Burkina Faso (, ; , ff, ð¤ð¤µð¤ªð¤³ð¤ð¤²ð¤¢ ð¤ð¤¢ð¤§ð¤®, italic=no) is a

landlocked country

A landlocked country is a country that does not have territory connected to an ocean or whose coastlines lie on endorheic basin, endorheic basins. There are currently 44 landlocked countries and 4 landlocked list of states with limited recogni ...

in

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

with an area of , bordered by

Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, ð¤ð¤«ð¤²ð¥ð¤£ð¤¢ð¥ð¤²ð¤£ð¤ ð¤ð¤¢ð¥ð¤¤ð¤, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جÙ

ÙÙرÙØ© Ù

اÙÙ, JumhÅ«riyyÄt MÄlÄ« is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali ...

to the northwest,

Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languages[Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the north ...](_blank)

to the southeast,

Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

and

Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

to the south, and the

Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre is ...

to the southwest. It has a population of 20,321,378.

Previously called

Republic of Upper Volta

The Republic of Upper Volta (french: République de Haute-Volta) was a landlocked West African country established on 11 December 1958 as a self-governing colony within the French Community. Before becoming autonomous, it had been part of the ...

(1958â1984), it was

renamed Burkina Faso by

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966â2010 Japanese ful ...

Thomas Sankara

Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara (; 21 December 1949 â 15 October 1987) was a Burkinabé military officer, MarxistâLeninist revolutionary, and Pan-Africanist, who served as President of Burkina Faso from his coup in 1983 to his deposition a ...

. Its citizens are known as ''Burkinabè'' ( ), and its

capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

and largest city is

Ouagadougou

Ouagadougou ( , , ) is the capital and largest city of Burkina Faso and the administrative, communications, cultural, and economic centre of the nation. It is also the country's largest city, with a population of 2,415,266 in 2019. The city's n ...

.

The largest

ethnic group

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

in Burkina Faso is the

Mossi people Mossi may refer to:

*Mossi people

*Mossi language

*Mossi Kingdoms

* the Mossi, a Burkinabe variant of the Dongola horse

*Mossi (given name)

*Mossi (surname)

See also

*Mossie (disambiguation)

*Mossy (disambiguation)

Mossy may refer to:

Places

*Mos ...

, who settled the area in the 11th and 13th centuries. They established powerful kingdoms such as the Ouagadougou, Tenkodogo, and Yatenga. In 1896, it was

colonize

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country â by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

d by the

French as part of

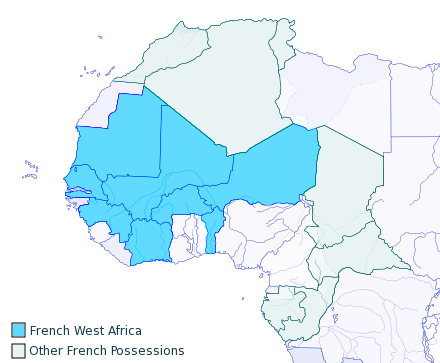

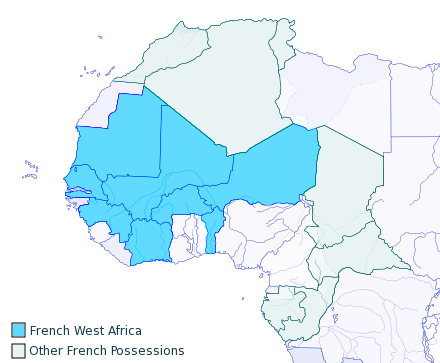

French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now Burki ...

; in 1958, Upper Volta became a

self-governing colony

In the British Empire, a self-governing colony was a colony with an elected government in which elected rulers were able to make most decisions without referring to the colonial power with nominal control of the colony. This was in contrast to ...

within the

French Community

The French Community (1958â1960; french: Communauté française) was the constitutional organization set up in 1958 between France and its remaining African colonies, then in the process of decolonization. It replaced the French Union, which ...

. In 1960, it gained full independence with

Maurice Yaméogo

Maurice Yaméogo (31 December 1921 â 15 September 1993) was the first President of the Republic of Upper Volta, now called Burkina Faso, from 1959 until 1966.

"Monsieur Maurice" embodied the Voltaic state at the moment of independence. However ...

as

president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966â2010 Japanese ful ...

. Throughout the decades post independence, the country was subject to instability,

droughts

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

, famines and corruption. Various coups have also taken place in the country, in

1966,

1980,

1982

Events January

* January 1 â In Malaysia and Singapore, clocks are adjusted to the same time zone, UTC+8 (GMT+8.00).

* January 13 â Air Florida Flight 90 crashes shortly after takeoff into the 14th Street bridges, 14th Street Bridge in ...

,

1983,

1987

File:1987 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: The MS Herald of Free Enterprise capsizes after leaving the Port of Zeebrugge in Belgium, killing 193; Northwest Airlines Flight 255 crashes after takeoff from Detroit Metropolitan Airport, k ...

, and twice in 2022, in

January

January is the first month of the year in the Julian and Gregorian calendars and is also the first of seven months to have a length of 31 days. The first day of the month is known as New Year's Day. It is, on average, the coldest month of the ...

and in

September

September is the ninth month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars, the third of four months to have a length of 30 days, and the fourth of five months to have a length of fewer than 31 days. September in the Northern H ...

, as well as

an attempt in 1989 and another in

2015

File:2015 Events Collage new.png, From top left, clockwise: Civil service in remembrance of November 2015 Paris attacks; Germanwings Flight 9525 was purposely crashed into the French Alps; the rubble of residences in Kathmandu following the Apri ...

.

Thomas Sankara served as the country's president from 1982 until he was killed in the 1987 coup led by

Blaise Compaoré

Blaise Compaoré (born 3 February 1951)''Profiles of People in Power: The World's Government Leaders'' (2003), page 76â77. , who became president and ruled the country until

his removal on 31 October 2014. Sankara had conducted an ambitious

socioeconomic

Socioeconomics (also known as social economics) is the social science that studies how economic activity affects and is shaped by social processes. In general it analyzes how modern societies progress, stagnate, or regress because of their local ...

programme which included a nationwide

literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, huma ...

campaign,

land redistribution

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

to

peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

s, railway and road construction, and the outlawing of

female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting, female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and female circumcision, is the ritual cutting or removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. The practice is found ...

,

forced marriage

Forced marriage is a marriage in which one or more of the parties is married without their consent or against their will. A marriage can also become a forced marriage even if both parties enter with full consent if one or both are later force ...

s, and

polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

.

Burkina Faso has been severely affected by the rise of

Islamist terrorism in the Sahel since the mid-2010s. Several

militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s, partly allied with the

Islamic State

An Islamic state is a State (polity), state that has a form of government based on sharia, Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical Polity, polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a t ...

(IS) or

al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

, operate in Burkina Faso and across the border in

Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, ð¤ð¤«ð¤²ð¥ð¤£ð¤¢ð¥ð¤²ð¤£ð¤ ð¤ð¤¢ð¥ð¤¤ð¤, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جÙ

ÙÙرÙØ© Ù

اÙÙ, JumhÅ«riyyÄt MÄlÄ« is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali ...

and

Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languages[internally displaced person

An internally displaced person (IDP) is someone who is forced to leave their home but who remains within their country's borders. They are often referred to as refugees, although they do not fall within the legal definitions of a refugee.

A ...](_blank)

s.

Burkina Faso's military seized power in a

coup d'état on 23â24 January 2022, overthrowing President

Roch Marc Kaboré. On 31 January, the military junta restored the constitution and appointed

Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba

Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba (; born January 1981) is a Burkina Faso, Burkinabé military officer who served as interim president of Burkina Faso from 31 January 2022 to 30 September 2022, when he was removed in a September 2022 Burkina Faso coup d ...

as interim president, who was himself overthrown in a

second coup on 30 September and replaced by military captain

Ibrahim Traoré

Ibrahim Traoré (born 1988) is a Burkinabé military officer who has been the interim leader of Burkina Faso since the 30 September 2022 coup d'état which ousted interim president Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba. At age 34, Traoré is the world's ...

.

Burkina Faso is one of the

least developed countries with a GDP of $16.226 billion. Approximately 63.8 percent of its population practices

Islam

Islam (; ar, ÛاÙÙإسÙÙاÙ

, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

, while 26.3 percent practice Christianity.

The country's official language of government and business is

French. There are 60 indigenous languages officially recognized by the Burkinabè government, with the most common language,

Mooré

The Mossi language (Mooré) is a Gur language of the OtiâVolta branch and one of two official regional languages of Burkina Faso. It is the language of the Mossi people, spoken by approximately 8 million people in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Cote d ...

, spoken by over half the population.

The country is governed as a

semi-presidential republic

A semi-presidential republic, is a republic in which a president exists alongside a prime minister and a cabinet, with the latter two being responsible to the legislature of the state. It differs from a parliamentary republic in that it has a ...

with executive, legislative and judicial powers. Burkina Faso is a member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

,

La Francophonie

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figur ...

and the

Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

An organization or organisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is an entityâsuch as a company, an institution, or an associationâcomprising one or more people and having a particular purpose.

The word is derived from ...

. It is currently suspended from

ECOWAS

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS; also known as in French and Portuguese) is a regional political and economic union of fifteen countries located in West Africa. Collectively, these countries comprise an area of , and in ...

and the

African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the Africa ...

.

Etymology

Formerly the Republic of Upper Volta, the country was renamed "Burkina Faso" on 4 August 1984 by then-President Thomas Sankara. The words "Burkina" and "Faso" stem from different languages spoken in the country: "Burkina" comes from

Mossi and means "upright", showing how the people are proud of their integrity, while "Faso" comes from the

Dioula language

Dyula (or Jula, Dioula, ''Julakan'' ßß߬ßß߬ßßß²) is a language of the Mande language family spoken mainly in Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and Mali, and also in some other countries, including Ghana, Guinea and Guinea-Bissau. It is one of ...

(as written in

N'Ko

N'Ko () is a script devised by Solomana Kante in 1949, as a modern writing system for the Mandé languages of West Africa. The term ''N'Ko'', which means ''I say'' in all Mandé languages, is also used for the Mandé literary standard written i ...

: ''faso'') and means "fatherland" (literally, "father's house"). The "-bè" suffix added onto "Burkina" to form the demonym "Burkinabè" comes from the

Fula language

Fula ,Laurie Bauer, 2007, ''The Linguistics Studentâs Handbook'', Edinburgh also known as Fulani or Fulah (, , ; Adlam: , , ), is a Senegambian language spoken by around 30 million people as a set of various dialects in a continuum that stre ...

and means "women or men". The CIA summarizes the etymology as "land of the honest (incorruptible) men".

The French colony of Upper Volta was named for its location on the upper courses of the

Volta River

The Volta River is the main river system in the West African country of Ghana. It flows south into Ghana from the Bobo-Dioulasso highlands of Burkina Faso. The main parts of the river are the Black Volta, the White Volta, and the Red Volta. In ...

(the

Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

,

Red

Red is the color at the long wavelength end of the visible spectrum of light, next to orange and opposite violet. It has a dominant wavelength of approximately 625â740 nanometres. It is a primary color in the RGB color model and a secondar ...

and

White Volta

The White Volta or Nakambé is the headstream of the Volta River, Ghana's main waterway. The White Volta emerges in northern Burkina Faso, flows through North Ghana and empties into Lake Volta in Ghana. The White Volta's main tributaries are the ...

).

History

Early history

The northwestern part of present-day Burkina Faso was populated by

hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

s from 14000 BCE to 5000 BCE. Their tools, including

scrapers,

chisel

A chisel is a tool with a characteristically shaped cutting edge (such that wood chisels have lent part of their name to a particular grind) of blade on its end, for carving or cutting a hard material such as wood, stone, or metal by hand, stru ...

s and

arrowhead

An arrowhead or point is the usually sharpened and hardened tip of an arrow, which contributes a majority of the projectile mass and is responsible for impacting and penetrating a target, as well as to fulfill some special purposes such as sign ...

s, were discovered in 1973 through

archaeological excavations

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be condu ...

.

Agricultural settlements were established between 3600 and 2600 BCE.

The

Bura culture was an

Iron-Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly a ...

civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Ci ...

centred in the southwest portion of modern-day Niger and in the southeast part of contemporary Burkina Faso.

[UNESCO World Heritage Centre]

"Site archéologique de Bura"

UNESCO. Iron industry

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ...

, in

smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a ch ...

and

forging

Forging is a manufacturing process involving the shaping of metal using localized compressive forces. The blows are delivered with a hammer (often a power hammer) or a die. Forging is often classified according to the temperature at which i ...

for tools and weapons, had developed in

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

by 1200 BCE. To date, the oldest evidence of iron smelting found in Burkina Faso dates from 800 to 700 BC and form part of the

Ancient Ferrous Metallurgy World Heritage Site. From the 3rd to the 13th centuries CE, the

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

Bura culture existed in the territory of present-day southeastern Burkina Faso and southwestern Niger. Various ethnic groups of present-day Burkina Faso, such as the

Mossi,

Fula

Fula may refer to:

*Fula people (or Fulani, FulÉe)

*Fula language (or Pulaar, Fulfulde, Fulani)

**The Fula variety known as the Pulaar language

**The Fula variety known as the Pular language

**The Fula variety known as Maasina Fulfulde

*Al-Fula ...

and

Dioula, arrived in successive waves between the 8th and 15th centuries. From the 11th century, the Mossi people established

several separate kingdoms.

8th century to 18th century

There is debate about the exact dates when Burkina Faso's many ethnic groups arrived to the area. The

Proto-Mossi arrived in the far Eastern part of what is today Burkina Faso sometime between the 8th and 11th centuries, the

Samo

Samo (â) founded the first recorded political union of Slavic tribes, known as Samo's Empire (''realm'', ''kingdom'', or ''tribal union''), stretching from Silesia to present-day Slovakia, ruling from 623 until his death in 658. According to ...

arrived around the 15th century,

[ Rupley, p. 28] the

Dogon

Dogon may refer to:

*Dogon people, an ethnic group living in the central plateau region of Mali, in West Africa

*Dogon languages, a small, close-knit language family spoken by the Dogon people of Mali

*'' Dogon A.D.'', an album by saxophonist Juliu ...

lived in Burkina Faso's north and northwest regions until sometime in the 15th or 16th centuries and many of the other ethnic groups that make up the country's population arrived in the region during this time.

During the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, the Mossi established several separate kingdoms including those of Tenkodogo, Yatenga, Zandoma, and Ouagadougou.

["Encyclopedia of the Nations." History. Advameg, Inc., n.d. Web. 8 October 2014.] Sometime between 1328 and 1338 Mossi warriors raided

Timbuktu

Timbuktu ( ; french: Tombouctou;

Koyra Chiini: ); tmh, label=Tuareg, script=Tfng, âµâµâ´±â´¾âµ, Tin Buqt a city in Mali, situated north of the Niger River. The town is the capital of the Tombouctou Region, one of the eight administrativ ...

but the Mossi were defeated by

Sonni Ali

Sunni Ali, also known as Si Ali, Sunni Ali Ber (Ber meaning "the Great"), was born in Ali Kolon. He reigned from about 1464 to 1492. Sunni Ali was the first king of the Songhai Empire, located in Africa and the 15th ruler of the Sunni dynasty. ...

of

Songhai at the Battle of Kobi in Mali in 1483.

During the early 16th century the Songhai conducted many slave raids into what is today Burkina Faso.

During the 18th century the Gwiriko Empire was established at

Bobo Dioulasso

Bobo-Dioulasso is a city in Burkina Faso with a population of 904,920 (); it is the second-largest city in the country, after Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso's capital. The name means "home of the Bobo-Dioula".

The local Bobo-speaking population (r ...

and ethnic groups such as the Dyan, Lobi, and Birifor settled along the

Black Volta

The Black Volta or Mouhoun is a river that flows through Burkina Faso for approximately 1,352 km (840 mi) to the White Volta in Dagbon, Ghana, the upper end of Lake Volta. The source of the Black Volta is in the Cascades Region of Burki ...

.

From colony to independence (1890sâ1958)

Starting in the early 1890s during the European

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonisation of Africa, colonization of most of Africa by seven Western Europe, Western European powers during a ...

, a series of European military officers made attempts to claim parts of what is today Burkina Faso. At times these

colonialists

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

and their armies fought the local peoples; at times they forged alliances with them and made treaties. The colonialist officers and their home governments also made treaties among themselves. The territory of Burkina Faso was invaded by

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, becoming a

French protectorate in 1896.

The eastern and western regions, where a standoff against the forces of the powerful ruler

Samori Ture

Samory Toure ( â June 2, 1900), also known as Samori Toure, Samory Touré, or Almamy Samore Lafiya Toure, was a Muslim cleric, a military strategist, and the founder and leader of the Wassoulou Empire, an Islamic empire that was in present-day ...

complicated the situation, came under French occupation in 1897. By 1898, the majority of the territory corresponding to Burkina Faso was nominally conquered; however, French control of many parts remained uncertain.

The

Franco-British Convention of 14 June 1898 created the country's modern borders. In the French territory, a war of conquest against local communities and political powers continued for about five years. In 1904, the largely pacified territories of the

Volta basin were integrated into the

Upper Senegal and Niger

Upper Senegal and Niger () was a colony in French West Africa, created on 21 October 1904 from colonial Senegambia and Niger by the decree "For the Reorganisation of the general government of French West Africa".

At its creation, the "Colony o ...

colony of

French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now Burki ...

as part of the reorganization of the French West African colonial empire. The colony had its capital in

Bamako

Bamako ( bm, ßß¡ß߬ßß߬ ''Bà makÉÌ'', ff, ð¤ð¤¢ð¤¥ð¤¢ð¤³ð¤® ''Bamako'') is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Mali, with a 2009 population of 1,810,366 and an estimated 2022 population of 2.81 million. It is located on t ...

.

The language of colonial administration and schooling became French. The public education system started from humble origins. Advanced education was provided for many years during the colonial period in Dakar.

The indigenous population was highly discriminated against. For example, African children were not allowed to ride bicycles or pick fruit from trees, "privileges" reserved for the children of colonists. Violating these regulations could land parents in jail.

Draftees from the territory participated in the European fronts of

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in the battalions of the

Senegalese Rifles. Between 1915 and 1916, the districts in the western part of what is now Burkina Faso and the bordering eastern fringe of Mali became the stage of one of the most important armed oppositions to colonial government: the

Volta-Bani War

The Volta-Bani War was an anti-colonial rebellion which took place in French West Africa (specifically, the areas of modern Burkina Faso and Mali) between 1915 and 1917. It was a war between an indigenous African force drawn from a heterogeneous ...

.

The French government finally suppressed the movement but only after suffering defeats. It also had to organize its largest expeditionary force of its colonial history to send into the country to suppress the insurrection. Armed opposition wracked the Sahelian north when the

Tuareg

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym: ''ImuhaÉ£/ImuÅ¡aÉ£/ImaÅ¡eÉ£Än/ImajeÉ£Än'') are a large Berber ethnic group that principally inhabit the Sahara in a vast area stretching from far southwestern Libya to southern A ...

and allied groups of the Dori region ended their truce with the government.

French Upper Volta

Upper Volta (french: Haute-Volta) was a colony of French West Africa established in 1919 in the territory occupied by present-day Burkina Faso. It was formed from territories that had been part of the colonies of Upper Senegal and Niger and th ...

was established on 1 March 1919. The French feared a recurrence of armed uprising and had related economic considerations. To bolster its administration, the colonial government separated the present territory of Burkina Faso from Upper Senegal and Niger.

The new colony was named ''Haute Volta,'' named for its location on the upper courses of the

Volta River

The Volta River is the main river system in the West African country of Ghana. It flows south into Ghana from the Bobo-Dioulasso highlands of Burkina Faso. The main parts of the river are the Black Volta, the White Volta, and the Red Volta. In ...

(the

Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

,

Red

Red is the color at the long wavelength end of the visible spectrum of light, next to orange and opposite violet. It has a dominant wavelength of approximately 625â740 nanometres. It is a primary color in the RGB color model and a secondar ...

and

White Volta

The White Volta or Nakambé is the headstream of the Volta River, Ghana's main waterway. The White Volta emerges in northern Burkina Faso, flows through North Ghana and empties into Lake Volta in Ghana. The White Volta's main tributaries are the ...

), and François Charles Alexis Ãdouard Hesling became its first

governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

. Hesling initiated an ambitious road-making program to improve infrastructure and promoted the growth of cotton for export. The cotton policy â based on

coercion

Coercion () is compelling a party to act in an involuntary manner by the use of threats, including threats to use force against a party. It involves a set of forceful actions which violate the free will of an individual in order to induce a desi ...

â failed, and revenue generated by the colony stagnated. The colony was dismantled on 5 September 1932, being split between the French colonies of

Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre is ...

,

French Sudan

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with France ...

and

Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languages[World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesâincluding all of the great powersâforming two opposin ...](_blank)

. On 4 September 1947, it revived the colony of Upper Volta, with its previous boundaries, as a part of the

French Union

The French Union () was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial empire system, colloquially known as the " French Empire" (). It was the formal end of the "indigenous" () status of French subje ...

. The French designated its colonies as departments of

metropolitan France

Metropolitan France (french: France métropolitaine or ''la Métropole''), also known as European France (french: Territoire européen de la France) is the area of France which is geographically in Europe. This collective name for the European ...

on the European continent.

On 11 December 1958 the colony achieved

self-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

as the

Republic of Upper Volta

The Republic of Upper Volta (french: République de Haute-Volta) was a landlocked West African country established on 11 December 1958 as a self-governing colony within the French Community. Before becoming autonomous, it had been part of the ...

; it joined the Franco-African Community. A revision in the organization of French Overseas Territories had begun with the passage of the Basic Law (Loi Cadre) of 23 July 1956. This act was followed by reorganization measures approved by the French parliament early in 1957 to ensure a large degree of self-government for individual territories. Upper Volta became an autonomous republic in the French community on 11 December 1958. Full independence from France was received in 1960.

Upper Volta (1958â1984)

The Republic of Upper Volta (french: link=no, République de Haute-Volta) was established on 11 December 1958 as a

self-governing colony

In the British Empire, a self-governing colony was a colony with an elected government in which elected rulers were able to make most decisions without referring to the colonial power with nominal control of the colony. This was in contrast to ...

within the

French Community

The French Community (1958â1960; french: Communauté française) was the constitutional organization set up in 1958 between France and its remaining African colonies, then in the process of decolonization. It replaced the French Union, which ...

. The name ''Upper Volta'' related to the nation's location along the upper reaches of the

Volta River

The Volta River is the main river system in the West African country of Ghana. It flows south into Ghana from the Bobo-Dioulasso highlands of Burkina Faso. The main parts of the river are the Black Volta, the White Volta, and the Red Volta. In ...

. The river's three

tributaries

A tributary, or affluent, is a stream or river that flows into a larger stream or main stem (or parent) river or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean. Tributaries and the main stem river drain the surrounding drainage b ...

are called the

Black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

,

White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

and

Red Volta

The Red Volta or Nazinon is a waterway flowing located in West Africa. It emerges near Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso and has a length of about 320 km which it joins the White Volta in Ghana.

The river is primarily located in Burkina Faso and ...

. These were expressed in the three colors of the

former national flag.

Before attaining autonomy, it had been French Upper Volta and part of the French Union. On 5 August 1960, it attained full independence from

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. The first president,

Maurice Yaméogo

Maurice Yaméogo (31 December 1921 â 15 September 1993) was the first President of the Republic of Upper Volta, now called Burkina Faso, from 1959 until 1966.

"Monsieur Maurice" embodied the Voltaic state at the moment of independence. However ...

, was the leader of the

Voltaic Democratic Union

The African Democratic Rally (''Rassemblement Démocratique Africain'') is a political party in Burkina Faso. It was originally known as the Voltaic Democratic Union-African Democratic Rally (UDV-RDA) and was formed in 1957 as the Voltaic sectio ...

(UDV). The 1960 constitution provided for election by

universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...

of a president and a national assembly for five-year terms. Soon after coming to power, Yaméogo banned all political parties other than the UDV. The government lasted until 1966. After much unrest, including mass demonstrations and strikes by students, labor unions, and civil servants, the military intervened.

Lamizana's rule and multiple coups

The

1966 military coup deposed Yaméogo, suspended the constitution, dissolved the National Assembly, and placed Lt. Col.

Sangoulé Lamizana

Aboubakar Sangoul̩ Lamizana (31 January 1916 Р26 May 2005) was a Burkinab̩ military officer who served as the President of Upper Volta (since 1984 renamed Burkina Faso), in power from 3 January 1966, to 25 November 1980. He held the a ...

at the head of a government of senior army officers. The army remained in power for four years. On 14 June 1976, the Voltans ratified a new constitution that established a four-year transition period toward complete civilian rule. Lamizana remained in power throughout the 1970s as president of military or mixed civil-military governments. Lamizana's rule coincided with the beginning of the

Sahel drought

The Sahel region of Africa has long experienced a series of historic droughts, dating back to at least the 17th century. The Sahel region is a climate zone sandwiched between the Sudanian Savanna to the south and the Sahara desert to the north, ...

and famine which had a devastating impact on Upper Volta and neighboring countries. After conflict over the 1976 constitution, a new constitution was written and approved in 1977. Lamizana was re-elected by open elections in 1978.

Lamizana's government faced problems with the country's traditionally powerful trade unions, and on 25 November 1980, Col.

Saye Zerbo

Saye Zerbo (27 August 1932 â 19 September 2013) was a Burkinabé military officer who was the third President of the Republic of Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) from 25 November 1980 until 7 November 1982. He led a coup in 1980, but was resisted ...

overthrew President Lamizana in a

bloodless coup

A nonviolent revolution is a revolution conducted primarily by unarmed civilians using tactics of civil resistance, including various forms of nonviolent protest, to bring about the departure of governments seen as entrenched and authoritari ...

. Colonel Zerbo established the Military Committee of Recovery for National Progress as the supreme governmental authority, thus eradicating the 1977 constitution.

Colonel Zerbo also encountered resistance from trade unions and was overthrown two years later by Maj. Dr.

Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo

Jean-Baptiste Philippe Ouédraogo (; born 30 June 1942), also referred to by his initials JBO, is a Burkinabé physician and retired military officer who served as President of Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso) from 8 November 1982 to 4 August 198 ...

and the Council of Popular Salvation (CSP) in the

1982 Upper Voltan coup d'état

The 1982 Upper Voltan coup d'état took place in the Republic of Upper Volta (today Burkina Faso) on 7 November 1982. The coup, led by the little-known Colonel Gabriel Yoryan Somé and a slew of other junior officers within the military, many of t ...

. The CSP continued to ban political parties and organizations, yet promised a transition to civilian rule and a new constitution.

1983 coup d'état

Infighting developed between the right and left factions of the CSP. The leader of the leftists, Capt.

Thomas Sankara

Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara (; 21 December 1949 â 15 October 1987) was a Burkinabé military officer, MarxistâLeninist revolutionary, and Pan-Africanist, who served as President of Burkina Faso from his coup in 1983 to his deposition a ...

, was appointed prime minister in January 1983, but was subsequently arrested. Efforts to free him, directed by Capt.

Blaise Compaoré

Blaise Compaoré (born 3 February 1951)''Profiles of People in Power: The World's Government Leaders'' (2003), page 76â77. , resulted in a military coup d'état on 4 August 1983.

The coup brought Sankara to power and his government began to implement a series of revolutionary programs which included mass-vaccinations, infrastructure improvements, the expansion of women's rights, encouragement of domestic agricultural consumption, and anti-desertification projects.

['' Thomas Sankara: the Upright Man'' by '']California Newsreel

California Newsreel, was founded in 1968 as the San Francisco branch of the national film making collective Newsreel. It is an American non-profit, social justice film distribution and production company still based in San Francisco, California. Th ...

''

Burkina Faso (since 1984)

On 2 August 1984, on President Sankara's initiative, the country's name changed from "Upper Volta" to "Burkina Faso", or ''land of the honest men''; (the literal translation is ''land of the upright men''.) The presidential decree was confirmed by the National Assembly on 4 August. The demonym for people of Burkina Faso, "Burkinabè", includes expatriates or descendants of people of Burkinabè origin.

Sankara's government comprised the National Council for the Revolution (CNR â fr , Conseil national révolutionnaire), with Sankara as its president, and established popular

Committees for the Defense of the Revolution

Committees for the Defense of the Revolution ( es, Comités de Defensa de la Revolución, links=no), or CDR, are a network of neighborhood committees across Cuba. The organizations, described as the "eyes and ears of the Revolution," exist to h ...

(CDRs). The

Pioneers of the Revolution

The Pioneers of the Revolution () was a youth organisation in Burkina Faso, modelled along the pattern of the pioneer movements typically operated by communist parties, such as the contemporary Pioneers of Enver, José Martà Pioneer Organisati ...

youth programme was also established.

Sankara launched an ambitious socioeconomic programme for change, one of the largest ever undertaken on the African continent.

His foreign policies centred on

anti-imperialism

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

, with his government rejecting all

foreign aid, pushing for

odious debt

In international law, odious debt, also known as illegitimate debt, is a legal theory that says that the national debt incurred by a despotic regime should not be enforceable. Such debts are, thus, considered by this doctrine to be personal debts ...

reduction, nationalising all land and mineral wealth and averting the power and influence of the

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster globa ...

(IMF) and

World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Interna ...

. His domestic policies included a nationwide literacy campaign, land redistribution to peasants, railway and road construction and the outlawing of

female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting, female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and female circumcision, is the ritual cutting or removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. The practice is found ...

,

forced marriage

Forced marriage is a marriage in which one or more of the parties is married without their consent or against their will. A marriage can also become a forced marriage even if both parties enter with full consent if one or both are later force ...

s and

polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

.

[Commemorating Thomas Sankara](_blank)

by Farid Omar, ''Group for Research and Initiative for the Liberation of Africa'' (GRILA), 28 November 2007

Sankara pushed for agrarian self-sufficiency and promoted public health by vaccinating 2,500,000 children against

meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

,

yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains â particularly in the back â and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

, and

measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10â12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7â10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

.

His national agenda also included planting over 10,000,000 trees to halt the growing

desertification

Desertification is a type of land degradation in drylands in which biological productivity is lost due to natural processes or induced by human activities whereby fertile areas become increasingly arid. It is the spread of arid areas caused by ...

of the

Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساØÙ ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid c ...

. Sankara called on every village to build a medical dispensary and had over 350 communities build schools with their own labour.

In the 1980s, when ecological awareness was still very low, Thomas Sankara, was one of the few African leaders to consider environmental protection a priority. He engaged in three major battles: against bush fires "which will be considered as crimes and will be punished as such"; against cattle roaming "which infringes on the rights of peoples because unattended animals destroy nature"; and against the anarchic cutting of firewood "whose profession will have to be organized and regulated". As part of a development program involving a large part of the population, ten million trees were planted in Burkina Faso in fifteen months during the revolution. To face the advancing desert and recurrent droughts, Thomas Sankara also proposed the planting of wooded strips of about fifty kilometers, crossing the country from east to west. He then thought of extending this vegetation belt to other countries. Cereal production, close to 1.1 billion tons before 1983, was predicted to rise to 1.6 billion tons in 1987. Jean Ziegler, former UN special rapporteur for the right to food, said that the country "had become food self-sufficient."

1987 coup d'état

On 15 October 1987, Sankara, along with twelve other officials, was assassinated in a coup d'état organized by Blaise Compaoré, Sankara's former colleague, who would go on to serve as Burkina Faso's president from October 1987 until October 2014. After the coup and although Sankara was known to be dead, some CDRs mounted an armed resistance to the

army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armÄre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

for several days. A majority of Burkinabè citizens hold that

France's foreign ministry, the Quai d'Orsay, was behind Compaoré in organizing the coup. There is some evidence for France's support of the coup.

Compaoré gave as one of the reasons for the coup the deterioration in relations with neighbouring countries. Compaoré argued that Sankara had jeopardised foreign relations with the former colonial power (France) and with neighbouring

Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre is ...

.

[Burkina Faso Salutes "Africa's Che" Thomas Sankara](_blank)

by Mathieu Bonkoungou, Reuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters Corporation. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency was estab ...

, 17 October 2007 Following the coup Compaoré immediately reversed the nationalizations, overturned nearly all of Sankara's policies, returned the country back into the IMF fold, and ultimately spurned most of Sankara's legacy. Following an alleged

coup-attempt in 1989, Compaoré introduced limited democratic reforms in 1990. Under the new (1991)

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

, Compaoré was

re-elected without opposition in December 1991. In 1998 Compaoré won

election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

in a landslide. In 2004, 13 people were tried for plotting a coup against President Compaoré and the coup's alleged mastermind was sentenced to life imprisonment. , Burkina Faso remained one of the

least-developed countries in the world.

Compaoré's government played the role of negotiator in several West-African disputes, including the

2010â11 Ivorian crisis, the Inter-Togolese Dialogue (2007), and the

2012 Malian Crisis.

Between February and April 2011, the death of a schoolboy provoked

protests

A protest (also called a demonstration, remonstration or remonstrance) is a public expression of objection, disapproval or dissent towards an idea or action, typically a political one.

Protests can be thought of as acts of coopera ...

throughout the country, coupled with a military mutiny and a magistrates' strike.

October 2014 protests

Starting on 28 October 2014 protesters began to march and demonstrate in Ouagadougou against President Blaise Compaoré, who appeared ready to amend the constitution and extend his 27-year rule. On 30 October some protesters set fire to the parliament building and took over the national TV headquarters.

Ouagadougou International Airport closed and MPs suspended the vote on changing the constitution (the change would have allowed Compaoré to stand for re-election in 2015). Later in the day, the military dissolved all government institutions and imposed a

curfew

A curfew is a government order specifying a time during which certain regulations apply. Typically, curfews order all people affected by them to ''not'' be in public places or on roads within a certain time frame, typically in the evening and ...

.

On 31 October 2014, President Compaoré, facing mounting pressure, resigned after 27 years in office.

Lt. Col. Isaac Zida said that he would lead the country during its transitional period before the planned

2015 presidential election, but there were concerns over his close ties to the former president. In November 2014 opposition parties,

civil-society groups and religious leaders adopted a plan for a transitional authority to guide Burkina Faso to elections. Under the plan

Michel Kafando

Michel Kafando (born 18 August 1942) is a Burkinabé diplomat who served as the transitional President of Burkina Faso from 2014 became the transitional

President of Burkina Faso

This is a list of heads of state of Burkina Faso since the Republic of Upper Volta gained independence from France in 1960 to the present day.

A total of seven people have served as head of state of Upper Volta/Burkina Faso (not counting four ...

and Lt. Col. Zida became the acting Prime Minister and Defense Minister.

2015 coup d'état

On 16 September 2015, the

Regiment of Presidential Security

The Regiment of Presidential Security (french: Régiment de la sécurité présidentielle, RSP), sometimes known as the Presidential Security Regiment, was the secret service organisation responsible for VIP security to the President of Burkina F ...

(RSP) seized the country's president and prime minister and then declared the

National Council for Democracy The National Council for Democracy (french: Conseil national pour la Démocratie), led by Chairman-General Gilbert Diendéré, was the ruling cabinet of the military junta of Burkina Faso from 17 to 23 September 2015. It took temporary control of t ...

the new national government. However, on 22 September 2015, the coup leader,

Gilbert Diendéré

Gilbert Diendéré (; born 1960) is a Burkinabé military officer and the Chairman of the National Council for Democracy, the military junta that briefly seized power in Burkina Faso in the September 2015 coup d'état. He was a long-time ai ...

, apologized and promised to restore civilian government. On 23 September 2015 the prime minister and interim president were restored to power.

November 2015 election

General elections took place in Burkina Faso on 29 November 2015.

Roch Marc Christian Kaboré

Roch Marc Christian Kaboré (; born 25 April 1957) is a Burkinabé banker and politician who served as the President of Burkina Faso from 2015 until he was deposed in 2022. He was the Prime Minister of Burkina Faso between 1994 and 1996 and Pr ...

won the election in the first round with 53.5% of the vote, defeating businessman

Zéphirin Diabré

Zéphirin Diabré (born 26 August 1959) is a Burkinabé politician. He served in the Government of Burkina Faso as Minister of Finance from 1994 to 1996.

Biography

Diabré is an economist by training and holds a doctorate in management scienc ...

, who took 29.7%.

Kaboré was sworn in as president on 29 December 2015.

November 2020 election

In 2020 general election, President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré was re-elected. However, his party Mouvement du people MPP, failed to reach absolute parliamentary majority. It secured 56 seats out of a total of 127. The Congress for Democracy and Progress (CDP), the party of former President Blaise Compaoré, was distant second with 20 seats.

Terrorist attacks

In February 2016 a terrorist attack occurred at the Splendid Hotel and Capuccino café-bar in the centre of Ouagadougou: 30 people died.

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb ( ar-at, تÙظÙÙ

اÙÙاعدة Ù٠بÙاد اÙÙ

غرب اÙإسÙاÙ

Ù, TanáºÄ«m al-QÄ'idah fÄ« BilÄd al-Maghrib al-IslÄmÄ«), or AQIM, is an Islamist militant organization (of al-Qaeda) that aims to ...

(AQIM) and

Al-Mourabitoun

The Independent Nasserite Movement â INM ( ar-at, ØرÙØ© اÙÙاصرÙÙ٠اÙÙ

ستÙÙÙÙ-اÙÙ

رابطÙÙ, translit=Harakat al-Nasiriyin al-Mustaqillin) or simply Al-Murabitoun ( lit. ''The Steadfast''), also termed variously Mouveme ...

, two groups which until then had mostly operated in neighbouring

Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, ð¤ð¤«ð¤²ð¥ð¤£ð¤¢ð¥ð¤²ð¤£ð¤ ð¤ð¤¢ð¥ð¤¤ð¤, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جÙ

ÙÙرÙØ© Ù

اÙÙ, JumhÅ«riyyÄt MÄlÄ« is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mali ...

, claimed responsibility for the attack. Since then, similar groups have carried out numerous attacks in the northern and eastern parts of the country. One terrorist attack occurred on the evening of Friday, 11 October 2019, on a mosque in the village of Salmossi near the border with Mali, leaving 16 people dead and two injured.

[

][

]

On 8 July 2020, the United States raised concerns after a

Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization, headquartered in New York City, that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. The group pressures governments, policy makers, companies, and individual human r ...

report revealed mass graves with at least 180 bodies, which were found in northern Burkina Faso where soldiers were fighting jihadists.

On 4 June 2021, the Associated Press reported that according to the government of Burkina Faso, gunmen killed at least 100 people in Solhan village in northern Burkina Faso near the Niger border. A local market and several homes were also burned down. A government spokesman blamed jihadists. This was the deadliest attack recorded in Burkina Faso since the West African country was overrun by jihadists linked to al-Qaida and the Islamic State about five years ago, said Heni Nsaibia, senior researcher at the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project.

Christians in Burkina Faso have been specifically targeted in a number of occasions. Catholic priest Joël Yougbaré was abducted in 2019 and as of November 2022 had not been heard of again, and American sister Suellen Tennyson was kidnapped in April 2022, and released in August. After a series of other attacks on Christian targets, a Burkinabé priest told Aid to the Church in Need that direct persecution of Christians was increasing in the country.

2022 coups d'état

In a successful coup on 24 January 2022, mutinying soldiers arrested and deposed President

Roch Marc Christian Kaboré

Roch Marc Christian Kaboré (; born 25 April 1957) is a Burkinabé banker and politician who served as the President of Burkina Faso from 2015 until he was deposed in 2022. He was the Prime Minister of Burkina Faso between 1994 and 1996 and Pr ...

following gunfire. The

Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration

The Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (, MPSR) has been the ruling military junta of Burkina Faso since the January 2022 Burkina Faso coup d'état. Originally it was led by Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, but he was overthrown by dis ...

(MPSR) supported by the military declared itself to be in power, led by Lieutenant Colonel

Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba

Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba (; born January 1981) is a Burkina Faso, Burkinabé military officer who served as interim president of Burkina Faso from 31 January 2022 to 30 September 2022, when he was removed in a September 2022 Burkina Faso coup d ...

. On 31 January, the military junta restored the constitution and appointed Damiba interim president. In the aftermath of the coup,

ECOWAS

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS; also known as in French and Portuguese) is a regional political and economic union of fifteen countries located in West Africa. Collectively, these countries comprise an area of , and in ...

and the

African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the Africa ...

suspended Burkina Faso's membership. On 10 February, the Constitutional Council declared Damiba president of Burkina Faso. He was sworn in as President on 16 February. On 1 March 2022, the junta approved a charter allowing a military-led transition of 3 years. The charter provides for the transition process to be followed by the holding of elections.

President Kaboré, who had been detained since the military junta took power, was released on 6 April 2022.

On 30 September, Damiba was ousted in a military coup led by Capt.

Ibrahim Traoré

Ibrahim Traoré (born 1988) is a Burkinabé military officer who has been the interim leader of Burkina Faso since the 30 September 2022 coup d'état which ousted interim president Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba. At age 34, Traoré is the world's ...

. This came eight months after Damiba seized power. The rationale given by Traore for the coup d'état was the purported inability of Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba to deal with an Islamist insurgency. Damiba resigned and left the country. On 6 October 2022, Captain Ibrahim Traore was officially appointed as president of Burkina Faso.

Apollinaire Joachim Kyélem de Tambèla

Apollinaire Joachim Kyélem de Tambèla (born 1955) is a Burkinabé lawyer, writer and statesman.

Career

On 21 October 2022, he was appointed Interim Prime Minister by Interim President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corp ...

was appointed interim Prime Minister on 21 October 2022.

Government

With French help, Blaise Compaoré seized power in a coup d'état in 1987. He overthrew his long-time friend and ally

Thomas Sankara

Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara (; 21 December 1949 â 15 October 1987) was a Burkinabé military officer, MarxistâLeninist revolutionary, and Pan-Africanist, who served as President of Burkina Faso from his coup in 1983 to his deposition a ...

, who was killed in the coup.

The

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

of 2 June 1991 established a

semi-presidential government: its parliament could be dissolved by the

President of the Republic, who was to be

elected Elected may refer to:

* "Elected" (song), by Alice Cooper, 1973

* ''Elected'' (EP), by Ayreon, 2008

*The Elected, an American indie rock band

See also

*Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population ...

for a term of seven years. In 2000, the constitution was amended to reduce the presidential term to five years and set term limits to two, preventing successive re-election. The amendment took effect during the 2005 elections. If passed beforehand, it would have prevented Compaoré from being reelected.

Other presidential candidates challenged the election results. But in October 2005, the constitutional council ruled that, because Compaoré was the sitting president in 2000, the amendment would not apply to him until the end of his second term in office. This cleared the way for his candidacy in

the 2005 election. On 13 November 2005, Compaoré was reelected in a landslide, because of a divided political opposition.

In the

2010 presidential election, President Compaoré was re-elected. Only 1.6 million Burkinabè voted, out of a total population 10 times that size.

The

2011 Burkinabè protests

The 2011 Burkina Faso protests were a series of popular protests in Burkina Faso.

Background

On 15 February, members of the military mutinied in the capital Ouagadougou over unpaid housing allowances; President Blaise Compaoré briefly fled the ...

were a series of popular protests that called for the resignation of Compaoré, democratic reforms, higher wages for troops and public servants and economic freedom. As a result, governors were replaced and wages for public servants were raised.

The parliament consisted of

one chamber known as the

National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

, which had 111 seats with members elected to serve five-year terms. There was also a constitutional chamber, composed of ten members, and an economic and social council whose roles were purely consultative. The 1991 constitution created a

bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single grou ...

parliament, but the upper house (Chamber of Representatives) was abolished in 2002.

The Compaoré administration had worked to

decentralize power by devolving some of its powers to regions and municipal authorities. But the widespread distrust of politicians and lack of political involvement by many residents complicated this process. Critics described this as a hybrid decentralisation.

Political freedoms are severely restricted in Burkina Faso.

Human rights organizations

:''The list is incomplete; please add known articles or create missing ones''

The following is a list of articles on the human rights organisations of the world. It does not include political parties, or academic institutions. The list includes ...

had criticised the Compaoré administration for numerous acts of state-sponsored violence against journalists and other politically active members of society.

In mid-September 2015 the Kafando government, along with the rest of the post-October 2014 political order, was

temporarily overthrown in a coup attempt by the

Regiment of Presidential Security

The Regiment of Presidential Security (french: Régiment de la sécurité présidentielle, RSP), sometimes known as the Presidential Security Regiment, was the secret service organisation responsible for VIP security to the President of Burkina F ...

(RSP). They installed Gilbert Diendéré as chairman of the new

National Council for Democracy The National Council for Democracy (french: Conseil national pour la Démocratie), led by Chairman-General Gilbert Diendéré, was the ruling cabinet of the military junta of Burkina Faso from 17 to 23 September 2015. It took temporary control of t ...

.

On 23 September 2015, the prime minister and interim president were restored to power.

The

national elections were subsequently rescheduled for 29 November.

Kaboré won the election in the first round of voting, receiving 53.5% of the vote against 29.7% for the second place candidate,

Zephirin Diabré.

[Mathieu Bonkoungou and Nadoun Coulibaly]

"Kabore wins Burkina Faso presidential election"

Reuters, 1 December 2015. He was sworn in as president on 29 December 2015.

Agence France-Presse, 29 December 2015. The

BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...

described the president as a "French-educated banker ...

sees himself as a social democrat, and has pledged to reduce youth unemployment, improve education and healthcare, and make health provision for children under six free of charge".

The prime minister is head of government and is appointed by the president with the approval of the National Assembly. He is responsible for recommending a cabinet for appointment by the president. Paul Kaba Thieba was appointed PM in early 2016.

According to a World Bank Report in late 2018, the political climate was stable; the government was facing "social discontent marked by major strikes and protests, organized by unions in several economic sectors, to demand salary increases and social benefits .... and increasingly frequent jihadist attacks". In the

, Kaboré and the MPP were reelected with 57.7% of the vote.

In 2015, Kaboré promised to revise the 1991 constitution. The revision was completed in 2018. One condition prevents any individual from serving as president for more than ten years either consecutively or intermittently and provides a method for impeaching a president. A referendum on the constitution for the Fifth Republic was scheduled for 24 March 2019.

Certain rights are also enshrined in the revised wording: access to drinking water, access to decent housing and a recognition of the right to civil disobedience, for example. The referendum was required because the opposition parties in Parliament refused to sanction the proposed text.

, and United Nations. It is currently suspended from

.

consists of some 6,000 men in voluntary service, augmented by a part-time national People's Militia composed of civilians between 25 and 35 years of age who are trained in both military and civil duties. According to ''Jane's Sentinel Country Risk Assessment'', Burkina Faso's Army is undermanned for its force structure and poorly equipped, but has wheeled light-armour vehicles, and may have developed useful combat expertise through interventions in Liberia and elsewhere in Africa.

In terms of training and equipment, the regular Army is believed to be neglected in relation to the élite Regiment of Presidential Security (french: link=no, Régiment de la Sécurité Présidentielle â RSP). Reports have emerged in recent years of disputes over pay and conditions. There is an air force with some 19 operational aircraft, but no navy, as the country is landlocked. Military expenses constitute approximately 1.2% of the nation's GDP.

In April 2011, there was an

.

Burkina Faso employs numerous police and security forces, generally modeled after organizations used by

. France continues to provide significant support and training to police forces. The ''Gendarmerie Nationale'' is organized along military lines, with most police services delivered at the brigade level. The

operates under the authority of the Minister of Defence, and its members are employed chiefly in the rural areas and along borders.

; a national police force controlled by the Ministry of Security; and an autonomous

(''Régiment de la Sécurité Présidentielle'', or RSP), a 'palace guard' devoted to the protection of the President of the Republic. Both the gendarmerie and the national police are subdivided into both administrative and judicial police functions; the former are detailed to protect public order and provide security, the latter are charged with criminal investigations.

All foreigners and citizens are required to carry photo ID passports, or other forms of identification or risk a fine, and police spot identity checks are commonplace for persons traveling by auto,

, or bus.

. These regions encompass

. Each region is administered by a governor.

.

It is made up of two major types of countryside. The larger part of the country is covered by a

, which forms a gently undulating landscape with, in some areas, a few isolated hills, the last vestiges of a

. The southwest of the country, on the other hand, forms a

, is found at an elevation of . The massif is bordered by sheer cliffs up to high. The average altitude of Burkina Faso is and the difference between the highest and lowest terrain is no greater than . Burkina Faso is therefore a relatively flat country.

The country owes its former name of Upper Volta to three rivers which cross it: the

(''Nazinon''). The Black Volta is one of the country's only two rivers which flow year-round, the other being the

, which flows to the southwest. The basin of the

and flow for only four to six months a year. They still can flood and overflow, however. The country also contains numerous lakes â the principal ones are Tingrela,

, and Dem. The country contains large ponds, as well, such as Oursi, Béli, Yomboli, and Markoye.

are often a problem, especially in the north of the country.

.

Burkina Faso has a primarily tropical climate with two very distinct seasons. In the rainy season, the country receives between of rainfall; in the dry season, the

â a hot dry wind from the Sahara â blows. The rainy season lasts approximately four months, May/June to September, and is shorter in the north of the country. Three climatic zones can be defined: the Sahel, the Sudan-Sahel, and the Sudan-Guinea. The

to the south. Situated between 11° 3Ⲡand 13° 5Ⲡnorth

, the Sudan-Sahel region is a transitional zone with regards to rainfall and temperature. Further to the south, the Sudan-Guinea zone receives more than

During the

During the  The eastern and western regions, where a standoff against the forces of the powerful ruler

The eastern and western regions, where a standoff against the forces of the powerful ruler

With French help, Blaise Compaoré seized power in a coup d'état in 1987. He overthrew his long-time friend and ally

With French help, Blaise Compaoré seized power in a coup d'état in 1987. He overthrew his long-time friend and ally

Burkina Faso lies mostly between latitudes 9° and 15° N (a small area is north of 15°), and longitudes 6° W and 3° E.

It is made up of two major types of countryside. The larger part of the country is covered by a

Burkina Faso lies mostly between latitudes 9° and 15° N (a small area is north of 15°), and longitudes 6° W and 3° E.

It is made up of two major types of countryside. The larger part of the country is covered by a  Geographic and environmental causes can also play a significant role in contributing to Burkina Faso's food insecurity. As the country is situated in the

Geographic and environmental causes can also play a significant role in contributing to Burkina Faso's food insecurity. As the country is situated in the  In 2018, tourism was almost non-existent in large parts of the country. The U.S. government (and others) warn their citizens not to travel into large parts of Burkina Faso: "The northern Sahel border region shared with Mali and Niger due to crime and terrorism. The provinces of Kmoandjari, Tapoa, Kompienga, and Gourma in East Region due to crime and terrorism".