Copper Smelting on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a chemical reducing agent to decompose the ore, driving off other elements as gases or

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a chemical reducing agent to decompose the ore, driving off other elements as gases or

Smelting involves more than just melting the metal out of its ore. Most ores are the chemical compound of the metal and other elements, such as oxygen (as an

Smelting involves more than just melting the metal out of its ore. Most ores are the chemical compound of the metal and other elements, such as oxygen (as an

After tin and lead, the next metal smelted appears to have been copper. How the discovery came about is debated. Campfires are about 200 °C short of the temperature needed, so some propose that the first smelting of copper may have occurred in pottery kilns. The development of copper smelting in the Andes, which is believed to have occurred independently of the

After tin and lead, the next metal smelted appears to have been copper. How the discovery came about is debated. Campfires are about 200 °C short of the temperature needed, so some propose that the first smelting of copper may have occurred in pottery kilns. The development of copper smelting in the Andes, which is believed to have occurred independently of the

, and dates to 930 BCE (

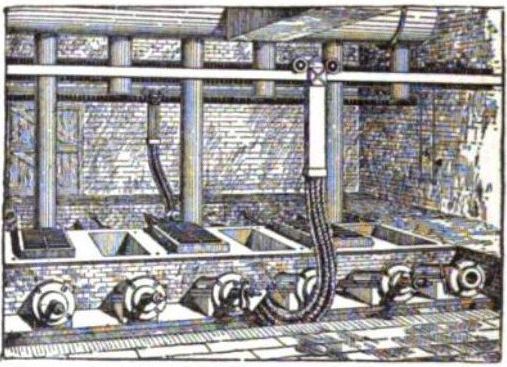

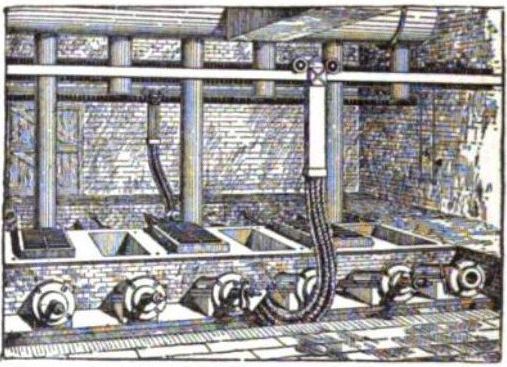

The ores of base metals are often sulfides. In recent centuries, reverberatory furnaces have been used to keep the charge being smelted separate from the fuel. Traditionally, they were used for the first step of smelting: forming two liquids, one an oxide slag containing most of the impurities, and the other a sulfide matte containing the valuable metal sulfide and some impurities. Such "reverb" furnaces are today about 40 meters long, 3 meters high and 10 meters wide. Fuel is burned at one end to melt the dry sulfide concentrates (usually after partial roasting) which are fed through openings in the roof of the furnace. The slag floats over the heavier matte and is removed and discarded or recycled. The sulfide matte is then sent to the converter. The precise details of the process vary from one furnace to another depending on the mineralogy of the orebody.

While reverberatory furnaces produced slags containing very little copper, they were relatively energy inefficient and off-gassed a low concentration of

The ores of base metals are often sulfides. In recent centuries, reverberatory furnaces have been used to keep the charge being smelted separate from the fuel. Traditionally, they were used for the first step of smelting: forming two liquids, one an oxide slag containing most of the impurities, and the other a sulfide matte containing the valuable metal sulfide and some impurities. Such "reverb" furnaces are today about 40 meters long, 3 meters high and 10 meters wide. Fuel is burned at one end to melt the dry sulfide concentrates (usually after partial roasting) which are fed through openings in the roof of the furnace. The slag floats over the heavier matte and is removed and discarded or recycled. The sulfide matte is then sent to the converter. The precise details of the process vary from one furnace to another depending on the mineralogy of the orebody.

While reverberatory furnaces produced slags containing very little copper, they were relatively energy inefficient and off-gassed a low concentration of

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a chemical reducing agent to decompose the ore, driving off other elements as gases or

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a chemical reducing agent to decompose the ore, driving off other elements as gases or slag

Slag is a by-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and used metals. Broadly, it can be classified as ferrous (by-products of processing iron and steel), ferroalloy (by-product of ferroalloy production) or non-ferrous/base metals (by-prod ...

and leaving the metal base behind. The reducing agent is commonly a fossil fuel

A fossil fuel is a hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the remains of dead plants and animals that is extracted and burned as a fuel. The main fossil fuels are coal, oil, and natural gas. Fossil fuels m ...

source of carbon, such as coke—or, in earlier times, charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

. The oxygen in the ore binds to carbon at high temperatures due to the lower potential energy of the bonds in carbon dioxide (). Smelting most prominently takes place in a blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

to produce pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with silic ...

, which is converted into steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

.

The carbon source acts as a chemical reactant to remove oxygen from the ore, yielding the purified metal element as a product. The carbon source is oxidized in two stages. First, the carbon (C) combusts with oxygen (O2) in the air to produce carbon monoxide (CO). Second, the carbon monoxide reacts with the ore (e.g. Fe2O3) and removes one of its oxygen atoms, releasing carbon dioxide (). After successive interactions with carbon monoxide, all of the oxygen in the ore will be removed, leaving the raw metal element (e.g. Fe). As most ores are impure, it is often necessary to use a flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport ph ...

, such as limestone (or dolomite), to remove the accompanying rock gangue as slag. This calcination reaction also frequently emits carbon dioxide.

Plants for the electrolytic reduction of aluminium are also generally referred to as aluminium smelters

Aluminium (aluminum in American and Canadian English) is a chemical element with the symbol Al and atomic number 13. Aluminium has a density lower than those of other common metals, at approximately one third that of steel. It has ...

.

Process

Smelting involves more than just melting the metal out of its ore. Most ores are the chemical compound of the metal and other elements, such as oxygen (as an

Smelting involves more than just melting the metal out of its ore. Most ores are the chemical compound of the metal and other elements, such as oxygen (as an oxide

An oxide () is a chemical compound that contains at least one oxygen atom and one other element in its chemical formula. "Oxide" itself is the dianion of oxygen, an O2– (molecular) ion. with oxygen in the oxidation state of −2. Most of the E ...

), sulfur (as a sulfide

Sulfide (British English also sulphide) is an inorganic anion of sulfur with the chemical formula S2− or a compound containing one or more S2− ions. Solutions of sulfide salts are corrosive. ''Sulfide'' also refers to chemical compounds lar ...

), or carbon and oxygen together (as a carbonate). To extract the metal, workers must make these compounds undergo a chemical reaction. Smelting therefore consists of using suitable reducing substances that combine with those oxidizing elements to free the metal.

Roasting

In the case of sulfides and carbonates, a process called "roasting

Roasting is a cooking method that uses dry heat where hot air covers the food, cooking it evenly on all sides with temperatures of at least from an open flame, oven, or other heat source. Roasting can enhance the flavor through caramelization ...

" removes the unwanted carbon or sulfur, leaving an oxide, which can be directly reduced. Roasting is usually carried out in an oxidizing environment. A few practical examples:

* Malachite, a common ore of copper, is primarily copper carbonate hydroxide Cu2(CO3)(OH)2. This mineral undergoes thermal decomposition to 2CuO, CO2, and H2O in several stages between 250 °C and 350 °C. The carbon dioxide and water are expelled into the atmosphere, leaving copper(II) oxide, which can be directly reduced to copper as described in the following section titled ''Reduction''.

* Galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It cryst ...

, the most common mineral of lead, is primarily lead sulfide (PbS). The sulfide is oxidized to a sulfite (PbSO3), which thermally decomposes into lead oxide and sulfur dioxide gas. (PbO and SO2) The sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a toxic gas responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is released naturally by volcanic activ ...

is expelled (like the carbon dioxide in the previous example), and the lead oxide is reduced as below.

Reduction

Reduction is the final, high-temperature step in smelting, in which the oxide becomes the elemental metal. A reducing environment (often provided by carbon monoxide, made by incomplete combustion in an air-starved furnace) pulls the final oxygen atoms from the raw metal. The required temperature varies over a very large range, both in absolute terms and in terms of the melting point of the base metal. Examples: *Iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of whic ...

becomes metallic iron at roughly 1250 °C (2282 °F or 1523.15 K), almost 300 degrees ''below'' iron's melting point of 1538 °C (2800.4 °F or 1811.15 K).

* Mercuric oxide becomes vaporous mercury near 550 °C (1022 °F or 823.15 K), almost 600 degrees ''above'' mercury's melting point of -38 °C (-36.4 °F or 235.15 K).

Flux and slag can provide a secondary service after the reduction step is complete: they provide a molten cover on the purified metal, preventing contact with oxygen while still hot enough to readily oxidize. This prevents impurities from forming in the metal.

Fluxes

Metal workers use fluxes in smelting for several purposes, chief among them catalyzing the desired reactions and chemically binding to unwanted impurities or reaction products. Calcium oxide, in the form of lime, was often used for this purpose, since it could react with the carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide produced during roasting and smelting to keep them out of the working environment.History

Of the seven metals known in antiquity, only gold occurs regularly in native form in the natural environment. The others – copper, lead, silver, tin, iron andmercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

– occur primarily as minerals, though copper is occasionally found in its native state

In biochemistry, the native state of a protein or nucleic acid is its properly folded and/or assembled form, which is operative and functional. The native state of a biomolecule may possess all four levels of biomolecular structure, with the s ...

in commercially significant quantities. These minerals are primarily carbonates, sulfide

Sulfide (British English also sulphide) is an inorganic anion of sulfur with the chemical formula S2− or a compound containing one or more S2− ions. Solutions of sulfide salts are corrosive. ''Sulfide'' also refers to chemical compounds lar ...

s, or oxide

An oxide () is a chemical compound that contains at least one oxygen atom and one other element in its chemical formula. "Oxide" itself is the dianion of oxygen, an O2– (molecular) ion. with oxygen in the oxidation state of −2. Most of the E ...

s of the metal, mixed with other components such as silica and alumina. Roasting

Roasting is a cooking method that uses dry heat where hot air covers the food, cooking it evenly on all sides with temperatures of at least from an open flame, oven, or other heat source. Roasting can enhance the flavor through caramelization ...

the carbonate and sulfide minerals in air converts them to oxides. The oxides, in turn, are smelted into the metal. Carbon monoxide was (and is) the reducing agent of choice for smelting. It is easily produced during the heating process, and as a gas comes into intimate contact with the ore.

In the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by the ...

, humans learned to smelt metals in prehistoric

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

times, more than 8000 years ago. The discovery and use of the "useful" metals – copper and bronze at first, then iron a few millennia later – had an enormous impact on human society. The impact was so pervasive that scholars traditionally divide ancient history into Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with t ...

, Bronze Age, and Iron Age.

In the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

, pre- Inca civilizations of the central Andes in Peru had mastered the smelting of copper and silver at least six centuries before the first Europeans arrived in the 16th century, while never mastering the smelting of metals such as iron for use with weapon-craft.

Tin and lead

In theOld World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by the ...

, the first metals smelted were tin and lead. The earliest known cast lead beads were found in the Çatalhöyük site in Anatolia ( Turkey), and dated from about 6500 BC, but the metal may have been known earlier.

Since the discovery happened several millennia before the invention of writing, there is no written record about how it was made. However, tin and lead can be smelted by placing the ores in a wood fire, leaving the possibility that the discovery may have occurred by accident.

Lead is a common metal, but its discovery had relatively little impact in the ancient world. It is too soft to use for structural elements or weapons, though its high density relative to other metals makes it ideal for sling

sling may refer to:

Places

*Sling, Anglesey, Wales

*Sling, Gloucestershire, England, a small village in the Forest of Dean

People with the name

* Otto Šling (1912–1952), repressed Czech communist functionary

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ...

projectiles. However, since it was easy to cast and shape, workers in the classical world of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome used it extensively to pipe and store water. They also used it as a mortar in stone buildings.

Tin was much less common than lead and is only marginally harder, and had even less impact by itself.

Copper and bronze

After tin and lead, the next metal smelted appears to have been copper. How the discovery came about is debated. Campfires are about 200 °C short of the temperature needed, so some propose that the first smelting of copper may have occurred in pottery kilns. The development of copper smelting in the Andes, which is believed to have occurred independently of the

After tin and lead, the next metal smelted appears to have been copper. How the discovery came about is debated. Campfires are about 200 °C short of the temperature needed, so some propose that the first smelting of copper may have occurred in pottery kilns. The development of copper smelting in the Andes, which is believed to have occurred independently of the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by the ...

, may have occurred in the same way. The earliest current evidence of copper smelting, dating from between 5500 BC and 5000 BC, has been found in Pločnik and Belovode, Serbia. A mace head found in Can Hasan, Turkey and dated to 5000 BC, once thought to be the oldest evidence, now appears to be hammered native copper.

Combining copper with tin and/or arsenic in the right proportions produces bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

, an alloy that is significantly harder than copper. The first copper/arsenic bronzes date from 4200 BC from Asia Minor. The Inca bronze alloys were also of this type. Arsenic is often an impurity in copper ores, so the discovery could have been made by accident. Eventually arsenic-bearing minerals were intentionally added during smelting.

Copper–tin bronzes, harder and more durable, were developed around 3500 BC, also in Asia Minor.

How smiths learned to produce copper/tin bronzes is unknown. The first such bronzes may have been a lucky accident from tin-contaminated copper ores. However, by 2000 BC, people were mining tin on purpose to produce bronze—which is amazing given that tin is a semi-rare metal, and even a rich cassiterite

Cassiterite is a tin oxide mineral, SnO2. It is generally opaque, but it is translucent in thin crystals. Its luster and multiple crystal faces produce a desirable gem. Cassiterite was the chief tin ore throughout ancient history and remains t ...

ore only has 5% tin. Also, it takes special skills (or special instruments) to find it and locate richer lodes. However early peoples learned about tin, they understood how to use it to make bronze by 2000 BC.

The discovery of copper and bronze manufacture had a significant impact on the history of the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by the ...

. Metals were hard enough to make weapons that were heavier, stronger, and more resistant to impact damage than wood, bone, or stone equivalents. For several millennia, bronze was the material of choice for weapons such as sword

A sword is an edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter blade with a pointed ti ...

s, daggers, battle axes, and spear and arrow

An arrow is a fin-stabilized projectile launched by a bow. A typical arrow usually consists of a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty (and usually sharp and pointed) arrowhead attached to the front end, multiple fin-like stabilizers c ...

points, as well as protective gear such as shield

A shield is a piece of personal armour held in the hand, which may or may not be strapped to the wrist or forearm. Shields are used to intercept specific attacks, whether from close-ranged weaponry or projectiles such as arrows, by means of a ...

s, helmets, greaves (metal shin guards), and other body armor

Body armor, also known as body armour, personal armor or armour, or a suit or coat of armor, is protective clothing designed to absorb or deflect physical attacks. Historically used to protect military personnel, today it is also used by variou ...

. Bronze also supplanted stone, wood, and organic materials in tools and household utensils—such as chisel

A chisel is a tool with a characteristically shaped cutting edge (such that wood chisels have lent part of their name to a particular grind) of blade on its end, for carving or cutting a hard material such as wood, stone, or metal by hand, stru ...

s, saws, adzes, nails, blade shears, knives, sewing needles and pins, jugs, cooking pots and cauldrons, mirrors, and horse harnesses. Tin and copper also contributed to the establishment of trade networks that spanned large areas of Europe and Asia, and had a major effect on the distribution of wealth among individuals and nations.

Early iron smelting

The earliest evidence for iron-making is a small number of iron fragments with the appropriate amounts of carbon admixture found in the Proto-Hittite layers at Kaman-Kalehöyük and dated to 2200–2000 BCE. Souckova-Siegolová (2001) shows that iron implements were made in Central Anatolia in very limited quantities around 1800 BCE and were in general use by elites, though not by commoners, during the New Hittite Empire (∼1400–1200 BCE). Archaeologists have found indications of iron working in Ancient Egypt, somewhere between the Third Intermediate Period and23rd Dynasty

The Twenty-third Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XXIII, alternatively 23rd Dynasty or Dynasty 23) is usually classified as the third dynasty of the ancient Egyptian Third Intermediate Period. This dynasty consisted of a number of Meshwesh ki ...

(ca. 1100–750 BCE). Significantly though, they have found no evidence for iron ore smelting in any (pre-modern) period. In addition, very early instances of carbon steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobalt ...

were in production around 2000 years ago (around the first century CE.) in northwest Tanzania, based on complex preheating principles. These discoveries are significant for the history of metallurgy.

Most early processes in Europe and Africa involved smelting iron ore in a bloomery

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a ''bloom ...

, where the temperature is kept low enough so that the iron does not melt. This produces a spongy mass of iron called a bloom, which then must be consolidated with a hammer to produce wrought iron. The earliest evidence to date for the bloomery smelting of iron is found at Tell Hammeh, Jordan, and dates to 930 BCE (

C14 dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

).

Later iron smelting

From the medieval period, an indirect process began to replace direct reduction in bloomeries. This used ablast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

to make pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with silic ...

, which then had to undergo a further process to make forgeable bar iron. Processes for the second stage include fining in a finery forge and, from the Industrial Revolution, puddling

A puddle is a small accumulation of liquid on a surface.

Puddle or Puddles may also refer to:

* Puddle, Cornwall, hamlet in England

* ''Puddle'' (video game)

* Puddle (M. C. Escher), a woodcut by M. C. Escher

* Weld puddle, a crucial part of the ...

. Both processes are now obsolete, and wrought iron is now rarely made. Instead, mild steel is produced from a bessemer converter or by other means including smelting reduction processes such as the Corex Process.

Base metals

The ores of base metals are often sulfides. In recent centuries, reverberatory furnaces have been used to keep the charge being smelted separate from the fuel. Traditionally, they were used for the first step of smelting: forming two liquids, one an oxide slag containing most of the impurities, and the other a sulfide matte containing the valuable metal sulfide and some impurities. Such "reverb" furnaces are today about 40 meters long, 3 meters high and 10 meters wide. Fuel is burned at one end to melt the dry sulfide concentrates (usually after partial roasting) which are fed through openings in the roof of the furnace. The slag floats over the heavier matte and is removed and discarded or recycled. The sulfide matte is then sent to the converter. The precise details of the process vary from one furnace to another depending on the mineralogy of the orebody.

While reverberatory furnaces produced slags containing very little copper, they were relatively energy inefficient and off-gassed a low concentration of

The ores of base metals are often sulfides. In recent centuries, reverberatory furnaces have been used to keep the charge being smelted separate from the fuel. Traditionally, they were used for the first step of smelting: forming two liquids, one an oxide slag containing most of the impurities, and the other a sulfide matte containing the valuable metal sulfide and some impurities. Such "reverb" furnaces are today about 40 meters long, 3 meters high and 10 meters wide. Fuel is burned at one end to melt the dry sulfide concentrates (usually after partial roasting) which are fed through openings in the roof of the furnace. The slag floats over the heavier matte and is removed and discarded or recycled. The sulfide matte is then sent to the converter. The precise details of the process vary from one furnace to another depending on the mineralogy of the orebody.

While reverberatory furnaces produced slags containing very little copper, they were relatively energy inefficient and off-gassed a low concentration of sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a toxic gas responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is released naturally by volcanic activ ...

that was difficult to capture; a new generation of copper smelting technologies has supplanted them. More recent furnaces exploit bath smelting, top-jetting lance smelting, flash smelting and blast furnaces. Some examples of bath smelters include the Noranda furnace, the Isasmelt furnace, the Teniente reactor, the Vunyukov smelter and the SKS technology. Top-jetting lance smelters include the Mitsubishi smelting reactor. Flash smelters account for over 50% of the world's copper smelters. There are many more varieties of smelting processes, including the Kivset, Ausmelt, Tamano, EAF, and BF.

Environmental and occupational health impacts

Smelting has serious effects on the environment, producing wastewater and slag and releasing such toxic metals as copper, silver, iron, cobalt and selenium into the atmosphere. Smelters also release gaseoussulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a toxic gas responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is released naturally by volcanic activ ...

, contributing to acid rain

Acid rain is rain or any other form of precipitation that is unusually acidic, meaning that it has elevated levels of hydrogen ions (low pH). Most water, including drinking water, has a neutral pH that exists between 6.5 and 8.5, but acid ...

, which acidifies soil and water.

The smelter in Flin Flon, Canada was one of the largest point sources of mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

in North America in the 20th century. Even after smelter releases were drastically reduced, landscape re-emission continued to be a major regional source of mercury. Lakes will likely receive mercury contamination from the smelter for decades, from both re-emissions returning as rainwater and leaching of metals from the soil.

Air pollution

Air pollutants generated by aluminum smelters include carbonyl sulfide,hydrogen fluoride

Hydrogen fluoride (fluorane) is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . This colorless gas or liquid is the principal industrial source of fluorine, often as an aqueous solution called hydrofluoric acid. It is an important feedstock i ...

, polycyclic compounds, lead, nickel, manganese, polychlorinated biphenyls and mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

. Copper smelter emissions include arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and hardne ...

, lead, manganese and nickel. Lead smelters typically emit arsenic, antimony, cadmium and various lead compounds.

Wastewater

Wastewater pollutants discharged by iron and steel mills includes gasification products such as benzene,naphthalene

Naphthalene is an organic compound with formula . It is the simplest polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, and is a white crystalline solid with a characteristic odor that is detectable at concentrations as low as 0.08 ppm by mass. As an aromati ...

, anthracene, cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of a ...

, ammonia, phenols and cresols, together with a range of more complex organic compounds known collectively as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH). Treatment technologies include recycling of wastewater; settling basins, clarifiers and filtration systems for solids removal; oil skimmers and filtration; chemical precipitation and filtration for dissolved metals; carbon adsorption and biological oxidation for organic pollutants; and evaporation.

Pollutants generated by other types of smelters varies with the base metal ore. For example, aluminum smelters typically generate fluoride

Fluoride (). According to this source, is a possible pronunciation in British English. is an inorganic, monatomic anion of fluorine, with the chemical formula (also written ), whose salts are typically white or colorless. Fluoride salts typ ...

, benzo(a)pyrene

Benzo 'a''yrene (B''a''P or B ) is a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon and the result of incomplete combustion of organic matter at temperatures between and . The ubiquitous compound can be found in coal tar, tobacco smoke and many foods, espec ...

, antimony and nickel, as well as aluminum. Copper smelters typically discharge cadmium, lead, zinc, arsenic and nickel, in addition to copper.

Health impacts

Labourers working in the smelting industry have reported respiratory illnesses inhibiting their ability to perform the physical tasks demanded by their jobs.Regulations

In the United States, theEnvironmental Protection Agency

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale f ...

has published pollution control regulations for smelters.

* Air pollution standards under the Clean Air Act

* Water pollution standards ( effluent guidelines) under the Clean Water Act

The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the primary federal law in the United States governing water pollution. Its objective is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters; recognizing the responsibiliti ...

.

See also

* Cast iron * Ellingham diagram, useful in predicting the conditions under which an ore reduces to its metal * Copper extraction techniques *Clinker

Clinker may refer to:

*Clinker (boat building), construction method for wooden boats

*Clinker (waste), waste from industrial processes

*Clinker (cement), a kilned then quenched cement product

* ''Clinkers'' (album), a 1978 album by saxophonist St ...

* Cupellation

* Lead smelting

*Metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

* Pyrometallurgy

* Wrought iron

* Zinc smelting

References

Bibliography

*Pleiner, R. (2000) ''Iron in Archaeology. The European Bloomery Smelters'', Praha, Archeologický Ústav Av Cr. *Veldhuijzen, H.A. (2005) Technical Ceramics in Early Iron Smelting. The Role of Ceramics in the Early First Millennium Bc Iron Production at Tell Hammeh (Az-Zarqa), Jordan. In: Prudêncio, I.Dias, I. and Waerenborgh, J.C. (Eds.) ''Understanding People through Their Pottery; Proceedings of the 7th European Meeting on Ancient Ceramics (Emac '03)''. Lisboa, Instituto Português de Arqueologia (IPA). *Veldhuijzen, H.A. and Rehren, Th. (2006) Iron Smelting Slag Formation at Tell Hammeh (Az-Zarqa), Jordan. In: Pérez-Arantegui, J. (Ed.) ''Proceedings of the 34th International Symposium on Archaeometry, Zaragoza, 3–7 May 2004''. Zaragoza, Institución «Fernando el Católico» (C.S.I.C.) Excma. Diputación de Zaragoza.External links

{{Authority control Firing techniques Metallurgical processes de:Verhüttung