Early flying machines on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Early flying machines include all forms of

Early flying machines include all forms of

According to Aulus Gellius, the Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and strategist Archytas (428–347 BC) was reputed to have designed and built the first artificial, self-propelled flying device, a bird-shaped model propelled by a jet of what was probably steam, said to have actually flown some 200 metres around 400 BC. According to Gellius, this machine, which its inventor called ''The Pigeon'' (Greek: ''Περιστέρα'' "Peristera"), was suspended on a wire or pivot for its "flight" and was powered by a "concealed aura or spirit".

Eventually some tried to build flying devices, such as birdlike wings, and to fly by jumping off a tower, hill, or cliff. During this early period physical issues of lift, stability, and control were not understood, and most attempts ended in serious injury or death. In the 1st century AD, Chinese Emperor

According to Aulus Gellius, the Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and strategist Archytas (428–347 BC) was reputed to have designed and built the first artificial, self-propelled flying device, a bird-shaped model propelled by a jet of what was probably steam, said to have actually flown some 200 metres around 400 BC. According to Gellius, this machine, which its inventor called ''The Pigeon'' (Greek: ''Περιστέρα'' "Peristera"), was suspended on a wire or pivot for its "flight" and was powered by a "concealed aura or spirit".

Eventually some tried to build flying devices, such as birdlike wings, and to fly by jumping off a tower, hill, or cliff. During this early period physical issues of lift, stability, and control were not understood, and most attempts ended in serious injury or death. In the 1st century AD, Chinese Emperor

The

The

The use of a

The use of a

From ancient times the Chinese have understood that hot air rises and have applied the principle to a type of small

From ancient times the Chinese have understood that hot air rises and have applied the principle to a type of small

The modern era of lighter-than-air flight began early in the 17th century with

The modern era of lighter-than-air flight began early in the 17th century with  1783 was a watershed year for ballooning. Between 4 June and 1 December five separate French balloons achieved important aviation firsts:

*4 June: The

1783 was a watershed year for ballooning. Between 4 June and 1 December five separate French balloons achieved important aviation firsts:

*4 June: The

Work on developing a dirigible (steerable) balloon, nowadays called an

Work on developing a dirigible (steerable) balloon, nowadays called an

These aircraft were not practical. Besides being generally frail and short-lived, they were non-rigid or at best semi-rigid. Consequently, it was difficult to make them large enough to carry a commercial load.

Count

These aircraft were not practical. Besides being generally frail and short-lived, they were non-rigid or at best semi-rigid. Consequently, it was difficult to make them large enough to carry a commercial load.

Count

Early flying machines include all forms of

Early flying machines include all forms of aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engine ...

studied or constructed before the development of the modern aeroplane by 1910. The story of modern flight begins more than a century before the first successful manned aeroplane, and the earliest aircraft thousands of years before.

Primitive beginnings

Legends

Some ancient mythologies feature legends of men using flying devices. One of the earliest known is the Greek legend ofDaedalus

In Greek mythology, Daedalus (, ; Greek: Δαίδαλος; Latin: ''Daedalus''; Etruscan: ''Taitale'') was a skillful architect and craftsman, seen as a symbol of wisdom, knowledge and power. He is the father of Icarus, the uncle of Perdix, a ...

; in Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

's version, Daedalus fastens feathers together with thread and wax to mimic the wings of a bird. Other ancient legends include the Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

Vimana

Vimāna are mythological flying palaces or chariots described in Hindu texts and Sanskrit epics. The "Pushpaka Vimana" of Ravana (who took it from Kubera; Rama returned it to Kubera) is the most quoted example of a vimana. Vimanas are also men ...

flying palace or chariot, the biblical Ezekiel's Chariot, the Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

''roth rámach'' built by blind druid Mug Ruith

Mug Ruith (or Mogh Roith, "slave of the wheel") is a figure in Irish mythology, a powerful blind druid of Munster who lived on Valentia Island, County Kerry. He could grow to enormous size, and his breath caused storms and turned men to stone. He ...

and Simon Magus

Simon Magus (Greek Σίμων ὁ μάγος, Latin: Simon Magus), also known as Simon the Sorcerer or Simon the Magician, was a religious figure whose confrontation with Peter is recorded in Acts . The act of simony, or paying for position, is ...

, various stories about magic carpet

A magic carpet, also called a flying carpet, is a legendary carpet and common trope in fantasy fiction. It is typically used as a form of transportation and can quickly or instantaneously carry its users to their destination.

In literature

One o ...

s, and the mythical British King Bladud, who conjured up flying wings. The Flying Throne of Kay Kāvus was a legendary eagle-propelled craft built by the mythical Shah of Persia, Kay Kāvus, used for flying him all the way to China.

Early attempts

According to Aulus Gellius, the Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and strategist Archytas (428–347 BC) was reputed to have designed and built the first artificial, self-propelled flying device, a bird-shaped model propelled by a jet of what was probably steam, said to have actually flown some 200 metres around 400 BC. According to Gellius, this machine, which its inventor called ''The Pigeon'' (Greek: ''Περιστέρα'' "Peristera"), was suspended on a wire or pivot for its "flight" and was powered by a "concealed aura or spirit".

Eventually some tried to build flying devices, such as birdlike wings, and to fly by jumping off a tower, hill, or cliff. During this early period physical issues of lift, stability, and control were not understood, and most attempts ended in serious injury or death. In the 1st century AD, Chinese Emperor

According to Aulus Gellius, the Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and strategist Archytas (428–347 BC) was reputed to have designed and built the first artificial, self-propelled flying device, a bird-shaped model propelled by a jet of what was probably steam, said to have actually flown some 200 metres around 400 BC. According to Gellius, this machine, which its inventor called ''The Pigeon'' (Greek: ''Περιστέρα'' "Peristera"), was suspended on a wire or pivot for its "flight" and was powered by a "concealed aura or spirit".

Eventually some tried to build flying devices, such as birdlike wings, and to fly by jumping off a tower, hill, or cliff. During this early period physical issues of lift, stability, and control were not understood, and most attempts ended in serious injury or death. In the 1st century AD, Chinese Emperor Wang Mang

Wang Mang () (c. 45 – 6 October 23 CE), courtesy name Jujun (), was the founder and the only emperor of the short-lived Chinese Xin dynasty. He was originally an official and consort kin of the Han dynasty and later seized the thron ...

recruited a specialist scout to be bound with bird feathers; he is claimed to have glided about 100 meters. In 559 AD, Yuan Huangtou

Yuan Huangtou (; died in 559) was the son of emperor Yuan Lang of Northern Wei dynasty of China. At that time, paramount general Gao Yang took control of the court of Northern Wei's branch successor state Eastern Wei and set the emperor as a pupp ...

is said to have landed safely from an enforced tower jump.

The Andalusian scientist Abbas ibn Firnas

Abu al-Qasim Abbas ibn Firnas ibn Wirdas al-Takurini ( ar, أبو القاسم عباس بن فرناس بن ورداس التاكرني; c. 809/810 – 887 A.D.), also known as Abbas ibn Firnas ( ar, عباس ابن فرناس), Latinized Armen ...

(810–887 AD) reportedly made a jump in Córdoba, Spain

Córdoba (; ),, Arabic: قُرطبة DIN: . or Cordova () in English, is a city in Andalusia, Spain, and the capital of the province of Córdoba. It is the third most populated municipality in Andalusia and the 11th overall in the country.

The ...

, covering his body with vulture feathers and attaching two wings to his arms. Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (Spring, 1961). "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition", ''Technology and Culture'' 2 (2), pp. 97–111 01/ref> The flight attempt was reported by the 17th-century Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

n historian Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari

Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Maqqarī al-Tilmisānī (or al-Maḳḳarī) (), (1577-1632) was an Algerian scholar, biographer and historian who is best known for his , a compendium of the history of Al-Andalus which provided a basis for the scholar ...

, who linked it to a 9th century poem by one of Muhammad I of Córdoba

Muhammad I (822–886) () was the ''Umayyad'' emir of Córdoba from 852 to 886 in the Al-Andalus ( Moorish Iberia).

Biography

Muhammad was born in Córdoba. His reign was marked by several revolts and separatist movements of the Muwallad (Mus ...

's court poets. Al-Maqqari stated that Firnas flew some distance, before landing with some injuries, attributed to his lacking a tail (as birds use to land). The historian Lynn Townsend White, Jr. concluded that ibn Firnas made the first successful flight in history. Writing in the twelfth century, William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury ( la, Willelmus Malmesbiriensis; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as " ...

stated that the 11th-century Benedictine monk Eilmer of Malmesbury

Eilmer of Malmesbury (also known as Oliver due to a scribe's miscopying, or Elmer, or Æthelmær) was an 11th-century English Benedictine monk best known for his early attempt at a gliding flight using wings.

Life

Eilmer was a monk of Malme ...

attached wings to his hands and feet and flew a short distance, but broke both legs while landing, also having neglected to make himself a tail.

Early kites

The

The kite

A kite is a tethered heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create lift and drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have a bridle and tail to guide the fac ...

was invented in China, possibly as far back as the 5th century BC by Mozi (also Mo Di) and Lu Ban (also Gongshu Ban). These leaf kites were constructed by stretching silk over a split bamboo framework. The earliest known Chinese kites were flat (not bowed) and often rectangular. Later, tailless kites incorporated a stabilizing bowline. Designs often emulated flying insects, birds, and other beasts, both real and mythical. Some were fitted with strings and whistles to make musical sounds while flying.

In 549 AD, a kite made of paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, rags, grasses or other vegetable sources in water, draining the water through fine mesh leaving the fibre evenly distrib ...

was used as a message for a rescue mission. Ancient and medieval Chinese sources list other uses of kites for measuring distances, testing the wind, lifting men, signalling, and communication for military operations.

After its introduction into India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, the kite further evolved into the fighter kite

Fighter kites are kites used for the sport of kite fighting. Traditionally most are small, unstable single-line flat kites where line tension alone is used for control, at least part of which is manja, typically glass-coated cotton strands, ...

. Traditionally these are small, unstable single line flat kites where line tension alone is used for control, and an abrasive line is used to cut down other kites.

Kites also spread throughout Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

, as far as New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

. Anthropomorphic kites made from cloth and wood were used in religious ceremonies to send prayers to the gods. By 1634, kites had reached the West, with an illustration of a diamond kite with a tail appearing in Bate's ''Mysteries of nature and art''.

Man-carrying kites

Man-carrying kites are believed to have been used extensively in ancient China, for both civil and military purposes and sometimes enforced as a punishment.Pelham, D.; ''The Penguin book of kites'', Penguin (1976) Stories of man-carrying kites also occur in Japan, following the introduction of the kite from China around the seventh century AD. It is said that at one time there was a Japanese law against man-carrying kites. In 1282, the European explorer Marco Polo described the Chinese techniques then current and commented on the hazards and cruelty involved. To foretell whether a ship should sail, a man would be strapped to a kite having a rectangular grid framework and the subsequent flight pattern used to divine the outlook.Rotor wings

rotor

Rotor may refer to:

Science and technology

Engineering

* Rotor (electric), the non-stationary part of an alternator or electric motor, operating with a stationary element so called the stator

*Helicopter rotor, the rotary wing(s) of a rotorcraft ...

for vertical flight has existed since the 4th century AD in the form of the bamboo-copter

The bamboo-copter, also known as the bamboo dragonfly or Chinese top (Chinese ''zhuqingting'' (竹蜻蜓), Japanese ''taketonbo'' ), is a toy helicopter rotor that flies up when its shaft is rapidly spun. This helicopter-like top originated in ...

, an ancient Chinese toy. The bamboo-copter is spun by rolling a stick attached to a rotor. The spinning creates lift, and the toy flies when released. The philosopher Ge Hong's book, the '' Baopuzi'' (Master Who Embraces Simplicity), written around 317, describes the apocryphal use of a possible rotor in aircraft: "Some have made flying cars eiche 飛車with wood from the inner part of the jujube tree, using ox-leather (straps) fastened to returning blades so as to set the machine in motion."

The similar "moulinet à noix" (rotor on a nut), as well as string-pull toys with four blades, appeared in Europe in the 14th century.

Hot air balloons

From ancient times the Chinese have understood that hot air rises and have applied the principle to a type of small

From ancient times the Chinese have understood that hot air rises and have applied the principle to a type of small hot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries ...

called a sky lantern

A sky lantern (), also known as Kǒngmíng lantern (), or Chinese lantern, is a small hot air balloon made of paper, with an opening at the bottom where a small fire is suspended.

In Asia and elsewhere around the world, sky lanterns have bee ...

. A sky lantern consists of a paper balloon under or just inside which a small lamp is placed. Sky lanterns are traditionally launched for pleasure and during festivals. According to Joseph Needham, such lanterns were known in China from the 3rd century BC. Their military use is attributed to the general Zhuge Liang

Zhuge Liang ( zh, t=諸葛亮 / 诸葛亮) (181 – September 234), courtesy name Kongming, was a Chinese statesman and military strategist. He was chancellor and later regent of the state of Shu Han during the Three Kingdoms period. He is ...

, who is said to have used them to scare the enemy troops.

There is evidence the Chinese also "solved the problem of aerial navigation" using balloons, hundreds of years before the 18th century.

The Renaissance

Eventually some investigators began to discover and define some of the basics of scientific aircraft design. Powered designs were either still driven by man-power or used a metal spring. In his 1250 book ''De mirabili potestate artis et naturae'' (Secrets of Art and Nature), the Englishman Roger Bacon predicted future designs for a balloon filled with an unspecified aether as well as a man-poweredornithopter

An ornithopter (from Greek ''ornis, ornith-'' "bird" and ''pteron'' "wing") is an aircraft that flies by flapping its wings. Designers sought to imitate the flapping-wing flight of birds, bats, and insects. Though machines may differ in form, ...

, claiming to know someone who had invented the latter.

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, Drawing, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially res ...

studied bird flight for many years, analyzing it rationally and anticipating many principles of aerodynamics

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dy ...

. He understood that "An object offers as much resistance to the air as the air does to the object", anticipating Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

's third law of motion (published in 1687). From the last years of the 15th century onwards, Leonardo wrote about and sketched many designs for flying machines and mechanisms, including ornithopters, fixed-wing gliders, rotorcraft and parachutes. His early designs were man-powered types including rotorcraft and ornithopters (improving on Bacon's proposal by adding a stabilizing tail). He eventually came to realise the impracticality of these and turned to controlled gliding flight, also sketching some designs powered by a spring.

In 1488, Leonardo drew a hang glider

Hang gliding is an air sport or recreational activity in which a pilot flies a light, non-motorised foot-launched heavier-than-air aircraft called a hang glider. Most modern hang gliders are made of an aluminium alloy or composite frame cover ...

design in which the inner parts of the wings are fixed, and some control surfaces are provided towards the tips (as in the gliding flight of birds). His drawings survive and are deemed flight-worthy in principle, but he himself never flew in such a craft. In an essay titled ''Sul volo'' (''On flight''), he describes a flying machine called "the bird" which he built from starched linen, leather joints, and raw silk thongs. In the ''Codex Atlanticus

The Codex Atlanticus (Atlantic Codex) is a 12-volume, bound set of drawings and writings (in Italian) by Leonardo da Vinci, the largest single set. Its name indicates the large paper used to preserve original Leonardo notebook pages, which was us ...

'', he wrote, "Tomorrow morning, on the second day of January, 1496, I will make the thong and the attempt." Some of Leonardo's other designs, such as the four-person aerial screw, similar to a helicopter, have severe flaws. He drew and wrote about a design for an ornithopter

An ornithopter (from Greek ''ornis, ornith-'' "bird" and ''pteron'' "wing") is an aircraft that flies by flapping its wings. Designers sought to imitate the flapping-wing flight of birds, bats, and insects. Though machines may differ in form, ...

around 1490. Leonardo's work remained unknown until 1797, and so had no influence on developments over the next three hundred years. Nor were his designs based on particularly good science.

Other attempts

In 1496, a man named Seccio broke both arms inNuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

while attempting flight. In 1507, John Damian strapped on wings covered with chicken feathers and jumped from the walls of Stirling Castle in Scotland, breaking his thigh; he later blamed it on not using eagle feathers.

The earliest report of an attempted jet flight dates back to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. In 1633, the aviator Lagâri Hasan Çelebi reportedly used a cone-shaped rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

to make the first attempt at a jet flight.

Francis Willughby

Francis Willughby (sometimes spelt Willoughby, la, Franciscus Willughbeius) FRS (22 November 1635 – 3 July 1672) was an English ornithologist and ichthyologist, and an early student of linguistics and games.

He was born and raised at ...

's suggestion, published in 1676, that human legs were more comparable to birds' wings in strength than arms, had occasional influence. On 15 May 1793, the Spanish inventor Diego Marín Aguilera

Diego Marín Aguilera (1757–1799) was a Spanish inventor who was an early aviation pioneer.

Early life

Born in Coruña del Conde, Marín became the head of his household after his father died and had to take care of his seven siblings. He wo ...

jumped with his glider

Glider may refer to:

Aircraft and transport Aircraft

* Glider (aircraft), heavier-than-air aircraft primarily intended for unpowered flight

** Glider (sailplane), a rigid-winged glider aircraft with an undercarriage, used in the sport of glidin ...

from the highest part of the castle of Coruña del Conde, reaching a height of about 5 or 6 m, and gliding for about 360 metres. As late as 1811, Albrecht Berblinger

Albrecht Ludwig Berblinger (24 June 1770 – 28 January 1829), also known as the Tailor of Ulm, is famous for having constructed a working flying machine, presumably a hang glider.

Early life

Berblinger was the seventh child of a poor fa ...

constructed an ornithopter and jumped into the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

at Ulm

Ulm () is a city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Danube on the border with Bavaria. The city, which has an estimated population of more than 126,000 (2018), forms an urban district of its own (german: link=no, ...

.

Lighter than air

Balloons

The modern era of lighter-than-air flight began early in the 17th century with

The modern era of lighter-than-air flight began early in the 17th century with Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He wa ...

's experiments in which he showed that air has weight. Around 1650, Cyrano de Bergerac

Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac ( , ; 6 March 1619 – 28 July 1655) was a French novelist, playwright, epistolarian, and duelist.

A bold and innovative author, his work was part of the libertine literature of the first half of the 17th cen ...

wrote some fantasy novels in which he described the principle of ascent using a substance (dew) he supposed to be lighter than air, and descending by releasing a controlled amount of the substance. Francesco Lana de Terzi

Francesco Lana de Terzi (1631 in Brescia, Lombardy – 22 February 1687, in Brescia, Lombardy) was an Italian Jesuit priest, mathematician, naturalist and aeronautics pioneer. Having been professor of physics and mathematics at Brescia, he first ...

measured the pressure of air at sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardise ...

and in 1670 proposed the first scientifically credible lifting medium in the form of hollow metal spheres from which all the air had been pumped out. These would be lighter than the displaced air and able to lift an airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

. His proposed methods of controlling height are still in use today: carrying ballast which may be dropped overboard to gain height, and venting the lifting containers to lose height. In practice de Terzi's spheres would have collapsed under air pressure, and further developments had to wait for more practicable lifting gases.

The first documented balloon flight in Europe was of a model made by the Brazilian-born Portuguese priest Bartolomeu de Gusmão

Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão (December 1685 – 18 November 1724) was a Brazilian-born Portuguese priest and naturalist, who was a pioneer of lighter-than-air airship design.

Early life

Gusmão was born at Santos, then part of the Portugue ...

. On 8 August 1709, in Lisbon, he made a small hot-air balloon of paper with a fire burning beneath it, lifting it about in front of king John V and the Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

court.

In the mid-18th century the Montgolfier brothers

The Montgolfier brothers – Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (; 26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (; 6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799) – were aviation pioneers, balloonists and paper manufacturers from the commune A ...

began experimenting with parachutes and balloons in France. Their balloons were made of paper, and early experiments using steam as the lifting gas were short-lived due to its effect on the paper as it condensed. Mistaking smoke for a kind of steam, they began filling their balloons with hot smoky air which they called "electric smoke". Despite not fully understanding the principles at work, they made some successful launches and in December 1782 flew a balloon to a height of . The French Académie des Sciences soon invited them to Paris to give a demonstration.

Meanwhile, the discovery of hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

led Joseph Black

Joseph Black (16 April 1728 – 6 December 1799) was a Scottish physicist and chemist, known for his discoveries of magnesium, latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide. He was Professor of Anatomy and Chemistry at the University of Glas ...

to propose its use as a lifting gas in about 1780, though practical demonstration awaited a gastight balloon material. On hearing of the Montgolfier Brothers' invitation, the French Academy member Jacques Charles

Jacques Alexandre César Charles (November 12, 1746 – April 7, 1823) was a French inventor, scientist, mathematician, and balloonist.

Charles wrote almost nothing about mathematics, and most of what has been credited to him was due to mistaking ...

offered a similar demonstration of a hydrogen balloon and this was accepted. Charles and two craftsmen, the Robert brothers, developed a gastight material of rubberised silk and set to work.

1783 was a watershed year for ballooning. Between 4 June and 1 December five separate French balloons achieved important aviation firsts:

*4 June: The

1783 was a watershed year for ballooning. Between 4 June and 1 December five separate French balloons achieved important aviation firsts:

*4 June: The Montgolfier brothers

The Montgolfier brothers – Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (; 26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (; 6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799) – were aviation pioneers, balloonists and paper manufacturers from the commune A ...

' unmanned hot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries ...

lifted a sheep, a duck and a chicken in a basket hanging beneath at Annonay.

*27 August: Professor Jacques Charles and the Robert brothers

Les Frères Robert were two French brothers. Anne-Jean Robert (1758–1820) and Nicolas-Louis Robert (1760–1820) were the engineers who built the world's first hydrogen balloon for professor Jacques Charles, which flew from central Paris o ...

flew an unmanned hydrogen balloon. The hydrogen gas was generated by chemical reaction during the filling process.

*19 October: The Montgolfiers launched the first manned flight, a tethered balloon with humans on board, at the '' Folie Titon'' in Paris. The aviators were the scientist Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier

Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier () was a French chemistry and physics teacher, and one of the first pioneers of aviation. He made the first manned free balloon flight with François Laurent d'Arlandes on 21 November 1783, in a Montgolfier bal ...

, the manufacture manager Jean-Baptiste Réveillon Jean-Baptiste Réveillon (1725–1811) was a French wallpaper manufacturer. In 1789 Réveillon made a statement on the price of bread that was misinterpreted by the Parisian populace as advocating lower wages. He fled France after his home and his w ...

, and Giroud de Villette.

*21 November: The Montgolfiers launched the first free flight balloon with human passengers. King Louis XVI had originally decreed that condemned criminals would be the first pilots, but Rozier, along with the Marquis François d'Arlandes, successfully petitioned for the honor. They drifted in a balloon powered by a wood fire. covered in 25 minutes.

*1 December: Jacques Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert launched a manned hydrogen balloon from the Jardin des Tuileries

The Tuileries Garden (french: Jardin des Tuileries, ) is a public garden located between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. Created by Catherine de' Medici as the garden of the Tuileries Palace in ...

in Paris. They ascended to a height of about and landed at sunset in Nesles-la-Vallée

Nesles-la-Vallée () is a commune in the Val-d'Oise department in Île-de-France in northern France.

See also

*Communes of the Val-d'Oise department

The following is a list of the 184 communes of the Val-d'Oise department of France.

The co ...

after a flight of 2 hours and 5 minutes, covering . After Robert alighted Charles decided to ascend alone. This time he ascended rapidly to an altitude of about , where he saw the sun again but also suffered extreme pain in his ears.

The Montgolfier designs had several shortcomings, not least the need for dry weather and a tendency for sparks from the fire to set light to the paper balloon. The manned design had a gallery around the base of the balloon rather than the hanging basket of the first, unmanned design, which brought the paper closer to the fire. On their free flight, De Rozier and d'Arlandes took buckets of water and sponges to douse these fires as they arose. On the other hand, the manned design of Charles was essentially modern. As a result of these exploits, the hot-air balloon became known as the ''Montgolfière'' type and the hydrogen balloon the ''Charlière''.

The next balloon of Charles and the Robert brothers was a Charlière that followed Jean Baptiste Meusnier

Jean Baptiste Marie Charles Meusnier de la Place (Tours, 19 June 1754 — le Pont de Cassel, near Mainz, 13 June 1793) was a French mathematician, engineer and Revolutionary general. He is best known for Meusnier's theorem on the curvature o ...

's proposals for an elongated dirigible balloon, and was notable for having an outer envelope with the gas contained in a second, inner ballonet

A ballonet is an air bag inside the outer envelope of an airship which, when inflated, reduces the volume available for the lifting gas, making it more dense. Because air is also denser than the lifting gas, inflating the ballonet reduces the over ...

. On 19 September 1784, it completed the first flight of over , between Paris and Beuvry, despite the man-powered propulsive devices proving useless.

In January the next year Jean Pierre Blanchard

Jean-Pierre rançoisBlanchard (4 July 1753 – 7 March 1809) was a French inventor, best known as a pioneer of gas balloon flight, who distinguished himself in the conquest of the air in a balloon, in particular the first crossing of the Englis ...

and John Jeffries

John Jeffries (5 February 1744 – 16 September 1819) was an American physician, scientist, and military surgeon with the British Army in Nova Scotia and New York during the American Revolution. He is best known for accompanying French invent ...

crossed the English Channel from Dover to the Bois de Felmores

Bois may refer to:

* Bois, Charente-Maritime, France

* Bois, West Virginia, United States

* Bois d'Arc, Texas, United States

* Les Bois, Switzerland

* Landskrona BoIS, a Swedish professional football club

* Tranås BoIS, a Swedish sports club

P ...

in a Charlière. But a similar attempt the other way ended in tragedy. To try to provide both endurance and controllability, de Rozier developed a balloon with both hot air and hydrogen gas bags, a design which was soon named after him as the ''Rozière''. His idea was to use the hydrogen section for constant lift and to navigate vertically by heating and allowing to cool the hot air section, in order to catch the most favourable wind at whatever altitude it was blowing. The balloon envelope was made of goldbeaters skin. Shortly after the flight began, de Rozier was seen to be venting hydrogen when it was ignited by a spark and the balloon went up in flames, killing those on board. The source of the spark is not known, but suggestions include static electricity or the brazier for the hot air section.

Ballooning quickly became a major "rage" in Europe in the late 18th century, providing the first detailed understanding of the relationship between altitude and the atmosphere. By the early 1900s, ballooning was a popular sport in Britain. These privately owned balloons usually used coal gas as the lifting gas. This has about half the lifting power of hydrogen, so the balloons had to be larger; however, coal gas was far more readily available, and the local gas works sometimes provided a special lightweight formula for ballooning events.

Tethered balloons were used during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

by the Union Army Balloon Corps

The Union Army Balloon Corps was a branch of the Union Army during the American Civil War, established by presidential appointee Thaddeus S. C. Lowe. It was organized as a civilian operation, which employed a group of prominent American aeronaut ...

. In 1863, the young Ferdinand von Zeppelin

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (german: Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin; 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a German general and later inventor of the Zeppelin rigid airships. His name soon became synonymous with airships a ...

, who was acting as a military observer with the Union Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

, first flew as a balloon passenger in a balloon that had been in service with the Union army. Later that century, the British Army would make use of observation balloons during the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

.

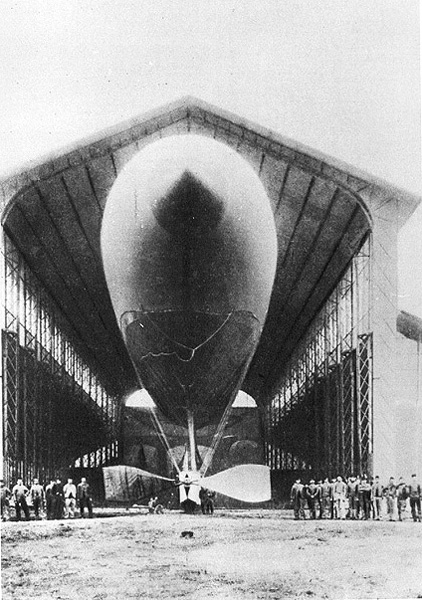

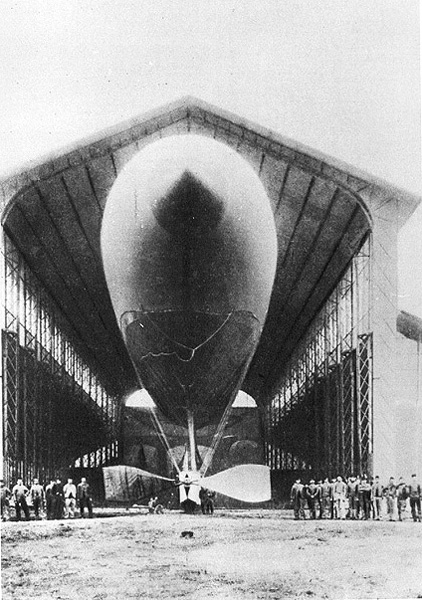

Dirigibles or airships

Work on developing a dirigible (steerable) balloon, nowadays called an

Work on developing a dirigible (steerable) balloon, nowadays called an airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

, continued sporadically throughout the 19th century. The first sustained powered, controlled flight in history is believed to have taken place on 24 September 1852 when Henri Giffard

Baptiste Jules Henri Jacques Giffard (8 February 182514 April 1882) was a French engineer. In 1852 he invented the steam injector and the powered Giffard dirigible airship.

Career

Giffard was born in Paris in 1825. He invented the injector a ...

flew about in France from Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

to Trappes

Trappes () is a Communes of France, commune in the Yvelines departments of France, department, region of Île-de-France, north-central France. It is a banlieue located in the western suburbs of Paris, from the Kilometre Zero, center of Paris, i ...

with the Giffard dirigible

__NOTOC__

The Giffard dirigible or Giffard airship was an airship built in France in 1852 by Henri Giffard, the first powered and steerable (french: dirigeable, directable) airship to fly. The craft featured an elongated hydrogen-filled envelop ...

, a non-rigid airship

A blimp, or non-rigid airship, is an airship (dirigible) without an internal structural framework or a keel. Unlike semi-rigid and rigid airships (e.g. Zeppelins), blimps rely on the pressure of the lifting gas (usually helium, rather than hydr ...

filled with hydrogen and powered by a steam engine driving a 3-bladed propeller.

In 1863, Solomon Andrews flew his aereon design, an unpowered, controllable dirigible in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. He flew a later design in 1866 around New York City and as far as Oyster Bay, New York. His technique of gliding under gravity works by changing the lift to provide propulsive force as the airship alternately rises and sinks, and so does not need a powerplant.

A further advance was made on 9 August 1884, when the first fully controllable free flight was made by Charles Renard and Arthur Constantin Krebs

Arthur Constantin Krebs (16 November 1850 in Vesoul, France – 22 March 1935 in Quimperlé, France) was a French officer and pioneer in automotive engineering.

Life

Collaborating with Charles Renard, he piloted the first fully controll ...

in a French Army electric-powered airship, '' La France''. The long, airship covered in 23 minutes with the aid of an electric motor, returning to its starting point. This was the first flight over a closed circuit.

These aircraft were not practical. Besides being generally frail and short-lived, they were non-rigid or at best semi-rigid. Consequently, it was difficult to make them large enough to carry a commercial load.

Count

These aircraft were not practical. Besides being generally frail and short-lived, they were non-rigid or at best semi-rigid. Consequently, it was difficult to make them large enough to carry a commercial load.

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (german: Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin; 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a German general and later inventor of the Zeppelin rigid airships. His name soon became synonymous with airships a ...

realised that a rigid outer frame would allow a much bigger airship. He founded the Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

firm, whose rigid ''Luftschiff Zeppelin 1'' (LZ 1) first flew from the Bodensee

Lake Constance (german: Bodensee, ) refers to three bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, called the Lak ...

on the Swiss border on 2 July 1900. The flight lasted 18 minutes. The second and third flights, in October 1900 and on 24 October 1900 respectively, beat the speed record of the French airship La France by .

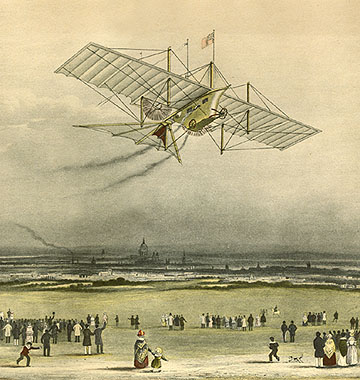

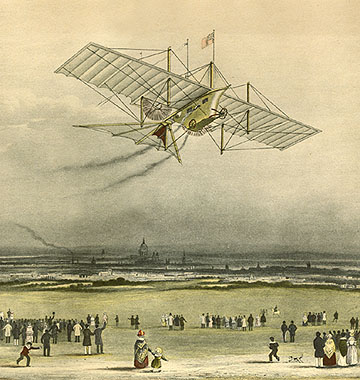

The Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont

Alberto Santos-Dumont ( Palmira, 20 July 1873 — Guarujá, 23 July 1932) was a Brazilian aeronaut, sportsman, inventor, and one of the few people to have contributed significantly to the early development of both lighter-than-air and heavie ...

became famous by designing, building, and flying dirigibles. He built and flew the first fully practical dirigible capable of routine, controlled flight. With his dirigible No.6 he won the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize on 19 October 1901 with a flight that took off from Saint-Cloud, rounded the Eiffel Tower and returned to its starting point. By this point, the airship had been established as the first practicable form of air travel.

Heavier than air

Parachutes

Da Vinci's design for a pyramid-shaped parachute remained unpublished for centuries. The first published design was the CroatianFausto Veranzio

Fausto Veranzio ( la, Faustus Verantius; hr, Faust Vrančić; Hungarian and Vernacular Latin: ''Verancsics Faustus'';Andrew L. SimonMade in Hungary: Hungarian contributions to universal culture/ref>sail, it comprised a square of material stretched across a square frame and retained by ropes. The parachutist was suspended by ropes from each of the four corners.

Italian inventor,

Italian inventor,

By the end of 1809, he had constructed the world's first full-size glider and flown it as an unmanned tethered kite. In the same year, goaded by the farcical antics of his contemporaries (see above), he began the publication of a landmark three-part treatise titled "On Aerial Navigation" (1809–1810).''Cayley, George''. "On Aerial Navigation

By the end of 1809, he had constructed the world's first full-size glider and flown it as an unmanned tethered kite. In the same year, goaded by the farcical antics of his contemporaries (see above), he began the publication of a landmark three-part treatise titled "On Aerial Navigation" (1809–1810).''Cayley, George''. "On Aerial Navigation

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

''Nicholson's Journal of Natural Philosophy'', 1809–1810. (Via

Raw text

Retrieved: 30 May 2010. In it he wrote the first scientific statement of the problem, "The whole problem is confined within these limits, viz. to make a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air". He identified the four vector forces that influence an aircraft: ''

Summary of First Cayley Memorial Lecture at the Brough Branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society

''

Drawing directly from Cayley's work, William Samuel Henson's 1842 design for an aerial steam carriage broke new ground. Henson proposed a span high-winged

Drawing directly from Cayley's work, William Samuel Henson's 1842 design for an aerial steam carriage broke new ground. Henson proposed a span high-winged  In 1871, Wenham and Browning made the first

In 1871, Wenham and Browning made the first

Félix du Temple eventually achieved a short hop with a full-size manned craft in 1874. His "''

Félix du Temple eventually achieved a short hop with a full-size manned craft in 1874. His "'' Equally authoritative as a theorist was Pénaud's fellow countryman Victor Tatin. In 1879, he flew a model which, like Pénaud's project, was a monoplane with twin tractor propellers but also had a separate horizontal tail. It was powered by compressed air, with the air tank forming the fuselage.

In Russia Alexander Mozhaiski constructed a steam-powered monoplane driven by one large tractor and two smaller pusher propellers. In 1884, it was launched from a ramp and remained airborne for .

That same year in France, Alexandre Goupil published his work ''La Locomotion Aérienne'' (''Aerial Locomotion''), although the flying machine he later constructed failed to fly.

Sir

Equally authoritative as a theorist was Pénaud's fellow countryman Victor Tatin. In 1879, he flew a model which, like Pénaud's project, was a monoplane with twin tractor propellers but also had a separate horizontal tail. It was powered by compressed air, with the air tank forming the fuselage.

In Russia Alexander Mozhaiski constructed a steam-powered monoplane driven by one large tractor and two smaller pusher propellers. In 1884, it was launched from a ramp and remained airborne for .

That same year in France, Alexandre Goupil published his work ''La Locomotion Aérienne'' (''Aerial Locomotion''), although the flying machine he later constructed failed to fly.

Sir  One of the last of the steam-powered pioneers, like Maxim ignoring his contemporaries who had moved on (see next section), was

One of the last of the steam-powered pioneers, like Maxim ignoring his contemporaries who had moved on (see next section), was

The glider constructed with the help of Massia and flown briefly by Biot in 1879 was based on the work of Mouillard and was still bird-like in form. It is preserved at the Musee de l'Air, France, and is claimed to be the earliest man-carrying flying machine still in existence.

In the last decade or so of the 19th century, a number of key figures were refining and defining the modern aeroplane. The Englishman

The glider constructed with the help of Massia and flown briefly by Biot in 1879 was based on the work of Mouillard and was still bird-like in form. It is preserved at the Musee de l'Air, France, and is claimed to be the earliest man-carrying flying machine still in existence.

In the last decade or so of the 19th century, a number of key figures were refining and defining the modern aeroplane. The Englishman  Otto Lilienthal was known as the "Glider King" or "Flying Man" of Germany. He duplicated Wenham's work and greatly expanded on it in 1884, publishing his research in 1889 as ''Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation'' (''Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst''). He also produced a series of gliders of a type now known as the hang glider, including bat-wing, monoplane and biplane forms, such as the

Otto Lilienthal was known as the "Glider King" or "Flying Man" of Germany. He duplicated Wenham's work and greatly expanded on it in 1884, publishing his research in 1889 as ''Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation'' (''Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst''). He also produced a series of gliders of a type now known as the hang glider, including bat-wing, monoplane and biplane forms, such as the

The Wrights solved both the control and power problems that confronted aeronautical pioneers. They invented

The Wrights solved both the control and power problems that confronted aeronautical pioneers. They invented  According to the

According to the

In 1906, the Brazilian

In 1906, the Brazilian

1901 in Austria,

1901 in Austria,

p.4

Some types developed during this period would see military service into, or even throughout, World War I. These include the

The early work on powered rotor lift was followed up by later investigators, independently from the development of fixed-wing aircraft.

In 19th century France an association was set up to collaborate on helicopter designs, of which there were many. In 1863

The early work on powered rotor lift was followed up by later investigators, independently from the development of fixed-wing aircraft.

In 19th century France an association was set up to collaborate on helicopter designs, of which there were many. In 1863

Prehistory of Flight

*

''Progress in Flying Machines'', 1891–1894

* * * * * * * ** ** ** * * * * * * *Walker, P. (1971). ''Early Aviation at Farnborough, Volume I: Balloons, Kites and Airships'', Macdonald.

Aerospaceweb – Who was the first to fly?

Aerospaceweb – Why do Brazilians consider Alberto Santos-Dumont the first man to fly if he didn't fly until 1906 and the Wright brothers did so in 1903?

Pre-Wright flying machines

The Early Birds of Aviation

by

Louis-Sébastien Lenormand

Louis-Sébastien Lenormand (May 25, 1757 – April 4, 1837) was a French chemist, physicist, inventor, monk, and a pioneer in parachuting.

He is considered as the first man to make a witnessed descent with a parachute and is also credited with ...

is considered the first human to make a witnessed descent with a parachute. On 26 December 1783, he jumped from the tower of the Montpellier observatory in France, in front of a crowd that included Joseph Montgolfier, using a parachute with a rigid wooden frame.

Between 1853 and 1854, Louis Charles Letur developed a parachute-glider comprising an umbrella-like parachute with smaller, triangular wings and vertical tail beneath. Letur died after it crashed in 1854.

Kites

Kites are most notable in the recent history of aviation primarily for their man-carrying or man-lifting capabilities, although they have also been important in other areas such asmeteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

.

The Frenchman Gaston Biot developed a man-lifting kite in 1868. Later, in 1880, Biot demonstrated to the French Society for Aerial Navigation a kite based on an open-ended cone, similar to a windsock

A windsock (also called a wind cone) is a conical textile tube that resembles a giant sock. It can be used as a basic indicator of wind speed and direction, or as decoration. They are typically used at airports to show the direction and strength ...

but attached to a flat surface. The man-carrying kite was developed a stage further in 1894 by Captain Baden Baden-Powell

Baden Fletcher Smyth Baden-Powell, (22 May 1860 – 3 October 1937) was a military aviation pioneer, and President of the Royal Aeronautical Society from 1900 to 1907.

Family

Baden was the youngest child of Baden Powell, and the brother o ...

, brother of Lord Baden-Powell, who strung a chain of hexagonal kites on a single line. A significant development came in 1893 when the Australian Lawrence Hargrave

Lawrence Hargrave, MRAeS, (29 January 18506 July 1915) was a British-born Australian engineer, explorer, astronomer, inventor and aeronautical pioneer.

Biography

Lawrence Hargrave was born in Greenwich, England, the second son of John Fletc ...

invented the box kite

A box kite is a high performance kite, noted for developing relatively high lift; it is a type within the family of cellular kites. The typical design has four parallel struts. The box is made rigid with diagonal crossed struts. There are two s ...

and some man-carrying experiments were carried out both in Australia and in the United States.Walker (1971) Volume I. On 27 December 1905, Neil MacDearmid

Neil is a masculine name of Gaelic and Irish origin. The name is an anglicisation of the Irish ''Niall'' which is of disputed derivation. The Irish name may be derived from words meaning "cloud", "passionate", "victory", "honour" or "champion".. A ...

was carried aloft in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, Canada by a large box kite named the Frost King, designed by Alexander Graham Bell.

Balloons were by then in use for both meteorology and military observation. Balloons can only be used in light winds, while kites can only be used in stronger winds. The American Samuel Franklin Cody

Samuel Franklin Cowdery (later known as Samuel Franklin Cody; 6 March 1867 – 7 August 1913, born Davenport, Iowa, USA)) was a Wild West showman and early pioneer of manned flight. He is most famous for his work on the large kites known a ...

, working in England, realised that the two types of craft between them allowed operation over a wide range of weather conditions. He developed Hargrave's basic design, adding additional lifting surfaces to create powerful man-lifting systems using multiple kites on a single line. Cody made many demonstrations of his system and would later sell four of his "war kite" systems to the Royal Navy. His kites also found use in carrying meteorological instruments aloft and he was made a fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society. In 1905, Sapper

A sapper, also called a pioneer or combat engineer, is a combatant or soldier who performs a variety of military engineering duties, such as breaching fortifications, demolitions, bridge-building, laying or clearing minefields, preparing ...

Moreton of the British Army's balloon section was lifted by a kite at Aldershot

Aldershot () is a town in Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme northeast corner of the county, southwest of London. The area is administered by Rushmoor Borough Council. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Alder ...

under Cody's supervision. In 1906, Cody was appointed Chief Instructor in Kiting at the Army School of Ballooning in Aldershot. He soon also joined the newly established Army Balloon Factory at Farnborough and continued developing his war kites for the British Army. In his own time, he developed a manned "glider-kite" which was launched on a tether like a kite and then released to glide freely. In 1907, Cody next fitted an aircraft engine to a modified unmanned "power-kite", the precursor to his later aeroplanes, and flew it inside the Balloon Shed, along a wire suspended from poles, before the Prince and Princess of Wales. The British Army officially adopted his war kites for their Balloon Companies in 1908.

17th and 18th centuries

Da Vinci's realisation that manpower alone was not sufficient for sustained flight was rediscovered independently in the 17th century byGiovanni Alfonso Borelli

Giovanni Alfonso Borelli (; 28 January 1608 – 31 December 1679) was a Renaissance Italian physiologist, physicist, and mathematician. He contributed to the modern principle of scientific investigation by continuing Galileo's practice of testin ...

and Robert Hooke. Hooke realised that some form of engine would be necessary and in 1655 made a spring-powered ornithopter model which was apparently able to fly.

Attempts to design or construct a true flying machine began, typically comprising a gondola with a supporting canopy and spring- or man-powered flappers for propulsion. Among the first were Hautsch and Burattini (1648). Others included de Gusmão's "Passarola" (1709 on), Swedenborg (1716), Desforges (1772), Bauer (1764), Meerwein (1781), and Blanchard (1781) who would later have more success with balloons. Rotary-winged helicopters likewise appeared, notably from Lomonosov (1754) and Paucton. A few model gliders flew successfully although some claims are contested, but in any event no full-size craft succeeded.

Italian inventor,

Italian inventor, Tito Livio Burattini

Tito Livio Burattini ( pl, Tytus Liwiusz Burattini, 8 March 1617 – 17 November 1681) was an inventor, architect, Egyptologist, scientist, instrument-maker, traveller, engineer, and nobleman, who spent his working life in Poland and Lithuania. ...

, invited by the Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

King Władysław IV Władysław is a Polish given male name, cognate with Vladislav. The feminine form is Władysława, archaic forms are Włodzisław (male) and Włodzisława (female), and Wladislaw is a variation. These names may refer to:

Famous people Mononym

* ...

to his court in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, built a model aircraft with four fixed glider wings in 1647. Described as "four pairs of wings attached to an elaborate 'dragon'", it was said to have successfully lifted a cat in 1648 but not Burattini himself. He promised that "only the most minor injuries" would result from landing the craft.Quoted in His "Dragon Volant" is considered "the most elaborate and sophisticated aeroplane to be built before the 19th Century".

Bartolomeu de Gusmão

Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão (December 1685 – 18 November 1724) was a Brazilian-born Portuguese priest and naturalist, who was a pioneer of lighter-than-air airship design.

Early life

Gusmão was born at Santos, then part of the Portugue ...

's "Passarola" was a hollow, vaguely bird-shaped glider of similar concept but with two wings. In 1709, he presented a petition to King John V of Portugal

Dom John V ( pt, João Francisco António José Bento Bernardo; 22 October 1689 – 31 July 1750), known as the Magnanimous (''o Magnânimo'') and the Portuguese Sun King (''o Rei-Sol Português''), was King of Portugal from 9 December 17 ...

, begging for support for his invention of an "airship", in which he expressed the greatest confidence. The public test of the machine, which was set for 24 June 1709, did not take place. According to contemporary reports, however, Gusmão appears to have made several less ambitious experiments with this machine, descending from eminences. It is certain that Gusmão was working on this principle at the public exhibition he gave before the Court on 8 August 1709, in the hall of the Casa da Índia

The Casa da Índia (, English: ''India House'' or ''House of India'') was a Portuguese state-run commercial organization during the Age of Discovery. It regulated international trade and the Portuguese Empire's territories, colonies, and factor ...

in Lisbon, when he propelled a ball to the roof by combustion. He also demonstrated a small airship model before the Portuguese court, but never succeeded with a full-scale model.

Both understanding and a power source were still lacking. This was recognised by Emanuel Swedenborg

Emanuel Swedenborg (, ; born Emanuel Swedberg; 29 March 1772) was a Swedish pluralistic-Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher and mystic. He became best known for his book on the afterlife, ''Heaven and Hell'' (1758).

Swedenborg had a ...

in his " Sketch of a Machine for Flying in the Air" (1716). His flying machine consisted of a light frame covered with strong canvas and provided with two large oars or wings moving on a horizontal axis, arranged so that the upstroke met with no resistance while the downstroke provided lifting power. Swedenborg knew that the machine would not fly, but suggested it as a start and was confident that the problem would be solved. He wrote: "It seems easier to talk of such a machine than to put it into actuality, for it requires greater force and less weight than exists in a human body. The science of mechanics might perhaps suggest a means, namely, a strong spiral spring. If these advantages and requisites are observed, perhaps in time to come some one might know how better to utilize our sketch and cause some addition to be made so as to accomplish that which we can only suggest". The Editor of the Royal Aeronautical Society journal wrote in 1910 that Swedenborg's design was "...the first rational proposal for a flying machine of the aeroplance eavier-than-airtype..."

Meanwhile, rotorcraft were not wholly forgotten. In July 1754, Mikhail Lomonosov demonstrated a small coaxial twin-rotor system, powered by a spring, to the Russian Academy of Sciences. The rotors were arranged one above the other and spun in opposite directions, principles still used in modern twin-rotor designs. In his 1768 ''Théorie de la vis d'Archimède'', Alexis-Jean-Pierre Paucton

Alexis-Jean-Pierre Paucton (1736–1798) was a French mathematician.

1736 births

1798 deaths

18th-century French mathematicians

{{France-mathematician-stub ...

suggested the use of one airscrew for lift and a second for propulsion, nowadays called a gyrodyne

A gyrodyne is a type of VTOL aircraft with a helicopter rotor-like system that is driven by its engine for takeoff and landing only, and includes one or more conventional propeller or jet engines to provide forward thrust during cruising flig ...

. In 1784, Launoy and Bienvenu demonstrated a flying model with coaxial, contra-rotating rotors powered by a simple spring similar to a bow saw

A modern bow saw is a metal-framed crosscut saw in the shape of a bow with a coarse wide blade. This type of saw is also known as a Swede saw, Finn saw or bucksaw. It is a rough tool that can be used for cross-cutting branches or firewood, up t ...

, now accepted as the first powered helicopter.

Attempts at man-powered flight still persisted. Paucton's rotorcraft was man-powered, while another approach, also originally studied by da Vinci, was the use of flap valves. The flap valve is a simple hinged flap over a hole in the wing. In one direction it opens to allow air through and in the other it closes to allow an increased pressure difference. An early example was designed by Bauer in 1764. Later in 1808, Jacob Degen built an ornithopter with flap valves, in which the pilot stood on a rigid frame and worked the wings with a movable horizontal bar. His 1809 attempt at flight failed, so he then added a small hydrogen balloon and the combination achieved some short hops. Popular illustrations of the day depicted his machine without the balloon, leading to confusion as to what had actually flown. In 1811, Albrecht Berblinger built an ornithopter based on Degen's design but omitted the balloon, plunging instead into the Danube. The fiasco did have an upside: George Cayley, also taken in by the illustrations, was spurred to publish his findings to date "for the sake of giving a little more dignity to a subject bordering upon the ludicrous in public estimation", and the modern era of aviation was born.

19th century

Throughout the 19th century, tower jumping was replaced in popularity by the equally-fatal balloon jumping as a way to demonstrate the continued uselessness of man-power and flapping wings. Meanwhile, the scientific study of heavier-than-air flight began in earnest.Sir George Cayley and the first modern aircraft

Sir George Cayley was first called the "father of the aeroplane" in 1846. During the last years of the previous century he had begun the first rigorous study of the physics of flight and would later design the first modern heavier-than-air craft. Among his many achievements, his most important contributions to aeronautics include: *Clarifying our ideas and laying down the principles of heavier-than-air flight. *Reaching a scientific understanding of the principles of bird flight. *Conducting scientific aerodynamic experiments demonstrating drag and streamlining, movement of the centre of pressure, and the increase in lift from curving the wing surface. *Defining the modern aeroplane configuration comprising a fixed-wing, fuselage and tail assembly. *Demonstrations of manned, gliding flight. *Setting out the principles of power-to-weight ratio in sustaining flight. From the age of ten, Cayley began studying the physics ofbird flight

Bird flight is the primary mode of locomotion used by most bird species in which birds take off and fly. Flight assists birds with feeding, breeding, avoiding predators, and migrating.

Bird flight is one of the most complex forms of locomo ...

and his school notebooks contained sketches in which he was developing his ideas on the theories of flight. It has been claimed that these sketches show that Cayley modeled the principles of a lift-generating inclined plane as early as 1792 or 1793.

In 1796, Cayley made a model helicopter of the form commonly known as a Chinese flying top, unaware of Launoy and Bienvenu's model of similar design. He regarded the helicopter as the best design for simple vertical flight, and later in his life in 1854 he made an improved model. He gave a Mr. Cooper credit for being the first person to improve on "the clumsy structure of the toy" and reports Cooper's model as ascending twenty or thirty feet. Cayley made one and a Mr. Coulson made a copy, described by Cayley as "a very beautiful specimen of the screw propeller in the air" and capable of flying over ninety feet high.

Cayley's next innovations were twofold: the adoption of the whirling arm test rig, invented in the previous century by Benjamin Robbins to investigate aerodynamic drag and used soon after by John Smeaton

John Smeaton (8 June 1724 – 28 October 1792) was a British civil engineer responsible for the design of bridges, canals, harbours and lighthouses. He was also a capable mechanical engineer and an eminent physicist. Smeaton was the fi ...

to measure the forces on rotating windmill

A windmill is a structure that converts wind power into rotational energy using vanes called sails or blades, specifically to mill grain (gristmills), but the term is also extended to windpumps, wind turbines, and other applications, in some ...

blades, for use in aircraft research together with the use of aerodynamic models on the arm, rather than attempting to fly a model of a complete design. He initially used a simple flat plane fixed to the arm and inclined at an angle to the airflow.

In 1799, he set down the concept of the modern aeroplane as a fixed-wing

A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air flying machine, such as an airplane, which is capable of flight using wings that generate lift caused by the aircraft's forward airspeed and the shape of the wings. Fixed-wing aircraft are distinct ...

flying machine with separate systems for lift, propulsion, and control. On a small silver disc dated that year, he engraved on one side the forces acting on an aircraft and on the other a sketch of an aircraft design incorporating such modern features as a cambered wing, separate tail comprising a horizontal tailplane

A tailplane, also known as a horizontal stabiliser, is a small lifting surface located on the tail (empennage) behind the main lifting surfaces of a fixed-wing aircraft as well as other non-fixed-wing aircraft such as helicopters and gyropla ...

and vertical fin

A fin is a thin component or appendage attached to a larger body or structure. Fins typically function as foils that produce lift or thrust, or provide the ability to steer or stabilize motion while traveling in water, air, or other fluids. Fin ...

, and fuselage for the pilot suspended below the center of gravity to provide stability. The design is not yet wholly modern, incorporating as it does two pilot-operated paddles or oars which appear to work as flap valves.

He continued his research, and in 1804 constructed a model glider which was the first modern heavier-than-air flying machine, having the layout of a conventional modern aircraft with an inclined wing towards the front and adjustable tail at the back with both tailplane and fin. The wing was just a toy paper kite, flat, and uncambered. A movable weight allowed adjustment of the model's center of gravity. It was "very pretty to see" when flying down a hillside, and sensitive to small adjustments of the tail.

By the end of 1809, he had constructed the world's first full-size glider and flown it as an unmanned tethered kite. In the same year, goaded by the farcical antics of his contemporaries (see above), he began the publication of a landmark three-part treatise titled "On Aerial Navigation" (1809–1810).''Cayley, George''. "On Aerial Navigation

By the end of 1809, he had constructed the world's first full-size glider and flown it as an unmanned tethered kite. In the same year, goaded by the farcical antics of his contemporaries (see above), he began the publication of a landmark three-part treatise titled "On Aerial Navigation" (1809–1810).''Cayley, George''. "On Aerial NavigationPart 1

Part 2

Part 3

''Nicholson's Journal of Natural Philosophy'', 1809–1810. (Via

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil List of government space agencies, space program ...

)Raw text

Retrieved: 30 May 2010. In it he wrote the first scientific statement of the problem, "The whole problem is confined within these limits, viz. to make a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air". He identified the four vector forces that influence an aircraft: ''

thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that sys ...

'', ''lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobil ...

'', '' drag'' and ''weight

In science and engineering, the weight of an object is the force acting on the object due to gravity.

Some standard textbooks define weight as a vector quantity, the gravitational force acting on the object. Others define weight as a scalar qua ...

'' and distinguished stability and control in his designs. He argued that manpower alone was insufficient, and while no suitable power source was yet available he discussed the possibilities and even described the operating principle of the internal combustion engine

An internal combustion engine (ICE or IC engine) is a heat engine in which the combustion of a fuel occurs with an oxidizer (usually air) in a combustion chamber that is an integral part of the working fluid flow circuit. In an internal c ...

using a gas and air mixture. However he was never able to make a working engine and confined his flying experiments to gliding flight. He also identified and described the importance of the cambered aerofoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is the cross-sectional shape of an object whose motion through a gas is capable of generating significant lift, such as a wing, a sail, or the blades of propeller, rotor, or turbine. ...

, dihedral, diagonal bracing and drag reduction, and contributed to the understanding and design of ornithopters and parachutes.

In 1848, he had progressed far enough to construct a glider in the form of a triplane

A triplane is a fixed-wing aircraft equipped with three vertically stacked wing planes. Tailplanes and canard foreplanes are not normally included in this count, although they occasionally are.

Design principles

The triplane arrangement m ...

large and safe enough to carry a child. A local boy was chosen but his name is not known.

He went on to publish the design for a full-size manned glider or "governable parachute" to be launched from a balloon in 1852 and then to construct a version capable of launching from the top of a hill, which carried the first adult aviator across Brompton Dale in 1853. The identity of the aviator is not known. It has been suggested variously as Cayley's coachman, footman or butler, John Appleby who may have been the coachman or another employee, or even Cayley's grandson George John Cayley. What is known is that he was the first to fly in a glider with distinct wings, fuselage and tail, and featuring inherent stability and pilot-operated controls: the first fully modern and functional heavier-than-air craft.

Minor inventions included the rubber-powered motor, which provided a reliable power source for research models. By 1808, he had even re-invented the wheel, devising the tension-spoked wheel

Wire wheels, wire-spoked wheels, tension-spoked wheels, or "suspension" wheels are wheels whose rims connect to their hubs by wire spokes. Although these wires are generally stiffer than a typical wire rope, they function mechanically the same ...

in which all compression loads are carried by the rim, allowing a lightweight undercarriage.Pritchard, J. LaurenceSummary of First Cayley Memorial Lecture at the Brough Branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society

''

Flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be a ...

'' number 2390 volume 66-page 702, 12 November 1954. Retrieved: 29 May 2010. "In thinking of how to construct the lightest possible wheel for aerial navigation cars, an entirely new mode of manufacturing this most useful part of locomotive machines occurred to me: vide, to do away with wooden spokes altogether, and refer the whole firmness of the wheel to the strength of the rim only, by the intervention of tight cording".

The age of steam

Drawing directly from Cayley's work, William Samuel Henson's 1842 design for an aerial steam carriage broke new ground. Henson proposed a span high-winged

Drawing directly from Cayley's work, William Samuel Henson's 1842 design for an aerial steam carriage broke new ground. Henson proposed a span high-winged monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple planes.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing con ...

, with a steam engine driving two pusher configuration propellers. Although only a design, (scale models were built in 1843 or 1848 and flew 10 or 130 feet) it was the first in history for a propeller-driven fixed-wing aircraft. Henson and his collaborator John Stringfellow even dreamed of the first Aerial Transit Company.

In 1856, Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Bris