Echinoderms And Humans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An echinoderm () is any member of the

File:Ophionereis reticulata 1.jpg, A brittle star, ''

File:EarlyEchinoderms NT.jpg, Early echinoderms ''

Echinoderms possess a unique water vascular system, a network of fluid-filled canals derived from the

Echinoderms possess a unique water vascular system, a network of fluid-filled canals derived from the

Many echinoderms have great powers of

Many echinoderms have great powers of

One species of

One species of

Development begins with a bilaterally symmetrical embryo, with a coeloblastula developing first.

Development begins with a bilaterally symmetrical embryo, with a coeloblastula developing first.

Echinoderms primarily use their tube feet to move about, though some sea urchins also use their spines. The tube feet typically have a tip shaped like a suction pad in which a vacuum can be created by contraction of muscles. This combines with some stickiness from the secretion of

Echinoderms primarily use their tube feet to move about, though some sea urchins also use their spines. The tube feet typically have a tip shaped like a suction pad in which a vacuum can be created by contraction of muscles. This combines with some stickiness from the secretion of  Sea cucumbers are generally sluggish animals. Many can move on the surface of the sea bed or burrow through sand or mud using

Sea cucumbers are generally sluggish animals. Many can move on the surface of the sea bed or burrow through sand or mud using

Despite their low nutrition value and the abundance of indigestible calcite, echinoderms are preyed upon by many organisms, including

Despite their low nutrition value and the abundance of indigestible calcite, echinoderms are preyed upon by many organisms, including

Echinoderms are numerous invertebrates whose adults play an important role in benthic

Echinoderms are numerous invertebrates whose adults play an important role in benthic

In 2019, 129,000 tonnes of echinoderms were harvested. The majority of these were sea cucumbers (158,000 tonnes) and sea urchins (73,000 tonnes). These are used mainly for food, but also in

In 2019, 129,000 tonnes of echinoderms were harvested. The majority of these were sea cucumbers (158,000 tonnes) and sea urchins (73,000 tonnes). These are used mainly for food, but also in

The Echinoid Directory

from the

Echinodermata

from the

Echinoderms of the North Sea

{{Authority control * Extant Cambrian first appearances Marine animals

phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature f ...

Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, take the face of a human being which has a pla ...

, and include starfish

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish ...

, brittle star

Brittle stars, serpent stars, or ophiuroids (; ; referring to the serpent-like arms of the brittle star) are echinoderms in the class Ophiuroidea, closely related to starfish. They crawl across the sea floor using their flexible arms for locomo ...

s, sea urchin

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to . The spherical, hard shells (tests) of ...

s, sand dollar

Sand dollars (also known as a sea cookie or snapper biscuit in New Zealand, or pansy shell in South Africa) are species of flat, burrowing sea urchins belonging to the order Clypeasteroida. Some species within the order, not quite as flat, are ...

s, and sea cucumber

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms from the class Holothuroidea (). They are marine animals with a leathery skin and an elongated body containing a single, branched gonad. Sea cucumbers are found on the sea floor worldwide. The number of holothuria ...

s, as well as the sea lilies

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, which are ...

or "stone lilies". Adult echinoderms are found on the sea bed at every ocean depth, from the intertidal zone

The intertidal zone, also known as the foreshore, is the area above water level at low tide and underwater at high tide (in other words, the area within the tidal range). This area can include several types of habitats with various species o ...

to the abyssal zone

The abyssal zone or abyssopelagic zone is a layer of the pelagic zone of the ocean. "Abyss" derives from the Greek word , meaning bottomless. At depths of , this zone remains in perpetual darkness. It covers 83% of the total area of the ocean a ...

. The phylum contains about 7,000 living species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

, making it the second-largest grouping of deuterostome

Deuterostomia (; in Greek) are animals typically characterized by their anus forming before their mouth during embryonic development. The group's sister clade is Protostomia, animals whose digestive tract development is more varied. Some exampl ...

s, after the chordates

A chordate () is an animal of the phylum Chordata (). All chordates possess, at some point during their larval or adult stages, five synapomorphies, or primary physical characteristics, that distinguish them from all the other taxa. These five ...

. Echinoderms are the largest entirely marine phylum. The first definitive echinoderms appeared near the start of the Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized C with bar, Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million ...

.

The echinoderms are important both ecologically and geologically. Ecologically, there are few other groupings so abundant in the biotic desert of the deep sea

The deep sea is broadly defined as the ocean depth where light begins to fade, at an approximate depth of 200 metres (656 feet) or the point of transition from continental shelves to continental slopes. Conditions within the deep sea are a combin ...

, as well as shallower oceans. Most echinoderms are able to reproduce asexually

Asexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that does not involve the fusion of gametes or change in the number of chromosomes. The offspring that arise by asexual reproduction from either unicellular or multicellular organisms inherit the fu ...

and regenerate tissue, organs, and limbs; in some cases, they can undergo complete regeneration from a single limb. Geologically, the value of echinoderms is in their ossified

Ossification (also called osteogenesis or bone mineralization) in bone remodeling is the process of laying down new bone material by Cell (biology), cells named osteoblasts. It is synonymous with bone tissue formation. There are two processes ...

skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of an animal. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is the stable outer shell of an organism, the endoskeleton, which forms the support structure inside ...

s, which are major contributors to many limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

formations, and can provide valuable clues as to the geological environment. They were the most used species in regenerative research in the 19th and 20th centuries. Further, some scientists hold that the radiation of echinoderms was responsible for the Mesozoic Marine Revolution.

Taxonomy and evolution

The name echinoderm is . Echinoderms arebilateria

The Bilateria or bilaterians are animals with bilateral symmetry as an embryo, i.e. having a left and a right side that are mirror images of each other. This also means they have a head and a tail (anterior-posterior axis) as well as a belly and ...

ns, meaning that their ancestors were mirror-symmetric. Among the bilaterians, they belong to the deuterostome

Deuterostomia (; in Greek) are animals typically characterized by their anus forming before their mouth during embryonic development. The group's sister clade is Protostomia, animals whose digestive tract development is more varied. Some exampl ...

division, meaning that the blastopore

Gastrulation is the stage in the early embryonic development of most animals, during which the blastula (a single-layered hollow sphere of cells), or in mammals the blastocyst is reorganized into a multilayered structure known as the gastrula. Be ...

, the first opening to form during embryo development, becomes the anus

The anus (Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is an opening at the opposite end of an animal's digestive tract from the mouth. Its function is to control the expulsion of feces, the residual semi-solid waste that remains after food digestion, which, d ...

instead of the mouth. The characteristics of adult echinoderms are the possession of a water vascular system

The water vascular system is a hydraulic system used by echinoderms, such as sea stars and sea urchins, for locomotion, food and waste transportation, and respiration. The system is composed of canals connecting numerous tube feet. Echinoderms mov ...

with external tube feet

Tube feet (technically podia) are small active tubular projections on the oral face of an echinoderm, whether the arms of a starfish, or the undersides of sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers; they are more discreet though present on britt ...

and a calcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcareous'' is used as an adje ...

endoskeleton consisting of ossicles

The ossicles (also called auditory ossicles) are three bones in either middle ear that are among the smallest bones in the human body. They serve to transmit sounds from the air to the fluid-filled labyrinth (cochlea). The absence of the auditory ...

connected by a mesh of collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whole ...

fibres.

Phylogeny

Historically, taxonomists believed that the Ophiuroidea were sister to the Asteroidea, or that they were sister to the (Holothuroidea + Echinoidea). However, a 2014 analysis of 219 genes from all classes of echinoderms revised the phylogenetic tree. An independent analysis in 2015 of RNA transcriptomes from 23 species across all classes of echinoderms gave the same tree. ; External phylogeny The context of the echinoderms within the Bilateria is: ; Internal phylogenyDiversity

There are about 7,000extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

species of echinoderm as well as about 13,000 extinct species.

All echinoderms are marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military

* ...

, but they are found in habitats ranging from shallow intertidal areas to abyssal depths. Two main subdivisions are traditionally recognised: the more familiar motile

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy.

Definitions

Motility, the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy, can be contrasted with sessility, the state of organisms th ...

Eleutherozoa

Eleutherozoa is a proposed subphylum of echinoderms. They are mobile animals with the mouth directed towards the substrate. They usually have a madreporite, tube feet, and moveable spines of some sort, and some have Tiedemann's bodies on the rin ...

, which encompasses the Asteroidea (starfish

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish ...

, with some 1,745 species), Ophiuroidea (brittle stars

Brittle stars, serpent stars, or ophiuroids (; ; referring to the serpent-like arms of the brittle star) are echinoderms in the class Ophiuroidea, closely related to starfish. They crawl across the sea floor using their flexible arms for locomot ...

, with around 2,300 species), Echinoidea (sea urchin

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to . The spherical, hard shells (tests) of ...

s and sand dollar

Sand dollars (also known as a sea cookie or snapper biscuit in New Zealand, or pansy shell in South Africa) are species of flat, burrowing sea urchins belonging to the order Clypeasteroida. Some species within the order, not quite as flat, are ...

s, with some 900 species) and Holothuroidea (sea cucumber

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms from the class Holothuroidea (). They are marine animals with a leathery skin and an elongated body containing a single, branched gonad. Sea cucumbers are found on the sea floor worldwide. The number of holothuria ...

s, with about 1,430 species); and the Pelmatozoa

Pelmatozoa was once a clade of Phylum Echinodermata. It included stalked and sedentary echinoderms. The main class of Pelmatozoa were the Crinoidea which includes sea lily and feather star

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Cr ...

, some of which are sessile

Sessility, or sessile, may refer to:

* Sessility (motility), organisms which are not able to move about

* Sessility (botany), flowers or leaves that grow directly from the stem or peduncle of a plant

* Sessility (medicine), tumors and polyps that ...

while others are motile. These consist of the Crinoidea (feather star

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, which are ...

s and sea lilies

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, which are ...

, with around 580 species) and the extinct blastoids and Paracrinoid

Paracrinoidea is an extinct class of blastozoan echinoderms. They lived in shallow seas during the Early Ordovician through the Early Silurian. While blastozoans are usually characterized by types of respiratory structures present, it is not clea ...

s.

Ophionereis reticulata

''Ophionereis reticulata'', the reticulated brittle star, is a brittle star in the family Ophionereididae. It is found in shallow parts of the western Atlantic, Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico.

Description

Like other brittle stars, ''Ophionerei ...

''

File:Sea cucumber at Pulau Redang.jpg, A sea cucumber

Sea cucumbers are echinoderms from the class Holothuroidea (). They are marine animals with a leathery skin and an elongated body containing a single, branched gonad. Sea cucumbers are found on the sea floor worldwide. The number of holothuria ...

from Malaysia

File:Nerr0878.jpg, Starfish of varied colours

File:Strongylocentrotus purpuratus 1.jpg, A sea urchin, ''Strongylocentrotus purpuratus

''Strongylocentrotus purpuratus'', the purple sea urchin, lives along the eastern edge of the Pacific Ocean extending from Ensenada, Mexico, to British Columbia, Canada. This sea urchin species is deep purple in color, and lives in lower in ...

''

File:Crinoid on the reef of Batu Moncho Island.JPG, Crinoid

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, which are ...

on a coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in groups.

Co ...

Fossil history

The oldest candidate echinodermfossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

is ''Arkarua

''Arkarua adami'' is a small, Precambrian disk-like fossil with a raised center, a number of radial ridges on the rim, and a five-pointed central depression marked with radial lines of five small dots from the middle of the disk center. Fossils ...

'' from the Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of the ...

of Australia. These fossils are disc-like, with radial ridges on the rim and a five-pointed central depression marked with radial lines. However, the fossils have no stereom

Stereom is a calcium carbonate material that makes up the internal skeletons found in all echinoderms, both living and fossilized forms. It is a sponge-like porous structure which, in a sea urchin may be 50% by volume living cells, and the rest b ...

or internal structure indicating a water vascular system, so they cannot be conclusively identified.

The first universally accepted echinoderms appear in the Lower Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago (m ...

period; asterozoans appeared in the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and System (geology), system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era (geology), Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start ...

, while the crinoids were a dominant group in the Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

. Echinoderms left behind an extensive fossil record. It is hypothesised that the ancestor of all echinoderms was a simple, motile, bilaterally symmetrical animal with a mouth, gut and anus. This ancestral organism adopted an attached mode of life with suspension feeding, and developed radial symmetry. Even so, the larvae of all echinoderms are bilaterally symmetrical, and all develop radial symmetry at metamorphosis. Like their ancestor, the starfish and crinoids still attach themselves to the seabed while changing to their adult form.

The first echinoderms were non-motile, but evolved into animals able to move freely. These soon developed endoskeletal plates with stereom structure, and external ciliary grooves for feeding. The Paleozoic echinoderms were globular, attached to the substrate and were orientated with their oral surfaces facing upwards. These early echinoderms had ambulacral groove

Ambulacral is a term typically used in the context of anatomical parts of the phylum Echinodermata or class Asteroidea and Edrioasteroidea. Echinoderms can have ambulacral parts that include ossicles, plates, spines, and suckers. For example, sea ...

s extending down the side of the body, fringed on either side by brachioles, like the pinnules of a modern crinoid. Eventually, except for the crinoids, all the classes of echinoderms reversed their orientation to become mouth-downward. Before this happened, the podia probably had a feeding function, as they do in the crinoids today. The locomotor function of the podia came later, when the re-orientation of the mouth brought the podia into contact with the substrate for the first time.

:Further information: ''Dibrachicystis

''Dibrachicystis'' is an extinct genus of rhombiferan echinoderm from the early Middle Cambrian (Miaolingian, Wuliuan, about 510 Ma). It is a stalked echinoderm within the family Dibrachicystidae which lived in what is now northernmost Iberian ...

''

Ctenoimbricata

''Ctenoimbricata'' is an extinct genus of bilaterally symmetrical echinoderm, which lived during the early Middle Cambrian period of what is now Spain. It contains one species, ''Ctenoimbricata spinosa''. It may be the most basal known echinoderm ...

'', '' Ctenocystis'', ''Gogia

''Gogia'' is a genus of primitive eocrinoid blastozoan from the early to middle Cambrian.

''G. ojenai'' dates to the late Early Cambrian; other species come from various Middle Cambrian strata throughout North America, but the genus has yet to ...

'', '' Protocintus'' and '' Rhenocystis''

File:Echinosphaerites.JPG, The Ordovician cystoid ''Echinosphaerites

''Echinosphaerites'' is a genus of rhombiferan cystoid echinoderms that lived in the Early to Middle Ordovician of North America and Europe (Bockelie, 1981).

Biology

Echinosphaerites had branched biserial brachioles which is rare for species ...

'' from northeastern Estonia

File:fossile-seelilie.jpg, Fossil crinoid

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, which are ...

crowns

File:Hyperoblastus.jpg, Calyx of ''Hyperoblastus'', a blastoid

Blastoids (class Blastoidea) are an extinct type of stemmed echinoderm, often referred to as sea buds. They first appear, along with many other echinoderm classes, in the Ordovician period, and reached their greatest diversity in the Mississi ...

from the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, whe ...

of Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

Anatomy and physiology

Echinoderms evolved from animals withbilateral symmetry

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, take the face of a human being which has a pla ...

. Although adult echinoderms possess pentaradial symmetry, their larvae are cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike projecti ...

ted, free-swimming organisms with bilateral symmetry. Later, during metamorphosis, the left side of the body grows at the expense of the right side, which is eventually absorbed. The left side then grows in a pentaradially symmetric fashion, in which the body is arranged in five parts around a central axis. Within the Asterozoa

The Asterozoa are a subphylum in the phylum Echinodermata. Characteristics include a star-shaped body and radially divergent axes of symmetry. The subphylum includes the class Asteroidea (the starfish), the class Ophiuroidea (the brittle stars ...

, there can be a few exceptions from the rule. Most starfish in the genus ''Leptasterias

''Leptasterias'' is a genus of starfish in the family Asteriidae. Members of this genus are characterised by having six arms although five-armed specimens sometimes occur. ''L. muelleri'' is the type species. The taxonomy of the genus is confus ...

'' have six arms, although five-armed individuals can occur. The Brisingida

The Brisingids are deep-sea-dwelling starfish in the order Brisingida.

Description

These starfish have between 6 to 18 long, attenuated arms which they use for suspension feeding. Other characteristics include a single series of marginals, a f ...

too contain some six-armed species. Amongst the brittle stars, six-armed species such as ''Ophiothela danae'', ''Ophiactis savignyi

''Ophiactis savignyi'' is a species of brittle star in the family Ophiactidae, commonly known as Savigny's brittle star or the little brittle star. It occurs in the tropical and subtropical parts of all the world's oceans and is thought to be th ...

'', and ''Ophionotus hexactis'' exists, and ''Ophiacantha vivipara'' often has more than six.

Echinoderms have secondary radial symmetry in portions of their body at some stage of life, most likely an adaptation to a sessile or slow-moving existence. Many crinoids and some seastars are symmetrical in multiples of the basic five; starfish such as ''Labidiaster annulatus

''Labidiaster annulatus'', the Antarctic sun starfish or wolftrap starfish is a species of starfish in the family Heliasteridae. It is found in the cold waters around Antarctica and has a large number of slender, flexible rays.

Description

'' ...

'' possess up to fifty arms, while the sea-lily

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, which are ...

''Comaster schlegelii

''Comaster schlegelii'', the variable bushy feather star, is a crinoid in the family Comatulidae. It was previously classified as ''Comanthina schlegeli'' but further research showed that it was better placed in the genus ''Comaster''. It is fou ...

'' has two hundred.

Skin and skeleton

Echinoderms have amesoderm

The mesoderm is the middle layer of the three germ layers that develops during gastrulation in the very early development of the embryo of most animals. The outer layer is the ectoderm, and the inner layer is the endoderm.Langman's Medical E ...

al skeleton in the dermis, composed of calcite

Calcite is a Carbonate minerals, carbonate mineral and the most stable Polymorphism (materials science), polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on ...

-based plates known as ossicles

The ossicles (also called auditory ossicles) are three bones in either middle ear that are among the smallest bones in the human body. They serve to transmit sounds from the air to the fluid-filled labyrinth (cochlea). The absence of the auditory ...

. If solid, these would form a heavy skeleton, so they have a sponge-like porous structure known as stereom. Ossicles may be fused together, as in the test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

of sea urchins, or may articulate to form flexible joints as in the arms of sea stars, brittle stars and crinoids. The ossicles may bear external projections in the form of spines, granules or warts and they are supported by a tough epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the amount of water rele ...

. Skeletal elements are sometimes deployed in specialized ways, such as the chewing organ called "Aristotle's lantern

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to . The spherical, hard shells (tests) of ...

" in sea urchins, the supportive stalks of crinoids, and the structural "lime ring" of sea cucumbers.

Although individual ossicles are robust and fossilize readily, complete skeletons of starfish, brittle stars and crinoids are rare in the fossil record. On the other hand, sea urchins are often well preserved in chalk beds or limestone. During fossilization, the cavities in the stereom are filled in with calcite that is continuous with the surrounding rock. On fracturing such rock, paleontologists

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

can observe distinctive cleavage patterns and sometimes even the intricate internal and external structure of the test.

The epidermis contains pigment cells that provide the often vivid colours of echinoderms, which include deep red, stripes of black and white, and intense purple. These cells may be light-sensitive, causing many echinoderms to change appearance completely as night falls. The reaction can happen quickly: the sea urchin ''Centrostephanus longispinus

''Centrostephanus longispinus'', the hatpin urchin, is a species of sea urchin in the family Diadematidae. There are two subspecies, ''Centrostephanus l. longispinus'', found in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea and ''Centrostephanus l ...

'' changes colour in just fifty minutes when exposed to light.

One characteristic of most echinoderms is a special kind of tissue known as catch connective tissue Catch connective tissue (also called mutable collagenous tissue) is a kind of connective tissue found in echinoderms (such as starfish and sea cucumbers) which can change its mechanical properties in a few seconds or minutes through nervous contr ...

. This collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whole ...

-based material can change its mechanical properties under nervous control rather than by muscular means. This tissue enables a starfish to go from moving flexibly around the seabed to becoming rigid while prying open a bivalve mollusc or preventing itself from being extracted from a crevice. Similarly, sea urchins can lock their normally mobile spines upright as a defensive mechanism when attacked.

The water vascular system

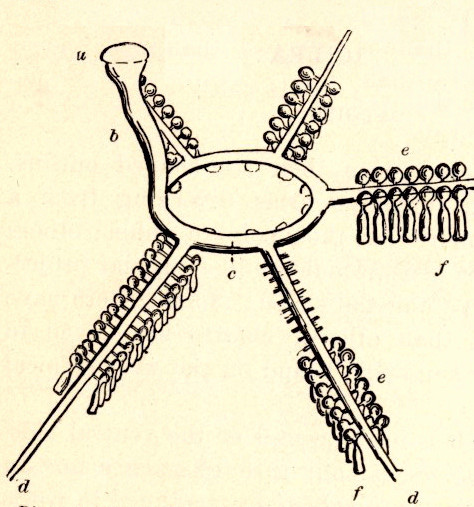

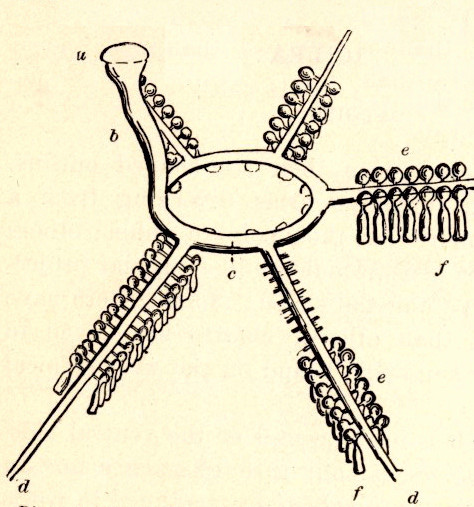

Echinoderms possess a unique water vascular system, a network of fluid-filled canals derived from the

Echinoderms possess a unique water vascular system, a network of fluid-filled canals derived from the coelom

The coelom (or celom) is the main body cavity in most animals and is positioned inside the body to surround and contain the digestive tract and other organs. In some animals, it is lined with mesothelium. In other animals, such as molluscs, it r ...

(body cavity) that function in gas exchange, feeding, sensory reception and locomotion. This system varies between different classes of echinoderm but typically opens to the exterior through a sieve-like madreporite

The madreporite is a light colored calcareous opening used to filter water into the water vascular system of echinoderms. It acts like a pressure-equalizing valve. It is visible as a small red or yellow button-like structure, looking like a smal ...

on the aboral (upper) surface of the animal. The madreporite is linked to a slender duct, the stone canal, which extends to a ring canal that encircles the mouth or oesophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the ...

. The ring canal branches into a set of radial canals, which in asteroids extend along the arms, and in echinoids adjoin the test in the ambulacral areas. Short lateral canals branch off the radial canals, each one ending in an ampulla. Part of the ampulla can protrude through a pore (or a pair of pores in sea urchins) to the exterior, forming a podium or tube foot

Tube feet (technically podia) are small active tubular projections on the oral face of an echinoderm, whether the arms of a starfish, or the undersides of sea urchins, sand dollars and sea cucumbers; they are more discreet though present on britt ...

. The water vascular system assists with the distribution of nutrients throughout the animal's body; it is most visible in the tube feet which can be extended or contracted by the redistribution of fluid between the foot and the internal ampulla.

The organisation of the water vascular system is somewhat different in ophiuroids, where the madreporite may be on the oral surface and the podia lack suckers. In holothuroids, the system is reduced, often with few tube feet other than the specialised feeding tentacles, and the madreporite opens on to the coelom. Some holothuroids like the Apodida lack tube feet and canals along the body; others have longitudinal canals. The arrangements in crinoids is similar to that in asteroids, but the tube feet lack suckers and are used in a back-and-forth wafting motion to pass food particles captured by the arms towards the central mouth. In the asteroids, the same motion is employed to move the animal across the ground.

Other organs

Echinoderms possess a simple digestive system which varies according to the animal's diet. Starfish are mostly carnivorous and have a mouth, oesophagus, two-part stomach, intestine and rectum, with the anus located in the centre of the aboral body surface. With a few exceptions, the members of the orderPaxillosida

The Paxillosida are a large order (biology), order of sea stars.

Characteristics

Paxillosida adults lack an anus and have no suckers on their tube feet. They do not develop the brachiolaria stage in their early development.Matsubara, M., Komatsu ...

do not possess an anus. In many species of starfish, the large cardiac stomach can be everted to digest food outside the body. Some other species are able to ingest whole food items such as mollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

s. Brittle stars, which have varying diets, have a blind gut with no intestine or anus; they expel food waste

Food loss and waste is food that is not eaten. The causes of food waste or loss are numerous and occur throughout the food system, during production, processing, distribution, retail and food service sales, and consumption. Overall, about o ...

through their mouth. Sea urchins are herbivores and use their specialised mouthparts to graze, tear and chew their food, mainly algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular mic ...

. They have an oesophagus, a large stomach and a rectum with the anus at the apex of the test. Sea cucumbers are mostly detritivore

Detritivores (also known as detrivores, detritophages, detritus feeders, or detritus eaters) are heterotrophs that obtain nutrients by consuming detritus (decomposing plant and animal parts as well as feces). There are many kinds of invertebrates, ...

s, sorting through the sediment with modified tube feet around their mouth, the buccal tentacles. Sand and mud accompanies their food through their simple gut, which has a long coiled intestine and a large cloaca

In animal anatomy, a cloaca ( ), plural cloacae ( or ), is the posterior orifice that serves as the only opening for the digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts (if present) of many vertebrate animals. All amphibians, reptiles and birds, a ...

. Crinoids are suspension feeder

Filter feeders are a sub-group of suspension feeding animals that feed by straining suspended matter and food particles from water, typically by passing the water over a specialized filtering structure. Some animals that use this method of feedin ...

s, passively catching plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) that are unable to propel themselves against a Ocean current, current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankt ...

which drift into their outstretched arms. Boluses of mucus-trapped food are passed to the mouth, which is linked to the anus by a loop consisting of a short oesophagus and longer intestine.

The coelomic cavities of echinoderms are complex. Aside from the water vascular system, echinoderms have a haemal coelom, a perivisceral

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a ...

coelom, a gonad

A gonad, sex gland, or reproductive gland is a mixed gland that produces the gametes and sex hormones of an organism. Female reproductive cells are egg cells, and male reproductive cells are sperm. The male gonad, the testicle, produces sper ...

al coelom and often also a perihaemal coelom. During development, echinoderm coelom is divided into the metacoel, mesocoel and protocoel (also called somatocoel, hydrocoel and axocoel, respectively). The water vascular system, haemal system and perihaemal system form the tubular coelomic system. Echinoderms are unusual in having both a coelomic circulatory system (the water vascular system) and a haemal circulatory system, as most groups of animals have just one of the two.

Haemal and perihaemal systems are derived from the original coelom, forming an open

Open or OPEN may refer to:

Music

* Open (band), Australian pop/rock band

* The Open (band), English indie rock band

* ''Open'' (Blues Image album), 1969

* ''Open'' (Gotthard album), 1999

* ''Open'' (Cowboy Junkies album), 2001

* ''Open'' (YF ...

and reduced circulatory system. This usually consists of a central ring and five radial vessels. There is no true heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide t ...

, and the blood often lacks any respiratory pigment. Gaseous exchange occurs via dermal branchiae or papulae in starfish, genital bursae in brittle stars, peristominal gills in sea urchins and cloacal trees in sea cucumbers. Exchange of gases also takes place through the tube feet. Echinoderms lack specialized excretory (waste disposal) organs and so nitrogenous waste

Metabolic wastes or excrements are substances left over from metabolic processes (such as cellular respiration) which cannot be used by the organism (they are surplus or toxic), and must therefore be excreted. This includes nitrogen compounds, w ...

, chiefly in the form of ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

, diffuses out through the respiratory surfaces.

The coelomic fluid contains the coelomocyte A coelomocyte () is a phagocytic leukocyte that appears in the bodies of animals that have a coelom. In most, it attacks and digests invading organisms such as bacteria and viruses through encapsulation and phagocytosis, though in some animals (e.g. ...

s, or immune cells. There are several types of immune cells, which vary among classes and species. All classes possess a type of phagocytic

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ...

amebocyte, which engulf invading particles and infected cells, aggregate or clot, and may be involved in cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity is the quality of being toxic to cells. Examples of toxic agents are an immune cell or some types of venom, e.g. from the puff adder (''Bitis arietans'') or brown recluse spider (''Loxosceles reclusa'').

Cell physiology

Treating cells ...

. These cells are usually large and granular, and are believed to be a main line of defense against potential pathogens. Depending on the class, echinoderms may have spherule

A sphere () is a geometrical object that is a three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the set of points that are all at the same distance from a given point in three-dimensional space.. That given point is the ce ...

cells (for cytotoxicity, inflammation, and anti-bacterial activity), vibratile cells (for coelomic fluid movement and clotting), and crystal cells (which may serve for osmoregulation

Osmoregulation is the active regulation of the osmotic pressure of an organism's body fluids, detected by osmoreceptors, to maintain the homeostasis of the organism's water content; that is, it maintains the fluid balance and the concentration o ...

in sea cucumbers). The coelomocytes secrete antimicrobial peptides

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), also called host defence peptides (HDPs) are part of the innate immune response found among all classes of life. Fundamental differences exist between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells that may represent targets for a ...

against bacteria, and have a set of lectin

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins that are highly specific for sugar groups that are part of other molecules, so cause agglutination of particular cells or precipitation of glycoconjugates and polysaccharides. Lectins have a role in rec ...

s and complement proteins

The complement system, also known as complement cascade, is a part of the immune system that enhances (complements) the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear microbes and damaged cells from an organism, promote inflammation, and a ...

as part of an innate immune system

The innate, or nonspecific, immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies (the other being the adaptive immune system) in vertebrates. The innate immune system is an older evolutionary defense strategy, relatively speaking, and is the ...

that is still being characterised.

Echinoderms have a simple radial nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes th ...

that consists of a modified nerve net

A nerve net consists of interconnected neurons lacking a brain or any form of cephalization. While organisms with bilateral body symmetry are normally associated with a condensation of neurons or, in more advanced forms, a central nervous syst ...

of interconnecting neurons with no central brain

A brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It is located in the head, usually close to the sensory organs for senses such as vision. It is the most complex organ in a v ...

, although some do possess ganglia

A ganglion is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system there are both sympatheti ...

. Nerves radiate from central rings around the mouth into each arm or along the body wall; the branches of these nerves coordinate the movements of the organism and the synchronisation of the tube feet. Starfish have sensory cells in the epithelium and have simple eyespots and touch-sensitive tentacle-like tube feet at the tips of their arms. Sea urchins have no particular sense organs but do have statocyst

The statocyst is a balance sensory receptor present in some aquatic invertebrates, including bivalves, cnidarians, ctenophorans, echinoderms, cephalopods, and crustaceans. A similar structure is also found in ''Xenoturbella''. The statocyst cons ...

s that assist in gravitational orientation, and they have sensory cells in their epidermis, particularly in the tube feet, spines and pedicellariae

A pedicellaria (plural: pedicellariae) is a small wrench- or claw-shaped appendage with movable jaws, called valves, commonly found on echinoderms (phylum Echinodermata), particularly in sea stars (class Asteroidea) and sea urchins (class Echinoi ...

. Brittle stars, crinoids and sea cucumbers in general do not have sensory organs, but some burrowing sea cucumbers of the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

Apodida

Apodida is an order of littoral to deep-sea, largely infaunal holothurians, sea cucumbers. This order comprises three families, 32 genera and about 270 known species, called apodids, "without feet".

Characteristics

These sea cucumbers are vagil ...

have a single statocyst adjoining each radial nerve, and some have an eyespot at the base of each tentacle.

The gonad

A gonad, sex gland, or reproductive gland is a mixed gland that produces the gametes and sex hormones of an organism. Female reproductive cells are egg cells, and male reproductive cells are sperm. The male gonad, the testicle, produces sper ...

s at least periodically occupy much of the body cavities of sea urchins and sea cucumbers, while the less voluminous crinoids, brittle stars and starfish have two gonads in each arm. While the ancestors of modern echinoderms are believed to have had one genital aperture, many organisms have multiple gonopore

A gonopore, sometimes called a gonadopore, is a genital pore in many invertebrates. Hexapods, including insects have a single common gonopore, except mayflies, which have a pair of gonopores. More specifically, in the unmodified female it is the ...

s through which eggs or sperm may be released.

Regeneration

Many echinoderms have great powers of

Many echinoderms have great powers of regeneration

Regeneration may refer to:

Science and technology

* Regeneration (biology), the ability to recreate lost or damaged cells, tissues, organs and limbs

* Regeneration (ecology), the ability of ecosystems to regenerate biomass, using photosynthesis

...

. Many species routinely autotomize and regenerate arms and viscera

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a ...

. Sea cucumbers often discharge parts of their internal organs if they perceive themselves to be threatened, regenerating them over the course of several months. Sea urchins constantly replace spines lost through damage, while sea stars and sea lilies readily lose and regenerate their arms. In most cases, a single severed arm cannot grow into a new starfish in the absence of at least part of the disc.See last paragraph in review above Analysis However, in a few species a single arm can survive and develop into a complete individual, and arms are sometimes intentionally detached for the purpose of asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that does not involve the fusion of gametes or change in the number of chromosomes. The offspring that arise by asexual reproduction from either unicellular or multicellular organisms inherit the fu ...

. During periods when they have lost their digestive tracts, sea cucumbers live off stored nutrients and absorb dissolved organic matter directly from the water.

The regeneration of lost parts involves both epimorphosis

Epimorphosis is defined as the regeneration of a specific part of an organism in a way that involves extensive cell proliferation of somatic stem cells, dedifferentiation, and reformation, as well as blastema formation. Epimorphosis can be cons ...

and morphallaxis Morphallaxis is the regeneration of specific tissue in a variety of organisms due to loss or death of the existing tissue. The word comes from the Greek ''allazein,'' (αλλάζειν) which means ''to change.''

The classical example of morphall ...

. In epimorphosis stem cells—either from a reserve pool or those produced by dedifferentiation

Dedifferentiation (pronounced dē-ˌdi-fə-ˌren-chē-ˈā-shən) is a transient process by which cells become less specialized and return to an earlier cell state within the same lineage. This suggests an increase in a cell potency, meaning that a ...

—form a blastema

A blastema (Greek ''βλάστημα'', "offspring") is a mass of cells capable of growth and regeneration into organs or body parts. The changing definition of the word "blastema" has been reviewed by Holland (2021). A broad survey of how blast ...

and generate new tissues. Morphallactic regeneration involves the movement and remodelling of existing tissues to replace lost parts. Direct transdifferentiation

Transdifferentiation, also known as lineage reprogramming, is the process in which one mature somatic cell is transformed into another mature somatic cell without undergoing an intermediate pluripotent state or progenitor cell type. It is a type ...

of one type of tissue to another during tissue replacement is also observed.

Reproduction

Sexual reproduction

Echinoderms become sexually mature after approximately two to three years, depending on the species and the environmental conditions. Almost all species have separate male and female sexes, though some arehermaphroditic

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite () is an organism that has both kinds of reproductive organs and can produce both gametes associated with male and female sexes.

Many taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrates) do not have separ ...

. The eggs and sperm cells are typically released into open water, where fertilisation takes place. The release of sperm and eggs is synchronised in some species, usually with regard to the lunar cycle. In other species, individuals may aggregate during the reproductive season, increasing the likelihood of successful fertilisation. Internal fertilisation has been observed in three species of sea star, three brittle stars and a deep water sea cucumber. Even at abyssal depths, where no light penetrates, echinoderms often synchronise their reproductive activity.

Some echinoderms brood their eggs. This is especially common in cold water species where planktonic larvae might not be able to find sufficient food. These retained eggs are usually few in number and are supplied with large yolks to nourish the developing embryos. In starfish, the female may carry the eggs in special pouches, under her arms, under her arched body, or even in her cardiac stomach. Many brittle stars are hermaphrodites; they often brood their eggs, usually in special chambers on their oral surfaces, but sometimes in the ovary or coelom. In these starfish and brittle stars, development is usually direct to the adult form, without passing through a bilateral larval stage. A few sea urchins and one species of sand dollar carry their eggs in cavities, or near their anus, holding them in place with their spines. Some sea cucumbers use their buccal tentacles to transfer their eggs to their underside or back, where they are retained. In a very small number of species, the eggs are retained in the coelom where they develop viviparously, later emerging through ruptures in the body wall. In some crinoids, the embryos develop in special breeding bags, where the eggs are held until sperm released by a male happens to find them.

Asexual reproduction

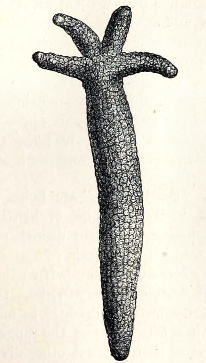

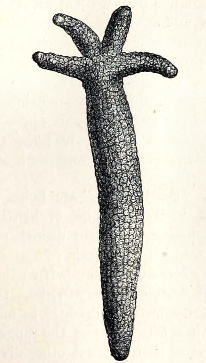

One species of

One species of seastar

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish ...

, '' Ophidiaster granifer'', reproduces asexually by parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek grc, παρθένος, translit=parthénos, lit=virgin, label=none + grc, γένεσις, translit=génesis, lit=creation, label=none) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which growth and development ...

. In certain other asterozoa

The Asterozoa are a subphylum in the phylum Echinodermata. Characteristics include a star-shaped body and radially divergent axes of symmetry. The subphylum includes the class Asteroidea (the starfish), the class Ophiuroidea (the brittle stars ...

ns, adults reproduce asexually until they mature, then reproduce sexually. In most of these species, asexual reproduction is by transverse fission Strobilisation or transverse fission is a form of asexual reproduction consisting of the spontaneous transverse segmentation of the body. It is observed in certain cnidarians and helminths. This mode of reproduction is characterized by high offspr ...

with the disc splitting in two. Both the lost disc area and the missing arms regrow, so an individual may have arms of varying lengths. During the period of regrowth, they have a few tiny arms and one large arm, and are thus often known as "comets".

Adult sea cucumbers reproduce asexually by transverse fission. ''Holothuria parvula

''Holothuria parvula'', the golden sea cucumber, is a species of echinoderm in the class Holothuroidea. It was first described by Emil Selenka in 1867 and has since been placed in the subgenus ''Platyperona'', making its full scientific name ''Ho ...

'' uses this method frequently, splitting into two a little in front of the midpoint. The two halves each regenerate their missing organs over a period of several months, but the missing genital organs are often very slow to develop.

The larvae of some echinoderms are capable of asexual reproduction. This has long been known to occur among starfish and brittle stars, but has more recently been observed in a sea cucumber, a sand dollar and a sea urchin. This may be by autotomising parts that develop into secondary larvae, by budding

Budding or blastogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction in which a new organism develops from an outgrowth or bud due to cell division at one particular site. For example, the small bulb-like projection coming out from the yeast cell is know ...

, or by splitting transversely. Autotomised parts or buds may develop directly into fully formed larvae, or may pass through a gastrula

Gastrulation is the stage in the early embryonic development of most animals, during which the blastula (a single-layered hollow sphere of Cell (biology), cells), or in mammals the blastocyst is reorganized into a multilayered structure known as ...

or even a blastula

Blastulation is the stage in early animal embryonic development that produces the blastula. In mammalian development the blastula develops into the blastocyst with a differentiated inner cell mass and an outer trophectoderm. The blastula (from ...

stage. New larvae can develop from the preoral hood (a mound like structure above the mouth), the side body wall, the postero-lateral arms, or their rear ends.

Cloning is costly to the larva both in resources and in development time. Larvae undergo this process when food is plentiful or temperature conditions are optimal. Cloning may occur to make use of the tissues that are normally lost during metamorphosis. The larvae of some sand dollars clone themselves when they detect dissolved fish mucus, indicating the presence of predators. Asexual reproduction produces many smaller larvae that escape better from planktivorous fish, implying that the mechanism may be an anti-predator adaptation.

Larval development

Development begins with a bilaterally symmetrical embryo, with a coeloblastula developing first.

Development begins with a bilaterally symmetrical embryo, with a coeloblastula developing first. Gastrulation

Gastrulation is the stage in the early embryonic development of most animals, during which the blastula (a single-layered hollow sphere of cells), or in mammals the blastocyst is reorganized into a multilayered structure known as the gastrula. Be ...

marks the opening of the "second mouth" that places echinoderms within the deuterostomes, and the mesoderm, which will host the skeleton, migrates inwards. The secondary body cavity, the coelom, forms by the partitioning of three body cavities. The larvae are often plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) that are unable to propel themselves against a Ocean current, current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankt ...

ic, but in some species the eggs are retained inside the female, while in some the female broods the larvae.

The larvae pass through several stages, which have specific names derived from the taxonomic names of the adults or from their appearance. For example, a sea urchin has an 'echinopluteus' larva while a brittle star has an 'ophiopluteus' larva. A starfish has a 'bipinnaria A bipinnaria is the first stage in the larval development of most starfish, and is usually followed by a brachiolaria stage. Movement and feeding is accomplished by the bands of cilia. Starfish that brood their young generally lack a bipinnaria s ...

' larva, which develops into a multi-armed 'brachiolaria

A brachiolaria is the second stage of larval development in many starfishes. It follows the bipinnaria. Brachiolaria have bilateral symmetry, unlike the adult starfish, which have a pentaradial symmetry. Starfish of the order Paxillosida (''Astrope ...

' larva. A sea cucumber's larva is an 'auricularia' while a crinoid's is a 'vitellaria'. All these larvae are bilaterally symmetrical

Symmetry in biology refers to the symmetry observed in organisms, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria. External symmetry can be easily seen by just looking at an organism. For example, take the face of a human being which has a pla ...

and have bands of cilia with which they swim; some, usually known as 'pluteus' larvae, have arms. When fully developed they settle on the seabed to undergo metamorphosis, and the larval arms and gut degenerate. The left hand side of the larva develops into the oral surface of the juvenile, while the right side becomes the aboral surface. At this stage the pentaradial symmetry develops.

A plankton-eating larva, living and feeding in the water column, is considered to be the ancestral larval type for echinoderms, but in extant echinoderms, some 68% of species develop using a yolk-feeding larva. The provision of a yolk-sac means that smaller numbers of eggs are produced, the larvae have a shorter development period and a smaller dispersal potential, but a greater chance of survival.

Distribution and habitat

Echinoderms are globally distributed in almost all depths, latitudes and environments in the ocean. Adults are mainlybenthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from ancient Greek, βένθος (bénthos), meaning "t ...

, living on the seabed, whereas larvae are often pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

, living as plankton in the open ocean. Some holothuroid adults such as ''Pelagothuria

''Pelagothuria'' is a genus of sea cucumbers in the family Pelagothuriidae. It is monotypic, being represented by the single species ''Pelagothuria natatrix''.

Characteristics

This sea cucumber is somewhat unusual in appearance in comparison ...

'' are however pelagic. Some crinoids are pseudo-planktonic, attaching themselves to floating logs and debris, although this behaviour was exercised most extensively in the Paleozoic, before competition from organisms such as barnacles restricted the extent of the behaviour.

Mode of life

Locomotion

mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It is ...

to provide adhesion. The tube feet contract and relax in waves which move along the adherent surface, and the animal moves slowly along.

Brittle stars are the most agile of the echinoderms. Any one of the arms can form the axis of symmetry, pointing either forwards or back. The animal then moves in a co-ordinated way, propelled by the other four arms. During locomotion, the propelling arms can made either snake-like or rowing movements. Starfish move using their tube feet, keeping their arms almost still, including in genera like '' Pycnopodia'' where the arms are flexible. The oral surface is covered with thousands of tube feet which move out of time with each other, but not in a metachronal rhythm

A metachronal rhythm or metachronal wave refers to wavy movements produced by the sequential action (as opposed to synchronized) of structures such as cilia, segments of worms, or legs. These movements produce the appearance of a travelling wave. ...

; in some way, however, the tube feet are coordinated, as the animal glides steadily along. Some burrowing starfish have points rather than suckers on their tube feet and they are able to "glide" across the seabed at a faster rate.

Sea urchins use their tube feet to move around in a similar way to starfish. Some also use their articulated spines to push or lever themselves along or lift their oral surfaces off the substrate. If a sea urchin is overturned, it can extend its tube feet in one ambulacral area far enough to bring them within reach of the substrate and then successively attach feet from the adjoining area until it is righted. Some species bore into rock, usually by grinding away at the surface with their mouthparts.

Sea cucumbers are generally sluggish animals. Many can move on the surface of the sea bed or burrow through sand or mud using

Sea cucumbers are generally sluggish animals. Many can move on the surface of the sea bed or burrow through sand or mud using peristaltic

Peristalsis ( , ) is a radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an anterograde direction. Peristalsis is progression of coordinated contraction of involuntary circular muscles, which ...

movements; some have short tube feet on their under surface with which they can creep along in the manner of a starfish. Some species drag themselves along using their buccal tentacles, while others manage to swim with peristaltic movements or rhythmic flexing. Many live in cracks, hollows and burrows and hardly move at all. Some deep water species are pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

and can float in the water with webbed papillae forming sails or fins.

The majority of crinoids are motile, but sea lilies are sessile and attached to hard substrates by stalks. Movement in most sea lilies is limited to bending their stems can bend and rolling and unrolling their arms; a few species can relocate themselves on the seabed by crawling. The sea feathers are unattached and usually live in crevices, under corals or inside sponges with their arms the only visible part. Some sea feathers emerge at night and perch themselves on nearby eminences to better exploit food-bearing currents. Many species can "walk" across the seabed, raising their body with the help of their arms, or swim using their arms. Most species of sea feather, however, are largely sedentary, seldom moving far from their chosen place of concealment.

Feeding

The modes of feeding vary greatly between the different echinoderm taxa. Crinoids and some brittle stars tend to be passive filter-feeders, enmeshing suspended particles from passing water. Most sea urchins are grazers; sea cucumbers are deposit feeders; and the majority of starfish are active hunters. Crinoids catch food particles using the tube feet on their outspread pinnules, move them into the ambulacral grooves, wrap them in mucus, and convey them to the mouth using the cilia lining the grooves. The exact dietary requirements of crinoids have been little researched, but in the laboratory they can be fed with diatoms.Basket star

The Euryalida are an order of brittle stars, which includes large species with either branching arms (called "basket stars") or long and curling arms (called "snake stars").

Characteristics

Many of the species in this order have characteristi ...

s are suspension feeders, raising their branched arms to collect zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

, while other brittle stars use several methods of feeding. Some are suspension feeders, securing food particles with mucus strands, spines or tube feet on their raised arms. Others are scavengers and detritus feeders. Others again are voracious carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

s and able to lasso their waterborne prey with a sudden encirclement by their flexible arms. The limbs then bend under the disc to transfer the food to the jaws and mouth.

Many sea urchins feed on algae, often scraping off the thin layer of algae covering the surfaces of rocks with their specialised mouthparts known as Aristotle's lantern. Other species devour smaller organisms, which they may catch with their tube feet. They may also feed on dead fish and other animal matter. Sand dollars may perform suspension feeding and feed on phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), meaning 'wanderer' or 'drifter'.

Ph ...

, detritus, algal pieces and the bacterial layer surrounding grains of sand.

Sea cucumbers are often mobile deposit or suspension feeders, using their buccal podia to actively capture food and then stuffing the particles individually into their buccal cavities. Others ingest large quantities of sediment, absorb the organic matter and pass the indigestible mineral particles through their guts. In this way they disturb and process large volumes of substrate, often leaving characteristic ridges of sediment on the sea bed. Some sea cucumbers live infaunally in burrows, anterior-end down and anus on the surface, swallowing sediment and passing it through their gut. Other burrowers live anterior-end up and wait for detritus to fall into the entrances of the burrows or rake in debris from the surface nearby with their buccal podia.

Nearly all starfish are detritus feeders or carnivores, though a few are suspension feeders. Small fish landing on the upper surface may be captured by pedicilaria and dead animal matter may be scavenged but the main prey items are living invertebrates, mostly bivalve molluscs. To feed on one of these, the starfish moves over it, attaches its tube feet and exerts pressure on the valves by arching its back. When a small gap between the valves is formed, the starfish inserts part of its stomach into the prey, excretes digestive enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s and slowly liquefies the soft body parts. As the adductor muscle A adductor muscle is any muscle that causes adduction. It may refer to:

Humans

* Adductor muscles of the hip, the most common reference in humans, but may also refer to

** Adductor brevis muscle, a muscle in the thigh situated immediately behind ...

of the bivalve relaxes, more stomach is inserted and when digestion is complete, the stomach is returned to its usual position in the starfish with its now liquefied bivalve meal inside it. Other starfish evert the stomach to feed on sponges, sea anemones, corals, detritus and algal films.

Antipredator defence

Despite their low nutrition value and the abundance of indigestible calcite, echinoderms are preyed upon by many organisms, including

Despite their low nutrition value and the abundance of indigestible calcite, echinoderms are preyed upon by many organisms, including bony fish

Osteichthyes (), popularly referred to as the bony fish, is a diverse superclass of fish that have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue. They can be contrasted with the Chondrichthyes, which have skeletons primarily composed of cartilag ...

, shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachimo ...

s, eider duck

Eiders () are large seaducks in the genus ''Somateria''. The three extant species all breed in the cooler latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

The down feathers of eider ducks, and some other ducks and geese, are used to fill pillows and quilt ...

s, gull

Gulls, or colloquially seagulls, are seabirds of the family Laridae in the suborder Lari. They are most closely related to the terns and skimmers and only distantly related to auks, and even more distantly to waders. Until the 21st century, m ...

s, crab

Crabs are decapod crustaceans of the infraorder Brachyura, which typically have a very short projecting "tail" (abdomen) ( el, βραχύς , translit=brachys = short, / = tail), usually hidden entirely under the thorax. They live in all the ...

s, gastropod molluscs, other echinoderms, sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of the weasel family, but among the small ...

s, Arctic fox

The Arctic fox (''Vulpes lagopus''), also known as the white fox, polar fox, or snow fox, is a small fox native to the Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere and common throughout the Arctic tundra biome. It is well adapted to living in co ...

es and humans. Larger starfish prey on smaller ones; the great quantity of eggs and larva that they produce form part of the zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

, consumed by many marine creatures. Crinoids, on the other hand, are relatively free from predation.

Antipredator defence

Anti-predator adaptations are mechanisms developed through evolution that assist prey organisms in their constant struggle against predators. Throughout the animal kingdom, adaptations have evolved for every stage of this struggle, namely by avo ...

s include the presence of spines, toxins (inherent or delivered through the tube feet), and the discharge of sticky entangling threads by sea cucumbers. Although most echinoderm spines are blunt, those of the crown-of-thorns starfish

The crown-of-thorns starfish (frequently abbreviated to COTS), ''Acanthaster planci'', is a large starfish that preys upon hard, or stony, coral polyps (Scleractinia). The crown-of-thorns starfish receives its name from venomous thorn-like spine ...

are long and sharp and can cause a painful puncture wound as the epithelium covering them contains a toxin. Because of their catch connective tissue, which can change rapidly from a flaccid to a rigid state, echinoderms are very difficult to dislodge from crevices. Some sea cucumbers have a cluster of cuvierian tubules

Cuvierian tubules are clusters of fine tubes located at the base of the respiratory tree in some sea cucumbers in the genera '' Bohadschia'', ''Holothuria'' and '' Pearsonothuria'', all of which are included in the family Holothuriidae. The tubule ...

which can be ejected as long sticky threads from their anus to entangle and permanently disable an attacker. Sea cucumbers occasionally defend themselves by rupturing their body wall and discharging the gut and internal organs. Starfish and brittle stars may undergo autotomy

Autotomy (from the Greek language, Greek ''auto-'', "self-" and ''tome'', "severing", wikt:αὐτοτομία, αὐτοτομία) or self-amputation, is the behaviour whereby an animal sheds or discards one or more of its own appendages, usual ...

when attacked, detaching an arm; this may distract the predator for long enough for the animal to escape. Some starfish species can swim away from danger.

Ecology

ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

s, while the larvae are a major component of the plankton. Among the ecological roles of adults are the grazing of sea urchins, the sediment processing of heart urchins, and the suspension and deposit feeding of crinoids and sea cucumbers. Some sea urchins can bore into solid rock, destabilising rock faces and releasing nutrients into the ocean. Coral reefs are also bored into in this way, but the rate of accretion of carbonate material is often greater than the erosion produced by the sea urchin. Echinoderms sequester about 0.1 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide per year as calcium carbonate, making them important contributors in the global carbon cycle

The carbon cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and Earth's atmosphere, atmosphere of the Earth. Carbon is the main component of biological compounds as well as ...

.

Echinoderms sometimes have large population swings which can transform ecosystems. In 1983, for example, the mass mortality of the tropical sea urchin ''Diadema antillarum

''Diadema antillarum'', also known as the lime urchin, black sea urchin, or the long-spined sea urchin, is a species of sea urchin in the family Diadematidae.

This sea urchin is characterized by its exceptionally long black spines.

It is the ...