Fugue For The Pepper Players- By Dave Baldwin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

A tonal answer is usually called for when the subject begins with a prominent dominant note, or where there is a prominent dominant note very close to the beginning of the subject. To prevent an undermining of the music's sense of

A tonal answer is usually called for when the subject begins with a prominent dominant note, or where there is a prominent dominant note very close to the beginning of the subject. To prevent an undermining of the music's sense of  The countersubject is written in

The countersubject is written in

Only one entry of the subject must be heard in its completion in a ''stretto''. However, a ''stretto'' in which the subject/answer is heard in completion in all voices is known as ''stretto maestrale'' or ''grand stretto''. ''Strettos'' may also occur by inversion, augmentation and diminution. A fugue in which the opening exposition takes place in ''stretto'' form is known as a ''close fugue'' or ''stretto fugue'' (see for example, the ''Gratias agimus tibi'' and ' choruses from J.S. Bach's

Only one entry of the subject must be heard in its completion in a ''stretto''. However, a ''stretto'' in which the subject/answer is heard in completion in all voices is known as ''stretto maestrale'' or ''grand stretto''. ''Strettos'' may also occur by inversion, augmentation and diminution. A fugue in which the opening exposition takes place in ''stretto'' form is known as a ''close fugue'' or ''stretto fugue'' (see for example, the ''Gratias agimus tibi'' and ' choruses from J.S. Bach's

The parts of the

The parts of the

]

]

]

]

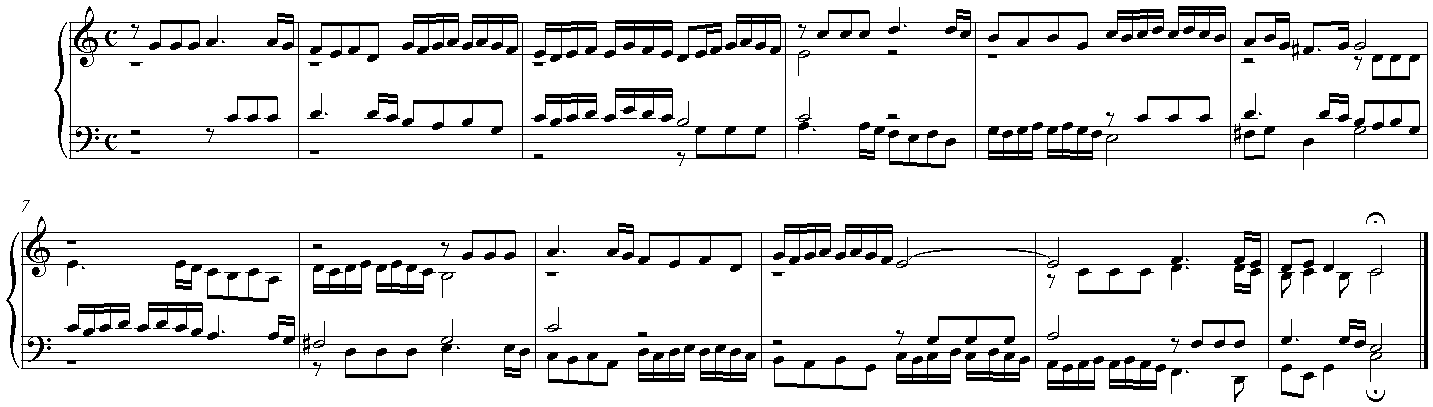

Score

, J. S. Bach's ''

Fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier

(viewable in Adob

o

Analyses of J. S. Bach's ''Well-Tempered Clavier'' with accompanying recordings

* * * {{Authority control Polyphonic form Classical music styles

In

In music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

, a fugue () is a contrapuntal

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradi ...

compositional technique in two or more voices

Voices or The Voices may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Voices'' (1920 film), by Chester M. De Vonde, with Diana Allen

* ''Voices'' (1973 film), a British horror film

* ''Voices'' (1979 film), a film by Robert Markowitz

* ''Voices'' (19 ...

, built on a subject

Subject ( la, subiectus "lying beneath") may refer to:

Philosophy

*''Hypokeimenon'', or ''subiectum'', in metaphysics, the "internal", non-objective being of a thing

**Subject (philosophy), a being that has subjective experiences, subjective cons ...

(a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation

Imitation (from Latin ''imitatio'', "a copying, imitation") is a behavior whereby an individual observes and replicates another's behavior. Imitation is also a form of that leads to the "development of traditions, and ultimately our culture. I ...

(repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the course of the composition. It is not to be confused with a ''fuguing tune

The fuguing tune (often fuging tune) is a variety of Anglo-American vernacular choral music. It first flourished in the mid-18th century and continues to be composed today.

Description

Fuguing tunes are sacred music, specifically, Protestant hym ...

'', which is a style of song popularized by and mostly limited to early American (i.e. shape note

Shape notes are a musical notation designed to facilitate congregational and social singing. The notation, introduced in late 18th century England, became a popular teaching device in American singing schools. Shapes were added to the noteh ...

or "Sacred Harp

Sacred Harp singing is a tradition of sacred choral music that originated in New England and was later perpetuated and carried on in the American South. The name is derived from ''The Sacred Harp'', a ubiquitous and historically important tune ...

") music and West Gallery music

__NOTOC__

West gallery music, also known as Georgian psalmody, refers to the sacred music (metrical psalms, with a few hymns and anthems) sung and played in English parish churches, as well as nonconformist chapels, from 1700 to around 1850. In ...

. A fugue usually has three main sections: an exposition

Exposition (also the French for exhibition) may refer to:

*Universal exposition or World's Fair

*Expository writing

**Exposition (narrative)

*Exposition (music)

*Trade fair

* ''Exposition'' (album), the debut album by the band Wax on Radio

*Exposi ...

, a development

Development or developing may refer to:

Arts

*Development hell, when a project is stuck in development

*Filmmaking, development phase, including finance and budgeting

*Development (music), the process thematic material is reshaped

*Photographi ...

and a final entry that contains the return of the subject in the fugue's tonic key. Some fugues have a recapitulation.

In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, the term was widely used to denote any works in canonic style; by the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, it had come to denote specifically imitative works. Since the 17th century, the term ''fugue'' has described what is commonly regarded as the most fully developed procedure of imitative counterpoint.

Most fugues open with a short main theme, the subject, which then sounds successively in each voice

The human voice consists of sound made by a human being using the vocal tract, including talking, singing, laughing, crying, screaming, shouting, humming or yelling. The human voice frequency is specifically a part of human sound production in ...

(after the first voice is finished stating the subject, a second voice repeats the subject at a different pitch, and other voices repeat in the same way); when each voice has completed the subject, the ''exposition'' is complete. This is often followed by a connecting passage, or ''episode'', developed from previously heard material; further "entries" of the subject then are heard in related keys. Episodes (if applicable) and entries are usually alternated until the "final entry" of the subject, by which point the music has returned to the opening key, or tonic, which is often followed by closing material, the coda

Coda or CODA may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* Movie coda, a post-credits scene

* ''Coda'' (1987 film), an Australian horror film about a serial killer, made for television

*''Coda'', a 2017 American experimental film from Na ...

."Fugue", ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music'', fourth edition, ed. Michael Kennedy (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 1996). In this sense, a fugue is a style of composition, rather than a fixed structure.

The form evolved during the 18th century from several earlier types of contrapuntal compositions, such as imitative ricercar

A ricercar ( , ) or ricercare ( , ) is a type of late Renaissance and mostly early Baroque instrumental composition. The term ''ricercar'' derives from the Italian verb which means 'to search out; to seek'; many ricercars serve a preludial functi ...

s, capriccios, canzona

The canzona is an Italian musical form derived from the Franco-Flemish and Parisian chansons, and during Giovanni Gabrieli's lifetime was frequently spelled canzona, though both earlier and later the singular was spelled either canzon or canzone ...

s, and fantasias. The famous fugue composer Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

(1685–1750) shaped his own works after those of Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck ( ; April or May, 1562 – 16 October 1621) was a Dutch composer, organist, and pedagogue whose work straddled the end of the Renaissance and beginning of the Baroque eras. He was among the first major keyboard compo ...

(1562-1621), Johann Jakob Froberger

Johann Jakob Froberger ( baptized 19 May 1616 – 7 May 1667) was a German Baroque composer, keyboard virtuoso, and organist. Among the most famous composers of the era, he was influential in developing the musical form of the suite of dances in h ...

(1616–1667), Johann Pachelbel

Johann Pachelbel (baptised – buried 9 March 1706; also Bachelbel) was a German composer, organist, and teacher who brought the south German organ schools to their peak. He composed a large body of sacred and secularity, secular music, and h ...

(1653–1706), Girolamo Frescobaldi

Girolamo Alessandro Frescobaldi (; also Gerolamo, Girolimo, and Geronimo Alissandro; September 15831 March 1643) was an Italian composer and virtuoso keyboard player. Born in the Duchy of Ferrara, he was one of the most important composers of k ...

(1583–1643), Dieterich Buxtehude

Dieterich Buxtehude (; ; born Diderik Hansen Buxtehude; c. 1637 – 9 May 1707) was a Danish organist and composer of the Baroque period, whose works are typical of the North German organ school. As a composer who worked in various vocal ...

(c. 1637–1707) and others. With the decline of sophisticated styles at the end of the baroque period

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including t ...

, the fugue's central role waned, eventually giving way as sonata form

Sonata form (also ''sonata-allegro form'' or ''first movement form'') is a musical form, musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle ...

and the symphony orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families.

There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* bowed string instruments, such as the violin, viola, ce ...

rose to a dominant position. Nevertheless, composers continued to write and study fugues for various purposes; they appear in the works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

(1756–1791) and Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

(1770–1827), as well as modern composers such as Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his Symphony No. 1 (Shostakovich), First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throug ...

(1906–1975).

Etymology

The English term ''fugue'' originated in the 16th century and is derived from the French word ''fugue'' or the Italian ''fuga''. This in turn comes from Latin, also ''fuga'', which is itself related to both ''fugere'' ("to flee") and ''fugare'' ("to chase"). The adjectival form is ''fugal''. Variants include ''fughetta'' (literally, "a small fugue") and ''fugato'' (a passage in fugal style within another work that is not a fugue).Musical outline

A fugue begins with the ''exposition

Exposition (also the French for exhibition) may refer to:

*Universal exposition or World's Fair

*Expository writing

**Exposition (narrative)

*Exposition (music)

*Trade fair

* ''Exposition'' (album), the debut album by the band Wax on Radio

*Exposi ...

'' and is written according to certain predefined rules; in later portions the composer has more freedom, though a logical key structure is usually followed. Further entries of the subject will occur throughout the fugue, repeating the accompanying material at the same time. The various entries may or may not be separated by ''episodes''.

What follows is a chart displaying a fairly typical fugal outline, and an explanation of the processes involved in creating this structure.

::S = subject; A = answer; CS = countersubject; T = tonic; D = dominant

Exposition

A fugue begins with the exposition of its subject in one of the voices alone in the tonic key. G. M. Tucker and Andrew V. Jones, "Fugue", in ''The Oxford Companion to Music'', ed. Alison Latham (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002). After the statement of the subject, a second voice enters and states the subject with the subject transposed to another key (usually the dominant orsubdominant

In music, the subdominant is the fourth tonal degree () of the diatonic scale. It is so called because it is the same distance ''below'' the tonic as the dominant is ''above'' the tonicin other words, the tonic is the dominant of the subdomina ...

), which is known as the ''answer''. To make the music run smoothly, it may also have to be altered slightly. When the answer is an exact copy of the subject to the new key, with identical intervals to the first statement, it is classified as a ''real answer''; if the intervals are altered to maintain the key it is a ''tonal answer''.

A tonal answer is usually called for when the subject begins with a prominent dominant note, or where there is a prominent dominant note very close to the beginning of the subject. To prevent an undermining of the music's sense of

A tonal answer is usually called for when the subject begins with a prominent dominant note, or where there is a prominent dominant note very close to the beginning of the subject. To prevent an undermining of the music's sense of key

Key or The Key may refer to:

Common meanings

* Key (cryptography), a piece of information that controls the operation of a cryptography algorithm

* Key (lock), device used to control access to places or facilities restricted by a lock

* Key (map ...

, this note is transposed up a fourth to the tonic rather than up a fifth to the supertonic

In music, the supertonic is the second degree () of a diatonic scale, one whole step above the tonic. In the movable do solfège system, the supertonic note is sung as ''re''.

The triad built on the supertonic note is called the supertonic chor ...

. Answers in the subdominant are also employed for the same reason.

While the answer is being stated, the voice in which the subject was previously heard continues with new material. If this new material is reused in later statements of the subject, it is called a ''countersubject

In music, a subject is the material, usually a recognizable melody, upon which part or all of a composition is based. In forms other than the fugue, this may be known as the theme.

Characteristics

A subject may be perceivable as a complete mus ...

''; if this accompanying material is only heard once, it is simply referred to as '' free counterpoint''.

The countersubject is written in

The countersubject is written in invertible counterpoint

In music theory, an inversion is a type of change to intervals, chords, voices (in counterpoint), and melodies. In each of these cases, "inversion" has a distinct but related meaning. The concept of inversion also plays an important role in mu ...

at the octave or fifteenth. The distinction is made between the use of free counterpoint and regular countersubjects accompanying the fugue subject/answer, because in order for a countersubject to be heard accompanying the subject in more than one instance, it must be capable of sounding correctly above or below the subject, and must be conceived, therefore, in invertible (double) counterpoint.

In tonal music, invertible contrapuntal lines must be written according to certain rules because several intervallic combinations, while acceptable in one particular orientation, are no longer permissible when inverted. For example, when the note "G" sounds in one voice above the note "C" in lower voice, the interval of a fifth is formed, which is considered consonant

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract. Examples are and pronounced with the lips; and pronounced with the front of the tongue; and pronounced wit ...

and entirely acceptable. When this interval is inverted ("C" in the upper voice above "G" in the lower), it forms a fourth, considered a dissonance in tonal contrapuntal practice, and requires special treatment, or preparation and resolution, if it is to be used. The countersubject, if sounding at the same time as the answer, is transposed to the pitch of the answer. Each voice then responds with its own subject or answer, and further countersubjects or free counterpoint may be heard.

When a tonal answer is used, it is customary for the exposition to alternate subjects (S) with answers (A), however, in some fugues this order is occasionally varied: e.g., see the SAAS arrangement of Fugue No. 1 in C Major, BWV 846, from J.S. Bach's '' Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1''. A brief codetta

In music, a coda () (Italian for "tail", plural ''code'') is a passage that brings a piece (or a movement) to an end. It may be as simple as a few measures, or as complex as an entire section.

In classical music

The presence of a coda as a stru ...

is often heard connecting the various statements of the subject and answer. This allows the music to run smoothly. The codetta, just as the other parts of the exposition, can be used throughout the rest of the fugue.

The first answer must occur as soon after the initial statement of the subject as possible; therefore the first codetta is often extremely short, or not needed. In the above example, this is the case: the subject finishes on the quarter note

A quarter note (American) or crotchet ( ) (British) is a note (music), musical note played for one quarter of the duration of a whole note (or semibreve). Quarter notes are notated with a filled-in oval note head and a straight, flagless ste ...

(or crotchet) B of the third beat of the second bar which harmonizes the opening G of the answer. The later codettas may be considerably longer, and often serve to (a) develop the material heard so far in the subject/answer and countersubject and possibly introduce ideas heard in the second countersubject or free counterpoint that follows (b) delay, and therefore heighten the impact of the reentry of the subject in another voice as well as modulating back to the tonic.

The exposition usually concludes when all voices have given a statement of the subject or answer. In some fugues, the exposition will end with a redundant entry, or an extra presentation of the theme. Furthermore, in some fugues the entry of one of the voices may be reserved until later, for example in the pedals of an organ fugue (see J.S. Bach's Fugue in C major for Organ, BWV 547).

Episode

Further entries of the subject follow this initial exposition, either immediately (as for example in Fugue No. 1 in C major, BWV 846 of the ''Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time, ''clavier'', meaning keyboard, referred to a variety of in ...

'') or separated by episodes. Episodic material is always modulatory and is usually based upon some element heard in the exposition. Each episode has the primary function of transitioning for the next entry of the subject in a new key, and may also provide release from the strictness of form employed in the exposition, and middle-entries. André Gedalge

André Gedalge (27 December 1856 – 5 February 1926) was a French composer and teacher.

Biography

André Gedalge was born at 75 rue des Saints-Pères in Paris where he first worked as a bookseller and editor, specialising in ''livres de prix' ...

states that the episode of the fugue is generally based on a series of imitations of the subject that have been fragmented.

Development

Further entries of the subject, or middle entries, occur throughout the fugue. They must state the subject or answer at least once in its entirety, and may also be heard in combination with the countersubject(s) from the exposition, new countersubjects, free counterpoint, or any of these in combination. It is uncommon for the subject to enter alone in a single voice in the middle entries as in the exposition; rather, it is usually heard with at least one of the countersubjects and/or other free contrapuntal accompaniments. Middle entries tend to occur at pitches other than the initial. As shown in the typical structure above, these are oftenclosely related key

In music, a closely related key (or close key) is one sharing many common tones with an original key, as opposed to a distantly related key (or distant key). In music harmony, there are six of them: five share all, or all except one, pitches wit ...

s such as the relative dominant and subdominant

In music, the subdominant is the fourth tonal degree () of the diatonic scale. It is so called because it is the same distance ''below'' the tonic as the dominant is ''above'' the tonicin other words, the tonic is the dominant of the subdomina ...

, although the key structure of fugues varies greatly. In the fugues of J.S. Bach, the first middle entry occurs most often in the relative major

In music, relative keys are the major and minor scales that have the same key signatures (enharmonically equivalent), meaning that they share all the same notes but are arranged in a different order of whole steps and half steps. A pair of major an ...

or minor

Minor may refer to:

* Minor (law), a person under the age of certain legal activities.

** A person who has not reached the age of majority

* Academic minor, a secondary field of study in undergraduate education

Music theory

*Minor chord

** Barb ...

of the work's overall key, and is followed by an entry in the dominant of the relative major or minor when the fugue's subject requires a tonal answer. In the fugues of earlier composers (notably, Buxtehude

Buxtehude (), officially the Hanseatic City of Buxtehude (german: Hansestadt Buxtehude, nds, Hansestadt Buxthu ()), is a town on the Este River in Northern Germany, belonging to the district of Stade in Lower Saxony. It is part of the Hamburg ...

and Pachelbel

Johann Pachelbel (baptised – buried 9 March 1706; also Bachelbel) was a German composer, organist, and teacher who brought the south German organ schools to their peak. He composed a large body of sacred and secular music, and his contribut ...

), middle entries in keys other than the tonic and dominant tend to be the exception, and non-modulation the norm. One of the famous examples of such non-modulating fugue occurs in Buxtehude's Praeludium (Fugue and Chaconne) in C, BuxWV 137.

When there is no entrance of the subject and answer material, the composer can develop the subject by altering the subject. This is called an ''episode'', often by ''inversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

'', although the term is sometimes used synonymously with middle entry and may also describe the exposition of completely new subjects, as in a double fugue for example (see below). In any of the entries within a fugue, the subject may be altered, by inversion, retrograde (a less common form where the entire subject is heard back-to-front) and diminution

In Western music and music theory, diminution (from Medieval Latin ''diminutio'', alteration of Latin ''deminutio'', decrease) has four distinct meanings. Diminution may be a form of embellishment in which a long note is divided into a series of ...

(the reduction of the subject's rhythmic values by a certain factor), augmentation (the increase of the subject's rhythmic values by a certain factor) or any combination of them.

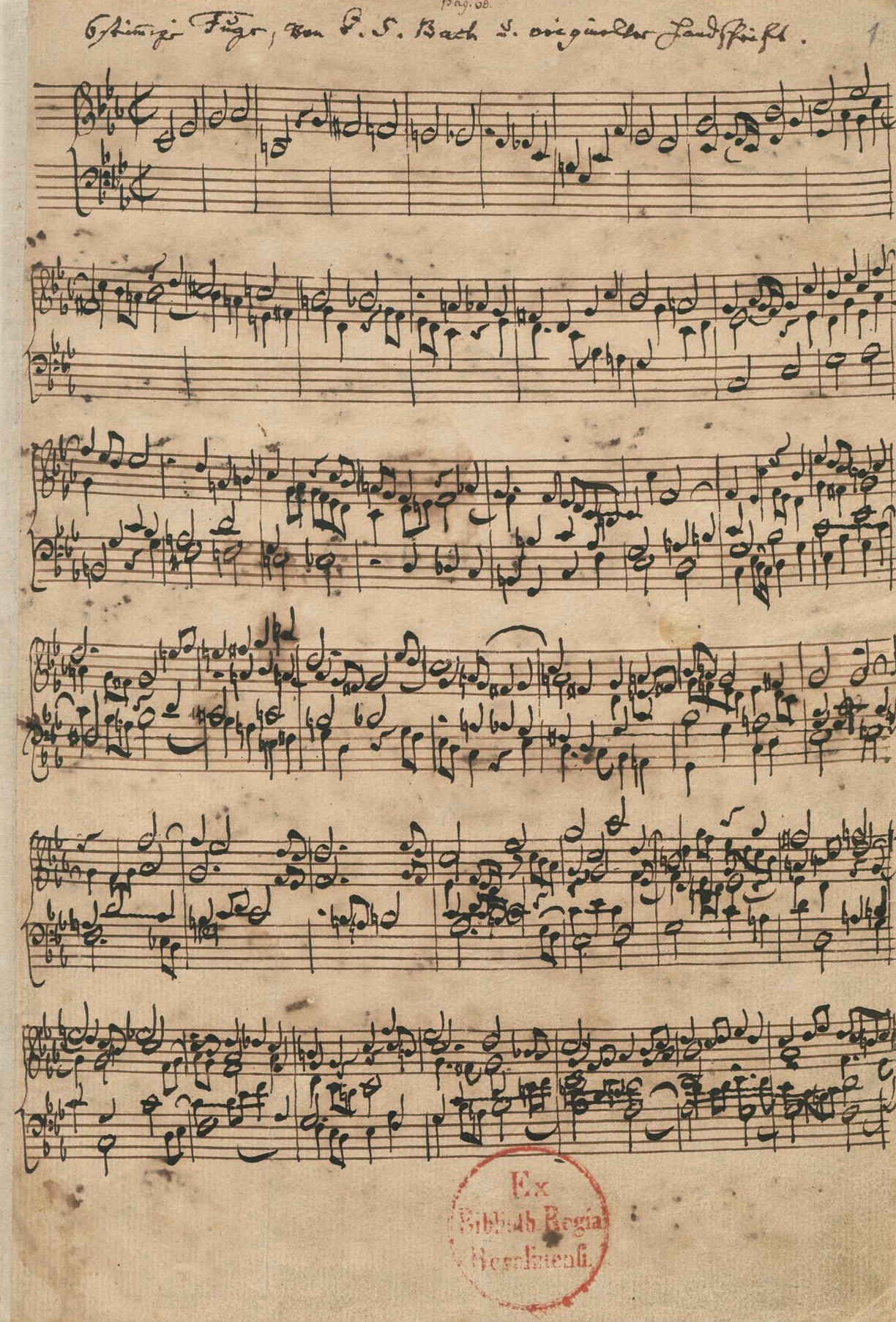

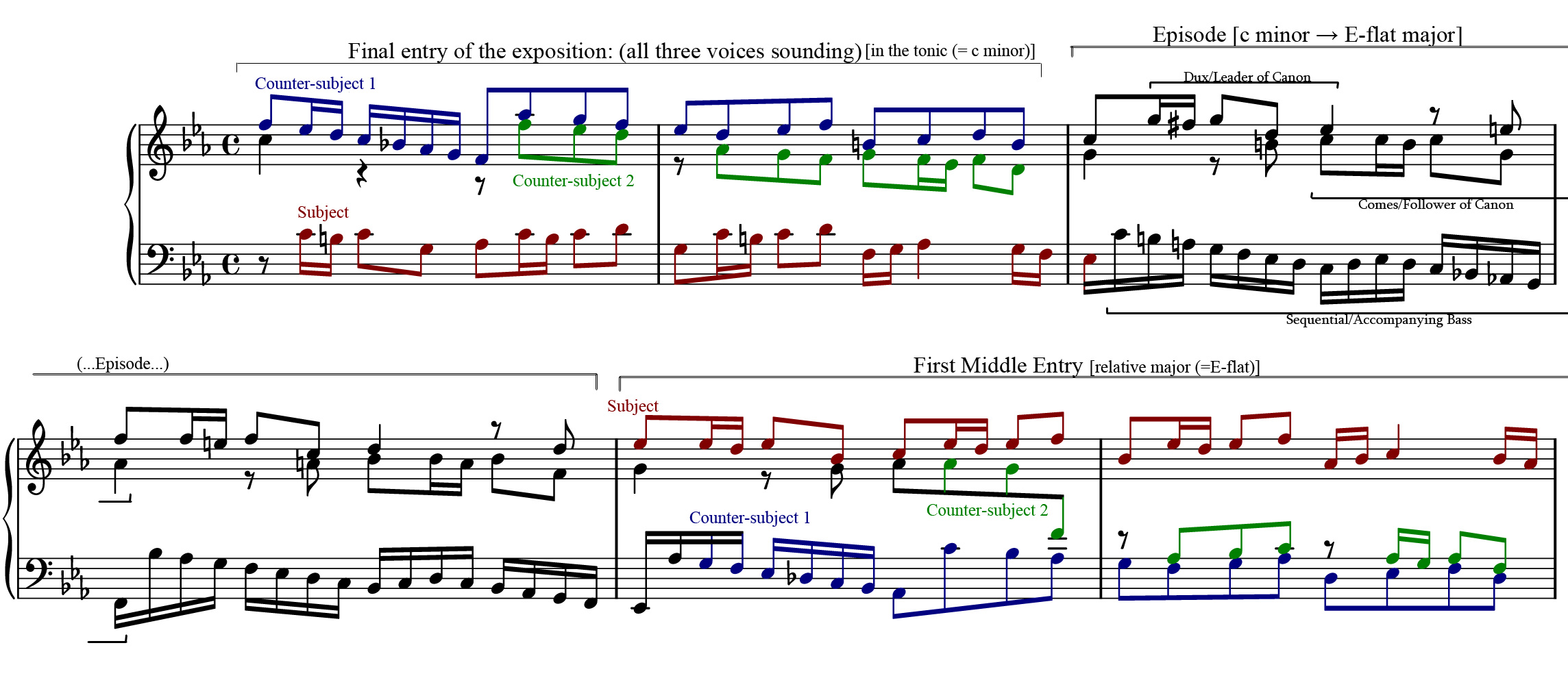

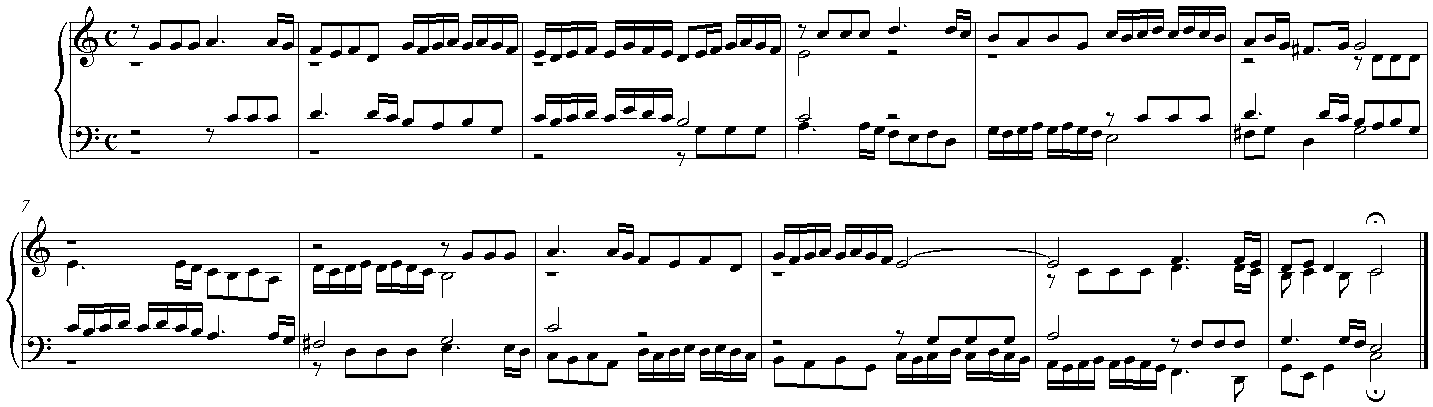

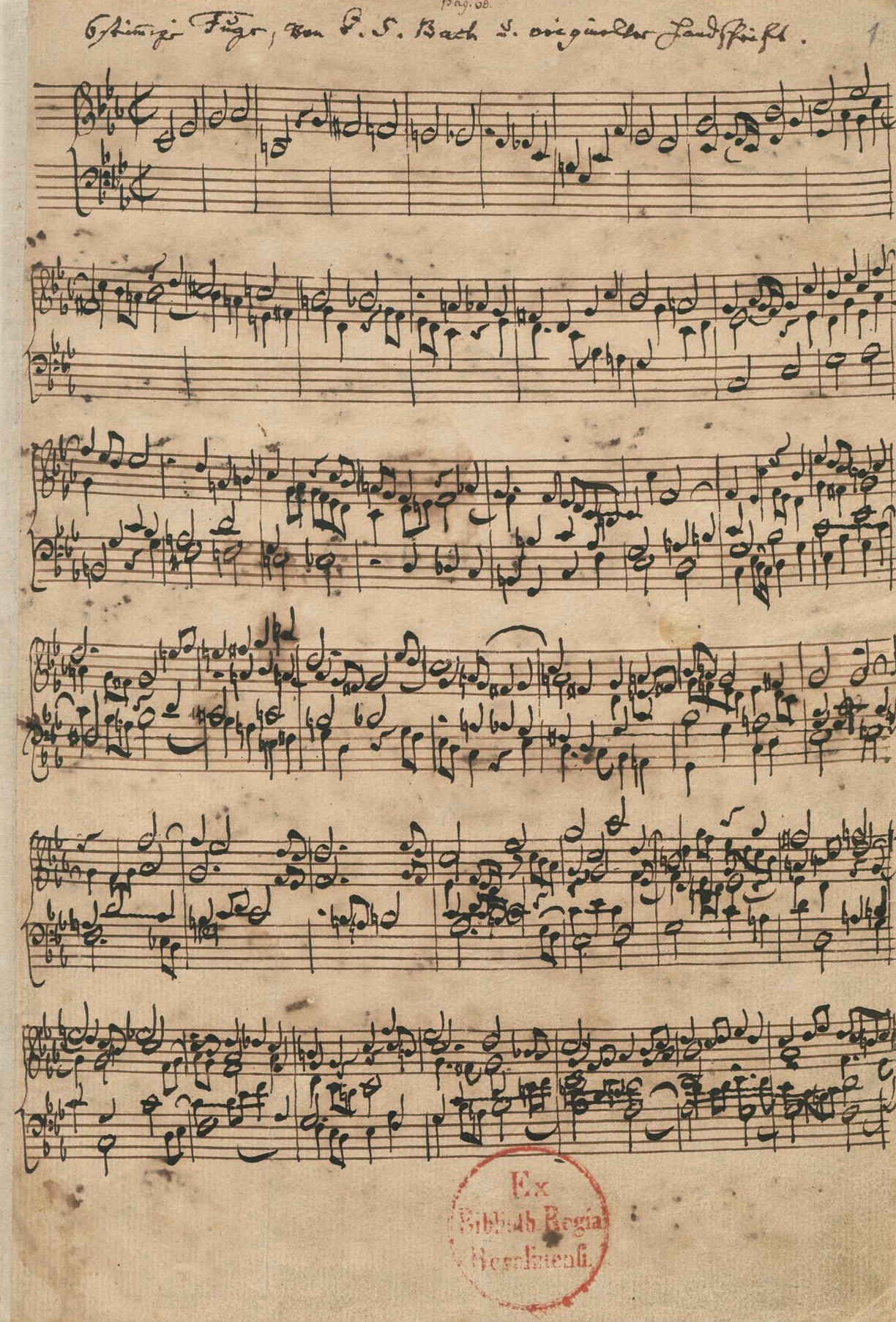

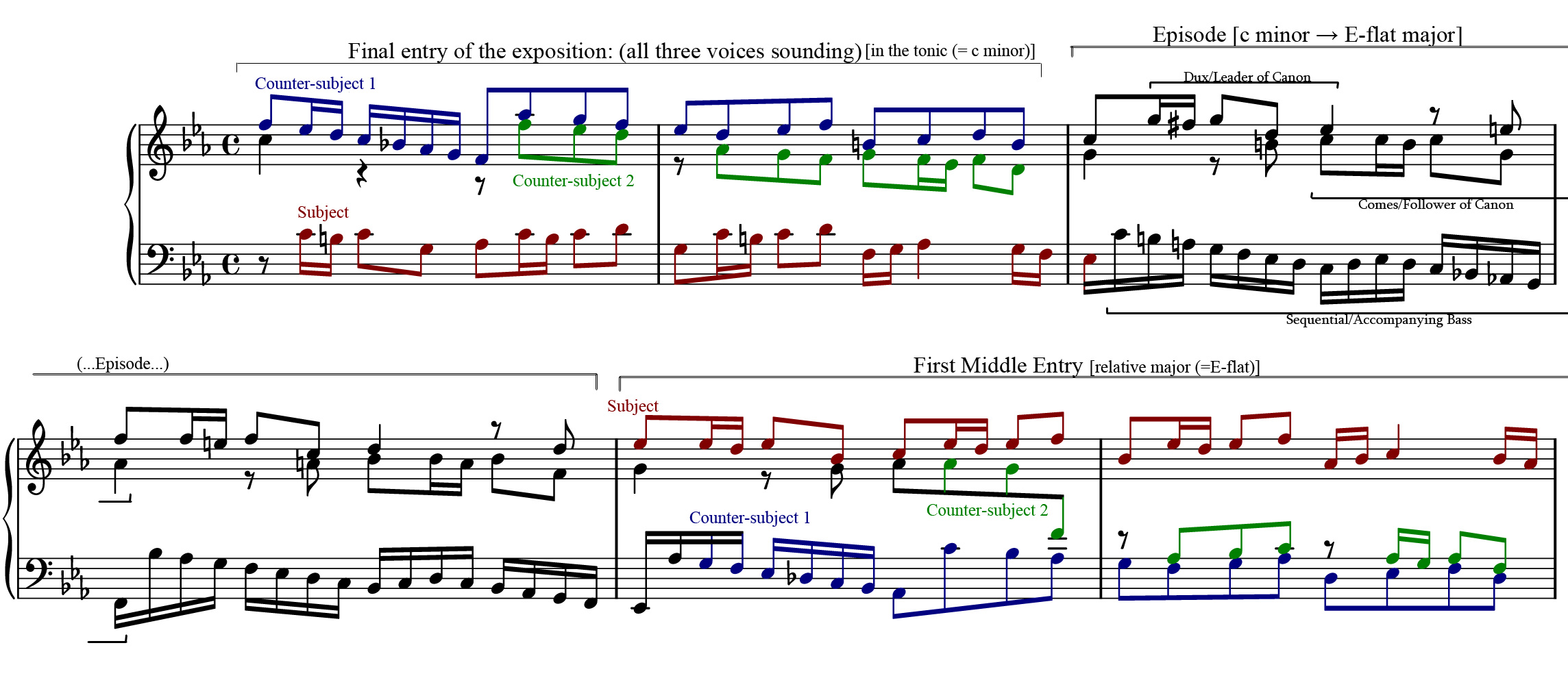

Example and analysis

The excerpt below, bars 7–12 of J.S. Bach's Fugue No. 2 in C minor, BWV 847, from the ''Well-Tempered Clavier'', Book 1 illustrates the application of most of the characteristics described above. The fugue is for keyboard and in three voices, with regular countersubjects. This excerpt opens at last entry of the exposition: the subject is sounding in the bass, the first countersubject in the treble, while the middle-voice is stating a second version of the second countersubject, which concludes with the characteristic rhythm of the subject, and is always used together with the first version of the second countersubject. Following this an episode modulates from the tonic to the relative major by means ofsequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members (also called ''elements'', or ''terms''). The number of elements (possibly infinite) is calle ...

, in the form of an accompanied canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western can ...

at the fourth. Arrival in E major is marked by a quasi perfect cadence

In Western musical theory, a cadence (Latin ''cadentia'', "a falling") is the end of a phrase in which the melody or harmony creates a sense of full or partial resolution, especially in music of the 16th century onwards.Don Michael Randel (1999) ...

across the bar line, from the last quarter note beat of the first bar to the first beat of the second bar in the second system, and the first middle entry. Here, Bach has altered the second countersubject to accommodate the change of mode

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

.

False entries

At any point in the fugue there may be "false entries" of the subject, which include the start of the subject but are not completed. False entries are often abbreviated to the head of the subject, and anticipate the "true" entry of the subject, heightening the impact of the subject proper.

Counter-exposition

The counter-exposition is a second exposition. However, there are only two entries, and the entries occur in reverse order. The counter-exposition in a fugue is separated from the exposition by an episode and is in the same key as the original exposition.Stretto

Sometimes counter-expositions or the middle entries take place in ''stretto

In music, the Italian term ''stretto'' (plural: ''stretti'') has two distinct meanings:

# In a fugue, ''stretto'' (german: Engführung) is the imitation of the subject in close succession, so that the answer enters before the subject is complete ...

,'' whereby one voice responds with the subject/answer before the first voice has completed its entry of the subject/answer, usually increasing the intensity of the music.

Only one entry of the subject must be heard in its completion in a ''stretto''. However, a ''stretto'' in which the subject/answer is heard in completion in all voices is known as ''stretto maestrale'' or ''grand stretto''. ''Strettos'' may also occur by inversion, augmentation and diminution. A fugue in which the opening exposition takes place in ''stretto'' form is known as a ''close fugue'' or ''stretto fugue'' (see for example, the ''Gratias agimus tibi'' and ' choruses from J.S. Bach's

Only one entry of the subject must be heard in its completion in a ''stretto''. However, a ''stretto'' in which the subject/answer is heard in completion in all voices is known as ''stretto maestrale'' or ''grand stretto''. ''Strettos'' may also occur by inversion, augmentation and diminution. A fugue in which the opening exposition takes place in ''stretto'' form is known as a ''close fugue'' or ''stretto fugue'' (see for example, the ''Gratias agimus tibi'' and ' choruses from J.S. Bach's Mass in B Minor

The Mass in B minor (), BWV 232, is an extended setting of the Mass ordinary by Johann Sebastian Bach. The composition was completed in 1749, the year before the composer's death, and was to a large extent based on earlier work, such as a Sanctu ...

).

Final entries and coda

The closing section of a fugue often includes one or two counter-expositions, and possibly a stretto, in the tonic; sometimes over a tonic or dominantpedal note

In music, a pedal point (also pedal note, organ point, pedal tone, or pedal) is a sustained tone, typically in the bass, during which at least one foreign (i.e. dissonant) harmony is sounded in the other parts. A pedal point sometimes function ...

. Any material that follows the final entry of the subject is considered to be the final coda

Coda or CODA may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* Movie coda, a post-credits scene

* ''Coda'' (1987 film), an Australian horror film about a serial killer, made for television

*''Coda'', a 2017 American experimental film from Na ...

and is normally cadential.

Types

Simple fugue

A simple fugue has only one subject, and does not utilizeinvertible counterpoint

In music theory, an inversion is a type of change to intervals, chords, voices (in counterpoint), and melodies. In each of these cases, "inversion" has a distinct but related meaning. The concept of inversion also plays an important role in mu ...

.

Double (triple, quadruple) fugue

A double fugue has two subjects that are often developed simultaneously. Similarly, a triple fugue has three subjects. There are two kinds of double (triple) fugue: (a) a fugue in which the second (third) subject is (are) presented simultaneously with the subject in the exposition (e.g. as inKyrie Eleison

Kyrie, a transliteration of Greek , vocative case of (''Kyrios''), is a common name of an important prayer of Christian liturgy, also called the Kyrie eleison ( ; ).

In the Bible

The prayer, "Kyrie, eleison," "Lord, have mercy" derives fro ...

of Mozart's Requiem in D minor or the fugue of Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582

''Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor'' (BWV 582) is an organ piece by Johann Sebastian Bach. Presumably composed early in Bach's career, it is one of his most important and well-known works, and an important influence on 19th and 20th century pas ...

), and (b) a fugue in which all subjects have their own expositions at some point, and they are not combined until later (see for example, the three-subject Fugue No. 14 in F minor from Bach's ''Well-Tempered Clavier'' Book 2, or more famously, Bach's "St. Anne" Fugue in E major, BWV 552

The (BWV; ; ) is a catalogue of compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach. It was first published in 1950, edited by Wolfgang Schmieder. The catalogue's second edition appeared in 1990. An abbreviated version of that second edition, known as BWV2a ...

, a triple fugue for organ.)

Counter-fugue

A counter-fugue is a fugue in which the first answer is presented as the subject ininversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

(upside down), and the inverted subject continues to feature prominently throughout the fugue. Examples include ''Contrapunctus V'' through ''Contrapunctus VII'', from Bach's ''The Art of Fugue

''The Art of Fugue'', or ''The Art of the Fugue'' (german: Die Kunst der Fuge, links=no), BWV 1080, is an incomplete musical work of unspecified instrumentation by Johann Sebastian Bach. Written in the last decade of his life, ''The Art of Fug ...

''.

Permutation fugue

Permutation fugue describes a type of composition (or technique of composition) in which elements of fugue and strictcanon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western can ...

are combined. Each voice enters in succession with the subject, each entry alternating between tonic and dominant, and each voice, having stated the initial subject, continues by stating two or more themes (or countersubjects), which must be conceived in correct invertible counterpoint

In music theory, an inversion is a type of change to intervals, chords, voices (in counterpoint), and melodies. In each of these cases, "inversion" has a distinct but related meaning. The concept of inversion also plays an important role in mu ...

. (In other words, the subject and countersubjects must be capable of being played both above and below all the other themes without creating any unacceptable dissonances.) Each voice takes this pattern and states all the subjects/themes in the same order (and repeats the material when all the themes have been stated, sometimes after a rest).

There is usually very little non-structural/thematic material. During the course of a permutation fugue, it is quite uncommon, actually, for every single possible voice-combination (or "permutation") of the themes to be heard. This limitation exists in consequence of sheer proportionality: the more voices in a fugue, the greater the number of possible permutations. In consequence, composers exercise editorial judgment as to the most musical of permutations and processes leading thereto. One example of permutation fugue can be seen in the eighth and final chorus of J.S. Bach's cantata, ''Himmelskönig, sei willkommen'', BWV 182.

Permutation fugues differ from conventional fugue in that there are no connecting episodes, nor statement of the themes in related keys. So for example, the fugue of Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582

''Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor'' (BWV 582) is an organ piece by Johann Sebastian Bach. Presumably composed early in Bach's career, it is one of his most important and well-known works, and an important influence on 19th and 20th century pass ...

is not purely a permutation fugue, as it does have episodes between permutation expositions. Invertible counterpoint is essential to permutation fugues but is not found in simple fugues.

Fughetta

A fughetta is a short fugue that has the same characteristics as a fugue. Often the contrapuntal writing is not strict, and the setting less formal. See for example, variation 24 ofBeethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

's ''Diabelli Variations'' Op. 120.

History

Middle Ages and Renaissance

The term ''fuga'' was used as far back as theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, but was initially used to refer to any kind of imitative counterpoint, including canons, which are now thought of as distinct from fugues. Prior to the 16th century, fugue was originally a genre. It was not until the 16th century that fugal technique as it is understood today began to be seen in pieces, both instrumental and vocal. Fugal writing is found in works such as fantasias, ricercar

A ricercar ( , ) or ricercare ( , ) is a type of late Renaissance and mostly early Baroque instrumental composition. The term ''ricercar'' derives from the Italian verb which means 'to search out; to seek'; many ricercars serve a preludial functi ...

es and canzona

The canzona is an Italian musical form derived from the Franco-Flemish and Parisian chansons, and during Giovanni Gabrieli's lifetime was frequently spelled canzona, though both earlier and later the singular was spelled either canzon or canzone ...

s.

"Fugue" as a theoretical term first occurred in 1330 when Jacobus of Liege wrote about the ''fuga'' in his ''Speculum musicae''. The fugue arose from the technique of "imitation", where the same musical material was repeated starting on a different note.

Gioseffo Zarlino

Gioseffo Zarlino (31 January or 22 March 1517 – 4 February 1590) was an Italian music theorist and composer of the Renaissance. He made a large contribution to the theory of counterpoint as well as to musical tuning.

Life and career

Zarlino w ...

, a composer, author, and theorist in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, was one of the first to distinguish between the two types of imitative counterpoint: fugues and canons (which he called imitations). Originally, this was to aid improvisation

Improvisation is the activity of making or doing something not planned beforehand, using whatever can be found. Improvisation in the performing arts is a very spontaneous performance without specific or scripted preparation. The skills of impr ...

, but by the 1550s, it was considered a technique of composition. The composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina ( – 2 February 1594) was an Italian composer of late Renaissance music. The central representative of the Roman School, with Orlande de Lassus and Tomás Luis de Victoria, Palestrina is considered the leading ...

(1525?–1594) wrote masses using modal counterpoint and imitation, and fugal writing became the basis for writing motet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to Margar ...

s as well. Palestrina's imitative motets differed from fugues in that each phrase of the text had a different subject which was introduced and worked out separately, whereas a fugue continued working with the same subject or subjects throughout the entire length of the piece.

Baroque era

It was in theBaroque period

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including t ...

that the writing of fugues became central to composition, in part as a demonstration of compositional expertise. Fugues were incorporated into a variety of musical forms. Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck ( ; April or May, 1562 – 16 October 1621) was a Dutch composer, organist, and pedagogue whose work straddled the end of the Renaissance and beginning of the Baroque eras. He was among the first major keyboard compo ...

, Girolamo Frescobaldi

Girolamo Alessandro Frescobaldi (; also Gerolamo, Girolimo, and Geronimo Alissandro; September 15831 March 1643) was an Italian composer and virtuoso keyboard player. Born in the Duchy of Ferrara, he was one of the most important composers of k ...

, Johann Jakob Froberger

Johann Jakob Froberger ( baptized 19 May 1616 – 7 May 1667) was a German Baroque composer, keyboard virtuoso, and organist. Among the most famous composers of the era, he was influential in developing the musical form of the suite of dances in h ...

and Dieterich Buxtehude

Dieterich Buxtehude (; ; born Diderik Hansen Buxtehude; c. 1637 – 9 May 1707) was a Danish organist and composer of the Baroque period, whose works are typical of the North German organ school. As a composer who worked in various vocal ...

all wrote fugues, and George Frideric Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque music, Baroque composer well known for his opera#Baroque era, operas, oratorios, anthems, concerto grosso, concerti grossi, ...

included them in many of his oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

s. Keyboard suites from this time often conclude with a fugal gigue

The gigue (; ) or giga () is a lively baroque dance originating from the English jig. It was imported into France in the mid-17th centuryBellingham, Jane"gigue."''The Oxford Companion to Music''. Ed. Alison Latham. Oxford Music Online. 6 July 200 ...

. Domenico Scarlatti

Giuseppe Domenico Scarlatti, also known as Domingo or Doménico Scarlatti (26 October 1685-23 July 1757), was an Italian composer. He is classified primarily as a Baroque composer chronologically, although his music was influential in the deve ...

has only a few fugues among his corpus of over 500 harpsichord sonatas. The French overture

The French overture is a musical form widely used in the Baroque period. Its basic formal division is into two parts, which are usually enclosed by double bars and repeat signs. They are complementary in style (slow in dotted rhythms and fast in f ...

featured a quick fugal section after a slow introduction. The second movement of a sonata da chiesa

Sonata da chiesa (Italian: "church sonata") is a 17th-century genre of musical composition for one or more melody instruments and is regarded an antecedent of later forms of 18th century instrumental music. It generally comprises four movements, t ...

, as written by Arcangelo Corelli

Arcangelo Corelli (, also , , ; 17 February 1653 – 8 January 1713) was an Italian composer and violinist of the Baroque era. His music was key in the development of the modern genres of sonata and concerto, in establishing the preeminence of ...

and others, was usually fugal.

The Baroque period also saw a rise in the importance of music theory

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the "rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (ke ...

. Some fugues during the Baroque period were pieces designed to teach contrapuntal technique to students. The most influential text was Johann Joseph Fux's ''Gradus Ad Parnassum

The Latin phrase ''gradus ad Parnassum'' means "steps to Parnassus". It is sometimes shortened to ''gradus''. The name ''Parnassus'' was used to denote the loftiest part of a mountain range in central Greece, a few kilometres north of Delphi, of wh ...

'' ("Steps to Parnassus

Mount Parnassus (; el, Παρνασσός, ''Parnassós'') is a mountain range of central Greece that is and historically has been especially valuable to the Greek nation and the earlier Greek city-states for many reasons. In peace, it offers ...

"), which appeared in 1725. This work laid out the terms of "species" of counterpoint, and offered a series of exercises to learn fugue writing. Fux's work was largely based on the practice of Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; grc, Πραίνεστος, ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Pren ...

's modal fugues. Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

studied from this book, and it remained influential into the nineteenth century. Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

, for example, taught counterpoint from his own summary of Fux and thought of it as the basis for formal structure.

Bach's most famous fugues are those for the harpsichord in ''The Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time, ''clavier'', meaning keyboard, referred to a variety of in ...

'', which many composers and theorists look at as the greatest model of fugue. ''The Well-Tempered Clavier'' comprises two volumes written in different times of Bach's life, each comprising 24 prelude and fugue pairs, one for each major and minor key. Bach is also known for his organ fugues, which are usually preceded by a prelude

Prelude may refer to:

Music

*Prelude (music), a musical form

*Prelude (band), an English-based folk band

*Prelude Records (record label), a former New York-based dance independent record label

*Chorale prelude, a short liturgical composition for ...

or toccata

Toccata (from Italian ''toccare'', literally, "to touch", with "toccata" being the action of touching) is a virtuoso piece of music typically for a keyboard or plucked string instrument featuring fast-moving, lightly fingered or otherwise virtuo ...

. ''The Art of Fugue'', BWV 1080, is a collection of fugues (and four canons) on a single theme that is gradually transformed as the cycle progresses. Bach also wrote smaller single fugues and put fugal sections or movements into many of his more general works. J.S. Bach's influence extended forward through his son C.P.E. Bach and through the theorist Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg

Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (21 November 1718 – 22 May 1795) was a German music critic, music theorist and composer. He was friendly and active with many figures of the Enlightenment of the 18th century.

Life

Little is known of Marpurg's earl ...

(1718–1795) whose ''Abhandlung von der Fuge'' ("Treatise on the fugue", 1753) was largely based on J.S. Bach's work.

Classical era

During theClassical era

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, the fugue was no longer a central or even fully natural mode of musical composition. Nevertheless, both Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

and Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period (music), Classical period. Despite his short life, his ra ...

had periods of their careers in which they in some sense "rediscovered" fugal writing and used it frequently in their work.

Haydn

Joseph Haydn was the leader of fugal composition and technique in the Classical era. Haydn's most famous fugues can be found in his "Sun" Quartets (op. 20, 1772), of which three have fugal finales. This was a practice that Haydn repeated only once later in his quartet-writing career, with the finale of his String Quartet, Op. 50 No. 4 (1787). Some of the earliest examples of Haydn's use of counterpoint, however, are in three symphonies (No. 3

''No. 3'' () is a 1997 Koreans, South Korean Kkangpae, gangster comedy film starring Han Suk-kyu as the titular no. 3 man of a gang who's aspiring to rise up the ranks and become the leader of his own gang. It was writer-director Song Nung-han's ...

, No. 13, and No. 40) that date from 1762 to 1763. The earliest fugues, in both the symphonies and in the Baryton trios, exhibit the influence of Joseph Fux's treatise on counterpoint, ''Gradus ad Parnassum'' (1725), which Haydn studied carefully.

Haydn's second fugal period occurred after he heard, and was greatly inspired by, the oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

s of Handel during his visits to London (1791–1793, 1794–1795). Haydn then studied Handel's techniques and incorporated Handelian fugal writing into the choruses of his mature oratorios '' The Creation'' and '' The Seasons,'' as well as several of his later symphonies, including No. 88, No. 95, and No. 101; and the late string quartets, Opus 71 no. 3 and (especially) Opus 76 no. 6.

Mozart

The young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart studied counterpoint withPadre Martini

Giovanni Battista or Giambattista Martini, Conventual Franciscans, O.F.M. Conv. (24 April 1706 – 3 August 1784), also known as Padre Martini, was an Italians, Italian Conventual Franciscan friar, who was a leading musician, composer, ...

in Bologna. Under the employment of Archbishop Colloredo, and the musical influence of his predecessors and colleagues such as Johann Ernst Eberlin

Johann Ernst Eberlin (27 March 1702 – 19 June 1762) was a German composer and organist whose works bridge the baroque and classical eras. He was a prolific composer, chiefly of church organ and choral music. Marpurg claims he wrote as much a ...

, Anton Cajetan Adlgasser

Anton Cajetan Adlgasser (sometimes Anton Cajetan Adelgasser; 1 October 1729 – 23 December 1777) was a German organist and composer at Salzburg Cathedral and at court, and composed a good deal of liturgical music (including eight masses and two re ...

, Michael Haydn

Johann Michael Haydn (; 14 September 173710 August 1806) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period, the younger brother of Joseph Haydn.

Life

Michael Haydn was born in 1737 in the Austrian village of Rohrau, near the Hungarian border. ...

, and his own father, Leopold Mozart

Johann Georg Leopold Mozart (November 14, 1719 – May 28, 1787) was a German composer, violinist and theorist. He is best known today as the father and teacher of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and for his violin textbook ''Versuch einer gründlichen ...

at the Salzburg Cathedral, the young Mozart composed ambitious fugues and contrapuntal passages in Catholic choral works such as Mass in C minor, K. 139 "Waisenhaus" (1768), Mass in C major, K. 66 "Dominicus" (1769), Mass in C major, K. 167 "in honorem Sanctissimae Trinitatis" (1773), Mass in C major, K. 262 "Missa longa" (1775), Mass in C major, K. 337 "Solemnis" (1780), various litanies, and vespers. Leopold admonished his son openly in 1777 that he not forget to make public demonstration of his abilities in "fugue, canon, and contrapunctus". Later in life, the major impetus to fugal writing for Mozart was the influence of Baron Gottfried van Swieten

Gottfried Freiherr van Swieten (29 October 1733 – 29 March 1803) was a Dutch-born Austrian diplomat, librarian, and government official who served the Holy Roman Empire during the 18th century. He was an enthusiastic amateur musician and is bes ...

in Vienna around 1782. Van Swieten, during diplomatic service in Berlin, had taken the opportunity to collect as many manuscripts by Bach and Handel as he could, and he invited Mozart to study his collection and encouraged him to transcribe various works for other combinations of instruments. Mozart was evidently fascinated by these works and wrote a set of five transcriptions for string quartet, K. 405 (1782), of fugues from Bach's ''Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time, ''clavier'', meaning keyboard, referred to a variety of in ...

'', introducing them with preludes of his own. In a letter to his sister Nannerl Mozart

Maria Anna Walburga Ignatia Mozart (30 July 1751 – 29 October 1829), called "Marianne" and nicknamed Nannerl, was a musician, the older sister of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) and daughter of Leopold Mozart, Leopold (1719–1787) and ...

, dated in Vienna on 20 April 1782, Mozart recognizes that he had not written anything in this form, but moved by his wife's interest he composed one piece, which is sent with the letter. He begs her not to let anybody see the fugue and manifests the hope to write five more and then present them to Baron van Swieten. Regarding the piece, he said "I have taken particular care to write ''andante maestoso'' upon it, so that it should not be played fast – for if a fugue is not played slowly the ear cannot clearly distinguish the new subject as it is introduced and the effect is missed". Mozart then set to writing fugues on his own, mimicking the Baroque style. These included a fugue in C minor, K. 426, for two pianos (1783). Later, Mozart incorporated fugal writing into his opera ''Die Zauberflöte

''The Magic Flute'' (German: , ), K. 620, is an opera in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to a German libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder. The work is in the form of a ''Singspiel'', a popular form during the time it was written that includ ...

'' and the finale of his Symphony No. 41.

The parts of the

The parts of the Requiem

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

he completed also contain several fugues (most notably the Kyrie, and the three fugues in the Domine Jesu; he also left behind a sketch for an Amen

Amen ( he, אָמֵן, ; grc, ἀμήν, ; syc, ܐܡܝܢ, ; ar, آمين, ) is an Abrahamic declaration of affirmation which is first found in the Hebrew Bible, and subsequently found in the New Testament. It is used in Jews, Jewish, Christia ...

fugue which, some believe, would have come at the end of the Sequentia).

Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

was familiar with fugal writing from childhood, as an important part of his training was playing from ''The Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time, ''clavier'', meaning keyboard, referred to a variety of in ...

''. During his early career in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, Beethoven attracted notice for his performance of these fugues. There are fugal sections in Beethoven's early piano sonatas, and fugal writing is to be found in the second and fourth movements of the ''Eroica Symphony

The Symphony No. 3 in E major, Op. 55, (also Italian ''Sinfonia Eroica'', ''Heroic Symphony''; german: Eroica, ) is a symphony in four movements by Ludwig van Beethoven.

One of Beethoven's most celebrated works, the ''Eroica'' symphony is a l ...

'' (1805). Beethoven incorporated fugues in his sonatas, and reshaped the episode's purpose and compositional technique for later generations of composers.

Nevertheless, fugues did not take on a truly central role in Beethoven's work until his late period. The finale of Beethoven's ''Hammerklavier'' Sonata contains a fugue, which was practically unperformed until the late 19th century, due to its tremendous technical difficulty and length. The last movement of his Cello Sonata, Op. 102 No. 2 is a fugue, and there are fugal passages in the last movements of his Piano Sonatas in A major, Op. 101 and A major Op. 110. According to Charles Rosen

Charles Welles Rosen (May 5, 1927December 9, 2012) was an American pianist and writer on music. He is remembered for his career as a concert pianist, for his recordings, and for his many writings, notable among them the book ''The Classical Sty ...

, "With the finale of 110, Beethoven re-conceived the significance of the most traditional elements of fugue writing."

Fugal passages are also found in the ''Missa Solemnis

{{Audio, De-Missa solemnis.ogg, Missa solemnis is Latin for Solemn Mass, and is a genre of musical settings of the Mass Ordinary, which are festively scored and render the Latin text extensively, opposed to the more modest Missa brevis. In French ...

'' and all movements of the Ninth Symphony, except the third. A massive, dissonant fugue forms the finale of his String Quartet, Op. 130 (1825); the latter was later published separately as Op. 133, the ''Große Fuge

The ''Grosse Fuge'' (German spelling: ''Große'' ''Fuge'', also known in English as the ''Great Fugue'' or ''Grand Fugue''), Op. 133, is a single-movement composition for string quartet by Ludwig van Beethoven. An immense double fugue, it was ...

'' ("Great Fugue"). However, it is the fugue that opens Beethoven's String Quartet in C minor, Op. 131 that several commentators regard as one of the composer's greatest achievements. Joseph Kerman

Joseph Wilfred Kerman (3 April 1924 – 17 March 2014) was an American musicologist and music critic. Among the leading musicologists of his generation, his 1985 book ''Contemplating Music: Challenges to Musicology'' (published in the UK as ''Mus ...

(1966, p. 330) calls it "this most moving of all fugues". J. W. N. Sullivan

John William Navin Sullivan (1886–1937) was a popular science writer and literary journalist, and the author of a study of Beethoven. He wrote some of the earliest non-technical accounts of Albert Einstein's general relativity, General Theory ...

(1927, p. 235) hears it as "the most superhuman piece of music that Beethoven has ever written." Philip Radcliffe

Philip Radcliffe (27 April 1905 – 2 September 1986) was an English academic, musicologist and composer, born in Godalming, Surrey.

Early life

He was educated at Charterhouse and read Classics at King's College, Cambridge, gaining a scholarship ...

(1965, p. 149) says " bare description of its formal outline can give but little idea of the extraordinary profundity of this fugue ." ]

]

Romantic era

By the beginning of the Romantic music, Romantic era, fugue writing had become specifically attached to the norms and styles of the Baroque.Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sy ...

wrote many fugues inspired by his study of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard w ...

.

Johannes Brahms' ''Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel'', Op. 24, is a work for solo piano written in 1861. It consists of a set of twenty-five variations and a concluding fugue, all based on a theme from George Frideric Handel's ''Harpsichord Suite No. 1 in B♭ major'', HWV 434.

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simpl ...

's Piano Sonata in B minor (1853) contains a powerful fugue, demanding incisive virtuosity from its player:

]

]

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

included several fugues in his opera ''Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

(; "The Master-Singers of Nuremberg"), WWV 96, is a music drama, or opera, in three acts, by Richard Wagner. It is the longest opera commonly performed, taking nearly four and a half hours, not counting two breaks between acts, and is traditio ...

''. Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the h ...

included a whimsical example at the end of his opera ''Falstaff

Sir John Falstaff is a fictional character who appears in three plays by William Shakespeare and is eulogised in a fourth. His significance as a fully developed character is primarily formed in the plays '' Henry IV, Part 1'' and '' Part 2'', w ...

'' and his setting of the Requiem Mass

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

contained two (originally three) choral fugues. Anton Bruckner

Josef Anton Bruckner (; 4 September 182411 October 1896) was an Austrian composer, organist, and music theorist best known for his symphonies, masses, Te Deum and motets. The first are considered emblematic of the final stage of Austro-Germ ...

and Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism ...

also included them in their respective symphonies. The exposition of the finale of Bruckner's Symphony No. 5 begins with a fugal exposition. The exposition ends with a chorale, the melody of which is then used as a second fugal exposition at the beginning of the development. The recapitulation features both fugal subjects concurrently. The finale of Mahler's Symphony No. 5 features a "fugue-like" passage early in the movement, though this is not actually an example of a fugue.

20th century

Twentieth-century composers brought fugue back to its position of prominence, realizing its uses in full instrumental works, its importance in development and introductory sections, and the developmental capabilities of fugal composition. The second movement ofMaurice Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

's piano suite ''Le Tombeau de Couperin

''Le Tombeau de Couperin'' (''The Couperin's Grave'') is a suite for solo piano by Maurice Ravel, composed between 1914 and 1917. The piece is in six movements, based on those of a traditional Baroque suite. Each movement is dedicated to the me ...

'' (1917) is a fugue that Roy Howat

Roy Howat (born 1951, Ayrshire, Scotland) is a Scottish pianist and musicologist, who specializes in French music. Howat has been Keyboard Research Fellow at the Royal Academy of Music in London since 2003, and Research Fellow at the Royal Cons ...

(200, p. 88) describes as having "a subtle glint of jazz". Béla Bartók

Béla Viktor János Bartók (; ; 25 March 1881 – 26 September 1945) was a Hungarian composer, pianist, and ethnomusicologist. He is considered one of the most important composers of the 20th century; he and Franz Liszt are regarded as H ...

's ''Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta

''Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta'', Sz. 106, BB 114 is one of the best-known compositions by the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. Commissioned by Paul Sacher to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the chamber orchestra '' Basler Kammero ...

'' (1936) opens with a slow fugue that Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

(1986, pp. 346–47) regards as "certainly the finest and most characteristic example of Bartók's subtle style... probably the most ''timeless'' of all Bartók's works – a fugue that unfolds like a fan to a point of maximum intensity and then closes, returning to the mysterious atmosphere of the opening." The second movement of Bartók‘s Sonata for Solo Violin is a fugue, and the first movement of his Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion

The Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, Sz. 110, BB 115, is a musical piece written by Hungarian composer Béla Bartók in 1937. The sonata was premiered by Bartók and his second wife, Ditta Pásztory-Bartók, with the percussionists Fritz Schi ...

contains a fugato.

''Schwanda the Bagpiper'' (Czech: Švanda dudák), written in 1926, an opera in two acts (five scenes), with music by Jaromír Weinberger, includes a ''Polka'' followed by a powerful ''Fugue'' based on the Polka theme.

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

also incorporated fugues into his works, including the Symphony of Psalms

The ''Symphony of Psalms'' is a choral symphony in three movements composed by Igor Stravinsky in 1930 during his neoclassical period. The work was commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orch ...

and the Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, formally the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, is a historic estate in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. It was the residence and garden of wealthy U.S. diplomat Robert Woods Bliss and his wife, M ...

concerto. Stravinsky recognized the compositional techniques of Bach, and in the second movement of his Symphony of Psalms (1930), he lays out a fugue that is much like that of the Baroque era. It employs a double fugue with two distinct subjects, the first beginning in C and the second in E. Techniques such as stretto, sequencing, and the use of subject incipits are frequently heard in the movement. Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his Symphony No. 1 (Shostakovich), First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throug ...

's 24 Preludes and Fugues

{{Unreferenced, date=June 2019, bot=noref (GreenC bot)

The prelude and fugue is a musical form generally consisting of two movements in the same key for solo keyboard. In classical music, the combination of prelude and fugue is one with a long hist ...

is the composer's homage to Bach's two volumes of The Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time, ''clavier'', meaning keyboard, referred to a variety of in ...

. In the first movement of his Fourth Symphony, starting at rehearsal mark 63, is a gigantic fugue in which the 20-bar subject (and tonal answer) consist entirely of semiquavers, played at the speed of quaver = 168.

Olivier Messiaen

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithologist who was one of the major composers of the 20th century. His music is rhythmically complex; harmonically ...

, writing about his '' Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus'' (1944) wrote of the sixth piece of that collection, "''Par Lui tout a été fait''" ("By Him were all things made"):

György Ligeti

György Sándor Ligeti (; ; 28 May 1923 – 12 June 2006) was a Hungarian-Austrian composer of contemporary classical music. He has been described as "one of the most important avant-garde composers in the latter half of the twentieth century" ...

wrote a five-part double fugue for his ''Requiems second movement, the Kyrie, in which each part (SMATB) is subdivided in four-voice "bundles" that make a canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western can ...

. The melodic material in this fugue is totally chromatic

Diatonic and chromatic are terms in music theory that are most often used to characterize scales, and are also applied to musical instruments, intervals, chords, notes, musical styles, and kinds of harmony. They are very often used as a pair, ...

, with melismatic

Melisma ( grc-gre, μέλισμα, , ; from grc, , melos, song, melody, label=none, plural: ''melismata'') is the singing of a single syllable of text while moving between several different notes in succession. Music sung in this style is referr ...

(running) parts overlaid onto skipping intervals, and use of polyrhythm

Polyrhythm is the simultaneous use of two or more rhythms that are not readily perceived as deriving from one another, or as simple manifestations of the same meter. The rhythmic layers may be the basis of an entire piece of music (cross-rhyth ...

(multiple simultaneous subdivisions of the measure), blurring everything both harmonically and rhythmically so as to create an aural aggregate, thus highlighting the theoretical/aesthetic question of the next section as to whether fugue is a form or a texture. According to Tom Service

Tom Service (born 8 March 1976) is a British writer, music journalist and television and radio presenter, who has written regularly for ''The Guardian'' since 1999 and presented on BBC Radio 3 since 2001. He is a regular presenter of The Proms f ...

, in this work, Ligeti

Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

used a fugue in the final part of ''The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra

''The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra'', Op. 34, is a 1945 musical composition by Benjamin Britten with a subtitle ''Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell''. It was based on the second movement, "Rondeau", of the ''Abdelazer'' suit ...

'' (1946). The Henry Purcell

Henry Purcell (, rare: September 1659 – 21 November 1695) was an English composer.

Purcell's style of Baroque music was uniquely English, although it incorporated Italian and French elements. Generally considered among the greatest E ...

theme is triumphantly cited at the end, making it a choral fugue.

Canadian pianist and musical thinker Glenn Gould

Glenn Herbert Gould (; né Gold; September 25, 1932October 4, 1982) was a Canadian classical pianist. He was one of the most famous and celebrated pianists of the 20th century, and was renowned as an interpreter of the keyboard works of Johann ...

composed '' So You Want to Write a Fugue?'', a full-scale fugue set to a text that cleverly explicates its own musical form.

Outside classical music

Fugues (or fughettas/fugatos) have been incorporated into genres outside Western classical music. Several examples exist withinjazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

, such as ''Bach goes to Town'', composed by the Welsh composer Alec Templeton

Alec Andrew Templeton (4 July 1909/1028 March 1963) was a Welsh composer, pianist, and satirist.

Templeton was born in Cardiff, Wales. There is some confusion concerning Alec Templeton's year of birth. Most published and Internet biographies g ...

and recorded by Benny Goodman

Benjamin David Goodman (May 30, 1909 – June 13, 1986) was an American clarinetist and bandleader known as the "King of Swing".

From 1936 until the mid-1940s, Goodman led one of the most popular swing big bands in the United States. His co ...

in 1938, and ''Concorde

The Aérospatiale/BAC Concorde () is a retired Franco-British supersonic airliner jointly developed and manufactured by Sud Aviation (later Aérospatiale) and the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC).

Studies started in 1954, and France an ...

'' composed by John Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American politician and civil rights activist who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashville ...

and recorded by the Modern Jazz Quartet

The Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ) was a jazz combo established in 1952 that played music influenced by classical music, classical, cool jazz, blues and bebop. For most of its history the Quartet consisted of John Lewis (pianist), John Lewis (piano), ...

in 1955.

In "Fugue for Tinhorns" from the Broadway musical Guys and Dolls

''Guys and Dolls'' is a musical with music and lyrics by Frank Loesser and book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. It is based on "The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown" (1933) and "Blood Pressure", which are two short stories by Damon Runyon, and also bo ...

, written by Frank Loesser

Frank Henry Loesser (; June 29, 1910 – July 28, 1969) was an American songwriter who wrote the music and lyrics for the Broadway musicals ''Guys and Dolls'' and ''How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying'', among others. He won a Tony ...

, the characters Nicely-Nicely, Benny, and Rusty sing simultaneously about hot tips they each have in an upcoming horse race

Horse racing is an equestrian performance sport, typically involving two or more horses ridden by jockeys (or sometimes driven without riders) over a set distance for competition. It is one of the most ancient of all sports, as its basic p ...

.

In "West Side Story", the dance sequence following the song "Cool" is structured as a fugue. Interestingly, Leonard Bernstein quotes Beethoven's monumental "Grosse Fugue" for string quartet and employs Arnold Schoenberg's twelve tone technique, all in the context of a jazz infused Broadway show stopper.

A few examples also exist within progressive rock

Progressive rock (shortened as prog rock or simply prog; sometimes conflated with art rock) is a broad genre of rock music that developed in the United Kingdom and United States through the mid- to late 1960s, peaking in the early 1970s. Init ...

, such as the central movement of " The Endless Enigma" by Emerson, Lake & Palmer

Emerson, Lake & Palmer (informally known as ELP) were an English progressive rock supergroup formed in London in 1970. The band consisted of Keith Emerson (keyboards), Greg Lake (vocals, bass, guitar, producer) and Carl Palmer (drums, percus ...

and "On Reflection