The Choctaw Nation (

Choctaw: ''Chahta Okla'') is a

Native American territory covering about , occupying portions of southeastern

Oklahoma in the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

. The Choctaw Nation is the third-largest

federally recognized tribe in the United States and the second-largest

Indian reservation in area after the

Navajo. As of 2011, the tribe has 223,279 enrolled members, of whom 84,670 live within the state of

Oklahoma and 41,616 live within the Choctaw Nation's jurisdiction. A total of 233,126 people live within these boundaries, with its

tribal jurisdictional area

Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area is a statistical entity identified and delineated by federally recognized American Indian tribes in Oklahoma as part of the U.S. Census Bureau's 2010 Census and ongoing American Community Survey.

Many of these ...

comprising 10.5 counties in the state, with the seat of government being located in

Durant, Oklahoma. It shares borders with the reservations of the

Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

,

Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands[Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...]

, as well as the U.S. states of

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

and

Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

. By area, the Choctaw Nation is larger than eight

U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

s.

The chief of the Choctaw Nation is

Gary Batton

Gary Dale Batton (born December 15, 1966) is a tribal administrator and politician, the current and 47th Chief of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. It is the third-largest federally recognized tribe and second-largest reservation in total area.

Bat ...

, who took office on April 29, 2014, after the retirement of

Gregory E. Pyle.

The Choctaw Nation Headquarters, which houses the office of the Chief, is located in

Durant.

[ Durant is also the seat of the tribe's judicial department, housed in the Choctaw Nation Judicial Center, near the Headquarters. The tribal legislature meets at the Council House, across the street from the historic ]Choctaw Capitol Building

The Choctaw Capitol Building ( cho, Chuka Hanta Chahta) is a historic building built in 1884 that housed the government of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma from 1884 to 1907. The building is located in Pushmataha County, Oklahoma, two miles north ...

, in Tuskahoma. The Capitol Building has been adapted for use as the Choctaw Nation Museum. The largest city in the nation had long been McAlester but was recently surpassed by Durant at the 2020 United States census

The United States census of 2020 was the twenty-fourth decennial United States census. Census Day, the reference day used for the census, was April 1, 2020. Other than a pilot study during the 2000 census, this was the first U.S. census to of ...

.

The Choctaw Nation is one of three federally recognized Choctaw tribes; the others are the sizable Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians ( cho, Mississippi Chahta) is one of three federally recognized tribes of Choctaw Native Americans, and the only one in the state of Mississippi. On April 20, 1945, this tribe organized under the Indian R ...

, with 10,000 members and territory in several communities, and the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians

The Jena Band of Choctaw Indians ( cho, Jena Chahta) are one of three federally recognized Choctaw tribes in the United States. They are based in La Salle, Catahoula, and Grant parishes in the U.S. state of Louisiana. The Jena Band received fe ...

in Louisiana, with a few hundred members. The latter two bands are descendants of Choctaw who resisted the forced relocation

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

. The Mississippi Choctaw preserved much of their culture in small communities and reorganized as a tribal government in 1945 under new laws after the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934

The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of June 18, 1934, or the Wheeler–Howard Act, was U.S. federal legislation that dealt with the status of American Indians in the United States. It was the centerpiece of what has been often called the "Indian ...

.

Those Choctaw who removed to the Indian Territory, a process that went on into the early 20th century, are federally recognized as the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.[

] The removals became known as the "Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

."

The original territory has expanded and shrunk several times since the 19th century.

Terminology

In English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, the official name for the area was "Choctaw Nation", as outlined in Article III of the 1866 Reconstruction Treaty following the Civil War. During its time of sovereignty within the United States Indian Territory, it also utilized the title "Choctaw Republic".[

] Since 1971, it is officially referred to as the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. The Choctaw Nation maintains a special relationship with both the federal

Federal or foederal (archaic) may refer to:

Politics

General

*Federal monarchy, a federation of monarchies

*Federation, or ''Federal state'' (federal system), a type of government characterized by both a central (federal) government and states or ...

and Oklahoma governments.

Officially a domestic dependent nation

Tribal sovereignty in the United States is the concept of the inherent authority of indigenous tribes to govern themselves within the borders of the United States.

Originally, the U.S. federal government recognized American Indian trib ...

since 1971, in July 2020, the Supreme Court ruled in '' McGirt v. Oklahoma'' that the eastern area of Oklahoma- about half of the modern state- never lost its status as a Native reservation. This includes the city of Tulsa

Tulsa () is the second-largest city in the state of Oklahoma and 47th-most populous city in the United States. The population was 413,066 as of the 2020 census. It is the principal municipality of the Tulsa Metropolitan Area, a region with ...

(located between Muscogee and Cherokee territory). The area includes lands of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Muscogee and Seminole. Among other effects, the decision potentially overturns convictions of over a thousand cases in the area involving tribe members convicted under state laws. The ruling is based on an 1832 treaty, which the court ruled was still in force, adding that "Because Congress has not said otherwise, we hold the government to its word." As such, the Choctaw Nation returned from a ''domestic dependent nation'' status to that of an Indian reservation.

Geography

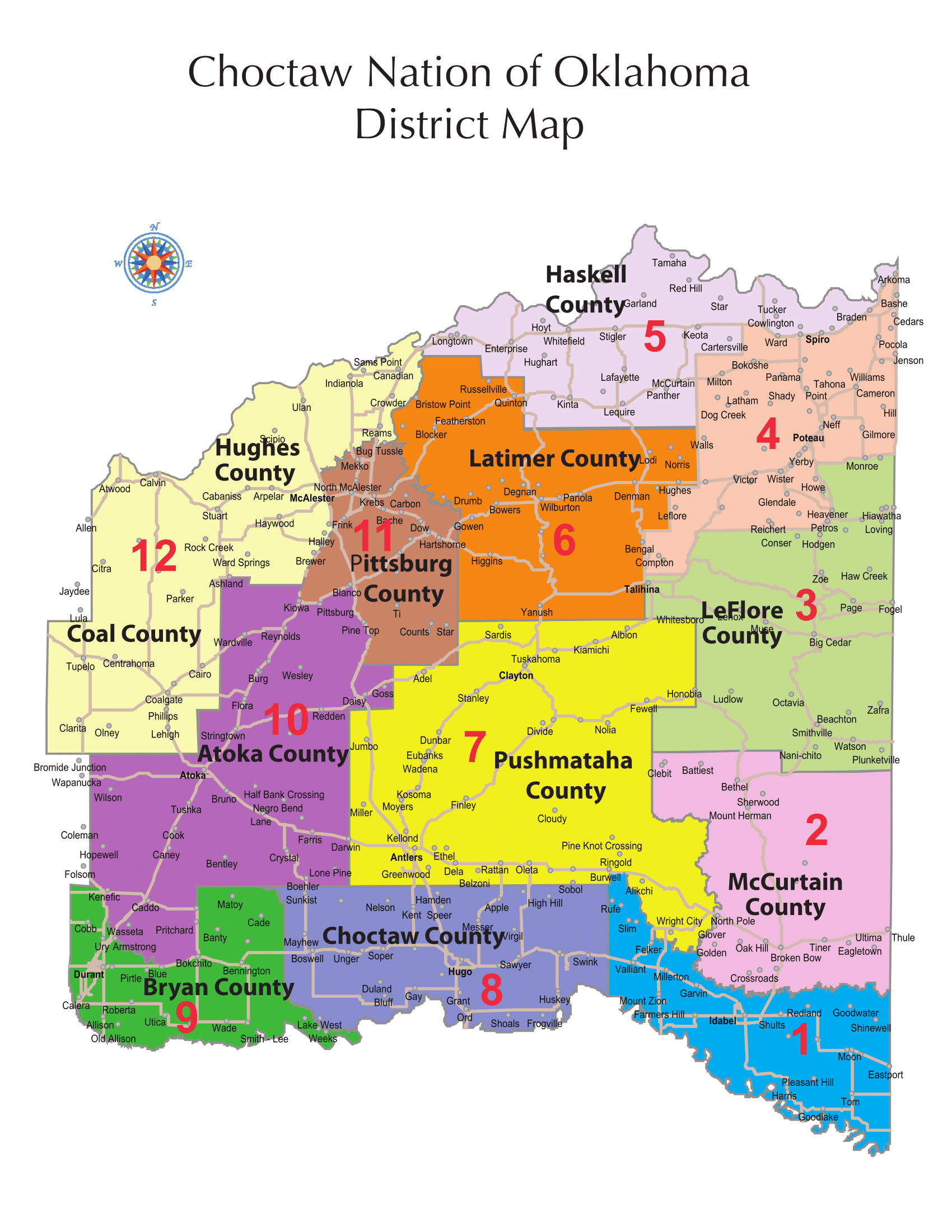

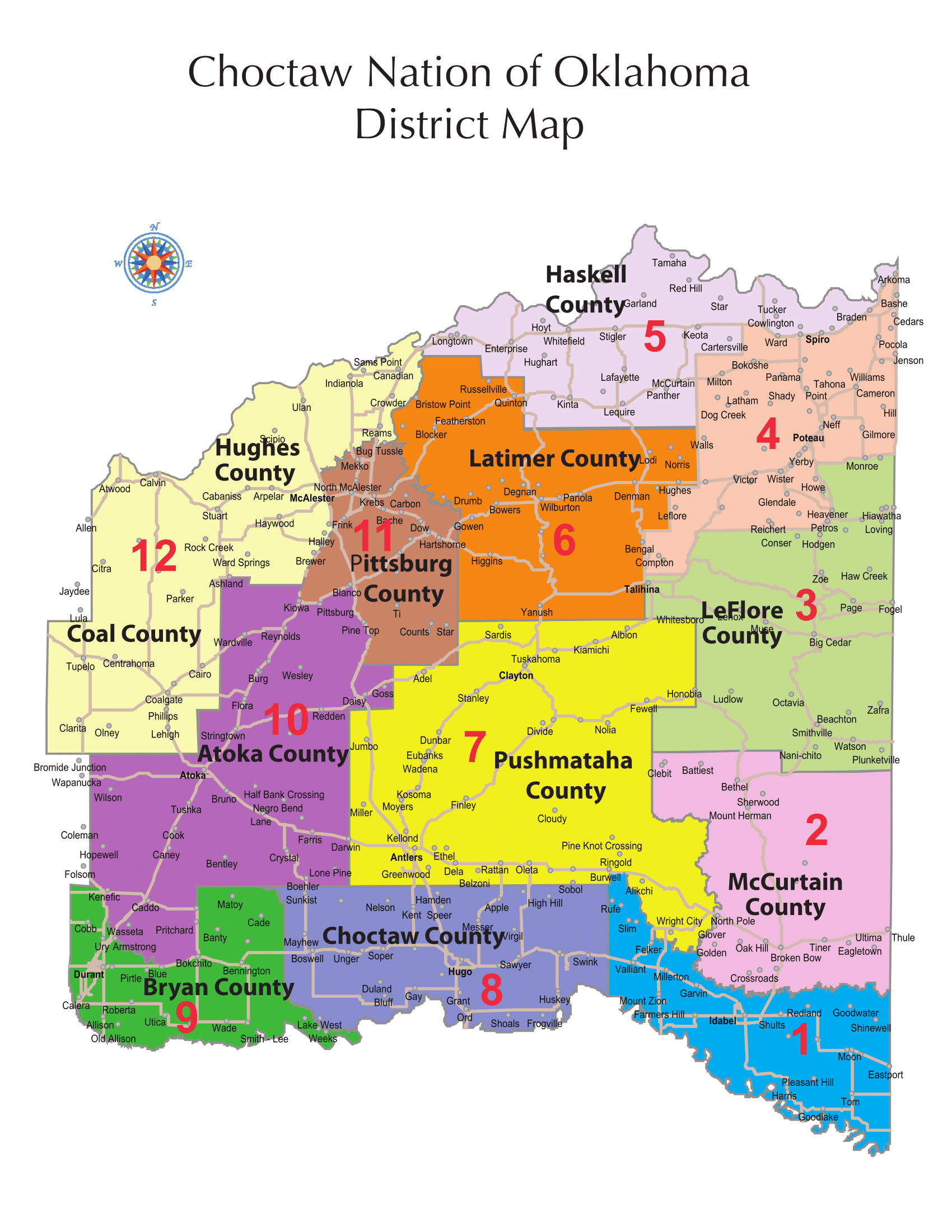

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma's reservation covers , encompassing eight whole counties and parts of five counties in

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma's reservation covers , encompassing eight whole counties and parts of five counties in Southeastern Oklahoma

Choctaw Country is the Oklahoma Department of Tourism and Recreation's official tourism designation for Southeastern Oklahoma. The name was previously Kiamichi Country until changed in honor of the Choctaw Nation headquartered there. The curren ...

:

*Atoka County

Atoka County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2010 census, the population was 14,007. Its county seat is Atoka. The county was formed before statehood from Choctaw Lands, and its name honors a Choctaw Chief named ...

,

*most of Bryan County,

* Choctaw County,

*most of Coal County,

* Haskell County,

*half of Hughes County,

*a portion of Johnston County,

* Latimer County,

*Le Flore County

LeFlore County is a county along the eastern border of the U.S state of Oklahoma. As of the 2010 census, the population was 50,384. Its county seat is Poteau. The county is part of the Fort Smith metropolitan area and the name honors a Choct ...

,

*McCurtain County

McCurtain County is in the southeastern corner of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2010 census, the population was 33,151. Its county seat is Idabel. It was formed at statehood from part of the earlier Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory ...

,

* Pittsburg County,

*a portion of Pontotoc County, and

* Pushmataha County.

Government

The Tribal Headquarters are located in Durant. Opened in June 2018, the new headquarters is a 5-story, 500,000 square foot building located on an 80-acre campus in south Durant. It is near other tribal buildings, such as the Regional Health Clinic, Wellness Center, Community Center, Child Development Center, and Food Distribution. Previously, headquarters was located in the former Oklahoma Presbyterian College, with more offices scattered around Durant. The current chief is Gary Batton

Gary Dale Batton (born December 15, 1966) is a tribal administrator and politician, the current and 47th Chief of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. It is the third-largest federally recognized tribe and second-largest reservation in total area.

Bat ...

Dawes Rolls

The Dawes Rolls (or Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes, or Dawes Commission of Final Rolls) were created by the United States Dawes Commission. The commission was authorized by United States Congress in 1893 to exe ...

. Also, because the Nation, along with the other Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek ...

, supported the Confederacy during the U.S. Civil War, they severed ties with the federal government, making the U.S. require these tribes to make new peace treaties, emancipate their slaves, and offer full citizenship. Numerous families had intermarried by that time or had other personal ties to the tribe as well, but the Choctaw Nation did not uphold the Treaty of 1866.Oklahoma's 2nd congressional district

Oklahoma's 2nd congressional district is one of five United States congressional districts in Oklahoma and covers approximately one-fourth of the state in the east. The district borders Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, and Texas and includes (in who ...

, represented by Republican Markwayne Mullin

Mark Wayne "Markwayne" Mullin (born July 26, 1977) is an American businessman, former professional mixed martial arts fighter, and politician serving as the junior United States senator from Oklahoma since 2023. A member of the Republican Party ...

, a Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

. However some smaller strands are located within the 4th congressional district, represented by Republican Tom Cole

Thomas Jeffery Cole (born April 28, 1949) is the U.S. representative for , serving since 2003. He is a member of the Republican Party and serves as Deputy Minority Whip. The chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC) fr ...

, a Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

. With a majority of both Native American and white voters in the region leaning conservative, Republican Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

carried every county in the Choctaw Nation in the 2020 election, as well as every county in the state of Oklahoma, continuing a trend seen in the 2004, 2008

File:2008 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Lehman Brothers went bankrupt following the Subprime mortgage crisis; Cyclone Nargis killed more than 138,000 in Myanmar; A scene from the opening ceremony of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing; ...

, 2012

File:2012 Events Collage V3.png, From left, clockwise: The passenger cruise ship Costa Concordia lies capsized after the Costa Concordia disaster; Damage to Casino Pier in Seaside Heights, New Jersey as a result of Hurricane Sandy; People gat ...

and 2016

File:2016 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: Bombed-out buildings in Ankara following the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt; the Impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, impeachment trial of Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff; Damaged houses duri ...

elections. The Choctaw Nation is located in one of the most conservative areas of Oklahoma, and while registered Democrats outnumber Republicans, the region has consistently gone to Republican candidates.

The current head of the government, Chief Gary Batton

Gary Dale Batton (born December 15, 1966) is a tribal administrator and politician, the current and 47th Chief of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. It is the third-largest federally recognized tribe and second-largest reservation in total area.

Bat ...

, is a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

. The Chief that preceded him, Gregory Pyle

Gregory Eli Pyle (April 25, 1949 – October 26, 2019) was an American politician who was a long-term political leader of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. He was elected as Principal Chief in 1997 and re-elected since by wide margins, reigning for ...

, was a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

.

The Choctaw Nation also has the right to appoint a non-voting delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

, per the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was a treaty which was signed on September 27, 1830, and proclaimed on February 24, 1831, between the Choctaw American Indian tribe and the United States Government. This treaty was the first removal treaty wh ...

; as of 2020 however, no delegate has been named or sent to the Congress by the Choctaw Nation. Chief Gary Batton is said to be observing the process of the Cherokee Nation nominating their treaty-stipulated delegate to the U.S. House before proceeding.

Executive Department

The supreme executive power of the Choctaw Nation is assigned to a chief magistrate, styled as the "Chief of the Choctaw Nation". The Assistant Chief is appointed by the Chief with the advice and consent of the Tribal Council, and can be removed at the discretion of the Chief. The current Chief of the Choctaw Nation is Gary Batton

Gary Dale Batton (born December 15, 1966) is a tribal administrator and politician, the current and 47th Chief of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. It is the third-largest federally recognized tribe and second-largest reservation in total area.

Bat ...

, and the current Assistant Chief is Jack Austin, Jr.

The Chief's birthday (Batton's is December 15) is a tribal holiday.

In 2021, the tribal council instituted October 16 as ''Choctaw Flag Day'', a holiday to celebrate the adoption of the Choctaw Nation Seal on October 16, 1860.

History

Before Oklahoma was admitted to the union as a state in 1907, the Choctaw Nation was divided into three districts: Apukshunnubbee, Moshulatubbee, and Pushmataha

Pushmataha (c. 1764 – December 24, 1824; also spelled Pooshawattaha, Pooshamallaha, or Poosha Matthaw), the "Indian General", was one of the three regional chiefs of the major divisions of the Choctaw in the 19th century. Many historians cons ...

. Each district had its own chief from 1834 to 1857; afterward, the three districts were put under the jurisdiction of one chief. The three districts were re-established in 1860, again each with their own chief, with a fourth chief to be Principal Chief of the tribe. These districts were abolished at the time of statehood, as tribal government and land claims were dissolved in order for the territory to be admitted as a state. The tribe later reorganized to re-establish its government.

List of Chiefs

Legislative department

The legislative authority is vested in the Tribal Council. Members of the Tribal Council are elected by the Choctaw people, one for each of the twelve districts in the Choctaw Nation.

The Tribal council members are the voice and representation of the Choctaw people in the tribal government. In order to be elected as council members, candidates must have resided in their respective districts for at least one year immediately preceding the election and must be at least one-fourth Choctaw Indian by blood and at least twenty-one years of age. Once elected, council members must remain a resident of their district during the term in office.

Once in office, the Tribal council members have regularly scheduled county council meetings. The presence of these tribal leaders in the Indian community creates a sense of understanding of their community and its needs. The Tribal Council is responsible for adopting rules and regulations which govern the Choctaw Nation, for approving all budgets, decisions concerning the management of tribal property, and all other legislative matters. The Tribal Council assists the community to implement an economic development strategy and to plan, organize, and direct Tribal resources to achieve self-sufficiency.

The Tribal council members are the voice and representation of the Choctaw people in the tribal government. In order to be elected as council members, candidates must have resided in their respective districts for at least one year immediately preceding the election and must be at least one-fourth Choctaw Indian by blood and at least twenty-one years of age. Once elected, council members must remain a resident of their district during the term in office.

Once in office, the Tribal council members have regularly scheduled county council meetings. The presence of these tribal leaders in the Indian community creates a sense of understanding of their community and its needs. The Tribal Council is responsible for adopting rules and regulations which govern the Choctaw Nation, for approving all budgets, decisions concerning the management of tribal property, and all other legislative matters. The Tribal Council assists the community to implement an economic development strategy and to plan, organize, and direct Tribal resources to achieve self-sufficiency.

Judicial department

The judicial authority of the Choctaw Nation is assigned to the Court of General Jurisdiction (which includes the District Court and the Appellate Division) and the Constitutional Court. The Constitutional Court consists of a three-member court, who are appointed by the Chief. At least one member, the presiding judge (Chief Justice), must be a lawyer licensed to practice before the Supreme Court of Oklahoma.

Members

*Constitutional Court

**Chief Justice David Burrage

**Judge Mitch Mullin

**Judge Frederick Bobb

*Appellate Division

**Presiding Judge Pat Phelps

**Judge Bob Rabon

**Judge Warren Gotcher

*District Court

**Presiding District Judge Richard Branam

**District Judge Mark Morrison

**District Judge Rebecca Cryer

Government Treaties

The Choctaw underwent many changes to their government since its first interactions with the United States. The Choctaw Nation acknowledges these treaties and categorizes them by “Pre-Removal Treaties” and “Post-Removal Treaties”.

Economy

The Choctaw Nation's annual tribal economic impact in 2010 was over $822,280,105. The tribe employs nearly 8,500 people worldwide; 2,000 of those work in Bryan County, Oklahoma. The Choctaw Nation is also the largest single employer in Durant. The nation's payroll is about $260 million per year, with total revenues from tribal businesses and governmental entities topping $1 billion.

The nation has contributed to raising Bryan County's per capita income

Per capita income (PCI) or total income measures the average income earned per person in a given area (city, region, country, etc.) in a specified year. It is calculated by dividing the area's total income by its total population.

Per capita i ...

to about $24,000. The Choctaw Nation has helped build water system

A water supply network or water supply system is a system of engineered hydrologic and hydraulic components that provide water supply. A water supply system typically includes the following:

# A drainage basin (see water purification – source ...

s and towers

A tower is a tall structure, taller than it is wide, often by a significant factor. Towers are distinguished from masts by their lack of guy-wires and are therefore, along with tall buildings, self-supporting structures.

Towers are specific ...

, roads and other infrastructure, and has contributed to additional fire station

__NOTOC__

A fire station (also called a fire house, fire hall, firemen's hall, or engine house) is a structure or other area for storing firefighting apparatuses such as fire engines and related vehicles, personal protective equipment, fire ...

s, EMS units and law enforcement

Law enforcement is the activity of some members of government who act in an organized manner to enforce the law by discovering, deterring, rehabilitating, or punishing people who violate the rules

Rule or ruling may refer to:

Education ...

needs that have accompanied economic growth.

The Choctaw Nation operates several types of businesses. It has seven casino

A casino is a facility for certain types of gambling. Casinos are often built near or combined with hotels, resorts, restaurants, retail shopping, cruise ships, and other tourist attractions. Some casinos are also known for hosting live entertai ...

s, 14 tribal smoke shops, 13 truck stops, and two Chili's

Chili's Grill & Bar is an American casual dining restaurant chain. The company was founded by Larry Lavine in Texas in 1975 and is currently owned and operated by Brinker International.

History

Chili's first location, a converted postal statio ...

franchises in Atoka and Poteau.[ It also owns a printing operation, a corporate drug testing service, ]hospice care

Hospice care is a type of health care that focuses on the palliation of a terminally ill patient's pain and symptoms and attending to their emotional and spiritual needs at the end of life. Hospice care prioritizes comfort and quality of life by ...

, a metal fabrication

Metal fabrication is the creation of metal structures by cutting, bending and assembling processes. It is a value-added process involving the creation of machines, parts, and structures from various raw materials.

Typically, a fabrication sh ...

and manufacturing

Manufacturing is the creation or production of goods with the help of equipment, labor, machines, tools, and chemical or biological processing or formulation. It is the essence of secondary sector of the economy. The term may refer to ...

business, a document backup and archiving business, and a management services company that provides staffing at military bases

A military base is a facility directly owned and operated by or for the military or one of its branches that shelters military equipment and personnel, and facilitates training and Military operation, operations. A military base always provides ...

, embassies

A diplomatic mission or foreign mission is a group of people from a state or organization present in another state to represent the sending state or organization officially in the receiving or host state. In practice, the phrase usually deno ...

and other sites, among other enterprises.

Health system

The Choctaw Nation is the first indigenous tribe in the United States to build its own hospital with its own funding. The Choctaw Nation Health Care Center, located in Talihina, is a health facility with 37 hospital beds for inpatient care and 52 exam rooms. The $22 million hospital is complete with $6 million worth of state-of-the-art equipment and furnishing. It serves 150,000–210,000 outpatient visits annually. The hospital also houses the Choctaw Nation Health Services Authority, the hub of the tribal health care services of

The Choctaw Nation is the first indigenous tribe in the United States to build its own hospital with its own funding. The Choctaw Nation Health Care Center, located in Talihina, is a health facility with 37 hospital beds for inpatient care and 52 exam rooms. The $22 million hospital is complete with $6 million worth of state-of-the-art equipment and furnishing. It serves 150,000–210,000 outpatient visits annually. The hospital also houses the Choctaw Nation Health Services Authority, the hub of the tribal health care services of Southeastern Oklahoma

Choctaw Country is the Oklahoma Department of Tourism and Recreation's official tourism designation for Southeastern Oklahoma. The name was previously Kiamichi Country until changed in honor of the Choctaw Nation headquartered there. The curren ...

.

The tribe also operates eight Indian clinics, one each in Atoka, Broken Bow, Durant, Hugo

Hugo or HUGO may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Hugo'' (film), a 2011 film directed by Martin Scorsese

* Hugo Award, a science fiction and fantasy award named after Hugo Gernsback

* Hugo (franchise), a children's media franchise based on ...

, Idabel

Idabel is a city in and county seat of McCurtain County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 7,010 at the 2010 census. It is located in the southeast corner of Oklahoma, a tourist area known as Choctaw Country.

History

Idabel was est ...

, McAlester, Poteau, and Stigler Stigler is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Franz Stigler (1915–2008), Luftwaffe pilot who escorted an American bomber back to safety in 1943

* George Stigler (1911–1991), Nobel Prize–winning U.S. economist, associated w ...

.

2008 Secretary of Defense Employer Support Freedom Award

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma has participated in a great deal of help for those outside of their nation. In fact, they took part in helping United States troops overseas. They did this by putting together care packages. Their total of packages sent out were close to 3,500. These packages were sent to troops throughout Iraq and Afghanistan.

The United States Department of Defense has an award called the Secretary of Defense Employer Support Freedom Award. This award is the highest recognition given by the U.S. Government to employers for their outstanding support of employees who serve in the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

and Reserve

Reserve or reserves may refer to:

Places

* Reserve, Kansas, a US city

* Reserve, Louisiana, a census-designated place in St. John the Baptist Parish

* Reserve, Montana, a census-designated place in Sheridan County

* Reserve, New Mexico, a US vi ...

. The executive Director of the National Committee for Employer Support of the Guard and Reserve, Dr. L. Gordon Sumner Jr., said, "We are pleased and excited to announce Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma as a recipient of the 2008 Secretary of Defense Employer Support Freedom Award. The tremendous support Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma provides for Guard and Reserve employees and their families is exemplary and helps our citizen warriors protect our nation without concern for their jobs."

The Choctaw Nation was one of 15 recipients of that year's Freedom Award, selected from 2,199 nominations. Its representatives received the award September 18, 2008 in Washington, D.C. They received the award based on their large employer status with the National Guard and Reserves. The Choctaw Nation is the first Native American tribe to receive this award.

“Oklahomans who serve our country do so at tremendous personal expense and risk. The Choctaw Nation has gone above and beyond to support those men and women,” said Sen. Jay Paul Gumm. “They are a shining example of how employers and communities can go that extra mile for our military personnel.”

History

Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830)

The Choctaw were recognized as a sovereign nation under the protection of the United States with the

The Choctaw were recognized as a sovereign nation under the protection of the United States with the Treaty of Hopewell

Three agreements, each known as the Treaty of Hopewell, were signed between representatives of the Congress of the United States and the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw peoples, were negotiated and signed at the Hopewell plantation in South Car ...

in 1786. They were militarily aligned with the United States during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, Northwest Indian War, Creek Civil War

The Creek War (1813–1814), also known as the Red Stick War and the Creek Civil War, was a regional war between opposing Indigenous American Creek factions, European empires and the United States, taking place largely in modern-day Alabama ...

, and the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

. However, relations soured following the election of Andrew Jackson. At Jackson's personal request, the United States Congress opened a fierce debate on an Indian Removal Bill.[

] In the end, the bill passed, but the vote was very close: The Senate passed the measure, 28 to 19, while in the House it passed, 102 to 97. Jackson signed the legislation into law June 30, 1830,Franklin, Tennessee

Franklin is a city in and county seat of Williamson County, Tennessee, United States. About south of Nashville, it is one of the principal cities of the Nashville metropolitan area and Middle Tennessee. As of 2020, its population was 83,454 ...

, but Greenwood Leflore, a district Choctaw chief, informed Secretary of War John H. Eaton that the warriors were fiercely opposed to attending.[

] Jackson was angered. Journalist Len Green writes "although angered by the Choctaw refusal to meet him in Tennessee, Jackson felt from LeFlore's words that he might have a foot in the door and dispatched Secretary of War Eaton and John Coffee to meet with the Choctaws in their nation."[

] Jackson appointed Eaton and General John Coffee as commissioners to represent him to meet the Choctaws at the Dancing Rabbit Creek near present-day Noxubee County, Mississippi

Noxubee County is a county located in the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2010 census, its population was 11,545. Its county seat is Macon. The name is derived from the Choctaw word ''nakshobi'' meaning "to stink".

Geography

According t ...

.

The commissioners met with the chiefs and headmen on September 15, 1830, at Dancing Rabbit Creek.[

] In carnival-like atmosphere, the policy of removal was explained to an audience of 6,000 men, women, and children.[ The treaty would sign away the remaining traditional homeland to the US; however, a provision in the treaty made removal more acceptable:

] On September 27, 1830, the

On September 27, 1830, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was a treaty which was signed on September 27, 1830, and proclaimed on February 24, 1831, between the Choctaw American Indian tribe and the United States Government. This treaty was the first removal treaty wh ...

was signed. It represented one of the largest transfers of land that was signed between the US government and Native Americans without being instigated by warfare. By the treaty, the Choctaws signed away their remaining traditional homelands, opening them up for European-American settlement. The Choctaw were the first to walk the Trail of Tears. Article XIV allowed for nearly 1,300 Choctaws to remain in the state of Mississippi and to become the first major non-European ethnic group to become US citizens.[

][

][

] Article 22 sought to put a Choctaw representative in the U.S. House of Representatives.Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians ( cho, Mississippi Chahta) is one of three federally recognized tribes of Choctaw Native Americans, and the only one in the state of Mississippi. On April 20, 1945, this tribe organized under the Indian R ...

. The nation retained its autonomy, but the tribe in Mississippi submitted to state and federal laws.[Kidwell (2007); Kidwell (1995)]

Reservation establishment in Oklahoma (1830-1860)

The Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

, a law implementing Removal Policy, was signed by President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

on May 28, 1830. The act delineated Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

, where the U.S. federal government forcibly relocated tribes from across the United States, including Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands (such as the Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

, Yuchi

The Yuchi people, also spelled Euchee and Uchee, are a Native American tribe based in Oklahoma.

In the 16th century, Yuchi people lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee. In the late 17th century, they moved south to Alabama, G ...

, Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

, Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

, Choctaw, Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands[Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...]

). The forced relocation of the Choctaw Nation in 1831 is called the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

. In 1834, U.S. Congress defined the first Indian Territory, with the Five Civilized Tribes occupying the land that eventually became the State of Oklahoma, excluding its panhandle.

Influence of Cyrus Kingsbury's Choctaw Mission (1840)

The Reverend Cyrus Kingsbury

Cyrus Kingsbury (November 22, 1786 – June 27, 1870) was a Christian missionary active among the American Indians in the nineteenth century. He first worked with the Cherokee and founded Brainerd Mission near Chickamauga, Tennessee, later he serv ...

, who had ministered among the Choctaw since 1818, accompanied the Choctaws from the Mayhew Mission in Oktibbeha County, Mississippi

Oktibbeha County is a county in the east central portion of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2020 census the population was 51,788. The county seat is Starkville. The county's name is derived from a local Native American word meani ...

to their new location in Indian Territory. He established the church in Boggy Depot

''Boggy Depot'' is the debut solo album by Alice in Chains guitarist and vocalist Jerry Cantrell. The vinyl edition was released on March 31, 1998, and the CD was released on April 7, 1998 through Columbia Records. The album was named after the ...

in 1840. The church building was the temporary capitol of the Choctaw Nation in 1859. Allen Wright (principal chief of the Choctaw Republic from late 1866 to 1870) lived much of his early life with Kingsbury at Doaksville

Doaksville is a former settlement, now a ghost town, located in present-day Choctaw County, Oklahoma. It was founded between 1824 and 1831, by people of the Choctaw Indian tribe who were forced to leave their homes in the Southeastern United Stat ...

and the mission school at Pine Ridge. Armstrong Academy was founded in Chahta Tamaha, Indian Territory

Chahta Tamaha (Choctaw Town) served as the capital of the Choctaw Nation from 1863 to 1883 in Indian Territory. The town developed initially around the Armstrong Academy, which was operated by Protestant religious missionaries from 1844 to 1861 to ...

as a school for Choctaw boys in 1844.

Great Irish Famine aid (1847)

Midway through the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849), a group of Choctaw collected $170 ($ in current dollar terms) and sent it to help starving Irish men, women and children. "It had been just 16 years since the Choctaw people had experienced the

Midway through the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849), a group of Choctaw collected $170 ($ in current dollar terms) and sent it to help starving Irish men, women and children. "It had been just 16 years since the Choctaw people had experienced the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

, and they had faced starvation... It was an amazing gesture. By today's standards, it might be a million dollars," wrote Judy Allen in 1992, editor of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma's newspaper, ''Bishinik''. To mark the 150th anniversary, eight Irish people came to the US to retrace the Trail of Tears to raise money for Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

n relief.Angie Debo

Angie Elbertha Debo (January 30, 1890 – February 21, 1988), 's ''The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic'', various articles corrected the cited amount of this donation, saying it was $170 ($).)

In 2015 a sculpture known as '' Kindred Spirits'' was erected in the town of Midleton

Midleton (; , meaning "monastery at the weir") is a town in south-eastern County Cork, Ireland. It lies approximately 16 km east of Cork City on the Owenacurra River and the N25 road, which connects Cork to the port of Rosslare. A satellit ...

, County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns a ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

to commemorate the Choctaw Nation's donation. A delegation of 20 members of the Choctaw Nation attended the opening ceremony along with the County Mayor of Cork.

In 2018 Irish Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legislature) and the o ...

(Prime Minister) Leo Varadkar announced the Choctaw-Ireland Scholarship Programme - an opportunity for Choctaw students to study in Ireland. The program was launched "in recognition of the act of generosity and humanitarianism shown by the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma towards the people of Ireland during the Great Famine of the mid-Nineteenth Century, and to foster and deepen the ties between the two nations today". However, the programme is only available for postgraduate students, and those studying at Cork University; within the disciplines of Art, Social Sciences or Celtic Studies.

Controversy over Slaveholding and separation from Chickasaw Nation (1855)

In Spring 1855, the ABCFM sent Dr. George Warren Wood

George Warren Wood (known professionally as George W. Wood) (1814–1901) was a Presbyterian minister and missionary who became the secretary of the Congregationalist American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. He was an early missio ...

to visit the Choctaw Mission in Oklahoma to resolve a crisis over the abolition issue. After arriving in Stockbridge Mission, Wood spent over two weeks days visiting missions including the Goodwater Mission, Wheelock Academy, Spencer Academy, and other mission schools. He met with missionaries to discuss Selah B Treat's June 22, 1848 letter permitting them to maintain fellowship with slaveholders. Ultimately, the crisis was not resolved, and by 1859, the Board cut ties to the Choctaw mission altogether.

In 1855, the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations formally separated. Doaksville

Doaksville is a former settlement, now a ghost town, located in present-day Choctaw County, Oklahoma. It was founded between 1824 and 1831, by people of the Choctaw Indian tribe who were forced to leave their homes in the Southeastern United Stat ...

served as the capital of the Choctaw Nation between 1860 and 1863. An 1860 convention in Doaksville ratified the Doaksville Constitution that guided the Choctaw Nation until 1906. The capital moved to Mayhew Mission in 1859, then to Chahta Tamaha in 1863.Fort Towson

Fort Towson was a frontier outpost for Frontier Army Quartermasters along the Permanent Indian Frontier located about two miles (3 km) northeast of the present community of Fort Towson, Oklahoma. Located on Gates Creek near the confluence ...

.["Doaksville." Oklahoma Historical Society.](_blank)

Retrieved August 7, 2014.

American Civil War in Indian Territory (1861-65)

The Choctaws sided with the South during the Civil War. Tribal members had become successful cotton planters—owning many slaves. The most famous Choctaw planter was Robert M. Jones. He was part Choctaw and had become influential in politics. Jones eventually supported the Confederacy and became a non-voting member in the Confederacy's House of Representatives. Jones was key for steering the Choctaw Nation in an alliance with the Confederacy. By 1860, the Choctaw Nation lived in a relatively calm and remote society. Many Indian citizen members had become successful farmers, planters, and business men. Angie Debo

Angie Elbertha Debo (January 30, 1890 – February 21, 1988), , author of ''The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic'', wrote: "Taken as a whole the generation from 1833 to 1861 presents a record of orderly development almost unprecedented in the history of any people."[

]

Territory transition to statehood (1900)

By the early twentieth century, the United States government had passed laws that reduced the Choctaw's sovereignty and tribal rights in preparation for the extinguishing of land claims and for Indian Territory to be admitted, along with Oklahoma Territory, as part of the State of Oklahoma.

Under the Dawes Act, in violation of earlier treaties, the

By the early twentieth century, the United States government had passed laws that reduced the Choctaw's sovereignty and tribal rights in preparation for the extinguishing of land claims and for Indian Territory to be admitted, along with Oklahoma Territory, as part of the State of Oklahoma.

Under the Dawes Act, in violation of earlier treaties, the Dawes Commission

The American Dawes Commission, named for its first chairman Henry L. Dawes, was authorized under a rider to an Indian Office appropriation bill, March 3, 1893. Its purpose was to convince the Five Civilized Tribes to agree to cede tribal title of I ...

registered tribal members in official rolls. It forced individual land allotments upon the Tribe's heads of household, and the government classified land beyond these allotments as "surplus", and available to be sold to both native and non-natives. It was primarily intended for European-American (white) settlement and development.

The government created "guardianship" by third parties who controlled allotments while the owners were underage. During the oil boom of the early 20th century, the guardianships became very lucrative; there was widespread abuse and financial exploitation of Choctaw individuals. Charles Haskell, the future governor of Oklahoma, was among the white elite who took advantage of the situation.

An Act of 1906 spelled out the final tribal dissolution agreements for all of the five civilized tribes and dissolved the Choctaw government. The Act also set aside a timber reserve, which might be sold at a later time; it specifically excluded coal and asphalt lands from allotment. After Oklahoma was admitted as a state in 1907, tribal chiefs of the Choctaw and other nations were appointed by the Secretary of the Interior.

Pioneering the use of code talking (1918)

During World War I the American army fighting in France became stymied by the Germans' ability to intercept its communications. The Germans successfully decrypted the codes, and were able to read the Americans' secrets and know their every move in advance.["World War I's Native American Code Talker]

Greenspan, Joseph. "World War I's Native American Code Talkers."

''History'', 29 May 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

Several Choctaw serving in the 142nd Infantry suggested using their native tongue, the Choctaw language

The Choctaw language (Choctaw: ), spoken by the Choctaw, an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, is part of the Muskogean language family. Chickasaw is separate but closely related language to Choctaw.

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahom ...

, to transmit army secrets. The Germans were unable to penetrate their language. This change enabled the Americans to protect their actions and almost immediately contributed to a turn-around on the Meuse-Argonne front. Captured German officers said they were baffled by the Choctaw words, which they were completely unable to translate. According to historian Joseph Greenspan, the Choctaw language did not have words for many military ideas, so the code-talkers had to invent other terms from their language. Examples are "'big gun' for artillery, 'little gun shoot fast' for machine gun, 'stone' for grenade and 'scalps' for casualties."Choctaw Code Talkers

The Choctaw code talkers were a group of Choctaw Indians from Oklahoma who pioneered the use of Native American languages as military code during World War I.

The government of the Choctaw Nation maintains that the men were the first America ...

. The Army repeated the use of Native Americans as code talkers during World War II, working with soldiers from a variety of American Indian tribes, including the Navajo. Collectively the Native Americans who performed such functions are known as code talkers

A code talker was a person employed by the military during wartime to use a little-known language as a means of secret communication. The term is now usually associated with United States service members during the world wars who used their k ...

.

Citizenship (1920s)

The Burke Act

The Burke Act (1906), formally known as the General Allotment Act Amendment of 1906 and also called the Forced Fee Patenting Act, amended the Dawes Act of 1887 under which the communal land held by tribes on the Indian reservations was broken up ...

of 1906 provided that tribal members would become full United States citizens within 25 years, if not before. In 1928 tribal leaders organized a convention of Choctaw and Chickasaw tribe members from throughout Oklahoma. They met in Ardmore to discuss the burdens being placed upon the tribes due to passage and implementation of the Indian Citizenship Act

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, (, enacted June 2, 1924) was an Act of the United States Congress that granted US citizenship to the indigenous peoples of the United States. While the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitutio ...

and the Burke Act. Since their tribal governments had been abolished, the tribes were concerned about the inability to secure funds that were due them for leasing their coal and asphalt lands, in order to provide for their tribe members. Czarina Conlan

Czarina Conlan (1871-1958) was a Choctaw-Chickasaw archivist and museum curator. She worked at the Oklahoma Historical Society museum for 24 years. She founded the first woman's club in Indian Territory and served as the chair of the Oklahoma Ind ...

was selected as chair of the convention. They appointed a committee composed of Henry J. Bond, Conlan, Peter J. Hudson, T.W. Hunter and Dr. E. N Wright, for the Choctaw; and Ruford Bond, Franklin Bourland, George W. Burris, Walter Colbert and Estelle Ward, for the Chickasaw to determine how to address their concerns.[ ]

After meeting to prepare the recommendation, the committee broke with precedent when it sent Czarina Conlan

Czarina Conlan (1871-1958) was a Choctaw-Chickasaw archivist and museum curator. She worked at the Oklahoma Historical Society museum for 24 years. She founded the first woman's club in Indian Territory and served as the chair of the Oklahoma Ind ...

(Choctaw) and Estelle Chisholm Ward

Estelle Chisholm Ward (June 18, 1875 – December 9, 1946) was an Oklahoma teacher, journalist and magazine publisher. She was active in politics both civic and tribal and was elected as county treasurer of Johnston County, Oklahoma. Ward was th ...

(Chickasaw) to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

to argue in favor of passage of a bill proposed by U.S. House Representative Wilburn Cartwright

Wilburn Cartwright (January 12, 1892 – March 14, 1979) was a lawyer, educator, U.S. Representative from Oklahoma, and United States Army officer in World War II. The town of Cartwright, Oklahoma is named after him.

Early life

Born on a fa ...

. It proposed sale of the coal and asphalt holdings, but continuing restrictions against sales of Indian lands. This was the first time that women had been sent to Washington as representatives of their tribes.[ ]

Termination efforts (1950s)

From the late 1940s through the 1960s, the federal government pursued an Indian termination policy

Indian termination is a phrase describing United States policies relating to Native Americans from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s. It was shaped by a series of laws and practices with the intent of assimilating Native Americans into mainstream ...

, to end the special relationship of tribes. Retreating from the emphasis of self-government of Indian tribes, Congress passed a series of laws to enable the government to end its trust relationships with native tribes. On 13 August 1946, it passed the Indian Claims Commission The Indian Claims Commission was a judicial relations arbiter between the United States federal government and Native American tribes. It was established under the Indian Claims Act of 1946 by the United States Congress to hear any longstanding clai ...

Act of 1946, Pub. L. No. 79-726, ch. 959. Its purpose was to settle for all time any outstanding grievances or claims the tribes might have against the U.S. for treaty breaches (which were numerous), unauthorized taking of land, dishonorable or unfair dealings, or inadequate compensation on land purchases or annuity payments. Claims had to be filed within a five-year period.

Most of the 370 complaints submitted were filed at the approach of the 5-year deadline in August 1951.Carl Albert

Carl Bert Albert (May 10, 1908 – February 4, 2000) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 46th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1971 to 1977 and represented Oklahoma's 3rd congressional district as a ...

of Oklahoma to introduce federal legislation to begin terminating the Choctaw tribe.Wyandotte Nation

The Wyandotte Nation is a Federally recognized tribes, federally recognized Native American tribe in northeastern Oklahoma. They are descendants of the Wyandot people, Wendat Confederacy and Native Americans with territory near Georgian Bay and ...

, Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

The Peoria, also Peouaroua, are a Native American people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma headquartered in Miami, Oklahoma.

The Peoria people are descendants of the Illinois Confederation. The ...

, Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma

The Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma is one of four federally recognized Native American tribes of Odawa people in the United States. Its Algonquian-speaking ancestors had migrated gradually from the Atlantic coast and Great Lakes areas, reaching what a ...

, and Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma

The Modoc Nation is a federally recognized tribe of Modoc people, located in Ottawa County in the northeast corner of Oklahoma and Modoc and Siskiyou counties in northeast California.Self, Burl EModoc.''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia ...

. In 1969, ten years after passage of the Choctaw termination bill and one year before the Choctaws were to be terminated, word spread throughout the tribe that Belvin's law was a termination bill. Outrage over the bill generated a feeling of betrayal, and tribal activists formed resistance groups opposing termination. Groups such as the Choctaw Youth Movement in the late 1960s fought politically against the termination law. They helped create a new sense of tribal pride, especially among younger generations. Their protest delayed termination; Congress repealed the law on 24 August 1970.

Self-determination 1970s-present

The 1970s were a crucial and defining decade for the Choctaw. To a large degree, the Choctaw repudiated the more extreme Indian activism. They sought a local grassroots solution to reclaim their cultural identity and sovereignty as a nation.

Republican President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, long sympathetic to American Indian rights, ended the government's push for termination. On August 24, 1970, he signed a bill repealing the Termination Act of 1959, before the Choctaw would have been terminated. Some Oklahoma Choctaw organized a grassroots movement to change the direction of the tribal government. In 1971, the Choctaw held their first popular election of a chief since Oklahoma entered the Union in 1907. Nixon stated the tribes had a right to determine their own destiny.

A group calling themselves the Oklahoma City Council of Choctaws endorsed thirty-one-year-old David Gardner for chief, in opposition to the current chief, seventy-year-old Harry Belvin. Gardner campaigned on a platform of greater financial accountability, increased educational benefits, the creation of a tribal newspaper, and increased economic opportunities for the Choctaw people. Amid charges of fraud and rule changes concerning age, Gardner was declared ineligible to run. He did not meet the new minimum age requirement of thirty-five. Belvin was re-elected to a four-year term as chief.

In 1975, thirty-five-year-old David Gardner defeated Belvin to become the Choctaw Nation's second popularly elected chief. 1975 also marked the year that the United States Congress passed the landmark Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act

The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 (Public Law 93-638) authorized the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, and some other government agencies to enter into contracts with, a ...

, which had been supported by Nixon before he resigned his office due to the Watergate scandal. This law revolutionized the relationship between Indian Nations and the federal government by providing for nations to make contracts with the BIA, in order to gain control over general administration of funds destined for them.

Native American tribes such as the Choctaw were granted the power to negotiate and contract directly for services, as well as to determine what services were in the best interest of their people. During Gardner's term as chief, a tribal newspaper, ''Hello Choctaw'', was established. In addition, the Choctaw directed their activism at regaining rights to land and other resources. With the Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands[Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...]

nations, the Choctaw successfully sued the federal and state government over riverbed rights to the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

.

Discussions began on the issue of drafting and adopting a new constitution for the Choctaw people. A movement began to increase official enrollment of members, increase voter participation, and preserve the Choctaw language. In early 1978, David Gardner died of cancer at the age of thirty-seven. Hollis Roberts

Hollis Earl Roberts (May 9, 1943 – October 19, 2011) was a Native American politician whose career was highlighted by his 19-year period as Chief of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Hollis Roberts was born in Hochatown to Laura Beam Roberts and ...

was elected chief in a special election, serving from 1978 to 1997.

In June 1978 the ''Bishinik'' replaced ''Hello Choctaw'' as the tribal newspaper. Spirited debates over a proposed constitution divided the people. In May 1979, they adopted a new constitution for the Choctaw nation.

Faced with termination as a sovereign nation in 1970, the Choctaws emerged a decade later as a tribal government with a constitution, a popularly elected chief, a newspaper, and the prospects of an emerging economy and infrastructure that would serve as the basis for further empowerment and growth.

Notable tribal members

* Lane Adams (b. 1989),

* Lane Adams (b. 1989), Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (AL), ...

player, Philadelphia Phillies (nephew of Choctaw member and attorney Kalyn Free

Kalyn Free is an American attorney, former political candidate, and a tribal citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

Early legal and political career

Free was born in Red Oak, Oklahoma. Free is a graduate of Red Oak High School, Southeastern ...

)

* Marcus Amerman

Marcus Amerman is a Choctaw bead artist, glass artist, painter, fashion designer, and performance artist, living in Idaho. He is known for his highly realistic beadwork portraits.

Background

Marcus Amerman was born in Phoenix, Arizona in 1959 bu ...

(b. 1959), bead, glass, and performance artist

* David W. Anderson, 9th Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs

* Jim Weaver Barnes (b. 1933), poet, writer, rancher, and former professor

* Gary Batton

Gary Dale Batton (born December 15, 1966) is a tribal administrator and politician, the current and 47th Chief of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. It is the third-largest federally recognized tribe and second-largest reservation in total area.

Bat ...

(b. 1966), Chief of the Choctaw Nation

* Ada E. Brown (b. 1974), appointed by President Donald Trump to be a federal judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas

* Michael Burrage (b. 1950), former U.S. District Judge

* Sean Burrage (b. 1968), President of Southeastern Oklahoma State University

* Steve Burrage (b. 1952), former Oklahoma State Auditor and Inspector

* Clarence Carnes

Clarence Victor Carnes (January 14, 1927 – October 3, 1988), known as The Choctaw Kid, was a Choctaw man best known as the youngest inmate incarcerated at Alcatraz and for his participation in the bloody escape attempt known as the "Battle ...

(1927–1988), imprisoned at Alcatraz

* Czarina Conlan

Czarina Conlan (1871-1958) was a Choctaw-Chickasaw archivist and museum curator. She worked at the Oklahoma Historical Society museum for 24 years. She founded the first woman's club in Indian Territory and served as the chair of the Oklahoma Ind ...

(1871-1958), suffragist, first woman to represent the Choctaw in Washington, D.C. and first woman elected to a school board in Oklahoma

* Samantha Crain

Samantha Crain (born August 15, 1986) is a Choctaw Nation songwriter, musician, producer, and singer from Shawnee, Oklahoma, signed with Ramseur Records (North America) and Real Kind Records (an imprint of Communion Records) and Full Time Hob ...

(b. 1986), singer-songwriter, musician

* Scott Fetgatter

Scott Fetgatter (born July 4, 1968) is a Choctaw American politician who has served in the Oklahoma House of Representatives

The Oklahoma House of Representatives is the lower house of the legislature of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Its memb ...

(b. 1968), Member of the Oklahoma House of Representatives from the 16th district

* John Hope Franklin

John Hope Franklin (January 2, 1915 – March 25, 2009) was an American historian of the United States and former president of Phi Beta Kappa, the Organization of American Historians, the American Historical Association, and the Southern Histo ...

(1915-2009), African-American historian whose mother was of partial Choctaw descent

* Tobias William Frazier, Sr. (1892–1975), Choctaw code talker

* Kalyn Free

Kalyn Free is an American attorney, former political candidate, and a tribal citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

Early legal and political career

Free was born in Red Oak, Oklahoma. Free is a graduate of Red Oak High School, Southeastern ...

, attorney

* Rosella Hightower

Rosella Hightower (January 10, 1920 – November 4, 2008) was an American ballerina and member of the Choctaw Nation who achieved fame in both the United States and Europe.

Biography

Rosella Hightower was born in Durwood, Carter County, Oklahoma ...

(1920–2008), prima ballerina

* Norma Howard

Norma Howard (born 1958) is a Choctaw-Chickasaw Native American artist from Stigler, Oklahoma, who paints genre scenes of children playing, women working in fields, and other images inspired by family stories and Choctaw life. Howard won her f ...

(b. 1958), visual artist

* LeAnne Howe

LeAnne Howe (born April 29, 1951, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma) is an American author and Eidson Distinguished Professor in the Department of English at the University of Georgia, Athens. She previously taught American Indian Studies and English ...

(b. 1951), writer and academic

* Phil Lucas Phil Lucas (1942 – February 4, 2007) was an American filmmaker of mostly Native American themes. He was an actor, writer, producer, director and editor for more than 100 films/documentaries or television programs starting as early as 1979 whe ...

(1942–2007), filmmaker

* Green McCurtain

Greenwood "Green" McCurtain (November 28, 1848 – December 27, 1910) was a tribal administrator and Principal Chief of the Choctaw Republic (1896–1900 and 1902–1906), serving a total of four elected two-year terms. He was the third of his bro ...

(d. 1910), Chief from 1902–1910 (appointed by US government 1906-1910)

* Cal McLish

Calvin Coolidge Julius Caesar Tuskahoma McLish (December 1, 1925 – August 26, 2010), nicknamed "Bus", was an American professional baseball pitcher and coach, who played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Brooklyn Dodgers (, ), Pittsburg ...

(1925–2010), Major League Baseball pitcher

* Devon A. Mihesuah (b. 1957), author, editor, historian

* Joseph Oklahombi

Joseph Oklahombi (May 1, 1895, Bokchito, Blue County, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory - April 13, 1960) was an American soldier of the Choctaw nation. He was the most-decorated World War I soldier from Oklahoma. He served in Company D, First ...

(1895-1960), Choctaw code talker

* Peter Pitchlynn

Peter Perkins Pitchlynn ( cho, Hatchootucknee, italic=no, ) (January 30, 1806 – January 17, 1881) was a Choctaw chief of Choctaw and Anglo-American ancestry. He was principal chief of the Choctaw Republic from 1864-1866 and surrendered to the ...

(1806–1881), Chief from 1860–1866

* Gregory E. Pyle (1949-2019), former Chief of the Choctaw Nation

* Hollis E. Roberts (1943-2011), former Chief of the Choctaw Nation

* Oral Roberts

Granville Oral Roberts (January 24, 1918 – December 15, 2009) was an American Charismatic Christian televangelist, ordained in both the Pentecostal Holiness and United Methodist churches. He is considered one of the forerunners of t ...

(1918-2009), evangelist

* R. Trent Shores, United States Attorney for the Northern District of Oklahoma since 2017

* William Grady Stigler

William Grady Stigler (July 7, 1891 – August 21, 1952) was an American lawyer, World War I veteran, and politician who served four terms as and a U.S. Representative from Oklahoma from 1944 to 1952.

Biography

Stigler was a citizen of the Cho ...

(1891-1952), U.S. Representative from Oklahoma 2nd District, 1944–52

* Bryan Terry

Bryan Terry (born October 27, 1968) is an American doctor and politician from the state of Tennessee. A Republican, Terry has represented the 48th district of the Tennessee House of Representatives, based in eastern Murfreesboro, since 2015. He i ...

(b. 1968), Member of the Tennessee House of Representatives from the 48th district

* Tim Tingle

Tim Tingle is a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma an author and storyteller of twenty books.

Early life

Tingle was raised on the Gulf Coast outside of Houston, Texas. He is an Oklahoma Choctaw. His great-great grandfather, John Carnes, ...

, writer and storyteller

* Wilma Victor

Wilma Louise Victor (November 5, 1919 – November 15, 1987) was a Choctaw educator.

She was born in Idabel, Oklahoma on November 5, 1919. A friend of hers was employed at the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and arranged for her to recei ...

(1919–1987), educator, first lieutenant in Women's Army Corps (1943-1946), special assistant to Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton (1971-1975)

* Summer Wesley (b. 1981), attorney, writer, and activist

* Wallace Willis

Wallace Willis was a Choctaw freedman living in the Indian Territory, in what is now Choctaw County, near the city of Hugo, Oklahoma, US. His dates are unclear: perhaps 1820 to 1880. He is credited with composing (probably before 1860) several ...

, composer of Negro spirituals

Spirituals (also known as Negro spirituals, African American spirituals, Black spirituals, or spiritual music) is a genre of Christian music that is associated with Black Americans, which merged sub-Saharan African cultural heritage with the ex ...

, including Swing Low, Sweet Chariot and Roll, Jordan, Roll

"Roll, Jordan, Roll" (Roud 6697), also "Roll, Jordan", is a spiritual created by enslaved African Americans, developed from a song written by Isaac Watts in the 18th century which became well known among slaves in the United States during the 1 ...

, Choctaw slave and Freedmen owned by Britt Willis

* Allen Wright (1826-1885), Chief from 1866–1870

* Muriel Hazel Wright

Muriel Hazel Wright (31 March 1889 – 27 February 1975) was an American teacher, historian and writer on the Choctaw Nation. A native of Indian Territory, she was the daughter of mixed-blood Choctaw physician Eliphalet Wright and the granddaug ...

(1889-1975), teacher, historian and writer, granddaughter of Chief Allen Wright

See also

* Choctaw code talkers

The Choctaw code talkers were a group of Choctaw Indians from Oklahoma who pioneered the use of Native American languages as military code during World War I.

The government of the Choctaw Nation maintains that the men were the first America ...

, World War I veterans who provided a secure means of communication in their language; first Native American code talkers

* Choctaw culture

The culture of the Choctaw has greatly evolved over the centuries combining mostly European-American influences; however, interaction with Spain, France, and England greatly shaped it as well. The Choctaws, or Chahtas, are a Native American peopl ...

* Choctaw mythology

Choctaw mythology is part of the culture of the Choctaw, a Native American tribe originally occupying a large territory in the present-day Southeastern United States: much of the states of Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana. In the 19th ce ...

* Choctaw Trail of Tears

The Choctaw Trail of Tears was the attempted ethnic cleansing and relocation by the United States government of the Choctaw Nation from their country, referred to now as the Deep South (Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana), to lands we ...

* Jena Band of Choctaw Indians

The Jena Band of Choctaw Indians ( cho, Jena Chahta) are one of three federally recognized Choctaw tribes in the United States. They are based in La Salle, Catahoula, and Grant parishes in the U.S. state of Louisiana. The Jena Band received fe ...

, Louisiana

* Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians ( cho, Mississippi Chahta) is one of three federally recognized tribes of Choctaw Native Americans, and the only one in the state of Mississippi. On April 20, 1945, this tribe organized under the Indian R ...

* List of Indian Reservations

This is a list of Indian reservations and other tribal homelands in the United States. In Canada, the Indian reserve is a similar institution.

Federally recognized reservations

There are 326 Indian Reservations in the United States. Most of ...

Notes

References

External links

Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma

official website

Choctaw Nation Health Services Authority

Accessed May 15, 2015.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Choctaw Nation Of Oklahoma

Native American tribes in Oklahoma

American Indian reservations in Oklahoma

1786 establishments in the United States

1830 establishments in the United States

Federally recognized tribes in the United States

The Tribal council members are the voice and representation of the Choctaw people in the tribal government. In order to be elected as council members, candidates must have resided in their respective districts for at least one year immediately preceding the election and must be at least one-fourth Choctaw Indian by blood and at least twenty-one years of age. Once elected, council members must remain a resident of their district during the term in office.

Once in office, the Tribal council members have regularly scheduled county council meetings. The presence of these tribal leaders in the Indian community creates a sense of understanding of their community and its needs. The Tribal Council is responsible for adopting rules and regulations which govern the Choctaw Nation, for approving all budgets, decisions concerning the management of tribal property, and all other legislative matters. The Tribal Council assists the community to implement an economic development strategy and to plan, organize, and direct Tribal resources to achieve self-sufficiency.

The Tribal council members are the voice and representation of the Choctaw people in the tribal government. In order to be elected as council members, candidates must have resided in their respective districts for at least one year immediately preceding the election and must be at least one-fourth Choctaw Indian by blood and at least twenty-one years of age. Once elected, council members must remain a resident of their district during the term in office.