Flamenco Dancing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Flamenco (), in its strictest sense, is an art form based on the various folkloric music traditions of southern

La Emi

is a professional Flamenco dancer and native to New Mexico who performs as well as teaches Flamenco in Santa Fe. She continues studying her art by traveling to Spain to work intensively with Carmela Greco and La Popi, as well as José Galván, Juana Amaya, Yolanda Heredia, Ivan Vargas Heredia, Torombo and Rocio Alcaide Ruiz.

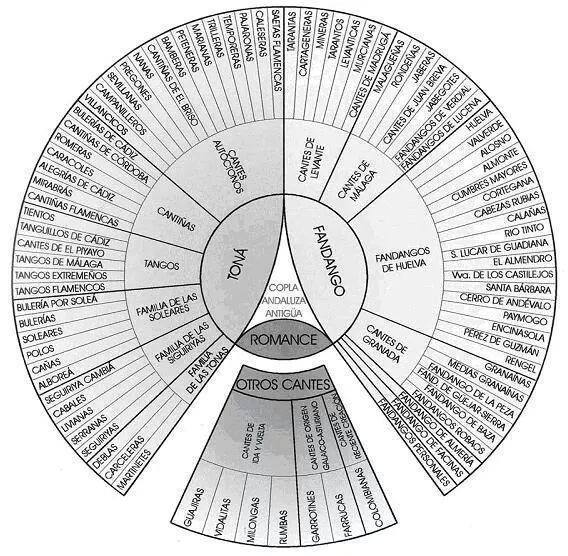

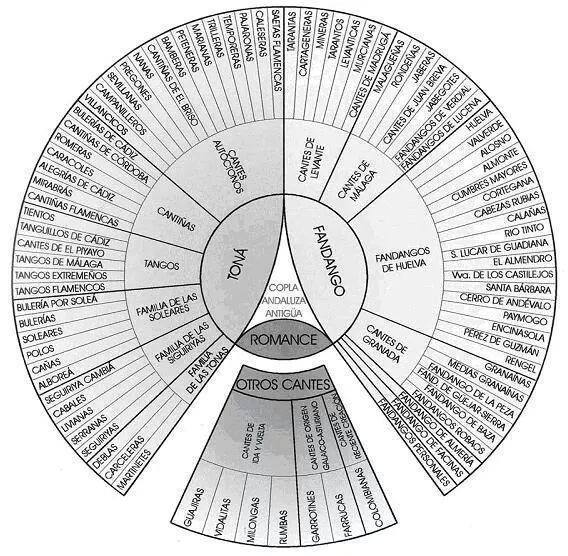

'' Palos'' (formerly known as ''cantes'') are flamenco styles, classified by criteria such as rhythmic pattern,

'' Palos'' (formerly known as ''cantes'') are flamenco styles, classified by criteria such as rhythmic pattern,

zapateado

(Literally "a tap of the foot") and

A typical

A typical

"Flamenco puro" otherwise known as "flamenco por derecho" is considered the form of performance flamenco closest to its gitano influences. In this style, the dance is often performed solo, and is based on signals and calls of structural improvisation rather than choreographed. In the improvisational style, castanets are not often used.

"Classical flamenco" is the style most frequently performed by Spanish flamenco dance companies. It is danced largely in a proud and upright style. For women, the back is often held in a marked back bend. Unlike the more gitano influenced styles, there is little movement of the hips, the body is tightly held and the arms are long, like a ballet dancer. In fact many of the dancers in these companies are trained in Ballet Clásico Español more than in the improvisational language of flamenco. Flamenco has both influenced and been influenced by Ballet Clásico Español, as evidenced by the fusion of the two ballets created by 'La Argentinita' in the early part of the 20th century and later, by Joaquín Cortés, eventually by the entire Ballet Nacional de España et al.

In the 1950s Jose Greco was one of the most famous male flamenco dancers, performing on stage worldwide and on television including the Ed Sullivan Show, and reviving the art almost singlehandedly. Greco's company left a handful of prominent pioneers, most notably: Maria Benitez and Vicente Romero of New Mexico. Today, there are many centers of flamenco art. Albuquerque, New Mexico is considered the "Center of the Nation" for flamenco art. Much of this is due to Maria Benitez's 37 years of sold-out summer seasons. Albuquerque boasts three distinct prominent centers: National Institute of Flamenco, Casa Flamenca and Flamenco Works. Each center dedicates time to daily training, cultural diffusion and world-class performance equaled only to world-class performances one would find in the heart of Southern Spain, Andalucía.

Modern flamenco is a highly technical dance style requiring years of study. The emphasis for both male and female performers is on lightning-fast footwork performed with absolute precision. In addition, the dancer may have to dance while using props such as castanets, canes, shawls and fans.

"New flamenco, Flamenco nuevo" is a recent marketing phenomenon in flamenco. Marketed as a "newer version" of flamenco, its roots came from world-music promoters trying to sell albums of artists who created music that "sounded like" or had Spanish-style influences. Though some of this music was played in similar pitches, scales and was well-received, it has little to nothing to do with the art of flamenco guitar, dance, cante Jondo or the improvisational language. "Nuevo flamenco" consists largely of compositions and repertoire, while traditional flamenco music and dance is a language composed of stanzas, actuated by oral formulaic calls and signals.

"Flamenco puro" otherwise known as "flamenco por derecho" is considered the form of performance flamenco closest to its gitano influences. In this style, the dance is often performed solo, and is based on signals and calls of structural improvisation rather than choreographed. In the improvisational style, castanets are not often used.

"Classical flamenco" is the style most frequently performed by Spanish flamenco dance companies. It is danced largely in a proud and upright style. For women, the back is often held in a marked back bend. Unlike the more gitano influenced styles, there is little movement of the hips, the body is tightly held and the arms are long, like a ballet dancer. In fact many of the dancers in these companies are trained in Ballet Clásico Español more than in the improvisational language of flamenco. Flamenco has both influenced and been influenced by Ballet Clásico Español, as evidenced by the fusion of the two ballets created by 'La Argentinita' in the early part of the 20th century and later, by Joaquín Cortés, eventually by the entire Ballet Nacional de España et al.

In the 1950s Jose Greco was one of the most famous male flamenco dancers, performing on stage worldwide and on television including the Ed Sullivan Show, and reviving the art almost singlehandedly. Greco's company left a handful of prominent pioneers, most notably: Maria Benitez and Vicente Romero of New Mexico. Today, there are many centers of flamenco art. Albuquerque, New Mexico is considered the "Center of the Nation" for flamenco art. Much of this is due to Maria Benitez's 37 years of sold-out summer seasons. Albuquerque boasts three distinct prominent centers: National Institute of Flamenco, Casa Flamenca and Flamenco Works. Each center dedicates time to daily training, cultural diffusion and world-class performance equaled only to world-class performances one would find in the heart of Southern Spain, Andalucía.

Modern flamenco is a highly technical dance style requiring years of study. The emphasis for both male and female performers is on lightning-fast footwork performed with absolute precision. In addition, the dancer may have to dance while using props such as castanets, canes, shawls and fans.

"New flamenco, Flamenco nuevo" is a recent marketing phenomenon in flamenco. Marketed as a "newer version" of flamenco, its roots came from world-music promoters trying to sell albums of artists who created music that "sounded like" or had Spanish-style influences. Though some of this music was played in similar pitches, scales and was well-received, it has little to nothing to do with the art of flamenco guitar, dance, cante Jondo or the improvisational language. "Nuevo flamenco" consists largely of compositions and repertoire, while traditional flamenco music and dance is a language composed of stanzas, actuated by oral formulaic calls and signals.

The flamenco most foreigners are familiar with is a style that was developed as a spectacle for tourists. To add variety, group dances are included and even solos are more likely to be choreographed. The frilly, voluminous spotted dresses are derived from a style of dress worn for the Sevillanas at the annual Seville Fair, Feria in

The flamenco most foreigners are familiar with is a style that was developed as a spectacle for tourists. To add variety, group dances are included and even solos are more likely to be choreographed. The frilly, voluminous spotted dresses are derived from a style of dress worn for the Sevillanas at the annual Seville Fair, Feria in

File:Castelucho.jpg, Claudio Castelucho, flamenco

File:Theatre Flamenco Work Sample.webm, Theatre flamenco work sample

File:Baile andaluz 1893 José Villegas Cordero.jpg, José Villegas Cordero, Baile Andaluz

File:Sargent John Singer Spanish Dancer.jpg, John Singer Sargent, ''Spanish Dancer''

;Scenes of flamenco performance in Seville.

Flamenco en el Palacio Andaluz, Sevilla, España, 2015-12-06, DD 07.JPG

Flamenco en el Palacio Andaluz, Sevilla, España, 2015-12-06, DD 11.JPG

Flamenco en el Palacio Andaluz, Sevilla, España, 2015-12-06, DD 20.JPG

Flamenco en el Palacio Andaluz, Sevilla, España, 2015-12-06, DD 23.JPG

Flamenco guitar studies in official educational centers began in Spain in 1988 at the hands of the great concert performer and teacher from Granada Manuel Cano Tamayo, who obtained a position as emeritus professor at th

Flamenco guitar studies in official educational centers began in Spain in 1988 at the hands of the great concert performer and teacher from Granada Manuel Cano Tamayo, who obtained a position as emeritus professor at th

Superior Conservatory de Música Rafael Orozco

from Córdoba. There are specialized flamenco conservatories throughout the country, although mainly in the Andalusia region, such as the aforementioned Córdoba Conservatory, th

Murcia Superior Music Conservatory

or the Superior Music School of Catalonia, among others. Outside of Spain, a unique case is the Rotterdam Conservatory, in the Netherlands, which offers regulated flamenco guitar studies under the direction of maestro Paco Peña (musician), Paco Peña since 1985, a few years before they existed in Spain.

''Rito y geografía del cante''. Serie documental de los años 70 del siglo XX sobre los orígenes, estilos y pervivencia del cante flamenco

con José María Velázquez-Gaztelu. *

Nuestro flamenco

': programa de Radio Clásica, con José María Velázquez-Gaztelu.

Agencia Andaluza para el Desarrollo del Flamenco

Flamenco Viejo

Flamenco Olímpico

Reportaje Documental

''Flamenco de la A a la Z''

breve enciclopedia del flamenco que incluye diccionario en e

sitio

de Radiolé. * Félix Grande, GRANDE, Félix: ''Memoria del flamenco'', con prólogo de José Manuel Caballero Bonald. Galaxia Gutenberg/Círculo de Lectores, Barcelona, 1991. *

Texto

en ''PDF''.

Flamenco en Sevilla

* Emilio Lafuente Alcántara, LAFUENTE ALCÁNTARA, Emilio (1825–1868): ''Cancionero popular. Colección escogida de seguidillas y coplas'', 1865. ** Vol. II

''Coplas''

texto en Google Books. *

Sobre Emilio Lafuente Alcántara

hermano de Miguel Lafuente Alcántara, en e

sitio

Biblioteca Virtual de Arabistas y Africanistas Españoles.

* Universo Lorca

El Concurso del Cante Jondo de 1922. Web dedicada a la vida y obra de Federico García Lorca y su vinculación con Granada.

(Diputación de Granada) * Los Palos del Flamenco

Los Palos del Flamenco. Artículos sobre el origen y evolución del arte flamenco.

(Flamencos Online)

Flamenco show in Seville

Flamenco, Spanish music Andalusian music Romani dances Spanish dances Spanish folk music European folk dances Articles containing video clips Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity Romani culture Romani music

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, developed within the gitano subculture of the region of Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

, and also having historical presence in Extremadura

Extremadura (; ext, Estremaúra; pt, Estremadura; Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is an autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, it ...

and Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the seventh largest city in the country. It has a population of 460,349 inhabitants in 2021 (about one ...

. In a wider sense, it is a portmanteau

A portmanteau word, or portmanteau (, ) is a blend of wordsRomani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnicities

* Romani people, an ethnic group of Northern Indian origin, living dispersed in Europe, the Americas and Asia

** Romani genocide, under Nazi rule

* Romani language, any of several Indo-Aryan languages of the Roma ...

ethnicity who have contributed significantly to its origination and professionalization. However, its style is uniquely Andalusian and flamenco artists have historically included Spaniards of both gitano and non-gitano heritage.

The oldest record of flamenco music dates to 1774 in the book ''Las Cartas Marruecas'' by José Cadalso

José de Cadalso y Vázquez (Cádiz, 1741 – Gibraltar, 1782), Spanish, Colonel of the Royal Spanish Army, author, poet, playwright and essayist, one of the canonical producers of Spanish Enlightenment literature.

Before completing his twentiet ...

. The development of flamenco over the past two centuries is well documented: "the theatre movement of sainete

A sainete (farce or titbit) was a popular Spanish comic opera piece, a one-act dramatic vignette, with music. It was often placed at the end of entertainments, or between other types of performance. It was vernacular in style, and used scenes of lo ...

s (one-act plays) and tonadilla Tonadilla was a Spanish musical song form of theatrical origin; not danced. The genre was a type of short, satirical musical comedy popular in 18th-century Spain, and later in Cuba and other Spanish colonial countries.

It originated as a song type, ...

s, popular song books and song sheets, customs, studies of dances, and ''toques'', perfection, newspapers, graphic documents in paintings and engravings. ... in continuous evolution together with rhythm, the poetic stanzas, and the ambiance.”

On 16 November 2010, UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

declared flamenco one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity

The Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity was made by the Director-General of UNESCO starting in 2001 to raise awareness of intangible cultural heritage and encourage local communities to protect them and t ...

.

History

It is believed that the flamenco genre emerged at the end of the 18th century in cities and agrarian towns of Baja Andalusia, highlightingJerez de la Frontera

Jerez de la Frontera (), or simply Jerez (), is a Spanish city and municipality in the province of Cádiz in the autonomous community of Andalusia, in southwestern Spain, located midway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Cádiz Mountains. , the ...

as the first written vestige of this art, although there is practically no data related to those dates and the manifestations of this time are more typical of the bolero school than of flamenco. There are hypotheses that point to the influence on flamenco of types of dance from the Indian subcontinent – the place of origin of the Romani people – such as the kathak

Kathak ( hi, कथक; ur, کتھک) is one of the eight major forms of Indian classical dance. It is the classical dance from of Uttar Pradesh. The origin of Kathak is traditionally attributed to the traveling bards in ancient northern Ind ...

dance. There may have been African influence on the rhythms and choreographies of flamenco, as explained in the documentary film ''Gurumbé. Afro-Andalusian Memories ()'', directed by Miguel Ángel Rosales. The musician and anthropologist indicates a possible African origin of the word "fandango", pointing out that in certain Bantu languages

The Bantu languages (English: , Proto-Bantu: *bantʊ̀) are a large family of languages spoken by the Bantu people of Central, Southern, Eastern africa and Southeast Africa. They form the largest branch of the Southern Bantoid languages.

The t ...

, fanda means party, and that the suffix -ngo (as in "Congo" or "Mandinga") is used.

The casticismo

During the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century, a number of factors led to rise in Spain of a phenomenon known as "Costumbrismo Andaluz" or "Andalusian Mannerism". In 1783 Carlos III promulgated a pragmatics that regulated the social situation of theGitanos

The Romani in Spain, generally known by the exonym () or the endonym ''Calé'', belong to the Iberian Cale Romani subgroup, with smaller populations in Portugal (known as ) and in Southern France. Their sense of identity and cohesion stems f ...

. This was a momentous event in the history of Spanish gitanos who, after centuries of marginalization and persecution, saw their legal situation improve substantially.

After the Spanish War of Independence

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain, ...

(1808–1812), a feeling of racial pride developed in the Spanish conscience, in opposition to the "gallified" "Afrancesados" - Spaniards who were influenced by French culture and the idea of the enlightenment. In this context, gitanos were seen as an ideal embodiment of Spanish culture

The culture of ''Spain'' is based on a variety of historical influences, primarily based on the culture of ancient Rome, Spain being a prominent part of the Greco-Roman world for centuries, the very name of Spain comes from the name that the Rom ...

and the emergence of the bullfighting

Bullfighting is a physical contest that involves a bullfighter attempting to subdue, immobilize, or kill a bull, usually according to a set of rules, guidelines, or cultural expectations.

There are several variations, including some forms wh ...

schools of Ronda

Ronda () is a town in the Spanish province of Málaga. It is located about west of the city of Málaga, within the autonomous community of Andalusia. Its population is about 35,000. Ronda is known for its cliff-side location and a deep chasm ...

and Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

, the rise of the Bandidos and Vaqueros led to a taste for Andalusian romantic culture which triumphed in the Madrid court.

At this time there is evidence of disagreements due to the introduction of innovations in art.

Los cafés cantantes

In 1881Silverio Franconetti

Silverio Franconetti y Aguilar, also known simply as Silverio (June 10, 1831 – May 30, 1889) was a singer and the leading figure of the period in flamenco history known as The Golden Age, which was marked by the creation and definition of ...

opened the first flamenco singer café in Seville. In Silverio's café the cantaores were in a very competitive environment, which allowed the emergence of the professional cantaor and served as a crucible where flamenco art was configured. In them Gitanos and non-Gitanos learned the cantes, while reinterpreting the Andalusian folk songs in their own style, expanding the repertoire. Likewise, the taste of the public contributed to configure the flamenco genre, unifying its technique and its theme.

The antiflamenquismo of " La generación del 98"

Flamenco, defined by the Royal Spanish Academy as a "fondness for flamenco art and customs", is a conceptual catch-all where flamenco singing and a fondness for bullfighting, among other traditional Spanish elements, fit. These customs were strongly attacked by the generation of 98, all of its members being "anti-flamenco", with the exception of the Machado brothers, since Manuel and Antonio, being Sevillians and sons of the folklorist Demófilo, had a more complex vision of the matter. The greatest standard bearer of anti-flamenquism was theMadrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

writer Eugenio Noel, who, in his youth, had been a militant casticista. Noel attributed to flamenco and bullfighting the origin of the ills of Spain which he saw as manifestations of the country's Oriental

The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of ''Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the ...

character which hindered economic and social development. These considerations caused an insurmountable rift to be established for decades between flamenco and most "intellectuals" of the time.

The flamenca opera

Between 1920 and 1955, flamenco shows began to be held in bullrings and theaters, under the name "flamenco opera". This denomination was an economic strategy of the promoters, since opera only paid 3% while variety shows paid 10%. At this time, flamenco shows spread throughout Spain and the main cities of the world. The great social and commercial success achieved by flamenco at this time eliminated some of the oldest and most sober styles from the stage, in favor of lighter airs, such ascantiñas

The ''cantiñas'' () is a group of flamenco ''palos'' (musical forms), originated in the area of Cádiz in Andalusia (although some styles of cantiña have developed in the province of Seville). They share the same '' compás'' or rhythmic pattern ...

, los cantes de ida y vuelta Cantes de ida y vuelta () is a Spanish expression literally meaning roundtrip songs. It refers to a group of flamenco musical forms or palos with diverse musical features, which "travelled back" from Latin America (mainly Cuba) as styles that, havi ...

and fandango

Fandango is a lively partner dance originating from Portugal and Spain, usually in triple meter, traditionally accompanied by guitars, castanets, or hand-clapping. Fandango can both be sung and danced. Sung fandango is usually bipartite: it has ...

s, of which many personal versions were created. The purist critics attacked this lightness of the cantes, as well as the use of falsete and the gaitero style.

In the line of purism, the poet Federico García Lorca

Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca (5 June 1898 – 19 August 1936), known as Federico García Lorca ( ), was a Spanish poet, playwright, and theatre director. García Lorca achieved international recognition as an emblemat ...

and the composer Manuel de Falla

Manuel de Falla y Matheu (, 23 November 187614 November 1946) was an Andalusian Spanish composer and pianist. Along with Isaac Albéniz, Francisco Tárrega, and Enrique Granados, he was one of Spain's most important musicians of the first hal ...

had the idea of concurso de cante jondo en Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

en 1922. Both artists conceived of flamenco as folklore, not as a scenic artistic genre; for this reason, they were concerned, since they believed that the massive triumph of flamenco would end its purest and deepest roots. To remedy this, they organized a cante jondo contest in which only amateurs could participate and in which festive cantes (such as cantiñas) were excluded, which Falla and Lorca did not consider jondos, but flamencos. The jury was chaired by Antonio Chacón, who at that time was the leading figure in cante. The winners were "El Tenazas", a retired professional cantaor from Morón de la Frontera, and Manuel Ortega, an eight-year-old boy from Seville who would go down in flamenco history as Manolo Caracol. The contest turned out to be a failure due to the scant echo it had and because Lorca and Falla did not know how to understand the professional character that flamenco already had at that time, striving in vain to seek a purity that never existed in an art that was characterized by mixture and the personal innovation of its creators. Apart from this failure, with the Generation of '27

The Generation of '27 ( es, Generación del 27) was an influential group of poets that arose in Spanish literary circles between 1923 and 1927, essentially out of a shared desire to experience and work with avant-garde forms of art and poetry. ...

, whose most eminent members were Andalusians and therefore knew the genre first-hand, the recognition of flamenco by intellectuals began.

At that time, there were already flamenco recordings related to Christmas, which can be divided into two groups: the traditional flamenco carol and flamenco songs that adapt their lyrics to the Christmas theme. These cantes have been maintained to this day, the Zambomba Jerezana being spatially representative, declared an Asset of Intangible Cultural Interest by the Junta de Andalucía in December 2015.

During the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

, a large number of singers were exiled or died defending the Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

and the humiliations to which they were being subjected by the National Party: Bando Nacional: Corruco de Algeciras, Chaconcito, El Carbonerillo, El Chato De Las Ventas, Vallejito, Rita la Cantaora

Rita Giménez García, most commonly known as ''Rita la Cantaora'' (1859 in Jerez de la Frontera, Cádiz – 1937 in Zorita del Maestrazgo, Castellón), was one of the most famous Spanish singers of flamenco in her time due to her performances ...

, Angelillo, Guerrita are some of them. In the postwar period and the first years of the Franco regime

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

, the world of flamenco was viewed with suspicion, as the authorities were not clear that this genre contributed to the national conscience. However, the regime soon ended up adopting flamenco as one of the quintessential Spanish cultural manifestations. The singers who have survived the war go from stars to almost outcasts, singing for the young men in the private rooms of the brothels in the center of Seville where they have to adapt to the whims of aristocrats, soldiers and businessmen who have become rich.

In short, the period of the flamenco opera was a time open to creativity and that definitely made up most of the flamenco repertoire. It was the Golden Age of this genre, with figures such as Antonio Chacón

Antonio Chacón (1869–1929) was a Spanish flamenco singer antaor

Chacón was born in Jerez de la Frontera, Cádiz Province. He began earning a living by performing flamenco around 1884. He toured Andalucia with his two friends, the Molin ...

, Manuel Vallejo , Manuel Torre, La Niña de los Peines

Pastora Pavón Cruz, known as La Niña de los Peines (10 February 1890 – 26 November 1969), is considered the most important woman flamenco singer of the 20th century. She was a sister of singers Arturo Pavón and Tomás Pavón, also an importan ...

, Pepe Marchena

José Tejada Marín (November 7, 1903 – December 4, 1976), known as Pepe Marchena and also as Niño de Marchena in the first years of his career, was a Spanish flamenco singer who achieved great success in the ópera flamenca period (1922–19 ...

and Manolo Caracol

Manuel Ortega Juárez (9 July 1909 – 24 February 1973) was a Spanish flamenco cantaor (singer).

Life and family

Born in Seville, Spain, he was descended from a long line of flamenco artists including Enrique Ortega (father and son) and Cur ...

.

Flamencología

Starting in the 1950s, abundant anthropological and musicological studies on flamenco began to be published. In 1954 Hispavox published the first Antología del Cante Flamenco, a sound recording that was a great shock to its time, dominated by orchestrated cante and, consequently, mystified. In 1955, the Argentine intellectual Anselmo González Climent published an essay called "Flamencología", whose title he baptized the "set of knowledge, techniques, etc., on flamenco singing and dancing." This book dignified the study of flamenco by applying the academic methodology of musicology to it and served as the basis for subsequent studies on this genre. As a result, in 1956 the National Contest of Cante Jondo de Córdoba was organized and in 1958 the first flamencology chair was founded in Jerez de la Frontera, the oldest academic institution dedicated to the study, research, conservation, promotion and defense of the flamenco art. Likewise, in 1963 the Cordovan poet Ricardo Molina and the Sevillian cantaorAntonio Mairena

Antonio Cruz García, known as Antonio Mairena (1909–1983), was a Spanish musician, who tried to rescue a type of flamenco, which he considered to be pure or authentic. He rescued or recreated a high number of songs that had been almost lost ...

published Alalimón Mundo y Formas del Cante flamenco

The cante flamenco (), meaning "flamenco singing", is one of the three main components of flamenco, along with ''toque'' (playing the guitar) and ''baile'' (dance). Because the dancer is front and center in a flamenco performance, foreigners ofte ...

, which has become a must-have reference work.

For a long time the Mairenistas postulates were considered practically unquestionable, until they found an answer in other authors who elaborated the "Andalusian thesis", which defended that flamenco was a genuinely Andalusian product, since it had been developed entirely in this region and because its styles basic ones derived from the folklore of Andalusia. They also maintained that the Andalusian Gitanos had contributed decisively to their formation, highlighting the exceptional nature of flamenco among gypsy music and dances from other parts of Spain and Europe. The unification of the Gitanos and Andalusian thesis has ended up being the most accepted today. In short, between the 1950s and 1970s, flamenco went from being a mere show to also becoming an object of study.

Flamenco protest during the Franco regime

Flamenco became one of the symbols of Spanish national identity during theFranco regime

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

, since the regime knew how to appropriate a folklore traditionally associated with Andalusia to promote national unity and attract tourism, constituting what was called national-flamenquismo. Hence, flamenco had long been seen as a reactionary or retrograde element. In the mid-60s and until the transition, cantaores who opposed the regime began to appear with the use of protest lyrics. These include: José Menese and lyricist Francisco Moreno Galván, Enrique Morente

Enrique Morente Cotelo (25 December 1942 – 13 December 2010), known as Enrique Morente, was a flamenco singer (in Spanish, cantaor) and a celebrated figure within the world of contemporary flamenco. After his orthodox beginnings, he plunged in ...

, Manuel Gerena, El Lebrijano

Juan Peña Fernández (8 August 1941 – 13 July 2016), also known as Juan Peña "El Lebrijano" or simply El Lebrijano, was a Spanish Gitano (''Roma'') flamenco musician. As a flamenco-fusion musician he studied the musical relation and fusion of ...

, El Cabrero

El Cabrero is a neighborhood of Cartagena de Indias ( Colombia). It's situated in front of the Caribbean Sea, and in the other side, El Cabrero lagoon. On the southwest borders the walled Old City, specifically the defenses of San Lucas and Sant ...

, Lole y Manuel

Lole y Manuel was a gitano (Spanish Romani) musical duo formed by Dolores Montoya Rodríguez (1954) and Manuel Molina Jiménez (1948-2015). They composed and performed innovative flamenco music between 1972 and 1993.

This couple was the first ex ...

, el Piki or Luis Marín, among many others.

In contrast to this conservatism with which it was associated during the Franco regime, flamenco suffered the influence of the wave of activism that also shook the university against the repression of the regime when university students came into contact with this art in the recitals that were held, for example, at the Colegio Mayor de San Juan Evangelista: "flamenco amateurs and professionals got involved with performances of a manifestly political nature. It was a kind of flamenco protest charged with protest, which meant censorship and repression for the flamenco activists ".

As the political transition progressed, the demands were deflated as flamenco inserted itself within the flows of globalized art. At the same time, this art was institutionalized until it reached the point that the Junta de Andalucía

The Regional Government of Andalusia ( es, Junta de Andalucía) is the government of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia. It consists of the Parliament, the President of the Regional Government and the Government Council. The 2011 budget was 31. ...

was attributed in 2007 "exclusive competence in matters of knowledge, conservation, research, training, promotion and dissemination".

Flamenco fusion

In the 1970s, there were airs of social and political change in Spain, and Spanish society was already quite influenced by various musical styles from the rest of Europe and the United States. There were also numerous singers who had grown up listening toAntonio Mairena

Antonio Cruz García, known as Antonio Mairena (1909–1983), was a Spanish musician, who tried to rescue a type of flamenco, which he considered to be pure or authentic. He rescued or recreated a high number of songs that had been almost lost ...

, Pepe Marchena

José Tejada Marín (November 7, 1903 – December 4, 1976), known as Pepe Marchena and also as Niño de Marchena in the first years of his career, was a Spanish flamenco singer who achieved great success in the ópera flamenca period (1922–19 ...

and Manolo Caracol

Manuel Ortega Juárez (9 July 1909 – 24 February 1973) was a Spanish flamenco cantaor (singer).

Life and family

Born in Seville, Spain, he was descended from a long line of flamenco artists including Enrique Ortega (father and son) and Cur ...

. The combination of both factors led to a revolutionary period called flamenco fusion. , Seville Flamenco Dance Museum 2014.

The singer Rocío Jurado

María del Rocío Mohedano Jurado (, 18 September 1944 – 1 June 2006), better known as Rocío Jurado, was a Spanish singer and actress. She was born in Chipiona (Cádiz) and nicknamed "La más grande" ("The Greatest").

In 2000 in New York Ci ...

internationalized flamenco at the beginning of the 70s, replacing the bata de cola with evening dresses. Her facet in the "Fandangos de Huelva" and in the Alegrías was recognized internationally for her perfect voice tessitura in these genres. She used to be accompanied in her concerts by guitarists Enrique de Melchor and Tomatito

José Fernández Torres, known as Tomatito (born Fondón, 1958), is a Spanish roma flamenco guitarist and composer. Having started his career accompanying famed flamenco singer Camarón de la Isla (with Paco de Lucía), he has made a number of ...

, not only at the national level but in countries like Colombia, Venezuela and Puerto Rico.

The musical representative José Antonio Pulpón was a decisive character in that fusion, as he urged the cantaor Agujetas to collaborate with the Sevillian Andalusian rock group "Pata Negra

Pata Negra is a Spanish flamenco-blues band, established by brothers Raimundo Amador (singer and guitarist, b. 1959 in Seville) and Rafael Amador

Rafael Amador Flores (16 November 1959 – 31 July 2018) was a Mexican professional football ...

", the most revolutionary couple since Antonio Chacón and Ramón Montoya Ramón Montoya (November 2, 1879, Madrid, Spain – July 20, 1949, Madrid, Spain), Flamenco guitarist and composer.

Born into a family of Gitano (Romani) cattle traders, Ramón Montoya used earnings from working in the trade to purchase his first g ...

, initiating a new path for flamenco. It also fostered the artistic union between the virtuoso guitarist from Algeciras Paco de Lucía

Francisco Sánchez Gómez (21 December 194725 February 2014), known as Paco de Lucía (;), was a Spanish virtuoso flamenco guitarist, composer, and record producer. A leading proponent of the new flamenco style, he was one of the first flame ...

and the long-standing singer from the island Camarón de la Isla

José Monje Cruz (5 December 1950 – 2 July 1992), better known by his stage name Camarón de la Isla (), was a Spanish Romani flamenco singer. Considered one of the all-time greatest flamenco singers, he was noted for his collaborations ...

, who gave a creative impulse to flamenco that would mean its definitive break with Mairena's conservatism. When both artists undertook their solo careers, Camarón became a mythical cantaor for his art and personality, with a legion of followers, while Paco de Lucía reconfigured the entire musical world of flamenco, opening up to new influences, such as Brazilian music, Arabic and jazz and introducing new musical instruments such as the Peruvian cajon, the transverse flute, etc.

Other leading performers in this process of formal flamenco renewal were Juan Peña El Lebrijano, who married flamenco with Andalusian music, and Enrique Morente

Enrique Morente Cotelo (25 December 1942 – 13 December 2010), known as Enrique Morente, was a flamenco singer (in Spanish, cantaor) and a celebrated figure within the world of contemporary flamenco. After his orthodox beginnings, he plunged in ...

, who throughout his long artistic career has oscillated between the purism of his first recordings and the crossbreeding with rock, or Remedios Amaya

María Dolores Amaya Vega (born 1962 in Seville), better known by her stage name Remedios Amaya (), is a Spanish flamenco singer. She represented Spain at the 1983 Eurovision Song Contest. Remedios Amaya has been popular with international audi ...

from Triana, cultivator of a unique style of tangos

Tangos may refer to:

* "Tangos" (song), a song popularized in Spain

* Tangos (district), a district or barangay in Navotas, Philippines

* ''Tangos'' (album), a 1973 album by Buenos Aires 8

* ''Tangos'' (Rubén Blades album), a 2014 album by Ru ...

from Extremadura, and a wedge of purity in her cante make her part of this select group of established artists. Other singers with their own style include Cancanilla de Marbella

Cancanilla de Marbella (or Cancanilla de Málaga) is the artistic name of the gypsy singer and dancer Sebastián Heredia Santiago, born in Marbella, Spain, in 1951, and resident in Madrid.

Career

He comes from a family of flamenco roots. He is s ...

. In 2011 this style became known in India thanks to María del Mar Fernández

María del Mar Fernández (born 1 October 1978 in Cádiz) is a Spanish flamenco singer best known for her rendering of the song " Señorita" from the 2011 Hindi film ''Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara''.

Career

María began her career as a singer at th ...

, who acts in the video clip of the film You Live Once, entitled Señorita. The film was seen by more than 73 million viewers.

New flamenco

In the 1980s a new generation of flamenco artists emerged who had been influenced by the mythical cantaor Camarón, Paco de Lucía, Morente, etc. These artists were interested in popular urban music, which in those years was renewing the Spanish music scene, it was the time of the Movida madrileña. Among them are "Pata Negra

Pata Negra is a Spanish flamenco-blues band, established by brothers Raimundo Amador (singer and guitarist, b. 1959 in Seville) and Rafael Amador

Rafael Amador Flores (16 November 1959 – 31 July 2018) was a Mexican professional football ...

", who fused flamenco with blues and rock, Ketama

Ketama is a Spanish musical group in the new flamenco tradition. Fusing flamenco with other musical forms (salsa, Brazilian music, reggae, funk, jazz), they created a style that lies somewhere between flamenco and pop salsa. Their music drew as ...

, of pop and Cuban inspiration and Ray Heredia, creator of his own musical universe where flamenco occupies a central place.

Also the recording company Nuevos Medios released many musicians under the label nuevo flamenco and this denomination has grouped musicians very different from each other like Rosario Flores

Rosario del Carmen González Flores better known as Rosario Flores (; born 4 November 1963) is a two-time Latin Grammy Award-winning Spanish singer.

She was born in Madrid, Spain, as the daughter of Antonio González ('El Pescaílla') and famou ...

, daughter of Lola Flores

Lola may refer to:

Places

* Lolá, a or subdistrict of Panama

* Lola Township, Cherokee County, Kansas, United States

* Lola Prefecture, Guinea

* Lola, Guinea, a town in Lola Prefecture

* Lola Island, in the Solomon Islands

People

* Lola (fo ...

, or the renowned singer Malú

María Lucía Sánchez Benítez, known as Malú, is a Spanish singer.

She is the niece of the composer and guitarist Paco de Lucía, and is known for songs such as "Aprendiz", "Como Una Flor", "Toda", "Diles", "Si Estoy Loca" and "No Voy a Cambia ...

, niece of Paco de Lucía and daughter of Pepe de Lucía, who despite sympathizing with flamenco and keeping it in her discography has continued with her personal style. However, the fact that many of the interpreters of this new music are also renowned cantaores, in the case of José Mercé

José Mercé (born José Soto Soto in 1955 in Jerez de la Frontera) is a Spanish flamenco singer. As a 12-year-old he performed at flamenco festivals. Later he moved to Madrid where he recorded his first album in 1968. Family

He is the great- ...

, El Cigala, and others, has led to labeling everything they perform as flamenco, although the genre of their songs differs quite a bit from the classic flamenco. This has generated very different feelings, both for and against.

Other contemporary artists of that moment were O'Funkillo and Ojos de Brujo

Ojos de Brujo was a nine-piece band from Barcelona who described their style as "jipjop flamenkillo" ( hip hop with a little flamenco). The band sold over 100,000 copies of their self-produced ''Barí'' album and received several awards, among t ...

, Arcángel, Miguel Poveda

Miguel Ángel Poveda León (born 13 February 1973) is a Spanish flamenco singer known by his stage name Miguel Poveda.

Biography

Born in Barcelona, Spain, his father is from Lorca in Murcia and his mother from Puertollano ( Castilla-La Mancha ...

, Mayte Martín

Mayte Martín (born in Barcelona, Spain, April 19, 1965) is a Flamenco cantaora (singer), bolero singer, and composer. She is widely recognized as one of the most important flamenco voices of her generation. She has also devoted part of her care ...

, Marina Heredia, Estrella Morente

Estrella Morente (Estrella de la Aurora Morente Carbonell) is a Spanish flamenco singer. She was born on 14 August 1980 in Las Gabias, Granada in southern Spain. She is the daughter of flamenco singer Enrique Morente and dancer Aurora Carbonell. ...

or Manuel Lombo, etc.

But the discussion between the difference of flamenco and new flamenco

New flamenco (or ''nuevo flamenco'') or flamenco fusion is a musical genre that was born in Spain, starting in the 1980s. It combines flamenco guitar virtuosity and traditional flamenco music with musical fusion (with genres like jazz, blues, roc ...

in Spain has just gained strength during since 2019 due to the success of new flamenco attracting the taste of the youngest Spanish fans but also in the international musical scene emphasizing the problem of how should we call this new musical genre mixed with flamenco.

One of these artist who has reinvented flamenco is Rosalía

Rosalia Vila Tobella (born 25 September 1992), known mononymously as Rosalía (, ), is a Spanish singer. Born and raised in the outskirts of Barcelona, she has been described as an "atypical pop star" due to her genre-bending musical styles. ...

, an indisputable name on the international music scene. "Pienso en tu mirá", "Di mi nombre" or the song that catapulted her to fame, "Malamente", are a combination of styles that includes a flamenco/south Spain traditional musical base. Rosalía has broken the limits of this musical genre by embracing other urban rhythms, but has also created a lot of controversy about which genre is she using. The Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

artist has been awarded several Latin Grammy

The Latin Grammy Awards are an award by The Latin Recording Academy to recognize outstanding achievement in the Latin music industry. The Latin Grammy honors works recorded in Spanish or Portuguese from anywhere around the world that has been r ...

Awards and MTV Video Music Awards

The MTV Video Music Awards (commonly abbreviated as the VMAs) is an award show presented by the cable channel MTV to honour the best in the music video medium. Originally conceived as an alternative to the Grammy Awards (in the video category) ...

, which also, at just 26 years old, garners more than 12 million monthly listeners on Spotify

Spotify (; ) is a proprietary Swedish audio streaming and media services provider founded on 23 April 2006 by Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon. It is one of the largest music streaming service providers, with over 456 million monthly active us ...

.

But it is not the only successful case, the Granada-born Dellafuente, C. Tangana

Antón Álvarez Alfaro (born July 16, 1990), known professionally as C. Tangana, is a Spanish rapper and songwriter. He began his musical career while in high school, rapping under the pseudonym Crema and releasing a seven-track EP titled ''Él ...

, MAKA, RVFV, Demarco Flamenco, Maria Àrnal and Marcel Bagés, El Niño de Elche, Sílvia Pérez Cruz

Sílvia Pérez Cruz (born 15 February 1983) is a Spanish singer. In 2012, she recorded her first solo album, ''11 de Novembre'', which was nominated for album of the year in both Spain and France. A song performed by her, "No Te Puedo Encontrar" ...

; Califato 3/4, Juanito Makandé, Soledad Morente, María José Llergo

María José Llergo (born 1994) is a Spanish singer.

Biography

Born in Pozoblanco, in 1994, she joined the local violin school at a young age. She also stood out in the choir of the . Owing to being granted a musical scholarship, she moved to B ...

o Fuel Fandango are only a few of the new spanish musical scene that includes flamenco in their music.

It seems that the Spanish music scene is experiencing a change in its music and new rhythms are re-emerging together with new artists who are experimenting to cover a wider audience that wants to maintain the closeness that flamenco has transmitted for decades.

Flamenco Culture Overseas

The state of New Mexico, located in the southwest of the United States maintains a strong identity with Flamenco culture. TheUniversity of New Mexico

The University of New Mexico (UNM; es, Universidad de Nuevo México) is a public research university in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Founded in 1889, it is the state's flagship academic institution and the largest by enrollment, with over 25,400 ...

located in Albuquerque

Albuquerque ( ; ), ; kee, Arawageeki; tow, Vakêêke; zun, Alo:ke:k'ya; apj, Gołgéeki'yé. abbreviated ABQ, is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Mexico. Its nicknames, The Duke City and Burque, both reference its founding in ...

offers a graduate degree program in Flamenco. Flamenco performances are widespread in the Albuquerque and Santa Fe communities, with the National institute of Flamenco sponsoring an annual festival, as well as a variety of professional flamenco performacess offere at various locales. Emmy Grimm, known by her stage namLa Emi

is a professional Flamenco dancer and native to New Mexico who performs as well as teaches Flamenco in Santa Fe. She continues studying her art by traveling to Spain to work intensively with Carmela Greco and La Popi, as well as José Galván, Juana Amaya, Yolanda Heredia, Ivan Vargas Heredia, Torombo and Rocio Alcaide Ruiz.

''Main Palos''

'' Palos'' (formerly known as ''cantes'') are flamenco styles, classified by criteria such as rhythmic pattern,

'' Palos'' (formerly known as ''cantes'') are flamenco styles, classified by criteria such as rhythmic pattern, mode

Mode ( la, modus meaning "manner, tune, measure, due measure, rhythm, melody") may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* '' MO''D''E (magazine)'', a defunct U.S. women's fashion magazine

* ''Mode'' magazine, a fictional fashion magazine which is ...

, chord progression

In a musical composition, a chord progression or harmonic progression (informally chord changes, used as a plural) is a succession of chords. Chord progressions are the foundation of harmony in Western musical tradition from the common practice ...

, stanza

In poetry, a stanza (; from Italian language, Italian ''stanza'' , "room") is a group of lines within a poem, usually set off from others by a blank line or Indentation (typesetting), indentation. Stanzas can have regular rhyme scheme, rhyme and ...

ic form and geographic origin. There are over 50 different ''palos'', some are sung unaccompanied while others have guitar or other accompaniment. Some forms are danced while others are not. Some are reserved for men and others for women while some may be performed by either, though these traditional distinctions are breaking down: the ''Farruca'', for example, once a male dance, is now commonly performed by women too.

There are many ways to categorize ''Palos'' but they traditionally fall into three classes: the most serious is known as ''cante jondo

''Cante jondo'' (Andalusian ) is a vocal style in flamenco, an unspoiled form of Andalusian folk music. The name means "deep song" in Spanish, with ''hondo'' ("deep") spelled with J () as a form of eye dialect, because traditional Andalusian pro ...

'' (or '' cante grande''), while lighter, frivolous forms are called ''Cante Chico

The cante flamenco (), meaning "flamenco singing", is one of the three main components of flamenco, along with ''toque'' (playing the guitar) and ''baile'' (dance). Because the dancer is front and center in a flamenco performance, foreigners ofte ...

''. Forms that do not fit either category are classed as ''Cante Intermedio

The cante flamenco (), meaning "flamenco singing", is one of the three main components of flamenco, along with ''toque'' (playing the guitar) and ''baile'' (dance). Because the dancer is front and center in a flamenco performance, foreigners ofte ...

'' . These are the best known ''palos'' (; ):

Alegrías

''Alegrías'' () is a flamenco palo or musical form, which has a rhythm consisting of 12 beats. It is similar to Soleares. Its beat emphasis is as follows: 1 2 '' 4 5 '' 7 '' 9 0'' 11 2''. Alegrías originated in Cádiz. Alegrías belongs to ...

The alegrías are thought to derive from the Aragonese jota, which took root in Cadiz during the Peninsular war

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

and the establishment of the Cortes de Cadiz. That is why its classic lyrics contain so many references to the Virgen del Pilar, the Ebro River and Navarra.

Enrique Butrón is considered to have formalized the current flamenco style of alegrías and Ignacio Espeleta who introduced the characteristic "tiriti, tran, tran...". Some of the best known interpreters of alegrías are Enrique el Mellizo, Chato de la Isla, Pinini, Pericón de Cádiz, Aurelio Sellés, La Perla de Cádiz, Chano Lobato and El Folli.

One of the structurally strictest forms of flamenco, a traditional dance in alegrías must contain each of the following sections: a salida (entrance), paseo (walkaround), silencio (similar to an adagio in ballet), castellana (upbeat sectionzapateado

(Literally "a tap of the foot") and

bulerías

''Bulería'' (; interchangeable with the plural, ''bulerías'') is a fast flamenco rhythm made up of a 12 beat cycle with emphasis in two general forms as follows:

This may be thought of as a measure of followed by a measure of (known ...

. This structure though, is not followed when alegrías are sung as a standalone song (with no dancing). In that case, the stanzas are combined freely, sometimes together with other types of cantiñas

The ''cantiñas'' () is a group of flamenco ''palos'' (musical forms), originated in the area of Cádiz in Andalusia (although some styles of cantiña have developed in the province of Seville). They share the same '' compás'' or rhythmic pattern ...

.

Alegrías has a rhythm consisting of 12 beats. It is similar to Soleares. Its beat emphasis is as follows: 1 2 '' 4 5 '' 7 '' 9 0'' 11 2''. Alegrías originated in Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

. Alegrías belongs to the group of ''palos'' called Cantiñas

The ''cantiñas'' () is a group of flamenco ''palos'' (musical forms), originated in the area of Cádiz in Andalusia (although some styles of cantiña have developed in the province of Seville). They share the same '' compás'' or rhythmic pattern ...

and it is usually played in a lively rhythm (120-170 beats per minute). The livelier speeds are chosen for dancing, while quieter rhythms are preferred for the song alone.

Bulerías

''Bulería'' (; interchangeable with the plural, ''bulerías'') is a fast flamenco rhythm made up of a 12 beat cycle with emphasis in two general forms as follows:

This may be thought of as a measure of followed by a measure of (known ...

Bulerías a fast flamenco rhythm made up of a 12 beat cycle with emphasis in two general forms as follows: 2'' 1 2 '' 4 5 '' 7 '' 9 0'' 11 or 2'' 1 2 '' 4 5 6 '' '' 9 0'' 11. It originated among the Calé Romani people of Jerez

Jerez de la Frontera (), or simply Jerez (), is a Spanish city and municipality in the province of Cádiz in the autonomous community of Andalusia, in southwestern Spain, located midway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Cádiz Mountains. , the c ...

during the 19th century, originally as a fast, upbeat ending to '' soleares'' or '' alegrias''. It is among the most popular and dramatic of the flamenco forms and often ends any flamenco gathering, often accompanied by vigorous dancing and tapping.

Fandango

Fandango is a lively partner dance originating from Portugal and Spain, usually in triple meter, traditionally accompanied by guitars, castanets, or hand-clapping. Fandango can both be sung and danced. Sung fandango is usually bipartite: it has ...

Granaína Granaína () is a flamenco style of singing and guitar playing from Granada. It is a variant of the Granada fandangos. It was originally danceable, but now has lost its rhythm, is much slower, and is usually only sung or played as a guitar solo, r ...

s

Guajiras

Guajira is a music genre derived from the punto cubano. According to some specialists, the punto cubano was known in Spain since the 18th century, where it was called "punto de La Habana", and by the second half of the 19th century it was adopt ...

Peteneras The Petenera is a flamenco palo in a 12-beat metre, with strong beats distributed as follows: 2'' 2] '' 5] '' '' '' '' 0'' 1 It is therefore identical with the 16th century Spanish dances zarabanda and the jácara.

The lyrics are in 4-line stan ...

Soleá

''Soleares'' (plural of ''soleá'', ) is one of the most basic forms or '' palos'' of Flamenco music, probably originating among the Calé Romani people of Cádiz or Seville in Andalusia, the most southern region of Spain. It is usually accompa ...

Tangos

Tangos may refer to:

* "Tangos" (song), a song popularized in Spain

* Tangos (district), a district or barangay in Navotas, Philippines

* ''Tangos'' (album), a 1973 album by Buenos Aires 8

* ''Tangos'' (Rubén Blades album), a 2014 album by Ru ...

Tanguillos

Tarantos

Tientos

''Tiento'' (, pt, Tento ) is a musical genre originating in Spain in the mid-15th century. It is formally analogous to the fantasia (fantasy), found in England, Germany, and the Low Countries, and also the ricercare, first found in Italy. By t ...

Music

Structure

A typical flamenco recital with voice and guitar accompaniment comprises a series of pieces (not exactly "songs") in different palos. Each song is a set of verses (called ''copla'', ''tercio'', or ''letras''), punctuated by guitar interludes (''falseta {{for, the male singing voice, Falsetto

A Falseta is part of Flamenco music. They are usually short melodies played by the guitarist(s) in between sung verses, or to accompany dancers. In a guitar solo, the artists play already created falsetas or i ...

s''). The guitarist also provides a short introduction setting the tonality, ''compás'' (see below) and tempo of the cante . In some palos, these falsetas are played with a specific structure too; for example, the typical sevillanas

''Sevillanas'' () are a type of folk music and dance of Sevilla and its region. They were derived from the Seguidilla, an old Castilian folk music and dance genre. In the nineteenth century they were influenced by Flamenco. They have a relat ...

is played in an AAB pattern, where A and B are the same falseta with only a slight difference in the ending .

Harmony

Flamenco uses the flamenco mode (which can also be described as the modern Phrygian mode (''modo frigio''), or a harmonic version of that scale with a major 3rddegree

Degree may refer to:

As a unit of measurement

* Degree (angle), a unit of angle measurement

** Degree of geographical latitude

** Degree of geographical longitude

* Degree symbol (°), a notation used in science, engineering, and mathematics

...

), in addition to the major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

and minor

Minor may refer to:

* Minor (law), a person under the age of certain legal activities.

** A person who has not reached the age of majority

* Academic minor, a secondary field of study in undergraduate education

Music theory

*Minor chord

** Barb ...

scales commonly used in modern Western music. The Phrygian mode occurs in ''palos'' such as soleá

''Soleares'' (plural of ''soleá'', ) is one of the most basic forms or '' palos'' of Flamenco music, probably originating among the Calé Romani people of Cádiz or Seville in Andalusia, the most southern region of Spain. It is usually accompa ...

, most bulerías

''Bulería'' (; interchangeable with the plural, ''bulerías'') is a fast flamenco rhythm made up of a 12 beat cycle with emphasis in two general forms as follows:

This may be thought of as a measure of followed by a measure of (known ...

, siguiriya

''Siguiriyas'' (; also ''seguiriyas'',

''siguerillas'', ''siguirillas'', ''seguidilla gitana'', etc.) are a form of flamenco music in the cante jondo category. This deep, expressive style is among the most important in flamenco. Unlike other pal ...

s, tangos

Tangos may refer to:

* "Tangos" (song), a song popularized in Spain

* Tangos (district), a district or barangay in Navotas, Philippines

* ''Tangos'' (album), a 1973 album by Buenos Aires 8

* ''Tangos'' (Rubén Blades album), a 2014 album by Ru ...

and tientos

''Tiento'' (, pt, Tento ) is a musical genre originating in Spain in the mid-15th century. It is formally analogous to the fantasia (fantasy), found in England, Germany, and the Low Countries, and also the ricercare, first found in Italy. By t ...

.

chord sequence

In a musical composition, a chord progression or harmonic progression (informally chord changes, used as a plural) is a succession of chords. Chord progressions are the foundation of harmony in Western musical tradition from the common practic ...

, usually called the "Andalusian cadence

The Andalusian cadence (diatonic phrygian tetrachord) is a term adopted from flamenco music for a chord progression comprising four chords descending stepwise – a iv–III–II–I progression with respect to the Phrygian mode or i–VII–VI� ...

" may be viewed as in a modified Phrygian: in E the sequence is Am–G–F–E . According to Manolo Sanlúcar

Manolo Sanlúcar (born Manuel Muñoz Alcón, 24 November 1943 – 27 August 2022) was a Spanish flamenco composer and guitarist. He was considered one of the most important Spanish composers of recent times, and together with Paco de Lucía, T ...

E is here the tonic, F has the harmonic function

In mathematics, mathematical physics and the theory of stochastic processes, a harmonic function is a twice continuously differentiable function f: U \to \mathbb R, where is an open subset of that satisfies Laplace's equation, that is,

: \f ...

of dominant while Am and G assume the functions of subdominant

In music, the subdominant is the fourth tonal degree () of the diatonic scale. It is so called because it is the same distance ''below'' the tonic as the dominant is ''above'' the tonicin other words, the tonic is the dominant of the subdomina ...

and mediant In music, the mediant (''Latin'': to be in the middle) is the third scale degree () of a diatonic scale, being the note halfway between the tonic and the dominant.Benward & Saker (2003), p.32. In the movable do solfège system, the mediant note i ...

respectively .

Guitarists tend to use only two basic inversions or "chord shapes" for the tonic chord (music)

A chord, in music, is any harmonic set of pitches/frequencies consisting of multiple notes (also called "pitches") that are heard as if sounding simultaneously. For many practical and theoretical purposes, arpeggios and broken chords (in whic ...

, the open 1st inversion E and the open 3rd inversion A, though they often transpose

In linear algebra, the transpose of a matrix is an operator which flips a matrix over its diagonal;

that is, it switches the row and column indices of the matrix by producing another matrix, often denoted by (among other notations).

The tr ...

these by using a capo. Modern guitarists such as Ramón Montoya Ramón Montoya (November 2, 1879, Madrid, Spain – July 20, 1949, Madrid, Spain), Flamenco guitarist and composer.

Born into a family of Gitano (Romani) cattle traders, Ramón Montoya used earnings from working in the trade to purchase his first g ...

, have introduced other positions: Montoya himself started to use other chords for the tonic in the modern Dorian sections of several ''palos''; F for '' tarantas'', B for ''granaína Granaína () is a flamenco style of singing and guitar playing from Granada. It is a variant of the Granada fandangos. It was originally danceable, but now has lost its rhythm, is much slower, and is usually only sung or played as a guitar solo, r ...

s'' and A for the ''minera''. Montoya also created a new ''palo'' as a solo for guitar, the ''rondeña A Rondeña is a ''palo'' or musical form of flamenco originating in the town of Ronda in the province of Málaga in Spain.

In common with other ''palos'' originating in Málaga, the rondeña antedated flamenco proper and became incorporated into i ...

'' in C with ''scordatura

Scordatura (; literally, Italian for "discord", or "mistuning") is a tuning of a string instrument that is different from the normal, standard tuning. It typically attempts to allow special effects or unusual chords or timbre, or to make certain pa ...

''. Later guitarists have further extended the repertoire of tonalities, chord positions and ''scordatura''.

There are also ''palos'' in major mode; most cantiñas

The ''cantiñas'' () is a group of flamenco ''palos'' (musical forms), originated in the area of Cádiz in Andalusia (although some styles of cantiña have developed in the province of Seville). They share the same '' compás'' or rhythmic pattern ...

and alegrías

''Alegrías'' () is a flamenco palo or musical form, which has a rhythm consisting of 12 beats. It is similar to Soleares. Its beat emphasis is as follows: 1 2 '' 4 5 '' 7 '' 9 0'' 11 2''. Alegrías originated in Cádiz. Alegrías belongs to ...

, guajiras

Guajira is a music genre derived from the punto cubano. According to some specialists, the punto cubano was known in Spain since the 18th century, where it was called "punto de La Habana", and by the second half of the 19th century it was adopt ...

, some ''bulerías

''Bulería'' (; interchangeable with the plural, ''bulerías'') is a fast flamenco rhythm made up of a 12 beat cycle with emphasis in two general forms as follows:

This may be thought of as a measure of followed by a measure of (known ...

'' and ''tonás Tonás () is a palo or type of flamenco songs. It belongs to the wider category of Cantes a palo seco, ''palos'' that are sung a cappella. Owing to this feature, they are considered by traditional flamencology to be the oldest surviving musical fo ...

'', and the ''cabales'' (a major type of ''siguiriyas

''Siguiriyas'' (; also ''seguiriyas'',

''siguerillas'', ''siguirillas'', '' seguidilla gitana'', etc.) are a form of flamenco music in the cante jondo category. This deep, expressive style is among the most important in flamenco. Unlike other pa ...

''). The minor mode is restricted to the ''Farruca ''Farruca'' () is a form of flamenco music developed in the late 19th century. Classified as a cante chico, it is traditionally sung and danced by men. Its origin is traditionally associated with Galicia, a region in northern Spain.

An instrumenta ...

'', the ''milongas'' (among ''cantes de ida y vuelta Cantes de ida y vuelta () is a Spanish expression literally meaning roundtrip songs. It refers to a group of flamenco musical forms or palos with diverse musical features, which "travelled back" from Latin America (mainly Cuba) as styles that, havi ...

''), and some styles of ''tangos, bulerías'', etc. In general traditional palos in major and minor mode are limited harmonically to two-chord (tonic–dominant) or three-chord (tonic–subdominant–dominant) progressions . However modern guitarists have introduced chord substitution

In music theory, chord substitution is the technique of using a chord in place of another in a progression of chords, or a chord progression. Much of the European classical repertoire and the vast majority of blues, jazz and rock music songs a ...

, transition chords, and even modulation

In electronics and telecommunications, modulation is the process of varying one or more properties of a periodic waveform, called the ''carrier signal'', with a separate signal called the ''modulation signal'' that typically contains informatio ...

.

''Fandangos

Fandango is a lively partner dance originating from Portugal and Spain, usually in triple meter, traditionally accompanied by guitars, castanets, or hand-clapping. Fandango can both be sung and danced. Sung fandango is usually bipartite: it has ...

'' and derivative ''palos'' such as '' malagueñas'', ''tarantas'' and ''cartageneras

''Cartageneras'' () are a flamenco palo belonging to the category of the '' cantes de las minas'' (in English, songs of the mines) or ''cantes minero-levantinos'' (eastern miner songs). As the rest of the songs in this category, it derives from o ...

are bimodal'': guitar introductions are in Phrygian mode while the singing develops in major mode, modulating to Phrygian at the end of the stanza .

Melody

Dionisio Preciado, quoted by Sabas de , established the following characteristics for the melodies of flamenco singing: #Microtonality

Microtonal music or microtonality is the use in music of microtones—intervals smaller than a semitone, also called "microintervals". It may also be extended to include any music using intervals not found in the customary Western tuning of tw ...

: presence of intervals

Interval may refer to:

Mathematics and physics

* Interval (mathematics), a range of numbers

** Partially ordered set#Intervals, its generalization from numbers to arbitrary partially ordered sets

* A statistical level of measurement

* Interval e ...

smaller than the semitone

A semitone, also called a half step or a half tone, is the smallest musical interval commonly used in Western tonal music, and it is considered the most dissonant when sounded harmonically.

It is defined as the interval between two adjacent no ...

.

#Portamento

In music, portamento (plural: ''portamenti'', from old it, portamento, meaning "carriage" or "carrying") is a pitch sliding from one note to another. The term originated from the Italian expression "''portamento della voce''" ("carriage of the v ...

: frequently, the change from one note to another is done in a smooth transition, rather than using discrete intervals.

#Short tessitura

In music, tessitura (, pl. ''tessiture'', "texture"; ) is the most acceptable and comfortable vocal range for a given singer or less frequently, musical instrument, the range in which a given type of voice presents its best-sounding (or character ...

or range

Range may refer to:

Geography

* Range (geographic), a chain of hills or mountains; a somewhat linear, complex mountainous or hilly area (cordillera, sierra)

** Mountain range, a group of mountains bordered by lowlands

* Range, a term used to i ...

: Most traditional flamenco songs are limited to a range of a sixth (four tones and a half). The impression of vocal effort is the result of using different timbre

In music, timbre ( ), also known as tone color or tone quality (from psychoacoustics), is the perceived sound quality of a musical note, sound or musical tone, tone. Timbre distinguishes different types of sound production, such as choir voice ...

s, and variety is accomplished by the use of microtones.

#Use of enharmonic scale

In music theory, an enharmonic scale is "an maginarygradual progression by quarter tones" or any " usicalscale proceeding by quarter tones". The enharmonic scale uses dieses (divisions) nonexistent on most keyboards,John Wall Callcott (1833). ...

. While in equal temperament

An equal temperament is a musical temperament or tuning system, which approximates just intervals by dividing an octave (or other interval) into equal steps. This means the ratio of the frequencies of any adjacent pair of notes is the same, wh ...

scales, enharmonic

In modern musical notation and tuning, an enharmonic equivalent is a note, interval, or key signature that is equivalent to some other note, interval, or key signature but "spelled", or named differently. The enharmonic spelling of a written n ...

s are notes with identical pitch but different spellings (e.g. A♭ and G♯); in flamenco, as in unequal temperament scales, there is a microtonal intervalic difference between enharmonic notes.

#Insistence on a note and its contiguous chromatic notes (also frequent in the guitar), producing a sense of urgency.

#Baroque ornamentation

An ornament is something used for decoration.

Ornament may also refer to:

Decoration

*Ornament (art), any purely decorative element in architecture and the decorative arts

*Biological ornament, a characteristic of animals that appear to serve on ...

, with an expressive, rather than merely aesthetic function.

#Apparent lack of regular rhythm, especially in the siguiriyas

''Siguiriyas'' (; also ''seguiriyas'',

''siguerillas'', ''siguirillas'', '' seguidilla gitana'', etc.) are a form of flamenco music in the cante jondo category. This deep, expressive style is among the most important in flamenco. Unlike other pa ...

: the melodic rhythm of the sung line is different from the metric rhythm of the accompaniment.

#Most styles express sad and bitter feelings.

#Melodic improvisation

Improvisation is the activity of making or doing something not planned beforehand, using whatever can be found. Improvisation in the performing arts is a very spontaneous performance without specific or scripted preparation. The skills of impr ...

: flamenco singing is not, strictly speaking, improvised, but based on a relatively small number of traditional songs, singers add variations on the spur of the moment.

Musicologist Hipólito Rossy adds the following characteristics :

*Flamenco melodies are characterized by a descending tendency, as opposed to, for example, a typical opera aria

In music, an aria (Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompanime ...

, they usually go from the higher pitches to the lower ones, and from forte

Forte or Forté may refer to:

Music

*Forte (music), a musical dynamic meaning "loudly" or "strong"

*Forte number, an ordering given to every pitch class set

*Forte (notation program), a suite of musical score notation programs

*Forte (vocal gro ...

to piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keyboa ...

, as was usual in ancient Greek scales.

*In many styles, such as soleá

''Soleares'' (plural of ''soleá'', ) is one of the most basic forms or '' palos'' of Flamenco music, probably originating among the Calé Romani people of Cádiz or Seville in Andalusia, the most southern region of Spain. It is usually accompa ...

or siguiriya

''Siguiriyas'' (; also ''seguiriyas'',

''siguerillas'', ''siguirillas'', ''seguidilla gitana'', etc.) are a form of flamenco music in the cante jondo category. This deep, expressive style is among the most important in flamenco. Unlike other pal ...

, the melody tends to proceed in contiguous degrees of the scale. Skips of a third or a fourth are rarer. However, in fandangos

Fandango is a lively partner dance originating from Portugal and Spain, usually in triple meter, traditionally accompanied by guitars, castanets, or hand-clapping. Fandango can both be sung and danced. Sung fandango is usually bipartite: it has ...

and fandango-derived styles, fourths and sixths can often be found, especially at the beginning of each line of verse. According to Rossy, this is proof of the more recent creation of this type of songs, influenced by Castilian jota

Jota may refer to:

__NOTOC__

* Iota (Ι, ι), the name of the 9th letter in the Greek alphabet;

* (figuratively) ''Something very small'', based on the fact that the letter Iota (lat. i) is the smallest character in the alphabet;

* The name of the ...

.

Compás or time signature

Compás is the Spanish word formetre

The metre (British spelling) or meter (American spelling; see spelling differences) (from the French unit , from the Greek noun , "measure"), symbol m, is the primary unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), though its pref ...

or time signature

The time signature (also known as meter signature, metre signature, or measure signature) is a notational convention used in Western musical notation to specify how many beats (pulses) are contained in each measure (bar), and which note value ...

(in classical music theory

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the "rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (ke ...

). It also refers to the rhythmic cycle, or layout, of a ''palo''.

The compás is fundamental to flamenco. Compás is most often translated as rhythm

Rhythm (from Greek , ''rhythmos'', "any regular recurring motion, symmetry") generally means a " movement marked by the regulated succession of strong and weak elements, or of opposite or different conditions". This general meaning of regular recu ...