Ebola Virus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Zaire ebolavirus'', more commonly known as Ebola virus (; EBOV), is one of six known species within the

EBOV carries a negative-sense RNA genome in virions that are cylindrical/tubular, and contain

EBOV carries a negative-sense RNA genome in virions that are cylindrical/tubular, and contain

It was found that 472 nucleotides from the 3' end and 731 nucleotides from the 5' end are sufficient for replication of a viral "minigenome", though not sufficient for infection. Virus sequencing from 78 patients with confirmed Ebola virus disease, representing more than 70% of cases diagnosed in Sierra Leone from late May to mid-June 2014, provided evidence that the 2014 outbreak was no longer being fed by new contacts with its natural reservoir. Using third-generation sequencing technology, investigators were able to sequence samples as quickly as 48 hours. Like other RNA viruses, Ebola virus mutates rapidly, both within a person during the progression of disease and in the reservoir among the local human population. The observed mutation rate of 2.0 x 10−3 substitutions per site per year is as fast as that of seasonal

It was found that 472 nucleotides from the 3' end and 731 nucleotides from the 5' end are sufficient for replication of a viral "minigenome", though not sufficient for infection. Virus sequencing from 78 patients with confirmed Ebola virus disease, representing more than 70% of cases diagnosed in Sierra Leone from late May to mid-June 2014, provided evidence that the 2014 outbreak was no longer being fed by new contacts with its natural reservoir. Using third-generation sequencing technology, investigators were able to sequence samples as quickly as 48 hours. Like other RNA viruses, Ebola virus mutates rapidly, both within a person during the progression of disease and in the reservoir among the local human population. The observed mutation rate of 2.0 x 10−3 substitutions per site per year is as fast as that of seasonal

There are two candidates for host cell entry proteins. The first is a cholesterol transporter protein, the host-encoded Niemann–Pick C1 (

There are two candidates for host cell entry proteins. The first is a cholesterol transporter protein, the host-encoded Niemann–Pick C1 (

Being acellular, viruses such as Ebola do not replicate through any type of cell division; rather, they use a combination of host- and virally encoded enzymes, alongside host cell structures, to produce multiple copies of themselves. These then self-assemble into viral macromolecular structures in the host cell. The virus completes a set of steps when infecting each individual cell. The virus begins its attack by attaching to host receptors through the glycoprotein (GP) surface peplomer and is endocytosed into macropinosomes in the host cell. To penetrate the cell, the viral membrane fuses with

Being acellular, viruses such as Ebola do not replicate through any type of cell division; rather, they use a combination of host- and virally encoded enzymes, alongside host cell structures, to produce multiple copies of themselves. These then self-assemble into viral macromolecular structures in the host cell. The virus completes a set of steps when infecting each individual cell. The virus begins its attack by attaching to host receptors through the glycoprotein (GP) surface peplomer and is endocytosed into macropinosomes in the host cell. To penetrate the cell, the viral membrane fuses with

Ebola virus was first identified as a possible new "strain" of Marburg virus in 1976. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) identifies Ebola virus as

Ebola virus was first identified as a possible new "strain" of Marburg virus in 1976. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) identifies Ebola virus as

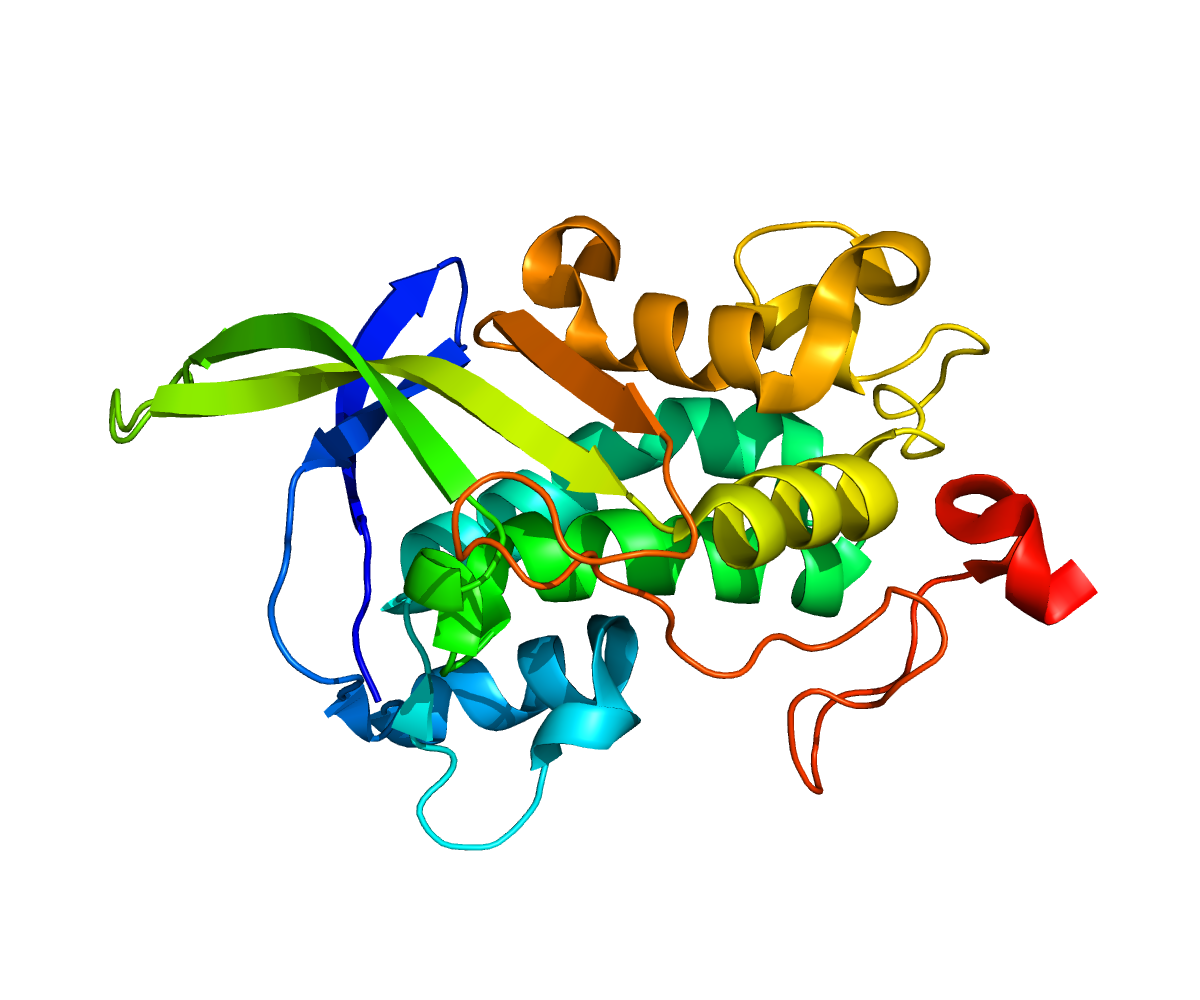

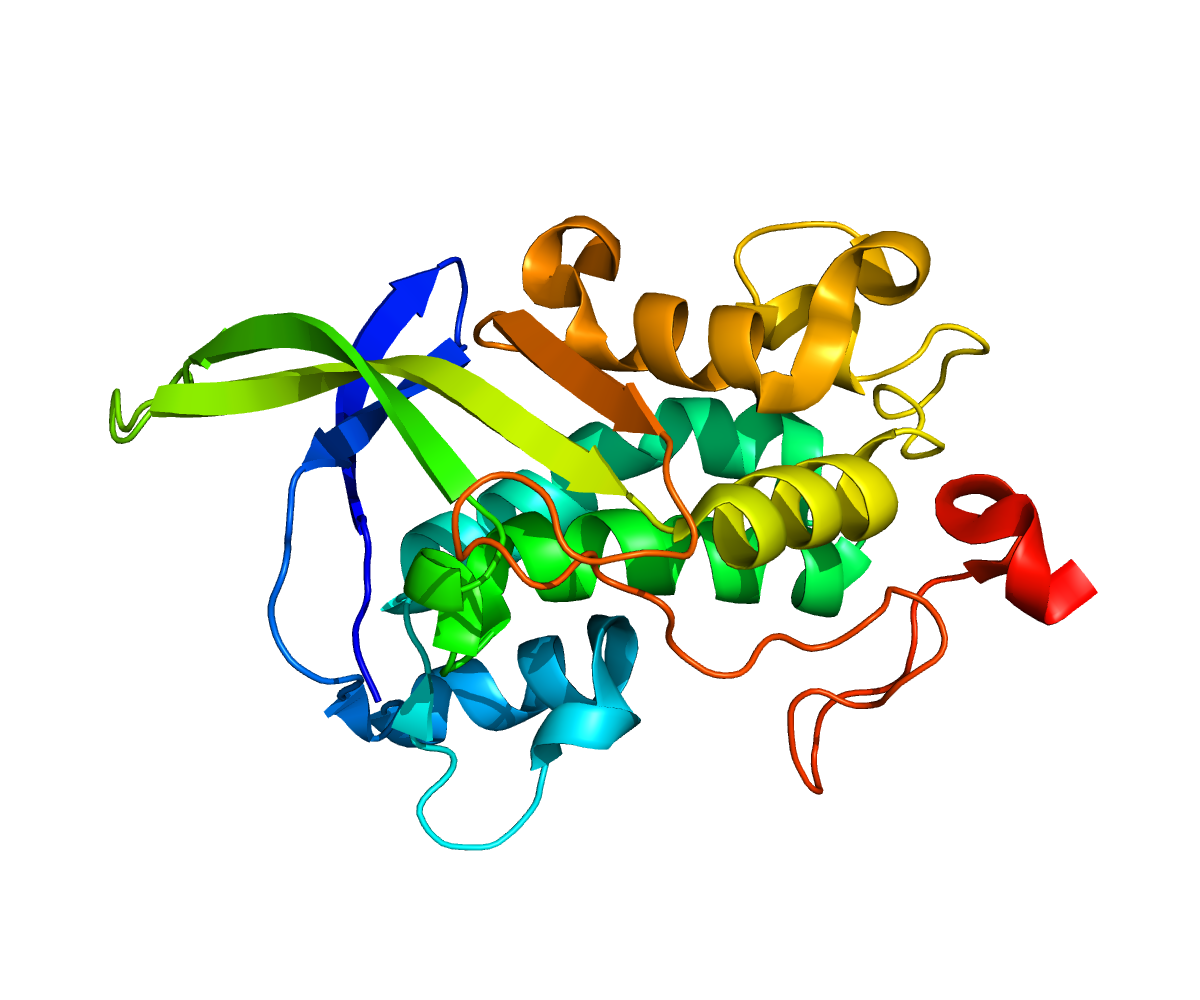

Ebolavirus molecular biology

Ebolavirus proteins (PDB-101)

ICTV Files and DiscussionsDiscussion forum and file distribution for the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

Genomic data on ''Ebola'' virus isolates and other members of the family ''Filoviridae''

– Virological repository from the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics

Virus Pathogen Resource: Ebola Portal

– Genomic and other research data about Ebola and other human pathogenic viruses

The Ebola Virus

3D model of the Ebola virus, prepared by Visual Science, Moscow.

FILOVIRscientific resources for research on filoviruses

* * {{Use dmy dates, date=April 2017 Primate diseases Biological weapons Ebolaviruses Tropical diseases Zoonoses Ebola 1976 in biology Animal viral diseases Arthropod-borne viral fevers and viral haemorrhagic fevers Hemorrhagic fevers Virus-related cutaneous conditions

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial n ...

'' Ebolavirus''. Four of the six known ebolaviruses, including EBOV, cause a severe and often fatal hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of animal and human illnesses in which fever and hemorrhage are caused by a viral infection. VHFs may be caused by five distinct families of RNA viruses: the families '' Filoviridae'', '' ...

in human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

s and other mammals

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fu ...

, known as Ebola virus disease (EVD). Ebola virus has caused the majority of human deaths from EVD, and was the cause of the 2013–2016 epidemic in western Africa, which resulted in at least suspected cases and confirmed deaths.

Ebola virus and its genus were both originally named for Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

), the country where it was first described, and was at first suspected to be a new "strain" of the closely related Marburg virus. The virus was renamed "Ebola virus" in 2010 to avoid confusion. Ebola virus is the single member of the species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

''Zaire ebolavirus'', which is assigned to the genus '' Ebolavirus'', family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

'' Filoviridae'', order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

'' Mononegavirales''. The members of the species are called Zaire ebolaviruses. The natural reservoir of Ebola virus is believed to be bats, particularly fruit bats, and it is primarily transmitted between humans and from animals to humans through body fluid

Body fluids, bodily fluids, or biofluids, sometimes body liquids, are liquids within the human body. In lean healthy adult men, the total body water is about 60% (60–67%) of the total body weight; it is usually slightly lower in women (52-55%) ...

s.

The EBOV genome is a single-stranded RNA, approximately 19,000 nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecul ...

s long. It encodes seven structural protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

s: nucleoprotein (NP), polymerase cofactor (VP35), (VP40), GP, transcription activator (VP30), VP24, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) or RNA replicase is an enzyme that catalyzes the replication of RNA from an RNA template. Specifically, it catalyzes synthesis of the RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template. This is in contrast to t ...

(L).

Because of its high fatality rate (up to 83 to 90 percent), EBOV is also listed as a select agent, World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level o ...

Risk Group 4 Pathogen (requiring Biosafety Level 4-equivalent containment), a US National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health, commonly referred to as NIH (with each letter pronounced individually), is the primary agency of the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U ...

/ National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Category A Priority Pathogen, US CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the national public health agency of the United States. It is a United States federal agency, under the Department of Health and Human Services, and is headquartered in Atlanta, Georg ...

Category A Bioterrorism Agent, and a Biological Agent for Export Control by the Australia Group.

Structure

EBOV carries a negative-sense RNA genome in virions that are cylindrical/tubular, and contain

EBOV carries a negative-sense RNA genome in virions that are cylindrical/tubular, and contain viral envelope

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes.

Numerous human pathogenic viruses in circulation are encase ...

, matrix, and nucleocapsid components. The overall cylinders are generally approximately 80 nm in diameter, and have a virally encoded glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as g ...

(GP) projecting as 7–10 nm long spikes from its lipid bilayer surface. The cylinders are of variable length, typically 800 nm, but sometimes up to 1000 nm long. The outer viral envelope

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes.

Numerous human pathogenic viruses in circulation are encase ...

of the virion is derived by budding from domains of host cell membrane into which the GP spikes have been inserted during their biosynthesis. Individual GP molecules appear with spacings of about 10 nm. Viral proteins VP40

In molecular biology, VP40 is the name of a viral matrix protein. Most commonly it is found in the ''Ebola virus'' (EBOV), a type of non-segmented, negative-strand RNA virus. Ebola virus causes a severe and often fatal haemorrhagic fever in hu ...

and VP24 are located between the envelope and the nucleocapsid (see following), in the ''matrix space''. At the center of the virion structure is the nucleocapsid, which is composed of a series of viral proteins attached to an 18–19 kb linear, negative-sense RNA without 3′-polyadenylation

Polyadenylation is the addition of a poly(A) tail to an RNA transcript, typically a messenger RNA (mRNA). The poly(A) tail consists of multiple adenosine monophosphates; in other words, it is a stretch of RNA that has only adenine bases. In eu ...

or 5′-capping (see following); the RNA is helically wound and complexed with the NP, VP35, VP30, and L proteins; this helix has a diameter of 80 nm.

The overall shape of the virions after purification and visualization (e.g., by ultracentrifugation and electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a ...

, respectively) varies considerably; simple cylinders are far less prevalent than structures showing reversed direction, branches, and loops (e.g., U-, shepherd's crook

A shepherd's crook is a long and sturdy stick with a hook at one end, often with the point flared outwards, used by a shepherd to manage and sometimes catch sheep. In addition, the crook may aid in defending against attack by predators. Wh ...

-, 9-, or eye bolt

An eye bolt is a bolt with a loop at one end. They are used to firmly attach a securing eye to a structure, so that ropes or cables may then be tied to it.

Eye bolts

Machinery eye bolts are fully threaded and may have a collar, making them sui ...

-shapes, or other or circular/coiled appearances), the origin of which may be in the laboratory techniques applied. The characteristic "threadlike" structure is, however, a more general morphologic characteristic of filoviruses (alongside their GP-decorated viral envelope, RNA nucleocapsid, etc.).

Genome

Each virion contains one molecule of linear, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA, 18,959 to 18,961 nucleotides in length. The 3′ terminus is not polyadenylated and the 5′ end is not capped. This viral genome codes for seven structural proteins and one non-structural protein. The gene order is 3′ – leader – NP – VP35 – VP40 – GP/sGP – VP30 – VP24 – L – trailer – 5′; with the leader and trailer being non-transcribed regions, which carry important signals to control transcription, replication, and packaging of the viral genomes into new virions. Sections of the NP, VP35 and the L genes from filoviruses have been identified as endogenous in the genomes of several groups of small mammals. It was found that 472 nucleotides from the 3' end and 731 nucleotides from the 5' end are sufficient for replication of a viral "minigenome", though not sufficient for infection. Virus sequencing from 78 patients with confirmed Ebola virus disease, representing more than 70% of cases diagnosed in Sierra Leone from late May to mid-June 2014, provided evidence that the 2014 outbreak was no longer being fed by new contacts with its natural reservoir. Using third-generation sequencing technology, investigators were able to sequence samples as quickly as 48 hours. Like other RNA viruses, Ebola virus mutates rapidly, both within a person during the progression of disease and in the reservoir among the local human population. The observed mutation rate of 2.0 x 10−3 substitutions per site per year is as fast as that of seasonal

It was found that 472 nucleotides from the 3' end and 731 nucleotides from the 5' end are sufficient for replication of a viral "minigenome", though not sufficient for infection. Virus sequencing from 78 patients with confirmed Ebola virus disease, representing more than 70% of cases diagnosed in Sierra Leone from late May to mid-June 2014, provided evidence that the 2014 outbreak was no longer being fed by new contacts with its natural reservoir. Using third-generation sequencing technology, investigators were able to sequence samples as quickly as 48 hours. Like other RNA viruses, Ebola virus mutates rapidly, both within a person during the progression of disease and in the reservoir among the local human population. The observed mutation rate of 2.0 x 10−3 substitutions per site per year is as fast as that of seasonal influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

.

Entry

There are two candidates for host cell entry proteins. The first is a cholesterol transporter protein, the host-encoded Niemann–Pick C1 (

There are two candidates for host cell entry proteins. The first is a cholesterol transporter protein, the host-encoded Niemann–Pick C1 (NPC1

Niemann-Pick disease, type C1 (NPC1) is a disease of a membrane protein that mediates intracellular cholesterol trafficking in mammals. In humans the protein is encoded by the ''NPC1'' gene (chromosome location 18q11).

Function

NPC1 was identi ...

), which appears to be essential for entry of Ebola virions into the host cell and for its ultimate replication.

*

* In one study, mice with one copy of the NPC1 gene removed showed an 80 percent survival rate fifteen days after exposure to mouse-adapted Ebola virus, while only 10 percent of unmodified mice survived this long. In another study, small molecule

Within the fields of molecular biology and pharmacology, a small molecule or micromolecule is a low molecular weight (≤ 1000 daltons) organic compound that may regulate a biological process, with a size on the order of 1 nm. Many drugs are ...

s were shown to inhibit Ebola virus infection by preventing viral envelope

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes.

Numerous human pathogenic viruses in circulation are encase ...

glycoprotein (GP) from binding to NPC1. Hence, NPC1 was shown to be critical to entry of this filovirus

''Filoviridae'' () is a family of single-stranded negative-sense RNA viruses in the order ''Mononegavirales''. Two members of the family that are commonly known are Ebola virus and Marburg virus. Both viruses, and some of their lesser known rela ...

, because it mediates infection by binding directly to viral GP.

When cells from Niemann–Pick Type C individuals lacking this transporter were exposed to Ebola virus in the laboratory, the cells survived and appeared impervious to the virus, further indicating that Ebola relies on NPC1 to enter cells; mutations in the NPC1 gene in humans were conjectured as a possible mode to make some individuals resistant to this deadly viral disease. The same studies described similar results regarding NPC1's role in virus entry for Marburg virus, a related filovirus

''Filoviridae'' () is a family of single-stranded negative-sense RNA viruses in the order ''Mononegavirales''. Two members of the family that are commonly known are Ebola virus and Marburg virus. Both viruses, and some of their lesser known rela ...

. A further study has also presented evidence that NPC1 is the critical receptor mediating Ebola infection via its direct binding to the viral GP, and that it is the second "lysosomal" domain of NPC1 that mediates this binding.

The second candidate is TIM-1 (a.k.a. HAVCR1). TIM-1 was shown to bind to the receptor binding domain of the EBOV glycoprotein, to increase the receptivity of Vero cells

Vero may refer to: Geography

* Vero Beach, Florida, a city in the United States

* Vero, Corse-du-Sud, a commune of France in Corsica Other

* ''Véro'', a talk show on the Radio-Canada television network

* Vero (app), a social media company co-fou ...

. Silencing its effect with siRNA prevented infection of Vero cells

Vero may refer to: Geography

* Vero Beach, Florida, a city in the United States

* Vero, Corse-du-Sud, a commune of France in Corsica Other

* ''Véro'', a talk show on the Radio-Canada television network

* Vero (app), a social media company co-fou ...

. TIM1 is expressed in tissues known to be seriously impacted by EBOV lysis (trachea, cornea, and conjunctiva). A monoclonal antibody against the IgV domain of TIM-1, ARD5, blocked EBOV binding and infection. Together, these studies suggest NPC1 and TIM-1 may be potential therapeutic targets for an Ebola anti-viral drug and as a basis for a rapid field diagnostic assay.

Replication

Being acellular, viruses such as Ebola do not replicate through any type of cell division; rather, they use a combination of host- and virally encoded enzymes, alongside host cell structures, to produce multiple copies of themselves. These then self-assemble into viral macromolecular structures in the host cell. The virus completes a set of steps when infecting each individual cell. The virus begins its attack by attaching to host receptors through the glycoprotein (GP) surface peplomer and is endocytosed into macropinosomes in the host cell. To penetrate the cell, the viral membrane fuses with

Being acellular, viruses such as Ebola do not replicate through any type of cell division; rather, they use a combination of host- and virally encoded enzymes, alongside host cell structures, to produce multiple copies of themselves. These then self-assemble into viral macromolecular structures in the host cell. The virus completes a set of steps when infecting each individual cell. The virus begins its attack by attaching to host receptors through the glycoprotein (GP) surface peplomer and is endocytosed into macropinosomes in the host cell. To penetrate the cell, the viral membrane fuses with vesicle

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features ...

membrane, and the nucleocapsid is released into the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. ...

. Encapsidated, negative-sense genomic ssRNA is used as a template for the synthesis (3'–5') of polyadenylated, monocistronic mRNAs and, using the host cell's ribosomes, tRNA molecules, etc., the mRNA is translated into individual viral proteins.

These viral proteins are processed: a glycoprotein precursor (GP0) is cleaved to GP1 and GP2, which are then heavily glycosylated using cellular enzymes and substrates. These two molecules assemble, first into heterodimers, and then into trimers to give the surface peplomers. Secreted glycoprotein (sGP) precursor is cleaved to sGP and delta peptide, both of which are released from the cell. As viral protein levels rise, a switch occurs from translation to replication. Using the negative-sense genomic RNA as a template, a complementary +ssRNA is synthesized; this is then used as a template for the synthesis of new genomic (-)ssRNA, which is rapidly encapsidated. The newly formed nucleocapsids and envelope proteins associate at the host cell's plasma membrane; budding

Budding or blastogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction in which a new organism develops from an outgrowth or bud due to cell division at one particular site. For example, the small bulb-like projection coming out from the yeast cell is kno ...

occurs, destroying the cell.

Ecology

Ebola virus is a zoonotic pathogen. Intermediary hosts have been reported to be "various species of fruit bats ... throughout central and sub-Saharan Africa". Evidence of infection in bats has been detected through molecular and serologic means. However, ebolaviruses have not been isolated in bats. End hosts are humans and great apes, infected through bat contact or through other end hosts. Pigs in the Philippines have been reported to be infected with Reston virus, so other interim or amplifying hosts may exist. Ebola virus outbreaks tend to occur when temperatures are lower and humidity is higher than usual for Africa. Even after a person recovers from the acute phase of the disease, Ebola virus survives for months in certain organs such as the eyes and testes.Ebola virus disease

Zaire ebolavirus is one of the four ebolaviruses known to cause disease in humans. It has the highest case-fatality rate of these ebolaviruses, averaging 83 percent since the first outbreaks in 1976, although a fatality rate of up to 90 percent was recorded in one outbreak in the Republic of the Congo between December 2002 and April 2003. There have also been more outbreaks of Zaire ebolavirus than of any other ebolavirus. The first outbreak occurred on 26 August 1976 in Yambuku. The first recorded case was Mabalo Lokela, a 44‑year-old schoolteacher. The symptoms resembledmalaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or deat ...

, and subsequent patients received quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

. Transmission has been attributed to reuse of unsterilized needles and close personal contact, body fluids and places where the person has touched. During the 1976 Ebola outbreak in Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

, Ngoy Mushola travelled from Bumba to Yambuku, where he recorded the first clinical description of the disease in his daily log:

''The illness is characterized with a high temperature of about 39°C, hematemesis, diarrhea with blood, retrosternal abdominal pain, prostration with "heavy" articulations, and rapid evolution death after a mean of three days.'' Since the first recorded clinical description of the disease during 1976 in Zaire, the recent Ebola outbreak that started in March 2014, in addition, reached epidemic proportions and has killed more than 8000 people as of January 2015. This outbreak was centered in West Africa, an area that had not previously been affected by the disease. The toll was particularly grave in three countries: Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. A few cases were also reported in countries outside of West Africa, all related to international travelers who were exposed in the most affected regions and later showed symptoms of Ebola fever after reaching their destinations. The severity of the disease in humans varies widely, from rapid fatality to mild illness or even asymptomatic response. Studies of outbreaks in the late twentieth century failed to find a correlation between the disease severity and the genetic nature of the virus. Hence the variability in the severity of illness was suspected to correlate with genetic differences in the victims. This has been difficult to study in animal models that respond to the virus with hemorrhagic fever in a similar manner as humans, because typical mouse models do not so respond, and the required large numbers of appropriate test subjects are not easily available. In late October 2014, a publication reported a study of the response to a mouse-adapted strain of Zaire ebolavirus presented by a genetically diverse population of mice that was bred to have a range of responses to the virus that includes fatality from hemorrhagic fever.

Vaccine

In December 2016, a study found theVSV-EBOV

Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus–Zaire Ebola virus (rVSV-ZEBOV), also known as Ebola Zaire vaccine live and sold under the brand name Ervebo, is an Ebola vaccine for adults that prevents Ebola caused by the Zaire ebolavirus. When used ...

vaccine to be 70–100% effective against the Zaire ebola virus (not the Sudan ebolavirus

The species ''Sudan ebolavirus'' is a virological taxon included in the genus ''Ebolavirus'', family ''Filoviridae'', order ''Mononegavirales''. The species has a single virus member, Sudan virus (SUDV). The members of the species are called S ...

), making it the first vaccine against the disease. VSV-EBOV was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

in December 2019.

History and nomenclature

Ebola virus was first identified as a possible new "strain" of Marburg virus in 1976. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) identifies Ebola virus as

Ebola virus was first identified as a possible new "strain" of Marburg virus in 1976. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) identifies Ebola virus as species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

''Zaire ebolavirus'', which is part of the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial n ...

'' Ebolavirus'', family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

'' Filoviridae'', order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

'' Mononegavirales''. The name "Ebola virus" is derived from the Ebola River—a river that was at first thought to be in close proximity to the area in Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

, previously called Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

, where the 1976 Zaire Ebola virus outbreak occurred—and the taxonomic suffix ''virus''.

In 1998, the virus name was changed to "Zaire Ebola virus" and in 2002 to species ''Zaire ebolavirus''. However, most scientific articles continued to refer to "Ebola virus" or used the terms "Ebola virus" and "''Zaire ebolavirus''" in parallel. Consequently, in 2010, a group of researchers recommended that the name "Ebola virus" be adopted for a subclassification within the species ''Zaire ebolavirus'', with the corresponding abbreviation EBOV. Previous abbreviations for the virus were EBOV-Z (for "Ebola virus Zaire") and ZEBOV (for "Zaire Ebola virus" or "''Zaire ebolavirus''"). In 2011, the ICTV explicitly rejected a proposal (2010.010bV) to recognize this name, as ICTV does not designate names for subtypes, variants, strains, or other subspecies level groupings. At present, ICTV does not officially recognize "Ebola virus" as a taxonomic rank, but rather continues to use and recommend only the species designation ''Zaire ebolavirus''. The prototype Ebola virus, variant Mayinga (EBOV/May), was named for Mayinga N'Seka, a nurse who died during the 1976 Zaire outbreak.

The name ''Zaire ebolavirus'' is derived from ''Zaire

Zaire (, ), officially the Republic of Zaire (french: République du Zaïre, link=no, ), was a Congolese state from 1971 to 1997 in Central Africa that was previously and is now again known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Zaire was, ...

'' and the taxonomic suffix ''ebolavirus'' (which denotes an ebolavirus species and refers to the Ebola River). According to the rules for taxon naming established by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), the name ''Zaire ebolavirus'' is always to be capitalized

Capitalization (American English) or capitalisation (British English) is writing a word with its first letter as a capital letter (uppercase letter) and the remaining letters in lower case, in writing systems with a case distinction. The term a ...

, italicized, and to be preceded by the word "species". The names of its members (Zaire ebolaviruses) are to be capitalized, are not italicized, and used without articles

Article often refers to:

* Article (grammar), a grammatical element used to indicate definiteness or indefiniteness

* Article (publishing), a piece of nonfictional prose that is an independent part of a publication

Article may also refer to:

...

.

Virus inclusion criteria

A virus of the genus '' Ebolavirus'' is a member of the species ''Zaire ebolavirus'' if: * it is endemic in theDemocratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

, Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north ...

, or the Republic of the Congo

* it has a genome with two or three gene overlap

An overlapping gene (or OLG) is a gene whose expressible nucleotide sequence partially overlaps with the expressible nucleotide sequence of another gene. In this way, a nucleotide sequence may make a contribution to the function of one or more gen ...

s (''VP35''/''VP40'', ''GP''/''VP30'', ''VP24''/''L'')

* it has a genomic sequence that differs from the type virus EBOV/May by less than 30%

Evolution

''Zaire ebolavirus'' diverged from its ancestors between 1960 and 1976. The genetic diversity of ''Ebolavirus'' remained constant before 1900. Then, around the 1960s, most likely due to climate change or human activities, the genetic diversity of the virus dropped rapidly and most lineages became extinct. As the number of susceptible hosts declines, so does the effective population size and its genetic diversity. This genetic bottleneck effect has implications for the species' ability to cause Ebola virus disease in human hosts. A recombination event between ''Zaire ebolavirus'' lineages likely took place between 1996 and 2001 in wild apes giving rise to recombinant progeny viruses.Wittmann TJ, Biek R, Hassanin A, Rouquet P, Reed P, Yaba P, Pourrut X, Real LA, Gonzalez JP, Leroy EM. "Isolates of Zaire ebolavirus from wild apes reveal genetic lineage and recombinants". ''Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A''. 2007 Oct 23;104(43):17123–17127. Epub 2007 Oct 17. "Erratum" in: ''Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A''. 2007 Dec 4;104(49):19656. These recombinant viruses appear to have been responsible for a series of outbreaks among humans in Central Africa in 2001–2003. ''Zaire ebolavirus'' – Makona variant caused the 2014 West Africa outbreak. The outbreak was characterized by the longest instance of human-to-human transmission of the viral species. Pressures to adapt to the human host were seen at this time, however, no phenotypic changes in the virus (such as increased transmission, increased immune evasion by the virus) were seen.In literature

* Alex Kava's 2008 crime novel, ''Exposed'', focuses on the virus as a serial killer's weapon of choice. * William Close's 1995 ''Ebola: A Documentary Novel of Its First Explosion'' and 2002 ''Ebola: Through the Eyes of the People'' focused on individuals' reactions to the 1976 Ebola outbreak in Zaire. * '' The Hot Zone: A Terrifying True Story'': A 1994 best-selling book by Richard Preston about Ebola virus and related viruses, including an account of the outbreak of an Ebolavirus in primates housed in a quarantine facility in Reston, Virginia, USA *Tom Clancy

Thomas Leo Clancy Jr. (April 12, 1947 – October 1, 2013) was an American novelist. He is best known for his technically detailed espionage and military-science storylines set during and after the Cold War. Seventeen of his novels have ...

's 1996 novel, '' Executive Orders'', involves a Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

ern terrorist attack on the United States using an airborne form of a deadly Ebola virus named "Ebola Mayinga".

References

External links

Ebolavirus molecular biology

Ebolavirus proteins (PDB-101)

ICTV Files and DiscussionsDiscussion forum and file distribution for the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

Genomic data on ''Ebola'' virus isolates and other members of the family ''Filoviridae''

– Virological repository from the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics

Virus Pathogen Resource: Ebola Portal

– Genomic and other research data about Ebola and other human pathogenic viruses

The Ebola Virus

3D model of the Ebola virus, prepared by Visual Science, Moscow.

FILOVIRscientific resources for research on filoviruses

* * {{Use dmy dates, date=April 2017 Primate diseases Biological weapons Ebolaviruses Tropical diseases Zoonoses Ebola 1976 in biology Animal viral diseases Arthropod-borne viral fevers and viral haemorrhagic fevers Hemorrhagic fevers Virus-related cutaneous conditions