British regalia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, originally the Crown Jewels of England, are a collection of royal ceremonial objects kept in the

By the early 5th century, the Romans had withdrawn from Britain, and the

By the early 5th century, the Romans had withdrawn from Britain, and the

In 1161, Edward the Confessor was made a saint, and objects connected with his reign became holy relics. The monks at his burial place of

In 1161, Edward the Confessor was made a saint, and objects connected with his reign became holy relics. The monks at his burial place of

The transferring of crowns symbolised the transfer of power between rulers. Following the defeat in 1282 of the Welsh prince Llewelyn ap Gruffydd by Edward I (), the Welsh regalia, including the crown of the legendary

The transferring of crowns symbolised the transfer of power between rulers. Following the defeat in 1282 of the Welsh prince Llewelyn ap Gruffydd by Edward I (), the Welsh regalia, including the crown of the legendary

An emerging item of regalia was the orb, described in Tudor inventories as a gold ball with a cross,Keay (2011), p. 32. which underlined the monarch's sovereignty. Orbs had been pictorial emblems of royal authority in England since the early Middle Ages, but a real orb was probably not used at any English coronation until Henry VIII (). State regalia increasingly passed from one monarch to the next. The best example of this was the imperial state

An emerging item of regalia was the orb, described in Tudor inventories as a gold ball with a cross,Keay (2011), p. 32. which underlined the monarch's sovereignty. Orbs had been pictorial emblems of royal authority in England since the early Middle Ages, but a real orb was probably not used at any English coronation until Henry VIII (). State regalia increasingly passed from one monarch to the next. The best example of this was the imperial state

In 1669, the Jewels went on public display for the first time in the Jewel House at the Tower of London. The Deputy

In 1669, the Jewels went on public display for the first time in the Jewel House at the Tower of London. The Deputy

A much lighter crown is worn by the monarch when leaving Westminster Abbey, and at the annual State Opening of Parliament.Mears, et al., p. 29. The current

A much lighter crown is worn by the monarch when leaving Westminster Abbey, and at the annual State Opening of Parliament.Mears, et al., p. 29. The current

Thus began a tradition of each queen consort having a crown made specially for their use. In 1902 the

Thus began a tradition of each queen consort having a crown made specially for their use. In 1902 the

A relatively modest gold

A relatively modest gold

The swords of state reflect a monarch's role as

The swords of state reflect a monarch's role as

The Crown Jewels include 16 silver trumpets dating from between 1780 and 1848. Nine are draped with red silk

The Crown Jewels include 16 silver trumpets dating from between 1780 and 1848. Nine are draped with red silk

The Ampulla, tall and weighing , is a hollow gold vessel made in 1661 and shaped like an eagle with outspread wings. Its head unscrews, enabling the vessel to be filled with oil, which exits via a hole in the beak. The original ampulla was a small stone phial, sometimes worn around the neck as a pendant by kings, and otherwise kept inside an eagle-shaped golden reliquary.Rose, pp. 95–98. According to 14th-century legend, the

The Ampulla, tall and weighing , is a hollow gold vessel made in 1661 and shaped like an eagle with outspread wings. Its head unscrews, enabling the vessel to be filled with oil, which exits via a hole in the beak. The original ampulla was a small stone phial, sometimes worn around the neck as a pendant by kings, and otherwise kept inside an eagle-shaped golden reliquary.Rose, pp. 95–98. According to 14th-century legend, the

All the robes have priestly connotations and their form has changed little since the Middle Ages. A tradition of wearing St Edward's robes came to an end in 1547 after the

All the robes have priestly connotations and their form has changed little since the Middle Ages. A tradition of wearing St Edward's robes came to an end in 1547 after the

An orb, a type of globus cruciger, was first used at an English coronation by Henry VIII in 1509, and then by all subsequent monarchs apart from the early Stuart kings James I and Charles I, who opted for the medieval coronation order. The Tudor orb was deposited with St Edward's regalia at Westminster Abbey in 1625.Rose, p. 45. Since 1661 the Sovereign's Orb is a hollow gold sphere about in diameter and weighing (more than twice as heavy as the original) made for Charles II.Mears, et al., p. 19. A band of gems and pearls runs along the equator and there is a half-band on the top hemisphere. Atop the orb is an amethyst surmounted by a jewelled cross, symbolising the Christian world, with a sapphire on one side and an emerald on the other. Altogether, the orb is decorated with 375 pearls, 365 diamonds, 18 rubies, 9 emeralds, 9 sapphires, 1 amethyst and 1 piece of glass.Rose, p. 42. It is handed to the sovereign during the investiture rite of the coronation, and is borne later in the left hand when leaving Westminster Abbey. A small version, originally set with hired gems, was made in 1689 for Mary II to hold at her joint coronation with William III; it was never used again at a coronation and is now set with imitation gems and cultured pearls. The orb is in diameter and weighs . Both orbs were laid on Queen Victoria's coffin at her state funeral in 1901. Officially, no reason was given for using Mary II's orb, but it may have been intended to reflect Victoria's position as

An orb, a type of globus cruciger, was first used at an English coronation by Henry VIII in 1509, and then by all subsequent monarchs apart from the early Stuart kings James I and Charles I, who opted for the medieval coronation order. The Tudor orb was deposited with St Edward's regalia at Westminster Abbey in 1625.Rose, p. 45. Since 1661 the Sovereign's Orb is a hollow gold sphere about in diameter and weighing (more than twice as heavy as the original) made for Charles II.Mears, et al., p. 19. A band of gems and pearls runs along the equator and there is a half-band on the top hemisphere. Atop the orb is an amethyst surmounted by a jewelled cross, symbolising the Christian world, with a sapphire on one side and an emerald on the other. Altogether, the orb is decorated with 375 pearls, 365 diamonds, 18 rubies, 9 emeralds, 9 sapphires, 1 amethyst and 1 piece of glass.Rose, p. 42. It is handed to the sovereign during the investiture rite of the coronation, and is borne later in the left hand when leaving Westminster Abbey. A small version, originally set with hired gems, was made in 1689 for Mary II to hold at her joint coronation with William III; it was never used again at a coronation and is now set with imitation gems and cultured pearls. The orb is in diameter and weighs . Both orbs were laid on Queen Victoria's coffin at her state funeral in 1901. Officially, no reason was given for using Mary II's orb, but it may have been intended to reflect Victoria's position as

The

The

In the Jewel House there is a collection of

In the Jewel House there is a collection of

The last

The last

Three silver-gilt objects (comprising a total of six parts) associated with royal christenings are displayed in the Jewel House. Charles II's tall font was created in 1661 and stood on a basin to catch any spills. Surmounting the font's domed lid is a figure of

Three silver-gilt objects (comprising a total of six parts) associated with royal christenings are displayed in the Jewel House. Charles II's tall font was created in 1661 and stood on a basin to catch any spills. Surmounting the font's domed lid is a figure of

Royal Collection TrustThe Crown Jewels

at Historic Royal Palaces

The Crown Jewels

at the website of the British royal family Videos:

Royal Regalia

from '' The Coronation'' (2018) with commentary by

''The Crown Jewels'' (1967)

by British Pathé

''The Crown Jewels'' (1937)

by British Pathé {{DEFAULTSORT:Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

which include the coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

regalia and vestments worn by British monarchs

There have been 13 British monarchs since the political union of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland on 1 May 1707. England and Scotland had been in personal union since 24 March 1603. On 1 January 1801, the Kingdom of Great Brit ...

.

Symbols of over 800 years of monarchy, the coronation regalia are the only working set in Europe and the collection is the most historically complete of any regalia in the world. Objects used to invest and crown British monarchs variously denote their role as head of state of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

and other countries of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

, Supreme Governor of the Church of England

The supreme governor of the Church of England is the titular head of the Church of England, a position which is vested in the British monarch. Queen and Church > Queen and Church of England">The Monarchy Today > Queen and State > Queen and Chur ...

, and head of the British armed forces. They feature heraldic devices and national emblems of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Use of regalia by monarchs in England can be traced back to when it was converted to Christianity in the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

. A permanent set of coronation regalia, once belonging to Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æt ...

, was established after he was made a saint in the 12th century. These holy relics were kept at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, the venue of coronations since 1066, and another set of regalia was reserved for religious feasts and State Openings of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes a speech from the throne known as the King's (or Queen's) Speech. The event takes place ...

. Collectively, these objects came to be known as the Jewels of the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

. Most of the present collection dates from around 350 years ago when Charles II ascended the throne. The medieval and Tudor regalia had been sold or melted down after the monarchy was abolished in 1649 during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

. Only four original items predate the Restoration: a late 12th-century anointing spoon (the oldest object) and three early 17th-century swords. The regalia continued to be used by British monarchs after the kingdoms of England and Scotland merged in 1707.

The regalia contain 23,578 gemstones, among them Cullinan I (), the largest clear cut diamond in the world, set in the Sovereign's Sceptre with Cross. It was cut from the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found, the eponymous Cullinan, discovered in South Africa in 1905 and presented to Edward VII. On the Imperial State Crown

The Imperial State Crown is one of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom and symbolises the sovereignty of the monarch.

It has existed in various forms since the 15th century. The current version was made in 1937 and is worn by the monarc ...

are Cullinan II

The Cullinan Diamond is the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found,Scarratt and Shor, p. 120. weighing (1 lb 5.92 oz), discovered at the Premier No.2 mine in Cullinan, South Africa, on 26 January 1905. It was named after Thomas Cull ...

(), the Stuart Sapphire

The Stuart Sapphire is a blue sapphire that forms part of the British Crown Jewels. It weighs 104 carats (20.8 grams) and is believed to have originated from Asia, potentially present-day Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar or Kashmir.

Beginning

T ...

, St Edward's Sapphire, and the Black Prince's Ruby

The Black Prince's Ruby is a large, irregular cabochon red spinel weighing set in the cross pattée above the Cullinan II diamond at the front of the Imperial State Crown of the United Kingdom. The spinel is one of the oldest parts of the Crow ...

– a large red spinel. The Koh-i-Noor

The Koh-i-Noor ( ; from ), also spelled Kohinoor and Koh-i-Nur, is one of the largest cut diamonds in the world, weighing . It is part of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom. The diamond is currently set in the Crown of Queen Elizabeth The ...

diamond () was acquired by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

from India and has been featured on three consort crowns. A small number of historical objects at the Tower are either empty or set with glass and crystal replicas.

At a coronation, the monarch is anointed using holy oil poured from an ampulla

An ampulla (; ) was, in Ancient Rome, a small round vessel, usually made of glass and with two handles, used for sacred purposes. The word is used of these in archaeology, and of later flasks, often handle-less and much flatter, for holy water or ...

into the spoon, invested with robes and ornaments, and crowned with St Edward's Crown

St Edward's Crown is the centrepiece of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom. Named after Saint Edward the Confessor, versions of it have traditionally been used to crown English and British monarchs at their coronations since the 13th cent ...

. Afterwards, it is exchanged for the lighter Imperial State Crown, which is also usually worn at State Openings of Parliament. Wives of kings are invested with a plainer set of regalia, and since 1831, a new crown has been made specially for each queen consort. Also regarded as crown jewels are state swords, trumpets, ceremonial maces, church plate, historical regalia, banqueting plate, and royal christening fonts. They are part of the Royal Collection

The Royal Collection of the British royal family is the largest private art collection in the world.

Spread among 13 occupied and historic royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King Charles III and overseen by the ...

and belong to the institution of monarchy, passing from one sovereign to the next. When not in use, the Jewels are on public display in the Jewel House and Martin Tower, where they are seen by 2.5 million visitors every year.

History

Prehistory and Romans

The earliest known use of a crown in Britain was discovered by archaeologists in 1988 inDeal

A deal, or deals may refer to:

Places United States

* Deal, New Jersey, a borough

* Deal, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* Deal Lake, New Jersey

Elsewhere

* Deal Island (Tasmania), Australia

* Deal, Kent, a town in England

* Deal, a ...

, Kent, and dates to between 200 and 150 BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

. A sword, brooch, ceremonial shield, and decorated bronze crown with a single arch, which sat directly on the head of its wearer, were found inside the tomb of the Mill Hill Warrior. At this point, crowns were symbols of authority worn by religious and military leaders. Priests continued to use crowns following the Roman conquest of Britain

The Roman conquest of Britain refers to the conquest of the island of Britain by occupying Roman forces. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the southern half of Britain by 87 when the Stan ...

in 43 CE. A dig in a field at Hockwold cum Wilton, Norfolk, in the 1950s revealed a bronze crown with two arches and depictions of male faces, as well as two bronze diadem

A diadem is a type of crown, specifically an ornamental headband worn by monarchs and others as a badge of royalty.

Overview

The word derives from the Greek διάδημα ''diádēma'', "band" or "fillet", from διαδέω ''diadéō'', " ...

s with an adjustable headband and '' repoussé'' silver embellishments, dating from the Roman period. One diadem features a plaque in the centre depicting a man holding a sphere and an object similar to a shepherd's crook, analogues of the orb and sceptre that evolved later as royal ornaments.Twining, pp. 100–102.

Anglo-Saxons

By the early 5th century, the Romans had withdrawn from Britain, and the

By the early 5th century, the Romans had withdrawn from Britain, and the Angles

The Angles ( ang, Ængle, ; la, Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who settled in Great Britain in the post-Roman period. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. Their name is the root of the name ...

and the Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

settled. A heptarchy

The Heptarchy were the seven petty kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England that flourished from the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th century until they were consolidated in the 8th century into the four kingdoms of Mercia, Northumbria, Wess ...

of new kingdoms began to emerge. One method used by regional kings to solidify their authority was the use of ceremony and insignia. The tomb of an unknown king – evidence suggests it may be Rædwald of East Anglia

Rædwald ( ang, Rædwald, ; 'power in counsel'), also written as Raedwald or Redwald (), was a king of East Anglia, an Anglo-Saxon kingdom which included the present-day English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. He was the son of Tytila of East ...

() – at Sutton Hoo

Sutton Hoo is the site of two early medieval cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near the English town of Woodbridge. Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when a previously undisturbed ship burial containing ...

provides insight into the regalia of a pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon monarch.Barker, pp. 25–29. Inside the early 7th-century tomb, discovered in 1939, was found the ornate Sutton Hoo helmet

The Sutton Hoo helmet is a decorated Anglo-Saxon helmet found during a 1939 excavation of the Sutton Hoo Ship burial, ship-burial. It was buried around 625 and is widely associated with King Rædwald of East Anglia; its elaborate decoration ma ...

, consisting of an iron cap, a neck guard, and a face mask decorated with copper alloy images of animals and warriors set with garnet

Garnets () are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

All species of garnets possess similar physical properties and crystal forms, but differ in chemical composition. The different ...

s. He was also buried with a decorated sword; a ceremonial shield; and a heavy whetstone sceptre, on top of which is an iron ring surmounted by the figure of a stag.

In 597 CE, a Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

monk was sent by Pope Gregory I to start converting Pagan England to Christianity. The monk, Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

, became the first Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

. Within two centuries, the ritual of anointing monarchs with holy oil and crowning them (initially with helmets) in a Christian ceremony had been established, and regalia took on a religious identity. There was still no permanent set of coronation regalia; each monarch generally had a new set made, with which they were buried upon death. In 9th-century Europe, gold crowns in the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

tradition were replacing bronze, and gold soon became the standard material for English royal crowns.

King Æthelstan

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ti ...

() united the various Anglo-Saxon realms to form the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

. In the earliest known depiction of an English king wearing a crown he is shown presenting a copy of Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

's ''Life of St Cuthbert

Cuthbert of Lindisfarne ( – 20 March 687) was an Anglo-Saxon saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in the Kingdom of Nor ...

'' to the saint himself. Until his reign, kings were portrayed on coins wearing helmets and circlets,Steane, p. 31. or wreath-like diadems in the style of Roman emperor Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

. Whether they actually wore such an item is not known. Edgar the Peaceful

Edgar ( ang, Ēadgār ; 8 July 975), known as the Peaceful or the Peaceable, was King of the English from 959 until his death in 975. The younger son of King Edmund I and Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury, he came to the throne as a teenager followin ...

() was the first English king to be crowned with an actual crown, and a sceptre was also introduced for his coronation.Twining, p. 103. After crowns, sceptres were the most potent symbols of royal authority in medieval England.

Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æt ...

() is depicted on a throne and wearing a crown and holding a sceptre in the first scene of the Bayeux Tapestry. Edward died without an heir, and William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 10 ...

emerged as the first Norman king of England following his victory over the English at the Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings nrf, Batâle dé Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, the Duke of Normandy, and an English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conque ...

. Wearing a crown became an important part of William I's efforts to assert authority over his new territory and subjects.Keay (2011), pp. 18–20. At his death in 1087, the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

'' reported: " illiamkept great state … He wore his crown three times a year as often as he was in England … He was so stern and relentless … we must not forget the good order he kept in the land". Those crown-wearings were held on the religious festivals of Easter, Whitsun

Whitsun (also Whitsunday or Whit Sunday) is the name used in Britain, and other countries among Anglicans and Methodists, for the Christian High Holy Day of Pentecost. It is the seventh Sunday after Easter, which commemorates the descent of the ...

, and Christmas.

In 1161, Edward the Confessor was made a saint, and objects connected with his reign became holy relics. The monks at his burial place of

In 1161, Edward the Confessor was made a saint, and objects connected with his reign became holy relics. The monks at his burial place of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

claimed that Edward had asked them to look after his regalia in perpetuity and that they were to be used at the coronations of all future kings. A note to this effect is contained in an inventory of precious relics drawn up by a monk at the abbey in 1450, recording a tunicle

The tunicle is a liturgical vestment associated with Roman Catholicism, Anglicanism, and Lutheranism.

Contemporary use

For a description of the tunicle, see dalmatic, the vestment with which it became identical in form, although earlier editions ...

, dalmatic

The dalmatic is a long, wide-sleeved tunic, which serves as a liturgical vestment in the Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican, United Methodist, and some other churches. When used, it is the proper vestment of a deacon at Mass, Holy Communion or ot ...

, pallium

The pallium (derived from the Roman ''pallium'' or ''palla'', a woolen cloak; : ''pallia'') is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the pope, but for many centuries bestowed by the Holy See upon metropol ...

, and other vestments; a gold sceptre, two rods, a gold crown, comb, and spoon; a crown and two rods for the queen's coronation; and a chalice

A chalice (from Latin 'mug', borrowed from Ancient Greek () 'cup') or goblet is a footed cup intended to hold a drink. In religious practice, a chalice is often used for drinking during a ceremony or may carry a certain symbolic meaning.

R ...

of onyx

Onyx primarily refers to the parallel banded variety of chalcedony, a silicate mineral. Agate and onyx are both varieties of layered chalcedony that differ only in the form of the bands: agate has curved bands and onyx has parallel bands. The ...

stone and a paten

A paten or diskos is a small plate, used during the Mass. It is generally used during the liturgy itself, while the reserved sacrament are stored in the tabernacle in a ciborium.

Western usage

In many Western liturgical denominations, the ...

made of gold for the Holy Communion

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instituted ...

. Although the Abbey's claim is likely to have been an exercise in self-promotion, and some of the regalia had probably been taken from Edward's grave when he was reinterred there, it became accepted as fact, thereby establishing the first known set of hereditary coronation regalia in Europe. Westminster Abbey is owned by a monarch, and the regalia had always been royal property – the abbots were mere custodians. In the following centuries, some of these objects would fall out of use and the regalia would expand to include many others used or worn by monarchs and queens consort at coronations.

A crown referred to as "St Edward's Crown

St Edward's Crown is the centrepiece of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom. Named after Saint Edward the Confessor, versions of it have traditionally been used to crown English and British monarchs at their coronations since the 13th cent ...

" is first recorded as having been used for the coronation of Henry III () and appears to be the same crown worn by Edward. Being crowned and invested with regalia owned by a previous monarch who was also a saint reinforced the king's authority.Rose, p. 14. It was also wrongly thought to have been originally owned by Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bo ...

() because an inscription on the lid of its box, translated from Latin, read: "This is the chief crown of the two, with which were crowned Kings Alfred, Edward and others". The crown would be used in many subsequent coronations until its eventual destruction 400 years later. Few descriptions survive, although one 17th century historian noted that it was "ancient Work with Flowers, adorn'd with Stones of somewhat a plain setting", and an inventory described it as "gold wire-work set with slight stones and two little bells", weighing . It had arches and may have been decorated with filigree

Filigree (also less commonly spelled ''filagree'', and formerly written ''filigrann'' or ''filigrene'') is a form of intricate metalwork used in jewellery and other small forms of metalwork.

In jewellery, it is usually of gold and silver ...

and cloisonné

Cloisonné () is an ancient technique for decorating metalwork objects with colored material held in place or separated by metal strips or wire, normally of gold. In recent centuries, vitreous enamel has been used, but inlays of cut gemstones, ...

enamels. Also in the Royal Collection in this period was an item called a state crown

A state crown is the working crown worn or used by a monarch on recurring state occasions such as when opening Parliament in Britain, as opposed to the coronation crown with which they would be formally crowned.

Some state crowns might however b ...

. Together with other crowns, rings, and swords, it constituted the monarch's state regalia that were kept separate from the coronation regalia, mostly at the royal palaces.

Late medieval period

The transferring of crowns symbolised the transfer of power between rulers. Following the defeat in 1282 of the Welsh prince Llewelyn ap Gruffydd by Edward I (), the Welsh regalia, including the crown of the legendary

The transferring of crowns symbolised the transfer of power between rulers. Following the defeat in 1282 of the Welsh prince Llewelyn ap Gruffydd by Edward I (), the Welsh regalia, including the crown of the legendary King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as ...

, were surrendered to England. According to the ''Chronicle of Aberconwy Abbey

Aberconwy Abbey was a Cistercian foundation at Conwy, later transferred to Maenan near Llanrwst, and in the 13th century was the most important abbey in the north of Wales.

A Cistercian house was founded at Rhedynog Felen near Caernarfon in ...

'', "and so the glory of Wales and the Welsh was handed over to the kings of England". After the invasion of Scotland in 1296, the Stone of Scone

The Stone of Scone (; gd, An Lia Fàil; sco, Stane o Scuin)—also known as the Stone of Destiny, and often referred to in England as The Coronation Stone—is an oblong block of red sandstone that has been used for centuries in the coronati ...

was sent to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

"in recognition", as the chronicler Walter of Guisborough put it, "of a kingdom surrendered and conquered". It was fitted into a wooden chair, which came to be used for the investiture of kings of England, earning its reputation as the Coronation Chair

The Coronation Chair, known historically as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by ...

. The Scottish regalia were also taken to London and offered at the shrine of Edward the Confessor; Scotland eventually regained its independence. In the treasury of Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to th ...

() there were no fewer than 10 crowns. When Richard II () was forced to abdicate, he symbolically handed St Edward's Crown over to his successor with the words "I present and give to you this crown … and all the rights dependent on it".

Monarchs often pledged items of state regalia as collateral for loans. Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ro ...

() pawned his ''magna corona'' to Baldwin of Luxembourg

Baldwin of Luxembourg (c. 1285 – 21 January 1354) was the Archbishop- Elector of Trier and Archchancellor of Burgundy from 1307 to his death. From 1328 to 1336, he was the diocesan administrator of the archdiocese of Mainz and from 1331 to 1 ...

in 1339 for more than £16,650, equal to £ . Three crowns and other jewels were held by the Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

and the Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and is used (along with the Earl of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title. The ...

in the 1370s as security for £10,000.Steane, p. 35. One crown was exchanged with the Corporation of London

The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the municipal governing body of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United Ki ...

in 1386 for a £4,000 loan. Mayors, knights, peers, bankers, and other wealthy subjects sometimes released objects on a temporary basis for the royal family to use at state occasions. Monarchs also distributed plate and jewels to troops in lieu of money.Collins, p. 75. At some point in the 14th century, all of the state regalia were moved to the White Tower at the Tower of London owing to a series of successful and attempted thefts in Westminster Abbey. The holy relics of the coronation regalia stayed behind intact at the Abbey. Two arches topped with a monde

A ''monde'', meaning 'world' in French, is an orb located near the top of a crown. It represents, as the name suggests, the world that the monarch rules. It is the point at which a crown's half arches meet. It is usually topped off either w ...

and cross appear on the state crown during the reign of Henry V (), though arches did not feature on the Great Seal until 1471.Collins, p. 11. Known as a closed or imperial crown, the arches and cross symbolised the king's pretensions of being an emperor of his own domain, subservient to no one but God, unlike some continental rulers who owed fealty to more powerful kings or the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

.

Tudors and early Stuarts

The traditions established in the medieval period continued later. By the mid 15th century, a crown was formally worn on six religious feasts every year: Christmas, Epiphany, Easter, Whitsun,All Saints' Day

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the church, whether they are k ...

, and one or both feasts of St Edward. A crown was displayed and worn at the annual State Opening of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes a speech from the throne known as the King's (or Queen's) Speech. The event takes plac ...

. Also around this time, three swords – symbols of kingship since ancient times – were being used in the coronation ceremony to represent the king's powers in the administration of justice: the Sword of Spiritual Justice, the Sword of Temporal Justice, and the blunt Sword of Mercy

Curtana, also known as the Sword of Mercy, is a ceremonial sword used at the coronation of British kings and queens. One of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom, its end is blunt and squared to symbolise mercy.

Description

The sword meas ...

.Keay (2011), p. 30.

An emerging item of regalia was the orb, described in Tudor inventories as a gold ball with a cross,Keay (2011), p. 32. which underlined the monarch's sovereignty. Orbs had been pictorial emblems of royal authority in England since the early Middle Ages, but a real orb was probably not used at any English coronation until Henry VIII (). State regalia increasingly passed from one monarch to the next. The best example of this was the imperial state

An emerging item of regalia was the orb, described in Tudor inventories as a gold ball with a cross,Keay (2011), p. 32. which underlined the monarch's sovereignty. Orbs had been pictorial emblems of royal authority in England since the early Middle Ages, but a real orb was probably not used at any English coronation until Henry VIII (). State regalia increasingly passed from one monarch to the next. The best example of this was the imperial state Tudor Crown

The Tudor Crown, also known as Henry VIII's Crown, was the imperial crown, imperial and state crown of Kingdom of England, English monarchs from around the time of Henry VIII until it was destroyed during the English Civil War, Civil War in 16 ...

, which was probably created at the beginning of the Tudor dynasty. It first appears in a royal inventory during Henry VIII's reign and was one of three used to crown each of his next three successors, the others being St Edward's Crown and a personal crown. After the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

, when England broke away from the authority of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

denounced the veneration of medieval relics and downplayed the history of St Edward's regalia.Ronald Lightbown

Ronald Lightbown (1932–2021) was a noted British art historian and curator, specializing in Renaissance art. He wrote large monographs on the painters Sandro Botticelli and Carlo Crivelli. After a degree from the University of Cambridge

, m ...

in MacGregor, "The King's Regalia, Insignia and Jewellery", p. 257.

The concept of hereditary state regalia was enshrined in English law in 1606 when James I (), the first Stuart king to rule England, decreed a list of "Roiall and Princely ornaments and Jewells to be indyvidually and inseparably for ever hereafter annexed to the Kingdome of this Realme". After James died, his son, Charles I () ascended the throne. Desperate for money, one of his first acts was to load 41 masterpieces from the Jewel House onto a ship bound for Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

– the hub of Europe's jewel trade. This hoard of unique treasures, including the Mirror of Great Britain

The Mirror of Great Britain was a piece of jewellery that was part of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom during the reign of King James VI and I. It was pawned in 1625 and is considered lost.

Description

The jewel was described in a 1606 inv ...

brooch, a 14th-century pendant called the Three Brothers, a gold salt cellar known as the Morris Dance, and much fine Elizabethan plate, was expected to swell the king's coffers by £300,000, but fetched only £70,000.

Charles's many conflicts with Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, stemming from his belief in the divine right of kings

In European Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representin ...

and the many religious conflicts that pervaded his reign, triggered the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

in 1642. Parliament deemed the regalia as "Jewels of the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

": their ownership was vested in the monarch by virtue of his public role as king and not owned by him personally. To avoid putting his subjects at legal risk, Charles asked his wife Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria (french: link=no, Henriette Marie; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. She was ...

to smuggle the inalienable property of the Crown abroad and sell it on the Dutch jewellery market. Upon learning of the scheme, the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

and House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

both declared anyone involved in trafficking the Crown Jewels to be an enemy of the state. Henrietta succeeded in disposing of a small quantity of jewels, albeit at a heavy discount, and shipped guns and ammunition back to England for the royalist cause. Two years later, Parliament seized of rare silver-gilt pieces from the Jewel House and used the proceeds to bankroll its own side of the war.

Interregnum

After six years of war, Charles was defeated and executed, and less than a week later, theRump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"R ...

voted to abolish the monarchy. The newly created English Commonwealth

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execu ...

found itself short of money. To raise funds, the Act for the Sale of the Goods and Personal Estate of the Late King, Queen and Prince was brought into law, and trustees were appointed to value the Jewels – then regarded by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

as "symbolic of the detestable rule of kings"Mears, et al., p. 6. and "monuments of superstition and idolatry" – and sell them to the highest bidder. The most valuable object was Henry VIII's Crown, valued at £1,100. Their gemstones and pearls removed, most of the coronation and state regalia were melted down, and the gold was struck into coins by the Mint.

Two nuptial crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

s survived: the Crown of Margaret of York

Margaret of York (3 May 1446 – 23 November 1503)—also by marriage known as Margaret of Burgundy—was Duchess of Burgundy as the third wife of Charles the Bold and acted as a protector of the Burgundian State after his death. She was a daugh ...

and the Crown of Princess Blanche

The Crown of Princess Blanche, also called the Palatine Crown or Bohemian Crown, is the oldest surviving royal crown known to have been in England, and probably dates to 1370–80.

It is made of gold with diamonds, rubies, emeralds, sapphire ...

had been taken out of England centuries before the Civil War when Margaret and Blanche married kings in continental Europe. Both crowns and the 9th-century Alfred Jewel

The Alfred Jewel is a piece of Anglo-Saxon goldsmithing work made of enamel and quartz enclosed in gold. It was discovered in 1693, in North Petherton, Somerset, England and is now one of the most popular exhibits at the Ashmolean Museum in Ox ...

give a sense of the character of royal jewellery in England in the Middle Ages. Another rare survivor is the 600-year-old Crystal Sceptre, a gift from Henry V to the Lord Mayor of London, who still bears it at coronations. Many pieces of English plate that were presented to visiting dignitaries can be seen in museums throughout Europe. Cromwell declined Parliament's invitations to be made king and became Lord Protector. It was marked by a ceremony in Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north bank ...

in 1657, where he donned purple robes, sat on the Coronation Chair, and was invested with many traditional symbols of sovereignty, except a crown. A crown—perhaps made of gilded base metal, which was typical of funerary crowns in those days—was placed beside Cromwell at his lying in state in 1660.

Restoration to present day

The monarchy was restored after Cromwell's death. For the English coronation of Charles II (), who had been living in exile abroad, new Jewels were made based on records of the lost items. They were supplied by the banker and royal goldsmith, Sir Robert Vyner, at a cost of £12,184 7s 2d – as much as three warships. It was decided to fashion the replicas like the medieval regalia and to use the original names. These 22-carat gold objects, made in 1660 and 1661, form the nucleus of today's Crown Jewels: St Edward's Crown, two sceptres, an orb, an ampulla, a pair of spurs, a pair ofarmill

An armill or armilla (from the Latin: ''armillae'' remains the plural of armilla) is a type of medieval bracelet, or armlet, normally in metal and worn in pairs, one for each arm. They were usually worn as part of royal regalia, for example at a ...

s or bracelets, and a staff. A medieval silver-gilt anointing spoon and three early Stuart swords had survived and were returned to the Crown, and the Dutch ambassador arranged the return of extant jewels pawned in Holland. The king also spent £11,800 acquiring of altar and banqueting plate, and he was presented with conciliatory gifts.

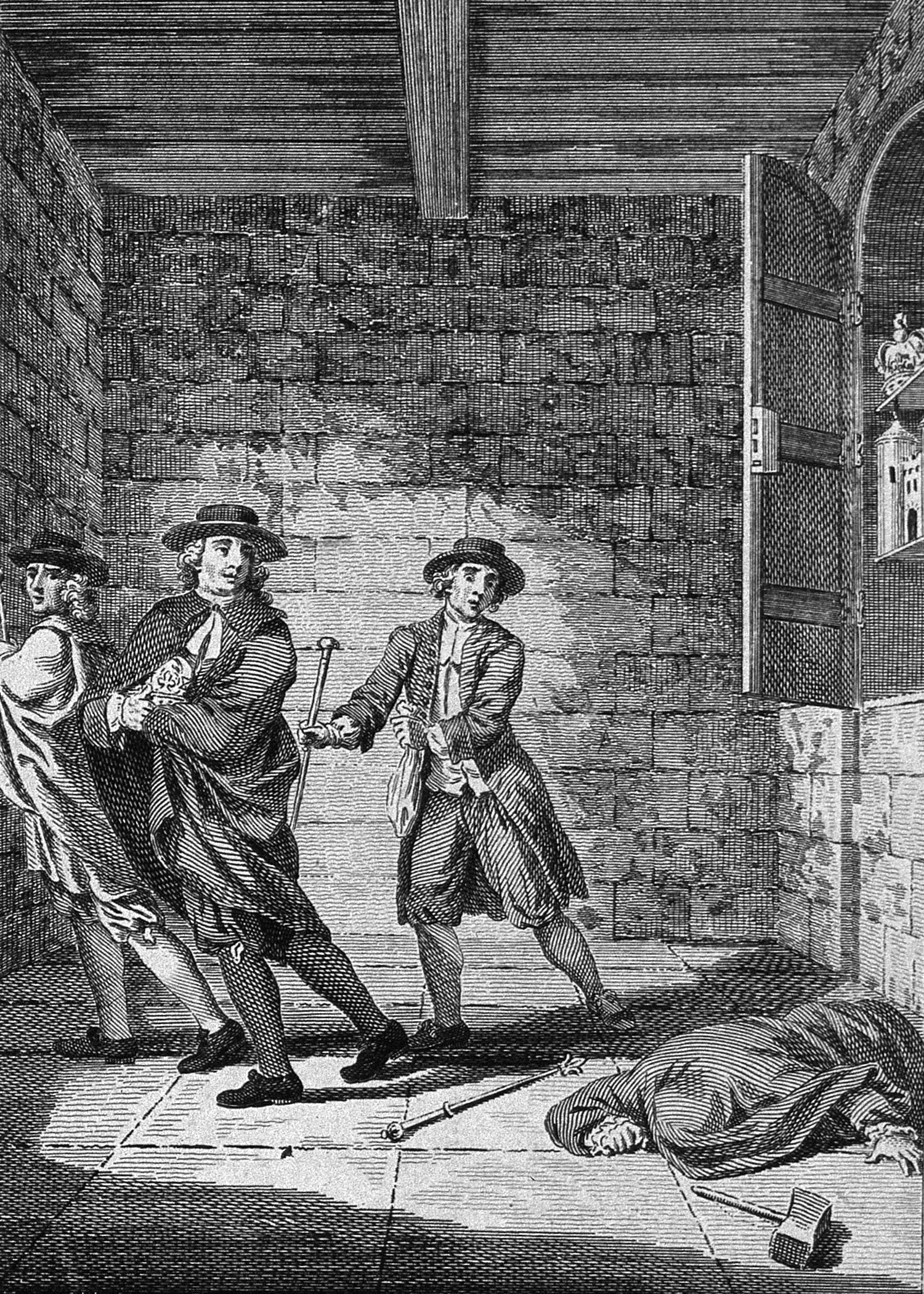

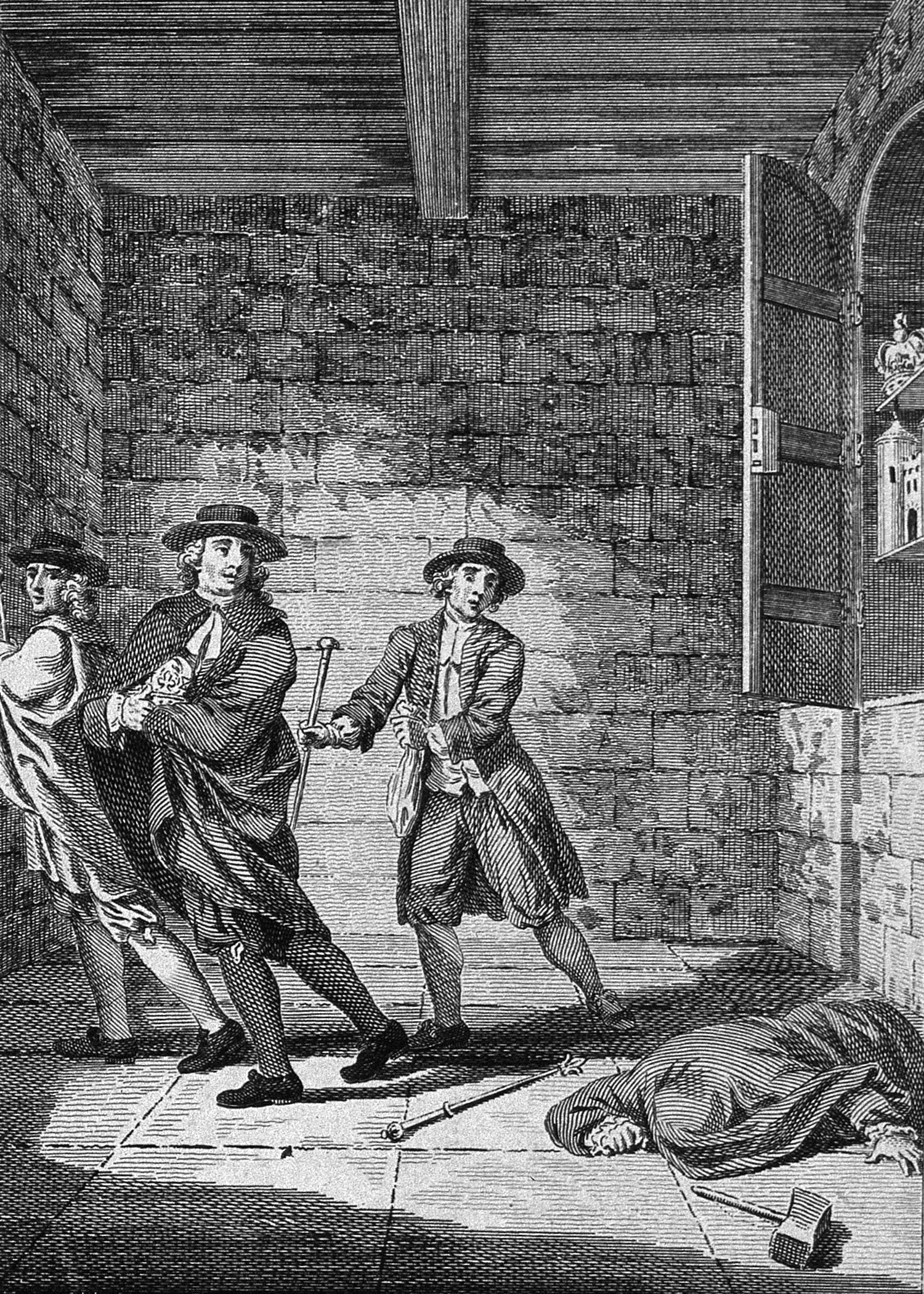

In 1669, the Jewels went on public display for the first time in the Jewel House at the Tower of London. The Deputy

In 1669, the Jewels went on public display for the first time in the Jewel House at the Tower of London. The Deputy Keeper of the Jewel House

The Master of the Jewel Office was a position in the Royal Households of England, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the United Kingdom. The office holder was responsible for running the Jewel House

The Jewel House is a vault housing the British ...

took the regalia out of a cupboard and showed it to visitors for a small fee. This informal arrangement was ended two years later when Thomas Blood

Colonel Thomas Blood (1618 – 24 August 1680) was an Anglo-Irish officer and self-styled colonel best known for his attempt to steal the Crown Jewels of England from the Tower of London in 1671. Described in an American source as a "no ...

, an Irish-born army officer loyal to Parliament, attacked the 77-year-old and stole a crown, a sceptre, and an orb. Blood and his three accomplices were apprehended at the castle perimeter, but the crown had been flattened with a mallet in an attempt to conceal it, and there was a dent in the orb. He was pardoned by the king, who also gave him land and a pension; it has been suggested that Blood was treated leniently because he was a government spy. Ever since, the Jewels have been protected by armed guards.

Since the Restoration, there have been many additions and alterations to the regalia. A new set was commissioned in 1685 for Mary of Modena, the first queen consort to be crowned since the Restoration (Charles II was unmarried when he took the throne). Another, more elaborate set had to be made for Mary II (), who was crowned as joint sovereign with her husband William III (). After England and Scotland were united as one kingdom by the Acts of Union 1707, the Scottish regalia

The Honours of Scotland (, gd, Seudan a' Chrùin Albannaich), informally known as the Scottish Crown Jewels, are the regalia that were worn by Scottish monarchs at their coronation. Kept in the Crown Room in Edinburgh Castle, they date from the ...

were locked away in a chest, and the English regalia continued to be used by British monarchs

There have been 13 British monarchs since the political union of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland on 1 May 1707. England and Scotland had been in personal union since 24 March 1603. On 1 January 1801, the Kingdom of Great Brit ...

. Gemstones were hired for coronations – the fee typically being 4% of their value – and replaced with glass and crystals for display in the Jewel House, a practice that continued until the early 20th century.

As enemy planes targeted London during the Second World War, the Crown Jewels were secretly moved to Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original c ...

. The most valuable gemstones were taken out of their settings by James Mann, Master of the Armouries

The Royal Armouries is the United Kingdom's national collection of arms and armour. Originally an important part of England's military organization, it became the United Kingdom's oldest museum, originally housed in the Tower of London from ...

, and Sir Owen Morshead

Sir Owen Frederick Morshead, (28 September 1893 – 1 June 1977) was a British Army officer and librarian, who served as Royal Librarian (United Kingdom), Royal Librarian from 1926 to 1958.

Early life

Morshead was born in Tavistock, Devon, the ...

, the Royal Librarian. They were wrapped in cotton wool, placed in a tall glass preserving-jar, which was then sealed in a biscuit tin, and hidden in the castle's basement.Shenton, pp. 203-204 Also placed in the jar was a note from the King, stating that he had personally directed that the gemstones be removed from their settings. As the Crown Jewels were bulky and thus difficult to transport without a vehicle, the idea was that if the Nazis invaded, the historic precious stones could easily be carried on someone's person without drawing suspicion and if necessary buried or sunk.

After the war, the Jewels were kept in a vault at the Bank of England for two years while the Jewel House was repaired; the Tower had been struck by a bomb. In 1953, St Edward's Crown was placed on the head of Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

() in what is now the only ceremony of its kind in Europe. Other European monarchies have abandoned coronations in favour of secular ceremonies. Today, 142 objects make up the Crown Jewels, which are permanently set with 23,578 precious and semi-precious stones and are seen by around 2.5 million visitors every year.

Crowns

Crowns are the main symbols of royal authority. All crowns in the Tower are decorated with alternating crosses pattée andfleurs-de-lis

The fleur-de-lis, also spelled fleur-de-lys (plural ''fleurs-de-lis'' or ''fleurs-de-lys''), is a lily (in French, and mean 'flower' and 'lily' respectively) that is used as a decorative design or symbol.

The fleur-de-lis has been used in the ...

, a pattern which first appears on the great seal of Richard III, and their arches are surmounted with a monde

A ''monde'', meaning 'world' in French, is an orb located near the top of a crown. It represents, as the name suggests, the world that the monarch rules. It is the point at which a crown's half arches meet. It is usually topped off either w ...

and cross pattée. Most of the crowns also have a red or purple velvet cap and an ermine border.

St Edward's Crown

The centrepiece of the coronation regalia is named afterEdward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æt ...

and is placed on the monarch's head at the moment of crowning.Mears, et al., p. 23. Made of gold and completed in 1661, St Edward's Crown

St Edward's Crown is the centrepiece of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom. Named after Saint Edward the Confessor, versions of it have traditionally been used to crown English and British monarchs at their coronations since the 13th cen ...

is embellished with 444 stones, including amethysts, garnet

Garnets () are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

All species of garnets possess similar physical properties and crystal forms, but differ in chemical composition. The different ...

s, peridots, rubies

A ruby is a pinkish red to blood-red colored gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum ( aluminium oxide). Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called sap ...

, sapphires

Sapphire is a precious gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum, consisting of aluminium oxide () with trace amounts of elements such as iron, titanium, chromium, vanadium, or magnesium. The name sapphire is derived via the Latin "sapphir ...

, topazes, tourmaline

Tourmaline ( ) is a crystalline silicate mineral group in which boron is compounded with elements such as aluminium, iron, magnesium, sodium, lithium, or potassium. Tourmaline is a gemstone and can be found in a wide variety of colors.

The te ...

s and zircon

Zircon () is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates and is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium(IV) silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is Zr SiO4. An empirical formula showing some of t ...

s. The coronation crown

A coronation crown is a crown used by a monarch when being crowned. In some monarchies, monarchs have or had a number of crowns for different occasions, such as a coronation crown for the moment of coronation and a ''state crown'' for general u ...

closely resembles the medieval one, with a heavy gold base and clusters of semi-precious stones, but the disproportionately large arches are a Baroque affectation. It was long assumed to be the original as their weight is almost identical and an invoice produced in 1661 was for the addition of gold to an existing crown. In 2008, new research found that it had actually been made in 1660 and was enhanced the following year when Parliament increased the budget for Charles II's twice-delayed coronation. The crown is tall and at a weight of has been noted to be extremely heavy. After 1689, monarchs chose to be crowned with a lighter, bespoke coronation crown (e.g., that of George IV) or their state crown, while St Edward's Crown rested on the high altar. At Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

's coronation in 1838 it was entirely absent from the ceremony. The tradition of using St Edward's Crown was revived in 1911 by George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

and has continued ever since. In 1953 Elizabeth II opted for a stylised image of this crown to be used on coats of arms, badges, logos and various other insignia in the Commonwealth realms to symbolise her royal authority, replacing the image of a Tudor-style crown adopted in 1901 by Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria and ...

.

Imperial State Crown

A much lighter crown is worn by the monarch when leaving Westminster Abbey, and at the annual State Opening of Parliament.Mears, et al., p. 29. The current

A much lighter crown is worn by the monarch when leaving Westminster Abbey, and at the annual State Opening of Parliament.Mears, et al., p. 29. The current Imperial State Crown

The Imperial State Crown is one of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom and symbolises the sovereignty of the monarch.

It has existed in various forms since the 15th century. The current version was made in 1937 and is worn by the monarc ...

was made in 1937 for George VI and is a copy of the one made in 1838 for Queen Victoria, which had fallen into a poor state of repair, and had been made using gems from its own predecessor, the State Crown of George I. In 1953, the crown was resized to fit Elizabeth II, and the arches were lowered by to give it a more feminine appearance. The gold, silver and platinum crown is decorated with 2,868 diamonds, 273 pearls, 17 sapphires, 11 emeralds and 5 rubies. Among the largest stones are the Cullinan II

The Cullinan Diamond is the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found,Scarratt and Shor, p. 120. weighing (1 lb 5.92 oz), discovered at the Premier No.2 mine in Cullinan, South Africa, on 26 January 1905. It was named after Thomas Cull ...

diamond, also known as the Second Star of Africa, added to the crown in 1909 (the larger Cullinan I is set in the Sovereign's Sceptre). The Black Prince's Ruby

The Black Prince's Ruby is a large, irregular cabochon red spinel weighing set in the cross pattée above the Cullinan II diamond at the front of the Imperial State Crown of the United Kingdom. The spinel is one of the oldest parts of the Crow ...

, set in the front cross, is not actually a ruby but a large cabochon red spinel. According to legend it was given to Edward the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock, known to history as the Black Prince (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), was the eldest son of King Edward III of England, and the heir apparent to the English throne. He died before his father and so his son, Richard II, suc ...

by the Spanish king Peter of Castile

Peter ( es, Pedro; 30 August 133423 March 1369), called the Cruel () or the Just (), was King of Castile and León from 1350 to 1369. Peter was the last ruler of the main branch of the House of Ivrea. He was excommunicated by Pope Urban V for ...

in 1367 and Henry V wore it at the Battle of Agincourt.Mears, et al., p. 30. How the stone found its way back into the Royal Collection after the Interregnum is unclear, but a substantial "ruby" was acquired for the Crown Jewels in 1661 at a cost of £400, and this may well have been the spinel. On the back of the crown is the cabochon Stuart Sapphire

The Stuart Sapphire is a blue sapphire that forms part of the British Crown Jewels. It weighs 104 carats (20.8 grams) and is believed to have originated from Asia, potentially present-day Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar or Kashmir.

Beginning

T ...

, and in the top cross is St Edward's Sapphire, reputedly taken from the ring of the Confessor when his body was re-interred at the Abbey in 1163. Below the monde hang four pearls, three of which are often said to have belonged to Elizabeth I, but the association is almost certainly erroneous.

Consort crowns

After the Restoration, wives of kings – queens consort – traditionally wore theState Crown of Mary of Modena

The State Crown of Mary of Modena is the consort crown made in 1685 for Mary of Modena, queen of England, Scotland and Ireland. It was used by future queens consort up until the end of the 18th century.

Originally set with hired diamonds, the ...

, wife of James II, who first wore it at their coronation in 1685. Originally set with 561 hired diamonds and 129 pearls, it is now set with crystals and cultured pearls for display in the Jewel House along with a matching diadem that consorts wore in procession to the Abbey. The diadem once held 177 diamonds, 1 ruby, 1 sapphire, and 1 emerald. By the 19th century, that crown was judged to be too theatrical and in a poor state of repair, so in 1831 the Crown of Queen Adelaide

The Crown of Queen Adelaide was the consort crown of the British queen Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. It was used at Coronation of William IV and Adelaide, Adelaide's coronation in 1831. It was emptied of its jewels soon afterwards, and has never be ...

was made for Queen Adelaide

, house = Saxe-Meiningen

, father = Georg I, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen

, mother = Princess Louise Eleonore of Hohenlohe-Langenburg

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Meiningen, Saxe-Meiningen, Holy ...

, wife of William IV, using gemstones from her private jewellery.

Thus began a tradition of each queen consort having a crown made specially for their use. In 1902 the

Thus began a tradition of each queen consort having a crown made specially for their use. In 1902 the Crown of Queen Alexandra

The Crown of Queen Alexandra was the consort crown of the British queen Alexandra of Denmark. It was manufactured for the 1902 coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra.

Background

Queen Victoria's death in January 1901 ended 64 years ...

, a European-style crown – flatter and with eight half-arches instead of the typical four – was made for Queen Alexandra

Alexandra of Denmark (Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julia; 1 December 1844 – 20 November 1925) was List of British royal consorts, Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 22 January 1901 t ...

, wife of Edward VII, to wear at their coronation. Set with over 3,000 diamonds, it was the first consort crown to include the Koh-i-Noor

The Koh-i-Noor ( ; from ), also spelled Kohinoor and Koh-i-Nur, is one of the largest cut diamonds in the world, weighing . It is part of the Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom. The diamond is currently set in the Crown of Queen Elizabeth The ...

diamond presented to Queen Victoria in 1850 following the British conquest of the Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising a ...

. Originally and set in an armlet, it was cut down to an oval brilliant weighing , which Victoria mounted in a brooch and circlet. The second was the Crown of Queen Mary

The Crown of Queen Mary is the consort crown made for Mary of Teck in 1911.

Mary bought the Art Deco-inspired crown from Garrard & Co. herself, and hoped that it would be worn by future queens consort. It is unusual for a British crown because ...

; also unusual for a British crown owing to its eight half-arches, it was made in 1911 for Queen Mary, wife of George V. Mary paid for the Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French ''Arts Décoratifs'', and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I), and flourished in the Unite ...

-inspired crown out of her own pocket and had originally hoped it would become the one traditionally used by future consorts. Altogether, it is adorned with 2,200 diamonds, and once contained the Cullinan III and Cullinan IV diamonds. Its arches were made detachable in 1914 allowing it to be worn as an open crown or circlet.Mears, et al., p. 27.

After George V's death, Mary continued wearing the crown (without its arches) as a queen mother

A queen mother is a former queen, often a queen dowager, who is the mother of the monarch, reigning monarch. The term has been used in English since the early 1560s. It arises in hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarchies in Europe and is also u ...

, so the Crown of Queen Elizabeth

The Crown of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, also known as The Queen Mother's Crown, is the crown made for Queen Elizabeth to wear at her coronation alongside her husband, King George VI, in 1937 and State Openings of Parliament during her ...

was created for Queen Elizabeth, wife of George VI, and later known as the Queen Mother, to wear at their coronation in 1937. It is the only British crown made entirely out of platinum, and was modelled on Queen Mary's Crown, but has four half-arches instead of eight.Keay (2011), p. 178. The crown is decorated with about 2,800 diamonds, most notably the Koh-i-Noor in the middle of the front cross. It also contains a replica of the Lahore Diamond given to Queen Victoria by the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

in 1851, and a diamond given to her by Abdülmecid I, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, in 1856. The crown was laid on top of the Queen Mother's coffin in 2002 during her lying in state and funeral. The crowns of Queen Alexandra and Queen Mary now feature crystal replicas of the Koh-i-Noor, which has been the subject of repeated controversy, with governments of both India and Pakistan claiming to be the diamond's rightful owners and demanding its return ever since gaining independence from the UK.

Prince of Wales coronets

A relatively modest gold

A relatively modest gold coronet

A coronet is a small crown consisting of ornaments fixed on a metal ring. A coronet differs from other kinds of crowns in that a coronet never has arches, and from a tiara in that a coronet completely encircles the head, while a tiara doe ...

was made in 1728 for Frederick, Prince of Wales

Frederick, Prince of Wales, (Frederick Louis, ; 31 January 170731 March 1751), was the eldest son and heir apparent of King George II of Great Britain. He grew estranged from his parents, King George and Queen Caroline. Frederick was the fa ...

, the eldest son of George II. It takes the form laid down in a royal warrant issued by Charles II in 1677, which states "the Son & Heir apparent of the Crown for the time being shall use & bear his coronett composed of crosses & flowers de Lizs with one Arch & in the midst a Ball & Cross". The single arch denotes inferiority to the monarch while showing that the prince outranks other royal children, whose coronets have no arches. Frederick never wore his coronet; instead, it was placed on a cushion in front of him when he first took his seat in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

. It was subsequently used by George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. Both kingdoms were in a personal union under him until the Acts of Union 1800 merged them ...

, George IV, and Edward VII when they were Princes of Wales. Due to its age, a new silver-gilt coronet was made for the future George V to wear at Edward VII's coronation in 1902. In contrast to the earlier coronet, which has a depressed arch, the arch on this one is raised. At George's coronation in 1911 the coronet was worn by his elder son Edward, who was invested as Prince of Wales at Caernarfon Castle a month later. The revival of this public ceremony, not performed since the early 17th century, was intended to boost the Royal family's profile in Wales. Princely regalia known as the Honours of Wales

The Honours of the Principality of Wales are the regalia used at the Investiture of the Prince of Wales, investiture of the Prince of Wales, as heir apparent to the British throne, made up of a coronet, a ring, a Staff of office, rod, a sword, a ...

were designed for the occasion by Goscombe John

Sir William Goscombe John (21 February 1860 – 15 December 1952) was a prolific Welsh sculptor known for his many public memorials. As a sculptor, John developed a distinctive style of his own while respecting classical traditions and forms of ...

, comprising a Welsh gold circlet with pearls, amethysts and engraved daffodils; a rod; a ring; a sword; and a robe with doublet and sash. After he became king in 1936, Edward VIII abdicated the same year and emigrated to France, where the 1902 coronet remained in his possession until his death in 1972. In its absence, a new coronet had to be created in 1969 for the investiture of the future Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to a ...

, which is made from gold and platinum and is set with diamonds and emeralds. Both it and the rod were added to the Jewel House in 2020, joining the 1728 and 1902 coronets.

Non-coronation crowns

In the Jewel House there are two crowns that were never intended to be worn at a coronation. Queen Victoria's Small Diamond Crown is just tall and was made in 1870 using 1,187 diamonds for Victoria to wear on top of her widow's cap. She often wore it at State Openings of Parliament in place of the much heavier Imperial State Crown. After the queen's death in 1901 the crown passed to her daughter-in-law Queen Alexandra and later Queen Mary. When George V attended the Delhi Durbar with Queen Mary in 1911 to be proclaimed (but not crowned) asEmperor of India

Emperor or Empress of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948, that was used to signify their rule over British India, as its imperial head of state. Royal Proclamation of 22 ...

, he wore the Imperial Crown of India

The Imperial Crown of India is the crown that was used by King in his capacity as Emperor of India at the Delhi Durbar of 1911.

Origin

Tradition prohibits the Crown Jewels from leaving the United Kingdom, a product of the days when kings and q ...

. As the British constitution

The constitution of the United Kingdom or British constitution comprises the written and unwritten arrangements that establish the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a political body. Unlike in most countries, no attempt ...

forbids coronation regalia to leave the United Kingdom, it was not possible for him to wear St Edward's Crown or the Imperial State Crown, so one had to be made specially for the event. It contains 6,170 diamonds, 9 emeralds, 4 rubies and 4 sapphires. The crown has not been used since and is now considered a part of the Crown Jewels.

Processional objects

A coronation begins with the procession into Westminster Abbey.Swords

The swords of state reflect a monarch's role as

The swords of state reflect a monarch's role as Head of the British Armed Forces