Carnegie (yacht) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Carnegie'' was a

''Carnegie'' was a

Magnetic Survey Yacht ''Carnegie''

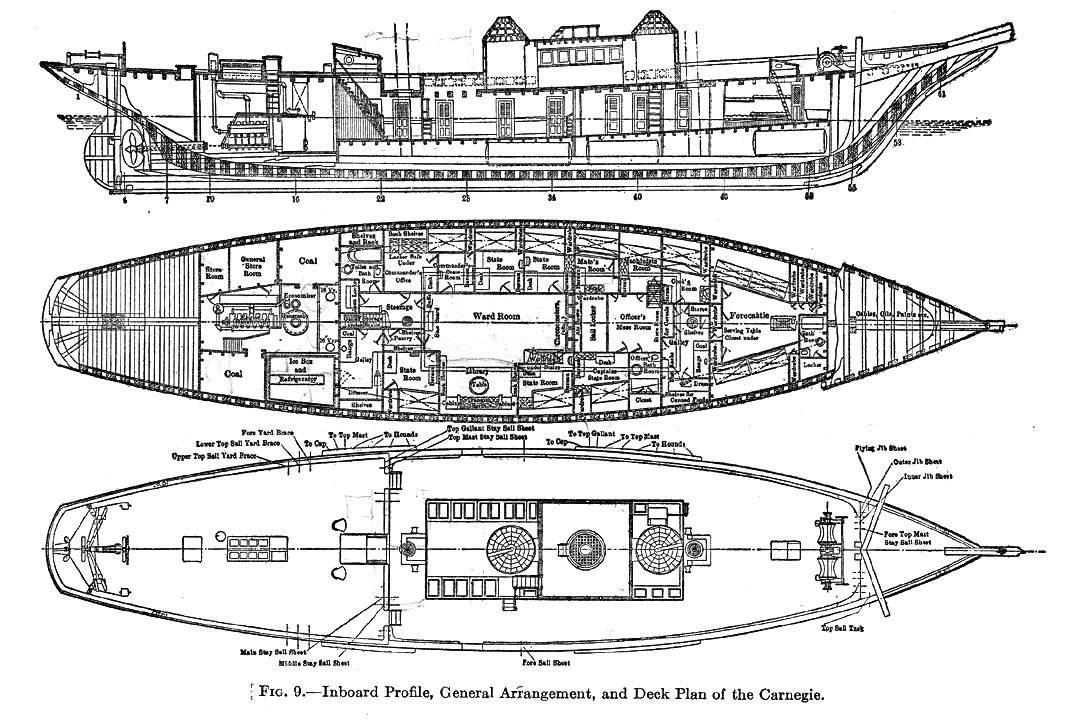

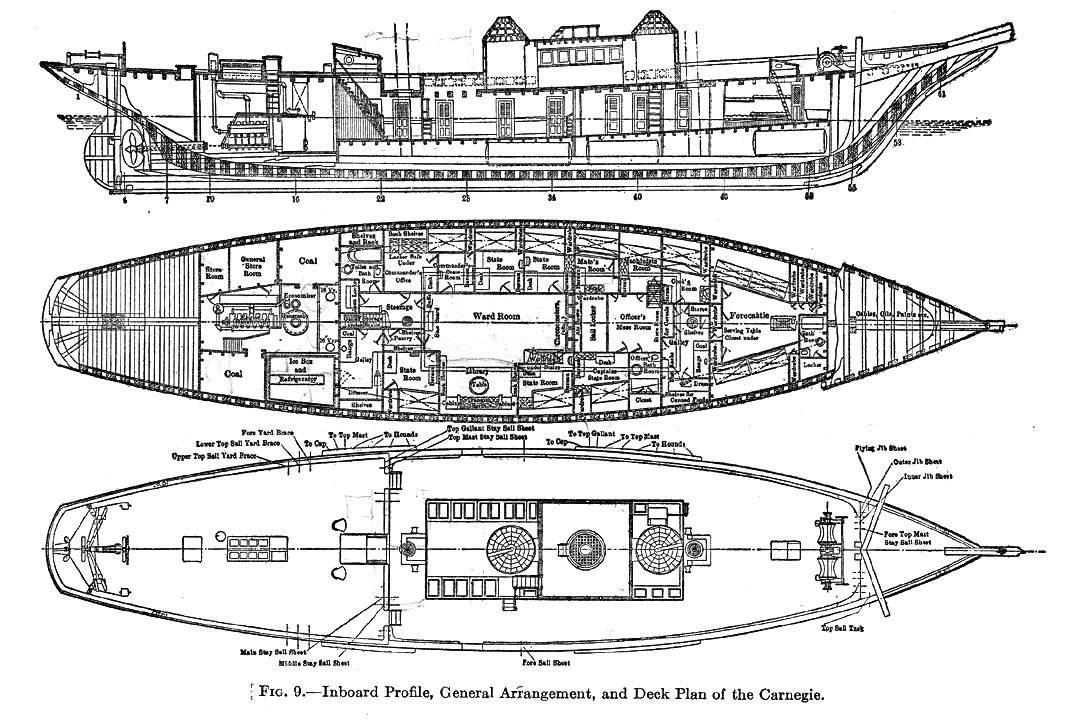

(''International Marine Engineering'', February 1909) {{DEFAULTSORT:Carnegie (Ship) Brigantines Research vessels of the United States 1909 ships

''Carnegie'' was a

''Carnegie'' was a brigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Older ...

yacht, equipped as a research vessel, constructed almost entirely from wood and other non-magnetic materials to allow sensitive magnetic measurements to be taken for the Carnegie Institution

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. Th ...

's Department of Terrestrial Magnetism. She carried out a series of cruises from her launch in 1909 to her destruction by an onboard explosion while in port in 1929. She covered almost in her twenty years at sea.

The Carnegie Rupes on the planet Mercury are named after this research vessel.

Construction

Louis Agricola Bauer

Louis Agricola Bauer (January 26, 1865 – April 12, 1932) was an American geophysicist, astronomer and magnetician.

Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, he graduated from the University of Cincinnati in 1888, and he immediately started work for the Uni ...

, the first director of the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism at the Carnegie Institution, wanted to focus on acquiring oceanic magnetic data to improve the understanding of the Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magnetic f ...

. After an experiment in which the brigantine ''Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

'' was adapted by removing as much magnetic material as possible, it became clear that a new entirely non-magnetic ship was needed. After convincing the institution's board, Bauer set about getting such a vessel built. ''Carnegie'' was designed by naval architect This is the top category for all articles related to architecture and its practitioners.

{{Commons category, Architecture occupations

Design occupations

Architecture, Occupations ...

Henry J. Gielow and built at the Tebo Yacht Basin Company yard in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. Gielow's design minimised the amount of magnetic materials used in its construction and fittings. Locust trunnels were used to hold together the timbers with the help of some bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

or copper bolts. ''Carnegie'' was primarily a sailing vessel, but its unique, non-ferrous, auxiliary engine was capable of propelling the vessel in calm weather at a speed of 6 knot

A knot is an intentional complication in cordage which may be practical or decorative, or both. Practical knots are classified by function, including hitches, bends, loop knots, and splices: a ''hitch'' fastens a rope to another object; a ' ...

s. The construction used white oak

The genus ''Quercus'' contains about 500 species, some of which are listed here. The genus, as is the case with many large genera, is divided into subgenera and sections. Traditionally, the genus ''Quercus'' was divided into the two subgenera '' ...

, yellow pine

In ecology and forestry, yellow pine refers to a number of conifer species that tend to grow in similar plant communities and yield similar strong wood. In the Western United States, yellow pine refers to Jeffrey pine or ponderosa pine. In the S ...

, and Oregon pine

The Douglas fir (''Pseudotsuga menziesii'') is an evergreen conifer species in the pine family, Pinaceae. It is native to western North America and is also known as Douglas-fir, Douglas spruce, Oregon pine, and Columbian pine. There are thre ...

with copper or bronze-composition metal for all the fastenings in the hull or rigging. The anchors were made of bronze and were attached to hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

cables. A reserve engine was required to increase manoeuvrability and allow passage through the doldrums

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ ), known by sailors as the doldrums or the calms because of its monotonous windless weather, is the area where the northeast and the southeast trade winds converge. It encircles Earth near the thermal e ...

, so ''Carnegie'' was fitted with a producer gas

Producer gas is fuel gas that is manufactured by blowing a coke or coal with air and steam simultaneously. It mainly consists of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), as well as substantial amounts of nitrogen (N2). The caloric value of the produce ...

engine, made mainly of copper and bronze, using coal as a fuel. She cost $115,000 (about 10 million dollars today) to build.

''Carnegie'' was long with a beam of . She was rigged as a brigantine, with square sails on the foremast, giving a total sail area of . The most distinctive feature was the observation deck, with its two observing domes made of glass in bronze frames. This allowed observations to be made under all weather conditions.

Cruises

Between 1909 and 1921 ''Carnegie'' carried out 6 cruises, including one where she managed the fastestcircumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circ ...

of Antarctica by a sailing vessel, in 118 days, a testing voyage where thirty icebergs were sighted on a single day. William John Peters

William John Peters (February 5, 1863 – July 10, 1942) was an American explorer and scientist who worked extensively in the Arctic and tropics. His significant contributions the study of geomagnetism at sea in the early 1900s helped lay the fou ...

captained cruises I and II, James P. Ault captained cruises III, IV, and VI, and Harry Marcus Weston Edmonds captained cruise V. During the 6 cruises the Carnegie sailed more than 250,000 nautical miles and traversed all oceans between latitudes 80º N. and 60º S. From 1921 to 1927 ''Carnegie'' was laid up for an extensive refurbishment, including new deck timbers and a thicker copper hull. The old producer gas engine was replaced with a gasoline fuelled one. In 1928, under Captain James P. Ault, ''Carnegie'' set off on the seventh cruise, which was intended to take three years. Soundings taken during this voyage discovered the Carnegie Ridge

The Carnegie Ridge is an aseismic ridge on the Nazca Plate that is being subducted beneath the South American Plate. The ridge is thought to be a result of the passage of the Nazca Plate over the Galapagos hotspot. It is named for the research ...

off Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

.

Destruction

After completing of the planned voyage, ''Carnegie'' put into the port ofApia, Samoa

Apia () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city of Samoa, as well as the nation's only city. It is located on the central north coast of Upolu, Samoa's second-largest island. Apia falls within the political district (''itūmālō ...

for supplies on 28 November 1929. While refuelling with gasoline there was an explosion, which mortally wounded Captain Ault and killed the cabin boy. ''Carnegie'' burnt to the waterline within a few hours.

Scientific legacy

''Carnegie'' carried a wide range of oceanographic, atmospheric and geomagnetic instrumentation and many scientists were associated with its findings and analysis, notably Harald Sverdrup,Roger Revelle

Roger Randall Dougan Revelle (March 7, 1909 – July 15, 1991) was a scientist and scholar who was instrumental in the formative years of the University of California, San Diego and was among the early scientists to study anthropogenic global ...

and Scott Forbush

Scott Ellsworth Forbush (April 10, 1904 – April 4, 1984) was an American astronomer, physicist and geophysicist who is recognized as having laid the observational foundations for many of the central features of solar-interplanetary-terrestria ...

(who escaped the fire that destroyed the ship in 1929).

Geomagnetism

By 1930 the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism had enough data to be able to produce a much better view of Earth's magnetic field than had previously been available. The loss of ''Carnegie'' left a void in capability to collect oceanic magnetic data. By 1951 world magnetic charts were badly flawed. As a result the U.S. Navy Hydrographic Office initiated Project Magnet, an airborne program to collect magnetic data world wide. The introduction of the proton precession magnetometer enabled magnetic data collection from steel-hulled ships routine by 1957 making the extreme measures used for ''Carnegie'' unnecessary.Atmospheric electricity

The atmospheric electrical measurements carried out aboard ''Carnegie'' are of enduring and fundamental importance in understanding the balance of electric current flow in the atmosphere, the system known as the global atmospheric electric circuit. Most significantly, the results showed that the atmospheric electric field—a quantity always present away from thunderstorms—shows a characteristic daily variation which was independent of the position of the ship. This is known as the Carnegie curve.See also

*Zarya (non-magnetic ship)

''Zarya'' (russian: Заря, ''The Sunrise'') was a sailing-motor schooner built in 1952, and since 1953 used by the USSR Academy of Sciences to study Earth's magnetic field.

After the Continuation War Finland was ordered by the USSR to provid ...

* Project Magnet

References

External links

*Magnetic Survey Yacht ''Carnegie''

(''International Marine Engineering'', February 1909) {{DEFAULTSORT:Carnegie (Ship) Brigantines Research vessels of the United States 1909 ships