Circe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Circe (; grc, , ) is an enchantress and a minor

In the ''

In the ''

In Homer's ''Odyssey'', an 8th-century BC sequel to his

In Homer's ''Odyssey'', an 8th-century BC sequel to his  Circe invites the hero Odysseus' crew to a feast of familiar food, a pottage of cheese and meal, sweetened with honey and laced with wine, but also mixed with one of her magical potions that turns them into swine. Only Eurylochus, who suspects treachery, does not go in. He escapes to warn Odysseus and the others who have remained with the ship. Before Odysseus reaches Circe's palace,

Circe invites the hero Odysseus' crew to a feast of familiar food, a pottage of cheese and meal, sweetened with honey and laced with wine, but also mixed with one of her magical potions that turns them into swine. Only Eurylochus, who suspects treachery, does not go in. He escapes to warn Odysseus and the others who have remained with the ship. Before Odysseus reaches Circe's palace,

Towards the end of Hesiod's ''

Towards the end of Hesiod's ''

One of the most enduring literary themes connected with the figure of Circe was her ability to change men into animals. There was much speculation concerning how this could be, whether the human consciousness changed at the same time, and even whether it was a change for the better. The Gryllus dialogue was taken up by another Italian writer, Giovan Battista Gelli, in his ''La Circe'' (1549). This is a series of ten philosophical and moral dialogues between Ulysses and the humans transformed into various animals, ranging from an oyster to an elephant, in which Circe sometimes joins. Most argue against changing back; only the last animal, a philosopher in its former existence, wants to. The work was translated into English soon after in 1557 by Henry Iden. Later the English poet

One of the most enduring literary themes connected with the figure of Circe was her ability to change men into animals. There was much speculation concerning how this could be, whether the human consciousness changed at the same time, and even whether it was a change for the better. The Gryllus dialogue was taken up by another Italian writer, Giovan Battista Gelli, in his ''La Circe'' (1549). This is a series of ten philosophical and moral dialogues between Ulysses and the humans transformed into various animals, ranging from an oyster to an elephant, in which Circe sometimes joins. Most argue against changing back; only the last animal, a philosopher in its former existence, wants to. The work was translated into English soon after in 1557 by Henry Iden. Later the English poet  Two other Italians wrote rather different works that centre on the animal within the human. One was

Two other Italians wrote rather different works that centre on the animal within the human. One was  The same theme occupies La Fontaine's late fable, "The Companions of Ulysses" (XII.1, 1690), which also echoes Plutarch and Gelli. Once transformed, every animal (which includes a lion, a bear, a wolf and a mole) protests that their lot is better and refuses to be restored to human shape. Charles Dennis shifted this fable to stand at the head of his translation of La Fontaine, ''Select Fables'' (1754), but provides his own conclusion that ''When Mortals from the path of Honour stray, / And the strong passions over reason sway, / What are they then but Brutes? / 'Tis vice alone that constitutes / Th'enchanting wand and magic bowl, The exterior form of Man they wear, / But are in fact both Wolf and Bear, / The transformation's in the Soul.''

The same theme occupies La Fontaine's late fable, "The Companions of Ulysses" (XII.1, 1690), which also echoes Plutarch and Gelli. Once transformed, every animal (which includes a lion, a bear, a wolf and a mole) protests that their lot is better and refuses to be restored to human shape. Charles Dennis shifted this fable to stand at the head of his translation of La Fontaine, ''Select Fables'' (1754), but provides his own conclusion that ''When Mortals from the path of Honour stray, / And the strong passions over reason sway, / What are they then but Brutes? / 'Tis vice alone that constitutes / Th'enchanting wand and magic bowl, The exterior form of Man they wear, / But are in fact both Wolf and Bear, / The transformation's in the Soul.''

The Venetian

The Venetian

That central image is echoed by the blood-striped flower of T.S.Eliot's student poem "Circe's Palace" (1909) in the

That central image is echoed by the blood-striped flower of T.S.Eliot's student poem "Circe's Palace" (1909) in the  There remain some poems that bear her name that have more to do with their writers' private preoccupations than with reinterpreting her myth. The link with it in

There remain some poems that bear her name that have more to do with their writers' private preoccupations than with reinterpreting her myth. The link with it in

It has further been suggested that

It has further been suggested that

Scenes from the ''Odyssey'' are common on Greek pottery, the Circe episode among them. The two most common representations have Circe surrounded by the transformed sailors and Odysseus threatening the sorceress with his sword. In the case of the former, the animals are not always boars but also include, for instance, the ram, dog and lion on the 6th-century BC Boston

Scenes from the ''Odyssey'' are common on Greek pottery, the Circe episode among them. The two most common representations have Circe surrounded by the transformed sailors and Odysseus threatening the sorceress with his sword. In the case of the former, the animals are not always boars but also include, for instance, the ram, dog and lion on the 6th-century BC Boston

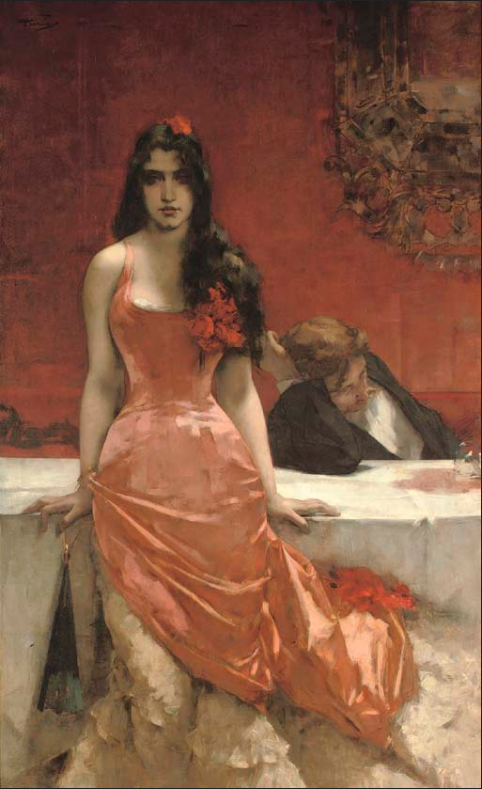

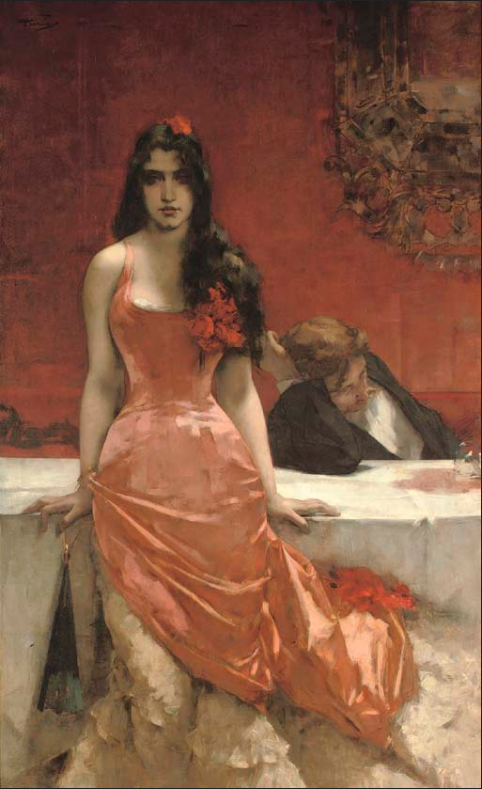

Soon afterwards, the notorious

Soon afterwards, the notorious

Beside the verse dramas, with their lyrical interludes, on which many operas were based, there were poetic texts which were set as secular

Beside the verse dramas, with their lyrical interludes, on which many operas were based, there were poetic texts which were set as secular

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

*

''The Myths of Hyginus''

Edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960. *

Full text available at poetryintranslation.com

*

Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library

*

Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

*

The Bryn Mawr Classical Review

* Lactantius Placidus, ''Commentarii in Statii Thebaida''. *

''The Dictionary of Classical Mythology''

Wiley-Blackwell, 1996,

"Circe" p. 104

* Milton, John, A Masque Presented at Ludlow Castle [Comus] line 153 "mother Circe". * William Smith (lexicographer), Smith, William; ''Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology'', London (1873)

"Circe"

* {{Authority control Circe, Characters in the Argonautica Characters in the Odyssey Children of Helios French literature Greek goddesses Greek mythological witches Italian literature Pigs in literature Women of Poseidon Magic goddesses Metamorphoses characters Characters in Greek mythology Metamorphoses into animals in Greek mythology Opera history Women in Greek mythology Shapeshifting Deities in the Aeneid Witchcraft in folklore and mythology

goddess

A goddess is a female deity. In many known cultures, goddesses are often linked with literal or metaphorical pregnancy or imagined feminine roles associated with how women and girls are perceived or expected to behave. This includes themes of s ...

in ancient Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the Cosmogony, origin and Cosmology#Metaphysical co ...

and religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

. She is either a daughter of the Titan Helios

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Helios (; grc, , , Sun; Homeric Greek: ) is the deity, god and personification of the Sun (Solar deity). His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyper ...

and the Oceanid

In Greek mythology, the Oceanids or Oceanides (; grc, Ὠκεανίδες, Ōkeanídes, pl. of grc, Ὠκεανίς, Ōkeanís, label=none) are the nymphs who were the three thousand (a number interpreted as meaning "innumerable") daughters o ...

nymph

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label=Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ty ...

Perse or the goddess Hecate

Hecate or Hekate, , ; grc-dor, Ἑκάτᾱ, Hekátā, ; la, Hecatē or . is a goddess in ancient Greek religion and mythology, most often shown holding a pair of torches, a key, snakes, or accompanied by dogs, and in later periods depicte ...

and Aeëtes

Aeëtes (; , ; , ), or Aeeta, was a king of Colchis in Greek mythology. The name comes from the ancient Greek word (, "eagle").

Family

Aeëtes was the son of Sun god Helios and the Oceanid Perseis, brother of Circe, Perses and Pasiphaë, and ...

. Circe was renowned for her vast knowledge of potions and herbs. Through the use of these and a magic wand

A wand is a thin, light-weight rod that is held with one hand, and is traditionally made of wood, but may also be made of other materials, such as metal or plastic.

Long versions of wands are often styled in forms of staves or sceptres, which c ...

or staff, she would transform

Transform may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Transform (scratch), a type of scratch used by turntablists

* ''Transform'' (Alva Noto album), 2001

* ''Transform'' (Howard Jones album) or the title song, 2019

* ''Transform'' (Powerman 5000 album ...

her enemies, or those who offended her, into animals.

The best known of her legends is told in Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'' when Odysseus

Odysseus ( ; grc-gre, Ὀδυσσεύς, Ὀδυσεύς, OdysseúsOdyseús, ), also known by the Latin variant Ulysses ( , ; lat, UlyssesUlixes), is a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the ''Odyssey''. Odysse ...

visits her island of Aeaea

__NOTOC__

Aeaea, Ææa or Eëä ( or ; grc, Αἰαία, Aiaíā ) was a Greek mythology, mythological island said to be the home of the goddess-sorceress Circe.

In Homer's ''Odyssey'', Odysseus tells Alcinous that he stayed here for one year ...

on the way back from the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has ...

and she changes most of his crew into swine. He manages to persuade her to return them to human shape, lives with her for a year and has sons by her, including Latinus

Latinus ( la, Latinus; Ancient Greek: Λατῖνος, ''Latînos'', or Λατεῖνος, ''Lateînos'') was a figure in both Greek and Roman mythology. He is often associated with the heroes of the Trojan War, namely Odysseus and Aeneas. Alth ...

and Telegonus

Telegonus (; Ancient Greek: Τηλέγονος means "born afar") is the name shared by three different characters in Greek mythology.

* Telegonus, a king of Egypt who was sometimes said to have married the nymph Io.

* Telegonus, a Thracian son ...

. Her ability to change others into animals is further highlighted by the story of Picus

Picus was a figure in Roman mythology, the first king of Latium. He was the son of Saturn, also known as Stercutus. He was the founder of the first Latin tribe and settlement, Laurentum, located a few miles to the Southeast of the site of the lat ...

, an Italian king whom she turns into a woodpecker for resisting her advances. Another story tells of her falling in love with the sea-god Glaucus

In Greek mythology, Glaucus (; grc, Γλαῦκος, Glaûkos, glimmering) was a Greek prophetic sea-god, born mortal and turned immortal upon eating a magical herb. It was believed that he came to the rescue of sailors and fishermen in storms, ...

, who prefers the nymph Scylla

In Greek mythology, Scylla), is obsolete. ( ; grc-gre, Σκύλλα, Skúlla, ) is a legendary monster who lives on one side of a narrow channel of water, opposite her counterpart Charybdis. The two sides of the strait are within an arrow's r ...

to her. In revenge, Circe poisoned the water where her rival bathed and turned her into a dreadful monster.

Depictions, even in Classical times, diverged from the detail in Homer's narrative, which was later to be reinterpreted morally as a cautionary story against drunkenness. Early philosophical questions were also raised about whether the change from being a human endowed with reason to being an unreasoning beast might not be preferable after all, and the resulting debate was to have a powerful impact during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

. Circe was also taken as the archetype of the predatory female. In the eyes of those from a later age, this behaviour made her notorious both as a magician and as a type of sexually-free woman. She has been frequently depicted as such in all the arts from the Renaissance down to modern times.

Western paintings established a visual iconography for the figure, but also went for inspiration to other stories concerning Circe that appear in Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

's ''Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' ( la, Metamorphōsēs, from grc, μεταμορφώσεις: "Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem from 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his ''magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the wo ...

''. The episodes of Scylla and Picus added the vice of violent jealousy to her bad qualities and made her a figure of fear as well as of desire.

Classical literature

Family and attributes

By most accounts, she was the daughter of thesun god

A solar deity or sun deity is a deity who represents the Sun, or an aspect of it. Such deities are usually associated with power and strength. Solar deities and Sun worship can be found throughout most of recorded history in various forms. The ...

Helios

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Helios (; grc, , , Sun; Homeric Greek: ) is the deity, god and personification of the Sun (Solar deity). His name is also Latinized as Helius, and he is often given the epithets Hyper ...

and Perse, one of the three thousand Oceanid

In Greek mythology, the Oceanids or Oceanides (; grc, Ὠκεανίδες, Ōkeanídes, pl. of grc, Ὠκεανίς, Ōkeanís, label=none) are the nymphs who were the three thousand (a number interpreted as meaning "innumerable") daughters o ...

nymph

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label=Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ty ...

s. In ''Orphic Argonautica

The ''Orphic Argonautica'' or ''Argonautica Orphica'' ( grc-gre, Ὀρφέως Ἀργοναυτικά) is a Greek epic poem dating from the 5th–6th centuries CE. It is narrated in the first person in the name of Orpheus and tells the story of ...

'', her mother is called Asterope instead. Her brothers were Aeëtes

Aeëtes (; , ; , ), or Aeeta, was a king of Colchis in Greek mythology. The name comes from the ancient Greek word (, "eagle").

Family

Aeëtes was the son of Sun god Helios and the Oceanid Perseis, brother of Circe, Perses and Pasiphaë, and ...

, keeper of the Golden Fleece

In Greek mythology, the Golden Fleece ( el, Χρυσόμαλλον δέρας, ''Chrysómallon déras'') is the fleece of the golden-woolled,, ''Khrusómallos''. winged ram, Chrysomallos, that rescued Phrixus and brought him to Colchis, where P ...

and father of Medea

In Greek mythology, Medea (; grc, Μήδεια, ''Mēdeia'', perhaps implying "planner / schemer") is the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis, a niece of Circe and the granddaughter of the sun god Helios. Medea figures in the myth of Jason an ...

, and Perses. Her sister was Pasiphaë

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, Pasiphaë (; grc-gre, Πασιφάη, Pasipháē, lit=wide-shining derived from πάσι (archaic dative plural) "for all" and φάος/φῶς ''phaos/phos'' "light") was a queen of Crete, and wa ...

, the wife of King Minos

In Greek mythology, Minos (; grc-gre, Μίνως, ) was a King of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. Every nine years, he made King Aegeus pick seven young boys and seven young girls to be sent to Daedalus's creation, the labyrinth, to be eaten ...

and mother of the Minotaur

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur ( , ;. grc, ; in Latin as ''Minotaurus'' ) is a mythical creature portrayed during classical antiquity with the head and tail of a bull and the body of a man or, as described by Roman poet Ovid, a being "pa ...

. Other accounts make her and her niece Medea

In Greek mythology, Medea (; grc, Μήδεια, ''Mēdeia'', perhaps implying "planner / schemer") is the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis, a niece of Circe and the granddaughter of the sun god Helios. Medea figures in the myth of Jason an ...

the daughters of Hecate

Hecate or Hekate, , ; grc-dor, Ἑκάτᾱ, Hekátā, ; la, Hecatē or . is a goddess in ancient Greek religion and mythology, most often shown holding a pair of torches, a key, snakes, or accompanied by dogs, and in later periods depicte ...

, the goddess of witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

by Aeëtes, usually said to be her brother instead. She was often confused with Calypso, due to her shifts in behavior and personality, and the association that both of them had with Odysseus

Odysseus ( ; grc-gre, Ὀδυσσεύς, Ὀδυσεύς, OdysseúsOdyseús, ), also known by the Latin variant Ulysses ( , ; lat, UlyssesUlixes), is a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the ''Odyssey''. Odysse ...

.

According to Greek legend, Circe lived on the island of Aeaea

__NOTOC__

Aeaea, Ææa or Eëä ( or ; grc, Αἰαία, Aiaíā ) was a Greek mythology, mythological island said to be the home of the goddess-sorceress Circe.

In Homer's ''Odyssey'', Odysseus tells Alcinous that he stayed here for one year ...

. Although Homer is vague when it comes to the island's whereabouts, in his epic poem ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jason a ...

'', the early 3rd BC author Apollonius of Rhodes

Apollonius of Rhodes ( grc, Ἀπολλώνιος Ῥόδιος ''Apollṓnios Rhódios''; la, Apollonius Rhodius; fl. first half of 3rd century BC) was an ancient Greek author, best known for the ''Argonautica'', an epic poem about Jason and t ...

locates Aeaea somewhere south of ''Aethalia'' (Elba

Elba ( it, isola d'Elba, ; la, Ilva) is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National ...

), within view of the Tyrrhenian shore (that is, the western coast of Italy). In the same poem, Circe's brother Aeëtes describes how Circe was transferred to Aeaea: "I noted it once after taking a ride in my father Helios' chariot, when he was taking my sister Circe to the western land and we came to the coast of the Tyrrhenian mainland, where she dwells to this day, very far from the Colchian

In Greco-Roman geography, Colchis (; ) was an exonym for the Georgian polity of Egrisi ( ka, ეგრისი) located on the coast of the Black Sea, centered in present-day western Georgia.

Its population, the Colchians are generally thou ...

land." A scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius claims that Apollonius is following Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

's tradition in making Circe arrive in Aeaea on Helios' chariot, while Valerius Flaccus writes that Circe was borne away by winged dragons. Roman poets associated her with the most ancient traditions of Latium, and made her home to be on the promontory of Circeo

Monte Circeo or Cape Circeo ( it, Promontorio del Circeo , la, Mons Circeius) is a mountain promontory that marks the southwestern limit of the former Pontine Marshes.located on the southwest coast of Italy near San Felice Circeo. At the nor ...

.

Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

describes Circe as "a dreadful goddess with lovely hair and human speech". Apollonius writes that she (just like every other descendant of Helios) had flashing golden eyes that shot out rays of light, with the author of ''Argonautica Orphica

The ''Orphic Argonautica'' or ''Argonautica Orphica'' ( grc-gre, Ὀρφέως Ἀργοναυτικά) is a Greek epic poem dating from the 5th–6th centuries CE. It is narrated in the first person in the name of Orpheus and tells the story of ...

'' noting that she had hair like fiery rays. Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

's ''The Cure for Love

''The Cure for Love'' is a 1949 British comedy film starring and directed by Robert Donat. The cast also includes Renee Asherson and Dora Bryan. The film was based on a hit play of the same name by Walter Greenwood about a mild-mannered soldier ...

'' implies that Circe might have been taught the knowledge of herbs and potions from her mother Perse, who seems to have had similar skills.

Pre-Odyssey

In the ''

In the ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jason a ...

'', Apollonius relates that Circe purified the Argonauts

The Argonauts (; Ancient Greek: ) were a band of heroes in Greek mythology, who in the years before the Trojan War (around 1300 BC) accompanied Jason to Colchis in his quest to find the Golden Fleece. Their name comes from their ship, '' Argo'', ...

for the murder of Medea's brother Absyrtus

In Greek mythology, Absyrtus (Ancient Greek: Ἄψυρτος) or Apsyrtus, was a Colchian prince and the younger brother of Medea. he was involved in Jason's escape with the golden fleece from Colchis

The Absyrtides were named after him.

Fami ...

, possibly reflecting an early tradition. In this poem, the Argonauts find Circe bathing in salt water; the animals that surround her are not former lovers transformed but primeval 'beasts, not resembling the beasts of the wild, nor yet like men in body, but with a medley of limbs'. Circe invites Jason, Medea and their crew into her mansion; uttering no words, they show her the still bloody sword they used to cut Absyrtus down, and Circe immediately realizes they've visited her to be purified of murder. She purifies them by slitting the throat of a suckling pig and letting the blood drip on them. Afterwards, Medea tells Circe their tale in great detail, albeit omitting the part of Absyrtus' murder; nevertheless Circe is not fooled, and greatly disapproves of their actions. However, out of pity for the girl, and on account of their kinship, she promises not to be an obstacle on their way, and orders Jason and Medea to leave her island immediately.

The sea-god Glaucus

In Greek mythology, Glaucus (; grc, Γλαῦκος, Glaûkos, glimmering) was a Greek prophetic sea-god, born mortal and turned immortal upon eating a magical herb. It was believed that he came to the rescue of sailors and fishermen in storms, ...

was in love with a beautiful maiden, Scylla

In Greek mythology, Scylla), is obsolete. ( ; grc-gre, Σκύλλα, Skúlla, ) is a legendary monster who lives on one side of a narrow channel of water, opposite her counterpart Charybdis. The two sides of the strait are within an arrow's r ...

, but she spurned his affections no matter how he tried to win her heart. Glaucus went to Circe, and asked her for a magic potion to make Scylla fall in love with him too. But Circe was smitten by Glaucus herself, and fell in love with him. But Glaucus did not love her back, and turned her offer of marriage down. Enraged, Circe used her knowledge of herbs and plants to take her revenge; she found the spot where Scylla usually took her bath, and poisoned the water. When Scylla went down to it to bathe, dogs sprang from her thighs and she was transformed into the familiar monster from the ''Odyssey''. In another, similar story, Picus

Picus was a figure in Roman mythology, the first king of Latium. He was the son of Saturn, also known as Stercutus. He was the founder of the first Latin tribe and settlement, Laurentum, located a few miles to the Southeast of the site of the lat ...

was a Latian king whom Circe turned into a woodpecker. He was the son of Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

, and a king of Latium

Latium ( , ; ) is the region of central western Italy in which the city of Rome was founded and grew to be the capital city of the Roman Empire.

Definition

Latium was originally a small triangle of fertile, volcanic soil (Old Latium) on whi ...

. He fell in love and married a nymph

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label=Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ty ...

, Canens, to whom he was utterly devoted. One day as he was hunting boars, he came upon Circe, who was gathering herbs in the woods. Circe fell immediately in love with him; but Picus, just like Glaucus before him, spurned her and declared that he would remain forever faithful to Canens. Circe, furious, turned Picus into a woodpecker. His wife Canens eventually wasted away in her mourning.

During the war between the gods and the giants, one of the giants, Picolous

In Greek mythology, Picolous ( grc, Πικόλοος, ) is the name of one of the Gigantes, the offspring of the earth goddess Gaia and the sky god Uranus (mythology), Uranus. Picolous fought against the Olympian gods during the Giants (Greek mytho ...

, fled the battle against the gods and came to Aeaea, Circe's island. He attempted to chase Circe away, only to be killed by Helios, Circe's ally and father. From the blood of the slain giant an herb came into existence; moly, named thus from the battle (malos) and with a white-coloured flower, either for the white Sun who had killed Picolous or the terrified Circe who turned white; the very plant, which mortals are unable to pluck from the ground, that Hermes would later give to Odysseus in order to defeat Circe.

Homer's ''Odyssey''

In Homer's ''Odyssey'', an 8th-century BC sequel to his

In Homer's ''Odyssey'', an 8th-century BC sequel to his Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has ...

epic ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odysse ...

'', Circe is initially described as a beautiful goddess living in a palace isolated in the midst of a dense wood on her island of Aeaea. Around her home prowl strangely docile lions and wolves. She lures any who land on the island to her home with her lovely singing while weaving on an enormous loom, but later drugs them so that they change shape. One of her Homeric epithets is ''polypharmakos'', "knowing many drugs or charms".

Circe invites the hero Odysseus' crew to a feast of familiar food, a pottage of cheese and meal, sweetened with honey and laced with wine, but also mixed with one of her magical potions that turns them into swine. Only Eurylochus, who suspects treachery, does not go in. He escapes to warn Odysseus and the others who have remained with the ship. Before Odysseus reaches Circe's palace,

Circe invites the hero Odysseus' crew to a feast of familiar food, a pottage of cheese and meal, sweetened with honey and laced with wine, but also mixed with one of her magical potions that turns them into swine. Only Eurylochus, who suspects treachery, does not go in. He escapes to warn Odysseus and the others who have remained with the ship. Before Odysseus reaches Circe's palace, Hermes

Hermes (; grc-gre, Ἑρμῆς) is an Olympian deity in ancient Greek religion and mythology. Hermes is considered the herald of the gods. He is also considered the protector of human heralds, travellers, thieves, merchants, and orato ...

, the messenger god sent by the goddess of wisdom Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarded as the patron and protectress of ...

, intercepts him and reveals how he might defeat Circe in order to free his crew from their enchantment. Hermes provides Odysseus with moly to protect him from Circe's magic. He also tells Odysseus that he must then draw his sword and act as if he were going to attack her. From there, as Hermes foretold, Circe would ask Odysseus to bed, but Hermes advises caution, for the treacherous goddess could still "unman" him unless he has her swear by the names of the gods that she will not take any further action against him. Following this advice, Odysseus is able to free his men.

After they have all remained on the island for a year, Circe advises Odysseus that he must first visit the Underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

...

, something a mortal has never yet done, in order to gain knowledge about how to appease the gods, return home safely and recover his kingdom. Circe also advises him on how this might be achieved and furnishes him with the protections he will need and the means to communicate with the dead. On his return, she further advises him about two possible routes home, warning him, however, that both carry great danger.

Post-Odyssey

Towards the end of Hesiod's ''

Towards the end of Hesiod's ''Theogony

The ''Theogony'' (, , , i.e. "the genealogy or birth of the gods") is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contains 10 ...

'' (c. 700 BC), it is stated that Circe bore Odysseus three sons: Agrius (otherwise unknown); Latinus

Latinus ( la, Latinus; Ancient Greek: Λατῖνος, ''Latînos'', or Λατεῖνος, ''Lateînos'') was a figure in both Greek and Roman mythology. He is often associated with the heroes of the Trojan War, namely Odysseus and Aeneas. Alth ...

; and Telegonus

Telegonus (; Ancient Greek: Τηλέγονος means "born afar") is the name shared by three different characters in Greek mythology.

* Telegonus, a king of Egypt who was sometimes said to have married the nymph Io.

* Telegonus, a Thracian son ...

, who ruled over the Tyrsenoi, that is the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, rou ...

. The ''Telegony'', an epic now lost, relates the later history of the last of these. Circe eventually informed her son who his absent father was and, when he set out to find Odysseus, gave him a poisoned spear. When Telegonus arrived in Ithaca, Odysseus was away in Thesprotia

Thesprotia (; el, Θεσπρωτία, ) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the Epirus region. Its capital and largest town is Igoumenitsa. Thesprotia is named after the Thesprotians, an ancient Greek tribe that inhabited the ...

, fighting the Brygi. Telegonus began to ravage the island; Odysseus came to defend his land. With the weapon Circe gave him, Telegonus killed his father unknowingly. Telegonus then brought back his father's corpse to Aeaea, together with Penelope

Penelope ( ; Ancient Greek: Πηνελόπεια, ''Pēnelópeia'', or el, Πηνελόπη, ''Pēnelópē'') is a character in Homer's ''Odyssey.'' She was the queen of Ithaca and was the daughter of Spartan king Icarius and naiad Periboea. Pe ...

and Odysseus' son by her, Telemachus

Telemachus ( ; grc, Τηλέμαχος, Tēlemakhos, lit=far-fighter), in Greek mythology, is the son of Odysseus and Penelope, who is a central character in Homer's ''Odyssey''. When Telemachus reached manhood, he visited Pylos and Sparta in se ...

. After burying Odysseus, Circe made the other three immortal.

Circe married Telemachus, and Telegonus married Penelope by the advice of Athena. According to an alternative version depicted in Lycophron

Lycophron (; grc-gre, Λυκόφρων ὁ Χαλκιδεύς; born about 330–325 BC) was a Hellenistic Greek tragic poet, grammarian, sophist, and commentator on comedy, to whom the poem ''Alexandra'' is attributed (perhaps falsely).

Life and ...

's 3rd-century BC poem ''Alexandra'' (and John Tzetzes

John Tzetzes ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης Τζέτζης, Iōánnēs Tzétzēs; c. 1110, Constantinople – 1180, Constantinople) was a Byzantine poet and grammarian who is known to have lived at Constantinople in the 12th century.

He was able to p ...

' scholia

Scholia (singular scholium or scholion, from grc, σχόλιον, "comment, interpretation") are grammatical, critical, or explanatory comments – original or copied from prior commentaries – which are inserted in the margin of th ...

on it), Circe used magical herbs to bring Odysseus back to life after he had been killed by Telegonus. Odysseus then gave Telemachus to Circe's daughter Cassiphone in marriage. Sometime later, Telemachus had a quarrel with his mother-in-law and killed her; Cassiphone then killed Telemachus to avenge her mother's death. On hearing of this, Odysseus died of grief.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus ( grc, Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνασσεύς,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary sty ...

(1.72.5) cites Xenagoras, the 2nd-century BC historian, as claiming that Odysseus and Circe had three different sons: Rhomos

Rhomos ( grc, Ῥώμος) was in Greek and Roman mythology a son of Odysseus and Circe.Anteias Anteias or Antias ( grc, Ἀντείας or grc, Ἀντίας) was in Roman mythology a figure in some versions of Rome's foundation myth. He was one of the three sons of Odysseus by Circe, and brother to Rhomos and Ardeas, each of whom were said ...

, and Ardeias, who respectively founded three cities called by their names: Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, Antium

Antium was an ancient coastal town in Latium, south of Rome. An oppidum was founded by people of Latial culture (11th century BC or the beginning of the 1st millennium BC), then it was the main stronghold of the Volsci people until it was conquere ...

, and Ardea.

In the later 5th-century CE epic ''Dionysiaca

The ''Dionysiaca'' {{IPAc-en, ˌ, d, aɪ, ., ə, ., n, ᵻ, ˈ, z, aɪ, ., ə, ., k, ə ( grc-gre, Διονυσιακά, ''Dionysiaká'') is an ancient Greek epic poem and the principal work of Nonnus. It is an epic in 48 books, the longest survi ...

'', its author Nonnus

Nonnus of Panopolis ( grc-gre, Νόννος ὁ Πανοπολίτης, ''Nónnos ho Panopolítēs'', 5th century CE) was the most notable Greek epic poet of the Imperial Roman era. He was a native of Panopolis (Akhmim) in the Egyptian Thebai ...

mentions Phaunus, Circe's son by the sea god Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

.

Other works

Three ancient plays about Circe have been lost: the work of the tragedianAeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek ...

and of the 4th-century BC comic dramatists Ephippus of Athens

Ephippus of Athens ( grc-gre, Ἔφιππος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος) was an Ancient Greek comic poet of the middle comedy.

We learn this from the testimonies of Suidas and Antiochus of Alexandria, and from the allusions in his fragments to Plat ...

and Anaxilas. The first told the story of Odysseus' encounter with Circe. Vase paintings from the period suggest that Odysseus' half-transformed animal-men formed the chorus in place of the usual Satyr

In Greek mythology, a satyr ( grc-gre, :wikt:σάτυρος, σάτυρος, sátyros, ), also known as a silenus or ''silenos'' ( grc-gre, :wikt:Σειληνός, σειληνός ), is a male List of nature deities, nature spirit with ears ...

s. Fragments of Anaxilas also mention the transformation and one of the characters complains of the impossibility of scratching his face now that he is a pig.

The theme of Circe turning men into a variety of animals was elaborated by later writers. In his episodic work ''The Sorrows of Love'' (first century BC), Parthenius of Nicaea Parthenius of Nicaea ( el, Παρθένιος ὁ Νικαεύς) or Myrlea ( el, ὁ Μυρλεανός) in Bithynia was a Greeks, Greek Philologist, grammarian and poet. According to the ''Suda'', he was the son of Heraclides and Eudora, or accord ...

interpolated another episode into the time that Odysseus was staying with Circe. Pestered by the amorous attentions of King Calchus the Daunian, the sorceress invited him to a drugged dinner that turned him into a pig and then shut him up in her sties. He was only released when his army came searching for him on the condition that he would never set foot on her island again.

Among Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

treatments, Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan_War#Sack_of_Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to ...

'' relates how Aeneas skirts the Italian island where Circe dwells and hears the cries of her many male victims, who now number more than the pigs of earlier accounts: ''The roars of lions that refuse the chain, / The grunts of bristled boars, and groans of bears, / And herds of howling wolves that stun the sailors' ears.'' In Ovid's 1st-century poem ''Metamorphoses

The ''Metamorphoses'' ( la, Metamorphōsēs, from grc, μεταμορφώσεις: "Transformations") is a Latin narrative poem from 8 CE by the Roman poet Ovid. It is considered his ''magnum opus''. The poem chronicles the history of the wo ...

'', the fourth episode covers Circe's encounter with Ulysses (the Roman name of Odysseus), whereas book 14 covers the stories of Picus and Glaucus.

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

took up the theme in a lively dialogue that was later to have several imitators. Contained in his 1st-century ''Moralia

The ''Moralia'' ( grc, Ἠθικά ''Ethika''; loosely translated as "Morals" or "Matters relating to customs and mores") is a group of manuscripts dating from the 10th–13th centuries, traditionally ascribed to the 1st-century Greek scholar Plu ...

'' is the Gryllus episode in which Circe allows Odysseus to interview a fellow Greek turned into a pig. After his interlocutor informs Odysseus that his present existence is preferable to the human, they engage in a philosophical dialogue in which every human value is questioned and beasts are proved to be of superior wisdom and virtue.

Ancient cult

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

writes that a tomb-shrine of Circe was attended in one of the Pharmacussae islands, off the coast of Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean Se ...

, typical for hero-worship. Circe was also venerated in Mount Circeo

Monte Circeo or Cape Circeo ( it, Promontorio del Circeo , la, Mons Circeius) is a mountain promontory that marks the southwestern limit of the former Pontine Marshes.located on the southwest coast of Italy near San Felice Circeo. At the nort ...

, in the Italian peninsula, which took its name after her according to ancient legend. Strabo says that Circe had a shrine in the small town, and that the people there kept a bowl they claimed belonged to Odysseus. The promontory is occupied by ruins of a platform attributed with great probability to a temple of Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

or Circe.

Later literature

Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was somet ...

provided a digest of what was known of Circe during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

in his ''De mulieribus claris

''De Mulieribus Claris'' or ''De Claris Mulieribus'' (Latin for "Concerning Famous Women") is a collection of biographies of historical and mythological women by the Florentine author Giovanni Boccaccio, composed in Latin prose in 1361–1362. ...

'' (''Famous Women'', 1361–1362). While following the tradition that she lived in Italy, he comments wryly that there are now many more temptresses like her to lead men astray.

There is a very different interpretation of the encounter with Circe in John Gower

John Gower (; c. 1330 – October 1408) was an English poet, a contemporary of William Langland and the Pearl Poet, and a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civ ...

's long didactic poem ''Confessio Amantis

''Confessio Amantis'' ("The Lover's Confession") is a 33,000-line Middle English poem by John Gower, which uses the confession made by an ageing lover to the chaplain of Venus as a frame story for a collection of shorter narrative poems. Accord ...

'' (1380). Ulysses is depicted as deeper in sorcery and readier of tongue than Circe and through this means he leaves her pregnant with Telegonus. Most of the account deals with the son's later quest for and accidental killing of his father, drawing the moral that only evil can come of the use of sorcery.

The story of Ulysses and Circe was retold as an episode in Georg Rollenhagen's German verse epic, ''Froschmeuseler'' (''The Frogs and Mice'', Magdeburg, 1595). In this 600-page expansion of the pseudo-Homeric ''Batrachomyomachia

The ''Batrachomyomachia'' ( grc, Βατραχομυομαχία, from , "frog", , "mouse", and , "battle") or ''Battle of the Frogs and Mice'' is a comic epic, or a parody of the ''Iliad'', commonly attributed to Homer, although other authors ha ...

'', it is related at the court of the mice and takes up sections 5–8 of the first part.

In Lope de Vega

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio ( , ; 25 November 156227 August 1635) was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist. He was one of the key figures in the Spanish Golden Age of Baroque literature. His reputation in the world of Spanish literature ...

's miscellany ''La Circe – con otras rimas y prosas'' (1624), the story of her encounter with Ulysses appears as a verse epic in three cantos. This takes its beginning from Homer's account, but it is then embroidered; in particular, Circe's love for Ulysses remains unrequited.

As "Circe's Palace", Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

retold the Homeric account as the third section in his collection of stories from Greek mythology, ''Tanglewood Tales

''Tanglewood Tales for Boys and Girls'' (1853) is a book by American author Nathaniel Hawthorne, a sequel to ''A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys''. It is a re-writing of well-known Greek myths in a volume for children.

Overview

The book includes t ...

'' (1853). The transformed Picus continually appears in this, trying to warn Ulysses, and then Eurylochus, of the danger to be found in the palace, and is rewarded at the end by being given back his human shape. In most accounts Ulysses only demands this for his own men.

In her survey of the ''Transformations of Circe'', Judith Yarnall comments of this figure, who started out as a comparatively minor goddess of unclear origin, that "What we know for certain – what Western literature attests to – is her remarkable staying power…These different versions of Circe's myth can be seen as mirrors, sometimes clouded and sometimes clear, of the fantasies and assumptions of the cultures that produced them." After appearing as just one of the characters that Odysseus encounters on his wandering, "Circe herself, in the twists and turns of her story through the centuries, has gone through far more metamorphoses than those she inflicted on Odysseus's companions."

Reasoning beasts

One of the most enduring literary themes connected with the figure of Circe was her ability to change men into animals. There was much speculation concerning how this could be, whether the human consciousness changed at the same time, and even whether it was a change for the better. The Gryllus dialogue was taken up by another Italian writer, Giovan Battista Gelli, in his ''La Circe'' (1549). This is a series of ten philosophical and moral dialogues between Ulysses and the humans transformed into various animals, ranging from an oyster to an elephant, in which Circe sometimes joins. Most argue against changing back; only the last animal, a philosopher in its former existence, wants to. The work was translated into English soon after in 1557 by Henry Iden. Later the English poet

One of the most enduring literary themes connected with the figure of Circe was her ability to change men into animals. There was much speculation concerning how this could be, whether the human consciousness changed at the same time, and even whether it was a change for the better. The Gryllus dialogue was taken up by another Italian writer, Giovan Battista Gelli, in his ''La Circe'' (1549). This is a series of ten philosophical and moral dialogues between Ulysses and the humans transformed into various animals, ranging from an oyster to an elephant, in which Circe sometimes joins. Most argue against changing back; only the last animal, a philosopher in its former existence, wants to. The work was translated into English soon after in 1557 by Henry Iden. Later the English poet Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; 1552/1553 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognized as one of the premier craftsmen of ...

also made reference to Plutarch's dialogue in the section of his ''Faerie Queene

''The Faerie Queene'' is an English epic poem by Edmund Spenser. Books IIII were first published in 1590, then republished in 1596 together with books IVVI. ''The Faerie Queene'' is notable for its form: at over 36,000 lines and over 4,000 sta ...

'' (1590) based on the Circe episode which appears at the end of Book II. Sir Guyon changes back the victims of Acrasia's erotic frenzy in the Bower of Bliss, most of whom are abashed at their fall from chivalric grace, ''But one above the rest in speciall, / That had an hog beene late, hight Grille by name, / Repined greatly, and did him miscall, / That had from hoggish forme him brought to naturall.''

Two other Italians wrote rather different works that centre on the animal within the human. One was

Two other Italians wrote rather different works that centre on the animal within the human. One was Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli ( , , ; 3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527), occasionally rendered in English as Nicholas Machiavel ( , ; see below), was an Italian diplomat, author, philosopher and historian who lived during the Renaissance. ...

in his unfinished long poem, ''L'asino d'oro'' (''The Golden Ass'', 1516). The author meets a beautiful herdswoman surrounded by Circe's herd of beasts. After spending a night of love with him, she explains the characteristics of the animals in her charge: the lions are the brave, the bears are the violent, the wolves are those forever dissatisfied, and so on (Canto 6). In Canto 7 he is introduced to those who experience frustration: a cat that has allowed its prey to escape; an agitated dragon; a fox constantly on the look-out for traps; a dog that bays the moon; Aesop's lion in love that allowed himself to be deprived of his teeth and claws. There are also emblematic satirical portraits of various Florentine personalities. In the eighth and last canto he has a conversation with a pig that, like the Gryllus of Plutarch, does not want to be changed back and condemns human greed, cruelty and conceit.

The other Italian author was the esoteric philosopher Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno (; ; la, Iordanus Brunus Nolanus; born Filippo Bruno, January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, mathematician, poet, cosmological theorist, and Hermetic occultist. He is known for his cosmologic ...

, who wrote in Latin. His ''Cantus Circaeus'' (''The Incantation of Circe'') was the fourth work on memory and the association of ideas by him to be published in 1582. It contains a series of poetic dialogues, in the first of which, after a long series of incantations to the seven planets of the Hermetic tradition, most humans appear changed into different creatures in the scrying bowl. The sorceress Circe is then asked by her handmaiden Moeris about the type of behaviour with which each is associated. According to Circe, for instance, ''fireflies are the learned, wise, and illustrious amidst idiots, asses, and obscure men'' (Question 32). In later sections different characters discuss the use of images in the imagination in order to facilitate use of the art of memory

The art of memory (Latin: ''ars memoriae'') is any of a number of loosely associated mnemonic principles and techniques used to organize memory impressions, improve recall, and assist in the combination and 'invention' of ideas. An alternative ...

, which is the real aim of the work.

French writers were to take their lead from Gelli in the following century. Antoine Jacob

Antoine Jacob (1639, in Paris – 1685, in Aix), known as Montfleury, was a French actor, playwright and a rival of Molière.

Life and works

Antoine Jacob was the son of Zacharie Jacob, who was the first to adopt Montfleury as a stage name an ...

wrote a one-act social comedy in rhyme, ''Les Bestes raisonnables'' (''The Reasoning Beasts'', 1661) which allowed him to satirise contemporary manners. On the isle of Circe, Ulysses encounters an ass that was once a doctor, a lion that had been a valet, a female doe and a horse, all of whom denounce the decadence of the times. The ass sees human asses everywhere, ''Asses in the town square, asses in the suburbs, / Asses in the provinces, asses proud at court, / Asses browsing in the meadows, military asses trooping, / Asses tripping it at balls, asses in the theatre stalls.'' To drive the point home, in the end it is only the horse, formerly a courtesan, who wants to return to her former state.

The same theme occupies La Fontaine's late fable, "The Companions of Ulysses" (XII.1, 1690), which also echoes Plutarch and Gelli. Once transformed, every animal (which includes a lion, a bear, a wolf and a mole) protests that their lot is better and refuses to be restored to human shape. Charles Dennis shifted this fable to stand at the head of his translation of La Fontaine, ''Select Fables'' (1754), but provides his own conclusion that ''When Mortals from the path of Honour stray, / And the strong passions over reason sway, / What are they then but Brutes? / 'Tis vice alone that constitutes / Th'enchanting wand and magic bowl, The exterior form of Man they wear, / But are in fact both Wolf and Bear, / The transformation's in the Soul.''

The same theme occupies La Fontaine's late fable, "The Companions of Ulysses" (XII.1, 1690), which also echoes Plutarch and Gelli. Once transformed, every animal (which includes a lion, a bear, a wolf and a mole) protests that their lot is better and refuses to be restored to human shape. Charles Dennis shifted this fable to stand at the head of his translation of La Fontaine, ''Select Fables'' (1754), but provides his own conclusion that ''When Mortals from the path of Honour stray, / And the strong passions over reason sway, / What are they then but Brutes? / 'Tis vice alone that constitutes / Th'enchanting wand and magic bowl, The exterior form of Man they wear, / But are in fact both Wolf and Bear, / The transformation's in the Soul.''

Louis Fuzelier Louis Fuzelier (also ''Fuselier'', ''Fusellier'', ''Fusillier'', ''Fuzellier''; 1672 or 1674

and Marc-Antoine Legrand

Marc-Antoine Legrand or Le Grand (30 January 1673, Paris – 7 January 1728) was a 17th–18th-century French actor and playwright.

Biography

The son of a surgeon at the Hôtel des Invalides, Legrand started very early his acting career, first ...

titled their comic opera of 1718 ''Les animaux raisonnables''. It had more or less the same scenario transposed into another medium and set to music by Jacques Aubert

Jacques Aubert (30 September 1689 – 19 May 1753), also known as Jacques Aubert le Vieux (Jacques Aubert the Elder), was a French composer and violinist of the Baroque period. From 1727 to 1746, he was a member of the Vingt-quatre Violons du Ro ...

. Circe, wishing to be rid of the company of Ulysses, agrees to change back his companions, but only the dolphin is willing. The others, who were formerly a corrupt judge (now a wolf), a financier (a pig), an abused wife (a hen), a deceived husband (a bull) and a flibbertigibbet (a linnet), find their present existence more agreeable.

The Venetian

The Venetian Gasparo Gozzi

Gasparo, count Gozzi (4 December 1713 – 26 December 1786) was a Venice, Venetian critic and dramatist.

Life and works

Gasparo Gozzi was the first of eleven children born to the Venetian Count Jacopo Antonio and Angela Tiepolo, who was also of n ...

was another Italian who returned to Gelli for inspiration in the 14 prose ''Dialoghi dell'isola di Circe'' (''Dialogues from Circe's Island'') published as journalistic pieces between 1760 and 1764. In this moral work, the aim of Ulysses in talking to the beasts is to learn more of the human condition. It includes figures from fable ( The fox and the crow, XIII) and from myth to illustrate its vision of society at variance. Far from needing the intervention of Circe, the victims find their natural condition as soon as they set foot on the island. The philosopher here is not Gelli's elephant but the bat that retreats from human contact into the darkness, like Bruno's fireflies (VI). The only one who wishes to change in Gozzi's work is the bear, a satirist who had dared to criticize Circe and had been changed as a punishment (IX).

There were two more satirical dramas in later centuries. One modelled on the Gryllus episode in Plutarch occurs as a chapter of Thomas Love Peacock

Thomas Love Peacock (18 October 1785 – 23 January 1866) was an English novelist, poet, and official of the East India Company. He was a close friend of Percy Bysshe Shelley and they influenced each other's work. Peacock wrote satirical novels, ...

's late novel, ''Gryll Grange

''Gryll Grange'' is the seventh and final novel of Thomas Love Peacock, published in 1861.

Overview

The novel first appeared in ''Fraser's Magazine'' in 1860, showing a remarkable instance of vigour after his retirement from the East India Comp ...

'' (1861), under the title "Aristophanes in London". Half Greek comedy, half Elizabethan masque, it is acted at the Grange by the novel's characters as a Christmas entertainment. In it Spiritualist

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century

The ''long nineteenth century'' i ...

mediums

Mediumship is the practice of purportedly mediating communication between familiar spirits or spirits of the dead and living human beings. Practitioners are known as "mediums" or "spirit mediums". There are different types of mediumship or spir ...

raise Circe and Gryllus and try to convince the latter of the superiority of modern times, which he rejects as intellectually and materially regressive. An Italian work drawing on the transformation theme was the comedy by Ettore Romagnoli, ''La figlia del Sole'' (''The Daughter of the Sun'', 1919). Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Gr ...

arrives on the island of Circe with his servant Cercopo and has to be rescued by the latter when he too is changed into a pig. But, since the naturally innocent other animals had become corrupted by imitating human vices, the others who had been changed were refused when they begged to be rescued.

Also in England, Austin Dobson engaged more seriously with Homer's account of the transformation of Odysseus' companions when, though ''Head, face and members bristle into swine, / Still cursed with sense, their mind remains alone''. Dobson's " The Prayer of the Swine to Circe" (1640) depicts the horror of being imprisoned in an animal body in this way with the human consciousness unchanged. There appears to be no relief, for only in the final line is it revealed that Odysseus has arrived to free them. But in Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the celebrated headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold, lite ...

's dramatic poem "The Strayed Reveller" (1849), in which Circe is one of the characters, the power of her potion is differently interpreted. The inner tendencies unlocked by it are not the choice between animal nature and reason but between two types of impersonality, between divine clarity and the poet's participatory and tragic vision of life. In the poem, Circe discovers a youth laid asleep in the portico of her temple by a draught of her ivy-wreathed bowl. On awaking from possession by the poetic frenzy it has induced, he craves for it to be continued.

Sexual politics

With theRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

there began to be a reinterpretation of what it was that changed the men, if it was not simply magic. For Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

, in Classical times, it had been gluttony overcoming their self-control. But for the influential emblematist Andrea Alciato

Andrea Alciato (8 May 149212 January 1550), commonly known as Alciati (Andreas Alciatus), was an Italian jurist and writer. He is regarded as the founder of the French school of legal humanists.

Biography

Alciati was born in Alzate Brianza, nea ...

, it was unchastity. In the second edition of his ''Emblemata'' (1546), therefore, Circe became the type of the prostitute

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

. His Emblem 76 is titled ''Cavendum a meretricibus''; its accompanying Latin verses mention Picus, Scylla and the companions of Ulysses, and concludes that 'Circe with her famous name indicates a whore and any who loves such a one loses his reason'. His English imitator Geoffrey Whitney

Geoffrey (then spelt Geffrey) Whitney (c. 1548 – c. 1601) was an English poet, now best known for the influence on Elizabethan writing of the ''Choice of Emblemes'' that he compiled.

Life

Geoffrey Whitney, the eldest son of a father of the sa ...

used a variation of Alciato's illustration in his own ''Choice of Emblemes'' (1586) but gave it the new title of ''Homines voluptatibus transformantur'', men are transformed by their passions. This explains her appearance in the Nighttown section named after her in James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

's novel ''Ulysses

Ulysses is one form of the Roman name for Odysseus, a hero in ancient Greek literature.

Ulysses may also refer to:

People

* Ulysses (given name), including a list of people with this name

Places in the United States

* Ulysses, Kansas

* Ulysse ...

''. Written in the form of a stage script, it makes of Circe the brothel madam, Bella Cohen. Bloom, the book's protagonist, fantasizes that she turns into a cruel man-tamer named Mr Bello who makes him get down on all fours and rides him like a horse.

By the 19th century, Circe was ceasing to be a mythical figure. Poets treated her either as an individual or at least as the type of a certain kind of woman. The French poet Albert Glatigny

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert (supermarket), a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street market in The Gambia

* Albert Productions, a record label

* Albert ...

addresses "Circé" in his ''Les vignes folles'' (1857) and makes of her a voluptuous opium dream, the magnet of masochistic fantasies. Louis-Nicolas Ménard's sonnet in ''Rêveries d'un païen mystique'' (1876) describes her as enchanting all with her virginal look, but appearance belies the accursed reality. Poets in English were not far behind in this lurid portrayal. Lord de Tabley's "Circe" (1895) is a thing of decadent perversity likened to a tulip, ''A flaunting bloom, naked and undivine... / With freckled cheeks and splotch'd side serpentine, / A gipsy among flowers''.

That central image is echoed by the blood-striped flower of T.S.Eliot's student poem "Circe's Palace" (1909) in the

That central image is echoed by the blood-striped flower of T.S.Eliot's student poem "Circe's Palace" (1909) in the Harvard Advocate

''The Harvard Advocate'', the art and literary magazine of Harvard College, is the oldest continuously published college art and literary magazine in the United States. The magazine (published then in newspaper format) was founded by Charles S. ...

. Circe herself does not appear, her character is suggested by what is in the grounds and the beasts in the forest beyond: panthers, pythons, and peacocks that ''look at us with the eyes of men whom we knew long ago''. Rather than a temptress, she has become an emasculatory threat.

Several female poets make Circe stand up for herself, using the soliloquy form to voice the woman's position. The 19th-century English poet Augusta Webster

Augusta Webster (30 January 1837 – 5 September 1894) born in Poole, Dorset as Julia Augusta Davies, was an England, English poet, dramatist, essayist, and translation, translator.

Biography

Augusta was the daughter of Vice-admiral George Dav ...

, much of whose writing explored the female condition, has a dramatic monologue in blank verse titled "Circe" in her volume ''Portraits'' (1870). There the sorceress anticipates her meeting with Ulysses and his men and insists that she does not turn men into pigs—she merely takes away the disguise that makes them seem human. ''But any draught, pure water, natural wine, / out of my cup, revealed them to themselves / and to each other. Change? there was no change; / only disguise gone from them unawares''. The mythological character of the speaker contributes at a safe remove to the Victorian discourse on women's sexuality by expressing female desire and criticizing the subordinate role given to women in heterosexual politics.

Two American poets also explored feminine psychology in poems ostensibly about the enchantress. Leigh Gordon Giltner's "Circe" was included in her collection ''The Path of Dreams'' (1900), the first stanza of which relates the usual story of men turned into swine by her spell. But then a second stanza presents a sensuous portrait of an unnamed woman, very much in the French vein; once more, it concludes, 'A Circe's spells transform men into swine'. This is no passive victim of male projections but a woman conscious of her sexual power. So too is Hilda Doolittle

Hilda Doolittle (September 10, 1886 – September 27, 1961) was an American modernist poet, novelist, and memoirist who wrote under the name H.D. throughout her life. Her career began in 1911 after she moved to London and co-founded the ...

's "Circe", from her collection ''Hymen'' (1921). In her soliloquy she reviews the conquests with which she has grown bored, then mourns the one instance when she failed. In not naming Ulysses himself, Doolittle universalises an emotion with which all women might identify. At the end of the century, British poet Carol Ann Duffy

Dame Carol Ann Duffy (born 23 December 1955) is a Scottish poet and playwright. She is a professor of contemporary poetry at Manchester Metropolitan University, and was appointed Poet Laureate in May 2009, resigning in 2019. She was the first ...

wrote a monologue entitled ''Circe'' which pictures the goddess addressing an audience of 'nereids and nymphs'. In this outspoken episode in the war between the sexes, Circe describes the various ways in which all parts of a pig could and should be cooked.

Another indication of the progression in interpreting the Circe figure is given by two poems a century apart, both of which engage with paintings of her. The first is the sonnet that Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (), was an English poet, illustrator, painter, translator and member of the Rossetti family. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhoo ...

wrote in response to Edward Burne-Jones

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet, (; 28 August, 183317 June, 1898) was a British painter and designer associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood which included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Millais, Ford Madox Brown and Holman Hun ...

' "The Wine of Circe" in his volume ''Poems'' (1870). It gives a faithful depiction of the painting's Pre-Raphaelite

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, James ...

mannerism but its description of Circe's potion as 'distilled of death and shame' also accords with the contemporary (male) identification of Circe with perversity. This is further underlined by his statement (in a letter) that the black panthers there are 'images of ruined passion' and by his anticipation at the end of the poem of ''passion's tide-strown shore / Where the disheveled seaweed hates the sea''. The Australian A. D. Hope

Alec Derwent Hope (21 July 190713 July 2000) was an Australian poet and essayist known for his satirical slant. He was also a critic, teacher and academic. He was referred to in an American journal as "the 20th century's greatest 18th-centur ...

's "Circe – after the painting by Dosso Dossi", on the other hand, frankly admits humanity's animal inheritance as natural and something in which even Circe shares. In the poem, he links the fading rationality and speech of her lovers to her own animal cries in the act of love.

There remain some poems that bear her name that have more to do with their writers' private preoccupations than with reinterpreting her myth. The link with it in

There remain some poems that bear her name that have more to do with their writers' private preoccupations than with reinterpreting her myth. The link with it in Margaret Atwood

Margaret Eleanor Atwood (born November 18, 1939) is a Canadian poet, novelist, literary critic, essayist, teacher, environmental activist, and inventor. Since 1961, she has published 18 books of poetry, 18 novels, 11 books of non-fiction, nin ...

's "Circe/Mud Poems", first published in ''You Are Happy'' (1974), is more a matter of allusion and is nowhere overtly stated beyond the title. It is a reflection on contemporary gender politics that scarcely needs the disguises of Augusta Webster's. With two other poems by male writers it is much the same: Louis Macneice

Frederick Louis MacNeice (12 September 1907 – 3 September 1963) was an Irish poet and playwright, and a member of the Auden Group, which also included W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis. MacNeice's body of work was widely a ...

's, for example, whose "Circe" appeared in his first volume, ''Poems'' (London, 1935); or Robert Lowell

Robert Traill Spence Lowell IV (; March 1, 1917 – September 12, 1977) was an American poet. He was born into a Boston Brahmin family that could trace its origins back to the ''Mayflower''. His family, past and present, were important subjects i ...

's, whose "Ulysses and Circe" appeared in his last, ''Day by Day'' (New York, 1977). Both poets have appropriated the myth to make a personal statement about their broken relationships.

Parallels and sequels

Several Renaissance epics of the 16th century include lascivious sorceresses based on the Circe figure. These generally live in an isolated spot devoted to pleasure, to which lovers are lured and later changed into beasts. They include the following: * Alcina in the ''Orlando Furioso

''Orlando furioso'' (; ''The Frenzy of Orlando'', more loosely ''Raging Roland'') is an Italian epic poem by Ludovico Ariosto which has exerted a wide influence on later culture. The earliest version appeared in 1516, although the poem was no ...

'' (''Mad Roland,'' 1516, 1532) of Ludovico Ariosto

Ludovico Ariosto (; 8 September 1474 – 6 July 1533) was an Italian poet. He is best known as the author of the romance epic ''Orlando Furioso'' (1516). The poem, a continuation of Matteo Maria Boiardo's ''Orlando Innamorato'', describes the ...

, set at the time of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

. Among its many sub-plots is the episode in which the Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

champion Ruggiero is taken captive by the sorceress and has to be freed from her magic island.

* The lovers of Filidia in ''Il Tancredi'' (1632) by Ascanio Grandi (1567–1647) have been changed into monsters and are liberated by the virtuous Tancred.

* Armida

Armida is the fictional character of a Saracen sorceress, created by the Italian late Renaissance poet Torquato Tasso. Description

In Tasso's epic ''Jerusalem Delivered'' ( it, Gerusalemme liberata, link=no), Rinaldo is a fierce and determ ...

in Torquato Tasso

Torquato Tasso ( , also , ; 11 March 154425 April 1595) was an Italian poet of the 16th century, known for his 1591 poem ''Gerusalemme liberata'' (Jerusalem Delivered), in which he depicts a highly imaginative version of the combats between ...

's ''La Gerusalemme liberata'' (''Jerusalem Delivered

''Jerusalem Delivered'', also known as ''The Liberation of Jerusalem'' ( it, La Gerusalemme liberata ; ), is an epic poem by the Italian poet Torquato Tasso, first published in 1581, that tells a largely mythified version of the First Crusade i ...

'', 1566–1575, published 1580) is a Saracen sorceress sent by the infernal senate to sow discord among the Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

camped before Jerusalem, where she succeeds in changing a party of them into animals. Planning to assassinate the hero, Rinaldo, she falls in love with him instead and creates an enchanted garden where she holds him a lovesick prisoner who has forgotten his former identity.

* Acrasia in Edmund Spenser's ''Faerie Queene'', mentioned above, is a seductress of knights and holds them enchanted in her Bower of Bliss.