Dunkirk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

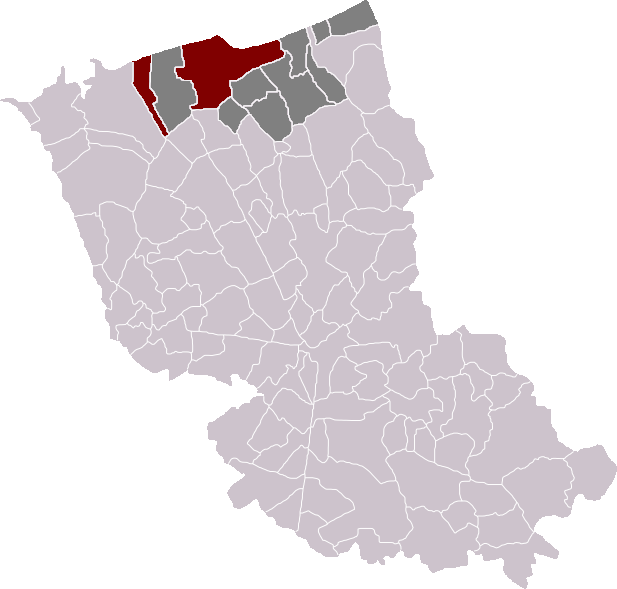

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=

INSEE It lies from the

A

A

The area remained much disputed between the

The area remained much disputed between the

French Flemish

French Flemish (French Flemish: , Standard Dutch: , french: flamand français) is a West Flemish dialect spoken in the north of contemporary France. Place names attest to Flemish having been spoken since the 8th century in the part of Fland ...

, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

in the department of Nord in northern France.Commune de Dunkerque (59183)INSEE It lies from the

Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

border. It has the third-largest French harbour. The population of the commune in 2019 was 86,279.

Etymology and language use

The name of Dunkirk derives fromWest Flemish

West Flemish (''West-Vlams'' or ''West-Vloams'' or ''Vlaemsch'' (in French-Flanders), nl, West-Vlaams, french: link=no, flamand occidental) is a collection of Dutch dialects spoken in western Belgium and the neighbouring areas of France and ...

'dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, f ...

' or 'dun

A dun is an ancient or medieval fort. In Ireland and Britain it is mainly a kind of hillfort and also a kind of Atlantic roundhouse.

Etymology

The term comes from Irish ''dún'' or Scottish Gaelic ''dùn'' (meaning "fort"), and is cognat ...

' and 'church', thus 'church in the dunes'. A smaller town 25 km farther up the Flemish coast originally shared the same name, but was later renamed Oostduinkerke

Oostduinkerke (; french: Ostdunkerque ; vls, Ôostduunkerke) is a place in the Belgian province of West Flanders, where it is located on the southern west coast of Belgium.

Once a municipality of its own, Oostduinkerke now is a sub-municipali ...

(n) in order to avoid confusion.

Until the middle of the 20th century, French Flemish

French Flemish (French Flemish: , Standard Dutch: , french: flamand français) is a West Flemish dialect spoken in the north of contemporary France. Place names attest to Flemish having been spoken since the 8th century in the part of Fland ...

(the local variety of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

) was commonly spoken.

History

Middle Ages

fishing village

A fishing village is a village, usually located near a fishing ground, with an economy based on catching fish and harvesting seafood. The continents and islands around the world have coastlines totalling around 356,000 kilometres (221,000 ...

arose late in the tenth century, in the originally flooded coastal area of the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

south of the Western Scheldt

The Western Scheldt ( nl, Westerschelde) in the province of Zeeland in the southwestern Netherlands, is the estuary of the Scheldt river. This river once had several estuaries, but the others are now disconnected from the Scheldt, leaving the W ...

, when the area was held by the Counts of Flanders

The count of Flanders was the ruler or sub-ruler of the county of Flanders, beginning in the 9th century. Later, the title would be held for a time, by the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. During the French Revolution, in 1790, the co ...

, vassals of the French Crown. About AD 960, Count Baldwin III had a town wall erected in order to protect the settlement against Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

raids. The surrounding wetlands were drained and cultivated by the monks of nearby Bergues

Bergues (; nl, Sint-Winoksbergen; vls, Bergn) is a commune in the Nord department in northern France.

It is situated to the south of Dunkirk and from the Belgian border. Locally it is referred to as "the other Bruges in Flanders". Bergues ...

Abbey. The name ''Dunkirka'' was first mentioned in a tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

privilege of 27 May 1067, issued by Count Baldwin V of Flanders. Count Philip I Philip(p) I may refer to:

* Philip I of Macedon (7th century BC)

* Philip I Philadelphus (between 124 and 109 BC–83 or 75 BC)

* Philip the Arab (c. 204–249), Roman Emperor

* Philip I of France (1052–1108)

* Philip I (archbishop of Cologne) (1 ...

(1157–1191) brought further large tracts of marshland under cultivation, laid out the first plans to build a Canal from Dunkirk to Bergues and vested the Dunkirkers with market rights

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural ...

.

In the late 13th century, when the Dampierre count Guy of Flanders

Guy of Dampierre (french: Gui de Dampierre; nl, Gwijde van Dampierre) ( – 7 March 1305, Compiègne) was the Count of Flanders (1251–1305) and List of rulers of Namur, Marquis of Namur (1264–1305). He was a prisoner of the French when ...

entered into the Franco-Flemish War against his suzerain King Philippe IV

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (french: Philippe le Bel), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre as Philip I from 1 ...

of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the citizens of Dunkirk sided with the French against their count, who at first was defeated at the 1297 Battle of Furnes

The Battle of Furnes, also known as ''Battle of Veurne'' and ''Battle of Bulskamp'', was fought on 20 August 1297 between French and Flemish forces.

The French were led by Robert II of Artois and the Flemish by Guy of Dampierre. The French fo ...

, but reached ''de facto'' autonomy upon the victorious Battle of the Golden Spurs five years later and exacted vengeance. Guy's son, Count Robert III (1305–1322), nevertheless granted further city rights to Dunkirk; his successor Count Louis I Louis I may refer to:

* Louis the Pious, Louis I of France, "the Pious" (778–840), king of France and Holy Roman Emperor

* Louis I, Landgrave of Thuringia (ruled 1123–1140)

* Ludwig I, Count of Württemberg (c. 1098–1158)

* Louis I of Blois ...

(1322–1346) had to face the Peasant revolt of 1323–1328, which was crushed by King Philippe VI

Philip VI (french: Philippe; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (french: le Fortuné, link=no) or the Catholic (french: le Catholique, link=no) and of Valois, was the first king of France from the House of Valois, reigning from 132 ...

of France at the 1328 Battle of Cassel, whereafter the Dunkirkers again were affected by the repressive measures of the French king.

Count Louis remained a loyal vassal of the French king upon the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a series of armed conflicts between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France during the Late Middle Ages. It originated from disputed claims to the French Crown, ...

with England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in 1337, and prohibited the maritime trade, which led to another revolt by the Dunkirk citizens. After the count had been killed in the 1346 Battle of Crécy

The Battle of Crécy took place on 26 August 1346 in northern France between a French army commanded by King PhilipVI and an English army led by King EdwardIII. The French attacked the English while they were traversing northern France du ...

, his son and successor Count Louis II of Flanders

Louis II ( nl, Lodewijk van Male; french: Louis II de Flandre) (25 October 1330, Male – 30 January 1384, Lille), also known as Louis of Male, a member of the House of Dampierre, was Count of Flanders, Nevers and Rethel from 1346 as well as ...

(1346–1384) signed a truce with the English; the trade again flourished and the port was significantly enlarged. However, in the course of the Western Schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Vatican Standoff, the Great Occidental Schism, or the Schism of 1378 (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417 in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon bo ...

from 1378, English supporters of Pope Urban VI

Pope Urban VI ( la, Urbanus VI; it, Urbano VI; c. 1318 – 15 October 1389), born Bartolomeo Prignano (), was head of the Catholic Church from 8 April 1378 to his death in October 1389. He was the most recent pope to be elected from outside the ...

(the Roman claimant) disembarked at Dunkirk, captured the city and flooded the surrounding estates. They were ejected by King Charles VI of France

Charles VI (3 December 136821 October 1422), nicknamed the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé) and later the Mad (french: le Fol or ''le Fou''), was King of France from 1380 until his death in 1422. He is known for his mental illness and psychotic ...

, but left great devastations in and around the town.

Upon the extinction of the Counts of Flanders with the death of Louis II in 1384, Flanders was acquired by the Burgundian, Duke Philip the Bold

Philip II the Bold (; ; 17 January 1342 – 27 April 1404) was Duke of Burgundy and '' jure uxoris'' Count of Flanders, Artois and Burgundy. He was the fourth and youngest son of King John II of France and Bonne of Luxembourg.

Philip II was ...

. The fortifications were again enlarged, including the construction of a belfry daymark

A daymark is a navigational aid for sailors and pilots, distinctively marked to maximize its visibility in daylight.

The word is also used in a more specific, technical sense to refer to a signboard or daytime identifier that is attached to ...

(a navigational aid similar to a non-illuminated lighthouse). As a strategic point, Dunkirk has always been exposed to political greed, by Duke Robert I of Bar

Robert I of Bar (8 November 1344 – 12 April 1411) was Marquis of Pont-à-Mousson and Count and then Duke of Bar. He succeeded his elder brother Edward II of Bar as count in 1352. His parents were Henry IV of Bar and Yolande of Flanders.

Whe ...

in 1395, by Louis de Luxembourg in 1435 and finally by the Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

archduke Maximilian I of Habsburg

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death. He was never crowned by the pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians. He proclaimed himself Ele ...

, who in 1477 married Mary of Burgundy

Mary (french: Marie; nl, Maria; 13 February 1457 – 27 March 1482), nicknamed the Rich, was a member of the House of Valois-Burgundy who ruled a collection of states that included the duchies of Limburg, Brabant, Luxembourg, the counties of ...

, sole heiress of late Duke Charles the Bold

Charles I (Charles Martin; german: Karl Martin; nl, Karel Maarten; 10 November 1433 – 5 January 1477), nicknamed the Bold (German: ''der Kühne''; Dutch: ''de Stoute''; french: le Téméraire), was Duke of Burgundy from 1467 to 1477.

...

. As Maximilian was the son of Emperor Frederick III, all Flanders was immediately seized by King Louis XI of France

Louis XI (3 July 1423 – 30 August 1483), called "Louis the Prudent" (french: le Prudent), was King of France from 1461 to 1483. He succeeded his father, Charles VII.

Louis entered into open rebellion against his father in a short-lived revo ...

. However, the archduke defeated the French troops in 1479 at the Battle of Guinegate. When Mary died in 1482, Maximilian retained Flanders according to the terms of the 1482 Treaty of Arras. Dunkirk, along with the rest of Flanders, was incorporated into the Habsburg Netherlands

Habsburg Netherlands was the Renaissance period fiefs in the Low Countries held by the Holy Roman Empire's House of Habsburg. The rule began in 1482, when the last House of Valois-Burgundy, Valois-Burgundy ruler of the Netherlands, Mary of Burgu ...

and upon the 1581 secession of the Seven United Netherlands, remained part of the Southern Netherlands

The Southern Netherlands, also called the Catholic Netherlands, were the parts of the Low Countries belonging to the Holy Roman Empire which were at first largely controlled by Habsburg Spain (Spanish Netherlands, 1556–1714) and later by the A ...

, which were held by Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain is a contemporary historiographical term referring to the huge extent of territories (including modern-day Spain, a piece of south-east France, eventually Portugal, and many other lands outside of the Iberian Peninsula) ruled be ...

(Spanish Netherlands) as Imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texa ...

fiefs.

Corsair base

Kingdom of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, the United Netherlands, the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

and the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

. At the beginning of the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Refo ...

, Dunkirk was briefly in the hands of the Dutch rebels, from 1577. Spanish forces under Duke Alexander Farnese Alessandro Farnese may refer to:

* Pope Paul III (1468–1549), Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome

*Alessandro Farnese (cardinal) (1520–1589), Paul's grandson, Roman Catholic bishop and cardinal-nephew

* Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma (1545–1592), ...

of Parma

Parma (; egl, Pärma, ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmigiano-Reggiano, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,292 ...

re-established Spanish rule in 1583 and it became a base for the notorious ''Dunkirkers''. The Dunkirkers briefly lost their home port when the city was conquered by the French in 1646 but Spanish forces recaptured the city in 1652. In 1658, as a result of the long war between France and Spain, it was captured after a siege by Franco-English forces following the battle of the Dunes. The city along with Fort-Mardyck

Fort-Mardyck (; ; vls, Fort-Mardyk) is a former commune in the Nord department in northern France. It has been part of the commune of Dunkirk since 9 December 2010. In 2019 it had 3,403 inhabitants.the peace the following year as agreed in the Franco-English alliance against Spain. The English governors were Sir William Lockhart (1658–60), Sir Edward Harley (1660–61) and

Dunkirk was again contested in 1944, with the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division attempting to liberate the city in September, as Allied forces surged northeast after their victory in the

Dunkirk was again contested in 1944, with the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division attempting to liberate the city in September, as Allied forces surged northeast after their victory in the

Lord Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

(1661–62).

On 17 October 1662, Dunkirk was sold to France by Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651, and King of England, Scotland and Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest surviving child of ...

for £320,000. The French government developed the town as a fortified port. The town's existing defences were adapted to create ten bastions. The port was expanded in the 1670s by the construction of a basin that could hold up to thirty warships with a double lock system to maintain water levels at low tide. The basin was linked to the sea by a channel dug through coastal sandbanks secured by two jetties. This work was completed by 1678. The jetties were defended a few years later by the construction of five forts, Château d'Espérance, Château Vert, Grand Risban, Château Gaillard, and Fort de Revers. An additional fort was built in 1701 called Fort Blanc.

During the reign of Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

, a large number of commerce raider

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than enga ...

s and pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

s once again made their base at Dunkirk, the most famous of whom was Jean Bart

Jean Bart (; ; 21 October 1650 – 27 April 1702) was a French Admiral, naval commander and privateer.

Early life

Jean Bart was born in Dunkirk, France, Dunkirk in 1650 to a seafaring family, the son of Jean-Cornil Bart (c. 1619-1668) who has b ...

. The main character (and possible real prisoner) in the famous novel Man in the Iron Mask

The Man in the Iron Mask (French ; died 19 November 1703) was an unidentified prisoner of state during the reign of King Louis XIV of France (1643–1715). Warranted for arrest on 28 July 1669 under the pseudonym of "Eustache Dauger", he wa ...

by Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (, ; ; born Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (), 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas père (where '' '' is French for 'father', to distinguish him from his son Alexandre Dumas fils), was a French writer ...

was arrested at Dunkirk. The eighteenth-century Swedish privateers and pirates Lars Gathenhielm

Lars Gathenhielm (originally Lars Andersson Gathe; 1689–1718) was a Swedish sea captain, commander, shipowner merchant, and privateer.

Biography

Lars Gathenhielm was born on the Gatan estate in Onsala Parish in Halland. His parents were th ...

and his wife Ingela Hammar are known to have sold their gains in Dunkirk.

As France and Great Britain became commercial and military rivals, the British grew concerned about Dunkirk being used as an invasion base to cross the English Channel. The jetties, their forts, and the port facilities were demolished in 1713 under the terms of the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne o ...

.

The Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

of 1763, which concluded the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, included a clause restricting French rights to fortify Dunkirk. This clause was overturned in the subsequent Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

of 1783.

Dunkirk in World War I

Dunkirk's port was used extensively during the war by British forces who brought in dock workers from, among other places, Egypt and China. From 1915, the city experienced severe bombardment, including from the largest gun in the world in 1917, the German ' Lange Max'. On a regular basis, heavy shells weighing approximately 750 kg were fired fromKoekelare

Koekelare (; vls, Kookloare) is a municipality located in the Belgian province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the towns of Bovekerke, Koekelare proper and Zande. On 1 January 2006 Koekelare had a total population of 8,291. The tota ...

, about 45–50 km away. The bombardment killed nearly 600 people and wounded another 1,100, both civilian and military, while 400 buildings were destroyed and 2,400 damaged. The city's population, which had been 39,000 in 1914, reduced to fewer than 15,000 in July 1916 and 7,000 in the autumn of 1917.

In January, 1916, a spy scare took place in Dunkirk. The writer Robert W. Service

Robert William Service (January 16, 1874 – September 11, 1958) was a British-Canadian poet and writer, often called "the Bard of the Yukon". The middle name 'William' was in honour of a rich uncle. When that uncle neglected to provide for hi ...

, then a war correspondent for the ''Toronto Star

The ''Toronto Star'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet daily newspaper. The newspaper is the country's largest daily newspaper by circulation. It is owned by Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary of Torstar Corporation and part ...

'', was mistakenly arrested as a spy and narrowly avoided being executed out of hand. On 1 January 1918, the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

established a naval air station to operate seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tec ...

s. The base closed shortly after the Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

.

In October 1917, to mark the gallant behaviour of its inhabitants during the war, the City of Dunkirk was awarded the Croix de Guerre and, in 1919, the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon, ...

and the British Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is a military decoration awarded to ...

. These decorations now appear in the city's coat of arms.

Dunkirk in World War II

Evacuation

During theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, in the May 1940 Battle of France, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), while aiding the French and Belgian armies, were forced to retreat in the face of the overpowering German Panzer attacks. Fighting in Belgium and France, the BEF and a portion of the French Army became outflanked by the Germans and retreated to the area around the port of Dunkirk. More than 400,000 soldiers were trapped in the pocket as the German Army closed in for the kill. Unexpectedly, the German Panzer attack halted for several days at a critical juncture. For years, it was assumed that Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

ordered the German Army to suspend the attack, favouring bombardment by the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

. However, according to the Official War Diary of Army Group A

Army Group A (Heeresgruppe A) was the name of several German Army Groups during World War II. During the Battle of France, the army group named Army Group A was composed of 45½ divisions, including 7 armored panzer divisions. It was responsibl ...

, its commander, ''Generaloberst

A ("colonel general") was the second-highest general officer rank in the German ''Reichswehr'' and ''Wehrmacht'', the Austro-Hungarian Common Army, the East German National People's Army and in their respective police services. The rank was ...

'' Gerd von Rundstedt

Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt (12 December 1875 – 24 February 1953) was a German field marshal in the '' Heer'' (Army) of Nazi Germany during World War II.

Born into a Prussian family with a long military tradition, Rundstedt entered th ...

, ordered the halt to allow maintenance on his tanks, half of which were out of service, and to protect his flanks which were exposed and, he thought, vulnerable. Hitler merely validated the order several hours later. This lull gave the British and French a few days to fortify their defences. The Allied position was complicated by Belgian King Leopold III's surrender on 27 May, which was postponed until 28 May. The gap left by the Belgian Army stretched from Ypres to Dixmude. Nevertheless, a collapse was prevented, making it possible to launch an evacuation by sea, across the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

, codenamed Operation Dynamo

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, the British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

, ordered any ship or boat available, large or small, to collect the stranded soldiers. 338,226 men (including 123,000 French soldiers) were evacuated – the ''miracle of Dunkirk'', as Churchill called it. It took over 900 vessels to evacuate the BEF, with two-thirds of those rescued embarking via the harbour, and over 100,000 taken off the beaches. More than 40,000 vehicles as well as massive amounts of other military equipment and supplies were left behind. Forty thousand Allied soldiers (some who carried on fighting after the official evacuation) were captured or forced to make their own way home through a variety of routes including via neutral Spain. Many wounded who were unable to walk were abandoned.

Liberation

Dunkirk was again contested in 1944, with the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division attempting to liberate the city in September, as Allied forces surged northeast after their victory in the

Dunkirk was again contested in 1944, with the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division attempting to liberate the city in September, as Allied forces surged northeast after their victory in the Battle of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

. However, German forces refused to relinquish their control of the city, which had been converted into a fortress. To seize the now strategically insignificant town would consume too many Allied resources which were needed elsewhere. The town was by-passed masking the German garrison with Allied troops, notably the 1st Czechoslovak Armoured Brigade. During the German occupation

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

, Dunkirk was largely destroyed by Allied bombing. The artillery siege of Dunkirk was directed on the final day of the war by pilots from No. 652 Squadron RAF

No. 652 Squadron RAF was a unit of the Royal Air Force during the Second World War and afterwards in Germany.

Numbers 651 to 663 Squadrons of the RAF were Air Observation Post units working closely with Army units in artillery spotting and liaiso ...

, and No. 665 Squadron RCAF

No. 665 "Air Observation Post" Squadron, RCAF was formed in England during the Second World War. It was manned principally by Royal Canadian Artillery (RCA) and Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) personnel, with select British artillery pilots brief ...

. The fortress, under the command of German Admiral Friedrich Frisius

Friedrich Frisius (17 January 1895 – 30 August 1970) was a German naval commander of World War II.

Life

Born in 1895 in Bad Salzuflen, son of the Lutheran pastor Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Frisius and his wife Karoline Luise Antoinette, Frisius ente ...

, eventually unconditionally surrendered to the commander of the Czechoslovak forces, Brigade General Alois Liška

Alois Liška (1895-1977) was a Czech army officer who served in both World Wars, ultimately as a Brigade General commanding the 1st Czechoslovak Armoured Brigade at Dunkirk in 1944–45. He was born on 20 November 1895 in Záborčí, some 17 kilo ...

, on 9 May 1945.

Postwar Dunkirk

On 14 December 2002, the Norwegiancar carrier

Roll-on/roll-off (RORO or ro-ro) ships are cargo ships designed to carry wheeled cargo, such as cars, motorcycles, trucks, semi-trailer trucks, buses, trailers, and railroad cars, that are driven on and off the ship on their own wheels or usin ...

collided with the Bahamian-registered ''Kariba'' and sank off Dunkirk Harbour, causing a hazard to navigation in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

.

Population

The population data in the table and graph below refer to the commune of Dunkirk proper, in its geography at the given years. The commune of Dunkirk absorbed the former commune of Malo-les-Bains in 1969,Rosendaël

Rosendaël ( nl, Rozendaal, vls, Rozendoale, French Flemish: ; meaning "rose valley") is a former commune in the Nord department in northern France. In 1971 it was merged into Dunkirk. It currently has 18,272 inhabitants (an almost ten-fold inc ...

and Petite-Synthe Petite-Synthe (; vls, Klein-Sinten, lang) is a former commune of the Nord ''département'' in northern France.

The commune of Saint-Pol-sur-Mer was created in 1877, by its territory being detached from Petite-Synthe. In 1971 the commune of Dunker ...

in 1971, Mardyck

Mardyck (Dutch: ''Mardijk'', vls, Mardyk) is a former commune in the Nord department in northern France. It is an associated commune with Dunkirk since it joined the latter in January 1980.Fort-Mardyck

Fort-Mardyck (; ; vls, Fort-Mardyk) is a former commune in the Nord department in northern France. It has been part of the commune of Dunkirk since 9 December 2010. In 2019 it had 3,403 inhabitants.Saint-Pol-sur-Mer

Saint-Pol-sur-Mer ( vls, Sint-Pols, lang) is a former commune in the Nord department in northern France. Since 9 December 2010, it is part of the commune of Dunkirk.Nord's 13th constituency, The current

The commune has grown substantially by absorbing several neighbouring communes:

* 1970: Merger with Malo-les-Bains (which had been created by being detached from Dunkirk in 1881)

* 1972: Fusion with

The commune has grown substantially by absorbing several neighbouring communes:

* 1970: Merger with Malo-les-Bains (which had been created by being detached from Dunkirk in 1881)

* 1972: Fusion with

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

is Christine Decodts of the miscellaneous centre

Miscellaneous centre (''Divers center'', ''DVC'') in France refers to centrist candidates who are not members of any large party. It is a nuance and ''de facto'' a political label created by the French Ministry of the Interior in 2020.

Affilia ...

.

Presidential elections second round

Heraldry

Administration

Petite-Synthe Petite-Synthe (; vls, Klein-Sinten, lang) is a former commune of the Nord ''département'' in northern France.

The commune of Saint-Pol-sur-Mer was created in 1877, by its territory being detached from Petite-Synthe. In 1971 the commune of Dunker ...

and Rosendaël (the latter had been created by being detached from Téteghem

Téteghem (; Dutch and vls, Tetegem) is a former commune in the Nord department, northern France. On 1 January 2016, it was merged into the new commune Téteghem-Coudekerque-Village.associated commune, with a population of 372 in 1999)

* 1980: A large part of Petite-Synthe is detached from Dunkirk and included into

In June 1792 the French astronomers

In June 1792 the French astronomers

File:Dunkerque Tour du Leughenaer.jpg, The Tour du Leughenaer () (the Liar's Tower)

File:Dunkerque Town Hall.jpg, Dunkirk Town Hall

File:Carnaval dunkerque.jpg, Carnival in Dunkirk

File:Jielbeaumadier Dunkerque 2007 25.jpeg, Malo-les-Bains beach front

File:Dunkerque (plage).jpg, Dunkirk Beach

File:East Mole Dunkirk.jpg, The remains of the East Mole of Dunkirk harbour, pictured in 2009

*

*

City council website

Tourist office website

{{Authority control Dunkirk, Communes of Nord (French department) France–United Kingdom border crossings Port cities and towns on the French Atlantic coast Port cities and towns of the North Sea Subprefectures in France Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Juxtaposed border controls Pirate dens and locations Vauban fortifications in France French Flanders

Grande-Synthe

Grande-Synthe (; vls, Groot-Sinten) is a commune in the Nord department in the Nord-Pas de Calais region in northern France.

It is the third-largest suburb of the city of Dunkerque (Dunkirk) and lies adjacent to it on the west.

History

In ...

* 2010: After a failed fusion-association attempt with Saint-Pol-sur-Mer

Saint-Pol-sur-Mer ( vls, Sint-Pols, lang) is a former commune in the Nord department in northern France. Since 9 December 2010, it is part of the commune of Dunkirk.Fort-Mardyck

Fort-Mardyck (; ; vls, Fort-Mardyk) is a former commune in the Nord department in northern France. It has been part of the commune of Dunkirk since 9 December 2010. In 2019 it had 3,403 inhabitants.Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very cl ...

and Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

. As an industrial city, it depends heavily on the steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

, food processing

Food processing is the transformation of agricultural products into food, or of one form of food into other forms. Food processing includes many forms of processing foods, from grinding grain to make raw flour to home cooking to complex industr ...

, oil-refining, ship-building

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befor ...

and chemical

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., w ...

industries.

Cuisine

The cuisine of Dunkirk closely resemblesFlemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

cuisine

A cuisine is a style of cooking characterized by distinctive ingredients, techniques and dishes, and usually associated with a specific culture or geographic region. Regional food preparation techniques, customs, and ingredients combine to ...

; perhaps one of the best known dishes is ''coq à la bière'' – chicken in a creamy beer sauce.

Prototype metre

Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre

Jean Baptiste Joseph, chevalier Delambre (19 September 1749 – 19 August 1822) was a French mathematician, astronomer, historian of astronomy, and geodesist. He was also director of the Paris Observatory, and author of well-known books on t ...

and Pierre François André Méchain set out to measure the meridian arc distance from Dunkirk to Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

, two cities lying on approximately the same longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east–west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek letter l ...

as each other and also the longitude through Paris. The belfry was chosen as the reference point in Dunkirk.

Using this measurement and the latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

s of the two cities they could calculate the distance between the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

and the Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

in classical French units of length and hence produce the first prototype metre

The metre (British spelling) or meter (American spelling; see spelling differences) (from the French unit , from the Greek noun , "measure"), symbol m, is the primary unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), though its pref ...

which was defined as being one ten millionth of that distance. The definitive metre bar, manufactured from platinum, was presented to the French legislative assembly on 22 June 1799.

Dunkirk was the most easterly cross-channel measuring point for the Anglo-French Survey (1784–1790)

The Anglo-French Survey (1784–1790) was the geodetic survey to measure the relative position of Greenwich Observatory and the Paris Observatory via triangulation. The English operations, executed by William Roy, consisted of the measureme ...

, which used triangulation to calculate the precise distance between the Paris Observatory and the Royal Greenwich Observatory. Sightings were made of signal lights at Dover Castle

Dover Castle is a medieval castle in Dover, Kent, England and is Grade I listed. It was founded in the 11th century and has been described as the "Key to England" due to its defensive significance throughout history. Some sources say it is the ...

from the Dunkirk Belfry, and vice versa.

Tourist attractions

Two belfries in Dunkirk (the belfry near the Church of Saint-Éloi and the one at the town hall) are part of a group ofbelfries of Belgium and France

The Belfries of Belgium and France are a group of 56 historical buildings designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, in recognition of the civic (rather than church) belfries serving as an architectural manifestation of emerging civic indep ...

, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2005 in recognition of their civic architecture and importance in the rise of municipal power in Europe.

The 63 meter high Dunkirk Lighthouse, also known as the Risban Light, was built between 1838 to 1843 as part of early efforts to place lights around the coast of France. At the time of its construction it was one of only two first order lighthouses (the other being Calais) to be set up in a port. Automated since 1985, the light can be seen 28 nautical miles (48 km) away. In 2010 it was listed as an historical monument.

Two museums in Dunkirk include:

* The ''Musée Portuaire'', which displays exhibits of images about the history and presence of the port.

* The ''Musée des Beaux-Arts'', which has a large collection of Flemish, Italian and French paintings and sculptures.

Transport

Dunkirk has a ferry route toDover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

that is run by DFDS

DFDS is a Danish international shipping and logistics company. It is the busiest shipping company of its kind in Northern Europe and one of the busiest in Europe. The company's name is an abbreviation of Det Forenede Dampskibs-Selskab (literall ...

, which serves as an alternative to the route to the service to nearby Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

. The Dover-Dunkirk ferry route takes two hours compared to Dover-Calais' 1 hour 30 minutes, is run by th r ee vessels and runs every two hours from Dunkirk. Another DFDS route connects Dunkirk to Rosslare Europort

Rosslare Europort ( ga, Europort Ros Láir) is a modern seaport located at Rosslare Harbour in County Wexford, Ireland, near the southeasternmost point of the island of Ireland. The port is the premier Irish port serving the European Contin ...

in the Republic of Ireland and carries truck freight as well as a limited number of private car passengers. The Dunkirk-Rosslare route take 24 hours and is run by the MF ''Regina Seaways''.

The Gare de Dunkerque railway station offers connections to Gare de Calais-Ville, Gare de Lille Flandres, Arras and Paris, and several regional destinations in France. The railway line from Dunkirk to De Panne and Adinkerke, Belgium, is closed and has been dismantled in places.

In September 2018, Dunkirk's public transit service introduced free public transport, thereby becoming the largest city in Europe to do so. Several weeks after the scheme had been introduced, the city's mayor, Patrice Vergriete, reported that there had been 50% increase in passenger numbers on some routes, and up to 85% on others. As part of the transition towards offering free bus services, the city's fleet was expanded from 100 to 140 buses, including new vehicles which run on natural gas. As of August 2019, approximately 5% of 2000 people surveyed had used the free bus service to completely replace their cars.

Sports

* USL Dunkerque, French football (soccer), football club, currently playing in Ligue 2. * The Four Days of Dunkirk (or ''Quatre Jours de Dunkerque'') is an important elite professional road bicycle racing event. * Stage 2 of the 2007 Tour de France departed from Dunkirk.Notable residents

*

* Jean Bart

Jean Bart (; ; 21 October 1650 – 27 April 1702) was a French Admiral, naval commander and privateer.

Early life

Jean Bart was born in Dunkirk, France, Dunkirk in 1650 to a seafaring family, the son of Jean-Cornil Bart (c. 1619-1668) who has b ...

, naval commander and privateer

* Eugène Chigot, 19th-century post impressionist painter

* Marvin Gakpa, footballer

* Louise Lavoye, 19th-century soprano

* Robert Malm, footballer

* Jean-Paul Rouve, actor

* François Rozenthal, ice hockey player

* Maurice Rozenthal, ice hockey player

* Djoumin Sangaré, footballer

* Tancrède Vallerey, writer

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Dunkirk is Twin towns and sister cities, twinned with: * Krefeld, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany since 15 June 1974 * Middlesbrough, England, United Kingdom since 12 April 1976 * Gaza City, Gaza, Palestine since 2 April 1996 * Rostock, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany since 9 April 2000 * Ramat HaSharon, Israel since 15 September 1997 * Qinhuangdao, Hebei, China since 25–26 September 2000Friendship links

Dunkirk has co-operation agreements with: * Borough of Dartford, Dartford, Kent, England, United Kingdom since March 1988 * Thanet District, Thanet, Kent, England, United Kingdom since 18 June 1993Climate

Dunkirk has an oceanic climate, with cool winters and warm summers. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Dunkirk has a marine west coast climate, abbreviated "Cfb" on climate maps. Summer high temperatures average around , being significantly influenced by the marine currents.See also

* Allied advance from Paris to the Rhine * Dunkirkers * French Flanders *French Flemish

French Flemish (French Flemish: , Standard Dutch: , french: flamand français) is a West Flemish dialect spoken in the north of contemporary France. Place names attest to Flemish having been spoken since the 8th century in the part of Fland ...

* Hortense Clémentine Tanvet

* Liberation of France

* Treaty of Dunkirk

References

External links

City council website

Tourist office website

{{Authority control Dunkirk, Communes of Nord (French department) France–United Kingdom border crossings Port cities and towns on the French Atlantic coast Port cities and towns of the North Sea Subprefectures in France Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom) Juxtaposed border controls Pirate dens and locations Vauban fortifications in France French Flanders