The history of Florida can be traced to when the first Native Americans began to inhabit the peninsula as early as 14,000 years ago. They left behind artifacts and archeological evidence. Florida's

written history

Recorded history or written history describes the historical events that have been recorded in a written form or other documented communication which are subsequently evaluated by historians using the historical method. For broader world his ...

begins with the arrival of Europeans; the Spanish explorer

Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de León (, , , ; 1474 – July 1521) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' known for leading the first official European expedition to Florida and for serving as the first governor of Puerto Rico. He was born in Santervá ...

in 1513 made the first textual records. The state received its name from that ''

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

'', who called the peninsula ''La Pascua Florida'' in recognition of the verdant landscape and because it was the Easter season, which the Spaniards called ''

Pascua Florida

Pascua Florida (pronounced ) is a Spanish term that means "flowery festival" or "feast of flowers" and is an annual celebration of Juan Ponce de León's arrival in what is now the state of Florida. While the holiday is normally celebrated on Apri ...

'' (Festival of Flowers).

This area was the first mainland realm of the United States to be settled by

Europeans

Europeans are the focus of European ethnology, the field of anthropology related to the various ethnic groups that reside in the states of Europe. Groups may be defined by common genetic ancestry, common language, or both. Pan and Pfeil (2004) ...

. Thus, 1513 marked the beginning of the

American frontier

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of United States territorial acquisitions, American expansion in mainland North Amer ...

. From that time of contact, Florida has had many waves of colonization and immigration, including French and Spanish settlement during the 16th century, as well as entry of new Native American groups migrating from elsewhere in the South, and free black people and fugitive slaves, who in the 19th century became allied with the Native Americans as

Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves, who allied with Seminol ...

. Florida was under colonial rule by

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

from the 16th century to the 19th century, and briefly by

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

during the 18th century (1763–1783) before becoming a

territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

of the United States in 1821. Two decades later, on March 3, 1845, Florida was admitted to the Union as the 27th U.S. state.

Florida is nicknamed the "Sunshine State" due to its warm climate and days of sunshine. Florida's sunny climate, many beaches, and growth of industries have attracted northern migrants within the United States, international migrants, and vacationers since the

Florida land boom of the 1920s

The Florida land boom of the 1920s was Florida's first real estate bubble. This pioneering era of Florida land speculation lasted from 1924 to 1926 and attracted investors from all over the nation. The land boom left behind entirely new, planned ...

. A diverse population, urbanization, and a diverse economy would develop in Florida throughout the 20th century. In 2014, Florida with over 19 million people, surpassed New York and became the third most

populous state in the U.S.

The economy of Florida has changed over its history, starting with

natural resource exploitation in logging, mining, fishing, and

sponge diving

Sponge diving is underwater diving to collect soft natural sponges for human use.

Background

Most sponges are too rough for general use due to their structural spicules composed of calcium carbonate or silica. But two genera, ''Hippospongia'' ...

; as well as

cattle ranching

A ranch (from es, rancho/Mexican Spanish) is an area of land, including various structures, given primarily to ranching, the practice of raising grazing livestock such as cattle and sheep. It is a subtype of a farm. These terms are most often ...

, farming, and

citrus growing. The tourism, real estate, trade, banking, and

retirement destination businesses would develop as economic sectors later on.

Early history

Geology

The foundation of Florida was located in the continent of

Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final stages ...

at the South Pole 650 million years ago (Mya). When Gondwana collided with the continent of

Laurentia

Laurentia or the North American Craton is a large continental craton that forms the ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of North America, although ...

300 Mya, it had moved further north. 200 Mya, the merged continents containing what would be Florida, had moved north of the equator. By then, Florida was surrounded by desert, in the middle of a new continent,

Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

. When Pangaea broke up 115 mya, Florida assumed a shape as a peninsula.

The emergent

landmass

A landmass, or land mass, is a large region or area of land. The term is often used to refer to lands surrounded by an ocean or sea, such as a continent or a large island. In the field of geology, a landmass is a defined section of continental ...

of Florida was

Orange Island

Orange Island was a rock band based out of the town Clinton, Massachusetts. Orange Island formed in 1996 when cousins Charles Young and Brendan Dickhaut started writing music together and had David Chouinard playing bass guitar. After writing song ...

, a low-relief island sitting atop the carbonate

Florida Platform which emerged about 34 to 28 million years ago. When

glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

locked up the world's water, starting 2.58 million years ago, the sea level dropped precipitously. It was approximately lower than present levels. As a result, the Florida peninsula not only emerged, but had a land area about twice what it is today. Florida also had a drier and cooler climate than in more recent times. There were few flowing rivers or

wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The ...

s.

First Floridians

Paleo-Indians entered what is now Florida at least 14,000 years ago, during the

last glacial period.

With lower sea levels, the Florida peninsula was much wider, and the climate was cooler and much drier than in the present day. Fresh water was available only in

sinkhole

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are locally also known as ''vrtače'' and shakeholes, and to openi ...

s and

limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

catchment basins, and paleo-Indian activity centered around these relatively scarce watering holes. Sinkholes and basins in the beds of modern rivers (such as the

Page-Ladson site in the

Aucilla River

The Aucilla River rises in Brooks County, Georgia, USA, close to Thomasville, and passes through the Big Bend region of Florida, emptying into the Gulf of Mexico at Apalachee Bay. Some early maps called it the Ocilla River. It is long and ha ...

) have yielded a rich trove of paleo-Indian

artifacts, including

Clovis points.

[

Excavations at an ancient stone ]quarry

A quarry is a type of open-pit mine in which dimension stone, rock, construction aggregate, riprap, sand, gravel, or slate is excavated from the ground. The operation of quarries is regulated in some jurisdictions to reduce their envi ...

(the Container Corporation of America site in Marion County) yielded "crude stone implements" showing signs of extensive wear from deposits below those holding Paleo-Indian artifacts. Thermoluminescence dating

Thermoluminescence dating (TL) is the determination, by means of measuring the accumulated radiation dose, of the time elapsed since material containing crystalline minerals was either heated (lava, ceramics) or exposed to sunlight (sediments ...

and weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs ''in situ'' (on site, with little or no movement), ...

analysis independently gave dates of 26,000 to 28,000 years ago for the creation of the artifacts. The findings are controversial, and funding has not been available for follow-up studies.[

As the glaciers began retreating about 8000 ]BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

, the climate of Florida became warmer and wetter. As the glaciers melted, the sea level rose, reducing the land mass. Many prehistoric habitation sites along the old coastline were slowly submerged, making artifacts from early coastal cultures difficult to find. The paleo-Indian culture was replaced by, or evolved into, the Early Archaic culture. With an increase in population and more water available, the people occupied many more locations, as evidenced by numerous artifacts. Archaeologists

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

have learned much about the Early Archaic people of Florida from the discoveries made at Windover Pond. The Early Archaic period evolved into the Middle Archaic period around 5000 BC. People started living in villages near wetlands and along the coast at favored sites that were likely occupied for multiple generations.

The Late Archaic period started about 3000 BC, when Florida's climate had reached current conditions and the sea had risen close to its present level. People commonly occupied both fresh and saltwater wetlands. Large shell middens

A midden (also kitchen midden or shell heap) is an old dump for domestic waste which may consist of animal bone, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and ecofact ...

accumulated during this period. Many people lived in large villages with purpose-built earthwork mound

A mound is a heaped pile of earth, gravel, sand, rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded area of topographically higher el ...

s, such as at Horr's Island

Horr's Island is a significant Archaic period archaeological site located on an island in Southwest Florida formerly known as ''Horr's Island''. Horr's Island (now called ''Key Marco'', not to be confused with the archaeological site Key Marco) i ...

, which had the largest permanently occupied community in the Archaic period in the southeastern United States. It also has the oldest burial mound in the East, dating to about 1450 BC. People began making fired pottery in Florida by 2000 BC. By about 500 BC, the Archaic culture, which had been fairly uniform across Florida, began to fragment into regional cultures.[

The post-Archaic cultures of eastern and southern Florida developed in relative isolation. It is likely that the peoples living in those areas at the time of first European contact were direct descendants of the inhabitants of the areas in late Archaic and ]Woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

times. The cultures of the Florida panhandle and the north and central Gulf

A gulf is a large inlet from the ocean into the landmass, typically with a narrower opening than a bay, but that is not observable in all geographic areas so named. The term gulf was traditionally used for large highly-indented navigable bodie ...

coast of the Florida peninsula were strongly influenced by the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

, producing two local variants known as the Pensacola culture

The Pensacola culture was a regional variation of the Mississippian culture along the Gulf Coast of the United States that lasted from 1100 to 1700 CE. The archaeological culture covers an area stretching from a transitional Pensacola/Fort Walton ...

and the Fort Walton culture.Daytona Beach, Florida

Daytona Beach, or simply Daytona, is a coastal Resort town, resort-city in east-central Florida. Located on the eastern edge of Volusia County, Florida, Volusia County near the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic coastline, its population ...

to a point on or north of Tampa Bay.)

European contact and aftermath

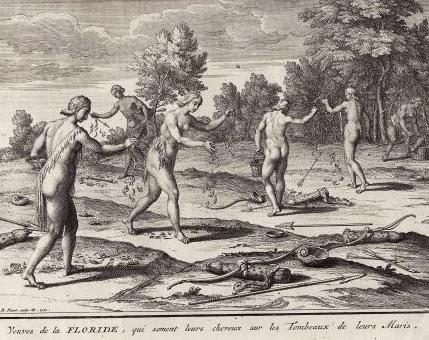

At the time of first European contact in the early 16th century, Florida was inhabited by an estimated 350,000 people belonging to a number of tribes. (Anthropologist

At the time of first European contact in the early 16th century, Florida was inhabited by an estimated 350,000 people belonging to a number of tribes. (Anthropologist Henry F. Dobyns

Henry Farmer Dobyns, Jr. (July 3, 1925 – June 21, 2009) was an anthropologist, author and researcher specializing in the ethnohistory and demography of native peoples in the American hemisphere. has estimated that as many as 700,000 people lived in Florida in 1492). The Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

sent Spanish explorers recording nearly one hundred names of groups they encountered, ranging from organized political entities such as the Apalachee, with a population of around 50,000, to villages with no known political affiliation. There were an estimated 150,000 speakers of dialects of the Timucua language

Timucua is a language isolate formerly spoken in northern and central Florida and southern Georgia by the Timucua peoples. Timucua was the primary language used in the area at the time of Spanish colonization in Florida. Differences among the ...

, but the Timucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The var ...

were organized as groups of villages and did not share a common culture.Ais AIS may refer to:

Medicine

* Abbreviated Injury Scale, an anatomical-based coding system to classify and describe the severity of injuries

* Acute ischemic stroke, the thromboembolic type of stroke

* Androgen insensitivity syndrome, an intersex ...

, Calusa

The Calusa ( ) were a Native American people of Florida's southwest coast. Calusa society developed from that of archaic peoples of the Everglades region. Previous indigenous cultures had lived in the area for thousands of years.

At the time of ...

, Jaega, Mayaimi

The Mayaimi (also Maymi, Maimi) were Native Americans in the United States, Native American people who lived around Lake Mayaimi (now Lake Okeechobee) in the Belle Glade culture, Belle Glade area of Florida from the beginning of the Common Era ...

, Tequesta

The Tequesta (also Tekesta, Tegesta, Chequesta, Vizcaynos) were a Native American tribe. At the time of first European contact they occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They had infrequent contact with Europeans a ...

, and Tocobaga.

The populations of all of these tribes decreased markedly during the period of Spanish control of Florida, mostly due to epidemics of newly introduced infectious diseases

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

, to which the Native Americans had no natural immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

. Beginning late in the 17th century, when most of the indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

were already much reduced in population, tribes

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to conflic ...

from areas to the north of Florida, supplied with arms and occasionally accompanied by white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

colonists from the Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

, raided throughout Florida. They burned villages, wounded many of the inhabitants and carried captives back to Charles Towne to be sold into slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Most of the villages in Florida were abandoned, and the survivors sought refuge at St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afri ...

or in isolated spots around the state. Many tribes became extinct during this period and by the end of the 18th century.[

Some of the Apalachee eventually reached Louisiana, where they survived as a distinct group for at least another century. The Spanish evacuated the few surviving members of the Florida tribes to ]Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

in 1763 when Spain transferred the territory of Florida to the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

following the latter's victory against France in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

.[ In the aftermath, the Seminole, originally an offshoot of the ]Creek people

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands[ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introdu ...]

. They have three federally recognized tribes: the largest is the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, formed of descendants since removal in the 1830s; others are the smaller Seminole Tribe of Florida and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida

The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is a federally recognized Native American tribe in the U.S. state of Florida. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving fed ...

.

Colonial battleground

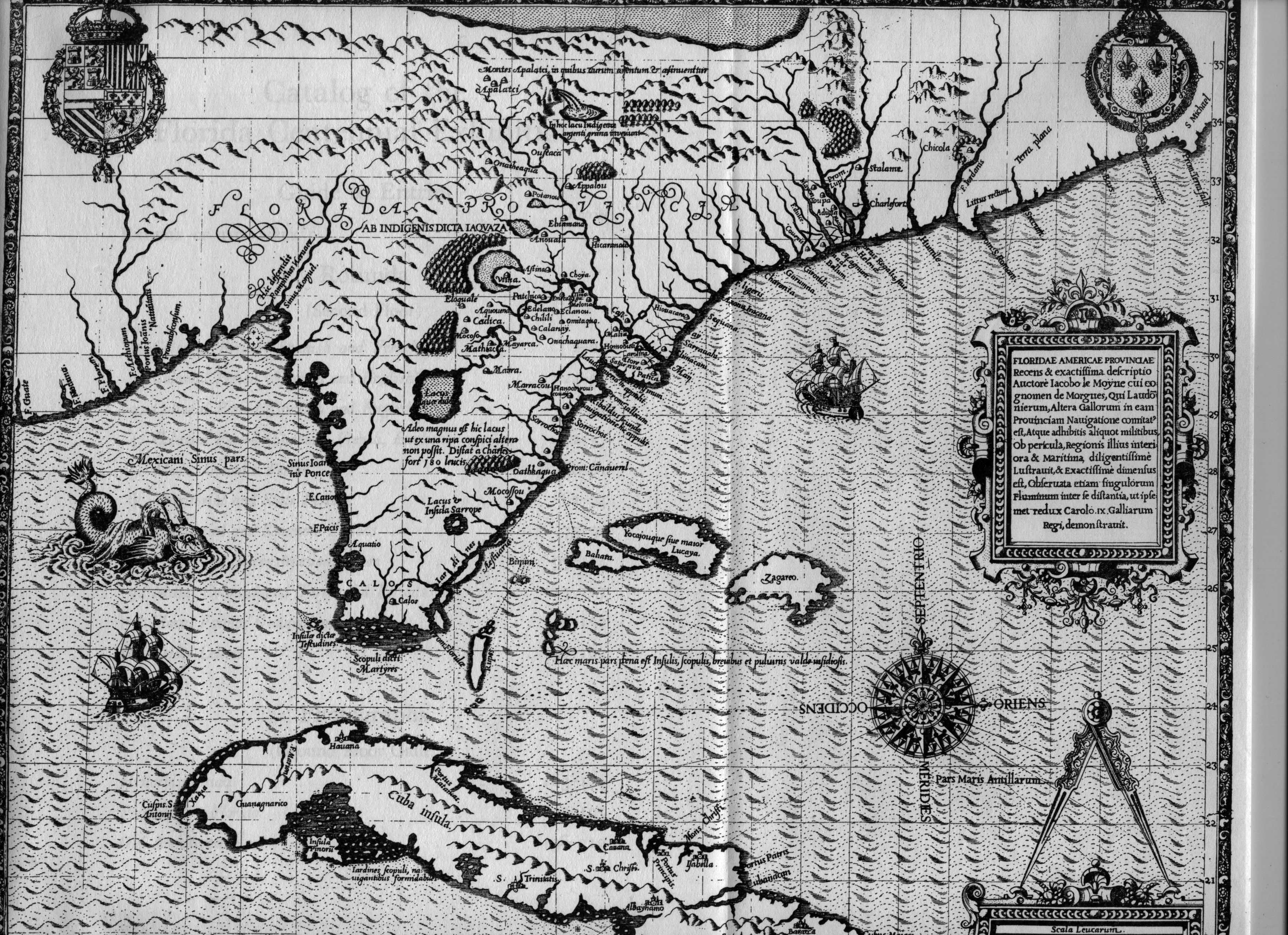

First Spanish rule (1513–1763)

Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de León (, , , ; 1474 – July 1521) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' known for leading the first official European expedition to Florida and for serving as the first governor of Puerto Rico. He was born in Santervá ...

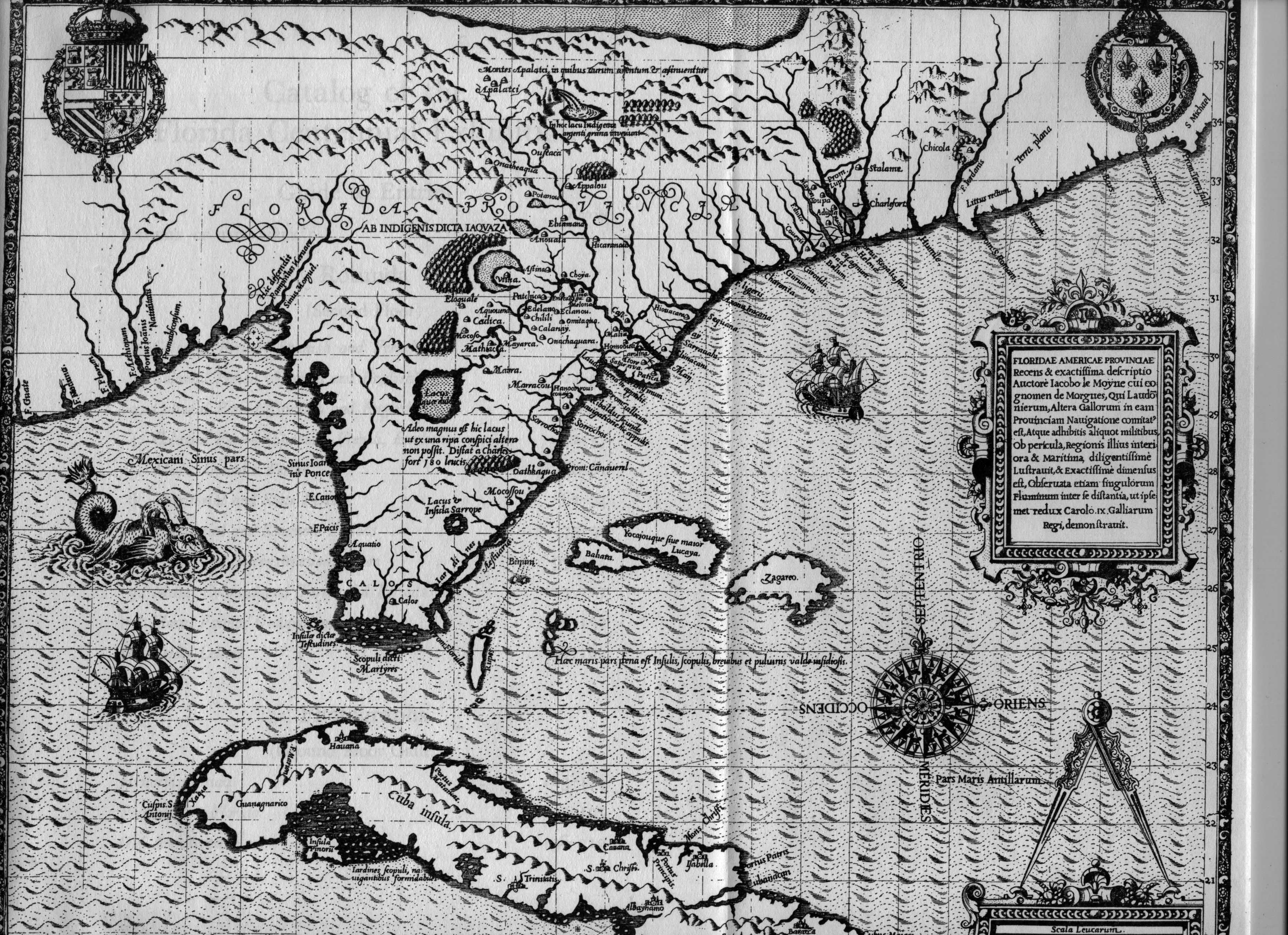

, a famous Spanish conqueror and explorer, is usually given credit for being the first European to sight Florida in 1513, but he probably had predecessors. Florida and much of the nearby coast is depicted in the Cantino planisphere

The Cantino planisphere or Cantino world map is a manuscript Portuguese world map preserved at the Biblioteca Estense in Modena, Italy. It is named after Alberto Cantino, an agent for the Duke of Ferrara, who successfully smuggled it from Portugal ...

, an early world map which was surreptitiously copied in 1502 from the most current Portuguese sailing charts and smuggled into Italy a full decade before Ponce sailed north from Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

on his voyage of exploration. Ponce de León may not have even been the first Spaniard to go ashore in Florida; slave traders may have secretly raided native villages before Ponce arrived, as he encountered at least one indigenous tribesman who spoke Spanish. However, Ponce's 1513 expedition to Florida was the first open and official one. He also gave Florida its name, which means "full of flowers." A dubious legend states that Ponce de León was searching for the Fountain of Youth on the island of Bimini, based on information from natives.Pascua Florida

Pascua Florida (pronounced ) is a Spanish term that means "flowery festival" or "feast of flowers" and is an annual celebration of Juan Ponce de León's arrival in what is now the state of Florida. While the holiday is normally celebrated on Apri ...

, on April 7 and named the land ''La Pascua de la Florida.'' After briefly exploring the land south of present-day St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afri ...

, the expedition sailed south to the bottom of the Florida peninsula, through the Florida Keys

The Florida Keys are a coral cay archipelago located off the southern coast of Florida, forming the southernmost part of the continental United States. They begin at the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula, about south of Miami, and e ...

, and up the west coast as far north as Charlotte Harbor, where they briefly skirmished with the Calusa

The Calusa ( ) were a Native American people of Florida's southwest coast. Calusa society developed from that of archaic peoples of the Everglades region. Previous indigenous cultures had lived in the area for thousands of years.

At the time of ...

before heading back to Puerto Rico.

From 1513 onward, the land became known as ''La Florida''. After 1630, and throughout the 18th century, Tegesta (after the Tequesta

The Tequesta (also Tekesta, Tegesta, Chequesta, Vizcaynos) were a Native American tribe. At the time of first European contact they occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They had infrequent contact with Europeans a ...

tribe) was an alternate name of choice for the Florida peninsula following publication of a map by the Dutch cartographer Hessel Gerritsz in Joannes de Laet Joannes or Johannes De Laet (Latinized as ''Ioannes Latius'') (1581 in Antwerp – buried 15 December 1649, in Leiden) was a Dutch geographer and director of the Dutch West India Company. Philip Burden called his ''History of the New World'', " ...

's ''History of the New World''.Pánfilo de Narváez

Pánfilo de Narváez (; 147?–1528) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' and soldier in the Americas. Born in Spain, he first embarked to Jamaica in 1510 as a soldier. He came to participate in the conquest of Cuba and led an expedition to Camagüey ...

's expedition explored Florida's west coast in 1528, but his violent demands for gold and food led to hostile relations with the Tocobaga and other native groups. Facing starvation and unable to find his support ships, Narváez attempted return to Mexico via rafts, but all were lost at sea and only four members of the expedition survived. Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

landed in Florida in 1539 and began a multi-year trek through what is now the southeastern United States in which he found no gold and lost his life. In 1559 Tristán de Luna y Arellano established the first settlement in Pensacola but, after a violent hurricane destroyed the area, it was abandoned in 1561.

The horse, which the natives had hunted to extinction 10,000 years ago, was reintroduced into North America by the European explorers, and into Florida in 1538.1564

Year 1564 ( MDLXIV) was a leap year starting on Saturday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

January–June

* January 26 – Livonian War – Battle of Ula: A Lithuanian surprise attack result ...

, René Goulaine de Laudonnière

Rene Goulaine de Laudonnière (c. 1529–1574) was a French Huguenot explorer and the founder of the French colony of Fort Caroline in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, a Huguenot, sent Jean Ribault and Laudonnière ...

founded Fort Caroline in what is now Jacksonville, as a haven for Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

Protestant refugees from religious persecution in France.Pedro Menéndez de Avilés

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (; ast, Pedro (Menéndez) d'Avilés; 15 February 1519 – 17 September 1574) was a Spanish admiral, explorer and conquistador from Avilés, in Asturias, Spain. He is notable for planning the first regular trans-oceani ...

founded San Agustín (St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afri ...

)[ which is the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in any U.S. state. It is second oldest only to ]San Juan, Puerto Rico

San Juan (, , ; Spanish for "Saint John") is the capital city and most populous municipality in the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States. As of the 2020 census, it is the 57th-largest city under the jur ...

, in the United States' current territory. From this base of operations, the Spanish began building Catholic missions

Missionary work of the Catholic Church has often been undertaken outside the geographically defined parishes and dioceses by religious orders who have people and material resources to spare, and some of which specialized in missions. Eventually, p ...

.

All colonial cities were founded near the mouths of rivers. St. Augustine was founded where the Matanzas Inlet

Matanzas Inlet is a channel in Florida between two barrier islands and the mainland, connecting the Atlantic Ocean and the south end of the Matanzas River. It is south of St. Augustine, in the southern part of St. Johns County. The inlet is no ...

permitted access to the Matanzas River

The Matanzas River is a body of water in St. Johns and Flagler counties in the U.S. state of Florida. It is a narrow saltwater bar-bounded estuary sheltered from the Atlantic Ocean by Anastasia Island.

The Matanzas River is in lengthU.S. Geolo ...

. Other cities were founded on the sea with similar inlets: Jacksonville, West Palm Beach, Fort Lauderdale, Miami, Pensacola, Tampa, Fort Myers, and others.[ Two years later, ]Dominique de Gourgue

Dominique (or Domingue) de Gourgues (1530–1593) was a French nobleman and soldier. He is best known for leading an attack against Spanish Florida in 1568, in response to the destruction of the French Fort Caroline. He was a captain in King Char ...

recaptured the settlement for France, this time slaughtering the Spanish defenders.

St. Augustine became the most important settlement in Florida. Little more than a fort, it was frequently attacked and burned, with most residents killed or fled. It was notably devastated in 1586, when English sea captain and sometime pirate Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 (t ...

plundered and burned the city. Catholic missionaries used St. Augustine as a base of operations to establish over 100 far-flung missions throughout Florida.Castillo de San Marcos

The Castillo de San Marcos (Spanish for "St. Mark's Castle") is the oldest masonry fort in the continental United States; it is located on the western shore of Matanzas Bay in the city of St. Augustine, Florida.

It was designed by the Spanish ...

(1672) and Fort Matanzas

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

(1742).

African slaves used primarily for labor were first introduced to Spanish Florida as early as 1580, when officials asked for permission to import slaves to bolster the workforce in and around St. Augustine. However, due to restrictions by the Spanish crown, the population of African slaves in Florida remained relatively low until around the period of British control in 1763.Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

and Carolina

Carolina may refer to:

Geography

* The Carolinas, the U.S. states of North and South Carolina

** North Carolina, a U.S. state

** South Carolina, a U.S. state

* Province of Carolina, a British province until 1712

* Carolina, Alabama, a town in ...

gradually pushed the boundaries of Spanish territory south, while the French settlements along the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

encroached on the western borders of the Spanish claim. In 1702, Governor of Carolina James Moore and allied Yamasee and Creek Indians attacked and razed the town of St. Augustine, but they could not gain control of the fort. In 1704, Moore and his soldiers began burning Spanish missions in north Florida and executing Indians friendly with the Spanish. The collapse of the Spanish mission system and the defeat of the Spanish-allied Apalachee Indians (the Apalachee massacre) opened Florida up to slave raids, which reached to the Florida Keys and decimated the native population. The Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

of 1715–1717 in the Carolinas resulted in numerous Indian refugees, such as the Yamasee, moving south to Florida. In 1719, the French captured the Spanish settlement at Pensacola.

Fugitive slaves and conflicts

The border between the British colony of Georgia and Spanish Florida was never clearly defined, and was the subject of constant harassment in both directions, until it was ceded by Spain to the U.S. in 1821. The Spanish Crown

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

, beginning with King Charles II in 1693, encouraged fugitive slaves from the British North American colonies

The British colonization of the Americas was the history of establishment of control, settlement, and colonization of the continents of the Americas by England, Scotland and, after 1707, Great Britain. Colonization efforts began in the late 1 ...

to escape and offered them freedom and refuge if they converted to Catholicism. This was well known through word of mouth in the colonies of Georgia and South Carolina, and hundreds of enslaved Africans

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

escaped to their freedom, which infuriated colonists in the British North American colonies. They settled in a buffer community north of St. Augustine, called Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose

Fort Mose Historic State Park (originally known as Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, and later Fort Mose; alternatively, Fort Moosa or Fort Mossa), is a former Spanish fort in St. Augustine, Florida. In 1738, the governor of Spanish Florida, Ma ...

, the first settlement made of free black people in North America.

During this period, the British (including their North American colonies) repeatedly attacked Spanish Florida, especially in 1702 and again in 1740, when a large force under James Oglethorpe

James Edward Oglethorpe (22 December 1696 – 30 June 1785) was a British soldier, Member of Parliament, and philanthropist, as well as the founder of the colony of Georgia in what was then British America. As a social reformer, he hoped to re ...

sailed south from Georgia and besieged St. Augustine, but was unable to capture the Castillo de San Marcos

The Castillo de San Marcos (Spanish for "St. Mark's Castle") is the oldest masonry fort in the continental United States; it is located on the western shore of Matanzas Bay in the city of St. Augustine, Florida.

It was designed by the Spanish ...

. The 1755 Lisbon earthquake

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake, also known as the Great Lisbon earthquake, impacted Portugal, the Iberian Peninsula, and Northwest Africa on the morning of Saturday, 1 November, Feast of All Saints, at around 09:40 local time. In combination with ...

triggered a tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater explo ...

that would have struck Central Florida with an estimated wave.

Creek and Seminole Native Americans, who had established buffer settlements in Florida at the invitation of the Spanish government, also welcomed any fugitive slaves which reached their settlements. In 1771, Governor John Moultrie wrote to the Board of Trade

The Board of Trade is a British government body concerned with commerce and industry, currently within the Department for International Trade. Its full title is The Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council appointed for the consideration of ...

that "it has been a practice for a good while past, for negroes to run away from their Masters, and get into the Indian towns, from whence it proved very difficult to get them back." When British colonial officials in Florida pressed the Seminole to return runaway slaves, they replied that they had "merely given hungry people food, and invited the slaveholders to catch the runaways themselves."

British rule (1763–1783)

In

In 1763

Events

January–March

* January 27 – The seat of colonial administration in the Viceroyalty of Brazil is moved from Salvador to Rio de Janeiro.

* February 1 – The Royal Colony of North Carolina officially creates Meck ...

, Spain traded Florida to the Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

for control of Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center. , Cuba, which had been captured by the British during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

. It was part of a large expansion of British territory following the country's victory in the Seven Years' War. Almost the entire Spanish population left, taking along most of the remaining indigenous population to Cuba. The British divided the territory into East Florida and West Florida.St. Johns River

The St. Johns River ( es, Río San Juan) is the longest river in the U.S. state of Florida and its most significant one for commercial and recreational use. At long, it flows north and winds through or borders twelve counties. The drop in eleva ...

at a narrow point, which the Seminole called ''Wacca Pilatka'' and the British named "Cow Ford", both names ostensibly reflecting the fact that cattle were brought across the river there. The British government gave land grants to officers and soldiers who had fought in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

in order to encourage settlement. In order to induce settlers to move to the two new colonies reports of the natural wealth of Florida were published in England. A large number of British colonists who were "energetic and of good character" moved to Florida, mostly coming from South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, Georgia and England, though there was also a group of settlers who came from the colony of Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

. This would be the first permanent English-speaking population in what is now Duval County, Baker County, St. Johns County

St. Johns County is a county in the northeastern part of the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2020 United States Census, its population was 273,425. The county seat and largest incorporated city is St. Augustine. St. Johns County is part of the ...

, and Nassau County. The British built good public roads and introduced the cultivation of sugar cane, indigo, and fruits, as well the export of lumber. As a result of these initiatives northeastern Florida prospered economically in a way it never did under Spanish rule. Furthermore, the British governors were directed to call general assemblies as soon as possible to make laws for the Floridas and in the meantime they were, with the advice of councils, to establish courts. This would be the first introduction of much of the English-derived legal system which Florida still has today, including trial by jury

A jury trial, or trial by jury, is a legal proceeding in which a jury makes a decision or findings of fact. It is distinguished from a bench trial in which a judge or panel of judges makes all decisions.

Jury trials are used in a significant ...

, habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

, and county-based government.

A Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

settler named Dr. Andrew Turnbull

Andrew is the English form of a given name common in many countries. In the 1990s, it was among the top ten most popular names given to boys in English-speaking countries. "Andrew" is frequently shortened to "Andy" or "Drew". The word is derived ...

transplanted around 1,500 indentured settlers, from Menorca

Menorca or Minorca (from la, Insula Minor, , smaller island, later ''Minorica'') is one of the Balearic Islands located in the Mediterranean Sea belonging to Spain. Its name derives from its size, contrasting it with nearby Majorca. Its capi ...

, Majorca

Mallorca, or Majorca, is the largest island in the Balearic Islands, which are part of Spain and located in the Mediterranean.

The capital of the island, Palma, is also the capital of the autonomous community of the Balearic Islands. The Bal ...

, Ibiza

Ibiza (natively and officially in ca, Eivissa, ) is a Spanish island in the Mediterranean Sea off the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. It is from the city of Valencia. It is the third largest of the Balearic Islands, in Spain. Its l ...

, Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

, Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

, Mani Peninsula

The Mani Peninsula ( el, Μάνη, Mánē), also long known by its medieval name Maina or Maïna (Μαΐνη), is a geographical and cultural region in Southern Greece that is home to the Maniots (Mανιάτες, ''Maniátes'' in Greek), who cla ...

, and Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, to grow hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

, sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with ...

, indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', m ...

, and to produce rum. Settled at New Smyrna, within months the colony suffered major losses primarily due to insect-borne diseases and Native American raids. Most crops did not do well in the sandy Florida soil. Those that survived rarely equaled the quality produced in other colonies. The colonists tired of their servitude and Turnbull's rule. On several occasions, he used African slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

to whip his unruly settlers. The settlement collapsed and the survivors fled to safety with the British authorities in St. Augustine. Their descendants survive to this day, as does the name New Smyrna.

In 1767, the British moved the northern boundary of West Florida to a line extending from the mouth of the Yazoo River

The Yazoo River is a river in the U.S. states of Louisiana and Mississippi. It is considered by some to mark the southern boundary of what is called the Mississippi Delta, a broad floodplain that was cultivated for cotton plantations before the ...

east to the Chattahoochee River

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the confluence of the Chatta ...

(32° 28′north latitude), consisting of approximately the lower third of the present states of Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

. During this time, Creek Indians migrated into Florida and formed the Seminole tribe.

Florida in the American Revolutionary War

When representatives from thirteen North American colonies declared independence from Great Britain in 1776, many Floridians condemned the action. East and West Florida were backwater outposts whose populations included a large percentage of British military personnel and their families. There was little trade in or out of the colonies, so they were largely unaffected by the Stamp Act Crisis of 1765 and other taxes and policies which brought other British colonies together in common interest against a shared threat. Thus, a majority of Florida residents were Loyalists, and both East and West Florida declined to send representatives to any sessions of the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

.

During the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, some Floridians actually helped lead raids into nearby states. Continental forces attempted to invade East Florida early in the conflict, but they were defeated on May 17, 1777, at the Battle of Thomas Creek

The Battle of Thomas Creek, also known as the Thomas Creek Massacre, was an ambush of a small detachment of mounted Georgia Militia by a mixed force of British soldiers, Loyalist militia, and British-allied Indians on May 17, 1777 near the mout ...

in today's Nassau County when American Colonel John Baker surrendered to the British.Battle of Alligator Bridge

The Battle of Alligator Bridge took place on June 30, 1778, and was the only major engagement in an unsuccessful campaign to conquer British East Florida during the American Revolutionary War. A detachment of Georgia militiamen under the comma ...

on June 30, 1778.

The two Floridas remained loyal to Great Britain throughout the war. However, Spain, participating indirectly in the war as an ally of France, captured Pensacola from the British in 1781. The Peace of Paris (1783) ended the Revolutionary War and returned all of Florida to Spanish control, but without specifying the boundaries. The Spanish wanted the expanded northern boundary Britain had made to West Florida, while the new United States demanded the old boundary at the 31st parallel north

The 31st parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 31 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Africa, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America and the Atlantic Ocean. At this latitude the sun is visible for 14 hours, 10 ...

. This border controversy was resolved in the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed on October 27, 1795 by the United States and Spain.

It defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United S ...

when Spain recognized the 31st parallel as the boundary.

Departure of the British

Just as most residents of Spanish Florida had left when Britain gained possession of the territory in 1763, the impending return to Spanish control in 1783 saw a vast exodus of those who had settled in the area over the previous twenty years. This included many Loyalists who had fled there during the American War of Independence and had caused East Florida's population to swell considerably if temporarily.

Second Spanish rule (1783–1821)

Spain's reoccupation of Florida involved the arrival of some officials and soldiers at St. Augustine and Pensacola but very few new settlers. Most British residents had departed, leaving much of the territory depopulated and unguarded. North Florida continued to be the home of the newly amalgamated black–native American Seminole culture and a haven for people escaping slavery in the southern United States. Settlers in southern Georgia demanded that Spain control the Seminole population and capture runaway slaves, to which Spain replied that the slave owners were welcome to recapture the runaways themselves.

Americans began moving into northern Florida from the backwoods of Georgia and South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. Though technically not allowed by the Spanish authorities, the Spanish were never able to effectively police the border region, and a mix of American settlers, escaped slaves, and Native Americans would continue to migrate into Florida unchecked. The American migrants, mixing with the few remaining settlers from Florida's British period, would be the progenitors of the population known as Florida Cracker

Florida crackers were colonial-era British and American pioneer settlers in what is now the U.S. state of Florida; the term is also applied to their descendants, to the present day, and their subculture among white Southerners. The first cracker ...

s.

Republic of West Florida

Ignoring Spanish territorial claims, American settlers, along with some remaining British settlers, established a permanent foothold in the western end of West Florida during the first decade of the 1800s. In the summer of 1810, they began planning a rebellion against Spanish rule which became open revolt in September. The rebels overcame the Spanish garrison at Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge ( ; ) is a city in and the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-sma ...

and proclaimed the "Free and Independent Republic of West Florida" on September 23. (None of it was within what is today the state of Florida.) Their flag was the original " Bonnie Blue Flag", a single white star on a blue field. On October 27, 1810, most of the Republic of West Florida was annexed by proclamation of President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, who claimed that the region was included in the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

and incorporated it into the newly formed Territory of Orleans

The Territory of Orleans or Orleans Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from October 1, 1804, until April 30, 1812, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Louisiana.

History

In 1804, ...

. Some leaders of the newly declared republic objected to the takeover, but all had deferred to arriving American troops by mid-December 1810. The Florida Parishes of the modern state of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

include most of the territory claimed by the short-lived Republic of West Florida.

Spain sided with Great Britain during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, and the U.S. annexed the Mobile District of West Florida to the Mississippi Territory

The Territory of Mississippi was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 7, 1798, until December 10, 1817, when the western half of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Mississippi. T ...

in May 1812. The surrender of Spanish forces at Mobile in April 1813 officially established American control over the area, which was eventually divided between the states of Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

.

Republic of East Florida

In March 1812, Americans took control of Amelia Island on the Atlantic coast declared that they were a republic free from Spanish rule in what would become known as the Patriot War. The revolt was organized by General George Mathews of the U.S. Army, who had been authorized to secretly negotiate with the Spanish governor for American acquisition of East Florida. Instead, Mathews organized a group of frontiersmen in Georgia, who arrived at the Spanish town of Fernandina and demanded the surrender of all of Amelia Island. Upon declaring the island a republic, he led his volunteers along with a contingent of regular army troops south towards St. Augustine.

Upon hearing of Mathews' actions, Congress became alarmed that he would provoke war with Spain, and Secretary of State James Monroe ordered Matthews to return all captured territory to Spanish authorities. After several months of negotiations on the withdrawal of the Americans and compensation for their foraging through the countryside, the countries came to an agreement, and Amelia Island was returned to the Spanish in May 1813.

First Seminole War

The unguarded Florida border was an increasing source of tension late in the second Spanish period. Seminoles based in East Florida had been accused of raiding Georgia settlements, and settlers were angered by the stream of slaves escaping into Florida, where they were welcomed. Negro Fort

Negro Fort (African Fort) was a short-lived fortification built by the British in 1814, during the War of 1812, in a remote part of what was at the time Spanish Florida. It was intended to support a never-realized British attack on the U.S. via i ...

, an abandoned British fortification in the far west of the territory, was manned by both indigenous and black people. The United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

would lead increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory, including the 1817–1818 campaign against the Seminole Indians by Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

that became known later as the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

. Jackson took temporary control of Pensacola in 1818, and though he withdrew due to Spanish objections, the United States continued to effectively control much of West Florida. According to Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, this was necessary because Florida had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them."

End of Spanish control

After Jackson's incursions, Spain decided that Florida had become too much of a burden, as it could not afford to send settlers or garrisons to properly occupy the land and was receiving very little revenue from the territory. Madrid therefore decided to cede Florida to the United States. The transfer was negotiated as part of the Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined t ...

, which also settled several boundary disputes between Spanish colonies and the U.S. in exchange for American payment of $5,000,000 in claims against the Spanish government.

Territory and statehood

Florida Territory (1822–1845)

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

became an organized territory

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions overseen by the federal government of the United States. The various American territories differ from the U.S. states and tribal reservations as they are not sover ...

of the United States on March 30, 1822. The Americans merged East Florida and West Florida (although the majority of West Florida was annexed to Territory of Orleans

The Territory of Orleans or Orleans Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from October 1, 1804, until April 30, 1812, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Louisiana.

History

In 1804, ...

and Mississippi Territory

The Territory of Mississippi was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 7, 1798, until December 10, 1817, when the western half of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Mississippi. T ...

), and established a new capital in Tallahassee, conveniently located halfway between the East Florida capital of St. Augustine and the West Florida capital of Pensacola. The boundaries of Florida's first two counties, Escambia and St. Johns, approximately coincided with the boundaries of West and East Florida respectively.

The free black and Indigenous slaves, Black Seminoles, living near St. Augustine, fled to Havana, Cuba to avoid coming under US control. Some Seminole also abandoned their settlements and moved further south. Hundreds of Black Seminoles

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves, who allied with Seminol ...

and fugitive slaves escaped in the early nineteenth century from Cape Florida

Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Recreation Area occupies approximately the southern third of the island of Key Biscayne, at coordinates . This park includes the Cape Florida Light, the oldest standing structure in Greater Miami. In 2005, it was ra ...

to The Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, where they settled on Andros Island.

As settlement increased, pressure grew on the United States government to remove the Indians from their lands in Florida. Many settlers in Florida developed plantation agriculture, similar to other areas of the Deep South. To the consternation of new landowners, the Seminoles harbored and integrated runaway black slaves, and clashes between whites and Indians grew with the influx of new settlers.

In 1832, the United States government signed the

As settlement increased, pressure grew on the United States government to remove the Indians from their lands in Florida. Many settlers in Florida developed plantation agriculture, similar to other areas of the Deep South. To the consternation of new landowners, the Seminoles harbored and integrated runaway black slaves, and clashes between whites and Indians grew with the influx of new settlers.

In 1832, the United States government signed the Treaty of Payne's Landing

The Treaty of Payne's Landing (Treaty with the Seminole, 1832) was an agreement signed on 9 May 1832 between the government of the United States and several chiefs of the Seminole Indians in the Territory of Florida, before it acquired statehood.

...

with some of the Seminole chiefs, promising them lands west of the Mississippi River if they agreed to leave Florida voluntarily. Many Seminoles left then, while those who remained prepared to defend their claims to the land. White settlers pressured the government to remove all of the Indians, by force if necessary, and in 1835, the U.S. Army arrived to enforce the treaty.

The Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans and ...

began at the end of 1835 with the Dade Battle

The Dade battle (often called the Dade massacre) was an 1835 military defeat for the United States Army. The U.S. was attempting to force the Seminoles to move away from their land in Florida and relocate to Indian Territory (in what would becom ...

, when Seminoles ambushed Army troops marching from Fort Brooke

Fort Brooke was a historical military post established at the mouth of the Hillsborough River in present-day Tampa, Florida in 1824. Its original purpose was to serve as a check on and trading post for the native Seminoles who had been confined ...

(Tampa) to reinforce Fort King

Fort King (also known as Camp King or Cantonment King) was a United States military fort in north central Florida, near what later developed as the city of Ocala. It was named after Colonel William King, commander of Florida's Fourth Infantry and ...

(Ocala). They killed or mortally wounded all but one of the 110 troops. Between 900 and 1,500 Seminole warriors effectively employed guerrilla tactics against United States Army troops for seven years. Osceola, a charismatic young war leader, came to symbolize the war and the Seminoles after he was arrested by Brigadier General Joseph Marion Hernandez

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

while negotiating under a white truce flag in October 1837, by order of General Thomas Jesup. First imprisoned at Fort Marion, he died of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

at Fort Moultrie in South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

less than three months after his capture. The war ended in 1842. The U.S. government is estimated to have spent between $20 million ($ in dollars) and $40 million ($ in dollars) on the war; at the time, this was considered a large sum. Almost all of the Seminoles were forcibly exiled to Creek lands west of the Mississippi; several hundred remained in the Everglades

The Everglades is a natural region of tropical climate, tropical wetlands in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Florida, comprising the southern half of a large drainage basin within the Neotropical realm. The system begins near Orland ...

.[

]

Statehood (1845)

On March 3, 1845, Florida became the 27th state of the United States of America. Its first governor was

On March 3, 1845, Florida became the 27th state of the United States of America. Its first governor was William Dunn Moseley

William Dunn Moseley (February 1, 1795January 4, 1863) was an American politician. A Democrat and North Carolina native, Moseley became the first Governor of the state of Florida, serving from 1845 until 1849 and leading the establishment of t ...

.

Almost half the state's population were enslaved African Americans working on large cotton and sugar plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

, between the Apalachicola and Suwannee rivers in the north central part of the state.[ Like the people who owned them, many slaves had come from the coastal areas of Georgia and the Carolinas. They were part of the Gullah–]Geechee

The Gullah () are an African American ethnic group who predominantly live in the Lowcountry region of the U.S. states of Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, and North Carolina, within the coastal plain and the Sea Islands. Their language and cultu ...

culture of the Lowcountry. Others were enslaved African Americans from the upper South who had been sold to traders taking slaves to the deep South.

In the 1850s, with the potential transfer of ownership of federal land to the state, including Seminole land, the federal government decided to convince the remaining Seminoles to emigrate. The Army reactivated Fort Harvie and renamed it to Fort Myers. Increased Army patrols led to hostilities, and eventually a Seminole attack on Fort Myers which killed two United States soldiers.[ The ]Third Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

lasted from 1855 to 1858 which ended with most of the remaining Seminoles, mostly women and children moving to Indian Territory. In 1859, another 75 Seminoles surrendered and were sent to the West, but a small number continued to live in the Everglades.[

On the eve of the Civil War, Florida had the smallest population of the Southern states. It was invested in plantation agriculture, which was dependent on the labor of enslaved African Americans. By 1860, Florida had 140,424 people, of whom 44% were enslaved and fewer than 1,000 were ]free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

.[ Florida also had one of the highest per capita murder rates prior to the Civil War, thanks to a weakened central government, the institution of slavery, and a troubled political history.

]

Civil War through late 19th century

Following

Following Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

's election in 1860, Florida joined other Southern states in seceding from the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

. Secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

took place January 10, 1861, and after less than a month as an independent republic, Florida became one of the founding seven states of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

. During the Civil War, Florida was an important supply route for the Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

. Therefore, Union forces operated a naval blockade

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It includ ...

around the entire state, and Union troops occupied major ports such as Cedar Key, Jacksonville, Key West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

, and Pensacola. Though numerous skirmishes occurred in Florida, including the Battle of Natural Bridge

The Battle of Natural Bridge was fought during the American Civil War in what is now Woodville, Florida near Tallahassee on March 6, 1865. A small group of Confederate troops and volunteers, which included teenagers from the nearby Florida Mil ...

, the Battle of Marianna

The Battle of Marianna was a small but significant engagement on September 27, 1864, in the panhandle of Florida during the American Civil War. The Union destruction against Confederates and militia defending the town of Marianna was the culm ...

and the Battle of Gainesville

The Battle of Gainesville was an American Civil War engagement fought on August 17, 1864, when a Confederate force defeated Union detachments from Jacksonville, Florida. The result of the battle was the Confederate occupation of Gainesville for ...

, the only major battle was the Battle of Olustee near Lake City.

Reconstruction era

During the Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

that followed the Civil War, moderate Republicans took charge of the state, but they became deeply factionalized and lost public support. Florida was a peripheral region that attracted little outside attention. The state was thinly populated, had relatively few freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...