Coronavirus Proteins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Coronaviruses are a group of related

Scottish virologist

Scottish virologist

Coronaviruses are large, roughly spherical particles with unique surface projections. Their size is highly variable with average diameters of 80 to 120 nm. Extreme sizes are known from 50 to 200 nm in diameter. The total

Coronaviruses are large, roughly spherical particles with unique surface projections. Their size is highly variable with average diameters of 80 to 120 nm. Extreme sizes are known from 50 to 200 nm in diameter. The total  The spikes are the most distinguishing feature of coronaviruses and are responsible for the corona- or halo-like surface. On average a coronavirus particle has 74 surface spikes. Each

The spikes are the most distinguishing feature of coronaviruses and are responsible for the corona- or halo-like surface. On average a coronavirus particle has 74 surface spikes. Each  S1 proteins are the most critical components in terms of infection. They are also the most variable components as they are responsible for host cell specificity. They possess two major domains named N-terminal domain (S1-NTD) and C-terminal domain (S1-CTD), both of which serve as the receptor-binding domains. The NTDs recognize and bind sugars on the surface of the host cell. An exception is the MHV NTD that binds to a protein receptor

S1 proteins are the most critical components in terms of infection. They are also the most variable components as they are responsible for host cell specificity. They possess two major domains named N-terminal domain (S1-NTD) and C-terminal domain (S1-CTD), both of which serve as the receptor-binding domains. The NTDs recognize and bind sugars on the surface of the host cell. An exception is the MHV NTD that binds to a protein receptor

Coronaviruses contain a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome. The

Coronaviruses contain a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome. The

Infection begins when the viral spike protein attaches to its complementary host cell receptor. After attachment, a

Infection begins when the viral spike protein attaches to its complementary host cell receptor. After attachment, a

A number of the nonstructural proteins coalesce to form a multi-protein replicase-transcriptase complex (RTC). The main replicase-transcriptase protein is the

A number of the nonstructural proteins coalesce to form a multi-protein replicase-transcriptase complex (RTC). The main replicase-transcriptase protein is the

''Transcription'' – The other important function of the complex is to transcribe the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the

''Transcription'' – The other important function of the complex is to transcribe the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the

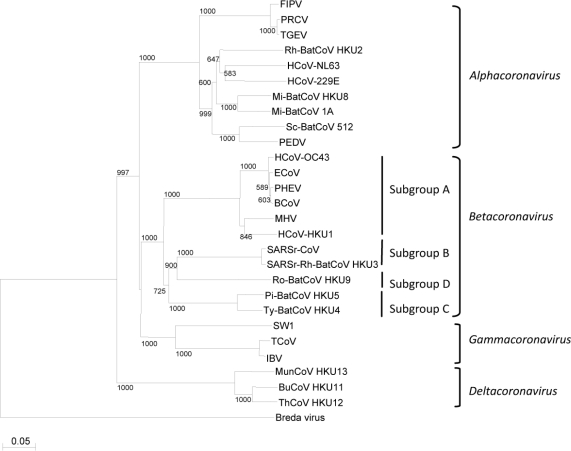

Coronaviruses form the subfamily ''Orthocoronavirinae,'' which is one of two sub-families in the family ''

Coronaviruses form the subfamily ''Orthocoronavirinae,'' which is one of two sub-families in the family ''

The

The

Coronaviruses vary significantly in risk factor. Some can kill more than 30% of those infected, such as

Coronaviruses vary significantly in risk factor. Some can kill more than 30% of those infected, such as

''(Novel coronavirus—Status report: A new case of confirmed infection)'' 12 May 2013, social-sante.gouv.fr In addition, cases of human-to-human transmission were reported by the Ministry of Health in

RNA viruses

''Orthornavirae'' is a kingdom of viruses that have genomes made of ribonucleic acid (RNA), those genomes encoding an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). The RdRp is used to transcribe the viral RNA genome into messenger RNA (mRNA) and to repli ...

that cause diseases in mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s and birds. In humans and birds, they cause respiratory tract infection

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are infectious diseases involving the respiratory tract. An infection of this type usually is further classified as an upper respiratory tract infection (URI or URTI) or a lower respiratory tract infection (LRI ...

s that can range from mild to lethal. Mild illnesses in humans include some cases of the common cold

The common cold or the cold is a viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory tract that primarily affects the respiratory mucosa of the nose, throat, sinuses, and larynx. Signs and symptoms may appear fewer than two days after exposu ...

(which is also caused by other viruses, predominantly rhinovirus

The rhinovirus (from the grc, ῥίς, rhis "nose", , romanized: "of the nose", and the la, vīrus) is the most common viral infectious agent in humans and is the predominant cause of the common cold. Rhinovirus infection proliferates in tem ...

es), while more lethal varieties can cause SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV or SARS-CoV-1), the first identified strain of the SARS coronavirus species, ''sever ...

, MERS

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a viral respiratory infection caused by ''Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus'' (MERS-CoV). Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. Typical symptoms include fever, cough, ...

and COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by a virus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The first known case was COVID-19 pandemic in Hubei, identified in Wuhan, China, in December ...

, which is causing the ongoing pandemic. In cows and pigs they cause diarrhea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin wi ...

, while in mice they cause hepatitis

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver tissue. Some people or animals with hepatitis have no symptoms, whereas others develop yellow discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice), poor appetite, vomiting, tiredness, abdominal pa ...

and encephalomyelitis

Encephalomyelitis is inflammation of the brain and spinal cord. Various types of encephalomyelitis include:

* ''Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis'' or ''postinfectious encephalomyelitis'', a demyelinating disease of the brain and spinal cord, p ...

.

Coronaviruses constitute the subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end subfamily botanical names with "-oideae", and zoologi ...

''Orthocoronavirinae'', in the family ''Coronaviridae

''Coronaviridae'' is a family of enveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses which infect amphibians, birds, and mammals. The group includes the subfamilies ''Letovirinae'' and ''Orthocoronavirinae;'' the members of the latter are known as coronav ...

'', order ''Nidovirales

''Nidovirales'' is an order of enveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses which infect vertebrates and invertebrates. Host organisms include mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, arthropods, molluscs, and helminths. The order includes the fami ...

'' and realm ''Riboviria

''Riboviria'' is a realm of viruses that includes all viruses that use a homologous RNA-dependent polymerase for replication. It includes RNA viruses that encode an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, as well as reverse-transcribing viruses (with eithe ...

''. They are enveloped virus

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes.

Numerous human pathogenic viruses in circulation are encase ...

es with a positive-sense single-stranded RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

and a nucleocapsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

of helical symmetry. The genome size

Genome size is the total amount of DNA contained within one copy of a single complete genome. It is typically measured in terms of mass in picograms (trillionths (10−12) of a gram, abbreviated pg) or less frequently in daltons, or as the total ...

of coronaviruses ranges from approximately 26 to 32 kilobase

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s, one of the largest among RNA viruses. They have characteristic club-shaped spikes

The SPIKES protocol is a method used in clinical medicine to break bad news to patients and families. As receiving bad news can cause distress and anxiety, clinicians need to deliver the news carefully. By using the SPIKES method for introducing a ...

that project from their surface, which in electron micrograph

A micrograph or photomicrograph is a photograph or digital image taken through a microscope or similar device to show a magnified image of an object. This is opposed to a macrograph or photomacrograph, an image which is also taken on a mi ...

s create an image reminiscent of the stellar corona

A corona ( coronas or coronae) is the outermost layer of a star's atmosphere. It consists of plasma.

The Sun's corona lies above the chromosphere and extends millions of kilometres into outer space. It is most easily seen during a total solar ...

, from which their name derives.

Etymology

The name "coronavirus" is derived from Latin ''corona

Corona (from the Latin for 'crown') most commonly refers to:

* Stellar corona, the outer atmosphere of the Sun or another star

* Corona (beer), a Mexican beer

* Corona, informal term for the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which causes the COVID-19 di ...

'', meaning "crown" or "wreath", itself a borrowing from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''korṓnē'', "garland, wreath". The name was coined by June Almeida

June Dalziel Almeida (5 October 1930 – 1 December 2007) was a Scottish virologist, a pioneer in virus imaging, identification, and diagnosis. Her skills in electron microscopy earned her an international reputation.

In 1964, Almeida was rec ...

and David Tyrrell who first observed and studied human coronaviruses. The word was first used in print in 1968 by an informal group of virologists in the journal ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

'' to designate the new family of viruses. The name refers to the characteristic appearance of virion

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

s (the infective form of the virus) by electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

, which have a fringe of large, bulbous surface projections creating an image reminiscent of the solar corona

A corona ( coronas or coronae) is the outermost layer of a star's atmosphere. It consists of plasma.

The Sun's corona lies above the chromosphere and extends millions of kilometres into outer space. It is most easily seen during a total solar e ...

or halo. This morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

is created by the viral spike peplomer

In virology, a spike protein or peplomer protein is a protein that forms a large structure known as a spike or peplomer projecting from the surface of an enveloped virus. as cited in The proteins are usually glycoproteins that form dimers or ...

s, which are proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

on the surface of the virus.

The scientific name ''Coronavirus'' was accepted as a genus name by the International Committee for the Nomenclature of Viruses (later renamed International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) authorizes and organizes the taxonomic classification of and the nomenclatures for viruses. The ICTV has developed a universal taxonomic scheme for viruses, and thus has the means to app ...

) in 1971. As the number of new species increased, the genus was split into four genera, namely ''Alphacoronavirus

Alphacoronaviruses (Alpha-CoV) are members of the first of the four genera (''Alpha''-, '' Beta-'', '' Gamma-'', and '' Delta-'') of coronaviruses. They are positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses that infect mammals, including humans. They ...

'', ''Betacoronavirus

''Betacoronavirus'' (β-CoVs or Beta-CoVs) is one of four genera (''Alpha''-, ''Beta-'', '' Gamma-'', and '' Delta-'') of coronaviruses. Member viruses are enveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses that infect mammals (of which humans are part). ...

'', ''Deltacoronavirus

''Deltacoronavirus'' (Delta-CoV) is one of the four Genus, genera (''Alphacoronavirus, Alpha-'', ''Betacoronavirus, Beta-'', ''Gammacoronavirus, Gamma-'', and ''Delta-'') of coronaviruses. It is in the subfamily ''Orthocoronavirinae'' of the fa ...

'', and ''Gammacoronavirus

''Gammacoronavirus'' (Gamma-CoV) is one of the four genera (''Alpha''-, '' Beta-'', ''Gamma-'', and '' Delta-'') of coronaviruses. It is in the subfamily ''Orthocoronavirinae'' of the family ''Coronaviridae''. They are enveloped, positive-sense ...

'' in 2009. The common name coronavirus is used to refer to any member of the subfamily ''Orthocoronavirinae''. As of 2020, 45 species are officially recognised.

History

The earliest reports of a coronavirus infection in animals occurred in the late 1920s, when an acute respiratory infection of domesticated chickens emerged in North America. Arthur Schalk and M.C. Hawn in 1931 made the first detailed report which described a new respiratory infection of chickens inNorth Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the Native Americans in the United States, indigenous Dakota people, Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north a ...

. The infection of new-born chicks was characterized by gasping and listlessness with high mortality rates of 40–90%. Leland David Bushnell and Carl Alfred Brandly isolated the virus that caused the infection in 1933. The virus was then known as infectious bronchitis virus

''Avian coronavirus'' is a species of virus from the genus '' Gammacoronavirus'' that infects birds; since 2018, all gammacoronaviruses which infect birds have been classified as this single species. The strain of avian coronavirus previously kn ...

(IBV). Charles D. Hudson and Fred Robert Beaudette cultivated the virus for the first time in 1937. The specimen came to be known as the Beaudette strain. In the late 1940s, two more animal coronaviruses, JHM that causes brain disease (murine encephalitis) and mouse hepatitis virus

Murine coronavirus (M-CoV) is a virus in the genus ''Betacoronavirus'' that infects mice. Belonging to the subgenus ''Embecovirus'', murine coronavirus strains are enterotropic or polytropic. Enterotropic strains include mouse hepatitis virus (M ...

(MHV) that causes hepatitis in mice were discovered. It was not realized at the time that these three different viruses were related.

Human coronaviruses were discovered in the 1960s using two different methods in the United Kingdom and the United States. E.C. Kendall, Malcolm Bynoe, and David Tyrrell working at the Common Cold Unit

The Common Cold Unit (CCU) or Common Cold Research Unit (CCRU) was a unit of the British Medical Research Council which undertook laboratory and epidemiological research on the common cold between 1946 and 1989 and produced 1,006 papers. The Comm ...

of the British Medical Research Council collected a unique common cold

The common cold or the cold is a viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory tract that primarily affects the respiratory mucosa of the nose, throat, sinuses, and larynx. Signs and symptoms may appear fewer than two days after exposu ...

virus designated B814 in 1961. The virus could not be cultivated using standard techniques which had successfully cultivated rhinovirus

The rhinovirus (from the grc, ῥίς, rhis "nose", , romanized: "of the nose", and the la, vīrus) is the most common viral infectious agent in humans and is the predominant cause of the common cold. Rhinovirus infection proliferates in tem ...

es, adenoviruses

Adenoviruses (members of the family ''Adenoviridae'') are medium-sized (90–100 nm), nonenveloped (without an outer lipid bilayer) viruses with an icosahedral nucleocapsid containing a double-stranded DNA genome. Their name derives from thei ...

and other known common cold viruses. In 1965, Tyrrell and Bynoe successfully cultivated the novel virus by serially passing it through organ culture

Organ culture is a development from tissue culture methods of research, the organ culture is able to accurately model functions of an organ in various states and conditions by the use of the actual ''in vitro'' organ itself.

Parts of an organ or ...

of human embryonic trachea

The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a Cartilage, cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all air-breathing animals with lungs. The trachea extends ...

. The new cultivating method was introduced to the lab by Bertil Hoorn. The isolated virus when intranasally inoculated into volunteers caused a cold and was inactivated by ether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups. They have the general formula , where R and R′ represent the alkyl or aryl groups. Ethers can again be c ...

which indicated it had a lipid envelope. Dorothy Hamre

Dorothy may refer to:

*Dorothy (given name), a list of people with that name.

Arts and entertainment

Characters

*Dorothy Gale, protagonist of ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' by L. Frank Baum

* Ace (''Doctor Who'') or Dorothy, a character playe ...

and John Procknow at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

isolated a novel cold from medical students in 1962. They isolated and grew the virus in kidney tissue culture

Tissue culture is the growth of tissues or cells in an artificial medium separate from the parent organism. This technique is also called micropropagation. This is typically facilitated via use of a liquid, semi-solid, or solid growth medium, su ...

, designating it 229E. The novel virus caused a cold in volunteers and, like B814, was inactivated by ether.

Scottish virologist

Scottish virologist June Almeida

June Dalziel Almeida (5 October 1930 – 1 December 2007) was a Scottish virologist, a pioneer in virus imaging, identification, and diagnosis. Her skills in electron microscopy earned her an international reputation.

In 1964, Almeida was rec ...

at St Thomas' Hospital

St Thomas' Hospital is a large NHS teaching hospital in Central London, England. It is one of the institutions that compose the King's Health Partners, an academic health science centre. Administratively part of the Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foun ...

in London, collaborating with Tyrrell, compared the structures of IBV, B814 and 229E in 1967. Using electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

the three viruses were shown to be morphologically related by their general shape and distinctive club-like spikes

The SPIKES protocol is a method used in clinical medicine to break bad news to patients and families. As receiving bad news can cause distress and anxiety, clinicians need to deliver the news carefully. By using the SPIKES method for introducing a ...

. A research group at the National Institute of Health

The National Institutes of Health, commonly referred to as NIH (with each letter pronounced individually), is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. It was founded in the late 1 ...

the same year was able to isolate another member of this new group of viruses using organ culture and named one of the samples OC43 (OC for organ culture). Like B814, 229E, and IBV, the novel cold virus OC43 had distinctive club-like spikes when observed with the electron microscope.

The IBV-like novel cold viruses were soon shown to be also morphologically related to the mouse hepatitis virus. This new group of viruses were named coronaviruses after their distinctive morphological appearance. Human coronavirus 229E

''Human coronavirus 229E'' (''HCoV-229E'') is a species of coronavirus which infects humans and bats. It is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to the APN receptor. Along with Human coro ...

and human coronavirus OC43

Human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43) is a member of the species ''Betacoronavirus 1'', which infects humans and cattle. The infecting coronavirus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus that enters its host cell by binding to ...

continued to be studied in subsequent decades. The coronavirus strain B814 was lost. It is not known which present human coronavirus it was. Other human coronaviruses have since been identified, including SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1; or Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, SARS-CoV) is a strain of coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the respiratory illness responsible for t ...

in 2003, HCoV NL63 in 2003, HCoV HKU1 in 2004, MERS-CoV

''Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus'' (''MERS-CoV''), or EMC/2012 ( HCoV-EMC/2012), is the virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). It is a species of coronavirus which infects humans, bats, and camels. The ...

in 2013, and SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), the respiratory illness responsible for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had a ...

in 2019. There have also been a large number of animal coronaviruses identified since the 1960s.''''

Microbiology

Structure

Coronaviruses are large, roughly spherical particles with unique surface projections. Their size is highly variable with average diameters of 80 to 120 nm. Extreme sizes are known from 50 to 200 nm in diameter. The total

Coronaviruses are large, roughly spherical particles with unique surface projections. Their size is highly variable with average diameters of 80 to 120 nm. Extreme sizes are known from 50 to 200 nm in diameter. The total molecular mass

The molecular mass (''m'') is the mass of a given molecule: it is measured in daltons (Da or u). Different molecules of the same compound may have different molecular masses because they contain different isotopes of an element. The related quanti ...

is on average 40,000 kDa

The dalton or unified atomic mass unit (symbols: Da or u) is a non-SI unit of mass widely used in physics and chemistry. It is defined as of the mass of an unbound neutral atom of carbon-12 in its nuclear and electronic ground state and at re ...

. They are enclosed in an envelope embedded with a number of protein molecules. The lipid bilayer envelope, membrane proteins, and nucleocapsid protect the virus when it is outside the host cell.

The viral envelope

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes.

Numerous human pathogenic viruses in circulation are encase ...

is made up of a lipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many vir ...

in which the membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

(M), envelope

An envelope is a common packaging item, usually made of thin, flat material. It is designed to contain a flat object, such as a letter or card.

Traditional envelopes are made from sheets of paper cut to one of three shapes: a rhombus, a shor ...

(E) and spike

Spike, spikes, or spiking may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Books

* ''The Spike'' (novel), a novel by Arnaud de Borchgrave

* ''The Spike'' (book), a nonfiction book by Damien Broderick

* ''The Spike'', a starship in Peter F. Hamilto ...

(S) structural proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respond ...

are anchored. The molar ratio of E:S:M in the lipid bilayer is approximately 1:20:300. The E and M protein are the structural proteins that combined with the lipid bilayer to shape the viral envelope and maintain its size. S proteins are needed for interaction with the host cells. But human coronavirus NL63

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, an ...

is peculiar in that its M protein has the binding site for the host cell, and not its S protein. The diameter of the envelope is 85 nm. The envelope of the virus in electron micrographs appears as a distinct pair of electron-dense shells (shells that are relatively opaque to the electron beam used to scan the virus particle).

The M protein is the main structural protein of the envelope that provides the overall shape and is a type III membrane protein. It consists of 218 to 263 Amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

residues and forms a layer 7.8 nm thick. It has three domains, a short N-terminal

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

ectodomain

An ectodomain is the domain of a membrane protein that extends into the extracellular space (the space outside a cell). Ectodomains are usually the parts of proteins that initiate contact with surfaces, which leads to signal transduction.A notable ...

, a triple-spanning transmembrane domain

A transmembrane domain (TMD) is a membrane-spanning protein domain. TMDs generally adopt an alpha helix topological conformation, although some TMDs such as those in porins can adopt a different conformation. Because the interior of the lipid bil ...

, and a C-terminal

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When the protein is ...

endodomain. The C-terminal domain forms a matrix-like lattice that adds to the extra-thickness of the envelope. Different species can have either ''N''- or ''O''-linked glycan

The terms glycans and polysaccharides are defined by IUPAC as synonyms meaning "compounds consisting of a large number of monosaccharides linked glycosidically". However, in practice the term glycan may also be used to refer to the carbohydrate p ...

s in their protein amino-terminal domain. The M protein is crucial during the assembly, budding

Budding or blastogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction in which a new organism develops from an outgrowth or bud due to cell division at one particular site. For example, the small bulb-like projection coming out from the yeast cell is know ...

, envelope formation, and pathogenesis stages of the virus lifecycle.

The E proteins are minor structural proteins and highly variable in different species. There are only about 20 copies of the E protein molecule in a coronavirus particle. They are 8.4 to 12 kDa in size and are composed of 76 to 109 amino acids. They are integral proteins (i.e. embedded in the lipid layer) and have two domains namely a transmembrane domain and an extramembrane C-terminal domain. They are almost fully α-helical, with a single α-helical transmembrane domain, and form pentameric (five-molecular) ion channel

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by gating the flow of io ...

s in the lipid bilayer. They are responsible for virion assembly, intracellular trafficking and morphogenesis (budding).

The spikes are the most distinguishing feature of coronaviruses and are responsible for the corona- or halo-like surface. On average a coronavirus particle has 74 surface spikes. Each

The spikes are the most distinguishing feature of coronaviruses and are responsible for the corona- or halo-like surface. On average a coronavirus particle has 74 surface spikes. Each spike

Spike, spikes, or spiking may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Books

* ''The Spike'' (novel), a novel by Arnaud de Borchgrave

* ''The Spike'' (book), a nonfiction book by Damien Broderick

* ''The Spike'', a starship in Peter F. Hamilto ...

is about 20 nm long and is composed of a trimer of the Sprotein. The S protein is in turn composed of an S1 and S2 subunit. The homotrimeric Sprotein is a class I fusion protein

Membrane fusion proteins (not to be confused with chimeric or fusion proteins) are proteins that cause fusion of biological membranes. Membrane fusion is critical for many biological processes, especially in eukaryotic development and viral entry ...

which mediates the receptor binding

In biochemistry and pharmacology, receptors are chemical structures, composed of protein, that receive and transduce signals that may be integrated into biological systems. These signals are typically chemical messengers which bind to a recepto ...

and membrane fusion

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

between the virus and host cell. The S1 subunit forms the head of the spike and has the receptor-binding domain (RBD). The S2 subunit forms the stem which anchors the spike in the viral envelope and on protease activation enables fusion. The two subunits remain noncovalently linked as they are exposed on the viral surface until they attach to the host cell membrane. In a functionally active state, three S1 are attached to two S2 subunits. The subunit complex is split into individual subunits when the virus binds and fuses with the host cell under the action of proteases

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the for ...

such as cathepsin

Cathepsins (Ancient Greek ''kata-'' "down" and ''hepsein'' "boil"; abbreviated CTS) are proteases ( enzymes that degrade proteins) found in all animals as well as other organisms. There are approximately a dozen members of this family, which are d ...

family and transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) of the host cell.

S1 proteins are the most critical components in terms of infection. They are also the most variable components as they are responsible for host cell specificity. They possess two major domains named N-terminal domain (S1-NTD) and C-terminal domain (S1-CTD), both of which serve as the receptor-binding domains. The NTDs recognize and bind sugars on the surface of the host cell. An exception is the MHV NTD that binds to a protein receptor

S1 proteins are the most critical components in terms of infection. They are also the most variable components as they are responsible for host cell specificity. They possess two major domains named N-terminal domain (S1-NTD) and C-terminal domain (S1-CTD), both of which serve as the receptor-binding domains. The NTDs recognize and bind sugars on the surface of the host cell. An exception is the MHV NTD that binds to a protein receptor carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1

Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (biliary glycoprotein) (CEACAM1) also known as CD66a (Cluster of Differentiation 66a), is a human glycoprotein, and a member of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) gene family.

Function ...

(CEACAM1). S1-CTDs are responsible for recognizing different protein receptors such as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is an enzyme that can be found either attached to the membrane of cells (mACE2) in the intestines, kidney, testis, gallbladder, and heart or in a soluble form (sACE2). Both membrane bound and soluble ACE2 a ...

(ACE2), aminopeptidase N

Membrane alanyl aminopeptidase () also known as alanyl aminopeptidase (AAP) or aminopeptidase N (AP-N) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ANPEP gene.

Function

Aminopeptidase N is located in the small-intestinal and renal microvilla ...

(APN), and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4).

A subset of coronaviruses (specifically the members of betacoronavirus

''Betacoronavirus'' (β-CoVs or Beta-CoVs) is one of four genera (''Alpha''-, ''Beta-'', '' Gamma-'', and '' Delta-'') of coronaviruses. Member viruses are enveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses that infect mammals (of which humans are part). ...

subgroup A) also has a shorter spike-like surface protein called hemagglutinin esterase

Hemagglutinin esterase (HEs) is a glycoprotein that certain enveloped viruses possess and use as an invading mechanism. HEs helps in the Viral entry, attachment and destruction of certain sialic acid receptors that are found on the Host (biology ...

(HE). The HE proteins occur as homodimers composed of about 400 amino acid residues and are 40 to 50 kDa in size. They appear as tiny surface projections of 5 to 7 nm long embedded in between the spikes. They help in the attachment to and detachment from the host cell.

Inside the envelope, there is the nucleocapsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

, which is formed from multiple copies of the nucleocapsid (N) protein, which are bound to the positive-sense single-stranded RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

genome in a continuous Bead

A bead is a small, decorative object that is formed in a variety of shapes and sizes of a material such as stone, bone, shell, glass, plastic, wood, or pearl and with a small hole for threading or stringing. Beads range in size from under ...

s-on-a-string type conformation. N protein is a phosphoprotein

A phosphoprotein is a protein that is posttranslationally modified by the attachment of either a single phosphate group, or a complex molecule such as 5'-phospho-DNA, through a phosphate group. The target amino acid is most often serine, threonin ...

of 43 to 50 kDa in size, and is divided into three conserved domains. The majority of the protein is made up of domains 1 and 2, which are typically rich in arginine

Arginine is the amino acid with the formula (H2N)(HN)CN(H)(CH2)3CH(NH2)CO2H. The molecule features a guanidino group appended to a standard amino acid framework. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid is deprotonated (−CO2−) and both the am ...

s and lysine

Lysine (symbol Lys or K) is an α-amino acid that is a precursor to many proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −C ...

s. Domain 3 has a short carboxy terminal end and has a net negative charge due to excess of acidic over basic amino acid residues.

Genome

Coronaviruses contain a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome. The

Coronaviruses contain a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome. The genome size

Genome size is the total amount of DNA contained within one copy of a single complete genome. It is typically measured in terms of mass in picograms (trillionths (10−12) of a gram, abbreviated pg) or less frequently in daltons, or as the total ...

for coronaviruses ranges from 26.4 to 31.7 kilobases. The genome size is one of the largest among RNA viruses. The genome has a 5′ methylated cap and a 3′ polyadenylated tail.

The genome organization for a coronavirus is 5′-leader-UTR-replicase (ORF1ab)-spike (S)-envelope (E)-membrane (M)-nucleocapsid (N)- 3′UTR-poly (A) tail. The open reading frame

In molecular biology, open reading frames (ORFs) are defined as spans of DNA sequence between the start and stop codons. Usually, this is considered within a studied region of a prokaryotic DNA sequence, where only one of the six possible readin ...

s 1a and 1b, which occupy the first two-thirds of the genome, encode the replicase polyprotein (pp1ab). The replicase polyprotein self cleaves to form 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1–nsp16).

The later reading frames encode the four major structural proteins: spike

Spike, spikes, or spiking may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Books

* ''The Spike'' (novel), a novel by Arnaud de Borchgrave

* ''The Spike'' (book), a nonfiction book by Damien Broderick

* ''The Spike'', a starship in Peter F. Hamilto ...

, envelope

An envelope is a common packaging item, usually made of thin, flat material. It is designed to contain a flat object, such as a letter or card.

Traditional envelopes are made from sheets of paper cut to one of three shapes: a rhombus, a shor ...

, membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

, and nucleocapsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

. Interspersed between these reading frames are the reading frames for the accessory proteins. The number of accessory proteins and their function is unique depending on the specific coronavirus.

Replication cycle

Cell entry

Infection begins when the viral spike protein attaches to its complementary host cell receptor. After attachment, a

Infection begins when the viral spike protein attaches to its complementary host cell receptor. After attachment, a protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

of the host cell cleaves Cleaves is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Henry B. Cleaves

*Jessica Cleaves (1948–2014), American singer-songwriter

*Margaret Cleaves (1848–1917), American physician

*Mateen Cleaves (born 1977), American basketball player ...

and activates the receptor-attached spike protein. Depending on the host cell protease available, cleavage and activation allows the virus to enter the host cell by endocytosis

Endocytosis is a cellular process in which substances are brought into the cell. The material to be internalized is surrounded by an area of cell membrane, which then buds off inside the cell to form a vesicle containing the ingested material. E ...

or direct fusion of the viral envelope with the host membrane.

Genome translation

On entry into thehost cell

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasitic, a mutualistic, or a commensalist ''guest'' (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with nourishment and shelter. Examples include a ...

, the virus particle is uncoated, and its genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

enters the cell cytoplasm. The coronavirus RNA genome has a 5′ methylated cap and a 3′ polyadenylated tail, which allows it to act like a messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

and be directly translated by the host cell's ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

s. The host ribosomes translate the initial overlapping open reading frames

In molecular biology, open reading frames (ORFs) are defined as spans of DNA sequence between the start and stop codons. Usually, this is considered within a studied region of a prokaryotic DNA sequence, where only one of the six possible readin ...

ORF1a

ORF1ab (also ORF1a/b) refers collectively to two open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1a and ORF1b, that are conserved in the genomes of nidoviruses, a group of viruses that includes coronaviruses. The genes express large polyproteins that undergo pro ...

and ORF1b

ORF1ab (also ORF1a/b) refers collectively to two open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1a and ORF1b, that are conserved in the genomes of nidoviruses, a group of viruses that includes coronaviruses. The genes express large polyproteins that undergo p ...

of the virus genome into two large overlapping polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab.

The larger polyprotein pp1ab is a result of a -1 ribosomal frameshift caused by a slippery sequence

A slippery sequence is a small section of codon nucleotide sequences (usually UUUAAAC) that controls the rate and chance of ribosomal frameshifting. A slippery sequence causes a faster ribosomal transfer which in turn can cause the reading ribosome ...

(UUUAAAC) and a downstream RNA pseudoknot at the end of open reading frame ORF1a. The ribosomal frameshift allows for the continuous translation of ORF1a followed by ORF1b.

The polyproteins have their own proteases

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the for ...

, PLpro (nsp3) and 3CLpro (nsp5), which cleave the polyproteins at different specific sites. The cleavage of polyprotein pp1ab yields 16 nonstructural proteins (nsp1 to nsp16). Product proteins include various replication proteins such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) or RNA replicase is an enzyme that catalyzes the replication of RNA from an RNA template. Specifically, it catalyzes synthesis of the RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template. This is in contrast to t ...

(nsp12), RNA helicase

Helicases are a class of enzymes thought to be vital to all organisms. Their main function is to unpack an organism's genetic material. Helicases are motor proteins that move directionally along a nucleic acid phosphodiester backbone, separating ...

(nsp13), and exoribonuclease

An exoribonuclease is an exonuclease ribonuclease, which are enzymes that degrade RNA by removing terminal nucleotides from either the 5' end or the 3' end of the RNA molecule. Enzymes that remove nucleotides from the 5' end are called ''5'-3' e ...

(nsp14).

Replicase-transcriptase

A number of the nonstructural proteins coalesce to form a multi-protein replicase-transcriptase complex (RTC). The main replicase-transcriptase protein is the

A number of the nonstructural proteins coalesce to form a multi-protein replicase-transcriptase complex (RTC). The main replicase-transcriptase protein is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) or RNA replicase is an enzyme that catalyzes the replication of RNA from an RNA template. Specifically, it catalyzes synthesis of the RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template. This is in contrast to t ...

(RdRp). It is directly involved in the replication and transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

of RNA from an RNA strand. The other nonstructural proteins in the complex assist in the replication and transcription process. The exoribonuclease

An exoribonuclease is an exonuclease ribonuclease, which are enzymes that degrade RNA by removing terminal nucleotides from either the 5' end or the 3' end of the RNA molecule. Enzymes that remove nucleotides from the 5' end are called ''5'-3' e ...

nonstructural protein, for instance, provides extra fidelity to replication by providing a proofreading

Proofreading is the reading of a galley proof or an electronic copy of a publication to find and correct reproduction errors of text or art. Proofreading is the final step in the editorial cycle before publication.

Professional

Traditional ...

function which the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase lacks.

''Replication'' – One of the main functions of the complex is to replicate the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the synthesis

Synthesis or synthesize may refer to:

Science Chemistry and biochemistry

*Chemical synthesis, the execution of chemical reactions to form a more complex molecule from chemical precursors

** Organic synthesis, the chemical synthesis of organ ...

of negative-sense genomic RNA from the positive-sense genomic RNA. This is followed by the replication of positive-sense genomic RNA from the negative-sense genomic RNA.

''Transcription'' – The other important function of the complex is to transcribe the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the

''Transcription'' – The other important function of the complex is to transcribe the viral genome. RdRp directly mediates the synthesis

Synthesis or synthesize may refer to:

Science Chemistry and biochemistry

*Chemical synthesis, the execution of chemical reactions to form a more complex molecule from chemical precursors

** Organic synthesis, the chemical synthesis of organ ...

of negative-sense subgenomic RNA molecules from the positive-sense genomic RNA. This process is followed by the transcription of these negative-sense subgenomic RNA molecules to their corresponding positive-sense mRNAs

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

. The subgenomic mRNAs form a "nested set

In a naive set theory, a nested set is a set containing a chain of subsets, forming a hierarchical structure, like Matryoshka doll, Russian dolls.

It is used as reference-concept in all hierarchy, scientific hierarchy definitions, and many techn ...

" which have a common 5'-head and partially duplicate 3'-end.

''Recombination'' – The replicase-transcriptase complex is also capable of genetic recombination

Genetic recombination (also known as genetic reshuffling) is the exchange of genetic material between different organisms which leads to production of offspring with combinations of traits that differ from those found in either parent. In eukaryo ...

when at least two viral genomes are present in the same infected cell. RNA recombination appears to be a major driving force in determining genetic variability within a coronavirus species, the capability of a coronavirus species to jump from one host to another and, infrequently, in determining the emergence of novel coronaviruses. The exact mechanism of recombination in coronaviruses is unclear, but likely involves template switching during genome replication.

Assembly and release

The replicated positive-sense genomic RNA becomes the genome of the progeny viruses. The mRNAs are gene transcripts of the last third of the virus genome after the initial overlapping reading frame. These mRNAs are translated by the host's ribosomes into the structural proteins and many accessory proteins. RNA translation occurs inside theendoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

. The viral structural proteins S, E, and M move along the secretory pathway into the Golgi intermediate compartment. There, the Mproteins direct most protein-protein interactions required for the assembly of viruses following its binding to the nucleocapsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

. Progeny viruses are then released from the host cell by exocytosis

Exocytosis () is a form of active transport and bulk transport in which a cell transports molecules (e.g., neurotransmitters and proteins) out of the cell ('' exo-'' + ''cytosis''). As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use o ...

through secretory vesicles. Once released the viruses can infect other host cells.

Transmission

Infected carriers are able to shed viruses into the environment. The interaction of the coronavirus spike protein with its complementarycell receptor

In biochemistry and pharmacology, receptors are chemical structures, composed of protein, that receive and transduce signals that may be integrated into biological systems. These signals are typically chemical messengers which bind to a recept ...

is central in determining the tissue tropism

Tissue tropism is the range of cells and tissues of a host that support growth of a particular pathogen, such as a virus, bacterium or parasite.

Some bacteria and viruses have a broad tissue tropism and can infect many types of cells and tissues. ...

, infectivity

In epidemiology, infectivity is the ability of a pathogen to establish an infection. More specifically, infectivity is a pathogen's capacity for horizontal transmission — that is, how frequently it spreads among hosts that are not in a parent� ...

, and species range of the released virus. Coronaviruses mainly target epithelial cells

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. It is a thin, continuous, protective layer of compactly packed cells with a little intercellula ...

.'''' They are transmitted from one host to another host, depending on the coronavirus species, by either an aerosol

An aerosol is a suspension (chemistry), suspension of fine solid particles or liquid Drop (liquid), droplets in air or another gas. Aerosols can be natural or Human impact on the environment, anthropogenic. Examples of natural aerosols are fog o ...

, fomite

A fomite () or fomes () is any inanimate object that, when contaminated with or exposed to infectious agents (such as pathogenic bacteria, viruses or fungi), can transfer disease to a new host.

Transfer of pathogens by fomites

A fomite is any ina ...

, or fecal-oral route.

Human coronaviruses infect the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract

The respiratory tract is the subdivision of the respiratory system involved with the process of respiration in mammals. The respiratory tract is lined with respiratory epithelium as respiratory mucosa.

Air is breathed in through the nose to th ...

, while animal coronaviruses generally infect the epithelial cells of the digestive tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans a ...

.'''' SARS coronavirus

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1; or Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, SARS-CoV) is a strain of coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the respiratory illness responsible for th ...

, for example, infects the human epithelial cells of the lungs via an aerosol route by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is an enzyme that can be found either attached to the membrane of cells (mACE2) in the intestines, kidney, testis, gallbladder, and heart or in a soluble form (sACE2). Both membrane bound and soluble ACE2 a ...

(ACE2) receptor. Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus

Transmissible gastroenteritis virus or Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) is a coronavirus which infects pigs. It is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to the APN recept ...

(TGEV) infects the pig epithelial cells of the digestive tract via a fecal-oral route by binding to the Alanine aminopeptidase

Membrane alanyl aminopeptidase () also known as alanyl aminopeptidase (AAP) or aminopeptidase N (AP-N) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ANPEP gene.

Function

Aminopeptidase N is located in the small-intestinal and renal microvilla ...

(APN) receptor.

Classification

Coronaviruses form the subfamily ''Orthocoronavirinae,'' which is one of two sub-families in the family ''

Coronaviruses form the subfamily ''Orthocoronavirinae,'' which is one of two sub-families in the family ''Coronaviridae

''Coronaviridae'' is a family of enveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses which infect amphibians, birds, and mammals. The group includes the subfamilies ''Letovirinae'' and ''Orthocoronavirinae;'' the members of the latter are known as coronav ...

,'' order ''Nidovirales

''Nidovirales'' is an order of enveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses which infect vertebrates and invertebrates. Host organisms include mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, arthropods, molluscs, and helminths. The order includes the fami ...

,'' and realm ''Riboviria

''Riboviria'' is a realm of viruses that includes all viruses that use a homologous RNA-dependent polymerase for replication. It includes RNA viruses that encode an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, as well as reverse-transcribing viruses (with eithe ...

.'' They are divided into the four genera: ''Alphacoronavirus'', ''Betacoronavirus'', ''Gammacoronavirus'' and ''Deltacoronavirus''. Alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses infect mammals, while gammacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses primarily infect birds.'

* Genus: ''Alphacoronavirus

Alphacoronaviruses (Alpha-CoV) are members of the first of the four genera (''Alpha''-, '' Beta-'', '' Gamma-'', and '' Delta-'') of coronaviruses. They are positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses that infect mammals, including humans. They ...

'';

** Species: ''Alphacoronavirus 1

''Alphacoronavirus 1'' is a species of coronavirus that infects cats, dogs and pigs. It includes the virus strains feline coronavirus, canine coronavirus, and transmissible gastroenteritis virus.' It is an Viral envelope, enveloped, positive-s ...

'' (TGEV

Transmissible gastroenteritis virus or Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) is a coronavirus which infects pigs. It is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to the APN rece ...

, Feline coronavirus

Feline coronavirus (FCoV) is a positive-stranded RNA virus that infects cats worldwide. It is a coronavirus of the species ''Alphacoronavirus 1'' which includes canine coronavirus (CCoV) and porcine transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGE ...

, Canine coronavirus

Canine coronavirus (CCoV) is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which is a member of the species ''Alphacoronavirus 1.'' It causes a highly contagious intestinal disease worldwide in dogs. The infecting virus enters its hos ...

), ''Human coronavirus 229E

''Human coronavirus 229E'' (''HCoV-229E'') is a species of coronavirus which infects humans and bats. It is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to the APN receptor. Along with Human coro ...

'', ''Human coronavirus NL63

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, an ...

'', '' Miniopterus bat coronavirus 1'', '' Miniopterus bat coronavirus HKU8'', ''Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus

''Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus'' (PED virus or PEDV) is a coronavirus that infects the cells lining the small intestine of a pig, causing porcine epidemic diarrhoea, a condition of severe diarrhea and dehydration. Older hogs mostly get sick a ...

'', '' Rhinolophus bat coronavirus HKU2'', '' Scotophilus bat coronavirus 512''

* Genus ''Betacoronavirus

''Betacoronavirus'' (β-CoVs or Beta-CoVs) is one of four genera (''Alpha''-, ''Beta-'', '' Gamma-'', and '' Delta-'') of coronaviruses. Member viruses are enveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses that infect mammals (of which humans are part). ...

'';

** Species: ''Betacoronavirus 1

''Betacoronavirus 1'' is a species of coronavirus which infects humans and cattle. The infecting virus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus and is a member of the genus ''Betacoronavirus'' and subgenus ''Embecovirus.'' Like ...

'' ( ''Bovine Coronavirus'', ''Human coronavirus OC43

Human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43) is a member of the species ''Betacoronavirus 1'', which infects humans and cattle. The infecting coronavirus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus that enters its host cell by binding to ...

''), ''Hedgehog coronavirus 1

''Hedgehog coronavirus 1'' is a mammalian Group C '' Betacoronavirus'', a positive-sense RNA virus, discovered in European hedgehogs (''Erinaceus europaeus'') from Germany and first described in 2014.

Most ''Betacoronavirus'' clade c viruses are ...

,'' ''Human coronavirus HKU1

''Human coronavirus HKU1'' (''HCoV-HKU1'') is a species of coronavirus in humans and animals. It causes an upper respiratory disease with symptoms of the common cold, but can advance to pneumonia and bronchiolitis. It was first discovered in Ja ...

'', ''Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus

''Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus'' (''MERS-CoV''), or EMC/2012 ( HCoV-EMC/2012), is the virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). It is a species of coronavirus which infects humans, bats, and camels. Th ...

,'' ''Murine coronavirus

Murine coronavirus (M-CoV) is a virus in the genus ''Betacoronavirus'' that infects mice. Belonging to the subgenus ''Embecovirus'', murine coronavirus strains are enterotropic or polytropic. Enterotropic strains include mouse hepatitis virus (M ...

'', ''Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5

''Pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5'' (''Bat-CoV HKU5'') is an enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA mammalian Group 2 '' Betacoronavirus'' discovered in Japanese ''Pipistrellus'' in Hong Kong. This strain of coronavirus is closely relat ...

'', ''Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9

''Rousettus bat coronavirus HKU9'' (''HKU9-1'') is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA mammalian Group 2 ''Betacoronavirus'' discovered in ''Rousettus'' bats in China in 2011. This strain of coronavirus is closely related to the EM ...

'', ''Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus

''Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus'' (SARSr-CoV or SARS-CoV)The terms ''SARSr-CoV'' and ''SARS-CoV'' are sometimes used interchangeably, especially prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV-2. This may cause confusion when some ...

'' (''SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1; or Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, SARS-CoV) is a strain of coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the respiratory illness responsible for t ...

'', ''SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), the respiratory illness responsible for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had a ...

''), ''Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4

''Tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4'' (''Bat-CoV HKU4'') is an enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus mammalian Group 2 ''Betacoronavirus'' that has been found to be genetically related to the '' Middle East respiratory syndrome-rela ...

''

* Genus ''Gammacoronavirus

''Gammacoronavirus'' (Gamma-CoV) is one of the four genera (''Alpha''-, '' Beta-'', ''Gamma-'', and '' Delta-'') of coronaviruses. It is in the subfamily ''Orthocoronavirinae'' of the family ''Coronaviridae''. They are enveloped, positive-sense ...

'';

** Species: ''Avian coronavirus

''Avian coronavirus'' is a species of virus from the genus ''Gammacoronavirus'' that infects birds; since 2018, all gammacoronaviruses which infect birds have been classified as this single species. The strain of avian coronavirus previously kno ...

,'' '' Beluga whale coronavirus SW1''

* Genus ''Deltacoronavirus

''Deltacoronavirus'' (Delta-CoV) is one of the four Genus, genera (''Alphacoronavirus, Alpha-'', ''Betacoronavirus, Beta-'', ''Gammacoronavirus, Gamma-'', and ''Delta-'') of coronaviruses. It is in the subfamily ''Orthocoronavirinae'' of the fa ...

''

** Species: '' Bulbul coronavirus HKU11'', ''Porcine'' ''coronavirus HKU15''

Origin

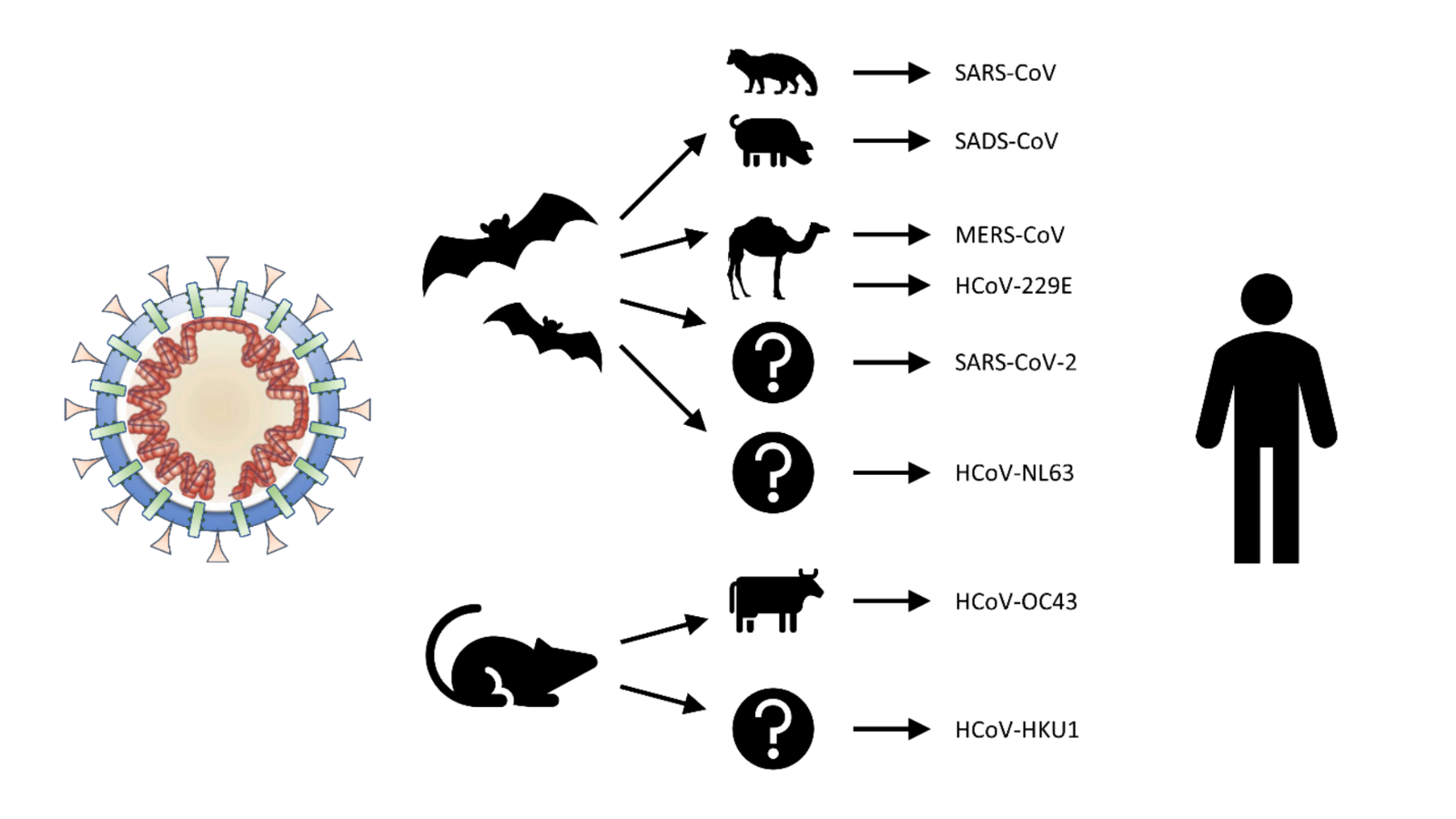

The

The most recent common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

(MRCA) of all coronaviruses is estimated to have existed as recently as 8000 BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

, although some models place the common ancestor as far back as 55 million years or more, implying long term coevolution with bat and avian species. The most recent common ancestor of the alphacoronavirus line has been placed at about 2400 BCE, of the betacoronavirus line at 3300 BCE, of the gammacoronavirus line at 2800 BCE, and the deltacoronavirus line at about 3000 BCE. Bats and birds, as warm-blooded

Warm-blooded is an informal term referring to animal species which can maintain a body temperature higher than their environment. In particular, homeothermic species maintain a stable body temperature by regulating metabolic processes. The onl ...

flying vertebrates, are an ideal natural reservoir

In infectious disease ecology and epidemiology, a natural reservoir, also known as a disease reservoir or a reservoir of infection, is the population of organisms or the specific environment in which an infectious pathogen naturally lives and rep ...

for the coronavirus gene pool (with bats the reservoir for alphacoronaviruses and betacoronavirusand birds the reservoir for gammacoronaviruses and deltacoronaviruses). The large number and global range of bat and avian species that host viruses have enabled extensive evolution and dissemination of coronaviruses.

Many human coronaviruses have their origin in bats. The human coronavirus NL63 shared a common ancestor with a bat coronavirus (ARCoV.2) between 1190 and 1449 CE. The human coronavirus 229E shared a common ancestor with a bat coronavirus (GhanaGrp1 Bt CoV) between 1686 and 1800 CE. More recently, alpaca

The alpaca (''Lama pacos'') is a species of South American camelid mammal. It is similar to, and often confused with, the llama. However, alpacas are often noticeably smaller than llamas. The two animals are closely related and can successfu ...

coronavirus and human coronavirus 229E diverged sometime before 1960. MERS-CoV emerged in humans from bats through the intermediate host of camels. MERS-CoV, although related to several bat coronavirus species, appears to have diverged from these several centuries ago. The most closely related bat coronavirus and SARS-CoV diverged in 1986. The ancestors of SARS-CoV first infected leaf-nose bats of the genus ''Hipposideridae

The Hipposideridae are a family of bats commonly known as the Old World leaf-nosed bats. While it has often been seen as a subfamily, Hipposiderinae, of the family Rhinolophidae, it is now more generally classified as its own family.Simmons, 20 ...

''; subsequently, they spread to horseshoe bats in the species '' Rhinolophidae'', then to Asian palm civet

The Asian palm civet (''Paradoxurus hermaphroditus''), also called common palm civet, toddy cat and musang, is a viverrid native to South and Southeast Asia. Since 2008, it is IUCN Red Listed as Least Concern as it accommodates to a broad range ...

s, and finally to humans.

Unlike other betacoronaviruses, bovine coronavirus

Bovine coronavirus (BCV or BCoV) is a coronavirus which is a member of the species ''Betacoronavirus 1''. The infecting virus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to the N-acetyl-9-O ...

of the species ''Betacoronavirus 1

''Betacoronavirus 1'' is a species of coronavirus which infects humans and cattle. The infecting virus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus and is a member of the genus ''Betacoronavirus'' and subgenus ''Embecovirus.'' Like ...

'' and subgenus ''Embecovirus

''Embecovirus'' is a subgenus of coronaviruses in the genus ''Betacoronavirus''. The viruses in this subgenus, unlike other coronaviruses, have a hemagglutinin esterase (HE) gene. The viruses in the subgenus were previously known as group 2a coro ...

'' is thought to have originated in rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are na ...

s and not in bats. In the 1790s, equine coronavirus diverged from the bovine coronavirus after a cross-species jump. Later in the 1890s, human coronavirus OC43 diverged from bovine coronavirus after another cross-species spillover event. It is speculated that the flu pandemic of 1890 may have been caused by this spillover event, and not by the influenza virus

''Orthomyxoviridae'' (from Greek ὀρθός, ''orthós'' 'straight' + μύξα, ''mýxa'' 'mucus') is a family of negative-sense RNA viruses. It includes seven genera: ''Alphainfluenzavirus'', ''Betainfluenzavirus'', '' Gammainfluenzavirus'', ...

, because of the related timing, neurological symptoms, and unknown causative agent of the pandemic. Besides causing respiratory infections, human coronavirus OC43 is also suspected of playing a role in neurological diseases

A neurological disorder is any disorder of the nervous system. Structural, biochemical or electrical abnormalities in the brain, spinal cord or other nerves can result in a range of symptoms. Examples of symptoms include paralysis, muscle weak ...

. In the 1950s, the human coronavirus OC43 began to diverge into its present genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

s. Phylogenetically, mouse hepatitis virus (''Murine coronavirus

Murine coronavirus (M-CoV) is a virus in the genus ''Betacoronavirus'' that infects mice. Belonging to the subgenus ''Embecovirus'', murine coronavirus strains are enterotropic or polytropic. Enterotropic strains include mouse hepatitis virus (M ...

''), which infects the mouse's liver and central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all par ...

, is related to human coronavirus OC43 and bovine coronavirus. Human coronavirus HKU1, like the aforementioned viruses, also has its origins in rodents.

Infection in humans

Coronaviruses vary significantly in risk factor. Some can kill more than 30% of those infected, such as

Coronaviruses vary significantly in risk factor. Some can kill more than 30% of those infected, such as MERS-CoV

''Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus'' (''MERS-CoV''), or EMC/2012 ( HCoV-EMC/2012), is the virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). It is a species of coronavirus which infects humans, bats, and camels. The ...

, and some are relatively harmless, such as the common cold. Coronaviruses can cause colds with major symptoms, such as fever, and a sore throat

Sore throat, also known as throat pain, is pain or irritation of the throat. Usually, causes of sore throat include

* viral infections

* group A streptococcal infection (GAS) bacterial infection

* pharyngitis (inflammation of the throat)

* tonsi ...

from swollen adenoid

In anatomy, the adenoid, also known as the pharyngeal tonsil or nasopharyngeal tonsil, is the superior-most of the tonsils. It is a mass of lymphatic tissue located behind the nasal cavity, in the roof of the nasopharynx, where the nose blends ...

s. Coronaviruses can cause pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

(either direct viral pneumonia

Viral pneumonia is a pneumonia caused by a virus. Pneumonia is an infection that causes inflammation in one or both of the lungs. The pulmonary alveoli fill with fluid or pus making it difficult to breathe. Pneumonia can be caused by bacteria, vir ...

or secondary bacterial pneumonia

Bacterial pneumonia is a type of pneumonia caused by bacterial infection.

Types

Gram-positive

''Streptococcus pneumoniae'' () is the most common bacterial cause of pneumonia in all age groups except newborn infants. ''Streptococcus pneumoniae'' ...

) and bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

(either direct viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis). The human coronavirus discovered in 2003, SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1; or Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, SARS-CoV) is a strain of coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the respiratory illness responsible for t ...

, which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV or SARS-CoV-1), the first identified strain of the SARS coronavirus species, ''seve ...

(SARS), has a unique pathogenesis because it causes both upper and lower respiratory tract infection

Lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) is a term often used as a synonym for pneumonia but can also be applied to other types of infection including lung abscess and acute bronchitis. Symptoms include shortness of breath, weakness, fever, coug ...

s.

Six species of human coronaviruses are known, with one species subdivided into two different strains, making seven strains of human coronaviruses altogether.

Four human coronaviruses produce symptoms that are generally mild, even though it is contended they might have been more aggressive in the past:

#Human coronavirus OC43

Human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43) is a member of the species ''Betacoronavirus 1'', which infects humans and cattle. The infecting coronavirus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus that enters its host cell by binding to ...

(HCoV-OC43), β-CoV

#Human coronavirus HKU1

''Human coronavirus HKU1'' (''HCoV-HKU1'') is a species of coronavirus in humans and animals. It causes an upper respiratory disease with symptoms of the common cold, but can advance to pneumonia and bronchiolitis. It was first discovered in Ja ...

(HCoV-HKU1), β-CoV

#Human coronavirus 229E

''Human coronavirus 229E'' (''HCoV-229E'') is a species of coronavirus which infects humans and bats. It is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to the APN receptor. Along with Human coro ...

(HCoV-229E), α-CoV

#Human coronavirus NL63