Colley Cibber on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Colley Cibber (6 November 1671 – 11 December 1757) was an English

retrieved 11 February 2010

(Subscription required for online version)

Cibber's colourful autobiography ''An Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber, Comedian'' (1740) was chatty, meandering, anecdotal, vain, and occasionally inaccurate. At the time of writing the word "apology" meant an ''

Cibber's colourful autobiography ''An Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber, Comedian'' (1740) was chatty, meandering, anecdotal, vain, and occasionally inaccurate. At the time of writing the word "apology" meant an ''

Cibber began his career as an actor at Drury Lane in 1690, and had little success for several years. "The first Thing that enters into the Head of a young Actor", he wrote in his autobiography half a century later, "is that of being a Hero: In this Ambition I was soon snubb'd by the Insufficiency of my Voice; to which might be added an uninform'd meagre Person ... with a dismal pale Complexion. Under these Disadvantages, I had but a melancholy Prospect of ever playing a Lover with Mrs. Bracegirdle, which I had flatter'd my Hopes that my Youth might one Day have recommended me to."

At this time the London stage was in something of a slump after the glories of the early

Cibber began his career as an actor at Drury Lane in 1690, and had little success for several years. "The first Thing that enters into the Head of a young Actor", he wrote in his autobiography half a century later, "is that of being a Hero: In this Ambition I was soon snubb'd by the Insufficiency of my Voice; to which might be added an uninform'd meagre Person ... with a dismal pale Complexion. Under these Disadvantages, I had but a melancholy Prospect of ever playing a Lover with Mrs. Bracegirdle, which I had flatter'd my Hopes that my Youth might one Day have recommended me to."

At this time the London stage was in something of a slump after the glories of the early  Later in life, when Cibber himself had the last word in casting at Drury Lane, he wrote, or patched together, several

Later in life, when Cibber himself had the last word in casting at Drury Lane, he wrote, or patched together, several  His tragic efforts, however, were consistently ridiculed by contemporaries: when Cibber in the role of

His tragic efforts, however, were consistently ridiculed by contemporaries: when Cibber in the role of

Cibber's comedy ''Love's Last Shift'' (1696) is an early herald of a massive shift in audience taste, away from the

Cibber's comedy ''Love's Last Shift'' (1696) is an early herald of a massive shift in audience taste, away from the

The comedy ''

The comedy ''

"The sentimental mask"

'' PMLA'', vol. 78, no. 5, pp. 529–535 (Subscription required) His

Cibber's career as both actor and theatre manager is important in the history of the British stage because he was one of the first in a long and illustrious line of actor-managers that would include Garrick,

Cibber's career as both actor and theatre manager is important in the history of the British stage because he was one of the first in a long and illustrious line of actor-managers that would include Garrick,

In the first version of his landmark literary satire ''

In the first version of his landmark literary satire ''

The derogatory allusions to Cibber in consecutive versions of Pope's

The derogatory allusions to Cibber in consecutive versions of Pope's  Writing about the degradation of taste brought on by theatrical effects, Pope quotes Cibber's own ''confessio'' in the ''Apology'':

Pope's notes call Cibber a hypocrite, and in general the attacks on Cibber are conducted in the notes added to the ''Dunciad'', and not in the body of the poem. As hero of the ''Dunciad'', Cibber merely watches the events of Book II, dreams Book III, and sleeps through Book IV.

Once Pope struck, Cibber became an easy target for other satirists. He was attacked as the epitome of morally and aesthetically bad writing, largely for the sins of his autobiography. In the ''Apology'', Cibber speaks daringly in the first person and in his own praise. Although the major figures of the day were jealous of their fame, self-promotion of such an overt sort was shocking, and Cibber offended Christian humility as well as gentlemanly modesty. Additionally, Cibber consistently fails to see fault in his own character, praises his vices, and makes no apology for his misdeeds; so it was not merely the fact of the autobiography, but the manner of it that shocked contemporaries. His diffuse and chatty writing style, conventional in poetry and sometimes incoherent in prose, was bound to look even worse in contrast to stylists like Pope. Henry Fielding satirically tried Cibber for murder of the English language in the 17 May 1740 issue of ''The Champion''. The Tory wits were altogether so successful in their satire of Cibber that the historical image of the man himself was almost obliterated, and it was as the King of Dunces that he came down to posterity.

Writing about the degradation of taste brought on by theatrical effects, Pope quotes Cibber's own ''confessio'' in the ''Apology'':

Pope's notes call Cibber a hypocrite, and in general the attacks on Cibber are conducted in the notes added to the ''Dunciad'', and not in the body of the poem. As hero of the ''Dunciad'', Cibber merely watches the events of Book II, dreams Book III, and sleeps through Book IV.

Once Pope struck, Cibber became an easy target for other satirists. He was attacked as the epitome of morally and aesthetically bad writing, largely for the sins of his autobiography. In the ''Apology'', Cibber speaks daringly in the first person and in his own praise. Although the major figures of the day were jealous of their fame, self-promotion of such an overt sort was shocking, and Cibber offended Christian humility as well as gentlemanly modesty. Additionally, Cibber consistently fails to see fault in his own character, praises his vices, and makes no apology for his misdeeds; so it was not merely the fact of the autobiography, but the manner of it that shocked contemporaries. His diffuse and chatty writing style, conventional in poetry and sometimes incoherent in prose, was bound to look even worse in contrast to stylists like Pope. Henry Fielding satirically tried Cibber for murder of the English language in the 17 May 1740 issue of ''The Champion''. The Tory wits were altogether so successful in their satire of Cibber that the historical image of the man himself was almost obliterated, and it was as the King of Dunces that he came down to posterity.

actor-manager

An actor-manager is a leading actor who sets up their own permanent theatrical company and manages the business, sometimes taking over a theatre to perform select plays in which they usually star. It is a method of theatrical production used ...

, playwright and Poet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch ...

. His colourful memoir ''Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber'' (1740) describes his life in a personal, anecdotal and even rambling style. He wrote 25 plays for his own company at Drury Lane, half of which were adapted from various sources, which led Robert Lowe and Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

, among others, to criticise his "miserable mutilation" of "crucified Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (, ; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, , ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the French language and world ...

ndhapless Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

". He regarded himself as first and foremost an actor and had great popular success in comical fop

Fop is a pejorative term for a foolish man.

FOP or fop may also refer to:

Science and technology

* Feature-oriented positioning, in scanning microscopy

* Feature-oriented programming, in computer science, software product lines

* Fibrodysplasia ...

parts, while as a tragic actor he was persistent but much ridiculed. Cibber's brash, extroverted personality did not sit well with his contemporaries, and he was frequently accused of tasteless theatrical productions, shady business methods, and a social and political opportunism that was thought to have gained him the laureateship over far better poets. He rose to ignominious fame when he became the chief target, the head Dunce, of Alexander Pope's satirical poem ''The Dunciad

''The Dunciad'' is a landmark, mock-heroic, narrative poem by Alexander Pope published in three different versions at different times from 1728 to 1743. The poem celebrates a goddess Dulness and the progress of her chosen agents as they bring ...

''.

Cibber's poetical work was derided in his time, and has been remembered only for being poor. His importance in British theatre history rests on his being one of the first in a long line of actor-managers, on the interest of two of his comedies as documents of evolving early 18th-century taste and ideology, and on the value of his autobiography as a historical source.

Life

Cibber was born inSouthampton Street

Southampton Street is a street in central London, running north from the Strand to Covent Garden Market.

There are restaurants in the street such as Bistro 1

and Wagamama. There are also shops

such as The North Face outdoor clothing shop ...

, in Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest mus ...

, London. He was the eldest child of Caius Gabriel Cibber

Caius Gabriel Cibber (1630–1700) was a Danish sculptor, who enjoyed great success in England, and was the father of the actor, author and poet laureate Colley Cibber. He was appointed "carver to the king's closet" by William III.

Biograph ...

, a distinguished sculptor originally from Denmark. His mother, Jane née Colley, came from a family of gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

from Glaston

Glaston is a village in the county of Rutland in the East Midlands of England. The population of the civil parish remained unchanged between the 2001 and the 2011 censuses.

The village's name means 'farm/settlement of Glathr'.

Glaston is abou ...

, Rutland

Rutland () is a ceremonial county and unitary authority in the East Midlands, England. The county is bounded to the west and north by Leicestershire, to the northeast by Lincolnshire and the southeast by Northamptonshire.

Its greatest l ...

. He was educated at the King's School, Grantham

The King's School is a British grammar school with academy status, in the market town of Grantham, Lincolnshire, England. The school's history can be traced to 1329, and was re-endowed by Richard Foxe in 1528. Located on Brook Street, the sch ...

, from 1682 until the age of 16, but failed to win a place at Winchester College

Winchester College is a public school (fee-charging independent day and boarding school) in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It was founded by William of Wykeham in 1382 and has existed in its present location ever since. It is the oldest of ...

, which had been founded by his maternal ancestor William of Wykeham

William of Wykeham (; 1320 or 1324 – 27 September 1404) was Bishop of Winchester and Chancellor of England. He founded New College, Oxford, and New College School in 1379, and founded Winchester College in 1382. He was also the clerk of w ...

. In 1688, he joined the service of his father's patron, Lord Devonshire, who was one of the prime supporters of the Glorious Revolution. After the revolution, and at a loose end in London, he was attracted to the stage and in 1690 began work as an actor in Thomas Betterton

Thomas Patrick Betterton (August 1635 – 28 April 1710), the leading male actor and theatre manager during Restoration England, son of an under-cook to King Charles I, was born in London.

Apprentice and actor

Betterton was born in August 16 ...

's United Company

The United Company was a London theatre company formed in 1682 with the merger of the King's Company and the Duke's Company.

Both the Duke's and King's Companies suffered poor attendance during the turmoil of the Popish Plot period, 1678–8 ...

at the Drury Lane Theatre

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dru ...

. "Poor, at odds with his parents, and entering the theatrical world at a time when players were losing their power to businessmen-managers", on 6 May 1693 Cibber married Katherine Shore, the daughter of Matthias Shore, sergeant-trumpeter to the King, despite his poor prospects and insecure, socially inferior job.

Cibber and Katherine had 12 children between 1694 and 1713. Six died in infancy, and most of the surviving children received short shrift in his will. Catherine, the eldest surviving daughter, married Colonel James Brown and seems to have been the dutiful one who looked after Cibber in old age following his wife's death in 1734. She was duly rewarded at his death with most of his estate. His middle daughters, Anne and Elizabeth, went into business. Anne had a shop that sold fine wares and foods, and married John Boultby. Elizabeth had a restaurant near Gray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and Wa ...

, and married firstly Dawson Brett, and secondly (after Brett's death) Joseph Marples. His only son to reach adulthood, Theophilus

Theophilus is a male given name with a range of alternative spellings. Its origin is the Greek word Θεόφιλος from θεός (God) and φιλία (love or affection) can be translated as "Love of God" or "Friend of God", i.e., it is a theoph ...

, became an actor at Drury Lane, and was an embarrassment to his father because of his scandalous private life. His other son to survive infancy, James, died in or after 1717, before reaching adulthood. Colley's youngest daughter Charlotte

Charlotte ( ) is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont (United States), Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, Meckl ...

followed in her father's theatrical footsteps, but she fell out with him and her sister Catherine, and she was cut off by the family.

After an inauspicious start as an actor, Cibber eventually became a popular comedian, wrote and adapted many plays, and rose to become one of the newly empowered businessmen-managers. He took over the management of Drury Lane in 1710 and took a highly commercial, if not artistically successful, line in the job. In 1730, he was made Poet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch ...

, an appointment which attracted widespread scorn, particularly from Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

and other Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

satirists. Off-stage, he was a keen gambler, and was one of the investors in the South Sea Company

The South Sea Company (officially The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British joint-stock company founded in Ja ...

.

In the last two decades of his life, Cibber remained prominent in society, and summered in Georgian spa

A spa is a location where mineral-rich spring water (and sometimes seawater) is used to give medicinal baths. Spa towns or spa resorts (including hot springs resorts) typically offer various health treatments, which are also known as balneothe ...

s such as Tunbridge, Scarborough and Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

. He was friendly with the writer Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: '' Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and ''The History ...

, the actress Margaret Woffington

Margaret Woffington (18 October 1720 – 28 March 1760), known professionally as Peg Woffington, was an Irish actress and socialite of the Georgian era. Peg and Peggy were a common pet name for those called Margaret until the late 20th centur ...

and the memoirist–poet Laetitia Pilkington

Laetitia Pilkington (born Laetitia van Lewen; ''c.'' 1709 – 29 July 1750) was an Anglo-Irish poet. She is known for her ''Memoirs'' which document much of what is known about Jonathan Swift.

Life

Early years

Laetitia was born of two dist ...

. Aged 73 in 1745, he made his last appearance on the stage as Pandulph in his own "deservedly unsuccessful" ''Papal Tyranny in the Reign of King John''. In 1750, he fell seriously ill and recommended his friend and protégé Henry Jones as the next Poet Laureate. Cibber recovered and Jones passed into obscurity. Cibber died suddenly at his house in Berkeley Square

Berkeley Square is a garden square in the West End of London. It is one of the best known of the many squares in London, located in Mayfair in the City of Westminster. It was laid out in the mid 18th century by the architect William Ke ...

, London, in December 1757, leaving small pecuniary legacies to four of his five surviving children, £1,000 each (the equivalent of approximately £180,000 in 2011) to his granddaughters Jane and Elizabeth (the daughters of Theophilus), and the residue of his estate to his eldest daughter Catherine. He was buried on 18 December, probably at the Grosvenor Chapel

Grosvenor Chapel is an Anglican church in what is now the City of Westminster, in England, built in the 1730s. It inspired many churches in New England. It is situated on South Audley Street in Mayfair.

History

The foundation stone of the Grosve ...

on South Audley Street.Salmon, Eric (September 2004; online edition January 2008) "Cibber, Colley (1671–1757)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Oxford University Pressretrieved 11 February 2010

(Subscription required for online version)

Autobiography

Cibber's colourful autobiography ''An Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber, Comedian'' (1740) was chatty, meandering, anecdotal, vain, and occasionally inaccurate. At the time of writing the word "apology" meant an ''

Cibber's colourful autobiography ''An Apology for the Life of Colley Cibber, Comedian'' (1740) was chatty, meandering, anecdotal, vain, and occasionally inaccurate. At the time of writing the word "apology" meant an ''apologia

An apologia (Latin for apology, from Greek ἀπολογία, "speaking in defense") is a formal defense of an opinion, position or action. The term's current use, often in the context of religion, theology and philosophy, derives from Justin Mar ...

'', a statement in defence of one's actions rather than a statement of regret for having transgressed.

The text virtually ignores his wife and family, but Cibber wrote in detail about his time in the theatre, especially his early years as a young actor at Drury Lane in the 1690s, giving a vivid account of the cut-throat theatre company rivalries and chicanery of the time, as well as providing pen portraits of the actors he knew. The ''Apology'' is vain and self-serving, as both his contemporaries and later commentators have pointed out, but it also serves as Cibber's rebuttal to his harshest critics, especially Pope. For the early part of Cibber's career, it is unreliable in respect of chronology and other hard facts, understandably, since it was written 50 years after the events, apparently without the help of a journal or notes. Nevertheless, it is an invaluable source for all aspects of the early 18th-century theatre in London, for which documentation is otherwise scanty. Because he worked with many actors from the early days of Restoration theatre, such as Thomas Betterton and Elizabeth Barry

Elizabeth Barry (1658 – 7 November 1713) was an English actress of the Restoration period.

Elizabeth Barry's biggest influence on Restoration drama was her presentation of performing as the tragic actress. She worked in large, prestigious ...

at the end of their careers, and lived to see David Garrick perform, he is a bridge between the earlier mannered and later more naturalistic styles of performance.

The ''Apology'' was a popular work and gave Cibber a good return. Its complacency infuriated some of his contemporaries, notably Pope, but even the usually critical Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford D ...

admitted it was "very entertaining and very well done". It went through four editions in his lifetime, and more after his death, and generations of readers have found it an amusing and engaging read, projecting an author always "happy in his own good opinion, the best of all others; teeming with animal spirits, and uniting the self-sufficiency of youth with the garrulity of age."

Actor

Cibber began his career as an actor at Drury Lane in 1690, and had little success for several years. "The first Thing that enters into the Head of a young Actor", he wrote in his autobiography half a century later, "is that of being a Hero: In this Ambition I was soon snubb'd by the Insufficiency of my Voice; to which might be added an uninform'd meagre Person ... with a dismal pale Complexion. Under these Disadvantages, I had but a melancholy Prospect of ever playing a Lover with Mrs. Bracegirdle, which I had flatter'd my Hopes that my Youth might one Day have recommended me to."

At this time the London stage was in something of a slump after the glories of the early

Cibber began his career as an actor at Drury Lane in 1690, and had little success for several years. "The first Thing that enters into the Head of a young Actor", he wrote in his autobiography half a century later, "is that of being a Hero: In this Ambition I was soon snubb'd by the Insufficiency of my Voice; to which might be added an uninform'd meagre Person ... with a dismal pale Complexion. Under these Disadvantages, I had but a melancholy Prospect of ever playing a Lover with Mrs. Bracegirdle, which I had flatter'd my Hopes that my Youth might one Day have recommended me to."

At this time the London stage was in something of a slump after the glories of the early Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

*Restoration ecology ...

period. The King's and Duke's companies had merged into a monopoly, leaving actors in a weak negotiating position and much at the mercy of the dictatorial manager Christopher Rich. When the senior actors rebelled and established a cooperative company of their own in 1695, Cibber—"wisely", as the ''Biographical Dictionary of Actors'' puts it—stayed with the remnants of the old company, "where the competition was less keen". After five years, he had still not seen significant success in his chosen profession, and there had been no heroic parts and no love scenes. However, the return of two-company rivalry created a sudden demand for new plays, and Cibber seized this opportunity to launch his career by writing a comedy with a big, flamboyant part for himself to play. He scored a double triumph: his comedy '' Love's Last Shift, or The Fool in Fashion'' (1696) was a great success, and his own uninhibited performance as the Frenchified fop

Fop is a pejorative term for a foolish man.

FOP or fop may also refer to:

Science and technology

* Feature-oriented positioning, in scanning microscopy

* Feature-oriented programming, in computer science, software product lines

* Fibrodysplasia ...

Sir Novelty Fashion ("a coxcomb that loves to be the first in all foppery") delighted the audiences. His name was made, both as playwright and as comedian.

Later in life, when Cibber himself had the last word in casting at Drury Lane, he wrote, or patched together, several

Later in life, when Cibber himself had the last word in casting at Drury Lane, he wrote, or patched together, several tragedies

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy ...

that were tailored to fit his continuing hankering after playing "a Hero". However, his performances of such parts never pleased audiences, which wanted to see him typecast as an affected fop, a kind of character that fitted both his private reputation as a vain man, his exaggerated, mannered style of acting, and his habit of ad libbing. His most famous part for the rest of his career remained that of Lord Foppington in ''The Relapse

''The Relapse, or, Virtue in Danger'' is a Restoration comedy from 1696 written by John Vanbrugh. The play is a sequel to Colley Cibber's '' Love's Last Shift, or, The Fool in Fashion''.

In Cibber's ''Love's Last Shift'', a free-living Rest ...

'', a sequel to Cibber's own ''Love's Last Shift'' but written by John Vanbrugh

Sir John Vanbrugh (; 24 January 1664 (baptised) – 26 March 1726) was an English architect, dramatist and herald, perhaps best known as the designer of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard. He wrote two argumentative and outspoken Restor ...

, first performed in 1696 with Cibber reprising his performance as Sir Novelty Fashion in the newly ennobled guise of Lord Foppington. Pope mentions the audience jubilation that greeted the small-framed Cibber donning Lord Foppington's enormous wig, which would be ceremoniously carried on stage in its own sedan chair

The litter is a class of wheelless vehicles, a type of human-powered transport, for the transport of people. Smaller litters may take the form of open chairs or beds carried by two or more carriers, some being enclosed for protection from the e ...

. Vanbrugh reputedly wrote the part of Lord Foppington deliberately "to suit the eccentricities of Cibber's acting style".

His tragic efforts, however, were consistently ridiculed by contemporaries: when Cibber in the role of

His tragic efforts, however, were consistently ridiculed by contemporaries: when Cibber in the role of Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Bat ...

made love to Lady Anne, the ''Grub Street Journal

''The Grub-Street Journal'', published from 8 January 1730 to 1738, was a satire on popular journalism and hack-writing as it was conducted in Grub Street in London. It was largely edited by the nonjuror Richard Russel and the botanist John Ma ...

'' wrote, "he looks like a pickpocket, with his shrugs and grimaces, that has more a design on her purse than her heart". Cibber was on the stage in every year but two (1727 and 1731) between his debut in 1690 and his retirement in 1732, playing more than 100 parts in all in nearly 3,000 documented performances. After he had sold his interest in Drury Lane in 1733 and was a wealthy man in his sixties, he returned to the stage occasionally to play the classic fop parts of Restoration comedy for which audiences appreciated him. His Lord Foppington in Vanbrugh's ''The Relapse'', Sir Courtly Nice in John Crowne

John Crowne (6 April 1641 – 1712) was a British dramatist.

His father "Colonel" William Crowne, accompanied the earl of Arundel on a diplomatic mission to Vienna in 1637, and wrote an account of his journey. He emigrated to Nova Scotia where ...

's ''Sir Courtly Nice

''Sir Courtly Nice: Or, It Cannot Be'' is a 1685 comedy play by the English writer John Crowne. Rehearsals by the United Company were underway when the death of Charles II in February led to the closure of all theatres as a mark of respect. Th ...

'', and Sir Fopling Flutter in George Etherege

Sir George Etherege (c. 1636, Maidenhead, Berkshire – c. 10 May 1692, Paris) was an English dramatist. He wrote the plays '' The Comical Revenge or, Love in a Tub'' in 1664, '' She Would If She Could'' in 1668, and '' The Man of Mode or, ...

's ''Man of Mode'' were legendary. Critic John Hill in his 1775 work ''The actor, or, A treatise on the art of playing'', described Cibber as "the best Lord Foppington who ever appeared, was in real life (with all due respect be it spoken by one who loves him) something of the coxcomb". These were the kind of comic parts where Cibber's affectation and mannerism were desirable. In 1738–39, he played Shallow in Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 2 to critical acclaim, but his Richard III (in his own version of the play) was not well received. In the middle of the play, he whispered to fellow actor Benjamin Victor that he wanted to go home, perhaps realising he was too old for the part and its physical demands. Cibber also essayed tragic parts in plays by Shakespeare, Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for ...

, John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the p ...

and others, but with less success. By the end of his acting career, audiences were being entranced by the innovatively naturalistic acting of the rising star David Garrick, who made his London debut in the title part in a production of Cibber's adaptation of ''Richard III'' in 1741. He returned to the stage for a final time in 1745 as Cardinal Pandulph in his play ''Papal Tyranny in the Reign of King John''.

Playwright

''Love's Last Shift''

Cibber's comedy ''Love's Last Shift'' (1696) is an early herald of a massive shift in audience taste, away from the

Cibber's comedy ''Love's Last Shift'' (1696) is an early herald of a massive shift in audience taste, away from the intellectualism

Intellectualism is the mental perspective that emphasizes the use, the development, and the exercise of the intellect; and also identifies the life of the mind of the intellectual person. (Definition) In the field of philosophy, the term ''inte ...

and sexual frankness of Restoration comedy and towards the conservative certainties and gender-role backlash of exemplary or sentimental comedy Sentimental comedy is an 18th-century dramatic genre which sprang up as a reaction to the immoral tone of English Restoration plays. In sentimental comedies, middle-class protagonists triumphantly overcome a series of moral trials. These plays aimed ...

. According to Paul Parnell, ''Love's Last Shift'' illustrates Cibber's opportunism at a moment in time before the change was assured: fearless of self-contradiction, he puts something for everybody into his first play, combining the old outspokenness with the new preachiness.

The central action of ''Love's Last Shift'' is a celebration of the power of a good woman, Amanda, to reform a rakish husband, Loveless, by means of sweet patience and a daring bed-trick. She masquerades as a prostitute and seduces Loveless without being recognised, and then confronts him with logical argument. Since he enjoyed the night with her while taking her for a stranger, a wife can be as good in bed as an illicit mistress. Loveless is convinced and stricken, and a rich choreography of mutual kneelings, risings and prostrations follows, generated by Loveless' penitence and Amanda's "submissive eloquence". The première audience is said to have wept at this climactic scene. The play was a great box-office success and was for a time the talk of the town, in both a positive and a negative sense. Some contemporaries regarded it as moving and amusing, others as a sentimental tear-jerker, incongruously interspersed with sexually explicit Restoration comedy jokes and semi-nude bedroom scenes.

''Love's Last Shift'' is today read mainly to gain a perspective on Vanbrugh

Sir John Vanbrugh (; 24 January 1664 (baptised) – 26 March 1726) was an English architect, dramatist and herald, perhaps best known as the designer of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard. He wrote two argumentative and outspoken Restorat ...

's sequel ''The Relapse'', which has by contrast remained a stage favourite. Modern scholars often endorse the criticism that was levelled at ''Love's Last Shift'' from the first, namely that it is a blatantly commercial combination of sex scenes and drawn-out sentimental reconciliations. Cibber's follow-up comedy ''Woman's Wit'' (1697) was produced under hasty and unpropitious circumstances and had no discernible theme; Cibber, not usually shy about any of his plays, even elided its name in the ''Apology''. It was followed by the equally unsuccessful tragedy ''Xerxes'' (1699). Cibber reused parts of ''Woman's Wit'' for ''The School Boy'' (1702).

''Richard III''

Perhaps partly because of the failure of his previous two plays, Cibber's next effort was an adaptation ofShakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's ''Richard III''. Neither Cibber's adaptations nor his own original plays have stood the test of time, and hardly any of them have been staged or reprinted after the early 18th century, but his popular adaptation of ''Richard III'' remained the standard stage version for 150 years. The American actor George Berrell

George Berrell (December 16, 1849 – April 20, 1933) was an American actor of both the 19th and early 20th century stage and of the silent film era. He appeared in numerous stage plays as well as more than 50 films over the course of a car ...

wrote in the 1870s that ''Richard III'' was:

''Richard III'' was followed by another adaptation, the comedy ''Love Makes a Man

''Love Makes A Man; Or, The Fop's Fortune is a 1700 comedy play by the English writer Colley Cibber. It borrows elements from two Jacobean plays ''The Elder Brother'' and '' The Custom of the Country'' by John Fletcher.

It was originally stage ...

'', which was constructed by splicing together two plays by John Fletcher: '' The Elder Brother'' and '' The Custom of the Country''. Cibber's confidence was apparently restored by the success of the two plays, and he returned to more original writing.

''The Careless Husband''

The comedy ''

The comedy ''The Careless Husband

''The Carless Husband'' is a comedy play by the English writer Colley Cibber. It premiered at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on 7 December 1704. The original cast featured Cibber as Lord Foppington, George Powell as Lord Morelove, Robert Wilks as ...

'' (1704), generally considered to be Cibber's best play, is another example of the retrieval of a straying husband by means of outstanding wifely tact, this time in a more domestic and genteel register. The easy-going Sir Charles Easy is chronically unfaithful to his wife, seducing both ladies of quality and his own female servants with insouciant charm. The turning point of the action, known as "the Steinkirk scene", comes when his wife finds him and a maidservant asleep together in a chair, "as close an approximation to actual adultery as could be presented on the 18th-century stage".Parnell, Paul E. (1963"The sentimental mask"

'' PMLA'', vol. 78, no. 5, pp. 529–535 (Subscription required) His

periwig

A wig is a head or hair accessory made from human hair, animal hair, or synthetic fiber. The word wig is short for periwig, which makes its earliest known appearance in the English language in William Shakespeare's ''The Two Gentlemen of Verona' ...

has fallen off, an obvious suggestion of intimacy and abandon, and an opening for Lady Easy's tact. Soliloquizing to herself about how sad it would be if he caught cold, she "takes a Steinkirk off her Neck, and lays it gently on his Head" (V.i.21). (A "steinkirk" was a loosely tied lace collar or scarf, named after the way the officers wore their cravat Cravat, cravate or cravats may refer to:

* Cravat (early), forerunner neckband of the modern necktie

* Cravat, British name for what in American English is called an ascot tie

* Cravat bandage, a triangular bandage

* Cravat (horse) (1935–1954), a ...

s at the Battle of Steenkirk

The Battle of Steenkerque, also known as ''Steenkerke'', ''Steenkirk'' or ''Steinkirk'' was fought on 3 August 1692, during the Nine Years' War, near Steenkerque, then part of the Spanish Netherlands but now in modern Belgium A French force ...

in 1692.) She steals away, Sir Charles wakes, notices the steinkirk on his head, marvels that his wife did not wake him and make a scene, and realises how wonderful she is. The Easys go on to have a reconciliation scene which is much more low-keyed and tasteful than that in ''Love's Last Shift'', without kneelings and risings, and with Lady Easy shrinking with feminine delicacy from the coarse subjects that Amanda had broached without blinking. Paul Parnell has analysed the manipulative nature of Lady Easy's lines in this exchange, showing how they are directed towards the sentimentalist's goal of "ecstatic self-approval".

''The Careless Husband'' was a great success on the stage and remained a repertory

A repertory theatre is a theatre in which a resident company presents works from a specified repertoire, usually in alternation or rotation.

United Kingdom

Annie Horniman founded the first modern repertory theatre in Manchester after withdrawi ...

play throughout the 18th century. Although it has now joined ''Love's Last Shift'' as a forgotten curiosity, it kept a respectable critical reputation into the 20th century, coming in for serious discussion both as an interesting example of doublethink

Doublethink is a process of indoctrination in which subjects are expected to simultaneously accept two conflicting beliefs as truth, often at odds with their own memory or sense of reality. Doublethink is related to, but differs from, hypocrisy. ...

, and as somewhat morally or emotionally insightful. In 1929, the well-known critic F. W. Bateson

Frederick (Noel) Wilse Bateson (1901 – 1978) was an English literary scholar and critic.

Life

Bateson was born in Cheshire, and educated at Charterhouse and at Trinity College, Oxford, where he took a BA in English (second class), and then the B ...

described the play's psychology as "mature", "plausible", "subtle", "natural", and "affecting".

Other plays

''The Lady's Last Stake'' (1707) is a rather bad-tempered reply to critics of Lady Easy's wifely patience in ''The Careless Husband''. It was coldly received, and its main interest lies in the glimpse the prologue gives of angry reactions to ''The Careless Husband'', of which we would otherwise have known nothing (since all contemporary published reviews of ''The Careless Husband'' approve and endorse its message). Some, says Cibber sarcastically in the prologue, seem to think Lady Easy ought rather to have strangled her husband with her steinkirk: Many of Cibber's plays, listed below, were hastily cobbled together from borrowings. Alexander Pope said Cibber's drastic adaptations and patchwork plays were stolen from "crucified Molière" and "hapless Shakespeare". ''The Double Gallant

''The Double Gallant'' is a 1707 comedy play by the British writer Colley Cibber.

It was originally performed on 1 November 1707 at the Queen's Theatre in the Haymarket with a cast that included Benjamin Johnson as Sir Solomon, Barton Booth a ...

'' (1707) was constructed from Burnaby's ''The Reformed Wife'' and ''The Lady's Visiting Day'', and Centlivre's ''Love at a Venture''. In the words of Leonard R. N. Ashley, Cibber took "what he could use from these old failures" to cook up "a palatable hash out of unpromising leftovers". ''The Comical Lovers'' (1707) was based on Dryden's '' Marriage à la Mode''. '' The Rival Fools'' (1709) was based on Fletcher's ''Wit at Several Weapons

''Wit at Several Weapons'' is a seventeenth-century comedy of uncertain date and authorship.

Authorship and Date

In its own century, the play appeared in print only in the two Beaumont and Fletcher folios of 1647 and 1679; yet modern scholarship ...

''. He rewrote Corneille's ''Le Cid

''Le Cid'' is a five-act French tragicomedy written by Pierre Corneille, first performed in December 1636 at the Théâtre du Marais in Paris and published the same year. It is based on Guillén de Castro's play ''Las Mocedades del Cid''. Cast ...

'' with a happy ending as ''Ximena'' in 1712. ''The Provoked Husband

''The Provoked Husband'' is a 1728 comedy play by the British writer and actor Colley Cibber, based on a fragment of play written by John Vanbrugh. It is also known by the longer title ''The Provok'd Husband: or, a Journey to London''.

Vanbrug ...

'' (1728) was an unfinished fragment by John Vanbrugh that Cibber reworked and completed to great commercial success.

'' The Non-Juror'' (1717) was adapted from Molière

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (, ; 15 January 1622 (baptised) – 17 February 1673), known by his stage name Molière (, , ), was a French playwright, actor, and poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers in the French language and world ...

's ''Tartuffe

''Tartuffe, or The Impostor, or The Hypocrite'' (; french: Tartuffe, ou l'Imposteur, ), first performed in 1664, is a theatrical comedy by Molière. The characters of Tartuffe, Elmire, and Orgon are considered among the greatest classical thea ...

'', and features a Papist spy as a villain. Written just two years after the Jacobite rising of 1715

The Jacobite rising of 1715 ( gd, Bliadhna Sheumais ;

or 'the Fifteen') was the attempt by James Edward Stuart (the Old Pretender) to regain the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland for the exiled Stuarts.

At Braemar, Aberdeenshire ...

, it was an obvious propaganda piece directed against Roman Catholics. ''The Refusal

"The Refusal" (German: "Die Abweisung"), also known as "Unser Städtchen liegt …", is a short story by Franz Kafka. Written in the autumn of 1920, it was not published in Kafka's lifetime.

Overview

The story of "Die Abweisung" involves the narr ...

'' (1721) was based on Molière's ''Les Femmes Savantes

''Les Femmes savantes'' (''The Learned Ladies'') is a comedy by Molière in five acts, written in verse. A satire on academic pretension, female education, and préciosité (French for preciousness), it was one of his most popular comedies and ...

''. Cibber's last play, ''Papal Tyranny in the Reign of King John'' was "a miserable mutilation of Shakespeare's '' King John''". Heavily politicised, it caused such a storm of ridicule during its 1736 rehearsal that Cibber withdrew it. During the Jacobite Rising of 1745

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45 ( gd, Bliadhna Theàrlaich, , ), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took ...

, when the nation was again in fear of a Popish

The words Popery (adjective Popish) and Papism (adjective Papist, also used to refer to an individual) are mainly historical pejorative words in the English language for Roman Catholicism, once frequently used by Protestants and Eastern Orthodo ...

pretender, it was finally acted, and this time accepted for patriotic reasons.

Manager

Cibber's career as both actor and theatre manager is important in the history of the British stage because he was one of the first in a long and illustrious line of actor-managers that would include Garrick,

Cibber's career as both actor and theatre manager is important in the history of the British stage because he was one of the first in a long and illustrious line of actor-managers that would include Garrick, Henry Irving

Sir Henry Irving (6 February 1838 – 13 October 1905), christened John Henry Brodribb, sometimes known as J. H. Irving, was an English stage actor in the Victorian era, known as an actor-manager because he took complete responsibility ...

, and Herbert Beerbohm Tree

Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree (17 December 1852 – 2 July 1917) was an English actor and theatre manager.

Tree began performing in the 1870s. By 1887, he was managing the Haymarket Theatre in the West End, winning praise for adventurous programm ...

. Rising from actor at Drury Lane to advisor to the manager Christopher Rich, Cibber worked himself by degrees into a position to take over the company, first taking many of its players—including Thomas Doggett

Thomas Doggett (or Dogget) (20 September 1721) was an Irish actor. The birth date of 1640 seems unlikely. A more probable date of 1670 is given in the Encyclopædia Britannica.

Biography

Doggett was born in Dublin, and made his first stage app ...

, Robert Wilks

Robert Wilks (''c.'' 1665 – 27 September 1732) was a British actor and theatrical manager who was one of the leading managers of Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in its heyday of the 1710s. He was, with Colley Cibber and Thomas Doggett, one of the ...

, and Anne Oldfield

Anne Oldfield (168323 October 1730) was an English actress and one of the highest paid actresses of her time.

Early life and discovery

She was born in London in 1683. Her father was a soldier, James Oldfield. Her mother was either Anne or Eli ...

—to form a new company at the Queen's Theatre at the Haymarket. The three actors squeezed out the previous owners in a series of lengthy and complex manoeuvres, but after Rich's letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, t ...

were revoked, Cibber, Doggett and Wilks were able to buy the company outright and return to the Theatre Royal by 1711. After a few stormy years of power-struggle between the prudent Doggett and the extravagant Wilks, Doggett was replaced by the upcoming actor Barton Booth

Barton Booth (168210 May 1733) was one of the most famous dramatic actors of the first part of the 18th century.

Early life

Booth was the son of The Hon and Very Revd Dr Robert Booth, Dean of Bristol, by his first wife and distant cousin Ann ...

and Cibber became in practice sole manager of Drury Lane. He set a pattern for the line of more charismatic and successful actors that were to succeed him in this combination of roles. His near-contemporary Garrick, as well as the 19th-century actor-managers Irving and Tree, would later structure their careers, writing, and manager identity around their own striking stage personalities. Cibber's ''forte'' as actor-manager was, by contrast, the manager side. He was a clever, innovative, and unscrupulous businessman who retained all his life a love of appearing on the stage. His triumph was that he rose to a position where, in consequence of his sole power over production and casting at Drury Lane, London audiences had to put up with him as an actor. Cibber's one significant mistake as a theatre manager was to pass over John Gay

John Gay (30 June 1685 – 4 December 1732) was an English poet and dramatist and member of the Scriblerus Club. He is best remembered for '' The Beggar's Opera'' (1728), a ballad opera. The characters, including Captain Macheath and Polly ...

's ''The Beggar's Opera

''The Beggar's Opera'' is a ballad opera in three acts written in 1728 by John Gay with music arranged by Johann Christoph Pepusch. It is one of the watershed plays in Augustan drama and is the only example of the once thriving genre of sa ...

'', which became an outstanding success for John Rich

John Rich (born January 7, 1974) is an American country music singer-songwriter. From 1992 to 1998, he was a member of the country music band Lonestar, in which he played bass guitar and alternated with Richie McDonald as lead vocalist. After d ...

's theatre at Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is the List of city squares by size, largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a long series of entreprene ...

. When Cibber attempted to mimic Gay's success with his own ballad-opera—'' Love in a Riddle'' (1729)—it was shouted down by the audience and Cibber cancelled its run. He rescued its comic subplot as ''Damon and Phillida''.

Cibber had learned from the bad example of Christopher Rich to be a careful and approachable employer for his actors, and was not unpopular with them; however, he made enemies in the literary world because of the power he wielded over authors. Plays he considered non-commercial were rejected or ruthlessly reworked. Many were outraged by his sharp business methods, which may be exemplified by the characteristic way he abdicated as manager in the mid-1730s. In 1732, Booth sold his share to John Highmore, and Wilks' share fell into the hands of John Ellys after Wilks' death. Cibber leased his share in the company to his scapegrace son Theophilus for 442 pounds, but when Theophilus fell out with the other managers, they approached Cibber senior and offered to buy out his share. Without consulting Theophilus, Cibber sold his share for more than 3,000 pounds to the other managers, who promptly gave Theophilus his notice. According to one story, Cibber encouraged his son to lead the actors in a walkout and set up for themselves in the Haymarket, rendering worthless the commodity he had sold. On behalf of his son, Cibber applied for a letters patent to perform at the Haymarket, but it was refused by the Lord Chamberlain

The Lord Chamberlain of the Household is the most senior officer of the Royal Household of the United Kingdom, supervising the departments which support and provide advice to the Sovereign of the United Kingdom while also acting as the main c ...

, who was "disgusted at Cibber's conduct". The Drury Lane managers attempted to shut down the rival Haymarket players by conspiring in the arrest of the lead actor, John Harper, on a charge of vagrancy, but the charge did not hold, and the attempt pushed public opinion to Theophilus' side. The Drury Lane managers were defeated, and Theophilus regained control of the company on his own terms.

Poet

Cibber's appointment asPoet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch ...

in December 1730 was widely assumed to be a political rather than artistic honour, and a reward for his untiring support of the Whigs, the party of Prime Minister Robert Walpole. Most of the leading writers, such as Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, ...

and Alexander Pope, were excluded from contention for the laureateship because they were Tories. Cibber's verses had few admirers even in his own time, and Cibber acknowledged cheerfully that he did not think much of them.Barker, p. 163 His 30 birthday odes for the royal family and other duty pieces incumbent on him as Poet Laureate came in for particular scorn, and these offerings would regularly be followed by a flurry of anonymous parodies

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its su ...

, some of which Cibber claimed in his ''Apology'' to have written himself. In the 20th century, D. B. Wyndham-Lewis and Charles Lee considered some of Cibber's laureate poems funny enough to be included in their classic "anthology of bad verse", ''The Stuffed Owl'' (1930). However, Cibber was at least as distinguished as his immediate four predecessors, three of whom were also playwrights rather than poets.

Dunce

Pamphlet wars

From the beginning of the 18th century, when Cibber first rose to be Rich's right-hand man at Drury Lane, his perceived opportunism and brash, thick-skinned personality gave rise to many barbs in print, especially against his patchwork plays. The early attacks were mostly anonymous, but Daniel Defoe and Tom Brown are suggested as potential authors. Later, Jonathan Swift, John Dennis andHenry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist, irony writer, and dramatist known for earthy humour and satire. His comic novel ''Tom Jones'' is still widely appreciated. He and Samuel Richardson are seen as founders ...

all lambasted Cibber in print. The most famous conflict Cibber had was with Alexander Pope.

Pope's animosity began in 1717 when he helped John Arbuthnot

John Arbuthnot FRS (''baptised'' 29 April 1667 – 27 February 1735), often known simply as Dr Arbuthnot, was a Scottish physician, satirist and polymath in London. He is best remembered for his contributions to mathematics, his member ...

and John Gay write a farce, ''Three Hours After Marriage

''Three Hours After Marriage'' was a restoration comedy, written in 1717 as a collaboration between John Gay, Alexander Pope and John Arbuthnot, though Gay was the principal author. The play is best described as a satirical farce, and among its ...

'', in which one of the characters, "Plotwell" was modelled on Cibber. Notwithstanding, Cibber put the play on at Drury Lane with himself playing the part of Plotwell, but the play was not well received. During the staging of a different play, Cibber introduced jokes at the expense of ''Three Hours After Marriage'', while Pope was in the audience. Pope was infuriated, as was Gay who got into a physical fight with Cibber on a subsequent visit to the theatre. Pope published a pamphlet satirising Cibber, and continued his literary assault for the next 25 years.

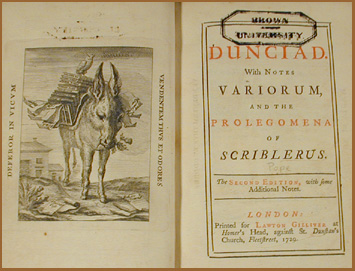

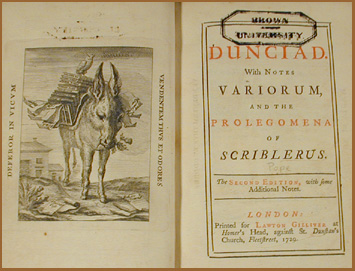

In the first version of his landmark literary satire ''

In the first version of his landmark literary satire ''Dunciad

''The Dunciad'' is a landmark, mock-heroic, narrative poem by Alexander Pope published in three different versions at different times from 1728 to 1743. The poem celebrates a goddess Dulness and the progress of her chosen agents as they bring ...

'' (1728), Pope referred contemptuously to Cibber's "past, vamp'd, future, old, reviv'd, new" plays, produced with "less human genius than God gives an ape". Cibber's elevation to laureateship in 1730 further inflamed Pope against him. Cibber was selected for political reasons, as he was a supporter of the Whig government of Robert Walpole, while Pope was a Tory. The selection of Cibber for this honour was widely seen as especially cynical coming at a time when Pope, Gay, Thomson, Ambrose Philips

Ambrose Philips (167418 June 1749) was an English poet and politician. He feuded with other poets of his time, resulting in Henry Carey bestowing the nickname " Namby-Pamby" upon him, which came to mean affected, weak, and maudlin speech or ver ...

, and Edward Young

Edward Young (c. 3 July 1683 – 5 April 1765) was an English poet, best remembered for '' Night-Thoughts'', a series of philosophical writings in blank verse, reflecting his state of mind following several bereavements. It was one of the mo ...

were all in their prime. As one epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two mille ...

of the time put it:

Pope, mortified by the elevation of Cibber to laureateship and incredulous at what he held to be the vainglory of his ''Apology'' (1740), attacked Cibber extensively in his poetry.

Cibber replied mostly with good humour to Pope's aspersions ("some of which are in conspicuously bad taste", as Lowe points out), until 1742 when he responded in kind in "A Letter from Mr. Cibber, to Mr. Pope, inquiring into the motives that might induce him in his Satyrical Works, to be so frequently fond of Mr. Cibber's name". In this pamphlet, Cibber's most effective ammunition came from a reference in Pope's ''Epistle to Arbuthnot'' (1735) to Cibber's "whore", which gave Cibber a pretext for retorting in kind with a scandalous anecdote about Pope in a brothel

A brothel, bordello, ranch, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in sexual activity with prostitutes. However, for legal or cultural reasons, establishments often describe themselves as massage parlors, bars, strip clubs, body rub p ...

. "I must own", wrote Cibber, "that I believe I know more of your whoring than you do of mine; because I don't recollect that ever I made you the least Confidence of my Amours, though I have been very near an Eye-Witness of Yours." Since Pope was around four and a half feet tall and hunchbacked due to a tubercular infection of the spine he contracted when young, Cibber regarded the prospect of Pope with a woman as something humorous, and he speaks mockingly of the "little-tiny manhood" of Pope. For once the laughers were on Cibber's side, and the story "raised a universal shout of merriment at Pope's expense". Pope made no direct reply, but took one of the most famous revenges in literary history. In the revised ''Dunciad'' that appeared in 1743, he changed his hero, the King of Dunces, from Lewis Theobald

Lewis Theobald (baptised 2 April 1688 – 18 September 1744), English textual editor and author, was a landmark figure both in the history of Shakespearean editing and in literary satire. He was vital for the establishment of fair texts for Shak ...

to Colley Cibber.

King of Dunces

The derogatory allusions to Cibber in consecutive versions of Pope's

The derogatory allusions to Cibber in consecutive versions of Pope's mock-heroic

Mock-heroic, mock-epic or heroi-comic works are typically satires or parodies that mock common Classical stereotypes of heroes and heroic literature. Typically, mock-heroic works either put a fool in the role of the hero or exaggerate the heroic ...

''Dunciad'', from 1728 to 1743, became more elaborate as the conflict between the two men escalated, until, in the final version of the poem, Pope crowned Cibber King of Dunces. From being merely one symptom of the artistic decay of Britain, he was transformed into the demigod of stupidity, the true son of the goddess Dulness. Apart from the personal quarrel, Pope had reasons of literary appropriateness for letting Cibber take the place of his first choice of King, Lewis Theobald. Theobald, who had embarrassed Pope by contrasting Pope's impressionistic Shakespeare edition (1725) with Theobald's own scholarly edition (1726), also wrote Whig propaganda for hire, as well as dramatic productions which were to Pope abominations for their mixing of tragedy and comedy and for their "low" pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment. It was developed in England and is performed throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland and (to a lesser extent) in other English-speakin ...

and opera. However, Cibber was an even better King in these respects, more high-profile both as a political opportunist and as the powerful manager of Drury Lane, and with the crowning circumstance that his political allegiances and theatrical successes had gained him the laureateship. To Pope this made him an epitome of all that was wrong with British letters. Pope explains in the "Hyper-critics of Ricardus Aristarchus" prefatory to the 1743 ''Dunciad'' that Cibber is the perfect hero for a mock-heroic parody, since his ''Apology'' exhibits every trait necessary for the inversion of an epic hero. An epic hero must have wisdom, courage, and chivalric love, says Pope, and the perfect hero for an anti-epic therefore should have vanity, impudence, and debauchery. As wisdom, courage, and love combine to create magnanimity in a hero, so vanity, impudence, and debauchery combine to make buffoonery for the satiric hero. His revisions, however, were considered too hasty by later critics who pointed out inconsistent passages that damaged his own poem for the sake of personal vindictiveness.Ashley, pp. 146–150; Barker, pp. 218–219

Writing about the degradation of taste brought on by theatrical effects, Pope quotes Cibber's own ''confessio'' in the ''Apology'':

Pope's notes call Cibber a hypocrite, and in general the attacks on Cibber are conducted in the notes added to the ''Dunciad'', and not in the body of the poem. As hero of the ''Dunciad'', Cibber merely watches the events of Book II, dreams Book III, and sleeps through Book IV.

Once Pope struck, Cibber became an easy target for other satirists. He was attacked as the epitome of morally and aesthetically bad writing, largely for the sins of his autobiography. In the ''Apology'', Cibber speaks daringly in the first person and in his own praise. Although the major figures of the day were jealous of their fame, self-promotion of such an overt sort was shocking, and Cibber offended Christian humility as well as gentlemanly modesty. Additionally, Cibber consistently fails to see fault in his own character, praises his vices, and makes no apology for his misdeeds; so it was not merely the fact of the autobiography, but the manner of it that shocked contemporaries. His diffuse and chatty writing style, conventional in poetry and sometimes incoherent in prose, was bound to look even worse in contrast to stylists like Pope. Henry Fielding satirically tried Cibber for murder of the English language in the 17 May 1740 issue of ''The Champion''. The Tory wits were altogether so successful in their satire of Cibber that the historical image of the man himself was almost obliterated, and it was as the King of Dunces that he came down to posterity.

Writing about the degradation of taste brought on by theatrical effects, Pope quotes Cibber's own ''confessio'' in the ''Apology'':

Pope's notes call Cibber a hypocrite, and in general the attacks on Cibber are conducted in the notes added to the ''Dunciad'', and not in the body of the poem. As hero of the ''Dunciad'', Cibber merely watches the events of Book II, dreams Book III, and sleeps through Book IV.

Once Pope struck, Cibber became an easy target for other satirists. He was attacked as the epitome of morally and aesthetically bad writing, largely for the sins of his autobiography. In the ''Apology'', Cibber speaks daringly in the first person and in his own praise. Although the major figures of the day were jealous of their fame, self-promotion of such an overt sort was shocking, and Cibber offended Christian humility as well as gentlemanly modesty. Additionally, Cibber consistently fails to see fault in his own character, praises his vices, and makes no apology for his misdeeds; so it was not merely the fact of the autobiography, but the manner of it that shocked contemporaries. His diffuse and chatty writing style, conventional in poetry and sometimes incoherent in prose, was bound to look even worse in contrast to stylists like Pope. Henry Fielding satirically tried Cibber for murder of the English language in the 17 May 1740 issue of ''The Champion''. The Tory wits were altogether so successful in their satire of Cibber that the historical image of the man himself was almost obliterated, and it was as the King of Dunces that he came down to posterity.

Plays

The plays below were produced at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, unless otherwise stated. The dates given are of first known performance. * ''Love's Last Shift

''Love's Last Shift, or The Fool in Fashion'' is an English Restoration comedy by Colley Cibber from 1696. The play is regarded as an early herald of a shift in audience tastes away from the intellectualism and sexual frankness of Restoratio ...

'' or "The Fool in Fashion" (Comedy, January 1696)

* ''Woman's Wit'' (Comedy, 1697)

* ''Xerxes'' (Tragedy, Lincoln's Inn Fields, 1699)

* '' The Tragical History of King Richard III'' (Tragedy, 1699)

* ''Love Makes a Man

''Love Makes A Man; Or, The Fop's Fortune is a 1700 comedy play by the English writer Colley Cibber. It borrows elements from two Jacobean plays ''The Elder Brother'' and '' The Custom of the Country'' by John Fletcher.

It was originally stage ...

'' or " The Fop's Fortune" (Comedy, December 1700)

* ''The School Boy'' (Comedy, advertised for 24 October 1702)

* ''She Would and She Would Not

''She Would and She Would Not'' is a 1702 comedy play by the English actor-writer Colley Cibber.

The original Drury Lane cast included Cibber as Don Manuel, Benjamin Husband as Don Philip, John Mills as Octavio, William Pinkethman as Trappanti, ...

'' (Comedy, 26 November 1702)

* ''The Careless Husband

''The Carless Husband'' is a comedy play by the English writer Colley Cibber. It premiered at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on 7 December 1704. The original cast featured Cibber as Lord Foppington, George Powell as Lord Morelove, Robert Wilks as ...

'' (Comedy, 7 December 1704)

* ''Perolla and Izadora'' (Tragedy, 3 December 1705)

* ''The Comical Lovers'' (Comedy, Haymarket, 4 February 1707)

* ''The Double Gallant

''The Double Gallant'' is a 1707 comedy play by the British writer Colley Cibber.

It was originally performed on 1 November 1707 at the Queen's Theatre in the Haymarket with a cast that included Benjamin Johnson as Sir Solomon, Barton Booth a ...

'' (Comedy, Haymarket, 1 November 1707)

* ''The Lady's Last Stake'' OR "The Wife's resentment" (Comedy, Haymarket, 13 December 1707)

* '' The Rival Fools'' oe "Wit, at several Weapons"(Comedy, 11 January 1709)

* ''The Rival Queans'' (Comical-Tragedy, Haymarket, 29 June 1710), a parody of Nathaniel Lee

Nathaniel Lee (c. 1653 – 6 May 1692) was an English dramatist. He was the son of Dr Richard Lee, a Presbyterian clergyman who was rector of Hatfield and held many preferments under the Commonwealth; Dr Lee was chaplain to George Monck, afterw ...

's ''The Rival Queens''.

* ''Ximena'' or "The Heroic Daughter"(Tragedy, 28 November 1712)

* ''Venus and Adonis'' (Masque, 12 March 1715)

* ''Myrtillo'' (Pastoral, 5 November 1715)

* '' The Non-Juror'' (Comedy, 6 December 1717)

* ''The Refusal

"The Refusal" (German: "Die Abweisung"), also known as "Unser Städtchen liegt …", is a short story by Franz Kafka. Written in the autumn of 1920, it was not published in Kafka's lifetime.

Overview

The story of "Die Abweisung" involves the narr ...

'' or " The Ladies Philosophy"(Comedy, 14 February 1721)

* ''Caesar in Egypt

''Caesar in Egypt'' is a 1724 tragedy by the British writer Colley Cibber. It is inspired by Pierre Corneille's 1642 French play '' The Death of Pompey'' about Julius Caesar's intervention in the Egyptian Civil War between Cleopatra and her bro ...

'' (Tragedy, 9 December 1724)

* ''The Provoked Husband

''The Provoked Husband'' is a 1728 comedy play by the British writer and actor Colley Cibber, based on a fragment of play written by John Vanbrugh. It is also known by the longer title ''The Provok'd Husband: or, a Journey to London''.

Vanbrug ...

'' (with Vanbrugh

Sir John Vanbrugh (; 24 January 1664 (baptised) – 26 March 1726) was an English architect, dramatist and herald, perhaps best known as the designer of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard. He wrote two argumentative and outspoken Restorat ...

, comedy, 10 January 1728)

* '' Love in a Riddle'' (Pastoral, 7 January 1729)

* ''Damon and Phillida'' (Pastoral Farce, Haymarket, 16 August 1729)

* ''Papal Tyranny in the Reign of King John'' (Tragedy, Covent Garden, 15 February 1745)

''Bulls and Bears'', a farce performed at Drury Lane on 2 December 1715, was attributed to Cibber but was never published. ''The Dramatic Works of Colley Cibber, Esq.'' (London, 1777) includes a play called ''Flora, or Hob in the Well'', but it is not by Cibber. ''Hob, or the Country Wake. A Farce. By Mr. Doggett'' was attributed to Cibber by William Chetwood in his ''General History of the Stage'' (1749), but John Genest

John Genest (1764–1839) was an English clergyman and theatre historian.

Life

He was the son of John Genest of Dunker's Hill, Devon. He was educated at Westminster School, entered 9 May 1780 as a pensioner at Trinity College, Cambridge, and ...

in ''Some Account of the English Stage'' (1832) thought it was by Thomas Doggett. Other plays attributed to Cibber but probably not by him include ''Cinna's Conspiracy'', performed at Drury Lane on 19 February 1713, and ''The Temple of Dullness'' of 1745.Ashley, pp. 78–79, 206; Barker, pp. 266–267

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cibber, Colley 1671 births 1757 deaths Actor-managers British Poets Laureate English male dramatists and playwrights English male poets English male stage actors English memoirists English theatre directors 18th-century English businesspeople 17th-century English male actors 18th-century English male actors 17th-century English male writers 18th-century English non-fiction writers 18th-century English male writers 17th-century English dramatists and playwrights 18th-century British dramatists and playwrights People educated at The King's School, Grantham English people of Danish descent English male non-fiction writers 17th-century theatre managers 18th-century theatre managers