CretaceousŌĆōPaleogene Extinction Event on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The CretaceousŌĆōPaleogene (KŌĆōPg) extinction event (also known as the CretaceousŌĆōTertiary extinction) was a sudden

There is significant variation in the fossil record as to the extinction rate of

There is significant variation in the fossil record as to the extinction rate of

The order Squamata, which is represented today by lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians (worm lizards), radiated into various ecological niches during the

The order Squamata, which is represented today by lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians (worm lizards), radiated into various ecological niches during the

Excluding a few controversial claims, scientists agree that all non-avian dinosaurs became extinct at the KŌĆōPg boundary. The dinosaur fossil record has been interpreted to show both a decline in diversity and no decline in diversity during the last few million years of the Cretaceous, and it may be that the quality of the dinosaur fossil record is simply not good enough to permit researchers to distinguish between the options. There is no evidence that late Maastrichtian non-avian dinosaurs could burrow, swim, or dive, which suggests they were unable to shelter themselves from the worst parts of any environmental stress that occurred at the KŌĆōPg boundary. It is possible that small dinosaurs (other than birds) did survive, but they would have been deprived of food, as herbivorous dinosaurs would have found plant material scarce and carnivores would have quickly found prey in short supply.

The growing consensus about the endothermy of dinosaurs (see

Excluding a few controversial claims, scientists agree that all non-avian dinosaurs became extinct at the KŌĆōPg boundary. The dinosaur fossil record has been interpreted to show both a decline in diversity and no decline in diversity during the last few million years of the Cretaceous, and it may be that the quality of the dinosaur fossil record is simply not good enough to permit researchers to distinguish between the options. There is no evidence that late Maastrichtian non-avian dinosaurs could burrow, swim, or dive, which suggests they were unable to shelter themselves from the worst parts of any environmental stress that occurred at the KŌĆōPg boundary. It is possible that small dinosaurs (other than birds) did survive, but they would have been deprived of food, as herbivorous dinosaurs would have found plant material scarce and carnivores would have quickly found prey in short supply.

The growing consensus about the endothermy of dinosaurs (see

In North American terrestrial sequences, the extinction event is best represented by the marked discrepancy between the rich and relatively abundant late-Maastrichtian pollen record and the post-boundary fern spike. A highly informative sequence of dinosaur-bearing rocks from the KŌĆōPg boundary is found in western North America, particularly the late Maastrichtian-age

In North American terrestrial sequences, the extinction event is best represented by the marked discrepancy between the rich and relatively abundant late-Maastrichtian pollen record and the post-boundary fern spike. A highly informative sequence of dinosaur-bearing rocks from the KŌĆōPg boundary is found in western North America, particularly the late Maastrichtian-age

In 1980, a team of researchers consisting of

In 1980, a team of researchers consisting of  This hypothesis was viewed as radical when first proposed, but additional evidence soon emerged. The boundary clay was found to be full of minute

This hypothesis was viewed as radical when first proposed, but additional evidence soon emerged. The boundary clay was found to be full of minute  Further research identified the giant

Further research identified the giant

Tanis, a mixed marine-continental event deposit at the KPG Boundary in North Dakota caused by a seiche triggered by seismic waves of the Chicxulub Impact

Paper No. 113-15, presented 23 October 2017 at the GSA Annual Meeting, Seattle, Washington, USA.DePalma, R. ''et al.'' (2017

Paper No. 113-16, presented 23 October 2017 at the GSA Annual Meeting, Seattle, Washington, USA. Amber from the site has been reported to contain microtektites matching those of the Chicxulub impact event. Some researchers question the interpretation of the findings at the site or are skeptical of the team leader, Robert DePalma, who had not yet received his Ph.D. in geology at the time of the discovery and whose commercial activities have been regarded with suspicion.

In March 2010, an international panel of 41 scientists reviewed 20 years of scientific literature and endorsed the asteroid hypothesis, specifically the Chicxulub impact, as the cause of the extinction, ruling out other theories such as massive

In March 2010, an international panel of 41 scientists reviewed 20 years of scientific literature and endorsed the asteroid hypothesis, specifically the Chicxulub impact, as the cause of the extinction, ruling out other theories such as massive

The KŌĆōPg extinction had a profound effect on the evolution of life on Earth. The elimination of dominant Cretaceous groups allowed other organisms to take their place, causing a remarkable amount of species diversification during the Paleogene Period. The most striking example is the replacement of dinosaurs by mammals. After the KŌĆōPg extinction, mammals evolved rapidly to fill the niches left vacant by the dinosaurs. Also significant, within the mammalian genera, new species were approximately 9.1% larger after the KŌĆōPg boundary.

Other groups also substantially diversified. Based on molecular sequencing and fossil dating, many species of birds (the Neoaves group in particular) appeared to radiate after the KŌĆōPg boundary. They even produced giant, flightless forms, such as the herbivorous ''

The KŌĆōPg extinction had a profound effect on the evolution of life on Earth. The elimination of dominant Cretaceous groups allowed other organisms to take their place, causing a remarkable amount of species diversification during the Paleogene Period. The most striking example is the replacement of dinosaurs by mammals. After the KŌĆōPg extinction, mammals evolved rapidly to fill the niches left vacant by the dinosaurs. Also significant, within the mammalian genera, new species were approximately 9.1% larger after the KŌĆōPg boundary.

Other groups also substantially diversified. Based on molecular sequencing and fossil dating, many species of birds (the Neoaves group in particular) appeared to radiate after the KŌĆōPg boundary. They even produced giant, flightless forms, such as the herbivorous ''

Papers and presentations resulting from the 2016 Chicxulub drilling project

ĆöThe

What killed the dinosaurs?

ĆöUniversity of California Museum of Paleontology (1995)

The Great Chicxulub Debate 2004

Ćö

mass extinction

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp change in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. I ...

of three-quarters of the plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclu ...

and animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, approximately 66 million years ago. With the exception of some ectothermic

An ectotherm (from the Greek () "outside" and () "heat") is an organism in which internal physiological sources of heat are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.Davenport, John. Animal Life ...

species such as sea turtles and crocodilians

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period (Cenomanian stage) and are the closest living ...

, no tetrapods

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids (reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosaurs, extinct therapsi ...

weighing more than survived. It marked the end of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

Period, and with it the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

era, while heralding the beginning of the Cenozoic era, which continues to this day.

In the geologic record

The geologic record in stratigraphy, paleontology and other natural sciences refers to the entirety of the layers of rock strata. That is, deposits laid down by volcanism or by deposition of sediment derived from weathering detritus (clays, sand ...

, the KŌĆōPg event is marked by a thin layer of sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sa ...

called the KŌĆōPg boundary, which can be found throughout the world in marine and terrestrial rocks. The boundary clay shows unusually high levels of the metal iridium

Iridium is a chemical element with the symbol Ir and atomic number 77. A very hard, brittle, silvery-white transition metal of the platinum group, it is considered the second-densest naturally occurring metal (after osmium) with a density of ...

, which is more common in asteroids than in the Earth's crust.

As originally proposed in 1980 by a team of scientists led by Luis Alvarez and his son Walter

Walter may refer to:

People

* Walter (name), both a surname and a given name

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930ŌĆō1968)

* Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born 19 ...

, it is now generally thought that the KŌĆōPg extinction was caused by the impact of a massive asteroid , 66 million years ago, which devastated the global environment, mainly through a lingering impact winter

An impact winter is a hypothesized period of prolonged cold weather due to the impact of a large asteroid or comet on the Earth's surface. If an asteroid were to strike land or a shallow body of water, it would eject an enormous amount of dust, ...

which halted photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

in plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclu ...

s and plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucia ...

. The impact hypothesis, also known as the Alvarez hypothesis

The Alvarez hypothesis posits that the mass extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs and many other living things during the CretaceousŌĆōPaleogene extinction event was caused by the impact of a large asteroid on the Earth. Prior to 2013, it was c ...

, was bolstered by the discovery of the Chicxulub crater

The Chicxulub crater () is an impact crater buried underneath the Yucat├Īn Peninsula in Mexico. Its center is offshore near the community of Chicxulub, after which it is named. It was formed slightly over 66 million years ago when a large a ...

in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de M├®xico) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

's Yucat├Īn Peninsula

The Yucat├Īn Peninsula (, also , ; es, Pen├Łnsula de Yucat├Īn ) is a large peninsula in southeastern Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north ...

in the early 1990s, which provided conclusive evidence that the KŌĆōPg boundary clay represented debris from an asteroid impact

An impact event is a collision between astronomical objects causing measurable effects. Impact events have physical consequences and have been found to regularly occur in planetary systems, though the most frequent involve asteroids, comets or me ...

. The fact that the extinctions occurred simultaneously provides strong evidence that they were caused by the asteroid. A 2016 drilling project into the Chicxulub peak ring

A peak ring crater is a type of complex crater, which is different from a multi-ringed basin or central-peak crater. A central peak is not seen; instead, a roughly circular ring or plateau, possibly discontinuous, surrounds the crater's center, ...

confirmed that the peak ring comprised granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies under ...

ejected within minutes from deep in the earth, but contained hardly any gypsum

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula . It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, blackboard or sidewalk chalk, and drywal ...

, the usual sulfate-containing sea floor rock in the region: the gypsum would have vaporized and dispersed as an aerosol into the atmosphere, causing longer-term effects on the climate and food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), de ...

. In October 2019, researchers reported that the event rapidly acidified the oceans, producing ecological collapse

Ecological collapse refers to a situation where an ecosystem suffers a drastic, possibly permanent, reduction in carrying capacity for all organisms, often resulting in mass extinction. Usually, an ecological collapse is precipitated by a disast ...

and, in this way as well, produced long-lasting effects on the climate, and accordingly was a key reason for the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous.

Other causal or contributing factors to the extinction may have been the Deccan Traps and other volcanic eruptions, climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warmingŌĆöthe ongoing increase in global average temperatureŌĆöand its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

, and sea level change. However, in January 2020, scientists reported that climate-modeling of the extinction event favored the asteroid impact

An impact event is a collision between astronomical objects causing measurable effects. Impact events have physical consequences and have been found to regularly occur in planetary systems, though the most frequent involve asteroids, comets or me ...

and not volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the surface called a ...

.

A wide range of terrestrial species perished in the KŌĆōPg extinction, the best-known being the non-avian dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s, along with mammals, birds, lizards, insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three ...

s, plants, and all the pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 ...

s. In the oceans, the KŌĆōPg extinction killed off plesiosaurs

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: ŽĆ╬╗╬ĘŽā╬»╬┐Žé, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared i ...

and mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Greek ' meaning 'lizard') comprise a group of extinct, large marine reptiles from the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains were discovered in a limestone quarry at Maastricht on ...

s and devastated teleost

Teleostei (; Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts ), is, by far, the largest infraclass in the class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes, containing 96% of all extant species of fish. Tele ...

fish, shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

s, mollusk

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is e ...

s (especially ammonites

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttl ...

, which became extinct), and many species of plankton. It is estimated that 75% or more of all species on Earth vanished. Yet the extinction also provided evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary opportunities: in its wake, many groups underwent remarkable adaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic int ...

ŌĆösudden and prolific divergence into new forms and species within the disrupted and emptied ecological niches. Mammals in particular diversified in the Paleogene, evolving new forms such as horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

s, whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

s, bat

Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera.''cheir'', "hand" and ŽĆŽä╬ĄŽüŽī╬Į''pteron'', "wing". With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most ...

s, and primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians ( monkeys and apes, the latter including ...

s. The surviving group of dinosaurs were avians, a few species of ground and water fowl, which radiated into all modern species of birds. Among other groups, teleost fish and perhaps lizards also radiated.

Extinction patterns

The KŌĆōPg extinction event was severe, global, rapid, and selective, eliminating a vast number of species. Based on marine fossils, it is estimated that 75% or more of all species were made extinct. The event appears to have affected all continents at the same time. Non-aviandinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s, for example, are known from the Maastrichtian

The Maastrichtian () is, in the ICS geologic timescale, the latest age (uppermost stage) of the Late Cretaceous Epoch or Upper Cretaceous Series, the Cretaceous Period or System, and of the Mesozoic Era or Erathem. It spanned the interval ...

of North America, Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, Asia, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, South America, and Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

, but are unknown from the Cenozoic anywhere in the world. Similarly, fossil pollen shows devastation of the plant communities in areas as far apart as New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

, Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: ąÉą╗čÅčüą║ą░, Alyaska; ale, Alax╠ésxax╠é; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, An├Īaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

, China, and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmassesŌĆöthe North Island () and the South Island ()ŌĆöand over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

.

Despite the event's severity, there was significant variability in the rate of extinction between and within different clades. Species that depended on photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

declined or became extinct as atmospheric particles blocked sunlight and reduced the solar energy reaching the ground. This plant extinction caused a major reshuffling of the dominant plant groups. Omnivores

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nut ...

, insectivores

A robber fly eating a hoverfly

An insectivore is a carnivorous animal or plant that eats insects. An alternative term is entomophage, which can also refer to the human practice of eating insects.

The first vertebrate insectivores were ...

, and carrion-eaters survived the extinction event, perhaps because of the increased availability of their food sources. No purely herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpar ...

or carnivorous mammals seem to have survived. Rather, the surviving mammals and birds fed on insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three ...

s, worm

Worms are many different distantly related bilateral animals that typically have a long cylindrical tube-like body, no limbs, and no eyes (though not always).

Worms vary in size from microscopic to over in length for marine polychaete wo ...

s, and snail

A snail is, in loose terms, a shelled gastropod. The name is most often applied to land snails, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs. However, the common name ''snail'' is also used for most of the members of the molluscan class G ...

s, which in turn fed on detritus (dead plant and animal matter).

In stream communities, few animal groups became extinct, because such communities rely less directly on food from living plants, and more on detritus washed in from the land, protecting them from extinction. Similar, but more complex patterns have been found in the oceans. Extinction was more severe among animals living in the water column

A water column is a conceptual column of water from the surface of a sea, river or lake to the bottom sediment.Munson, B.H., Axler, R., Hagley C., Host G., Merrick G., Richards C. (2004).Glossary. ''Water on the Web''. University of Minnesota-D ...

than among animals living on or in the sea floor. Animals in the water column are almost entirely dependent on primary production

In ecology, primary production is the synthesis of organic compounds from atmospheric or aqueous carbon dioxide. It principally occurs through the process of photosynthesis, which uses light as its source of energy, but it also occurs through ...

from living phytoplankton, while animals on the ocean floor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

always or sometimes feed on detritus. Coccolithophorids and mollusk

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is e ...

s (including ammonites, rudist

Rudists are a group of extinct box-, tube- or ring-shaped marine heterodont bivalves belonging to the order Hippuritida that arose during the Late Jurassic and became so diverse during the Cretaceous that they were major reef-building organisms ...

s, freshwater snails, and mussels), and those organisms whose food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), de ...

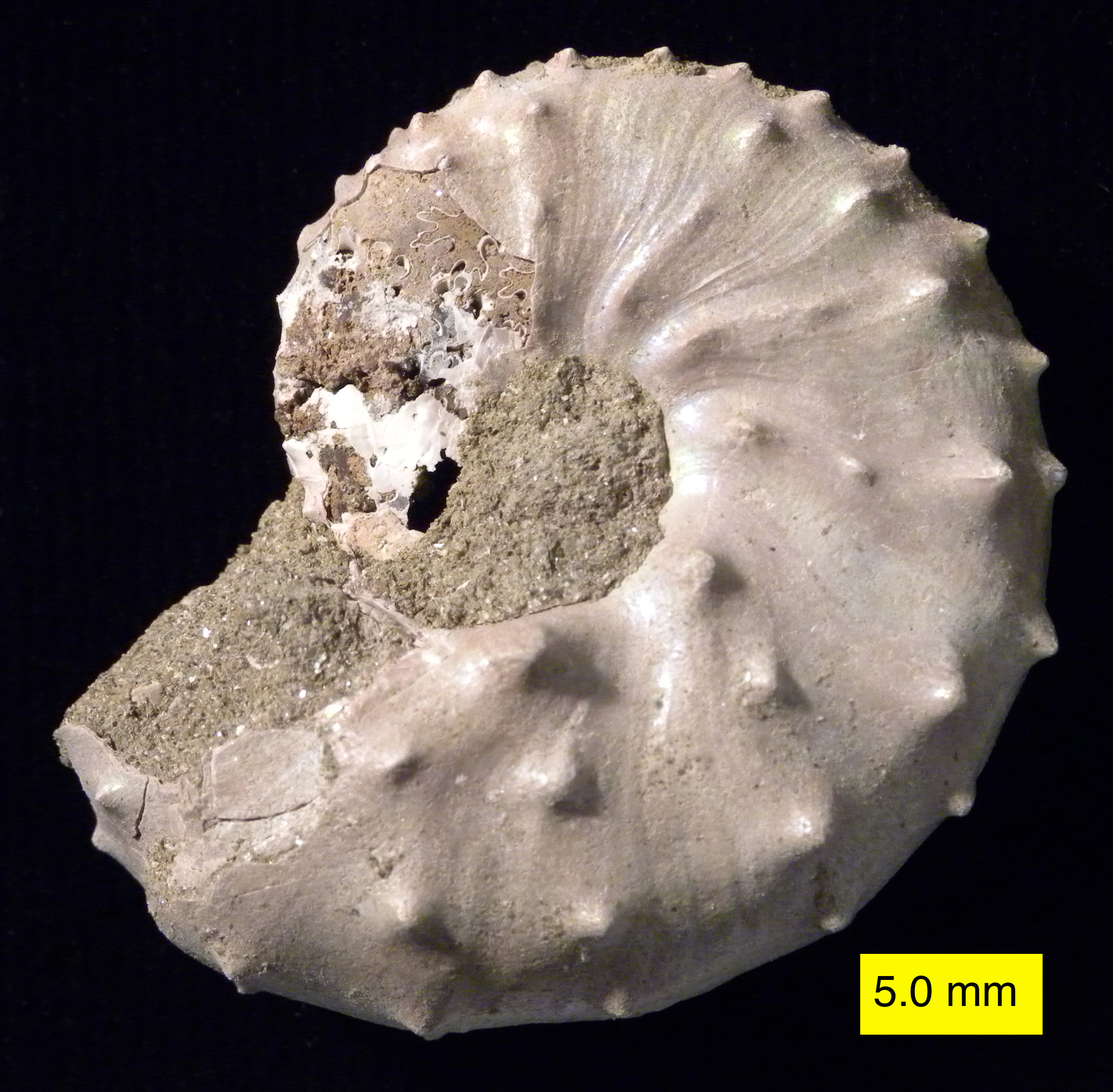

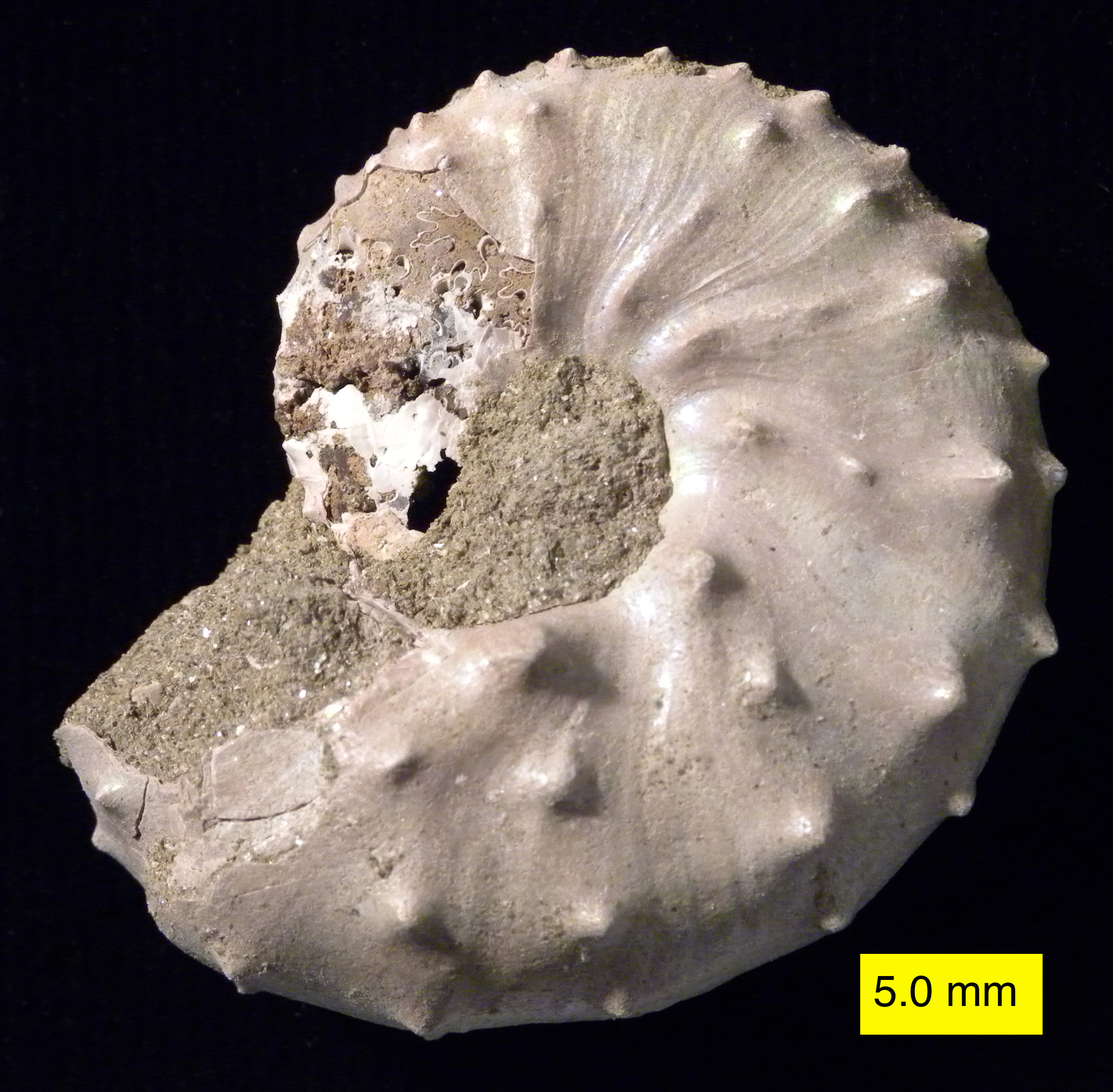

included these shell builders, became extinct or suffered heavy losses. For example, it is thought that ammonites

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttl ...

were the principal food of mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Greek ' meaning 'lizard') comprise a group of extinct, large marine reptiles from the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains were discovered in a limestone quarry at Maastricht on ...

s, a group of giant marine reptiles that became extinct at the boundary. The largest air-breathing survivors of the event, crocodyliform

Crocodyliformes is a clade of crurotarsan archosaurs, the group often traditionally referred to as "crocodilians". They are the first members of Crocodylomorpha to possess many of the features that define later relatives. They are the only pseudo ...

s and champsosaurs, were semi-aquatic and had access to detritus. Modern crocodilians can live as scavengers and survive for months without food, and their young are small, grow slowly, and feed largely on invertebrates and dead organisms for their first few years. These characteristics have been linked to crocodilian survival at the end of the Cretaceous.

After the KŌĆōPg extinction event, biodiversity required substantial time to recover, despite the existence of abundant vacant ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

s.

Microbiota

The KŌĆōPg boundary represents one of the most dramatic turnovers in thefossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

for various calcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcareous'' is used as an ad ...

nanoplankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a cruc ...

that formed the calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar t ...

deposits for which the Cretaceous is named. The turnover in this group is clearly marked at the species level. Statistical analysis of marine losses at this time suggests that the decrease in diversity was caused more by a sharp increase in extinctions than by a decrease in speciation. The KŌĆōPg boundary record of dinoflagellates is not so well understood, mainly because only microbial cyst

A microbial cyst is a resting or dormant stage of a microorganism, usually a bacterium or a protist or rarely an invertebrate animal, that helps the organism to survive in unfavorable environmental conditions. It can be thought of as a state of ...

s provide a fossil record, and not all dinoflagellate species have cyst-forming stages, which likely causes diversity to be underestimated. Recent studies indicate that there were no major shifts in dinoflagellates through the boundary layer.

Radiolaria

The Radiolaria, also called Radiozoa, are protozoa of diameter 0.1ŌĆō0.2 mm that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell into the inner and outer portions of endoplasm and ectoplasm. The el ...

have left a geological record since at least the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start of the Silurian Period Mya.

T ...

times, and their mineral fossil skeletons can be tracked across the KŌĆōPg boundary. There is no evidence of mass extinction of these organisms, and there is support for high productivity of these species in southern high latitudes as a result of cooling temperatures in the early Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period in the modern Cenozoic Era. The name is a combination of the Ancient Greek ''pal ...

. Approximately 46% of diatom species survived the transition from the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

to the Upper Paleocene, a significant turnover in species but not a catastrophic extinction.

The occurrence of plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucia ...

ic foraminifera

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly ...

across the KŌĆōPg boundary has been studied since the 1930s. Research spurred by the possibility of an impact event at the KŌĆōPg boundary resulted in numerous publications detailing planktonic foraminiferal extinction at the boundary; there is ongoing debate between groups which think the evidence indicates substantial extinction of these species at the KŌĆōPg boundary, and those who think the evidence supports multiple extinctions and expansions through the boundary.

Numerous species of benthic foraminifera became extinct during the event, presumably because they depend on organic debris for nutrients, while biomass in the ocean is thought to have decreased. As the marine microbiota recovered, it is thought that increased speciation of benthic foraminifera resulted from the increase in food sources. Phytoplankton recovery in the early Paleocene provided the food source to support large benthic foraminiferal assemblages, which are mainly detritus-feeding. Ultimate recovery of the benthic populations occurred over several stages lasting several hundred thousand years into the early Paleocene.

Marine invertebrates

There is significant variation in the fossil record as to the extinction rate of

There is significant variation in the fossil record as to the extinction rate of marine invertebrates

Marine invertebrates are the invertebrates that live in marine habitats. Invertebrate is a blanket term that includes all animals apart from the vertebrate members of the chordate phylum. Invertebrates lack a vertebral column, and some have ev ...

across the KŌĆōPg boundary. The apparent rate is influenced by a lack of fossil records, rather than extinctions.

Ostracod

Ostracods, or ostracodes, are a class of the Crustacea (class Ostracoda), sometimes known as seed shrimp. Some 70,000 species (only 13,000 of which are extant) have been identified, grouped into several orders. They are small crustaceans, typi ...

s, a class of small crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group can ...

s that were prevalent in the upper Maastrichtian, left fossil deposits in a variety of locations. A review of these fossils shows that ostracod diversity was lower in the Paleocene than any other time in the Cenozoic. Current research cannot ascertain whether the extinctions occurred prior to, or during, the boundary interval.

Approximately 60% of late-Cretaceous Scleractinia

Scleractinia, also called stony corals or hard corals, are marine animals in the phylum Cnidaria that build themselves a hard skeleton. The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc in which a ...

coral

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and ...

genera failed to cross the KŌĆōPg boundary into the Paleocene. Further analysis of the coral extinctions shows that approximately 98% of colonial species, ones that inhabit warm, shallow tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

waters, became extinct. The solitary corals, which generally do not form reefs and inhabit colder and deeper (below the photic zone) areas of the ocean were less impacted by the KŌĆōPg boundary. Colonial coral species rely upon symbiosis with photosynthetic algae, which collapsed due to the events surrounding the KŌĆōPg boundary, but the use of data from coral fossils to support KŌĆōPg extinction and subsequent Paleocene recovery, must be weighed against the changes that occurred in coral ecosystems through the KŌĆōPg boundary.

The numbers of cephalopod, echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any member of the phylum Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the s ...

, and bivalve genera exhibited significant diminution after the KŌĆōPg boundary. Most species of brachiopods

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of trochozoan animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, wh ...

, a small phylum of marine invertebrates, survived the KŌĆōPg extinction event and diversified during the early Paleocene.

Except for nautiloid

Nautiloids are a group of marine cephalopods (Mollusca) which originated in the Late Cambrian and are represented today by the living ''Nautilus'' and '' Allonautilus''. Fossil nautiloids are diverse and speciose, with over 2,500 recorded specie ...

s (represented by the modern order Nautilida

The Nautilida constitute a large and diverse order of generally coiled nautiloid cephalopods that began in the mid Paleozoic and continues to the present with a single family, the Nautilidae which includes two genera, ''Nautilus'' and ''Allonauti ...

) and coleoids (which had already diverged into modern octopodes, squids, and cuttlefish) all other species of the molluscan class Cephalopoda became extinct at the KŌĆōPg boundary. These included the ecologically significant belemnoids, as well as the ammonoids

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

, a group of highly diverse, numerous, and widely distributed shelled cephalopods. Researchers have pointed out that the reproductive strategy of the surviving nautiloids, which rely upon few and larger eggs, played a role in outsurviving their ammonoid counterparts through the extinction event. The ammonoids utilized a planktonic strategy of reproduction (numerous eggs and planktonic larvae), which would have been devastated by the KŌĆōPg extinction event. Additional research has shown that subsequent to this elimination of ammonoids from the global biota, nautiloids began an evolutionary radiation into shell shapes and complexities theretofore known only from ammonoids.

Approximately 35% of echinoderm genera became extinct at the KŌĆōPg boundary, although taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

that thrived in low-latitude, shallow-water environments during the late Cretaceous had the highest extinction rate. Mid-latitude, deep-water echinoderms were much less affected at the KŌĆōPg boundary. The pattern of extinction points to habitat loss, specifically the drowning of carbonate platform

A carbonate platform is a sedimentary body which possesses topographic relief, and is composed of autochthonic calcareous deposits. Platform growth is mediated by sessile organisms whose skeletons build up the reef or by organisms (usually micr ...

s, the shallow-water reefs in existence at that time, by the extinction event.

Other invertebrate groups, including rudists

Rudists are a group of extinct box-, tube- or ring-shaped marine heterodont bivalves belonging to the order Hippuritida that arose during the Late Jurassic and became so diverse during the Cretaceous that they were major reef-building organis ...

(reef-building clams) and inoceramids (giant relatives of modern scallops), also became extinct at the KŌĆōPg boundary.

Fish

There are fossil records ofjawed fishes

Gnathostomata (; from Greek: (') "jaw" + (') "mouth") are the jawed vertebrates. Gnathostome diversity comprises roughly 60,000 species, which accounts for 99% of all living vertebrates, including humans. In addition to opposing jaws, living ...

across the KŌĆōPg boundary, which provide good evidence of extinction patterns of these classes of marine vertebrates. While the deep-sea realm was able to remain seemingly unaffected, there was an equal loss between the open marine apex predators and the durophagous

Durophagy is the eating behavior of animals that consume hard-shelled or exoskeleton bearing organisms, such as corals, shelled mollusks, or crabs. It is mostly used to describe fish, but is also used when describing reptiles, including fossil tu ...

demersal feeders on the continental shelf. Within cartilaginous fish, approximately 7 out of the 41 families of neoselachians (modern sharks

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachimorp ...

, skates, and rays) disappeared after this event and batoids (skates and rays) lost nearly all the identifiable species, while more than 90% of teleost fish

Teleostei (; Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts ), is, by far, the largest infraclass in the class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes, containing 96% of all extant species of fish. Tel ...

(bony fish) families survived.

In the Maastrichtian age, 28 shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

families and 13 batoid families thrived, of which 25 and 9, respectively, survived the KŌĆōT boundary event. Forty-seven of all neoselachian genera cross the KŌĆōT boundary, with 85% being sharks. Batoids display with 15%, a comparably low survival rate.

There is evidence of a mass extinction of bony fishes at a fossil site immediately above the KŌĆōPg boundary layer on Seymour Island

Seymour Island or Marambio Island, is an island in the chain of 16 major islands around the tip of the Graham Land on the Antarctic Peninsula. Graham Land is the closest part of Antarctica to South America. It lies within the section of the isla ...

near Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

, apparently precipitated by the KŌĆōPg extinction event; the marine and freshwater environments of fishes mitigated the environmental effects of the extinction event.

Terrestrial invertebrates

Insect damage to the fossilized leaves offlowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants th ...

s from fourteen sites in North America was used as a proxy for insect diversity across the KŌĆōPg boundary and analyzed to determine the rate of extinction. Researchers found that Cretaceous sites, prior to the extinction event, had rich plant and insect-feeding diversity. During the early Paleocene, flora were relatively diverse with little predation from insects, even 1.7 million years after the extinction event.

Terrestrial plants

There is overwhelming evidence of global disruption of plant communities at the KŌĆōPg boundary. Extinctions are seen both in studies of fossil pollen, and fossil leaves. In North America, the data suggests massive devastation and mass extinction of plants at the KŌĆōPg boundary sections, although there were substantial megafloral changes before the boundary. In North America, approximately 57% of plant species became extinct. In high southern hemisphere latitudes, such as New Zealand and Antarctica, the mass die-off of flora caused no significant turnover in species, but dramatic and short-term changes in the relative abundance of plant groups. In some regions, the Paleocene recovery of plants began with recolonizations by fern species, represented as afern spike

In paleontology, a fern spike is the occurrence of unusually high spore abundance of ferns in the fossil record, usually immediately (in a geological sense) after an extinction event. The spikes are believed to represent a large, temporary inc ...

in the geologic record; this same pattern of fern recolonization was observed after the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption.

Due to the wholesale destruction of plants at the KŌĆōPg boundary, there was a proliferation of saprotrophic

Saprotrophic nutrition or lysotrophic nutrition is a process of chemoheterotrophic extracellular digestion involved in the processing of decayed (dead or waste) organic matter. It occurs in saprotrophs, and is most often associated with fungi ( ...

organisms, such as fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

, that do not require photosynthesis and use nutrients from decaying vegetation. The dominance of fungal species lasted only a few years while the atmosphere cleared and plenty of organic matter to feed on was present. Once the atmosphere cleared, photosynthetic organisms, initially ferns and other ground-level plants, returned. Just two species of fern appear to have dominated the landscape for centuries after the event.

Polyploidy

Polyploidy is a condition in which the biological cell, cells of an organism have more than one pair of (Homologous chromosome, homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have Cell nucleus, nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they ha ...

appears to have enhanced the ability of flowering plants to survive the extinction, probably because the additional copies of the genome such plants possessed allowed them to more readily adapt to the rapidly changing environmental conditions that followed the impact.

Fungi

While it appears that many fungi were wiped out at the K-Pg boundary, it is worth noting that evidence has been found indicating that some fungal species thrived in the years after the extinction event. Microfossils from that period indicate a great increase in fungal spores, long before the resumption of plentiful fern spores in the recovery after the impact. Monoporisporites and hypha are almost exclusive microfossils for a short span during and after the iridium boundary. These saprophytes would not need sunlight, allowing them to survive during a period when the atmosphere was likely clogged with dust and sulfur aerosols. The proliferation of fungi has occurred after several extinction events, including thePermianŌĆōTriassic extinction event

The PermianŌĆōTriassic (PŌĆōT, PŌĆōTr) extinction event, also known as the Latest Permian extinction event, the End-Permian Extinction and colloquially as the Great Dying, formed the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods, as ...

, the largest known mass extinction in Earth's history, with up to 96% of all species suffering extinction.

Amphibians

There is limited evidence for extinction of amphibians at the KŌĆōPg boundary. A study of fossil vertebrates across the KŌĆōPg boundary inMontana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

concluded that no species of amphibian became extinct. Yet there are several species of Maastrichtian amphibian, not included as part of this study, which are unknown from the Paleocene. These include the frog '' Theatonius lancensis'' and the albanerpetontid

The Albanerpetontidae are an extinct family of small amphibians, native to the Northern Hemisphere during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic. The only members of the order Allocaudata, they are thought to be allied with living amphibians belonging to Lissa ...

'' Albanerpeton galaktion''; therefore, some amphibians do seem to have become extinct at the boundary. The relatively low levels of extinction seen among amphibians probably reflect the low extinction rates seen in freshwater animals.

Non-archosaurs

Turtles

More than 80% of Cretaceousturtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked t ...

species passed through the KŌĆōPg boundary. All six turtle families in existence at the end of the Cretaceous survived into the Paleogene and are represented by living species.

Lepidosauria

The living non-archosaurian reptile taxa,lepidosauria

The Lepidosauria (, from Greek meaning ''scaled lizards'') is a subclass or superorder of reptiles, containing the orders Squamata and Rhynchocephalia. Squamata includes snakes, lizards, and amphisbaenians. Squamata contains over 9,000 species ...

ns (snake

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more j ...

s, lizards and tuatara

Tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') are reptiles endemic to New Zealand. Despite their close resemblance to lizards, they are part of a distinct lineage, the order Rhynchocephalia. The name ''tuatara'' is derived from the M─üori language and m ...

s), survived across the KŌĆōPg boundary.

The rhynchocephalians were a widespread and relatively successful group of lepidosaurians during the early Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

, but began to decline by the mid-Cretaceous, although they were very successful in South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

. They are represented today by a single genus (the Tuatara), located exclusively in New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmassesŌĆöthe North Island () and the South Island ()ŌĆöand over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

.

The order Squamata, which is represented today by lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians (worm lizards), radiated into various ecological niches during the

The order Squamata, which is represented today by lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians (worm lizards), radiated into various ecological niches during the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

and was successful throughout the Cretaceous. They survived through the KŌĆōPg boundary and are currently the most successful and diverse group of living reptiles, with more than 6,000 extant species. Many families of terrestrial squamates became extinct at the boundary, such as monstersauria

Monstersauria is a clade of anguimorph lizards, defined as all taxa more closely related to ''Heloderma'' than '' Varanus''. It includes ''Heloderma'', as well as several extinct genera, such as '' Estesia'', '' Primaderma'' and '' Gobiderma'', ...

ns and polyglyphanodonts, and fossil evidence indicates they suffered very heavy losses in the KŌĆōPg event, only recovering 10 million years after it.

Non-archosaurian marine reptiles

Giant non-archosaurian aquatic reptiles such asmosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Greek ' meaning 'lizard') comprise a group of extinct, large marine reptiles from the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains were discovered in a limestone quarry at Maastricht on ...

s and plesiosaurs

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: ŽĆ╬╗╬ĘŽā╬»╬┐Žé, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared i ...

, which were the top marine predators of their time, became extinct by the end of the Cretaceous. The ichthyosaurs had disappeared from fossil records before the mass extinction occurred.

Archosaurs

The archosaur clade includes two surviving groups,crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest livi ...

ns and bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s, along with the various extinct groups of non-avian dinosaurs and pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 ...

s.

Crocodyliforms

Ten families of crocodilians or their close relatives are represented in the Maastrichtian fossil records, of which five died out prior to the KŌĆōPg boundary. Five families have both Maastrichtian and Paleocene fossil representatives. All of the surviving families ofcrocodyliforms

Crocodyliformes is a clade of crurotarsan archosaurs, the group often traditionally referred to as "crocodilians". They are the first members of Crocodylomorpha to possess many of the features that define later relatives. They are the only pseudo ...

inhabited freshwater and terrestrial environmentsŌĆöexcept for the Dyrosauridae

Dyrosauridae is a family of extinct neosuchian crocodyliforms that lived from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) to the Eocene. Dyrosaurid fossils are globally distributed, having been found in Africa, Asia, Europe, North America and South Ame ...

, which lived in freshwater and marine locations. Approximately 50% of crocodyliform representatives survived across the KŌĆōPg boundary, the only apparent trend being that no large crocodiles survived. Crocodyliform survivability across the boundary may have resulted from their aquatic niche and ability to burrow, which reduced susceptibility to negative environmental effects at the boundary. Jouve and colleagues suggested in 2008 that juvenile marine crocodyliforms lived in freshwater environments as do modern marine crocodile juveniles, which would have helped them survive where other marine reptiles became extinct; freshwater environments were not so strongly affected by the KŌĆōPg extinction event as marine environments were.

Pterosaurs

Two families of pterosaurs, Azhdarchidae andNyctosauridae

Nyctosauridae (meaning "night lizards" or "bat lizards") is a family of specialized soaring pterosaurs of the late Cretaceous Period of North America, Africa, and possibly Europe. It was named in 1889 by Henry Alleyne Nicholson and Richard Lydek ...

, were definitely present in the Maastrichtian, and they likely became extinct at the KŌĆōPg boundary. Several other pterosaur lineages may have been present during the Maastrichtian, such as the ornithocheirids, pteranodontids, nyctosaurids

Nyctosauridae (meaning "night lizards" or "bat lizards") is a Family (biology), family of specialized soaring pterosaurs of the late Cretaceous Period of North America, Africa, and possibly Europe. It was named in 1889 by Henry Alleyne Nicholson ...

, a possible tapejarid

Tapejaridae (from a Tupi word meaning "the old being") are a family of pterodactyloid pterosaurs from the Cretaceous period. Members are currently known from Brazil, England, Hungary, Morocco, Spain, the United States, and China. The most primit ...

, a possible thalassodromid

Thalassodrominae or Thalassodromidae (meaning "sea runners", due to previous misconceptions of skimming behavior; they are now thought to be terrestrial predators) is a group of azhdarchoid pterosaurs from the Cretaceous period. Its traditional ...

and a basal toothed taxon of uncertain affinities, though they are represented by fragmentary remains that are difficult to assign to any given group. While this was occurring, modern birds were undergoing diversification; traditionally it was thought that they replaced archaic birds and pterosaur groups, possibly due to direct competition, or they simply filled empty niches, but there is no correlation between pterosaur and avian diversities that are conclusive to a competition hypothesis, and small pterosaurs were present in the Late Cretaceous. At least some niches previously held by birds were reclaimed by pterosaurs prior to the KŌĆōPg event.

Birds

Mostpaleontologists

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or pal├”ontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of foss ...

regard birds as the only surviving dinosaurs (see Origin of birds

The scientific question of within which larger group of animals birds evolved has traditionally been called the "origin of birds". The present scientific consensus is that birds are a group of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs that originated ...

). It is thought that all non-avian theropods

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally ca ...

became extinct, including then-flourishing groups such as enantiornithines

The Enantiornithes, also known as enantiornithines or enantiornitheans in literature, are a group of extinct avialans ("birds" in the broad sense), the most abundant and diverse group known from the Mesozoic era. Almost all retained teeth and cla ...

and hesperornithiforms. Several analyses of bird fossils show divergence of species prior to the KŌĆōPg boundary, and that duck, chicken, and ratite bird relatives coexisted with non-avian dinosaurs. Large collections of bird fossils representing a range of different species provides definitive evidence for the persistence of archaic birds to within 300,000 years of the KŌĆōPg boundary. The absence of these birds in the Paleogene is evidence that a mass extinction of archaic birds took place there.

The most successful and dominant group of avialan

Avialae ("bird wings") is a clade containing the only living dinosaurs, the birds. It is usually defined as all theropod dinosaurs more closely related to birds (Aves) than to deinonychosaurs, though alternative definitions are occasionally used ...

s, enantiornithes, were wiped out. Only a small fraction of ground and water-dwelling Cretaceous bird species survived the impact, giving rise to today's birds. The only bird group known for certain to have survived the KŌĆōPg boundary is the Aves. Avians may have been able to survive the extinction as a result of their abilities to dive, swim, or seek shelter in water and marshlands. Many species of avians can build burrows, or nest in tree holes, or termite nests, all of which provided shelter from the environmental effects at the KŌĆōPg boundary. Long-term survival past the boundary was assured as a result of filling ecological niches left empty by extinction of non-avian dinosaurs. The open niche space and relative scarcity of predators following the K-Pg extinction allowed for adaptive radiation of various avian groups. Ratites, for example, rapidly diversified in the early Paleogene and are believed to have convergently developed flightlessness at least three to six times, often fulfilling the niche space for large herbivores once occupied by non-avian dinosaurs.

Non-avian dinosaurs

Excluding a few controversial claims, scientists agree that all non-avian dinosaurs became extinct at the KŌĆōPg boundary. The dinosaur fossil record has been interpreted to show both a decline in diversity and no decline in diversity during the last few million years of the Cretaceous, and it may be that the quality of the dinosaur fossil record is simply not good enough to permit researchers to distinguish between the options. There is no evidence that late Maastrichtian non-avian dinosaurs could burrow, swim, or dive, which suggests they were unable to shelter themselves from the worst parts of any environmental stress that occurred at the KŌĆōPg boundary. It is possible that small dinosaurs (other than birds) did survive, but they would have been deprived of food, as herbivorous dinosaurs would have found plant material scarce and carnivores would have quickly found prey in short supply.

The growing consensus about the endothermy of dinosaurs (see

Excluding a few controversial claims, scientists agree that all non-avian dinosaurs became extinct at the KŌĆōPg boundary. The dinosaur fossil record has been interpreted to show both a decline in diversity and no decline in diversity during the last few million years of the Cretaceous, and it may be that the quality of the dinosaur fossil record is simply not good enough to permit researchers to distinguish between the options. There is no evidence that late Maastrichtian non-avian dinosaurs could burrow, swim, or dive, which suggests they were unable to shelter themselves from the worst parts of any environmental stress that occurred at the KŌĆōPg boundary. It is possible that small dinosaurs (other than birds) did survive, but they would have been deprived of food, as herbivorous dinosaurs would have found plant material scarce and carnivores would have quickly found prey in short supply.

The growing consensus about the endothermy of dinosaurs (see dinosaur physiology

The physiology of dinosaurs has historically been a controversial subject, particularly their thermoregulation. Recently, many new lines of evidence have been brought to bear on dinosaur physiology generally, including not only metabolic systems a ...

) helps to understand their full extinction in contrast with their close relatives, the crocodilians. Ectothermic ("cold-blooded") crocodiles have very limited needs for food (they can survive several months without eating), while endothermic ("warm-blooded") animals of similar size need much more food to sustain their faster metabolism. Thus, under the circumstances of food chain disruption previously mentioned, non-avian dinosaurs died out, while some crocodiles survived. In this context, the survival of other endothermic animals, such as some birds and mammals, could be due, among other reasons, to their smaller needs for food, related to their small size at the extinction epoch.

Whether the extinction occurred gradually or suddenly has been debated, as both views have support from the fossil record. A study of 29 fossil sites in Catalan Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyr├®n├®es ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Piren├©us ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

of Europe in 2010 supports the view that dinosaurs there had great diversity until the asteroid impact, with more than 100 living species. More recent research indicates that this figure is obscured by taphonomic

Taphonomy is the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized or preserved in the paleontological record. The term ''taphonomy'' (from Greek , 'burial' and , 'law') was introduced to paleontology in 1940 by Soviet scientist Ivan Efremov t ...

biases and the sparsity of the continental fossil record. The results of this study, which were based on estimated real global biodiversity, showed that between 628 and 1,078 non-avian dinosaur species were alive at the end of the Cretaceous and underwent sudden extinction after the CretaceousŌĆōPaleogene extinction event. Alternatively, interpretation based on the fossil-bearing rocks along the Red Deer River

The Red Deer River is a river in Alberta and a small portion of Saskatchewan, Canada. It is a major tributary of the South Saskatchewan River and is part of the larger Saskatchewan-Nelson system that empties into Hudson Bay.

Red Deer River h ...

in Alberta, Canada, supports the gradual extinction of non-avian dinosaurs; during the last 10 million years of the Cretaceous layers there, the number of dinosaur species seems to have decreased from about 45 to approximately 12. Other scientists have made the same assessment following their research.

Several researchers support the existence of Paleocene non-avian dinosaurs. Evidence of this existence is based on the discovery of dinosaur remains in the Hell Creek Formation

The Hell Creek Formation is an intensively studied division of mostly Upper Cretaceous and some lower Paleocene rocks in North America, named for exposures studied along Hell Creek, near Jordan, Montana. The formation stretches over portions of ...

up to above and 40,000 years later than the KŌĆōPg boundary. Pollen samples recovered near a fossilized hadrosaur

Hadrosaurids (), or duck-billed dinosaurs, are members of the ornithischian family Hadrosauridae. This group is known as the duck-billed dinosaurs for the flat duck-bill appearance of the bones in their snouts. The ornithopod family, which incl ...

femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates wit ...

recovered in the Ojo Alamo Sandstone at the San Juan River in Colorado, indicate that the animal lived during the Cenozoic, approximately (about 1 million years after the KŌĆōPg extinction event). If their existence past the KŌĆōPg boundary can be confirmed, these hadrosaurids would be considered a dead clade walking

In ecology, extinction debt is the future extinction of species due to events in the past. The phrases dead clade walking and survival without recovery express the same idea.

Extinction debt occurs because of time delays between impacts on a speci ...

. The scientific consensus is that these fossils were eroded from their original locations and then re-buried in much later sediments (also known as reworked fossils).

Choristodere

The choristoderes (semi-aquaticarchosauromorphs

Archosauromorpha (Greek for "ruling lizard forms") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs (such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds) rather than lepidosaurs (such as tuataras, liz ...

) survived across the KŌĆōPg boundary but would die out in the early Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

. Studies on ''Champsosaurus

''Champsosaurus'' is an extinct genus of crocodile-like choristodere reptile, known from the Late Cretaceous and early Paleogene periods of North America and Europe (Campanian-Paleocene). The name ''Champsosaurus'' is thought to come from , () ...

'' palatal teeth suggest that there were dietary changes among the various species across the KŌĆōPg event.

Mammals

All major Cretaceous mammalian lineages, including monotremes (egg-laying mammals),multituberculates

Multituberculata (commonly known as multituberculates, named for the multiple tubercles of their teeth) is an extinct order of rodent-like mammals with a fossil record spanning over 130 million years. They first appeared in the Middle Jurassic, a ...

, metatheria

Metatheria is a mammalian clade that includes all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. First proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1880, it is a more inclusive group than the marsupials; it contains all marsupials as wel ...

ns, eutheria

Eutheria (; from Greek , 'good, right' and , 'beast'; ) is the clade consisting of all therian mammals that are more closely related to placentals than to marsupials.

Eutherians are distinguished from noneutherians by various phenotypic tra ...

ns, dryolestoideans, and gondwanatheres

Gondwanatheria is an extinct group of mammaliaforms that lived in parts of Gondwana, including Madagascar, India, South America, Africa and Antarctica during the Upper Cretaceous through the Paleogene (and possibly much earlier, if '' Allostaff ...

survived the KŌĆōPg extinction event, although they suffered losses. In particular, metatherians largely disappeared from North America, and the Asian deltatheroida

Deltatheroida is an extinct group of basal metatherians that were distantly related to modern marsupials. The majority of known members of the group lived in the Cretaceous; one species, '' Gurbanodelta kara'', is known from the late Paleocene ( ...

ns became extinct (aside from the lineage leading to '' Gurbanodelta''). In the Hell Creek beds of North America, at least half of the ten known multituberculate species and all eleven metatherians species are not found above the boundary. Multituberculates in Europe and North America survived relatively unscathed and quickly bounced back in the Paleocene, but Asian forms were devastated, never again to represent a significant component of mammalian fauna. A recent study indicates that metatherians suffered the heaviest losses at the KŌĆōPg event, followed by multituberculates, while eutherians recovered the quickest.

Mammalian species began diversifying approximately 30 million years prior to the KŌĆōPg boundary. Diversification of mammals stalled across the boundary.

Current research indicates that mammals did not explosively diversify across the KŌĆōPg boundary, despite the ecological niches made available by the extinction of dinosaurs. Several mammalian orders have been interpreted as diversifying immediately after the KŌĆōPg boundary, including Chiroptera (bat

Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera.''cheir'', "hand" and ŽĆŽä╬ĄŽüŽī╬Į''pteron'', "wing". With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most ...

s) and Cetartiodactyla (a diverse group that today includes whales and dolphins and even-toed ungulate

The even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla , ) are ungulatesŌĆöhoofed animalsŌĆöwhich bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes: the third and fourth. The other three toes are either present, absent, vestigial, or pointing poster ...

s), although recent research concludes that only marsupial

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in a ...

orders diversified soon after the KŌĆōPg boundary.

KŌĆōPg boundary mammalian species were generally small, comparable in size to rats; this small size would have helped them find shelter in protected environments. It is postulated that some early monotremes, marsupials, and placentals were semiaquatic or burrowing, as there are multiple mammalian lineages with such habits today. Any burrowing or semiaquatic mammal would have had additional protection from KŌĆōPg boundary environmental stresses.

Evidence

North American fossils

In North American terrestrial sequences, the extinction event is best represented by the marked discrepancy between the rich and relatively abundant late-Maastrichtian pollen record and the post-boundary fern spike. A highly informative sequence of dinosaur-bearing rocks from the KŌĆōPg boundary is found in western North America, particularly the late Maastrichtian-age

In North American terrestrial sequences, the extinction event is best represented by the marked discrepancy between the rich and relatively abundant late-Maastrichtian pollen record and the post-boundary fern spike. A highly informative sequence of dinosaur-bearing rocks from the KŌĆōPg boundary is found in western North America, particularly the late Maastrichtian-age Hell Creek Formation

The Hell Creek Formation is an intensively studied division of mostly Upper Cretaceous and some lower Paleocene rocks in North America, named for exposures studied along Hell Creek, near Jordan, Montana. The formation stretches over portions of ...

of Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

. Comparison with the older Judith River Formation

The Judith River Formation is a fossil-bearing geologic formation in Montana, and is part of the Judith River Group. It dates to the Late Cretaceous, between 79 and 75.3 million years ago, corresponding to the "Judithian" land vertebrate age. It ...

(Montana) and Dinosaur Park Formation

The Dinosaur Park Formation is the uppermost member of the Belly River Group (also known as the Judith River Group), a major geologic unit in southern Alberta. It was deposited during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, between about 76. ...

(Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

), which both date from approximately 75 Ma, provides information on the changes in dinosaur populations over the last 10 million years of the Cretaceous. These fossil beds are geographically limited, covering only part of one continent.