'' ( Scots) in the 16th century, while they in turn began to refer to Scottish Gaelic as ''Erse'' (meaning "Irish").

Population

Kinship groups

In traditional Gaelic society, a patrilineal kinship group is referred to as a ''

In traditional Gaelic society, a patrilineal kinship group is referred to as a ''clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

n'' or, in Ireland, a ''fine.'' Both in technical use signify a dynastic grouping descended from a common ancestor, much larger than a personal family, which may also consist of various kindreds and septs

A sept is a division of a family, especially of a Scottish clan, Scottish or List of Irish clans, Irish family. The term is used in both Scotland and Ireland, where it may be translated as ''sliocht'', meaning "progeny" or "seed", which may ind ...

. (''Fine'' is not to be confused with the term ''fian

''Fianna'' ( , ; singular ''Fian''; gd, Fèinne ) were small warrior-hunter bands in Gaelic Ireland during the Prehistoric_Ireland#Iron_Age_(500_BC_–_AD_400), Iron Age and History of Ireland (400–800), early Middle Ages. A ''fian'' was mad ...

'', a 'band of roving men whose principal occupations were hunting and war, also a troop of professional fighting-men under a leader; in wider sense a company, number of persons; a warrior (late and rare)').

Using the Munster-based Eóganachta as an example, members of this ''clann'' claim patrilineal descent from Éogan Mór. It is further divided into major kindreds, such as the Eóganacht Chaisil, Glendamnach, Áine, Locha Léin and Raithlind. These kindreds themselves contain septs that have passed down as Irish Gaelic surnames, for example the Eóganacht Chaisil includes O'Callaghan, MacCarthy, O'Sullivan and others.

The Irish Gaels can be grouped into the following major historical groups; Connachta

The Connachta are a group of medieval Irish dynasties who claimed descent from the legendary High King Conn Cétchathach (Conn of the Hundred Battles). The modern western province of Connacht (Irish ''Cúige Chonnacht'', province, literally "f ...

(including Uí Néill, Clan Colla

The Three Collas (Modern Irish: Trí Cholla) were, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, the fourth-century sons of Eochaid Doimlén, son of Cairbre Lifechair. Their names were: Cairell Colla Uais; Muiredach Colla Fo Chrí (a ...

, Uí Maine

U or u, is the twenty-first and sixth-to-last letter and fifth vowel letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''u'' (pro ...

, etc.), Dál gCais

The Dalcassians ( ga, Dál gCais ) are a Gaelic Irish clan, generally accepted by contemporary scholarship as being a branch of the Déisi Muman, that became very powerful in Ireland during the 10th century. Their genealogies claimed descent fr ...

, Eóganachta, Érainn (including Dál Riata, Dál Fiatach, etc.), Laigin and Ulaid (including Dál nAraidi). In the Highlands, the various Gaelic-originated clans tended to claim descent from one of the Irish groups, particularly those from Ulster. The Dál Riata (i.e. – MacGregor, MacDuff, MacLaren, etc.) claimed descent from Síl Conairi, for instance. Some arrivals in the High Middle Ages (i.e. – MacNeill, Buchanan, Munro, etc.) claimed to be of the Uí Néill. As part of their self-justification; taking over power from the Norse-Gael MacLeod in the Hebrides; the MacDonalds claimed to be from Clan Colla.

For the Irish Gaels, their culture did not survive the conquests and colonisations by the English between 1534 and 1692 (see History of Ireland (1536–1691)

Ireland during the period of 1536–1691 saw the first full conquest of the island by England and its colonization with mostly Protestant settlers from Great Britain. This would eventually establish two central themes in future Irish history: ...

, Tudor conquest of Ireland, Plantations of Ireland

Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland involved the confiscation of Irish-owned land by the English Crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from Great Britain. The Crown saw the plantations as a means of controlling, angl ...

, Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland or Cromwellian war in Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell invaded Ireland wi ...

, Williamite War in Ireland. As a result of the Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

, there has been renewed interest in Irish genealogy; the Irish Government

The Government of Ireland ( ga, Rialtas na hÉireann) is the cabinet that exercises executive authority in Ireland.

The Constitution of Ireland vests executive authority in a government which is headed by the , the head of government. The governm ...

recognised Gaelic Chiefs of the Name since the 1940s. The ''Finte na hÉireann

Clans of Ireland (Irish: ''Finte na hÉireann'') is an independent organisation established in 1989 with the purpose of creating and maintaining a register of Irish clans. The patron of the organisation is Michael D. Higgins, President of Irela ...

'' (Clans of Ireland) was founded in 1989 to gather together clan associations; individual clan associations operate throughout the world and produce journals for their septs. The Highland clans held out until the 18th century Jacobite risings. During the Victorian-era, symbolic tartans, crests and badges were retroactively applied to clans. Clan associations built up over time and '' Na Fineachan Gàidhealach'' (The Highland Clans) was founded in 2013.

Human genetics

At the turn of the 21st century, the principles of human genetics and

At the turn of the 21st century, the principles of human genetics and genetic genealogy

Genetic genealogy is the use of genealogical DNA tests, i.e., DNA profiling and DNA testing, in combination with traditional genealogical methods, to infer genetic relationships between individuals. This application of genetics came to be used b ...

were applied to the study of populations of Irish origin. The two other peoples who recorded higher than 85% for R1b in a 2009 study published in the scientific journal, PLOS Biology, were the Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

and the Basques

The Basques ( or ; eu, euskaldunak ; es, vascos ; french: basques ) are a Southwestern European ethnic group, characterised by the Basque language, a common culture and shared genetic ancestry to the ancient Vascones and Aquitanians. Bas ...

.

The development of in-depth studies of DNA sequences known as STRs and SNPs have allowed geneticists to associate subclades with specific Gaelic kindred groupings (and their surnames), vindicating significant elements of Gaelic genealogy

Irish genealogy is the study of individuals and/or families who originated on the island of Ireland.

Origins

Genealogy was cultivated since at least the start of the early Irish historic era. Upon inauguration, Bards and poets are believed to ...

, as found in works such as the ''Leabhar na nGenealach

''Leabhar na nGenealach'' ("Book of Genealogies") is a massive genealogical collection written mainly in the years 1649 to 1650, at the college-house of St. Nicholas' Collegiate Church, Galway, by Dubhaltach MacFhirbhisigh. He continued to add m ...

''. Examples can be taken from the Uí Néill (i.e. – O'Neill, O'Donnell, Gallagher, etc.), who are associated with R-M222 and the Dál gCais

The Dalcassians ( ga, Dál gCais ) are a Gaelic Irish clan, generally accepted by contemporary scholarship as being a branch of the Déisi Muman, that became very powerful in Ireland during the 10th century. Their genealogies claimed descent fr ...

(i.e. – O'Brien, McMahon, Kennedy, etc.) who are associated with R-L226. With regard to Gaelic genetic genealogy studies, these developments in subclades have aided people in finding their original clan group in the case of a non-paternity event, with Family Tree DNA having the largest such database at present.

In 2016, a study analyzing ancient DNA found Bronze Age remains from Rathlin Island

Rathlin Island ( ga, Reachlainn, ; Local Irish dialect: ''Reachraidh'', ; Scots: ''Racherie'') is an island and civil parish off the coast of County Antrim (of which it is part) in Northern Ireland. It is Northern Ireland's northernmost point. ...

in Ireland to be most genetically similar to the modern indigenous populations of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, and to a lesser degree that of England. The majority of the genomes of the insular Celts

The Insular Celts were speakers of the Insular Celtic languages in the British Isles and Brittany. The term is mostly used for the Celtic peoples of the isles up until the early Middle Ages, covering the British–Irish Iron Age, Roman Britain ...

would therefore have emerged by 4,000 years ago. It was also suggested that the arrival of proto-Celtic language, possibly ancestral to Gaelic languages, may have occurred around this time.Neolithic and Bronze Age migration to Ireland and establishment of the insular Atlantic genome"Three Bronze Age individuals from Rathlin Island (2026–1534 cal BC), including one high coverage (10.5×) genome, showed substantial Steppe genetic heritage indicating that the European population upheavals of the third millennium manifested all of the way from southern Siberia to the western ocean. This turnover invites the possibility of accompanying introduction of Indo-European, perhaps early Celtic, language. Irish Bronze Age haplotypic similarity is strongest within modern Irish, Scottish, and Welsh populations, and several important genetic variants that today show maximal or very high frequencies in Ireland appear at this horizon. These include those coding for lactase persistence, blue eye color, Y chromosome R1b haplotypes, and the hemochromatosis C282Y allele; to our knowledge, the first detection of a known Mendelian disease variant in prehistory. These findings together suggest the establishment of central attributes of the Irish genome 4,000 y ago." Several genetic traits found at maximum or very high frequencies in the modern populations of Gaelic ancestry were also observed in the Bronze Age period. These traits include a hereditary disease known as HFE hereditary haemochromatosis, Y-DNA Haplogroup R-M269, lactase persistence and blue eyes. Another trait very common in Gaelic populations is

red hair

Red hair (also known as orange hair and ginger hair) is a hair color found in one to two percent of the human population, appearing with greater frequency (two to six percent) among people of Northern or Northwestern European ancestry and ...

, with 10% of Irish and at least 13% of Scots having red hair, much larger numbers being carriers of variants of the MC1R gene, and which is possibly related to an adaptation to the cloudy conditions of the regional climate.

Demographics

In countries where Gaels live, census records documenting population statistics exist. The following chart shows the number of speakers of a Gaelic language (either "Gaeilge," also known as Irish, "Gàidhlig," known as Scottish Gaelic, or "Gaelg," known as Manx). The question of ethnic identity is slightly more complex, but included below are those who identify as ethnic Irish, Manx orScottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

. It should be taken into account that not all are of Gaelic descent, especially in the case of Scotland, due to the nature of the Lowlands. It also depends on the self-reported response of the individual and so is a rough guide rather than an exact science.

The two comparatively "major" Gaelic nations in the modern era are Ireland (which in the 2002 census had 185,838 people who spoke Irish "daily" and 1,570,894 who were "able" to speak it) and Scotland (58,552 fluent "Gaelic speakers" and 92,400 with "some Gaelic language ability" in the 2001 census). Communities where the languages still are spoken natively are restricted largely to the west coast of each country and especially the Hebrides islands in Scotland. However, a large proportion of the Gaelic-speaking population now lives in the cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh in Scotland, and Donegal Donegal may refer to:

County Donegal, Ireland

* County Donegal, a county in the Republic of Ireland, part of the province of Ulster

* Donegal (town), a town in County Donegal in Ulster, Ireland

* Donegal Bay, an inlet in the northwest of Ireland b ...

, Galway, Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

and Dublin in Ireland. There are about 2,000 Scottish Gaelic speakers in Canada (Canadian Gaelic

Canadian Gaelic or Cape Breton Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig Chanada, or ), often known in Canadian English simply as Gaelic, is a collective term for the dialects of Scottish Gaelic spoken in Atlantic Canada.

Scottish Gaels were settled in Nova Scot ...

dialect), although many are elderly and concentrated in Nova Scotia and more specifically Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

. According to the U.S. Census in 2000, there are more than 25,000 Irish-speakers in the United States, with the majority found in urban areas with large Irish-American communities such as Boston, New York City and Chicago.

Diaspora

As the Western Roman Empire began to collapse, the Irish (along with the Anglo-Saxons) were one of the peoples able to take advantage in Great Britain from the 4th century onwards. The proto-Eóganachta Uí Liatháin and the Déisi Muman of Dyfed both established colonies in today's Wales. Further to the north, the Érainn's Dál Riata colonised Argyll (eventually founding Alba) and there was a significant Gaelic influence in Northumbria and the MacAngus clan arose to the Pictish kingship by the 8th century. GaelicChristian missionaries

A Christian mission is an organized effort for the propagation of the Christian faith. Missions involve sending individuals and groups across boundaries, most commonly geographical boundaries, to carry on evangelism or other activities, such as ...

were also active across the Frankish Empire. With the coming of the Viking Age and their slave markets, Irish were also dispersed in this way across the realms under Viking control; as a legacy, in genetic studies, Icelanders

Icelanders ( is, Íslendingar) are a North Germanic ethnic group and nation who are native to the island country of Iceland and speak Icelandic.

Icelanders established the country of Iceland in mid 930 AD when the Althing (Parliament) met for ...

exhibit high levels of Gaelic-derived mDNA.

Since the fall of Gaelic polities, the Gaels have made their way across parts of the world, successively under the auspices of the Spanish Empire, French Empire

French Empire (french: Empire Français, link=no) may refer to:

* First French Empire, ruled by Napoleon I from 1804 to 1814 and in 1815 and by Napoleon II in 1815, the French state from 1804 to 1814 and in 1815

* Second French Empire, led by Nap ...

, and the British Empire. Their main destinations were Iberia, France, the West Indies, North America (what is today the United States and Canada) and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand). There has also been a mass "internal migration" within Ireland and Britain from the 19th century, with Irish and Scots migrating to the English-speaking industrial cities of London, Dublin, Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Cardiff, Leeds, Edinburgh and others. Many underwent a linguistic "Anglicisation" and eventually merged with Anglo populations.

In a more narrow interpretation of the term ''Gaelic diaspora'', it could be interpreted as referring to the Gaelic-speaking minority among the Irish, Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

, and Manx

Manx (; formerly sometimes spelled Manks) is an adjective (and derived noun) describing things or people related to the Isle of Man:

* Manx people

**Manx surnames

* Isle of Man

It may also refer to:

Languages

* Manx language, also known as Manx ...

diaspora. However, the use of the term "diaspora" in relation to the Gaelic languages (i.e., in a narrowly linguistic rather than a more broadly cultural context) is arguably not appropriate, as it may suggest that Gaelic speakers and people interested in Gaelic necessarily have Gaelic ancestry, or that people with such ancestry naturally have an interest or fluency in their ancestral language. Research shows that this assumption is inaccurate.

History

Origins

In their own

In their own national epic

A national epic is an epic poem or a literary work of epic scope which seeks or is believed to capture and express the essence or spirit of a particular nation—not necessarily a nation state, but at least an ethnic or linguistic group with as ...

contained within medieval works such as the '' Lebor Gabála Érenn'', the Gaels trace the origin of their people to an eponymous ancestor named Goídel Glas

In medieval Irish and Scottish legend, Goídel Glas (Latinised as Gaithelus) is the creator of the Goidelic languages and eponymous ancestor of the Gaels. The tradition can be traced to the 11th-century ''Lebor Gabála Érenn''. A Scottish varia ...

. He is described as a Scythian prince (the grandson of Fénius Farsaid

Fénius Farsaid (also Phoeniusa, Phenius, Féinius; Farsa, Farsaidh, many variant spellings) is a legendary king of Scythia who appears in different versions of Irish mythology. He was the son of Boath, a son of Magog. Other sources describe his ...

), who is credited with creating the Gaelic languages. Goídel's mother is called Scota, described as an Egyptian princess. The Gaels are depicted as wandering from place to place for hundreds of years; they spend time in Egypt, Crete, Scythia, the Caspian Sea and Getulia

Gaetuli was the Romanised name of an ancient Berber tribe inhabiting ''Getulia''. The latter district covered the large desert region south of the Atlas Mountains, bordering the Sahara. Other documents place Gaetulia in pre-Roman times along th ...

, before arriving in Iberia, where their king, Breogán, is said to have founded Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

.

The Gaels are then said to have sailed to Ireland via Galicia in the form of the Milesians, sons of Míl Espáine. The Gaels fight a battle of sorcery with the Tuatha Dé Danann, the gods, who inhabited Ireland at the time. Ériu, a goddess of the land, promises the Gaels that Ireland shall be theirs so long as they pay tribute to her. They agree, and their bard Amergin recites an incantation known as the ''Song of Amergin''. The two groups agree to divide Ireland between them: the Gaels take the world above, while the Tuath Dé take the world below (i.e. the Otherworld).

Ancient

According to the '' Annals of the Four Masters'', the early branches of the Milesian Gaels were the Heremonians, the

According to the '' Annals of the Four Masters'', the early branches of the Milesian Gaels were the Heremonians, the Heberians

Éber Finn (modern spelling: Éibhear Fionn), son of Míl Espáine, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland and one of the founders of the Milesian lineage, to which medieval genealogists traced a ...

and the Irians

In the ''Lebor Gabála Érenn'', a medieval Irish Christian pseudo-history, the Milesians () are the final race to settle in Ireland. They represent the Irish people. The Milesians are Gaels who sail to Ireland from Iberia (Hispania) after spen ...

, descended from the three brothers Érimón, Éber Finn and Ír respectively. Another group were the Ithians, descended from Íth (an uncle of Milesius) who were located in South Leinster (associated with the Brigantes

The Brigantes were Ancient Britons who in pre-Roman times controlled the largest section of what would become Northern England. Their territory, often referred to as Brigantia, was centred in what was later known as Yorkshire. The Greek geogr ...

) but they later became extinct. The Four Masters date the start of Milesian rule from 1700 BCE. Initially, the Heremonians dominated the High Kingship of Ireland from their stronghold of Mide, the Heberians were given Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

and the Irians were given Ulster. At this early point of the Milesian-era, the non-Gaelic Fir Domnann held Leinster and the Fir Ol nEchmacht held what was later known as Connacht (possibly remnants of the Fir Bolg

In medieval Irish myth, the Fir Bolg (also spelt Firbolg and Fir Bholg) are the fourth group of people to settle in Ireland. They are descended from the Muintir Nemid, an earlier group who abandoned Ireland and went to different parts of Europe. ...

).

During the Iron Age there was heightened activity at a number of important royal ceremonial sites, including Tara, Dún Ailinne, Rathcroghan and Emain Macha. Each was associated with a Gaelic tribe. The most important was Tara, where the High King (also known as the King of Tara) was inaugurated on the '' Lia Fáil'' (Stone of Destiny), which stands to this day. According to the Annals, this era also saw, during the 7th century BCE, a branch of the Heremonians known as the Laigin, descending from Úgaine Mór's son Lóegaire Lorc

Lóegaire Lorc, son of Úgaine Mor, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. The ''Lebor Gabála Érenn'' says he succeeded directly after his father was murdered by Bodbchad, although Geoffrey Ke ...

, displacing the Fir Bolg remnants in Leinster. This was also a critical period for the Ulaid (earlier known as the Irians) as their kinsman Rudraige Mór Rudraige may refer to:

*Rudraige mac Dela, son of Dela, legendary High King of Ireland in the 16th or 20th century BC

* Rudraige mac Sithrigi, son of Sitric, legendary High King of Ireland of the 2nd or 3rd century BC

*Rudraige, in medieval Irish m ...

took over the High Kingship in the 3rd century BCE; his offspring would be the subject of the Ulster Cycle of heroic tradition, including the epic '' Táin Bó Cúailnge''. This includes the struggle between Conchobar mac Nessa and Fergus mac Róich.

After regaining power, the Heremonians, in the form of Fíachu Finnolach

Fiacha Finnolach, son of Feradach Finnfechtnach, was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. He took power after killing his predecessor, Fíatach Finn. He ruled for fifteen, seventeen, or twenty-se ...

were overthrown in a 1st-century AD provincial coup. His son, Túathal Techtmar

Túathal Techtmar (; 'the legitimate'), son of Fíachu Finnolach, was a High King of Ireland, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition. He is said to be the ancestor of the Uí Néill and Connachta dynasties through his grandso ...

was exiled to Roman Britain before returning to claim Tara. Based on the accounts of Tacitus, some modern historians associate him with an "Irish prince" said to have been entertained by Agricola, Governor of Britain and speculate at Roman sponsorship. His grandson, Conn Cétchathach, is the ancestor of the Connachta

The Connachta are a group of medieval Irish dynasties who claimed descent from the legendary High King Conn Cétchathach (Conn of the Hundred Battles). The modern western province of Connacht (Irish ''Cúige Chonnacht'', province, literally "f ...

who would dominate the Irish Middle Ages. They gained control of what would now be named Connacht. Their close relatives the Érainn (both groups descend from Óengus Tuirmech Temrach) and the Ulaid would later lose out to them in Ulster, as the descendants of the Three Collas in Airgíalla

Airgíalla (Modern Irish: Oirialla, English: Oriel, Latin: ''Ergallia'') was a medieval Irish over-kingdom and the collective name for the confederation of tribes that formed it. The confederation consisted of nine minor kingdoms, all independe ...

and Niall Noígíallach

Niall ''Noígíallach'' (; Old Irish "having nine hostages"), or Niall of the Nine Hostages, was a legendary, semi-historical Irish king who was the ancestor of the Uí Néill dynasties that dominated Ireland from the 6th to the 10th centuries. ...

in Ailech extended their hegemony.

The Gaels emerged into the clear historical record during the classical era, with ogham inscriptions and quite detailed references in Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

ethnography (most notably by Ptolemy). The Roman Empire conquered most of Britain in the 1st century, but did not conquer Ireland or the far north of Britain. The Gaels had relations with the Roman world, mostly through trade. Roman jewellery and coins have been found at several Irish royal sites, for example. Gaels, known to the Romans as ''Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. At first it referred to all Gaels, whether in Ireland or Great Britain, but l ...

'', also carried out raids on Roman Britain, together with the Picts. These raids increased in the 4th century, as Roman rule in Britain began to collapse. This era was also marked by a Gaelic presence in Britain; in what is today Wales, the Déisi founded the Kingdom of Dyfed and the Uí Liatháin founded Brycheiniog. There was also some Irish settlement in Cornwall. To the north, the Dál Riata are held to have established a territory in Argyll and the Hebrides.

Medieval

Christianity reached Ireland during the 5th century, most famously through a Romano-British slave

Christianity reached Ireland during the 5th century, most famously through a Romano-British slave Patrick Patrick may refer to:

* Patrick (given name), list of people and fictional characters with this name

* Patrick (surname), list of people with this name

People

* Saint Patrick (c. 385–c. 461), Christian saint

*Gilla Pátraic (died 1084), Patrick ...

, but also through Gaels such as Declán, Finnian and the Twelve Apostles of Ireland

The Twelve Apostles of Ireland (also known as Twelve Apostles of Erin, ir, Dhá Aspal Déag na hÉireann) were twelve early Irish monastic saints of the sixth century who studied under St Finnian (d. 549) at his famous monastic school Clonar ...

. The abbot and the monk eventually took over certain cultural roles of the '' aos dána'' (not least the roles of ''druí

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient Celts, Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accoun ...

'' and ''seanchaí

A seanchaí ( or – plural: ) is a traditional Gaelic storyteller/historian. In Scottish Gaelic the word is (; plural ). The word is often anglicised as shanachie ( ).

The word ''seanchaí'', which was spelled ''seanchaidhe'' (plural ''se ...

'') as the oral culture of the Gaels was transmitted to script by the arrival of literacy. Thus Christianity in Ireland during this early time retained elements of Gaelic culture.

In the Middle Ages, Gaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland ( ga, Éire Ghaelach) was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late prehistoric era until the early 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Normans co ...

was divided into a hierarchy of territories ruled by a hierarchy of kings or chiefs. The smallest territory was the '' túath'' (plural: ''túatha''), which was typically the territory of a single kin-group. Several ''túatha'' formed a ''mór túath'' (overkingdom), which was ruled by an overking. Several overkingdoms formed a ''cóiced'' (province), which was ruled by a provincial king. In the early Middle Ages the ''túath'' was the main political unit, but during the following centuries the overkings and provincial kings became ever more powerful. By the 6th century, the division of Ireland into two spheres of influence ( Leath Cuinn and Leath Moga) was largely a reality. In the south, the influence of the Eóganachta based at Cashel grew further, to the detriment of Érainn clans such as the Corcu Loígde

The Corcu Loígde (Corcu Lóegde, Corco Luigde, Corca Laoighdhe, Laidhe), meaning Gens of the Calf Goddess, also called the Síl Lugdach meic Itha, were a kingdom centred in West County Cork who descended from the proto-historical rulers of Mun ...

and Clann Conla. Through their vassals the Déisi (descended from Fiacha Suidhe

Fiacha (earlier Fíachu) is a name borne by numerous figures from Irish history and mythology, including:

* Fiacha Cennfinnán, High King of Ireland in the 16th or 20th century BC

* Fiacha mac Delbaíth, High King in the 14th or 18th century BC

* ...

and later known as the Dál gCais

The Dalcassians ( ga, Dál gCais ) are a Gaelic Irish clan, generally accepted by contemporary scholarship as being a branch of the Déisi Muman, that became very powerful in Ireland during the 10th century. Their genealogies claimed descent fr ...

), Munster was extended north of the River Shannon

The River Shannon ( ga, Abhainn na Sionainne, ', '), at in length, is the longest river in the British Isles. It drains the Shannon River Basin, which has an area of , – approximately one fifth of the area of the island of Ireland.

The Shan ...

, laying the foundations for Thomond. Aside from their gains in Ulster (excluding the Érainn's Ulaid), the Uí Néill's southern branch had also pushed down into Mide and Brega

Brega , also known as ''Mersa Brega'' or ''Marsa al-Brega'' ( ar, مرسى البريقة , i.e. "Brega Seaport"), is a complex of several smaller towns, industry installations and education establishments situated in Libya on the Gulf of Sidra, ...

. By the 9th century, some of the most powerful kings were being acknowledged as High King of Ireland

High King of Ireland ( ga, Ardrí na hÉireann ) was a royal title in Gaelic Ireland held by those who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over all of Ireland. The title was held by historical kings and later sometimes assigned ana ...

.

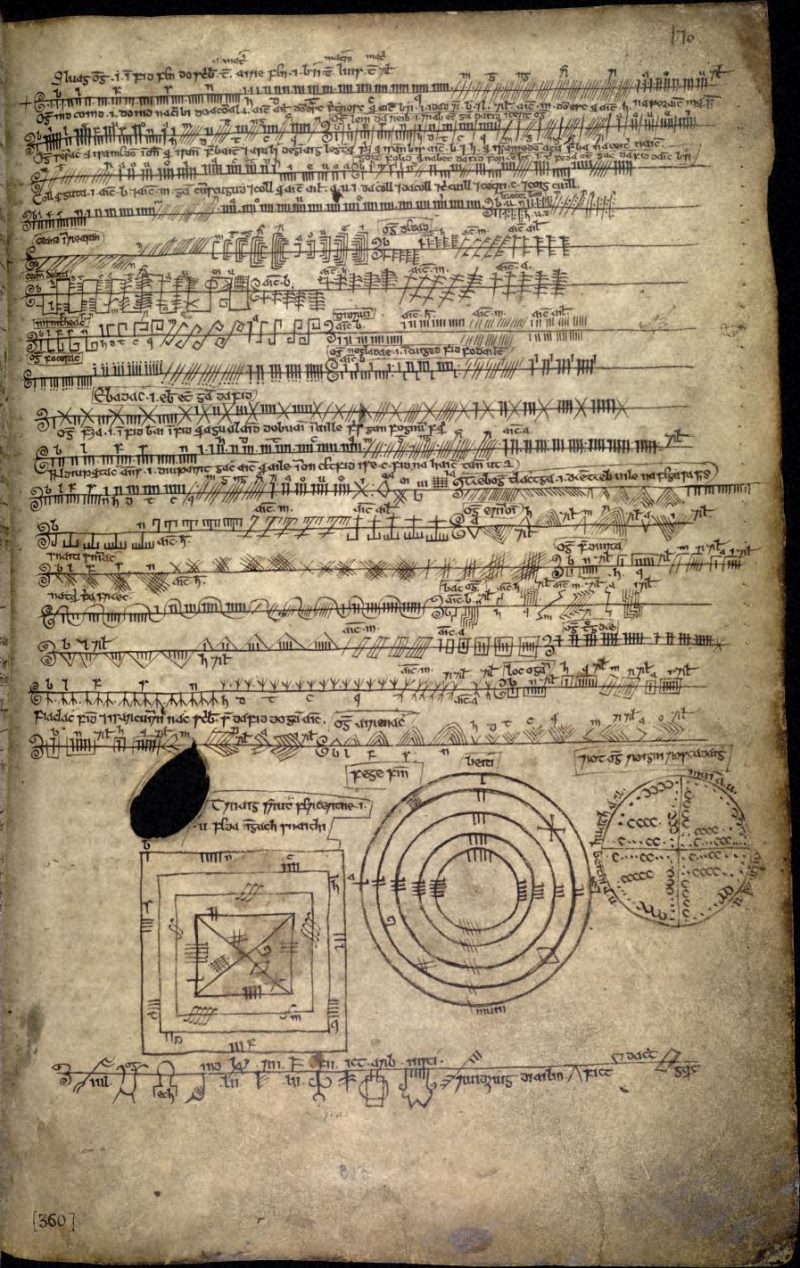

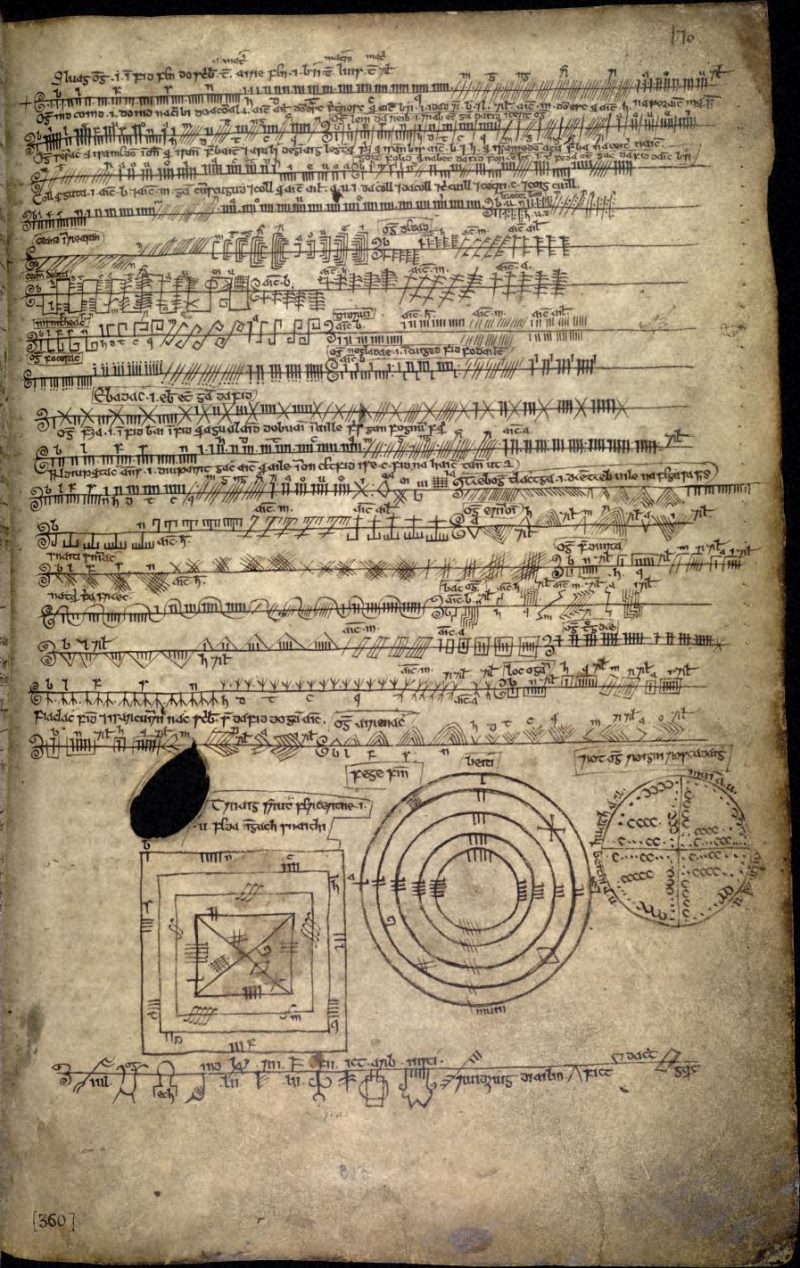

Some, particularly champions of Christianity, hold the 6th to 9th centuries to be a Golden Age for the Gaels. This is due to the influence which the Gaels had across Western Europe as part of their Christian missionary activities. Similar to the Desert Fathers, Gaelic monastics were known for their

Some, particularly champions of Christianity, hold the 6th to 9th centuries to be a Golden Age for the Gaels. This is due to the influence which the Gaels had across Western Europe as part of their Christian missionary activities. Similar to the Desert Fathers, Gaelic monastics were known for their asceticism

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

. Some of the most celebrated figures of this time were Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

, Aidan

Aidan or Aiden is a modern version of a number of Celtic language names, including the Irish male given name ''Aodhán'', the Scottish Gaelic given name Aodhan and the Welsh name Aeddan. Phonetic variants, such as spelled with an "e" instead of ...

, Columbanus

Columbanus ( ga, Columbán; 543 – 21 November 615) was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in pr ...

and others. Learned in Greek and Latin during an age of cultural collapse, the Gaelic scholars were able to gain a presence at the court of the Carolingian

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

Frankish Empire; perhaps the best known example is Johannes Scotus Eriugena

John Scotus Eriugena, also known as Johannes Scotus Erigena, John the Scot, or John the Irish-born ( – c. 877) was an Irish people, Irish Neoplatonism, Neoplatonist Philosophy, philosopher, Theology, theologian and poet of the Early M ...

. Aside from their activities abroad, insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style dif ...

flourished domestically, with artifacts such as the Book of Kells

The Book of Kells ( la, Codex Cenannensis; ga, Leabhar Cheanannais; Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS A. I. 8 sometimes known as the Book of Columba) is an illuminated manuscript Gospel book in Latin, containing the four Gospels of the New ...

and Tara Brooch surviving. Clonmacnoise, Glendalough, Clonard, Durrow and Inis Cathaigh

Inis Cathaigh or Scattery Island is an island in the Shannon Estuary, Ireland, off the coast of Kilrush, County Clare. The island is home to a lighthouse, a ruined monastery associated with Saint Senan, an Irish round tower and the remains of a ...

are some of the more prominent Ireland-based monasteries founded during this time.

There is some evidence in early Icelandic sagas such as the '' Íslendingabók'' that the Gaels may have visited the Faroe Islands and Iceland before the Norse, and that Gaelic monks known as '' papar'' (meaning father) lived there before being driven out by the incoming Norsemen.

The late 8th century heralded outside involvement in Gaelic affairs, as Norsemen from Scandinavia, known as the Vikings, began to raid and pillage settlements. The earliest recorded raids were on Rathlin

Rathlin Island ( ga, Reachlainn, ; Local Irish dialect: ''Reachraidh'', ; Scots: ''Racherie'') is an island and civil parish off the coast of County Antrim (of which it is part) in Northern Ireland. It is Northern Ireland's northernmost point. ...

and Iona

Iona (; gd, Ì Chaluim Chille (IPA: �iːˈxaɫ̪ɯimˈçiʎə, sometimes simply ''Ì''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there ...

in 795; these hit and run attacks continued for some time until the Norsemen began to settle in the 840s at Dublin (setting up a large slave market), Limerick, Waterford and elsewhere. The Norsemen also took most of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man from the Dál Riata clans and established the Kingdom of the Isles.

The monarchy of Pictland had kings of Gaelic origin, since the 7th century with Bruide mac Der-Ilei

Bruide mac Der-Ilei (died 706) was king of the Picts from 697 until 706. He became king when Taran was deposed in 697.

He was the brother of his successor Nechtan. It has been suggested that Bruide's father was Dargart mac Finguine (d. 686) of t ...

, around the times of the '' Cáin Adomnáin''. However, Pictland remained a separate realm from Dál Riata, until the latter gained full hegemony during the reign of Kenneth MacAlpin from the House of Alpin, whereby Dál Riata and Pictland were merged to form the Kingdom of Alba. This meant an acceleration of Gaelicisation in the northern part of Great Britain. The Battle of Brunanburh in 937 defined the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of England as the hegemonic force in Great Britain, over a Gaelic-Viking alliance.

After a spell when the Norsemen were driven from Dublin by Leinsterman Cerball mac Muirecáin

Cerball mac Muirecáin (died 909) was Kings of Leinster, king of Leinster. He was the son of Muirecán mac Diarmata and a member of the Uí Fáeláin, the descendants of Fáelán mac Murchado (died 738), of one of three septs of the Uí Dúnlainge ...

, they returned in the reign of Niall Glúndub

Niall Glúndub mac Áeda (Modern Irish: ''Niall Glúndubh mac Aodha'', "Niall Black-Knee, son of Áed"; died 14 September 919) was a 10th-century Irish king of the Cenél nEógain and High King of Ireland. Many Irish kin groups were members of the ...

, heralding a second Viking period. The Dublin Norse—some of them, such as Uí Ímair king Ragnall ua Ímair now partly Gaelicised as the Norse-Gaels—were a serious regional power, with territories across Northumbria and York. At the same time, the Uí Néill branches were involved in an internal power struggle for hegemony between the northern or southern branches. Donnchad Donn raided Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

and took Cellachán Caisil

Cellachán mac Buadacháin (died 954), called Cellachán Caisil, was King of Munster.

Biography

The son of Buadachán mac Lachtnai, he belonged to the Cashel branch of the Eóganachta kindred, the Eóganacht Chaisil. The last of his cognatic ance ...

of the Eóganachta hostage. The destabilisation led to the rise of the Dál gCais and Brian Bóruma

Brian Boru ( mga, Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig; modern ga, Brian Bóramha; 23 April 1014) was an Irish king who ended the domination of the High King of Ireland, High Kingship of Ireland by the Uí Néill and probably ended Viking invasion/domi ...

. Through military might, Brian went about building a Gaelic Imperium under his High Kingship, even gaining the submission of Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill. They were involved in a series of battles against the Vikings: Tara, Glenmama and Clontarf. The last of these saw Brian's death in 1014. Brian's campaign is glorified in the '' Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib'' ("The War of the Gaels with the Foreigners").

The Irish Church became closer to Continental models with the Synod of Ráth Breasail and the arrival of the Cistercians

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

. There was also more trade and communication with Normanised Britain and France. Between themselves, the Ó Briain

The O'Brien dynasty ( ga, label=Classical Irish, Ua Briain; ga, label=Modern Irish, Ó Briain ; genitive ''Uí Bhriain'' ) is a noble house of Munster, founded in the 10th century by Brian Boru of the Dál gCais (Dalcassians). After becoming ...

and the Ó Conchobhair

Ó, ó ( o-acute) is a letter in the Czech, Emilian-Romagnol, Faroese, Hungarian, Icelandic, Kashubian, Polish, Slovak, and Sorbian languages. This letter also appears in the Afrikaans, Catalan, Dutch, Irish, Nynorsk, Bokmål, Occitan, Po ...

attempted to build a national monarchy.

The remainder of the Middle Ages was marked by conflict between Gaels and Anglo-Normans. The Norman invasion of Ireland took place in stages during the late 12th century. Norman mercenaries landed in Leinster in 1169 at the request of Diarmait Mac Murchada, who sought their help in regaining his throne. By 1171 the Normans had gained control of Leinster, and King Henry II of England, with the backing of the Papacy, established the Lordship of Ireland. The Norman kings of England claimed sovereignty over this territory, leading to centuries of conflict between the Normans and the native Irish. At this time, a literary anti-Gaelic sentiment was born and developed by the likes of Gerald of Wales as part of a propaganda campaign (with a Gregorian "reform" gloss) to justify taking Gaelic lands. Scotland also came under Anglo-Norman influence in the 12th century. The Davidian Revolution saw the Normanisation of Scotland's monarchy, government and church; the founding of

The remainder of the Middle Ages was marked by conflict between Gaels and Anglo-Normans. The Norman invasion of Ireland took place in stages during the late 12th century. Norman mercenaries landed in Leinster in 1169 at the request of Diarmait Mac Murchada, who sought their help in regaining his throne. By 1171 the Normans had gained control of Leinster, and King Henry II of England, with the backing of the Papacy, established the Lordship of Ireland. The Norman kings of England claimed sovereignty over this territory, leading to centuries of conflict between the Normans and the native Irish. At this time, a literary anti-Gaelic sentiment was born and developed by the likes of Gerald of Wales as part of a propaganda campaign (with a Gregorian "reform" gloss) to justify taking Gaelic lands. Scotland also came under Anglo-Norman influence in the 12th century. The Davidian Revolution saw the Normanisation of Scotland's monarchy, government and church; the founding of burgh

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Burg ...

s, which became mainly English-speaking; and the royally-sponsored immigration of Norman aristocrats. This Normanisation was mainly limited to the Scottish Lowlands

The Lowlands ( sco, Lallans or ; gd, a' Ghalldachd, , place of the foreigners, ) is a cultural and historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Lowlands and the Highlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowl ...

. In Ireland, the Normans carved out their own semi-independent lordships, but many Gaelic Irish kingdoms remained outside Norman control and gallowglass warriors were brought in from the Highlands to fight for various Irish kings.

In 1315, a Scottish army landed in Ireland as part of Scotland's war against England. It was led by Edward Bruce

Edward Bruce, Earl of Carrick ( Norman French: ; mga, Edubard a Briuis; Modern Scottish Gaelic: gd, Eideard or ; – 14 October 1318), was a younger brother of Robert the Bruce, King of Scots. He supported his brother in the 1306–1314 st ...

, brother of Scottish king Robert the Bruce. Despite his own Norman ancestry, Edward urged the Irish to ally with the Scots by invoking a shared Gaelic ancestry and culture, and most of the northern kings acknowledged him as High King of Ireland. However, the campaign ended three years later with Edward's defeat and death in the Battle of Faughart.

A Gaelic Irish resurgence began in the mid-14th century: English royal control shrank to an area known as the Pale and, outside this, many Norman lords adopted Gaelic culture, becoming culturally Gaelicised. The English government tried to prevent this through the Statutes of Kilkenny (1366), which forbade English settlers from adopting Gaelic culture, but the results were mixed and particularly in the West, some Normans became Gaelicised.

Imperial

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Gaels were affected by the policies of the Tudors and theStewarts Stewart's or Stewarts can refer to:

* Stewart's Fountain Classics, brand of soft drink

**Stewart's Restaurants, chain of restaurants where the soft drink was originally sold

* Stewart's wilt, bacterial disease affecting maize

* Stewart's (departmen ...

who sought to anglicise the population and bring both Ireland and the Highlands under stronger centralised control, as part of what would become the British Empire. In 1542, Henry VIII of England declared the Lordship of Ireland a Kingdom

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''a'' (pronounced ), plural ''ae ...

and himself King of Ireland. The new English, whose power lay in the Pale of Dublin, then began to conquer the island. Gaelic kings were encouraged to apply for a surrender and regrant: to surrender their lands to the king, and then have them regranted as freeholds. Those who surrendered were also expected to follow English law and customs, speak English, and convert to the Protestant Anglican Church. Decades of conflict followed in the reign of Elizabeth I, culminating in the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

(1594–1603). The war ended in defeat for the Irish Gaelic alliance, and brought an end to the independence of the last Irish Gaelic kingdoms.

In 1603, with the Union of the Crowns, King James of Scotland also became king of England and Ireland. James saw the Gaels as a barbarous and rebellious people in need of civilising, and believed that Gaelic culture should be wiped out. Also, while most of Britain had converted to Protestantism, most Gaels had held on to Catholicism. When the leaders of the Irish Gaelic alliance fled Ireland in 1607, their lands were confiscated. James set about colonising this land with English-speaking Protestant settlers from Britain, in what became known as the Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster ( gle, Plandáil Uladh; Ulster-Scots: ''Plantin o Ulstèr'') was the organised colonisation (''plantation'') of Ulstera province of Irelandby people from Great Britain during the reign of King James I. Most of the sett ...

. It was meant to establish a loyal British Protestant colony in Ireland's most rebellious region and to sever Gaelic Ulster's links with Gaelic Scotland. In Scotland, James attempted to subdue the Gaelic clans and suppress their culture through laws such as the Statutes of Iona

The Statutes of Iona, passed in Scotland in 1609, required that Highland Scottish clan chiefs send their heirs to Lowland Scotland to be educated in English-speaking Protestant schools. As a result, some clans, such as the MacDonalds of Sleat and ...

. He also attempted to colonise the Isle of Lewis

The Isle of Lewis ( gd, Eilean Leòdhais) or simply Lewis ( gd, Leòdhas, ) is the northern part of Lewis and Harris, the largest island of the Western Isles or Outer Hebrides archipelago in Scotland. The two parts are frequently referred to as ...

with settlers from the Lowlands.

Since then, the Gaelic language has gradually diminished in most of Ireland and Scotland. The 19th century was the turning point as The Great Hunger

The Great Famine ( ga, an Gorta Mór ), also known within Ireland as the Great Hunger or simply the Famine and outside Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a ...

in Ireland, and across the Irish Sea the Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances ( gd, Fuadaichean nan Gàidheal , the "eviction of the Gaels") were the evictions of a significant number of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands, mostly in two phases from 1750 to 1860.

The first phase resulte ...

, caused mass emigration (leading to Anglicisation, but also a large diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

). The language was rolled back to the Gaelic strongholds of the north west of Scotland, the west of Ireland and Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

in Nova Scotia.

Modern

TheGaelic revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

also occurred in the 19th century, with organisations such as '' Conradh na Gaeilge'' and ''An Comunn Gàidhealach

An Comunn Gàidhealach (; literally "The Gaelic Association"), commonly known as An Comunn, is a Scottish organisation that supports and promotes the Scottish Gaelic language and Scottish Gaelic culture and history at local, national and internat ...

'' attempting to restore the prestige of Gaelic culture and the socio-communal hegemony of the Gaelic languages. Many of the participants in the Irish Revolution

The revolutionary period in Irish history was the period in the 1910s and early 1920s when Irish nationalist opinion shifted from the Home Rule-supporting Irish Parliamentary Party to the republican Sinn Féin movement. There were several wa ...

of 1912–1923 were inspired by these ideals and so when a sovereign state was formed (the Irish Free State), post-colonial

Postcolonialism is the critical academic study of the cultural, political and economic legacy of colonialism and imperialism, focusing on the impact of human control and exploitation of colonized people and their lands. More specifically, it is a ...

enthusiasm for the re- Gaelicisation of Ireland was high and promoted through public education. Results were very mixed however and the '' Gaeltacht'' where native speakers lived continued to retract. In the 1960s and 70s, pressure from groups such as ''Misneach'' (supported by Máirtín Ó Cadhain

Máirtín Ó Cadhain (; 1906 – 18 October 1970) was one of the most prominent Irish language writers of the twentieth century. Perhaps best known for his 1949 novel ''Cré na Cille'', Ó Cadhain played a key role in reintroducing literary mod ...

), the ''Gluaiseacht Chearta Siabhialta na Gaeltachta

Gluaiseacht Cearta Sibhialta na Gaeltachta (English: "The Gaeltacht Civil Rights Movement") or Coiste Cearta Síbialta na Gaeilge (English: Irish Language Civil Rights Committee"), was a pressure group campaigning for social, economic and cultu ...

'' and others; particularly in Connemara; paved the way for the creation of development agencies such as '' Údarás na Gaeltachta'' and state media (television and radio) in Irish.

The last native speaker of Manx died in the 1970s, though use of the Manx language never fully ceased. There is now a resurgent language movement and Manx is once again taught in all schools as a second language and in some as a first language.

Culture

Gaelic society was traditionally made up of kin groups known as clans, each with its own territory and headed by a male chieftain.Succession

Succession is the act or process of following in order or sequence.

Governance and politics

*Order of succession, in politics, the ascension to power by one ruler, official, or monarch after the death, resignation, or removal from office of ...

to the chieftainship or kingship was through tanistry. When a man became chieftain or king, a relative was elected to be his deputy or 'tanist' (''tánaiste''). When the chieftain or king died, his tanist would automatically succeed him. The tanist had to share the same great-grandfather as his predecessor (i.e. was of the same ''derbfhine