Cab Kaye on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

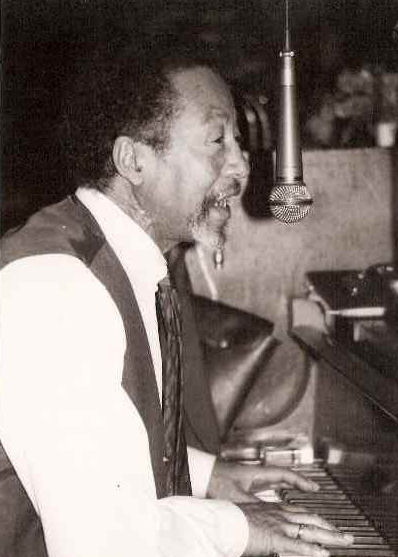

Nii-lante Augustus Kwamlah Quaye (3 September 1921 – 13 March 2000), known professionally as Cab Kaye, was an English

jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

singer and pianist of Ghanaian descent. He combined blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afr ...

, stride

Stride or STRIDE may refer to:

Computing

* STRIDE (security), spoofing, tampering, repudiation, information disclosure, denial of service, elevation of privilege

* Stride (software), a successor to the cloud-based HipChat, a corporate cloud-based ...

piano, and scat with his Ghanaian

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in Ghana–Ivory Coast border, the west, Burkina ...

heritage.

Youth

Cab Kaye, also known as Cab Quay, Cab Quaye and Kwamlah Quaye, was born onSt Giles High Street

St Giles is an area in the West End of London in the London Borough of Camden. It gets its name from the parish church of St Giles in the Fields. The combined parishes of St Giles in the Fields and St George Bloomsbury (which was carved out of ...

in Camden, London, to a musical family. His Ghanaian great-grandfather was an asafo

Asafo are traditional warrior groups in Akan culture, based on lineal descent. The word derives from , meaning war, and , meaning people. The traditional role of the Asafo companies was defence of the state. As the result of contact with European ...

warrior drummer and his grandfather, Henry Quaye, was an organist for the Methodist Mission church in the former Gold Coast

Gold Coast may refer to:

Places Africa

* Gold Coast (region), in West Africa, which was made up of the following colonies, before being established as the independent nation of Ghana:

** Portuguese Gold Coast (Portuguese, 1482–1642)

** Dutch G ...

, now called Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

. Cab's mother, Doris Balderson, sang in English music halls and his father, Caleb Jonas Quaye (born 1895 in Accra

Accra (; tw, Nkran; dag, Ankara; gaa, Ga or ''Gaga'') is the capital and largest city of Ghana, located on the southern coast at the Gulf of Guinea, which is part of the Atlantic Ocean. As of 2021 census, the Accra Metropolitan District, , ...

, Ghana), performed under the name Ernest Mope Desmond as musician, band leader, pianist and percussionist. With his blues

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afr ...

piano style, Caleb Jonas Quaye became popular around 1920 in London and Brighton

Brighton () is a seaside resort and one of the two main areas of the City of Brighton and Hove in the county of East Sussex, England. It is located south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze A ...

with his band The Five Musical Dragons in Murray's Club with, among others, Arthur Briggs, Sidney Bechet

Sidney Bechet (May 14, 1897 – May 14, 1959) was an American jazz saxophonist, clarinetist, and composer. He was one of the first important soloists in jazz, and first recorded several months before trumpeter Louis Armstrong. His erratic temp ...

and George "Bobo" Hines.

When Kaye was four months old, his father was killed in a railway accident in Blisworth

Blisworth is a village and civil parish in the West Northamptonshire, England. The West Coast Main Line, from London Euston to Manchester and Scotland, runs alongside the village partly hidden and partly on an embankment. The Grand Union Canal ...

, Northamptonshire, on 27 January 1922, on his way to perform in a concert. Kaye, his mother, and his sister Norma moved to Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, where a life insurance policy provided temporary financial support. Between the ages of nine and twelve he spent three years in hospital while a tumor in his neck was irradiated. British radiation therapy was still in its infancy, and Kaye's treatment was experimental. A scar remained on the left side of his neck.

His first instruments were timpani

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionall ...

, introduced to him by a Canadian soldier who taught him how to count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

and use the mallets. At fourteen, Kaye began to visit nightclubs where black musicians were welcome, such as The Shim Sham and The Nest; he won first prize in a song contest, a tour with the Billy Cotton

William Edward Cotton (6 May 1899 – 25 March 1969) as Billy Cotton was an English band leader and entertainer, one of the few whose orchestras survived the British dance band era. Cotton is now mainly remembered as a 1950s and 1960s radio a ...

band. During this tour, he met the African-American trombonist and tap dancer Ellis Jackson. Jackson convinced Cotton to engage Kaye as an assistant and as a singer in his band. Engaged as a tap dancer with Billy Cotton's show band in 1936, Kaye recorded his first song, "Shoe Shine Boy", under the name Cab Quay.

The war years

During 1937, Kaye played drums and percussion with Doug Swallow and his band in April, the Hal Swain Band in the summer, and Alan Green's band in September inHastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west ...

, England. Until 1940, he sang and drummed with the Ivor Kirchin Ivor Kirchin (21 January 1905 – 22 January 1997) was a British band leader, and the father of noted composer Basil Kirchin (1927–2005).

History

Born in London, Ivor Kirchin was the leader, singer, drummer, conductor and business manager fo ...

Band, with Steve Race

Stephen Russell "Steve" Race OBE (1 April 192122 June 2009) was a British composer, pianist and radio and television presenter.

Biography

Born in Lincoln, Lincolnshire, the son of a lawyer, Race learned the piano from the age of five.Spencer L ...

on piano, in the Paramount Dance Hall on Tottenham Court Road

Tottenham Court Road (occasionally abbreviated as TCR) is a major road in Central London, almost entirely within the London Borough of Camden.

The road runs from Euston Road in the north to St Giles Circus in the south; Tottenham Court Road tub ...

, London, where he was one of the only black people around. When a guest was refused entrance because of their skin colour, Kaye refused to perform. The incident led to the regular acceptance of black people, and the Paramount Dance Hall grew into a sort of "Harlem of London". After a short period with Britain's first black swing band leader, Ken Snakehips Johnson

Ken or KEN may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Ken'' (album), a 2017 album by Canadian indie rock band Destroyer.

* ''Ken'' (film), 1964 Japanese film.

* ''Ken'' (magazine), a large-format political magazine.

* Ken Masters, a main character in t ...

(and His Rhythm Swingers), Kaye played in several radio broadcasts. Shortly thereafter he joined the British Merchant Navy, which provided support services to the allies during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Three days after Kaye enlisted, Ken "Snakehips" Johnson and saxophonist David Williams were killed on 8 March 1941, when a bomb fell on the Café de Paris Café de Paris may refer to:

Establishments

*Café de Paris (London), a London nightclub

* Café de Paris, Chicago, a Chicago nightclub

* Café de Paris (restaurant), Geneva

* Café de Paris (Rome), a bar in Rome, Italy

* Café de Paris (Cubzac-les ...

nightclub in London's West End

The West End of London (commonly referred to as the West End) is a district of Central London, west of the City of London and north of the River Thames, in which many of the city's major tourist attractions, shops, businesses, government buil ...

where they were performing. Around this time Kaye's mother was also killed when her house in Portsmouth was the only house on her street to be hit by a bomb.

While on leave from the Merchant Navy, Kaye sang with Don Mario Barretto in London. His ship was hit by a torpedo in the Pacific Ocean in 1942. He was saved, but the convoy continued to be attacked by enemy ships, and during the following three nights two other ships were sunk. These experiences stayed with him for the rest of his life. En route to an Army hospital in New York he was hurt when his plane crashed before landing. While recuperating in New York, he went to concerts and played in clubs in Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street (Manhattan), 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and 110th Street (Manhattan), ...

and Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

with Roy Eldridge

David Roy Eldridge (January 30, 1911 – February 26, 1989), nicknamed "Little Jazz", was an American jazz trumpeter. His sophisticated use of harmony, including the use of tritone substitutions, his virtuosic solos exhibiting a departure from t ...

, Sandy Williams, Slam Stewart

Leroy Eliot "Slam" Stewart (September 21, 1914December 10, 1987) was an American jazz double bass player, whose trademark style was his ability to bow the bass (arco) and simultaneously hum or sing an octave higher. He was a violinist before swi ...

, Pete Brown

Peter Ronald Brown (born 25 December 1940) is an English performance poet, lyricist, and singer best known for his collaborations with Cream and Jack Bruce.Colin Larkin, ''Virgin Encyclopedia of Sixties Music'', (Muze UK Ltd, 1997), , p. 80 Bro ...

, Charlie Parker

Charles Parker Jr. (August 29, 1920 – March 12, 1955), nicknamed "Bird" or "Yardbird", was an American jazz saxophonist, band leader and composer. Parker was a highly influential soloist and leading figure in the development of bebop, a form ...

, Dizzy Gillespie

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie (; October 21, 1917 – January 6, 1993) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer, educator and singer. He was a trumpet virtuoso and improviser, building on the virtuosic style of Roy Eldridge but addi ...

, and Willie "The Lion" Smith

William Henry Joseph Bonaparte Bertholf Smith (November 23, 1893 – April 18, 1973), nicknamed "The Lion", was an American jazz and stride pianist.

Early life

William Henry Joseph Bonaparte Bertholf, known as Willie, was born in 1893 in Goshen, ...

. The story was told in a two-page article in ''Melody Maker'' (December 1942) headlined: "TORPEDOED... SHIPWRECKED... INJURED... BUT HE MET ALL THE SWING STARS!"

After his return to London, Kaye sang in February and April 1943 with clarinettist Harry Parry

Harry Owen Parry (22 January 1912 – 18 October 1956) was a Welsh jazz clarinetist and bandleader.

Biography

Parry was born in Bangor, Wales. He played cornet, tenor horn, flugelhorn, drums, and violin as a child, and began on clarinet a ...

.

After the war

In 1946, Cab Kaye sang for the British troops in Egypt and India withLeslie "Jiver" Hutchinson

Leslie George "Jiver" Hutchinson (6 March 1906 – 22 November 1959) was a Jamaican jazz trumpeter and bandleader.

Hutchinson played in the band of Bertie King in Jamaica in the 1930s, then moved to England, where he played with Happy Blake's C ...

's "All Coloured Band". After that, he performed as a singer and entertainer in Belgium. In 1947, he returned to London to sing in the bands of guitarist Vic Lewis

Victor Lewis MBE (29 July 1919 – 9 February 2009) was a British jazz guitarist and bandleader. He also enjoyed success as an artists' agent and manager.

Biography

He was born in London, England. Lewis began playing the guitar at the age o ...

, trombonist, Ted Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 191617 July 2005), often known as Ted Heath, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 to 1975. Heath a ...

, accordionist Tito Burns

Tito Burns (born Nathan Bernstein, 7 February 1921 – 23 August 2010) was a British musician and impresario, who was active in both jazz and rock and roll.

Biography Early life

The son of a cabinet maker, he was the sixth and youngest chil ...

, and the band Jazz in the Town Hall. That year, he was voted number thirteen by readers of ''Melody Maker

''Melody Maker'' was a British weekly music magazine, one of the world's earliest music weeklies; according to its publisher, IPC Media, the earliest. It was founded in 1926, largely as a magazine for dance band musicians, by Leicester-born ...

'' in their annual jazz poll.

From 1948 he performed mainly as leader of his bands, such as the Ministers of Swing with saxophonists Ronnie Scott

Ronnie may refer to:

*Ronnie (name), a unisex pet name and given name

* "Ronnie" (Four Seasons song), a song by Bob Gaudio and Bob Crewe

*"Ronnie," a song from the Metallica album '' Load''

*Ronnie Brunswijkstadion, an association football stadium ...

and Johnny Dankworth

Johnny is an English language personal name. It is usually an affectionate diminutive of the masculine given name John, but from the 16th century it has sometimes been a given name in its own right for males and, less commonly, females.

Variant ...

and pianist Denis Rose

Denis Rose (May 31, 1922, London – November 22, 1984, London) was an English jazz pianist and trumpeter. He was a longtime fixture on the London jazz scene and was an early influence on British bebop.Stan Britt, "Denis Rose". '' Grove Jazz'' onl ...

. For the new wave of London musicians from the West Indies, as well as English musicians, Kaye was an inspiration as band leader. In 1949 he played with Tommy Pollard (piano, accordion, vibes), Cecil Jacob "Flash" Winston (drums, vocals and piano) and Paul Fenhoulet's Orchestra. On 13 October 1949 Kaye recorded with clarinettist Keith Bird and The Esquire Six.

In this period he also led Cab Kaye and his Coloured Orchestra and co-led The Cabinettes with Ronnie Ball

Ronald Ball (December 22, 1927 – October 1984) was a jazz pianist, composer and arranger, born in Birmingham, England.

Biography

Ball moved to London in 1948, and in the early 1950s he worked both as a bandleader and under Ronnie Scott, Tony ...

, featuring "blues singer" Mona Baptiste

Mona Baptiste (21 June 1928 – 25 June 1993) was a Trinidad and Tobago-born singer and actress in London and Germany.Fabulous Feldman Club (100 Oxford Street, London), featuring Kaye on electric guitar. Kaye's band was, in 1948, the first musical ensemble featuring people of colour to play in Amsterdam's

In the late 1970s, Kaye moved to Amsterdam and became a member of

In the late 1970s, Kaye moved to Amsterdam and became a member of

"Cab Kaye"

in ''Who's Who of British Jazz'' * Pim Gras, "The Cab Kaye Story", ''NJA Bulletin'', No. 37 (September 2000), pp. 17–18. * Larmes. "Cab Kaye", ''Jazz Hot'', No. 573 (September 2000), p. 6. * Rainer E. Lotz, "Cab Kaye". Grove Jazz online

* Jack Martin, "Introducing Cab Kaye", in ''Anglo-German Swing Club News Sheet'', No. 10 (August 1950) (F); reprinted in Horst Ansin, Marc Dröscher, Jürgen Foth & Gerhard Klußmeier (eds): ''Anglo-German Swing Club. Als der Swing zurück nach Hamburg kam... Dokumente 1945–1952'', Hamburg: Dölling & Galitz Verlag, 2003, pp. 231–232. * Laurie Morgan, "Cab Kaye", ''Jazz at Ronnie Scott's'', No. 124 (May/June 2000), p. 12. * Obituary – ''Cadence'', v. 26, no. 7, July 2000. * Obituary – ''Jazz Journal International'', v. 53, no. 6, June 2000. * Obituary – ''NJA Bulletin'', No. 36 (June 2000), p. 18.

Obituary – ''The Times'', London, 27 March 2000

"An Exhuberant Voice in British Jazz"

Tribute – Jazz House * Val Wilmer

"Cab Kaye. Musician who enlivened the British jazz scene and rediscovered his African roots"

''The Guardian'', 21 March 2000. * Val Wilmer, Obituaries. Cab Kaye, ''Jazz Journal'', 53/6 (June 2000), pp. 15, 53. {{DEFAULTSORT:Kaye, Cab 1921 births 2000 deaths Bebop bandleaders Bebop singers 20th-century Black British male singers British male pianists Dutch jazz pianists Dutch jazz singers English jazz bandleaders English jazz pianists English jazz singers English male singers English emigrants to the Netherlands English people of Ghanaian descent Dutch people of Ghanaian descent Dutch people of English descent Ghanaian jazz musicians People from Camden Town Singers from London 20th-century pianists British male jazz musicians British Merchant Navy personnel of World War II

Concertgebouw

The Royal Concertgebouw ( nl, Koninklijk Concertgebouw, ) is a concert hall in Amsterdam, Netherlands. The Dutch term "concertgebouw" translates into English as "concert building". Its superb acoustics place it among the finest concert halls i ...

. With his All Coloured Band, featuring Dave Wilkins, Henry Shalofsky ( Hank Shaw) and Sam Walker, Cab Kaye then toured in France, Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands in 1950 and 1951.

In Paris at the end of the 1940s early 1950s, Kaye met Tadd Dameron

Tadley Ewing Peake Dameron (February 21, 1917 – March 8, 1965) was an American jazz composer, arranger, and pianist.

Biography

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Dameron was the most influential arranger of the bebop era, but also wrote charts for swi ...

, who was playing with Miles Davis

Miles Dewey Davis III (May 26, 1926September 28, 1991) was an American trumpeter, bandleader, and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music. Davis adopted a variety of music ...

. Dameron gave Kaye his first and only piano lesson. In the Club St. Germain, Kaye played with guitarist Django Reinhardt

Jean Reinhardt (23 January 1910 – 16 May 1953), known by his Romani nickname Django ( or ), was a Romani-French jazz guitarist and composer. He was one of the first major jazz talents to emerge in Europe and has been hailed as one of its most ...

, who had become more interested in bebop. Also in Paris, Kaye reunited with Roy Eldridge, who introduced him to Don Byas

Carlos Wesley "Don" Byas (October 21, 1912 – August 24, 1972) was an American jazz tenor saxophonist, associated with swing and bebop. He played with Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Art Blakey, and Dizzy Gillespie, among others, and also led ...

. The Ringside was frequented by such jazz musicians as Art Simmons

Arthur Eugene Simmons (February 5, 1926 – April 23, 2018) was an American jazz pianist.

Simmons was born in Glen White, West Virginia in February 1926. He played in a band while serving in the U.S. military in 1946, then remained in Germany aft ...

, Annie Ross

Annabelle McCauley Allan Short (25 July 193021 July 2020), known professionally as Annie Ross, was a British-American singer and actress, best known as a member of the jazz vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks & Ross.

Early life

Ross was born in Surr ...

, James Moody, Pierre Michelot

Pierre Michelot (3 March 1928 – 3 July 2005) was a French jazz double bass player and arranger.

Early life

Michelot was born in Saint-Denis, Seine-Saint-Denis, Paris on 3 March 1928. He studied piano from 1936 until 1938. He switched to playi ...

, and Babs Gonzales.

In 1950. Kaye played in the Netherlands. In March 1950, he performed in the Rotterdam club Parkzicht with jazz trumpeter Dave Wilkins from Barbados, Jamaican tenor saxophonist and clarinetist George Tyndale, Sam Walker (tenor sax), Cyril Johnson (piano), Rupert Nurse

Rupert Theophilus Nurse (26 December 1910 – 18 March 2001) was a Trinidadian musician who was influential in developing jazz and Caribbean music in Britain, particularly in the 1950s.

Life

He was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, the only c ...

(bass), Cliff Anderson (drums), and Chico Eyo (bongos). A performance with the Skymasters was recorded by the Dutch radio network AVRO

AVRO, short for Algemene Vereniging Radio Omroep ("General Association of Radio Broadcasting"), was a Dutch public broadcasting association operating within the framework of the Nederlandse Publieke Omroep system. It was the first public broad ...

in May 1950. In 1951, Kaye recorded for Astraschall Records in Germany with George Tyndale (tenor sax), Dave Wilkins (trumpet), Sam Walker (tenor sax), Cyril Johnson (piano), Owen Stephens (bass) and Aubrey Henry (drums). Kaye also regularly accompanied saxophonist Don Byas on piano in the early 1950s.

The 1950s and Hot Sauce

Between December 1950 and May 1951, Kaye's Latin American Band was booked by Lou van Rees to tour France, Germany, and the Netherlands (where Kaye met Charlie Parker). In the Netherlands, Kaye played in the newly opened Avifauna inAlphen aan den Rijn

Alphen aan den Rijn (; en, "Alphen upon Rhine" or "Alphen on the Rhine") is a city and municipality in the western Netherlands, in the province of South Holland. The city is situated on the banks of the river Oude Rijn (Old Rhine), where the r ...

, the world's first bird park.

In 1951, Kaye played a small role in the movie ''Sensation in San Remo'' directed by Georg Jacoby

Georg Jacoby (23 July 1882 – 21 February 1964) was a German film director and screenwriter.Profile

, bfi.org.uk; accessed ...

. Although the '', bfi.org.uk; accessed ...

New Musical Express

''New Musical Express'' (''NME'') is a British music, film, gaming, and culture website and brand. Founded as a newspaper in 1952, with the publication being referred to as a 'rock inkie', the NME would become a magazine that ended up as a f ...

'' announced "Cab Kaye gets Big Film Break" on 20 March 1953, the movie was unsuccessful, though he would return to films. In the Montpellier Buttery Club he organized dance contests: cha-cha, mambo

Mambo most often refers to:

*Mambo (music), a Cuban musical form

*Mambo (dance), a dance corresponding to mambo music

Mambo may also refer to:

Music

*Mambo section, a section in arrangements of some types of Afro-Caribbean music, particular ...

, and jive. In 1952, he recorded with the Gerry Moore Trio on the first of March and the Norman Burns Quintet on the seventeenth of May. From late 1952 to mid-1953, he played with drummer Tommy Jones from Liverpool and bassist/guitarist Brylo Ford from Trinidad. In 1953, Ford and Deacon Jones

David D. "Deacon" Jones (December 9, 1938 – June 3, 2013) was an American professional football player who was a defensive end in the National Football League (NFL) for the Los Angeles Rams, San Diego Chargers, and the Washington Redskins. H ...

(drums) played in a trio of that appeared in the movie ''Blood Orange

The blood orange is a variety of orange ( ''Citrus'' × ''sinensis'') (also referred to as raspberry orange) with crimson, almost blood-colored flesh.

The distinctive dark flesh color is due to the presence of anthocyanins, a family of polyp ...

'' directed by Terence Fisher

Terence Fisher (23 February 1904 – 18 June 1980) was a British film director best known for his work for Hammer Films.

He was the first to bring gothic horror alive in full colour, and the sexual overtones and explicit horror in his films, ...

.

Kaye led multi-ethnic bands usually consisting of musicians from the UK, Africa, and the West Indies. Later that year he was in the revue ''Memories of Jolson'', a musical with sixteen-year-old Shirley Bassey

Dame Shirley Veronica Bassey (; born 8 January 1937) is a Welsh singer. Best known for her career longevity, powerful voice and recording the theme songs to three James Bond films, Bassey is widely regarded as one of the most popular vocalists ...

. The show toured Scotland, but Kaye left after the first performance because he thought the show was racist. He turned to variety shows, according to ''Melody Maker

''Melody Maker'' was a British weekly music magazine, one of the world's earliest music weeklies; according to its publisher, IPC Media, the earliest. It was founded in 1926, largely as a magazine for dance band musicians, by Leicester-born ...

'' in 1953, and he founded a theatre booking agency, Black and White Productions, to book small theatre and film roles for himself and other musicians. His career as a businessman was brief, and he returned to music.

In 1953, he worked with Mary Lou Williams

Mary Lou Williams (born Mary Elfrieda Scruggs; May 8, 1910 – May 28, 1981) was an American jazz pianist, arranger, and composer. She wrote hundreds of compositions and arrangements and recorded more than one hundred records (in 78, 45, and ...

. The group included Dizzy Reece

Alphonso Son "Dizzy" Reece (born 5 January 1931) is a Jamaican-born hard bop jazz trumpeter. Reece is among a group of jazz musicians born in Jamaica which includes Bertie King, Joe Harriott, Roland Alphonso, Wilton Gaynair, Sonny Bradshaw, ...

(trumpet), Pat Burke (tenor sax), Dennis Rose

Denis Rose (May 31, 1922, London – November 22, 1984, London) was an English jazz pianist and trumpeter. He was a longtime fixture on the London jazz scene and was an early influence on British bebop.Stan Britt, "Denis Rose". '' Grove Jazz'' onl ...

(piano), Denny Coffey (bass), and Dave Smallman (bongos, congas). They accompanied dancer Josie Woods

Josie Woods (16 May 1912 – 28 June 2008) was a Black British dancer, choreographer and activist.

Early life

Woods was born Josephine Lucy Wood in Canning Town, London, in 1912. Her father, Charles Wood, was from Dominica, and her mother, Emi ...

and performed as Cab Kaye's Jazz Septet at the London Palladium

The London Palladium () is a Grade II* West End theatre located on Argyll Street, London, in the famous area of Soho. The theatre holds 2,286 seats. Of the roster of stars who have played there, many have televised performances. Between 1955 an ...

in 1953, as well as using other names. Several appearances followed, including performances with singer Billy Daniels

William Boone Daniels (September 12, 1915 – October 7, 1988) was an American singer active in the United States and Europe from the mid-1930s to 1988, notable for his hit recording of "That Old Black Magic" and his pioneering performances on e ...

and pianist Benny Payne (New Wimbledon Theatre

The New Wimbledon Theatre is situated on the Broadway, Wimbledon, London, in the London Borough of Merton. It is a Listed building, Grade II listed Edwardian era, Edwardian theatre built by the theatre lover and entrepreneur, J. B. Mulholland. B ...

, 26 July 1953).

Kaye performed in the Kurhaus

Kurhaus (German for "spa house" or "health resort") may refer to:

* Kurhaus of Baden-Baden in Germany

* Kurhaus, Wiesbaden in Germany

* Kurhaus, Meran in South Tyrol, Italy

* Kurhaus of Scheveningen in the Netherlands

* Kurhaus Bergün, a grand ho ...

at Scheveningen

Scheveningen is one of the eight districts of The Hague, Netherlands, as well as a subdistrict (''wijk'') of that city. Scheveningen is a modern seaside resort with a long, sandy beach, an esplanade, a pier, and a lighthouse. The beach is po ...

in the Netherlands in 1953. That same year, "Cab's Secret" hot sauce was sold in shops on Archer Street (East Finchley

East Finchley is an area in North London, immediately north of Hampstead Heath. Like neighbouring Muswell Hill it straddles the London Boroughs of Barnet and Haringey, with most of East Finchley falling into the London Borough of Barnet. It has ...

) in London. Although popular among Kaye's friends for many years, the sauce failed commercially. At the end of 1953, he formed the cabaret act The Two Brown Birds of Rhythm with Josie Woods. At the Ring Side club in Paris as "Kab Kay" he accompanied Eartha Kitt

Eartha Kitt (born Eartha Mae Keith; January 17, 1927 – December 25, 2008) was an American singer and actress known for her highly distinctive singing style and her 1953 recordings of "C'est si bon" and the Christmas novelty song "Santa Ba ...

on piano. In April 1954, he played the role of "Kenneth – the coloured singer" in the film ''The Man Who Loved Redheads

''The Man Who Loved Redheads'' is a 1955 British comedy film directed by Harold French and starring Moira Shearer, John Justin and Roland Culver. The film is based on the play '' Who is Sylvia?'' (1950) by Terence Rattigan, which is reputedly a ...

''. Kaye received a salary of £35 per day.

During one of his tours of England (20 September 1954), he sang with a band led by pianist Ken Moule

Kenneth John Moule (26 June 1925 – 27 January 1986) was an English jazz pianist, best known as a composer and arranger.

Biography

Moule was born in Barking, Essex, the only child of Frederick and Ethal Moule. Early childhood illness, which ...

and including Dave Usden (trumpet), Keith Barr, Roy Sidwell (tenor saxophone), Don Cooper

Donald James Cooper (born January 15, 1956) is an American former Major League Baseball (MLB) pitcher who spent parts of four seasons with the Minnesota Twins (1981–1982), Toronto Blue Jays (1983) and New York Yankees (1985). He was the pi ...

(bass), Arthur Watts (bass). and Lennie Breslaw (drums). Contracted by impresario Lou van Rees, he toured the Netherlands in 1955–1956 and performed at the Flying Dutchman club in Scheveningen

Scheveningen is one of the eight districts of The Hague, Netherlands, as well as a subdistrict (''wijk'') of that city. Scheveningen is a modern seaside resort with a long, sandy beach, an esplanade, a pier, and a lighthouse. The beach is po ...

. Van Rees had the idea to form a big band with twelve band leaders who were rarely heard on Dutch radio, including Wil Hensbergen, Max Woiski Sr. , vibraphonist Eddy Sanchez, Johnny Kraaykamp

Jan Hendrik (John) Kraaijkamp Sr. (19 April 1925 – 17 July 2011) was a Dutch Golden Calf and Louis d'Or winning actor, comedian and singer. For years, he formed a comedy team with Rijk de Gooyer. One of The Netherlands' most popular comedians, p ...

, and Wessel Ilcken

Also in 1956, Kaye played at the Sheherazade jazz club in Amsterdam's with his All Star Quintet consisting of Rob Pronk (piano), Toon van Vliet (tenor sax), Dub Dubois (bass) and drummer Wally Bishop

Wallace Bond Bishop (August 17, 1905 - January 15, 1982), better known as Wally Bishop, was an American cartoonist who drew his syndicated ''Muggs and Skeeter'' comic strip for 47 years.

Biography

Born in Normal, Illinois, he grew up in Blooming ...

. The club, nicknamed "Zade" by friends, was located in the Wagenstraat until 1962 and was a popular meeting place for jazz musicians. Later in 1956 Kaye toured Germany and played in Hamburg, Düsseldorf, and Köln

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 million ...

, followed in 1957 by a tour of England with the Eric Delaney

Eric Delaney (22 May 1924 – 14 July 2011) was an English drummer and bandleader, popular in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Career

Delaney was born in Acton, London, England. Aged 16, he won the Best Swing Drummer award and later joined the Bert ...

Band Show with Marion Williams.

Kaye performed in Cab's Quintet on the British BBC television program ''Six-Five Special

''Six-Five Special'' is a British television programme launched in February 1957 when both television and rock and roll were in their infancy in Britain.

Description

''Six-Five Special'' was the BBC's first attempt at a rock-and-roll programme. ...

'' on 31 August 1957 (season 1, episode 29) with Laurence "Laurie" Deniz (1st guitar) and his brother Joe Deniz

Francisco "Frank" Antonio Deniz (31 July 1912 – 17 July 2005) was a British jazz guitarist. He performed in London from the 1930s, and in the 1950s gave radio broadcasts. With his brothers José and Laurence he formed the Hermanos Deniz Cuban Rh ...

(guitar), Pete Blannin (bass), and Harry South

Harry Percy South (7 September 1929 – 12 March 1990) was an English jazz pianist, composer, and arranger, who moved into work for film and television.

Career

South was born in Fulham, London. He came to prominence in the 1950s, playing wi ...

(piano). Around this time Kaye also performed in '' Oh Boy!'', the first British teenage all-music show. ''Oh Boy'' was an ABC

ABC are the first three letters of the Latin script known as the alphabet.

ABC or abc may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Broadcasting

* American Broadcasting Company, a commercial U.S. TV broadcaster

** Disney–ABC Television ...

show for ITV

ITV or iTV may refer to:

ITV

*Independent Television (ITV), a British television network, consisting of:

** ITV (TV network), a free-to-air national commercial television network covering the United Kingdom, the Isle of Man, and the Channel Islan ...

, produced by Jack Good, who had produced ''Six-Five Special

''Six-Five Special'' is a British television programme launched in February 1957 when both television and rock and roll were in their infancy in Britain.

Description

''Six-Five Special'' was the BBC's first attempt at a rock-and-roll programme. ...

'' on which Kaye had appeared. That same year, Kaye was voted eleventh in ''Melody Maker''s Jazz Music Magazine Poll. Kaye appeared again on ''Six-Five Special'' on 1 March 1958 (season 1, episode 57).

In 1959, he joined the ensemble of Humphrey Lyttelton

Humphrey Richard Adeane Lyttelton (23 May 1921 – 25 April 2008), also known as Humph, was an English jazz musician and broadcaster from the Lyttelton family.

Having taught himself the trumpet at school, Lyttelton became a professional ...

in London, which led to the recording of the album ''Humph Meets Cab'' (March 1960), with his characteristic witty vocals on pieces such as "Let Love Lie Sleeping".

The ''Manchester Evening News

The ''Manchester Evening News'' (''MEN'') is a regional daily newspaper covering Greater Manchester in North West England, founded in 1868. It is published Monday–Saturday; a Sunday edition, the ''MEN on Sunday'', was launched in February 201 ...

'' announced on 25 August 1960 that the next day's BBC TV ''Jazz Session'' was to feature the Dill Quintet, the Bob Wallis

Robert Wallis (3 June 1934 – 10 January 1991) was a British jazz musician, who had a handful of chart success in the early 1960s, during the UK traditional jazz boom.

Biography

Wallis was born in Bridlington, East Riding of Yorkshire, where ...

Storyville Jazzmen, and singer Cab Kaye. In the same year Kaye came ninth in ''Melody Makers Jazz Poll.

Swinging diplomat

On 6 March 1957, theGold Coast

Gold Coast may refer to:

Places Africa

* Gold Coast (region), in West Africa, which was made up of the following colonies, before being established as the independent nation of Ghana:

** Portuguese Gold Coast (Portuguese, 1482–1642)

** Dutch G ...

became Ghana, the first sub-Saharan African country to gain its independence. Three years later, on 6 March 1960, Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An in ...

became president of the republic. For Cab Kaye, Ghana's independence was an important political symbol. Two family members in high government positions, Tawia Adamafio

Tawia Adamafio (born Joseph Tawia Adams) was a Ghanaian minister in the Nkrumah government during the first republic of Ghana.

Politics

Adamafio was a member of the Convention People's Party and rose to become its General Secretary. In 1960, he ...

and C. T. Nylander, had brought Kaye into contact with Ghanaian politics. During Nkrumah's reign, Kaye was appointed Government Entertainments Officer. Beginning in 1961, he worked at the Ghana High Commission in London as protocol officer. He played a role in getting a Ghanaian passport for Miriam Makeba

Zenzile Miriam Makeba (4 March 1932 – 9 November 2008), nicknamed Mama Africa, was a South African singer, songwriter, actress, and civil rights activist. Associated with musical genres including African popular music, Afropop, jazz, a ...

, whose South African passport had been revoked under the country's apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

regime.

He discarded the Anglicized version of his name and called himself "Kwamlah Quaye", though some newspapers missed the "h". During the day he worked in the Ghanaian High Commission and at night in Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club

Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club is a jazz club that has operated in Soho, London, since 1959.

History

The club opened on 30 October 1959 in a basement at 39 Gerrard Street in London's Soho district. It was set up and managed by musicians Ronnie Sco ...

. A farewell special ''Swinging Diplomat'' was broadcast by the BBC in August 1961. A farewell party was organized in Ronnie Scott's club.

Before leaving for Ghana, Kaye and his Kwamlah Quaye Sextetto Africana recorded "Everything Is Go", the song he had written with William "Bill" Davis. With this band he made the first recordings in which he played guitar. This group consisted of Laurence Deniz, born in Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

in 1924 to a father from Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

; Chris O'Brien, bongos, and Frank Holder, both from British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies, which resides on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first European to encounter Guiana was S ...

(now Guyana

Guyana ( or ), officially the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern mainland of South America. Guyana is an indigenous word which means "Land of Many Waters". The capital city is Georgetown. Guyana is bordered by the ...

) and served in the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF); and Chris Ajilo on claves. "Everything Is Go" was a calypso tribute to American astronaut John Glenn

John Herschel Glenn Jr. (July 18, 1921 – December 8, 2016) was an American Marine Corps aviator, engineer, astronaut, businessman, and politician. He was the third American in space, and the first American to orbit the Earth, circling ...

. On 17 February 1962 Kaye received fourth place in the ''Melody Maker'' poll of jazz musicians. He left London with plans to work for the Ghanaian Industrial Development Corporation (IDC). On arriving in Accra, he formed a duo with singer Mary Hyde

Mary Lord nee Hyde (c. 19 February 1779 – 1 December 1864) was an English Australian woman who in the period 1855 to 1859 sued the Commissioners of the City of Sydney and won compensation for the sum of over £15,600 (plus costs) for the inunda ...

, with whom he regularly performed in the Star and other hotels in Accra.

Kaye performed during a visit by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. She was queen ...

to Ghana in November 1961. As Entertainments Manager for Ghana Hotels, Kaye was less successful. Although the concerts he organized were popular, the dance competitions were less so. At the Star Hotel in 1963, he joined drummer Guy Warren

Guy Warren of Ghana, also known as Kofi Ghanaba (4 May 1923 – 22 December 2008), was a Ghanaian musician, best known as the inventor of Afro-jazz — "the reuniting of African-American jazz with its African roots" — and as a member of The T ...

(later known as "Kofi Ghanaba

Guy Warren of Ghana, also known as Kofi Ghanaba (4 May 1923 – 22 December 2008), was a Ghanaian musician, best known as the inventor of Afro-jazz — "the reuniting of African-American jazz with its African roots" — and as a member of The T ...

") and folk singer Pete Seeger

Peter Seeger (May 3, 1919 – January 27, 2014) was an American folk singer and social activist. A fixture on nationwide radio in the 1940s, Seeger also had a string of hit records during the early 1950s as a member of the Weavers, notably ...

who was on a world tour and popular in Ghana. Kaye played in Accra (including the Tip-Toe Gardens) and in Lagos

Lagos (Nigerian English: ; ) is the largest city in Nigeria and the List of cities in Africa by population, second most populous city in Africa, with a population of 15.4 million as of 2015 within the city proper. Lagos was the national ca ...

, alternating with performances in New York (at the Village Door in Long Island). On 7 August 1964, he played with Dizzy Gillespie and his quintet in the charity program O'Pataki to support African culture.

Politics

In the early 1960s the Ghanaian Ramblers Dance Band covered Kaye's highlife song "Beautiful Ghana" under the title "Work and Happiness". The song was released by Decca (West Africa) frequently played during Kwame Nkrumah's regime as part of the "Work and Happiness" political program. Nkrumah was deposed in 1966 after a military coup, leaving Kaye and other supporters of the previous regime in a difficult situation. He had to explain his political views behind the "Work and Happiness" song. His sister Norma was married to J. T. Nelson-Cole in Nigeria and offered Kaye a home base in Lagos. This was the end of his political career, but thePan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a worldwide movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous and diaspora peoples of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the movement exte ...

of Kwame Nkrumah, calling for a politically united Africa, remained one of the few political ideals he supported for the rest of his life.

Beginning in 1965 he played in New York, Europe, and Africa. He was announced in New York under the name "Nii Lante Quaye" as a special act, as he was in a flyer announcing Cab Kaye as a guest artist in the show of Ed Nixon Jr. (Nick La Tour) in St. Stephan's Methodist Church, Broadway, on 22 May 1966. The show master Cab Kaye was announced in Ghanaian flyers of this time as "MC" (Master of Ceremony) Cab Kaye. He performed regularly on Ghanaian and Nigerian radio and television: on 16 November 1966 in ''It's Time for Show Biz'' with the Spree City Stompers from Berlin; on 6 January 1967 with "the Paramount Eight Dance Band" on Ghanaian television's ''Bandstand''; and on 30 July 1967 as MC at the international pop festival in Accra. In May 1968, he performed with his nephews, the Nelson Cole brothers, in Lagos, and then touring through Nigeria. The Nelson Cole brothers were his sister Norma's sons, who formed the Soul Assembly with other artists. In 1996 Kaye played again in Lagos at the Federal Palace Hotel

The Federal Palace Hotel is a 5 star hotel with 150-rooms that overlooks the Atlantic Ocean, located in the commercial hub of Victoria Island (Nigeria), Victoria Island in Lagos. Established in 1960 as the country's premier international hotel, ...

in a program including Fela Kuti

Fela Aníkúlápó Kuti (born Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti; 15 October 1938 – 2 August 1997), also known as Abami Eda, was a Nigerian musician, bandleader, composer, political activist, and Pan-Africanist. He is regarded as the p ...

and highlife bandleader Bobby Benson

Bernard Olabinjo "Bobby" Benson (11 April 1922 – 14 May 1983) was an entertainer and musician who had considerable influence on the Nigerian music scene, introducing big band and Caribbean idioms to the Highlife style of popular West African m ...

.

After his return to England in 1970, he discovered that his daughter Terri Quaye

Terri Quaye, also Theresa (born 8 November 1940, Bodmin, England),Val Wilmer"Quaye, Terri (born 1940), singer, pianist, percussionist" The New Grove, Grove Music Online - ''The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz'', 2nd edition. Published in print Janu ...

(also known as Theresa Naa-Koshie), his eldest son Caleb Quaye

Caleb Quaye (born 9 October 1948), is an English rock guitarist and studio musician best known for his work in the 1960s and 1970s with Elton John, Mick Jagger, Pete Townshend, Paul McCartney, Hall & Oates and Ralph McTell, and also toured with ...

and his band Hookfoot

Hookfoot was a British rock band, active from 1969 to 1974. The band was formed by Caleb Quaye (guitars, piano and vocals) and three fellow DJM Records session musicians, Ian Duck (vocals, guitars and harmonica), Roger Pope (drums) and David G ...

, were more popular than he was. He began his second London career in Mike Leroy's Chez Club Cleo in Knightsbridge

Knightsbridge is a residential and retail district in central London, south of Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park. It is identified in the London Plan as one of two international retail centres in London, alongside the West End of London, West End.

...

accompanied by Clive Cooper (bass) and Cecil "Flash" Winston (drums). Kaye became a much-requested presence on the London jazz circuit. His daughter Terri, who started singing with her father and his bebop jazz band as a young girl, accompanied him at some events. Around 1973 he was accompanied by Mike Greaves (drums, percussion), Phil Bates

Philip Bates (born 30 March 1953) is an English musician who has been a member of many notable bands, including Trickster and Quill, and was the lead guitarist, songwriter and joint lead vocalist for ELO Part II from 1993 through to 1999 and the ...

(bass), and Ray Dempsey (guitar). The following year he was one of the attractions at the Black Arts Festival 1974, organized by the Commonwealth Institute

The Commonwealth Education Trust is a registered charity established in 2007 as the successor trust to the Commonwealth Institute. The trust focuses on primary and secondary education and the training of teachers and invests on educational pro ...

in London. He also made regular appearances at the BBC Club (an exclusive club for BBC employees) with Phil Bates and Tony Crombie.

Amsterdam: Cab Kaye's Jazz Piano Bar

In the late 1970s, Kaye moved to Amsterdam and became a member of

In the late 1970s, Kaye moved to Amsterdam and became a member of Buma/Stemra BUMA/STEMRA are two private organisations in the Netherlands, the Buma Association ( Dutch: ''Vereniging Buma'') and the Stemra Foundation ( Dutch: ''Stichting Stemra'') that operate as one single company that acts as the Dutch collecting society fo ...

, the Dutch copyright organization that oversaw distribution of royalties, and the Dutch Association of Professional Improvising Musicians (BIM). In Amsterdam he performed with jazz musicians such as singer Babs Gonzales, flautist Wally Shorts, trombonist Bert Koppelaar, bassist Wilbur Little

Wilbur "Doc" Little (March 5, 1928 – May 4, 1987) was an American jazz bassist known for playing hard bop and post-bop.

Little originally played piano, but switched to double bass after serving in the military. In 1949 he moved to Washington, ...

, and conductor Boy Edgar (in the Amsterdam Concertgebouw

The Royal Concertgebouw ( nl, Koninklijk Concertgebouw, ) is a concert hall in Amsterdam, Netherlands. The Dutch term "concertgebouw" translates into English as "concert building". Its superb acoustics place it among the finest concert halls i ...

). In the early years in Amsterdam, he rented an apartment from jazz saxophonist Rosa King

Rosa King (March 14, 1939 – December 12, 2000) was an American jazz and blues saxophonist and singer who made her fame in Amsterdam.

Career

King was born in Macon, Georgia, United States. During her career, she worked with Ben E. King, ...

and became known on the local jazz scene.

He opened Cab Kaye's Jazz Piano Bar in the center of Amsterdam on 1 October 1979 at Beulingstraat 9, with his Dutch wife Jeannette. When not touring Poland, Portugal, and Iceland, he performed five nights a week in his Piano Bar, a meeting place for jazz musicians. Frequent visitors included Rosa King, Slide Hampton

Locksley Wellington Hampton (April 21, 1932 – November 18, 2021) was an American jazz trombonist, composer and arranger. As his nickname implies, Hampton's main instrument was slide trombone, but he also occasionally played tuba and flugelho ...

, saxophonist Aart Gisolf, guitarist Dirk-Jan "Bubblin" Toorop, pianist David Mayer, singer Gerrie van der Klei, pianist Cameron Japp, Max Roach

Maxwell Lemuel Roach (January 10, 1924 – August 16, 2007) was an American jazz Jazz drumming, drummer and composer. A pioneer of bebop, he worked in many other styles of music, and is generally considered one of the most important drummers in h ...

, Oscar Peterson

Oscar Emmanuel Peterson (August 15, 1925 – December 23, 2007) was a Canadian virtuoso jazz pianist and composer. Considered one of the greatest jazz pianists of all time, Peterson released more than 200 recordings, won seven Grammy Awards, ...

, and Pia Beck. He gave many concerts in the Netherlands, including several with Max "Teawhistle" Teeuwisse in Den Oever

Den Oever (; in English, the ''shore, the coast'') is a village in the Dutch province of North Holland. It is a part of the municipality of Hollands Kroon, and lies about east of Den Helder.

Overview

The village was first mentioned in 1432 as " ...

and four times at the North Sea Jazz Festival

The North Sea Jazz Festival is an annual festival held each second weekend of July in the Netherlands at the Ahoy venue. It used to be in The Hague but since 2006 it has been held in Rotterdam. This is because the Statenhal where the festival w ...

. The first North Sea Jazz Festival performance was with his Cab Kaye Quartet on 16 July 1978. The second was on 10 July 1981 with Akwaba Cab Kaye and his Afro Jazz. The third was in July 1982 accompanied by Aart Gisolf and Nippy Noya

Nippy Noya (born 27 February 1946) is an Indonesian, Netherlands-based percussionist and songwriter, specialising in congas, kalimba, bongos, campana, güiro, cabasa, shekere, caxixi, triangle and the berimbau.

History

Son of Japanese Taiko d ...

, and the last was as a soloist on 10 July 1983.

Kaye regularly performed at the Victoria Hotel, Amsterdam, in the second half of the 1980s. On 10 October 1987 he participated in the Night of Hilversum

Hilversum () is a city and municipality in the province of North Holland, Netherlands. Located in the heart of the Gooi, it is the largest urban centre in that area. It is surrounded by heathland, woods, meadows, lakes, and smaller towns. Hilvers ...

, a polio charity event organized by the Rotary Club

Rotary International is one of the largest service organizations in the world. Its stated mission is to "provide service to others, promote integrity, and advance world understanding, goodwill, and peace through hefellowship of business, profe ...

, WHO

Who or WHO may refer to:

* Who (pronoun), an interrogative or relative pronoun

* Who?, one of the Five Ws in journalism

* World Health Organization

Arts and entertainment Fictional characters

* Who, a creature in the Dr. Seuss book '' Horton He ...

and UNICEF

UNICEF (), originally called the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund in full, now officially United Nations Children's Fund, is an agency of the United Nations responsible for providing Humanitarianism, humanitarian and Devel ...

. On 21 May 1988 Cab Kaye's Jazz Piano Bar closed, and he began to be heard in public much less often. His final significant performance was on 8 September 1996 at the Bimhuis

The Bimhuis is a concert hall for jazz and improvised music in Amsterdam.

With an average of 150 performances a year the Bimhuis is the main stage for these musical genres in the Netherlands. In 2017 it was also a host for the 17th edition of ...

in Amsterdam. Many musicians and jazz lovers, including Herman Openneer, Pim Gras, the Dutch jazz drummer John Engels and Rosa King, organized a birthday party for the 75-year-old pianist. He was unable to sing due to his mouth floor cancer but enthusiastically played piano with many musicians. He performed sporadically in smaller venues and privately in Amsterdam's Dapperbuurt

Dapperbuurt is a neighborhood of Amsterdam, Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title ...

. The last time he played piano (including "Jeannette You Are My Love") was on 12 March 2000 at home with Rosa King.

Private life

Although born in London, Kaye considered himself African. He was married three times, first in 1939 to Theresa Austin, a jazz singer and daughter of a sailor from Barbados. He and Theresa often performed together. The couple had two daughters,Terri Quaye

Terri Quaye, also Theresa (born 8 November 1940, Bodmin, England),Val Wilmer"Quaye, Terri (born 1940), singer, pianist, percussionist" The New Grove, Grove Music Online - ''The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz'', 2nd edition. Published in print Janu ...

(born 8 November 1940, Bodmin

Bodmin () is a town and civil parish in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is situated south-west of Bodmin Moor.

The extent of the civil parish corresponds fairly closely to that of the town so is mostly urban in character. It is bordere ...

), Tanya Quaye, and a son, Caleb Quaye

Caleb Quaye (born 9 October 1948), is an English rock guitarist and studio musician best known for his work in the 1960s and 1970s with Elton John, Mick Jagger, Pete Townshend, Paul McCartney, Hall & Oates and Ralph McTell, and also toured with ...

(born 1948, London).

He met his second wife, a Nigerian named Evelyn, in the 1960s in Ghana. They moved back to England. After a brief affair in 1973 with Sharon McGowan, he had a son, Finley Quaye

Finley Quaye (born 25 March 1974, Edinburgh, Scotland) is a Scottish musician. He won the 1997 MOBO Award for best reggae act, and the 1998 BRIT Award for Best Male Solo Artist.

Life

Finley Quaye is the son of vaudeville pianist Cab Kaye and t ...

(born 25 March 1974, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

). Kaye met his son Finley as an adult in 1997 following a concert of Finley's in the rock music venue and cultural centre Paradiso Amsterdam."Finley weeps for 'lost' dad; Pop star's grief after reunion", ''The Mirror'', 22 April 2000.

His third wife, Jeannette, was Dutch. After marrying, he settled in the Netherlands and became a Dutch citizen, living in Amsterdam. In the 1990s, he was diagnosed with floor of mouth cancer (oral cancer) and lost the ability to speak. He died at the age of 78 on 13 March 2000. He was cremated and his ashes were scattered in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

and in Accra.

Discography

As leader

* Cab Kaye and His Band, May 1951 (Astraschall) * Cab Kaye acc. by the Gerry Moore Trio, 1 March 1952 (Esquire) * Cab Kaye acc. by the Norman Burns Quintet, 17 May 1952 (Esquire) * Cab Kaye with the Ken Moule Seven, 20 September 1954 (Esquire) * Cab Kaye Trio, 23 December 1976, Today, (Riff Records, 1977) * Cab Kaye Trio, 10 July 1981, Cab Kaye Live at the North Sea Jazz Festival 1981 (Philips) * Cab Kaye live The Key, 20 August 1984 (Keytone) * Cab Kaye, The Consul of Swing – Victoria Blues, 14 March 1986 * Cab Kaye in Iceland, 18 June 1986 (Icelandic national radio) * Cab Kaye in Iceland & Africa on Ice, October 1996 (Icelandic national radio)As sideman

* Billy Cotton and His Band, 27 August 1936 (Regal Zonophone) * Billy Cotton & His Orchestra, ''A Nice Cup of Tea Volume 2'', recorded 1936–1941 (Vocalion, 2001) * Jazz at the Town Hall Ensemble, 30 March 1948 (Esquire

Esquire (, ; abbreviated Esq.) is usually a courtesy title.

In the United Kingdom, ''esquire'' historically was a title of respect accorded to men of higher social rank, particularly members of the landed gentry above the rank of gentlema ...

)

* Keith Bird and The Esquire Six, 13 October 1949 (Esquire)

* Humphrey Lyttelton Quartet, 15 March 1960, ''Humph Meets Cab'' (Columbia)

* Humphrey Lyttelton and His Band, 30 March 1960 (Philips)

* Kwamlah Quaye Sextetto Africana (Melodisc, 1962)

* Kwamlah Quaye Sextetto Africana (Melodisc, 1962)

* Billy Cotton & His Band, ''Things I Love About the 40s'', 16 June 1998

* Ginger Johnson & Friends, ''London Is the Place for Me'', volume 4, 2006 (Honest Jon's)

* Billy Cotton & His Band, ''Wakey Wakey!'', 6 September 2005 (Living Era)

* Humphrey Lyttelton and His Quartet Band featuring Cab Kaye, High Class 1959–60, 24 May 2011

* Kenny Ball's Jazzmen and Cab Kaye and His Quartet (Jazz Club – A BBC Programme, Complete as Broadcast in 1961), 28 September 2013 (DigitalGramophone, 2013)

References

Further reading

* Ian Carr, Digby Fairweather, Brian Priestley, ''The Rough Guide to Jazz'', Rough Guides Ltd, 2005, p. 430. . * John Chilton"Cab Kaye"

in ''Who's Who of British Jazz'' * Pim Gras, "The Cab Kaye Story", ''NJA Bulletin'', No. 37 (September 2000), pp. 17–18. * Larmes. "Cab Kaye", ''Jazz Hot'', No. 573 (September 2000), p. 6. * Rainer E. Lotz, "Cab Kaye". Grove Jazz online

* Jack Martin, "Introducing Cab Kaye", in ''Anglo-German Swing Club News Sheet'', No. 10 (August 1950) (F); reprinted in Horst Ansin, Marc Dröscher, Jürgen Foth & Gerhard Klußmeier (eds): ''Anglo-German Swing Club. Als der Swing zurück nach Hamburg kam... Dokumente 1945–1952'', Hamburg: Dölling & Galitz Verlag, 2003, pp. 231–232. * Laurie Morgan, "Cab Kaye", ''Jazz at Ronnie Scott's'', No. 124 (May/June 2000), p. 12. * Obituary – ''Cadence'', v. 26, no. 7, July 2000. * Obituary – ''Jazz Journal International'', v. 53, no. 6, June 2000. * Obituary – ''NJA Bulletin'', No. 36 (June 2000), p. 18.

Obituary – ''The Times'', London, 27 March 2000

"An Exhuberant Voice in British Jazz"

Tribute – Jazz House * Val Wilmer

"Cab Kaye. Musician who enlivened the British jazz scene and rediscovered his African roots"

''The Guardian'', 21 March 2000. * Val Wilmer, Obituaries. Cab Kaye, ''Jazz Journal'', 53/6 (June 2000), pp. 15, 53. {{DEFAULTSORT:Kaye, Cab 1921 births 2000 deaths Bebop bandleaders Bebop singers 20th-century Black British male singers British male pianists Dutch jazz pianists Dutch jazz singers English jazz bandleaders English jazz pianists English jazz singers English male singers English emigrants to the Netherlands English people of Ghanaian descent Dutch people of Ghanaian descent Dutch people of English descent Ghanaian jazz musicians People from Camden Town Singers from London 20th-century pianists British male jazz musicians British Merchant Navy personnel of World War II