Eastern Han on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

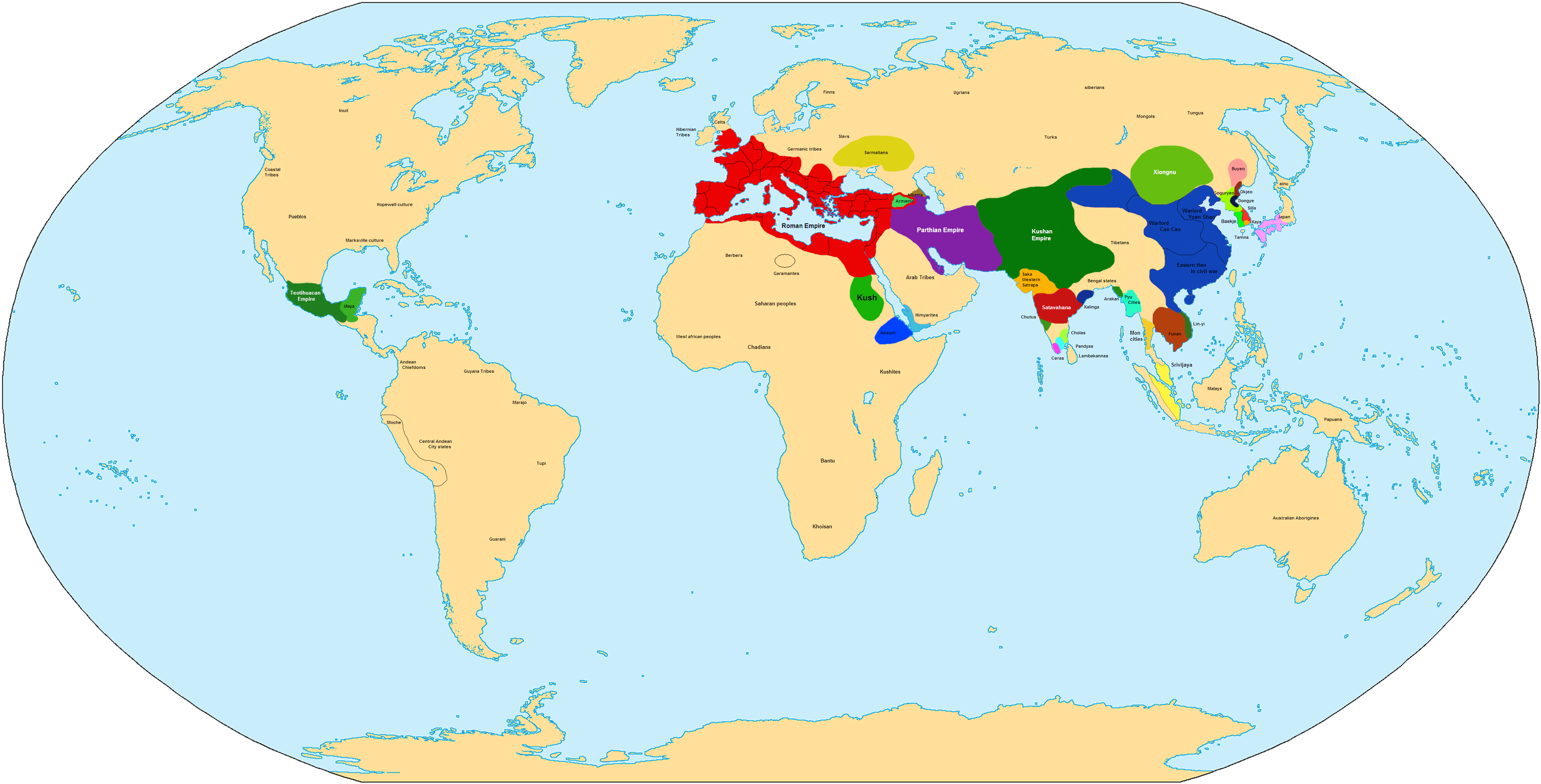

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived

At the beginning of the Western Han (), also known as the Former Han () dynasty, thirteen centrally-controlled

At the beginning of the Western Han (), also known as the Former Han () dynasty, thirteen centrally-controlled  Despite the tribute and negotiation between Laoshang Chanyu ( BC) and Emperor Wen ( BC) to reopen border markets, many of the

Despite the tribute and negotiation between Laoshang Chanyu ( BC) and Emperor Wen ( BC) to reopen border markets, many of the

Qin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

(221–207 BC) and a warring interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

known as the ChuHan contention (206–202 BC), and it was succeeded by the Three Kingdoms

The Three Kingdoms () from 220 to 280 AD was the tripartite division of China among the dynastic states of Cao Wei, Shu Han, and Eastern Wu. The Three Kingdoms period was preceded by the Han dynasty#Eastern Han, Eastern Han dynasty and wa ...

period (220–280 AD). The dynasty was briefly interrupted by the Xin dynasty

The Xin dynasty (; ), also known as Xin Mang () in Chinese historiography, was a short-lived Chinese imperial dynasty which lasted from 9 to 23 AD, established by the Han dynasty consort kin Wang Mang, who usurped the throne of the Emperor Ping ...

(9–23 AD) established by usurping regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state ''pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy, ...

Wang Mang

Wang Mang () (c. 45 – 6 October 23 CE), courtesy name Jujun (), was the founder and the only emperor of the short-lived Chinese Xin dynasty. He was originally an official and consort kin of the Han dynasty and later seized the thro ...

, and is thus separated into two periods—the Western Han

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

(202 BC – 9 AD) and the Eastern Han (25–220 AD). Spanning over four centuries, the Han dynasty is considered a golden age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the '' Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages, Gold being the first and the one during which the Go ...

in Chinese history, and it has influenced the identity of the Chinese civilization ever since. Modern China's majority ethnic group refers to themselves as the "Han people

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive v ...

", the Sinitic language is known as "Han language", and the written Chinese

Written Chinese () comprises Chinese characters used to represent the Chinese language. Chinese characters do not constitute an alphabet or a compact syllabary. Rather, the writing system is roughly logosyllabic; that is, a character generally re ...

is referred to as "Han characters

Chinese characters () are logograms developed for the writing of Chinese. In addition, they have been adapted to write other East Asian languages, and remain a key component of the Japanese writing system where they are known as ''kanji' ...

".

The emperor

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in E ...

was at the pinnacle of Han society. He presided over the Han government but shared power with both the nobility and appointed ministers who came largely from the scholarly gentry class. The Han Empire was divided into areas directly controlled by the central government called commanderies

In the Middle Ages, a commandery (rarely commandry) was the smallest administrative division of the European landed properties of a military order. It was also the name of the house where the knights of the commandery lived.Anthony Luttrell and Gr ...

, as well as a number of semi-autonomous kingdoms. These kingdoms gradually lost all vestiges of their independence, particularly following the Rebellion of the Seven States. From the reign of Emperor Wu ( BC) onward, the Chinese court officially sponsored Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

in education and court politics, synthesized with the cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosophe ...

of later scholars such as Dong Zhongshu. This policy endured until the fall of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

in 1912 AD.

The Han dynasty saw an age of economic prosperity and witnessed a significant growth of the money economy first established during the Zhou dynasty

The Zhou dynasty ( ; Old Chinese ( B&S): *''tiw'') was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of China by ...

( BC). The coinage issued by the central government mint in 119 BC remained the standard coinage of China until the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdo ...

(618–907 AD). The period saw a number of limited institutional innovations. To finance its military campaigns and the settlement of newly conquered frontier territories, the Han government nationalized

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to priv ...

the private salt and iron industries in 117 BC, though these government monopolies were later repealed during the Eastern Han dynasty. Science and technology during the Han period saw significant advances, including the process of papermaking

Papermaking is the manufacture of paper and cardboard, which are used widely for printing, writing, and packaging, among many other purposes. Today almost all paper is made using industrial machinery, while handmade paper survives as a speciali ...

, the nautical steering ship rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw a ...

, the use of negative number

In mathematics, a negative number represents an opposite. In the real number system, a negative number is a number that is inequality (mathematics), less than 0 (number), zero. Negative numbers are often used to represent the magnitude of a loss ...

s in mathematics, the raised-relief map, the hydraulic

Hydraulics (from Greek: Υδραυλική) is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counter ...

-powered armillary sphere

An armillary sphere (variations are known as spherical astrolabe, armilla, or armil) is a model of objects in the sky (on the celestial sphere), consisting of a spherical framework of rings, centered on Earth or the Sun, that represent lines ...

for astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, and a seismometer

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground noises and shaking such as caused by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The outp ...

employing an inverted pendulum

An inverted pendulum is a pendulum that has its center of mass above its pivot point. It is unstable and without additional help will fall over. It can be suspended stably in this inverted position by using a control system to monitor the a ...

that could be used to discern the cardinal direction of distant earthquakes.

The Han dynasty is known for the many conflicts it had with the Xiongnu, a nomadic steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslan ...

confederation to the dynasty's north. The Xiongnu initially had the upper hand in these conflicts. They defeated the Han in 200 BC and forced the Han to submit as a ''de facto'' inferior and vassal partner for several decades, while continuing their military raids on the dynasty's borders. This changed in 133 BC, during the reign of Emperor Wu, when Han forces began a series of intensive military campaigns and operations against the Xiongnu. The Han ultimately defeated the Xiongnu in these campaigns, and the Xiongnu were forced to accept vassal status as Han tributaries. Additionally, the campaigns brought the Hexi Corridor

The Hexi Corridor (, Xiao'erjing: حْسِ ظِوْلاْ, IPA: ), also known as the Gansu Corridor, is an important historical region located in the modern western Gansu province of China. It refers to a narrow stretch of traversable and relat ...

and the Tarim Basin

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about and one of the largest basins in Northwest China.Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hyd ...

of Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the former ...

under Han control, split the Xiongnu into two separate confederations, and helped establish the vast trade network known as the Silk Road, which reached as far as the Mediterranean world. The territories north of Han's borders were later overrun by the nomadic Xianbei

The Xianbei (; ) were a Proto-Mongolic ancient nomadic people that once resided in the eastern Eurasian steppes in what is today Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Northeastern China. They originated from the Donghu people who splintered into t ...

confederation. Emperor Wu also launched successful military expeditions in the south, annexing Nanyue in 111 BC and Dian in 109 BC. He expanded Han territory into the northern Korean Peninsula

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

as well, where Han forces conquered Gojoseon and established the Xuantu and Lelang Commanderies in 108 BC.

After 92 AD, the palace eunuchs

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castration, castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2n ...

increasingly involved themselves in the dynasty's court politics, engaging in violent power struggles between the various consort clans of the empresses and empresses dowager, causing the Han's ultimate downfall. Imperial authority was also seriously challenged by large Daoist

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the '' Ta ...

religious societies which instigated the Yellow Turban Rebellion

The Yellow Turban Rebellion, alternatively translated as the Yellow Scarves Rebellion, was a peasant revolt in China against the Eastern Han dynasty. The uprising broke out in 184 CE during the reign of Emperor Ling. Although the main rebelli ...

and the Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion

The Way of the Five Pecks of Rice () or the Way of the Celestial Master, commonly abbreviated to simply The Celestial Masters, was a Chinese Taoist movement founded by the first Celestial Master Zhang Daoling in 142 CE. At its height, the mov ...

. Following the death of Emperor Ling ( AD), the palace eunuchs suffered wholesale massacre by military officers

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent conte ...

, allowing members of the aristocracy and military governors to become warlords and divide the empire. When Cao Pi

Cao Pi () ( – 29 June 226), courtesy name Zihuan, was the first emperor of the state of Cao Wei in the Three Kingdoms period of China. He was the second son of Cao Cao, a warlord who lived in the late Eastern Han dynasty, but the eldest son ...

, king of Wei

Wei or WEI may refer to:

States

* Wey (state) (衛, 1040–209 BC), Wei in pinyin, but spelled Wey to distinguish from the bigger Wei of the Warring States

* Wei (state) (魏, 403–225 BC), one of the seven major states of the Warring States per ...

, usurped the throne from Emperor Xian, the Han dynasty ceased to exist.

Etymology

According to the ''Records of the Grand Historian

''Records of the Grand Historian'', also known by its Chinese name ''Shiji'', is a monumental history of China that is the first of China's 24 dynastic histories. The ''Records'' was written in the early 1st century by the ancient Chinese his ...

'', after the collapse of the Qin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

the hegemon Xiang Yu

Xiang Yu (, –202 BC), born Xiang Ji (), was the Hegemon-King (Chinese: 霸王, ''Bà Wáng'') of Western Chu during the Chu–Han Contention period (206–202 BC) of China. A noble of the Chu state, Xiang Yu rebelled against the Qin dyna ...

appointed Liu Bang as prince of the small fief of Hanzhong

Hanzhong (; abbreviation: Han) is a prefecture-level city in the southwest of Shaanxi province, China, bordering the provinces of Sichuan to the south and Gansu to the west.

The founder of the Han dynasty, Liu Bang, was once enfeoffed as t ...

, named after its location on the Han River (in modern southwest Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), Ning ...

). Following Liu Bang's victory in the Chu–Han Contention

The Chu–Han Contention ( zh, , lk=on) or Chu–Han War () was an interregnum period in ancient China between the fallen Qin dynasty and the subsequent Han dynasty. After the third and last Qin ruler, Ziying, unconditionally surrendered ...

, the resulting Han dynasty was named after the Hanzhong fief.

History

Western Han

China's first imperial dynasty was theQin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

(221–207 BC). The Qin united the Chinese Warring States

The Warring States period () was an era in ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the Qin wars of conquest ...

by conquest, but their regime became unstable after the death of the first emperor Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang (, ; 259–210 BC) was the founder of the Qin dynasty and the first emperor of a unified China. Rather than maintain the title of "king" ( ''wáng'') borne by the previous Shang and Zhou rulers, he ruled as the First Emperor ( ...

. Within four years, the dynasty's authority had collapsed in the face of rebellion. Two former rebel leaders, Xiang Yu

Xiang Yu (, –202 BC), born Xiang Ji (), was the Hegemon-King (Chinese: 霸王, ''Bà Wáng'') of Western Chu during the Chu–Han Contention period (206–202 BC) of China. A noble of the Chu state, Xiang Yu rebelled against the Qin dyna ...

(d. 202 BC) of Chu

Chu or CHU may refer to:

Chinese history

* Chu (state) (c. 1030 BC–223 BC), a state during the Zhou dynasty

* Western Chu (206 BC–202 BC), a state founded and ruled by Xiang Yu

* Chu Kingdom (Han dynasty) (201 BC–70 AD), a kingdom of the Ha ...

and Liu Bang (d. 195 BC) of Han, engaged in a war to decide who would become hegemon of China, which had fissured into 18 kingdoms

The historiographical term "Eighteen Kingdoms" ( zh, t=十八國), also translated to as "Eighteen States", refers to the eighteen ''fengjian'' states in China created by military leader Xiang Yu in 206 BCE, after the collapse of the Qin dynasty.� ...

, each claiming allegiance to either Xiang Yu or Liu Bang. Although Xiang Yu proved to be an effective commander, Liu Bang defeated him at the Battle of Gaixia (202 BC), in modern-day Anhui

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze River ...

. Liu Bang assumed the title "emperor" (''huangdi'') at the urging of his followers and is known posthumously as Emperor Gaozu ( BC). Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin ...

(known today as Xi'an) was chosen as the new capital of the reunified empire under Han.

At the beginning of the Western Han (), also known as the Former Han () dynasty, thirteen centrally-controlled

At the beginning of the Western Han (), also known as the Former Han () dynasty, thirteen centrally-controlled commanderies

In the Middle Ages, a commandery (rarely commandry) was the smallest administrative division of the European landed properties of a military order. It was also the name of the house where the knights of the commandery lived.Anthony Luttrell and Gr ...

—including the capital region—existed in the western third of the empire, while the eastern two-thirds were divided into ten semi-autonomous kingdoms. To placate his prominent commanders from the war with Chu, Emperor Gaozu enfeoffed

In the Middle Ages, especially under the European feudal system, feoffment or enfeoffment was the deed by which a person was given land in exchange for a pledge of service. This mechanism was later used to avoid restrictions on the passage of ...

some of them as kings.

By 196 BC, the Han court had replaced all but one of these kings (the exception being in Changsha

Changsha (; ; ; Changshanese pronunciation: (), Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is the capital and the largest city of Hunan Province of China. Changsha is the 17th most populous city in China with a population of over 10 million, and th ...

) with royal Liu family members, since the loyalty of non-relatives to the throne was questioned. After several insurrections by Han kings—the largest being the Rebellion of the Seven States in 154 BC—the imperial court enacted a series of reforms beginning in 145 BC limiting the size and power of these kingdoms and dividing their former territories into new centrally-controlled commanderies. Kings were no longer able to appoint their own staff; this duty was assumed by the imperial court. Kings became nominal heads of their fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of f ...

s and collected a portion of tax revenues as their personal incomes. The kingdoms were never entirely abolished and existed throughout the remainder of Western and Eastern Han.

To the north of China proper

China proper, Inner China, or the Eighteen Provinces is a term used by some Western writers in reference to the "core" regions of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China. This term is used to express a distinction between the "core" regions pop ...

, the nomadic Xiongnu chieftain Modu Chanyu ( BC) conquered various tribes inhabiting the eastern portion of the Eurasian Steppe

The Eurasian Steppe, also simply called the Great Steppe or the steppes, is the vast steppe ecoregion of Eurasia in the temperate grasslands, savannas and shrublands biome. It stretches through Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Tra ...

. By the end of his reign, he controlled Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym "Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East ( Outer ...

, Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 millio ...

, and the Tarim Basin

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about and one of the largest basins in Northwest China.Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hyd ...

, subjugating over twenty states east of Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top: Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zi ...

. Emperor Gaozu was troubled about the abundant Han-manufactured iron weapons traded to the Xiongnu along the northern borders, and he established a trade embargo

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they ...

against the group.

In retaliation, the Xiongnu invaded what is now Shanxi

Shanxi (; ; formerly romanised as Shansi) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the North China region. The capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-lev ...

province, where they defeated the Han forces at Baideng in 200 BC. After negotiations, the '' heqin'' agreement in 198 BC nominally held the leaders of the Xiongnu and the Han as equal partners in a royal marriage alliance, but the Han were forced to send large amounts of tribute items such as silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the ...

clothes, food, and wine to the Xiongnu.

Despite the tribute and negotiation between Laoshang Chanyu ( BC) and Emperor Wen ( BC) to reopen border markets, many of the

Despite the tribute and negotiation between Laoshang Chanyu ( BC) and Emperor Wen ( BC) to reopen border markets, many of the Chanyu

Chanyu () or Shanyu (), short for Chengli Gutu Chanyu (), was the title used by the supreme rulers of Inner Asian nomads for eight centuries until superseded by the title "''Khagan''" in 402 CE. The title was most famously used by the ruling ...

's Xiongnu subordinates chose not to obey the treaty and periodically raided Han territories south of the Great Wall

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand ''li'' wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic grou ...

for additional goods. In a court conference assembled by Emperor Wu ( BC) in 135 BC, the majority consensus of the ministers was to retain the ''heqin'' agreement. Emperor Wu accepted this, despite continuing Xiongnu raids.

However, a court conference the following year convinced the majority that a limited engagement at Mayi involving the assassination of the Chanyu would throw the Xiongnu realm into chaos and benefit the Han. When this plot failed in 133 BC, Emperor Wu launched a series of massive military invasions into Xiongnu territory. The assault culminated in 119 BC at the Battle of Mobei, when Han commanders Huo Qubing (d. 117 BC) and Wei Qing (d. 106 BC) forced the Xiongnu court to flee north of the Gobi Desert

The Gobi Desert ( Chinese: 戈壁 (沙漠), Mongolian: Говь (ᠭᠣᠪᠢ)) () is a large desert or brushland region in East Asia, and is the sixth largest desert in the world.

Geography

The Gobi measures from southwest to northeast ...

, and Han forces reached as far north as Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal (, russian: Oзеро Байкал, Ozero Baykal ); mn, Байгал нуур, Baigal nuur) is a rift lake in Russia. It is situated in southern Siberia, between the Federal subjects of Russia, federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast, I ...

.

After Wu's reign, Han forces continued to fight the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu leader Huhanye Chanyu ( BC) finally submitted to the Han as a tributary vassal in 51 BC. Huhanye's rival claimant to the throne, Zhizhi Chanyu

Zhizhi or Chi-Chi (, from Old Chinese (58 BCE): *''tśit-kie'' < *''tit-ke'';Schuessler 2014, p. 277 died 36 BCE), also known as Jzh-jzh, was a  In 121 BC, Han forces expelled the Xiongnu from a vast territory spanning the

In 121 BC, Han forces expelled the Xiongnu from a vast territory spanning the

Chen Tang

Chen Tang (), born in Jining, Shandong, was a Han dynasty Chinese general famous for his battle against Zhizhi in 36 BC during the Han–Xiongnu War.

Battle of Zhizhi

At approximately 36 BC, the governor of the Western Regions was Gan Ya ...

and Gan Yanshou () at the Battle of Zhizhi, in modern Taraz

Taraz ( kz, Тараз, تاراز, translit=Taraz ; known to Europeans as Talas) is a city and the administrative center of Jambyl Region in Kazakhstan, located on the Talas (Taraz) River in the south of the country near the border with Kyrgyz ...

, Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental coun ...

.

In 121 BC, Han forces expelled the Xiongnu from a vast territory spanning the

In 121 BC, Han forces expelled the Xiongnu from a vast territory spanning the Hexi Corridor

The Hexi Corridor (, Xiao'erjing: حْسِ ظِوْلاْ, IPA: ), also known as the Gansu Corridor, is an important historical region located in the modern western Gansu province of China. It refers to a narrow stretch of traversable and relat ...

to Lop Nur

Lop Nur or Lop Nor (from a Mongolian name meaning "Lop Lake", where "Lop" is a toponym of unknown origin) is a former salt lake, now largely dried up, located in the eastern fringe of the Tarim Basin, between the Taklamakan and Kumtag desert ...

. They repelled a joint Xiongnu- Qiang invasion of this northwestern territory in 111 BC. In that same year, the Han court established four new frontier commanderies in this region to consolidate their control: Jiuquan

Jiuquan, formerly known as Suzhou, is a prefecture-level city in the northwesternmost part of Gansu Province in the People's Republic of China. It is more than wide from east to west, occupying , although its built-up area is mostly located in ...

, Zhangyi, Dunhuang

Dunhuang () is a county-level city in Northwestern Gansu Province, Western China. According to the 2010 Chinese census, the city has a population of 186,027, though 2019 estimates put the city's population at about 191,800. Dunhuang was a major ...

, and Wuwei. The majority of people on the frontier were soldiers. On occasion, the court forcibly moved peasant farmers to new frontier settlements, along with government-owned slaves and convicts who performed hard labor. The court also encouraged commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

s, such as farmers, merchants, landowners, and hired laborers, to voluntarily migrate to the frontier.

Even before the Han's expansion into Central Asia, diplomat Zhang Qian

Zhang Qian (; died c. 114) was a Chinese official and diplomat who served as an imperial envoy to the world outside of China in the late 2nd century BC during the Han dynasty. He was one of the first official diplomats to bring back valuable inf ...

's travels from 139 to 125 BC had established Chinese contacts with many surrounding civilizations. Zhang encountered Dayuan

Dayuan (or Tayuan; ; Middle Chinese ''dâiC-jwɐn'' < : ''dɑh-ʔyɑn'') is the Chinese

Wang Zhengjun (71 BC – 13 AD) was first empress, then empress dowager, and finally grand empress dowager during the reigns of the Emperors Yuan ( BC), Cheng ( BC), and Ai ( BC), respectively. During this time, a succession of her male relatives held the title of regent. Following the death of Ai, Wang Zhengjun's nephew

Wang Zhengjun (71 BC – 13 AD) was first empress, then empress dowager, and finally grand empress dowager during the reigns of the Emperors Yuan ( BC), Cheng ( BC), and Ai ( BC), respectively. During this time, a succession of her male relatives held the title of regent. Following the death of Ai, Wang Zhengjun's nephew

The Eastern Han (), also known as the Later Han (), formally began on 5 August AD 25, when Liu Xiu became

The Eastern Han (), also known as the Later Han (), formally began on 5 August AD 25, when Liu Xiu became  Foreign travelers to Eastern-Han China included

Foreign travelers to Eastern-Han China included  Following Huan's death, Dou Wu and the Grand Tutor

Following Huan's death, Dou Wu and the Grand Tutor

The Han-era family was Patrilineality, patrilineal and typically had four to five nuclear family members living in one household. Multiple generations of extended family members did not occupy the same house, unlike families of later dynasties. According to Confucianism, Confucian family norms, various family members were treated with different levels of respect and intimacy. For example, there were different accepted time frames for mourning the death of a father versus a paternal uncle.

Marriages were highly ritualized, particularly for the wealthy, and included many important steps. The giving of betrothal gifts, known as Bride price, bridewealth and dowry, were especially important. A lack of either was considered dishonorable and the woman would have been seen not as a wife, but as a Concubinage, concubine. Arranged marriages were normal, with the father's input on his offspring's spouse being considered more important than the mother's.

Monogamy, Monogamous marriages were also normal, although nobles and high officials were wealthy enough to afford and support concubines as additional lovers. Under certain conditions dictated by custom, not law, both men and women were able to divorce their spouses and remarry. However, a woman who had been widowed continued to belong to her husband's family after his death. In order to remarry, the widow would have to be returned to her family in exchange for a ransom fee. Her children would not be allowed to go with her.

Apart from the passing of noble titles or ranks, inheritance practices did not involve primogeniture; each son received an equal share of the family property. Unlike the practice in later dynasties, the father usually sent his adult married sons away with their portions of the family fortune. Daughters received a portion of the family fortune through their dowry, marriage dowries, though this was usually much less than the shares of sons. A different distribution of the remainder could be specified in a last will and testament, will, but it is unclear how common this was.

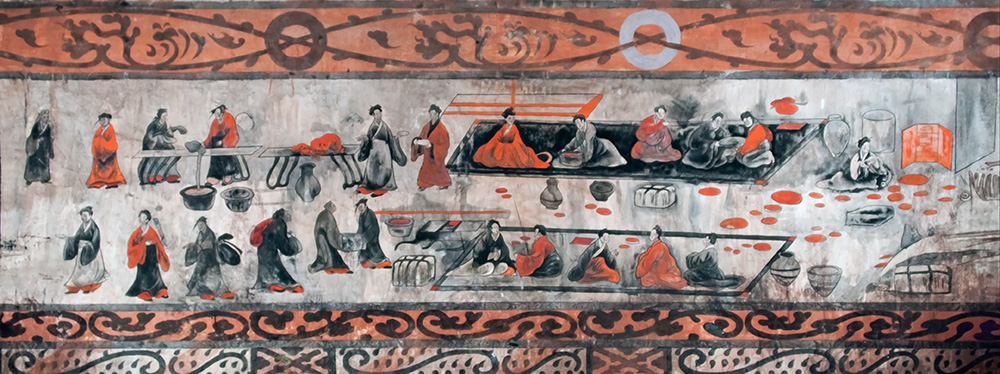

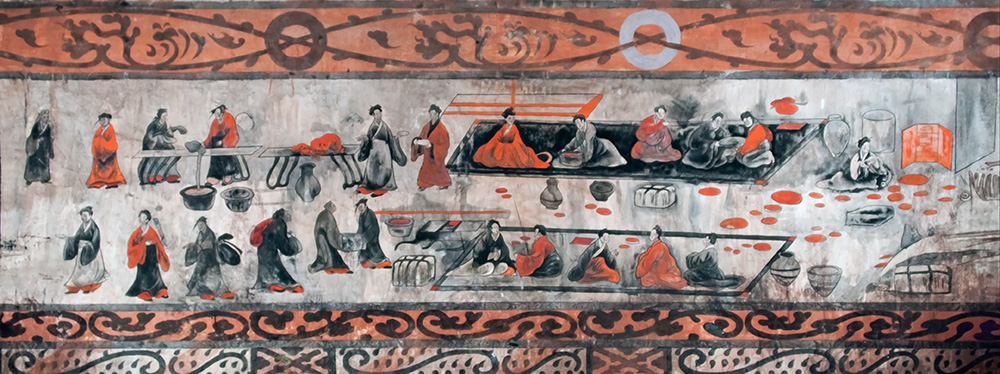

Women were expected to obey the will of their father, then their husband, and then their adult son in old age. However, it is known from contemporary sources that there were many deviations to this rule, especially in regard to mothers over their sons, and empresses who ordered around and openly humiliated their fathers and brothers. Women were exempt from the annual corvée labor duties, but often engaged in a range of income-earning occupations aside from their domestic chores of cooking and cleaning.

The most common occupation for women was weaving clothes for the family, for sale at market, or for large textile enterprises that employed hundreds of women. Other women helped on their brothers' farms or became singers, dancers, Witchcraft, sorceresses, respected medical physicians, and successful merchants who could afford their own silk clothes. Some women formed spinning collectives, aggregating the resources of several different families.

The Han-era family was Patrilineality, patrilineal and typically had four to five nuclear family members living in one household. Multiple generations of extended family members did not occupy the same house, unlike families of later dynasties. According to Confucianism, Confucian family norms, various family members were treated with different levels of respect and intimacy. For example, there were different accepted time frames for mourning the death of a father versus a paternal uncle.

Marriages were highly ritualized, particularly for the wealthy, and included many important steps. The giving of betrothal gifts, known as Bride price, bridewealth and dowry, were especially important. A lack of either was considered dishonorable and the woman would have been seen not as a wife, but as a Concubinage, concubine. Arranged marriages were normal, with the father's input on his offspring's spouse being considered more important than the mother's.

Monogamy, Monogamous marriages were also normal, although nobles and high officials were wealthy enough to afford and support concubines as additional lovers. Under certain conditions dictated by custom, not law, both men and women were able to divorce their spouses and remarry. However, a woman who had been widowed continued to belong to her husband's family after his death. In order to remarry, the widow would have to be returned to her family in exchange for a ransom fee. Her children would not be allowed to go with her.

Apart from the passing of noble titles or ranks, inheritance practices did not involve primogeniture; each son received an equal share of the family property. Unlike the practice in later dynasties, the father usually sent his adult married sons away with their portions of the family fortune. Daughters received a portion of the family fortune through their dowry, marriage dowries, though this was usually much less than the shares of sons. A different distribution of the remainder could be specified in a last will and testament, will, but it is unclear how common this was.

Women were expected to obey the will of their father, then their husband, and then their adult son in old age. However, it is known from contemporary sources that there were many deviations to this rule, especially in regard to mothers over their sons, and empresses who ordered around and openly humiliated their fathers and brothers. Women were exempt from the annual corvée labor duties, but often engaged in a range of income-earning occupations aside from their domestic chores of cooking and cleaning.

The most common occupation for women was weaving clothes for the family, for sale at market, or for large textile enterprises that employed hundreds of women. Other women helped on their brothers' farms or became singers, dancers, Witchcraft, sorceresses, respected medical physicians, and successful merchants who could afford their own silk clothes. Some women formed spinning collectives, aggregating the resources of several different families.

Some important texts were created and studied by scholars. Philosophical works written by Yang Xiong (author), Yang Xiong (53 BCE – 18 CE), Huan Tan (43 BCE – 28 CE), Wang Chong (27–100 CE), and Wang Fu (philosopher), Wang Fu (78–163 CE) questioned whether human nature was innately good or evil and posed challenges to Dong's universal order. The ''Shiji, Records of the Grand Historian'' by Sima Tan (d. 110 BCE) and his son Sima Qian (145–86 BCE) Chinese historiography, established the standard model for all of imperial China's Twenty-Four Histories, Standard Histories, such as the ''Book of Han'' written by Ban Biao (3–54 CE), his son Ban Gu (32–92 CE), and his daughter Ban Zhao (45–116 CE). There were Chinese dictionaries, dictionaries such as the ''Shuowen Jiezi'' by Xu Shen ( – CE) and the ''Fangyan (book), Fangyan'' by Yang Xiong.

Biography, Biographies on important figures were written by various gentrymen. Han dynasty poetry was dominated by the Fu (poetry), ''fu'' genre, which achieved its greatest prominence during the reign of Emperor Wu.

Some important texts were created and studied by scholars. Philosophical works written by Yang Xiong (author), Yang Xiong (53 BCE – 18 CE), Huan Tan (43 BCE – 28 CE), Wang Chong (27–100 CE), and Wang Fu (philosopher), Wang Fu (78–163 CE) questioned whether human nature was innately good or evil and posed challenges to Dong's universal order. The ''Shiji, Records of the Grand Historian'' by Sima Tan (d. 110 BCE) and his son Sima Qian (145–86 BCE) Chinese historiography, established the standard model for all of imperial China's Twenty-Four Histories, Standard Histories, such as the ''Book of Han'' written by Ban Biao (3–54 CE), his son Ban Gu (32–92 CE), and his daughter Ban Zhao (45–116 CE). There were Chinese dictionaries, dictionaries such as the ''Shuowen Jiezi'' by Xu Shen ( – CE) and the ''Fangyan (book), Fangyan'' by Yang Xiong.

Biography, Biographies on important figures were written by various gentrymen. Han dynasty poetry was dominated by the Fu (poetry), ''fu'' genre, which achieved its greatest prominence during the reign of Emperor Wu.

Han scholars such as Jia Yi (201–169 BCE) portrayed the previous

Han scholars such as Jia Yi (201–169 BCE) portrayed the previous

Families throughout Han China made ritual sacrifices of animals and food to deities, spirits, and Ancestor worship, ancestors at Temple (Chinese), temples and shrines. They believed that these items could be used by those in the spiritual realm. It was thought that each person had a Hun and po, two-part soul: the spirit-soul (''hun'' 魂) which journeyed to the afterlife paradise of immortals (''Xian (Taoism), xian''), and the body-soul (''po'' 魄) which remained in its grave or tomb on earth and was only reunited with the spirit-soul through a ritual ceremony.

Families throughout Han China made ritual sacrifices of animals and food to deities, spirits, and Ancestor worship, ancestors at Temple (Chinese), temples and shrines. They believed that these items could be used by those in the spiritual realm. It was thought that each person had a Hun and po, two-part soul: the spirit-soul (''hun'' 魂) which journeyed to the afterlife paradise of immortals (''Xian (Taoism), xian''), and the body-soul (''po'' 魄) which remained in its grave or tomb on earth and was only reunited with the spirit-soul through a ritual ceremony.

In addition to his many other roles, the emperor acted as the highest priest in the land who made sacrifices to Tian, Heaven, the main deities known as the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors, Five Powers, and the Shen (Chinese religion), spirits (''shen'' 神) of mountains and rivers. It was believed that the three realms of Heaven, Earth, and Mankind were linked by natural cycles of yin and yang and the Wuxing (Chinese philosophy), five phases. If the emperor did not behave according to proper ritual, ethics, and morals, he could disrupt the fine balance of these cosmological cycles and cause calamities such as earthquakes, floods, droughts, epidemics, and swarms of locusts.

It was believed that immortality could be achieved if one reached the lands of the Queen Mother of the West or Mount Penglai. Han-era Daoism, Daoists assembled into small groups of hermits who attempted to achieve immortality through breathing exercises, sexual techniques, and the use of Elixir of life, medical elixirs.

By the 2nd century CE, Daoists formed large hierarchical religious societies such as the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice. Its followers believed that the sage-philosopher Laozi () was a holy prophet who would offer salvation and good health if his devout followers would Confession (religion), confess their sins, ban the worship of unclean gods who accepted meat sacrifices, and chant sections of the ''Tao Te Ching, Daodejing''.

Buddhism Chinese Buddhism#History, first entered Imperial China through the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism, Silk Road during the Eastern Han, and was first mentioned in 65 CE. Liu Ying (prince), Liu Ying (d. 71 CE), a half-brother to Emperor Ming of Han ( CE), was one of its earliest Chinese adherents, although Chinese Buddhism at this point was heavily associated with Society and culture of the Han dynasty#Competing ideologies, Huang-Lao Daoism. China's first known Buddhist temple, the White Horse Temple, was constructed outside the wall of the capital,

In addition to his many other roles, the emperor acted as the highest priest in the land who made sacrifices to Tian, Heaven, the main deities known as the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors, Five Powers, and the Shen (Chinese religion), spirits (''shen'' 神) of mountains and rivers. It was believed that the three realms of Heaven, Earth, and Mankind were linked by natural cycles of yin and yang and the Wuxing (Chinese philosophy), five phases. If the emperor did not behave according to proper ritual, ethics, and morals, he could disrupt the fine balance of these cosmological cycles and cause calamities such as earthquakes, floods, droughts, epidemics, and swarms of locusts.

It was believed that immortality could be achieved if one reached the lands of the Queen Mother of the West or Mount Penglai. Han-era Daoism, Daoists assembled into small groups of hermits who attempted to achieve immortality through breathing exercises, sexual techniques, and the use of Elixir of life, medical elixirs.

By the 2nd century CE, Daoists formed large hierarchical religious societies such as the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice. Its followers believed that the sage-philosopher Laozi () was a holy prophet who would offer salvation and good health if his devout followers would Confession (religion), confess their sins, ban the worship of unclean gods who accepted meat sacrifices, and chant sections of the ''Tao Te Ching, Daodejing''.

Buddhism Chinese Buddhism#History, first entered Imperial China through the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism, Silk Road during the Eastern Han, and was first mentioned in 65 CE. Liu Ying (prince), Liu Ying (d. 71 CE), a half-brother to Emperor Ming of Han ( CE), was one of its earliest Chinese adherents, although Chinese Buddhism at this point was heavily associated with Society and culture of the Han dynasty#Competing ideologies, Huang-Lao Daoism. China's first known Buddhist temple, the White Horse Temple, was constructed outside the wall of the capital,

In Han government, the emperor was the supreme judge and lawgiver, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and sole designator of official nominees appointed to the top posts in central and local administrations; those who earned a Government of the Han dynasty#Salaries, 600-bushel salary-rank or higher. Theoretically, there were no limits to his power.

However, state organs with competing interests and institutions such as the court conference (''tíngyì'' )—where ministers were convened to reach majority consensus on an issue—pressured the emperor to accept the advice of his ministers on policy decisions. If the emperor rejected a court conference decision, he risked alienating his high ministers. Nevertheless, emperors sometimes did reject the majority opinion reached at court conferences.

Below the emperor were his cabinet (government), cabinet members known as the Three Councillors of State, Three Councilors of State (''Sān gōng'' ). These were the Chancellor of China, Chancellor or Minister over the Masses (''Chéngxiāng'' or ''Dà sìtú'' ), the Imperial Counselor or Excellency of Works (''Yùshǐ dàfū'' or ''Dà sìkōng'' ), and Grand Commandant or Grand Marshal (''Tàiwèi'' or ''Dà sīmǎ'' ).

The Chancellor, whose title was changed to 'Minister over the Masses' in 8 BC, was chiefly responsible for drafting the government budget. The Chancellor's other duties included managing provincial registers for land and population, leading court conferences, acting as judge in lawsuits, and recommending nominees for high office. He could appoint officials below the salary-rank of 600 bushels.

The Imperial Counselor's chief duty was to conduct disciplinary procedures for officials. He shared similar duties with the Chancellor, such as receiving annual provincial reports. However, when his title was changed to Minister of Works in 8 BC, his chief duty became the oversight of public works projects.

The Grand Commandant, whose title was changed to Grand Marshal in 119 BC before reverting to Grand Commandant in 51 AD, was the irregularly posted commander of the military and then

In Han government, the emperor was the supreme judge and lawgiver, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and sole designator of official nominees appointed to the top posts in central and local administrations; those who earned a Government of the Han dynasty#Salaries, 600-bushel salary-rank or higher. Theoretically, there were no limits to his power.

However, state organs with competing interests and institutions such as the court conference (''tíngyì'' )—where ministers were convened to reach majority consensus on an issue—pressured the emperor to accept the advice of his ministers on policy decisions. If the emperor rejected a court conference decision, he risked alienating his high ministers. Nevertheless, emperors sometimes did reject the majority opinion reached at court conferences.

Below the emperor were his cabinet (government), cabinet members known as the Three Councillors of State, Three Councilors of State (''Sān gōng'' ). These were the Chancellor of China, Chancellor or Minister over the Masses (''Chéngxiāng'' or ''Dà sìtú'' ), the Imperial Counselor or Excellency of Works (''Yùshǐ dàfū'' or ''Dà sìkōng'' ), and Grand Commandant or Grand Marshal (''Tàiwèi'' or ''Dà sīmǎ'' ).

The Chancellor, whose title was changed to 'Minister over the Masses' in 8 BC, was chiefly responsible for drafting the government budget. The Chancellor's other duties included managing provincial registers for land and population, leading court conferences, acting as judge in lawsuits, and recommending nominees for high office. He could appoint officials below the salary-rank of 600 bushels.

The Imperial Counselor's chief duty was to conduct disciplinary procedures for officials. He shared similar duties with the Chancellor, such as receiving annual provincial reports. However, when his title was changed to Minister of Works in 8 BC, his chief duty became the oversight of public works projects.

The Grand Commandant, whose title was changed to Grand Marshal in 119 BC before reverting to Grand Commandant in 51 AD, was the irregularly posted commander of the military and then  Ranked below the Three Councilors of State were the Nine Ministers (''Jiǔ qīng'' ), who each headed a specialized ministry. The Minister of Ceremonies (''Tàicháng'' ) was the chief official in charge of religious rites, rituals, prayers, and the maintenance of ancestral temples and altars. The Minister of the Household (''Guāng lù xūn'' ) was in charge of the emperor's security within the palace grounds, external imperial parks, and wherever the emperor made an outing by chariot.

Ranked below the Three Councilors of State were the Nine Ministers (''Jiǔ qīng'' ), who each headed a specialized ministry. The Minister of Ceremonies (''Tàicháng'' ) was the chief official in charge of religious rites, rituals, prayers, and the maintenance of ancestral temples and altars. The Minister of the Household (''Guāng lù xūn'' ) was in charge of the emperor's security within the palace grounds, external imperial parks, and wherever the emperor made an outing by chariot.

The Minister of the Guards (''Wèiwèi'' ) was responsible for securing and patrolling the walls, towers, and gates of the imperial palaces. The Minister Coachman (''Tàipú'' ) was responsible for the maintenance of imperial stables, horses, carriages, and coach-houses for the emperor and his palace attendants, as well as the supply of horses for the armed forces. The Minister of Justice (''Tíngwèi'' ) was the chief official in charge of upholding, administering, and interpreting the law. The Minister Herald (''Dà hónglú'' ) was the chief official in charge of receiving honored guests at the imperial court, such as nobles and Foreign relations of Imperial China, foreign ambassadors.

The Minister of the Imperial Clan (''Zōngzhèng'' ) oversaw the imperial court's interactions with the empire's nobility and extended imperial family, such as granting fiefs and titles. The Minister of Finance (''Dà sìnóng'' ) was the treasurer for the official bureaucracy and the armed forces who handled tax revenues and set standards for units of measurement. The Minister Steward (''Shǎofǔ'' ) served the emperor exclusively, providing him with entertainment and amusements, proper food and clothing, medicine and physical care, valuables and equipment.

The Minister of the Guards (''Wèiwèi'' ) was responsible for securing and patrolling the walls, towers, and gates of the imperial palaces. The Minister Coachman (''Tàipú'' ) was responsible for the maintenance of imperial stables, horses, carriages, and coach-houses for the emperor and his palace attendants, as well as the supply of horses for the armed forces. The Minister of Justice (''Tíngwèi'' ) was the chief official in charge of upholding, administering, and interpreting the law. The Minister Herald (''Dà hónglú'' ) was the chief official in charge of receiving honored guests at the imperial court, such as nobles and Foreign relations of Imperial China, foreign ambassadors.

The Minister of the Imperial Clan (''Zōngzhèng'' ) oversaw the imperial court's interactions with the empire's nobility and extended imperial family, such as granting fiefs and titles. The Minister of Finance (''Dà sìnóng'' ) was the treasurer for the official bureaucracy and the armed forces who handled tax revenues and set standards for units of measurement. The Minister Steward (''Shǎofǔ'' ) served the emperor exclusively, providing him with entertainment and amusements, proper food and clothing, medicine and physical care, valuables and equipment.

Up until the reign of Emperor Jing of Han, the Emperors of the Han had great difficulty bringing the vassal kings under control, as kings often switched their allegiance to the Xiongnu

Up until the reign of Emperor Jing of Han, the Emperors of the Han had great difficulty bringing the vassal kings under control, as kings often switched their allegiance to the Xiongnu

At the beginning of the Han dynasty, every male commoner aged twenty-three was liable for conscription into the military. The minimum age for the military draft was reduced to twenty after Emperor Zhao of Han, Emperor Zhao's ( BC) reign. Conscripted soldiers underwent one year of training and one year of service as non-professional soldiers. The year of training was served in one of three branches of the armed forces: infantry, cavalry, or navy. Soldiers who completed their term of service still needed to train to maintain their skill because they were subject to annual military readiness inspections and could be called up for future service - until this practice was discontinued after 30 AD with the abolishment of much of the conscription system. The year of active service was served either on the frontier, in a king's court, or under the Minister of the Guards in the capital. A small professional (full time career) standing army was stationed near the capital.

During the Eastern Han, conscription could be avoided if one paid a commutable tax. The Eastern Han court favored the recruitment of a volunteer military, volunteer army. The volunteer army comprised the Southern Army (''Nanjun'' 南軍), while the standing army stationed in and near the capital was the Northern Army (''Beijun'' 北軍). Led by Colonels (''Xiaowei'' 校尉), the Northern Army consisted of five regiments, each composed of several thousand soldiers. When central authority collapsed after 189 AD, wealthy landowners, members of the aristocracy/nobility, and regional military-governors relied upon their retainers to act as their own personal troops. The latter were known as 部曲, a special social class in Chinese history.

During times of war, the volunteer army was increased, and a much larger militia was raised across the country to supplement the Northern Army. In these circumstances, a General (''Jiangjun'' 將軍) led a Division (military), division, which was divided into regiments led by Colonels and sometimes Majors (''Sima'' 司馬). Regiments were divided into company (military unit), companies and led by Captains. Platoons were the smallest units of soldiers.

At the beginning of the Han dynasty, every male commoner aged twenty-three was liable for conscription into the military. The minimum age for the military draft was reduced to twenty after Emperor Zhao of Han, Emperor Zhao's ( BC) reign. Conscripted soldiers underwent one year of training and one year of service as non-professional soldiers. The year of training was served in one of three branches of the armed forces: infantry, cavalry, or navy. Soldiers who completed their term of service still needed to train to maintain their skill because they were subject to annual military readiness inspections and could be called up for future service - until this practice was discontinued after 30 AD with the abolishment of much of the conscription system. The year of active service was served either on the frontier, in a king's court, or under the Minister of the Guards in the capital. A small professional (full time career) standing army was stationed near the capital.

During the Eastern Han, conscription could be avoided if one paid a commutable tax. The Eastern Han court favored the recruitment of a volunteer military, volunteer army. The volunteer army comprised the Southern Army (''Nanjun'' 南軍), while the standing army stationed in and near the capital was the Northern Army (''Beijun'' 北軍). Led by Colonels (''Xiaowei'' 校尉), the Northern Army consisted of five regiments, each composed of several thousand soldiers. When central authority collapsed after 189 AD, wealthy landowners, members of the aristocracy/nobility, and regional military-governors relied upon their retainers to act as their own personal troops. The latter were known as 部曲, a special social class in Chinese history.

During times of war, the volunteer army was increased, and a much larger militia was raised across the country to supplement the Northern Army. In these circumstances, a General (''Jiangjun'' 將軍) led a Division (military), division, which was divided into regiments led by Colonels and sometimes Majors (''Sima'' 司馬). Regiments were divided into company (military unit), companies and led by Captains. Platoons were the smallest units of soldiers.

In the early Western Han, a wealthy salt or iron industrialist, whether a semi-autonomous king or wealthy merchant, could boast funds that rivaled the imperial treasury and amass a peasant workforce of over a thousand. This kept many peasants away from their farms and denied the government a significant portion of its land tax revenue. To eliminate the influence of such private entrepreneurs, Emperor Wu nationalized the salt and iron industries in 117 BC and allowed many of the former industrialists to become officials administering the state monopolies. By Eastern Han times, the central government monopolies were repealed in favor of production by commandery and county administrations, as well as private businessmen.

Liquor was another profitable private industry nationalized by the central government in 98 BC. However, this was repealed in 81 BC and a property tax rate of two coins for every 0.2 L (0.05 gallons) was levied for those who traded it privately. By 110 BC Emperor Wu also interfered with the profitable trade in grain when he eliminated speculation by selling government-stored grain at a lower price than that demanded by merchants. Apart from Emperor Ming's creation of a short-lived Office for Price Adjustment and Stabilization, which was abolished in 68 AD, central-government price control regulations were largely absent during the Eastern Han.

In the early Western Han, a wealthy salt or iron industrialist, whether a semi-autonomous king or wealthy merchant, could boast funds that rivaled the imperial treasury and amass a peasant workforce of over a thousand. This kept many peasants away from their farms and denied the government a significant portion of its land tax revenue. To eliminate the influence of such private entrepreneurs, Emperor Wu nationalized the salt and iron industries in 117 BC and allowed many of the former industrialists to become officials administering the state monopolies. By Eastern Han times, the central government monopolies were repealed in favor of production by commandery and county administrations, as well as private businessmen.

Liquor was another profitable private industry nationalized by the central government in 98 BC. However, this was repealed in 81 BC and a property tax rate of two coins for every 0.2 L (0.05 gallons) was levied for those who traded it privately. By 110 BC Emperor Wu also interfered with the profitable trade in grain when he eliminated speculation by selling government-stored grain at a lower price than that demanded by merchants. Apart from Emperor Ming's creation of a short-lived Office for Price Adjustment and Stabilization, which was abolished in 68 AD, central-government price control regulations were largely absent during the Eastern Han.

The Han dynasty was a unique period in the development of premodern Chinese science and technology, comparable to the level of Technology of the Song dynasty, scientific and technological growth during the Song dynasty (960–1279).

The Han dynasty was a unique period in the development of premodern Chinese science and technology, comparable to the level of Technology of the Song dynasty, scientific and technological growth during the Song dynasty (960–1279).

File:登封汉代少室阙.jpg, A pair of stone-carved Que (tower), ''que'' (闕) located at the temple of Mount Song in Dengfeng. (Eastern Han dynasty.)

File:幽州書佐秦君石闕 17.jpg, A pair of Han period stone-carved Que (tower), ''que'' (闕) located at Babaoshan, Beijing.

File:Gao Yi Que2.jpg, A stone-carved pillar-gate, or Que (tower), ''que'' (闕), 6 m (20 ft) in total height, located at the tomb of Gao Yi in Ya'an. (Eastern Han dynasty.)

File:Eastern Han tomb, Luoyang 2.jpg, An Eastern-Han Vault (architecture), vaulted tomb chamber at

File:Winnowing machine and tilt hammer.JPG, A Han-dynasty pottery model of two men operating a Fengshanche, winnowing machine with a Crank (mechanism), crank handle and a Trip hammer, tilt hammer used to pound grain.

File:EastHanSeismograph.JPG, A modern replica of Zhang Heng's

File:Western Han Mawangdui Silk Map.JPG, An early Western Han dynasty silk map found in tomb 3 of Mawangdui, depicting the Kingdom of

Han-era medical physicians believed that the human body was subject to the same forces of nature that governed the greater universe, namely the cosmological cycles of yin and yang and the Wuxing (Chinese philosophy), five phases. Each Zang-fu, organ of the body was associated with a particular phase. Illness was viewed as a sign that ''qi'' or "vital energy" channels leading to a certain organ had been disrupted. Thus, Han-era physicians prescribed medicine that was believed to counteract this imbalance.

For example, since the wood phase was believed to promote the fire phase, medicinal ingredients associated with the wood phase could be used to heal an organ associated with the fire phase. Besides dieting, Han physicians also prescribed moxibustion, acupuncture, and calisthenics as methods of maintaining one's health. When surgery was performed by the Chinese physician Hua Tuo (d. AD 208), he used anesthesia to numb his patients' pain and prescribed a rubbing ointment that allegedly sped the process of healing surgical wounds. Whereas the physician Zhang Zhongjing ( – ) is known to have written the ''Shanghan lun'' ("Dissertation on Typhoid Fever"), it is thought that both he and Hua Tuo collaborated in compiling the ''Shennong Ben Cao Jing'' medical text.

Han-era medical physicians believed that the human body was subject to the same forces of nature that governed the greater universe, namely the cosmological cycles of yin and yang and the Wuxing (Chinese philosophy), five phases. Each Zang-fu, organ of the body was associated with a particular phase. Illness was viewed as a sign that ''qi'' or "vital energy" channels leading to a certain organ had been disrupted. Thus, Han-era physicians prescribed medicine that was believed to counteract this imbalance.

For example, since the wood phase was believed to promote the fire phase, medicinal ingredients associated with the wood phase could be used to heal an organ associated with the fire phase. Besides dieting, Han physicians also prescribed moxibustion, acupuncture, and calisthenics as methods of maintaining one's health. When surgery was performed by the Chinese physician Hua Tuo (d. AD 208), he used anesthesia to numb his patients' pain and prescribed a rubbing ointment that allegedly sped the process of healing surgical wounds. Whereas the physician Zhang Zhongjing ( – ) is known to have written the ''Shanghan lun'' ("Dissertation on Typhoid Fever"), it is thought that both he and Hua Tuo collaborated in compiling the ''Shennong Ben Cao Jing'' medical text.

Han dynasty by Minnesota State UniversityHan dynasty art with video commentary, Minneapolis Institute of ArtsEarly Imperial China: A Working Collection of Resources

"Han Culture," Hanyangling Museum WebsiteThe Han Synthesis

BBC Radio 4 discussion with Christopher Cullen, Carol Michaelson & Roel Sterckx (''In Our Time'', Oct. 14, 2004) {{Authority control Han dynasty, States and territories established in the 3rd century BC States and territories disestablished in the 3rd century 1st century BC in China, . 1st century in China, . 2nd century BC in China, . 2nd century in China, . 200s BC establishments 206 BC 220 disestablishments 3rd-century BC establishments in China 3rd-century disestablishments in China 3rd century BC in China, . Dynasties in Chinese history Former countries in Chinese history

Fergana

Fergana ( uz, Fargʻona/Фарғона, ), or Ferghana, is a district-level city and the capital of Fergana Region in eastern Uzbekistan. Fergana is about 420 km east of Tashkent, about 75 km west of Andijan, and less than 20 km ...

), Kangju ( Sogdiana), and Daxia (Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, so ...

, formerly the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic-era Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Hellenistic world in Central Asia and the Ind ...

); he also gathered information on Shendu (Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kash ...

valley of North India

North India is a loosely defined region consisting of the northern part of India. The dominant geographical features of North India are the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayas, which demarcate the region from the Tibetan Plateau and Centr ...

) and Anxi (the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conq ...

). All of these countries eventually received Han embassies. These connections marked the beginning of the Silk Road trade network that extended to the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

, bringing Han items like silk to Rome and Roman goods such as glasswares to China.

From roughly 115 to 60 BC, Han forces fought the Xiongnu over control of the oasis city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s in the Tarim Basin. The Han was eventually victorious and established the Protectorate of the Western Regions in 60 BC, which dealt with the region's defense and foreign affairs. The Han also expanded southward. The naval conquest of Nanyue in 111 BC expanded the Han realm into what are now modern Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020 ...

, Guangxi, and northern Vietnam. Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the ...

was brought into the Han realm with the conquest of the Dian Kingdom in 109 BC, followed by parts of the Korean Peninsula

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

with the Han conquest of Gojoseon and colonial establishments of Xuantu Commandery

Xuantu Commandery (; ko, 현도군) was a commandery of the Chinese Han dynasty. It was one of Four Commanderies of Han, established in 107 BCE in the northern Korean Peninsula and part of the Liaodong Peninsula, after the Han dynasty conquer ...

and Lelang Commandery in 108 BC. In China's first known nationwide census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses in ...

taken in 2 AD, the population was registered as having 57,671,400 individuals in 12,366,470 households.

To pay for his military campaigns and colonial expansion, Emperor Wu nationalized

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to priv ...

several private industries. He created central government monopolies administered largely by former merchants. These monopolies included salt, iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

, and liquor

Liquor (or a spirit) is an alcoholic drink produced by distillation of grains, fruits, vegetables, or sugar, that have already gone through alcoholic fermentation. Other terms for liquor include: spirit drink, distilled beverage or ha ...

production, as well as bronze-coin currency. The liquor monopoly lasted only from 98 to 81 BC, and the salt and iron monopolies were eventually abolished in the early Eastern Han. The issuing of coinage remained a central government monopoly throughout the rest of the Han dynasty.

The government monopolies were eventually repealed when a political faction known as the Reformists gained greater influence in the court. The Reformists opposed the Modernist faction that had dominated court politics in Emperor Wu's reign and during the subsequent regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

of Huo Guang (d. 68 BC). The Modernists argued for an aggressive and expansionary foreign policy supported by revenues from heavy government intervention in the private economy. The Reformists, however, overturned these policies, favoring a cautious, non-expansionary approach to foreign policy, frugal budget

A budget is a calculation play, usually but not always financial, for a defined period, often one year or a month. A budget may include anticipated sales volumes and revenues, resource quantities including time, costs and expenses, environme ...

reform, and lower tax-rates imposed on private entrepreneurs.

Wang Mang's reign and civil war

Wang Zhengjun (71 BC – 13 AD) was first empress, then empress dowager, and finally grand empress dowager during the reigns of the Emperors Yuan ( BC), Cheng ( BC), and Ai ( BC), respectively. During this time, a succession of her male relatives held the title of regent. Following the death of Ai, Wang Zhengjun's nephew

Wang Zhengjun (71 BC – 13 AD) was first empress, then empress dowager, and finally grand empress dowager during the reigns of the Emperors Yuan ( BC), Cheng ( BC), and Ai ( BC), respectively. During this time, a succession of her male relatives held the title of regent. Following the death of Ai, Wang Zhengjun's nephew Wang Mang

Wang Mang () (c. 45 – 6 October 23 CE), courtesy name Jujun (), was the founder and the only emperor of the short-lived Chinese Xin dynasty. He was originally an official and consort kin of the Han dynasty and later seized the thro ...

(45 BC – 23 AD) was appointed regent as Marshall of State on 16 August under Emperor Ping ( AD).

When Ping died on 3 February 6 AD, Ruzi Ying (d. 25 AD) was chosen as the heir and Wang Mang was appointed to serve as acting emperor for the child. Wang promised to relinquish his control to Liu Ying once he came of age. Despite this promise, and against protest and revolts from the nobility, Wang Mang claimed on 10 January that the divine Mandate of Heaven

The Mandate of Heaven () is a Chinese political philosophy that was used in ancient and imperial China to legitimize the rule of the King or Emperor of China. According to this doctrine, heaven (天, '' Tian'') – which embodies the natur ...

called for the end of the Han dynasty and the beginning of his own: the Xin dynasty

The Xin dynasty (; ), also known as Xin Mang () in Chinese historiography, was a short-lived Chinese imperial dynasty which lasted from 9 to 23 AD, established by the Han dynasty consort kin Wang Mang, who usurped the throne of the Emperor Ping ...

(9–23 AD).

Wang Mang initiated a series of major reforms that were ultimately unsuccessful. These reforms included outlawing slavery, nationalizing land to equally distribute between households, and introducing new currencies, a change which debased the value of coinage. Although these reforms provoked considerable opposition, Wang's regime met its ultimate downfall with the massive floods of AD and 11 AD. Gradual silt buildup in the Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the sixth-longest river system in the world at the estimated length of . Originating in the Bayan ...

had raised its water level and overwhelmed the flood control works. The Yellow River split into two new branches: one emptying to the north and the other to the south of the Shandong Peninsula

The Shandong (Shantung) Peninsula or Jiaodong (Chiaotung) Peninsula is a peninsula in Shandong Province in eastern China, between the Bohai Sea to the north and the Yellow Sea to the south. The latter name refers to the east and Jiaozhou.

Geo ...

, though Han engineers managed to dam the southern branch by 70 AD.

The flood dislodged thousands of peasant farmers, many of whom joined roving bandit and rebel groups such as the Red Eyebrows to survive. Wang Mang's armies were incapable of quelling these enlarged rebel groups. Eventually, an insurgent mob forced their way into the Weiyang Palace and killed Wang Mang.

The Gengshi Emperor ( AD), a descendant of Emperor Jing ( BC), attempted to restore the Han dynasty and occupied Chang'an as his capital. However, he was overwhelmed by the Red Eyebrow rebels who deposed, assassinated, and replaced him with the puppet monarch Liu Penzi. Gengshi's distant cousin Liu Xiu, known posthumously as Emperor Guangwu ( AD), after distinguishing himself at the Battle of Kunyang

The Battle of Kunyang () was fought during June and July in 23 AD, between the Lulin and Xin forces. The Lulin forces were led by Liu Xiu, who later became Emperor Guangwu of Han, while the far more numerous Xin were led by Wang Yi and Wang Xun ...

in 23 AD, was urged to succeed Gengshi as emperor.

Under Guangwu's rule the Han Empire was restored. Guangwu made Luoyang

Luoyang is a city located in the confluence area of Luo River (Henan), Luo River and Yellow River in the west of Henan province. Governed as a prefecture-level city, it borders the provincial capital of Zhengzhou to the east, Pingdingshan to the ...

his capital in 25 AD, and by 27 AD his officers Deng Yu

Deng Yu (2–58 CE), courtesy name Zhonghua, was a Chinese statesman and military commander of the early Eastern Han dynasty who was instrumental in Emperor Guangwu's reunification of China. Although acquainted during his childhood with Liu Xiu, ...

and Feng Yi had forced the Red Eyebrows to surrender and executed their leaders for treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. From 26 until 36 AD, Emperor Guangwu had to wage war against other regional warlords who claimed the title of emperor; when these warlords were defeated, China reunified under the Han.

The period between the foundation of the Han dynasty and Wang Mang's reign is known as the Western Han () or Former Han () (206 BC – 9 AD). During this period the capital was at Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin ...

(modern Xi'an