Eusthenodon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Eusthenodon'' (Greek for “strong-tooth” – ''eustheno''- meaning “strength”, -''odon'' meaning “tooth”) is an extinct

''Eusthenodon'' (Greek for “strong-tooth” – ''eustheno''- meaning “strength”, -''odon'' meaning “tooth”) is an extinct

In his initial diagnosis of the first ''Eusthenodon'' remains published in 1952, Jarvik describes the features present in the remains of ''Eusthenodon wangsjoi'' including those that are significant characters of tristichopterid fishes (referred to as rhizodontids by Jarvik) as well as the traits unique to the described

In his initial diagnosis of the first ''Eusthenodon'' remains published in 1952, Jarvik describes the features present in the remains of ''Eusthenodon wangsjoi'' including those that are significant characters of tristichopterid fishes (referred to as rhizodontids by Jarvik) as well as the traits unique to the described

''Eusthenodon'' (Greek for “strong-tooth” – ''eustheno''- meaning “strength”, -''odon'' meaning “tooth”) is an extinct

''Eusthenodon'' (Greek for “strong-tooth” – ''eustheno''- meaning “strength”, -''odon'' meaning “tooth”) is an extinct genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

of tristichopterid tetrapodomorph

The Tetrapodomorpha (also known as Choanata) are a clade of vertebrates consisting of tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) and their closest sarcopterygian relatives that are more closely related to living tetrapods than to living lungfish. Advance ...

s from the Late Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wher ...

period, ranging between 383 and 359 million years ago (Frasnian

The Frasnian is one of two faunal stages in the Late Devonian Period. It lasted from million years ago to million years ago. It was preceded by the Givetian Stage and followed by the Famennian Stage.

Major reef-building was under way during th ...

to Famennian

The Famennian is the latter of two faunal stages in the Late Devonian Epoch. The most recent estimate for its duration estimates that it lasted from around 371.1 million years ago to 359.3 million years ago. An earlier 2012 estimate, still used b ...

). They are well known for being a cosmopolitan genus with remains being recovered from East Greenland

Tunu, originally Østgrønland ("East Greenland"), was one of the three counties (''amter'') of Greenland until 31 December 2008. The county seat was at the main settlement, Tasiilaq. The county's population in 2005 was around 3,800.

The county ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, Central Russia

Central Russia is, broadly, the various areas in European Russia.

Historically, the area of Central Russia varied based on the purpose for which it is being used. It may, for example, refer to European Russia (except the North Caucasus and ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, and Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

. Compared to the other closely related genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

of the Tristichopteridae clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

, ''Eusthenodon'' was one of the largest lobe-finned fishes

Sarcopterygii (; ) — sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii () — is a taxon (traditionally a class or subclass) of the bony fishes known as the lobe-finned fishes. The group Tetrapoda, a mostly terrestrial superclass includ ...

(approximately 2.5 meters in length) and among the most derived tristichopterids alongside its close relatives ''Cabonnichthys

''Cabonnichthys'' ("Burns' Cabonne fish") is an extinct genus of tristichopterid fish that lived in the Late Devonian period (Famennian

The Famennian is the latter of two faunal stages in the Late Devonian Epoch. The most recent estimate fo ...

'' and ''Mandageria

''Mandageria fairfaxi'' (Pronunciation: Man-daj-ee-ree-a fair-fax-i) is an extinct lobe-finned fish that lived during the Late Devonian period (Frasnian – Famennian). It is related to the much larger ''Hyneria''; although ''Mandageria'' was sma ...

''.

The large size, predatory ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overlaps wi ...

, and evolutionarily derived characters possessed by ''Eusthenodon'' likely contributed to its ability to occupy and flourish in the numerous localities across the world mentioned above. ''Eusthenodon'' is attributed to being just one of many cosmopolitan genera within the "Old Red Sandstone

The Old Red Sandstone is an assemblage of rocks in the North Atlantic region largely of Devonian age. It extends in the east across Great Britain, Ireland and Norway, and in the west along the northeastern seaboard of North America. It also exte ...

" fish faunas of the Upper Devonian. As a result, it has been hypothesized that diversification

Diversification may refer to:

Biology and agriculture

* Genetic divergence, emergence of subpopulations that have accumulated independent genetic changes

* Agricultural diversification involves the re-allocation of some of a farm's resources to n ...

of ''Eusthenodon'' and other morphologically similar tristichopterids were not restricted by biogeographical barriers and were instead limited only by their individual ecologies and mobility.

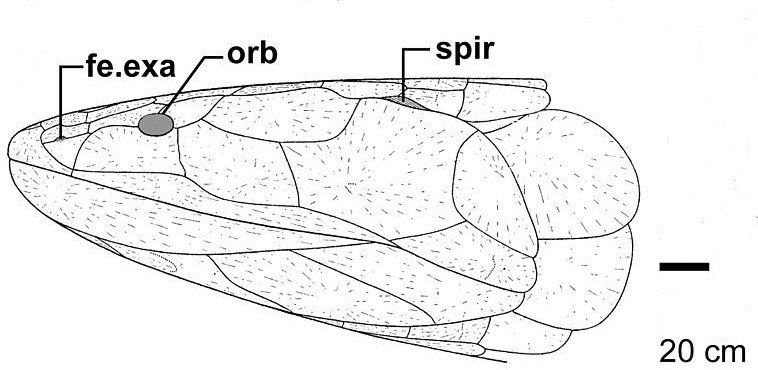

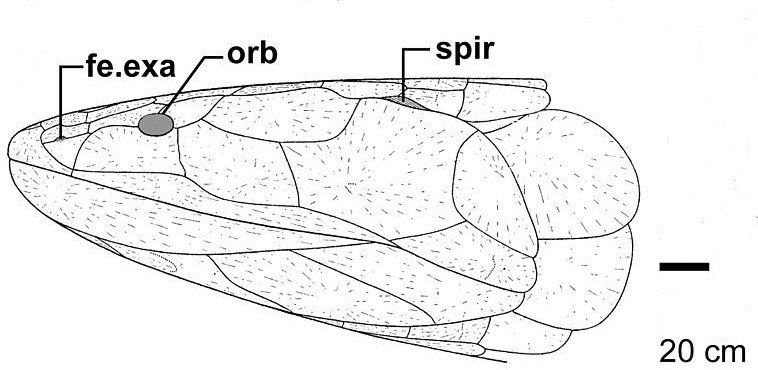

Most of the ''Eusthenodon'' remains found at these globally distributed localities consisted largely of cranial elements and largely not known from complete skeletons. Consequently, the majority of available literature covering ''Eusthenodon'' primarily focus on the intricacies of the bones associated with the skull in order to investigate the genus and while others draw conclusions from the known characters of Tristichopteridae. Johanson & Ahlberg (1997), in their assessment of new sarcopterygian material, present such conclusions proposing ''Eusthenodon'' likely possessed the same trifurcate or diamond-shaped caudal fin with an axial lobe turned slightly dorsally known in other tristichopterids (referred to as eusthenopterids by Johanson) along with a triangular-shaped first dorsal fin.

History and discovery

In 1952, Swedish paleontologistErik Jarvik

Anders Erik Vilhelm Jarvik (30 November 1907 – 11 January 1998) was a Swedish paleontologist who worked extensively on the sarcopterygian (or lobe-finned) fish ''Eusthenopteron''. In a career that spanned some 60 years, Jarvik produced some ...

first described the first species, ''Eusthenodon wangsjoi'' of the genus ''Eusthenodon''. The specimen was retrieved in 1936 from the richly fossiliferous sediments

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand a ...

of the Upper Devonian sequences of East Greenland, a region that gained tremendous attraction by vertebrate paleontologists

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxon, taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with vertebral column, backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the ...

after the discovery of ''Ichthyostega

''Ichthyostega'' (from el, ἰχθῦς , 'fish' and el, στέγη , 'roof') is an extinct genus of limbed tetrapodomorphs from the Late Devonian of Greenland. It was among the earliest four-limbed vertebrates in the fossil record, and was on ...

'', the earliest known tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids (pelycosaurs, extinct theraps ...

. The given name of the genus, ''Eusthenodon'', refers to the distinctly large tusks

Tusks are elongated, continuously growing front teeth that protrude well beyond the mouth of certain mammal species. They are most commonly canine teeth, as with pigs and walruses, or, in the case of elephants, elongated incisors. Tusks share co ...

present in the upper and lower jaws.

Description

Skull

In his initial diagnosis of the first ''Eusthenodon'' remains published in 1952, Jarvik describes the features present in the remains of ''Eusthenodon wangsjoi'' including those that are significant characters of tristichopterid fishes (referred to as rhizodontids by Jarvik) as well as the traits unique to the described

In his initial diagnosis of the first ''Eusthenodon'' remains published in 1952, Jarvik describes the features present in the remains of ''Eusthenodon wangsjoi'' including those that are significant characters of tristichopterid fishes (referred to as rhizodontids by Jarvik) as well as the traits unique to the described species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

and diagnostic characters of the genus. The pointy head of ''Eusthenodon'' is relatively large compared to other closely related ''Osteolepiformes

Osteolepiformes, also known as Osteolepidida, is a group of prehistoric lobe-finned fishes which first appeared during the Devonian period. The order contains the families Canowindridae, Megalichthyidae, Osteolepididae and Tristichopterida ...

'' with short parietal shields that contribute towards its broad snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, rostrum, or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the nose of many mammals is c ...

. The frontoethmoidal shield of the cranial roof in ''Eusthenodon'' is distinctly longer than the parietal shield. The ratio between the lengths of the frontoethmoidal and parietal shields has been used as a diagnostic tool by paleontologists to distinguish between taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

and in some cases, serves as the only distinctive feature separating two groups (as is seen in the separation of the clades ''Eusthenopteron

''Eusthenopteron'' (from el, εὖ , 'good', el, σθένος , 'strength', and el, πτερόν 'wing' or 'fin') is a genus of prehistoric sarcopterygian (often called lobe-finned fishes) which has attained an iconic status from its close ...

'' and ''Tristichopterus

''Tristichopterus'' is a genus of prehistoric lobe-finned fish which lived during the Devonian period. ''Tristichopterus'' belongs to the family Tristichopteridae

Tristichopterids (Tristichopteridae) were a diverse and successful group of te ...

''). Across eusthenopterids (tristichopterids), a trend exists showing increasingly higher values for this ratio in more derived genera with ''Eusthenodon'' possessing the highest value with a frontoethmoidal shield to parietal shield ratio of 2.30. The further expansion of snout length in many tetrapod species may also be further evidence supporting the tendency of increasingly longer frontoethmoidal shields present in subsequent clades closely related to eusthenopterids including the late eopods. The orbital fenestrae housing the small eyes of ''Eusthenodon'' were distinctly smaller in size compared to the size of the larger frontoethmoidal shield. Residing posteriorly to the orbital fenestra, the posterior supraorbital bone extends downwards along the fenestra and comes into contact with lachrymal. In contrast to other ''Osteolepiformes'', which similarly possess a posterior supraorbital bone that extends ventrally

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

along the orbital fenestra, the contact with the lachrymal by the posterior supraorbital bone is a diagnostic character of ''Eusthenodon'' and results in the separation of the jugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

and postorbital bones from meeting the orbital fenestra.

The positions and relative sizes of additional fenestra present in ''Eusthenodon'', including the fenestra exonarina, pineal foramen

A parietal eye, also known as a third eye or pineal eye, is a part of the epithalamus present in some vertebrates. The eye is located at the top of the head, is photoreceptive and is associated with the pineal gland, regulating circadian rhyth ...

, and pineal fenestra are further diagnostic characters of the genus. The triangular pineal fenestra is well known in ''Eusthenodon'' for its large size and the distinctive posterior tail of the fenestra coming near or in-contact to the posterior frontal

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* ''The Front'', 1976 film

Music

* The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and e ...

margin. On the contrary, the pineal foramen is much smaller in size and is positioned distinctively posterior both to the center of radiation of the frontal and the postorbital bone of the frontoethmoidal shield. When viewing the ''Eusthenodon'' skull in dorsal view, the fenestra exonarina can be seen positioned high and laterally in the snout.

Of the three temporal bones that make up the parietal shield present in osteolepiformes ( intertemporal, supratemporal The supratemporal bone is a paired cranial bone present in many tetrapods and tetrapodomorph fish. It is part of the temporal region (the portion of the skull roof behind the eyes), usually lying medial (inwards) relative to the squamosal and latera ...

, and extratemporal), the presence of the extratemporal bone in a ‘postspiracular’ position, defined as the shift of the bone from a position lateral to the supratemporal to a more posterior-lateral position, is a significant and diagnostic character of the Tristichopteridae clade. The extratemporal bone present in ''Eusthenodon'' is notable for its complete postspiracular position resulting in no contact between the supratemporal and extratemporal bones, a condition known only to exist in ''Eusthenodon''. One theory to explain the trend observed in the posterior shift of the extratemporal bone in more derived fishes suggests that the change in head proportions contributed to a more streamlined body shape and enhanced its maneuverability and speed in its aquatic environment.

The external cheek plate is well documented in ''Eusthenodon'' being 3.5 times longer than the parietal shield and 3.0 times as long as it is high. The cheek plate and lower jaw in ''Eusthenodon'' are significantly longer proportionately than in any other ''Osteolepiformes''. ''Eusthenodon'' exhibits a lower jaw that diminishes in height moving from its posterior end to anterior end and is significantly lower in height at its anterior portion.

Dentition

As the name implies, ''Eusthenodon'' has large tusks that protrude from the upper and lower jaws of the skull. Specifically, along the midline of the snout, two large and stout teeth emerge on thepremaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has b ...

. From the incomplete material collected upon the discovery of Eusthenodon, the largest tusks are estimated to have been at least 50 millimeters in length. These two teeth are anteroposteriorly flattened and have distinctive, sharp cutting edges. In a study presented by Gael Clement in 2009, in which a newly discovered tristichopterid assemblage was described, it was found that the enlarged teeth were predominantly in line with the tooth row of the premaxilla and they did not occur in pairs. Consequently, the enlarged premaxillary teeth were described as ‘pseudo fangs’ rather than the true fangs previously thought to be present in ''Eusthenodon''. A horizontal cross-sectionally analysis of the first fang reveals simple and irregularly folded orthodentine. Within the pulp cavity

The pulp is the connective tissue, nerves, blood vessels, and odontoblasts that comprise the innermost layer of a tooth. The pulp's activity and signalling processes regulate its behaviour.

Anatomy

The pulp is the neurovascular bundle cent ...

, osteodentine is found. The presence of the enlarged pseudo fangs on the premaxilla in ''Eusthenodon'', supported its phylogenetic position within the Tristichopteridae clade as similar dentition patterns are found in other closely related derived tristichopterids. The number of small pointed teeth along the tooth row further supports dentition trends over time as in more derived genera, a greater number of teeth are found relative to more primitive species such as ''Eusthenopteron''.

Despite possessing sets of premaxillary pseudo fangs, ''Eusthenodon'' and other large, phylogenetically derived tristichopterids exhibit elaborate anterior dentition and distinctive enlarged dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

fangs. The faintly concave denticulated field of the parasphenoid bone is raised in primitive tristichopterids while it is notably recessed in ''Eusthenodon''. Additionally, the presence of a distinctive blade-like vertical lamina present on the anterior coronoid exists in most other tristichopterids but is absent in derived genera such as ''Eusthenodon''. In tristichopterids, the anterior and middle coronoids carry at least a single fang pair while in ''Eusthenodon'', the posterior coronoid possesses two fang pairs. Furthermore, marginal coronoid teeth are known to be present in practically all other tristichopterids (except the known absence in a single genus, ''Cabonnicthys)'', yet in ''Eusthenodon'' and the closely related ''Mandageria'', there is considerable marginal coronoid teeth missing along the anterior portion of the jaw. This reduction of marginal coronoid teeth supports the phylogenetic association of ''Eusthenodon'', ''Mandageria'', and ''Cabonnichthys'' and serves as a derived characteristic of late tristichopterids. ''Eusthenodon'' possesses a small parasymphysial plate attached to the splenial

The splenial is a small bone in the lower jaw of reptiles, amphibians and birds, usually located on the lingual side (closest to the tongue) between the angular and surangular

The suprangular or surangular is a jaw bone found in most land ver ...

via the small attachment of the plate onto the anterior portion of the mesial lamina. The shape and size of the parasymphysial plate exhibited in ''Eusthenodon'' is present in all tristichopterids and is a diagnostic characteristic of the family.

Scales

In line with the features described by Berg (1955) to be the significant diagnostic characters of Tristichopteridae, ''Eusthenodon'' possesses proportionately large, distinctively round scales withoutcosmine

Cosmine is a spongy, bony material that makes up the dentine-like layers in the scales of the lobe-finned fishes of the class Sarcopterygii. Fish scales that include layers of cosmine are known as cosmoid scales.

Description

As traditionally des ...

that exhibit a reticular pattern of ridges with rare appearance of independent tubercles. Furthermore, each of these round cosmineless scales include a proximal central attachment boss, also diagnostic of Tristichopteridae. In contrast to most other tristichopterids, the ornamentation of ''Eusthenodon'' scales exhibit ridges forming distinct networks whereas scales from ''Eusthenopteron'' tend to have an ornamentation of considerably shorter ridges present in the incompletely fused tubercles. The area of overlap between scales in ''Eusthenodon'' is also larger than the scales of ''Eusthenopteron''.

Classification

''Eusthenodon'' belongs to the family Tristichopteridae, a subdivision of the order Osteolepiformes within the greater class of Sarcopterygii. Sarcopterygii is the major clade that diverted from the ray-finned Actinopterygii with the evolution of lobed-fins. The phylogeny of Tristichopteridae was described by Gael Clement, Daniel Snitting, and P.E. Ahlberg (2008) after performing a maximum parsimony analysis of the interrelationships of within the clade.References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q5414348 Tristichopterids Prehistoric lobe-finned fish genera Devonian fish of Europe Prehistoric fish of Africa Devonian bony fish Fossil taxa described in 1952