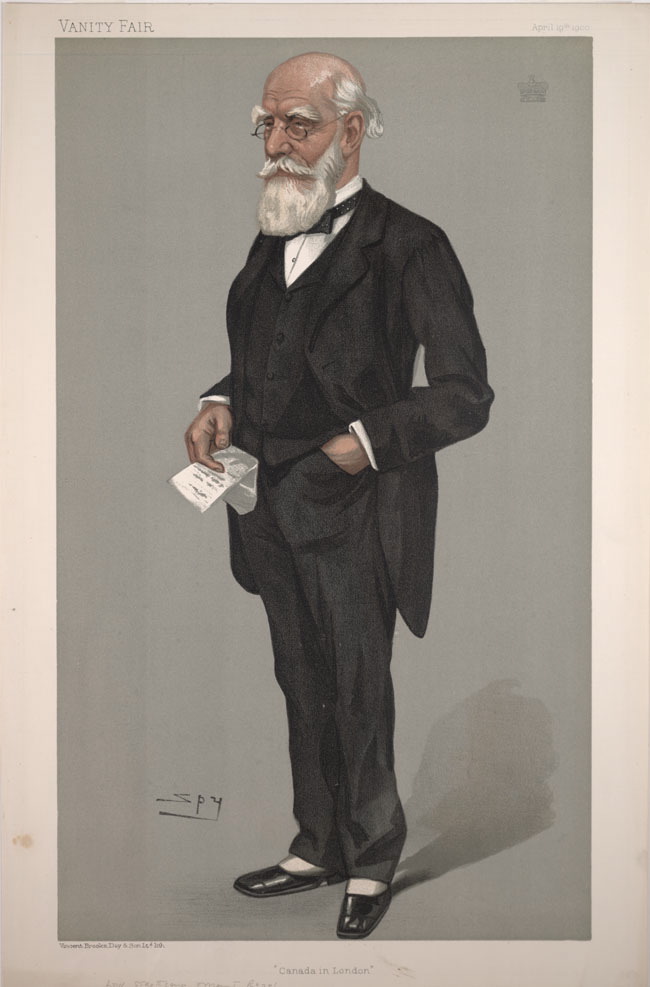

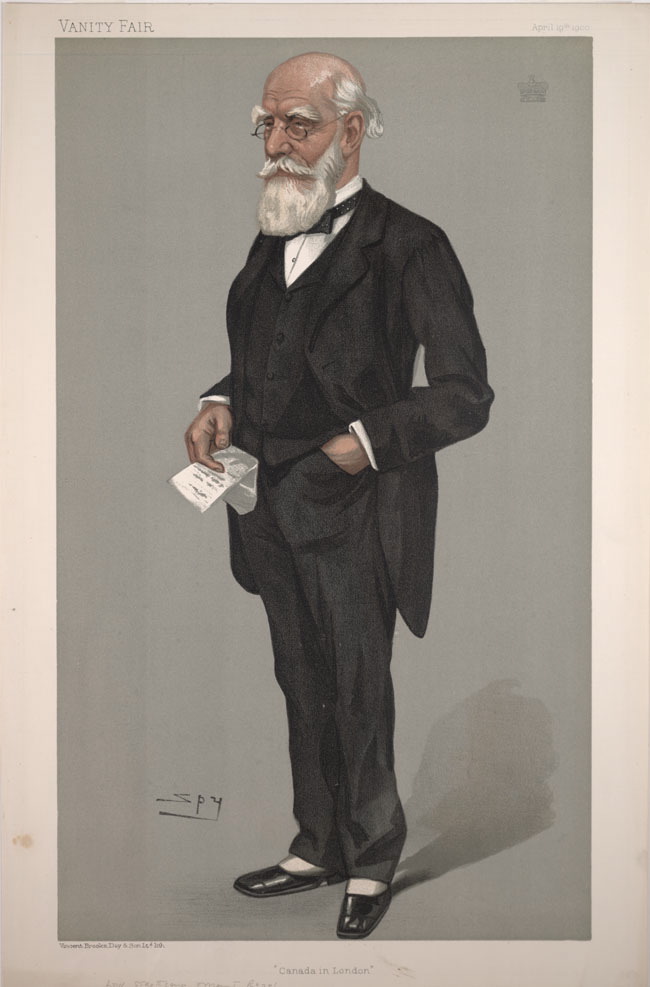

Donald Alexander Smith, 1st Baron Strathcona And Mount Royal on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Donald Alexander Smith, 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal, (6 August 182021 January 1914), known as Sir Donald A. Smith between May 1886 and August 1897, was a Scottish-born Canadian businessman who became one of the

Smith emigrated to

Smith emigrated to

In Manitoba's first general election, held on 27 December 1870, Smith was elected to the provincial legislature for the riding of Winnipeg and St. John, defeating long-time HBC nemesis John Christian Schultz by 71 votes to 63. Smith was a supporter of Archibald's consensus government, and opposed Schultz's ultra-loyalist Canadian Party; there was a riot among the Ontario soldiers stationed in

In Manitoba's first general election, held on 27 December 1870, Smith was elected to the provincial legislature for the riding of Winnipeg and St. John, defeating long-time HBC nemesis John Christian Schultz by 71 votes to 63. Smith was a supporter of Archibald's consensus government, and opposed Schultz's ultra-loyalist Canadian Party; there was a riot among the Ontario soldiers stationed in

In May 1879, Smith became a director in the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway Company, having control over 20% of its shares. He was subsequently a leading figure in the creation of the

In May 1879, Smith became a director in the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway Company, having control over 20% of its shares. He was subsequently a leading figure in the creation of the

In 1853, he married Isabella Sophia Hardisty (1825–1913), daughter of Richard Hardisty (1790–1865), Chief Trader of the

In 1853, he married Isabella Sophia Hardisty (1825–1913), daughter of Richard Hardisty (1790–1865), Chief Trader of the

Lord Strathcona is commemorated in Montreal by several McGill University buildings; he gave freely of his time to this institution, and a great quantity of his wealth. In Westmount, a street was named in his honour. In the greater Montreal West Island community, the Strathcona Desjardins Credit Union bears his name, with offices in downtown Montreal and in Kirkland. The credit union members were historically from the English-speaking hospitals of Montreal, but since then recent mergers also include Montreal area, English-speaking teachers.

The Strathcona family mansion in Montreal on Dorchester Street (now René Lévesque Boulevard) near Fort Street was torn down in 1941 to make way for an apartment building.

Strathcona Avenue, located in Westmount (a suburb on the island of Montreal) is named in his honour.

Strathcona is commemorated in Manitoba by the Rural Municipality of Strathcona and by three streets in Winnipeg: Donald Street and Smith Street in the downtown core, and Strathcona Street in the city's West End. In Alberta he is commemorated by the

Lord Strathcona is commemorated in Montreal by several McGill University buildings; he gave freely of his time to this institution, and a great quantity of his wealth. In Westmount, a street was named in his honour. In the greater Montreal West Island community, the Strathcona Desjardins Credit Union bears his name, with offices in downtown Montreal and in Kirkland. The credit union members were historically from the English-speaking hospitals of Montreal, but since then recent mergers also include Montreal area, English-speaking teachers.

The Strathcona family mansion in Montreal on Dorchester Street (now René Lévesque Boulevard) near Fort Street was torn down in 1941 to make way for an apartment building.

Strathcona Avenue, located in Westmount (a suburb on the island of Montreal) is named in his honour.

Strathcona is commemorated in Manitoba by the Rural Municipality of Strathcona and by three streets in Winnipeg: Donald Street and Smith Street in the downtown core, and Strathcona Street in the city's West End. In Alberta he is commemorated by the

File:Lord Strathcona's house on Dorchester Street, Montreal.jpg, Lord Strathcona's house in Montreal's

Sir Donald Alexander Smith, Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal fonds

- Library and Archives Canada *

Photograph: Sir Donald Smith, Lord Strathcona in 1895. McCord MuseumPhotograph: Sir Donald Smith, Lord Strathcona in 1908. McCord MuseumPhotograph: Mausoleum in the East Cemetery, Highgate Cemetery in which Donald Alexander Smith lies

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Strathcona And Mount Royal, Donald Smith, 1st Baron 1820 births 1914 deaths Nobility from Moray Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Canadian peers High commissioners of Canada to the United Kingdom Canadian Presbyterians Canadian philanthropists Canadian railway entrepreneurs Chancellors by university and college in Canada Chancellors of McGill University Chancellors of the University of Aberdeen Deputy lieutenants of Argyllshire Governors of the Hudson's Bay Company Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Independent Conservative MPs in the Canadian House of Commons, Smith Canadian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Canadian Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order 19th-century members of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba, Smith Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Manitoba, Smith Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Quebec, Smith Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Canadian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom 19th-century members of the Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories, Smith Scottish emigrants to pre-Confederation Quebec, Smith, Donald Burials at Highgate Cemetery, Smith, Donald Rectors of the University of Aberdeen Anglophone Quebec people Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12), Smith, Donald Alexander Bank of Montreal presidents People associated with the University of Birmingham 19th-century Canadian businesspeople Immigrants to Lower Canada BP people Peers of the United Kingdom created by Queen Victoria Lord Strathcona's Horse (Royal Canadians) 19th-century members of the House of Commons of Canada

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

's foremost builders and philanthropists. He became commissioner, governor and principal shareholder of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

. He was president of the Bank of Montreal

The Bank of Montreal (, ), abbreviated as BMO (pronounced ), is a Canadian multinational Investment banking, investment bank and financial services company.

The bank was founded in Montreal, Quebec, in 1817 as Montreal Bank, making it Canada ...

and with his first cousin, George Stephen (later Lord Mount Stephen

George Stephen, 1st Baron Mount Stephen, (5 June 1829 – 29 November 1921), known as Sir George Stephen, Bt, between 1886 and 1891, was a Canadian businessman. Originally from Scotland, he made his fame in Montreal and was the first Canadian t ...

), co-founded the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway () , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadian Pacific Kansas City, Canadian Pacific Ka ...

. He was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba

The Legislative Assembly of Manitoba () is the deliberative assembly of the Manitoba Legislature in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. Fifty-seven members are elected to this assembly at List of Manitoba genera ...

and afterwards represented Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

in the House of Commons of Canada

The House of Commons of Canada () is the lower house of the Parliament of Canada. Together with the Monarchy of Canada#Parliament (King-in-Parliament), Crown and the Senate of Canada, they comprise the Bicameralism, bicameral legislature of Ca ...

. He was Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom from 1896 to 1914. He was chairman of Burmah Oil

The Burmah Oil Company was a leading British oil company which was once a constituent of the FTSE 100 Index. In 1966, Castrol was acquired by Burmah, which was renamed Burmah-Castrol. BP Amoco purchased the company in 2000.

History

The c ...

and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC; ) was a British company founded in 1909 following the discovery of a large oil field in Masjed Soleiman, Persia (Iran). The British government purchased 51% of the company in 1914, gaining a controlling numbe ...

. He was chancellor of McGill University

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, ...

(1889–1914) and the University of Aberdeen

The University of Aberdeen (abbreviated ''Aberd.'' in List of post-nominal letters (United Kingdom), post-nominals; ) is a public university, public research university in Aberdeen, Scotland. It was founded in 1495 when William Elphinstone, Bis ...

.

King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria and ...

called him "Uncle Donald". His estate was valued at $5.5 million (equivalent to $ million in ). During his lifetime, and including the bequests left after his death, he gave away just over $7.5 million-plus a further £1 million (not including private gifts and allowances) to a huge variety of charitable causes across Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. He personally raised Strathcona's Horse

Lord Strathcona's Horse (Royal Canadians) (LdSH(RC)) is a regular armoured warfare, armoured regiment of the Canadian Army and is Canada’s only tank regiment. Currently based in Edmonton, Alberta, the regiment is part of 3rd Canadian Division' ...

, who saw their first action in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

. He funded the building of Leanchoil Hospital. He and his first cousin, Lord Mount Stephen, purchased the land and then each gave $1 million to the City of Montreal

Montreal is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest in Canada, and the ninth-largest in North America. It was founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", and is now named after Mount Royal, the triple-pea ...

to construct and maintain the Royal Victoria Hospital. He endowed the Lord Strathcona Medal and donated generously to McGill University

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, ...

, Aberdeen University

The University of Aberdeen (abbreviated ''Aberd.'' in post-nominals; ) is a public research university in Aberdeen, Scotland. It was founded in 1495 when William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen and Chancellor of Scotland, petitioned Pope Al ...

, the Victoria University of Manchester

The Victoria University of Manchester, usually referred to as simply the University of Manchester, was a university in Manchester, England. It was founded in 1851 as Owens College. In 1880, the college joined the federal Victoria University. A ...

, Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

, the Prince of Wales Hospital Fund and the Imperial Institute. At McGill, he started the ''Donalda Program'' for the purpose of providing higher education for Canadian women, building the Royal Victoria College on Sherbrooke Street for that purpose in 1886. He also built the Strathcona Medical Building at McGill and endowed its chairs

A chair is a type of seat, typically designed for one person and consisting of one or more legs, a flat or slightly angled seat and a back-rest. It may be made of wood, metal, or synthetic materials, and may be padded or Upholstery, upholstered ...

in pathology

Pathology is the study of disease. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in the context of modern medical treatme ...

and hygiene

Hygiene is a set of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

.

Early life

Born 6 August 1820, onForres

Forres (; ) is a town and former royal burgh in the north of Scotland on the County of Moray, Moray coast, approximately northeast of Inverness and west of Elgin, Moray, Elgin. Forres has been a winner of the Scotland in Bloom award on several ...

High Street, in Moray

Moray ( ; or ) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with a coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland. Its council is based in Elgin, the area' ...

, Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, he was the second son of Alexander Smith (1786–1841) and his wife Barbara Stuart, daughter of Donald Stuart (b.c.1740) of Leanchoil, Upper Strathspey, descended from Murdoch Stewart, 2nd Duke of Albany

Murdoch Stewart, Duke of Albany () (1362 – 25 May 1425) was a leading Scottish nobleman, the son of Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany, and the grandson of King Robert II of Scotland, who founded the Stewart dynasty. In 1389, he became Justiciar o ...

. His father, whose family had lived at Archiestown Cottage as crofters at Knockando, became a saddle

A saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals.

It is not know ...

r at Forres after trying his hand at farming and soldiering. Donald was also a first cousin of the successful and notably philanthropic Grant brothers of Manchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, who were reputedly immortalised as the "Cheeryble Brothers" in Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

' book, Nicholas Nickleby

''Nicholas Nickleby'', or ''The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby'', is the third novel by English author Charles Dickens, originally published as a serial from 1838 to 1839. The character of Nickleby is a young man who must support his ...

. Donald's mother was the sister of the Canadian explorer John Stuart, partner of the North West Company

The North West Company was a Fur trade in Canada, Canadian fur trading business headquartered in Montreal from 1779 to 1821. It competed with increasing success against the Hudson's Bay Company in the regions that later became Western Canada a ...

who rose to become Chief Factor of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

.

Smith was educated at Anderson's Free School and on leaving at age sixteen he was apprenticed to become a lawyer in the offices of Robert Watson, Town Clerk

A clerk (pronounced "clark" /klɑːk/ in British and Australian English) is a senior official of many municipal governments in the English-speaking world. In some communities, including most in the United States, the position is elected, but in ma ...

of Forres. By the age of eighteen, Smith chose another career path: offered entry into mercantile life at Manchester, and a career in the Indian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British Raj, British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 3 ...

, his choice was to pattern himself on his uncle John Stuart (who had by then returned to live near Forres) who offered him a junior clerkship in the service of the Hudson's Bay Company. Smith chose to follow his uncle's career and sailed to Montreal that year.

Hudson's Bay Company

Smith emigrated to

Smith emigrated to Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada () was a British colonization of the Americas, British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence established in 1791 and abolished in 1841. It covered the southern portion o ...

in 1838 to work for the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

(HBC), becoming a clerk for the organization in 1842. He was given administrative control over the seigneury

A seigneur () or lord is an originally feudal system, feudal title in Ancien Régime, France before the French Revolution, Revolution, in New France and British North America until 1854, and in the Channel Islands to this day. The seigneur owne ...

of Mingan (in modern Labrador

Labrador () is a geographic and cultural region within the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is the primarily continental portion of the province and constitutes 71% of the province's area but is home to only 6% of its populatio ...

) in late 1843, where his innovative methods met with the disapproval of HBC governor Sir George Simpson. The Mingan post burned down in 1846, and Smith left for Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

the following year. He returned in 1848, and remained in Labrador until the 1860s, administering the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

and salmon

Salmon (; : salmon) are any of several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the genera ''Salmo'' and ''Oncorhynchus'' of the family (biology), family Salmonidae, native ...

fishing within the region.

In 1862, Smith was promoted as the company's Chief Factor in charge of the Labrador district. He travelled to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

in 1865, and made a favourable impression on the HBC's directors. In 1868, he was promoted to Commissioner of the Montreal department, managing the HBC's eastern operations. That same year, Smith joined with George Stephen, Richard Bladworth Angus, and Andrew Paton to establish the textile manufactory, Paton Manufacturing Company, in Sherbrooke

Sherbrooke ( , ) is a city in southern Quebec, Canada. It is at the confluence of the Saint-François River, Saint-François and Magog River, Magog rivers in the heart of the Estrie administrative region. Sherbrooke is also the name of a territ ...

.

In 1869, the government of John A. Macdonald held the HBC accountable for the disturbances reported in the Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assiniboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hudson's Bay ...

, which was part of the proposed purchase of the original part of Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (), or Prince Rupert's Land (), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin. The right to "sole trade and commerce" over Rupert's Land was granted to Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), based a ...

from the HBC. The person in charge of HBC's nominal head office in Montreal was Smith, and he was asked by the Governor-General to investigate and write a Royal Commission

A royal commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue in some monarchies. They have been held in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia. In republics an equi ...

report. Smith travelled to (present-day) Manitoba

Manitoba is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population ...

, and negotiated at Fort Garry with Louis Riel

Louis Riel (; ; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis in Canada, Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of ...

, who had been voted the leader of the resistance. Smith's offers, including land recognition for the Métis

The Métis ( , , , ) are a mixed-race Indigenous people whose historical homelands include Canada's three Prairie Provinces extending into parts of Ontario, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the northwest United States. They ha ...

, led to Riel calling a Council of 40 representatives, drawn half-and-half from the Metis and the HBC settlers, for formal negotiations. Smith returned to Ottawa

Ottawa is the capital city of Canada. It is located in the southern Ontario, southern portion of the province of Ontario, at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the cor ...

in early 1870, and communicated the Royal Commission on the ''North-West Territories'', which effectively made his name in Canada and London. Smith succeeded in gaining clemency for some prisoners within the region; he was not, however, able to prevent the execution of Thomas Scott by Riel's provisional government. He was appointed that year to the office of President of the HBC's Council of the Northern Department (effectively becoming administrator of the Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories is a federal Provinces and territories of Canada, territory of Canada. At a land area of approximately and a 2021 census population of 41,070, it is the second-largest and the most populous of Provinces and territorie ...

, including Manitoba).

Smith accompanied Col. Garnet Wolseley's military mission to Red River later in the year; following the end of the resistance, Wolseley appointed Smith as the Acting Governor of Assiniboia

Assiniboia District refers to two historical districts of Canada's Northwest Territories. The name is taken from the Assiniboine First Nation.

Historical usage

''For more information on the history of the provisional districts, see also Distric ...

pending Lieutenant Governor Adams George Archibald

Sir Adams George Archibald (May 3, 1814 – December 14, 1892) was a Canadian lawyer and politician, and a Father of Confederation. He was based in Nova Scotia for most of his career, though he also served as first Lieutenant Governor of Man ...

's arrival in the province. Smith stayed in the region after 1870 and was responsible for negotiating the transfer of HBC land to the federal government (as well as coordinating the transfer of several specific land claims in the region). Archibald appointed Smith to his Executive Council on 20 October 1870, although this decision was subsequently overturned by the Canadian government, which ruled that Archibald had overstepped his legal authority.

Political career

In Manitoba's first general election, held on 27 December 1870, Smith was elected to the provincial legislature for the riding of Winnipeg and St. John, defeating long-time HBC nemesis John Christian Schultz by 71 votes to 63. Smith was a supporter of Archibald's consensus government, and opposed Schultz's ultra-loyalist Canadian Party; there was a riot among the Ontario soldiers stationed in

In Manitoba's first general election, held on 27 December 1870, Smith was elected to the provincial legislature for the riding of Winnipeg and St. John, defeating long-time HBC nemesis John Christian Schultz by 71 votes to 63. Smith was a supporter of Archibald's consensus government, and opposed Schultz's ultra-loyalist Canadian Party; there was a riot among the Ontario soldiers stationed in Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Manitoba. It is centred on the confluence of the Red River of the North, Red and Assiniboine River, Assiniboine rivers. , Winnipeg h ...

following the announcement of Smith's victory.

Politicians were allowed to serve in both the provincial and federal parliaments in this period of Manitoba history, and Smith was elected to the House of Commons of Canada

The House of Commons of Canada () is the lower house of the Parliament of Canada. Together with the Monarchy of Canada#Parliament (King-in-Parliament), Crown and the Senate of Canada, they comprise the Bicameralism, bicameral legislature of Ca ...

for the newly formed riding of Selkirk in early 1871. He sat as an Independent Conservative, and initially supported the government of Sir John A. Macdonald. Easily re-elected in 1872, Smith was a strong defender of HBC interests in the House of Commons, and also spoke for issues concerning Manitoba and the Northwest. He helped create the Bank of Manitoba and the Manitoba Insurance Company during this period, assisted by banker Sir Hugh Allan.

In 1872 Smith was appointed to the first group of members of the Temporary North-West Council

The Temporary North-West Council, more formally known as the Council of the North-West Territories and by its short name as the North-West Council, lasted from the creation of North-West Territories, Canada, in 1870 until it was dissolved in 1876 ...

the first governing assembly of the North-West Territories. Smith was one of the few people who served on two provincial/territorial legislatures and the federal parliament at the same time.

Smith broke with Macdonald in 1873, after the Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

had delayed reimbursement for Smith's earlier expenses in Red River. Smith voted to censure the government in a motion over the Pacific Scandal

The Pacific Scandal was a political scandal in Canada involving large sums of money paid by private interests to the Conservative Party to cover election expenses in the 1872 Canadian federal election in order to influence the bidding for a natio ...

and was thereby partly responsible for the government's defeat. Smith remained an Independent Conservative, but his relations with the official Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

representatives were often strained in later years.

Manitoba abolished the "dual mandate" in 1873, and Smith resigned from the provincial legislature in early 1874 (the first person to do so). In the Canadian general election of 1874, Smith defeated Liberal candidate Andrew G. B. Bannatyne by 329 votes to 225. The '' Manitoba Free Press'', at the time, suggested that Smith had encouraged Bannatyne's candidacy to prevent more serious opposition from emerging.

In 1873, the HBC separated its fur trade and land sales operations, putting Smith in charge of the latter. Smith had developed an interest in railway expansion through his work with the HBC, and in 1875 was among the incorporators of the Manitoba Western Railway. He was also a partner in the Red River Transportation Company

Red is the color at the long wavelength end of the visible spectrum of light, next to orange and opposite violet. It has a dominant wavelength of approximately 625–750 nanometres. It is a primary color in the RGB color model and a second ...

, which gained control over the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad in March 1878. His business ventures increasingly dominated his labours, and he formally resigned as land commissioner in early 1879, though he remained a leading figure in the HBC's operations for another 30 years.

Smith faced a serious electoral challenge from former Manitoba Lieutenant Governor Alexander Morris in the general election of 1878. Aided on this occasion by the ''Manitoba Free Press'', Smith defeated Morris by 555 votes to 546; local Conservative organizers protested the result, and it was overturned two years later. On 10 September 1880, Smith was defeated by former Winnipeg Mayor Thomas Scott, 735 votes to 577.

Corporate leader

In May 1879, Smith became a director in the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway Company, having control over 20% of its shares. He was subsequently a leading figure in the creation of the

In May 1879, Smith became a director in the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway Company, having control over 20% of its shares. He was subsequently a leading figure in the creation of the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway () , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadian Pacific Kansas City, Canadian Pacific Ka ...

, although he was not appointed as a director of the organization until 1883 because of his lingering animosity with Sir John A. Macdonald (who had again become prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

in 1878). During his tenure on the board, Smith had the honour of driving the last spike at Craigellachie, British Columbia

Craigellachie (pronounced ) is a locality in British Columbia, located several kilometres to the west of the Eagle Pass (British Columbia), Eagle Pass summit between Sicamous and Revelstoke, British Columbia, Revelstoke. Craigellachie is the si ...

to complete the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway () , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadian Pacific Kansas City, Canadian Pacific Ka ...

rail line. Smith remained on the board of directors for several years, although he was by-passed for the company's presidency in 1888, in favour of William Cornelius Van Horne

Sir William Cornelius Van Horne, (February 3, 1843September 11, 1915) was an American businessman, industrialist and railroad magnate who spent most of his career in Canada. He is famous for overseeing the construction of the first Canadian Tran ...

.

Smith became extremely wealthy through his investments, and he was involved in a myriad of Canadian and American corporations in the latter part of the 19th century. He was appointed to the board of the Bank of Montreal

The Bank of Montreal (, ), abbreviated as BMO (pronounced ), is a Canadian multinational Investment banking, investment bank and financial services company.

The bank was founded in Montreal, Quebec, in 1817 as Montreal Bank, making it Canada ...

in 1872, became its vice-president in 1882, and was promoted to the Presidency in 1887. His leadership in real estate transactions caused Smith to become a financier, and he was thus involved in (or founded) over 80 trust structures, including the Royal Trust and Montreal Trust

The Montreal Trust Company is a Canadian trust company that has existed since 1889. In 1967, Paul Desmarais acquired minority control of the company. The following year, he transferred his shares in the company to the Power Corporation of Canada, ...

. He retained a significant interest in the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

throughout his life and became in 1889 Governor of the company that had made his name.

Smith was also involved in the newspaper industry in his later years. His attempt to take over the ''Toronto Globe

''The Globe'' was a Canadian newspaper in Toronto, Ontario, founded in 1844 by George Brown as a Reform voice. It merged with ''The Mail and Empire'' in 1936 to form ''The Globe and Mail''.

History

''The Globe'' is pre-dated by a title of the s ...

'' in 1882 was unsuccessful, though he took effective control of the '' Manitoba Free Press'' from William Fisher Luxton in 1893. In 1889, he was the principal shareholder of the Hudson's Bay Company and was elected as its 26th governor, holding this position until his death in 1914.

Later political career

Smith was re-elected to the Canadian House of Commons in1887

Events January

* January 11 – Louis Pasteur's anti-rabies treatment is defended in the Académie Nationale de Médecine, by Dr. Joseph Grancher.

* January 20

** The United States Senate allows the United States Navy to lease Pearl Har ...

, in the Quebec

Quebec is Canada's List of Canadian provinces and territories by area, largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, ...

riding of Montreal West, and once again sat as an "Independent Conservative". In the same year he received an honorary Doctor of Laws from St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, formally the College of St John the Evangelist in the University of Cambridge, is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge, founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch L ...

. He was re-elected in the election of 1891, defeating his only opponent, James Cochrane, 4586 votes to 880. Smith remained interested in Manitoba politics, and attempted (without success) to broker a compromise between Thomas Greenway

Thomas Greenway (25 March 1838 – 30 October 1908) was a Canadian politician, merchant and farmer. He served as the seventh premier of Manitoba from 1888 to 1900. A Liberal, his ministry formally ended Manitoba's non-partisan government, al ...

and the federal government during the Manitoba school crisis of the 1890s.

High Commissioner

Prime Minister Sir Mackenzie Bowell wanted Smith to succeed him in 1896, but Smith refused. The position of Prime Minister instead went to Sir Charles Tupper, who appointed Smith as High Commissioner to the United Kingdom on 24 April 1896. Sir Wilfrid Laurier retained Smith as High Commissioner following the Liberal election victory of 1896, although his powers were somewhat undercut. He was created Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal, of Glencoe in the County of Argyll and ofMount Royal

Mount Royal (, ) is a mountain in the city of Montreal, immediately west of Downtown Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The city's name is derived from the mountain's name.

The mountain is part of the Monteregian Hills situated between the Laurentian M ...

in the Province of Quebec

Quebec is Canada's largest province by area. Located in Central Canada, the province shares borders with the provinces of Ontario to the west, Newfoundland and Labrador to the northeast, New Brunswick to the southeast and a coastal border ...

and Dominion of Canada

While a variety of theories have been postulated for the name of Canada, its origin is now accepted as coming from the St. Lawrence Iroquoian word , meaning 'village' or 'settlement'. In 1535, indigenous inhabitants of the present-day Quebec C ...

, in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

The Peerage of the United Kingdom is one of the five peerages in the United Kingdom. It comprises most peerages created in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland after the Acts of Union in 1801, when it replaced the Peerage of Great B ...

, on 23 August 1897, as part of the 1897 Diamond Jubilee Honours

The Diamond Jubilee Honours for the British Empire were announced on 22 June 1897 to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria on 20 June 1897.

The recipients of honours are displayed here as they were styled before their new honour, and ar ...

. He had already been made KCMG on 29 May 1886, promoted to GCMG on 20 May 1896, and was further made GCVO in 1908. He cooperated with Manitoba Liberal Clifford Sifton in opening the Canadian prairies to eastern-European immigration. He raised Strathcona's Horse

Lord Strathcona's Horse (Royal Canadians) (LdSH(RC)) is a regular armoured warfare, armoured regiment of the Canadian Army and is Canada’s only tank regiment. Currently based in Edmonton, Alberta, the regiment is part of 3rd Canadian Division' ...

, a private unit of Canadian soldiers, during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, and became one of the leading supporters of British imperialism within London. After the end of the war, he was appointed among the members of a Royal Commission set up to investigate the conduct of the Second Boer War (the Elgin Commission 1902–1903). He was involved in the creation of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company

The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC; ) was a British company founded in 1909 following the discovery of a large oil field in Masjed Soleiman, Persia (Iran). The British government purchased 51% of the company in 1914, gaining a controlling numbe ...

, of which he became the chairman in 1909. Lord Strathcona subsequently used his influence to make the company a major supplier of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

.

He was granted a second creation of the Barony, with a Special Remainder in favour of his daughter Margaret Charlotte Howard, as Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal, of Mount Royal in the Province of Quebec and Dominion of Canada, and of Glencoe in the County of Argyll, on 26 June 1900.

He was Lord Rector of the University of Aberdeen (1899–1902), and he received the Freedom of the City of Aberdeen in a ceremony on 9 April 1902.

On 12 February 1902, he was appointed an Honorary Colonel of the 8th (Volunteer) Battalion, the King's (Liverpool Regiment), and the same month he received the honorary degree

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

of Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) is a doctoral degree in legal studies. The abbreviation LL.D. stands for ''Legum Doctor'', with the double “L” in the abbreviation referring to the early practice in the University of Cambridge to teach both canon law ...

(LL.D.) from the Victoria University of Manchester

The Victoria University of Manchester, usually referred to as simply the University of Manchester, was a university in Manchester, England. It was founded in 1851 as Owens College. In 1880, the college joined the federal Victoria University. A ...

, in connection with the 50th jubilee of the establishment of the university. He received the honorary degree Doctor of Civil Law

Doctor of Civil Law (DCL; ) is a degree offered by some universities, such as the University of Oxford, instead of the more common Doctor of Laws (LLD) degrees.

At Oxford, the degree is a higher doctorate usually awarded on the basis of except ...

(DCL) from the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

in October 1902, in connection with the tercentenary of the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford. Founded in 1602 by Sir Thomas Bodley, it is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second-largest library in ...

.

He was sworn in as a Member of the Imperial Privy Council in 1904. He received the Freedom of the City of Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

on 13 July 1911.

Philanthropy

Strathcona was a leading philanthropist in his later years, donating large sums of money to various organizations in Britain, Canada and elsewhere. His largest donations were made with George Stephen, donating the money to build the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal that opened its doors in 1893. Strathcona also made a major donation toMcGill University

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, ...

in Montreal, where he helped establish a school for women in 1884 (Royal Victoria College). He was named Chancellor of McGill in 1888, and he held the post until his death. He also bequeathed funds to the Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School was founded in 1847 as a school of Yale University, Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, for instruction in science and engineering. Originally named the Yale Scientific School, it was renamed in 1861 in honor of Jos ...

for a science and engineering building and to support two professorships in engineering. He was awarded an honorary degree from Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

in 1892. He contributed donations to the new University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University) is a Public university, public research university in Birmingham, England. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingham (founded in 1825 as ...

following representations by Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal Party (UK), Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually was a leading New Imperialism, imperial ...

.

In 1910, Strathcona deposited in trust with the Dominion Government the sum of $500,000, bearing an annual interest of 4%, to develop citizenship and patriotism, for example in the Royal Canadian Army Cadets

The Royal Canadian Army Cadets (RCAC; ) is a national Canadian youth program sponsored by the Canadian Armed Forces and the civilian Army Cadet League of Canada. Under the authority of the National Defence Act, the program is administered by th ...

movement, through physical training, rifle shooting, and military drill. A ''Syllabus of Physical Exercises for Schools'' was published by the Trust in 1911. He is remembered today by the Cadets with the Lord Strathcona Medal.

Death

Lord Strathcona died in 1914 inLondon

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

and was buried at Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in North London, England, designed by architect Stephen Geary. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East sides. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for so ...

. His imposing red granite vault is the first vault after entering the Eastern Cemetery. His seventy-five-year tenure with the Hudson's Bay Company remains a record.

He lived in Montreal's Golden Square Mile

The Golden Square Mile (, ), also known as the Square Mile, is the nostalgic name given to an urban neighbourhood developed principally between 1850 and 1930 at the foot of Mount Royal, in the west-central section of downtown Montreal in Quebec, Ca ...

. In 1895, he purchased an estate in Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, building and living at Glencoe House. In 1905, he purchased the Island of Colonsay including Colonsay House (where his descendants still live) and the Island of Oronsay, both on the Hebridean coast of Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

. He kept a house in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

and after his appointment as Canadian High Commissioner leased Knebworth House

Knebworth House is an English country house in the parish of Knebworth in Hertfordshire, England. It is a Listed building#Categories of listed building, Grade II* listed building. Its gardens are also listed Register of Historic Parks and Gar ...

from 1899 until his death. He was given a full state funeral at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

, where a memorial stands to his memory, and would have been entombed there but he preferred to rest next to his wife, who pre-deceased him by several months, in Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in North London, England, designed by architect Stephen Geary. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East sides. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for so ...

.

His obituary in '' The Times of London'' read in part,

Family

In 1853, he married Isabella Sophia Hardisty (1825–1913), daughter of Richard Hardisty (1790–1865), Chief Trader of the

In 1853, he married Isabella Sophia Hardisty (1825–1913), daughter of Richard Hardisty (1790–1865), Chief Trader of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

, and Margaret Sutherland (1802–1876), daughter of the Rev. John Sutherland, a native of Caithness

Caithness (; ; ) is a Shires of Scotland, historic county, registration county and Lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area of Scotland.

There are two towns, being Wick, Caithness, Wick, which was the county town, and Thurso. The count ...

who lived at Lachine, Quebec

Lachine () is a borough (''arrondissement'') within the city of Montreal on the Island of Montreal in southwestern Quebec, Canada.

It was founded as a trading post in 1669. Developing into a parish and then an autonomous city, it was Montreal m ...

. Lady Strathcona's father was a native of London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, and her mother was of Indian and Scottish parentage. Her brother was the Hon. Richard Charles Hardisty. She was presented to King Edward and Queen Alexandra, 13 March 1903, and with her daughter donated $100,000 to McGill University

McGill University (French: Université McGill) is an English-language public research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill University, Vol. I. For the Advancement of Learning, ...

in Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

to erect a new wing to its Medical Building. The couple lived at 53 Cadogan Square, London; Knebworth House

Knebworth House is an English country house in the parish of Knebworth in Hertfordshire, England. It is a Listed building#Categories of listed building, Grade II* listed building. Its gardens are also listed Register of Historic Parks and Gar ...

; Debden Hall; Glencoe House, Scotland; Colonsay House, Scotland and 1157 Dorchester Street, in Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

's Golden Square Mile

The Golden Square Mile (, ), also known as the Square Mile, is the nostalgic name given to an urban neighbourhood developed principally between 1850 and 1930 at the foot of Mount Royal, in the west-central section of downtown Montreal in Quebec, Ca ...

.

Lord and Lady Strathcona were the parents of one child, the Hon. Margaret Charlotte Smith. In accordance with the special remainder to the 1900 barony, she succeeded her father as Lady Strathcona in 1914. In 1888, she married Robert Jared Bliss Howard OBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding valuable service in a wide range of useful activities. It comprises five classes of awards across both civil and military divisions, the most senior two o ...

FRCS

Fellowship of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons (FRCS) is a professional certification, professional qualification to practise as a senior surgeon in Republic of Ireland, Ireland or the United Kingdom. It is bestowed on an wikt:intercollegiate, ...

(1859–1921), son of Robert Palmer Howard (1823–1889), Dean of Medicine at McGill University.

Robert Howard and Lady Strathcona had the following children:

* The Hon. Frances Margaret Palmer Howard (born 13 February 1889, died 5 October 1958)

* The Rt Hon. Donald Sterling Palmer Howard, 3rd Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal (born 14 June 1891, died 22 February 1959)

* The Hon. Robert Henry Palmer Howard (born 1893, killed in action

Killed in action (KIA) is a casualty classification generally used by militaries to describe the deaths of their personnel at the hands of enemy or hostile forces at the moment of action. The United States Department of Defense, for example, ...

8 May 1915)

* The Hon. Edith Mary Palmer Howard (born 7 April 1895, died 1979), married John Brooke Molesworth Parnell, 6th Baron Congleton on 6 April 1918

* The Hon. Sir Arthur Jared Palmer Howard, KBE

KBE may refer to:

* Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, post-nominal letters

* Knowledge-based engineering

Knowledge-based engineering (KBE) is the application of knowledge-based systems technology to the domain o ...

CVO (born 30 May 1896, died 26 April 1971)

His Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

home was located in the Golden Square Mile

The Golden Square Mile (, ), also known as the Square Mile, is the nostalgic name given to an urban neighbourhood developed principally between 1850 and 1930 at the foot of Mount Royal, in the west-central section of downtown Montreal in Quebec, Ca ...

. In 1905, he bought the island of Colonsay

Colonsay (; ; ) is an island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, located north of Islay and south of Isle of Mull, Mull. The ancestral home of Clan Macfie and the Colonsay branch of Clan MacNeil, it is in the council area of Argyll and Bute and ...

in the Inner Hebrides

The Inner Hebrides ( ; ) is an archipelago off the west coast of mainland Scotland, to the south east of the Outer Hebrides. Together these two island chains form the Hebrides, which experience a mild oceanic climate. The Inner Hebrides compri ...

, which remains in the hands of his successors today.

Legacy

Lord Strathcona is commemorated in Montreal by several McGill University buildings; he gave freely of his time to this institution, and a great quantity of his wealth. In Westmount, a street was named in his honour. In the greater Montreal West Island community, the Strathcona Desjardins Credit Union bears his name, with offices in downtown Montreal and in Kirkland. The credit union members were historically from the English-speaking hospitals of Montreal, but since then recent mergers also include Montreal area, English-speaking teachers.

The Strathcona family mansion in Montreal on Dorchester Street (now René Lévesque Boulevard) near Fort Street was torn down in 1941 to make way for an apartment building.

Strathcona Avenue, located in Westmount (a suburb on the island of Montreal) is named in his honour.

Strathcona is commemorated in Manitoba by the Rural Municipality of Strathcona and by three streets in Winnipeg: Donald Street and Smith Street in the downtown core, and Strathcona Street in the city's West End. In Alberta he is commemorated by the

Lord Strathcona is commemorated in Montreal by several McGill University buildings; he gave freely of his time to this institution, and a great quantity of his wealth. In Westmount, a street was named in his honour. In the greater Montreal West Island community, the Strathcona Desjardins Credit Union bears his name, with offices in downtown Montreal and in Kirkland. The credit union members were historically from the English-speaking hospitals of Montreal, but since then recent mergers also include Montreal area, English-speaking teachers.

The Strathcona family mansion in Montreal on Dorchester Street (now René Lévesque Boulevard) near Fort Street was torn down in 1941 to make way for an apartment building.

Strathcona Avenue, located in Westmount (a suburb on the island of Montreal) is named in his honour.

Strathcona is commemorated in Manitoba by the Rural Municipality of Strathcona and by three streets in Winnipeg: Donald Street and Smith Street in the downtown core, and Strathcona Street in the city's West End. In Alberta he is commemorated by the Calgary

Calgary () is a major city in the Canadian province of Alberta. As of 2021, the city proper had a population of 1,306,784 and a metropolitan population of 1,481,806 making it the third-largest city and fifth-largest metropolitan area in C ...

neighbourhood of Strathcona Park by the Edmonton neighbourhood of Strathcona, and by the municipality of Strathcona County

Strathcona County is a Specialized municipalities of Alberta, specialized municipality in the Edmonton Metropolitan Region within Alberta, Canada between Edmonton and Elk Island National Park. It forms part of Division No. 11, Alberta, Census Di ...

. In British Columbia, the Vancouver neighbourhood of Strathcona takes its name from Lord Strathcona School built in 1891, and Mount Sir Donald in Glacier National Park is named after him. There are oil portraits of Lord Strathcona by many artists, but the Swiss-born American artist Adolfo Müller-Ury

Adolfo Müller-Ury, Order of St. Gregory the Great, KSG (March 29, 1862 – July 6, 1947) was a Swiss-born American portrait painter and Impressionism, impressionistic painter of roses and still life.

Early life and education

Müller was b ...

seems to have made a number of head and shoulder portraits of him from 1898 (examples may be found at the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad offices and in the Hudson's Bay Company his has a repainted background, and the artist also presented his 1899 bust-length charcoal and crayon drawing of Strathcona to McGill University in Montreal in 1916.

The Town of Fort Smith in the Northwest Territories is named after Donald Smith. There is a stained glass

Stained glass refers to coloured glass as a material or art and architectural works created from it. Although it is traditionally made in flat panels and used as windows, the creations of modern stained glass artists also include three-dimensio ...

window memorializing him in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. His coat of arms appears over the main entrance of Marischal College

Marischal College ( ) is a large granite building on Broad Street in the centre of Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, and since 2011 has been the headquarters of Aberdeen City Council. The building was constructed for and is on long-term lease fr ...

in Aberdeen. Strathcona Park, which was erected by the city of Ottawa in 1907, is dedicated to him. The Town of Transcona

Transcona is a ward and suburb of Winnipeg, Manitoba, located about east of the downtown area.

Until 1972, it was a separate municipality, having been incorporated first as the Town of Transcona on 6 April 1912 and then as the City of Transc ...

, Manitoba, incorporated in 1912 as a community to support the new railway shops of the Grand Trunk Pacific and National Transcontinental railways, takes half its name from Lord Strathcona, and the other half from the word ''transcontinental''.

Strathcona was inducted into the Canadian Curling Hall of Fame The Canadian Curling Hall of Fame was established with its first inductees in 1973. It is operated by Curling Canada, the governing body for curling in Canada, in Orleans, Ontario.

The Hall of Fame selection committee meets annually to choose indu ...

in 1973.

Ships named for Lord Strathcona

At least three ships were named for Lord Strathcona during his lifetime. These were: * ''Strathcona'', a 598-ton, 142-foot wooden sidewheel paddle steamer, was built in 1898 by J. Macfarlane atNew Westminster, British Columbia

New Westminster (colloquially known as New West) is a city in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia, Canada, and a member municipality of the Metro Vancouver Regional District. It was founded by Major-General Richard Moody as the capita ...

for the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

. The vessel was operated on the Pacific Northwest coast and in 1898-99 carried elements of the Yukon Field Force. In 1902 ''Strathcona'' was sold to S.J.V. Spratt, later passing into the hands of the Sidney & Nanaimo Transportation Company. On 17 November 1909, the vessel was wrecked on a snag near Pages Landing on the Fraser River. In 1910 ''Strathcona'' was refloated and towed to New Westminster, where the engines and boilers were removed and the hull abandoned.

* ''Strathcona'', a 1,881-ton, 253-foot steel canal-sized Great Lakes freighter, was built in 1900 by the Caledon Shipbuilding Company in Dundee, Scotland

Dundee (; ; or , ) is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, fourth-largest city in Scotland. The mid-year population estimate for the locality was . It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firt ...

. This steamer was converted from a bulk carrier to a package freighter in 1911 by the Collingwood Shipbuilding Company at Collingwood, Ontario

Collingwood is a town in Simcoe County, Ontario, Canada. It is situated on Nottawasaga Bay at the southern point of Georgian Bay. Collingwood is well known as a tourist destination, for its skiing in the winter, and limestone caves along the Nia ...

. ''Strathcona'' sailed for Inland Lines, Ltd., of Hamilton, Ontario

Hamilton is a port city in the Canadian Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Ontario. Hamilton has a 2021 Canadian census, population of 569,353 (2021), and its Census Metropolitan Area, census metropolitan area, which encompasses ...

until 1913, whereupon it passed into the hands of Canada Steamship Lines

Canada Steamship Lines (CSL) is a shipping company with headquarters in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The business has been operating for well over a century and a half.

Beginnings

CSL had humble beginnings in Canada East in 1845, operating river ...

when that fleet was established. In 1915 ''Strathcona'' was requisitioned for ocean service during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. While bound from the Tyne to Marseilles, France, ''Strathcona'' was sunk by a scuttling charge from SM ''U-78'' on 13 April 1917 when some 145 miles west-northwest of North Ronaldsay

North Ronaldsay (, also , ) is the northernmost island in the Orkney archipelago of Scotland. With an area of , it is the fourteenth-largest.Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 334 It is mentioned in the ''Orkneyinga saga''; in modern times it is known for ...

, Orkney Islands

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland ...

.

* ''Lord Strathcona'', a 495-ton, 160-foot steel salvage tug, was built in 1902 by J.P. Renoldson & Sons, Ltd., at South Shields, England. Owned by George T. Davie & Sons of Lauzon, Quebec, this tug arrived on its delivery voyage on 4 May 1902. ''Lord Strathcona'' was sold in 1912 to the Quebec Salvage & Wrecking Company, Ltd., a Canadian Pacific

The Canadian Pacific Railway () , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadian Pacific Kansas City, Canadian Pacific Ka ...

subsidiary, and remained in service through the end of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.Brookes, p. 56. Ownership passed to Foundation Maritime in 1944, and ''Lord Strathcona'' was scrapped in 1947.

A fourth ship, ''Lord Strathcona'', was a 7,335-ton, 455-foot ocean steamer built in 1915 by W. Doxford & Sons Ltd. at Sunderland, England. Owned by the Dominion Line

The Dominion Line was a trans-atlantic passenger line founded in 1870 as the ''Liverpool & Mississippi Steamship Co.'', with the official name being changed in 1872 to the ''Mississippi & Dominion Steamship Co Ltd.'' The firm was amalgamated in ...

, ''Lord Strathcona'' was bound from Wabana, Newfoundland to Sydney, Nova Scotia

Sydney is a former city and urban community on the east coast of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada within the Cape Breton Regional Municipality. Sydney was founded in 1785 by the British, was incorporated as a city in 1904, and dissolv ...

with iron ore when the vessel was torpedoed and sunk by U-513

German submarine ''U-513'' was a type IXC U-boat built for service in Nazi Germany's ''Kriegsmarine'' during World War II.

She was Keel laying, laid down on 26 April 1941 by the naval construction firm Deutsche Werft AG in Hamburg as yard number ...

on 5 September 1942. ''Lord Strathconas crew of 44, including Captain Charles Stewart, were rescued.

Gallery

Golden Square Mile

The Golden Square Mile (, ), also known as the Square Mile, is the nostalgic name given to an urban neighbourhood developed principally between 1850 and 1930 at the foot of Mount Royal, in the west-central section of downtown Montreal in Quebec, Ca ...

, built in 1879

File:Glencoe House, 1905.jpg, Glencoe House, Scotland in 1905, built by Lord Strathcona in 1895

File:Colonsay House.JPG, Colonsay

Colonsay (; ; ) is an island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland, located north of Islay and south of Isle of Mull, Mull. The ancestral home of Clan Macfie and the Colonsay branch of Clan MacNeil, it is in the council area of Argyll and Bute and ...

House, purchased with the island by Lord Strathcona and still occupied by his descendants today

File:Knebworth W front.JPG, Knebworth House

Knebworth House is an English country house in the parish of Knebworth in Hertfordshire, England. It is a Listed building#Categories of listed building, Grade II* listed building. Its gardens are also listed Register of Historic Parks and Gar ...

, leased by Lord Strathcona from 1899 until his death

See also

*Canadian peers and baronets

Canadian peers and baronets () exist in both the peerage of France recognized by the Monarch of Canada (the same as the Monarch of the United Kingdom) and the peerage of the United Kingdom.

In 1627, French Cardinal Richelieu introduced the sei ...

* Glencoe House

* Glencoe Lochan

* Golden Square Mile

The Golden Square Mile (, ), also known as the Square Mile, is the nostalgic name given to an urban neighbourhood developed principally between 1850 and 1930 at the foot of Mount Royal, in the west-central section of downtown Montreal in Quebec, Ca ...

Notes

References

* *External links

* *Sir Donald Alexander Smith, Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal fonds

- Library and Archives Canada *

Photograph: Sir Donald Smith, Lord Strathcona in 1895. McCord Museum

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Strathcona And Mount Royal, Donald Smith, 1st Baron 1820 births 1914 deaths Nobility from Moray Barons in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Canadian peers High commissioners of Canada to the United Kingdom Canadian Presbyterians Canadian philanthropists Canadian railway entrepreneurs Chancellors by university and college in Canada Chancellors of McGill University Chancellors of the University of Aberdeen Deputy lieutenants of Argyllshire Governors of the Hudson's Bay Company Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Independent Conservative MPs in the Canadian House of Commons, Smith Canadian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Canadian Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order 19th-century members of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba, Smith Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Manitoba, Smith Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Quebec, Smith Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Canadian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom 19th-century members of the Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories, Smith Scottish emigrants to pre-Confederation Quebec, Smith, Donald Burials at Highgate Cemetery, Smith, Donald Rectors of the University of Aberdeen Anglophone Quebec people Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12), Smith, Donald Alexander Bank of Montreal presidents People associated with the University of Birmingham 19th-century Canadian businesspeople Immigrants to Lower Canada BP people Peers of the United Kingdom created by Queen Victoria Lord Strathcona's Horse (Royal Canadians) 19th-century members of the House of Commons of Canada