Charles Hoskins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Henry Hoskins (1851-1926) was an Australian industrialist, who was significant in the development of the iron and steel industry in Australia.

Charles Hoskins joined his elder brother George (1847-1926) in Sydney in 1876, operating a small engineering workshop at Hay Street, Ultimo. Around 1889, their firm, G & C Hoskins, moved to larger premises in Wattle Street, Ultimo and established a foundry, pipe-works and boiler shop. This plant was expanded in 1902. It was pipe manufacturing that would lead to their success.

Charles Hoskins joined his elder brother George (1847-1926) in Sydney in 1876, operating a small engineering workshop at Hay Street, Ultimo. Around 1889, their firm, G & C Hoskins, moved to larger premises in Wattle Street, Ultimo and established a foundry, pipe-works and boiler shop. This plant was expanded in 1902. It was pipe manufacturing that would lead to their success.

In the 1890s, G & C Hoskins opened a branch in Melbourne to make steel pipes.

In 1898, after negotiations, G & C Hoskins and the Melbourne firm

In the 1890s, G & C Hoskins opened a branch in Melbourne to make steel pipes.

In 1898, after negotiations, G & C Hoskins and the Melbourne firm

G & C Hoskins became the owners of the blast furnace, a colliery, coke ovens, steelmaking furnaces, rolling mills, an iron ore mine at

G & C Hoskins became the owners of the blast furnace, a colliery, coke ovens, steelmaking furnaces, rolling mills, an iron ore mine at

The Lithgow plant was in urgent need of expansion; the Hoskins brothers had the financial means to do so and experience of operating a heavy industrial enterprise. The new management immediately closed down marginal operations such as the sheet mill and galvanising plant—although these were to be reopened later—and began to renovate and rearrange the existing operations. An early improvement made was to introduce electric lighting; the works had previously relied upon 'slush lamps' for internal lighting.

The company had modernised and upgraded the mine at Carcoar, by mid 1909, and opened a second iron ore mine at Tallawang in 1911. They also started to use dolomite from the limestone quarry at

The Lithgow plant was in urgent need of expansion; the Hoskins brothers had the financial means to do so and experience of operating a heavy industrial enterprise. The new management immediately closed down marginal operations such as the sheet mill and galvanising plant—although these were to be reopened later—and began to renovate and rearrange the existing operations. An early improvement made was to introduce electric lighting; the works had previously relied upon 'slush lamps' for internal lighting.

The company had modernised and upgraded the mine at Carcoar, by mid 1909, and opened a second iron ore mine at Tallawang in 1911. They also started to use dolomite from the limestone quarry at  Sandford had left a half-completed 24-inch rolling mill—for rolling heavy sections such as rails—but, when the new management completed it and tried to use it, it broke down. Hoskins imported parts for this mill, including a more powerful steam engine to drive it, and reworked its design to create a 27-inch mill. New reheating furnaces were built to suit rail rolling. It would take until 1911 for Lithgow to produce the first steel rails made in Australia. The works won contracts to supply rails for the new

Sandford had left a half-completed 24-inch rolling mill—for rolling heavy sections such as rails—but, when the new management completed it and tried to use it, it broke down. Hoskins imported parts for this mill, including a more powerful steam engine to drive it, and reworked its design to create a 27-inch mill. New reheating furnaces were built to suit rail rolling. It would take until 1911 for Lithgow to produce the first steel rails made in Australia. The works won contracts to supply rails for the new

The original decision to site an ironworks at Lithgow in 1875, was based upon the existence of coal and a relatively small iron ore deposit nearby at Mount Wilson. This ore deposit was inadequate to feed even the first Lithgow blast furnace. After blast furnace operation recommenced at Lithgow in 1907, ore had to be brought from further away, from

The original decision to site an ironworks at Lithgow in 1875, was based upon the existence of coal and a relatively small iron ore deposit nearby at Mount Wilson. This ore deposit was inadequate to feed even the first Lithgow blast furnace. After blast furnace operation recommenced at Lithgow in 1907, ore had to be brought from further away, from

The BHP works at

The BHP works at  The newer and larger BHP works could produce larger quantities of rolled steel products of a higher quality, at a lower cost of production. Newcastle's seaport location brought access to virtually inexhaustible amounts of very high-grade iron ore from its mine at

The newer and larger BHP works could produce larger quantities of rolled steel products of a higher quality, at a lower cost of production. Newcastle's seaport location brought access to virtually inexhaustible amounts of very high-grade iron ore from its mine at

The family moved often; their choices of housing in Sydney reflected the family's rapidly increasing prosperity. During the 1880s, they lived first at 'Exeter Terrace' on Crystal Street, Petersham, then on Macauley Street,

The family moved often; their choices of housing in Sydney reflected the family's rapidly increasing prosperity. During the 1880s, they lived first at 'Exeter Terrace' on Crystal Street, Petersham, then on Macauley Street,

Early life

Charles Hoskins was born on 26 March 1851 in the City of London, to John Hoskins, gunsmith, and his wife Wilmot Eliza, née Thompson. He emigrated with his family to Melbourne as a small child in 1853, and all his education occurred in Melbourne. After his father's death, the family moved toSmythesdale

Smythesdale is a town in Victoria, Australia. The town is located on the Glenelg Highway. Most of the town is located in the Golden Plains Shire local government area; however, a small section lies in the Shire of Pyrenees. Smythesdale is west ...

, near Ballarat

Ballarat ( ) is a city in the Central Highlands (Victoria), Central Highlands of Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia. At the 2021 Census, Ballarat had a population of 116,201, making it the third largest city in Victoria. Estimated resid ...

. Hoskins began work as a mail boy, tried his luck on the goldfields, and worked as an assistant in an ironmongery store in Bendigo

Bendigo ( ) is a city in Victoria, Australia, located in the Bendigo Valley near the geographical centre of the state and approximately north-west of Melbourne, the state capital.

As of 2019, Bendigo had an urban population of 100,991, makin ...

.

Sydney

Charles Hoskins joined his elder brother George (1847-1926) in Sydney in 1876, operating a small engineering workshop at Hay Street, Ultimo. Around 1889, their firm, G & C Hoskins, moved to larger premises in Wattle Street, Ultimo and established a foundry, pipe-works and boiler shop. This plant was expanded in 1902. It was pipe manufacturing that would lead to their success.

Charles Hoskins joined his elder brother George (1847-1926) in Sydney in 1876, operating a small engineering workshop at Hay Street, Ultimo. Around 1889, their firm, G & C Hoskins, moved to larger premises in Wattle Street, Ultimo and established a foundry, pipe-works and boiler shop. This plant was expanded in 1902. It was pipe manufacturing that would lead to their success.

Innovation and success

A breakthrough came when they began to win contracts for the Sydney water supply mains. This was to provide a steady flow of work through their Ultimo factory for a number of years after 1892. In 1904, the other major pipe manufacturer in the Sydney market, Pope & Maher, failed; G & C Hoskins were left as the dominant supplier in that market. From 1911, they opened a second facility atRhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

, to manufacture cast-iron pipes.

The Hoskins Brothers were not only efficient; they were also innovative, patenting a number of their ideas for improving pipes and their manufacturing processes.

Free trade and industry protection

The issue of protection against imports was the principal political division of late 19th-century Australia. In New South Wales, almost alone of the Australian colonies, there was widespread support forfree trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

. A growing force was the Labor Party; it somewhat favoured protection, as a means to maintain relatively high wages, but also advocated nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

of major industries, complicating its position.

Politically, Hoskins was for Federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

, free trade between the Australian colonies, and uniform tariff protection against imports from other countries. The Chamber of Manufacturers of New South Wales had been established in 1885—Hoskins was an early and prominent member—with its primary supporters focusing on lobbying for protection, in direct opposition to the "Free Traders" led by Sir Henry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, (27 May 1815 – 27 April 1896) was a colonial Australian politician and longest non-consecutive Premier of the Colony of New South Wales, the present-day state of New South Wales in the Commonwealth of Australia. He has be ...

and later George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales f ...

. This oppositional approach made little progress, with Free Trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

governments holding power in New South Wales, except between 1891 and 1895. In 1895, Charles Hoskins was the first President of a reconstituted Chamber of Manufacturers that aimed to advance industry, without partisan political lobbying, an approach that it has followed since that time.

Free Traders were not opposed to a local iron and steel industry; their view was that it could come about, without a protective tariff. The N.S.W. Government had offered a large contract for locally made steel rails. A leading Free Trade businessman and politician, Joseph Mitchell

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

won the contract, in 1897, but died before he could build his planned large iron and steel works near Wallerawang

Wallerawang is a small township in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia. It is located approximately northwest of Lithgow, New South Wales, Lithgow adjacent to the Great Western Highway. It is also located on the Main Western ra ...

. G & C Hoskins also tendered, unsuccessfully. It was an early sign of an interest in entering the iron and steel industry. However, in 1899, when William Sandford

William Sandford (26 September 1841 – 29 May 1932) was an English-Australian ironmaster, who is widely regarded as the father of the modern iron and steel industry in Australia.

Early life in England

Sandford was born at Torrington in ...

attempted to interest Charles Hoskins in buying the Eskbank works at Lithgow, the offer was declined.

Charles Hoskins was a Protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

but also—through lack of other options—a major user of imported iron and steel. After his friend and fellow protectionist, William Sandford, commenced production of pig iron at Lithgow, in May 1907, G & C Hoskins became one of Sandford's major customers.

Interstate expansion

In the 1890s, G & C Hoskins opened a branch in Melbourne to make steel pipes.

In 1898, after negotiations, G & C Hoskins and the Melbourne firm

In the 1890s, G & C Hoskins opened a branch in Melbourne to make steel pipes.

In 1898, after negotiations, G & C Hoskins and the Melbourne firm Mephan Ferguson

Mephan Ferguson (25 July 1843 – 2 November 1919) was an Australian manufacturer, particularly of water supply pipes, notably for the pipeline to the Western Australian goldfields. He was born in Falkirk, Scotland. He immigrated with his paren ...

shared the contract to manufacture and lay 60,000 lengths of pipe over the 350 miles (563 km) from Perth to Coolgardie, for the water-supply scheme designed by C. Y. O'Connor

Charles Yelverton O'Connor, (11 January 1843 – 10 March 1902), was an Irish engineer who is best known for his work in Western Australia, especially the construction of Fremantle Harbour, thought to be impossible, and the Goldfields Water Sup ...

. This allowed the Hoskins' firm to further increase its technical capabilities in pipe manufacturing, as a result of the collaboration with the leading Melbourne firm and the purchase of their patent rights for New South Wales. Hoskins' share of the contract was worth around £500,000.

The contract for the pipeline in Western Australia stipulated that the pipes were to be manufactured in that state, and that all would be to Mephan Ferguson's design using an ingenious 'rivetless' locking bar. The steel for the pipes for the Coolgardie Water Scheme was imported but the Hoskins' share of the pipes were fabricated at a factory that the Hoskins established at Midland Junction

Midland is a suburb in the Perth metropolitan region, as well as the regional centre for the City of Swan local government area that covers the Swan Valley and parts of the Darling Scarp to the east. It is situated at the intersection of Gr ...

, which was reported to employ 200 workers. Ferguson made his share of the pipes at another factory in Perth, reported at the time as 'Falkirk', now Maylands.

After completion of the pipeline to the Goldfields

Goldfield or Goldfields may refer to:

Places

* Goldfield, Arizona, the former name of Youngberg, Arizona, a populated place in the United States

* Goldfield, Colorado, a community in the United States

* Goldfield, Iowa, a city in the United State ...

, the Hoskins established a works, on a block lying between Wellington and Murray Streets in Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

, and won other work associated with the reticulation of water in Western Australia.

In November 1923, the company opened a steel pipe plant at South Brisbane

South Brisbane is an inner southern suburb in the City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. In the , South Brisbane had a population of 7,196 people.

Geography

The suburb is on the southern bank of the Brisbane River, bounded to the north-west, ...

.

Lithgow

Failure of William Sandford Limited

In December 1907, there was a crisis when the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney took over the assets of William Sandford Limited, owners of the Eskbank Ironworks at Lithgow, including its nearly-new modern blast furnace. It was Charles Hoskins, one ofWilliam Sandford

William Sandford (26 September 1841 – 29 May 1932) was an English-Australian ironmaster, who is widely regarded as the father of the modern iron and steel industry in Australia.

Early life in England

Sandford was born at Torrington in ...

's closest friends, one of his largest customers, one of the few outside shareholders of William Sandford Limited, and a fellow protectionist, who stepped in to acquire the assets and keep the works operating.

Taking over from William Sandford

G & C Hoskins became the owners of the blast furnace, a colliery, coke ovens, steelmaking furnaces, rolling mills, an iron ore mine at

G & C Hoskins became the owners of the blast furnace, a colliery, coke ovens, steelmaking furnaces, rolling mills, an iron ore mine at Coombing Park

Coombing Park is a farming property situated in western New South Wales just off the Mid-Western Highway about 5 km west of Carcoar, 260 km west of Sydney and 54 km south-west of Bathurst. The property is of considerable note bec ...

near Carcoar

Carcoar is a town in the Central West (New South Wales), Central West region of New South Wales, Australia, in Blayney Shire. In 2016, the town had a population of 200 people. It is situated just off the Mid-Western Highway 258 km west of ...

, an iron ore lease near Cadia, and 400 acres of freehold land at Lithgow, as well as Sandford's house on his 2000-acre estate, 'Eskroy Park', near Bowenfels.

Charles Hoskins relocated to Lithgow, to manage the Eskbank works, assisted his two elder sons, Guildford and Cecil

Cecil may refer to:

People with the name

* Cecil (given name), a given name (including a list of people and fictional characters with the name)

* Cecil (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Canada

*Cecil, Alberta, ...

. Charles's elder brother George and George's three sons (George jnr, Leslie, and Harold) managed the pipe manufacturing business, which was about to undergo a large expansion involving the opening of a new pipe plant at Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

in 1911.

As for the management team, Sandford, his two sons, and their reliable and competent General Manager, William Thornley, were lost to the Hoskins, but most of the line management came over, which was crucial to the Hoskins' subsequent success.

William Sandford Limited had been a large enterprise employing over 700 workers. Although notionally a public company, it had been run more like the private company of the Sandford family, who held nearly all the company's shares. Sandford had managed the company in an idiosyncratic manner. Sandford had employed his workers under contracts, with different wage rates in different parts of the works.

Upon taking over, the businesslike Hoskins found the account books in a mess. The costs of production were difficult to identify and understand but turned out to be higher than expected. The Lithgow works had been making a loss, which became clear within a year after the take over.

Industrial strife and personal disputes

Charles Hoskins' views on industrial relations were very different to those ofWilliam Sandford

William Sandford (26 September 1841 – 29 May 1932) was an English-Australian ironmaster, who is widely regarded as the father of the modern iron and steel industry in Australia.

Early life in England

Sandford was born at Torrington in ...

. Hoskins had a more belligerent personality, not given to compromise. He was also under pressure to turn around a failing enterprise.

As Hoskins prepared to take over the works from Sandford, he made a generous gift to workers facing a bleak Christmas of 1907, following the shutdown of the works. Any initial goodwill did not last, when Hoskins attempted to move from contract arrangements to day labour wages, in 1908, and to lower the overall wage paid to his workers. He closed the works for five weeks in July 1908, ostensibly to carry out repairs, but later was found guilty of deliberately engineering a lock out and fined.

Matters came to a climax at the end of August 1911, when during a bitter and sometimes violent company-wide strike—following Hoskins use of strikebreaking 'scab' labour in his coal mine to keep the works operating—Hoskins and his sons, Henry and Cecil, were besieged by rock-throwing workers and his motor car was destroyed by the rioters. The blast furnace was shutdown briefly.

Perhaps as a result of the strain he was under, earlier in August 1911, Charles Hoskins had made some ungracious public remarks—about the previous owner, William Sandford

William Sandford (26 September 1841 – 29 May 1932) was an English-Australian ironmaster, who is widely regarded as the father of the modern iron and steel industry in Australia.

Early life in England

Sandford was born at Torrington in ...

, and his management of the Lithgow plant—resulting in a bitter public dispute between the two old friends. By then, both men felt that they had been deceived by the other; Sandford believed that Hoskins had connived in his downfall and besmirched his reputation and Hoskins believed that Sandford had not disclosed that the Lithgow works had been losing money. The two men also had very different views of their workforce; Hoskins had little of Sandford's paternalistic concern for his workers and was more concerned about profits.

The strike continued for another nine months—an uneasy industrial peace resulted from a compromise outcome in April 1912—but Hoskins did achieve a wage cut.

Lithgow and its coal and ore mines were never to be harmonious workplaces, once Hoskins took over; there were numerous disputes and strikes, right to the end. The same was true of the G & C Hoskins plants in Sydney.

Politics, royal commission and dispute with N.S.W. Government

The contract with the N.S.W. Government that Hoskins had inherited from William Sandford provided the underlying economic basis of the Lithgow plant. Hoskins own pipe plants consumed a portion Lithgow's iron, but not enough to justify its existence. Nonetheless, by early 1909, Hoskins was already critical of the contractual arrangements with the N.S.W. Government, his main customer. Hoskins was required to buy the scrap iron originating from the railways and other government entities. He contended that the contract prices for the scrap were significantly higher than he could pay for similar material in the open market. However, the threat to the exclusive contract would not come from the company, but from the N.S.W. Government itself. At the election of October 1910, the first Labor government of N.S.W. came to power, led byJames McGowen

James Sinclair Taylor McGowen (16 August 1855 – 7 April 1922) was an Australian politician. He served as premier of New South Wales from 1910 to 1913, the first member of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) to hold the position, and was a key f ...

. It had been Labor and McGowan, who had triggered the final collapse of William Sandford Limited, in October 1907, when they joined forces with George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales f ...

to insist that a critical government loan—intended to keep the cash-strapped company operating—take absolute precedence of security, over the company's existing commercial bank loans. At that time, Labor favoured a policy of nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

of heavy industry and was ambivalent concerning the future of companies such as G. & C. Hoskins. Labor, as the political wing of the organised labour movement, could not have been sympathetic to Hoskins' hard-nosed approach to industrial relations. McGowen's government's attitude to Hoskins and his Lithgow works would be very different to that of the previous premier, Charles Wade

Sir Charles Gregory Wade KCMG, KC, JP (26 January 1863 – 26 September 1922) was Premier of New South Wales – 21 October 1910. According to Percival Serle, "Wade was a public-spirited man of high character. His ability, honesty and coura ...

. Labor saw Hoskins as a supporter of Wade, and owed him no favours.

Hoskins had secured his first order for steel rails in May 1911. However, in the same year, the N.S.W. Government set up a Royal Commission to "''inquire as to the suitability of New South Wales ores for iron and steel manufacture, the cost of production from local ores, whether the Government's arrangements with Messrs. G. and C. Hoskins for supplies of iron and steel are beneficial to the Government, and the approximate cost of a plant capable of producing the iron and steel to be required in the future by the Commonwealth Government and the Governments of the different States.''"

The N.S.W. Government, through the Attorney-General William Holman

William Arthur Holman (4 August 1871 – 5 June 1934) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of New South Wales from 1913 to 1920. He came to office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (New South Wales Branch), Labor Party, ...

, appointed the manager of the Steel Company of Scotland, F.W. Paul, as the Royal Commissioner. His findings were highly critical of the existing arrangements, the quality of the products being supplied, that not all the steel supplied was made from Australian ores (some was German steel), and of Charles Hoskins himself. The last aspect of the findings was unsurprising, given Hoskins combative approach in giving his evidence and that he had clashed with the Royal Commissioner.

Hoskins' reaction was to assert that Royal Commission had been intended to justify nationalising the steel industry, which given its terms of reference is conceivable, but the Premier denied that. In late November 1911, as Hoskins was trying to resolve the lengthy industrial dispute at Lithgow, the N.S.W. Government—citing the stipulation that all the material should be the product of Australian ore—cancelled all its contracts with G. & C. Hoskins; this would have doomed all the Lithgow plant, except the blast furnace, to closure. The company responded in late December 1911, by initiating legal action, against the N.S.W. Government, stating that it was being "''condemned unheard''" in an unfair and unjust manner.

The company issued a writ in March 1912, and then filed its case in June 1912, claiming £150,000 in damages. In the meantime, other events were favourable to Hoskins; the industrial dispute ended in an uneasy peace, in April 1912, and, later in 1912, the company won a contract to supply rails and fishplates for the new Trans-Australian Railway

The Trans-Australian Railway, opened in 1917, runs from Port Augusta in South Australia to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, crossing the Nullarbor Plain in the process. As the only rail freight corridor between Western Australia and the easter ...

—after convincing the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

authorities that it could meet the product specification—and a large order of water pipes for the new national capital. The hearing of Hoskins' case was postponed until 1913. As time passed, pending the court hearing, the inadequacies of the plant at Lithgow—ultimately the root cause of the N.S.W. Government's dissatisfaction—were being rectified, as Hoskins rapidly expanded the plant and increased its both its capacity and capability.

By April 1913, the parties had reached an agreement, and the matter did not proceed to trial. Under the settlement, the original exclusive contract was not reinstated, but the company was not debarred from tendering to the N.S.W Government, which it did successfully in subsequent years. Labor still held office, when, in June 1913, McGowen was replaced as premier by his deputy, the same William Holman, who had been the Attorney-General and the driving force behind the Royal Commission. The new premier continued to justify the cancellation of the contract, based on the Royal Commissioner's findings but the government was by then faced with the adverse consequences for the workers of Lithgow—now that the industrial disputes were over.

The company's relations with the N.S.W. Government seem to have improved by 1915; the company won a N.S.W. Government tender for rails, and the price paid was significantly lower than previous prices for imported rails. For a time, there was active consideration of the N.S.W. Government purchasing the works, but it came to nothing.

Initial expansion and protection

As part of the rescue deal, C & C Hoskins took over Sandford's contract to supply the iron and steel needs of the New South Wales Government, extending its term to nine years from 1 January 1908. Unfortunately for its new owners, apart from the blast furnace, much the plant was antiquated or otherwise not ready to supply the Government with its needs, particularly steel rails. That was largely due to the failures of the Sandford period, but it was Hoskins who wore the consequences, when the N.S.W. Government cancelled the exclusive contract in late 1911. The long-sought protection of the iron and steel industry was finally introduced, from the first day of 1909, byAndrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician who served three terms as prime minister of Australia – from 1908 to 1909, from 1910 to 1913, and from 1914 to 1915. He was the leader of the Australian Labor Party ...

's Labor government, in the form of bounties to be paid under the ''Manufacturers' Encouragement Act'', which made it a condition that those benefitting from bounties would pay "''fair and reasonable wages''". The government paid a bonus of 12 s per ton from 1908 to 1914 and 8s per ton thereafter, until 1917, after which the industry would receive no further payments. The Lithgow plant was in urgent need of expansion; the Hoskins brothers had the financial means to do so and experience of operating a heavy industrial enterprise. The new management immediately closed down marginal operations such as the sheet mill and galvanising plant—although these were to be reopened later—and began to renovate and rearrange the existing operations. An early improvement made was to introduce electric lighting; the works had previously relied upon 'slush lamps' for internal lighting.

The company had modernised and upgraded the mine at Carcoar, by mid 1909, and opened a second iron ore mine at Tallawang in 1911. They also started to use dolomite from the limestone quarry at

The Lithgow plant was in urgent need of expansion; the Hoskins brothers had the financial means to do so and experience of operating a heavy industrial enterprise. The new management immediately closed down marginal operations such as the sheet mill and galvanising plant—although these were to be reopened later—and began to renovate and rearrange the existing operations. An early improvement made was to introduce electric lighting; the works had previously relied upon 'slush lamps' for internal lighting.

The company had modernised and upgraded the mine at Carcoar, by mid 1909, and opened a second iron ore mine at Tallawang in 1911. They also started to use dolomite from the limestone quarry at Havilah

Havilah ( ''Ḥăwīlāh'') refers to both a land and people in several books of the Bible; the one mentioned in , while the other is mentioned in .

Biblical mentions

In one case, Havilah is associated with the Garden of Eden, that mentioned in ...

, instead of importing it from England as Sandford had done. Sandford had left a half-completed 24-inch rolling mill—for rolling heavy sections such as rails—but, when the new management completed it and tried to use it, it broke down. Hoskins imported parts for this mill, including a more powerful steam engine to drive it, and reworked its design to create a 27-inch mill. New reheating furnaces were built to suit rail rolling. It would take until 1911 for Lithgow to produce the first steel rails made in Australia. The works won contracts to supply rails for the new

Sandford had left a half-completed 24-inch rolling mill—for rolling heavy sections such as rails—but, when the new management completed it and tried to use it, it broke down. Hoskins imported parts for this mill, including a more powerful steam engine to drive it, and reworked its design to create a 27-inch mill. New reheating furnaces were built to suit rail rolling. It would take until 1911 for Lithgow to produce the first steel rails made in Australia. The works won contracts to supply rails for the new Trans-Australian Railway

The Trans-Australian Railway, opened in 1917, runs from Port Augusta in South Australia to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, crossing the Nullarbor Plain in the process. As the only rail freight corridor between Western Australia and the easter ...

. and later, once again, the N.S.W. Government Railways.

Sandford's plans for Lithgow had provision for up to four blast furnaces. G & C Hoskins quickly built a second blast furnace—with its parts made at Hoskins' own works at Lithgow and Ultimo—which was almost identical to Sandford's, but slightly larger. This new furnace opened in 1913. They built a short rail line from the blast furnaces to the steel furnaces, allowing the pig iron to transferred in a molten state, using 30-ton capacity ladle cars. They added a new larger open hearth steel furnace that produced larger steel ingots to suit the new 27-inch mill. To match the increased production, more coke ovens were built.

By 1914, the Lithgow plant had been transformed into a viable iron and steel making operation.

First World War

Australia entered the First World War with a small but economically-viable iron and steel industry at Lithgow, a fortuitous circumstance because the country could no longer rely upon imports from Europe or America, for the duration of the war. Much of the credit for this belonged to Charles Hoskins. During the war, the Lithgow plant was put to use making special grades of steel unobtainable from Europe. In 1916, it madeferromanganese

Ferromanganese is a ferroalloy with high manganese content (high-carbon ferromanganese can contain as much as 80% Mn by weight). It is made by heating a mixture of the oxides MnO2 and Fe2O3, with carbon (usually as coal and coke) in either a bla ...

needed for armaments, using manganese ore from a mine near Grenfell. It supplied the nearby Lithgow Small Arms Factory

The Lithgow Small Arms Factory, or Lithgow Arms, is an Australian small arms manufacturing factory located in the town of Lithgow, New South Wales. It was created by the Australian Government in 1912 to ease reliance on the British for the sup ...

with steel for weapon manufacture. Charles Hoskins became personally involved in solving problems of wartime production. While the war was in progress, he was building a new branch railway line and an aerial ropeway

A material ropeway, ropeway conveyor (or aerial tramway in the US) is a subtype of gondola lift, from which containers for goods rather than passenger cars are suspended.

Description

Material ropeways are typically found around large mining conc ...

to open up a new iron ore quarry at Cadia.

However, by the time of the war, difficulties associated with the location of his plant at Lithgow had already become apparent to Hoskins, leading him to reconsider its long term future. Consequently, the further expansion of the Lithgow plant effectively ceased by the end of the war. Hoskins had offered to sell the plant to the N.S.W. Government in early 1914 but his offer was not taken up.

Difficulties, vision for the future, and sole control

Iron ore

The original decision to site an ironworks at Lithgow in 1875, was based upon the existence of coal and a relatively small iron ore deposit nearby at Mount Wilson. This ore deposit was inadequate to feed even the first Lithgow blast furnace. After blast furnace operation recommenced at Lithgow in 1907, ore had to be brought from further away, from

The original decision to site an ironworks at Lithgow in 1875, was based upon the existence of coal and a relatively small iron ore deposit nearby at Mount Wilson. This ore deposit was inadequate to feed even the first Lithgow blast furnace. After blast furnace operation recommenced at Lithgow in 1907, ore had to be brought from further away, from Coombing Park

Coombing Park is a farming property situated in western New South Wales just off the Mid-Western Highway about 5 km west of Carcoar, 260 km west of Sydney and 54 km south-west of Bathurst. The property is of considerable note bec ...

—near Carcoar

Carcoar is a town in the Central West (New South Wales), Central West region of New South Wales, Australia, in Blayney Shire. In 2016, the town had a population of 200 people. It is situated just off the Mid-Western Highway 258 km west of ...

—(up to May 1923), Tallawang (from 1911 to Feb. 1927) and Cadia (from 1918).

The ore from Carcoar was high in manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy use ...

and needed to be blended with other ore for some grades. The Tallawang ore was largely magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With the ...

but the grade was only around 42% iron and the deposit relatively small. The ore from Cadia was hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of . ...

with some magnetite but averaging only around 51% iron with a high silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

content; the silica content resulted in relatively large amounts of slag

Slag is a by-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and used metals. Broadly, it can be classified as ferrous (by-products of processing iron and steel), ferroalloy (by-product of ferroalloy production) or non-ferrous/base metals (by-prod ...

, when the ore was smelted, and increased the consumption of limestone flux.

New South Wales, although it possessed some widely dispersed smaller deposits of iron ore, was not well-endowed with large deposits. With two blast furnaces in operation at Lithgow, after 1913, not only did Hoskins need to rail his complex iron ores a considerable distance but his ore deposits had a limited life. This last aspect became more critical, once it was discovered that the ore deposit at Cadia—to which Lithgow's future was to be inextricably tied—contained a far lesser quantity of good-quality ore than had been estimated by the Government's geological surveyor.

G. & C. Hoskins explored and—in some cases—took out leases on other deposits of iron ore in New South Wales; one was close to the eastern side of the Main Southern Railway between Breadalbane and Cullerin

Cullerin is a small township in the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia. It is on the Old Hume Highway and Main South railway line in Upper Lachlan Shire. The Cullerin railway station opened in 1880 and closed in 1973. At the , ...

—mined sporadically from 1918, with the ore smelted at Lithgow—and others were near Crookwell

Crookwell is a small town located in the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia, in the Upper Lachlan Shire. At the , Crookwell had a population of 2,641. The town is at a relatively high altitude of 887 metres and there are several sn ...

, Michelago, Cumnock

Cumnock (Scottish Gaelic: ''Cumnag'') is a town and former civil parish located in East Ayrshire, Scotland. The town sits at the confluence of the Glaisnock Water and the Lugar Water. There are three neighbouring housing projects which lie just o ...

, Picton, Cudgegong near Mudgee

Mudgee is a town in the Central West (New South Wales), Central West of New South Wales, Australia. It is in the broad fertile Cudgegong River valley north-west of Sydney and is the largest town in the Mid-Western Regional Council Local gover ...

, and even as far from Lithgow as Tabulam

Tabulam is a rural village in the far north-east of New South Wales, Australia, 800 kilometres from the state capital, Sydney. Tabulam is located on the Bruxner Highway (Highway 44) between Tenterfield and Casino and on the Clarence River. Acco ...

.

Through Charles Hoskins' commercial intransigence—his unwillingness to renew the lease on the existing terms and conditions—the company lost access to its deposit at Carcoar in 1923, after extracting only about a third of its ore.

Charles Hoskins had believed that he did not need to pay a royalty to the landowner of Coombing Park

Coombing Park is a farming property situated in western New South Wales just off the Mid-Western Highway about 5 km west of Carcoar, 260 km west of Sydney and 54 km south-west of Bathurst. The property is of considerable note bec ...

and could just make a claim under a Miner's Right

The Miner's Right was introduced in 1855 in the colony of Victoria, replacing the Miner's Licence. Protests in 1853 at Bendigo with the formation of the Anti-Gold Licence Association and the rebellion of Eureka Stockade

The Eureka Rebellio ...

, following amendments made to the Mining Act in 1919. A costly court battle ensued, in which the Mining Warden's Court found that the ore body remained the landowner's private property. It was a pyrrhic victory, as Hoskins did not relent, and that was the end of iron ore mining at Carcoar.

Coking coal

Lithgow was a coal mining centre but only one of the mines, Oakey Park, produced coal that could produce coke, and even that was of marginal quality. As a temporary measure, coke was purchased, from theCommonwealth Oil Corporation Commonwealth Oil Corporation Limited was an English-owned Australian company associated with the production and refining of petroleum products derived from oil shale, during the early years of the 20th century. It is associated with Newnes, Hartley ...

, which made excellent coke at Newnes

Newnes (), an abandoned oil shale mining site of the Wolgan Valley, is located in the Central Tablelands region of New South Wales, Australia. The site that was operational in the early 20th century is now partly surrounded by Wollemi Nationa ...

. Hoskins opened new mines at Lithgow to obtain suitable coal. In 1916, Hoskins bought the Wongawilli Colliery and higher-quality coke was carried to Lithgow from the Illawarra by rail. "Wonga", a little saddle-tank engine, worked at Wongawilli, from 1916 to October 1927; it had first been used by the British and Tasmanian Charcoal Iron Company in 1876, as part of an earlier attempt to operate a blast furnace in Australia.

Transport

Lithgow was totally dependent upon rail transport. Until 1921, the railway west of Lithgow toward the ore mines was single track. Limestone, for use as smelting flux, needed to be carried fromBen Bullen

Ben Bullen is a small mountain village in the Central West of New South Wales, Australia. It is located on the Castlereagh Highway (almost) halfway between the small towns of Cullen Bullen and Capertee. In the , it recorded a population of 10 ...

and Havilah

Havilah ( ''Ḥăwīlāh'') refers to both a land and people in several books of the Bible; the one mentioned in , while the other is mentioned in .

Biblical mentions

In one case, Havilah is associated with the Garden of Eden, that mentioned in ...

, and later from Excelsior near Cullen Bullen. The cost of government-railway freight and sensitivity to increases in freight rates were unavoidable disadvantages of Lithgow's inland site and its distance from the ore and limestone quarries, and, after 1916, even some its coke production. From 1918, the company also paid the operating costs of a private railway line —Cadia Mine railway line

The Cadia Mine railway line is a closed and dismantled railway line in New South Wales, Australia. The 18.5 km (11.5 mile) long branch line started where it branched from the Main Western Railway line at Spring Hill.and ended at Cadia. Its main ...

—that ran from Cadia to exchange sidings at Spring Hill, from where the iron ore was brought by the government-owned railway to Lithgow.

Until 1910, rail traffic from Lithgow to the coast and Sydney was constrained by the single-track Lithgow Zig Zag

The Lithgow Zig Zag is a heritage-listed former zig zag railway line built near Lithgow on the Great Western Line of New South Wales in Australia. The zig zag line operated between 1869 and 1910, to overcome an otherwise insurmountable ...

. Even after the Zig Zag was replaced by the Ten Tunnels Deviation

The Ten Tunnels Deviation is a heritage-listed section of the Main Western Line between Newnes Junction and Zig Zag stations in Lithgow, New South Wales, Australia. It was designed and built by the New South Wales Government Railways and bui ...

(1910) and the line duplicated—including the Glenbrook Deviation (1913)—the distance from the coast and the gradients of the Western railway remained an issue. Banking engines were often needed to assist heavy freight trains over the mountains from Lithgow. Although Hoskins sought new sources of iron ore in other states, it would never be feasible to bring iron ore from a coastal port to Lithgow; in the longer term, the blast furnaces could not remain in operation at Lithgow.

Competition and product quality

The BHP works at

The BHP works at Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

opened in 1915. However, initially, Lithgow was not badly affected by competition, due to buoyant demand for steel and absence of import competition, during the First World War, and the government bonuses paid until 1917. That began to change once the war ended.

In the early 1920s, the young iron and steel industry in Australia found itself subject to intense competition from imports; this affected both Lithgow and Newcastle. However, BHP Newcastle works' new general manager, Essington Lewis

Essington Lewis, CH (13 January 18812 October 1961) was a prominent Australian industrialist. He was the Director-General of the Department of Munitions during World War II.

Biography

Early life

Essington Lewis was born in Burra, South Austr ...

, began a revival of that works, with a drive for efficiency and technical excellence; these efforts were successful to such an extent that by the early 1930s, Newcastle's costs and prices were low by global standards.

The newer and larger BHP works could produce larger quantities of rolled steel products of a higher quality, at a lower cost of production. Newcastle's seaport location brought access to virtually inexhaustible amounts of very high-grade iron ore from its mine at

The newer and larger BHP works could produce larger quantities of rolled steel products of a higher quality, at a lower cost of production. Newcastle's seaport location brought access to virtually inexhaustible amounts of very high-grade iron ore from its mine at Iron Knob

Iron Knob is a town in the Australian state of South Australia on the Eyre Peninsula immediately south of the Eyre Highway. At the 2006 census, Iron Knob and the surrounding area had a population of 199. The town obtained its name from its prox ...

; it allowed BHP to ship its products to Sydney and to interstate markets by sea, at lower cost than Lithgow could by rail. By the early 1920s, Newcastle had three blast furnaces, each of which was capable of making 50% more pig iron than both of Hoskins' Lithgow blast-furnaces combined.

BHP had access to more modern American technology and employed more professionals. Consequently, the quality of their steel was higher than Hoskins could make at Lithgow; in 2006 it was stated that, "''rail produced before 1914 and all Hoskins rail are generally regarded as being of dubious metallurgical composition''".

BHP also had vast cash flows from its Broken Hill silver-lead mines and smelters and, increasingly, from its profitable steel operations, with which to fund expansion and enhancement of its steelworks. Hoskins' family-owned company could not match BHP's ability to fund new capital works.

Labour

Lithgow always had relatively higher labour costs—a legacy of the industrial relations arrangements of William Sandford—and a relatively strong culture of unionism. Under competitive conditions, labour costs, poor labour relations, and strikes affected the long-term viability of the Lithgow plant. Wage rates at coastal locations were lower and unions perceived as less troublesome there.Vision for the future and sole control

Charles Hoskins began to see that his works at Lithgow had inherent problems that could not be resolved—even more so, after BHP's Newcastle works became a formidable competitor, from 1915 onward. He began to form a vision for a larger, more modern steelworks on the coast. In 1919, Charles Hoskins bought out his older brother George's share of the company G & C Hoskins, renaming the company Hoskins Iron and Steel Limited in July 1920. George retired, leaving Charles—by then in his late sixties—in sole charge of the destiny of the company.Plans for Port Kembla

Port Kembla

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ha ...

was selected, by the New South Wales Government at the end of 1898 as main port for area and in 1901 construction commenced on two breakwaters to protect two existing coal jetties at the site and to enclose an area of seabed that became the Outer Harbour. In 1908, it first became the site of heavy industry when the Electrolytic Refining and Smelting Company's plant was opened.

Hoskins had not been the first to consider establishing an iron and steel industry in the Illawarra

The Illawarra is a coastal region in the Australian state of New South Wales, nestled between the mountains and the sea. It is situated immediately south of Sydney and north of the South Coast region. It encompasses the two cities of Wollongo ...

. Two others had visions for such an industry, Joseph Mitchell

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

and Patrick Lahiff. Lahiff built a small blast furnace at Mount Pleasant and made some iron in 1872; he continued to advocate for an iron industry in the Illawarra, well into the 1890s.

The first association of Charles Hoskins with Port Kembla was in 1911, when there was talk of an ironworks at Port Kembla to process Tasmanian iron ore. In 1912, BHP planned to set up a large steelworks at Newcastle to exploit its vast South Australian iron ore deposits. Port Kembla was a site that BHP had considered before deciding upon Newcastle. That left the stage clear for Hoskins to take advantage of Port Kembla's seaport location, amidst the Southern Coalfields renown for their excellent hard coking coal.

Charles Hoskins' first step was when G & C Hoskins purchased the Wongawilli

Wongawilli is a southern suburb of Wollongong, Australia at the foot hills of the Illawarra escarpment. The word 'Wonga' is a native aboriginal word meaning native pigeon.

It contains a mixture of small rural properties and family homes. It ...

colliery at Dapto, in 1916, and established a cokeworks there. Hoskins had secured a source of coal and coke, close to a seaport at which iron ore could be unloaded. At first, the high-quality coke would be railed to Lithgow. However, he soon had more coke making capacity than he needed. Hoskins' approach to industrial relations was no different at Wongawilli and there were numerous strikes there.

In late 1920, the company acquired 380 acres of the Wentworth Estate

The Wentworth Estate is a private estate of large houses set in about woodland, in Runnymede, Surrey. It was commenced in the early 1920s. It lies within a gently undulating area of coniferous heathland and interlaces with the Wentworth Gol ...

, at Port Kembla, as the site for a steelworks. Also in 1920, Hoskins secured leases over an ore deposit near Mt Heemskirk in Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

, and apparently planned to ship the ore via rail to the port of Strahan. At an official event in Wollongong in April 1921, Hoskins spoke openly about his plans for a steelworks on the land that he had purchased at Port Kembla but also about what he wanted from the N.S.W. Government first, a lease for a private wharf at the harbour and a new railway line connecting Port Kembla to the Main Southern line.

In July 1923, he announced that a new integrated steelworks would be built at Port Kembla, without at this stage mentioning closing Lithgow; it was stated that Port Kembla was intended for the ‘interstate trade'. Later in 1923, the government announced the building of a rail line to Moss Vale

Moss Vale is a town in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, Australia, in the Wingecarribee Shire. It is located on the Illawarra Highway, which connects to Wollongong and the Illawarra coast via Macquarie Pass.

Moss Vale has several he ...

, which would allow limestone flux to be carried from Marulan

Marulan is the traditional lands of the Gundungurra people. It is a small town in the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia in the Goulburn Mulwaree Council local government area. It is located south-west of Sydney on the Hume Highway ...

. The company gained the lease for a private wharf at Port Kembla that would be completed in 1928.

Charles Hoskins retired as managing director in 1924, leaving the question of the future of the Lithgow works open. The construction of the new plant at Port Kembla would be for his successor as Chairman, his son Cecil Hoskins

Sir Cecil Harold Hoskins (1889–1971) was an Australian industrialist associated with the iron and steel industry. He is notable mainly for the establishment of the steel industry at Port Kembla, the company Australian Iron & Steel, and its sub ...

. His other son A. Sidney Hoskins would take charge of the Lithgow Steelworks. Together the two sons were co-Managing Directors of the company, which after their father's death would gradually transfer operations from the old works to the new.

Family, homes, and personal life

Although his father had died when he was young, Charles Hoskins was not an orphan, as his obituary would incorrectly state; his mother, Wilmot Eliza Hoskins, lived until 1896. He also had an uncle, William Hoskins, in Australia, as well as two brothers, George John Hoskins (1847-1926)—his business partner—and Thomas, and at least one sister. Although Thomas was not initially involved in G & C Hoskins, he later became the firm's Melbourne representative and later the manager of the works at Midland Junction, in Western Australia. Charles married Emily Wallis (1861-1928) on 22 December 1881. They raised eight children; sons Henry Guildford (1887-1916), Cecil Harold later Sir Cecil (1889-1971), Arthur Sidney, known as Sid, (1892-1959), and daughters, Florence Maud, later Mrs. F.A. Crago (1882-1973), Wilmot Elsie, later Mrs F.A. Weisener (1884-1964), Hilda Beatrice (1893-1912), Nellie Constance (1894-1914), and Kathleen Gertrude, later Mrs E.C. Mackey (1900-1950). Another daughter, Emily May (b.1886), died at five months. The family moved often; their choices of housing in Sydney reflected the family's rapidly increasing prosperity. During the 1880s, they lived first at 'Exeter Terrace' on Crystal Street, Petersham, then on Macauley Street,

The family moved often; their choices of housing in Sydney reflected the family's rapidly increasing prosperity. During the 1880s, they lived first at 'Exeter Terrace' on Crystal Street, Petersham, then on Macauley Street, Leichhardt Leichhardt may refer to:

* Division of Leichhardt, electoral District for the Australian House of Representatives

* Leichhardt Highway, a highway of Queensland, Australia

* Leichhardt Way, an Australian road route

* Leichhardt, New South Wales, inn ...

, then at 'Auburn Vale', Granville, and later at 'Waverley' on Croyden Street, Petersham. In the 1890s, they lived first at 'Koorinda' on Albert Street, Strathfield

Strathfield is a suburb in the Inner West of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located 12 kilometres west of the Sydney central business district and is the administrative centre of the Municipality of Strathfield. A ...

and later at 'Illyria', on The Boulevard, Strathfield.

Hoskins built 'Illyria' in the early 1890s. With his typical thrift and practicality, the stone facade of this grand building was obtained from the City Bank building in Pitt Street

Pitt Street is a major street in the Sydney central business district in New South Wales, Australia. The street runs through the entire city centre from Circular Quay in the north to Waterloo, although today's street is in two disjointed sec ...

—built in 1873—which had been gutted by a fire in October 1890. The stonework was dismantled and transported in sections to its new site and re-erected in the same orientation as the original bank building, becoming the facade of a more conventional Italianate

The Italianate style was a distinct 19th-century phase in the history of Classical architecture. Like Palladianism and Neoclassicism, the Italianate style drew its inspiration from the models and architectural vocabulary of 16th-century Italian R ...

mansion.

It was at 'Illyria' that Charles was able to indulge his passion for motor cars, buying the second Ford car imported to Australia, in 1904, and a succession of other cars, including a 1908 Clément-Talbot

Clément-Talbot Limited was a British motor vehicle manufacturer with its works in Ladbroke Grove, North Kensington, London, founded in 1903. The new business's capital was arranged by Charles Chetwynd-Talbot (whose family name became the brand- ...

. His three sons shared a 'Star' 7 h.p. car; all were driving well before drivers' licences were introduced in N.S.W. in 1910. The garage suite, at the rear of the house, was probably built during Hoskins' time to house his vehicles, making it one of the earliest private garages in Sydney.

Hoskins' sons attended local schools including Burwood Public School, Homebush Grammar School at Strathfield, and the boys briefly boarded at Kings College in Goulburn, while their parents went to Perth in relation to Goldfields Pipeline

The Goldfields Water Supply Scheme is a pipeline and dam project that delivers potable water from Mundaring Weir in Perth to communities in Western Australia's Eastern Goldfields, particularly Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie. The project was comm ...

. In 1903 Guildford, Cecil and Sid all commenced as day students at Newington College

, motto_translation = To Faith Add Knowledge

, location = Inner West and Lower North Shore of Sydney, New South Wales

, country = Australia

, coordinates =

, pushpin_map = A ...

. The older boys had left school by 1906 but Sid remained at Newington until 1907. The older Hoskins boys were not notable students, although Sid is recorded in the school magazine, ''The Newingtonian'', as winning the Preparatory School French prize in 1904 and the Upper Modern Form English prize in 1907. ‘The Hoskins Saga’ records that when the Hoskins family moved to Lithgow in 1908 Sid was sent to the neighbouring school Cooerwull Academy

The Cooerwull Academy was an independent, Presbyterian, day and boarding school for boys, located in Bowenfels, a small town on the western outskirts of Lithgow, New South Wales, Australia.

Cooerwull was founded in 1882Presbyterian Ladies College at Croydon, and it is probable that her sisters also attended the school.

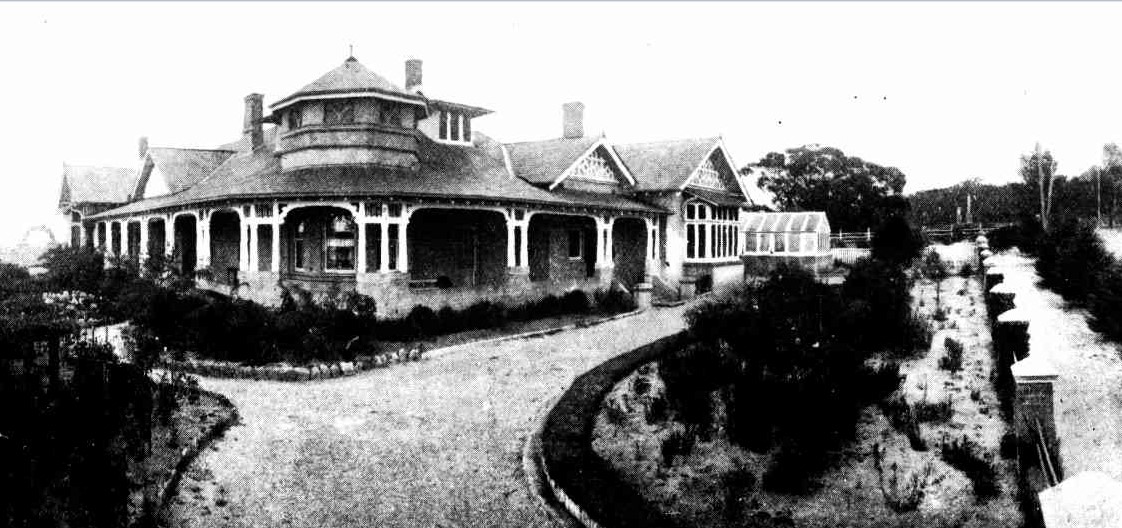

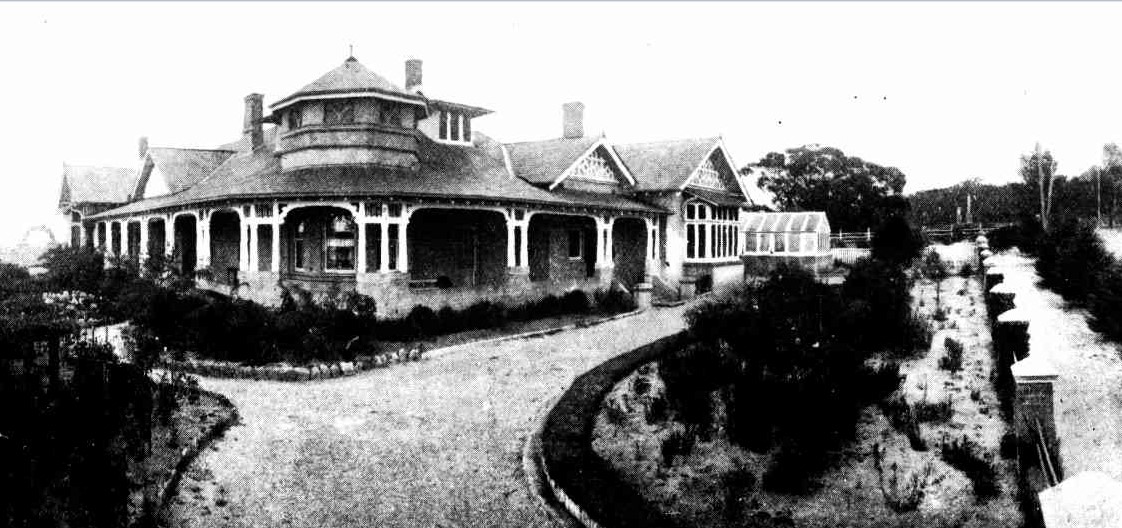

In 1907, his eldest daughter, Florence, and her new husband were living at 'Mevaina', on  The family's home 'Cadia Park', on five acres of land, at Bullaburra, lay close to the boundary of that mountain settlement with Lawson and was completed in 1914. It had eight bedrooms, billiard-room, drawing and dining rooms, three bathrooms, entrance hall, maids' dining room and larder, and kitchen. Separate out-buildings include stables, a garage accommodating six cars, and laundry. The house was situated so as to have magnificent views over the adjacent valley. Outdoors, 'Cadia Park' had grassed tennis courts, shrubberies, two large swimming baths, one for adults and one for children, and extensive gardens. Hoskins also leased some crown land nearby for use as a private zoo to which he allowed public admission. The Hoskins made 'Cadia Park' their home, until 1922. Charles sold the property in 1923, with the land-holding totalling 42 acres.

Charles Hoskins moved, in 1922, to what would be his last home, Ashton in Elizabeth Bay.

The family's home 'Cadia Park', on five acres of land, at Bullaburra, lay close to the boundary of that mountain settlement with Lawson and was completed in 1914. It had eight bedrooms, billiard-room, drawing and dining rooms, three bathrooms, entrance hall, maids' dining room and larder, and kitchen. Separate out-buildings include stables, a garage accommodating six cars, and laundry. The house was situated so as to have magnificent views over the adjacent valley. Outdoors, 'Cadia Park' had grassed tennis courts, shrubberies, two large swimming baths, one for adults and one for children, and extensive gardens. Hoskins also leased some crown land nearby for use as a private zoo to which he allowed public admission. The Hoskins made 'Cadia Park' their home, until 1922. Charles sold the property in 1923, with the land-holding totalling 42 acres.

Charles Hoskins moved, in 1922, to what would be his last home, Ashton in Elizabeth Bay.

Hoskins Iron and Steel Limited become a part of Australian Iron and Steel Limited, a new company—also part owned by

Hoskins Iron and Steel Limited become a part of Australian Iron and Steel Limited, a new company—also part owned by  The Hoskins Memorial Presbyterian Church in Lithgow was intended as a memorial to his son Henry Guildford Hoskins and also to commemorate his daughters Hilda and Nellie but it also commemorates Charles, his wife Emily, and two of his grandsons, all of whom died before its opening. Standing on an opposite corner of the intersection of Mort and Bridge Streets from the church, the Charles Hoskins Memorial Institute building—opened in 1927—is now a campus of the

The Hoskins Memorial Presbyterian Church in Lithgow was intended as a memorial to his son Henry Guildford Hoskins and also to commemorate his daughters Hilda and Nellie but it also commemorates Charles, his wife Emily, and two of his grandsons, all of whom died before its opening. Standing on an opposite corner of the intersection of Mort and Bridge Streets from the church, the Charles Hoskins Memorial Institute building—opened in 1927—is now a campus of the

Charles Henry Hoskins - Australian Dictionary of Biography

Hoskins Memorial Church Lithgow

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hoskins, Charles 1851 births 1926 deaths Australian ironmasters 19th-century Australian businesspeople 20th-century Australian businesspeople Lithgow, New South Wales Australian manufacturing businesspeople

Appian Way

The Appian Way (Latin and Italian language, Italian: ''Via Appia'') is one of the earliest and strategically most important Roman roads of the ancient Roman Republic, republic. It connected Rome to Brindisi, in southeast Italy. Its importance is ...

, Burwood, in an exclusive ' garden city' influenced residential precinct—known as the 'Hoskins Estate'—founded in 1903 by Charles Hoskins' brother, George, who lived at nearby ' St Cloud'.

After the takeover of the Lithgow works, in early 1908, Charles and his family moved from Strathfield to Marrangaroo, west of Bowenfels and Lithgow, living in William Sandford's former home, 'Eskroy Park', which was situated on 2000 acres of land. They also spent time at Lawson in the Blue Mountains, having an association with the area that went back well before their move to Lithgow. Later, they were to make their home in the area and contribute to the beautification of its parks and gardens.

Charles and Emily lost three of their children, within the space of four years. In 1912, his daughter Hilda drove her car onto the level crossing at 'Eskroy Park' where it was struck by a locomotive. Although she was taken to the house, she died without regaining consciousness. In 1914, his daughter, Nellie, was living at 'Narbothong', 24 Badgerys Crescent, Lawson—probably the Hoskins' mountain holiday home—where stricken with tuberculosis, she died, before the family's new home nearby—built with her recovery in mind—could be completed. Their eldest son, Henry Guildford Hoskins (known as Guildford) was fatally injured in an acetylene gas explosion, in 1916, while repairing a gas generator, at 'Eskroy Park'. Although moved to a hospital in Sydney, he died. He was 28 when he died and already a significant figure in the company. Guildford left a widow Jeannie (née Mathieson), an infant daughter, Lynette, and a posthumously-born son, also Henry Guildford.

The family's home 'Cadia Park', on five acres of land, at Bullaburra, lay close to the boundary of that mountain settlement with Lawson and was completed in 1914. It had eight bedrooms, billiard-room, drawing and dining rooms, three bathrooms, entrance hall, maids' dining room and larder, and kitchen. Separate out-buildings include stables, a garage accommodating six cars, and laundry. The house was situated so as to have magnificent views over the adjacent valley. Outdoors, 'Cadia Park' had grassed tennis courts, shrubberies, two large swimming baths, one for adults and one for children, and extensive gardens. Hoskins also leased some crown land nearby for use as a private zoo to which he allowed public admission. The Hoskins made 'Cadia Park' their home, until 1922. Charles sold the property in 1923, with the land-holding totalling 42 acres.

Charles Hoskins moved, in 1922, to what would be his last home, Ashton in Elizabeth Bay.

The family's home 'Cadia Park', on five acres of land, at Bullaburra, lay close to the boundary of that mountain settlement with Lawson and was completed in 1914. It had eight bedrooms, billiard-room, drawing and dining rooms, three bathrooms, entrance hall, maids' dining room and larder, and kitchen. Separate out-buildings include stables, a garage accommodating six cars, and laundry. The house was situated so as to have magnificent views over the adjacent valley. Outdoors, 'Cadia Park' had grassed tennis courts, shrubberies, two large swimming baths, one for adults and one for children, and extensive gardens. Hoskins also leased some crown land nearby for use as a private zoo to which he allowed public admission. The Hoskins made 'Cadia Park' their home, until 1922. Charles sold the property in 1923, with the land-holding totalling 42 acres.

Charles Hoskins moved, in 1922, to what would be his last home, Ashton in Elizabeth Bay.

Later life and death

After he stepped down as Managing Director of Hoskins Iron and Steel, in 1924, Charles Hoskins had only a short retirement; he was in poor health during that time. He died at his home on 14 February 1926, not living to see the fulfillment of his plans for Port Kembla. He was survived by his wife, Emily, two sons, three daughters and twenty-two grandchildren. He left a relatively small personal legacy of £12,018. His fortune of well in excess of £1,000,000 had been distributed among his large family, by means of a family company C.H. Hoskins Co. Limited, set up in 1904. The family company also owned the Kembla Building, in Sydney, a 12-storey office building completed in late 1924. Charles Hoskins' fortune had been made in his own lifetime, starting from nothing at age thirteen. He had been very much a self-made man. His widow Emily died in November 1928, having lived just long enough to light the new blast furnace at Port Kembla in August of the same year. Charles Hoskins' grave lies in the Congregational section of theRookwood Cemetery

Rookwood Cemetery (officially named Rookwood Necropolis) is a heritage-listed cemetery in Rookwood, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It is the largest List of necropolises, necropolis in the Southern Hemisphere and is the world's largest ...

; nearby are the graves of his wife and his children, Florence, Hilda, Nellie and Henry.

Legacy

Hoskins' greatest achievement was to save and expand the Lithgow steelworks, especially during the years from 1911 to 1913. During that time, he had to rectify and expand an inadequate loss-making plant, while in conflict, simultaneously, with some of his workforce and with his largest customer, the N.S.W Government, and under the scrutiny of a Royal Commission. However, his most lasting legacy is the large steelworks at Port Kembla. Although he did not live to see it, his vision and foresight had led to its creation. For many decades, it was known as 'Hoskins Kembla Works'; now, no longer known by that name, it is still the site of most of Australia's steel production. Between 1928 and early 1932, some parts of the old Lithgow works were re-erected at Port Kembla but other parts, including the two Lithgow blast furnaces, made the journey to Port Kembla only as scrap iron to be fed into the furnaces of the younger plant. In December 1931, the last steel was rolled at Lithgow. Only very little remains of the Lithgow works today, in what is now the Blast Furnace Park. 'Wallaby

A wallaby () is a small or middle-sized Macropodidae, macropod native to Australia and New Guinea, with introduced populations in New Zealand, Hawaii, the United Kingdom and other countries. They belong to the same Taxonomy (biology), taxon ...

', a locomotive from the Lithgow steelworks, survives. From 1913, 'Wallaby' worked the then new line to Hoskins' two Lithgow blast furnaces and after that was at Port Kembla until 1963.

Hoskins Iron and Steel Limited become a part of Australian Iron and Steel Limited, a new company—also part owned by

Hoskins Iron and Steel Limited become a part of Australian Iron and Steel Limited, a new company—also part owned by Dorman Long

Dorman Long & Co was a UK steel producer, later diversifying into bridge building. It was once listed on the London Stock Exchange.

History

The company was founded by Arthur Dorman and Albert de Lande Long when they acquired ''West Marsh ...

, Howard Smith Limited

Howard Smith Limited was an Australian industrial company. Founded in 1854 as a shipping company, it later diversified into coal mining, steel production, stevedoring, travel, railway rolling stock building, sugar production and retail. Its divi ...

, Baldwins and preference shareholders—that was set up in March 1928 to build and operate the new plant at Port Kembla and its associated iron ore, limestone and coal mines. In 1935, a victim of the Great Depression and other difficulties, this company became, via an exchange of ordinary shares

Common stock is a form of corporate equity ownership, a type of security. The terms voting share and ordinary share are also used frequently outside of the United States. They are known as equity shares or ordinary shares in the UK and other Comm ...

, a subsidiary of BHP

BHP Group Limited (formerly known as BHP Billiton) is an Australian multinational mining, metals, natural gas petroleum public company that is headquartered in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

The Broken Hill Proprietary Company was founded ...

. Preference shares of Australian Iron and Steel Limited remained trading on the stock exchange, until 1959 when BHP's offer was accepted and the AIS preference shares were converted to ordinary BHP shares.

Charles Hoskins' sons Cecil and Sidney Hoskins remained managers at Port Kembla and directors of Australian Iron and Steel Ltd. The Hoskins family were major shareholders of BHP. Under BHP ownership, the plant was greatly expanded, and outlived the Newcastle works. Following the demerger of BHP's steel interests from the rest of the company, it is now owned by Bluescope Steel

BlueScope Steel Limited is an Australian flat product steel producer that was spun-off from BHP Billiton in 2002.

History

BlueScope was formed when BHP Billiton spun-off its steel assets on 15 July 2002 as BHP Steel. It was renamed BlueScope ...

. The Hoskins Memorial Presbyterian Church in Lithgow was intended as a memorial to his son Henry Guildford Hoskins and also to commemorate his daughters Hilda and Nellie but it also commemorates Charles, his wife Emily, and two of his grandsons, all of whom died before its opening. Standing on an opposite corner of the intersection of Mort and Bridge Streets from the church, the Charles Hoskins Memorial Institute building—opened in 1927—is now a campus of the

The Hoskins Memorial Presbyterian Church in Lithgow was intended as a memorial to his son Henry Guildford Hoskins and also to commemorate his daughters Hilda and Nellie but it also commemorates Charles, his wife Emily, and two of his grandsons, all of whom died before its opening. Standing on an opposite corner of the intersection of Mort and Bridge Streets from the church, the Charles Hoskins Memorial Institute building—opened in 1927—is now a campus of the Western Sydney University

Western Sydney University, formerly the University of Western Sydney, is an Australian multi-campus university in the Greater Western region of Sydney, Australia. The university in its current form was founded in 1989 as a federated network ...

.

Charles Hoskins had initiated the Hoskins Trust, in 1919, for charitable purposes, endowing a fund to support the Hoskins Memorial Church. Since 2006, this trust has awarded an annual scholarship, the Hoskins Lithgow Scholarship, for a Lithgow resident to study at a university or other tertiary education

Tertiary education, also referred to as third-level, third-stage or post-secondary education, is the educational level following the completion of secondary education. The World Bank, for example, defines tertiary education as including univers ...

institution.

Although Hoskins and his family endowed Lithgow with fine buildings, their longer-term legacy there is mixed. The stark and desolate ruin of the blast furnace's blower house stands as a reminder that the closure of the town's main industry—at the height of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

—and the exodus of skilled managers and workers to Port Kembla—with their families, about 5000 people—was a blow from which the future prospects of the town never recovered. In 1929, Lithgow had the fourth largest urban population in New South Wales—after Sydney, Newcastle, and Broken Hill—but by 2016, it was 36th; Lithgow's population fell from around 18,000, in 1929, to only 11,530 in 2016. At the 2021 census, the population had fallen slightly.

A former garden at Lawson, 'Hilda Gardens', was funded by Hoskins and dedicated to the memory of his daughter, Hilda. He paid £50 annually for its upkeep during his lifetime. It survived the 1930s, at least, in more or less original condition, after which modifications were made to the bowling green. Sadly, this garden has been completely subsumed by the growth of the Lawson Bowling Club and no trace of it remains. Not far from where the gardens once were, the house, 'Narbethong', still stands in Badgerys Cresent.