Catherine II of Russia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father =

(now Szczecin, Poland) , death_date = (aged 67) , death_place =

Catherine was born in

Catherine was born in

The choice of Princess Sophie as wife of the future tsar was one result of the

The choice of Princess Sophie as wife of the future tsar was one result of the  After the death of the Empress Elizabeth on 5 January 1762 ( OS: 25 December 1761), Peter succeeded to the throne as Emperor Peter III, and Catherine became empress consort. The imperial couple moved into the new

After the death of the Empress Elizabeth on 5 January 1762 ( OS: 25 December 1761), Peter succeeded to the throne as Emperor Peter III, and Catherine became empress consort. The imperial couple moved into the new

During her reign, Catherine extended the borders of the

During her reign, Catherine extended the borders of the  Catherine's foreign minister,

Catherine's foreign minister,

Catherine longed for recognition as an enlightened sovereign. She refused the Duchy of Holstein-Gottorp which had ports on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean, and refrained from having a Russian army in Germany. Instead she pioneered for Russia the role that Britain later played through most of the 19th and early 20th centuries as an international mediator in disputes that could, or did, lead to war. She acted as mediator in the

Catherine longed for recognition as an enlightened sovereign. She refused the Duchy of Holstein-Gottorp which had ports on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean, and refrained from having a Russian army in Germany. Instead she pioneered for Russia the role that Britain later played through most of the 19th and early 20th centuries as an international mediator in disputes that could, or did, lead to war. She acted as mediator in the

In 1764, Catherine placed Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, her former lover, on the

In 1764, Catherine placed Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, her former lover, on the

Russian economic development was well below the standards in western Europe. Historian François Cruzet writes that Russia under Catherine:

Catherine imposed a comprehensive system of state regulation of merchants' activities. It was a failure because it narrowed and stifled entrepreneurship and did not reward economic development. She had more success when she strongly encouraged the migration of the

Russian economic development was well below the standards in western Europe. Historian François Cruzet writes that Russia under Catherine:

Catherine imposed a comprehensive system of state regulation of merchants' activities. It was a failure because it narrowed and stifled entrepreneurship and did not reward economic development. She had more success when she strongly encouraged the migration of the

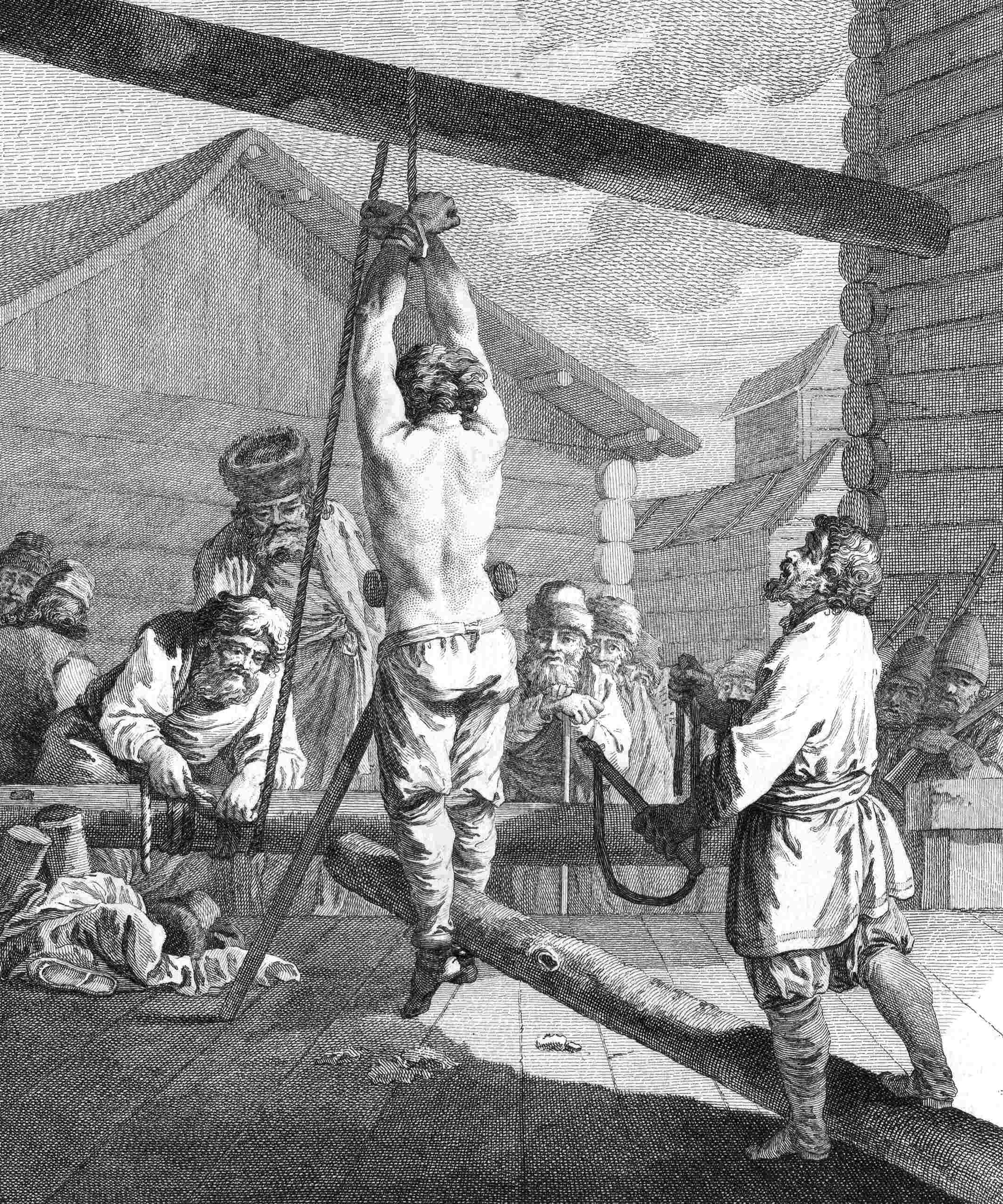

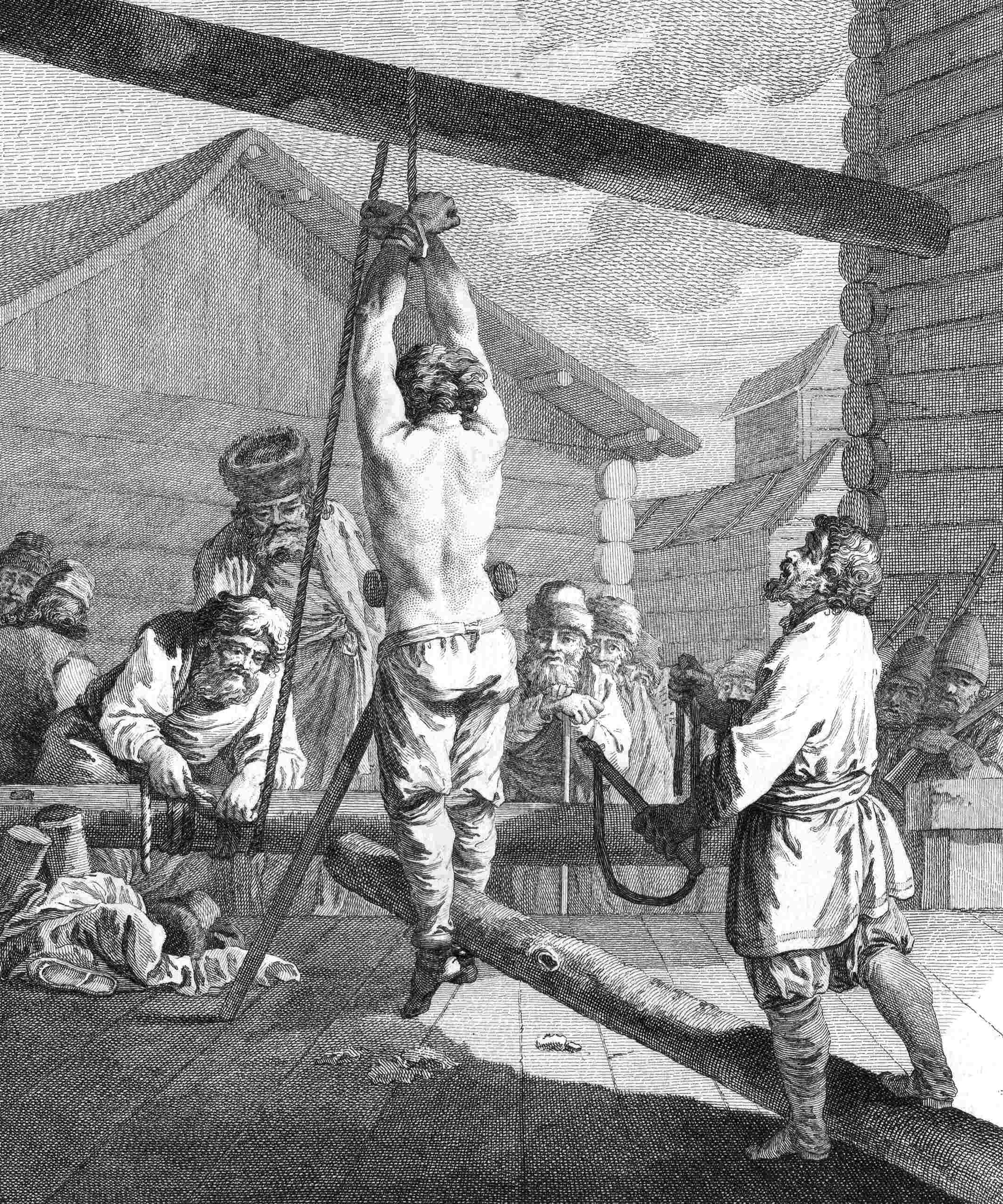

At the time of Catherine's reign, the landowning noble class owned the serfs, who were bound to the land they tilled. Children of serfs were born into serfdom and worked the same land their parents had. Even before the rule of Catherine, serfs had very limited rights, but they were not exactly slaves. While the state did not technically allow them to own possessions, some serfs were able to accumulate enough wealth to pay for their freedom. The understanding of law in

At the time of Catherine's reign, the landowning noble class owned the serfs, who were bound to the land they tilled. Children of serfs were born into serfdom and worked the same land their parents had. Even before the rule of Catherine, serfs had very limited rights, but they were not exactly slaves. While the state did not technically allow them to own possessions, some serfs were able to accumulate enough wealth to pay for their freedom. The understanding of law in

The attitude of the serfs toward their autocrat had historically been a positive one.

However, if the empress' policies were too extreme or too disliked, she was not considered the true empress. In these cases, it was necessary to replace this "fake" empress with the "true" empress, whoever she may be. Because the serfs had no political power, they rioted to convey their message. However, usually, if the serfs did not like the policies of the empress, they saw the nobles as corrupt and evil, preventing the people of Russia from communicating with the well-intentioned empress and misinterpreting her decrees. However, they were already suspicious of Catherine upon her accession because she had annulled an act by Peter III that essentially freed the serfs belonging to the Orthodox Church. Naturally, the serfs did not like it when Catherine tried to take away their right to petition her because they felt as though she had severed their connection to the autocrat, and their power to appeal to her. Far away from the capital, they were confused as to the circumstances of her accession to the throne.

The peasants were discontented because of many other factors as well, including crop failure, and epidemics, especially a major epidemic in 1771. The nobles were imposing a stricter rule than ever, reducing the land of each serf and restricting their freedoms further beginning around 1767. Their discontent led to widespread outbreaks of violence and rioting during

The attitude of the serfs toward their autocrat had historically been a positive one.

However, if the empress' policies were too extreme or too disliked, she was not considered the true empress. In these cases, it was necessary to replace this "fake" empress with the "true" empress, whoever she may be. Because the serfs had no political power, they rioted to convey their message. However, usually, if the serfs did not like the policies of the empress, they saw the nobles as corrupt and evil, preventing the people of Russia from communicating with the well-intentioned empress and misinterpreting her decrees. However, they were already suspicious of Catherine upon her accession because she had annulled an act by Peter III that essentially freed the serfs belonging to the Orthodox Church. Naturally, the serfs did not like it when Catherine tried to take away their right to petition her because they felt as though she had severed their connection to the autocrat, and their power to appeal to her. Far away from the capital, they were confused as to the circumstances of her accession to the throne.

The peasants were discontented because of many other factors as well, including crop failure, and epidemics, especially a major epidemic in 1771. The nobles were imposing a stricter rule than ever, reducing the land of each serf and restricting their freedoms further beginning around 1767. Their discontent led to widespread outbreaks of violence and rioting during

Catherine shared in the general European craze for all things Chinese, and made a point of collecting Chinese art and buying porcelain in the popular ''

Catherine shared in the general European craze for all things Chinese, and made a point of collecting Chinese art and buying porcelain in the popular '' Catherine read three sorts of books, namely those for pleasure, those for information, and those to provide her with a philosophy. In the first category, she read romances and comedies that were popular at the time, many of which were regarded as "inconsequential" by the critics both then and since. She especially liked the work of German comic writers such as Moritz August von Thümmel and

Catherine read three sorts of books, namely those for pleasure, those for information, and those to provide her with a philosophy. In the first category, she read romances and comedies that were popular at the time, many of which were regarded as "inconsequential" by the critics both then and since. She especially liked the work of German comic writers such as Moritz August von Thümmel and  As many of the democratic principles frightened her more moderate and experienced advisors, she refrained from immediately putting them into practice. After holding more than 200 sittings, the so-called Commission dissolved without getting beyond the realm of theory.

Catherine began issuing codes to address some of the modernisation trends suggested in her Nakaz. In 1775, the empress decreed a Statute for the Administration of the Provinces of the Russian Empire. The statute sought to efficiently govern Russia by increasing population and dividing the country into provinces and districts. By the end of her reign, 50 provinces and nearly 500 districts were created, government officials numbering more than double this were appointed, and spending on local government increased sixfold. In 1785, Catherine conferred on the nobility the Charter to the Nobility, increasing the power of the landed oligarchs. Nobles in each district elected a Marshal of the Nobility, who spoke on their behalf to the monarch on issues of concern to them, mainly economic ones. In the same year, Catherine issued the Charter of the Towns, which distributed all people into six groups as a way to limit the power of nobles and create a middle estate. Catherine also issued the Code of Commercial Navigation and Salt Trade Code of 1781, the Police Ordinance of 1782, and the Statute of National Education of 1786. In 1777, the empress described to Voltaire her legal innovations within a backward Russia as progressing "little by little".

As many of the democratic principles frightened her more moderate and experienced advisors, she refrained from immediately putting them into practice. After holding more than 200 sittings, the so-called Commission dissolved without getting beyond the realm of theory.

Catherine began issuing codes to address some of the modernisation trends suggested in her Nakaz. In 1775, the empress decreed a Statute for the Administration of the Provinces of the Russian Empire. The statute sought to efficiently govern Russia by increasing population and dividing the country into provinces and districts. By the end of her reign, 50 provinces and nearly 500 districts were created, government officials numbering more than double this were appointed, and spending on local government increased sixfold. In 1785, Catherine conferred on the nobility the Charter to the Nobility, increasing the power of the landed oligarchs. Nobles in each district elected a Marshal of the Nobility, who spoke on their behalf to the monarch on issues of concern to them, mainly economic ones. In the same year, Catherine issued the Charter of the Towns, which distributed all people into six groups as a way to limit the power of nobles and create a middle estate. Catherine also issued the Code of Commercial Navigation and Salt Trade Code of 1781, the Police Ordinance of 1782, and the Statute of National Education of 1786. In 1777, the empress described to Voltaire her legal innovations within a backward Russia as progressing "little by little".

During Catherine's reign, Russians imported and studied the classical and European influences that inspired the

During Catherine's reign, Russians imported and studied the classical and European influences that inspired the

Catherine held western European philosophies and culture close to her heart, and she wanted to surround herself with like-minded people within Russia. She believed a 'new kind of person' could be created by inculcating Russian children with European education. Catherine believed education could change the hearts and minds of the Russian people and turn them away from backwardness. This meant developing individuals both intellectually and morally, providing them knowledge and skills, and fostering a sense of civic responsibility. Her goal was to modernise education across Russia.

Catherine held western European philosophies and culture close to her heart, and she wanted to surround herself with like-minded people within Russia. She believed a 'new kind of person' could be created by inculcating Russian children with European education. Catherine believed education could change the hearts and minds of the Russian people and turn them away from backwardness. This meant developing individuals both intellectually and morally, providing them knowledge and skills, and fostering a sense of civic responsibility. Her goal was to modernise education across Russia.

Catherine appointed

Catherine appointed

Not long after the Moscow Foundling Home, at the instigation of her factotum, Ivan Betskoy, she wrote a manual for the education of young children, drawing from the ideas of

Not long after the Moscow Foundling Home, at the instigation of her factotum, Ivan Betskoy, she wrote a manual for the education of young children, drawing from the ideas of

Catherine's apparent embrace of all things Russian (including Orthodoxy) may have prompted her personal indifference to religion. She nationalised all of the church lands to help pay for her wars, largely emptied the monasteries, and forced most of the remaining clergymen to survive as farmers or from fees for baptisms and other services. Very few members of the nobility entered the church, which became even less important than it had been. She did not allow dissenters to build chapels, and she suppressed religious dissent after the onset of the French Revolution.

However, in accord with her anti-Ottoman policy, Catherine promoted the protection and fostering of Christians under Turkish rule. She placed strictures on Catholics (''

Catherine's apparent embrace of all things Russian (including Orthodoxy) may have prompted her personal indifference to religion. She nationalised all of the church lands to help pay for her wars, largely emptied the monasteries, and forced most of the remaining clergymen to survive as farmers or from fees for baptisms and other services. Very few members of the nobility entered the church, which became even less important than it had been. She did not allow dissenters to build chapels, and she suppressed religious dissent after the onset of the French Revolution.

However, in accord with her anti-Ottoman policy, Catherine promoted the protection and fostering of Christians under Turkish rule. She placed strictures on Catholics (''

Catherine took many different approaches to Islam during her reign. She avoided force and tried persuasion (and money) to integrate Muslim areas into her empire. Between 1762 and 1773, Muslims were prohibited from owning any Orthodox serfs. They were pressured into Orthodoxy through monetary incentives. Catherine promised more serfs of all religions, as well as amnesty for convicts, if Muslims chose to convert to Orthodoxy. However, the Legislative Commission of 1767 offered several seats to people professing the Islamic faith. This commission promised to protect their religious rights, but did not do so. Many Orthodox peasants felt threatened by the sudden change, and burned mosques as a sign of their displeasure. Catherine chose to assimilate Islam into the state rather than eliminate it when public outcry became too disruptive. After the "Toleration of All Faiths" Edict of 1773, Muslims were permitted to build

Catherine took many different approaches to Islam during her reign. She avoided force and tried persuasion (and money) to integrate Muslim areas into her empire. Between 1762 and 1773, Muslims were prohibited from owning any Orthodox serfs. They were pressured into Orthodoxy through monetary incentives. Catherine promised more serfs of all religions, as well as amnesty for convicts, if Muslims chose to convert to Orthodoxy. However, the Legislative Commission of 1767 offered several seats to people professing the Islamic faith. This commission promised to protect their religious rights, but did not do so. Many Orthodox peasants felt threatened by the sudden change, and burned mosques as a sign of their displeasure. Catherine chose to assimilate Islam into the state rather than eliminate it when public outcry became too disruptive. After the "Toleration of All Faiths" Edict of 1773, Muslims were permitted to build  In 1785, Catherine approved the subsidising of new mosques and new town settlements for Muslims. This was another attempt to organise and passively control the outer fringes of her country. By building new settlements with mosques placed in them, Catherine attempted to ground many of the nomadic people who wandered through southern Russia. In 1786, she assimilated the Islamic schools into the Russian public school system under government regulation. The plan was another attempt to force nomadic people to settle. This allowed the Russian government to control more people, especially those who previously had not fallen under the jurisdiction of Russian law.

In 1785, Catherine approved the subsidising of new mosques and new town settlements for Muslims. This was another attempt to organise and passively control the outer fringes of her country. By building new settlements with mosques placed in them, Catherine attempted to ground many of the nomadic people who wandered through southern Russia. In 1786, she assimilated the Islamic schools into the Russian public school system under government regulation. The plan was another attempt to force nomadic people to settle. This allowed the Russian government to control more people, especially those who previously had not fallen under the jurisdiction of Russian law.

In many ways, the Orthodox Church fared no better than its foreign counterparts during the reign of Catherine. Under her leadership, she completed what Peter III had started. The church's lands were expropriated, and the budget of both monasteries and bishoprics were controlled by the Collegium of Accounting. Endowments from the government replaced income from privately held lands. The endowments were often much less than the original intended amount. She closed 569 of 954 monasteries, of which only 161 received government money. Only 400,000 rubles of church wealth were paid back. While other religions (such as Islam) received invitations to the Legislative Commission, the Orthodox clergy did not receive a single seat. Their place in government was restricted severely during the years of Catherine's reign.

In 1762, to help mend the rift between the Orthodox church and a sect that called themselves the Old Believers, Catherine passed an act that allowed Old Believers to practise their faith openly without interference. While claiming religious tolerance, she intended to recall the Old Believers into the official church. They refused to comply, and in 1764, she deported over 20,000 Old Believers to Siberia on the grounds of their faith. In later years, Catherine amended her thoughts. Old Believers were allowed to hold elected municipal positions after the Urban Charter of 1785, and she promised religious freedom to those who wished to settle in Russia.

Religious education was reviewed strictly. At first, she attempted to revise clerical studies, proposing a reform of religious schools. This reform never progressed beyond the planning stages. By 1786, Catherine excluded all religion and clerical studies programs from lay education. By separating the public interests from those of the church, Catherine began a secularisation of the day-to-day workings of Russia. She transformed the clergy from a group that wielded great power over the Russian government and its people to a segregated community forced to depend on the state for compensation.

In many ways, the Orthodox Church fared no better than its foreign counterparts during the reign of Catherine. Under her leadership, she completed what Peter III had started. The church's lands were expropriated, and the budget of both monasteries and bishoprics were controlled by the Collegium of Accounting. Endowments from the government replaced income from privately held lands. The endowments were often much less than the original intended amount. She closed 569 of 954 monasteries, of which only 161 received government money. Only 400,000 rubles of church wealth were paid back. While other religions (such as Islam) received invitations to the Legislative Commission, the Orthodox clergy did not receive a single seat. Their place in government was restricted severely during the years of Catherine's reign.

In 1762, to help mend the rift between the Orthodox church and a sect that called themselves the Old Believers, Catherine passed an act that allowed Old Believers to practise their faith openly without interference. While claiming religious tolerance, she intended to recall the Old Believers into the official church. They refused to comply, and in 1764, she deported over 20,000 Old Believers to Siberia on the grounds of their faith. In later years, Catherine amended her thoughts. Old Believers were allowed to hold elected municipal positions after the Urban Charter of 1785, and she promised religious freedom to those who wished to settle in Russia.

Religious education was reviewed strictly. At first, she attempted to revise clerical studies, proposing a reform of religious schools. This reform never progressed beyond the planning stages. By 1786, Catherine excluded all religion and clerical studies programs from lay education. By separating the public interests from those of the church, Catherine began a secularisation of the day-to-day workings of Russia. She transformed the clergy from a group that wielded great power over the Russian government and its people to a segregated community forced to depend on the state for compensation.

Catherine, throughout her long reign, took many lovers, often elevating them to high positions for as long as they held her interest and then pensioning them off with gifts of serfs and large estates. The percentage of state money spent on the court increased from 10% in 1767 to 11% in 1781 to 14% in 1795. Catherine gave away 66,000 serfs from 1762 to 1772, 202,000 from 1773 to 1793, and 100,000 in one day: 18 August 1795. Catherine bought the support of the bureaucracy. In 1767, Catherine decreed that after seven years in one rank, civil servants automatically would be promoted regardless of office or merit.

After her affair with her lover and adviser

Catherine, throughout her long reign, took many lovers, often elevating them to high positions for as long as they held her interest and then pensioning them off with gifts of serfs and large estates. The percentage of state money spent on the court increased from 10% in 1767 to 11% in 1781 to 14% in 1795. Catherine gave away 66,000 serfs from 1762 to 1772, 202,000 from 1773 to 1793, and 100,000 in one day: 18 August 1795. Catherine bought the support of the bureaucracy. In 1767, Catherine decreed that after seven years in one rank, civil servants automatically would be promoted regardless of office or merit.

After her affair with her lover and adviser

Later, several rumors circulated regarding the cause and manner of her death. The most famous of these rumors is that she died after having sex with her horse. This rumor was widely circulated by satirical British and French publications at the time of her death. In his 1647 book ''Beschreibung der muscowitischen und persischen Reise'' (''Description of the Muscovite and Persian journey''), German scholar Adam Olearius Olearius's claims about a supposed Russian tendency towards bestiality with horses was often repeated in anti-Russian literature throughout the 17th and 18th centuries to illustrate the alleged barbarous "Asian" nature of Russia. Given the frequency which this story was repeated together with Catherine's love of her adopted homeland and her love of horses, it is likely that these details were conflated into this rumor. Catherine had been targeted for being unmarried.

Catherine's undated will, discovered in early 1792 among her papers by her secretary Alexander Vasilievich Khrapovitsky, gave specific instructions should she die: "Lay out my corpse dressed in white, with a golden crown on my head, and on it inscribe my Christian name. Mourning dress is to be worn for six months, and no longer: the shorter the better." In the end, the empress was laid to rest with a gold crown on her head and clothed in a silver brocade dress. On 25 November, the coffin, richly decorated in gold fabric, was placed atop an elevated platform at the Grand Gallery's chamber of mourning, designed and decorated by Antonio Rinaldi. According to

Later, several rumors circulated regarding the cause and manner of her death. The most famous of these rumors is that she died after having sex with her horse. This rumor was widely circulated by satirical British and French publications at the time of her death. In his 1647 book ''Beschreibung der muscowitischen und persischen Reise'' (''Description of the Muscovite and Persian journey''), German scholar Adam Olearius Olearius's claims about a supposed Russian tendency towards bestiality with horses was often repeated in anti-Russian literature throughout the 17th and 18th centuries to illustrate the alleged barbarous "Asian" nature of Russia. Given the frequency which this story was repeated together with Catherine's love of her adopted homeland and her love of horses, it is likely that these details were conflated into this rumor. Catherine had been targeted for being unmarried.

Catherine's undated will, discovered in early 1792 among her papers by her secretary Alexander Vasilievich Khrapovitsky, gave specific instructions should she die: "Lay out my corpse dressed in white, with a golden crown on my head, and on it inscribe my Christian name. Mourning dress is to be worn for six months, and no longer: the shorter the better." In the end, the empress was laid to rest with a gold crown on her head and clothed in a silver brocade dress. On 25 November, the coffin, richly decorated in gold fabric, was placed atop an elevated platform at the Grand Gallery's chamber of mourning, designed and decorated by Antonio Rinaldi. According to

''La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein'', operetta in 3 acts: Description

Allmusic.com, accessed 13 March 2021. *

''History of Catherine the Great''

Berlin: Publishing Frederick Gottgeyner, 1900. At

''Russian army in the age of the Empress Catherine II''

Saint Petersburg: Printing office of the Department of inheritance, 1873. At Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats * Brickner, Alexander Gustavovich

''History of Catherine the Great''

Saint Petersburg: Typography of A. Suvorin, 1885. At Runivers.ru in DjVu and PDF formats * Catherine the Great. ''The Memoirs of Catherine the Great'' by Markus Cruse and Hilde Hoogenboom (translators). New York: Modern Library, 2005 (hardcover, ); 2006 (paperback, ) * Cronin, Vincent. ''Catherine, Empress of All the Russias''. London: Collins, 1978 (hardcover, ); 1996 (paperback, ) * Dixon, Simon. ''Catherine the Great (Profiles in Power)''. Harlow, UK: Longman, 2001 (paperback, ) * Herman, Eleanor. ''Sex With the Queen''. New York: HarperCollins, 2006 (hardcover, ). * LeDonne, John P. ''Ruling Russia: Politics & Administration in the Age of Absolutism, 1762–1796'' (1984). * Malecka, Anna. "Did Orlov Buy the Orlov", ''Gems and Jewellery'', July 2014, pp. 10–12. * * Nikolaev, Vsevolod, and Albert Parry. ''The Loves of Catherine the Great'' (1982). * Ransel, David L. ''The Politics of Catherinian Russia: The Panin Party'' (Yale UP, 1975). * Sette, Alessandro. "Catherine II and the Socio-Economic Origins of the Jewish Question in Russia", ''Annales Universitatis Apulensis - Series Historica'', 23#2 (2019): 47–63. * Smith, Douglas, ed. and trans. ''Love and Conquest: Personal Correspondence of Catherine the Great and Prince Grigory Potemkin''. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois UP, 2004 (hardcover, ); 2005 (paperback ) * Troyat, Henri. ''Catherine the Great''. New York: Dorset Press, 1991 (hardcover, ); London: Orion, 2000 (paperback, ) popular * Troyat, Henri. ''Terrible Tsarinas''. New York: Algora, 2001 ().

Some of the code of laws mentioned above, along with other information

* * Information about th

* Briefly about Catherine:

at the

Diaries and Letters: Catherine II – German Princess Who Came to Rule Russia

at the

Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst (29 November 1690, in Dornburg – 16 March 1747, in Zerbst) was a German prince of the House of Ascania, and the father of Catherine the Great of Russia.

He was a ruler of the Principality of A ...

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp (24 October 1712 – 30 May 1760) was a member of the German House of Holstein-Gottorp, a princess consort of Anhalt-Zerbst by marriage, and the regent of Anhalt-Zerbst from 1747 to 1752 on behalf of her minor ...

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst

, birth_place = Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin language, Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital city, capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the Po ...

, Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

(now Szczecin, Poland) , death_date = (aged 67) , death_place =

Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Emperor of all the Russias, Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The p ...

, Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, burial_date =

, burial_place = Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg

The Peter and Paul Cathedral (russian: Петропавловский собор) is a Russian Orthodox cathedral located inside the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg, Russia. It is the first and oldest landmark in St. Petersburg, built b ...

, signature = Catherine The Great Signature.svg

, religion =

Catherine II (born Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia

The emperor or empress of all the Russias or All Russia, ''Imperator Vserossiyskiy'', ''Imperatritsa Vserossiyskaya'' (often titled Tsar or Tsarina/Tsaritsa) was the monarch of the Russian Empire.

The title originated in connection with Russia' ...

from 1762 to 1796. She came to power following the overthrow of her husband, Peter III. Under her long reign, inspired by the ideas of the Enlightenment, Russia experienced a renaissance of culture and sciences, which led to the founding of many new cities, universities, and theaters; along with large-scale immigration from the rest of Europe, and the recognition of Russia as one of the great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

s of Europe.

In her accession to power and her rule of the empire, Catherine often relied on her noble favourites, most notably Count Grigory Orlov

Prince Grigory Grigoryevich Orlov (russian: Князь Григорий Григорьевич Орлов; 6 October 1734, Bezhetsky Uyezd – 13 April 1783, Moscow) was a favourite of the Empress Catherine the Great of Russia. He became a leader ...

and Grigory Potemkin

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin-Tauricheski (, also , ;, rus, Князь Григо́рий Алекса́ндрович Потёмкин-Таври́ческий, Knjaz' Grigórij Aleksándrovich Potjómkin-Tavrícheskij, ɡrʲɪˈɡ ...

. Assisted by highly successful generals

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED O ...

such as Alexander Suvorov

Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov (russian: Алекса́ндр Васи́льевич Суво́ров, Aleksándr Vasíl'yevich Suvórov; or 1730) was a Russian general in service of the Russian Empire. He was Count of Rymnik, Count of the Holy ...

and Pyotr Rumyantsev

Count Pyotr Alexandrovich Rumyantsev-Zadunaisky (russian: Пётр Алекса́ндрович Румя́нцев-Задунайский; – ) was one of the foremost Russian generals of the 18th century. He governed Little Russia in the na ...

, and admirals such as Samuel Greig

Vice-Admiral Samuel Greig, or Samuil Karlovich Greig (russian: Самуи́л Ка́рлович Грейг), as he was known in Russia (30 November 1735, Inverkeithing, Fife, Scotland – 26 October 1788, Tallinn, Governorate of Estonia, Esto ...

and Fyodor Ushakov

Fyodor Fyodorovich Ushakov ( rus, Фёдор Фёдорович Ушако́в, p=ʊʂɐˈkof; – ) was an 18th century Russian naval commander and admiral. He is notable for winning every engagement he participated in as the Admiral of t ...

, she governed at a time when the Russian Empire was expanding rapidly by conquest and diplomacy. In the south, the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate ( crh, , or ), officially the Great Horde and Desht-i Kipchak () and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary ( la, Tartaria Minor), was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to ...

was crushed following victories over the Bar Confederation and Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histo ...

. With the support of Great Britain, Russia colonised the territories of Novorossiya

Novorossiya, literally "New Russia", is a historical name, used during the era of the Russian Empire for an administrative area that would later become the southern mainland of Ukraine: the region immediately north of the Black Sea and Crimea. ...

along the coasts of the Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ...

and Azov Seas. In the west, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

, ruled by Catherine's former lover King Stanisław August Poniatowski

Stanisław II August (born Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski; 17 January 1732 – 12 February 1798), known also by his regnal Latin name Stanislaus II Augustus, was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1764 to 1795, and the last monarch ...

, was eventually partitioned, with the Russian Empire gaining the largest share. In the east, Russians became the first Europeans to colonise Alaska, establishing Russian America

Russian America (russian: Русская Америка, Russkaya Amerika) was the name for the Russian Empire's colonial possessions in North America from 1799 to 1867. It consisted mostly of present-day Alaska in the United States, but a ...

.

Many cities and towns were founded on Catherine's orders in the newly conquered lands, most notably Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, Dnipro (then known as Yekaterinoslav), Kherson

Kherson (, ) is a port city of Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers appr ...

, Mykolaiv

Mykolaiv ( uk, Миколаїв, ) is a city and municipality in Southern Ukraine, the administrative center of the Mykolaiv Oblast. Mykolaiv city, which provides Ukraine with access to the Black Sea, is the location of the most downriver brid ...

and Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

. An admirer of Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

, Catherine continued to modernise Russia along Western European lines. However, military conscription and the economy continued to depend on serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

, and the increasing demands of the state and of private landowners intensified the exploitation of serf labour. This was one of the chief reasons behind rebellions, including Pugachev's Rebellion

Pugachev's Rebellion (, ''Vosstaniye Pugachyova''; also called the Peasants' War 1773–1775 or Cossack Rebellion) of 1773–1775 was the principal revolt in a series of popular rebellions that took place in the Russian Empire after Catherine ...

of Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

, nomads, peoples of the Volga, and peasants.

The period of Catherine the Great's rule is also known as the Catherinian Era. The ''Manifesto on Freedom of the Nobility'', issued during the short reign of Peter III and confirmed by Catherine, freed Russian nobles from compulsory military or state service. Construction of many mansions of the nobility, in the classical style endorsed by the empress, changed the face of the country. She is often included in the ranks of the enlightened despots. As a patron of the arts, she presided over the age of the Russian Enlightenment

The Russian Age of Enlightenment was a period in the 18th century in which the government began to actively encourage the proliferation of arts and sciences, which had a profound impact on Russian culture. During this time, the first Russian unive ...

, including the establishment of the Smolny Institute of Noble Maidens

The Smolny Institute of Noble Maidens of Saint Petersburg (Russian: Смольный институт благородных девиц Санкт-Петербурга) was the first women's educational institution in Russia that laid the foundatio ...

, the first state-financed higher education institution for women in Europe.

Early life

Catherine was born in

Catherine was born in Stettin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin language, Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital city, capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the Po ...

, Province of Pomerania, Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

, Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, as Princess Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg. Her mother was Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp (24 October 1712 – 30 May 1760) was a member of the German House of Holstein-Gottorp, a princess consort of Anhalt-Zerbst by marriage, and the regent of Anhalt-Zerbst from 1747 to 1752 on behalf of her minor ...

. Her father, Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst (29 November 1690, in Dornburg – 16 March 1747, in Zerbst) was a German prince of the House of Ascania, and the father of Catherine the Great of Russia.

He was a ruler of the Principality of A ...

, belonged to the ruling German family of Anhalt

Saxony-Anhalt (german: Sachsen-Anhalt ; nds, Sassen-Anholt) is a state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony, Thuringia and Lower Saxony. It covers an area of

and has a population of 2.18 million inhabitants, making it the ...

. He failed to become the duke of Duchy of Courland and Semigallia and at the time of his daughter's birth held the rank of a Prussian general in his capacity as governor of the city of Stettin. However, because her second cousin Peter III converted to Orthodox Christianity, her mother's brother became the heir to the Swedish throne and two of her first cousins, Gustav III

Gustav III (29 March 1792), also called ''Gustavus III'', was King of Sweden from 1771 until his assassination in 1792. He was the eldest son of Adolf Frederick of Sweden and Queen Louisa Ulrika of Prussia.

Gustav was a vocal opponent of what ...

and Charles XIII

Charles XIII, or Carl XIII ( sv, Karl XIII, 7 October 1748 – 5 February 1818), was King of Sweden from 1809 and King of Norway from 1814 to his death. He was the second son (and younger brother to King Gustav III) of King Adolf Frederick of Sw ...

, later became Kings of Sweden

This is a list of Swedish kings, queens, regents and viceroys of the Kalmar Union.

History

The earliest record of what is generally considered to be a Swedish king appears in Tacitus' work '' Germania'', c. 100 AD (the king of the Suiones). Ho ...

. In accordance with the custom then prevailing in the ruling dynasties of Germany, she received her education chiefly from a French governess and from tutors. According to her memoirs, Sophie was regarded as a tomboy

A tomboy is a term for a girl or a young woman with masculine qualities. It can include wearing androgynous or unfeminine clothing and actively engage in physical sports or other activities and behaviors usually associated with boys or men. W ...

, and trained herself to master a sword.

Sophie's childhood was very uneventful. She once wrote to her correspondent Baron Grimm: "I see nothing of interest in it." Although Sophie was born a princess, her family had very little money. Her rise to power was supported by her mother Joanna's wealthy relatives, who were both nobles and royal relations. The more than 300 sovereign entities of the Holy Roman Empire, many of them quite small and powerless, made for a highly competitive political system as the various princely families fought for advantage over each other, often via political marriages. For the smaller German princely families, an advantageous marriage was one of the best means of advancing their interests, and the young Sophie was groomed throughout her childhood to be the wife of some powerful ruler in order to improve the position of the reigning house of Anhalt. Besides her native German, Sophie became fluent in French, the lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

of European elites in the 18th century. The young Sophie received the standard education for an 18th-century German princess, with a concentration upon learning the etiquette expected of a lady, French, and Lutheran theology

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

.

Sophie first met her future husband, who would become Peter III of Russia, at the age of 10. Peter was her second cousin. Based on her writings, she found Peter detestable upon meeting him. She disliked his pale complexion and his fondness for alcohol at such a young age. Peter also still played with toy soldiers. She later wrote that she stayed at one end of the castle, and Peter at the other.

Marriage and reign of Peter III

The choice of Princess Sophie as wife of the future tsar was one result of the

The choice of Princess Sophie as wife of the future tsar was one result of the Lopukhina affair

Natalia Fyodorovna Lopukhina (November 11 1699– March 11 1763) was a Russian noble, court official and alleged political conspirator. She was a daughter of Matryona Balk, who was sister of Anna Mons and Willem Mons. She is famous for the Lopu ...

in which Count Jean Armand de Lestocq

Count Jean Armand de L'Estocq (German: ''Johann Hermann Lestocq'', Russian: ''Иван Иванович Лесток''; 29 April 1692, in Lüneburg – 12 June 1767, in Saint Petersburg) was a French adventurer who wielded immense influence on the ...

and King Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

of Prussia took an active part. The objective was to strengthen the friendship between Prussia and Russia, to weaken the influence of Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, and to overthrow the chancellor Alexey Bestuzhev-Ryumin

Count Alexey Petrovich Bestuzhev-Ryumin (russian: Алексе́й Петро́вич Бесту́жев-Рю́мин; 1 June 1693 – 21 April 1766) was a Russian diplomat and chancellor. He was one of the most influential and successful diplomats ...

, a known partisan of the Austrian alliance on whom Russian Empress Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

relied. The diplomatic intrigue failed, largely due to the intervention of Sophie's mother, Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp (24 October 1712 – 30 May 1760) was a member of the German House of Holstein-Gottorp, a princess consort of Anhalt-Zerbst by marriage, and the regent of Anhalt-Zerbst from 1747 to 1752 on behalf of her minor ...

. Historical accounts portray Joanna as a cold, abusive woman who loved gossip and court intrigues. Her hunger for fame centered on her daughter's prospects of becoming empress of Russia, but she infuriated Empress Elizabeth, who eventually banned her from the country for spying for King Frederick. Empress Elizabeth knew the family well and had intended to marry Princess Joanna's brother Charles Augustus

Karl August, sometimes anglicised as Charles Augustus (3 September 1757 – 14 June 1828), was the sovereign Duke of Saxe-Weimar and of Saxe-Eisenach (in personal union) from 1758, Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach from its creation (as a political uni ...

(Karl August von Holstein); however, he died of smallpox in 1727 before the wedding could take place. Despite Joanna's interference, Empress Elizabeth took a strong liking to Sophie, and Sophie and Peter eventually married in 1745.

When Sophie arrived in Russia in 1744, she spared no effort to ingratiate herself not only with Empress Elizabeth but with her husband and with the Russian people as well. She applied herself to learning the Russian language with zeal, rising at night and walking about her bedroom barefoot, repeating her lessons. When she wrote her memoirs, she said she made the decision then to do whatever was necessary and to profess to believe whatever was required of her to become qualified to wear the crown. Although she mastered the language, she retained an accent.

Sophie recalled in her memoirs that as soon as she arrived in Russia, she fell ill with a pleuritis

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other sym ...

that almost killed her. She credited her survival to frequent bloodletting

Bloodletting (or blood-letting) is the withdrawal of blood from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leeches, was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and other bodily flu ...

; in a single day, she had four phlebotomies. Her mother's opposition to this practice brought her the empress's disfavour. When Sophie's situation looked desperate, her mother wanted her confessed by a Lutheran pastor. Awaking from her delirium, however, Sophie said, "I don't want any Lutheran; I want my Orthodox father lergyman. This raised her in the empress's esteem.

Princess Sophie's father, a devout German Lutheran, opposed his daughter's conversion to Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first m ...

. Despite his objections, on 28 June 1744, the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

received Princess Sophie as a member with the new name Catherine (Yekaterina or Ekaterina) and the (artificial) patronymic

A patronymic, or patronym, is a component of a personal name based on the given name of one's father, grandfather (avonymic), or an earlier male ancestor.

Patronymics are still in use, including mandatory use, in many countries worldwide, alt ...

Алексеевна (Alekseyevna, daughter of Aleksey), so that she was in all respects the namesake of Catherine I

Catherine I ( rus, Екатери́на I Алексе́евна Миха́йлова, Yekaterína I Alekséyevna Mikháylova; born , ; – ) was the second wife and empress consort of Peter the Great, and Empress Regnant of Russia from 1725 un ...

, the mother of Elizabeth and the grandmother of Peter III. On the following day, the formal betrothal of Catherine and Peter took place and the long-planned dynastic marriage finally occurred on 21 August 1745 in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. Sophie had turned 16. Her father did not travel to Russia for the wedding. The bridegroom, known as Peter von Holstein-Gottorp, had become Duke of Holstein-Gottorp

Holstein-Gottorp or Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp () is the historiographical name, as well as contemporary shorthand name, for the parts of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, also known as Ducal Holstein, that were ruled by the dukes of Schlesw ...

(located in the north-west of Germany near the border with Denmark) in 1739. The newlyweds settled in the palace of Oranienbaum, which remained the residence of the "young court" for many years. From there, they governed the duchy (which occupied less than a third of the current German state of Schleswig-Holstein, even including that part of Schleswig occupied by Denmark) to obtain experience to govern Russia.

Apart from providing that experience, the marriage was unsuccessful—it was not consummated for years due to Peter III's mental immaturity. After Peter took a mistress, Catherine became involved with other prominent court figures. She soon became popular with several powerful political groups that opposed her husband. Bored with her husband, Catherine became an avid reader of books, mostly in French. She disparaged her husband for his devotion to reading on the one hand "Lutheran prayer-books, the other the history of and trial of some highway robbers who had been hanged or broken on the wheel". It was during this period that she first read Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

and the other ''philosophes'' of the French Enlightenment

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

. As she learned Russian, she became increasingly interested in the literature of her adopted country. Finally, it was the ''Annals'' by Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

that caused what she called a "revolution" in her teenage mind as Tacitus was the first intellectual she read who understood power politics as they are, not as they should be. She was especially impressed with his argument that people do not act for their professed idealistic reasons, and instead she learned to look for the "hidden and interested motives".

According to Alexander Hertzen

Alexander Ivanovich Herzen (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Ге́рцен, translit=Alexándr Ivánovich Gértsen; ) was a Russian writer and thinker known as the "father of Russian socialism" and one of the main fathers of agra ...

, who edited a version of Catherine's memoirs, Catherine had her first sexual relationship with Sergei Saltykov

Count Sergei Vasilievich Saltykov ( rus, link=no, Сергей Васильевич Салтыков, p=sʲɪrˈɡʲej vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ səltɨˈkof; c. 1726 – 1765) was a Russian officer (chamberlain) who became the first lover of Empre ...

while living at Oranienbaum as her marriage to Peter had not been consummated, as Catherine later claimed. Catherine nonetheless left the final version of her memoirs to Paul I in which she explained why Paul had been Peter's son. Sergei Saltykov was used to make Peter jealous, and relations with Saltykov were platonic. Catherine wanted to become an empress herself and did not want another heir to the throne; however, Empress Elizabeth blackmailed Peter and Catherine to produce this heir. Peter and Catherine had both been involved in a 1749 Russian military plot to crown Peter (together with Catherine) in Elizabeth's stead. As a result of this plot, Elizabeth likely wanted to leave both Catherine and her accomplice Peter without any rights to the Russian throne. Elizabeth therefore allowed Catherine to have sexual lovers only after a new legal heir, Catherine and Peter's son, survived and appeared to be strong.

After this, Catherine carried on sexual liaisons over the years with many men, including Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, Grigory Grigoryevich Orlov

Prince Grigory Grigoryevich Orlov (russian: Князь Григорий Григорьевич Орлов; 6 October 1734, Bezhetsky Uyezd – 13 April 1783, Moscow) was a favourite of the Empress Catherine the Great of Russia. He became a leade ...

(1734–1783), Alexander Vasilchikov

Alexander Semyonovich Vasilchikov (russian: Александр Семёнович Васильчиков, tr. ; 1746–1813) was a Russian aristocrat who became the lover of Catherine the Great from 1772 to 1774.

Vasilchikov was an ensign in the ...

, Grigory Potemkin

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin-Tauricheski (, also , ;, rus, Князь Григо́рий Алекса́ндрович Потёмкин-Таври́ческий, Knjaz' Grigórij Aleksándrovich Potjómkin-Tavrícheskij, ɡrʲɪˈɡ ...

, Ivan Rimsky-Korsakov

Ivan Nikolajevich Rimsky-Korsakov, né ''Korsav'' (29 June 1754 in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire – 31 July 1831 in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire) was a Russian courtier and lover of Catherine the Great from 1778 to 1779. He was a memb ...

, and others. She became friends with Princess Ekaterina Vorontsova-Dashkova, the sister of her husband's official mistress. In Dashkov's opinion, Dashkov introduced Catherine to several powerful political groups that opposed her husband; however, Catherine had been involved in military schemes against Elizabeth with the likely goal of subsequently getting rid of Peter III since at least 1749.

Peter III's temperament became quite unbearable for those who resided in the palace. He would announce trying drills in the morning to male servants, who later joined Catherine in her room to sing and dance until late hours.

In 1759, Catherine became pregnant with her second child, Anna, who only lived to 14 months. Due to various rumours of Catherine's promiscuity, Peter was led to believe he was not the child's biological father and is known to have proclaimed, "Go to the devil!" when Catherine angrily dismissed his accusation. She thus spent much of this time alone in her private boudoir

A boudoir (; ) is a woman's private sitting room or salon in a furnished residence, usually between the dining room and the bedroom, but can also refer to a woman's private bedroom. The term derives from the French verb ''bouder'' (to sulk ...

to hide away from Peter's abrasive personality. In the first version of her memoirs, edited and published by Alexander Hertzen, Catherine strongly implied that the real father of her son Paul was not Peter, but rather Saltykov.

Catherine recalled in her memoirs her optimistic and resolute mood before her accession to the throne:

I used to say to myself that happiness and misery depend on ourselves. If you feel unhappy, raise yourself above unhappiness, and so act that your happiness may be independent of all eventualities.

After the death of the Empress Elizabeth on 5 January 1762 ( OS: 25 December 1761), Peter succeeded to the throne as Emperor Peter III, and Catherine became empress consort. The imperial couple moved into the new

After the death of the Empress Elizabeth on 5 January 1762 ( OS: 25 December 1761), Peter succeeded to the throne as Emperor Peter III, and Catherine became empress consort. The imperial couple moved into the new Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Emperor of all the Russias, Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The p ...

in Saint Petersburg. The emperor's eccentricities and policies, including a great admiration for the Prussian king Frederick II, alienated the same groups that Catherine had cultivated. Russia and Prussia had fought each other during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

(1756–1763), and Russian troops had occupied Berlin in 1761. Peter, however, supported Frederick II, eroding much of his support among the nobility. Peter ceased Russian operations against Prussia, and Frederick suggested the partition of Polish territories with Russia. Peter also intervened in a dispute between his Duchy of Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

and Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

over the province of Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

(see Count Johann Hartwig Ernst von Bernstorff

Count Johann Hartwig Ernst von Bernstorff (german: Johann Hartwig Ernst Graf von Bernstorff; 13 May 1712 – 18 February 1772) was a German- Danish statesman and a member of the Bernstorff noble family of Mecklenburg. He was the son of Joachim ...

). As Duke of Holstein-Gottorp

Holstein-Gottorp or Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp () is the historiographical name, as well as contemporary shorthand name, for the parts of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, also known as Ducal Holstein, that were ruled by the dukes of Schlesw ...

, Peter planned war against Denmark, Russia's traditional ally against Sweden.

In July 1762, barely six months after becoming emperor, Peter lingered in Oranienbaum with his Holstein-born courtiers and relatives, while his wife lived in another palace nearby. On the night of 8 July (OS: 27 June 1762), Catherine was given the news that one of her co-conspirators had been arrested by her estranged husband and that all they had been planning must take place at once. The next day, she left the palace and departed for the Ismailovsky Regiment, where she delivered a speech asking the soldiers to protect her from her husband. Catherine then left with the Ismailovsky Regiment to go to the Semenovsky Barracks, where the clergy was waiting to ordain her as the sole occupant of the Russian throne. She had her husband arrested, and forced him to sign a document of abdication, leaving no one to dispute her accession to the throne. On 17 July 1762—eight days after the coup that amazed the outside world and just six months after his accession to the throne—Peter III died at Ropsha

Ropsha ( rus, Ропша, p=ˈropʂə) is a settlement in Lomonosovsky District of Leningrad Oblast, Russia, situated about south of Peterhof and south-west of central Saint Petersburg, at an elevation of to . The palace and park ensemble ...

, possibly at the hands of Alexei Orlov (younger brother to Grigory Orlov, then a court favourite and a participant in the coup). Peter supposedly was assassinated, but it is unknown how he died. The official cause, after an autopsy, was a severe attack of haemorrhoidal colic

Colic or cholic () is a form of pain that starts and stops abruptly. It occurs due to muscular contractions of a hollow tube (small and large intestine, gall bladder, ureter, etc.) in an attempt to relieve an obstruction by forcing content out. ...

and an apoplexy stroke.

At the time of Peter III's overthrow, other potential rivals for the throne included Ivan VI

Ivan VI,; – (Julian calendar should be used in this article) Iván or Ioánn Antónovich (12 August 1740 5 July 1764) was an infant emperor of Russia who was overthrown by his cousin Elizabeth Petrovna in 1741. He was only two months old whe ...

(1740–1764), who had been confined at Schlüsselburg

Shlisselburg ( rus, Шлиссельбу́рг, p=ʂlʲɪsʲɪlʲˈburk; german: Schlüsselburg; fi, Pähkinälinna; sv, Nöteborg), formerly Oreshek (Орешек) (1323–1611) and Petrokrepost (Петрокрепость) (1944–1992), is ...

in Lake Ladoga from the age of six months and who was thought to be insane. Ivan VI was assassinated during an attempt to free him as part of a failed coup. Like Empress Elizabeth before her, Catherine had given strict instructions that Ivan was to be killed in the event of any such attempt. Yelizaveta Alekseyevna Tarakanova

Princess Tarakanova (c. 1745 – ) was a pretender to the Russian throne. She styled herself, among other names, ''Knyazhna Yelizaveta Vladimirskaya'' (Princess of Vladimir), ''Fräulein Frank'', and ''Madame Trémouille''. Tarakanova (''t ...

(1753–1775) was another potential rival.

Although Catherine did not descend from the Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

dynasty, her ancestors included members of the Rurik dynasty

The Rurik dynasty ( be, Ру́рыкавічы, Rúrykavichy; russian: Рю́риковичи, Ryúrikovichi, ; uk, Рю́риковичі, Riúrykovychi, ; literally "sons/scions of Rurik"), also known as the Rurikid dynasty or Rurikids, was ...

, which preceded the Romanovs. She succeeded her husband as empress regnant

A queen regnant (plural: queens regnant) is a female monarch, equivalent in rank and title to a king, who reigns ''suo jure'' (in her own right) over a realm known as a "kingdom"; as opposed to a queen consort, who is the wife of a reigning ...

, following the precedent established when Catherine I succeeded her husband Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

in 1725. Historians debate Catherine's technical status, whether as a regent or as a usurper

A usurper is an illegitimate or controversial claimant to power, often but not always in a monarchy. In other words, one who takes the power of a country, city, or established region for oneself, without any formal or legal right to claim it as ...

, tolerable only during the minority of her son, Grand Duke Paul.

Reign (1762–1796)

Coronation (1762)

Catherine was crowned at the Assumption Cathedral in Moscow on 22 September 1762. Her coronation marks the creation of one of the main treasures of the Romanov dynasty, theImperial Crown of Russia

The Imperial Crown of Russia (russian: Императорская Корона России), also known as the Great Imperial Crown (russian: Великая Императорская Корона), was used by the monarchs of Russia from 1762 ...

, designed by Swiss-French court diamond jeweller Jérémie Pauzié. Inspired by Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

design, the crown was constructed of two half spheres, one gold and one silver, representing the eastern and western Roman empires, divided by a foliate garland and fastened with a low hoop. The crown contains 75 pearls and 4,936 Indian diamonds forming laurel and oak leaves, the symbols of power and strength, and is surmounted by a 398.62-carat ruby spinel that previously belonged to the Empress Elizabeth, and a diamond cross. The crown was produced in a record two months and weighed 2.3 kg (5.1 lbs). From 1762, the Great Imperial Crown was the coronation crown of all Romanov emperors until the monarchy's abolition in 1917. It is one of the main treasures of the Romanov dynasty and is now on display in the Moscow Kremlin Armoury Museum.

Foreign affairs

During her reign, Catherine extended the borders of the

During her reign, Catherine extended the borders of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

by some , absorbing New Russia

Novorossiya, literally "New Russia", is a historical name, used during the era of the Russian Empire for an administrative area that would later become the southern mainland of Ukraine: the region immediately north of the Black Sea and Crimea. ...

, Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, the North Caucasus

The North Caucasus, ( ady, Темыр Къафкъас, Temır Qafqas; kbd, Ишхъэрэ Къаукъаз, İṩxhərə Qauqaz; ce, Къилбаседа Кавказ, Q̇ilbaseda Kavkaz; , os, Цӕгат Кавказ, Cægat Kavkaz, inh, ...

, right-bank Ukraine

Right-bank Ukraine ( uk , Правобережна Україна, ''Pravoberezhna Ukrayina''; russian: Правобережная Украина, ''Pravoberezhnaya Ukraina''; pl, Prawobrzeżna Ukraina, sk, Pravobrežná Ukrajina, hu, Jobb p ...

, Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

, Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

, and Courland

Courland (; lv, Kurzeme; liv, Kurāmō; German and Scandinavian languages: ''Kurland''; la, Curonia/; russian: Курляндия; Estonian: ''Kuramaa''; lt, Kuršas; pl, Kurlandia) is one of the Historical Latvian Lands in western Latvia. ...

at the expense, mainly, of two powers—the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

.

Catherine's foreign minister,

Catherine's foreign minister, Nikita Panin

Count Nikita Ivanovich Panin (russian: Ники́та Ива́нович Па́нин) () was an influential Russian statesman and political mentor to Catherine the Great for the first 18 years of her reign (1762-1780). In that role, he advocated ...

(in office 1763–1781), exercised considerable influence from the beginning of her reign. A shrewd statesman, Panin dedicated much effort and millions of rubles to setting up a "Northern Accord" between Russia, Prussia, Poland and Sweden, to counter the power of the Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon barrel aged beer, a type of beer aged in bourbon barrels

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* A beer produced by Bras ...

–Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

League. When it became apparent that his plan could not succeed, Panin fell out of favour and Catherine had him replaced with Ivan Osterman

Count Ivan Andreyevich Osterman (russian: Иван Андреевич Остерман; 1725–1811) was a Russian statesman and the son of Andrei Osterman.

After Osterman's father fell into disgrace, Ivan Osterman was transferred from the Imperi ...

(in office 1781–1797).K. D. Bugrov, "Nikita Panin and Catherine II: Conceptual aspect of political relations". ''RUDN Journal of Russian History'' 4 (2010): 38–52.

Catherine agreed to a commercial treaty

A commercial treaty is a formal agreement between Sovereign state, states for the purpose of establishing mutual rights and regulating conditions of trade. It is a bilateral act whereby definite arrangements are entered into by each contracting par ...

with Great Britain in 1766, but stopped short of a full military alliance. Although she could see the benefits of Britain's friendship, she was wary of Britain's increased power following its complete victory in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, which threatened the European balance of power

The European balance of power is the tenet in international relations that no single power should be allowed to achieve hegemony over a substantial part of Europe. During much of the Modern Age, the balance was achieved by having a small number of ...

.

Russo-Turkish Wars

Peter the Great had succeeded in gaining a toehold in the south, on the edge of the Black Sea, in theAzov campaigns

Azov (russian: Азов), previously known as Azak,

is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. Population:

History

Early settlements in the vicinity

The mout ...

. Catherine completed the conquest of the south, making Russia the dominant power in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

after the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774. Russia inflicted some of the heaviest defeats ever suffered by the Ottoman Empire, including the Battle of Chesma

The naval Battle of Chesme took place on 5–7 July 1770 during the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) near and in Çeşme (Chesme or Chesma) Bay, in the area between the western tip of Anatolia and the island of Chios, which was the site of a numb ...

(5–7 July 1770) and the Battle of Kagul

The Battle of Cahul (russian: Сражение при Кагуле, ) occurred on 1 August 1770 (21 July 1770 in Julian Calendar) during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774. It was the decisive and most important land battle of the war and one o ...

(21 July 1770). In 1769, a last major Crimean–Nogai slave raid, which ravaged the Russian held territories in Ukraine, saw the capture of up to 20,000 slaves.

The Russian victories procured access to the Black Sea and allowed Catherine's government to incorporate present-day southern Ukraine, where the Russians founded the new cities of Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, Nikolayev, Yekaterinoslav

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper Rive ...

(literally: "the Glory of Catherine"), and Kherson

Kherson (, ) is a port city of Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers appr ...

. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca ( tr, Küçük Kaynarca Antlaşması; russian: Кючук-Кайнарджийский мир), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on 21 July 1774, in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kayna ...

, signed 10 July 1774, gave the Russians territories at Azov

Azov (russian: Азов), previously known as Azak,

is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. Population:

History

Early settlements in the vicinity

The mo ...

, Kerch

Kerch ( uk, Керч; russian: Керчь, ; Old East Slavic: Кърчевъ; Ancient Greek: , ''Pantikápaion''; Medieval Greek: ''Bosporos''; crh, , ; tr, Kerç) is a city of regional significance on the Kerch Peninsula in the east of t ...

, Yenikale

Yeni-Kale ( uk, Єні-Кале; russian: Еникале; tr, Yenikale; crh, Yeñi Qale, also spelled as ''Yenikale'' and ''Eni-Kale'' and ''Yeni-Kaleh'' or ''Yéni-Kaleb'') is a fortress on the shore of Kerch Strait in the city of Kerch.

Histor ...

, Kinburn, and the small strip of Black Sea coast between the rivers Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and B ...